- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What Job Crafting Looks Like

- Jane E. Dutton

- Amy Wrzesniewski

Stories of three people who changed their jobs to find more meaning.

Twenty years ago, the authors started studying job crafting — the act of altering your job to make it more meaningful. Since then, they’ve identified different forms this concept can take. They include: task crafting , which involves changing the type, scope, sequence, and number of tasks that make up your job; relational crafting, where you alter who you interact with in your work; and cognitive crafting , where you modify the way you interpret the tasks and/or work you’re doing. The authors share stories of three individuals that illustrate what each of these types look like and how employees were able to make their jobs more meaningful and engaging.

Job crafting — changing your job to make it more engaging and meaningful — can take many forms. We’ve been studying job crafting for 20 years and our research among hospital cleaners , employees in a manufacturing firm, a women’s advocacy nonprofit , and tech workers identified three main forms these changes can take.

- JD Jane E. Dutton is the Robert L. Kahn Distinguished University Professor of Business Administration and Psychology at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business. She is co-founder of the Center for Positive Organizations at Ross.

- AW Amy Wrzesniewski ( [email protected] ) is a professor of organizational behavior at the Yale School of Management.

Partner Center

What is Job Crafting? (Incl. 5 Examples and Exercises)

If it’s one of the first two, you’re not alone. Stress and burnout are super popular topics in wellbeing literature, especially as the pace of competition creates new challenges for us at work.

Meetings, commutes, emails, and so forth arguably take their toll and can leave us wondering whether we’re paid enough to warrant it all. Living to work isn’t ideal, but working just to live is not an attractive concept, either.

So, the idea that we can find and create more meaning and happiness through our work is an appealing one. But how do we go about it? In this article, we’ll look at the how and the what of job crafting, which all stems inextricably from the ‘why’ of our working lives.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Work & Career Coaching Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify opportunities for professional growth and create a more meaningful career.

This Article Contains:

What is job crafting (incl. definition), a look at the job crafting model, 5 examples of job crafting, positive psychology and job crafting: meaningful work, 5 benefits of the approach, are there drawbacks, the job crafting questionnaire (pdf), the job crafting intervention, the job crafting exercise, the fatima job crafting case study, job crafting workshops, books on the topic.

- 5 Recommended Videos

A Take-Home Message

During the week, most of us spend half our waking hours at work. And a lot of us see it as a struggle, or at least a bore, looking forward to the weekend when we can do more worthwhile things. But what if your job itself was worthwhile? What if it was meaningful, left you satisfied, and through it, you could be part of something bigger?

The ‘Why’ of Job Crafting

Job crafting is about taking proactive steps and actions to redesign what we do at work, essentially changing tasks, relationships, and perceptions of our jobs (Berg et al., 2007). The main premise is that we can stay in the same role, getting more meaning out of our jobs simply by changing what we do and the ‘whole point’ behind it.

So through the techniques and approaches that we’ll look at in this article, we ‘craft’ ourselves a job that we love. One where we still can satisfy and excel in our functions, but which is simultaneously more aligned with our strengths, motives, and passions (Wrzesniewski et al., 2010). Unsurprisingly, it has been linked to better performance (Caldwell & O’Reilly, 1990), intrinsic motivation, and employee engagement (Halbesleben, 2010; Dubbelt et al., 2019).

Job Crafting Definitions

In one sense, then, job crafting is:

“an employee-initiated approach which enables employees to shape their own work environment such that it fits their individual needs by adjusting the prevailing job demands and resources”

(Tims & Bakker, 2010)

However, really great organizational development always starts with the ‘Why’, so here is another definition:

[Job crafting] is proactive behavior that employees use when they feel that changes in their job are necessary.

(Petrou et al., 2012)

3 Key Types of Job Crafting

So how do we go about it? In three possible ways, says Professor Amy Wrzesniewski, who first introduced the concept with Jane Dutton in 2001. These are task crafting, relationship crafting, and/or cognitive crafting, and they describe the ‘behaviors’ that employees can use to become ‘crafters’. Through one or more of these activities, we can aim to create the job-person fit that might be lacking in our current roles (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Task Crafting: Changing up responsibilities

Task crafting may be the most discussed aspect of the approach, perhaps because job crafting is commonly seen as active ‘shaping’ or ‘molding’ of one’s role. It can involve adding or dropping the responsibilities set out in your official job description (Berg et al., 2013).

For instance, a chef may take it upon themselves to not just serve food but to create beautifully designed plates that enhance a customer’s dining experience. As another example, a bus driver might decide to give helpful sightseeing advice to tourists along his route.

This type of crafting might also (or alternatively) involve changing the nature of certain responsibilities, or dedicating different amounts of time to what you currently do. As we’ll see in some of the examples below, this doesn’t necessarily affect the quality or impact of what you’re hired to do.

Relationship Crafting: Changing up interactions

This is how people reshape the type and nature of the interactions they have with others. In other words, relationship crafting can involve changing up who we work with on different tasks, who we communicate and engage with on a regular basis (Berg et al., 2013). A marketing manager might brainstorm with the firm’s app designer to talk and learn about the user interface, unlocking creativity benefits while crafting relationships.

Cognitive Crafting: Changing up your mindset

The third type of crafting, cognitive crafting, is how people change their mindsets about the tasks they do (Tims & Bakker, 2010). By changing perspectives on what we’re doing, we can find or create more meaning about what might otherwise be seen as ‘busy work’. Changing hotel bedsheets in this sense might be less about cleaning and more about making travelers’ journeys more comfortable and memorable.

Through one, two, or all of the above, job crafting proponents argue that we can redefine, reimagine, and get more meaning out of what we spend so much time doing.

Job Design vs Job Crafting

If you’re interested in organizational psychology, you might be wondering what the differences are between the job design and job crafting. There are indeed similarities between the former and ‘task crafting’, as job design involves systematic organization of work-related processes, functions, and tasks (Garg & Rastogi, 2006).

Both task crafting and job design can involve task revision, where responsibilities are added or dropped to change the nature of your role. Both also stem from the premise that job dimensions can impact our experienced meaningfulness, growth, intrinsic motivation, and job satisfaction (Hackman & Oldham, 1976; 1980).

Even job sharing under the job characteristics model can be seen as a type of relationship crafting in some respects, but in most cases, job design is seen as a ‘top-down’ organizational approach in which the worker is mostly passive (Makul et al., 2013; Miller, 2015).

In contrast, job crafting puts the responsibility for change in employees’ hands. Workers are proactive and the approach is first and foremost about enhancing their wellbeing (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001; Tims et al., 2013). Arguably, this gives rise to potential drawbacks for the organization—even for the employee in question—and we’ll cover these limitations in this article, too.

To be fair, there is more than one job crafting model. In fact, there are at least two important frameworks that are being developed and further developed as we learn more about the discipline as a whole. These are the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model, and the Job Crafting Model.

First, we know that a proactive approach is an important precursor for job crafting. But what else do we need to boost our chances of success? From a theoretical perspective, we need to know a bit about job demands and resources, and the Job Demands-Resources Model is very useful.

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model

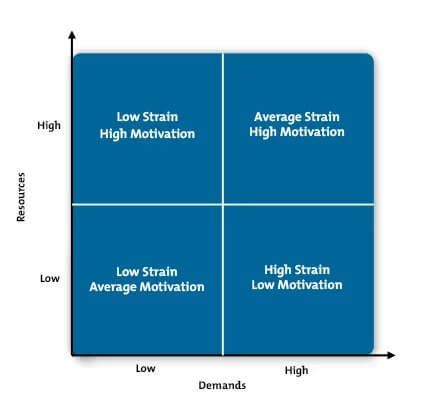

Bakker and Demerouti’s (2007) JD-R Model is about job characteristics. In short, it views all the characteristics of our jobs—psychological, physical, organizational, and social aspects—as either demands or resources.

- Job demands require that we put in physical or psychological effort or skills; they ‘cost’ us something. Emotional strain and similar are popular examples of job demands, which can lead to costs like stress, burnout, and related stressors when they become extreme (Bakker et al., 2003; Bakker & Demerouti, 2008).

- Job resources help us accomplish our work goals and we can draw on these facilitators to counter the potentially negative impacts of job demands. They can be made available by organizations or they can be personal, respectively these are workplace resources or personal resources. The first would entail aspects like career prospects, training, and autonomy, and examples of the second include optimism and self-efficacy (Bakker & Demerouti, 2008).

When we think about job crafting from a positive psychology perspective, we’re looking at how we can foster or facilitate positive emotions . According to the JD-R model, we can do this in at least two ways:

- First, by upping our job resources – We might use relationship crafting, for instance, to increase our social resources. Another example is to add to our structural resources (training, autonomy, etc) through task crafting.

- Second, by increasing our job demands – to a pleasantly challenging extent. Think eustress or ‘stretch zone’ challenges rather than vanilla stress.

The ultimate goal of the JD-R model is to allow for an understanding of how demands and resources interact to impact our motivation, as shown below.

Source: Mindtools.com

The Job Crafting Model

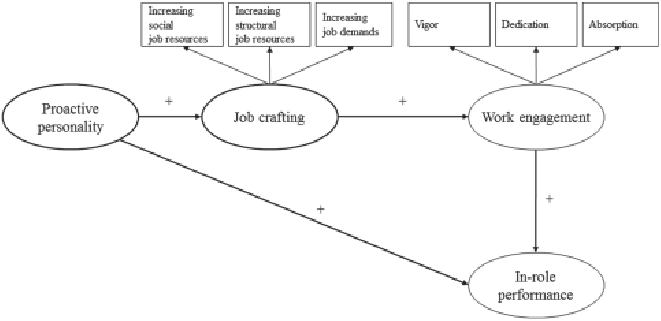

It’s when we consider job crafting that proactivity comes into the equation, and in Bakker et al.’s (2012) study, we first see The Job Crafting Model as a framework. In their research, they found that proactive personalities were positively related to job performance, through work engagement and job crafting. The exact relationships they found are shown in the Job Crafting Model below (Bakker et al., 2012).

Source: Bakker et al. (2012)

Their study also found that:

- Employees with proactive personalities were more likely to be involved in job crafting;

- This promoted greater engagement at work, by facilitating alignment between job resources, job demands, personal needs, and their own capabilities; and

- Employees who increased their structural resources, social resources and specific aspects of their job demands received higher performance ratings, according to their co-workers.

There is one key limitation of this study for those interested in cognitive crafting; this particular aspect of the three key types wasn’t examined (Berg et al., 2013).

2 Job Crafting Coaching Manuals [PDF]

Help others redesign their work. This manual and the accompanying client workbook outline a seven-session coaching trajectory for you, the practitioner, to expertly guide others through their own unique job crafting journey.

It’s in Berg and colleagues’ (2010) article that we’re given some super insight into job crafting—in action.

This paper is worth a read if you’re keen to get more of a feel for the approach.

1. Task Crafting

“ I really enjoy online tools and Internet things…So I’ve really tailored that aspect of the written job description, and really ‘‘upped’’ it, because I enjoy it…it gives me an opportunity to play around…explore tools and web applications, and I get to learn, which is one of my favorite things… ” (Berg et al., 2010: 166)

Just to recap, task crafting can be adding resources through extra tasks, while some might [also] choose to change what they’re currently doing. One interviewee, an associate who worked for a non-profit, stepped up the amount of time she spent working with online applications. In this way, she was engaging her passion for learning, allocating the proportion of time she spends on a specific aspect, and making it all the more meaningful.

2. Relationship Crafting

“ I have taken the initiative to form relationships with some of the folks who fulfill orders…That’s not my area, but I was really interested in how that worked and wanted to learn…I have learned a lot from them, and that’s helped me in my job. ” (Berg et al., 2010: 166)

Above, a customer service rep describes creating additional relationships with co-workers. While building up the way he interacts with others, he’s expanding his social job resources and gaining knowledge. As he later describes, this helps him explain the fulfillment process to customers directly.

3. Cognitive Crafting

“ Technically, [my job is] putting in orders, entering orders, but really I see it as providing our customers with an enjoyable experience, a positive experience, which is a lot more meaningful to me than entering numbers. ” (Berg et al., 2010: 167)

Here, a different customer service representative recounts going above and beyond to enhance the client experience. This perspective shift sees the employee reframing their job as part of ‘something bigger’, both within the organizational context and for society in general. We can see a holistic perspective that has been shaped; this individual is no longer viewing their job as separate, unconnected tasks, but as a ‘meaningful whole’ (Berg et al., 2010).

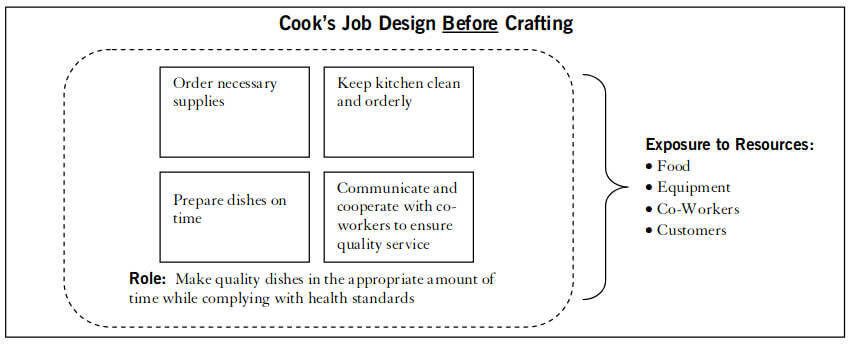

4. From Cook to Creative Artist

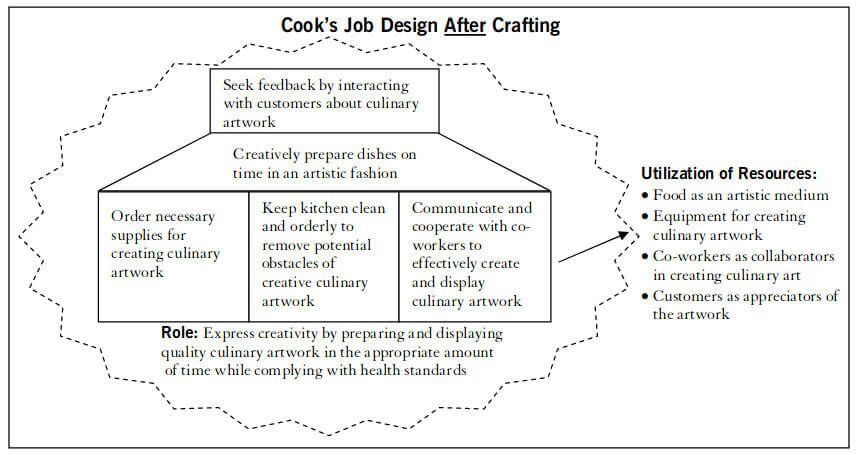

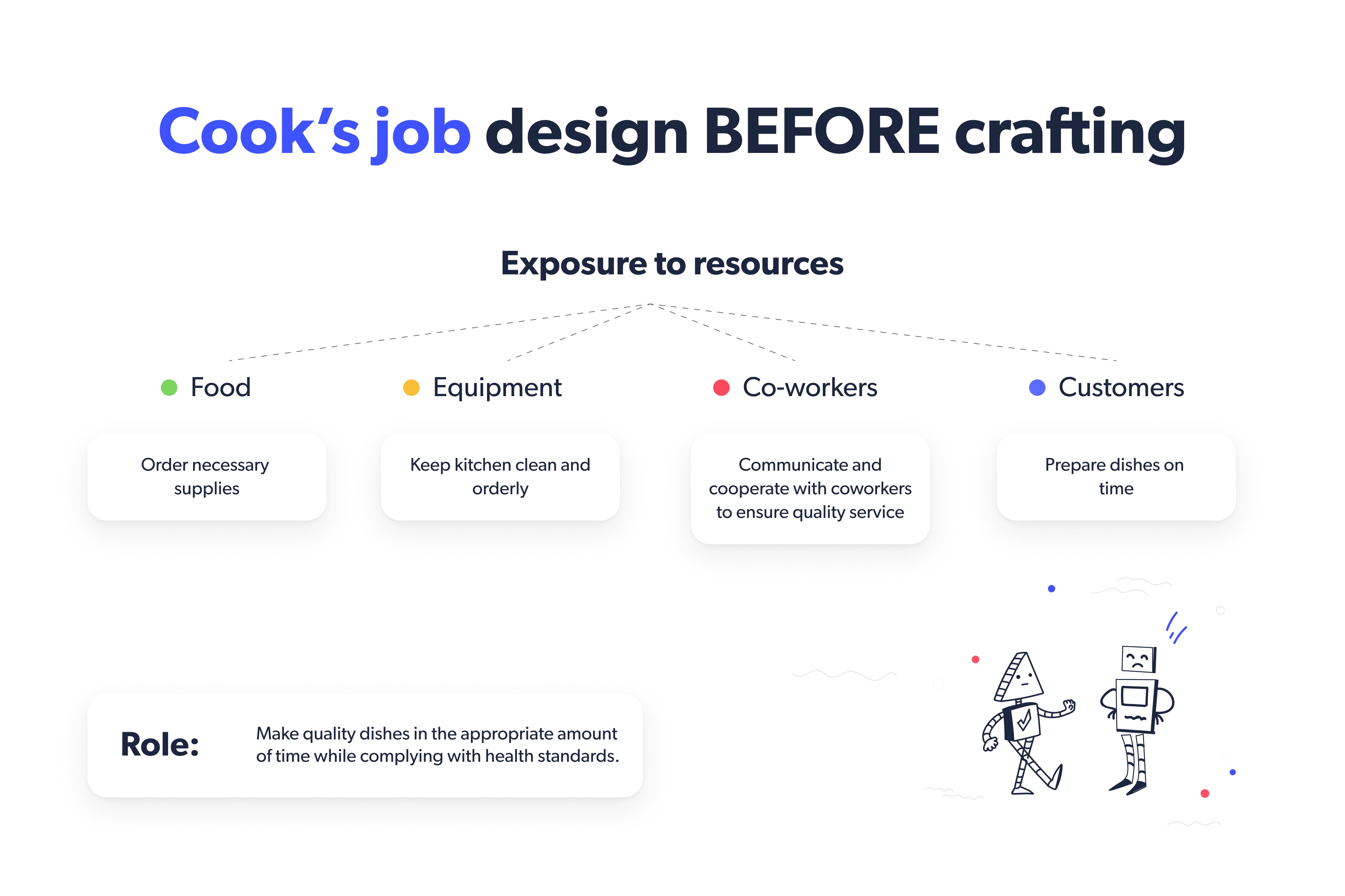

Putting it all together, here’s one nice example of job crafting given by Berg and colleagues (2007). Before crafting, this cook’s job consists of—or at least, is perceived by the cook as—separate tasks, very much segmented as they would be in a formal job description. Job resources here are not inherently meaningful other than as facilitators for accomplishing the tasks, and one could argue that the role in question is almost defined by its boundaries.

Source: Berg et al. (2007: 6)

After job crafting, we can see evidence of all three approaches at work:

- The chef’s perspectives are altered fundamentally—food has become culinary artwork, bringing her a whole new sense of purpose. In other words, it’s not hard to guess where this chef’s passions lie; she has cognitively crafted himself a new role as a culinary artisan.

- In this newly reframed context, tasks are meaningfully linked—both to one another and to the larger context. We see job resources taking on new meaning: food is not just that, but a means of personal creative expression. New tasks are added, expanding the boundaries of her role.

- Customers also take on new meaning as feedback providers, so the chef can potentially grow and improve her skills. At the same time, relationship crafting sees her interactions with co-workers becoming more collaborative. Perhaps through this, there’s knowledge transfer as well as increased use of her social resources.

5. The Pink Glove Dance

Last but not least, here’s another lovely example of job crafting in (musical) action—The Pink Glove Dance is essentially personal meaning being created by hospital employees. In this video, you’ll see cleaners, janitors, clerks, and other hospital staff linking ‘what they do’ on the job with who they are and their commitment to raising awareness of breast cancer (Harquail, 2009). What do you think?

Throughout this whole article, we’ve been looking at job crafting as a way to create meaning in our roles. Succinctly, ‘meaningfulness’ describes how much significance we attribute to our work (Rosso et al., 2010). It’s one of five key concepts in Seligman’s PERMA model , and he defines it as,

“using your signature strengths and virtues in the service of something much larger than you are”

(Seligman, 2004: 294)

By creating or finding more meaning in our work, positive psychology would say that we’re increasing our happiness. And in the empirical literature, there is ample evidence that meaningfulness does play out well in the workplace—as enhanced job satisfaction, performance, and motivation (Hackman & Oldman, 1980; Rosso et al., 2010).

Job crafting presents lots of potential benefits for organizational and positive psychology practitioners. While still relatively young, the approach has been examined empirically. Among the findings, and in addition to more meaningful work as mentioned above, there is evidence for at least five main benefits.

- Enhanced organizational performance – The very act of shaping one’s own job is beneficial, according to Frese and Fay (2001). Proactive crafting is inherently innovative and creative, and at an organizational level, it’s conducive to flexibility and adaptability. In increasingly dynamic and global business environments, it can contribute to a firm-level competitive advantage.

- Greater engagement – Altering the way we see and engage with our jobs can give us a sense of control over what the tasks do, as well as more fulfillment from the connections we make (Lyon, 2008; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Basically, we have more resources at our disposal, which is intrinsically motivating—it facilitates personal growth and helps us accomplish our goals (Halbesleben, 2010 ).

- Adding more challenge promotes mastery – When we stretched ourselves a healthy amount through task crafting, we encourage mastery experiences; these, in turn, are conducive to our wellbeing (Gorgievski & Hobfoll, 2008). In job crafting, too, we may seek out feedback and support, potentially boosting our individual job performance (Goodman & Svyantek, 1999)

- It may help us achieve our ‘ideal’ career status – By analyzing our tasks and identifying our goals , we can move toward them in a more effective way through crafting (Strauss et al., 2012). When we add or alter tasks in alignment with our strengths and motives, we experience better person-job fit (Oldham & Hackman, 2010)

- Evidence suggests that it makes us happier – In a study by Slemp and Vella-Broderick (2013), the degree of job crafting that employees got involved with was linked to how well their psychological and subjective wellbeing needs were satisfied.

There are, of course, some limitations to job crafting. Organizations are systems, so changing how we view and do things can impact both the firm and the individual—let’s look at some potential downsides.

Drawbacks For Organizations

Misaligned goals.

Essentially, job crafting aims to benefit the employee—it’s neither advantageous nor a pitfall for the company when an employees’ goals are consistent with those of their organization (Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001). That alignment is critical in understanding how it plays out in practice, meaning when individual goals and organizational goals are misaligned, we can see negative impacts of job crafting.

In other words, if someone is employed to carry out a certain task, job crafting shouldn’t be a means of changing up the job beyond recognition. It is clearly a pitfall for the organization if a chef creates beautiful cuisine that’s essentially inedible or unsafe. So as Wrzesniewski and Dutton premise, more meaning in one’s role shouldn’t jeopardize organizational effectiveness (2001).

Unequal Access

Another potential disadvantage is more about how we view our jobs in the first instance. In order to job craft, we first need to see our jobs as alterable (Berg, 2013). That is, we may feel certain factors are limiting how free we are to add tasks or alter relationships, for instance, and these can vary based on our roles.

Studies show that senior employees felt they were limited time-wise when it came to crafting, and lower-level employees cited not enough autonomy as an equivalent challenge (Berg et al., 2010). Some workers whose tasks were closely interdependent also felt a similar way, after all, how could they change their roles without disrupting others’ work?

In one respect, this can be seen as a ‘perspective’ or ‘adaptability’ problem, or even suggest more support for the ‘proactive personality’ argument. However, it also raises another issue. That is, some jobs may simply be more ‘craftable’ than others, making some more able to enjoy its benefits. Others, if special steps aren’t taken, may see this as inequity (Schoberova, 2015).

Drawbacks For Individuals

Taking on too much.

For individuals, it may be tempting to take task crafting a little far. Understandably, if we add on tasks that are overly demanding, or give ourselves excessive tasks while crafting our roles, we risk taking on too much.

If employees aren’t sufficiently informed about the risks of doing so, job crafting can bring with it all the increased dangers of overwork—stress, exhaustion, burnout, and unhappiness (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). In light of this, some authors argue that managers should get more involved in their employees’ job crafting initiatives (Schoberova, 2015).

Exploitation

A final argument against the approach suggests that job crafting leaves some workers open to exploitation. This potentially can occur in the sense that employees might be going ‘above and beyond’ the call of duty without being fairly reimbursed by the organization.

A study of zoo workers by Bunderson and Thompson (2009), for instance, showed some crafters were paid less than their co-workers. This was despite their investing extra time and effort into their newly crafted jobs, in pursuit of deeper meaning at work.

So, can we measure the extent to which we’re actively job crafting? The Job Crafting Questionnaire ( JCQ ) has been developed to assess how much we engage in the three different behaviors at work. Designed by positive psychology researchers Stemp and Vella-Brodrick (2013), it is a self-report instrument using a 6-item Likert scale. Based on Wrzesniewski and Dutton’s (2001) 3 areas, the JCQ takes only a short while to complete, with only 15 questions.

With 1 being Hardly Ever , and 6 being Very Often (as often as possible within the organizational context), employees indicate the degree to which they engage in tasks, relationships, and cognitive crafting. Here are some sample items.

Task Crafting Items

Please indicate the extent to which you…

- Give preference to work tasks that suit your skills or interest?

- Introduce new work tasks that you think better suit your skills or interests?

- Change the scope or types of tasks that you complete at work?

Relationship Crafting Items

- Organize special events in the workplace (e.g., celebrating a co-worker’s birthday)?

- Make friends with people at work who have similar skills or interests?

- Choose to mentor new employees (officially or unofficially)?

Cognitive Crafting Items

- Remind yourself about the significance your work has for the success of the organization?

- Think about the ways in which your work positively impacts your life?

- Remind yourself of the importance of your work for the broader community?

In developing the JCQ, the authors adapted some items from a measure of job crafting that was designed by Leana et al. (2008) for educators.

Job crafting – the power of personalising our work – Rob Baker

How do we start then, at an organizational level? The good news is that several studies have looked at job crafting interventions, and one, in particular, is described by Van Den Heuvel et al. in their 2015 study. Based on the JD-R Model, the authors developed a one-day training intervention for a Dutch police district to see if job crafting impacted their self-efficacy, wellbeing and positive affect.

The aims were to teach police participants to see their occupational environment and job characteristics under the framework, that is, as resources and demands that they could shape through job crafting (Van Den Heuvel et al., 2015). During the initial day-long session, they also learned to create, establish, and map their own crafting goals on a poster.

In the afternoon they reflected on them, and over the following four weeks, Van Den Heuvel and colleagues followed their progress. They had four key hypotheses, the third of which looked specifically at whether job crafters would experience greater positive affect and lower negative affect than ‘non-crafters’.

Outcomes of the Intervention

This intervention had mixed results. On one hand, there was some support for its efficacy:

- On average, police ‘crafters’ reported having more development opportunities than they did prior;

- Job crafting participants were also found to have higher self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997);

- They reported lower negative affect and an upward in positive affect; and

- Police ‘crafters’ were more inspired to look into and act on their learning opportunities.

On the flip side, the intervention showed no significant effect for reported job crafting behaviors, and the aforementioned ‘upward trend’ in positive affect was statistically insignificant.

Having a good sense of what job crafting involves is an excellent start if you want to give it a try. At the same time, it helps to have an idea of where you might start—what opportunities you might pursue. That’s what The Job Crafting Exercise aims to help you achieve, by encouraging you to view your job as malleable, craftable, and in your control.

In essence, The Job Crafting Exercise helps you perceive seemingly unconnected and segmented tasks as ‘building blocks’ for you to shape in a way that means something.

Developed by Berg, Dutton, and Wrzesniewski (2013), it’s broken into several parts. Throughout all of these, it helps to keep the JD-R Model in mind. Can you identify which aspects are demands, and which are resources? What could you benefit from more of, in terms of reducing your psychological costs—stress, energy, etc.? Where might you welcome a stretch or a challenge?

- First, you’ll create what’s known as a Before Sketch. This helps you understand how you’re allocating and spending your time across various tasks. Think here in terms of energy, and broadly about resources and demands.

- The next step is grouping your whole job into three types of Task Blocks. The biggest of these blocks are for tasks which consume the most of your effort, attention, and time; the smallest blocks are for the least energy-, attention-, and time-intensive tasks, and some will fall into the middle, ‘medium-sized’ blocks.

- With this knowledge of how your personal resources get allocated, you now craft an After Diagram of what your ideal role will look like. Of course, you aren’t stepping completely outside of what you’re formally required to do, but do use your strengths, passions, and motives to create something more meaningful. And in doing so, we use the same idea of task blocks—of course, this time with different priorities.

- Now you have an After Diagram, and you can ‘frame’ different task groups—Role Frames, which you see as serving different functions. Here, you’re crafting your perceptions so you can label different tasks in reimagined ways: rather like our chef-turned-food artisan above.

- The last step is where you create an Action Plan to set out clear goals for the short- and long-term. How are you going to move from your Before Diagram (current job) to your After Diagram (ideal job)?

If you’re looking to access The Job Crafting Exercise, you can purchase the resources at the University of Michigan School of Business (Berg et al., 2013).

Originally published in the Harvard Business Review, the ‘Fatima’ case study looks in depth at the three different types of job crafting: task, relationship, and cognitive crafting (Wrzesniewski et al., 2010). Here’s a quick overview—at some points, you’ll easily be able to draw parallels with the Job Crafting Exercise described above.

About Fatima

A mid-level marketing manager, Fatima is a high-performing employee who has great relationships with her colleagues and others. While she meets and exceeds the KPIs for her role—monitoring team performance, responding to their inquiries, and so forth, she feels like she’s stuck.

Put simply, Fatima spends a lot more time doing the unengaging, less stimulating parts of her job than the things she’d rather be doing. She’s wondering why she applied for the job in the first place and whether she should get out.

Why Job Crafting?

This ‘stuck’ feeling isn’t only about how Fatima is spending her time. In fact, it’s just as much about how she’s not spending her time. She’s a talented social media user, passionate about learning and wants to integrate that growing expertise into her work for the team. And all the while, Fatima’s driven to improve.

While the case study doesn’t delve much further into her personal feelings, it’s pretty clear that she’s feeling unmotivated. Maybe even like she’s in the wrong job and unsatisfied because of it.

Task Analysis and Job Crafting

The great thing about Wrzesniewski and colleagues’ (2010) Fatima Case Study is that it offers visuals that clearly link task analysis with job crafting. Below, a diagram—similar to the cook/food artisan figure we saw earlier—shows how Fatima’s new tasks look before and after she’s reshaped and reimagined it.

Fatima’s role before crafting:

Here, we see task analysis coming into play; Fatima’s systematic approach to visualizing what she does and how much time she devotes to different aspects of her marketing role. A considerable bulk of her time is spent problem-solving with her team and responding to their questions, as one example. Tasks that she’s passionate about—like strategizing—fall toward the bottom, where she spends the least of her time.

Source: Wrzesniewski et al. (2010)

Fatima’s role after crafting:

Now, Fatima’s started from a different place: from her passions, motives, and strengths. As you’ll recall, she’s a social media enthusiast and wants to craft relevant tasks into her role. In fact, while she’s still performing the same job, she’s expanded it to encompass two roles.

Empowering her team covers a lot of the same duties, but from a new perspective that frames her input as valuable in terms of the organization’s goals. Simultaneously, outside the grey box, she’s added Building and using social media tasks that mean something to both her and the firm.

If you’re after more information, as well as another related example, you can find the whole job crafting case study here .

The Job Crafting Exercise can be done in workshops as groups. Typically they don’t need to last longer than a couple of hours as you work through the stages described above. It’s an interesting and often very useful way to get managers involved, as suggested earlier.

This detailed example will show you what a Job Crafting Workshop looks like in practice (Berg et al., 2013).

You can get the whole Job Crafting Exercise book from the Center for Positive Organizations, but you will find that most information you need is readily available online.

Jump ahead to the reference section of this article if you’re after the most important research papers to date.

3 Recommended Videos

These three videos are quick takes on job crafting, with Prof Amy Wrzesniewski in the lead with the amazing work she has been doing.

1. Job Crafting – Amy Wrzesniewski on creating meaning in your own work

Professor Amy Wrzesniewski gives a little overview of her original hospital cleaning crew study, and how this gave rise to the idea of job crafting.

2. Redesigning Wellness Podcast 089: Job Crafting and Finding the Meaning of Work with Amy Wrzesniewski

Here’s another interview with Professor Wrzesniewski and Jen Arnold. Among other things, they discuss its role in performance, its limits, and how job crafting can redefine wellness in organizations.

3. Job Crafting: A Fresh Take on Your Old Job

Here’s a little overview of job crafting that appeared on TV. In this summary, there is a little discussion on how you can get started, and the potential downsides of crafting your job. Also, some useful tips for bringing up the topic with your boss.

The idea that your calling isn’t always “somewhere out there” doesn’t have to be terrifying. Especially if that’s because you’ve already got knowledge and tools to craft your own meaning. After all, as it’s been argued before, all employees are potential job crafters, and that alone is an empowering piece of knowledge.

Have you used job crafting to turn around a dull job? Or have you implemented a job crafting intervention before?

Why not share your thoughts on job crafting with us, I’d love to hear them!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Work & Career Coaching Exercises for free .

- Bakker, A.B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22 , 309–328.

- Bakker, A.B., Demerouti, E., Taris, T., Schaufeli, W.B. & Schreurs, P. (2003). A multi-group analysis of the Job Demands-Resources model in four home care organizations. International Journal of Stress Management, 10 , 16–38.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . Macmillan.

- Berg, J.M., Dutton, J.E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2007). What is Job Crafting and Why Does It Matter?. Retrieved from https://positiveorgs.bus.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/What-is-Job-Crafting-and-Why-Does-it-Matter1.pdf

- Berg, J. M., Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2010). Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31 (2-3), 158‐186.

- Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. Purpose and meaning in the workplace, 81 , 104.

- Bunderson, J. S., & Thompson, J. A. (2009). The call of the wild: Zookeepers, callings, and the double-edged sword of deeply meaningful work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54 (1), 32‐57.

- Caldwell, D. F., & O’Reilly, C. A., III. (1990). Measuring person-job fit with a profile-comparison process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75 , 648–657.

- Demerouti, Peeters, Schaufeli, & Hetland, 2012 Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., Peeters, M. C. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hetland, J. (2012). Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33 , 1120–1141.

- Dubbelt, L., Demerouti, E., & Rispens, S. (2019). The value of job crafting for work engagement, task performance, and career satisfaction: longitudinal and quasi-experimental evidence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28 (3), 300-314.

- Frese, M., & Fay, D. (2001). Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. In B. M. Staw & R. I. Sutton (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (Vol. 23, pp. 133-187). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science

- Garg, P., & Rastogi, R. (2006). New model of job design: motivating employees’ performance. Journal of Management Development, 25 (6), 572-587.

- Goodman, S. A., & Svyantek, D. J. (1999). Person-organization fit and contextual performance: Do shared values matter? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55 , 254–275.

- Gorgievski, M. J., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2008). Work can burn us out or fire us up: Conservation of resources in burnout and engagement. In J. R. B. Halbesleben (Ed.), Handbook of stress and burnout in health care (pp. 7–22). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

- Hackman, J. R.& Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16 , 250-279.

- Hackman, J. R.& Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 102–117). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Harquail, C.V. (2009). A Job Crafting Example: The Pink Glove Dance, Retrieved from http://authenticorganizations.com/harquail/2009/12/08/a-job-crafting-example-the-pink-glove-dance/

- Leana, C., Appelbaum, E., & Shevchuk, I. (2009). Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Academy of Management Journal, 52 (6), 1169-1192.

- Makul, A. Z. A., Rayhan, S. J., Hoque, F., & Islam, F. (2013). Job characteristics model of Hackman and Oldhamin garment sector in Bangladesh: A case study at Savar 109 area in Dhaka district. International Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences, 1 (4), 188-195.

- Mindtools.com. Job Demands-Resources Model. Retrieved from https://www.mindtools.com/media/Diagrams/jdr-model-new.jpg

- Oldham, G. R., & Hackman, J. R. (2010). Not what it was and not what it will be: The future of job design research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31 , 463–479.

- Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in organizational behavior, 30 , 91-127.

- Schoberova, M. (2015). Job crafting and personal development in the workplace: Employees and managers co-creating meaningful and productive work in personal development discussions. MAPP Capstone Project, University of Pennsylvania.

- Seligman, M. E. (2004). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment . Simon and Schuster.

- Slemp, G. R., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2013). The Job Crafting Questionnaire: A new scale to measure the extent to which employees engage in job crafting. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3 (2), 126-146.

- Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A., & Parker, S. K. (2012). Future work selves: How salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97 , 580–598.

- Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. South-African Journal of Industrial Psychology , 36 , 1–9.

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of occupational health psychology, 18 (2), 230.

- Van den Heuvel, M., Demerouti, E., & Peeters, M. C. (2015). The job crafting intervention: Effects on job resources, self-efficacy, and affective wellbeing. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88 (3), 511-532.

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of management review, 26 (2), 179-201.

- Wrzesniewski, A., Berg, J. M., & Dutton, J. E. (2010). Managing yourself: Turn the job you have into the job you want. Harvard Business Review, 88 (6), 114-117.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

This is great! If implemented correctly should improve the employees experience and also the engagement. This approach values the person and makes the job meaningful.

Fantastic article! Job crafting is an essential aspect of career development, and your insightful post provides a clear understanding of its significance. The five examples and exercises you’ve shared offer practical ways for individuals to shape their roles and find fulfillment in their careers. For those seeking ‘IT Jobs for Freshers,’ this knowledge can be invaluable in creating a more rewarding and tailored work experience. Thanks for shedding light on this empowering concept

I found this article fascinating, informative and logical as it separated technical, emotional and intellectual issues on job redesign and recrafting. Also it gave agency to the individual incumbent if the job instead of doing something to them! I worked as an Organisation Consultant in the 90 s and then VP of HR & OD and wish I had broken down the concepts and brought it in organisationally. I had already studied and written college papers on job redesign in the 1980s and in the 90 s and this century studied psychotherapy which melds with the thoughts and concepts in this article. Well done all

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Company Culture: How to Create a Flourishing Workplace

Company culture has become a buzzword, particularly in the post-COVID era, with more organizations recognizing the critical importance of a healthy workplace. During the Great [...]

Integrity in the Workplace (What It Is & Why It’s Important)

Integrity in the workplace matters. In fact, integrity is often viewed as one of the most important and highly sought-after characteristics of both employees and [...]

Neurodiversity in the Workplace: A Strengths-Based Approach

Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in the workplace is a priority for ethical employers who want to optimize productivity and leverage the full potential [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (50)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (22)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Download 3 Free Work & Career Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Download 3 Work & Career Exercises Pack (PDF)

Why Job Crafting Is the Secret to Job Satisfaction

Job crafting is the key to job satisfaction. but how does it work.

Posted November 10, 2020

- What Is a Career

- Find a career counselor near me

Who is ultimately in charge of your job satisfaction? Your options are your supervisor, human resources, or top management . Got your answer?

It's actually a trick question. The answer is "you." The days of assuming that top management will push down a directive to human resources, who will then push down a system to be executed by a manager, is not only idealistic, it's outdated.

Organization-level, one-size-fits-all solutions don't work. You are in charge of ensuring that you are fulfilled, challenged, and happy, and the key to doing so is job crafting —proactive, employee-driven customization of tasks and relationships with others.

The idea of job crafting is as old as the idea of work itself. Only recently have scholars and practitioners alike begun to realize that it increases job satisfaction and work engagement while reducing boredom and burnout .

But job crafting is not for the faint of heart. It takes self- and other-awareness and a willingness to stimulate change, which in some cases creates conflict. Read on to ensure that you're thinking through the possibilities and potential implications.

But first, consider taking my free, validated, and theoretically grounded assessment, " Do You Know How to Job Craft? " This 12-question assessment will automatically generate your scores and a comparison to your peers.

The Four Types of Job Crafting

Increasing Structural Resources

If you're feeling like you're unable to get as much done as you'd like, consider evaluating opportunities to increase your structural resources, which entails finding opportunities for more autonomy or more avenues for getting work done efficiently and effectively.

The most popular way of doing this is by seeking out opportunities for increased discretion in how your work is conducted. Another important element of increasing structural resources is ensuring that you have the time to complete the work that you think is necessary to accomplish strategic, long-term goals , and not just short-term deliverables.

Increasing Social Resources

Increasing social resources entails constructing opportunities for feedback, advice, or mentorship. To fully realize your potential, it will be necessary to get ideas and suggestions from others.

If you feel like you're not getting new, thought-provoking insight, it might be time to proactively seek out alternative contacts. Further, if you feel that you aren't being challenged to think differently or think bigger, it might be time to find better social resources.

Keep in mind that social resources aren't always internal. Look outside your team, department, division, and company, to find your ideal support system.

Increasing Challenging Demands

Increasing challenging demands consists of pursuing projects and assignments that allow one to develop new skills. If you are feeling bored or uninterested in your work assignments, it might be time to increase your challenging demands.

Seeking out new challenges not only helps you stay engaged, but it can also be a necessary strategy for ensuring that you stay relevant. Although it might feel comfortable to have a handle on your work tasks, it's important to spend a small percentage of your time on challenging assignments that help you round out your skillset.

The best way to get started is by talking to your direct manager. If there aren't opportunities readily available, the next step is branching out into new areas of your organization. Start by sitting in on new projects. Eventually, you'll be asked to join in.

Decreasing Hindrance Demands

Decreasing hindrance demands entails shedding stressful tasks or relationships. Consider keeping track of your tasks and communications for the next two weeks. For each task and relationship, evaluate the degree to which it is energy-depleting. These are your opportunities for decreasing hindrance demands.

In many cases, it's as simple as discontinuing the task altogether. In some cases, it's about declining to work on initiatives that are not fulfilling or entail working with draining colleagues.

There are also situations where you need to be strategic and begin having conversations with colleagues or managers about re-negotiating your role. If it's stressful enough, even this more drastic option is worth considering.

The Future of Job Crafting

The nature of job crafting is quickly evolving. Below are three trends to look out for to ensure you’re staying on top of your opportunities to enhance your job satisfaction.

Collaborative Crafting

Job crafting is no longer just an individual phenomenon. Employees are also engaging in collaborative crafting , whereby individuals within dyads or teams trade-off and negotiate responsibilities.

The challenge is that it's difficult to monitor and manage the revised responsibilities stemming from these informal arrangements. It also assumes that everyone is willing and able to make mutually beneficial changes.

Optimizing Demands

A fifth job crafting dimension is on the rise. It's called optimizing demands , which entails simplifying the job and making work processes more efficient. This is a hybrid approach that simultaneously reduces stress and increases productivity .

Optimizing demands, by definition, is beneficial for the individual and the organization. While this win-win might not always be possible, it's the ideal approach.

Idiosyncratic Deals

A related but unique concept, idiosyncratic deals (I-deals), is also becoming popular. I-deals entail formally negotiating for customized flexible work arrangements. Instead of waiting for organizations to create options, employees are proactively asking for what they want, explaining why they want it, and offering something in exchange (e.g., less pay, less responsibility, etc.).

Organizations need to be clear on I-deal policies. On the one hand, it has promise for increasing employee satisfaction and retention, but on the other hand, it has the potential to create inefficiencies and intra-team competition .

Cautions and Caveats of Job Crafting

It's important to understand the limitations of job crafting. In a recent blog post, I wrote about the different types of work fit , including person-job fit, person-organization fit, and person-vocation fit.

Keep in mind that job crafting can fix person-job misfit , but it can't overcome systemic issues such as misalignment with organizational values (i.e., person-organization misfit ) or a lack of identification with your profession (i.e., person-vocation misfit). You must be in-tune with the problem you are trying to solve.

It's also critical to keep in mind that job crafting might not always be well-received by others. For example, job crafting might force colleagues to change in ways that they don't want to change . Relatedly, uninformed superiors might rate job crafters as low performers because they are spending time on unassigned responsibilities.

When it's all said and done, you, not your organization, are responsible for your job satisfaction . It's important to take stock of your options and approach strategically. Further, to ensure that job crafting doesn't lead to a backlash, it's important to consider the rationale for your potential job adjustments and your surrounding organizational circumstances.

Visit www.scottdust.com for more free resources for human capital enthusiasts.

Scott B. Dust, Ph.D., is a management professor at the University of Cincinnati. His writings offer evidence-based perspectives on leading oneself and others.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Job crafting.

- Fangfang Zhang , Fangfang Zhang Curtin University

- Sabreen Kaur Sabreen Kaur Independent scholar

- and Sharon K. Parker Sharon K. Parker Curtin University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.832

- Published online: 15 September 2022

It is difficult and sometimes impossible for organizations to design jobs that fit all employees due to increased complexity and uncertainty in the workplace. Scholars have proposed that employees can make changes to their jobs themselves by engaging in job crafting. Job crafting is defined as self-initiated change that employees make in their work to better fit their abilities, needs, and preferences. Employees can craft their jobs individually and collaboratively, as a team. Two main theoretical perspectives have been proposed, which are distinct in how they define job crafting. The application of these two job crafting perspectives has brought some confusion about the construct of job crafting and how it is measured, and has resulted in some challenges in synthesizing empirical studies. To reduce this confusion, scholars have integrated the two distinct job crafting paper; we begin by introducing the definitions and measurements of individual job crafting and team job crafting. Specifically, theories of job crafting are reviewed from two perspectives using three distinct categorizations, with approach crafting versus avoidance crafting identified as the most important. A great number of empirical studies have been conducted to investigate the consequences of job crafting and factors that affect it. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown positive effects of approach job crafting for employees, such as increased job satisfaction, motivation, work engagement, organizational commitment, and job performance, and decreased strain and turnover intentions. However, avoidance crafting has been associated with burnout and lowered job performance. Organizational factors and individual factors that affect individual job crafting have been identified, including job autonomy, organizational support, leadership, proactive personality, self-efficacy, and regulatory focus. Beyond antecedents and outcomes of job crafting that have been systematically reviewed in the literature, studies on job crafting have also (a) empirically tested the interrelationships of different job crafting constructs, (b) uncovered new forms of job crafting, (c) unraveled the complicated effects of job crafting, (d) unpacked the influences of social context in job crafting process and outcomes, (e) considered job crafting in different populations and contexts, (f) investigated the effect of cultural differences on job crafting, and (g) investigated antecedents and outcomes of team job crafting. Finally, evidence has shown that job crafting behaviors can be trained: intervention studies show the effectiveness of job crafting interventions in stimulating job crafting behaviors and related positive outcomes such as well-being, engagement, and performance.

- work design

- individual job crafting

- team job crafting

- performance

- intervention

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Psychology. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 03 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

Longitudinal Job Crafting Research: A Meta-Analysis

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 06 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Likitha Silapurem ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9070-7995 1 ,

- Gavin R. Slemp 1 &

- Aaron Jarden 1

384 Accesses

1 Altmetric

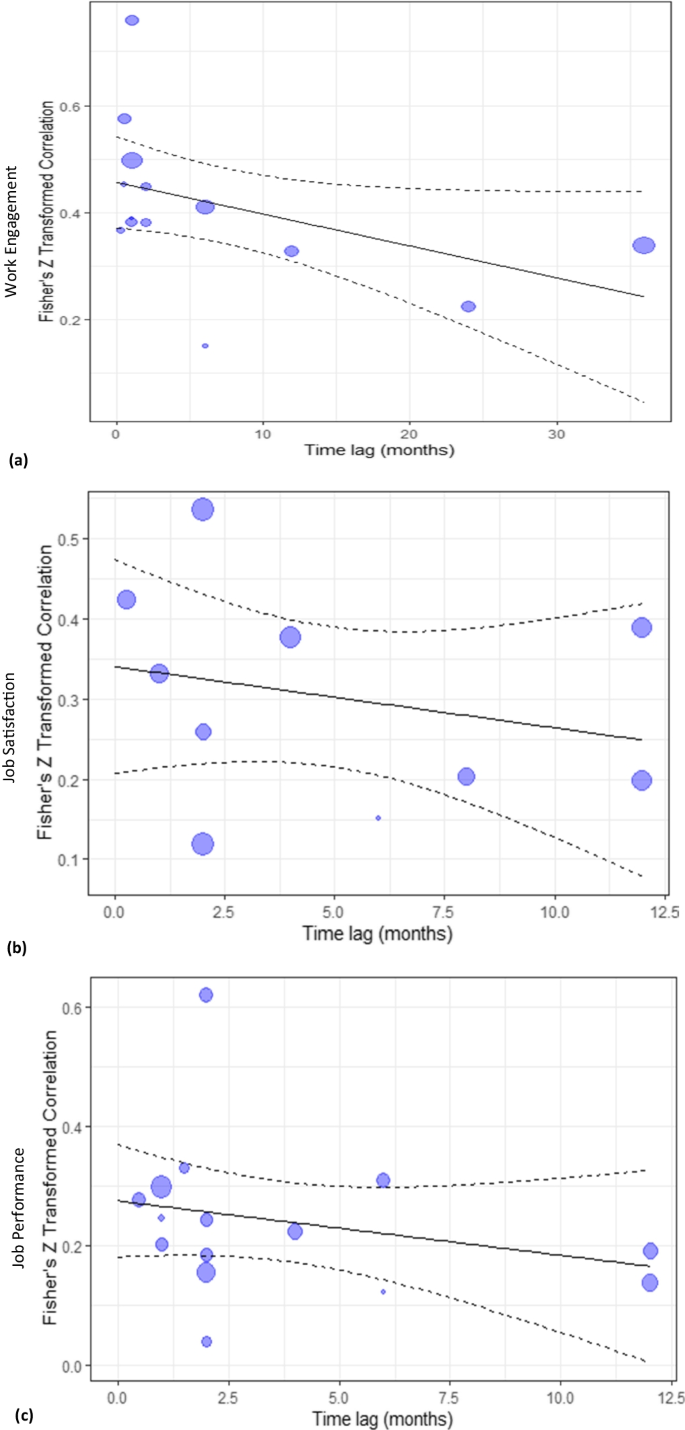

Explore all metrics

This study updates and extends upon previous meta-analyses by examining the key antecedents and outcomes within the longitudinal job crafting literature. Using a robust statistical approach that disattenuates correlations for measurement error, we further extend past work by exploring the moderating effect of time on the relationship between job crafting and its key correlates. A systematic literature search gathered all current longitudinal research on job crafting, resulting in k = 66 unique samples in the current analysis. Random-effects meta-analysis was conducted for overall job crafting and also for each individual facet of job crafting dimensions. Results showed that both overall job crafting and the individual facets of job crafting had moderate to strong, positive correlations with all variables included in this analysis, except for burnout and neuroticism which were negatively associated. A similar pattern of findings was largely present for all individual facets of job crafting. The exception to this was decreasing hindering demands crafting that had weak, negative associations with all correlates examined, except for burnout where a moderate, positive association was found. Findings from the moderation analysis for work engagement, job performance, and job satisfaction showed that although there was a clear downward trend of correlational effect sizes over time, they did not reach significance. The current study contributes to the job crafting literature by advancing previous meta-analyses, demonstrating the effect that job crafting has on positive work outcomes for both the employee and organisation over time. We conclude by exploring the implications for future research and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations

Work-life balance: an integrative review.

Work–Life Balance: Definitions, Causes, and Consequences

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Job crafting (Tims & Bakker, 2010 ; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001 ) is a job design approach that employees use to modify their work so that it better aligns with their values, motives, and needs, thereby promoting wellbeing and flourishing at work (Frederick & VanderWeele, 2020 ). In the face of ongoing organisational change and uncertainty, specifically through modern advancements which have fostered a more digitalised and flexible workplace, recent research has shown that employee-driven job redesign behaviours such as job crafting, offer a promising practical alternative to previously used traditional employer-led, top-down job re-design approaches (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019 ; Rudolph et al., 2017 ). Previous reviews have synthesized the existing research on job crafting to understand the benefits and implications of job crafting for both employees and organisations (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019 ; Rudolph et al., 2017 ). However, we estimate that as much as 50–55% of the current literature on job crafting is cross-sectional, thus not making it possible to empirically discern whether job crafting is a temporal antecedent or an outcome of the variables examined.

In addition to experimental research, which is often time-consuming and expensive to conduct, longitudinal research is one possible methodological design that can be used to establish associations between variables over time, and determine the temporal order between variables, providing a stronger base for causal inference. To date, there have been two meta-analyses that aggregate longitudinal research on employee job crafting behaviour (Frederick & VanderWeele, 2020 ; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019 ). These reviews combine the literature on job crafting within different work contexts (i.e., the settings or factors that influence the nature of work) and examine the effect this has on work content (i.e., factors that are controlled by the employee including the job demands and resources). Yet these reviews either contain effects that are biased downward by measurement error (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019 ), or contain effect sizes that are difficult to interpret due to the statistical aggregation across multiple different research designs (e.g., experimental, time-lagged designs; Frederick & VanderWeele, 2020 ). Thus, the first objective of the current study is to build upon the extant longitudinal job crafting literature and use psychometric meta-analysis to establish effect size estimates that are more easily interpretable. Second, we aim to examine the moderating effect of time on the relationship between job crafting and key correlates. In doing this, we provide stronger evidence to draw temporal inferences between job crafting and the commonly measured variables in the literature, and furthermore, provide insight into the long-term correlates of job crafting, an area which has received limited attention.

The remainder of the introduction is structured as follows. First, we outline the key conceptualisations present in job crafting research. Next, we review the current job crafting literature including existing meta-analytical reviews of job crafting. Finally, we examine time lag as a moderator in this analysis, that then leads to the aims and main research questions for this analysis.

1 Theory and Research Questions

1.1 job crafting.

Job crafting sits within the field of positive psychology (Seligman, 2002 ), specifically positive organisational scholarship (Wrzesniewski, 2003 ) which focuses on interventions aimed at promoting and enhancing employee wellbeing, rather than preventing and/or treating illbeing. Positive psychological interventions like job crafting, aim to cultivate positive feelings, behaviours and cognitions in participants to have an overall positive effect on wellbeing (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009 ). Although different approaches exist within the job crafting literature, the two most common approaches are the role-based approach (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001 ) and the resources-based approach (Tims & Bakker, 2010 ). In the role-based approach, Wrzesniewski and Dutton ( 2001 ) reviewed the literature on proactive job behaviour and suggested that employees can make changes to their work environment in three ways: 1) by altering the scope, number, sequence, or type of tasks, known as task crafting ; 2) by adapting the quality and/or amount of interaction and human connection at work known as relational crafting ; and 3) by reframing how they perceive the tasks within it, known as cognitive crafting . Tims and Bakker ( 2010 ) utilized the job demands and resources model (JD-R; Bakker & Demerouti, 2007 ) to define job crafting. This model suggests that employees seek to increase their job resources at work, while working to reduce problematic job demands. They refined this idea into four dimensions: 1) increasing structural job resources crafting (e.g., crafting more autonomy, and opportunities to develop oneself); 2) increasing social job resources crafting (e.g., crafting more social connections and support from colleagues); 3) increasing challenging job demands crafting (e.g., crafting more tasks and job responsibilities); and 4) decreasing hindering job demands crafting (e.g., crafting ways to have fewer emotional and cognitive demands). While there is much overlap between both perspectives, the omission of cognitive crafting from the Tims and Bakker’s ( 2010 ) model, as well as the lack of distinction between expansion (i.e., expanding the scope of the job by increasing job resources) and contraction (i.e., narrowing the scope of the job by decreasing demands) oriented behaviours regarding Wrzesniewski and Dutton’s ( 2001 ) task, relational and cognitive crafting, has let to further refinements and the theoretical integration of both models (Bindl et al., 2019 ; Zhang & Parker, 2019 ).

More recent models of job crafting are underpinned by regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1997 ), and are thus known as, ‘promotion and prevention crafting’ (PPC; Bindl et al., 2019 ; Zhang & Parker, 2019 ) or as ‘approach and avoidance crafting’ (Bruning & Campion, 2018 ). Promotion-focused job crafting (i.e., altering the job to increase positive outcomes), is geared toward pleasure attainment and employees obtaining and creating favourable outcomes to bring about change (Higgins, 1997 ; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019 ). Such an approach aligns with increasing job resources, challenging job demands, and expansion-oriented task, relational and cognitive crafting aspects of previous job crafting models (Slemp & Vella-Brodrick, 2013 ). Prevention-focused job crafting (i.e., altering the job to reduce negative outcomes) is associated with the avoidance of pain, and reflects people’s need for safety, security and the avoidance of negatives states where needs are not satisfied (Higgins, 1997 ; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019 ). Prevention crafting aligns with decreasing hindering job demands, and contraction forms of task, relational and cognitive crafting (Bindl et al., 2019 ; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019 ). By combining the previous conceptualisations of job crafting, this new model of promotion and prevention crafting encompasses both the tangible and intangible changes that employees can create in work boundaries. This approach allows for a clearer definition of job crafting behaviour, thereby creating a stronger model for future research.

Despite the varying conceptualisations, published literature on job crafting has grown considerably over the last ten years. Much of this growing interest is due to the substantial research showing the benefit of job crafting on individual work outcomes such as work engagement, job satisfaction, wellbeing (Rudolph et al., 2017 ), job performance (Bohnlein & Baum, 2020 ) and burnout (Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019 ). While certain work characteristics such as work experience (Niessen et al., 2016 ) and job autonomy (Sekiguchi et al., 2017 ) may present more opportunities for employees to craft their job and thus facilitate job crafting behaviour, typically, research has shown that the positive effect of job crafting is consistent across a range of organisational contexts and cultures, suggesting that all employees may be able to benefit from crafting their job despite their occupation or working condition. Furthermore, the collective evidence suggests that job crafting is associated with benefits not just for individual job crafters, but also work teams and organisations. For instance, studies have shown that team job crafting is positively associated with individual performance (Tims et al., 2013 ), team performance (McClelland et al., 2014 ), and team innovativeness (Seppala et al., 2018 ). Similarly, job crafting is positively associated with organisational citizenship behaviour (Guan & Frenkel, 2018 ; Shin & Hur, 2019 ), organisational commitment (Wang et al., 2018 ), and negatively associated with turnover (Esteves & Lopes, 2017 ; Vermooten et al., 2019 ; Zhang & Li, 2020 ), which, if we accept these reflect causal relationships, can lead to substantial financial benefits for organisations (Oprea et al., 2019 ).

Despite such research findings, much of the current literature on job crafting is cross-sectional, which poses some challenges for the field (Rindfleisch et al., 2008 ). Although cross-sectional research is beneficial in giving us a snapshot of the association between variables (Levin, 2006 ), there are two primary limitations that pertain to this study design. First, it is more prone to common method variance (CMV; i.e., the systematic method error due to the use of a single rater or source; Podsakoff et al., 2003 ), which means effect sizes are generally biased upwards. Second, due to a single measurement at one point in time, cross-sectional data places constraints on the ability to infer the direction of associations (Rindfleisch et al., 2008 ). Our estimates reveal that around 52% of the current research on job crafting is cross-sectional in nature, suggesting that concerns regarding the lack of interval validity in cross-sectional research leading to potentially inflated associations, may be applicable to the job crafting literature (Ostroff et al., 2002 ). For instance, despite overwhelming evidence showing a positive, moderately strong relationship between job crafting and work engagement in cross-sectional research (Rudolph et al., 2017 ), there have been smaller and more varied effects among intervention studies (Oprea et al., 2019 ), and randomized control trials (Sakuraya et al., 2020 ). Thus, to confirm findings from cross-sectional research and to attain a more accurate representation about how job crafting is associated with its key correlates, insights from more sophisticated research designs that help reduce these limitations are needed.

One of the main ways that researchers recommend reducing the threat of CMV bias is by gathering data over multiple time periods (Ostroff et al., 2002 ; Podsakoff, 2003 ; Rindfleisch et al., 2008 ). Fortunately, there have been numerous individual longitudinal studies conducted within the job crafting literature to determine the key outcomes of job crafting using such designs. Although there are some exceptions, findings amongst longitudinal studies also lend support to the hypothesis that job crafting predicts future positive work outcomes, such as person-job fit, meaningfulness, flourishing, job performance, and job satisfaction (Cenciotti et al., 2017 ; Dubbelt et al., 2019 ; Kooij et al., 2017 ; Moon et al., 2018 ; Robledo et al., 2019 ; Tims et al., 2016 ; Wang et al., 2018 ). There are currently two meta-analyses that have examined longitudinal literature on job crafting (see Frederick & VanderWeele, 2020 ; Lichtenthaler & Fischbach, 2019 ). Lichtenthaler and Fischbach ( 2019 ) found that prevention-focused job crafting at Time 1 had a positive relationship with work engagement and a negative relationship with burnout at Time 2. They also found an inverse relationship with prevention-focused job crafting, which showed a negative relationship with work engagement, and positive relationship with burnout at Time 2. Using Tims and Bakker’s ( 2010 ) framework, Frederick and VanderWeele ( 2020 ), found a positive relationship with job crafting at Time 1 and work engagement at Time 2.

However, while this evidence is promising, these reviews contain methodological limitations that warrant a new meta-analysis to help overcome them. For instance, the statistical analysis used to calculate the meta-analytic correlations in Lichtenthaler and Fischbach ( 2019 ) does not correct for measurement unreliability in the predictor or criterion, which may lead to a downward bias in effect sizes (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015 ; Wiernik & Dahlke, 2020 ). Similarly, Frederick and VanderWeele’s ( 2020 ) meta-analysis is limited insofar as it included both observational longitudinal studies, as well as intervention studies, in the same analysis. Because results from different study designs tend to differ systematically, this may lead to increased, as well as artificially introduced, heterogeneity (Higgins et al., 2019 ). Thus, such approaches may serve to establish effect size estimates that are some what difficult to interpret. In meta-analyses, it is important to take account of the fact that experimental studies, such as randomized control trials (RCTs) of intervention studies, generate effect sizes in fundamentally different ways than do observational studies (Borenstein et al., 2009 ; Deeks et al., 2019 ). For instance, effects from RCTs (for quasi-experimental trials) are generated by comparing the degree to which groups change over time, whereas observational studies generate effects by quantifying the strength of association between variables. Another notable difference is that in intervention studies, participants are actively trained in job crafting behaviours, whereas in observational studies, participants are untrained and observed in their natural work setting (Borenstein et al., 2009 ). Because both research designs are used to examine fundamentally different types of research questions, we suggest that it a new meta-analysis is needed so that so that study designs can be separated during the analysis (Higgins et al., 2019 ).

In sum, these issues suggest that a new investigation on longitudinal studies is needed to determine true effect sizes within this literature. In doing this, improved accuracy on the actual strength of association between job crafting and its key antecedents and outcomes will be identified.

1.2 Time Lag as a Possible Moderator of Effects

In addition to building upon previous meta-analyses, we also aim to generate insight into the effect of time on the relationships between job crafting and its key outcomes. Previous research suggests that, in addition to reducing CMV, longitudinal research allows one to examine the way in which the relationships change as a function of time (Ford et al., 2014 ). This has long been recognized in the job crafting literature (e.g., Oprea et al., 2019 ; Rudolph et al., 2017 ), yet there has been little consideration to the effect of time lags on effect sizes. Such a situation is unfortunate as time lags over which variables are measured are very likely to influence effect size magnitudes. Thus, to better understand whether job crafting is stable over time in longitudinal research, the optimal time lag must be considered. Without this insight, drawing conclusions about the stability of job crafting over time may be inaccurate without also taking into the account the specific time period in which stability is measured. Similarly, in cases where experimental manipulation is not possible, a proxy for understanding causal processes shows that one variable (e.g., job crafting) is able to predict later levels of a presumed outcome (e.g., work engagement; Card, 2019 ). An understanding of these predictive relations over time are critical goals in cumulative science, which we address here.

Given the above, the aim of the current study was to address two research questions:

Research Question 1 : What are the most prevalent antecedents and outcomes of the longitudinal job crafting literature, and how strongly is job crafting related to these variables?

Research Question 2 : To what extent does time lag influence the strength of relationships between job crafting and its key antecedents and outcomes?

In addressing these research questions, we aim to overcome existing methodological limitations present in the literature. In contrast to existing meta-analyses which use longitudinal studies and examined work engagement, burnout and performance we contribute to advancing knowledge by examining the key antecedents and outcomes of job crafting that have been studied in the literature to date, rather than focusing on a select few. Finally, in order to further advance the field of job crafting, we examine the moderating effect of time lag.

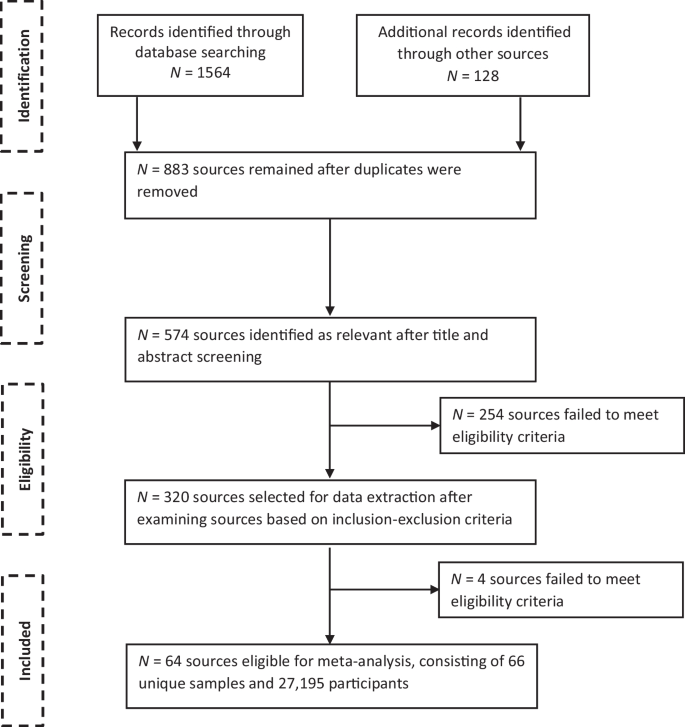

2.1 Literature Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed to retrieve all possible sources on job crafting, from which only longitudinal studies were included in the current meta-analysis. In line with best practice guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Appelbaum et al., 2018 ; Rudolph et al., 2020 ; Siddaway et al., 2019 ), we employed a variety of search strategies to systematically search for studies that examined the longitudinal antecedents and consequences of job crafting. First, to retrieve both published and unpublished sources, we conducted a literature search using eight databases that covered both published and unpublished literature: Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC), Business Source Complete (searched through Ebscohost), Web of Science Core Collection, Medline, PyscINFO, Open Dissertations, ProQuest Theses and Dissertations, and Scopus. Our search covered all years to April, 2020. In line with literature search strategies recommended by Harari et al. ( 2020 ), we consulted a university librarian to help select the most relevant databases and also to select search terms for our literature search.

In line with current conceptions of job crafting (Slemp & Vella-Brodrick, 2013 ; Tims et al., 2012 ; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001 ), we ran the search using the following base terms: “job”, “task”, “relational”, “cognitive”, “increasing structural demands”, “increasing social job resources”, “increasing challenging job demands”, “decreasing hindering job demands,” which were combined with “crafting” using the Boolean operator “AND”. This was done to ensure that the search only returned sources that had at least one of the base terms, as well as “crafting” in the title, abstract or key words. Second, we searched Google Scholar for sources that cited papers that are associated with the most commonly used measures of job crafting (Slemp & Vella-Brodrick, 2013 ; Tims et al., 2012 ). Third, we examined the reference lists of key meta-analyses for relevant longitudinal studies.