CREATIVE WRITING

Mar 29, 2019

710 likes | 1.45k Views

CREATIVE WRITING. A step by step guide at KS4. What you just HAVE to do. 1) EXPLORE IDEAS Be imaginative 2) ENTERTAIN YOUR READER Give them something to think about 3) PLAN Gather ideas and organise their order. How do I start?. WHAT?. HOW?. WHY?.

Share Presentation

- explore ideas

- first things

- still undecided

- friend family teacher

- interesting connectives

Presentation Transcript

CREATIVE WRITING A step by step guide at KS4

What you just HAVE to do... 1) EXPLORE IDEAS Be imaginative 2) ENTERTAIN YOUR READER Give them something to think about 3) PLAN Gather ideas and organise their order

How do I start? WHAT? HOW? WHY? DUNNO HOW? WHAT?

FIRST THINGS FIRST..... • Decide on what the task is...

Answer these 5 Questions: • 1 - WHAT have I been asked to write? • (Is it a certain genre, or any, if its Creative?)

2 - WHY have I been asked to write? • PURPOSE - To show creativity and entertain the reader

3 - WHO am I writing for? • Imagine your intended reader – it will decide your ‘voice’ and how you showcase your writing Friend Family Teacher / examiner Stranger Diary / self

4 - WHO are you writing as? • yourself? – 1st person • Narrating a personal “other’s” story – i.e. You – 2nd person • Referring to another – 3rd person And who are they?

5 – WHAT is the TOPIC? • So what is it all about? • What happens to who? • Where? • How? • Why? • Consider the following images for inspiration...

Planning & Structure • After you’ve answered those 5 questions, and you’ve decided on a topic...... • ORGANISE YOUR THOUGHTS • ....NB. if you’re still undecided on a topic, fill in some of the following plan, and it could help you decide • ...furthermore, if you’ve already started or drafted a story, this can help make sure you are addressing the essentials

Your story needs a STRUCTURE... • A beginning... • (any story needs an interesting introduction) • A development • (a build up of the storyline) • A crisis • (an interesting situation that provides a turning point in story) • A resolution • (things are sorted out...?)

Your story needs CHARACTERS • Make them believable and interesting • Any more than 2 or 3 will be just names • Really get under the skin of them by describing: • What they look like • What they say • How they say it • How they behave • How they feel

DIALOGUE • Speech adds variety to your story • It develops your characters and plot • (careful it doesn’t become ‘he said’- ‘I said’) • You can exhibit mastery of punctuation • Make it realistic

Finally: LANGUAGE • Make it descriptive – using adjectives and adverbs • Use powerful nouns and verbs for effect • Use literary features to create imagery and effect e.g. simile, alliteration, personification • Use interesting connectives to link ideas, and link your paragraphs • And most importantly of all:

Vary the length of your sentences! • This shows you are in control of your writing • Short sentence – builds suspense • Long sentence – gives more detail • Use a combination of simple, compound and complex sentences • Make use of subordinate clauses, (which vastly improve your writing, despite being the most forgotten aspect of writing!)

So...take your time...plan it... and enjoy it! It’s something purely of your imagination,hence YOU ARE IN CONTROL

- More by User

Creative Writing

Creative Writing. Star Stories. What can you see?. The Ancient Greeks joined up the stars to make. The Great Bear. But how did it get there?. Click here to read the story of the Great Bear. CLICK HERE. However, different people see different things. In Britain, we see

482 views • 15 slides

Creative Writing. Get to know me Get to know you Class procedures and expectations What is creative writing?. Agenda for today. Front Side : Your name, largely and clearly 4 corners: Top Left : symbol to figuratively represent your summer

869 views • 15 slides

289 views • 10 slides

Creative Writing. Unit 1 Poetry. Syllabus Review. The signed syllabus is due on Monday 1/13/14. 1/7/14 Journal #1. Aliens are among us, but they are not what we expected…. Literal Language. Basic, straightforward language without anything creative or clever. Literal: Figurative:

1.75k views • 110 slides

Creative Writing. LITERARY NONFICTION UNIT. VOICE IN WRITING. Introduction: Purpose, Diction, Tone, Syntax. Quick Write: Why do people read/ write? Give as many reasons as possible. Also, generally speaking, why do you read/write?. John Green's Thoughts.

1.54k views • 122 slides

Creative Writing. VOICE IN WRITING. Introduction: Purpose, Diction, Tone, Syntax. Quick Write: Why do people read/ write? Give as many reasons as possible. Also, generally speaking, why do you read/write?. John Green's Thoughts. Why is a writer’s PURPOSE important?.

698 views • 51 slides

Throughout your academic career you probably wrote a million papers, each about a different boring novel or science experiment, but school probably didn’t train you increative writing. Writing a story is much different than a paper, in many ways far more difficult. http://www.creative-writing.biz/

283 views • 10 slides

Creative Writing. 10 Tips for Writing Poetry. Writing is no trouble: you just jot down ideas as they occur to you. The jotting is simplicity itself - it is the occurring which is difficult. - Stephen Leacock What does this quote mean? How can this meaning be applied to poetry?.

1.88k views • 30 slides

Creative Writing. Tuesday , September 13, 2011. Today’s Targets. To identify and understand the requirements and expectations of the class To form a positive dynamic. Word of the Day (from www.dictionary.com). misnomer mis -NO- muhr , noun :

305 views • 8 slides

Creative Writing . Creative Non-fiction writing unit 8. 3/24/2014 Journal Prompt #34. The vacation cottage you rented for the summer has a locked room, which you break into and …. foreshadowing. Clues that hint of events that have yet to occur. CREATIVE NON-FICTION.

669 views • 29 slides

Creative Writing. Tuesday, January 24, 2012. Presentation Schedule. Presentations today. Presentations Thursday. Rondeau Sestina Cento. Haiku and lune Triolet Cinquain /limerick Villanelle Pantoum (possibly). Friday. Any unfinished presentations Sort poems for portfolio

211 views • 6 slides

Creative Writing. By Aaron Kurtz. The Problem. Introduction. Poetry Children’s Books Short Stories. Poetry ~ Inspiration. Popular Authors Shel Silverstein The Giving Tree Where the Sidewalk Ends Robert Frost Poems Getting Ideas Brainstorming Random activities Topic prompts.

345 views • 13 slides

Creative Writing. Write about an idea for a story that you might want to tell. Minimum 5 sentences. Objective. By the end of this lesson you should be able to identify the following ideas about fiction: Protagonist Antagonist Conflict Complications Shifts of power Crisis Falling action

891 views • 44 slides

Creative Writing. Write a poem that depends on air Write a poem invested in space Write a poem that has odd line breaks Write a poem about a park Write a poem where you don’t get it. Larry Eigner. Read. Read Eigner’s selected poems While you read: Make one observation Ask one question.

331 views • 12 slides

Creative Writing. Creating a character. Starter. Take a few minutes to imagine the relationships among the characters in the following painting. Assume the role of one of the pictured figures and write a dramatic monologue. What do you understand that no one else does?

398 views • 14 slides

Creative Writing. Wednesday, January 4, 2012. Word of the day (dictionary.com). malinger muh -LING- guhr , intransitive verb : To feign or exaggerate illness or inability in order to avoid duty or work .

250 views • 14 slides

Creative writing

Creative writing. School-leaving exam. General information 2 parts 60 minutes altogether you can use a dictionary (only paper book) use blue or black pen write in a readable way (illegible text won’t be evaluated)

358 views • 9 slides

Creative writing. Journals and writing circles. Journals. What is a journal? A place… for you to record ideas, observations, and perspective, to express your thoughts, to turn to for inspiration Why do we need to do this?

270 views • 11 slides

Creative Writing. Journal prompts. Journal Guidelines. Students will have a notebook they use only for journaling in this class. Students should date and title each entry. Don’t waste; write on both sides of paper and don’t skip spaces. Just start each new entry on its own page.

861 views • 59 slides

Creative Writing. 10 Tips for Writing Poetry. 10 Tips for Writing Poetry. Know your goal Avoid Clichés Avoid Sentimentality Use Images Use Metaphors and Similes Use Concrete Words, instead of Abstract Words Communicate Theme Subvert the Ordinary Rhyme with Caution

437 views • 17 slides

Creative Writing. Vocab Week 8 Great Descriptive Words. canter. The tauntaun cantered to a halt in front of the rebel base on __. Han didn’t realize that Luke made it back. He would have hurried faster had he known. V. or N. to move at a speed between a trot and a gallop. addle.

260 views • 13 slides

Creative Writing. Unit One-25 Common Literary Terms Session 3. Review. Give an example of Consonance Denotation Hyperbole Imagery Internal Rhyme. Metaphor.

793 views • 21 slides

Oral presentations, session IV

2:30-3:45 p.m., featured presentation, wallenberg hall, denkmann (session a).

"Kitchen Metamorphosis" Presented by Chef Joseph Yoon

Chef Joseph Yoon, a pioneering member of The Explorers Club and Chef Advocate for the UN's IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development), leads global change as the founder of Brooklyn Bugs and the Culinary Director for the Insects to Feed the World Conference. With over 300 days of touring across five continents and regular appearances in global media, he champions the immense potential of insect agriculture, helping to reshape its significance for humanity.

Discover the inspiring narrative of Joseph's evolution as a founder and entrepreneur, delving into the pivotal lessons he gleaned as a young adult that continue to fortify his resilience in navigating present-day challenges. Gain insights into the weighty responsibility accompanying a global platform as Joseph shares his profound understanding of why uncovering one's purpose is paramount, and how unwavering conviction propels individuals forward on their life's journey.

Holden Village J-term program

Old main 117 (session b).

"It Takes a Village..." Holden Village J-term program Presented by Celeaciya Olvera, Emerson Lehman, Sylvia Hughes, Ava Coussens, Olivia Schroeder, Rachel Barry and Stephanie Le

The group of us went to Holden Village this past J-term and fell in love with the class and the experience we shared together. We will all be discussing similar themes during our trip and reflecting on the class experience overall. Overall, we want to discuss the beauty this place has and the amazing times we all shared together. It would be wonderful if more people knew about this study away option.

Native American Studies and Community Outreach

Hanson 102 (session d).

"'Home From School' and the History of Indian Boarding Schools in the United States" Native American Studies and Community Outreach faculty exploration group Presented by Paul Baumgardner, Jane Simonsen, Michael Scarlett, Adam Kaul, Kiki Kosnick, Lucy Burgchardt, Melinda Pupillo, Megan Quinn and Stacey Rodman

This presentation will include several elements. We will show a 55-minute film, "Home From School: The Children of Carlisle." This film explores the history of Indian boarding schools in the United States, as well as the current work of several Native tribes to secure the remains of Native students who died while enrolled in Indian boarding schools. We then will have a faculty panel lead a conversation about the film and recent academic and governmental initiatives related to Indian boarding schools. Following the film, we will offer a small meal for students and other attendees. This meal will emphasize several Native food products.

Japan J-Term program

Old main 28 (session e).

"Japan Unveiled: A Journey Through Culture and Adventure" Japan J-term program Presented by Morgan Janes Project advisor: Dr. Shaun Edmonds

Come and explore the wonderful culture and society of Japan through the lens of our 2024 J-term students. Discover and immerse yourself in cities like Shibuya, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Kyoto, Nara, and Nagano. This presentation will include a thorough and photographic timeline of the planned and unplanned events that took place on the trip, as well as the personal explorations of our students while they were abroad. Beyond the culture and society of Japan some scholarship information will be shared as well.

Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies

Old main 132 (session g).

"Barbie as a Feminist Icon? A Panel Discussion of Greta Gerwig's 2023 Blockbuster" Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Presented by Lexi Golab, Bailey Hacker, Elena Haffner and Kara West Project advisor: Dr. Jennifer Heacock-Renaud, chair, Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies

"The year of the girl." So named U.S. media the year 2023, a time that saw cultural expressions of girlhood take center stage, from Taylor Swift's "The Eras Tour" to Beyoncé's "Renaissance," to increased viewership for women's sports. Perhaps most representative of this trend was Greta Gerwig's 2023 "Barbie," a film that earned more than $1.36 billion across the globe. To date, it has been the highest-grossing film in the 100-year history of the Warner Brothers company and the highest-grossing film ever to come from a woman filmmaker at the domestic box office. While throngs of fans clad in pink flocked to theaters to embrace the film as a celebration of femininity, prominent conservative figures disdained the film's alleged "woke," feminist agenda and its emasculation of Kens everywhere, those plastic and human alike. Yet, the question of whether Gerwig's film indeed fashions Barbie into a feminist icon is a vexing one for feminist scholars. For decades, the Mattel company has couched the Barbie brand in a language of empowerment for girls and women, aiming to show girls that they can do and be anything. At the same time, Barbie's unhealthy body image and beauty standards, the environmental harm of mass-produced plastic, the capitalist power of Mattel, and Barbie's constant heteronormative pairing with Ken have been feminist concerns since the doll was launched in 1959. This panel seeks to unpack Barbie as a fraught cultural icon, a site onto which many of our cultural anxieties and aspirations have been projected. We will consider how Gerwig depicts and responds to patriarchy and how gender in the film intersects with other components of identity on screen, including queerness, race and ethnicity, class, and (dis)ability.

Creative Writing

Black box, brunner theatre center (session h).

"Professional Canaries: a Reading of Creative Work by Augustana Creative Writers" Creative Writing Presented by Bethany Abrams, Brooke Borchart, Caitlin Campbell, Katelyn Dennis, Olivia Devore, April Lambert, Sydney Miller, Samuel Rabideau, Taylor Roth, Hallie Weis and Corey Whitlock Project advisor: Dr. Rebecca Wee

This is a public reading of creative work by Augustana's senior creative writing students. They will read from their SI projects in a range of genres, so poetry, creative nonfiction, short stories, flash fiction and/or excerpts from longer fiction pieces and personal essays/memoir will be shared.

- Victor Mukhin

Victor M. Mukhin was born in 1946 in the town of Orsk, Russia. In 1970 he graduated the Technological Institute in Leningrad. Victor M. Mukhin was directed to work to the scientific-industrial organization "Neorganika" (Elektrostal, Moscow region) where he is working during 47 years, at present as the head of the laboratory of carbon sorbents. Victor M. Mukhin defended a Ph. D. thesis and a doctoral thesis at the Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia (in 1979 and 1997 accordingly). Professor of Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia. Scientific interests: production, investigation and application of active carbons, technological and ecological carbon-adsorptive processes, environmental protection, production of ecologically clean food.

Title : Active carbons as nanoporous materials for solving of environmental problems

Quick links.

- Conference Brochure

- Tentative Program

Scriabin Association

Founded to celebrate scriabin, scriabinism and scriabinists…, the texts of scriabin’s works: some observations of a performer-researcher-teacher. by simon nicholls.

The handwriting of any individual is a kind of self-portrait, and reading a handwritten letter can give an indication of the writer’s character and state of mind, and of his or her attitude to the content of the letter. An author’s manuscript often yields valuable information about the creative process; the manuscripts of Dickens or Dostoevsky provide many examples. Examining such a document is a very different experience from reading a novel in cold print. With a musical manuscript, the spacing, the character of the pen-strokes and of the musical handwriting, as well as details of layout which cannot always be exactly reproduced by the process of engraving, give similar information, valuable to the student and to the performer. Beyond factual information, the visual impression of the manuscript, the Notenbild , can be a direct stimulus from the composer to the interpreter’s imagination. In this way, study of the composer’s manuscript can lead both to a narrowing of the possibility of textual error and to a widening of the possibilities of imaginative response to interpretation.

Examining the manuscripts of any great composer or literary author is always a thrilling experience. I have spent many hours studying Scriabin’s manuscripts in the Glinka Museum, Moscow, which holds in its vast archive many fair and rough copies of complete works as well as sketches by Scriabin. The first thing which strikes one is the extreme beauty and clarity of the scores. The slender exactitude of the writing and drawing corresponds to the delicacy and transparency of Scriabin’s own playing of his music, and makes it clear to the interpreter that a similar clarity, precision and grace is demanded in his or her own performance – something extremely difficult to achieve. The care with which the manuscripts were prepared confirms the testimony of Scriabin’s friend and biographer, Leonid Sabaneyev, who was bemused by the care taken by the composer in the placing of slurs, the choice of sharps or flats in accidentals (contributing in many cases to an analysis of the harmony concerned), the spacing of the lines of the musical texture over the staves and the upward or downward direction of note stems.

It was Heinrich Schenker who pointed out the expressive and structural significance of the manuscript notation of Beethoven, and who was instrumental in establishing an archive in the Austrian National Library, Vienna, of photographic reproductions of musical manuscripts. His pioneering work has led gradually to the present wealth of Urtext editions and facsimiles of many composers’ manuscripts. Reproductions of Skryabin’s manuscripts have been published by Muzyka (Moscow), Henle (Munich) and the Juilliard School (New York; their manuscript collection is available online). [1] These reproductions cover several significant compositions by Scriabin: Sonata no. 5, op. 53; Two pieces, op. 59; Poème-nocturne, op. 61; Sonata no. 6, op. 62; Two poèmes, op. 63; Sonata no. 7, op. 64. The remarks below have no pretensions to system or completeness; they are merely observations based on initial study, and intended as a stimulus to others to examine the manuscripts for themselves.

In maturity, Scriabin took immense care with his manuscripts. Speaking to Sabaneyev, he compared the difficulty of writing down a conception in sound to the process of rendering a three-dimensional object on a flat surface. As a student and as a young composer, though, Scriabin was by no means ideally accurate or painstaking in his notation. This was the cause of Rimsky-Korsakov’s irritated response to the manuscript score of Scriabin’s Piano Concerto – the elder composer initially considered it to be too full of mistakes to be worthy of serious attention. Mitrofan Belaieff, Scriabin’s publisher, patron and mentor, frequently begged the composer to be more careful in correcting proofs. The original editions, particularly of the early works, contain many errors which originate in some cases from Scriabin’s manuscript and in others from poor proofreading – as far as we can tell; some early manuscripts are now lost.

We are indebted to the fine musician Nikolai Zhilyayev for correct editions of Scriabin’s music. Zhilyayev knew Scriabin well and discussed many misprints with the composer; others he detected by his own scrupulous and scholarly work and prodigious memory. As Scriabin’s harmony and voice-leading were impeccably systematic and logical at all stages of his development, those who have had to do with the old editions will know that is often possible to correct mistakes by analogy or knowledge of harmonic style.

Zhilyayev was the revising editor for a new edition of Scriabin’s music, published by the Soviet organisation Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo muzykal’nyi sektor (State publisher, musical division – ‘Muzsektor’) from the 1920s on, each work or opus number being issued separately. These beautifully prepared editions are painstakingly annotated, corrections being indicated in two layers: those discussed with the composer and therefore beyond doubt, and those which Zhilyayev considered likely (and he was usually right). This work was the basis of the complete edition of the piano music published by Gosudarstvennoe muszykal’noe izdatel’stvo (State musical publishing house – ‘Muzgiz’) in three volumes (1947, 1948 and 1953). [2] Zhilyayev fell victim to Stalin’s terror; he was arrested in 1937 and shot in the following year. His name does not appear on this three-volume edition.

A new complete edition is appearing gradually under the imprint Muzyka–P. Jurgenson. The general editor is Valentina Rubtsova, biographer of Scriabin and head of research at the Scriabin Museum, Moscow, assisted by Pavel Shatsky. As in Rubtsova’s editions for Henle, full credit is given to Zhilyayev, and the annotations as to origins and variants are very thorough in this valuable new edition.

A very limited number of Scriabin’s manuscripts has been available in facsimile until now. The collection of ‘Youthful and Early Works’ prepared by Donald Garvelmann and published in New York in 1970 by Music Treasure Publications [3] contains a facsimile of the early E flat minor sonata (without opus number) of 1889, a typical youthful manuscript of the composer, rather heavy in its style of penmanship. The manuscript of the op. 11 preludes (excerpts are shown in ill.1), though tidier, shows a similar style.

ill. 1) Extract of Op. 11 Preludes manuscript

The Russian website ‘Virtual’nye vystavki’ (‘Virtual exhibitions’) [4] gives in facsimile the first page of the Etude op. 8 no. 12, with more fingering than is shown in the Belaieff edition, and also the first page of the manuscript score of the Poem of Ecstasy , providing a striking example of the change in the composer’s manuscript style. A facsimile on the site of the first two pages of the score of the Piano Concerto shows some of the copious blue-pencilling of Rimsky-Korsakov from the occasion mentioned earlier, and the site also reproduces Skryabin’s letter of apology to Rimsky-Korsakov apologising for the errors and blaming neuralgia. [5] Comparison of this letter with the one to the musicologist N. F. Findeizen dated 26 December 1907, also viewable on the site, gives another clear example of the change in Scriabin’s handwriting. [6]

Op. 53: Sonata no. 5

A facsimile of the Fifth Sonata has been published by Muzyka. [7] The manuscript of this work was presented to the Skryabin Museum, Moscow, by the widow of the pianist and composer Alfred Laliberté, to whom Scriabin had given the manuscript. This is a very different document from the early E flat minor sonata manuscript, and shows Scriabin’s fastidious and calligraphically exquisite mature hand. By this time both Scriabin’s music manuscript and his handwriting had developed an elongated ‘upward-striving’ manner. We might make a comparison with the remark of Boris Pasternak that the composer ‘had trained himself various kinds of sublime lightness and unburdened movement resembling flight’ [8] – the handwriting is expressive of this quality. Examples of Scriabin’s handwriting in letters to Belaieff in 1897 (ill. 2) and to the composer and conductor Felix Blumenfeld in 1906 (ill. 3) show the dramatic difference in handwriting style that developed.

ill. 2) Scriabin’s handwriting 1897

ill. 3) Scriabin’s handwriting 1906

The manuscript of the Fifth Sonata shows that, although Scriabin spoke French, he did not immediately provide a French text for the epigraph, which is from the verse Poem of Ecstasy . This poem was written in Russian at the same period that the symphonic poem was composed. There is a request on the manuscript to the engraver to leave space for a French version. The French text, which is the usual source of English translations, does not reflect the Russian with complete accuracy: the forces mystérieuses , ‘mysterious forces’, which are being called into life are skrytye stremlen’ya , ‘hidden strivings’, in the original. [9] In other words, it is open to doubt that any sort of ‘magical ritual’, in a superstitious sense, is being depicted in this work, a suggestion made (perhaps in a figurative sense) by the early writer on Scriabin Evgenii Gunst and elaborated upon by the composer’s British-American biographer, Alfred Swan. The epigraph may be regarded as an invocation of Scriabin’s own inner aspirations, the creative power which the composer equated with the divine principle.

Work on the Fifth Sonata started in 1907, at a period when a rift had developed between Scriabin and the publishing house of Belaieff. The committee running the publishers after the death of Belaieff had proposed a renegotiation of fees. It is possible that Scriabin was unaware of the preferential and generous treatment Belaieff had accorded him; certainly, he was offended by the proposals and withdrew from his agreement with the publishers. The Sonata was published at Scriabin’s own expense, but was taken into the publishing concern run by the conductor Serge Koussevitsky, Rossiiskoe muzykal’noe izdatel’stvo (RMI). Later still, Scriabin quarrelled with Koussevitsky too, and the composer’s last works were published by the firm which had brought out his very first published compositions, Jurgenson.

The main differences between the manuscript of the Fifth Sonata and most modern printed texts are:

1) a missing set of ties at the barline between bars 98 and 99. These ties are also missing in RMI, and in the edition printed at Scriabin’s own expense. [10] Muzgiz adds the ties in dotted lines, by analogy with the parallel passage at bars 359–360. The commentary to the Muzgiz edition states that sketches of the work make use of an abbreviated notation at this point which could have led to this misunderstanding, as the editors describe it. Christoph Flamm’s notes to the Bärenreiter edition are definite as to Scriabin’s intention not to tie over this barline, citing the repetition of accidentals in bar 99 as being conclusive proof. [11]

2) the movement of the middle voice in bars 122–123, 126–127, 136–137, 383–384, 387–388, 397–398 ( Meno vivo sections): the manuscript gives a downward resolution in the middle voice (d flat – c in the first passage and g flat – f in the second) whereas the printed editions give an upward resolution (d flat – d natural and g flat – g). It is as if only at a second attempt (as revised for the printed version) has Scriabin fully realised the implications of his own (then very new) harmony: the resolutions as printed resolve into the augmented harmony around them, whereas the resolutions in the earlier version do not. Knowing about this early version, moreover, adds point to the grandiose version of the same section at bars 315–316, 319–20 and 323–324, where the downward resolution is retained. One might think of the meno vivo sections as being potential states, and the grandiose version as representing a fully realised condition.

It should be remembered that the Sonata was composed at breakneck speed, completed in a few days, and revised afterwards; Valentina Rubtsova, editor of the facsimile, suggests that the manuscript provides a glimpse into the composer’s creative laboratory. She further points out that Scriabin uses double barlines to indicate structural divisions, whereas publishers’ house style often requires a double bar at any change of key-signature or time-signature. This has resulted in the insertion of a number of non-authentic double bars in some published versions of the Fifth Sonata. Double bars occur in the manuscript in the following places only:

before bar 47 (beginning of main sonata exposition)

before bar 120 ( Meno vivo , the second subject area)

before bar 367 (indicating, perhaps a slight hesitation before this rising sequence)

before bar 381 (parallel passage to bar 120).

The visual effect of the manuscript is therefore more continuous than that of the printed edition. It should be mentioned that the Urtext printed version given in the volume containing the manuscript is a corrected version of the RMI edition. This edition was prepared with the composer’s agreement and during his lifetime. The manuscript, though, is an invaluable source for the reasons given above.

A similar use of double barlines to that in the Sonata no. 5 is made elsewhere by Scriabin, including in the Sonata no. 6 (see below) and the Sonata no. 8. It can be said, from these examinations, that Scriabin uses double barlines structurally or even expressively, and that they often should be made audible in some way, in sharp contradistinction to the purely ‘grammatical’ double bars referred to above. The definition of ‘sometimes’ and ‘often’ is a non-scientific one and comes down to the player’s own interpretive insight, but where there is a double barline and no change of time- or key-signature, the double bar clearly has structural significance.

The addition of a double bar by a publisher can confuse the interpreter. For example, Bach’s engraved edition of his own Second Partita has no double bar, in fact no barline at all, at the beginning of the third section of the Sinfonia (ill. 4.) The insertion of a double bar at this point, even in some ‘Urtext’ editions (because of the change of time-signature) leads many performers to treat the final chord of the middle section like a ‘starter’s pistol’ for the quicker final section, which, as consideration of the musical content will quickly demonstrate, starts on the second quaver of the bar with the fugue subject.

ill. 4) Manuscript of Sinfonia from Bach’s Keyboard Partita no. 2

The notes by Valentina Rubtsova to the facsimile of the Fifth Sonata mention Scriabin’s differing use of rallentando in its full version and of the abbreviation rall. , and the possible implications of such usage for performance:

[…] in b. 382 Scriabin indicated molto rallentando , while in b. 386 and 390 he confined himself to [a] shortened and somewhat careless rall. It seems that the theme sounded to him just like that: with a more substantial broadening in b.382 and in a somewhat generalized manner in b. 386 and 390. [12]

A related expressive function of details in the writing of performance directions will be noted below in the case of the Poème-Nocturne , op. 61.

Now we move to a group of Scriabin’s manuscripts, recently published on line by the Juilliard School of New York. The works with opus numbers 52, 53 and 58 to 64 were published by Koussevitsky’s firm, RMI, mentioned above. (The Poem of Ecstasy , op. 54, was already contracted to Belaieff, as were opp. 56 and 57; there is no work with the number 55.) Opp. 59 and 61 to 64 (op. 60 is an orchestral score, Prometheus ) were bound together in one volume at some time. Koussevitsky’s archive went with him when he left Russia in 1920. The majority of the archive is now in the Library of Congress, but this volume somehow came onto the open market, and was sold at Sotheby’s in 2000. The purchaser, Bruce Kovner, businessman, collector and philanthropist, generously donated his entire collection to Juilliard School in 2006, and Juilliard have made the contents of the volume he purchased available in excellent facsimile online [13] – a huge step forward in making Scriabin manuscript facsimiles available to the musical public. The Sonata No. 7 has also been published in an equally excellent facsimile by Henle with informative notes by Valentina Rubtsovsa. [14] Some observations on these manuscripts follow.

Op. 59 no. 1, Poème

b. 15: an accidental is missing before the r. h. d sharp, third quaver of the bar. This mistake, as well as the missing accidental in b. 13, was reproduced in the first edition, but corrected by Zhilyayev.

b.19: the fifth quaver in r. h. is spelled in the manuscript as b double flat, harder to read than the a natural printed in most editions, but consistent with the d flat bass of this bar and typical of Scriabin’s fastidiousness in his choice of accidentals. The spelling was reproduced in the first edition, but altered without comment by Zhilyayev, who did not have the manuscript available. (This manuscript was also not available to the editors at the time of preparation of the Muzyka-Jurgenson edition.) Subsequent editions, including Muzyka-Jurgenson, followed Zhilyayev’s reading. The ‘spelling’ of a note may well have an effect on the player of a wind or string instrument as regards actual pitch, and Sabaneyev discussed this with Scriabin. But a good pianist will often respond by minute adjustments of touch to the difference of inner hearing caused by enharmonic differences of spelling. [15]

b. 23–25: there is evidence in these bars of erased octave doublings in the right hand phrases, though the lower octave to the initial a, r.h. second quaver of bar 23, has not been erased – a mistake rightly queried by the editor. Here, the texture is delicate and transparent, but it will be remembered that Scriabin often preferred single notes to octaves in passages of powerful sonority where an effect of brightness was desirable (e.g. final climaxes of the Fifth Sonata and Vers la Flamme ). Sabaneyev criticised the composer for scoring his orchestral music with doublings at the unison rather than the octave, but this seems to have been Scriabin’s preference in many places.

b. 28 and 30: The three r.h. quavers which continue the middle voice at the end of these bars were first written by Scriabin in the upper staff, but then erased and put into the lower staff, clarifying the voice-leading. This is an example of the care taken by the composer in the optical presentation of his voices.

b. 34: the manuscript and the first edition have d natural in r.h. upper voice, second, fourth and sixth quavers. This error was corrected by Zhilyayev, who changed these notes to d sharps, noting the analogy in bar 6.

b. 36: the tie between third and fourth quavers of the bar in r.h. is missing in the manuscript, but was supplied in the first edition – possibly a correction in proof by the composer.

b. 38: the acciaccatura at the beginning of the bar for both hands was written by Scriabin with a quaver tail without the customary cross-stroke. This seems to have been the composer’s usual habit – compare the beginning of the Sixth Sonata, written in the same way, as well as other instances – and, in the case of the present Poème, the notation was altered in the first edition. The RMI edition of the Sonata, however, shows the acciaccatura with a quaver-type tail, though many later editions add a cross-stroke. It may be felt that in both cases Scriabin’s notation may suggest a more deliberate execution of the acciaccaturas.

b.39: note the beautiful and unusual notation of the final sonority, a single stem uniting sounds many octaves apart and played by two hands. It is suggestive of the deep and strange sonority of this ending. It is given by most editions, but not by Peters, who ‘normalise’ the notation here. [16]

Op. 59 no. 2, Prelude

A number of errors in the manuscript were correctly questioned by the editor, and further inconsistencies were corrected by Zhilyayev.

The rhythm at the beginning of bar 40, though, (marked avec defi – Scriabin omitted the acute accent on the second letter of défi ) written as three even quavers, was retained in the first edition and subsequent ones despite having been questioned by the editor. Muzgiz, following Zhilyayev, queries whether it should be made consistent with the dotted rhythm of other similar bars. The Peters edition by Günter Philipp adopts this suggestion. [17] The present writer is of the opinion that the three even quavers help to express Scriabin’s suggested ‘defiance’.

Intriguingly, a slip of paper was pasted over the original manuscript at bars 26–28. This is at the position, characteristic of Scriabin’s short pieces, where the opening material begins to be repeated in transposition. The repeated chords on the paper slip, which anticipate the coda from bar 54 to 57, may have been a late compositional addition by Scriabin. (Other paper slips are observable, pasted into the manuscript of the Sonata no. 6.)

Op. 61, Poème-Nocturne

(The manuscript of this work was also not available to the editors of Muzyka-Jurgenson, who were, however, able to consult a rough draft, as in the case of op. 59.)

Space will not permit a detailed analysis of longer works such as this, but some interesting features present themselves. The first page of the manuscript is written in two inks, blue and black. On the first system, the clefs and the r.h. phrase from the downbeat of bar one are written in blue, whereas the upbeat is written in black. A list of incipits for projected works by Scriabin exists in the Glinka Museum archives, and has been examined by the present writer. This list corresponds to a description by Sabaneyev of a collection of thematic material ‘for sonatas’. In the list, the Poème-Nocturne theme lacks its upbeat. Perhaps the addition of the upbeat was a late inspiration, like Beethoven’s last-minute addition of a two-note upbeat to the slow movement of the Hammerklavier sonata. At the recapitulation, b. 109, the theme starts on the downbeat.

In bar 3 and the corresponding passage, bar 110, Scriabin writes the molto più vivo directly over the l. h. figure on the second beat. This is placed too late in Muzgiz, but correctly in Muzyka-Jurgenson.

Scriabin’s usual practice is to write his performance directions or remarki in lower-case letters, but in the Poème-Nocturne and some other works this practice is departed from in certain places. The new ideas at bar 29 and 33 are marked in the manuscript Avec langueur and Comme en un rêve – suggesting, perhaps, that the arrival of these new ideas should be ‘shown’ by the player in some way, possibly by a very slight elongation of the rests before them, as with the start of a new sentence or paragraph in a text which is read aloud. The same thing happens at Avec une soudaine langueur ( sic ) in bar 52, and Avec une passion naissante and De plus en plus passionné in bars 77 and 79. The first edition reproduces this peculiarity, but not Muzgiz or Muzyka-Jurgenson. It has not been possible to determine whether they are following Zhilyayev, as seems likely. [18]

The addition in printed editions, including the first, of a poco acceler. [ sic in RMI] over the barline of bb. 46-47 is clear evidence of intervention by the composer at proof stage.

The long slur at comme un murmure confus (bar 103 to 110) is correctly reproduced in the editions known to this writer, but seeing it drawn so clearly and with such certainty in the manuscript is a reminder not to yield to the temptation to ‘explain’ the structure of this mysterious passage, and especially not to render the arrival of the recapitulation in bar 109 with any excessive degree of clarity. The piece reflects Scriabin’s exploration of states of consciousness on the borders of sleep, as he explained to Sabaneyev. On the other hand, the remarka at the point of arrival of the recapitulation ( Avec une grace [sic] capricieuse [19] ) does have the capital letter we have come to expect in this work when important thematic ideas are presented.

Op. 62: Sonata no. 6

This work is so successfully suggestive of dark areas of the spirit that a listener once suggested to the present writer, after a performance of the Sixth Sonata, that the music was evidence of psychosis in the composer’s own mind. The listener was, of course, making an error like that of Don Quixote at the puppet show – mistaking dramatic presentation for reality. The lucidity of the manuscript, as well as the highly organised and disciplined musical structure, show that Scriabin knew very well what he was doing.

Towards the end of the work there is a notorious high d written, which exceeds the range of the keyboard (bar 365). This note has also been quoted to me by music-lovers as evidence of Scriabin’s supposed delusional condition. Firstly, it should be pointed out that the d is dictated by analogy with bar 330. We can make a comparison with Ravel in this case. In the climax of Ravel’s Jeux d’eau there is a bottom note which, harmony dictates, should be G sharp, but as the note does not exist on most keyboards, Ravel wrote A. [20] Similarly, Ravel ‘faked’ octaves at the bottom of the piano in the recapitulation of Scarbo by writing sevenths. Scriabin, ever an idealist, preferred to write the pitch required by the music and to leave the solution to the interpreter. [21] Furthermore, the whole phrase from bar 365 to 367 is written an octave lower in the manuscript than in the first edition, thus bringing the d within the keyboard range. [22] An explanation for the late change between manuscript and first edition, which transposes the phrase up an octave, may be that Scriabin never performed this very difficult work – the premiere was entrusted to Elena Beckman-Shcherbina. Perhaps, in working on the piece with her and hearing the passage played up to tempo, Scriabin suggested that she try the phrase an octave higher, as the analogy with bar 330 demands, and realised that the chord flashes by with the substitution of c for d as the top note practically unheard. In her memoirs, Bekman-Shcherbina describes Scriabin’s detailed work with her on his compositions, but, alas, gives no details of the work which must have taken place on the Sixth Sonata.

The composer’s notation of the acciaccatura which starts the Sixth Sonata has already been mentioned (see above, Poème op 59 no. 1.) As in the case of the acciaccatura which sets off the Sonata in A minor by Mozart (K.310), this opening should not be played too glibly, but with a certain weight. Indeed, for a player whose hand cannot stretch the initial chords, it is a help to know that this arresting opening should not be hurried over. More importantly, an execution on the slow side helps to emphasise the sombre, unyielding severity of the opening sonority. It is perhaps unfortunate that publishers’ ‘house styles’ lead to a routine ‘correction’ of Scriabin’s notation of the acciaccatura.

‘House style’ has also led to the omission in some editions of the Sixth Sonata of a number of ‘structural’ double bars provided in the manuscript by Scriabin. Scriabin wrote double bars before b. 92 (coda of exposition), 124 (beginning of development), 206 (recapitulation), 268 (end of recapitulation of second subject. As this last-mentioned place involves a change of time signature, the double bar is technically required, and is reproduced in printed editions, but there is a definite break in the atmosphere here.) The calligraphic beauty and clarity of b. 244–267, a notoriously complex passage, repays study.

Op. 64: Sonata no. 7

The manuscript of Sonata no. 7 is commented upon in detail by Valentina Rubtsova in her notes to the facsimile published by Henle, and these notes are published online. [23] They repay careful study, and Rubtsova gives an account of the other manuscript versions of the Sonata, one of which the present writer has examined in the Glinka Museum. The existence of this text, with its many alterations and differences from the finished version, calls into question the accusation, made by Sabaneyev and since repeated, that Scriabin established a ‘scheme’ of empty numbered bars and proceeded to ‘fill’ it with music. While numbers were clearly important to the composer in establishing a ‘crystalline’ form, the procedure of composition was far more complex than that, as the painstaking work shown in these manuscripts reveals.

Ill.5 is a reproduction of the first page of Scriabin’s earlier draft, with the remarka ‘Prophétique’ for the opening ‘fanfare’ motive. This marking, later rejected, gives a sense of the gesture of this musical idea, which is essential to the close connection of the Sonata with Scriabin’s idea of the ‘Mystery’, something he discussed with Sabaneyev. While visiting an exhibition in London’s Tate Gallery of paintings by the English artist George Frederic Watts (1817–1904), the present writer was struck by the convulsive, ‘prophetic’ gesture depicted in Watts’ ‘Jonah’ (1894), a painting which is reproduced online. [24] The performance of these opening bars needs to be as striking and dramatic as Watts’ painting.

ill. 5) 1st page from manuscript of Sonata 7

Op. 63, 2 Poèmes

In the second of these short works, some l. h. notes in the chords in b. 6 and 7 have been erased; these notes are relocated to the upper stave, where they belong musically, and marked m.g. (The m.d. in bar 7 is a characteristic slip, rightly questioned by the editor). The top note of these chords is shown in the manuscript as f natural and was so published in the RMI edition. Zhilyayev, who had discussed this passage with the composer, corrected this to f sharp. [25] The first notation shows how essential the gesture of hand-crossing was to Scriabin’s conception of the sonority here. Some pianists make the simultaneity of sounding of notes into a priority, but a letter by Scriabin to Belaieff which has been dated to December 1894 shows that spreading of chords was essential to his conception at times (such spreading was, in any case, far more prevalent at that period than now). In this letter, Scriabin writes that the ‘wide chords’ in bb. 9-10 of the Impromptu op. 10 no. 2 ‘must be played by the left hand alone, for the character of their sonority in performance depends on this.’ [26]

The Scriabin facsimiles which have been made available in Russia and America are invaluable sources of information and inspiration, and studying them brings us just a little nearer to the composer. It is hoped that the notes above will encourage players and music lovers to investigate them, and also that more facsimiles may follow in the future.

Simon Nicholls, 2016.

[1] http://juilliardmanuscriptcollection.org/composers/scriabin-aleksandr/

[2] This edition was the basis of those of the sonatas, preludes and etudes reprinted by Dover, though some of the editions chosen for reprinting contained errors not present in the complete edition. Dover did not reproduce the essential information that nuances and rubatos given in brackets in these editions, notably in the op. 8 etudes, were from instructions given by Skryabin to Mariya Nemenova-Lunts while she was studying with the composer.

[3] This edition was republished in limited numbers by the Scriabin Society of the U.S.A.

[4] http://expositions.nlr.ru/ex_manus/skriabin/index.php

[5] The letter is dated ‘19 th April’ by Scriabin and dated to 1896 on the website. The edition by Kashperov of Scriabin’s letters (A. Scriabin, Pis’ma , Muzyka, Moscow, 1965/2003, attributes it to 1897 (p. 168–169, letter 144.)

[6] This letter is given by Kashperov ( op.cit. ) on p. 492–3, letter no. 545.

[7] Scriabin: Sonata no. 5, op. 53. Urtext and facsimile. Muzyka, Moscow, 2008.

[8] Boris Pasternak, An Essay in Autobiography , trans. Manya Harari, Collins and Harvill, London, 1959, p. 44.

[9] I am grateful to the distinguished scholar of Russian literature Avril Pyman for pointing this out (private communication). The French text was added by hand by the composer to the proofs of the first edition (information from the notes by Christoph Flamm to Skrjabin: Sämtliche Klaviersonaten II, Bärenreiter, 2009, p. 43), but perhaps we should trust Scriabin’s Russian, his native tongue, rather than his French in this case.

[10] Ibid. , p. 44.

[11] Muzgiz, vol. 3, commentary, p. 295. Christoph Flamm, loc. cit. The printed version supplied in the Muzyka edition of the facsimile adds the ties in dotted lines, following Muzgiz. It is certainly tempting to make the ‘correction’: most pianists play the tied version, which persists in many editions. But such bringing into line of parallel passages should not be done automatically.

[12] Valentina Rubtsova, notes to facsimile of Scriabin Sonata no. 5, p.57.

[13] Cf. n. 1, above.

[14] Alexander Skrjabin: Klaviersonate Nr. 7 op. 64. Faksimile nach dem Autograph. G. Henle Verlag, Munich, 2015. The foreword is also available online: http://www.henle.de/media/foreword/3228.pdf

[15] Cf. Paul Badura-Skoda, Interpreting Mozart on the Keyboard , trans. Leo Black, Barrie & Rockliff, London, 1962, p. 290 for a brief discussion of one example of this problem. Brahms wrote against any attempt to improve on Chopin’s orthography at the time of the preparation of a new complete edition of the Chopin piano works (letter to Ernst Rudorff, late October or early November 1877, quoted in Franz Zagiba, Chopin und Wien , Bauer, Vienna, 1951, p.130.) All this comment is made about a single accidental because the orthography of Scriabin’s late music is such a wide-reaching, fascinating and important topic, perhaps seen by some students of the music only as an irritating difficulty of reading, and this is one small example of it. For a discussion of Scriabin’s orthography and its significance see George Perle, ‘Scriabin’s Self-Analyses’, Music Analysis, Vol. 3 no. 2 (1984), p. 101–122.

[16] Skrjabin, Klavierwerke III , ed. Günter Philipp, Peters, Leipzig 1967.

[17] Ibid . Philipp notes the variant in an editor’s report, p. 98.

[18] Christoph Flamm discusses Scriabin’s remarki , and comments that the composer accepted with indifference the publishers’ treatment of his upper or lower-case letters ( op. cit. , p. 42). Nonetheless, these small ms. differences can be infinitely valuable suggestions to the performer. Flamm points out that even the size of the letters in which a remarka is written can be of significance for the performer.

[19] Scriabin spoke good French, but accents sometimes go missing in his writing. This circumstance could perhaps be compared with his tendency to miss out accidentals.

[20] The present writer has read a gramophone record review in which this famous bass note was described as a ‘wrong note.’

[21] The Austrian piano firm Bösendorfer added a few bass notes to the range of its largest instruments. Apart from making Ravel’s bass notes possible to ‘correct’, the bass strings add to the resonance of the piano. No such advantage attaches to an addition to the top of the keyboard.

[22] Noted by Darren Leaper.

[23] Cf. n. 15, above.

[24] http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/watts-jonah-n01636

[25] Muzgiz, vol. 3, commentary, p. 296.

[26] Kashperov, op. cit. , p. 87.

Marc Chagall and Jewish Theater, Part One

by Jeanne Willette | Nov 11, 2016 | Modern , Modern Art

Marc Chagall in Moscow

The murals for the jewish theater.

To the end of his life, Marc Chagall remained circumspect about his ouster from the People’s Art School in Vitebsk. And the coup against the artist was no small event. Chagall had been appointed by none other than the People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment, Anatoly Lunacharsky (1875-1933), an old friend from their days in Paris, living in the artists’ building, known as La Ruche. Moe than the friendly connection with the new government, there was the symbolic gesture of Lunacharsky appointing a Jewish head of an art school for the people, indicating the end of the Pale of the Settlement, or the erasure of the line that had kept Jews cordoned off and separated from non-Jewish Russians since 1791. Under Catherine the Great and Alexander II, areas beyond the original borders of Russia had been annexed, especially Poland, which continued a large number of Jews. The “Pale of the Settlement,” a phase coined by Nicholas I, scooped up, so to speak, much of this new population, which was subject to restrictions on their movements. For the most part, these restrictions were to eliminate economic competition from Jews and the travel restrictions were based upon a policy of restricting the comings and goings of Russians in general. After centuries, suddenly, in 1917, all Russians were equal, opening unimaginable vistas for Jews who were filled with hope for the future. Therefore, to remove a friend of Lunacharsky and a Jewish artist over aesthetic differences could have been a dangerous move for Chagall’s “enemies,” Kazimir Malevich and El Lissitzky. But, Chagall, embittered, removed himself from the unpleasant situation and left Vitebsk for Moscow and a new project. Writing sadly about these difficult days, the artist later wrote sadly,

I would not be surprised if, after such a long absence, my town effaced all traces of me and would no longer remember him who, laying down his own brush, tormented himself, suffered and gave himself the trouble of implanting Art there, who dreamed of transforming the ordinary houses into museum and the ordinary habitants into creative people. And I understood then that no man is a prophet in his own country. I left for Moscow.”

Marc Chagall. The Fiddler (1912)

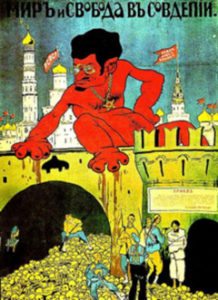

Chagall walked into a pause in the historical Russian penchant for anti-Semitism. For the Russians, the war had just ended but during the Great War, local prejudices against Jews ran high. Over six hundred thousand Jews were ousted from their homes by the army and the historical pograms led by Cossacks increased–all because Jews were being scapegoated and blamed for the military’s difficulties with the Germans. But after the War, the government policy towards Jews changed abruptly. The significance of the sudden surge or influx of Jewish culture into the mainstream of Russian society rests upon political changes that went beyond the Revolution itself. When one looks at a list of prominent Bolshevik leaders of the October Revolution, it become clear that the majority were Jewish. According to Mark Weber’s article “The Jewish Role in the Bolshevik Revolution and Russia’s Early Soviet Regime,”

With the notable exception of Lenin (Vladimir Ulyanov), most of the leading Communists who took control of Russia in 1917-20 were Jews. Leon Trotsky (Lev Bronstein) headed the Red Army and, for a time, was chief of Soviet foreign affairs. Yakov Sverdlov (Solomon) was both the Bolshevik party’s executive secretary and — as chairman of the Central Executive Committee — head of the Soviet government. Grigori Zinoviev (Radomyslsky) headed the Communist International (Comintern), the central agency for spreading revolution in foreign countries. Other prominent Jews included press commissar Karl Radek (Sobelsohn), foreign affairs commissar Maxim Litvinov (Wallach), Lev Kamenev (Rosenfeld) and Moisei Uritsky. Lenin himself was of mostly Russian and Kalmuck ancestry, but he was also one-quarter Jewish. His maternal grandfather, Israel (Alexander) Blank, was a Ukrainian Jew who was later baptized into the Russian Orthodox Church. A thorough-going internationalist, Lenin viewed ethnic or cultural loyalties with contempt. He had little regard for his own countrymen. “An intelligent Russian,” he once remarked, “is almost always a Jew or someone with Jewish blood in his veins.”

According to Weber, over time, when anti-Semitism inevitably returned to this land of the pograms, this early history of active Jewish participation in the Revolution was obscured. But at the time, outside observers such as Winston Churchill were well aware of the role played by Jewish revolutionary leaders. “With the notable exception of Lenin, the majority of the leading figures are Jews. Moreover, the principal inspiration and driving power comes from the Jewish leaders. Thus Tchitcherin, a pure Russian, is eclipsed by his nominal subordinate, Litvinoff, and the influence of Russians like Bukharin or Lunacharski cannot be compared with the power of Trotsky, or of Zinovieff, the Dictator of the Red Citadel (Petrograd), or of Krassin or Radek — all Jews,” Churchill said–and his observations were not necessarily positive.

The most famous member of the inner circle was Leon Trotsky, targeted by an anti-Semitic cartoon from the White Army

This connection between Jews and Communism or leftism or revolutions was made by others, thus linking Bolshevikism with the Jews, with what would be tragic consequences. Rival factions in the Soviet Union were resentful of the sudden favoritism, and perhaps most unexpectedly, the ranks of the secret police were filled with Jews, also certain to former more discontent. However, in 1920, when Marc Chagall arrived in Moscow, he was part of a vanguard that would attempt to knit the Yiddish culture into Russia, an empire that once kept Jews within the Pale. Once the Jews became full citizens and were granted their rights as citizens of the Provisional Government, the explosion of Jewish culture was immediate. As Jewish Renaissance in the Russian Revolution , written by Kenneth B. Moss, explained,

Most Jews in Russia and Ukraine no doubt spent the years of the Revolution and Civil War merely struggling to survive, like most of their countrymen. But a disproportionately large minority participated in Revolutionary Russia’s tumultuous political life.Most famously, many played important roles across the spectrum of Russian radical and liberal politics..Yet for a significant cohort of intellectuals, writers, artists, patrons, publicists, teachers, activists embedded in this national intelligentsia, February also bore a second imperative..some o Russian Jewelry’s most talented men and women also threw themselves into efforts of unprecedented scale and intensity to crate what they called a “new Jewish culture.”Between February 1917 and the consolidation of Bolshevik power in 1919-1920, European Russia and Ukraine became the sites of the most ambitious programs of Jewish cultural formation that Eastern Europe had yet seen or indeed would see again.

This Yiddish culture that Chagall would animate and illustrate in the Moscow theater, the Yiddish Chamber Theater, was a folk, rather than an elite, culture. Based upon a distinctive language, Yiddish, that emerged around 1000 CE, emanating from the Ashkenazic Jews or the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, clustered in large numbers in the Russian Empire by the beginning of the twentieth century. This hybrid language, a mixture of Medieval German and Hebrew, was used exclusively by the Jews of this part of Europe. Jews from the Western nations, such as Germany, could understand smatterings of this very old language but, for Gentiles, the words would be impossible to comprehend. This point is important because the Jewish Theater, moved from Petrograd to Moscow by Lunacharsky, was intended to not just preserve and formalize a part of Russian society, previously excluded, the productions also had to be integrated and assimilated by a non-Jewish audience. For this audience, the task of interpretation was made easier by the fact that the performances were pantomime like. Given that the reception of these Yiddish literary creations would be directed to a mixed audience, the images created by Chagall had to the iconic but not stereotypical and instantly recognizable as paradigm figures of Jewish culture.

When the theater was transferred to Moscow, its name changed slightly, and, indeed, would change off and on until it was extinguished in 1949. In Chagall’s time the theater, which was unexpectedly avant-garde and experimental, was called State Yiddish Chamber Theater or GOSEKT. Under the leadership of Alexei Granovsky, the Theater in Petrograd came into being before the Revolution, the presentations were very sophisticated, devoid of kitsch and imbued with the influence of the German theater director and producer, Max Reinhardt (Maximilian Goldmann), an Austrian who worked in Berlin and reformed the naturalism of the turn of the century into a self-conscious total work of art or Gesamtkunstwerk . As Curt Levient wrote, “Granovsky had trained in Berlin with legendary director Max Reinhardt and developed a vision of theater that melded acting, set design, costumes, lighting, music, dance, movement, and gesture — even silence — into an organic whole.” In his important book on The Moscow Yiddish Theater: Art on Stage in Time of Revolution , Benjamin Harshav noted that Granovsky was persuaded by theater critic, Abram Efros, to ask the distinguished artist to paint the back drops. The “theater” was actually a confiscated home of a wealthy merchant who had fled the Bolshevik distaste for the moneyed class. The site of the actual performance was small, holding less that a hundred people who were lucky enough to enjoy the remarkable combination of Marc Chagall and Sholem Aleichem, whose play would be the inaugural production.

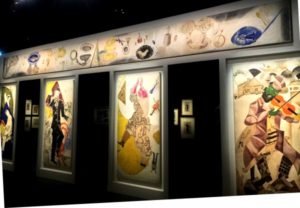

Recreation of Chagall’s Box: the Back Wall and Frieze

Working with a young group of players, none over the age of twenty-seven, Chagall had a unique opportunity in a nation at a new starting point to reset the conventions for theater, a desire he shared with Granovsky, to drag theater into the twentieth century. More than that, according to the 1993 catalogue from the Guggenheim Museum on the work of Chagall for GOSEKT (or GOSET), “Chagall presented a unique, and uniquely Jewish, approach. Through specifically Jewish visual puns, Yiddish inscriptions, and references to the festivities of Jewish weddings and Purim — a Jewish analogue to carnival in its emphasis on ludicrous masquerades and outrageous intoxication — he posited a distinctive model for the Jewish Theater.” For this occasion, Chagall produced what would later be called “Chagall’s Box,” murals which bound the theatrical world inhabited by his sets and costumes. The main set piece was a twenty-sux foot mural on the left wall, “Introduction to the Jewish Theater,” that formed the main backdrop for the three one act plays. He also painted four panels, representing the arts, placed between the windows opposite. Leaving no surface untouched, Chagall painted a frieze and the ceiling and then produced a mural called “Love on the Stage” for the back of the “theater.”

The production was so elaborate and the costumes of painted rags and dotted face make up so Chagall specific, Granovsky accepted the unique contribution but did not invite the artist and his complex and expensive schemes and motifs to do another production. And yet, the spell of Chagall lived on and subsequent set designers were impacted by his unbridled imagination that activated a magical Yiddish cast of characters. The artist was inspired by the nineteenth century authors who created Yiddish literature, Sholem Yankev Abramovitsch, who wrote under the nom de plume, Mendele Moykher Sforim, often referred to as “Mendele,” and Yitzhak Leib Peretz, both of whom elevated and incorporated a folk culture into high literature. The writer whose stories were featured in the 1921 production designed by Chagall is perhaps the most famous, Solomon Rabinovitch, who also wrote under a name other than his own, Sholem Aleichem, which is a play on an old Yiddish greeting of “peace be upon you.” On the evening of January 1st of 1921, “Evening of Sholom-Aleihem” presented two one act plays, “Agentn (Agents)” and “Mazltov,” word that needs on translation.

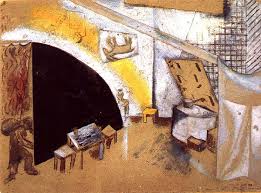

Set for Mazltov

The plays may have been classic Yiddish literature but the action was totally avant-garde , based upon Granovsky’s idea that theater began in silence and a dark room and that the actors emerged in and out of the dream space. The actors were directed or guided, as it were by a “system of dots,” something like pantomime, in which the actors would freeze and pose in place, following “an assembly of dots,” as Abram Efros put it. In other words, theater was de-naturalized and flattened with the actual actors mimicking the painted figures of Chagall, binding the surrounding “Chagall Box” to the audience and to the actors, negating the theatrical stage and turning it into a dark non-space from which characters emerged as if from a canvas, becoming the artist’s creations.

The next post will discuss the famous murals, displayed until 1925 and hidden away for another five decades.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

[email protected]

Recent Posts

- Art Deco and Women

- Le Corbusier: Purism as the Ideal City

- Le Corbusier: The Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau

- The Soviet Pavilion 1925

- Constructivism and the Avant-Garde

Top searches

Trending searches

memorial day

12 templates

17 templates

26 templates

20 templates

american history

73 templates

11 templates

Create your presentation

Writing tone, number of slides.

AI presentation maker

When lack of inspiration or time constraints are something you’re worried about, it’s a good idea to seek help. Slidesgo comes to the rescue with its latest functionality—the AI presentation maker! With a few clicks, you’ll have wonderful slideshows that suit your own needs . And it’s totally free!

Generate presentations in minutes

We humans make the world move, but we need to sleep, rest and so on. What if there were someone available 24/7 for you? It’s time to get out of your comfort zone and ask the AI presentation maker to give you a hand. The possibilities are endless : you choose the topic, the tone and the style, and the AI will do the rest. Now we’re talking!

Customize your AI-generated presentation online

Alright, your robotic pal has generated a presentation for you. But, for the time being, AIs can’t read minds, so it’s likely that you’ll want to modify the slides. Please do! We didn’t forget about those time constraints you’re facing, so thanks to the editing tools provided by one of our sister projects —shoutouts to Wepik — you can make changes on the fly without resorting to other programs or software. Add text, choose your own colors, rearrange elements, it’s up to you! Oh, and since we are a big family, you’ll be able to access many resources from big names, that is, Freepik and Flaticon . That means having a lot of images and icons at your disposal!

How does it work?

Think of your topic.

First things first, you’ll be talking about something in particular, right? A business meeting, a new medical breakthrough, the weather, your favorite songs, a basketball game, a pink elephant you saw last Sunday—you name it. Just type it out and let the AI know what the topic is.

Choose your preferred style and tone

They say that variety is the spice of life. That’s why we let you choose between different design styles, including doodle, simple, abstract, geometric, and elegant . What about the tone? Several of them: fun, creative, casual, professional, and formal. Each one will give you something unique, so which way of impressing your audience will it be this time? Mix and match!

Make any desired changes

You’ve got freshly generated slides. Oh, you wish they were in a different color? That text box would look better if it were placed on the right side? Run the online editor and use the tools to have the slides exactly your way.

Download the final result for free

Yes, just as envisioned those slides deserve to be on your storage device at once! You can export the presentation in .pdf format and download it for free . Can’t wait to show it to your best friend because you think they will love it? Generate a shareable link!

What is an AI-generated presentation?

It’s exactly “what it says on the cover”. AIs, or artificial intelligences, are in constant evolution, and they are now able to generate presentations in a short time, based on inputs from the user. This technology allows you to get a satisfactory presentation much faster by doing a big chunk of the work.

Can I customize the presentation generated by the AI?

Of course! That’s the point! Slidesgo is all for customization since day one, so you’ll be able to make any changes to presentations generated by the AI. We humans are irreplaceable, after all! Thanks to the online editor, you can do whatever modifications you may need, without having to install any software. Colors, text, images, icons, placement, the final decision concerning all of the elements is up to you.

Can I add my own images?

Absolutely. That’s a basic function, and we made sure to have it available. Would it make sense to have a portfolio template generated by an AI without a single picture of your own work? In any case, we also offer the possibility of asking the AI to generate images for you via prompts. Additionally, you can also check out the integrated gallery of images from Freepik and use them. If making an impression is your goal, you’ll have an easy time!

Is this new functionality free? As in “free of charge”? Do you mean it?

Yes, it is, and we mean it. We even asked our buddies at Wepik, who are the ones hosting this AI presentation maker, and they told us “yup, it’s on the house”.

Are there more presentation designs available?

From time to time, we’ll be adding more designs. The cool thing is that you’ll have at your disposal a lot of content from Freepik and Flaticon when using the AI presentation maker. Oh, and just as a reminder, if you feel like you want to do things yourself and don’t want to rely on an AI, you’re on Slidesgo, the leading website when it comes to presentation templates. We have thousands of them, and counting!.

How can I download my presentation?

The easiest way is to click on “Download” to get your presentation in .pdf format. But there are other options! You can click on “Present” to enter the presenter view and start presenting right away! There’s also the “Share” option, which gives you a shareable link. This way, any friend, relative, colleague—anyone, really—will be able to access your presentation in a moment.

Discover more content

This is just the beginning! Slidesgo has thousands of customizable templates for Google Slides and PowerPoint. Our designers have created them with much care and love, and the variety of topics, themes and styles is, how to put it, immense! We also have a blog, in which we post articles for those who want to find inspiration or need to learn a bit more about Google Slides or PowerPoint. Do you have kids? We’ve got a section dedicated to printable coloring pages! Have a look around and make the most of our site!

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

9. Key Differences In creative writing the most of the part is self-created, although the idea might be inspired but in technical writing the facts are to be obliged and the note is delivered from leading on what previously other greats have concluded. Most commonly, the creative writing is for general audience or for masses but technical writing is for specific audience. The creative writing ...

Creative Writing Workshop Presentation . Education . Premium Google Slides theme, PowerPoint template, and Canva presentation template . We all know how many book lovers there are in the world. Reading is one of the most satisfying activities for many people. How about you encourage your potential students to enroll in a creative writing ...

Unleash your teaching prowess with this modern, geometric-shaped presentation template in soothing shades of blue and white. Ideal for educators offering a creative writing course, this slideshow template effortlessly elevates your lesson plan, making it engaging and visually appealing. Dive into the realm of creativity and inspire young minds ...

Free Google Slides theme, PowerPoint template, and Canva presentation template. Thanks to an amazing collaboration between professor Jose Antonio Cuenca Abela and Slidesgo, we have created this creative template. It is designed to teach a creative writing workshop, and you won't have to worry about anything, because it includes 100% real ...

Download the "Creative Writing - Bachelor of Arts in English" presentation for PowerPoint or Google Slides. As university curricula increasingly incorporate digital tools and platforms, this template has been designed to integrate with presentation software, online learning management systems, or referencing software, enhancing the overall efficiency and effectiveness of student work.

Creative Writing &AcademicWriting At the end of the session, the students will be able to: 1. Differentiate creative writing from other types of writing 2. Understand the different genres of creative writing 3. Learn the initial steps in writing creatively 4. Be familiar with other techniques of creative writing 5.

Teaching Creative Writing. Jun 11, 2014 • Download as PPT, PDF •. 112 likes • 49,475 views. Rafiah Mudassir. Follow. Education Technology. 1 of 47. Download now. Teaching Creative Writing - Download as a PDF or view online for free.

These presentation templates are suitable for presentations related to writing. They can be used by authors, journalists, bloggers, or anyone in the field of literature or content creation. The templates provide a professional and creative design that will engage and captivate the audience. Get these writing templates to craft engaging ...

Premium Google Slides theme and PowerPoint template. Creative Writing School is the perfect place for budding authors to craft their masterpiece! Workshops or classes that will help others take their writing to the next level. Use this template to present your school in a very unique way, whether you're looking to present a serious approach ...

21 Get crafty (ripped paper details) Sometimes to tell a story, visual details can really help get a mood across. Ripped paper shapes and edges can give a presentation a special feel, almost as if it was done by hand. This visual technique works for any type of presentation except maybe in a corporate setting.

15 hours. Best University-level Creative Writing Course (Wesleyan University) 5-6 hours. Best Course to Find Your Voice (Neil Gaiman) 4-5 hours. Best Practical Writing Course With Support (Trace Crawford) 12 hours. Best Course to Overcome Writer's Block: 10-Day Journaling Challenge (Emily Gould) 1-2 hours.

Creative Writing workshop strategies were borrowed by, and are now standard features in, composition courses all across the country. Since the 1980s, Creative Writing has had a somewhat ambivalent, and at times downright antagonistic stance toward academic trends—especially the advent and dominance of critical theory.

One example could be a presentation covering "The Best Free Alternatives to Microsoft Office.". Memoir: Tell the stories of influential people or your own in a value-packed presentation. Video Games: You can reveal the pros and cons of a game or just talk about the trendiest games as of now.

Creative Writing. Creative Writing. Journal prompts. Journal Guidelines. Students will have a notebook they use only for journaling in this class. Students should date and title each entry. Don't waste; write on both sides of paper and don't skip spaces. Just start each new entry on its own page. 859 views • 59 slides

How to Craft a Narrative Story (38 characters. Feb 21, 2014 • Download as PPTX, PDF •. 48 likes • 69,356 views. AI-enhanced title. Susan Lewington. Another Lewington production, this time it's my 'Creative Writing' powerpoint for you to enjoy and share. Education. 1 of 27. Download now.

Creative Writing: Our Choices for 'The Second Choice" by Th.Dreiser A few weeks ago we read a short story "Second Choice" by Theodore Dreiser which stirred quite a discussion in class. So, the students were offered to look at the situation from a different perspective and to write secret diaries of some characters (the author presented them as ...

Featured presentation Wallenberg Hall, Denkmann (Session A) "Kitchen Metamorphosis" Presented by Chef Joseph Yoon. Chef Joseph Yoon, a pioneering member of The Explorers Club and Chef Advocate for the UN's IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development), leads global change as the founder of Brooklyn Bugs, and the Culinary Director for the Insects to Feed the World Conference.

Catalysis Conference is a networking event covering all topics in catalysis, chemistry, chemical engineering and technology during October 19-21, 2017 in Las Vegas, USA. Well noted as well attended meeting among all other annual catalysis conferences 2018, chemical engineering conferences 2018 and chemistry webinars.

Op. 63, 2 Poèmes. In the second of these short works, some l. h. notes in the chords in b. 6 and 7 have been erased; these notes are relocated to the upper stave, where they belong musically, and marked m.g.(The m.d. in bar 7 is a characteristic slip, rightly questioned by the editor).The top note of these chords is shown in the manuscript as f natural and was so published in the RMI edition.

Premium Google Slides theme and PowerPoint template. Creative writing is an art that can be practiced. If you are thinking of preparing a workshop to help others improve their writing skills, we have the perfect solution for you. In this infographic template we have included a multitude of resources that will help you prepare that master class ...