Ethical Decision Making Models and 6 Steps of Ethical Decision Making Process

By Andre Wyatt on March 21, 2023 — 10 minutes to read

In many ways, ethics may feel like a soft subject, a conversation that can wait when compared to other more seemingly pressing issues (a process for operations, hiring the right workers, and meeting company goals). However, putting ethics on the backburner can spell trouble for any organization. Much like the process of businesses creating the company mission, vision, and principles ; the topic of ethics has to enter the conversation. Ethics is far more than someone doing the right thing; it is many times tied to legal procedures and policies that if breached can put an organization in the midst of trouble.

- A general definition of business ethics is that it is a tool an organization uses to make sure that managers, employees, and senior leadership always act responsibly in the workplace with internal and external stakeholders.

- An ethical decision-making model is a framework that leaders use to bring these principles to the company and ensure they are followed.

- Importance of Ethical Standards Part 1

- Ethical Decision-Making Model Approach Part 2

- Ethical Decision-Making Process Part 3

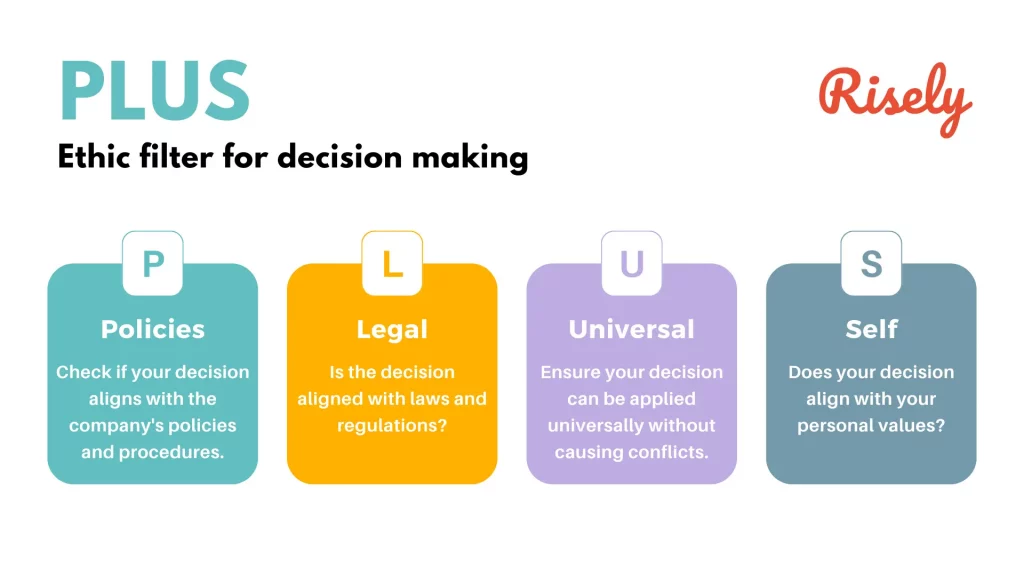

- PLUS Ethical Decision-Making Model Part 4

- Character-Based Decision-Making Model Part 5

The Importance of Ethical Standards

Leaders have to develop ethical standards that employees in their company will be required to adhere to. This can help move the conversation toward using a model to decide when someone is in violation of ethics.

There are five sources of ethical standards:

Utilitarian

Common good.

While many of these standards were created by Greek Philosophers who lived long ago, business leaders are still using many of them to determine how they deal with ethical issues. Many of these standards can lead to a cohesive ethical decision-making model.

What is the purpose of an ethical decision-making model?

Ethical decision-making models are designed to help individuals and organizations make decisions in an ethical manner.

The purpose of an ethical decision-making model is to ensure that decisions are made in a manner that takes into account the ethical implications for all stakeholders involved.

Ethical decision-making models provide a framework for analyzing ethical dilemmas and serve as a guide for identifying potential solutions. By utilizing these models, businesses can ensure they are making decisions that align with their values while minimizing the risk of harming stakeholders. This can result in better decision-making and improved reputation.

Why is it important to use an ethical decision making model?

Making ethical decisions is an integral part of being a responsible leader and member of society. It is crucial to use an ethical decision making model to ensure that all stakeholders are taken into account and that decisions are made with the highest level of integrity. An ethical decision making model provides a framework for assessing the potential consequences of each choice, analyzing which option best aligns with personal values and organizational principles, and then acting on those conclusions.

An Empirical Approach to an Ethical Decision-Making Model

In 2011, a researcher at the University of Calgary in Calgary, Canada completed a study for the Journal of Business Ethics.

The research centered around an idea of rational egoism as a basis for developing ethics in the workplace.

She had 16 CEOs formulate principles for ethics through the combination of reasoning and intuition while forming and applying moral principles to an everyday circumstance where a question of ethics could be involved.

Through the process, the CEOs settled on a set of four principles:

- self-interest

- rationality

These were the general standards used by the CEOs in creating a decision about how they should deal with downsizing. While this is not a standard model, it does reveal the underlying ideas business leaders use to make ethical choices. These principles lead to standards that are used in ethical decision-making processes and moral frameworks.

How would you attempt to resolve a situation using an ethical decision-making model?

When facing a difficult situation, it can be beneficial to use an ethical decision-making model to help you come to the best possible solution. These models are based on the idea that you should consider the consequences of your decision, weigh the various options available, and consider the ethical implications of each choice. First, you should identify the problem or situation and clearly define what it is. Then, you must assess all of the possible outcomes of each choice and consider which one is most ethical. Once you have identified your preferred option, you should consult with others who may be affected by your decision to ensure that it aligns with their values and interests. You should evaluate the decision by considering how it affects yourself and others, as well as how it meets the expectations of your organization or institution.

The Ethical Decision-Making Process

Before a model can be utilized, leaders need to work through a set of steps to be sure they are bringing a comprehensive lens to handling ethical disputes or problems.

Take Time to Define the Problem

Consult resources and seek assistance, think about the lasting effects, consider regulations in other industries, decide on a decision, implement and evaluate.

While each situation may call for specific steps to come before others, this is a general process that leaders can use to approach ethical decision-making . We have talked about the approach; now it is time to discuss the lens that leaders can use to make the final decision that leads to implementation.

PLUS Ethical Decision-Making Model

PLUS Ethical Decision-Making Model is one of the most used and widely cited ethical models.

To create a clear and cohesive approach to implementing a solution to an ethical problem; the model is set in a way that it gives the leader “ ethical filters ” to make decisions.

It purposely leaves out anything related to making a profit so that leaders can focus on values instead of a potential impact on revenue.

The letters in PLUS each stand for a filter that leaders can use for decision-making:

- P – Policies and Procedures: Is the decision in line with the policies laid out by the company?

- L – Legal: Will this violate any legal parameters or regulations?

- U – Universal: How does this relate to the values and principles established for the organization to operate? Is it in tune with core values and the company culture?

- S – Self: Does it meet my standards of fairness and justice? This particular lens fits well with the virtue approach that is a part of the five common standards mentioned above.

These filters can even be applied to the process, so leaders have a clear ethical framework all along the way. Defining the problem automatically requires leaders to see if it is violating any of the PLUS ethical filters. It should also be used to assess the viability of any decisions that are being considered for implementation, and make a decision about whether the one that was chosen resolved the PLUS considerations questioned in the first step. No model is perfect, but this is a standard way to consider four vital components that have a substantial ethical impact .

The Character-Based Decision-Making Model

While this one is not as widely cited as the PLUS Model, it is still worth mentioning. The Character-Based Decision-Making Model was created by the Josephson Institute of Ethics, and it has three main components leaders can use to make an ethical decision.

- All decisions must take into account the impact to all stakeholders – This is very similar to the Utilitarian approach discussed earlier. This step seeks to do good for most, and hopefully avoid harming others.

- Ethics always takes priority over non-ethical values – A decision should not be rationalized if it in any way violates ethical principles. In business, this can show up through deciding between increasing productivity or profit and keeping an employee’s best interest at heart.

- It is okay to violate another ethical principle if it advances a better ethical climate for others – Leaders may find themselves in the unenviable position of having to prioritize ethical decisions. They may have to choose between competing ethical choices, and this model advises that leaders should always want the one that creates the most good for as many people as possible.

There are multiple components to consider when making an ethical decision. Regulations, policies and procedures, perception, public opinion, and even a leader’s morality play a part in how decisions that question business ethics should be handled. While no approach is perfect, a well-thought-out process and useful framework can make dealing with ethical situations easier.

- How to Resolve Employee Conflict at Work [Steps, Tips, Examples]

- 5 Challenges and 10 Solutions to Improve Employee Feedback Process

- How to Identify and Handle Employee Underperformance? 5 Proven Steps

- Organizational Development: 4 Main Steps and 8 Proven Success Factors

- 7 Steps to Leading Virtual Teams to Success

- 7 Steps to Create the Best Value Proposition [How-To’s and Best Practices]

- Training & Certification

- Knowledge Center

- ECI Research

- Business Integrity Library

- Career Center

- The PLUS Ethical Decision Making Model

Seven Steps to Ethical Decision Making – Step 1: Define the problem (consult PLUS filters ) – Step 2: Seek out relevant assistance, guidance and support – Step 3: Identify alternatives – Step 4: Evaluate the alternatives (consult PLUS filters ) – Step 5: Make the decision – Step 6: Implement the decision – Step 7: Evaluate the decision (consult PLUS filters )

Introduction Organizations struggle to develop a simple set of guidelines that makes it easier for individual employees, regardless of position or level, to be confident that his/her decisions meet all of the competing standards for effective and ethical decision-making used by the organization. Such a model must take into account two realities:

- Every employee is called upon to make decisions in the normal course of doing his/her job. Organizations cannot function effectively if employees are not empowered to make decisions consistent with their positions and responsibilities.

- For the decision maker to be confident in the decision’s soundness, every decision should be tested against the organization’s policies and values, applicable laws and regulations as well as the individual employee’s definition of what is right, fair, good and acceptable.

The decision making process described below has been carefully constructed to be:

- Fundamentally sound based on current theories and understandings of both decision-making processes and ethics.

- Simple and straightforward enough to be easily integrated into every employee’s thought processes.

- Descriptive (detailing how ethical decision are made naturally) rather than prescriptive (defining unnatural ways of making choices).

Why do organizations need ethical decision making? See our special edition case study, #RespectAtWork, to find out.

First, explore the difference between what you expect and/or desire and the current reality. By defining the problem in terms of outcomes, you can clearly state the problem.

Consider this example: Tenants at an older office building are complaining that their employees are getting angry and frustrated because there is always a long delay getting an elevator to the lobby at rush hour. Many possible solutions exist, and all are predicated on a particular understanding the problem:

- Flexible hours – so all the tenants’ employees are not at the elevators at the same time.

- Faster elevators – so each elevator can carry more people in a given time period.

- Bigger elevators – so each elevator can carry more people per trip.

- Elevator banks – so each elevator only stops on certain floors, increasing efficiency.

- Better elevator controls – so each elevator is used more efficiently.

- More elevators – so that overall carrying capacity can be increased.

- Improved elevator maintenance – so each elevator is more efficient.

- Encourage employees to use the stairs – so fewer people use the elevators.

The real-life decision makers defined the problem as “people complaining about having to wait.” Their solution was to make the wait less frustrating by piping music into the elevator lobbies. The complaints stopped. There is no way that the eventual solution could have been reached if, for example, the problem had been defined as “too few elevators.”

How you define the problem determines where you go to look for alternatives/solutions– so define the problem carefully.

Step 2: Seek out relevant assistance, guidance and support

Once the problem is defined, it is critical to search out resources that may be of assistance in making the decision. Resources can include people (i.e., a mentor, coworkers, external colleagues, or friends and family) as well professional guidelines and organizational policies and codes. Such resources are critical for determining parameters, generating solutions, clarifying priorities and providing support, both while implementing the solution and dealing with the repercussions of the solution.

Step 3: Identify available alternative solutions to the problem The key to this step is to not limit yourself to obvious alternatives or merely what has worked in the past. Be open to new and better alternatives. Consider as many as solutions as possible — five or more in most cases, three at the barest minimum. This gets away from the trap of seeing “both sides of the situation” and limiting one’s alternatives to two opposing choices (i.e., either this or that).

Step 4: Evaluate the identified alternatives As you evaluate each alternative, identify the likely positive and negative consequence of each. It is unusual to find one alternative that would completely resolve the problem and is significantly better than all others. As you consider positive and negative consequences, you must be careful to differentiate between what you know for a fact and what you believe might be the case. Consulting resources, including written guidelines and standards, can help you ascertain which consequences are of greater (and lesser) import.

You should think through not just what results each alternative could yield, but the likelihood it is that such impact will occur. You will only have all the facts in simple cases. It is reasonable and usually even necessary to supplement the facts you have with realistic assumptions and informed beliefs. Nonetheless, keep in mind that the more the evaluation is fact-based, the more confident you can be that the expected outcome will occur. Knowing the ratio of fact-based evaluation versus non-fact-based evaluation allows you to gauge how confident you can be in the proposed impact of each alternative.

Step 5: Make the decision When acting alone, this is the natural next step after selecting the best alternative. When you are working in a team environment, this is where a proposal is made to the team, complete with a clear definition of the problem, a clear list of the alternatives that were considered and a clear rationale for the proposed solution.

Step 6: Implement the decision While this might seem obvious, it is necessary to make the point that deciding on the best alternative is not the same as doing something. The action itself is the first real, tangible step in changing the situation. It is not enough to think about it or talk about it or even decide to do it. A decision only counts when it is implemented. As Lou Gerstner (former CEO of IBM) said, “There are no more prizes for predicting rain. There are only prizes for building arks.”

Step 7: Evaluate the decision Every decision is intended to fix a problem. The final test of any decision is whether or not the problem was fixed. Did it go away? Did it change appreciably? Is it better now, or worse, or the same? What new problems did the solution create?

Ethics Filters

The ethical component of the decision making process takes the form of a set of “filters.” Their purpose is to surface the ethics considerations and implications of the decision at hand. When decisions are classified as being “business” decisions (rather than “ethics” issues), values can quickly be left out of consideration and ethical lapses can occur.

At key steps in the process, you should stop and work through these filters, ensuring that the ethics issues imbedded in the decision are given consideration.

We group the considerations into the mnemonic PLUS.

- P = Policies Is it consistent with my organization’s policies, procedures and guidelines?

- L = Legal Is it acceptable under the applicable laws and regulations?

- U = Universal Does it conform to the universal principles/values my organization has adopted?

- S = Self Does it satisfy my personal definition of right, good and fair?

The PLUS filters work as an integral part of steps 1, 4 and 7 of the decision-making process. The decision maker applies the four PLUS filters to determine if the ethical component(s) of the decision are being surfaced/addressed/satisfied.

- Does the existing situation violate any of the PLUS considerations?

- Step 2: Seek out relevant assistance, guidance and support

- Step 3: Identify available alternative solutions to the problem

- Will the alternative I am considering resolve the PLUS violations?

- Will the alternative being considered create any new PLUS considerations?

- Are the ethical trade-offs acceptable?

- Step 5: Make the decision

- Step 6: Implement the decision

- Does the resultant situation resolve the earlier PLUS considerations?

- Are there any new PLUS considerations to be addressed?

The PLUS filters do not guarantee an ethically-sound decision. They merely ensure that the ethics components of the situation will be surfaced so that they might be considered.

How Organizations Can Support Ethical Decision-Making Organizations empower employees with the knowledge and tools they need to make ethical decisions by

- Intentionally and regularly communicating to all employees:

- Organizational policies and procedures as they apply to the common workplace ethics issues.

- Applicable laws and regulations.

- Agreed-upon set of “universal” values (i.e., Empathy, Patience, Integrity, Courage [EPIC]).

- Providing a formal mechanism (i.e., a code and a helpline, giving employees access to a definitive interpretation of the policies, laws and universal values when they need additional guidance before making a decision).

- Free Ethics & Compliance Toolkit

- Ethics and Compliance Glossary

- Definitions of Values

- Why Have a Code of Conduct?

- Code Construction and Content

- Common Code Provisions

- Ten Style Tips for Writing an Effective Code of Conduct

- Five Keys to Reducing Ethics and Compliance Risk

- Business Ethics & Compliance Timeline

6 Step Process For Ethical Decision Making: A Guide with Examples

What is ethical decision making, why do we need to make ethical decisions, 6 steps of ethical decision making, 3 ethical decision making examples in the workplace, 5 approaches of ethical decision making.

Other Related Blogs

- Understanding Motivation Of Training With 6 Effective Strategies And Benefits

- Develop Your Presentation Skills To Become An Effective Manager

- Bridging the Digital Skills Gap: 7 effective ways for managers

- Mastering the Top 30 Behavioral Questions in Interviews

- How can managers use recognition of employees as an effective motivation tool?

- Are You Setting Unrealistic Goals At Work? 5 Tips To Avoid Them

- 5 Steps of Developing an Effective Training Evaluation Program: With Best Practices

- Top 8 Challenges of Diversity in the Workplace in 2023

- How a Multicultural Workplace Boosts Your Bottom Line and Work Culture

- The Dangers Of Misinformation In The Workplace: How Managers Can Address It?

Example of Ethical Decision Making for a Manager Based on the Steps outlined above:

1. utilitarianism: maximizing happiness .

Imagine your company is deciding whether to adopt a new cost-cutting strategy that could lead to layoffs. A utilitarian approach would involve weighing the potential benefits of preserving the company’s financial health against the negative impact on employees’ livelihoods.

2. Deontology: Upholding Moral Rules

As a manager, if you discover an employee has made a mistake that could harm the team’s project, a deontological perspective would mean addressing the issue transparently and finding a solution, even if it might initially cause discomfort.

3. Virtue Ethics: Building Good Character

A leader who consistently demonstrates empathy and actively listens to their team members helps build a virtuous workplace environment that values open communication and mutual respect.

4. Justice: Fairness and Equity

During promotions, a just manager considers employees’ skills and contributions rather than favoritism, ensuring that deserving individuals are recognized and rewarded.

5. Rights-Based Ethics: Protecting Individual Rights

If implementing a new monitoring system, a rights-based leader would ensure that employees’ privacy is respected by implementing transparent policies and safeguards.

Is your team confident in your decision-making skills?

Discover insights with the free decision-making assessment for managers

Evidence Based Decision Making: 4 Proven Hacks For Managers

6 best books on decision making for managers, best decision coaches to guide you toward great choices, top 10 games for negotiation skills to make you a better leader.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Behav Anal Pract

- v.13(4); 2020 Dec

Promoting Ethical Discussions and Decision Making in a Human Service Agency

Linda a. leblanc.

1 LeBlanc Behavioral Consulting, Golden, CO USA

Olivia M. Onofrio

2 Trumpet Behavioral Health, 390 Union Blvd., Suite #300, Lakewood, CO 80228 USA

Amber L. Valentino

Joshua d. sleeper.

This article describes the development of a system, the Ethics Network, designed to promote discussion of ethical issues in a human services organization. The system includes several core components, including people (e.g., leaders, ambassadors), tools (e.g., hotline, training modules), and resources (e.g., monthly talking points). Data from 6 years of hotline submissions were analyzed to identify the most common concerns, and the data were compared to the pattern of violation notices submitted to the Behavior Analyst Certification Board. Recommendations are provided for creating similar systems in other organizations.

Behavior analysts are held accountable to a code of ethical and professional conduct called the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB®) Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts ( 2014 ), hereafter referred to as the Code. The 10 different sections of the Code cover topics related to responsibility to clients, responsibility to the field, supervision, and research, among others. This Code guides professional ethics and professional behavior in the practice of behavior analysis, as opposed to personal or everyday behavior (Bailey & Burch, 2016 ). The Code was developed to assure that the socially important work that behavior analysts do for our clients (e.g., “finding humane and effective solutions, implementing programs that work) occurs while protecting clients’ rights at all times” (Bailey & Burch, 2016 , p. 30).

Although the Code is relatively straightforward, the applied context in which one might operate according to the Code is much less straightforward. Behavior analysts are likely to be faced with complex ethical issues regularly, given that they often work with vulnerable and at-risk populations (Brodhead & Higbee, 2012 ). These issues become more prominent as the profession continues to grow at a very rapid pace (Rosenberg & Schwartz, 2019 ). Although the Code and published decision-making models exist to guide actions (Bailey & Burch, 2016 ; Rosenberg & Schwartz, 2019 ), there is little data from applied behavior analysis (ABA) human service organizations to suggest which ethical conundrums are most likely to occur. The general suspicion is that ethical issues may be common enough in ABA organizations to warrant infrastructure for ethical guidance and oversight (Brodhead & Higbee, 2012 ).

The BACB ( 2018 ) summarized submitted notices of alleged violations against certificants for the years 2016–2017 and indicated that codes 5.0 (supervision) and 10.0 (failure to report to the Board) had the highest number of submitted violations, whereas code 1.0 represented the third highest category. Subcodes from code 2.0 were in the fifth and eighth most commonly submitted categories. In a recent update, Codes 1.0 and 7.0 became the most frequently substantiated violations, with subcodes related to integrity, multiple relationships, and ethical actions frequently cited. Code 10.0 (failure to report to the Board) moved to third place, whereas Code 5.0 (supervision) moved to fourth place. However, these data may represent underreporting and likely do not capture the daily ethical situations that many Registered Behavior Technicians (RBTs), Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analysts, and Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs) contact that are concerning but might not warrant a report to the certifying body. Many ethical situations can likely be resolved directly through conversation (see Code 7.02c; BACB, 2014 ), which is in fact the recommended practice for addressing many ethical issues (Bailey & Burch, 2016 ).

The Trumpet Behavioral Health Ethics Network (hereafter, the Ethics Network) was founded in 2012 by the executive leadership team of a midsize human services agency. The goal was to create a comprehensive ethics network to support team members in being proactive in facilitating open discussion of professional and ethical issues, establishing the highest standards of professional conduct, handling ethical dilemmas swiftly as they arose, and building capacity for ethical conduct at all levels of the organization. The purpose of this article is to describe the Ethics Network for others who might want to replicate the development of the system. In addition, we present data from the first 6 years of the existence of the network to provide a sample of the issues arising in the practice of behavior analysis as a potential guide for other organizations that are developing supports for ethical behavior in human service agencies. Finally, we provide strategies and recommendations for leaders in ABA organizations who might need to modify components of our system to suit the needs of their organizations. This model demonstration represents one option that providers might use as a guide to establish resources for addressing ethics throughout their organization.

The Ethics Team

The Ethics Network team included three groups: (a) the leadership team, (b) the ethics team members, and (c) the clinical and administrative teams throughout the organization. That is, every individual in the organization was considered a member of the Ethics Network, but the leadership team and the ethics team members were most heavily involved in developing and distributing resources and supports (see the section on data-informed resource development). Figure Figure1 1 depicts the relation between the positions.

Graphic depicting the individuals involved in the Ethics Network

Leadership Team

The highest level of decision making and leadership in the organization (i.e., the executive team) is represented by the director of the Ethics Network. In the 7 years of the Ethics Network’s existence, three people have held the director role, including the first and third authors. They acted as a resource, reviewed data, fueled ideas for resource development, helped facilitate meetings, and received all ethics hotline submissions to determine how, when, and who should respond. The chair and the assistant chair positions were appointed by the executive team and were generally selected from the existing or prior ethics team members. These positions are similar to the ethics coordinator position described by Brodhead and Higbee ( 2012 ). A person was appointed to the role of assistant chair for 1 year and then proceeded into the position of chair for a second year (i.e., the assistant chair became the next chair, and a new assistant chair was appointed to support). These two positions were considered leadership and leadership-training positions, and each person in the position received a small stipend for their work at the end of the year and was allotted additional travel support for conferences and professional development activities in ethics.

Ethics Team Members

The ethics team members were volunteers who chose to participate in the regularly occurring meetings and to assist in the development of resources and training materials. These team members could be in almost any clinical or administrative role in the organization, but most often they were in the role of BCBA clinician or were aspiring to that role and actively accruing fieldwork experience hours in preparation for certification. These volunteer positions had no specified length of term, and team members served as long as they had sufficient capacity and interest or until they were appointed to the assistant chair position. Most team members rotated on and off the team within approximately 12–18 months. The Ethics Network leadership team and volunteer team members met approximately one to two times per month for an hour to plan resources and discuss ethical issues and the Code.

The Clinical and Administrative Teams

The clinical and administrative teams were generally the recipients of the efforts of the leadership team and volunteer team. At least annually, the leadership of the organization (i.e., all executive team members, all operational leaders) and the administrative team participated in a discussion about an ethics topic with general administrative applicability (see additional information in the following sections). For example, one discussion focused on the portions of the Code pertinent to human resources and appropriate professional interactions in the workplace. Another discussion focused on ethics issues related to marketing and public statements (e.g., nonsolicitation of testimonials, importance of evidence-based practices). In addition, the clinical teams at all levels (i.e., RBT to BCBA–Doctoral level) participated in one to three additional ethics trainings and discussions each year (see additional information that follows).

The Training Efforts

Establishing infrastructure and initial training.

Some of the first goals of the Ethics Network were to establish a foundation for conceptualizing and responding to ethics scenarios using a structured problem-solving approach. The emphasis in this initial training and infrastructure was to teach an overarching problem-solving strategy that was broadly applicable to many different situations, including ethical dilemmas and clinical decision making. To accomplish this objective, two resources were created and incorporated into training materials. The first resource was a multistep, structured problem-solving model commonly used with a broad array of individuals, from children with behavior problems, to executives in multinational corporations, to tackle problems as diverse as aggression and social skills problems to cultural sensitivity (Arya, Margaryan, & Collis, 2003 ; LeBlanc, Sellers, & Alai, 2020 ; Smith, Lochman, & Daunic, 2005 ). Different versions of structured problem-solving models include four, five, six, or seven steps, but all focus on the same basic repertoire (Glago, Mastropieri, & Scruggs, 2009 ; LeBlanc et al., 2020 ). We adopted a six-step version of this widely disseminated problem-solving model for all aspects of clinical problem solving, including problem solving for ethical dilemmas. The six steps were (a) recognize the problem, (b) define the problem, (c) generate potential solutions, (d) evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of potential solutions, (e) implement a solution, and (f) evaluate the effects of the solution. Throughout the organization, people were taught to analyze and respond to ethical scenarios based on these six steps as part of their initial (i.e., within the first 2 weeks of hire) training.

The second resource was a conceptualization and depiction of four overarching concepts (selected by the first author) that serve as foundations for ethical and professional behavior in many disciplines, including behavior analysis (Bailey & Burch, 2016 ; Smith, 2005 ; Zur, 2007 ). These four concepts should be adhered to in all professional situations, and failure to do so creates the risk of unethical behavior. Thus, the individual components of the Code and the responses to ethical situations (i.e., the solutions described previously) should all be relevant to one or more of these concepts: do no harm, boundaries, confidentiality, and professionalism. These concepts are similar to the reasons described as underpinning the need for the Code (e.g., humane action, protection of client rights). The graphic used in the initial (i.e., within the first 2 weeks of hire) training materials depicted each concept as a pillar of responsible professional behavior.

Discussion about ethics began early in a staff member’s tenure with the organization, and training was integrated at all levels. As part of their initial training, every employee of the organization completed an online instructional design module that covered various aspects of the Code, the concepts of the pillars of professionalism, and the model for ethical problem solving and decision making. Specific information was included for new therapists and new BCBAs. One version of the module was tailored for the administrative team by focusing on aspects of the Code and ethical problem scenarios that were more likely to be encountered in administrative tasks. Another version of the module focused on aspects of the Code and ethical scenarios that were more likely to be encountered in the delivery of clinical services.

Culture, Contingencies, and Continuous Discussion

The goal of training and ongoing discussion was to create effective and ethical decision makers at all levels of the organization and to facilitate a culture of ethical decision making by identifying and providing contingencies for ethical behavior. In addition, the ethics team regularly invited new volunteer team members from all levels of the organization (e.g., RBTs, aspiring certificants, BCBAs, administrative support professionals). All team members assisted in the development and delivery of trainings and communication resources for the organization and received public acknowledgment as ethics leaders and Ethics Network ambassadors.

After initial training in ethics, there were frequent opportunities for clinical teams to engage in discussion about ethics. The most commonly employed strategies involved the distribution of written material and live dynamic trainings and discussions. The two most frequently used written strategies were monthly talking points and e-mailed information (i.e., ethics “fun facts”). See Table Table1 1 for example topics for each strategy. The monthly talking points were distributed to clinical directors throughout the organization to facilitate discussion about ethics in monthly clinical team meetings. These documents provided a written overview of a common ethical issue (e.g., dual relationships), a detailed review of the relevant codes, and strategies for avoiding or resolving the ethical issue. In addition, the documents often provided scenarios and example scripted responses that could be used in role-plays with team members to help them practice responding to the situation. The ethics fun facts were e-mails distributed organization-wide (i.e., to both administrative and clinical team members of all skill levels). These e-mails were designed to be brief and eye-catching (e.g., infographics, videos) and focused on a single ethics-related topic as a reminder (e.g., the holidays are approaching and we do not accept gifts) or announcements (e.g., there are new ethics codes for RBTs).

Sample Resources Created by the Members of the Ethics Network

The most commonly employed versions of live, dynamic discussions were quarterly clinical team discussions and journal club activities conducted as webinars. See Table Table1 1 for examples of topics. The quarterly clinical team discussions were based on presentations and discussions about advanced ethics and leadership topics (e.g., ethical issues arising when families are separating or divorcing, the importance of operating within your scope of competence). The quarterly discussions were typically created and led by members of the ethics team and were usually created in response to ethical questions that had arisen throughout the year or professional development events from conferences. The journal clubs typically focused on published articles that focused on some aspect of ethical behavior, and the journal clubs were co-led by a member of the ethics team and the author of the article. Finally, each year the ethics leaders conducted a training and discussion with the administrative team about portions of the Code that were particularly pertinent to administrative support activities (e.g., nonsolicitation of testimonials).

The Ethics Hotline

To provide team members with immediate support, an internal ethics hotline was created. The hotline was located on the organization’s intranet and was accessible by any team member. Submissions were anonymous to everyone except the ethics director, who received the submissions via e-mail. Once received, the director removed identifying information. In cases of an emergency, the director contacted the team member within 12 h. In nonemergencies, the director de-identified the submission and reviewed the submission with the chair and assistant chair. These leaders facilitated a discussion about the submission at the next Ethics Network meeting with the volunteers, and one to two team members volunteered to craft a response within 1 week.

The ethics submission form was specifically designed to follow the problem-solving and decision-making steps outlined in the training materials. For example, the form prompts team members to (a) describe their concern (i.e., detect the problem), (b) consider which BACB Code item is relevant to their scenario (i.e., define the problem), (c) nominate possible solutions to their dilemma, and (d) list any pros and cons of the possible solutions. The BACB Code numbers were listed in a drop-down selection menu. See the Appendix .

Data-Informed Resource Development

The ethics leaders and ethics team met regularly (e.g., every 2–4 weeks) to develop and execute the annual resource development and training plan. Sometimes new topics were identified, and sometimes resources that had previously been distributed were redistributed (e.g., information on the ethics of gift giving and receipt from clients was distributed in mid-November each year). The topics were selected based on a review of the recent ethics hotline submissions and direct conversations with individuals in the organization who wanted to offer input (e.g., the managing director suggested a topic on peer interactions in the workplace). Once topics had been suggested, the leaders identified the mechanism that seemed best suited to the topics (e.g., fun fact, monthly talking point, all-staff training). The leaders then recruited members of the ethics team to assist with topics that interested them the most. See Table Table1 1 for a sample of topics covered in each distribution mechanism.

Coding Procedures

We downloaded all ethics hotline submissions submitted by staff members from the conception of the Ethics Network at the end of 2012 through 2019. A total of 137 submissions were reviewed. The submission data were downloaded in a Microsoft Excel® document that included the information completed by each staff member submitter. The fields the submitter completed are included in the Appendix . The names of the submitters were removed before the document was reviewed by the second author.

Data Coding and Analysis

The second author read and coded each submission for the year and month of submission, whether the situation was described as urgent or nonurgent, the position and background of the submitter, and the BACB codes and subcodes identified by the submitter. Next, the coder identified any additional codes or subcodes that were relevant based on the written description of the ethical concern.

The frequency of submissions was calculated for each full year from 2012 to 2019. The percentage of submissions described as urgent by the submitter was calculated by adding the number of submissions marked urgent to the number marked not urgent and dividing by the total number of submissions. The frequency of the positions of submitters was calculated for the following categories and subcategories when applicable: administrative and support services, clinical leadership (i.e., regional director, clinical director), senior clinician, clinician (i.e., clinician, associate clinician), direct care provider (i.e., senior therapist, therapist), and unidentified. The frequency of identification was noted for each of the 10 BACB codes as identified by (a) the submitter and (b) the researchers. Next, the researcher identified the total number of codes and subcodes identified for each submission and calculated an average by dividing the total number of codes and subcodes identified for all submissions by the total number of submissions.

Interobserver Agreement (IOA)

A second independent coder (i.e., the third author) scored 25% of the entries ( n = 35) for the pertinent ethical codes for each submission. The second coder downloaded the same spreadsheet along with the BACB Code and scored every third entry to ensure that the entire time span was sampled. She read each selected submission and identified the relevant codes. The primary and secondary coders’ responses were then compared. For an agreement to be scored, the coders had to agree on all relevant codes for that entry (i.e., the submission generated perfect agreement on all codes identified by the reviewers). The overall agreement was calculated by summing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100 to obtain a percentage. Of the 35 submissions scored for IOA, there were 30 agreements and 5 disagreements, resulting in an overall IOA score of 86%. The most common type of disagreement was for one coder to identify an additional code that the other had not. A second coder also scored the position of the submitter for each submitter (i.e., IOA scored for 100% of submissions). For these measures, IOA was calculated by dividing the smaller number by the larger number and converting to a percentage. The resulting IOA for the submitters’ positions was 100%.

The frequency of submissions for each full year from 2012 to 2019 is depicted in Fig. Fig.2. 2 . The partial year of 2012 (November and December) is not graphed but had only a single submission. There was an increasing trend for the first full 3 years, with submissions stabilizing between the years 2015 and 2019 ( M = 25.25 for these last four data points). Across all years, the percentage of submissions described as urgent by the submitter was 12%, whereas 88% were described as nonurgent, perhaps suggesting that submitters were using the hotline proactively to initiate discussions about situations that could arise or could become urgent if not addressed.

Frequency of ethics hotline submissions per year

The frequency of the position of submitters is depicted in Fig. Fig.3. 3 . The category with the lowest number of submissions was “unidentified,” followed by “direct care providers.” The category with the highest number of submissions was “clinician,” which included both BCBAs and those pursuing their credential and serving as a case coordinator under the supervision of a clinical leader. The number of employees of the organization ranged from approximately 600 to 900 during these years, with approximately 75%–80% of employees holding direct service provider positions. Thus, the number of submissions per employee is very low, and clinicians and leadership positions are far overrepresented in reporting compared to direct care providers.

When two tiers exist for a position (i.e., clinical leadership, clinician, direct care provider), the more junior tier is represented by the filled bar segment, and the more senior tier is represented by the hashed bar segment

The mean number of relevant BACB codes per submission (i.e., identified by the submitter) was 1.0, with a range of 0 to 4. The majority of submissions with no BACB codes indicated “unsure” as the response. In contrast, the mean number of BACB codes identified from the submissions by the reviewing researcher (i.e., identified by an expert) was higher, at 1.43, with a range of 0 to 5 codes per submission. The distribution of the submissions across the Code areas is depicted in Fig. Fig.4, 4 , with the original submitter data represented as a filled bar and the expert reviewer data as a hashed bar. The most frequently identified code area by both submitters and the reviewer was code 2. The second most frequently endorsed area by submitters was “unsure/not applicable,” followed closely by code 1. In contrast, the reviewing researcher identified more items for code 1 and fewer items with no applicable or discernable code. One potential benefit of an ethics network is that people who are unsure about whether a specific code is applicable can seek assistance from a colleague who is more likely to recognize the relevant codes for a situation. A second potential benefit of an ethics network is that behavior analysts who are early in their careers may learn to become better at identifying additional relevant Code violations through their interactions with the ethics hotline team. The reviewing researcher also scored subcodes for the most frequently identified areas (codes 1 and 2) and found that subcodes 1.06 (multiple relationships and conflicts of interest), 2.05 (rights and prerogatives of clients), and 2.06 (maintaining confidentiality). Full data on subcodes for codes 1.0 and 2.0 are available upon request were the most frequently identified.

Number of times codes were identified by the hotline submitter and expert coder

A direct comparison with the BACB’s reported data is not possible due to the format of the reporting of the BACB data. That is, the BACB reports combine multiple code sections together by category in their reporting of cases for 2018, whereas we report each code area separately. However, some general observations are possible. The Trumpet hotline data indicate that Codes 1.0 and 2.0 are the most commonly submitted. Similarly, the 2018 data from the BACB reveal that several Code 1.0 elements are represented in notices of alleged violations that resulted in substantiated violations and disciplinary action. Code 2.0 elements, however, are only the fifth, seventh, eighth, and ninth most common groupings in the BACB data, with few substantiated violations per grouping. Finally, the BACB reports (2016–2017; BACB, 2018 ) both indicate a high proportion of violations related to failure to comply with BACB rules or reporting requirements (i.e., code 10), whereas none of the Trumpet hotline submissions were related to code 10.

Brodhead and Higbee ( 2012 ) provided recommendations for creating a structure for supporting ethical guidance and training in human service organizations. This article illustrates a system of active supports developed in a large human services agency with the express purpose of fostering open discussion about ethics and systematic problem solving in ethical dilemmas. Many of the components of the system (i.e., the Ethics Network) are similar to the ones described by Brodhead and Higbee ( 2012 ), including a team of directors and a focus on training and supervision. Brodhead, Quigley, and Cox ( 2018 ) suggest that discerning potential employees should evaluate organizations by examining the “extent to which the organization expects employees to engage in ethical conduct, and actively supports those expectations” (p. 165). One way to actively support those expectations for ethical conduct is to create a system such as the Ethics Network described here.

There are several behavioral explanations for why individuals may behave unethically or fail to report others who behavior unethically. The Ethics Network was designed to address each of these potential behavioral explanations. First, reporting and discussing unethical behavior can be unpleasant, which may lead to avoidance of reports and discussions unless systems are developed that facilitate continuous discussion. Positive reinforcement contingencies for asking for help or offering help were built into the ethics system (e.g., immediate response and support from a leader, status and reinforcement for being involved in the network). Having discussions occur at fixed times rather than in response to crises was designed to eliminate any respondent or operant conditioning process that might occur with contingent (i.e., crisis-triggered) discussions of ethical issues. Second, individuals may have a skill deficit in identifying ethical dilemmas. Without specific training and support for individuals, unethical behavior may occur because of ignorance of the Code and the overarching principles that underly the Code. The training components of the Ethics Network were designed to minimize skill deficits and to focus on a structured problem-solving approach used across contexts and a small number of underlying principles rather than numerical codes. Third, the response effort of obtaining support and resources for ethical decision making may lead to reduced reporting and assistance seeking. Resources that are easy to access and use, such as the hotline, the monthly talking points, and the fun facts distributed via e-mail, were designed to reduce the response effort for ethical support. Each of these possibilities likely exists in the lives of behavior analysts faced with making ethical decisions each day and needs to be considered in the context of creating a culture that promotes ethical decision making.

The analysis of the Ethics Network hotline submissions offers a few points of insight. First, there was an ascending slope in the frequency of submissions throughout the first years of the system. This pattern may suggest that it takes time for the competing positive reinforcement contingencies to overcome the inherent negative reinforcement contingencies. It may also suggest that the ongoing training efforts established important prerequisite skills for submission (e.g., knowledge of the Code, sufficient exemplars to identify dilemmas). Second, the most frequently identified codes were codes 1.0 and 2.0. These areas focus on the responsible conduct of behavior analysts and their responsibility to clients, and the most common subcodes focused on dual relationships or conflicts of interest, rights of clients, and confidentiality.

Another finding worthy of note was the fact that those serving in the role of expert usually identified more codes that were relevant than the original submitter. In addition, the most common source of disagreement between the experts was when one of them identified an additional area that might be relevant. These data speak to the fact that most ethical situations have multiple potential implications and areas of concern. Difficult situations do not readily fall neatly into a single code or subcode without other issues being identified. These findings are also evident in the data reported by the BACB ( 2018 ), who found that the majority of violation submissions included multiple violations (i.e., from two to over five). Some of the topics endorsed in hotline submissions differed from the violations reported to the BACB (e.g., no code 10 submissions), but dual relationships and clients’ rights submissions were high for both sources.

Although these data offer some insights into hotline submissions over a span of several years, there was no experimental evaluation of the components of the system as necessary or sufficient to produce robust ethical decision making. The mastery of the instructional design module suggests that certain verbal repertoires were acquired, and the submissions to the ethics hotline suggest that people sought guidance and resources. However, there is no way to know how many actual ethical dilemmas were occurring across the multiyear span as a comparison and means to calculate whether an increasing or substantial percentage of dilemmas was being submitted. Future studies could experimentally evaluate the components included in this ethics network.

The purpose of this article was to provide an example for others who wish to build systems that support ethical behavior and facilitate honest and proactive discussion of difficult situations and potential solutions. In doing so, these types of systems may assist us in our endeavors to do socially important work while protecting clients’ rights at all times (Bailey & Burch, 2016 ). However, human service organizations may differ substantially in size, resources, and expertise. Trumpet Behavioral Health is a relatively large organization with resources committed to systems development, expertise, and infrastructure to support clinical standards implementation. Other organizations might lack expertise or resources and infrastructure for the multicomponent approach taken at Trumpet.

The following suggestions may assist organizations in modifying the approach to meet their needs. First, there may need to be one single leader of the ethics network in a smaller organization. It is important that the leader have influence throughout the organization so that ethical discussions occur among both clinical teams and administrative support teams. Second, organizations may need to rely on existing resources rather than create their own, as was done at Trumpet. Fortunately, many more published resources on ethics exist now than existed in 2012 when the Ethics Network was started at Trumpet. These published resources can be incorporated into a journal club option even if the other resource categories listed in Table Table1 1 are not possible. Third, now that data exist from this analysis and the BACB, an organization might target ethical discussions and resources at the most commonly reported problems. That is, a focus of discussions on dual relationships, responsibility to clients, and privacy and confidentiality would address many existing and potential ethical problems, though certainly not all of them.

Author Note

The Ethics Network was developed as part of the Clinical Standards Initiative at Trumpet Behavioral Health. The authors thank Allie Kane, Heather Loeb, Jessie Mitchell, Kirstin Powers, Sarah Kristiansen, and Michael Wright, who each served as assistant chair, chair, or director of the Ethics Network.

Information Completed by Submitters on the Ethics Hotline Submission Form

No funding was associated with the current study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflict of interest regarding this manuscript.

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Arya K, Margaryan A, Collis B. Culturally sensitive problem solving activities for multi-national corporations. TechTrends. 2003; 47 :40–49. doi: 10.1007/BF02763283. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bailey JS, Burch MR. Ethics for behavior analysts . 3. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board . Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts . Littleton, CO: Author; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board . A summary of ethics violations and code-enforcement activities: 2016–2017 . Littleton, CO: Author; 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brodhead MT, Higbee TS. Teaching and maintaining ethical behavior in a professional organization. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012; 5 (2):82–88. doi: 10.1007/BF03391827. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brodhead MT, Quigley SP, Cox DJ. How to identify ethical practices in organizations prior to employment. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018; 11 (2):165–173. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-0235-y. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glago K, Mastropieri MA, Scruggs TE. Improving problem solving of elementary students with mild disabilities. Remedial and Special Education. 2009; 30 (6):372–380. doi: 10.1177/0741932508324394. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- LeBlanc LA, Sellers TP, Alai S. Building and sustaining meaningful and effective relationships as a supervisor and mentor . Cornwall on Hudson, NY: Sloan Publishing; 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- O'Leary, P. N., Miller, M. M., Olive, M. L., & Kelly, A. N. (2015). Blurred lines: ethical implications of social media for behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 10 (1), 45–51. 10.1007/s40617-014-0033-0 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Rosenberg NE, Schwartz IS. Guidance or compliance: What makes an ethical behavior analyst? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019; 12 (2):473–482. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00287-5. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith CM. Origin and uses of primum non nocere—above all, do no harm! Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2005; 45 (4):371–377. doi: 10.1177/0091270004273680. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith SW, Lochman JE, Daunic AP. Managing aggression using cognitive-behavioral interventions: State of the practice and future. Behavioral Disorders. 2005; 30 (3):227–240. doi: 10.1177/019874290503000307. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zur O. Boundaries in psychotherapy: Ethical and clinical explorations . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

A Framework for Ethical Decision Making

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Ethics Resources

This document is designed as an introduction to thinking ethically. Read more about what the framework can (and cannot) do .

We all have an image of our better selves—of how we are when we act ethically or are “at our best.” We probably also have an image of what an ethical community, an ethical business, an ethical government, or an ethical society should be. Ethics really has to do with all these levels—acting ethically as individuals, creating ethical organizations and governments, and making our society as a whole more ethical in the way it treats everyone.

What is Ethics?

Ethics refers to standards and practices that tell us how human beings ought to act in the many situations in which they find themselves—as friends, parents, children, citizens, businesspeople, professionals, and so on. Ethics is also concerned with our character. It requires knowledge, skills, and habits.

It is helpful to identify what ethics is NOT:

- Ethics is not the same as feelings . Feelings do provide important information for our ethical choices. However, while some people have highly developed habits that make them feel bad when they do something wrong, others feel good even though they are doing something wrong. And, often, our feelings will tell us that it is uncomfortable to do the right thing if it is difficult.

- Ethics is not the same as religion . Many people are not religious but act ethically, and some religious people act unethically. Religious traditions can, however, develop and advocate for high ethical standards, such as the Golden Rule.

- Ethics is not the same thing as following the law. A good system of law does incorporate many ethical standards, but law can deviate from what is ethical. Law can become ethically corrupt—a function of power alone and designed to serve the interests of narrow groups. Law may also have a difficult time designing or enforcing standards in some important areas and may be slow to address new problems.

- Ethics is not the same as following culturally accepted norms . Cultures can include both ethical and unethical customs, expectations, and behaviors. While assessing norms, it is important to recognize how one’s ethical views can be limited by one’s own cultural perspective or background, alongside being culturally sensitive to others.

- Ethics is not science . Social and natural science can provide important data to help us make better and more informed ethical choices. But science alone does not tell us what we ought to do. Some things may be scientifically or technologically possible and yet unethical to develop and deploy.

Six Ethical Lenses

If our ethical decision-making is not solely based on feelings, religion, law, accepted social practice, or science, then on what basis can we decide between right and wrong, good and bad? Many philosophers, ethicists, and theologians have helped us answer this critical question. They have suggested a variety of different lenses that help us perceive ethical dimensions. Here are six of them:

The Rights Lens

Some suggest that the ethical action is the one that best protects and respects the moral rights of those affected. This approach starts from the belief that humans have a dignity based on their human nature per se or on their ability to choose freely what they do with their lives. On the basis of such dignity, they have a right to be treated as ends in themselves and not merely as means to other ends. The list of moral rights—including the rights to make one's own choices about what kind of life to lead, to be told the truth, not to be injured, to a degree of privacy, and so on—is widely debated; some argue that non-humans have rights, too. Rights are also often understood as implying duties—in particular, the duty to respect others' rights and dignity.

( For further elaboration on the rights lens, please see our essay, “Rights.” )

The Justice Lens

Justice is the idea that each person should be given their due, and what people are due is often interpreted as fair or equal treatment. Equal treatment implies that people should be treated as equals according to some defensible standard such as merit or need, but not necessarily that everyone should be treated in the exact same way in every respect. There are different types of justice that address what people are due in various contexts. These include social justice (structuring the basic institutions of society), distributive justice (distributing benefits and burdens), corrective justice (repairing past injustices), retributive justice (determining how to appropriately punish wrongdoers), and restorative or transformational justice (restoring relationships or transforming social structures as an alternative to criminal punishment).

( For further elaboration on the justice lens, please see our essay, “Justice and Fairness.” )

The Utilitarian Lens

Some ethicists begin by asking, “How will this action impact everyone affected?”—emphasizing the consequences of our actions. Utilitarianism, a results-based approach, says that the ethical action is the one that produces the greatest balance of good over harm for as many stakeholders as possible. It requires an accurate determination of the likelihood of a particular result and its impact. For example, the ethical corporate action, then, is the one that produces the greatest good and does the least harm for all who are affected—customers, employees, shareholders, the community, and the environment. Cost/benefit analysis is another consequentialist approach.

( For further elaboration on the utilitarian lens, please see our essay, “Calculating Consequences.” )

The Common Good Lens

According to the common good approach, life in community is a good in itself and our actions should contribute to that life. This approach suggests that the interlocking relationships of society are the basis of ethical reasoning and that respect and compassion for all others—especially the vulnerable—are requirements of such reasoning. This approach also calls attention to the common conditions that are important to the welfare of everyone—such as clean air and water, a system of laws, effective police and fire departments, health care, a public educational system, or even public recreational areas. Unlike the utilitarian lens, which sums up and aggregates goods for every individual, the common good lens highlights mutual concern for the shared interests of all members of a community.

( For further elaboration on the common good lens, please see our essay, “The Common Good.” )

The Virtue Lens

A very ancient approach to ethics argues that ethical actions ought to be consistent with certain ideal virtues that provide for the full development of our humanity. These virtues are dispositions and habits that enable us to act according to the highest potential of our character and on behalf of values like truth and beauty. Honesty, courage, compassion, generosity, tolerance, love, fidelity, integrity, fairness, self-control, and prudence are all examples of virtues. Virtue ethics asks of any action, “What kind of person will I become if I do this?” or “Is this action consistent with my acting at my best?”

( For further elaboration on the virtue lens, please see our essay, “Ethics and Virtue.” )

The Care Ethics Lens

Care ethics is rooted in relationships and in the need to listen and respond to individuals in their specific circumstances, rather than merely following rules or calculating utility. It privileges the flourishing of embodied individuals in their relationships and values interdependence, not just independence. It relies on empathy to gain a deep appreciation of the interest, feelings, and viewpoints of each stakeholder, employing care, kindness, compassion, generosity, and a concern for others to resolve ethical conflicts. Care ethics holds that options for resolution must account for the relationships, concerns, and feelings of all stakeholders. Focusing on connecting intimate interpersonal duties to societal duties, an ethics of care might counsel, for example, a more holistic approach to public health policy that considers food security, transportation access, fair wages, housing support, and environmental protection alongside physical health.

( For further elaboration on the care ethics lens, please see our essay, “Care Ethics.” )

Using the Lenses

Each of the lenses introduced above helps us determine what standards of behavior and character traits can be considered right and good. There are still problems to be solved, however.

The first problem is that we may not agree on the content of some of these specific lenses. For example, we may not all agree on the same set of human and civil rights. We may not agree on what constitutes the common good. We may not even agree on what is a good and what is a harm.

The second problem is that the different lenses may lead to different answers to the question “What is ethical?” Nonetheless, each one gives us important insights in the process of deciding what is ethical in a particular circumstance.

Making Decisions

Making good ethical decisions requires a trained sensitivity to ethical issues and a practiced method for exploring the ethical aspects of a decision and weighing the considerations that should impact our choice of a course of action. Having a method for ethical decision-making is essential. When practiced regularly, the method becomes so familiar that we work through it automatically without consulting the specific steps.

The more novel and difficult the ethical choice we face, the more we need to rely on discussion and dialogue with others about the dilemma. Only by careful exploration of the problem, aided by the insights and different perspectives of others, can we make good ethical choices in such situations.

The following framework for ethical decision-making is intended to serve as a practical tool for exploring ethical dilemmas and identifying ethical courses of action.

Identify the Ethical Issues

- Could this decision or situation be damaging to someone or to some group, or unevenly beneficial to people? Does this decision involve a choice between a good and bad alternative, or perhaps between two “goods” or between two “bads”?

- Is this issue about more than solely what is legal or what is most efficient? If so, how?

Get the Facts

- What are the relevant facts of the case? What facts are not known? Can I learn more about the situation? Do I know enough to make a decision?

- What individuals and groups have an important stake in the outcome? Are the concerns of some of those individuals or groups more important? Why?

- What are the options for acting? Have all the relevant persons and groups been consulted? Have I identified creative options?

Evaluate Alternative Actions

- Evaluate the options by asking the following questions:

- Which option best respects the rights of all who have a stake? (The Rights Lens)

- Which option treats people fairly, giving them each what they are due? (The Justice Lens)

- Which option will produce the most good and do the least harm for as many stakeholders as possible? (The Utilitarian Lens)

- Which option best serves the community as a whole, not just some members? (The Common Good Lens)

- Which option leads me to act as the sort of person I want to be? (The Virtue Lens)

- Which option appropriately takes into account the relationships, concerns, and feelings of all stakeholders? (The Care Ethics Lens)

Choose an Option for Action and Test It

- After an evaluation using all of these lenses, which option best addresses the situation?

- If I told someone I respect (or a public audience) which option I have chosen, what would they say?

- How can my decision be implemented with the greatest care and attention to the concerns of all stakeholders?

Implement Your Decision and Reflect on the Outcome

- How did my decision turn out, and what have I learned from this specific situation? What (if any) follow-up actions should I take?

This framework for thinking ethically is the product of dialogue and debate at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Primary contributors include Manuel Velasquez, Dennis Moberg, Michael J. Meyer, Thomas Shanks, Margaret R. McLean, David DeCosse, Claire André, Kirk O. Hanson, Irina Raicu, and Jonathan Kwan. It was last revised on November 5, 2021.

- Creating Environments Conducive to Social Interaction

Thinking Ethically: A Framework for Moral Decision Making

- Developing a Positive Climate with Trust and Respect

- Developing Self-Esteem, Confidence, Resiliency, and Mindset

- Developing Ability to Consider Different Perspectives

- Developing Tools and Techniques Useful in Social Problem-Solving

- Leadership Problem-Solving Model

- A Problem-Solving Model for Improving Student Achievement

- Six-Step Problem-Solving Model

- Hurson’s Productive Thinking Model: Solving Problems Creatively

- The Power of Storytelling and Play

- Creative Documentation & Assessment

- Materials for Use in Creating “Third Party” Solution Scenarios

- Resources for Connecting Schools to Communities

- Resources for Enabling Students

These 5 approaches and their history can be found at:

Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

http://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/iie/v7n1/thinking.html

An integrated ethical decision-making model for nurses

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Nursing, Kyungwon University, San 65 Bokjeong-Dong, Gyeonggi-Do, Korea. [email protected]

- PMID: 22156941

- DOI: 10.1177/0969733011413491

The study reviewed 20 currently-available structured ethical decision-making models and developed an integrated model consisting of six steps with useful questions and tools that help better performance each step: (1) the identification of an ethical problem; (2) the collection of additional information to identify the problem and develop solutions; (3) the development of alternatives for analysis and comparison; (4) the selection of the best alternatives and justification; (5) the development of diverse, practical ways to implement ethical decisions and actions; and (6) the evaluation of effects and development of strategies to prevent a similar occurrence. From a pilot-test of the model, nursing students reported positive experiences, including being satisfied with having access to a comprehensive review process of the ethical aspects of decision making and becoming more confident in their decisions. There is a need for the model to be further tested and refined in both the educational and practical environments.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Attitude of Health Personnel

- Decision Support Techniques*

- Ethics, Nursing*

- Models, Nursing*

- Nursing Evaluation Research

- Pilot Projects

- Students, Nursing / psychology

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)