An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Integrating Mediators and Moderators in Research Design

David p. mackinnon.

1 Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

The purpose of this article is to describe mediating variables and moderating variables and provide reasons for integrating them in outcome studies. Separate sections describe examples of moderating and mediating variables and the simplest statistical model for investigating each variable. The strengths and limitations of incorporating mediating and moderating variables in a research study are discussed as well as approaches to routinely including these variables in outcome research. The routine inclusion of mediating and moderating variables holds the promise of increasing the amount of information from outcome studies by generating practical information about interventions as well as testing theory. The primary focus is on mediating and moderating variables for intervention research but many issues apply to nonintervention research as well.

It is sufficiently obvious that both analysis and synthesis is necessary in classification and that both splitting and lumping have a place, or, to the extent that the terms involve antithesis, that neither one is correct. It is desirable that all distinguishable groups should be distinguished (although it is not necessary that all enter into formal classification and receive names). It is also desirable that they should all be gathered into larger units of increasing magnitude with grades, each of which has practical value and which are numerous enough to suggest degrees of affinity that can be and need to be specified. ( Simpson, 1945 , p. 23)

Two common questions in intervention outcome research are “How does the intervention work?” and “For which groups does the intervention work?” The first question is a question about mediating variables —variables that describe the process by which the intervention achieves its effects. The second question is about moderating variables —variables for which the intervention has a different effect at different values of the moderating variable. More information can be extracted from research studies if measures of mediating and moderating variables are included in the study design and data-collection plan. Furthermore, including measures of moderating and mediating variables is inexpensive, given their potential for providing information about how interventions work and for whom interventions work. Mediating and moderating variables are important for nonintervention outcome research as well as intervention research. A mediating variable is relevant whenever a researcher wants to understand the process by which two variables are related, such that one variable causes a mediating variable which then causes a dependent variable. Moderating variables are important whenever a researcher wants to assess whether two variables have the same relation across groups.

Third-Variable Effects

Mediating and moderating variables are examples of third variables. Most research focuses on the relation between two variables—an independent variable X and an outcome variable Y . Example statistics for two-variable effects are the correlation coefficient, odds ratio, and regression coefficient. With two variables, there are a limited number of possible causal relations between them: X causes Y , Y causes X , both X and Y are reciprocally related. With three variables, the number of possible relations among the variables increases substantially: X may cause the third variable Z and Z may cause Y ; Y may cause both X and Z , and the relation between X and Y may differ for each value of Z , along with others. Mediation and moderation are names given to two types of third-variable effects. If the third variable Z is intermediate in a causal sequence such that X causes Z and Z causes Y , then Z is a mediating variable; it is in a causal sequence X → Z → Y . If the relation between X and Y is different at different values of Z , then Z is a moderating variable. A primary distinction between mediating and moderating variables is that the mediating variable specifies a causal sequence in that a mediating variable transmits the causal effect of X to Y but the moderating variable does not specify a causal relation, only that the relation between X and Y differs across levels of Z . Diagrams for a mediating variable in Figure 1 and a moderating variable in Figure 2 demonstrate the difference between these two variables where the causal sequence is shown with directed arrows in Figure 1 to demonstrate a mediation relation. For moderation in Figure 2 , there is not an indirect relation of X to Y but there is an interaction XZ that corresponds to a potentially different X to Y relation at values of Z .

Single mediator model.

Single moderator model.

Another important third variable is the confounding variable that causes both X and Y such that failure to adjust for the confounding variable will confound or lead to incorrect conclusions about the relation of X to Y . A confounding variable differs from a mediating variable in that the confounding variable is not in a causal sequence but the confounding variable is related to both X and Y . A confounder differs from a moderating variable because the relation of X to Y may not differ across values of the confounding variable. Mediating and moderating variables are the focus of this article. More on these different types of third-variable effects are described elsewhere ( Greenland & Morgenstern, 2001 ; MacKinnon, 2008 ; MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000 ).

As you might expect, there are many more possible combinations of relations among four variables and as more variables are added, the number of possible relations among variables soon grows very complex. In this case with many variables, researchers typically often focus on third-variable effects such as moderating and mediating variables even in the most complex models. It is useful to remember that even though I focus on the simplest moderating and mediating model in this article, as the number of variables increases the number of possible models increases dramatically. Typically, the complexity of multivariable models is addressed with specific theoretical comparisons, specific types of variables, randomization, and specific tests based on prior research.

Mediating Variables

A single mediator model represents the addition of a third variable to an X → Y relation so that the causal sequence is modeled such that X causes the mediator, M , and M causes Y , that is, X → M → Y . Mediating variables are central to many fields because they are used to understand the process by which two variables are related. There are two overlapping ways in which mediating variables have been used in prior research: (a) mediation for design where interventions are designed to change a mediating variable and (b) mediation for explanation where mediators are selected after an effect of X to Y has been demonstrated to explain the mediating process by which X affects Y ( MacKinnon, 2008 , Chap. 2). The use of mediating variables for design is central to interventions designed to affect behavior. Intervention studies are based on theory for how the intervention is expected to change mediating variables and the change in the mediating variables is hypothesized to be what causes changes in an outcome variable. If the theory that the mediating constructs are causally related to the outcome is correct, then an intervention that changes the outcome will change the mediator. In an intervention to prevent sexually transmitted diseases, the intervention may be designed to change mediators of abstinence and condom use. In drug prevention research, mediating variables such as social norms, social competence skills, and expectations about drug use are targeted in order to change drug use. Many researchers have stressed the importance of assessing mediation in intervention research ( Baranowski, Anderson, & Carmack, 1998 ; Fraser & Galinsky, 2010 ; Judd & Kenny, 1981a , 1981b ; Kazdin, 2009 ; Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002 ; MacKinnon, 1994 ; Weiss, 1997 ).

The other major application of mediating variables is after an effect is observed and researchers investigate how this effect occurred. Mediation for explanation has a long history starting with the work of Lazarsfeld and others ( Hyman, 1955 ; Lazarsfeld, 1955 ) whereby observed relations between two variables are elaborated by considering a third variable and one explanation of why the two variables are related is because of mediation. Evaluating mediation to explain an observed effect is probably more susceptible to chance findings than evaluating mediation by design because the mediators in the mediation for design studies are selected before the study and mediators for explanation are usually selected after the study. Most programs of research employ both mediation by design and mediation for explanation approaches ( MacKinnon, 2008 , Chap. 2).

Reasons for including mediating variables in a research study

There are many overlapping reasons for including mediating variables in a research study. Seven reasons are listed below for the case of an intervention study as described elsewhere ( MacKinnon, 1994 , 2008 ; MacKinnon & Luecken, 2011 ).

- Manipulation check: Mediation analyses provide a check on whether the intervention produced a change in the mediating variables it was designed to change (e.g., if the intervention was designed to engender an antitobacco norm, then program effects on norms should be observed). If the program did not change the mediating variable, it is unlikely to have the desired effects on the targeted outcome. Failure to significantly change the mediator may occur because the intervention was unsuccessful, the measurement of the mediating variable was inadequate, or by chance statistical fluctuations.

- Program improvement: Mediation analyses generate information to identify successful and unsuccessful intervention components. If an intervention component did not change the mediating variable, then the actions selected to change the mediating variable need improvement. For example, if no program effects on social norms are found, the intervention may need to reconsider the intervention components used to change norms. If the program increases norms but norms do not affect the outcome, the norms component of the program may be ineffective and/or unnecessary and new mediators may need to be included.

- Measurement improvement: A lack of an intervention effect on a mediator can suggest that the measures of the mediator were not reliable or valid enough to detect changes. If no program effects are found on norms, for example, it may be that the method used to measure norms is not reliable or valid.

- Possibility of delayed program effects: If the intervention does not have the desired effect on the outcome variable but does significantly affect theorized mediating variables, it is possible that effects on outcomes will emerge later after the effects of the mediating variable have accumulated over time. For example, the effects of a norm change intervention to reduce smoking onset among young children may not be evident until the children are older and have more opportunities to smoke.

- Evaluating the process of change: Mediation analysis provides information on the processes by which the intervention achieved its effects on an outcome measure. For example, it is possible to study whether the changes in mediators like norms or another mediator were responsible for intervention effects on smoking.

- Building and refining theory: One of the greatest strengths of including mediating variables is the ability to test the theories upon which intervention programs were based. Many theories are based on results of cross-sectional relations with little or no randomized experimental manipulation. Mediation analysis in the randomized design is ideal for testing theories because it improves causal inference. Competing theories for smoking onset and addiction, for example, may suggest alternative mediating variables that can be tested in an experimental design.

- Practical implications: The majority of intervention programs have limited resources to accomplish their goals. Intervention programs will cost less and provide greater benefits if the critical ingredients of interventions can be identified because critical components can be retained and ineffective components removed. Mediation analyses can help decide whether to discontinue an intervention approach or not by providing information about whether it was a failure of the intervention to change the mediator, called action theory or whether it was a failure of a significant relation of the mediator to the outcome, called conceptual theory, or both.

How to include mediating variables in a research study

There are two major aspects to adding mediating variables to a research study. First is during the planning stage where the theoretical framework of the study and testing theory is considered and often specified in a logic model. In many cases, the development of a logic model may take considerable time and resources because it forces researchers to carefully consider how the intervention components could be reasonably expected to change an outcome. In fact, the most important aspect of considering mediating variables in a research study may be that it forces researchers to think in a concrete manner about how the intervention could be expected to work both in terms of action theory for how the intervention affects the mediators and conceptual theory for which mediators are related to the outcome. The second aspect to adding mediating variables is deciding how to measure theoretical mediating variables. Typically, this requires adding measures to a questionnaire or some other measurement procedure. In many cases, there may not be existing measures of relevant mediating constructs and psychometric work must be done to develop measures of mediating variables. Furthermore, the addition of measures of mediating variables can add to the respondent burden on a questionnaire. Nevertheless, the addition of mediating variable measures may generate practical and theoretical information from a research study. It is important to measure mediating variables in both intervention and control conditions before and after the intervention to ascertain change in the measures and for statistical mediation analysis.

Mediation Regression Equations

The ideas regarding mediating variables can be translated into equations suitable for estimating mediated effects and conducting statistical tests as for the single mediator model for X, M , and Y shown in Figure 1 and defined in Equations 2 and 3 below. Equation 1 is also shown because it provides information for mediation relations and corresponds to the overall intervention effect:

Where X is the independent variable, Y is the outcome variable, and M is the mediating variable; the parameters i 1 , i 2 , and i 3 are intercepts in each equation; and e 1 , e 2 , and e 3 are residuals. In Equation 1 , the coefficient c represents the total effect, that is, the total effect that X can have on Y , the outcome variable. In Equation 2 , the parameter c’ denotes the relation between X and Y controlling for M , representing the direct effect—the effect of X on Y that is adjusted for M , the parameter b denotes the relation between M and Y adjusted for X . Finally, in Equation 3 , the coefficient a denotes the relation between X and M . Equations 2 and 3 are represented in Figure 1 , which shows how the total effect of X on Y is separated into a direct effect relating X to Y and a mediated effect by which X indirectly affects Y through M . Complete mediation is the case where the total effect is completely explained by the mediator, that is, there is no direct effect. In this case, the total effect is equal to the mediated effect (i.e., c = ab ). Partial mediation is the case where the relation between the independent and the outcome variable is not completely accounted for by the mediating variable. There are alternative estimators of the mediated effect including difference in coefficients and product of coefficients, which are based on the regression equations. More on the different approaches to mediation analysis can be found elsewhere including standard errors, confidence limit estimation, multiple mediators, qualitative methods, experimental designs, limitations for causal inference, and categorical outcomes ( MacKinnon, 2008 ).

Assumptions of the Single Mediator Model

Although statistical mediation analysis is straightforward under the assumption that the mediation equations above are correctly specified, the identification of true mediating variables is complicated by several testable and untestable assumptions ( MacKinnon, 2008 ). New developments in mediation analysis address statistical and inferential assumptions of the mediation model. For the estimator of the mediated effect, simultaneous regression analysis assumptions are required, such as the residuals in Equations 2 and 3 are independent and that M and the residual in Equation 2 are independent ( MacKinnon, 2008 ; McDonald, 1997 ). No XM interaction in Equation 2 is assumed, although this can be tested statistically. The temporal order of the variables in the model is also assumed to be correctly specified (see Cheong, MacKinnon, & Khoo, 2003 ; Cole & Maxwell, 2003 ; MacKinnon, 2008 ). The methods assume a self-contained model such that no variables related to the variables in the mediation equations are omitted from the estimated model and that coefficients estimate causal effects ( Holland, 1988 ; Imai, Keele, & Tingley, 2010 ; Lynch, Cary, Gallop, & Ten Have, 2008 ; Ten Have et al., 2007 ; VanderWeele, 2010 ). It is also assumed that the model has minimal errors of measurement ( James & Brett, 1984 ; McDonald, 1997 ).

Moderating Variables

The strength and form of a relation between two variables may depend on the value of a moderating variable. A moderator is a variable that modifies the form or strength of the relation between an independent and a dependent variable. The examination of moderator effects has a long and important history in a variety of research areas ( Aguinis, 2004 ; Aiken & West, 1991 ). Moderator effects are also called interactions because the third variable interacts with the relation between two other variables. However, theoretically moderator effects differ slightly from interaction effects in that moderators refer to variables that alter an observed relation in the population while interaction effects refer to any situation in which the effect of one variable depends on the level of another variable. As mentioned earlier, the moderator is not part of a causal sequence but qualifies the relation between X and Y . For intervention research, moderator variables may reflect subgroups of persons for which the intervention is more or less effective than for other groups. In general, moderator variables are critical for understanding the generalizability of a research finding to subgroups.

The moderator variable can be a continuous or categorical variable, although interpretation of a categorical moderator is usually easier than a continuous moderator. A moderating variable may be a factor in a randomized manipulation, representing random assignment to levels of the factor. For example, participants may be randomly assigned to a moderator of treatment dosage in addition to type of treatment received in order to test the moderator effect of duration of treatment across the two treatments. Moderator variables can be stable aspects of individuals such as sex, race, age, ethnicity, genetic predispositions, and so on. Moderator variables may also be variables that may not change during the period of a research study, such as socioeconomic status, risk-taking tendency, prior health care utilization, impulsivity, and intelligence. Moderator variables may also be environmental contexts such as type of school and geographic location. Moderator variables may also be baseline measure of an outcome or mediating measure such that intervention effects depend on the starting point for each participant. The values of the moderating variable may be latent such as classes of individuals formed by analysis of repeated measures from participants. The important aspect is that the relation between two variables X and Y depends on the value of the moderator variable, although the type of moderator variable, randomized or not, stable characteristic, or changing characteristic often affects interpretation of a moderation analysis. Moderator variables may be specified before a study as a test of theory or they may be investigated after the study in an exploratory search for different relations across subgroups. Although single moderators are described here referring to the situation where the relation between two variables differs across the levels of a third variable, higher-way interactions involving more than one moderator are also possible.

Reasons for including moderating variables in a research study

There are several overlapping reasons for including moderating variables in a research study.

- Acknowledgment of the complexity of behavior: The investigation of moderating variables acknowledges the complexity of behavior, experiences, and relationships. Individuals are not the same. It would be unusual if there were no differences across individuals. This focus on individual versus group effects is more commonly known as the tendency for researchers to be either lumpers or splitters ( Simpson, 1945 ). Lumpers seek to group individuals and focus on how persons are the same. Splitters, in contrast, look for differences among groups. By making this distinction, I guess I am a splitter. Generally, the search for moderators is a goal of splitters while lumpers would tend not to focus on moderator variables but on general results across all persons. Of course both approaches have problems with splitters yielding smaller and smaller groups until there is one person in each group. Lumpers will fail to observe real subgroups, including subgroups that may have iatrogenic effects or miss predictive relations because of opposite effects in subgroups.

- Manipulation check: If there is an additional experimental factor picked so that an observed relation is differentially observed across subgroups, then the intervention effect is a test of the intervention theory. For example, if dose of an intervention is manipulated as well as intervention or control, then the additional dosages could be considered a moderator and if the intervention effect is successful, the size of the effect should differ across levels of dosage.

- Generalizability of results: Moderation analysis provides a way to test whether an intervention has similar effects across groups. It would be important, for example, to demonstrate that intervention effects are obtained for males and females if the program would be disseminated to a whole group containing males and females. Similarly, the consistency of an intervention effect across subgroups demonstrates important information about the generalizability of an intervention.

- Specificity of effects: In contrast to generalizability, it is important to identify groups for which an intervention has its greatest effects or no effects. This information could then be used to target groups for intervention thereby tailoring of an intervention.

- Identification of iatrogenic effects in subgroups: Moderation analysis can be used to identify subgroups for which effects are counterproductive. It is possible that there will be subgroups for which the intervention causes more negative outcomes.

- Investigation of lack of an intervention effect: If there are two groups that are affected by an intervention in opposite ways, the overall effect will be nonsignificant even if there is a statistically significant intervention effect in both groups, albeit opposite. Without investigation of moderating variables, these types of effects would not be observable. In addition, before abandoning an intervention or area of research it is useful to investigate subgroups for any intervention effect. Of course, this type of exploratory search must consider the possibility of multiplicity where by testing more effects will lead to finding effects by chance alone.

- Moderators as a test of theory: There are situations where intervention effects may be theoretically expected in one group and not another. For example, there may be different social tobacco intervention effects for boys versus girls because reasons for smoking may differ across sex. In this way, mediation and moderation may be combined if it is expected that a theoretical mediating process would be present in one group but not in another group.

- Measurement improvement: Lack of a moderating variable effect may be due to poor measurement of the moderator variable. Many moderator variables have reasonably good reliability such as age, sex, and ethnicity but others may have measurement limitations such as risk-taking propensity or impulsivity.

- Practical implications: If moderator effects are found, then decisions about intervention delivery may depend on this information. If intervention effects are positive at all levels of the moderator, then it is reasonable to deliver the whole program. If intervention effects are observed for one group and not another, it may be useful to deliver the program to the group where it had success and develop a new intervention for other groups. Of course, there are cases where the delivery of an intervention as a function of a moderating variable cannot be realistically or ethically used in the delivery of an intervention. For example, it may be realistic to deliver different programs to different ages and sexes but less realistic to deliver programs based on risk taking, impulsivity, or prior drug use, for example, because of labeling of individuals or practical issues in identifying groups. By grouping persons for intervention, there may also be iatrogenic effects, for example, grouping adolescent drug users together may have harmful effects by enhancing a social norm to take drugs in this group.

How to include moderators in a research study

Moderators such as age, sex, and race are often routinely included in surveys. Demographic characteristics are also often measured including family income, marital status, number of siblings, and so on. Other measures of potential moderators have the same measurement and time demand issues as for mediating variables described earlier; that is, additional measures may increase respondent burden.

Moderation Regression Equations

The single moderating variable effect model is shown in Figure 2 and summarized in Equation 4 .

Where Y is the dependent variable, X is the independent variable, Z is the moderator variable, and XZ is the interaction of the moderator and the independent variable; e 1 is a residual, and c 1 , c 2 , and c 3 represent the relation between the dependent variable and the independent variable, moderator variable, and moderator by independent variable interaction, respectively. The moderating variable XZ is the product of X and Z where X and Z are often centered (centered means that the average is subtracted from each observed value of the variable). If the XZ interaction is statistically significant, the source of the significant interaction is often explored by examining conditional effects with contrasts and plots. More on interaction effects including procedures to plot interactions and test contrasts can be found in Aguinis (2004) , Aiken and West (1991) , Keppel and Wickens (2004) , and Rothman, Greenland, and Lash (2008) .

Assumptions of Moderation Analysis

There are several challenges to accurate identification of moderator effects. For example, interactions are often scale dependent so that changing the measurement scale can remove an interaction effect. The range of values of the moderator may affect whether a moderator effect can be detected. The number of moderators tested may increase the chance of finding a Type I error and the splitting of the total sample into subgroups limits power to detect moderator effects. Several types of interaction effects are possible that reflect different conclusions, for example, an intervention effect may be statistically significant and beneficial in each group but the effect may differ, an intervention effect may be statistically significant in one group but not another, and so on. More on these issues can be found in Aiken and West (1991) and Rothman et al. (2008) and a special issue on subgroup analysis in a forthcoming issue of the journal Prevention Science .

Moderation and Mediation in the Same Analysis

Both moderating and mediating variables can be investigated in the same research project but the interpretation of mediation in the presence of moderation can be complex statistically and conceptually ( Baron & Kenny, 1986 ; Edwards & Lambert, 2007 ; Fairchild & MacKinnon, 2009 ; Hayduk & Wonnacott, 1980 ; James & Brett, 1984 ; Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007 ). There are two major types of effects that combine moderation and mediation as described in the literature ( Baron & Kenny, 1986 ; Fairchild & MacKinnon, 2009 ): (a) moderation of a mediation effect , where the mediated effect is different at different values of a moderator and (b) mediation of a moderation effect , where the effect of an interaction on a dependent variable is mediated.

An example of moderation of a mediation effect is a case where a mediation process differs for males and females. For example, a program may affect social norms equally for both males and females but social norms only significantly reduce subsequent tobacco use for females not for males. These types of analyses can be used to test homogeneity of action theory across groups and homogeneity of conceptual theory across groups ( MacKinnon, 2008 ). An example of moderation of a mediated effect is a case where social norms mediate the effect of an intervention on drug use but the size of the mediated effect differs as a function of risk-taking propensity. An example of mediation of a moderator effect would occur if the effect of an intervention depends on baseline risk-taking propensity such that the interaction is due to a mediating variable of social norms, which then affects drug use. These types of effects are important because they help specify types of subgroups for whom mediational processes differ and help quantify more complicated hypotheses about mediation and moderation relations. Despite the potential for moderation of a mediation effect and mediation of a moderation effect, few research studies include both mediation and moderation, at least in part because of the difficulty of specifying and interpreting these models. General models that include mediation and moderation have been described that include the single mediator model as a special case and the single moderator model as special cases ( Fairchild & MacKinnon, 2009 ; MacKinnon, 2008 ).

Both mediating variables and moderating variables are ideally specified before the study is conducted. Describing mediation and moderation theory clarifies the purpose of the intervention and forces consideration of alternative interpretations of the results of the study leading to better research design and more information gleaned from the study. Stable characteristic moderator variables such as age and sex are often routinely included in research studies. Often existing studies include some measures of moderating and mediating variables so that mediation and moderation analysis of many existing data sets can be conducted. More information can be obtained from these studies if mediation and moderation analyses are conducted.

There are some limitations of including moderating and mediating variables. First, there is the cost and time spent developing mediation and moderation theory prior to a study. It is likely that consideration of these variables may alter the entire design of a study possibly delaying an important research project. However, it is likely that interventions will be more successful if based on theory and prior research and the application of these analyses inform the next intervention study. Second, there are substantial conceptual and statistical challenges to identifying true moderating and mediating variables that require a program of research. The identification of true mediating processes, for example, requires a program of research with information from many sources. Third, the questions added to a survey to measure mediating and moderating variables must be balanced with the quality of data collected. A longer survey that bores participants or renders some or all of their data inaccurate will not help a research project. Nevertheless, the addition of mediating and moderating variables to any research program reflects the maturation of scientific research to addressing the specifics of how and for whom interventions achieve their effects.

Acknowledgments

The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by Public Health Service Grant DA0957.

This article was previously presented at the Stockholm Conference on Outcome Studies of Social, Behavioral, and Educational Interventions, on February 7, 2011. It was invited and accepted at the discretion of the editor.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

- Aguinis H. Regression analysis for categorical moderators. New York: Guilford; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1991. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baranowski T, Anderson C, Carmack C. Mediating variable framework in physical activity interventions: How are we doing? How might we do better? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998; 15 :266–297. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986; 51 :1173–1182. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cheong J, MacKinnon DP, Khoo ST. Investigation of mediational processes using parallel process latent growth curve modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003; 10 :238–262. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003; 112 :558–577. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Edwards JR, Lambert LS. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods. 2007; 12 :1–22. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fairchild AJ, MacKinnon DP. A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prevention Science. 2009; 10 :87–99. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fraser MW, Galinsky MJ. Steps in intervention research: Designing and developing social programs. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010; 20 :459–466. [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenland S, Morgenstern H. Confounding in health research. Annual Review of Public Health. 2001; 22 :189–212. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hayduk LA, Wonnacott TH. ‘Effect equations’ or ‘effect coefficients’: A note on the visual and verbal presentation of multiple regression interactions. Canadian Journal of Sociology. 1980; 5 :399–404. [ Google Scholar ]

- Holland PW. Causal inference, path analysis, and recursive structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1988; 18 :449–484. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hyman HH. Survey design and analysis: Principles, cases, and procedures. Glencoe, IL: Free Press; 1955. [ Google Scholar ]

- Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological Methods. 2010; 5 :309–334. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- James LR, Brett JM. Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1984; 69 :307–321. [ Google Scholar ]

- Judd CM, Kenny DA. Estimating the effects of social interventions. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1981a. [ Google Scholar ]

- Judd CM, Kenny DA. Process analysis: Estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Evaluation Review. 1981b; 5 :602–619. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kazdin AE. Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research. 2009; 19 :418–428. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Keppel G, Wickens TD. Design and analysis: A researcher‘s handbook. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson T, Fairburn CG, Agras S. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002; 59 :877–883. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lazarsfeld PF. Interpretation of statistical relations as a research operation. In: Lazarsfeld PF, Rosenberg M, editors. The language of social research: A reader in the methodology of social research. Glencoe, IL: Free Press; 1955. pp. 115–125. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lynch KG, Cary M, Gallop R, Ten Have TR. Causal mediation analyses for randomized trials. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2008; 8 :57–76. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MacKinnon DP. Analysis of mediating variables in prevention intervention studies. In: Cazares A, Beatty LA, editors. Scientific methods for prevention intervention research: NIDA research monograph 139 (DHHS Pub. 94-3631. Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. pp. 127–153. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding, and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000; 1 :173–181. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- MacKinnon DP, Luecken LJ. Statistical analysis for identifying mediating mechanisms in public health dentistry interventions. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 2011; 71 :S37–S46. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McDonald RP. Haldane’s lungs: A case study in path analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1997; 32 :1–38. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes RF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007; 42 :185–227. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern epidemiology. 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Simpson GG. The principles of classification and a classification of mammals. Bulletin of the AMNH. Vol. 85. New York: American Museum of Natural History; 1945. [ Google Scholar ]

- TenHave TR, Joffe MM, Lynch KG, Brown GK, Maisto SA, Beck AT. Causal mediation analyses with rank preserving models. Biometrics. 2007; 63 :926–934. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- VanderWeele TJ. Bias formulas for sensitivity analysis for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology. 2010; 21 :540–551. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weiss CH. How can theory-based evaluation make greater headway? Evaluation Review. 1997; 21 :501–524. [ Google Scholar ]

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Moderating and mediating variables in psychological research

Related Papers

Social Indicators Research

Bruno Zumbo

… of the Society for Research in Child …

Lawrence Hamilton

Johann Jacoby

Statistical mediation and moderation have most prominently been distinguished by Baron and Kenny (1986). More complex models that combine both of these effects have recently received increased attention, namely mediated moderation and moderated mediation (e.g., Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2005). Presently the focus is on a three variable model that is often claimed to represent an instance of moderated mediation or mediated moderation. More specifically, in this model a single variable is considered to simultaneously mediate and moderate the same effect. We show that this specific model however cannot be considered either an instance of mediated moderation nor of moderated mediation. Also, we argue that this particular model is a priori misspecified. A data pattern that seems to agree with this model is recognized as plausible, but it indicates that the model must be modified in one of two ways to be methodologically sound. We conclude by recommending to not use this three variable model and to consider evidence that seemingly agrees with it as evidence that the three variable model is inadequate.

As more complex statistical analyses become accessible through modern computer software packages, so the terms “Mediation”, “Moderation” and “(Statistical) Interaction” see increased use. At the same time, uncertainty continues over their definitions and discrimination as evident in inconsistent guidelines and varying means of testing. Further, while guideline papers continue to be written, to the best of our knowledge none has yet been written specifically for Educational Researchers. Here we address this discrepancy with a provision of clear definitions that discriminate, note real-life ambiguities particular to educational research, and cover the various means of testing that are available for researchers. The paper ends with the provision of an example Moderation from educational research which is tested with three alternative statistical approaches, the results of which are then compared and contrasted.

Annual Review of Psychology

David P Mackinnon

Learning and Individual Differences

Fabrice Dosseville

Nabhan Sanusi

JeeWon Cheong , Angela Pirlott , David P Mackinnon

Muhammad Hafizh

Learning is the process of developing the attitude and personality of the students through various stages and experiences. In the achievement of goals requires methods and media as a tool to explain the subject in developing the attitude and personality of the student. The method used should be in accordance with the subject matter taught. Teachers can do a combination of methods and complement with certain media including music. Utilization of music as a medium of learning that makes the learning process fun and not boring. Music can balance the intellectual and emotional intelligence so that it will provide good results for students. In addition music also affects physiological conditions. Relaxing physiological conditions will inspire students to follow the learning process. Relaxation accompanied by music keeps the mind ready and able to concentrate more on receiving lessons. The most helpful music in the learning process is baroque music. Baroque music uses distinctive taps and patterns that automatically synchronize students' bodies and minds. In addition there is a classical music that is said to be able to balance between the right brain with the left brain or commonly called the intellectual intelligence with the emotional students. Students who have received music education from an early age, adults will become human beings who have logical thinking, intelligent, creative, able to make decisions and possess empathy.

Behavior Research Methods

The effect of justice sensitivity on malevolent creativity: the mediating role of anger and the moderating role of emotion regulation strategies

- Yan Wang 1 na1 ,

- Keke Zhang 1 na1 ,

- Fangfang Xu 1 ,

- Yayi Zong 1 ,

- Lujia Chen 1 &

- Wenfu Li 1

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 265 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

88 Accesses

Metrics details

the AMORAL model emphasizes the close connection of individuals’ belief system and malevolent creativity. Belief in a just world theory (BJW) states that people have a basic need to believe that the world they live in is just, and everyone gets what they deserve. Therefore, justice matters to all people. Justice sensitivity, as one of individual trait, has been found associated with negative goals. However, relevant studies have not tested whether justice sensitivity can affect malevolent creativity and its psychological mechanisms. Additionally, researchers have found that both anger and emotion regulation linked with justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity, but their contribution to the relationship between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity remained unclear. The current study aims to explore the influence of justice sensitivity on malevolent creativity, the mediating effect of trait anger/state anger on the relationship between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity, and the moderating effect of emotion regulation on this mediating effect.

A moderated mediating model was constructed to test the relationship between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity. A sample of 395 Chinese college students were enrolled to complete the questionnaire survey.

Justice sensitivity positively correlated with malevolent creativity, both trait anger and state anger partly mediated the connection between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity. Moreover, emotion regulation moderated the indirect effect of the mediation model. The indirect effect of justice sensitivity on malevolent creativity through trait anger/state anger increased as the level of emotion regulation increased. The results indicated that justice sensitivity can affect malevolent creativity directly and indirectly through the anger. The level of emotion regulation differentiated the indirect paths of justice sensitivity on malevolent creativity.

Conclusions

Justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity was mediated by trait anger/state anger. The higher sensitivity to justice, the higher level of trait anger/state anger, which in turn boosted the tendency of malevolent creativity. This indirect connection was moderated by emotion regulation, individuals with high emotion regulation are better able to buffer anger from justice sensitivity.

Peer Review reports

Creativity is generally believed that it is beneficial and positive. Researchers pointed out that creativity refers to the ability to generate novel and appropriate ideas or products in a specific environment [ 1 ]. However, creativity is not always positive. People also have some novel but negative ideas and behaviors—malevolent creativity, which refers to original and premeditated ideation deliberately performed in order to realize one’s own goals and desires, and it always leads to negative consequences, such as new types of fraud, murder, etc [ 2 ]. A wide variety of malevolent creativity instances can be found everywhere and cause damage in original or innovative ways, and it is hard to detect and prevent [ 3 ]. Therefore, it is of great social significance to reveal the influence factors of malevolent creativity and explore the effective regulation strategies to reduce the potential harm.

The AMORAL model emphasized individuals’ belief system, or their interconnected set of beliefs helped determine whether and to what extent they engage in malevolent creativity. Moreover, the drivers of malevolent creativity also included the need to align actions with belief systems [ 4 ]. At the same time, belief in a just world theory (BJW) stated that people had a basic need to believe that the world they lived in is just, and everyone got what they deserved [ 5 , 6 ]. Researchers had found that individuals were more frequently exhibit malevolent creativity in hostile, angry, injustice, and vengeful situation [ 7 ]. Meanwhile, social exchange theory stated that justice was the basis of social exchange and an essential element of effective social interaction. Injustice in an organization or group was a source of stress for its members which were provoked into negative emotions and even outright antisocial aggression by differential treatment [ 8 ]. Therefore, the feeling of injustice may matter to malevolent creativity.

A variety of studies examining the distributive, interpersonal, and procedural justice showed that it was perceived justice, not objective circumstances, shaped responses to injustice [ 9 ]. Justice sensitivity is an individual trait, which is reflected in the difficulty of detecting injustices and the intensity of the response to injustices. Individuals with high justice sensitivity are more likely to perceive injustice than those with low justice sensitivity [ 10 ]. Schmitt et al. categorized justice sensitivity into four types: victim sensitivity, observer sensitivity, beneficiary sensitivity and perpetrator sensitivity [ 11 ]. Mohiyeddini and Schmitt found that justice sensitivity performed better than other variables (e.g., trait anger, anger out, and self-assertiveness) in predicting reactions to unfair treatment [ 12 ]. There was a study found that individuals tend to establish negative goals when they encountered unfair situations, which may lead to the emergence of malevolent creativity [ 13 ]. Another studies also showed that justice sensitivity closely positively correlated kinds of externalizing problems, such as relational, proactive, and reactive aggression in adults [ 14 ] and peer victimization [ 15 ]. What’s more, Gollwitzer et al. found victim sensitivity was associated negatively with prosocial behavior and positively with antisocial behavior [ 16 ]. Prior studies verified that people who have encountered an injustice situation would show more malevolent creativity. However, it remains unknown whether justice sensitivity can affect malevolent creativity and how it affects malevolent creativity. Therefore, the current study focused on the influence of justice sensitivity on malevolent creativity and explored the underlying mechanisms.

Anger is a basic emotional state, according to State-Trait Anger theory, which can be divided into state anger and trait anger [ 17 ]. State anger is a temporary emotional state which composed of subjective feelings and physiological activities. On the other hand, trait anger is defined as a stable personality characteristic, a general tendency of angry reaction under the induced stimulus, and a relatively stable individual difference in frequency, intensity and duration of state anger [ 18 ]. High-trait angry individuals are more inflamed and easily develop state anger, then show more maladaptive cope including verbal and physical confrontation [ 19 , 20 ].

Equity theory stated that negative emotions such as anger and resentment were aroused when individuals realized they had been treated unfairly [ 21 ]. Social psychological researches indicated that anger was the predominant emotional response to perceiving injustice [ 22 , 23 ]. A number of empirical studies also examined the relationship between anger and injustice, and indicated that the level of anger was higher when individuals perceived injustice or had been treated unfairly [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Furthermore, researches showed that facets of anger (i.e., state, trait, expression, inhibition) linked with perceived injustice [ 28 , 29 ]. Schmitt et al. also found justice sensitivity related with trait anger [ 30 ]. Additionally, individuals with high justice sensitivity may be more likely to have a stronger reaction when they accounted injustice events, which might in turn produce a higher degree of state anger.

It has been shown that feeling unfair treatment can give people a sense of relative deprivation [ 31 ], which lead to anger and criminal behavior [ 10 , 32 , 33 ]. Anger was an emotion with high arousal and approach orientation which could reinforce cognitive activation state, and allowed the person to mobilize more adequate cognitive resources to engage in the current cognitive activity (e.g., creative thinking). Therefore, anger could facilitate creative performance [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. Cheng et al. conducted an experimental study with the malevolent creativity task (MCT) and found that malevolent creativity performance can be significantly promoted in anger group [ 38 ]. Therefore, anger may be a potential mediating variable between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity.

Previous studies explored induced anger emotion in the laboratory, but few researches examined the relationship between anger and malevolent creativity under natural conditions. There was a study shown that trait anger could significantly and positively predicted aggression [ 39 ]. And other study also found that state anger could influence an individual’s tendency to aggression through anger rumination [ 40 ]. Thus, the current study speculated that both trait anger and state anger may influence the tendency to malevolent creativity. Additionally, whether trait anger and state anger play a different role between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity is still unknown. Therefore, both state anger and trait anger deserve attention. Considering the differences between the two kinds of anger, the current study separately examined their roles between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity.

However, in realistic situations, justice-sensitive individuals do not always produce extreme anger emotion and generate tendency to malevolent creative behavior when they faced with injustice events. This may closely rely on the regulation and control of emotion production, perception, and expression.

Emotion regulation, composed of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, is defined as a series of cognitive processes adjusting or changing the appearance, intensity and duration of emotion [ 41 ]. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approaches proved that angry emotion can be best downregulated by those emotion regulation strategies, such as modifying negative thoughts, or reappraising the anger-provoking situation [ 42 ]. Furthermore, according to Gross’s process model of emotion regulation, strategies that act early in the emotion-generative process might differ from the later one in consequences [ 43 ]. Cognitive reappraisal is an antecedent-focused strategy used before an emotion occurs, individual can change the emotional experience by altering the perception of a negative event. Expressive suppression, on the other hand, refers to an individual’s ability to alter the external manifestation of emotion by inhibiting expression. That is to say, both can work in the early stages of emotion production. Researchers examined the effects of emotion regulation strategies on both trait anger and state anger, andresults showed that both cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression can counteract short-term anger arousal following provocation [ 42 ]. Numerous studies showed that high level emotion regulation could effectively down-regulate an individual’s anger mood and the related physiological responses [ 42 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. Cheng et al. also found that cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression could effectively reduce the emotional arousal and significantly reduce the malevolent creativity of angry individuals [ 38 ]. Based on previous findings, it is reasonable to expect that cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression may also attenuate the possible effects of justice sensitivity on anger and then weak the impact on malevolent creativity. Therefore, the current study hypothesizes that emotion regulation can play a moderating role between justice sensitivity and anger.

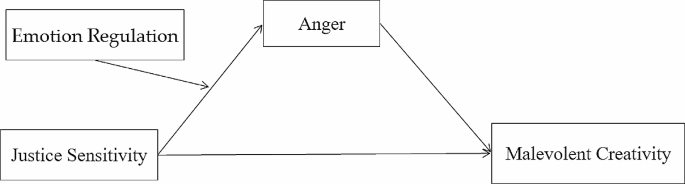

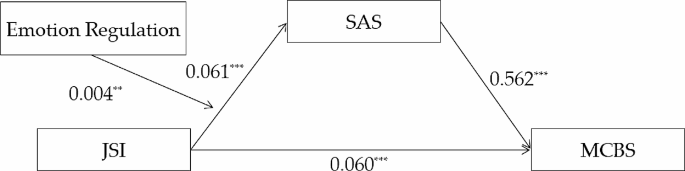

In conclusion, the aims of the present study were: (1) to reveal the influence of justice sensitivity on malevolent creativity; (2) to investigate whether trait anger as well as state anger played mediating role in the association between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity; (3) to explore whether emotion regulation moderated the correlation between justice sensitivity and anger. The hypothetical moderated mediation model was shown in Fig. 1 .

The hypothetical moderated mediation model

Participants

Prior to the beginning of the study, we used the G*Power 3.1. provided by Faul et al. to estimate the required sample size [ 47 ]. With setting the medium effect size f 2 = 0.15, α = 0.05, 95% power (1-β err probability), and the number of predictors = 7, the total sample size was 153.

505 college students participated in this study and volunteered for an online survey on the website. A total of 395 valid questionnaires were collected for the study, out of those, 229 (58%) were from male students and 166 (42%) from female students. The major of participants included science and engineering (23%), medicine (25%), literature and history (22%), arts and sports (22%), and others (15%). 347 (88%) were undergraduates, 25 (6%) were postgraduates and 23 (6%) were others.

Justice sensitivity inventory (JSI)

The Justice Sensitivity Inventory developed by Schmitt was used to measure justice sensitivity [ 11 , 48 , 49 ]. Previous studies had shown that the scale had good reliability and was widely used [ 10 , 50 ]. This scale consisted of four subscales: victim sensitivity, observer sensitivity, beneficiary sensitivity, and perpetrator sensitivity. Each subscale consisted of 10 questions and was scored on a 6-point Likert scale (e.g. I cannot easily bear it when others profit unilaterally from me.). This scale was scored from strongly disagree to strongly agree as 1–6. The JSI score is the sum of all the item scores. Higher scores indicated higher justice sensitivity. Cronbach’s α for justice sensitivity in this study was 0.97.

Trait anger scale (TAS)

Trait anger was measured by the Chinese version of the Trait Anger Scale [ 20 , 51 ], which consisted of 10 items (e.g. I’m easily irritated.). Studies showed that the scale had good reliability and validity, and widely used in China [ 52 , 53 ]. This scale was scored on a 4-point Likert scale, and the higher total score indicated higher levels of trait anger. The Cronbach’s α for this scale in this study was 0.87.

State anger scale (SAS)

State Anger Scale was developed by Spielberger and revised into Chinese version by Liu [ 54 , 55 , 56 ]. The scale had been widely used in China [ 57 ]. This scale consisted of 15 items (e.g. I’m angry.) and included three subscales: anger feelings, anger words, and anger actions. This scale was scored on a 4-point scale, with 1 (not at all), 2 (a little), 3 (moderately), and 4 (very strongly). The higher score, the more pronounced state anger. Cronbach’s α for this scale in this study was 0.92.

Emotion regulation questionnaire (ERQ)

Emotion regulation was evaluated by a 10-item self-report version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ). The scale was developed by Gross and revised into Chinese version by Wang et al. [ 58 , 59 ]. The Chinese version of ERQ had good construct validity, retest reliability, and internal consistency reliability [ 60 , 61 ]. ERQ was consisted of two subscales, including 6 items (e.g. I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in.) for cognitive reappraisal and 4 items for expressive suppression (e.g. I don’t show my emotions.). This scale was rated on a 7-point. The higher total score indicated more frequent use of emotion regulation strategies. Cronbach’s α for this scale in this study was 0.72.

Malevolent creativity behavior scale (MCBS)

Malevolent creativity was measured by MCBS, which developed by Hao et al. and could be used to measure the tendency of individuals to exhibit malevolent creativity behaviors in their daily lives [ 62 ]. The scale had a good ecological validity, covered various forms of malevolent creativity (e.g., deception, tricks, lies), and was easy to administer [ 62 ]. This scale consisted of 13 items and was scored on a 5-point scale, with 1 (not at all) ∼ 5 (always) (e.g., When I am treated unfairly, I will retaliate in a different way). The scores of all items were summed to obtain the total score. The higher total score indicated that the individual showed more malevolent creativity in daily life. Cronbach’s α for this scale in this study was 0.92.

The descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis were conducted using SPSS 26.0. Regression analyses were used to test the mediating role of trait anger / state anger between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity. PROCESS 3.3 was used to test the moderating role of emotion regulation. The demographic variables (gender, major and grade) were entered in the model as covariates.

Common method bias assessment

Harman’s single-factor test was used for exploring the common method bias of the data. All of items of JSI, TAS, SAS, ERQ and MCBS were put into the un-rotated exploratory factor analysis. The results showed that the number of factors with an eigenvalue greater than 1.00 was 17, and the explained variance of the first factor was 28.85, which was lower than the critical criterion of 40% [ 63 ]. The results indicated that there was no obvious common method bias in the data of this study.

Descriptive statistical and correlational analysis

As shown in Table 1 , all of the variables were significantly correlated with each other. The score of JSI was significantly positively correlated with the score of TAS, SAS and MCBS, and were significantly negatively correlated with the score of ERQ. Both TAS and SAS were significantly negatively correlated with ERQ and positively correlated with MCBS.

Analysis of the mediating role of trait anger and state anger

Regression analysis was used to test the mediating role of trait anger and state anger between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity [ 64 , 65 ].

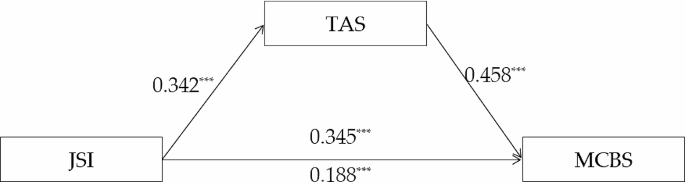

Trait anger as the mediator

Three regression models were constructed to test the mediating role of trait anger. Firstly, malevolent creativity entered the model as a dependent variable, then demographic variables (gender, major and grade) entered the first block as control variables, and justice sensitivity entered the equation as predictor variable. Secondly, trait anger entered the model as a dependent variable, then demographic variables (gender, major and grade) entered the first block as control variables, and justice sensitivity entered the second block as predictor variable. Finally, malevolent creativity entered the model as a dependent variable, then demographic variables (gender, major and grade) entered the first block as control variables, and justice sensitivity and trait anger entered the equation as predictor variables. The results were shown in Table 2 . It showed that justice sensitivity significantly positively predicted malevolent creativity ( c = 0.345, t = 7.262, p < 0.001) and trait anger ( a = 0.342, t = 7.392, p < 0.001), while trait anger significantly and positively predicted malevolent creativity ( b = 0.458, t = 9.839, p < 0.001). Additionally, the direct effect (path c ’) of justice sensitivity on malevolent creativity was statistically significant ( c ’ = 0.188, p < 0.001). Therefore, the mediation model was confirmed, which indicated that the relationship between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity was partially mediated by trait anger. The indirect effect was 0.157 (95% CI [0.111, 0.209]), which accounted for 45.51% of the total effect. The model diagram was shown in Fig. 2 .

The mediating role of trait anger between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity

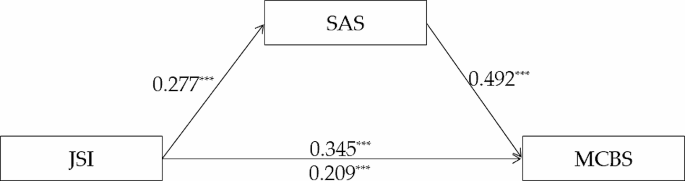

State anger as the mediator

Similar to trait anger, hierarchical regression analysis was used to examine the mediating role of state anger. The results were shown in Table 3 . It showed that justice sensitivity significantly and positively predicted malevolent creativity ( c = 0.345, t = 7.262, p < 0.001) and state anger ( a = 0.277, t = 5.903, p < 0.001), while state anger significantly and positively predicted malevolent creativity ( b = 0.492, t = 10.958, p < 0.001). Therefore, the mediation model was confirmed, which indicated that the relationship between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity was partially mediated by state anger. The indirect effect was 0.136 (95% CI [0.087, 0.188]), which accounted for 39.50% of the total effect. The model diagram was shown in Fig. 3 .

The mediating role of state anger between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity

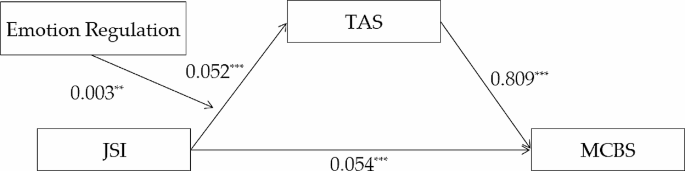

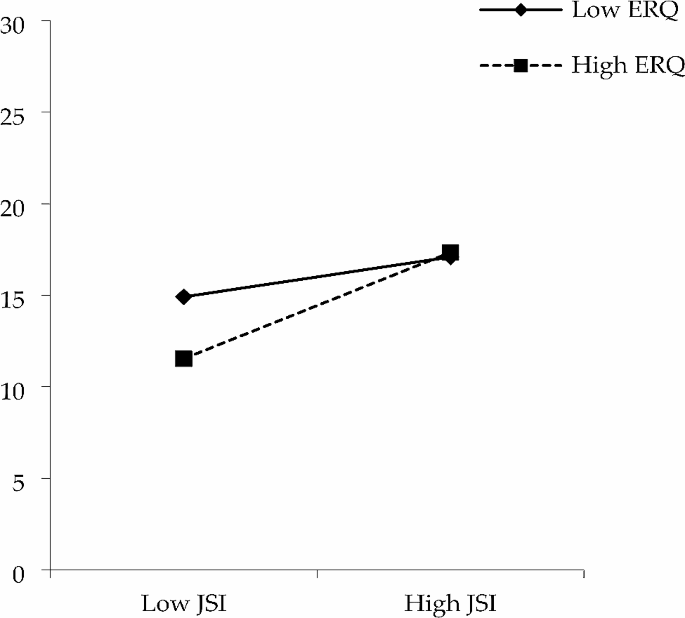

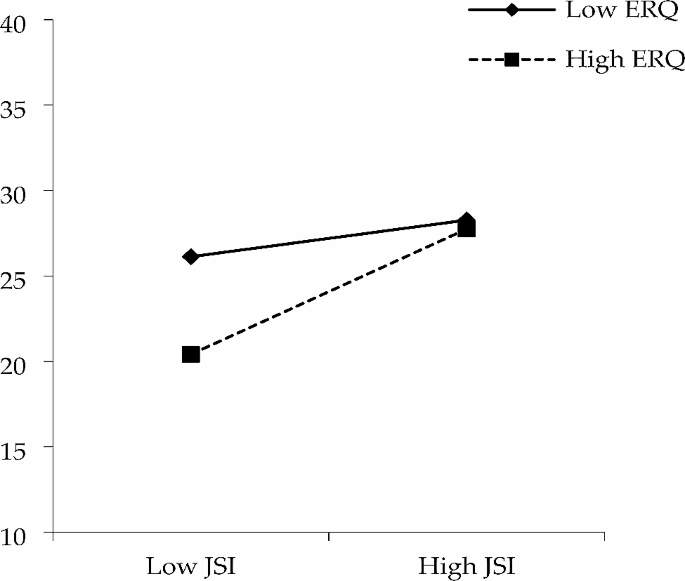

Analysis of the moderating role of emotion regulation

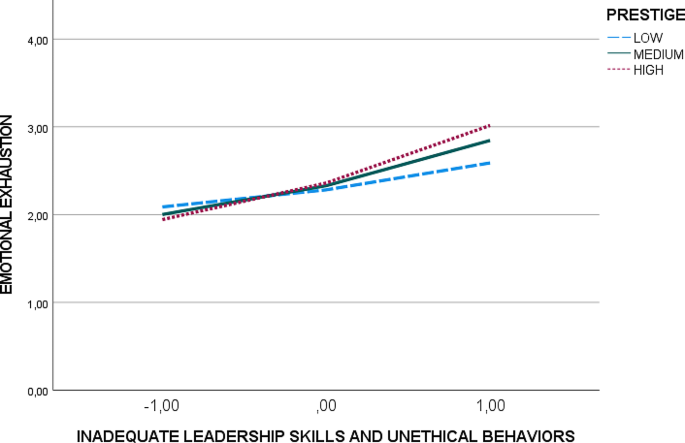

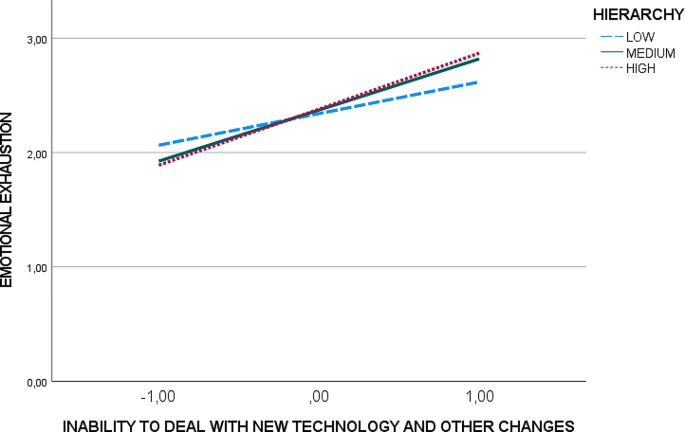

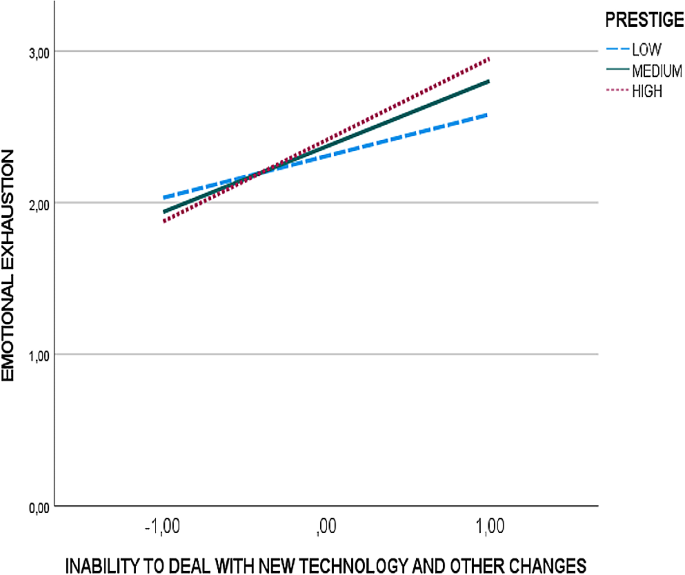

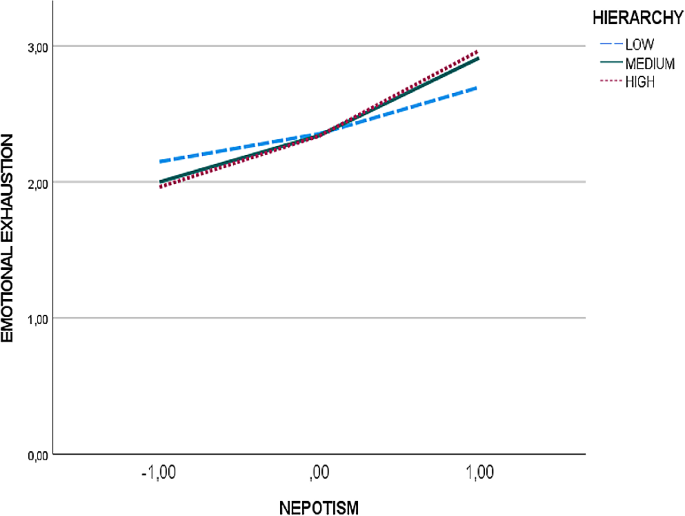

Model 7 in PROCESS 3.3 developed by Hayes was used to explore the hypothesized moderated mediation model [ 66 ], as shown in Figs. 4 and 5 , the indirect association between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity was moderated by emotion regulation. The results showed that the interaction of justice sensitivity and emotion regulation significantly predicted trait anger (B = 0.003, t = 3.021, p = 0.003), as well as state anger (B = 0.004, t = 2.765, p = 0.006).

The moderated mediation models (trait anger as the mediator)

The moderated mediation models (state anger as the mediator)

As shown in Figs. 6 and 7 , justice sensitivity could significantly and positively predict trait anger ( β = 0.075, t = 7.024, p < 0.001) and state anger ( β = 0.095, t = 5.532, p < 0.001), when the level of emotional regulation was high. Meanwhile, justice sensitivity could significantly predict trait anger positively ( β = 0.028, t = 2.538, p = 0.012) instead of state anger ( β = 0.028, t = 1.560, p = 0.120), when the level of emotional regulation was low. Additionally, justice sensitivity had a stronger predictive effect on trait anger and state anger when the level of emotion regulation was higher. The results suggested that higher levels of emotion regulation could serve as a buffer against the influences of justice sensitivity on trait anger and state anger among low justice sensitivity individuals. However, the moderating effect of emotion regulation was no longer significant when an individual’s justice sensitivity was high.

The effects of emotion regulation on the mediating pathway of justice sensitivity → trait anger → malevolent creativity (index = 0.0021, SE = 0.0007, 95% CI: [0.0008, 0.0036]) and justice sensitivity \(\to\) state anger \(\to\) malevolent creativity (index = 0.0021, SE = 0.0009, 95% CI: [0.0005, 0.0039]) were all statistical significant. The details were shown in Table 4 . The indirect effects through trait anger were both significant in participants with high and low emotion regulation. Meanwhile, the indirect effects through state anger were significant in participants with high emotion regulation and not those with low emotion regulation.

The interaction effect of JSI and ERQ on TAS

The interaction effect of JSI and ERQ on SAS

To advance the understanding of malevolent creativity, the present study investigated a moderated mediation model to revealed the association between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity. As hypothesized, the correlation between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity was mediated by trait anger/state anger. The higher sensitivity to justice, the higher level of trait anger/state anger, which in turn boosted the tendency of malevolent creativity. Additionally, this indirect connection was moderated by emotion regulation. To be specific, the indirect effects through trait anger were both significant in participants with high and low emotion regulation, however, the indirect effects through state anger were significant in participants with high emotion regulation but not those with low emotion regulation.

The association between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity

The results of this study found that justice sensitivity significantly positively predicted malevolent creativity, which was in line with prior researches. Individuals who were not treated fairly would experience more negative emotions and show more negative behaviors. For example, Brebels et al. found that participants who faced unequal distributional outcomes stole more money from the manager [ 67 ]. Another study found that organizational injustice perception which included procedural justice and interpersonal justice could negatively predict workplace deviance, and the relationships mediated by negative emotion [ 68 ].

Justice is an important means to defend self-benefit in society. The Sensitivity to Mean Intentions Model (SeMI) states that individuals with higher level of justice sensitivity have a lower threshold for perceiving malicious information in offensive or threatening situations compared to individuals with low justice sensitivity. That’s why high justice sensitivity individuals tend to actively search for or focus on information unfavorable to them, and then activate a suspicious mindset after perceiving malicious intentions [ 69 ]. Therefore, individuals with high justice sensitivity were more attentive to unfair stimuli and activated easily by the unfair information, which might prompt them to take steps to defend the fairness and self-benefit [ 10 ]. As a result, these people might tend to engage in more negative deviant behaviors [ 70 ], and be more likely to harm others, i.e., show more malevolent creativity. Previous studies demonstrated that people tend to exhibit malevolent creativity in threatened context, e.g. bullying victimization [ 71 ], unfair [ 13 ]. Clark and James found that perceptions of unfair treatment enhanced instances of negative creativity whereas perceptions of fair treatment yielded more positive creativity [ 13 ]. Another research also found individuals who were more implicitly aggressive and less premeditative were more likely to be malevolently creative in response to situations that provoke malevolent creativity [ 7 ]. These results might indicate that situational perceptions, such as justice and fairness, could influence the degree to which creative products are negative. Therefore, high level justice sensitive may generate high level malevolent creativity.

In other hand, justice sensitive individuals do not entirely behave in accordance with norms of justice, sometimes they could show protest and retaliate more strongly at once when they counter injustice [ 69 ]. For example, researchers found victim-sensitive individuals tended to make unfair offers when they had the power to distribute money at will between themselves and another person [ 72 ]. Another study also showed higher victim sensitivity predicted higher relational, proactive, and reactive aggression, and higher observer sensitivity predicted higher physical and verbal aggression [ 14 ]. Schmitt et al. found that vengeful reactions of laid-off employees toward their former employer depended directly and indirectly—mediated by the perceived fairness of the lay-off procedure—on justice sensitivity [ 73 ]. Meanwhile existing studies found that individuals who tend to break rules or had a weak sense of rule compliance were more likely to possess higher creativity [ 74 ].

In summary, it is plausible that justice sensitivity positively predicts the tendency of malevolent creativity. Individuals with high justice sensitivity are more likely to perceive information about injustice and generate aggressive thoughts and behaviors. This may mean that justice sensitivity individuals also have a tendency to break the rules. The aggressive performance may send a message to the perpetrator that what he has done is reprehensible, at the same time, the performance also is a way to respond injustice in order to avoid similar harm in the future [ 75 ]. Thus, individuals with higher justice sensitivity are more likely to generate aggressive thoughts or behaviors and harm others intentionally, so that resulting in higher level of malevolent creativity.

The mediating role of anger

The results of this study found that both trait anger and state anger mediated the relationship between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity. Specifically, justice sensitivity could not only directly affect malevolent creativity but also indirectly affect malevolent creativity through trait anger/state anger. This result was consistent with previous studies. Some researchers found that justice sensitivity positively predicted anger [ 38 , 76 , 77 ]. Schmitt et al. described justice sensitivity as: “Individuals differ in how sensitive they are to justice; how easily they are able to perceive injustice; and how strongly they react to perceived injustice” [ 11 ]. Thus, justice sensitivity was a good predictor of an individual’s response to injustice, those with high justice sensitivity tended to respond more strongly to injustice. To be specific, individuals with high justice sensitivity, when confronted with an injustice allocation scheme, would produce a significant increase in the level of negative emotional arousal, which further lead to an increase in anger [ 10 ]. The state of anger, on the other hand, exacerbated the conflict and mistrust in society, undermined the interpersonal interaction and cooperation. Under the emotion of anger, individuals were able to generate more creative and more damaging ideas, which were destructive to society and others [ 38 ]. Lastly, this increased the level of malevolent creativity tendency.

The moderating role of emotion regulation

Our results also revealed that emotion regulation moderated the effect of justice sensitivity on trait anger and state anger. Individuals with high levels of emotion regulation were more likely to avoid anger triggered by justice sensitivity than individuals with low emotion regulation. There is a plausible explanation regarding the moderate role of emotion regulation. As mentioned earlier, individuals who perceive unfairness typically experienced high levels of emotional arousal, while both cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression emotion regulation strategies were effective in decreasing emotional arousal and implicit aggression [ 38 ]. Thus, individuals with high levels of emotion regulation were better able to regulate anger arising from perceived injustice, which in turn reduced the level of malevolent creativity tendency.

Additionally, the current study found that the moderating effect of emotion regulation was different on trait anger and state anger. Justice sensitivity could positively predict trait anger when the level of emotional regulation was low. One possible explanation for this difference is that the lower level of ERQ might suggest that individuals do not need emotion regulation strategies to manage their emotions frequently. This might indicate that people do not receive external injustice information frequently, so that justice sensitivity as a stable personality trait only can predict the trait anger that has a tighter relationship to it [ 11 ], instead of state anger. Because state anger always depends on the environmental stimuli in the moment.

Although this study revealed possible mechanisms by exploring justice sensitivity influenced on malevolent creativity, there were still some shortcomings. Firstly, justice sensitivity contained multiple components that were not examined separately in this study. Future research could delve into the relationship between different components of justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity. Secondly, this study did not examine whether there was a difference in the role of cognitive reappraisal and expression suppression, which could be further explored in future studies. Future studies also could choose to incorporate other types of emotion regulation strategies and compare the effects of different emotion regulation strategies. Finally, the MCBS was utilized in current study to measure the level of malevolent creativity. Notably, the MCBS, as a measurement tool, could measure potential propensity of malevolent creativity. Some recent studies related to malevolent creativity used malevolent creativity tasks (MCT) to explore malevolent creativity performance. Future research could combine examination of malevolent creativity propensity and malevolent creativity performance to explore the influencing factors and internal mechanisms of malevolent creativity.

In conclusion, the present study validated the association between justice sensitivity and malevolent creativity. The findings illustrated the mediating effect of trait anger/state anger in the pathway from justice sensitivity to malevolent creativity. Additionally, the results also showed evidence of two-way interaction, indicating that emotion regulation moderated the relationship between justice sensitivity and anger. Individuals with high emotion regulation are better able to avoid anger from heightened justice sensitivity than individuals with low emotion regulation.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

Justice Sensitivity Inventory

Trait Anger Scale

State Anger Scale

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

Malevolent Creativity Behavior Scale

Standardized deviation

Standard error

95% Bootstrap Confidence interval

Runco MA, Jaeger GJ. The Standard Definition of Creativity. Creativity Res J. 2012;24(1):92–6.

Article Google Scholar

Cropley DH, Kaufman JC, Cropley AJ. Malevolent creativity: a functional model of creativity in terrorism and crime. Creativity Res J. 2008;20(2):105–15.

Gutworth MB, Cushenbery L, Hunter ST. Creativity for Deliberate Harm: Malevolent Creativity and Social Information Processing Theory. J Creative Behav. 2018;52(4):305–22.

Kapoor H, Kaufman JC. The evil within: the AMORAL model of dark creativity. Theory Psychol. 2022;32(3):467–90.