What You Need to Know About the Book Bans Sweeping the US

What you need to know about the book bans sweeping the u.s., as school leaders pull more books off library shelves and curriculum lists amid a fraught culture war, we explore the impact, legal landscape and history of book censorship in schools..

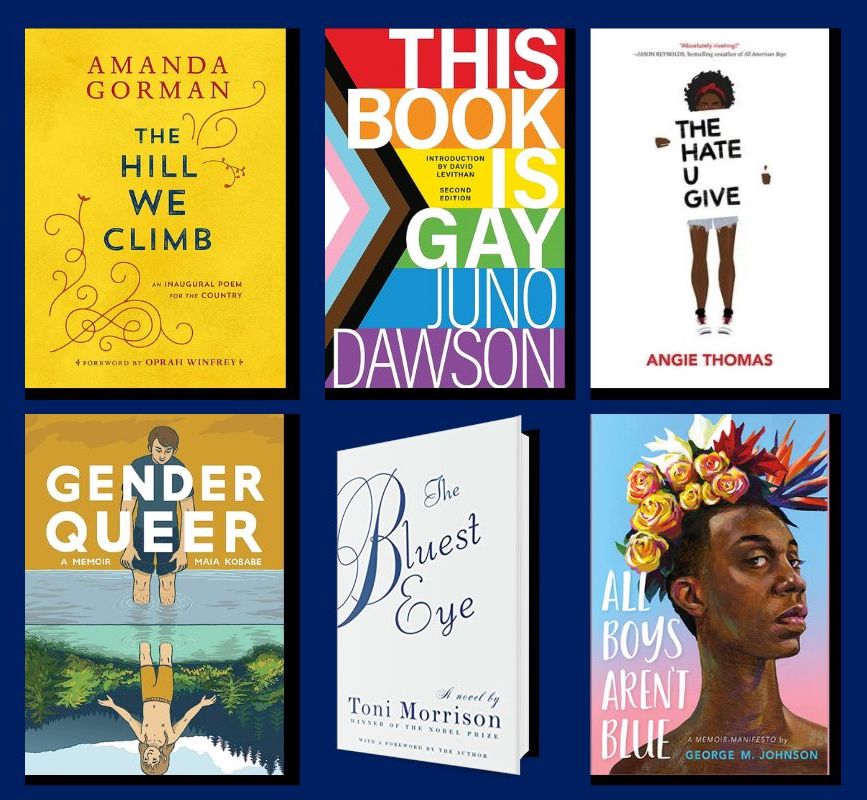

- The American Library Association reported a record-breaking number of attempts to ban books in 2022— up 38 percent from the previous year. Most of the books pulled off shelves are “written by or about members of the LGBTQ+ community and people of color."

- U.S. school boards have broad discretion to control the material disseminated in their classrooms and libraries. Legal precedent as to how the First Amendment should be considered remains vague, with the Supreme Court last ruling on the issue in 1982.

- Battles to censor materials over social justice issues pose numerous implications for education while also mirroring other politically-motivated acts of censorship throughout history.

Here are all of your questions about book bans answered by TC experts.

Alex Eble, Assistant Professor of Economics and Education; Sonya Douglass, Professor of Education Leadership; Michael Rebell, Professor of Law and Educational Practice; and Ansley Erickson, Associate Professor of History and Education Policy. (Photos; TC Archives)

How Do Book Bans Impact Students?

Prior to the rise in bans, white male youth were already more likely to see themselves depicted in children’s books than their peers, despite research demonstrating how more culturally inclusive material can uplift all children, according to a study, forthcoming in the Quarterly Journal of Economics , from TC’s Alex Eble.

“Books can change outcomes for students themselves when they see people who look like them represented,” explains the Associate Professor of Economics and Education. “What people see affects who they become, what they believe about themselves and also what they believe about others…Not having equitable representation robs people of seeing the full wealth of the future that we all can inhabit.”

While books have stood in the crossfire of political battles throughout history, today’s most banned books address issues related to race, gender identity and sexuality — major flashpoints in the ongoing American culture war. But beyond limiting the scope of how students see themselves and their peers, what are the risks of limiting information access?

The student plaintiffs in Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982) march in protest of the Long Island school district's removal of titles such as Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut. While the district would ultimately return the banned books to its shelves, the Supreme Court's ultimate ruling largely allowed school leaders to maintain discretion over information access. (Photo credit: unknown)

“[Book bans] diminish the quality of education students have access to and restrict their exposure to important perspectives that form the fabric of a culturally pluralist society like the United States,” explains TC’s Sonya Douglas s, Professor of Education Leadership. “It's a battle over the soul of the country in many ways; it's about what we teach young people about our country, what we determine to be the truth, and what we believe should be included in the curriculum they're receiving. There's a lot at stake there.”

Material stripped from libraries and curriculum include works written by Black authors that discuss police brutality, the history of slavery in the U.S. and other issues. As such, Black students are among those who may be most affected by bans across the country, but — in Douglass’ view — this is simply one of the more recent disappointments in a long history of Black communities being let down by public education — chronicled in her 2020 book, and further supported by a 2021 study from Douglass’ Black Education Research Center that revealed how Black families lost trust in schools following the pandemic response and murder of George Floyd.

In that historical and cultural context — even as scholars like Douglass work to implement Black studies curriculums — the failure of schools to properly integrate Black experiences into the curriculum remains vast.

“We want to make sure that children learn the truth, and that we give them the capacity to handle truths that may be uncomfortable and difficult,” says Douglass, citing Germany as an example of a nation that has prioritized curriculum that highlights its own injustices, such as the Holocaust. “This moment again requires us to take stock of the fact that racism and bigotry still are a challenging part of American life. When we better understand that history, when we see the patterns, when we recognize the source of those issues, we can then do something about it.”

Beginning in 1933, members of Hitler Youth regularly burned books written by prominent Jewish, liberal, and leftist writers. (Photo: World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo, dated 1938)

Why Is Banning Books Legal?

While legal battles over book censorship in schools consistently unfold at local levels, the wave of book bans across the U.S. surfaces a critical question: why hasn’t the United States had more definitive legal closure on this issue?

In 1982, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a noncommittal ruling that continues to keep school and library books in the political crosshairs more than 40 years later. In Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982), the Court deemed that “local school boards have broad discretion in the management of school affairs” and that discretion “must be exercised in a manner that comports with the transcendent imperatives of the First Amendment.”

But what does this mean in practice? In these kinds of cases, the application of the First Amendment hinges on the existence of evidence that books are banned for political reasons and violate freedom of expression. However, without more explicit guidance, school boards often make decisions that prioritize “community values” first and access to information second.

While today's recent book bans most frequently include topics related to racial justice and gender identity (pictured above), other frequently targeted titles include Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close , The Kite Runner and The Handmaid's Tale . (Cover images courtesy of: Viking Books, Sourcebooks Fire, Balzer + Bray, Oni Press, Random House and Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

“America traditionally has prided itself on local control of education — the fact that we have active citizen and parental involvement in school board issues, including curriculum,” explains TC’s Michael Rebell , Professor of Law and Educational Practice. “We have, whether you want to call it a clash or a balancing, of two legal considerations here: the ability of children to freely learn what they need to learn to be able to exercise their constitutional rights, and this traditional right of the school authorities to determine what the curriculum is.”

So would students benefit from more national and uniform legal guidance on book banning? In this political climate, Rebell attests, the risks very well might outweigh the potential rewards.

“Your local institutions are —in theory — protecting the values you believe in. And if somebody in Washington were going to say that we couldn't have books that talk about transgender rights and things in New York libraries, we'd go crazy, right?” said Rebell, who leads the Center for Educational Equity . “So I can't imagine that in this polarized environment, people would be in favor of federal law, whatever it said.”

Why Do Waves of Book Bans Keep Happening?

Historians date censorship back all the way to the earliest appearance of written materials. Ancient Chinese emperor Shih Huang Ti began eliminating historical texts in 259 B.C., and in 35 A.D., Roman emperor Caligula objected to the ideals of Greek freedom depicted in The Odyssey . In numerous waves of censorship since then, book bans have consistently manifested the struggle for political control.

“We have to think about [the current bans] as part of a longer pattern of fights over what is in curriculum and what is kept out of it,” explains TC’s Ansley Erickson , Associate Professor of History and Education Policy, who regularly prepares local teachers on how to integrate Harlem history into social studies curriculum.

“The United States’ history, since its inception, is full of uses of curriculum to shape politics, the economy and the culture,” says Erickson. “This is a really dramatic moment, but the curriculum has always been political, and people in power have always been using it to emphasize their power. And historically marginalized groups have always challenged that power.”

One example: when Latinx students were forbidden from speaking Spanish in their Southwest schools throughout the 20th century, they worked to maintain their traditions and culture at home.

“These bans really matter, but one of the ways we can imagine a response is by looking back at how people created spaces for what wasn’t given room for in the classroom,” Erickson says.

What Could Happen Next?

American schools stand at a critical inflection point, and amid this heated debate, Rebell sees civil discourse at school board meetings as a paramount starting point for any sort of resolution. “This mounting crisis can serve as a motivator to bring people together to try to deal with our differences in respectful ways and to see how much common ground can be found on the importance of exposing all of our students to a broad range of ideas and experiences,” says Rebell. “Carve-outs can also be found for allowing parents who feel really strongly that certain content is inconsistent with their religious or other values to exempt their children from certain content without limiting the options for other children.”

But students, families and educators also have the opportunity to speak out, explains Douglass, who expressed concern for how her own daughter is affected by book bans.

“I’d like to see a groundswell movement to reclaim the nation's commitment to education — to recognize that we're experiencing growing pains and changes in terms of what we stand for; and whether or not we want to live up to the democratic ideal of freedom of speech; different ideas in the marketplace, and a commitment to civics education and political participation,” says Douglass.

As publishers and librarians file lawsuits to push back, students are also mobilizing to protest bans — from Texas to western New York and elsewhere. But as more local battles unfold, bigger issues remain unsolved.

“We need to have a conversation as a nation about healing; about being able to confront the past; about receiving an apology and beginning that process of reconciliation,” says Douglass. “Until we tackle that head on, we'll continue to have these types of battles.”

— Morgan Gilbard

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the speaker to whom they are attributed. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the faculty, administration, staff or Trustees either of Teachers College or of Columbia University.

Tags: Views on the News Education Policy K-12 Education Social Justice

Programs: Economics and Education Education Leadership History and Education

Departments: Education Policy & Social Analysis

Published Wednesday, Sep 6, 2023

Teachers College Newsroom

Address: Institutional Advancement 193-197 Grace Dodge Hall

Box: 306 Phone: (212) 678-3231 Email: views@tc.columbia.edu

When are book bans unconstitutional? A First Amendment scholar explains

Associate Professor of Law, University of Dayton

Disclosure statement

Erica Goldberg does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Dayton provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

The United States has become a nation divided over important issues in K-12 education, including which books students should be able to read in public school.

Efforts to ban books from school curricula , remove books from libraries and keep lists of books that some find inappropriate for students are increasing as Americans become more polarized in their views.

These types of actions are being called “book banning.” They are also often labeled “censorship.”

But the concept of censorship, as well as legal protections against it, are often highly misunderstood.

Book banning by the political right and left

On the right side of the political spectrum, where much of the book banning is happening, bans are taking the form of school boards’ removing books from class curricula.

Politicians have also proposed legislation banning books that are what some legislators and parents consider too mature for school-age readers, such as “ All Boys Aren’t Blue ,” which explores queer themes and topics of consent. Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison’s classic “ The Bluest Eye ,” which includes themes of rape and incest, is also a frequent target.

In some cases, politicians have proposed criminal prosecutions of librarians in public schools and libraries for keeping such books in circulation.

Most books targeted for banning in 2021, says the American Library Association, “ were by or about Black or LGBTQIA+ persons .” State legislators have also targeted books that they believe make students feel guilt or anguish based on their race or imply that students of any race or gender are inherently bigoted .

There are also some attempts on the political left to engage in book banning as well as removal from school curricula of books that marginalize minorities or use racially insensitive language, like the popular “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Defining censorship

Whether any of these efforts are unconstitutional censorship is a complex question.

The First Amendment protects individuals against the government’s “ abridging the freedom of speech .” However, government actions that some may deem censorship – especially as related to schools – are not always neatly classified as constitutional or unconstitutional, because “censorship” is a colloquial term, not a legal term.

Some principles can illuminate whether and when book banning is unconstitutional.

Censorship does not violate the Constitution unless the government does it .

For example, if the government tries to forbid certain types of protests solely based on the viewpoint of the protesters, that is an unconstitutional restriction on speech. The government cannot create laws or allow lawsuits that keep you from having particular books on your bookshelf, unless the substance of those books fits into a narrowly defined unprotected category of speech such as obscenity or libel. And even these unprotected categories are defined in precise ways that are still very protective of speech.

The government, however, may enact reasonable regulations that restrict the “ time, place or manner ” of your speech, but generally it has to do so in ways that are content- and viewpoint-neutral. The government thus cannot restrict an individual’s ability to produce or listen to speech based on the topic of the speech or the ultimate opinions expressed.

And if the government does try to restrict speech in these ways, it likely constitutes unconstitutional censorship.

What’s not unconstitutional

In contrast, when private individuals, companies and organizations create policies or engage in activities that suppress people’s ability to speak, these private actions don’t violate the Constitution .

The Constitution’s general theory of liberty considers freedom in the context of government restraint or prohibition. Only the government has a monopoly on the use of force that compels citizens to act in one way or another. In contrast, if private companies or organizations chill speech, other private companies can experiment with different policies that allow people more choices to speak or act freely.

Still, private action can have a major impact on a person’s ability to speak freely and the production and dissemination of ideas. For example, book burning or the actions of private universities in punishing faculty for sharing unpopular ideas thwarts free discussion and unfettered creation of ideas and knowledge.

When schools can ‘ban’ books

It’s hard to definitively say whether the current incidents of book banning in schools are constitutional – or not. The reason: Decisions made in public schools are analyzed by the courts differently than censorship in nongovernment contexts.

Control over public education, in the words of the Supreme Court, is for the most part given to “ state and local authorities .” The government has the power to determine what is appropriate for students and thus the curriculum at their school.

However, students retain some First Amendment rights: Public schools may not censor students’ speech, either on or off campus, unless it is causing a “ substantial disruption .”

But officials may exercise control over the curriculum of a school without trampling on students’ or K-12 educators’ free speech rights.

There are exceptions to government’s power over school curriculum: The Supreme Court ruled, for example, that a state law banning a teacher from covering the topic of evolution was unconstitutional because it violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment, which prohibits the state from endorsing a particular religion.

School boards and state legislators generally have the final say over what curriculum schools teach. Unless states’ policies violate some other provision of the Constitution – perhaps the protection against certain kinds of discrimination – they are generally constitutionally permissible.

[ Over 150,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today .]

Schools, with finite resources, also have discretion to determine which books to add to their libraries. However, several members of the Supreme Court have written that removal is constitutionally permitted only if it is done based on the educational appropriateness of the book, but not because it was intended to deny students access to books with which school officials disagree.

Book banning is not a new problem in this country – nor is vigorous public criticism of such moves . And even though the government has discretion to control what’s taught in school, the First Amendment ensures the right of free speech to those who want to protest what’s happening in schools.

- school curriculum

- Public schools

- First Amendment

- US Constitution

- Public libraries

- Toni Morrison

- School Boards

- Glenn Youngkin

- American Library Association

Data Manager

Research Support Officer

Director, Social Policy

Head, School of Psychology

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

The Hydra Nature of Book Banning and Censorship

A snapshot and two annotated bibliographies.

- Michelle Boyd Waters University of Oklahoma

- Shelly K. Unsicker-Durham University of Oklahoma

In Fall of 2022 two researchers set out to explore both scholarly work on censorship and news articles via social media, to help gain a broader understanding of censorship and book banning trends. The following research question guided their research: What does this wave of book banning and censorship look like across the US? What they discovered is a kind of censorship-Hydra, an evolving beast posing an ever-present danger, one that will likely take the courage, collaboration, and ingenuity of educators everywhere. This article offers a snapshot of this current beast of book banning and censorship in the form of two annotated bibliographies—one focused on news reports and trends in social media—the other focused on academic searches of scholarly articles.

Author Biographies

Michelle boyd waters, university of oklahoma.

Michelle Boyd Waters is a doctoral student at the University of Oklahoma studying English education. She taught middle and high school English Language Arts for 10 years and is now studying the establishment and impact of writing centers in high schools. She is the Graduate Student Assistant Director at the OU Writing Center, an Oklahoma Writing Project Teacher Consultant, and co-editor of the Oklahoma English Journal.

Shelly K. Unsicker-Durham, University of Oklahoma

After 23 years of teaching English Language Arts, Shelly is a PhD candidate with the University of Oklahoma in Instructional Leadership and Academic Curriculum, where she has also served as graduate instructor, researcher, and co-editor of Study & Scrutiny. Her favorite research pursuits include expressive writing pedagogy, teacher conversations, and young adult literature.

THREE REFERENCE LISTS:

REFERENCES FOR ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY #1

Authors speak out on censorship. (2022, March 11). National Council of Teachers of English. https://ncte.org/resources/ncte-intellectual-freedom-center/authors-speak-out-on-censorship/

Backus, F., & Salvanto, A. (2022, April 6). Big majorities reject book bans - CBS news poll. CBS News. Retrieved September 25, 2022. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/book-bans-opinion-poll-2022-02-22/ . DOI: https://doi.org/10.3886/icpsr04092.v1

Banned & Challenged Books: Simon & Schuster. New Book Releases, Bestsellers, Author Info and more at Simon & Schuster. (n.d.). Retrieved September 25, 2022. https://www.simonandschuster.com/p/bannedbooksweek

Blake, M. (2022, July 27). A surprising list of recently banned books. Penguin Books UK. https://www.penguin.co.uk/articles/2022/05/surprising-books-that-have-been-recently-banned-2019

Chess, K. (2018, September 8). Why I hate censorship in ya fiction. Khristina Chess. https://www.khristinachess.com/blog/2018/9/8/why-i-hate-censorship-in-ya-fiction

Friedman, J., & Farid Johnson, N. (2022, September 19). Banned in the USA: The growing movement to censor books in schools. PEN America. Retrieved September 25, 2022. https://pen.org/report/banned-usa-growing-movement-to-censor-books-in-schools/

Frisaro, F. (2023, May 24). Amanda Gorman’s inauguration poem banned by Florida School. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/education/amanda-gormans-inauguration-poem-banned-by-florida-school

Gregory, J. (2022, September 9). 22 titles pulled from Missouri district shelves to comply with state law and more: Censorship roundup. School Library Journal. Retrieved October 2, 2022. https://www.slj.com/story/22-titles-pulled-from-missouri-district-shelves-to-comply-with-state-law-and-more-censorship-roundup

Jensen, K. (2022, August 4). A template for talking with school and Library Boards about book bans: Book censorship news, August 5, 2022. Book Riot. Retrieved September 25, 2022. https://bookriot.com/book-censorship-news-august-5-2022 . DOI: https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0173.0203

Jensen, K. (2022, August 25). States that have enacted book Ban laws: Book censorship news, August 26, 2022. Book Riot. Retrieved October 2, 2022. https://bookriot.com/states-that-have-enacted-book-ban-laws-2022/

Jensen, K. (2023, May 25). When do we move from advocacy to preparation?. Book Riot. https://bookriot.com/when-do-we-move-from-advocacy-to-preparation/

The Learning Network. (2022, February 18). What students are saying about banning books from school libraries. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/18/learning/students-book-bans.html

Lopez, S. (2023, May 8). The extreme new tactic in the crusade to ban books. Time. https://time.com/6277933/state-book-bans-publishers/

Magnusson, T. (n.d.). Book censorship database by Dr. Tasslyn Magnusson. EveryLibrary Institute. Retrieved September 25, 2022. https://www.everylibraryinstitute.org/book_censorship_database_magnusson

Miller, S. (2022). Intellectual Freedom Center Provides Support for Censorship Challenges. Council Chronicle, 32(1), 16–18. https://publicationsncte.org/content/journals/10.58680/cc202232050 . DOI: https://doi.org/10.58680/cc202232050

“Not recommended” reading: The books Hong Kong is purging from public libraries. (2023, May 26). Hong Kong Free Press. https://hongkongfp.com/2023/05/26/not-recommended-reading-the-books-hong-kong-is-purging-from-public-libraries . DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110966879.26a

op de Beeck, N. (2023, May 2). Turning a censorship controversy into a learning opportunity. PublishersWeekly.com. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/childrens/childrens-industry-news/article/92172-turning-a-censorship-controversy-into-a-learning-opportunity.html

Parker, C. (2023, July 25). Readers can now access books banned in their area for free with New App. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/banned-book-club-app-180982592/

Pendharkar, E. (2023, June 29). How students are reacting to book bans in their schools. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/how-students-are-reacting-to-book-bans-in-their-schools/2023/06

Price, R. (2022, September 19). The power of reading, or why I do what I do. Adventures in Censorship. https://adventuresincensorship.com/blog/2022/9/17/the-power-of-reading-or-why-i-do-what-i-do

Russell, B. Z. (2022, September 23). Panel: Book-banning push is coordinated, national effort. Idaho Press. Retrieved October 2, 2022. https://www.idahopress.com/news/local/panel-book-banning-push-is-coordinated-national-effort/article_cb6606aa-3b89-11ed-be6c-67820ea458a1.html

School Library Journal. (2023, May 25). Amanda Gorman’s Inaugural Poem Restricted in Florida District After One Parent Complains | Censorship News. https://www.slj.com/story/newsfeatures/Amanda-Gormans-Inaugural-Poem-Restricted-in-Florida-District-After-One-Parent-Complains-Censorship-News

REFERENCES FOR ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY #2

Beck, S., & Stevenson, A. (2018). Teaching contentious books regarding immigration: the case of Pancho Rabbit. Reading Teacher, 72(20), 265-273. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1739

Boyd, A. S., Rose, S. G., & Darragh, J. J. (2021). Shifting the conversation around teaching sensitive topics: Critical colleagueship in a teacher discourse community. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 65(2), 129-137. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.1186

Buehler, J. (2023). Voices of Young Adult Literature authors in the conversation about censorship. English Journal, 112(5), pp. 64-70. DOI: https://doi.org/10.58680/ej202332423

Collins, J. E. (2022). Policy solutions: Defying the gravitational pull of education politics. Phi Delta Kappan, 104(1), 62-63. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/00317217221123654

Dallacqua, A. (2022). “Let Me Just Close My Eyes”: Challenged and Banned Books, Claimed Identities, and Comics. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy,66(2), 134-138. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.1250

Dávila, D. The Tacit Censorship of Youth Literature: A Taxonomy of Text Selection Stances. Child Lit Educ 53, 376–391 (2022). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10583-022-09498-5

Garnar, M., Lechtenberg, K., & Vibbert, C. (2020). School Librarians and the Intellectual Freedom Manual. Knowledge Quest, 49(1), 34–38.

Goodman, C. L. (Ed.) (2022). IDRA Newsletter. Volume 49, No. 2. Intercultural Development Research Association.

Greathouse, P., Eisenbach, B., & Kaywell, J. (2017). Supporting Students’ Right to Read in the Secondary Classroom: Authors of Young Adult Literature Share Advice for Pre-Service Teachers. SRATE Journal, 26(2), 17–24.

Hartsfield, D. E., & Kimmel, S. C. (2020) Exploring educators figured worlds of controversial literature and adolescent readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 63(4), 443-451. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.989

Hlwyak, S., Ed. (2021, April). State of America's libraries 2021: Special report: Covid-19. American Library Association. https://www.ala.org/news/sites/ala.org.news/files/content/State-of-Americas-Libraries-Report-2021-4-21.pdf

Ivey, G., & Johnston, P. (2018). Engaging disturbing books. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62(2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.883

Leland, C. H., & Bangert, S. E. (2019). Encouraging activism through art: Preservice teachers challenge censorship. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 68(1), 162-182. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2381336919870272

Lycke, K., & Lucey, T. (2018). The Messages We Miss: Banned Books, Censored Texts, and Citizenship. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 9(1), 1–26. 3

Matthews, C. (2018). Sexuality. Brock Education: A Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 27(2), 68-74.

Mehan, K., & Friedman, J. (2023). Banned in the USA: State laws supercharge book suppression in schools. PEN America. https://pen.org/report/banned-in-the-usa-state-laws-supercharge-book-suppression-in-schools/

Metzgar, M., & McGowan, M. J. (2022). Viewpoint diversity at UNC Charlotte. Acta Educationis Generalis, 12(3), 1-12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2478/atd-2022-0020

Moffet, J. (1988). Storm in the Mountains: A Case Study of Censorship, Conflict, and Consciousness. Southern Illinois University.

Page, M. L. (2017). Teaching in the cracks: Using familiar pedagogy to advance LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 60(6), 644-685. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.616

Pekoll, K. (2020). Managing censorship challenges beyond books. Knowledge Quest, 49(1), 28-33.

PEN America. (2022, April). Banned in the USA: Rising school book bans threaten free expression and students’ First Amendment Rights (April 2022). https://pen.org/banned-in-the-usa/#what

PEN America. (2022, Sept. 19). New report: 2,500+ book bans across 32 states during the 2021-22 school year. https://pen.org/press-release/new-report-2500-book-bans-across-32-states-during-2021-22-school-year/

Pérez, A. H. (2022). Defeating the censor within: How to hold your stand for youth access to literature in the face of school book bans. Knowledge Quest, 50(5), 34-39.

Rumberger, A. (2019). The elementary school library: Tensions between access and censorship. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 20(4), 409–421. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949119888491

SLJ Staff. (2023, April 20). New PEN America Report Shows Increase in Book Bans Driven by State Legislation. School Library Journal. https://www.slj.com/story/censorship/New-PEN-America-Report-Shows-Increase-in-Book-Bans-Driven-by-State-Legislation

Steele, J. E. (2020). A History of Censorship in the United States. Journal of Intellectual Freedom & Privacy, 5(1), 6-19. https://www.ala.org/news/sites/ala.org.news/files/content/State-of-Americas-Libraries-Report-2021-4-21.pdf

Sulzer, M. A., & Thein, A. H. (2016). Reconsidering the hypothetical adolescent in evaluating and teaching young adult literature. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 60(2), 163-171. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.556

Vissing, Y., & Juchniewicz, M. (2023). Children’s book banning, censorship and human rights. In J. Zajda, P. Hallam, & J. Whitehouse (Eds.), Globalisation, values education and teaching democracy, vol 35 (pp. 181-201). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15896-4_12

Walter, B., & Boyd, A. S. (2019). A threat or just a book? Analyzing responses to Thirteen Reasons Why in a discourse community. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62(6), 615-623. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.939

Woo, A., Lee, S., Tuma, A. P., Kaufman, J. H., Lawrence, R. A., & Reed, N. (2023). Walking on Eggshells--Teachers' Responses to Classroom Limitations on Race-or Gender-Related Topics: Findings from the 2022 American Instructional Resources Survey. Research Report. RR-A134-16. RAND Corporation. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7249/rra134-16

REFERENCES NOT INCLUDED IN THE ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHIES

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3).

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2022, October 20). Hydra. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hydra-Greek-mythology

Foster, M. V. (2022, August 23). NPS teacher resigns from district after sharing QR code for library access with classroom. FOX 25, Oklahoma (KOKH). https://okcfox.com/news/local/norman-public-schools-nps-norman-high-school-teacher-summer-boismeir-house-bill-1775-hb1775-american-civil-liberties-union-aclu-first-amendment-critical-race-theories-crt-book-ban-oklahoma-state-board-of-education-race-sex-discrimination?fbclid=IwAR0WiSTlBqucyBFZLzDIbKqrmRJ9PMOG-wKbGLihujHOBiAzidJn9I7F_Ho

Hill, J. A. (2023). Legitimate state interest of educational censorship: the chilling effect of Oklahoma House Bill 1775. Oklahoma Law Review, 75(2), 385-408.

Interactive chart. Ad Fontes Media. (2023, July 8). https://adfontesmedia.com/interactive-media-bias-chart/

KOKH Staff. (2023, March 21). 'What did I do?' OSDE applies to revoke certificate of ex-Norman teacher Summer Boismier. FOX 25, Oklahoma (KOKH). https://okcfox.com/news/local/summer-boismier-teaching-certificate-revoked-norman-oklahoma-ryan-walters-books-unbanned-qr-code-state-department-education-brooklyn-public-library-critical-race-theory-gender-queer-

Media Bias Chart. AllSides. (2023, June 21). https://www.allsides.com/media-bias/media-bias-chart

Oklahoma State Department of Education. (2016). Oklahoma academic standards for English language arts. https://sde.ok.gov/sites/ok.gov.sde/files/documents/files/OAS-ELA-Final%20Version_0.pdf

PEN America. (2022, August 23). For the first time, Oklahoma education officials punish two school districts for violating gag order on teaching race and gender. [Press Release]. PEN America. https://pen.org/press-release/for-first-time-oklahoma-education-officials-punish-two-school-districts-for-violating-gag-order-on-teaching-race-and-gender/

Penharkar, E. (2022, August 2). Two Okla. districts get downgraded Accreditations for violating state’s anti-CRT Law. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/two-okla-districts-get-downgraded-accreditations-for-violating-states-anti-crt-law/2022/08

Smith, J. C. (2023, June 22). School officials ‘failed to prove’ teacher violated law by helping students get books, prosecutor says. USA Today Network. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2023/06/22/no-proof-teacher-violated-oklahoma-book-law-prosecutor/70347891007/

Suares, W. (2022, August24). ‘I am a walking HB1775 violation’: Former Norman teacher discusses book ban controversy. FOX 25 Oklahoma (KOKH). https://okcfox.com/news/local/summer-boismier-norman-public-schools-critical-race-theory-brooklyn-public-library-qr-code-house-bill-1775-oklahoma-teacher-resigned-education-books?fbclid=IwAR2Pz72tTGDJbZrEeGEm6LYaaJb17ojMMTrztDxU_6uBvZcDD7cVIJvf5yw

Stafford, W. (2022, July 28). Two Oklahoma school districts punished for violating CRT ban. FOX 25, Oklahoma (KOKH). https://okcfox.com/news/local/2-ok-school-district-punished-for-violating-crt-ban-tulsa-public-schools-and-mustang-public-schools-accreditation-with-warning-house-bill-1775-accreditation-with-warning-accreditation-with-deficiencies

Taylor, J., & Fife, A. (2023, August 3). After a state law banning some lessons on race, Oklahoma teachers tread lightly on the Tulsa Race Massacre. The Frontier. https://www.readfrontier.org/stories/after-a-state-law-banning-some-lessons-on-race-oklahoma-teachers-tread-lightly-on-the-tulsa-race-massacre/?fbclid=IwAR1PBzCAnjyI59RRArRTNudvmJydz5hYvZghABDSLjYPoq0tmcDsYRj8Lqc . DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74679-7_3

Tolin, L. (2023, January). Oklahoma teacher is still fighting book bans, now from Brooklyn.

Waters, M. B. (2018, December 31). Rethink ELA #010: Fostering student-led discussions with the TQE method. reThink ELA. https://www.rethinkela.com/2018/12/rethink-ela-010-fostering-student-led-discussions-with-the-tqe-method/

Woo, A., Lee, S., Tuma, A. P., Kaufman, J. H., Lawrence, R. A., & Reed, N. (2023). Walking on Eggshells—Teachers’ Responses to Classroom Limitations on Race-or Gender-Related Topics. Rand American Educational Panels. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA100/RRA134-16/RAND_RRA134-16.pdf . DOI: https://doi.org/10.7249/rra134-16

Copyright (c) 2023 Michelle Boyd Waters, Shelly K. Unsicker-Durham

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License .

Current Issue

Information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Developed By

Teaching in the Face of Book Bans

- Posted November 30, 2023

- By Elizabeth M. Ross

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Education Policy

- Moral, Civic, and Ethical Education

- Teachers and Teaching

In the second part of our series on helping educators navigate book challenges , Timothy Patrick McCarthy , historian and lecturer on education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, encourages teachers to resist censorship efforts by taking control of their own curriculum in creative ways. In an interview, he shares historical perspective and advice for educators.

Why, from your disciplinary perspective, are book bans harmful?

As a historian, I know that people who ban books are never on the right side of history. During two and a half centuries of slavery in the United States, white elites routinely enacted laws prohibiting enslaved people from learning to read and write. The denial of literacy — and education, more broadly — was one of the many racist barriers to liberation for Black people. During the rise of fascism in Europe in the 1930s, book banners continued these kinds of repressive practices in new and dramatic ways. Students in the German Student Union and other Nazi conspirators staged public book burnings, where tens of thousands of books by Jewish, gay, and other dissident authors were destroyed. One of the most iconic photographs from that time depicts a book burning at the Institute for Sexual Research in Berlin, where Magnus Hirschfeld and other scholars conducted groundbreaking studies on human sexuality. These are just two examples of the long history of knowledge destruction, which continues today in the accelerating and intensifying efforts to ban books and control curriculum throughout the United States. As the fugitive-turned-abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote of learning to read in his 1845 autobiography , “From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom.” And that’s the point: Book banners (and burners) understand the threat that freedom and education for the oppressed poses to their own power and privilege, which is why they are still trying to deny these things by any means necessary.

What advice can you offer educators about how to navigate or challenge book bans and other efforts to censor materials in schools and libraries?

These are treacherous times in education. We are living in an age of bullies where schools are once again in the crosshairs of the culture wars. In this context, to fight the forces of bigotry and censorship is as risky as it is urgent. For educators who can and want to take these risks, I would recommend several strategies:

- Practice what I call “protest pedagogy,” resisting attempts to ban books by taking control of your curriculum in creative ways. I know this is easier said than done, especially in public schools that are subjected to restrictive state standards and reactionary public pressures. But it can be done . In this digital age, encourage your students to do outside and online research, discover alternative sources and archives, and choose their own topics for exploration and analysis. Give them direction verbally and virtually — as opposed to, say, in writing and in class — and allow them to incorporate creative forms (art, videos, podcasts, social media) into the work they submit for evaluation. Introduce them to primary documents and public libraries, inspire them to interview their elders and share their own stories, and interrogate the old texts in new ways. Organize DonorsChoose or GoFundMe campaigns so your friends can buy banned books for your classroom libraries — or better yet, get your friendly publishers to donate them. There are many ways to resist these unjust forces and policies by teaching around them.

- Build your collective power by connecting with the kindred people who are already doing this work all over the country. There are networks of students, teachers, and parents in some of the states with the most draconian policies and practices. (Florida, Texas, Tennessee.) There are also many of us in colleges and universities — as well as libraries and professional associations — who stand ready to support whatever efforts you are organizing in your schools and communities.

- Run for school board! In recent years, the forces fueling book bans and other attempts at curricular control have been successful in getting their representatives elected to school boards across the country. This gives them more power to censor what people teach and learn. Those of us who value free speech and critical thinking, who honor diversity and the right to an equitable education, who embrace the search for historical and scientific truth — we need to run for school board, too. And if we decide not to run, let’s find ways to support (and vote for) good candidates who do. We cannot cede any more power in the field of education to people who are persistently devoted to the nation’s miseducation.

"We don’t need to protect young people from the truth. We need to encourage them to be critical, curious, and compassionate."

What advice do you have about how and when to teach controversial topics and books in the classroom that have been challenged or banned elsewhere?

As a general rule, topics and books get the reputation for being “controversial” because they contain truths that make people uncomfortable. One need only look at the most “popular” justifications for book bans: because they center characters who are Black, Brown, and queer and content that deals with LGBTQ+ or race matters. But it is never too early to teach people the truth. If society teaches our young people to be racist surely our schools can teach them the long history of racism and anti-racism in the United States. When it comes to “age appropriate” texts, I am inclined to leave that to the writers who write the books, publishers who publish them, teachers who teach them, the students who read them — and the scholars who have spent their careers studying various aspects of social identity formation and child development. The loud cries of “liberty” from people who want to censor free speech and deny the right to education ring hollow. We don’t need to protect young people from the truth. We need to encourage them to be critical, curious, and compassionate. We need to free them — and all of us — from the forces of fear, prejudice, and willful ignorance that are currently tearing the nation apart.

What additional resources can you share with educators from your own or others’ work?

In different ways, two of my own books — The Radical Reader: A Documentary History of the American Radical Tradition and Reckoning with History: Unfinished Stories of American Freedom — challenge the “master narratives” to center a more inclusive history of the United States. I would also recommend The 1619 Project , History UnErased , Zinn Education Project , Facing History and Ourselves , and Making Gay History , all of which provide rich and diverse resources for teachers and learners interested in a more honest engagement with the American past and its connection to our collective present and future.

Extra reading:

- Brave Awakenings in an Age of Bullies

- As Luck Would Have It

Navigating Book Bans

A guide for educators as efforts intensify to censor books

- Families and Community

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Book Bans and the Librarians Who Won't Be Hushed

How educators are speaking out in response to recent — and increasing — book bans

Equality or Equity?

The official publication of the NAACP

Book Bans: An Act of Policy Violence Promoting Anti-Blackness

By Dr. Phelton Moss

Book bans represent acts of policy violence that further codify anti-blackness in the DNA of America.

Two weeks ago, the NAACP filed a lawsuit in Pickens County, South Carolina, alleging their most recent ban of Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi's book " Stamped: Racism, Anti-Racism, and You " from every school district in South Carolina is unconstitutional in that it violates the student's first amendment rights and is politically motivated. Unfortunately, the all-white Pickens County School Board is among a growing list of violent actors who must be stopped. They deliberately censor what literary works kids can and cannot read — and in many cases, having not read the books themselves before voting to ban them. What is more violent, as evidenced by the books they are banning, they choose to censor the teaching of the factually accurate history of Black people. These violent acts are rooted in an un-yielding legacy of racism, prejudice, oppression, and anti-blackness.

As a young boy growing up in rural Mississippi, I recall my aunt filling my bookshelves with books that told the factually accurate history of Black people — often signing books gifted to me for holidays and special occasions such as Kwanzaa and my birthday with the charged phrase, "Know Thy Self." These books often came with money — "…when you finish, I have $20 for you." Today, while they no longer include $20, these acts have extended to a tradition of passing books that tell and affirm the factually accurate history of Black people between us. This practice would not have been required had I attended a school that sought to teach the honesty and factually detailed account of Black people. Today that remains the reality for many Black children. And to make matters worse, far too many Black children whose families have been impacted by the history of racism and oppression won't be able to purchase books for their children — much less incentivize children to read their history as my aunt did me.

The tradition of passing books with my aunt was (and remains today) an act of love and rebellion — more profoundly, it was an act of Black liberation. My aunt was deeply critical of the lack of teaching of the factually accurate history of Black people. She was most struck by the fact that my schools intentionally shared the narratives of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. but failed to offer the narratives of Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey. Thus, choosing to reject the complete, factually accurate account of Black people's history.

Books bans have increasingly become the policy tool of anti-black policy leaders who systematically perpetuate intolerance and ignorance. These attempts systematically and disproportionately impact Black youth who would benefit from the literary work's interrogation of society as they shape their understanding of their people's history. These violent actors know the cascading effect such works would have on all youth's ability to challenge, interrogate, and ask for a better America. For example, many school districts nationwide have banned " The Bluest Eye " by Toni Morrison. Morrison's work has been integral in shaping classroom conversations across America on race and prejudice. As such, these attempts to censor literature and silence Black writers are politically motivated and profoundly un-American.

This pedagogical violence, caused by actors with no teaching experience in schools, has been painstakingly done to keep the factually accurate history of Black people out of the hands of Black children. And, while in many classrooms across America, teachers have chosen not to teach the factually accurate history of America, it is now being codified through acts of policy violence today — namely, book bans! As these acts of policy violence continue to sprout up as part of intentional acts of anti-blackness in the halls of state legislatures, local school boards meetings, and even Congress, with the recent passage of the Parents Bill of Rights , civil rights leaders must fight against the attack on Black students to keep them from learning the factually accurate history of Black people in America.

For years, this country has successfully worked to pass violent laws to maintain a permanent caste system to include an illiterate fraction of Black people through the passage of Jim Crow laws and literacy tests to ensure Black people could never pick up a book — much less read it to know their history. Today's book bans join the growing list of anti-black violence by a dwindling majority, insistent on keeping Black children from learning the factually accurate history of racism, prejudice, and oppression in America.

We must fight bans on books that teach the honest, factually accurate history of Black people in America most dramatically — from litigation such as the Pickens County, South Carolina case to challenging lawmakers at state capitols and school board members in local communities through both policy debates and electoral politics. As such, the NAACP is committed to preserving, defending, and protecting the factually accurate history of Black people in this country. Especially that of those who, for 400 years, through violent policy acts such as enslavement, forced migration, redlining, sharecropping, gentrification, gerrymandering, segregation, etc., have been relegated to simply existing through white supremacy. As the NAACP works to dismantle these and other acts of policy violence, we ask that you join us in this fight. The NAACP will continue to support local, state, and national efforts to fight back against book bans. Let us know how we can help you fight book bans in your local community!

- Education Innovation

Help Us Meet Our Midnight Deadline!

From police reform to voting rights, and our democracy itself – everything is on the line. We need to raise $250,000 to support our work advocating, agitating, and litigating for civil rights across the nation. Donate today and your gift will be matched, doubling your impact.

A War Beyond Words: How book bans perpetuate the underrepresentation of vulnerable communities

In this reported piece, a student examines the impact of book bans, harms of censorship, and highlights solutions from experts.

In a 2021 op-ed for the Lexington Herald-Leader, Daksha Pillai , then a junior at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, wrote about the importance of young people deciding for themselves what books they read, rather than their parents. Now, efforts to ban books from school and public libraries alike are happening across the country : 2023 data from American Library Association spanning January 1 to August 31 showed a 20% increase in book banning and challenging attempts from 2022’s reporting period .

PEN America issued a report on the most banned books of the 2022-2023 school year. Of books banned during the 2022-2023 school year, the report outlined that

“30 percent include characters of color or discuss race and racism” and “30 percent LGBTQ+ characters or themes.” PEN America also notes that there is “disproportionate targeting” of books for and by individuals with underrepresented identities, including, the report said, people of color, LGBTQ+ people, and people with disabilities.

In addition to being a form of censorship , targeting of books that involve marginalized communities, or are by marginalized authors, is damaging.

“With marginalized students, especially, I feel like we've spent most of our lives engaging with content that doesn't reflect us,” Pillai told The New Edu. “And so for us, it's a choice when we engage with something that does.” Students who may not hold marginalized identities might spend their entire life reading content that reflects their world. “I think everybody deserves to have that choice, no matter their identity,” Pillai said.

When the ability to choose what one reads from a diverse selection of topics, themes, and ideas readers is restricted, social issues have less potential to be addressed , and less identities, cultures, and experiences are represented and celebrated.

Analyzing Damages: Representation of Marginalized Communities and Impact on Vulnerable Students

According to a story from PBS , most books that have been challenged or banned focus on elements of race, gender identity, sexuality, and history. Based on a report by the American Library Association's Office of Intellectual Freedom, in 2022, Kentucky had 22 legislative attempts to restrict access to books. 70 titles were challenged in those attempts, and Gender Queer: A Memoir has been the most challenged title. (In fact, according to the ALA, it was the most challenged book of 2022 .) The book was written by author Maia Kobabe , and is a graphic novel following eir experiences finding eir identity.

The organization Stand With Trans , a nonprofit that supports trans youth and their loved ones, mentioned in an article reviewing the book that “all eir stories are heartfelt, deeply honest, raw and personal, yet also told with good humor and Maia’s wonderful graphic art.”

Prejudice toward people of different identities persists as an undertone to these bills that target works that showcase inclusivity. Most notably, Kentucky Senate Bill 5 requires school boards to adopt a complaint resolution policy for parents challenging materials they deem harmful to minors, and has been criticized for being a “book-banning” bill . In the passing of this bill, legislators took strong stands on Gender Queer . When the bill was heard in the Senate Education Committee in February, the only book Senator Lindsey Tichenor cited as an example of “offensive material” was Gender Queer: A Memoir, according to reporting by the Kentucky Lantern. Senate Bill 5 has been enacted as of July 1, 2023.

Students and advocates alike have raised concerns about censorship leading to students having a lack of understanding of different people and ideas they are not actively exposed to, or not seeing themselves represented.

“Banning books silences the voices of marginalized communities,” Jennie Samons , the Lexington Public Library Teen Librarian at the Northside Branch , told The New Edu. “ Youth who are not exposed to lived experiences similar to their own can feel isolated, detached, and lonely, so exposure to these books and materials is essential to their mental health and well-being.”

That is echoed by Tala Saad, a freshman at Vanderbilt University who wrote a research paper about censorship. “Being exposed and being able to consume content that exposes me to other people's identities and other people's stories gives a basic sense of empathy in a way that you can't get without hearing from stories that expose you to these kinds of topics and the lives that other people live,” said Saad.

Furthermore, it also matters who sees themselves in materials, according to experts. “If you are trying to ban books with Black characters, or LGBTQ characters, you're kind of saying to kids who fit into those categories that your stories are not important. Your stories don't belong in the library in the schools; I don't want my kids to know about people like you,” Dr. Shannon M. Oltmann , an Associate Professor in the School of Information Science, College of Communication and Information at the University of Kentucky who teaches library science, told The New Edu.

Oltmann also speaks to personal experience. ”If I just had a few books that had queer characters, characters who are like me, that would have made a world of difference to me growing up,” Oltmann added.”It would have helped me understand myself, explain myself to my family and my friends, and made things a lot easier for my coming out process and my growing up.”

Fortunately, there have been cases where requests to remove books from school libraries have been unsuccessful. In September 2022, a Jefferson County Public Schools decision-making group opposed the banning of Gender Queer: A Memoir from the libraries of Liberty High School and the Phoenix School of Discovery, as reported by The Courier Journal. They justified this dissent through substantial and objective proof of the book's “serious literary value.” The decision was a triumph for queer students who empathize with the book and all those who appreciate its significance.

In addition, Senator Karen Berg made a statement regarding the importance of access to different kinds of stories when Senate Bill 5 was heard in the Senate Education Committee. When evaluating a list of books deemed problematic for children, including one in which a girl was raped by her father, Berg stated that though Senator Tichenor doesn’t believe her child needs to see that book, there is likely another child in the state who has had that experience, and “that book may be a lifeline.”

Beyond the Challenges: Efforts Against Book Bans

Though the war of censorship brews beyond words, many students and advocates are preparing for battle. In the fall of 2022, during Banned Books Week, the Lexington Public Library in Kentucky organized its first banned book club meeting for teens, a means to help thwart censorship nationate, according to Samons, who hosts the Teen Banned Books Club.

“I wanted youth to feel empowered to access information, and to be able to have meaningful conversations about the books that are being challenged, many of which center LGBTQ voices, or are written by Black or Latino authors,” explained Samons. “Our youth deal with these topics on a daily basis, and it is vital for them to be able to access these stories that are being censored.”

Beyond Kentucky, the Brooklyn Public Library runs the Books Unbanned initiative, which includes offering a free National Teen eCard to young people ages 13-21 throughout the United States. BPL began an Intellectual Freedom Teen Council , which virtually gathers every month to discuss book challenges, connect with teen activists throughout the country, strategize methods of support, and more.

There are a handful of other ways teens can be engaged in making a difference when it comes to book challenges. “We're seeing that most of the power for both ends is being handed to school boards and higher school administration,” Tala Saad pointed out. “If books are trying to be banned in your county, go to a school board meeting [and] speak on that.”

Samons suggested that teens can fight censorship by both organizing their own reading groups and learning how local government functions. That way, young people have a better idea of who to contact in order to make change happen.

Oltmann pointed to the importance of connecting with educators on these issues. “This sounds really simple, but you can just thank your teachers and librarians for the work that they're doing,” Oltman said. “A lot of them are facing a lot of criticism and a lot of challenges these days. And it's kind of hard to keep doing your job under those conditions.”

Books have minds of their own. Stories can be told, lessons can be taught, art can be expressed, and souls can be reached. Books can also give a voice to the most vulnerable. Engaging with all different kinds of media, developing oneself intellectually, and enriching your worldview is “essentially how you build a world that you do want to live in,” Daksha Pillai added. Carlie Hall contributed reporting.

Introduction

Mi tincidunt elit, id quisque ligula ac diam, amet. Vel etiam suspendisse morbi eleifend faucibus eget vestibulum felis. Dictum quis montes, sit sit. Tellus aliquam enim urna, etiam. Mauris posuere vulputate arcu amet, vitae nisi, tellus tincidunt. At feugiat sapien varius id.

Eget quis mi enim, leo lacinia pharetra, semper. Eget in volutpat mollis at volutpat lectus velit, sed auctor. Porttitor fames arcu quis fusce augue enim. Quis at habitant diam at. Suscipit tristique risus, at donec. In turpis vel et quam imperdiet. Ipsum molestie aliquet sodales id est ac volutpat.

ondimentum enim dignissim adipiscing faucibus consequat, urna. Viverra purus et erat auctor aliquam. Risus, volutpat vulputate posuere purus sit congue convallis aliquet. Arcu id augue ut feugiat donec porttitor neque. Mauris, neque

Dolor enim eu tortor urna sed duis nulla. Aliquam vestibulum, nulla odio nisl vitae. In aliquet pellente

Elit nisi in eleifend sed nisi. Pulvinar at orci, proin imperdiet commodo consectetur convallis risus. Sed condimentum enim dignissim adipiscing faucibus consequat, urna. Viverra purus et erat auctor aliquam. Risus, volutpat vulputate posuere purus sit congue convallis aliquet. Arcu id augue ut feugiat donec porttitor neque. Mauris, neque ultricies eu vestibulum, bibendum quam lorem id. Dolor lacus, eget nunc lectus in tellus, pharetra, porttitor.

"Ipsum sit mattis nulla quam nulla. Gravida id gravida ac enim mauris id. Non pellentesque congue eget consectetur turpis. Sapien, dictum molestie sem tempor. Diam elit, orci, tincidunt aenean tempus."

Tristique odio senectus nam posuere ornare leo metus, ultricies. Blandit duis ultricies vulputate morbi feugiat cras placerat elit. Aliquam tellus lorem sed ac. Montes, sed mattis pellentesque suscipit accumsan. Cursus viverra aenean magna risus elementum faucibus molestie pellentesque. Arcu ultricies sed mauris vestibulum.

Morbi sed imperdiet in ipsum, adipiscing elit dui lectus. Tellus id scelerisque est ultricies ultricies. Duis est sit sed leo nisl, blandit elit sagittis. Quisque tristique consequat quam sed. Nisl at scelerisque amet nulla purus habitasse.

Nunc sed faucibus bibendum feugiat sed interdum. Ipsum egestas condimentum mi massa. In tincidunt pharetra consectetur sed duis facilisis metus. Etiam egestas in nec sed et. Quis lobortis at sit dictum eget nibh tortor commodo cursus.

Odio felis sagittis, morbi feugiat tortor vitae feugiat fusce aliquet. Nam elementum urna nisi aliquet erat dolor enim. Ornare id morbi eget ipsum. Aliquam senectus neque ut id eget consectetur dictum. Donec posuere pharetra odio consequat scelerisque et, nunc tortor. Nulla adipiscing erat a erat. Condimentum lorem posuere gravida enim posuere cursus diam.

This is a block quote

The rich text element allows you to create and format headings, paragraphs, blockquotes, images, and video all in one place instead of having to add and format them individually. Just double-click and easily create content.

This is a link inside of a rich text

similar articles to check out

Kentucky Student Journalists Need New Voices Legislation

We Should Continue Supporting Student Press Freedom

.jpg)

Youth Voice, Authorship, & Democracy: Unpacking Media Literacy with Dr. Renee Hobbs

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

My Young Mind Was Disturbed by a Book. It Changed My Life.

By Viet Thanh Nguyen

Mr. Nguyen is the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Sympathizer” and the children’s book “Chicken of the Sea,” written with his then 5-year-old son, Ellison.

When I was 12 or 13 years old, I was not prepared for the racism, the brutality or the sexual assault in Larry Heinemann’s 1977 novel, “Close Quarters.”

Mr. Heinemann, a combat veteran of the war in Vietnam, wrote about a nice, average American man who goes to war and becomes a remorseless killer. In the book’s climax, the protagonist and other nice, average American soldiers gang-rape a Vietnamese prostitute they call Claymore Face.

As a Vietnamese American teenager, it was horrifying for me to realize that this was how some Americans saw Vietnamese people — and therefore me. I returned the book to the library, hating both it and Mr. Heinemann.

Here’s what I didn’t do: I didn’t complain to the library or petition the librarians to take the book off the shelves. Nor did my parents. It didn’t cross my mind that we should ban “Close Quarters” or any of the many other books, movies and TV shows in which racist and sexist depictions of Vietnamese and other Asian people appear.

Instead, years later, I wrote my own novel about the same war, “The Sympathizer.”

While working on it, I reread “Close Quarters.” That’s when I realized I’d misconstrued Mr. Heinemann’s intentions. He wasn’t endorsing what he depicted. He wanted to show that war brutalized soldiers, as well as the civilians caught in their path. The novel was a damning indictment of American warfare and the racist attitudes held by some nice, average Americans that led to slaughter and rape. Mr. Heinemann revealed America’s heart of darkness. He didn’t offer readers the comfort of a way out by editorializing or sentimentalizing or humanizing Vietnamese people, because in the mind of the book’s narrator and his fellow soldiers, the Vietnamese were not human.

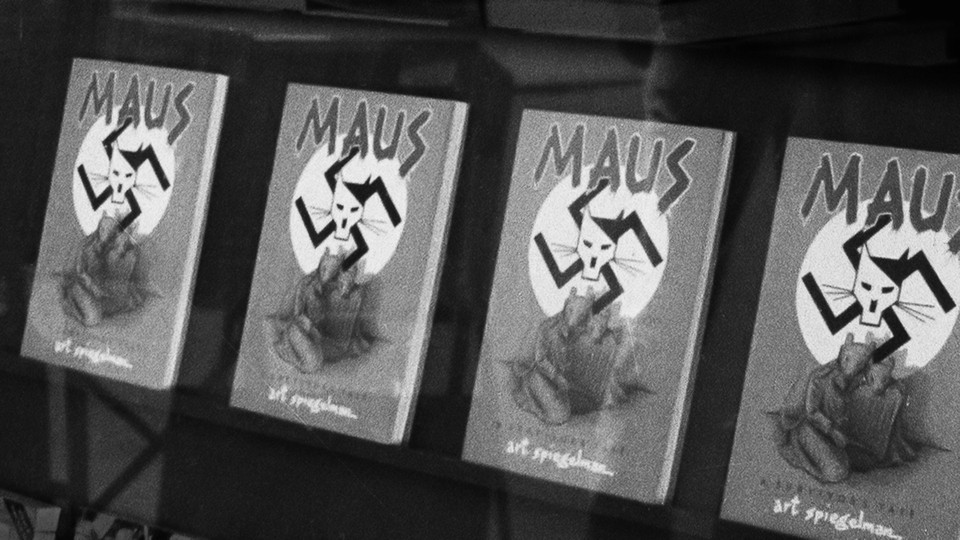

In the United States, the battle over books is heating up, with some politicians and parents demanding the removal of certain books from libraries and school curriculums. Just in the last week, we saw reports of a Tennessee school board that voted to ban Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel about the Holocaust, “Maus,” from classrooms, and a mayor in Mississippi who is withholding $110,000 in funding from his city’s library until it removes books depicting L.G.B.T.Q. people. Those seeking to ban books argue that these stories and ideas can be dangerous to young minds — like mine, I suppose, when I picked up Mr. Heinemann’s novel.

Books can indeed be dangerous. Until “Close Quarters,” I believed stories had the power to save me. That novel taught me that stories also had the power to destroy me. I was driven to become a writer because of the complex power of stories. They are not inert tools of pedagogy. They are mind-changing, world-changing.

But those who seek to ban books are wrong no matter how dangerous books can be. Books are inseparable from ideas, and this is really what is at stake: the struggle over what a child, a reader and a society are allowed to think, to know and to question. A book can open doors and show the possibility of new experiences, even new identities and futures.

Book banning doesn’t fit neatly into the rubrics of left and right politics. Mark Twain’s “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” has been banned at various points because of Twain’s prolific use of a racial slur, among other things. Toni Morrison’s “Beloved” has been banned before and is being threatened again — in one case after a mother complained that the book gave her son nightmares . To be sure, “Beloved” is an upsetting novel. It depicts infanticide, rape, bestiality, torture and lynching. But coming amid a movement to oppose critical race theory — or rather a caricature of critical race theory — it seems clear that the latest attempts to suppress this masterpiece of American literature are less about its graphic depictions of atrocity than about the book’s insistence that we confront the brutality of slavery.

Here’s the thing: If we oppose banning some books, we should oppose banning any book. If our society isn’t strong enough to withstand the weight of difficult or challenging — and even hateful or problematic — ideas, then something must be fixed in our society. Banning books is a shortcut that sends us to the wrong destination.

As Ray Bradbury depicted in “Fahrenheit 451,” another book often targeted by book banners, book burning is meant to stop people from thinking, which makes them easier to govern, to control and ultimately to lead into war. And once a society acquiesces to burning books, it tends to soon see the need to burn the people who love books.

And loving books is really the point — not reading them to educate oneself or become more conscious or politically active (which can be extra benefits). I could recommend “Fahrenheit 451” because of its edifying political and ethical dimensions or argue that reading this novel is good for you, but that really misses the point. The book gets us to care about politics and ethics by making us care about a man who burns books for a living and who has a life-changing crisis about his awful work. That man and his realization could be any of us.

It’s not only books that depict horror, war or totalitarianism that worry would-be book banners. They sometimes see danger in empathy. This appeared to be the fear that led a Texas school district to cancel the appearance of the graphic novelist Jerry Craft and pull his books temporarily from library shelves last fall. In Mr. Craft’s Newbery Medal-winning book, “ New Kid ,” and its sequel, Black middle-schoolers navigate social and academic life at a private school where there are very few students of color. “The books don’t come out and say we want white children to feel like oppressors, but that is absolutely what they will do,” the parent who started the petition to cancel Mr. Craft’s event said . (Mr. Craft’s invitation for a virtual visit was rescheduled and his books were reinstated soon after.)

Mr. Craft’s protagonist in “New Kid” is a sweet, shy, comics-loving kid. And it’s his relatability that makes him seem so dangerous to some white parents. The historian and law professor Annette Gordon-Reed argued on Twitter that parents who object to books such as “New Kid” “don’t want their kids to empathize with the black characters. They know their kids will do this instinctively. They don’t want to give them the opportunity to do that.” The historian Kevin Kruse went a step further, tweeting , “If you’re worried your children will read a book and have no choice but to identify with the villains in it, well … maybe that’s something you need to work through on your own.”

Those who ban books seem to want to circumscribe empathy, reserving it for a limited circle closer to the kind of people they perceive themselves to be. Against this narrowing of empathy, I believe in the possibility and necessity of expanding empathy — and the essential role that books such as “New Kid” play in that. If it’s possible to hate and fear those we have never met, then it’s possible to love those we have never met. Both options, hate and love, have political consequences, which is why some seek to expand our access to books and others to limit them.

These dilemmas aren’t just political; they’re also deeply personal and intimate. Now, as a father of a precocious 8-year-old reader, I have to think about what books I bring into our home. My son loves Hergé’s Tintin comic books, which I introduced him to because I loved them as a child. I didn’t notice Hergé’s racist and colonialist attitudes then, from the paternalistic depiction of Tintin’s Chinese friend Chang in “The Blue Lotus” to the Native American warriors wearing headdresses and wielding tomahawks in the 1930s of “Tintin in America.” Even if I had noticed, I had no one with whom I could talk about these books. My son does. We enjoy the adventures of the boy reporter and his fluffy white dog together, but as we read, I point out the books’ racism against most nonwhite characters, and particularly their atrocious depictions of Black Africans. Would it be better that he not see these images, or is it better that he does?

I err on the side of the latter and try to model what I think our libraries and schools should be doing. I make sure he has access to many other stories of the peoples that Hergé misrepresented, and I offer context with our discussions. These are not always easy conversations. And perhaps that’s the real reason some people want to ban books that raise complicated issues: They implicate and discomfort the adults, not the children. By banning books, we also ban difficult dialogues and disagreements, which children are perfectly capable of having and which are crucial to a democracy. I have told him that he was born in the United States because of a complicated history of French colonialism and American warfare that brought his grandparents and parents to this country. Perhaps we will eventually have less war, less racism, less exploitation if our children can learn how to talk about these things.

For these conversations to be robust, children have to be interested enough to want to pick up the book in the first place. Children’s literature is increasingly diverse and many books now raise these issues, but some of them are hopelessly ruined by good intentions. I don’t find piousness and pedagogy interesting in art, and neither do children. Hergé’s work is deeply flawed, and yet riveting narratively and aesthetically. I have forgotten all the well-intentioned, moralistic children’s literature that I have read, but I haven’t forgotten Hergé.

Books should not be consumed as good for us, like the spinach and cabbage my son pushes to the side of his plate. “I like reading short stories,” a reader once said to me. “They’re like potato chips. I can’t stop with one.” That’s the attitude to have. I want readers to crave books as if they were a delicious, unhealthy treat, like the chili-lime chips my son gets after he eats his carrots and cucumbers.

Read “Fahrenheit 451” because its gripping story will keep you up late, even if you have an early morning. Read “Beloved,” “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” “Close Quarters” and “The Adventures of Tintin” because they are indelible, sometimes uncomfortable and always compelling.

We should value that magnetic quality. To compete with video games, streaming video and social media, books must be thrilling, addictive, thorny and dangerous. If those qualities sometimes get books banned, it’s worth noting that sometimes banning a book can increase its sales .

I know my parents would have been shocked if they knew the content of the books I was reading: Philip Roth’s “Portnoy’s Complaint,” for instance, which was banned in Australia from 1969 to 1971. I didn’t pick up this quintessential American novel, or any other, because I thought reading it would be good for me. I was looking for stories that would thrill me and confuse me, as “Portnoy’s Complaint” did. For decades afterward, all I remembered of the novel was how the young Alexander Portnoy masturbated with anything he could get his hands on, including a slab of liver. After consummating his affair with said liver, Alex returned it to the fridge. Blissfully ignorant, the Portnoy family dined on the violated liver later that night. Gross!

Who eats liver for dinner?

As it turns out, my family. Roth’s book was a bridge across cultures for me. Even though Vietnamese refugees differ from Jewish Americans, I recognized some of our obsessions in Roth’s Jewish American world, with its ambitions for upward mobility and assimilation, its pronounced “ethnic” features and its sense of a horrifying history not far behind. I empathized. And I could see some of myself in the erotically obsessed Portnoy — so much so that I paid tribute to Roth by having the narrator of “The Sympathizer” abuse a squid in a masturbatory frenzy and then eat it later with his mother. (“The Sympathizer” has not been banned outright in Vietnam, but I’ve faced enormous hurdles while trying to have it published there. It’s clear to me that this is because of its depiction of the war and its aftermath, not the sexy squid.)

Banning is an act of fear — the fear of dangerous and contagious ideas. The best, and perhaps most dangerous, books deliver these ideas in something just as troubling and infectious: a good story.

So it was with somewhat mixed feelings that I learned some American high school teachers assign “The Sympathizer” as required reading in their classes. For the most part, I’m delighted. But then I worry: I don’t want to be anyone’s homework. I don’t want my book to be broccoli.

I was reassured, however, when a first-year college student approached me at an event to tell me she had read my novel in high school.

“Honestly,” she said, “all I remember is when the sympathizer has sex with a squid.”

Mission accomplished.

Viet Thanh Nguyen is the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Sympathizer” and the children’s book “Chicken of the Sea,” written with his then 5-year-old son, Ellison, among other books.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

An earlier version of this article misstated the year “Close Quarters” by Larry Heinemann was published. The novel was published in 1977, not 1974, which is when a chapter from the work in progress appeared in Penthouse.

How we handle corrections

Viet Thanh Nguyen is the author of “Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War.”

Sunday, June 2, 2024

Brandeis University’s Independent Student Newspaper Since 1949 | Waltham, MA

- Arts & Culture

Unveiling the unseen: Confronting book bans and educational censorship

Young-adult fiction author julian winters and dr. tanishia lavette williams discuss book censorship in an event hosted by compact..

On April 3, the Samuels Center for Community Partnerships and Civic Transformation hosted a discussion on book bans with author Julian Winters, student organizer Cameron Samuels and Dr. Tanishia Lavette Williams, a Brandeis Florence Levy Kay Fellow in Racial Justice, Education, and the Carceral State.

Samuels is a leading activist in the movement against censorship in Katy Texas who testified before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee in September 2023 on the topic of banned books.

In 2023, 4,250 different books were challenged to be banned, especially in libraries and schools, many of which included those that centered on marginalized voices or about topics related to race, religion, gender identity or sexuality. The talk, funded by COMPACT’s Maurice J. and Fay B. Karpf and Ari Hahn Peace Awards and the ENACT Educate and Advocate Grant, was planned about a year in advance.