The politicisation of judiciary and the judicialisation of politics — who is to blame?

In recent months, Pakistan's superior judiciary has found itself mired in controversy, either due to internal schisms over administrative authority or external pressures over the formation of benches.

But Pakistan's judiciary is no stranger to controversy. Over the years, it has been responsible for its fair share of excesses, often done under the garb of being the protector of the Constitution and upholder of the rule of law.

Some who have dared to challenge the legitimacy of the judiciary’s not-so-kosher actions have found themselves staring down the barrel of contempt of court charges . By shutting down fair criticism, the judiciary has exalted itself to a near-untouchable and unaccountable status.

The judicial activism we see on display in Pakistan today has a long and troubling history, starting with the infamous Molvi Tamizuddin case in 1954, in which the then Chief Justice of Pakistan Muhammad Munir, along with four other judges, declared the dissolution of the legislative assembly by Governor General Ghulam Mohammad legally valid.

This would become the first of many instances where the courts legitimised the abrogation of the Constitution under the guise of the ‘doctrine of necessity’. In more recent times, these excesses have morphed into needless suo motu actions, as well as interference in political decisions, through which the judiciary has repeatedly overstepped its constitutional bounds, damaging both democracy and institutions of governance in the process.

Legacy of the Lawyers' Movement

Modern day judicial activism took off considerably after the Lawyers' Movement of 2007-2009 . While it was a grassroots level movement, engaging local bar councils from across the country, political parties also threw their weight behind the campaign due to its mass appeal.

The PPP was at the forefront of this political support, but when President Asif Ali Zardari failed to reinstate judges sacked by his predecessor, General Musharraf, for refusing to take oath under the Provisional Constitutional Order, the movement started targeting him for reneging on his promises.

This also led to the fracture of the Lawyers' Movement into pro-judiciary and pro-government camps — each with their own support bases and affiliated political parties — ushering in a new era of political and establishment intervention in the judiciary.

Read more: Role of the judiciary

Thus, despite the fact that the modern judiciary is the brainchild of a mass movement — that supposedly gave way to an independent judicial system — it has not been able to shake the impression of being controlled by the establishment. In fact, that perception has only grown, primarily due to the fact that the superior judiciary has repeatedly been accused of involvement in ‘political engineering’ and regime changes.

Political interference

Article 184(3), which grants the Supreme Court suo motu powers, on its own is an effective tool by way of which the constitutional validity of laws and decisions made by public bodies may be reviewed.

The actual issue arises when judges show unnecessary eagerness to invalidate legislative or executive actions. Moreover, in some cases, the superior judiciary has been seen to go beyond the confines of the petitions before it and allow its own personal views to influence decisions on matters of public policy.

Read more: Judicial overreach?

Take for example the decision taken by the Supreme Court in 2012 to suspend 28 lawmakers . The special bench comprising Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry passed the order while hearing petitions filed by the PTI and the PPP, challenging the validity of by-polls conducted on the basis of bogus entries in the electoral rolls leading up to the February 2008 elections.

The court went beyond the ambit of the petitions to question why the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) was not properly constituted in accordance with the 18th Amendment. Moreover, it tied the reinstatement of the suspended lawmakers on the condition of passage of the 20th Amendment. This condition set off another round of political confrontations as the court gave opposition parties leverage to drag their feet. It also set a dangerous precedent of the court setting aside the results of an election.

Suo motu action over delay Punjab and KP polls

The recent suo motu action by the Supreme Court over delay in the elections of Punjab and KP, much like the suo motu proceedings in 2012, are being called out by legal experts as well as some judges of the Supreme Court as unjustified.

While few constitutionalists would argue against the verdict ordering the ECP to hold elections within 90 days, it is the manner in which the suo motu proceedings were conducted that made it controversial, particularly in light of the recusals that followed.

As Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail pointed out in his dissenting note , the bench of Justice Ijazul Ahsan and Mazahir Ali Akbar Naqvi, while hearing an unrelated petition, summoned the Chief Election Commissioner and asked about the delay in elections in Punjab.

In these circumstances, suo motu action was unjustified, observed Justice Mandokhail. Agreeing with him, Justice Yahya Afridi termed it “judicial pre-emptive eagerness to decide", especially considering the fact that an intra-court appeal on the same matter was pending before the Lahore High Court.

Then there was the matter of bench formation, in which Justices Qazi Faez Isa and Sardar Tariq Masood — the two senior-most judges after Chief Justice of Pakistan Umar Ata Bandial — were absent. However, Justice Mazahir Ali Akbar Naqvi, the subject of an audio leak controversy , was included in the same bench — a move that was "inappropriate", wrote Justice Mansoor Ali Shah in his dissenting note. "This inclusion becomes more nuanced when other senior Hon’ble Judges of this Court are not included on the Bench,” Justice Shah added.

This controversial judicial episode simply shows that it does not matter if the decisions taken in the end are correct. What matters is the way in which those decisions are taken. As the popular maxim goes, justice must not only be done, it must also be seen to be done. If the impression given by a particular decision is one of partiality and favouritism, the objectives of justice have been defeated.

PTI petition against ECP order to delay elections

Weeks after the SC verdict, ordering the ECP to conduct the provincial elections on time, a five-member bench was formed to hear the PTI’s petition against the electoral watchdog's decision to delay elections in Punjab — in contravention of the SC's orders.

Once again, notable names were missing from a case of grave constitutional importance. The inclusion of Justice Ijazul Ahsan, after he had recused himself from a previous nine-member bench over allegations that he had already disclosed his mind, was a surprise entry. From the outset, Justice Mandokhail maintained that the Supreme Court had dismissed the suo motu case with a 4-3 majority, and stuck to disagreements expressed in his dissenting note.

While the hearing on this petition was ongoing, Justice Qazi Faez Isa authored a 12-page judgement where he remarked that the CJP does not have unilateral power to constitute benches and select judges, and that all cases under Article 184(3) be postponed until amendments are made to the Supreme Court Rules 1980 regarding the CJP’s discretionary powers.

On the basis of this judgement, Justice Aminuddin Khan recused himself from the bench, which was followed soon after by the recusal of Justice Mandokhail.

Subsequently, the CJP, through SC Registrar Ishrat Ali, issued a circular in which he disregarded the aforementioned judgement, and resumed hearing with the remaining three judges. This three member-bench ruled on Tuesday that the ECP decision to postpone polls in Punjab till Oct 8 was “unconstitutional” and fixed May 14 as the date for elections in the province.

The verdict came amid an outcry from various political circles for the formation of a full court to dispel the notion of bias and settle the matter of election delay conclusively. A request in this regard by Attorney General for Pakistan (AGP) Mansoor Awan has already been rejected by the CJP.

The judicialisation of politics and politicisation of the judiciary cuts both ways. Quite often, courts are dragged into the political domain, making them a subject of criticism and ridicule. But the judiciary has also made itself controversial by eagerly interfering in matters that should ordinarily have political solutions. The election date issue is now extremely polarised. Barring a full court, any verdict would invite a fresh round of public bashing from relevant stakeholders on either side of the political aisle.

Read more: Beginning of another crisis? Legal eagles weigh in on SC’s Punjab poll verdict

Judicial activism in recent history

In legal parlance, the ends do not justify the means. The process of attaining justice sometimes carries more importance than the final judgement itself. If the former is tainted, the latter, though binding, will not be respected.

Events surrounding the vote of no-confidence last year serve as another example of this phenomenon. Restoration of the National Assembly after dissolution by the President was a noble move on the part of the Supreme Court as it broke away from the ugly precedent of the ‘doctrine of necessity’.

However, the late-night opening of the Islamabad High Court and Supreme Court offices — as the clock approached midnight on April 9 and the speaker was reluctant to put the no-confidence motion to vote — drew widespread criticism.

The fact that this happened soon after news broke that then-Prime Minister Imran Khan may denotify the incumbent Chief of Army Staff, served to create the perception that it was done at the behest of the establishment.

Judicial actions are supposed to be reactive, not proactive in nature. In that instance, however, the Supreme Court took notice before the speaker committed contempt by violating the restoration order. And it did so after regular court timings, which is highly unusual.

The court might well have been performing its constitutional duty as the final arbiter of the rule of law. However, what is visible, sells. And what was seen here was a court unilaterally eager to perform the role of both the legislature and the executive.

Recent history is replete with other examples of judicial activism and political intervention by the judiciary — the blatant constitutional rewriting by the Supreme Court in its decision on a presidential reference seeking interpretation of Article 63-A, the surprise hospital visits by former Chief Justice Saqib Nisar, declaration of disqualification under Article 62(1)(f) to be permanent in nature and the conviction and disqualification of former Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gillani — have all served to tarnish the reputation of the judiciary and polarised public opinion towards it.

The impact of judicial activism beyond politics

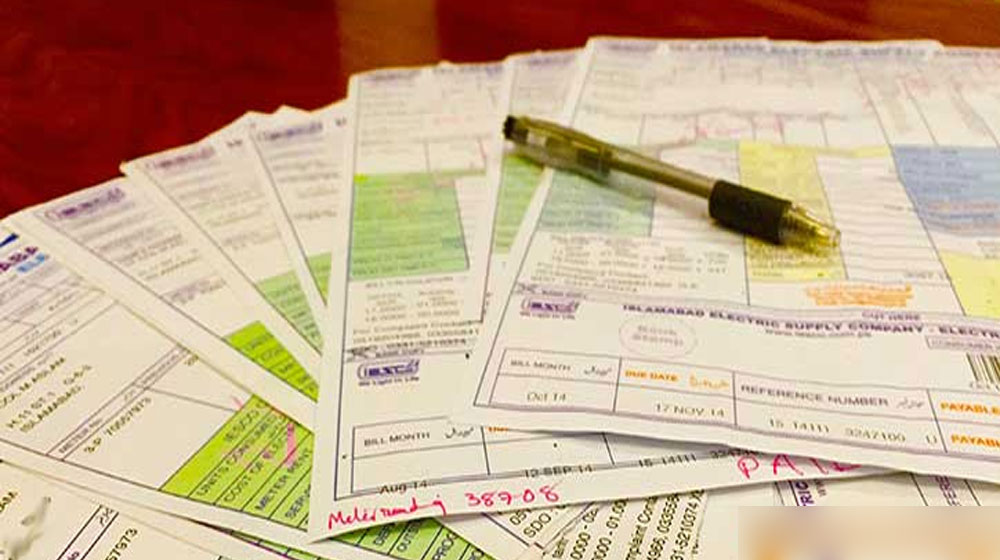

Judicial activism also has dire economic consequences . It hurts investor sentiment who fear that the risk of litigation may create unnecessary constraints. Foreign investors, in particular, shy away from uncertainty and unpredictability, an environment created by needless intervention by the judiciary in the executive and legislative domains. The botched privatisation of Pakistan Steel Mills in 2006 at the hands of the Supreme Court serves as a prominent example, which has cost the national exchequer an exorbitant amount to date.

An overly eager judiciary, that is perceived to be trampling institutional bounds, also serves to turn public sentiment against the courts. Political decisions will always have polarising reactions, and usually that anger is directed towards the legislature and executive — two institutions that are constitutionally mandated to protect public welfare. However, public contempt is redirected towards the courts and the military when political decisions are seen to be taken by them.

Last but not by far the least, judicial activism weakens democracy . It comes at the expense of parliamentary sovereignty and supremacy. Lawmakers become dependent on courts to offer legitimacy to their actions or undermine those of their opponents. In the process, the institutional capacity of both the legislature and the executive is damaged.

Unfortunately, in Pakistan, the weakening of democracy goes hand in hand with strengthening of the military. In addition to the aforementioned Molvi Tamizuddin case, the Zafar Ali Shah case , where General Musharraf’s 1999 imposition of martial law was rubber stamped by the Supreme Court, and the Begum Nusrat Bhutto case , whereby General Ziaul Haq’s 1977 declaration of martial law was given legal cover by then Chief Justice Anwarul Haq’s court, are all important readings for those looking to learn more about the judiciary’s role in undermining democracy.

Reforming the judicial system

First and foremost, the administrative authority of the CJP must be curtailed. Powers related to appointment and removal of judges, exercise of suo motu powers and the constitution of benches give unbridled influence to one single person to run an entire institution based on their own whims.

To this end, an independent and objective criterion for the selection of judicial nominees must be introduced. There should be input from all stakeholders in society on this matter. And the use of discretion to pick and choose judges for specific cases must be regulated.

Bench formation should be a transparent process. Suo motu jurisdiction must be limited to issues of fundamental rights. Taking up any matter as a suo motu case has been seen to facilitate misuse of authority. The Supreme Court (Practise and Procedure) Bill 2023 recently passed in the National Assembly is a step in the right direction, although it is likely to face many legal hurdles.

Secondly, the legislative and executive branches must also stop involving the courts in issues that fall within the political domain. There are an exceedingly large number of frivolous cases filed by rival political parties against each other. Such cluttering of the legal system only serves to delay justice for those who truly need it.

Lastly, judges must also realise that they are not above criticism and must submit themselves to institutional checks and balances. The judiciary must not continue to dangle the contempt of court sword over society in an attempt to curb valid and necessary criticism.

In the process of targeting the military for institutional abuse of power, the acts of the judiciary often go unnoticed, even though the judiciary has often served as a proxy for the establishment.

History reveals dire consequences of politicised courts and judicialised politics. It would be a fool’s paradise to expect anything different from the future without implementing judicial reforms. It is high time to break the cycle of institutional transgressions. Only then will democracy in Pakistan begin to gain a foothold.

SC to announce all-important verdict on PTI petition challenging delay in Punjab polls tomorrow

Role of the judiciary

A judicial renaissance?

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.

Premium Content

Republic Policy

Constitutional Law

Criminal Law

International Law

Civil Service Law

Recruitment

Appointment

Civil Services Reforms

Legislature

Fundamental Rights

Civil & Political Rights

Economic, Social & Cultural Rights

Focused Rights

Political Philosophy

Political Economy

International Relations

National Politics

- Organization

Malik Abdul Latif Tahir

Independence of Judiciary and Pakistan

The independence of the judiciary in Pakistan is a vital issue that has implications for the country’s democracy, the rule of law, human rights, and stability. The judiciary is supposed to be an independent and impartial arbiter of justice, free from any interference or influence from the executive, the legislature, or any other external forces. However, the history of Pakistan shows that the judiciary has often been subjected to various forms of pressure, manipulation, and subversion by the political and military elites, as well as by religious and sectarian groups. This has undermined the credibility, integrity, and effectiveness of the judicial system and has eroded the public trust and confidence in the courts.

The significance of judicial independence in Pakistan can be explained from various perspectives.

First, judicial independence is essential for upholding the Constitution and the fundamental rights of the citizens. The Constitution of Pakistan entrusts the superior judiciary with the obligation to preserve, protect and defend the constitution. The judiciary also has the power of judicial review, which enables it to examine the validity and constitutionality of the laws and actions of the other branches of government. The judiciary can also issue writs of habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto, and certiorari to protect the rights and liberties of individuals against arbitrary or unlawful detention, discrimination, abuse of power, or violation of due process. With judicial independence, these constitutional functions and powers would be protected from the interference or influence of other actors.

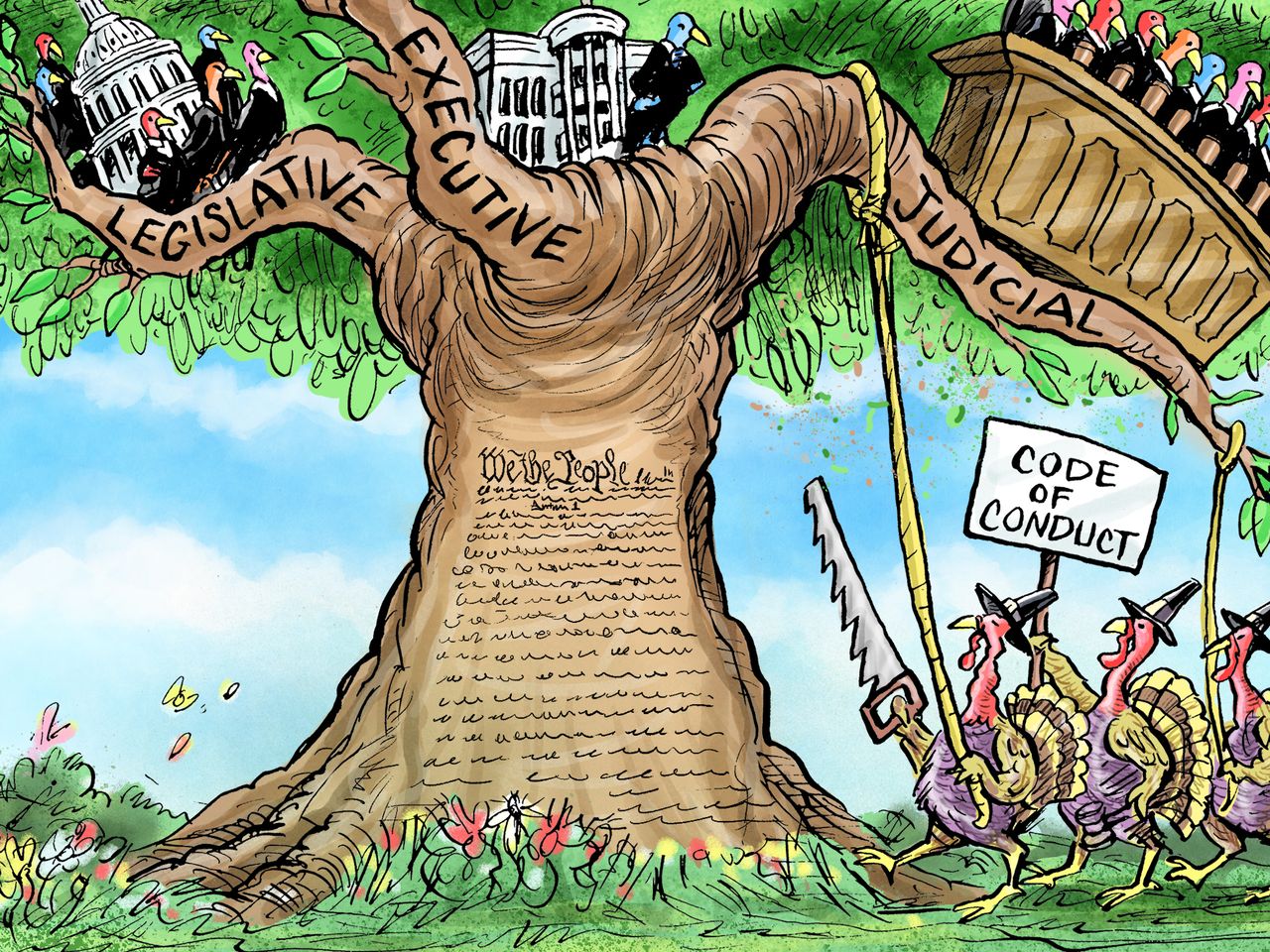

Please, subscribe to the website of republicpolicy.com

Second, judicial independence is crucial for maintaining the separation of powers and checks and balances among the three branches of government. The separation of powers is a principle that divides the state authority into legislative, executive, and judicial branches, each with its own functions and responsibilities. The checks and balances are mechanisms that prevent any branch from becoming too powerful or dominant over the others. The judiciary plays a key role in ensuring that each branch acts within its constitutional limits and respects the authority of the others. The judiciary also acts as a guardian of democracy by ensuring free and fair elections, resolving electoral disputes, and adjudicating on matters related to political parties, candidates, and voters. Without judicial independence, the separation of powers and checks and balances would be distorted or disrupted by the encroachment or domination of one branch over the others.

Third, judicial independence is important for establishing the rule of law and accountability in society. The rule of law is a principle that requires that all persons and institutions are subject to and accountable to the law that is fairly applied and enforced. The rule of law also implies that no one is above the law and that everyone is equal before the law. The judiciary is responsible for interpreting and applying the law in a consistent and impartial manner, regardless of the status or position of the parties involved. The judiciary also holds the other branches of government accountable for their actions and decisions by reviewing their legality and constitutionality. Without judicial independence, the rule of law and accountability would be undermined or violated by the prevalence of corruption, nepotism, favouritism, or impunity in society.

Fourth, judicial independence is vital for ensuring peace and stability in the country. Pakistan is a diverse and complex country with various ethnic, linguistic, religious, sectarian, regional, and ideological groups. These groups often have conflicting interests and demands that may lead to violence or unrest. The judiciary can play a constructive role in resolving these conflicts peacefully through dialogue, mediation, arbitration, or adjudication. The judiciary can also promote social harmony and cohesion by protecting the rights and interests of minorities, women, children, marginalized groups, and vulnerable sections of society. Without judicial independence, these conflicts would escalate or persist without resolution or redress. This would create more chaos or instability in the country.

Therefore, judicial independence in Pakistan is a significant issue that has multiple dimensions and implications. Judicial independence is essential for upholding the Constitution and fundamental rights, maintaining separation of powers and checks and balances, establishing rule of law accountability, and ensuring peace and stability in the country. However, judicial independence has often been challenged or threatened by various factors such as political interference, military intervention, religious extremism, media pressure, public opinion, etc. Therefore, it is imperative that all stakeholders respect and support judicial independence as a cornerstone of democracy development in Pakistan.

Republic Policy Magazine October 2023

Reforming the judiciary in Pakistan is a complex and challenging task that requires a holistic and collaborative approach from all stakeholders, including the government, the judiciary, the legal fraternity, the civil society, and the international community. The following are the key points to reform the judiciary in Pakistan.

Strengthening the judicial independence and accountability: The judiciary should be free from any interference or influence from the executive, the legislature, or any other external forces. The judiciary should also be accountable for its performance and conduct and subject to effective oversight and disciplinary mechanisms. The appointment, promotion, and removal of judges should be based on merit, transparency, and fairness. The judicial budget should be adequate and autonomous, and the judicial salaries and benefits should be commensurate with their responsibilities and qualifications.

Improving judicial efficiency and quality: The judiciary should adopt modern case management systems and technology to rationalize court processes, reduce delays, and improve transparency. The judiciary should also introduce alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms, such as mediation and arbitration, to provide quicker and cost-effective dispute resolution methods. The judiciary should also enhance its skills and knowledge by providing ongoing education and training programs for judges and legal professionals. The judiciary should also ensure that its decisions are consistent, coherent, and well-reasoned and that they reflect the current legal principles and social realities.

Enhancing judicial accessibility and responsiveness: The judiciary should improve access to justice for marginalized communities by providing legal aid, establishing legal aid centres, and promoting pro bono services1. The judiciary should also ensure that its services are affordable, convenient, and user-friendly for all citizens. The judiciary should also address the diverse needs and expectations of different groups in society, such as women, children, minorities, vulnerable sections, etc. The judiciary should also foster public trust and confidence by engaging in effective communication and outreach activities with the public.

Reforming the judicial laws and procedures: The judiciary should revise and update the outdated and faulty laws governing economic transactions, land revenue, criminal justice, etc., to make them applicable in the present world. The judiciary should also simplify and streamline the judicial laws and procedures to make them more uniform and efficient. The judiciary should also harmonize the judicial laws and procedures with the constitutional provisions and international standards of human rights.

Promoting judicial innovation and creativity: The judiciary should embrace innovation and creativity in its functions and services. The judiciary should use modern tools and technology in the investigation process, such as biometrics, forensics, digital evidence, etc.4. The judiciary should also explore new ways of delivering justice, such as online courts, mobile courts, etc. The judiciary should also encourage research and development in the field of law and justice.

Please, subscribe to the YouTube channel of republicpolicy.com

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Search the Blog

Significance of Parliamentary Committees for Parliamentary System in Pakistan

The Power of Propaganda in Shaping Narratives

The Campus Protests in USA & the Politics of Biden

Is Inflation Falling in Pakistan Finally?

India’s Stance on Kashmir Going Deeper into AJK

The Significance of Iran-Pakistan Gas Pipeline

The Challenge of Rising Tariffs and the Economy of Pakistan

The Importance of International Day of Multilateralism and Diplomacy for Peace, 24 April

The Significance of Iran & Pakistan Relations

The Importance of Independent Judiciary and IHC Letter

Support our cause.

"Republic Policy Think Tank, a team of dedicated volunteers, is working tirelessly to make Pakistan a thriving republic. We champion reforms, advocate for good governance, and fight for human rights, the rule of law, and a strong federal system. Your contribution, big or small, fuels our fight. Donate today and help us build a brighter future for all."

Qiuck Links

- Op Ed columns

Contact Details

- Editor: +923006650789

- Lahore Office: +923014243788

- E-mail: [email protected]

- Lahore Office: 143-Gull-e-Daman, College Road, Lahore

- Islamabad Office: Zafar qamar and Co. Office No. 7, 1st Floor, Qasim Arcade, Street 124, G-13/4 Mini Market, Adjacent to Masjid Ali Murtaza, Islamabad

- Submission Guidelines

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy & Policy

Copyright © 2024 Republic Policy

| Developed and managed by Abdcorp.co

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

A Strong Judiciary as a Crisis for Democracy: A ‘Law and Development’ Study from Pakistan

By the late 1990s, international financial institutions prescribed a ‘good governance’ paradigm that sought to empower the judiciary to curb ‘state capture’ by the corrupt political elites of developing countries. Good governance was supposed to act as a midwife to economic development, providing the ‘rule of law’ for the free market reforms of structural adjustment programs that had hitherto failed to provide much success. This article examines the implementation of ‘good governance’ in Pakistan, arguing that empowering the judiciary served to weaken an already weak legislature. The tangible issues of popular political representation and economic redistribution were displaced by the discourses on the control of corruption and the rule of law. Based on this experience, the article encourages a shift in law and developmental theorizing to focus on forms of legislature and democratic rule and a redefined role for the ‘civil society’ within this.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Sara Abraham, Noaman G. Ali, Kasim Tirmizey and Adil Chatta for research help and for reviewing this paper.

Abbasi, Muhammad Zubair, Judicial Islamization of Land Reforms in Pakistan: Triumph of Legal Realism , 57 Islamic Studies, no. 3-4 (2018). Search in Google Scholar

Agha, Ayesha Siddiqa, “The Political Economy of National Security,” in S. Akbar Zaidi (ed.), Continuity and Change: Socio-Political and Institutional Dynamics in Pakistan (Karachi: City Press, 2003). Search in Google Scholar

Alavi, Hamza, Elite Farmer Strategy and Regional Disparities in the Agricultural Development of Pakistan, 8 Economic and Political Weekly , no. 13 (1973). Search in Google Scholar

Altaf, Samia W., So Much Aid, So Little Development: Stories from Pakistan (Lahore: ILQA Publications, 2011). Search in Google Scholar

Armytage, Livingston, Pakistan’s Law and Justice Sector Reforms Experience – Some Lessons , PLJ Journal Section [2004]. Search in Google Scholar

Azeem, Muhammad, Law, State and Inequality in Pakistan: Explaining the Rise of the Judiciary (Singapore: Springer, 2017). Search in Google Scholar

Bari Faisal, Ali Cheema and Ehsan-ul-Haque, Regulatory Impediments, Market Imperfections and Firm Growth: Analyzing the Constraints to SME Growth in Pakistan , A Study Conducted for the Asian Development Bank (ADB), 2002. Search in Google Scholar

Baxter, Craig (ed.), Pakistan on the Brink: Politics, Economics and Society (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2004). Search in Google Scholar

Bennett, Jennifer, Development Alternatives: NGO-Government Partnership in Pakistan , Working Paper Series no. 3 (Islamabad: SDPI, 1998). Search in Google Scholar

Bhutto, Benazir, Daughter of the East: An Autobiography (2nd ed., London: Simon & Schuster, 2007). Search in Google Scholar

Braibanti, Ralph, “The Role of Law in the Political Development of Pakistan,” in Ralph Braibanti, Chief Justice Cornelius of Pakistan: An Analysis with Letters and Speeches (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1999). Search in Google Scholar

Brohi, A.K. Disenchantment with Parliamentary Democracy , PLD Journal Section [1977]. Search in Google Scholar

Cheema, Ali, Adnan Q. Khan and Rogers B. Myerson, Breaking the Countercyclical Pattern of Local Democracy in Pakistan (2014), available at: < http://home.uchicago.edu/∼rmyerson/research/pakdemoc.pdf >. Search in Google Scholar

Cheema, Ali, Asim Ijaz Khawaja and Adnan Qadir , Decentralization in Pakistan: Context, Content, and Causes , Faculty Research Working Paper Series, No. RWP05-034 (John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 2005). Search in Google Scholar

Cheema, Ali, Hassan Javid, and Muhammad F. Naseer, Dynastic Politics in Punjab: Facts, Myths and their Implications , Working Paper Series No. 01-13 (Lahore: Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives, 2013). Search in Google Scholar

Cheema, Moeen H. and Ijaz Shafi Gilani (eds.), The Politics and Jurisprudence of the Chaudhry Court 2005-2013 (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2015). Search in Google Scholar

Conard, D., In Defense of the Continuity of Law: Pakistan’s Courts in Crisis of State , PLD Journal Section [1985]. Search in Google Scholar

Cornelius, A.R., “Islam and Human Rights,” in Ralph Braibanti, Chief Justice Cornelius of Pakistan: An Analysis with Letters and Speeches (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1999). Search in Google Scholar

Cornelius, A.R., Power of the “word” in Context of National Leadership: Need for Expressing Fundamental Rights in Language of Islamic Scriptures , PLD Journal Section [1965]. Search in Google Scholar

Cornelius, A.R., Spirit of the Pakistan: An “Act of Faith,” PLD Journal Section [1967]. Search in Google Scholar

Easterly, William, “Political economy of growth without development: a case study of Pakistan,” in Dani Rodrik (ed.), In Search of Prosperity: Analytical Narratives of Growth (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003). Search in Google Scholar

Ehi Oshio, P., Military Coups D’ Etat in Nigeria: Rationale, Legality and Effects on Constitutionalism , PLJ Journal Section [1986]. Search in Google Scholar

Engerman, David C., Nils Gilman, Mark H. Haefele and Michael E. Latham (eds.), Staging Growth: Modernization, Development, and the Global Cold War (Amherst, Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003). Search in Google Scholar

Ercelawn, Aly and M. Nauman, “Market-Based Justice: The Asian Development Bank and Legal Reforms,” in S. Akbar Zaidi (ed.), Continuity and Change: Socio- Political and Institutional Dynamics in Pakistan (Karachi: City Press, 2003). Search in Google Scholar

Ghias, Shoaib A., Miscarriage of Chief Justice: Judicial Power and the Legal Complex in Pakistan under Musharraf, 35 Law and Social Inquiry , no. 4 (2010). Search in Google Scholar

Hasan, T., The Need of Judicial Activism and Chief Justice Supreme Court Iftikhar Chaudhry as a “Judicial Activist” on the basis of PIL, 15 ILSA Journal of International & Comparative Law , no. 1 (2008–2009). Search in Google Scholar

Hathaway, Robert M. & Wilson Lee (eds.), Islamization and the Pakistani Economy (Washington DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2004). Search in Google Scholar

Hoque, Ridwanul, Judicial Activism in Bangladesh: A Golden Mean Approach (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011). Search in Google Scholar

Hussain, Khurram, “ Who is running the country ,” Dawn, May 30, 2019. Search in Google Scholar

Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay and Massimo Mastruzzi, The Worldwide Governance Indicators Project: Answering the Critics , World Bank policy research working paper no. 4149 (World Bank, Washington DC, 2006). Search in Google Scholar

Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay and Massimo Mastruzzi, Governance Matters, governance indicators for 1996–2005 , World Bank policy research working paper no. 4012 (World Bank, Washington DC, 2006). Search in Google Scholar

Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay and Pablo Zoido-Lobaton, “Governance Matters” , available at: < http://elibrary.worldbank.org/action/doSearch?AllField=daniel+kaufmann&startPage >, accessed December 6, 2013. Search in Google Scholar

Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay and Pablo Zoido-Lobaton, Governance Matters: From Measurement to Action, 37 Finance & Development: a quarterly magazine of the IMF , no. 2 (2000). Search in Google Scholar

Kennedy, Charles H. and Cynthia A. Botteron (eds.), Pakistan: 2005 (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2005). Search in Google Scholar

Kennedy, Charles H. and Rasul Bakhsh Rais (eds.), Pakistan: 1995–96 (Lahore: Vanguard, 1995). Search in Google Scholar

Kennedy, Charles H., Repugnancy to Islam- Who Decides? Islam and Legal Reforms in Pakistan, 41 International and Comparative Law Quarterly , no. 4 (1992). Search in Google Scholar

Kennedy, Duncan, “Three Globalizations of Law and Legal Thought,” in David M. Trubek and Alvaro Santos (eds.), The New Law and Economic Development: A Critical Appraisal (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). Search in Google Scholar

Khan, Shahrukh Rafi, A. Qadir, Aasim Sajjad Akhtar, Ahmad, Saleem and F. Sadiq, The Case for Land and Agrarian Reforms in Pakistan , Policy Brief Series no. 12 (Islamabad: SDPI, 2001). Search in Google Scholar

Khan, Shahrukh Rafi, Costing the National Reconstruction Bureau’s Local Government Plan (2000) , Policy Research Series no. 1 (Islamabad: SDPI, 2000). Search in Google Scholar

Khan, Shahrukh Rafi, Devolution of Power to the Grassroots Level , Policy Paper Series no. 25 (Islamabad: SDPI, 2000). Search in Google Scholar

Khan, Shahrukh Rafi and S. Aftab, “ Structural Adjustment, Labor and the Poor in Pakistan ,” Research Report Series NO. 8 (Islamabad: SDPI, 1995). Search in Google Scholar

Khattak, Saba Gul, Women and Local Government , Working paper Series no. 24 (Islamabad: SDPI, 1996). Search in Google Scholar

Lau, Martin, The Role of Islam in the Legal System of Pakistan (London/Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2006). Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Yong-Shik, Law and Development: Theory and Practice (Routledge, 2019). Search in Google Scholar

Lee, Yong-Shik, General Theory of Law and Development, 50 Cornell International Law Journal , no. 3 (2017), 415-472. Search in Google Scholar

Leite, Carlos A., Jens Weidemann, Does mother nature corrupt? Natural resources , Corruption and Economic Growth, IMF working paper no. 99/85 (IMF, 1999). Search in Google Scholar

Lindsey, Tim (ed.), Law Reform in Developing and Transitional States (London and New York: Routledge, 2007). Search in Google Scholar

Malik, Muneer A., The Pakistan Lawyers’ Movement: An Unfinished Agenda (Karachi: Pakistan Law House, 2008). Search in Google Scholar

Mintz, Joel A., Introductory Note: A Perspective on Pakistan’s Chief Justice, Judicial Independence, and the Rule of Law, 15 ILSA Journal of International & Comparative Law , no. 1 (2008-2009). Search in Google Scholar

Mo, Pak Hung, Corruption and Economic Growth, 29 Journal of Comparative Economics , no. 1 (2001). Search in Google Scholar

Moyo, Sam and Paris Yeros, Intervention: The Zimbabwe Question and the Two Lefts, 15 Historical Materialism [2007]. Search in Google Scholar

Munir, Muhammad, Highways and Bye-ways of Life (Lahore: Law Publishing Company, 1978). Search in Google Scholar

Narejo, Iqbal (ed.), Whither Pakistan: Dictatorship or Democracy? (Lahore: Al-Hamd Publications, 2007). Search in Google Scholar

Nazli, Hina and Sohail J. Malik, Housing opportunity, security and empowerment for the poor, 42 Pakistan Development Review , no. 4 (2003). Search in Google Scholar

North, Douglass, Understanding the Process of Economic Change (Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2005). Search in Google Scholar

Pakistan Bar Council, White Paper against Judiciary : available at < http://pakistanbarcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/White-Paper_Complete_.pdf >, accessed November 1, 2012. Search in Google Scholar

Persson, Torston, Guido Tabellini & Francesco Trebbi, Electoral rules and corruption, 1 Journal of the European Economic Association , no. 4 (2003). Search in Google Scholar

Qureshi, Taiyyaba Ahmad, State of Emergency: General Pervez Musharraf’s Executive Assault on Judicial Independence in Pakistan, 35 North Carolina Journal of International Law & Comparative Regulation , no. 2 (2009–2010). Search in Google Scholar

Rahman, Shahid-ur, Who owns Pakistan: Fluctuating Fortunes of Business Mughals (1997), available at: < https://www.scribd.com/doc/125960792/Who-Owns-Pakistan >, accessed November 21, 2013. Search in Google Scholar

Reyntjens, Filip, The Winds of Change: Political and Constitutional Evolution in Francophone Africa, 1990-1991, 35 Journal of African Law , no. 1–2 (2009). Search in Google Scholar

Rostow, Walt W., The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960). Search in Google Scholar

Serra, Danila, Empirical Determinants of Corruption: A Sensitivity Analysis, 126 Public Choice (2006). Search in Google Scholar

Shivji, Issa G. (ed.), State and Constitutionalism: An African Debate on Democracy (Harare, Zimbabwe: SAPES Trust, 1991). Search in Google Scholar

Siddiqa, Ayesha, “ Imran Khan’s U.S. visit is for Home Audience. Bajwa Army will do the Real Talking ,” The Print, July 16, 2019, available at: < https://theprint.in/opinion/imran-khans-us-visit-is-for-home-audience-bajwas-army-will-do-the-real-talking/263450/ >, accessed September 28, 2019. Search in Google Scholar

Siddique, Osama, Pakistan’s Experience with Formal Law: An Alien Justice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). Search in Google Scholar

Smithey, Shannon Ishiyama and John Ishiyama, Judicial Activism in Post-Communist Politics, 36 Law & Society Review , no. 4 (2002). Search in Google Scholar

The World Bank , Pakistan: A Framework for Civil Service Reforms in Pakistan , Report No. 18386-PAK (December 15, 1998). Search in Google Scholar

Thelen, Kathleen and Sven Steinmo, Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992). Search in Google Scholar

Toor, Saadia, The State of Islam: Culture and Cold War Politics in Pakistan (London: Pluto Press, 2011). Search in Google Scholar

Treisman, Daniel, The causes of corruption: a cross-national study, 76 Journal of Public Economics , no. 3 (2000). Search in Google Scholar

Trubek, David M. and Alvaro Santos (eds.), The New Law and Economic Development: A Critical Appraisal (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). Search in Google Scholar

Trubek, David M. and Marc Galanter, Scholars in Self-Estrangement: Some Reflections on the Crisis in Law and Development Studies in the United States, 1974 Wisconsin Law Review , no. 4 (1974). Search in Google Scholar

Trubek, David M., Towards a Social Theory of Law, 82 The Yale Law Journal , No. 1 (1972). Search in Google Scholar

White, Lawrence J., Industrial Concentration and Economic Power in Pakistan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974). Search in Google Scholar

Williamson, Oliver E., The Institutions of Governance, 88 The American Economic Review , no. 2 (1998). Search in Google Scholar

Zaheer, Hasan, The Times and Trial of the Pindi Conspiracy Case 1951: The First Coup Attempt in Pakistan (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 1998). Search in Google Scholar

Zaman, Arshad, Eradicating Poverty in South Asia by the Year 2002: Issues in a New International Dialogue with Donors , Working paper series no. 14 (Islamabad: SDPI, 1993). Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

- X / Twitter

Supplementary Materials

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

Journal and Issue

Articles in the same issue.

Judicial Independence in Pakistan

- First Online: 24 February 2017

Cite this chapter

- Lorne Neudorf 2

501 Accesses

This chapter examines the legal principle of judicial independence in Pakistan in two stages. First, a brief analysis of select secondary sources, including academic commentary and the views of participants in Pakistan’s legal system, distills themes that are seen by observers as important to the meaning and practice of judicial independence in Pakistan. From this starting point, the study identifies and examines a number of primary legal sources related to the themes identified, including constitutional arrangements, legislation, and reported judicial decisions. These primary sources are used to construct a narrative of judicial independence in Pakistan from the time of its independence in 1947 to the first half of 2016. While the study draws on illustrative scholarship and commentary to identify themes, its focus is on the identification and analysis of primary legal sources that reflect institutional arrangements and shed light on the interactions between courts and other branches of government. The second stage of this study considers implications and lessons learned from the experience of judicial independence in Pakistan.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

See, e.g., Larkins ( 1996 ), p. 618. Although beyond the scope of this study focused on primary legal sources, there are a number of important historical and political works on Pakistan that provide additional detail in relation to the country’s present and past economic, political, and social context. See, e.g. , Wheeler ( 1970 ), Waseem ( 1989 ), Noman ( 1990 ), Shehab ( 1995 ), Kennedy ( 1996 ), Malik ( 1996 ), Shafqat ( 1997 ), Ahmed ( 1998 ), Ziring ( 1998 ), Akhtar ( 2000 ), Rizvi ( 2000 ), Desai and Ahsan ( 2005 ), Cloughley ( 2006 ), Kāẓmī ( 2009 ), Siddiqi ( 2012 ), Long ( 2015 ).

The division of time into these two periods is not based on a single event. Instead, the division is designed to facilitate a reflection on the overall developments after the first 50 years.

Pakistan’s population grew by more than 23 % over the most recent 10 years (from 153 million in 2005 to 189 million in 2015) while its per capita gross domestic product doubled during the same period ($714 in 2005 to $1429 in 2015): World Bank ( 2015 ). With a gross national income per capita of $14,400 in 2015, the World Bank classifies Pakistan as a lower middle income economy. All amounts in USD.

Talbot ( 2009 ), pp. 3–13, 50.

Abbasi ( 2012 ).

National Accountability Bureau ( 2002 ).

Islamic teaching also provides for an independent judiciary to determine disputes, see e.g., Cotran and Sherif ( 1999 ), Lau ( 2004 ), and Sherif and Brown ( 2003 ) who write that “the independence of the judiciary is a very well established principle in the Islamic Shari’a ”. This study focuses on the role of secular courts established on the English common law model. For an excellent overview of the use of precedent in Pakistan’s secular legal system see Munir ( 2014 ).

Jinnah’s ambition to establish an independent state as a homeland for India’s Muslims was initially opposed by other Indian Islamic parties who saw him as an advocate of the English legal system: Khan ( 2012 ), p. 291. Jinnah died 1 year into office.

Jinnah ( 1947 ).

The enactment of the Human Rights Act 1998, c. 42 incorporating the European Convention ( 1953 ) provides the English courts with the power to invalidate subordinate legislation or executive action on the basis of the Art. 6(1) guarantee of an independent and impartial tribunal. This power, to date, has been used sparingly by English courts: it does not defeat ‘dependent’ administrative decision-makers, such as government ministers exercising power under statute, nor has it radically altered the use of lay magistrates in England who enjoy none of the traditional protections of judicial independence such as guaranteed tenure, compensation, and administrative independence.

Khan ( 2004 ).

Khan ( 2016 ).

Newberg ( 1995 ).

Ibid , p. 11.

Ibid , pp. 2, 11.

Ibid , p. 5.

Ibid , pp. 12–13, Newberg writes that “[b]y allowing courts to operate, even if under stricture, the state has been the ultimate beneficiary of judicial largesse.”

Ibid , pp. 11–12.

Ibid , p. 6.

Ibid , p. 33.

Ibid , p. 13.

Ibid , pp. 4–5, 33.

Ibid , pp. 6–7, 13.

Ibid , pp. 5–6.

Ibid , pp. 248–250.

Ibid , p. 8.

Ibid , p. 250.

Lee ( 2010 ).

Ibid , p. 371.

Ibid , p. 372.

Ibid , p. 373.

Ibid , pp. 381–384; see the discussion of the judicial crisis below.

Ibid , pp. 386–387.

Constitution of Pakistan (1956), Constitution of Pakistan (1962).

Khan ( 2012 ), p. 8. For a discussion of the most recent amendment, see Newberg ( 2016 ).

Constitution (Nineteenth Amendment) Act, 2010, 1 (2011).

The Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution made several changes to the judicial appointment process in accordance with a Supreme Court ruling: see discussion below.

Constitution (Twentieth Amendment) Act, 2012, 5.

Ibid , Statement of Objects and Reasons.

In the case where the amendment alters the ‘limits’ of a province, a two-thirds majority of the province’s assembly is also required: Art. 239(4).

Arts. 141–144 distribute legislative powers between the federal government and the provinces.

Art. 41 sets out the qualifications and election procedure for the President while Art. 44 sets out the term of office for the President. It appears that under Art. 44(2) a single individual may hold the office of President for more than two terms provided they are not consecutive.

Arts. 46, 48. Note that under Art. 48(1), the President may require the Cabinet or Prime Minister to reconsider its advice although the President must act in accordance with the reconsideration within a period of 10 days.

Arts. 232–237.

Arts. 91(1), 91(6).

Arts. 91(3)-91(5).

Arts. 58, 90(1). For a detailed analysis of a previous version of Article 58, which provided the power for the President to dissolve the National Assembly, see Siddique ( 2006 ).

Art. 101(1).

Officially styled the Federal Shariat Court.

Art. 175(2).

Art. 187(1).

Art. 187(2).

Arts. 175, 184, 185, 186.

See, e.g. , Ontario (Attorney General) v Canada (Attorney General) , [1912] AC 571, where the Privy Council upheld a legislated reference procedure to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Supreme Court Rules, SRO 1159(I)/80.

Art. 199(1).

Huq ( 2003 –2004), p. 26, the judicial appointment process is discussed further below.

Art. 203D(1).

Art. 203D(3).

Art. 203DD with the exception of converting an acquittal into a conviction.

Art. 203G. Despite the parallel system of Islamic courts, it is evident from an analysis of the case law that secular higher courts have influenced the role of Islam in the legal system through their jurisprudence: Lau ( 2006 ).

See e.g., Lau ( 2006 ) and Nelson ( 2011 ).

Art. 175A(3).

Art. 193(2).

Arts. 177(2), 203C(3).

Arts. 178 (Supreme Court), 194 (High Courts), 203C(7) (Federal Sharia Court). The text of the oath is found in the Third Schedule to the Constitution.

Arts. 179, 195.

Hussain ( 2011 ), p. 20.

Arts. 8–28.

Art. 10(3).

Art. 232(1).

Art. 232(2).

Art. 233(1).

Art. 232(2)(c).

Provisional Constitutional Order, 1999, 2-10/99 Min. I.

Section 2(1) of the Provisional Constitutional Order. 1999, 2-10/99 Min. I. stated that “[n]otwithstanding the abeyance of the provisions of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, hereinafter referred to as the Constitution, Pakistan shall, subject to this Order and any other Orders made by the Chief Executive, be governed, as nearly as may be, in accordance with the Constitution.”

Hussain ( 2011 ), ss 11.2–11.4.

Supreme Court of Pakistan ( 2016 ).

Hussain ( 2011 ), p. 28.

Reuters ( 2012 ).

Art. 236(2).

Art. 24(4).

Art. 41(6).

Art. 69(1).

Arts. 99(2), 139(2).

Art. 105(2).

Art. 155(6).

Constitution (Amendment) Order 1985, Art. 165A(2).

Art. 212(2).

Art. 239(5).

Art. 245(2).

See, e.g., Zafar Ali Shah v General Pervez Musharraf, Chief Executive of Pakistan, PLD 2000 SC 869.

The Objectives Resolution (1949), now annexed to the Constitution and incorporated into its text through Art. 2A, was passed by the Constituent Assembly in March 1949 and provides that “the independence of the Judiciary shall be fully secured.”

Both the Preamble and Art. 2A, incorporating the Objectives Resolution, guarantee an independent judiciary, which has been treated as an enforceable legal right by the courts, discussed below.

Art. 81(a)(i).

Arts. 81(b), 81(d).

Arts. 209(6)-209(7) (removal procedure), Arts. 179, 195 (retirement for judges of the High Courts and the Supreme Court).

Arts. 187(2), 190.

Art. 204(2).

Third Schedule.

Constitution (Nineteenth Amendment) Act, 2010, 1 (2011) and Constitution (Twentieth Amendment) Act, 2012, 5.

See discussion below.

Ghias ( 2010 ), p. 997.

Ibid , p. 998.

Supreme Court of Pakistan ( 2009 ).

Ibid , Art. XI.

Art. 209(8).

Art. 209(5).

Dawn ( 2011a ).

For a critical overview of the functioning of the Supreme Judicial Council see Niazi ( 2016 ).

Arts. 209(4), 209(6).

Siddique (2013), pp. 267–269.

Ibid , p. 302.

Iqbal ( 2015 ).

Art. 142(d).

Acts of Parliament (2014).

Art. 142(c).

Arts. 142(b), 143.

Art. 59(1).

Art. 59(3).

Arts. 73(1), 73(1A).

Arts. 51(6), 213–226.

Arts. 52, 58.

Arts. 91(4), 91(5).

Art. 91(7).

Art. 70(3).

Arts. 75(1), 75(2).

See Lau ( 2004 ) for an analysis of how judges drew upon Islamic principles to preserve their independence.

Indian Independence Act 1947, 10 & 11 Geo 6, c. 30; see Khan ( 2004 ), p. 67.

Government of India Act 1935, 26 Geo 5 & 1 Edw 8, c. 2.

Indian Independence Act 1947, 10 & 11 Geo 6, c. 30.

Newberg ( 1995 ), p. 37.

Act of Settlement 1701, 12 and 13 Will, c. 2. See also the Commissions and Salaries of Judges Act of 1760, 1 Geo 3, c. 23. See, e.g., Section 200(2)(b) of the Government of India Act 1935, 26 Geo 5 & 1 Edw 8 c. 2 that sets out the removal process for judges of the Federal Court on the grounds of “misbehaviour or of infirmity of mind or body” but only if removal was recommended by the Privy Council. Section 201 of the Act establishes that the salaries, leave, and pension benefits for judges of the Federal Court shall not be “varied to his disadvantage after his appointment.”

Newberg ( 1995 ), p. 39.

Ibid , pp. 39–40.

Ibid , pp. 40–41.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 129.

Federation of Pakistan v Moulvi Tamizuddin Khan , PLD 1955 FC 240, p. 251.

Ibid , p. 300.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 140.

Ibid , pp. 141–142.

Ibid , pp. 142–143.

Newberg ( 1995 ), pp. 46–47.

Ibid , p. 49.

Ibid , p. 68.

Emergency Powers Ordinance IX of 1955.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 143.

Usif Patel v The Crown , PLD 1955 FC 387.

Ibid , pp. 391–392.

Ibid , p. 396.

Ibid , pp. 446–447.

Reference by HE the Governor-General , PLD 1955 FC 435.

For a detailed overview of the doctrine of necessity, see Wolf-Phillips ( 1979 ).

Reference by HE the Governor-General , PLD 1955 FC 435, p. 445.

Ibid , p. 448.

Ibid , p. 479.

Ibid , p. 486.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 153.

Newberg ( 1995 ), p. 55.

Ibid , pp. 60–61.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 158.

Newberg ( 1995 ), p. 69.

Khan ( 2004 ), pp. 197–209.

Ibid , p. 210.

Laws (Continuation in Force) Order (1958).

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 212.

The State v Dosso , PLD 1958 SC 533.

Kelsen ( 1945 ).

The State v Dosso , PLD 1958 SC 533, p. 538.

Ibid , pp. 538–539.

Ibid , p. 540.

Ibid , p. 541.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 217.

Newberg ( 1995 ), p. 79.

Ibid , pp. 79–80.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 216.

Pakistan’s GDP growth reached 10.4 % in 1965: World Bank ( 2015 ).

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 345.

Ibid , pp. 254–255.

Ibid , judicial review of the constitutional validity of legislation was made clear following the first amendment: ibid , p. 275.

Asma Jilani v Government of the Punjab , PLD 1972 SC 139, p. 161.

Khan ( 2004 ), pp. 323–329.

Ibid , p. 363.

Ibid , p. 375.

Ibid , pp. 375–376.

Ibid, pp. 385–388.

Ibid , pp. 406–407.

Time ( 1971 ). Bangladesh set up a war crimes court in 2010 to investigate crimes committed during the conflict: Al Jazeera ( 2010 ).

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 434.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 437.

Asma Jilani v Government of the Punjab , PLD 1972 SC 139.

Asma Jilani v Government of the Punjab , PLD 1972 SC 139, p. 166. The Supreme Court adopted this position, at least in part, to refute the Attorney General’s argument that the judiciary had given tacit approval to martial law: ibid , p. 203.

Asma Jilani v Government of the Punjab , PLD 1972 SC 139, pp. 197–199.

Asma Jilani v Government of the Punjab , PLD 1972 SC 139, pp. 178–179.

Ibid , p. 163.

Ibid , pp. 184–185.

Ibid , pp. 187–189.

Ibid , p. 190.

Ibid , pp. 190–192.

Ibid , p. 204.

Ibid , pp. 205–206.

Ibid , p. 207.

Ibid , p. 208. The Supreme Court also noted that the National Assembly ratified Bhutto’s assumption of power and an interim constitution, which “may well have radically altered the situation.”

Newberg ( 1995 ), p. 129.

Ibid , p. 122.

Ibid , p. 132.

Ibid , p. 126.

The State v Zia-ur-Rehman , PLD 1973 SC 49.

Ibid , p. 66.

Ibid , p. 69.

Ibid , p. 70.

Khan ( 2004 ), pp. 467–472.

Ibid , p. 555.

For a discussion of the election results see Khan, ibid , pp. 556–562.

Ibid , pp. 563–564.

Ibid , p. 571.

Laws (Continuance in Force) Order, 1977, CMLA Order I.

Begum Nusrat Bhutto v Chief of Army Staff and Federation of Pakistan , PLD 1977 SC 657, p. 704.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 581.

Begum Nusrat Bhutto v Chief of Army Staff and Federation of Pakistan , PLD 1977 SC 657.

Ibid , p. 692.

Ibid , pp. 692–693.

Ibid, p. 721.

Ibid , p. 694.

Ibid , pp. 698, 702.

Ibid , p. 702.

Ibid , p. 703.

Ibid , p. 705.

Ibid , p. 716.

Newberg ( 1995 ), p. 169.

Ibid , pp. 163, 168.

Ibid , p. 168.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 599.

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto v The State , PLD 1979 SC 38.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 615.

Ibid , p. 617.

Ibid , p. 624.

Ibid , pp. 627–628.

Ibid , pp. 640–641. For a detailed analysis of the role of Islam in the legal system of Pakistan see Lau ( 2006 ).

Khan ( 2004 ), pp. 635–636.

Ibid , pp. 637–638.

Ibid , pp. 661–666.

Provisional Constitutional Order, 1981, CMLA Order 1.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 647.

Ibid , p. 648.

Ibid , p. 649.

Ibid , p. 675.

Ibid , p. 697.

Ibid , p. 722.

Khawaja Ahmad Tariq Rahman v The Federation of Pakistan , PLD 1992 SC 646.

Ibid , p. 666 per Justice Shafiur Rahman.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 734.

Ibid , p. 752.

Muhammad Nawaz Sharif v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 1993 SC 473.

Khan ( 2004 ), pp. 755–758.

Ibid , p. 793.

Ibid , pp. 793–797.

Ibid , p. 827.

Ibid , p. 833.

Ibid , p. 924; Talbot ( 2009 ), p. 392.

Khan ( 2004 ), pp. 926–933; the Kargil war involved the withdrawal of Pakistan’s forces to the Kashmir line of control and was perceived by Pakistan as an international embarrassment. General Pervez Musharraf’s address to the nation of 13 October 1999 reported that the country faced “turmoil and uncertainty” from the destruction of the nation’s institutions and economy and that the armed forces were the “last remaining viable institution” that was obligated to provide the country with “stability, unity and integrity”: Musharraf ( 1999 ).

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 783.

Ibid , pp. 784–785.

Al-Jehad Trust v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 1996 SC 324.

Ibid , p. 389.

Ibid , pp. 389, 399, 404.

Ibid , p. 365.

Ibid , p. 408.

Ibid , p. 366.

Ibid , p. 419.

Ibid , p. 428.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 787.

Ibid , p. 788.

Ibid , p. 787.

Ibid , pp. 823–824.

Ibid , p. 825.

Ibid , pp. 825–826.

Ibid , p. 826.

Ibid , p. 829.

Asad Ali v Federation , PLD 1998 SC 161.

Al-Jehad Trust v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 1996 SC 324. Khan ( 2004 ), p. 830.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 831.

Ibid , pp. 802–803.

Khan Asfandyar Wali v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2001 SC 607.

Ibid , paras 164–165.

For a comparative discussion of emergency powers in India and Pakistan see Kalhan ( 2010 ).

Mahmud ( 1993 ). See also Mahmud ( 1994 ).

Mahmud ( 1993 ), pp. 1302–1305.

India’s Supreme Court developed innovative constitutional doctrines during this time, such as the basic structure doctrine, which holds that certain basic features of the Constitution cannot be changed even though the process of constitutional amendment: Kesavananda Bharati v The State of Kerala , AIR 1973 SC 1461.

Section 2(1) of the Provisional Constitutional Order 1999, 2-10/99 Min. I. stated that “[n]otwithstanding the abeyance of the provisions of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, hereinafter referred to as the Constitution, Pakistan shall, subject to this Order and any other Orders made by the Chief Executive, be governed, as nearly as may be, in accordance with the Constitution.” President Muhammad Rafiq Tarar continued as President: Khan ( 2004 ), p. 933.

Section 7 of the Provisional Constitutional Order 1999, 2-10/99 Min. I.

Oath of Office (Judges) Order 2000; see Khan ( 2004 ), pp. 934–935.

Khan ( 2004 ), p. 935.

Qureshi ( 2010 ), p. 491.

Zafar Ali Shah v General Pervez Musharraf, Chief Executive of Pakistan, PLD 2000 SC 869.

Ibid . Although presumably new judges would take the place of those who refused to take a new oath to keep the courts operational, as happened with the six judges of the Supreme Court who refused to take the fresh oath.

The Times of India ( 2008 ).

Legal Framework Order, 2002, Chief Executive’s Order No 24 of 2002. Note that Musharraf had dismissed President Rafiq Tarar and appointed himself President on 20 June 2001: Qureshi ( 2010 ), p. 492.

Qazi Hussain Ahmed’s Case , PLD 2002 SC 853.

Ibid , para 61.

Legal Framework Order, 2002, Chief Executive’s Order No 24 of 2002.

Constitutional Petition No 36 of 2002 , para 7.

Constitutional Petitions Nos 13, 14, 39 & 40 of 2004 & 2 of 2005 .

Ibid , para 30.

Ibid, para 40.

Supreme Court Bar Association v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2002 SC 939.

Ibid , p. 981.

Ibid , pp. 981–982.

Ibid , p. 983.

Ibid , p. 987.

Huq ( 2003 –2004), p. 32.

Talbot ( 2009 ), pp. 417–418.

United Nations Human Rights Council ( 2008 ), para 233.

Ibid , para 234.

Constitutional Petition No 21 of 2007 , paras 70, 102.

Ibid , para 54.

Ibid , para 55.

Ibid , paras 57, 59.

Ibid , paras 122, 134.

Ibid , para 157.

Ibid , para 198.

Ibid , para 279 per Justice Muhammad Nawaz Abbasi.

Talbot ( 2009 ), pp. 419–420.

Provisional Constitutional Order No 1 of 2007 (amended 15 November 2007).

Harvard Law Review Notes ( 2010 ), p. 1715.

Ibid , pp. 1716–1717.

Ibid , p. 1719.

Ibid , p. 1720.

Ibid , p. 1725.

Talbot ( 2009 ), p. 428.

Ibid , p. 429.

Ibid , p. 432.

Sindh High Court Bar v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2009 SC 789 (short order), PLD 2009 SC 879 (full reasons).

Sindh High Court Bar v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2009 SC 789, p. 799.

Ibid , pp. 799–800.

Sindh High Court Bar v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2009 SC 789, p. 800.

Ibid , p. 802.

Ibid , pp. 801–802.

Ibid , pp. 800–801.

Ibid , p. 804.

Ibid , pp. 804–805.

Constitution (Seventeenth Amendment) Act, 2003, 3.

Constitution (Eighteenth Amendment) Act, 2010, 10.

See e.g. , Waseem ( 2012 ), pp. 28–30 who notes that the ‘personal aura’ of the Chief Justice played a role in shaping the direction of the court in looking outward instead of a needed inward focus to improve the functioning of the justice system. See also an illuminating analysis by Kalhan ( 2013 ) who argues that the judiciary in Pakistan has placed the country in a ‘gray zone’ of institutional imbalance because of its unqualified view of judicial independence, which needs to achieve a new balance between autonomy and restraint. See also Ahmed ( 2015 ) for an account of judicial activism during this period and Cheema ( 2016 ) for an account that focuses on the nature and consequences of the politics of the Chaudhry Court.

Art. 184(3) of the Constitution provides the Supreme Court with the power to make an order if it considers that there is a question of public importance relating to any of the fundamental rights guaranteed in Chapter I of Part II of the Constitution.

Ghias ( 2010 ).

Ibid , p. 999 suggests that this may have resulted from judicial exchanges between Pakistan and India.

Alam ( 2008 ), p. 2, see generally Menski et al. ( 2000 ), Khan ( 2011 ), and Khan (Public Interest Litigation) ( 2015b ).

Alam ( 2008 ), p. 2.

Ibid , p. 3 notes the potential influence of the public interest model developed by the Indian Supreme Court.

Benazir Bhutto v President of Pakistan , PLD 1988 SC 388.

Ibid , pp. 416, 488, cited in Alam ( 2008 ), p. 2 who refers to a quote from the former Chief Justice Ajmal Miam who describes the adversarial system as an “inherited evil” as it prevents large groups of persons from obtaining constitutional justice.

Alam ( 2008 ), pp. 8–9.

Alam ( 2008 ), p. 5 highlights the case of M. Ismail Qureshi v M. Awais Qasim , 1993 SCMR 1781, where the Supreme Court converted private litigation into public interest litigation, inviting and hearing from a wide range of stakeholders.

Supreme Court of Pakistan ( 2014b ).

Supreme Court of Pakistan ( 2011 ), p. 129.

Supreme Court of Pakistan ( 2011 ), p. 129; Hussain ( 2011 ), p. 15 notes that legislative reform was brought about through the system in relation to the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1998, 19 the Prohibition of Smoking and Protection of Non Smokers Health Ordinance, 2002, F. No. 2(1)/2002-Pub., the Prohibition of Kite Flying (Amendment) Act, 2009, 14 and the Human Organs and Tissues Act, 2010, 6 among others.

Hussain ( 2011 ), p. 15.

Ghias ( 2010 ), pp. 991–996.

Dharshan Masih’s Case , PLD 1990 SC 513.

See e.g., Suo Motu Case No 14 of 2009 , an action based on a press clipping in the Daily News about land dealings.

Ghias ( 2010 ), p. 995.

Supreme Court of Pakistan ( 2012 ).

After visiting Pakistan in 2012, Special Rapporteur Gabriela Knaul stated that she commended “the use of inherent powers of the Supreme Court in recent cases related to gross human rights violations” although she called for clear criteria on the use of suo motu : Dawn ( 2012d ).

Hussain ( 2011 ).

Alam ( 2008 ), pp. 4–5.

Ibid , pp. 12–13.

Ghias ( 2010 ), p. 992, see Saad Mazhar v Capital Development Authority , 2005 SCMR 1973.

Ghias ( 2010 ), p. 993.

Ibid , see Maulvi Iqbal Haider v Capital Development Authority, PLD 2006 SC 394.

Ghias ( 2010 ), pp. 993–994.

Constitutional Petition No 9 of 2006 & Civil Petition Nos 345 & 394 of 2006 .

Ibid ; Ghias ( 2010 ), pp. 994–995.

Nadeem Ahmed v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2010 SC 1165.

See Siddique ( 2010 ) for a discussion of the Eighteenth Amendment leading up to the case.

Nadeem Ahmed v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2010 SC 1165, p. 1180; Art. 239(5). The Supreme Court itself has held that it did not have the power to look at the substance of constitutional amendments in Constitutional Petitions Nos 13, 14, 39 & 40 of 2004 & 2 of 2005 .

Nadeem Ahmed v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2010 SC 1165, p. 1180.

Ibid , p. 1181.

Ibid , p. 1182.

Nadeem Ahmed v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2010 SC 1165, pp. 1183–1184. The decision has been criticised by commentators on the basis that it invokes judicial independence in a case where the process of the commission is simply a matter of mechanics not principle and that the judiciary left little scope for parliamentary contributions: Sattar ( 2012 ), pp. 85–86.

19th Amendment Draft (2010).

Munir Hussain Bhatti v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2011 SC 407.

Ibid , p. 443.

Ibid , pp. 444–445.

Ibid , p. 446.

Rizvi (2015). See also Zafar Ali Shah v General Pervez Musharraf, Chief Executive of Pakistan, PLD 2000 SC 869, discussed above.

Constitutional Petition No 12 of 2010, etc. , p. 901.

Iqbal ( 2011 ).

See Suo Moto Action Regarding Death of more than 90 Heart Patients under Treatment in Punjab Institute of Cardiology on Account of Spurious Drugs , in which suo motu action was taken in relation to the “death of more than 90 heart patients under treatment in Punjab Institute of Cardiology on account of spurious drugs”. It is not clear from the judgment itself on what legal grounds the suo motu action was initiated although suo motu is seen as connected to fundamental rights: see Art. 184(3).

The Nation ( 2012 ).

CMA Nos 4343, 5436 and 5869 of 2014 in SMC No 1 of 2005 .

CMA No 3221/2012 in SMC No 25/2009 , para 1.

Supreme Court of Pakistan (2015).

Dawn ( 2012a ).

Nizami ( 2012 ).

Suo Motu Action Regarding Allegation of Business Deal between Malik Riaz Hussain and Dr. Arslan Iftikhar Attempting to Influence the Judicial Process , para 6.

Dawn ( 2011b ).

Dawn ( 2011c ).

Dawn ( 2012d ).

United Nations General Assembly ( 2013 ), pp. 14–15.

Dawn ( 2012b ).

National Reconciliation Ordinance (2007).

Discussed in Muhammad Azhar Siddique v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2012 SC 774, pp. 794–795.

Ibid , p. 795.

Quoted ibid , p. 798.

Art. 63(2).

Muhammad Azhar Siddique v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2012 SC 774.

Ibid , p. 807.

Ibid , p. 811.

Ibid , p. 817.

Walsh ( 2012 ).

Baz Muhammad Kakar v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2012 SC 866.

Ibid , p. 887.

Khan (Revokes) ( 2015a ).

CMA No 592-K/13 in SMC No 16 of 2011, etc. , para 3.

Ibid , paras 8, 10.

Dawn ( 2012c ).

The News ( 2014 ).

Constitutional Petition No 9 of 2014 .

Ibid , para 2.

Constitution (Twenty-First Amendment) Act, 2015, 1.

Shapiro ( 1986 ), p. 32.

Reference No 1 of 2012 , PLD 2013 SC 279.

Ibid , para 32.

Sh. Riaz-Ul-Haq v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2013 SC 501.

Ibid , para 42.

Omer ( 2016 ).

Dossani Travels Pvt Ltd v Messrs Travels Shop Pvt Ltd , PLD 2014 SC 1.

Ibid , para 26.

Ibid , para 45.

Objectives Resolution (1949), Annex to the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

Ibid , p. 1180.

See also Asma Jilani v Government of the Punjab, PLD 1972 SC 139 (no privative clause could prevent the Supreme Court from deciding a legal controversy argued before it); The State v Zia-ur-Rehman, PLD 1973 SC 49 (Supreme Court holds the power to interpret and apply any provision of the Constitution including jurisdiction-limiting terms); Begum Nusrat Bhutto v Chief of Army Staff and Federation of Pakistan, PLD 1977 SC 657 (Supreme Court held the jurisdiction to adjudicate upon the legal validity of government acts notwithstanding privative clauses of the new legal order); Zafar Ali Shah v General Pervez Musharraf, Chief Executive of Pakistan, PLD 2000 SC 869 (Supreme Court retained its review powers despite a privative clause); Constitutional Petition No 21 of 2007 (constitutional privative clause could not immunise acts done in bad faith or without legal jurisdiction).

See e.g., Supreme Court Bar Association v Federation of Pakistan, PLD 2002 SC 939 and Sindh High Court Bar v Federation of Pakistan, PLD 2009 SC 789 (short order), PLD 2009 SC 879 (full reasons) respectively.

See, e.g., Siddiqi ( 2015 ), where the author writes that “the challenge for any court remains a balancing act of being powerful but accountable”.

Constitutional Petition No 21 of 2007 .

See Dawn ( 2011d ).

Haider ( 2015 ).

For an outline of factors that can reduce or maintain judicial independence in dominant party systems see Tushnet ( 2015 ).

Walsh ( 2013 ).

Supreme Court of Pakistan ( 2014a ).

Federation of Pakistan v Moulvi Tamizuddin Khan , PLD 1955 FC 240.

Although this approach has been criticised, particularly in the context of ruling on the legal validity of military intervention: see, e.g. , Mahmud ( 1993 ) and Mahmud ( 1994 ).

Dawn ( 2013 ).

Democracy Reporting International ( 2011 ), p. 2.

Aqil Shah writes that “military organizational choices are more decisively shaped by the extent to which the military believes in the legitimacy of democratic institutions, including the constitution”: Shah ( 2014 ), p. 258.

Dawn ( 2012e ).

Siddiqi ( 2015 ). See also an analysis of the Supreme Court following the Lawyers’ Movement in Siddique ( 2015 ).

United Nations General Assembly ( 2013 ).

Sindh High Court Bar v Federation of Pakistan , PLD 2009 SC 789, pp. 799–800.

Abbasi A (2012) Rs 8,500 bn corruption mars Gilani tenure: transparency. Geo News. Available at https://www.geo.tv/latest/39122-rs-8-500-bn-corruption-mars-gilani-tenure-transparency . Accessed 2 Sept 2016

Ahmed F (1998) Ethnicity and politics in Pakistan. Oxford University Press, Karachi

Google Scholar

Ahmed S (2015) Supremely fallible? A debate on judicial restraint and activism in Pakistan. Vienna J Int Const Law 9:213

Akhtar RS (2000) Media, religion, and politics in Pakistan. Oxford University Press, Karachi

Al Jazeera (2010) Bangladesh sets up war crimes court. Al Jazeera. Available at http://www.aljazeera.com/news/asia/2010/03/2010325151839747356.html . Accessed 3 Sept 2016

Alam AR (2008) Public interest litigation and the role of the judiciary. Available at the Supreme Court of Pakistan http://www.supremecourt.gov.pk/ijc/Articles/17/2.pdf . Accessed 3 Sept 2016

Cheema MH (2016) The ‘Chaudhry court’: deconstructing the ‘judicialization of politics’ in Pakistan. Wash J Int Law 25:447

Cloughley B (2006) A history of the Pakistan army: wars and insurrections. Oxford University Press, Karachi

Cotran E, Sherif AO (eds) (1999) Democracy, the rule of law and Islam. Kluwer Law International, London

Council of Europe (1953) European Convention on Human Rights

Dawn (2011a) Letter of complaint against judges. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/664155/letter-of-complaint-against-judges . Accessed 2 Sept 2016

Dawn (2011b) SC exceeding limits of suo motu rules: ICJ. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/659509/sc-exceeding-limits-of-suo-motu-rules-icj . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Dawn (2011c) SC reply to ICJ: rules exist for suo motu cases. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/659835/sc-reply-to-icj-rules-exist-for-suo-motu-cases . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Dawn (2011d) Suo motu: Pakistan’s chemotherapy? Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/655910/suo-motu-pakistans-chemotherapy . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Dawn (2012a) Owners refuse to reduce rate: KP sees closure of CNG stations. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/761442/owners-refuse-to-reduce-rate-kp-sees-closure-of-cng-stations . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Dawn (2012b) SC reserves right to take notice of any issue: CJ. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/764265/sc-reserves-right-to-take-notice-of-any-issue-cj . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Dawn (2012c) Supremacy of parliament a misconception, says CJ. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/732466/supremacy-of-parliament-a-misconception-says-cj . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Dawn (2012d) UN Rapporteur calls for clear criteria for suo motu action. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/722339/un-rapporteur-calls-for-clear-criteria-for-suo-motu-action . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Dawn (2012e) Yousuf Raza Gilani is sent packing. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/727782/speaker-ruling-case-sc-resumes-hearing-2 . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Dawn (2013) 5 pc people hold 64pc of Pakistan's farmland, moot told. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/1048573 . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Democracy Reporting International (2011) Pakistan’s 2013 elections: testing the political climate and the democratisation process

Desai M, Ahsan A (2005) Divided by democracy. Roli Books, London

Ghias SA (2010) Miscarriage of chief justice: judicial power and the legal complex in Pakistan under Musharraf. Law & Social Inq 35:985

Haider I (2015) Senate adopts resolution seeking laws to review suo moto decisions. Dawn. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/1206941 . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Harvard Law Review (2010) Notes: The Pakistani lawyers’ movement and the popular currency of judicial power. Harv Law Rev 123:1705

Huq AZ (2003–2004) Mechanisms of political capture in Pakistan’s superior courts. Yearb Islamic Middle East Law 10:21

Hussain F (2011) The judicial system of Pakistan. Available at the Supreme Court of Pakistan http://supremecourt.gov.pk/web/user_files/File/thejudicialsystemofPakistan.pdf . Accessed 2 Sept 2016

Iqbal N (2011) Suo motu notice taken of railway affairs: officers’ salary to be seized if pensioners not paid: SC. Dawn. Available at http://www.dawn.com/news/669677/suo-motu-notice-taken-of-railway-affairs-officers-salary-to-be-seized-if-pensioners-not-paid-sc . Accessed 4 Sept 2016

Iqbal K (2015) The rule of law reform and judicial education in Pakistan. Eur J Law Reform 17:47

Jinnah MA (1947) Presidential address to the constituent assembly of Pakistan. Available at http://www.pakistani.org/pakistan/legislation/constituent_address_11aug1947.html . Accessed 2 Sept 2016

Kalhan A (2010) Constitution and ‘extraconstitution’: emergency powers in post-colonial India and Pakistan. In: Ramraj VV, Thirvengadam AK (eds) Emergency powers in Asia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kalhan A (2013) ‘Gray zone’ constitutionalism and the dilemma of judicial independence in Pakistan. Vanderbilt J Transl Law 46:1

Kāẓmī MR (2009) A concise history of Pakistan. Oxford University Press, Karachi

Kelsen H (1945) General theory of law and state. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Kennedy CH (1996) Islamization of laws and economy: case studies on Pakistan. Institute of Policy Studies, Washington

Khan H (2004) Constitutional and political history of Pakistan. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Khan MS (2011) The politics of public interest litigation in Pakistan in the 1990s. Soc Sci Policy Bull 2:2

Khan H (2012) The last defender of constitutional reason? Pakistan’s embattled Supreme Court. In: Grote R, Roder TJ (eds) Constitutionalism in Islamic countries: between upheaval and continuity. Oxford University Press, Oxford