An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Why is school leadership key to transforming education? Structural and cultural assumptions for quality education in diverse contexts

Monica mincu.

1 Department of Philosophy and Educational Sciences, University of Turin, Palazzo Nuovo, Via Sant’Ottavio, 20, 10124 Torino, TO Italy

2 Institute of Education, UCL, Centre for Educational Leadership, London, United Kingdom

Failing to recognize the role of leaders in quality and equitable schooling is unfortunate and must be redressed. Leadership is fundamentally about organized agency and collective vision, not managerialism, since it is an organizational quality, not merely a positionality attribute. Most important, if change is to be systemic and transformative, it cannot occur uniquely at the individual teachers’ level. School organization is fundamental to circulating and consolidating new innovative actions, cognitive schemes, and behaviors in coherent collective practices. This article engages with the relevance of governance patterns, school organization, and wider cultural and pedagogical factors that shape various leadership configurations. It formulates several assumptions that clarify the importance of leadership in any organized change. The way teachers act and represent their reality is strongly influenced by the architecture of their organization, while their ability to act with agency is directly linked to the existence of flat or prominent hierarchies, both potentially problematic for deep and systemic change. A hierarchical imposition from above as well as a lack of leadership vision in fragmented school cultures cannot determine any transformation.

In recent years, transformation has emerged as a high priority in key policy documents (OECD, 2015 , 2020a , 2020b ; Paterson et al., 2018 ; UNESCO, 2021 ) and been recognized as a major pillar on which the very future of education is based. A galvanized international scene has put transformation at the top of the agenda. One reason is found in the recent Covid-19 emergency and the need to recover, and possibly to “build back better”. Other reasons are longer-term and relate to dissatisfaction with the quality of education in many parts of the world. Major international agencies have been directly involved in reform and have variously endorsed “educational planning” (e.g., Carron et al., 2010 ), systemic reform in highly centralized countries, school autonomy (framed as school-based management or decentralization), systemic adjustment and restructuring (e.g., Carnoy, 1998 ; Samoff, 1999 ), and accountability (Anderson, 2005 ), as well as capacity building and development (De Grauwe, 2009 ). However, in practice, only segments of reforms have been enacted, focusing on one aspect of the school system while neglecting others, without considering the larger governance and school architecture, and local pedagogical cultures. Some agencies have also expressed a renewed interest in innovation and the possibility to measure it (Vincent-Lancrin et al., 2019 ), from a rather managerial perspective.

The transformation of education is a trendy movement nowadays, with the potential to generate lasting change through wide-reaching actions, not just stylistically or in local projects. Transformation of this kind will occur when structural and organizational conditions are in place in a range of different settings. When this happens, transformation as a revamped concept of change can be wholeheartedly embraced. Nonetheless, both academic and development-oriented NGO research has long dedicated itself to and learned from systemic change, improvement, and reform, based on what have been defined as effective practices (Ko & Sammons, 2016 ; Townsend, 2007 ). The school effectiveness findings are typically transversal principles of what has proved valuable despite contextual variation, whilst noting the local variability of such principles (Teddlie & Stringfield, 2017 ) especially in low and middle income countries (Moore, 2022 ) and even in similar areas of education development (Boonen et al., 2013 ; Palardy & Rumberger, 2008 ). Some variability often occurs between consolidated and less consolidated school systems. School improvement has been based on scholars’ findings on school effectiveness, as these two areas can merge up to a certain point (Creemers & Reezigt, 2005 ; Stoll & Fink, 1996 ). Reform at the top and improvement at the ground level have long been trialed in different national and organizational settings and with different school populations, with the aim of establishing generalizability or local variation. Quality teaching (Bowe & Gore, 2016 ; Darling-Hammond, 2021 ; Hattie, 2009 ) or teachers (Hanushek, 2010 , 2014 ; Mincu, 2015 ; Akiba & LeTendre, 2017 ), as well as equitable effective practices (Sammons, 2010 ) have also been classic research topics that have emerged center-stage in any change project.

In order for quality-promoting endeavors such as change, improvement, and reform to produce a transformed education, several assumptions are indispensable: (a) recognize the larger school and organizational context as crucial, alongside school architecture and processes, (b) define what quality education means across a variety of country contexts and with regard to specific structural arrangements and pedagogical cultures, (c) distinguish the degree and type of autonomy for schools and teachers, and estimate the effectiveness of their mixed interactions, (d) understand and cope from a change perspective within a variety of school cultures, (e) recognize the structural limitations faced by school leadership, as well as the margins to produce local, gradual improvement that can pave the way to radical transformation, and (f) start any significant change at the school level, in the interaction of leaders and teachers.

What is school leadership and how can it bring about change? On the one hand, leadership is about a vision of change, collectively shaped and supported. In this sense, radical change—i.e., transformation—cannot occur without leaders and especially school leaders. In addition, an effective vision about a desired change grows from the interactions of the school actors and is stimulated and orchestrated by the school leadership. An imposition from above as well as a lack of leadership vision in fragmented school cultures cannot determine any transformation, nor its subsequent stability or growth, given that some grass roots changes happen accidentally, in limited school areas. In fact, if change is to be systemic and transformative, it cannot occur at the individual teachers’ level, as then it cannot be circulated and consolidated in stable, coherent collective practices. Action at the school level is fundamental for change to occur and last, as well as for individual teachers to be encouraged, supported, and rewarded for their innovative behavior. On the other hand, change is often conceptualized as a gradual process of a series of stages (Fullan, 2015 ; Kotter, 2012 ), carefully incorporating structural and cultural adjustments (Kools & Stoll, 2016 ). Transformation, a less orthodox and robust concept, incorporates the desire for more abrupt and radical change. It is imagined as a possibility to “leapfrog”. This desire to move rapidly forward resonates with the “window of opportunity” phase when big changes can occur more smoothly. However, at the school and even systemic level, complex changes resulting in net improvements are most often gradually prepared and stimulated, since any change is cultural in essence, and as such it needs time to occur. Another relevant aspect is related to leadership as an ingredient and quality, not just a positionality attribute. Both assumptions suggest the inevitability of its role to any change in education as an organized endeavor.

Larger contexts and school organizations are key in any transformation

Education does not occur in an organizational vacuum, since deschooling, mass home-schooling, or online-only paradigms are neither implemented nor envisioned. In addition, a concept of education exclusively posed in philosophical and theoretical terms, especially when aimed at transforming the status quo, neglects to take into account that schooling is enmeshed with different organizational and governance forms, at times in contradiction with its own theoretical bases. Most important, forms of sociality such as those sustained by schools have not declined in relevance but increased, in the aftermath of the global online experiment of the pandemic emergency. At the same time, improvements and even radical changes in education have been embraced and actively promoted in certain parts of the world. For instance, in Norway, renewed weekly timetables are in place, allowing for deep learning as well as better integration with virtual knowledge in high-stakes exams. One should not forget that most pupils around the world are educated in environments displaying significant structural convergences across countries, despite locally diverse values. Such teaching-oriented settings are characterized by the centrality of the adult as teacher, and most often by textbook-based education. The organizational arrangements are linear, based on daily subjects and teachers’ contractual time, mainly dedicated to teaching activities (the stavka system, see Steiner-Khamsi, 2016 , 2020 ) or to ad hoc self-help actions in extreme emergency contexts. Linked to these, school cultures can be both hierarchical (rules are delivered “from above”) and fragmented, since class teachers may be left to themselves without adequate professional support. Whilst the reality is nuanced and school typologies are in any case sociological abstractions, most systems can still be described as basically centralized or decentralized, depending on the level of autonomy granted to schools or local authorities. The larger school contexts as well as the local ones are even today very diverse in these two cases, despite a global increase in diversified combinations of centralization of some aspects and decentralization of others. What Archer ( 1979 ) theorized in her landmark work is still a key valid explanation of how school organizations usually operate and change. With renewed categories, a centralized system is largely characterized by “hierarchies”, real or perceived, and less by “networks and markets”, whilst in the case of decentralized systems, the opposite is true. The same differences can be highlighted in more comprehensive or selective school types, whose visions and ways of functioning are coherent with their structural patterns and influence, and in turn, with how leaders perceive their role and mission.

In terms of leadership, differing configurations will bring differing consequences. Centralized countries with weak school autonomy approach the role of school leaders in a rather formalist way: as primus inter pares or as administrative and legal head. In these settings, the intermediate level is also very weak and largely based on ad hoc tasks. Flat organizations may not support leadership as an essential element in the school’s operational life, and instead focus primarily on teaching, which is mainly viewed as an individual endeavor. School organizations at odds with leadership as a system quality, both in organizational and instructional terms, often exhibit forms of fragmentation (Mincu & Romiti, 2022 ), even in societies that may share a collectivistic or communitarian ethos, such as in East Asia. In countries with significant school autonomy, leadership structures are more manifestly in place, given the increased tasks performed by schools. Often, an excess of hierarchical leadership is a major negative outcome. However, the school context can be characterized by mixed combinations of types of governance (hierarchies, networks, markets) (Mincu & Davies, 2019 ; Mincu & Liu, 2022 ), which have a significant influence on the way leadership is oriented and how it accomplishes its visionary, organizational, and instructional functions within the school and in relation to society. School leadership is both a processual quality and a positional trait, and thus it can be variously performed in high autonomy school systems. In the case of centralized arrangements, it can be much harder to identify leadership as process where there is just some form of leadership positionality: a legal school head or the existence of subject-matter departments. School contexts and organizations around the world are also diverse in terms of leadership configurations and roles: some schools may share the same leader (Italy), some may not provide many leadership positions at all (India), and others may specify a headship position which does not in fact offer any leadership or cohesion in organizational and pedagogical matters. Indeed, leadership may be entirely missing from certain school systems.

To summarize, the way teachers act and represent their reality is strongly influenced by the architecture of their organization, along with the quality, direction, and margins of power that can be exerted by leadership at the school and intermediate levels. Nevertheless, schools are large organizations, and as such a certain amount of alignment and direction is needed, which is what leadership provides.

The autonomy of schools and that of teachers are not mutually exclusive

Closely related to the first assumption, for a functional and dynamic school organization, a certain amount of school autonomy is required to adequately balance teachers’ autonomy. In high school autonomy systems, there is a tendency to assume that teachers’ autonomy is quite reduced, and this is certainly the case if the education model is accountability-oriented and leadership is hierarchical. In less autonomous systems, huge resistance to instill more autonomy at the school level is usually deployed—for example, in strongly unionist cultures, which aim to extend and expand teachers’ independence. This translates into quite radical teachers’ autonomy on pedagogical matters, as is the case in certain European school systems (Mincu & Granata, 2021 ).

An excess of teachers’ autonomy is detrimental to coherence and alignment at the school level and affects both quality and equity. The metaphors of teachers in their classes as eggs in their egg crates or lions behind closed doors, in the words of a ministry official in Italy, are particularly telling about flat, non-collaborative structures. The idea that high teacher autonomy may automatically support collegiality in flat organizations is not supported by the reality on the ground in certain school systems. In sociological terms, any human organization requires a certain amount of hierarchy and collegiality. In fact, a certain quantity of school autonomy is beneficial in many ways and can enhance teachers’ agency: (a) it emphasizes the role of leaders, including the possibility for teachers to act with leadership, (b) it offers a direction that can be shared, (c) it stimulates people to come together in effective ways (communities of practice) whilst presenting the risk of some contrived collegiality, and (d) it encourages teachers to feel more supported in their own work and professional development.

In a nutshell, leadership’s margins of influence are shaped not only by overall system governance, but also by the amount of school autonomy they enjoy. In addition, the extent of organizational autonomy is directly linked to the existence of flat or prominent hierarchies, both potentially problematic for deep and systemic change.

School cultures converge and diverge in multiple ways within and across countries

Pedagogical transformation is about a change in cultural assumptions, which entails a slow process of cognitive and emotional modification that has to be supported beyond school walls by concerted social and economic actions. Structural change will not be successful without an adjustment in people’s cognitive schemes about their practices and values. How teachers conceive of teaching and learning, and of equitable and inclusive approaches, is not essentially a matter of “lack of training”, for which more preparation may be the solution. It is instead a matter of deep pedagogical beliefs, whose roots are shared and societal. How to discipline class misbehavior, for example, and even what inappropriate classroom behavior is, varies widely across societies: it denotes (generational at times) power distance, gender relations, assumptions about individuality and collectivistic entities, as well as merit recognition and social envy avoidance. For Hargreaves ( 1994 ), school culture is the result of the intertwining of attitudes such as individualism, collaboration, contrived collegiality, and “balkanization”, i.e., fragmentation of ethical goals. Stoll ( 2000 ) herself describes schools in terms of social cohesion and social control as traditional, welfarist, “hothouse”, or anomic. In contrast, for Hood ( 1998 ), there are four possible combinations of social cohesion and regulation: (a) fatalistic: compliance with rules but little cooperation to achieve results, (b) hierarchical (bureaucratic): social cohesion and cooperation and a rules-based approach, (c) individualist: fragmented approaches to organizing that require negotiation among various actors, and (d) egalitarian: very meaningful participation structures, highly participatory decision-making, a culture of peer support.

In reality, mixed combinations of two, three, or more types of cultures can be found and supported by a variety of factors within and beyond schools as organizations. Some Southern European realities, as well as some Eastern European systems, belong to the individualist typology: weak collaboration and weak hierarchy, given the absence of a teaching career structure with levels of preparation and strong autonomy of the individual teacher. Some aspects of institutional “fatalism” are present, because a certain culture of respect for rules nevertheless exists, and of egalitarianism of a rather formal type. In fact, while the collegial culture on a formal level may appear robust—given the presence of collegial bodies—in practice organizational coherence remains very weak. The reason lies in the fact that these bodies can also decide not to agree on any systemic solution and defer decisions to the individual teacher, since teacher autonomy is still the superior criterion governing informal culture in schools. In the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian school systems, for example, schools express more coherent and cohesive cultures that oscillate between very hierarchical and more participatory models, with more diffuse leadership (Seashore-Louis, 2015 ). Even though these latter school systems favor a mostly cohesive ethos, it is not uncommon to find fragmented and inconsistent schools with weak leadership.

As an example of how school cultures work, a culturally well-rooted premise that teachers “are all good” is very much at work in certain flat hierarchical or Confucian-oriented school cultures, meaning they are equally effective because morally oriented for the profession. This is, in fact, a convenient belief allowing those within it to oppose forms of evaluations (including between peers and in the wider community of parents and stakeholders) and to resist more school autonomy and cohesiveness measures that might be envisioned by school or system leadership. Whilst teachers may be reluctant to work together and observe each other (as in a lesson study format) in most countries, this may be particularly the case where teachers’ autonomy is quite radical, where collaboration and mentoring are not common practices, or where stimulated by school arrangements and work contracts (e.g., in Italy; see Mincu & Granata, 2021 ).

Another way to characterize pedagogical cultures is with reference to formalism (respect for rules and social distances, focus on adults’ role and transmissive pedagogies) or to progressivism (more egalitarian interactions and a focus on the learner and their way of acquiring and creating knowledge). There are many ways in which various school cultures can be appropriately characterized, offering plenty of nuances and details of social, economic, and cultural stratifications and contradictions: for instance, in certain East Asian contexts, there is a combination of Confucianism, socialist egalitarianism, and revised individualism of consumption or of possession, based on previous rural forms of it. However, along the lines of centralized/decentralized typologies that are still valid for describing school functioning and structures, the reality of countries around the world allows scholars to characterize school cultures as formalist versus progressivist. It is legitimate to do so in spite of the local nuances and anthropological cultures that may filter and support such pedagogies (Guthrie et al., 2015 ).

Any cultural change imposed from above or from abroad may be doomed to failure if the hardware is that of centralized systems and if school actors are not allowed to engage in a cultural exercise of adaptation, adequately supported with infrastructural measures. Whilst there is no single model, there are some pillars of good teaching and some key lessons about how to produce change. A major premise is that any change must reach the school level and be able to activate and energize its school actors. School systems may be distinguished therefore in terms of formalist/progressivist typologies, which is coherent with other types of systemic characteristics, including lack of leadership (be it hierarchically formalized, legally representative only, or peer-oriented) that may preclude any effort of cultural transformation.

Without leadership, individual teachers may act as a loosely connected group, without vision and motivation to produce an expected and socially praised change. The expectation to encourage reforms from the regional and district level, when not from the top, is purely utopian. Schools remain remote realities in such change models. Most systems in poorly resourced contexts are entangled in hierarchical school models and grounded in traditional power distance and colonial legacies. Without significant leadership processes stimulated by school principals at the very heart of such systems, cultural and new structural processes cannot be expected. To produce cultural change, the top leadership stratum must create the proper conditions, such as salaries, workload, and other incentives for training and knowledge dissemination; but action and cognitive schemes characterize the school level and teachers cannot be blamed for what they cannot do by themselves.

Defining quality for present times education in context

We cannot move toward possible futures without deeply understanding what good education can be in our present societies, in a variety of localities around the world. Research has long dedicated itself to the task of defining quality in education, particularly in the fields of school effectiveness and school improvement. Meta-research has become a bestseller scholarly genre (Hattie, 2009 ), and the drive toward evidence-based knowledge has been equally impressive, across universities, NGOs, and other major international players. Research studies distinguish between quality teachers (their attributes, amount of preparation, and years of experience) and teaching quality, based on dimensions of quality teaching that produce effective learning. Since structures and cultures can be effectively encapsulated in categories (centralized/autonomous, formalist/progressivist, etc.), quality teaching is also condensed (a) in key dimensions, for instance by Bowe and Gore ( 2016 ), subsuming further aspects, or (b) as rankings of most effective factors in terms of learning.

Mistrust of evidence-based and best-practice research traditions is justified when ready-made solutions are implemented without adaptations and the engagement of those involved. Even the adoption of South-South solutions can be ineffective at times (Chisholm & Steiner-Khamsi, 2008 ). Since problems in education are messy and “wicked” (Ritter & Webber, 1973 ) changes must be systemic and cultural.

Anderson and Mundy, 2014 proved that improvement solutions and practices in two groups of countries—developed and less developed—are very much convergent. Both developing and developed countries present a series of common challenges: the need for fewer top-down approaches, for instance, and for approaches less narrowly focused on the basics. Comparative evidence and perspectives on student learning in developing countries converge on a common cluster of instructional concepts and strategies: (a) learning as student-centered, differentiated, or personalized, associated with using low-cost teaching and learning materials in the language which students understand, and (b) the appropriate use of small group learning in addition to large group instruction. This enables regular diagnostic and formative assessment of student progress to guide instructional decision-making, clear directions, and checking student understanding of the purpose of learning activities. It also involves personalized feedback to students based on assessments of their learning, and explicit teaching of learning skills to strengthen students’ problem-solving competencies. With the possible exception of low-cost learning materials, these prescriptions for good teaching are consistent with international evidence about effective instruction (Anderson & Mundy, 2014 ). But quality teaching and teachers equally assume specific contextual meanings. For instance, Kumar and Wiseman ( 2021 ) indicate that traditional measures of quality (teacher preparation and credentials) are less relevant in India compared to non-traditional measures such as teachers’ absenteeism and their attitude/behavior toward their students.

Teachers alone cannot make a better school

Teachers and their actions at the classroom level are key to inspiring learning and students’ progress. Nonetheless, a misreported finding from an OECD ( 2010 ) study that “the quality of an education system can never exceed the quality of its teachers” is only partially correct. In fact, the full quotation said that the system’s quality cannot exceed the quality of its teachers and leaders. The incomplete quote mirrors a common misconception that teachers alone can and should improve the system. Instead, teachers are part of organizations, and as such they behave and respond to dynamics in place in those contexts, and not as individuals, or as a professional group, not even in the most unionized countries. The quality of a public service cannot be attributed solely to its members, but also to their organization and to specific choices made by its leadership, which is responsible for organizational vision and translating theories into action. Launching heartfelt calls for teachers to change their practices is both naive and sociologically inaccurate regarding how people act and behave in social organizations, such as schools. The presence of leadership as a processual and qualitative dimension at the school level also indicates the existence of the structures of school leadership teams and middle managers, in which leadership is robustly in place as positionality.

In this sense, the quote indicates the relevance of teachers’ work in carefully designed organizations, in which hierarchy and horizontal interactions of collaboration between peers are in a functional equilibrium. In other words, schools and teachers’ autonomy reciprocally reinforce one another.

Whenever teachers are required to act with leadership, autonomy, and innovation, the larger system and school culture should be carefully considered. Teachers cannot by themselves be directly responsible for systemic changes. National-level teams of experts cannot blame teachers for a lack of change when the necessary knowledge and resources are not cascaded effectively to the school level. As the end point of the chain of change, teachers cannot be accused for a lack of success and adequate culture to facilitate innovation when decision makers do not consider the school architecture and how leaders are prepared and ready to support a change in culture. This has been the case with reforms in less resourceful countries around the world, often in highly centralized systems, where more progressivist changes are expected from teachers in the absence of proper consideration of the school architecture, long-standing interactions with the school leaders, and the overall pedagogical culture. Unfair blame for these teachers is expressed at times by international or national teams of experts, unrealistically expecting individual teachers to produce significant structural and cultural changes, otherwise they play the part of “those who wait on a bus” for a change to happen. The possibility to develop, to act innovatively, and to be motivated for teaching depends largely on the organizational support received by teachers at the school level from their head teacher and the wider environment. Professional development is a key ingredient that impacts teacher quality (Cordingley, 2015 ), and its effectiveness and provision depends heavily on the school leadership. Without support from the larger school context and leadership, even the most autonomous teachers may not act with the necessary teaching quality that can make a difference, as clearly illustrated by TALIS 2020.

Leadership, as an organizational quality, is indispensable

The final assumption involves the idea that one cannot crudely distinguish between teachers and leaders, especially middle managers and more informal leaders. Obviously, there is a continuum between such roles: teachers themselves can act with agency and leadership, formally or informally, and head teachers may draw upon their experience as teachers.

Since schools are organizations and not collections of individuals, the field of school effectiveness and school improvement has incontrovertibly identified the influence of leadership as vital: “school leadership is second only to classroom teaching as an influence on pupil learning” (Leithwood et al., 2008 ). Through both organization and instructional vision (Day et al., 2016 ), effective leadership significantly enhances or diminishes the influence that individual teachers have in their classes. Regardless of cultural considerations, when teachers’ work is uncoordinated and fragmented, the overall effect in terms of learning and education cannot be amplified and adequately supported. A lack of coherence within organizations is unfavorable to more localized virtuous dynamics that may be diminished or suffocated.

Moreover, unjustified allegations of managerialism and the striking absence of this topic from key policy documents, including those of UNESCO ( 2021 ), should be highlighted. Whilst the “executive” components implicit in any leadership function must be in place in organizations enjoying wide autonomy, this does not necessarily translate into managerialism and quasi markets. It is indeed the larger school context that can make an autonomous school perform in a managerial way or simply, with broader margins of action, that can facilitate good use of teachers’ collective agency, as in some Scandinavian countries. In order to produce even modest change, let alone radical transformation, we must overcome the widely held misconception that leadership has to do with managerial tasks, competition, and effectiveness from a highly individualistic stance. Whilst this can be the case in certain country contexts and with particular disciplinary approaches, educational leadership does not simply overlap with managerialism as a technical ability. It is essentially about vision and collaboration around our global commons, as well as locally defined school goals.

School leadership is correctly identified as a key strategy to improve teaching and learning toward SDG4 (the Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action adopted by the World Education Forum 2015). A specific task assigned to school leadership is an increase in the supply of qualified teachers (UNESCO, 2016 ). At the same time, the need to transform schools is sometimes decoupled from the potential of school and system leadership to ensure such transformation. Failing to recognize the role of leaders in quality and equitable schooling must be rectified. A humanistic vision and a focus on the global public good cannot be at odds, programmatically, with a field dedicated to understanding how contemporary schools are organized and how they operate.

Conclusion: Leadership is about organized agency, not managerialism

Innovations in education are complex because they can often be incremental and less frequently radical, but some have the potential to be truly transformative. The more effective tend to be small micro-context innovations that diffuse “laterally” through networks of professionals and organizations but need facilitation and effective communication from above to be deep and long-lasting. They are never just technical or structural, but rather cultural and related to visions about education. In this context, leadership and leaders are crucial in a variety of aspects, but foremost in shaping a coherent organization and engaging collectively to clarify and make explicit key pedagogical and equity assumptions, which has a dramatic direct and indirect influence on the effectiveness of the school. Most significantly, school leadership at all levels is the starting point for the transformation of low-performing (and) disadvantaged schools.

We should not underestimate the impact that the larger political, social, and economic context has on schools and leaders around the world. A variety of autonomous schools can perform in a managerial way or simply make good use of teachers’ collective agency, and a variety of less autonomous organizations may dispose or not of a certain dose of organizational coherence and leadership (Keddie et al., 2022 ; Walker & Qian, 2020 ).

What has proved valuable in most contexts may not always be effective in every case; a balance has to be struck between cultural awareness related to pedagogies in contexts and lessons learned across cultural boundaries. Available universal solutions have to be pondered, and adaptations are always required. It can be the case that, in certain conditions, we borrow not only solutions but the problems they address, in the way these are rhetorically framed. However, since convergences occur in structures and cultures, problems may also converge across contexts. In addition, micro-changes occur fluidly at any time, but for transformation to emerge, we need to draw on the accumulated wisdom and the potential implicit in system and school leadership. Last but not least, the complexity lying at the heart of learning from others and from comparison should not be assumed to be insuperable.

is an associate professor in comparative education with the Department of Philosophy and Education, University of Turin, and a lecturer in educational leadership with the Institute of Education, University College, London. She has acted as a consultant with UNESCO and other major Italian NGOs. She engages with education politics and governance from a social change and equity perspective.

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Akiba M, LeTendre G. International handbook of teacher quality and policy. Routledge; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, J. A. (2005). Accountability in education . UNESCO IIPE.

- Anderson S, Mundy K. School improvement in developing countries: Experiences and lessons learned. Aga Khan Foundation Canada; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Archer M. Social origins of educational systems. Routledge; 1979. [ Google Scholar ]

- Boonen T, Van Damme J, Onghena P. Teacher effects on student achievement in first grade: Which aspects matter most? School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2013 doi: 10.1080/09243453.2013.778297. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowe J, Gore J. Reassembling teacher professional development: the case for Quality Teaching Rounds. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice. 2016; 23 (3):352–366. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carnoy M. Globalisation and educational restructuring. Melbourne Studies in Education. 1998; 39 (2):21–40. doi: 10.1080/17508489809556316. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carron, G., Mahshi, K., De Grauwe, A., Gay, D. (2010). Strategic planning. Organisational arrangements . UNESCO IIPE.

- Chisholm L, Steiner-Khamsi G. South-South transfer: Cooperation and unequal development in education. Teachers College Press; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cordingley P. The contribution of research to teachers’ professional learning and development. Oxford Review of Education. 2015 doi: 10.1080/03054985.2015.1020105. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Creemers B, Reezigt G. Linking school effectiveness and school improvement: The background and outline of the project School Effectiveness and School Improvement. An International Journal of Research, Policy and Practice. 2005; 16 (4):359–371. [ Google Scholar ]

- Darling-Hammond L. Defining teaching quality around the world. European Journal of Teacher Education. 2021 doi: 10.1080/02619768.2021.1919080. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Day C, Gu Q, Sammons P. The impact of leadership on student outcomes: How successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educational Administration Quarterly. 2016; 52 (2):221–258. doi: 10.1177/0013161X15616863. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- De Grauwe, A. (2009). Without capacity there is no development . UNESCO.

- Fullan M. The new meaning of educational change. Teachers College Press; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guthrie G, Tabulawa R, Schweisfurth M, Sarangapani P, Hugo W, Wedekind V. Child soldiers in the culture wars. Compare. 2015; 45 (4):635–654. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2015.1045748. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hanushek E. The difference is teacher quality. In: Weber K, editor. Waiting for "Superman": How we can save America’s failing public schools. Public Affairs; 2010. pp. 81–100. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hanushek E. Boosting teacher effectiveness. In: Finn CE, Sousa R, editors. What lies ahead for America's children and their schools. Hoover Institution Press; 2014. pp. 23–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hargreaves A. Changing teachers, changing times: Teachers’ work and culture in the postmodern age. Cassell; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hattie J. Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hood C. The art of the state, culture rhetoric and public management. Clarendon Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keddie A, MacDonald K, Blackmore J, Boyask R, Fitzgerald S, Gavin M, Heffernan A, Hursh D, McGrath-Champ S, Møller J, O'Neill J, Parding K, Salokangas M, Skerritt C, Stacey M, Thomson P, Wilkins A, Wilson R, Wylie C, Yoon E-S. What needs to happen for school autonomy to be mobilised to create more equitable public schools and systems of education? Australian Education Research. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s13384-022-00573-w. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ko, J. & Sammons, P. (2016). Effective teaching. Education Development Trust.

- Kools, M. & Stoll, L. (2016). What makes a school a learning organisation ? OECD.

- Kotter J. Leading change. Harvard Business Review Press; 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kumar P, Wiseman AW. Teacher quality and education policy in India: Understanding the relationship between teacher education, teacher effectiveness, and student outcomes. Routledge; 2021. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leithwood K, Harris A, Hopkins A. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership and Management. 2008; 28 (1):27–42. doi: 10.1080/13632430701800060. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mincu M. Teacher quality and school improvement: What is the role of research? Oxford Review of Education. 2015; 41 (2):253–269. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2015.1023013. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mincu M, Davies P. The governance of a school network and implications for Initial Teacher Education. Journal of Education Policy. 2019; 36 (3):436–453. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2019.1645360. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mincu, M. & Granata, A. (2021). Teachers’ informal leadership for equity in France and Italy during the first wave of the education emergency. Teachers and Teaching , Special Issue, 1–21.

- Mincu M, Liu M. The policy context in teacher education: Hierarchies, networks and markets in four countries. In: Tierny R, Rizvi F, editors. International Encyclopaedia in Education. Elsevier; 2022. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mincu M, Romiti S. Evidence informed practice in Italian education. In: Brown C, Malin J, editors. The Emerald international handbook of evidence-informed practice in education. Emerald; 2022. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore R. Variation, context, and inequality: comparing models of school effectiveness in two states in India. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2022 doi: 10.1080/09243453.2022.2089169. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- OECD (2010). PISA 2009. Results: What makes a school successful? Resources, policies and practices (Volume 4) . 10.1787/9789264091559-en

- OECD . Schooling redesigned. OECD; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- OECD (2020a). What students learn matters. Towards a 21st century curriculum . OECD.

- OECD (2020b). Back to the future of education: Four OECD scenarios for schooling, educational research and innovation . OECD.

- Palardy GJ, Rumberger RW. Teacher effectiveness in first grade: The importance of background qualifications, attitudes, and instructional practices for student learning. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 2008; 30 :111–140. doi: 10.3102/0162373708317680. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paterson A, Dumont H, Lafuente M, Law N. Understanding innovative pedagogies. OECD; 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rittel HW, Webber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences. 1973; 4 (2):155–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01405730. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sammons P. Equity and educational effectiveness. In: Peterson P, Baker E, McGaw B, editors. International encyclopedia of education. 3. Elsevier; 2010. pp. 51–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- Samoff J. Education sector analysis in Africa: Limited national control and even less national ownership. International Journal of Educational Development. 1999; 19 (4–5):249–272. doi: 10.1016/S0738-0593(99)00028-0. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seashore-Louis K. Linking leadership to learning: State, district and local effects. Nordic Journal in Educational Policy. 2015; 3 :7–15. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2016). Teach or perish: The stavka system and its impact on the quality of instruction. Voprosy obrazovaniya/Educational Studies Moscow , National Research University Higher School of Economics, 2, 14–39.

- Steiner-Khamsi G. Prefazione [Foreword] In: Mincu M, editor. Sistemi scolastici nel mondo globale. Mondadori; 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stoll L. School culture. Professional Development. 2000; 3 :9–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stoll L, Fink D. Changing our schools: Linking school effectiveness and school improvement. Open University Press; 1996. [ Google Scholar ]

- Teddlie C, Stringfield S. A differential analysis of effectiveness in middle and low socioeconomic status schools. The Journal of Classroom Interaction. 2017; 52 (1):15–24. [ Google Scholar ]

- Townsend T. International handbook of school effectiveness and improvement. Springer; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- UNESCO (2016). Incheon declaration and framework for action for the implementation for Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning. UNESCO.

- UNESCO (2021). Futures of education: Learning to become . UNESCO.

- Vincent-Lancrin, S., Urgel, J., Kar, S., & Jacotin, G. (2019). Measuring innovation in education: A journey to the future . OECD.

- Walker A, Qian H. Developing a model of instructional leadership in China. Compare. 2020; 52 (1):147–167. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2020.1747396. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, school leaders' perspectives on successful leadership: a mixed methods case study of a private school network in pakistan.

- 1 Department of Education, Forman Christian College, Lahore, Pakistan

- 2 Department of Teacher Education, University of Okara, Okara, Pakistan

- 3 Department of Educational Research and Assessment, University of Okara, Okara, Pakistan

Private school culture dominates the public-school culture in Pakistan. With no central regulating organization, private schools in the country autonomously construct their educational philosophy that underpins curriculum choice, pedagogic approaches, and school operations. In this perspective, there is an increasing inquisitiveness in the understanding of what determines a private school as a “successful” school. The researchers intend to understand the determinants of a successful private school and aim to explore the leadership behaviors of head teachers of such schools in Pakistan. The Beaconhouse School System (BSS), the largest private school system in Pakistan, took part in this case study. A sample of a total of 128 participants, comprising of teachers (n = 120), School Group Heads (SGH) (n = 4) and school head teachers (n = 4) of four most successful primary schools of BSS, was drawn to participate in this case study employing a mixed-methods design. Two survey instruments, Determinants of School Success (DSS) and Leadership Practice Index (LPI) were developed on a five-point Likert Scale and applied to identify four most successful primary schools of BSS. It was found that head teachers had established a whole-school approach towards students high achievement, promoted a culture of trust, commitment, shared vision, practiced distributed leadership and involved all stakeholders in creating a shared sense of direction for the school. Recommendations have been generated for improving the performance of school leaders.

Introduction

About one-third of school-going children in Pakistan attend private schooling ( Andrabi et al., 2013 ; Nguyen and Raju, 2014 ). The industry of Pakistan’s private schools largely comprises of institutions that are for-profit, autonomous, and unregulated by any central institution. Around two percent of average household income, in both rural and urban areas constitute the industry of private schooling consequently resulting in producing magnanimous annual gross income recorded in the academic year 2013—2014 up to four ninety-seven million ( Pakistan Education Statistics, 2014 ). The annual survey report of All Pakistan Private Schools Association (APPSA) presents a tentative number of private schools operating in Pakistan; there is no accurate number of institutions that can be categorized as a “Private School”. As of 2014, one hundred seventy-three thousand one hundred and ten private schools were operating nationwide, 56% of which were concentrated in one province, Punjab.

The history of private schooling in Pakistan goes back to the era of British Rule in the sub-continent. The first private school, Karachi Grammar School was established in 1847 in Karachi. In the 1990s, on account of the decentralization of primary education, there was a dramatic boom in the emergence of private primary schools across the country. The research proposes unsatisfactory service delivery in government schools as one of the factors for this boom ( Andrabi et al., 2008 ; Baig, 2011 ). Another often-stated reason is low operating costs and high revenue mainly due to low labor wages; private school teachers are paid less than government schoolteachers ( Baig, 2011 ; Andrabi et al., 2013 ). Lack of a standard pre-requisite level of education and professional training makes it easier to find teachers who are willing to work on low wages set by private schools. A third contributing factor is a mutual consensus by the local community to associate a necessary students higher achievement with private schooling. However, this assumption is not backed by authentic academic research.

Nonexistence of a central regulatory authority to ensure the standardized quality of service at private schools in Pakistan, service delivery decisions are directed by prevailing market trends and influenced by policymakers of individual schools ( Salfi, 2011 ). Private schools enjoy full autonomy to select school curriculum, pedagogical methods, staff training models and inclusion of society. Some wide-spread networks of school branches belonging to a school system practice standardized procedure across all branches. Research asserts that even at these large school networks the pre-requisites for selecting a head teacher are not standard and may be greatly compromised in some underdeveloped cities of Pakistan.

It has been repeatedly reported by researchers around the world that head teacher plays a vital role in determining the success of a school in terms of management, high teacher performance, positive students’ learning outcomes and social reputation in the community ( Böhlmark et al., 2016 ; Education Review Office, 2018 ; Felix-Otuorimuo, 2019 ; Leithwood et al., 2019 . Fullan (2001) has gone as far to conclude that, “Effective school leaders are key to large-scale, sustainable education reform” (p. 15). These arguments suggest the need to determine what factors and determinants contribute to a successful school leadership particularly in the context of a private school system in a country where the absence of central regulatory authority creates a situation of non-standardized quality of services that leads to a state of disorganized school management.

The Focus of the Research

International studies confirm a positive relationship between the role of head teacher and school success ( Haydon, 2007 ; Leithwood et al., 2006 ; Winton, 2013 ). In the case of Pakistan, the meaning of school success is relative and varies hugely from one school to another. Lack of standard prerequisites for the hiring of head teachers in the private education sector creates a troubling void in understanding the relationship between leadership qualities of head teachers and school success ( Iqbal, 2005 ). To avoid heterogeneity this research maintains its focus only on the largest private primary schools’ network the Beaconhouse School System (BSS).

The objective of this study is two-fold; to identify determinants of school success conceived by the largest private school network of Pakistan and to understand common leadership qualities of successful school head teachers. The synthesis of results determines the relationship between school heads and school success. The core research questions addressed in this study are:

1) What are the determinants of a successful school in the private sector of Pakistani schools?

2) What are school head teachers’ leadership qualities in successful private primary schools of BSS in the province of Punjab?

3) What are the common trends in the leadership qualities of these school head teachers?

Significance of the Research

Beaconhouse School System (BSS) is the largest and most wide-spread network of private schools in Pakistan contributing up to 38% to the total number of private primary school enrolment in the province of Punjab ( PES, 2014 ). It is the first school network in the country to set in-place a School Evaluation Unit (SEU) that carries out cyclical school evaluations to report periodic individual school performance in terms of “good” practices and areas for further development. However, these are internal documents and not to be used as a resource for sharing of good practices and remain a missed opportunity to draw descriptors of a successful BSS school in the context of Pakistan and to further identify the qualities of a good school leader. This research is an attempt to fill this gap by synthesizing this information to help Pakistan’s largest private schools network to learn from their success and to use findings to design targeted head teachers training programs.

This study concentrates in the primary school section due to the high impact the selected section has on the overall education standard in the region. BSS takes approximately 38% of primary school enrollment in Punjab through a range of their education products including The Educators, United Chartered Schools, and mainstream Beaconhouse Schools. The study has significant implications for the other networks of private schools in Pakistan for bringing reforms in school leadership programs. It can augment for establishing effective school leadership practices for the success of other schools in BSS and the schools of other networks in general. The study signifies to reduce a gap of quality school leadership between one of the most popular school networks in the country and public sector schools of the province of Punjab.

Methodology

This study employed a mixed methods research design using four schools working under the umbrella of the Beaconhouse School System. An in-depth case study was undertaken by using multiple sources of data collection, analysis, and interpretation ( Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004 ). In the quantitative standard, the researchers collected data from the selected teachers working in the four schools of BSS through two questionnaires; Determinants of School Success (DSS) and Leadership Practice Index (LPI) formulated on a five-point Likert scale. This was followed by in-depth semi-structured interviews with different stakeholders including the school head teachers and SGHs. This research process was accomplished within 3 weeks. The researchers employed a mixed-methods research approach to make the research findings more reliable, valid, and to minimize the level of bias by comparing sets of data by data triangulation and grasping an in-depth understanding of the case of BSS ( Gurr et al., 2005 ; Osseo-Asare et al., 2005 ).

Beaconhouse School System (BSS), the largest private school network operating in Pakistan with more than three hundred and seventy-five branches spread across the country, serves as the primary population and a case of study for this research. The school system was established in the province of Punjab in 1975 and it is now the largest school system of its type in the country catering to over two hundred forty-seven thousand students across Pakistan. Most of the students come from upper-middle-class families with a gross monthly household income between fifty thousand rupees up to three hundred thousand rupees ( Andrabi et al., 2013 ). BSS caters to modern educational needs and follows a customized curriculum influenced by the British and Scottish national curricula.

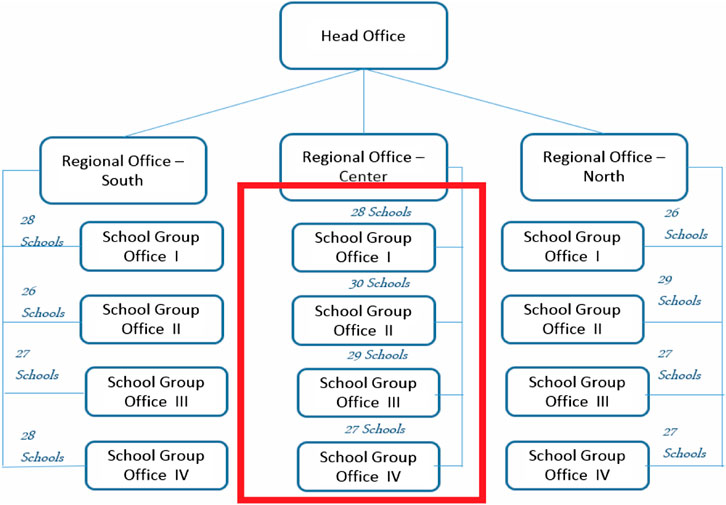

Organizational Setup

The network of BSS school branches is divided into three geographic regions namely Southern Region, Central Region and Northern Region. Policy planning, curriculum development, assessment development, and other related school management and teacher development issues are addressed at the Head Office which is situated in Lahore, Punjab. All three Regional Offices report to the Head Office. Academic and administrative support to school branches in each region is provided by four School Group Offices (SGOs). These SGOs report directly to Regional Directors (RD).

Note. The Figure 1 explains the division of regions and organizational structure and identifies the research population.

FIGURE 1 . Organizational Structure of the Beaconhouse School System and Research Population.

A total of fifty-seven primary school head teachers, four School Group Heads (SGHs), and two thousand eight hundred and fifty teachers comprised the overall population for this study.

Sample Size

The research is accomplished in two cycles using different sampling approaches, in the first cycle of research the Central Region was selected purposively due to the largest number of school branches operating in this region. All School Group Heads (SGHs) took part in the first cycle of research and identified one most successful primary school branch in their cluster therefore, following a subjective sampling technique. The second cycle of research was carried out at the identified branches. To maintain the anonymity of these school branches they will be referred to as School A, B, C and D. A total of one hundred and twenty teachers also participated in the second cycle of research.

Research Design

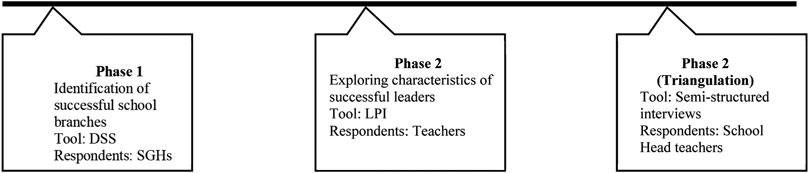

An explanatory mixed methods research design comprising of both quantitative and qualitative methods of research respectively was employed for an in-depth understanding of the case and to achieve the study objectives.

Research Instrument

Data were collected using a mixed-methods research design that includes: two questionnaires namely Determinants of School Success (DSS) and Leadership Practice Index (LPI) were formulated on a five-point Likert scale and combined with in-depth semi-structured interviews with different stakeholders including the school head teachers and SGHs. This study was carried out in a two-phase model, the first phase explored and reported determinants of school success as perceived by the senior leadership of the school system. The second phase of research investigated the leadership traits of effective school leaders at schools perceived as “successful” based on the outcome of research phase -1. Figure 2 illustrates the phases in research design.

FIGURE 2 . Research Design Phases.

There is a plethora of research struggling to find an answer to what constitutes a successful school. Some researchers have strongly linked it with elevated students learning outcomes ( Scheerens, 2004 ; Winton, 2013 ), others attempted to find the answer by increased reporting causes of school failure, for instance, Salmonowicz (2007) recognized fifteen conditions associated with unsuccessful schools including lack of clear focus, unaligned curricula, inadequate facilities, and ineffective instructional interventions. Edmonds (1982) offered a list of five variables correlated with school success, Lezotte (1991) evolved the list by adding two more variables: 1) instructional leadership, 2) clear vision and mission, 3) safe and orderly environment, 4) high expectations for students achievement, 5) continuous assessment of student achievement, 6) opportunity and time on task and, 7) positive home-school relations. The meaning of school success is contextual and existing research is yet to conclude a fixed list of variables that determine the success of a school.

DSS used in this research is based on five broad themes namely: positive outcomes for students, quality teaching and curriculum provision, effective leadership and school management, safe and positive school environment, quality assurance. All these variables are well supported by the existing research and have been extracted from the internal school evaluation framework of BSS. Twenty-five items inspired by Marzano Levels of School Effectiveness (2011) formulate the sub-categories of these domains. The response format on a five-point Likert scale for the items was, strongly agree = 5, agree = 4, neutral = 3, disagree = 2, strongly disagree = 1. The levels of school effectiveness suggested by Marzano (2011) fit well with the internal evaluation indicators of the high-performing school system of BSS. This method of research is new in the context of Pakistan however; evidence from internationally set-up research confirms Marzano levels of school effectiveness being utilized to study the long-term performance of schools in Oklahoma, United States (OSDE, 2011) and Ontario, Canada ( Louis et al., 2010 ). Researchers assert that Marzano’s levels of school effectiveness “Extends our understanding of the explanatory potential of research on school performance” ( Louis et al., 2010 , p.8).

In the second research cycle, Leadership Practice Index (LPI) was developed by the researchers to index successful leadership qualities. LPI comprised a five-point Likert scale and the responses were collected from teachers (n = 120) in terms of frequency of demonstration of a variety of leadership qualities by the school head teacher. The format was 0 = Never, 1 = Seldom, 2 = Often, 3 = Regularly, and 4 = Routine Practice. LPI constitutes twenty-eight performance indicators for effective leadership qualities under five primary domains: personal, professional, organizational, strategic and relational. The Evidence from large-scale school-based leadership research conducted in high-performing economies such as Canada ( Louis et al., 2010 ) and the United States ( Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006 ) assert that these domains breakdown the knowledge of role and impact of school leadership on instruction, school performance, and students learning outcomes.

During the second cycle of research, head teachers were interviewed using a semi-structured interview style. The interview guide was divided into six overarching categories: students achievement, teaching, and learning, instructional leadership, and management, establishing the direction for the school, social links with the community, and quality assurance. A total of four interviews were conducted during this study in a traditional modality; the average interview time was 47 minutes. Ethical and practical guidelines were shared and agreed with the interviewees and all interviews were recorded, and fully transcribed before inducing for data analysis.

Pilot Study

To ensure the internal reliability and clarity of items of DSS the researchers conducted a pilot study within the same research population. From the Southern Region of the same organization School Group Heads (n = 2), School head teachers (n = 4), and primary school teachers (n = 6) were invited for the pilot the research. The questionnaire was disseminated through the Internet using Google Forms. 12 min was recorded as average time taken by respondents to attempt the questionnaire. There were no negative observations noted for language difficulty however, two items were reported to be overlapping under the section effective leadership and quality assurance. Consequent modifications in the questionnaire was made to address this discrepancy. There were no negative observations for the semi-structured interview questions developed for the school head teachers.

Data Analysis and Discussion

One hundred twenty-eight respondents participated in this multi-method study. Respondents represented various layers of organizational hierarchy complying with extant literature that asserts effective school leadership and successful achievement as a product of multi-tiered support system within the school organizational set-up that initiates at senior leadership and permeates to classroom teachers through individual school leadership ( Mikesell, 2020 ).

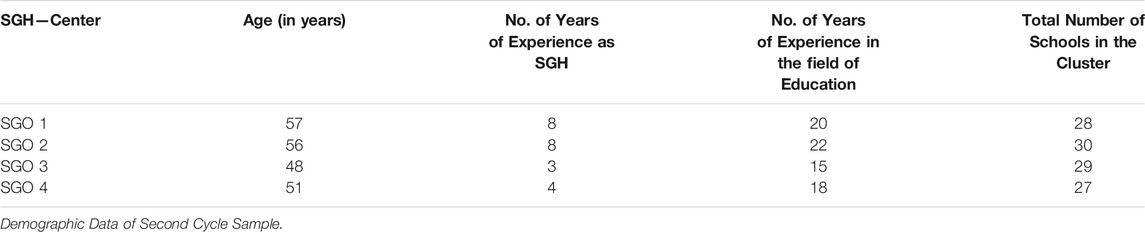

Demographic Data of First Cycle Sample.

Sample for the first research cycle comprised of four female SGHs. The demographic data defining their academic qualifications and the total number of years of professional experience is given in Table 1 .

TABLE 1 . Demographic Data for First Research Cycle.

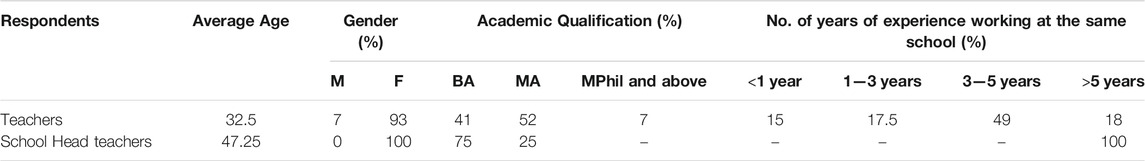

The conclusion of the first cycle of research led to the sample that took part in the second cycle of research. All teachers ( n = 120) and head teachers ( n = 4) of primary school branches identified as most successful by the SGHs took part in this research. Table 2 represents the demographic data about participants of this research including age, gender, academic qualification, and professional experience.

TABLE 2 . Demographic Data for Second Research Cycle.

The qualitative data were analyzed using MaxQD and the quantitative data was studied using SPSS version 22 for Windows. The analysis led to the emergence of some themes common with those determined in the West. The next section details key findings from the analysis of DSS and LPI.

Research Q1: Results of DSS

The research question; what are the determinants of a successful school in the private sector of Pakistani schools was addressed through the results of DSS. All SGHs account for high students learning outcomes measured in terms of academic, co- and extra-curricular activities as the most significant determinant of a school’s success. Quality of teaching and curriculum provision has been identified as other influencing determinants and lastly, there was a consensus that effective school leadership is responsible to bring these factors together.

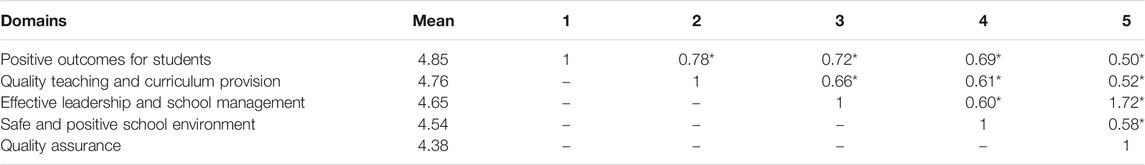

Table 3 shows the accumulative mean for all five domains of DSS in order of highest to lowest. The bivariate correlation of study variables projects a strong relationship with each other. The first domain, “Positive outcomes for students” accounts a positive relationship with all other determinants with the highest correlation with “Quality Teaching and Curriculum Provision” (r = 0.78) which asserts that teaching practices have a tremendous impact on students achievement. Analysis of results emphasizes the role of school leadership in boosting teaching and learning in classrooms with r=.66. Extensive long-term studies identify the school head teacher as the central source of school leadership ( Mulford, 2003 ; OECD, 2013; Louis et al., 2010 ) that significantly impacts pupil outcomes ( Leithwood et al., 2006 ). In this study, it is noteworthy that leadership was best correlated with “Quality Assurance” (r = 0.72) setting the significant foundation of self-evaluation and self-review. A strong culture of self-review is an indicator of thoughtful leadership ( Ofsted, 2010 ). The interrelationship of all these variables brings effective leadership as a vital determinant of school success.

TABLE 3 . Mean and Bivariate Correlation of Variables.

At the end of the first cycle of study, the SGHs were able to place effective school leadership at the heart of school success. This research supports the persuasive evidence present in favor of the strong influence of school leadership on school success. School success indicators presented by Hull (2012) , The Wallace Foundation, (2013) and DuFour and Marzano, (2011) in different contexts and regions of the world identify pupil achievement, quality of teaching, leadership and self-review in variable order of significance. Moreover, Felix-Otuorimuo (2019) found that the practices and experiences of school leaders influenced the strategies and approaches they can use to become successful school leaders.

Research Q2: Results of Leadership Qualities Index (LQI)

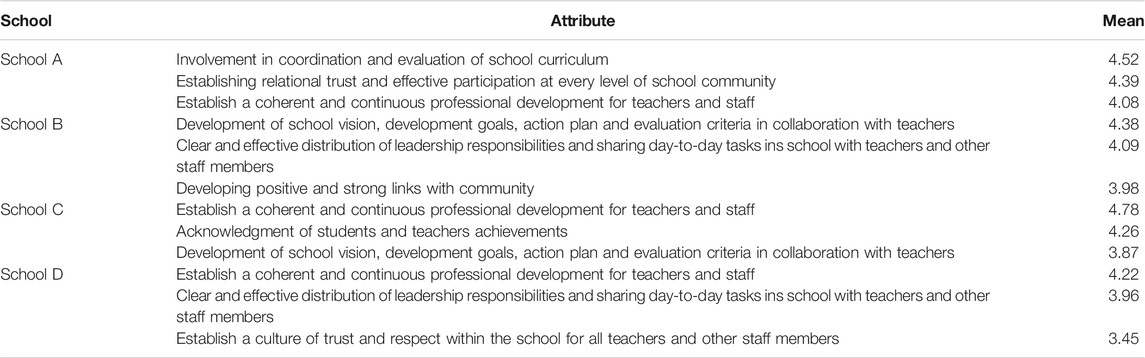

One hundred and twenty teachers from four different schools participated in the second cycle of research carried out to identify key leadership practices of school head teachers. Responses were gathered in the five levels of frequency for the demonstration of leadership practices. Table 4 presents the results of Leadership Qualities Index (LQI) calculated through SPSS and presented in an order of highest to the lowest mean score for the most prominent three leadership qualities practiced by school head teachers of four selected schools. The results of this section answer the research question; what are school head teachers leadership qualities in successful private primary schools of BSS in the province of Punjab?

TABLE 4 . Most Prominent Leadership Qualities.

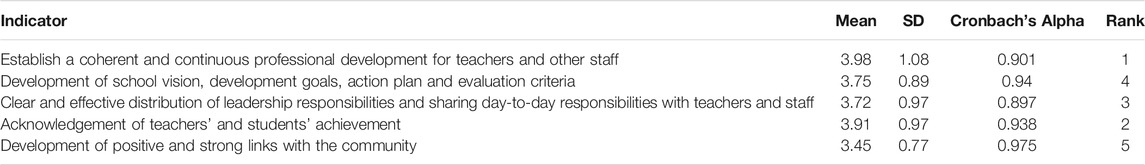

Research Q3: Factor Analysis.

A factor analysis on Likert-type survey items involving Varimax rotation and Kaiser normalization, led the researcher to answer the research question; what are the common trends in the leadership qualities of the selected school head teachers? It determined the common leadership traits of the four successful schools. With the Varimax rotation, the indicators were uncorrelated and independent from one another ( Kim and Mueller, 1982 ; Khan et al., 2009 ). With a sample size n = 120, loadings of at least 0.50 were considered significant and used to draw common attributes ( Khan et al., 2009 ) which were pronounced as the commonly occurring leadership traits of leaders of successful primary school head teachers as shown in Table 5 and discussed in the proceeding section.

TABLE 5 . Common Leadership Qualities of Successful School Head Teachers.

These results can be broadly divided into two types of leadership style dimensions; qualities directed towards task accomplishment, and qualities focusing on interpersonal relations ( Hydon, 2007 ; Nystedt, 1997 ).

Qualities Directed Towards Task Accomplishment

Establish a coherent and continuous professional development for teachers and other staff..

Analysis of this indicator reveals that all four head teachers taking part in this study rigorously planned the professional development exercises drawing upon training needs analysis, context, and school development targets. Seventy-two percent of teachers reported this aspect as a matter of routine practice for selected schools head teachers. Research tends to view leading teachers professional learning in coherence with their needs as an instructional leadership ( Gumus et al., 2018 ; Mulford, 2007 ; The Wallace Foundation, 2013 ).

All the head teachers taking part in the second cycle of study shared their views that support the methodical agenda for teachers in-service education. Head teachers strongly connected students learning outcomes with the quality of teaching and teachers professional learning and development.

“I make sure that our school development plan projects vision of commitment to greater achievement and success for all students that come with committed teachers in my opinion, access to opportunities for continuous learning strengthens teachers as the change agents I try to create opportunities for them to take part in professional education that is embedded in their daily job life and the best of their and the school’s interest” (Head Teacher School Branch C).

Three out of four schools promoted a strong culture of mentoring and regular peer-coaching with a purpose to embed learning within daily school routines to improve the quality of teaching. In an interview, a School head teacher stated:

“high achievement comes with good teaching; good teaching comes with learning, training we don’t have enough budget for training its better when teachers learn from their colleagues, it’s practical and situational learning learning on-job from peers is the best solution for us From their senior colleagues, they learn better without any hesitation.”

One out of four head teachers maintained that teachers learning portfolios which not only provided a learning graph but also serve as a source of information for setting annual appraisal targets. Longitudinal data for teachers training needs provide school leaders an opportunity to: graph individual professional development of teachers; address the most accurate training needs; and redefine induction criteria for new teachers ( Knapp and Hopmann, 2017 ).

Development of School Vision, Development Goals, Action Plan, and Evaluation Criteria in Collaboration with Teachers

The second leadership quality commonly identified by the analysis of qualitative and quantitative results is a shared vision. A majority of 68% of teachers identified this as a positive leadership trait possessed by their respective head teacher. Three out of four head teachers formulated an annual school development plan together with teachers to encourage individual ownership for achieving these targets. When teachers have formal roles in the decision-making processes regarding school initiatives and plans, they are more likely to perform better and take higher ownership of their decisions ( DuFour and Marzano, 2011 ). The same was reported by the head teacher of School B “when teachers have a direct input in formulating the school development plan, they take responsibility to achieve these targets because it is their plan, not a dictated idea”. Head teachers participating in this study regularly consulted BSS school evaluation framework and engaged in rigorous self-review to keep themselves and their staff aware of school performance.

Clear and Effective Distribution of Leadership Responsibilities and Sharing Day-To-Day Tasks in School with Teachers and other Staff Members

Analysis of head teachers interviews provided strong evidence of involvement of all staff to make leadership a combined endeavor, rather than practicing a model of single leader atop the school hierarchy. Research also supports that the distribution of leadership promotes a culture of trust, high motivation and coherent vision for school development ( Copland, 2003 ; Gronn, 2003 ; Spillane et al., 2005 ). A considerably high mean value for this indicator (3.72) and 63% of teachers vote for this leadership trait concludes it as one of the prime leadership qualities of successful school leaders. One of the head teachers from School “A” was of the view:

Heading a school is not a one-man show you know It requires joining hands together with all the stakeholders within the school premises and outside of the school I would not ignore the active engagement of parents, our academic liaison with other educational organizations, academia, and professionals of BSS and even the results of the latest research on school leadership.

Thus, the results show that the school heads believe in effective school headship as a joint venture and running the school democratically in collaboration with other relevant academic and administrative personnel of the school. It was revealed in a study conducted by Felix-Otuorimuo (2019) in Nigerian perspective that “successful primary school leadership in Nigeria is a collective and direct effort of the entire school community working together as a family unit, which cuts across the cultural and national boundaries of sub-Saharan Africa” (p. 218).

Qualities Directed Towards Interpersonal Relations

Acknowledgment of teachers and students achievement.

Appreciation, motivation, and empathy refer to the level of interpersonal care from senior leadership ( Gurr et al., 2005 ). Findings of the study revealed that about 59% of teachers indicate that their school head teachers mostly or always demonstrated a motivating, encouraging and facilitating behavior to project an increase in achievement of different cohorts of teachers and students. An emerging theme from head teachers interviews sets the intention of fostering a culture of support, trust, the concept of shared achievement and a sense of sensitivity when dealing with cohorts of students and teachers struggling to produce desired results. One of the senior school heads working in School “D” reflected:

The students, teachers, parents, BSS higher authorities and the head teachers work like a community who believe in mutual help, support and appreciation. We learn from each other strengths and weaknesses and acknowledge each other’s efforts in achieving the common school goals. Achievement of a single student is the achievement of the whole team working behind him and we must appreciate them all.

They have set systems in place to acknowledge, share and celebrate students and teachers achievements. Previous researchers have also emphasized on the significance of this indicator ( Day et al., 2016 ; Hitt and Tucker, 2016 ; Leithwood et al., 2017 ; Louis and Murphy, 2017 ; Leithwood and Sun, 2018 ). Williams (2008) reported that in high-poverty communities, successful school leaders primarily invest in relationship building focusing on individuals for collective progress. In an annual report on Education in Wales, Estyn, (2015) argues that a culture of trust, mutual empowerment, care, collaboration and genuine partnerships amongst all levels of staff serve as the driving force for effecting school improvement. Also, one of the most recent studies in this field conducted in the Nigerian perspective found that the school heads vision, trust in mutual relationship and personal belongingness established a strong relationship of school with the home and influenced the overall improvement in the school leadership ( Felix-Otuorimuo, 2019 ).

Development of Positive and Strong Links With the Community

There are systems in place for involvement of diffused communities such as art and literary societies in the city, health service providers, and global partnerships with other international schools. Exchange of work samples, networking of parents and distant mentoring for teachers via Skype are regularly practiced at these schools. A large percentage of teachers (68%) identified the culture of developing strong links with the outer community as a reason for the success of their school, the head teacher from School “C” supported: “we are not in a closed shell, I encourage teachers to adopt good practices, as long as they add to pupil achievement, change is good for developing”. All school head teachers engaged others outside the immediate school community, including parents and the local community. Community—School partnership was a positive trend that emerged from this study; research in the international context asserts that the impact of community involvement on school success is vague ( Hull, 2012 ). Nevertheless, a connection between school and family is an influencing factor to determine a school’s success and to improve students learning outcomes ( Boyko 2015 ; Goodall, 2017 ); Dodd and Konzal, 2002 ; Epstein, 2001 ). One of the head teachers who was working in School “A” asserted her remarks in these words: