- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Research: How Bias Against Women Persists in Female-Dominated Workplaces

- Amber L. Stephenson,

- Leanne M. Dzubinski

A look inside the ongoing barriers women face in law, health care, faith-based nonprofits, and higher education.

New research examines gender bias within four industries with more female than male workers — law, higher education, faith-based nonprofits, and health care. Having balanced or even greater numbers of women in an organization is not, by itself, changing women’s experiences of bias. Bias is built into the system and continues to operate even when more women than men are present. Leaders can use these findings to create gender-equitable practices and environments which reduce bias. First, replace competition with cooperation. Second, measure success by goals, not by time spent in the office or online. Third, implement equitable reward structures, and provide remote and flexible work with autonomy. Finally, increase transparency in decision making.

It’s been thought that once industries achieve gender balance, bias will decrease and gender gaps will close. Sometimes called the “ add women and stir ” approach, people tend to think that having more women present is all that’s needed to promote change. But simply adding women into a workplace does not change the organizational structures and systems that benefit men more than women . Our new research (to be published in a forthcoming issue of Personnel Review ) shows gender bias is still prevalent in gender-balanced and female-dominated industries.

- Amy Diehl , PhD is chief information officer at Wilson College and a gender equity researcher and speaker. She is coauthor of Glass Walls: Shattering the Six Gender Bias Barriers Still Holding Women Back at Work (Rowman & Littlefield). Find her on LinkedIn at Amy-Diehl , Twitter @amydiehl , and visit her website at amy-diehl.com

- AS Amber L. Stephenson , PhD is an associate professor of management and director of healthcare management programs in the David D. Reh School of Business at Clarkson University. Her research focuses on the healthcare workforce, how professional identity influences attitudes and behaviors, and how women leaders experience gender bias.

- LD Leanne M. Dzubinski , PhD is acting dean of the Cook School of Intercultural Studies and associate professor of intercultural education at Biola University, and a prominent researcher on women in leadership. She is coauthor of Glass Walls: Shattering the Six Gender Bias Barriers Still Holding Women Back at Work (Rowman & Littlefield).

Partner Center

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Gender bias in academia: a lifetime problem that needs solutions

Anaïs llorens.

1. Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA.

Athina Tzovara

2. Institute for Computer Science, University of Bern, Switzerland.

3. Sleep Wake Epilepsy Center ∣ NeuroTec, Department of Neurology, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University Bern, Bern, Switzerland

Ludovic Bellier

Ilina bhaya-grossman.

4. Department of Bioengineering, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA.

Aurélie Bidet-Caulet

5. Brain Dynamics and Cognition Team, Lyon Neuroscience Research Center, CRNL, INSERM U1028, CNRS UMR 5292, University of Lyon, Lyon, France.

William K. Chang

Zachariah r. cross.

6. Cognitive and Systems Neuroscience Research Hub, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia.

Rosa Dominguez-Faus

7. STEPS Program, University of California, Davis, CA, USA.

Adeen Flinker

8. NYU School of Medicine, New York, USA.

Yvonne Fonken

9. Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

Mark A. Gorenstein

10. Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA.

Chris Holdgraf

11. The Berkeley Institute for Data Science, Berkeley, CA, USA.

Colin W. Hoy

Maria v. ivanova, richard t. jimenez.

12. Department of Brain and Cognitive Science College of Natural Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea.

Julia WY. Kam

13. Department of Psychology, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada.

Celeste Kidd

Enitan marcelle, deborah marciano.

14. Haas School of Business, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA.

Stephanie Martin

15. Department of Cognitive Science, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA.

Nicholas E. Myers

16. Department of Experimental Psychology and Oxford Centre for Human Brain Activity, Department of Psychiatry, Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Karita Ojala

17. Institute of Systems Neuroscience, Center for Experimental Medicine, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

18. Department of Psychology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel.

Pedro Pinheiro-Chagas

19. Laboratory of Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience, Stanford Human, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA.

Stephanie K. Riès

20. School of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences and Center for Clinical and Cognitive Neuroscience, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, USA.

Ignacio Saez

21. Department of Neurosurgery, University of California Davis, Sacramento, CA, USA.

Ivan Skelin

22. Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, University of California Irvine, Irvine, CA, USA.

Katarina Slama

Brooke staveland, danielle s. bassett.

23. Departments of Bioengineering, Electrical & Systems Engineering, Physics & Astronomy,Psychiatry, and Neurology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

24. Santa Fe Institute, Santa Fe, NM 87501 USA.

Elizabeth A. Buffalo

25. Department of Physiology and Biophysics and School of Medicine, Washington National Primate Research Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Adrienne L. Fairhall

26. Department of Physiology and Biophysics and Computational Neuroscience Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Nancy J. Kopell

27. Department of Mathematics & Statistics, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA.

Jack J. Lin

28. Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, Department of Neurology, University of University of California Irvine, Irvine, CA, USA.

29. Department of Biomedical Engineering, Henry Samueli School of Engineering, Irvine, CA, USA.

Anna C. Nobre

Dylan riley.

30. Department of Sociology, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, 94720-1980, USA.

Anne-Kristin Solbakk

31. Department of Psychology, Oslo University Hospital-Rikshospitalet, Oslo, Norway.

32. Department of Neurosurgery, Oslo University Hospital - Rikshospitalet, Oslo, Norway.

33. RITMO Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Rhythm, Time and Motion, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway.

34. Department of Neuropsychology, Helgeland Hospital, Mosjøen, Norway.

Joni D. Wallis

Xiao-jing wang.

35. Center for Neural Science, New York University, 4 Washington Place, New York, NY 10003, USA.

Shlomit Yuval-Greenberg

36. School of Psychological Sciences and Sagol School of Neuroscience, Tel-Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, 6997801, Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel.

Sabine Kastner

37. Princeton Neuroscience Institute, and Department of Psychology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA.

Robert T. Knight

Nina f. dronkers.

38. Department of Neurology, University of California, Davis.

Despite increased awareness of the lack of gender equity in academia and a growing number of initiatives to address issues of diversity, change is slow and inequalities remain. A major source of inequity is gender bias, which has a substantial negative impact on the careers, work-life balance, and mental health of underrepresented groups in science. Here, we argue that gender bias is not a single problem but manifests as a collection of distinct issues that impact researchers' lives. We disentangle these facets and propose concrete solutions that can be adopted by individuals, academic institutions, and society.

Despite increased awareness of the lack of gender equity in academia, change is slow and inequalities remain. We disentangle the different aspects of gender bias impacting woman researchers throughout their lives. We expose the different issues and discuss potential solutions that can be adopted by individuals, academic institutions, and society.

2. Introduction

The past decades have seen tremendous scientific progress and astonishing technological advances that not long ago seemed like science fiction. Yet, such scientific progress stands in stark contrast to progress in improving the participation of underrepresented groups in academia, particularly in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics, known as STEM. A report from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) published in 2017 highlights the gender disparities encountered in science: Out of 16 NIH directors, only 1 was a woman; in the top 10 research institutes in the USA, the percentage of women with tenure among all professors was at most 26%, and in some cases even below 20%. Women occupied 37% of the NIH intramural research program tenure-track body, but only 21% attained tenured status, with women of color occupying only 5% of tenured positions (addressing gender inequality in the NIH intramural research program). The numbers show similar trends for PhD programs in the US. According to the Society for Neuroscience, the percentage of women applicants in PhD programs has increased in the recent years, from 38 % in 2000-2001 to 57 % in 2016-2017, with a matriculation rate of 48% for women in 2016-2017. By contrast, women represented only 30% of all faculty for PhD programs.

The statistics are similar in Europe. The European Research Council (ERC-Equality of opportunity in ERC Competitions) reported that only 32% of its panel members and 27% of its grantees in the Horizon 2020 program were women. In the Netherlands, 44% of PhDs were awarded to women in 2018, yet only 22% of the tenured faculty were women. A similar trend is reported in Switzerland, where close to 40% of fixed term professorships in 2017 were held by women, but for tenured positions the fraction of women dropped to 25%.

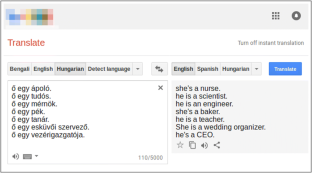

These statistics confirm the gender disparity that exists in higher academic positions, despite an almost equal representation across disciplines at earlier career stages (see Gruber et al., 2020 for a thorough investigation of gender disparities in psychological science). A putative cause of this phenomenon is gender bias, i.e., prejudice based on gender (encompassing the identity and the expression of that gender). Gender bias can be explicit or implicit. Explicit bias is a conscious and intentional evaluation of a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor ( Eagly and Chaiken, 1998 ). Implicit bias reflects the automatic judgment of the entity without the awareness of the individual ( Greenwald and Banaji, 1995 ). These types of bias emerge from different sources such as stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination ( Fiske, 1998 ), which reflect general expectations about members of a given social group. Gender stereotypes are broadly shared and reflect differences between women and men in their perspective and manner of behavior. Importantly, gender stereotypes also impact the way men and women define themselves and are treated by others, which in turn contributes and perpetuates such stereotypes (see Ellemers, 2018 for review). Gender bias impacts all women, with even more impact on women whose gender intersects with other identities that are often discriminated against, including but not limited to race and ethnicity (see Quick Take: Women in Academia), socio-economic status, religion, gender expression, gender identity, sexual orientation, or disabilities ( Armstrong and Jovanovic, 2015 ). Moreover, it has been shown that gender stereotypes influence the enrollment of women in STEM in many countries ( Miller et al., 2015 ; Hanson et al. 2017 ). As such, properly tackling this issue requires both structural and cultural change. Many of the biases and solutions presented in this article can apply to and be amplified in other minority groups (see our discussion of intersectionality), but a comprehensive assessment of those issues is beyond the scope of this paper. Indeed, pervasive gender biases do not start at the academic level, but they are deeply rooted in many societies and even appear early in life, impacting young girls’ career aspirations and lifetime educational achievements ( Makarova et al., 2019 ). For instance, in many cultures, it is a long-standing stereotype that boys are better at math than girls ( Else-Quest et al., 2010 ), which, in turn, impacts young girls’ performance on math tests ( Spencer et al., 1999 ) despite no intrinsic or biological difference ( Kersey et al., 2019 ; Shapiro and Williams, 2012 ). Parents’ and teachers’ expectations can also show biases that influence children’s attitudes and performance in math ( Gunderson et al., 2012 ). This gender stereotyping through interactions with parents, educators, peers, and the media has a negative effect on girls’ interest and confidence in their performance in STEM subjects, potentially reducing interest in research careers in STEM later in life ( Cheryan et al., 2015 , 2017 ).

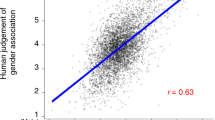

Here, we will focus on gender bias at the university level, which forms a further bottleneck for gender equity in STEM. The women-to-men ratio progressively decreases with advancing degrees and career stages. Despite remarkable progress made over the last three decades to mitigate gender bias ( Eagly, 2018 ), equity is still far from being reached in academia. Multiple studies have systematically documented bias in every aspect of academia ( Fernandes et al., 2020 ), including journal article and innovation citations ( Dworkin et al., 2020b ; Hofstra et al., 2020 ), publication rates ( West et al., 2013 ), patent applications ( Jensen et al., 2018 ), hiring decisions ( Nielsen, 2016 ), research grant applications ( Burns et al., 2019 ), evaluations of conference abstracts ( Knobloch-Westerwick et al., 2013 ), symposia speaker invitations ( Schroeder et al., 2013 ), postdoctoral employment ( Sheltzer and Smith, 2014 ), prestigious science awards ( Lunnemann et al., 2019 ), and tenure decisions ( Weisshaar, 2017 ). These forms of bias are intertwined, and evolve and accumulate along the career path (see Figure 1 ). Their combination can lead to a gradual abandonment of scientific careers by many women, the numbers of which decrease as career stages progress.

Expression of the accumulation of the different facets of gender bias throughout a woman researcher’s career organized according to when they begin to have an impact. Each line represents one aspect of the gender bias and covers the career stages it is prevalent in. The dot represents the peak in time of a given aspect.

Given the prevalent and deep-rooted nature of gender bias in academia, we aim to unravel different forms of bias, evaluate their manifestation over the career-span, and provide suggestions towards resolving gender disparity. We explain how pervasive gender bias affects different components, dimensions and roles of academics, and how these barriers to women’s advancement differ across each stage of career development. Our goal is to assemble information regarding the different facets of gender bias in a digestible format for the neuroscientific community. We aim to launch a discussion around the multifaceted and deeply rooted issues surrounding gender bias in academia and, in particular, in the field of neuroscience. We discuss problems faced by women in science, which are often taking place behind closed doors, providing information and increased awareness of central issues to academics and institutions seeking a balanced and fair environment. We also recommend both tested and untested concrete solutions to help mitigate the negative consequences of bias along three axes: at the individual (i.e., actions we can take as colleagues, friends, or mentors), institutional (i.e., policies and regulations), and societal levels (i.e., legislative action concerning society at large).

Changes in society and culture are often slow and difficult to implement, but without ongoing awareness, gender equality cannot be achieved. Solutions to the problem of gender bias have been difficult to achieve for many reasons, and some may be more tenable in certain circumstances than others. Here, we present exemplary policies from progressive institutions that have been effective in alleviating gender bias mostly in STEM, and specifically in neuroscience. We also describe quantitative tracking tools ( Table 1 ) that contribute to identifying and mitigating bias. As several manifestations of bias do not yet have concrete solutions with demonstrated results, we also propose some untested suggestions that may prove useful, and which future research could address ( Table 2 ). It is our hope that this article will continue the conversation toward resolving gender bias and bring us closer to tangible results.

Tools and Resources for Addressing Gender Bias in Academia

Summary of the different actions suggested throughout the manuscript to mitigate gender bias by section and level of responsibility. Each action is classified by its current status (tested/recommended, tested/debated or implemented) and supported by some examples of highlighted advocates. Note that many solutions for the individual are difficult to quantify, and so are left blank.

3. Gender biases are amplified through career stages

Though gender stereotypes are already strongly shaped in childhood ( Makarova et al., 2019 ), college or university study is a further bottleneck to gender equity. Even in their first year beyond high-school, women are 1.5 times more likely than men to leave the STEM higher education pipeline ( Ellis et al., 2016 ). In more advanced university degrees and career stages, the women-to-men ratio progressively decreases, referred to as the “scissors effect.” In most countries, the point where the effect begins is at the start of the university years with equal numbers of women and men enrolled. The gap widens (like an open pair of scissors) by the end of the postdoctoral career stage (European commission report 2015, GARCIA Project). In the United States, the gender gap continues to grow between the postdoctoral and associate professor years with women transitioning to principal investigator positions at about a 20% lower rate than men ( Lerchenmueller and Sorenson, 2018 ). Similar data have been reported for other agencies and countries, highlighting the widening gender gap across the career stages ( Burns et al., 2019 ; McAllister et al., 2016 ; Pohlhaus et al., 2011 ). Although the percentage of women among undergraduates, graduate students, and postdoctoral researchers has increased in the past few decades, women remain largely underrepresented in STEM faculty positions ( Beede et al., 2011 ; Field of degree: Women-NSF). Possible factors contributing to the increasing gender gap as careers progress will be reviewed in the following sections, where we will disentangle the various aspects contributing to each factor and propose concrete solutions to close the gender gap.

4. Gender bias hinders scientific productivity, authorship and peer-review

Women are systematically underrepresented as first and last authors in peer-reviewed publications relative to the proportion of women scientists in the field ( Dworkin et al., 2020b ; West et al., 2013 ). The discrepancy is particularly evident for senior author positions, as well as single-authored papers and commissioned editorials, i.e., positions typically reflective of senior roles ( Holman et al., 2018 ; Schrouff et al., 2019 ; West et al., 2013 ). Moreover, an overall increase in gender differences in productivity has accompanied the steady increase of women in STEM over the past decades. This difference in productivity between men and women is mostly explained by a higher female than male dropout rate while the yearly difference in productivity between genders is relatively small ( Huang et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, a study of peer review based on 145 journals in various fields reported that women submit fewer papers than men ( Squazzoni et al., 2021 ). The underrepresentation of women increases with the impact factor of the journal ( Bendels et al., 2018 ). Neuroscience is no exception, as women authors are less likely to submit to high-profile journals, including senior women. In 2016, only around 20% of neuroscience papers sent to Nature had a woman as corresponding author (Promoting diversity in neuroscience, 2018). But even when women do submit to such journals they face gender bias. Indeed, several studies where the identity of the authors was experimentally manipulated demonstrated that conference abstracts, papers, and fellowship applications were rated as having higher merit when they were supposedly written by men. These effects were even stronger in scientific fields viewed as more “masculine” ( Knobloch-Westerwick et al., 2013 ; Krawczyk and Smyk, 2016 ). Furthermore, a recent study of 9,000 editors and 43,000 reviewers from Frontiers journals demonstrated that women are underrepresented as editors and peer reviewers ( Helmer et al., 2017 ). Additionally, all editors, regardless of whether they are men or women, display a same-gender preference (homophily), which at the moment favors men in part because there are more men in the field ( Murray et al., 2019 ).

In addition to publications, a screening of approximately 2.7 million US patent applications indicated that there was also discrimination in the patent review process, leading to relatively few approved patent applications registered by women inventors ( Jensen et al., 2018 ). Many of these effects were larger in fields with a generally higher representation of women, such as life sciences, than in technology areas ( Hunt et al., 2013 ; Sugimoto et al., 2015 ; Whittington and Smith-Doerr, 2008 ). Though gender bias in authorship has been explicitly acknowledged for years (Women in neuroscience: a numbers game, 2006), it has changed minimally over the last decade ( Bendels et al., 2018 ; Holman et al., 2018 ; 2018 ). Although the publication gap is decreasing, it is wrong to assume that there will be a proportional representation anytime soon without further active interventions ( Bendels et al., 2018 ). In some disciplines, such as math, computer science, and surgery, gender parity in publications is unlikely to be reached in this century due to the current slow rates of increased representation of women ( Holman et al., 2018 ). Other fields, such as psychology, have seen relatively greater increases in publications by men authors over time, further widening the gender gap ( Ceci et al., 2014 ). Given that publishing, particularly in high-profile journals, is critical for hiring decisions and career advancement, this inequality in authorship will continue to contribute to the increasing gender disparity across academic ranks ( Fairhall and Marder, 2020 ).

Suggestions for decreasing gender bias at an individual level:

Increasing awareness for all scientists, editors and reviewers regarding gender bias in authorship could help mitigate this issue. All scientists could seek out education in gender bias, and proactively consider how to adjust their own behavior to ensure equity in their reviews.

Suggestions for decreasing gender bias at the institutional level:

Finding alternatives to single-blind review is needed to increase the transparency of the peer review process ( Barroga, 2020 ; Lee et al., 2013 ). One proposed solution to mitigate gender bias in the review process is adoption of double-blind review, hiding the authors’ name ( Rodgers, 2017 ). Double-blind review has been introduced in several fields, such as ecology and computational sciences, and has been successful in reducing biases due to geographic location or university reputation ( Bernard, 2018 ; Budden et al., 2008 ; Mulligan et al., 2013 ; Snodgrass, 2006 ; Tomkins et al., 2017 ). It is also standard usage in the top journals in sociology, political science, and history and was introduced in some neuroscientific journals such as eNeuro. However, the efficacy of double-blind review in reducing gender bias is still unclear. An early study found that introducing double-blind peer review significantly increased the number of first-authored papers by women ( Budden et al., 2008 ), whereas later studies found no effect on review gender bias ( Cox and Montgomerie, 2019 ; Tomkins et al., 2017 ). It is possible that more recent blind reviews were compromised by the use of preprint servers that list authors’ full names. Another proposed solution is an open peer review as currently implemented in Frontiers journals where the names of the authors and the editor and reviewers are made public upon publications. One last alternative would be a hybrid peer review system combining open discussion between scientists and peers while preserving the anonymity of the latter ( Bravo et al., 2019 ; Lee et al., 2013 ). Such a system could consist of a pre- or post- publication discussion platform that allows referees, editors, and authors to interact providing feedback on a paper.

Importantly, academic journals need to pay attention to potential sources of gender bias in order to be able to identify ways to mitigate them. One way to encourage review and editorial panels to improve accountability and transparency is to make demographic information regarding authors and reviewers publicly accessible ( Murray et al., 2019 ). This is already implemented by PEERE, an European protocol designed to be an equitable way to get more data on the peer review process ( Table 1 ; Squazzoni et al., 2017 ). Moreover, an increasing number of publishing groups are publicly releasing statements in support of diversity in authors, citations, and/or referees ( Sweet, 2021 ; 2018). As a recent example, Cell Press is encouraging authors to evaluate their citation lists for biases, as well as to ensure diversity in their research participants, authors and collaborators ( Sweet, 2021 ). It is also the case of eLife which sets a twice-yearly report about actions taken to improve transparency, promote equity, diversity and inclusion in the publishing process as well as in their editorial board. Such initiatives are setting a positive example that could be followed by more publishers across all academic fields.

5. Gender differences in the number of citations

Citation metrics have emerged as a critical index of productivity in the biological and cognitive sciences. Citation counts influence hiring and tenure decisions, grant awards, speaker invitations, and career recognition. As an example, a study in the field of astronomy showed that in 149,000 publications, a paper whose lead-author was a woman received 10% fewer citations on average than similar papers with a man as leading author ( Caplar et al., 2017 ). In top neuroscience journals, that number is even greater; papers with women as first and last author receive 30% fewer citations than expected given the number of such papers in the field ( Dworkin et al., 2020b ).

Furthermore, recent research reveals that contemporary citation practices skew these metrics in favor of men, undervaluing woman-led research of equivalent quality and potential impact. In particular, men undercite women scientists relative to men scientists, and their rates of self-citation are higher than those of women ( Dworkin et al., 2020b ; King et al., 2017 ). Additionally, men are more likely to use promotional language, such as positive words (e.g. “unprecedented” or “excellent”) in the title or abstract, which in turn leads to more citations and an inflation of the h-index ( Cameron et al., 2016 ; Kelly and Jennions, 2006 ; Lerchenmueller et al., 2019 ; Woolston, 2020 ). It is also possible that citation bias is exacerbated by the use of social media platforms such as Twitter. A recent randomized controlled trial demonstrates that papers that were tweeted received more citations at the end of one year than papers that were not tweeted ( Luc et al., 2021 ). Women academics have disproportionately fewer Twitter followers, “likes”, and re-tweets than men academics, controlling for their social media activity levels and professional rank ( Zhu et al., 2019 ).

Suggestions at the individual level:

At the individual level, all authors should be more aware of which articles they cite in their work. In particular, articles that already have a high number of citations are seen as “seminal” thus exacerbating biases that may not reflect quality. In the case of multiple possible citations, they should seek to balance the number of citations between genders according to a chosen model of research ethics. In the distributional model, citations would be distributed in a manner that is proportional to the percentages in their field, while in a diversity model, citations would be distributed in a manner that seeks to proactively counteract a history of inequality ( Dworkin et al., 2020a , 2020b ). Practically, efforts to diversify one’s reference list can be supported by algorithmic tools that now exist to predict the gender of the first and last author of each reference by using databases that store the probability of a name being carried by a woman ( Zhou et al., 2020 ). This tool already exists in neuroscience ( Table 1 ) and we recommend wide implementation across academic fields.

Suggestions at the institutional level:

One proposed solution is to increase diversity in review and editorial panels ( Murray et al., 2019 ) as implemented by Progress in Neurobiology and Elife among other journals. As a notable example, Progress in Neurobiology, has an editorial board with 80% women associate editors. This can help mitigate bias, but may not be sufficient, as even women might be biased against other women. One option is to develop alternative citation metrics that account for the influence of self-citation and gender bias. One example of these metrics are the m-index, which is the h-index adjusted for career age, or the m(Q)-index, which adjusts for career age and excludes self-citations ( Cameron et al., 2016 ).

We also suggest that journal editors incorporate existing quantitative tools that analyze the gender ratio of a reference list by probabilistically inferring the gender of authors in a list of citations (see Table 1 ). Journals could then require authors to either eliminate any possible bias or provide a detailed justification for their deviation from the expected distribution. We also recommend the implementation of additional algorithmic tools in scientific journal submission websites to identify under-cited articles by women authors in a subfield, or to notify authors of citation biases in their submissions. Lastly, journal editors could consider increasing limits on the number of citations to accelerate the diversification of reference lists. As an example, Neuron modified their guidelines to exclude reference sections from the maximum character limit in research article submissions.

6. Scientific funding and awards are heavily biased

Funding is crucial to a researcher’s scientific progression and career advancement, including gaining tenure and broad professional recognition ( Charlesworth and Banaji, 2019 ; Duch et al., 2012 ). While the funding landscape is slowly evolving towards gender parity, women still face substantial challenges as they compete for limited resources. Some funding agencies collect data on the distribution of funding across genders. For instance, the percentage of NIH research grants awarded to women has been steadily growing over the past two decades: increasing from 23% in 1998 to 34% in 2019 (NIH Data Book—Data by Gender, 2020), with similar patterns observed for the National Science Foundation (NSF), the United States Department of Agriculture, and the European Research Council (ERC) ( Charlesworth and Banaji, 2019 ; ERC consolidator grants 2019 - statistics, 2019). However, despite this positive trend, progress still needs to be made as women scientists typically hold fewer grants and receive smaller awards compared to men scientists (National Institutes of Health, 2020; 2019).

Interestingly, while women receive more NIH research career grants at an early career stage than men (54%), the percentage of grants awarded to women progressively drops for grants associated with later career stages (research project grants: 34%; research center grants: 26%; NIH, 2020). Similar data have been reported for other agencies and countries, highlighting the widening gender gap across career stages: women are awarded fewer larger grants and are less likely to have them renewed than men ( Burns et al., 2019 ; McAllister et al., 2016 ). Possible factors contributing to this increasing gender gap might be publication and citation practices, family circumstances, and other barriers resulting from implicit and explicit gender stereotypes ( Pohlhaus et al., 2011 ). Moreover, the percentage of women submitting research grant proposals as a PI is less than expected relative to their representation in all fields but engineering ( Rissler et al., 2020 ).

The funding gap is also apparent in the amount awarded, with men typically asking for more funds ( Waisbren et al., 2008 ) and obtaining larger grants than women (National Institutes of Health, 2020). A recent study found a median gender disparity in NIH funding of $39K per year awarded to first-time principal investigators, while no significant differences by gender were found in the performance measures (i.e., median number of articles published per year, median number of citations per article, and the number of areas of research expertise in published articles prior to their first NIH grant; ( Oliveira et al., 2019 ). The differences were even more pronounced for funding acquired by investigators at prominent U.S. universities (median gender difference of $82k). Although the gender gap is smaller regarding R01 awards (median difference $16k), men receive more of them (after controlling for other performance measures; (National Institutes of Health, 2020; Pohlhaus et al., 2011 ). Furthermore, data from the NIH also show that the most dramatic differences in funding amounts were observed for research center grants (average difference of $476k), again highlighting increasing disparity at later career stages.

Although the proportion of women who receive career awards for their scientific contributions has steadily increased over the past decades, women still receive substantially fewer prizes than men, and less money ( Ma et al., 2019 ). Across 13 major STEM disciplines, only 17% of professional award winners were women ( Lincoln et al., 2012 ). This number is lower than expected based on overall representation by women in the STEM fields (38% for junior faculty and 27% for senior), likely indicating review bias with professional efforts and accomplishments of women not receiving the same recognition. Gender disparity is even more dramatic for more prestigious awards. For instance, women represent only 21% of Kavli Prize winners, 14% of recipients for the National Medal of Science, 3% for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 3% for the Fields Medal in Mathematics, and 1% for the Nobel Prize in Physics ( Charlesworth and Banaji, 2019 ; RAISE Project 2018).The year 2020 was a unique year in Nobel Prizes, with two women winning the prize for Chemistry and one woman the prize for Physics. Despite this positive step, gender equity is still lacking, and active efforts need to be continued to ensure that women will keep being represented in prestigious awards in the years to come. Gender bias in distinguished recognition perpetuates the falsehood that only men can aspire to the highest levels of academic achievement, thus sending a harmful message to younger generations of aspiring scientists. Furthermore, disparities in funding and recognition tend to have a subsequent snowball effect. Indeed, grant funding drives scientific productivity, which in turn drives promotions; promotions drive increases in salaries and stature; stature drives recognition. Gender bias at each of these collective steps serves to further hamper the advancement of women in their academic careers.

Suggestions at the Individual level:

The process of applying for certain career transition awards across scientific disciplines, such as NIH K awards or the Burroughs-Wellcome career award, forces both the applicant and the mentor to envision the candidate in the role of a faculty member, something that can have a profound effect on the candidate’s internal model of self and the attitude of the mentor.

Suggestions at the Institutional level:

Solutions could emerge directly from funding agencies in all scientific disciplines if they commit to actively monitoring for gender differences and ensuring gender equity in grant application rates, success rates and amounts awarded. To ensure fairer funding, we suggest that agencies introduce a gender target for grant applicants, success rates and amounts awarded. This could consist of a defined percentage of women researchers or amount of funding allocated to them at different career stages. Crucially, funding agencies should hold themselves accountable for attracting more female applicants, by changing the procedures used in their competitions to create more equitable outcomes ( Niederle, 2017 ; Niederle and Vesterlund, 2011 ). Further, it has been shown that having a target representation among women leads to increased numbers of applications by women; this brings stronger candidates to the competition, with little reverse discrimination -i.e. discrimination in favour of women- ( Niederle et al., 2013 ). Importantly, in contrast to some affirmative action approaches, this approach preserves the performance and the quality of the competition ( Balafoutas and Sutter, 2012 ).

This step could be enhanced by alerting the committee to potential gender bias (that both male and female reviewers are susceptible to) and even prefacing grant reviews with bias training. In addition, women are particularly underrepresented as leaders on large projects and/or international collaborations, and adjusting this imbalance could help establish overall gender equity in research funding. Finally, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research have successfully increased the number of female grant recipients by creating funding mechanisms that dispense awards focusing on the merit of the scientific proposal instead of the merit of the principal investigator ( Witteman et al., 2019 ).

Moreover, monitoring implicit bias by making the demographics information of former grantees accessible to funding committees could help pinpoint the disparities and distribute the resources more equitably ( Choudhury and Aggarwal, 2020 ). To reduce bias in the amount of requested funding, we suggest that submission portals implement artificial intelligence tools to provide researchers with recommendations on amounts of funding given their career stage and type of research. This suggestion follows the findings of Bowles and colleagues, who have shown that women ask for as much as men when ambiguity about bargaining range is reduced ( Bowles et al., 2005 ).

Importantly, department chairs and deans must commit to an equitable distribution of institutional resources across genders. Additionally (but not as an alternative), department chairs could actively encourage, support and provide the means (for example through release time, workshops, etc.) to all faculty members to pursue applications for career awards and large grants such as program projects and center grant funding (see Gender Equity Guidelines for Department Chairs).

7. Teaching evaluations reflect biases and gender-role expectations

Gender biases are ubiquitous in the classroom, affecting both the students and their professors ( Fan et al., 2019 ). At the student level, what professors integrate in their course syllabi shapes students’ knowledge and perception of academia. Women are under-cited as well as under-assigned in syllabi: 82% of assigned readings in graduate training in international relations across 42 U.S. universities are written by all-men authors ( Colgan, 2017 ), and only 15 of the 200 most frequently assigned works in the section “politics” of the Open Syllabus Project are authored by at least one woman ( Sumner, 2018 ).

At the professor level, large-scale studies have found that women instructors receive lower than average scores on their student evaluations in comparison to men and that gender bias can be so substantial that more effective instructors are rated lower than less effective ones ( Mengel et al., 2018 ). These findings have been substantiated in experimental studies, where the gender identity of the instructor in online courses was manipulated, with the instructors receiving lower ratings from both male and female students when they were believed to be women ( Khazan et al., 2019 ; MacNell et al., 2015 ). Men are perceived by all genders to be more knowledgeable and to have stronger leadership skills than their women counterparts ( Boring, 2017 ), even when there are no actual differences in what students have learned. This bias towards masculine traits during student evaluations of teaching (SETs) can have an important impact on the career of women scientists, as it is commonly used as a measurement of teaching effectiveness for promotion and tenure decisions. Apart from bias in the perception of women as teachers, women also tend to have higher teaching loads compared to men, and less time for research ( Misra et al., 2011 ), which can negatively impact their research productivity.

We propose the use of existing tools ( Reinholz and Shah, 2018 , see Table 1 ) that can help faculty to build their syllabi and bibliographies in a more gender-balanced way ( Sumner, 2018 ). In particular, faculty could provide historical examples of successful women scientists to reinforce female role models, ensure that the resources they give to their students are gender balanced ( Table 1 ), and use more inclusive language (i.e. ‘folks’ instead of ‘guys’, ( Bigler and Leaper, 2015 ).

The necessity to improve fairness and objectivity in teaching evaluations is critical to balance the odds for promotion across genders. A study conducted at the University of California, Berkeley, suggested abandoning the SETs as the principal measure of teaching effectiveness, and implementing instead other types of assessment, such as observing the teaching and examining teaching materials and portfolios ( Stark and Freishtat, 2014 ). Moreover, improvement in the phrasing of the SETs is also required. Simple changes to the language used (e.g., explicitly asking students to be aware of their biases) had a positive impact on the assessment of women professors ( Peterson et al., 2019 ). Prefacing SETs with counter-stereotype content could further decrease bias that is evident during the evaluation itself ( Blair et al., 2001 ).

8. Academic hiring, tenure decisions and promotions favor men

Evaluation criteria for hiring and promotion commonly used in academia are also susceptible to gender inequality. These biases are common across all hiring stages, encompassing lab manager positions ( Moss-Racusin et al., 2012 ), postdoctoral fellowships ( Sheltzer and Smith, 2014 ), as well as tenure track positions ( Steinpreis et al., 1999 ).

Strikingly, despite experimental and observable data in STEM fields reporting favorability toward women in hiring decisions compared to equally qualified men, women remain heavily underrepresented in tenure track positions (National Research Council et al., 2010; Williams and Ceci, 2015 ). This discrepancy has multiple potential sources related to different dimensions of gender bias. Gender biases in recruitment can occur even before applicants are evaluated ( Nielsen, 2016 ). In neuroscience and STEM in general, most departmental or unit leaders are men ( Gupta et al., 2005 ; McCullough, 2019 ). Consequently, men are more likely than women to define the unit’s strategic research foci and/or teaching needs, draft the job profile, and outline the announcement, thereby determining the focus of the search. Defining a profile in a broad or narrow manner directly impacts the number and quality of eligible candidates. Narrow profiles can be used to legitimize the selection of a specific candidate ( van den Brink, 2010 ) and often penalize women, as men’s social networks benefit from a higher proportion of scientific leaders ( Greguletz et al., 2019 ; James et al., 2019 ). The practice of some academic institutions limiting open recruitments presents an added barrier for women. A study in Denmark showed that, at the University of Aarhus, about 20% of associate and full professor positions were filled via a closed recruitment procedure ( Nielsen, 2015 ); such procedures are likely to propagate bias, as closed recruitment frequently results in a single applicant ( Nielsen, 2015 ).

The evaluation and selection phase of the hiring process contributes to the persistence of gender imbalance ( Rivera, 2017 ). Since men continue to be overrepresented among tenured/tenure-track faculty, evaluation committees and interview panels tend to have skewed gender composition ( Sheltzer and Smith, 2014 ). Gender bias during hiring is amplified by the role of “elite” male faculty, who employ fewer women in their labs and have a disproportionate effect on training the next generation of faculty; these processes in turn, affect hiring at high-ranking research universities ( Sheltzer and Smith, 2014 ). Moreover, studies performed in Italian and Spanish academic institutions across several scientific fields show that when promotion committees are composed exclusively of men, women are less likely to get promoted ( De Paola and Scoppa, 2015 ). Each additional woman on a 7-member promotion committee increased the number of women promoted to full professor by 14% ( Zinovyeva and Bagues, 2011 ). Another important factor in reducing gender bias in committee decisions is committee member awareness of implicit bias. Indeed, as shown in a recent study in France conducted across scientific disciplines, committee members who believe that women face external barriers in their performance and evaluation are less biased towards selecting men ( Régner et al., 2019 ).

The biases that affect search criteria also influence the evaluation of the applicant’s curriculum vitae. When faculty believe the applicant to be a man, they tend to evaluate the CV more favorably and are more likely to hire the applicant ( Moss-Racusin et al., 2012 ; Steinpreis et al., 1999 ) than when faculty believe the applicant to be a woman. Consequently, only women with extraordinary applications tend to be considered, narrowing the pool of potential women candidates to be interviewed.

Another source of bias during hiring comes from recommendation letters. Their content and quality significantly differ based on the gender of the applicant ( Dutt et al., 2016 ; Madera et al., 2009 ; Schmader et al., 2007 ). For example, letters in support of women are typically shorter, raise more doubts, include fewer ‘standout’ adjectives (e.g., superb, brilliant) and more ‘endeavor’ adjectives (e.g., hardworking and diligent), regardless of the gender of the recommender. Altogether, subtle gender biases throughout the academic hiring process, from job posting to evaluation, increase the risk of creating self-reinforcing cycles of gender inequality ( van den Brink et al., 2010 ; Nielsen, 2015 ).

We recommend that individuals writing job announcements be made aware concerning gender bias issues both explicit and implicit. Individuals evaluating applications should also be trained on topics relevant to gender equity, gender bias, and bias mitigation ( Bergman et al., 2013 ).

Bias awareness workshops could help scientists to improve job advertisements, and assess applications more objectively ( Carnes et al., 2015 ; Schrouff et al., 2019 ). This approach is already in place in some academic institutions (e.g., in the University of California system) and could be more widely adopted and made mandatory for all academic members. The University of Wisconsin-Madison has successfully increased diversity by implementing workshops for faculty search committees that raise awareness about unconscious bias and provide evidence-based solutions to counter the problem ( Fine et al., 2014 ). These types of workshops can be broadly implemented across institutions and fields. Finally, numerous studies show that reminding evaluators of their internal biases at the evaluation stage of the hiring process reduces the impact of bias ( Carnes et al., 2015 ; Devine et al., 2017 ; Smith et al., 2015 ; Valantine et al., 2014 ).

Efforts should also be made to increase diversity in search committees. Increasing representation of women is necessary for reducing bias ( Schrouff et al., 2019 ; Smith et al., 2004 ), despite not being sufficient on its own (see Discussion ). At the same time, institutions should ensure that women in underrepresented departments are not overloaded with administrative obligations, time-consuming committees, or any other assignment tasks that do not enhance promotion prospects ( Babcock et al., 2017 ). To increase diversity in search committees while not overworking women, we propose that members of search committees be compensated by reducing their teaching or other administrative duties. Importantly, we highlight the strong need for male allies as part of search committees (see Discussion ).

Some academic institutions have already introduced mediators from equity committees in the hiring/promotion procedure. For example in Switzerland such mediators are required to actively provide input in faculty hiring and monitor gender balance (Gender Monitoring_Egalité_EPFL). Although non-academic advisors cannot judge the quality of scientific work, their input on the fairness of the hiring process can be valuable.

Each institution must commit to policies and action plans that set quantifiable goals for women in different position categories. Ideally, the number of women reaching the interview stages should match the gender ratio of a given academic field. Concrete recruitment strategies to achieve these goals could be developed, for example, by adopting mandatory submission of regular reports on gender ratio with quantifiable measures ( Bergman et al., 2013 ). As an example, if no women candidates apply, the University of California at Berkeley requires the position to be re-announced more broadly. Institutions can be required to be more explicit and transparent about how merit is evaluated. All of the above measures can be enforced with central incentives, such as funding allocations, to motivate departments to implement the necessary steps and hire more women ( Bergman et al., 2013 ). Another solution to help reach a larger and more diverse pool of potential candidates would be the development of a curated and regularly updated list of underrepresented minority mentees that could become targets for job searches and awards (as it is already the case for conference speakers, Table 1 ).

Importantly, we believe that hiring committees need to recognize forms of scientific contribution to the STEM community not directly tied to scientific productivity. Such contributions include outreach, knowledge dissemination, and faculty service; these are contributions which women make on average significantly more than men, taking time from more traditional forms of research ( Guarino and Borden, 2017 ). The practice of science is evolving, and additional qualification criteria for hiring decisions should be adopted to acknowledge the broader range of roles and responsibilities of contemporary scientists ( Moher et al., 2018 ). In addition to building towards gender equity, recognizing and incentivizing these contributions to our academic communities will benefit all scientists regardless of gender.

Suggestions at the societal level:

When legally possible (as in Sweden, Germany, and Switzerland), any organization, including academic institutions can set policies on gender equity, set goals for gender ratios in different position categories, and develop recruitment strategies to achieve these goals ( Nielsen et al., 2017 ; Schrouff et al., 2019 ; Exploring quotas in academia; Des quotas pour promouvoir l’égalité des chances dans la recherche).

9. Gender bias in negotiation outcomes

Negotiations are important for building a successful career, as they can lead to better starting salaries and start-up packages, salary increases, better work conditions, and increased allocation of personnel, lab space, and other resources. On average, men tend to initiate negotiations more often than women ( Babcock et al., 2006 ; Small et al., 2007 ). Additionally, when they do, women still get less out of negotiations; are less likely than men to be successful in receiving the raise they asked for, and may incur a social cost for standing up for themselves ( Bowles et al., 2007 ; Mazei et al., 2015 ).

Importantly, negotiations might be affected by perceived gender stereotypes as gender roles influence both parties of the negotiations regardless of their gender ( Kray et al., 2001 , 2014 ). In accordance with Role Congruity Theory ( Eagly and Karau, 2002 ), women are often reluctant to negotiate because initiating negotiations is perceived as stereotypically male behavior. Moreover, expressions of emotions commonly associated with leadership characteristics, such as anger and pride ( Brescoll, 2016 ), are more widely tolerated and even appreciated when they emanate from men compared to women ( Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008 ). The expression of gender roles is a complex phenomenon though. On the one hand, women may lose social capital (i.e the work connections that have productive benefits) when voicing their opinions, especially when they go against the group’s opinion. On the other hand, it has been reported that women who described themselves as displaying so-called "masculine" personality traits (i.e., a competitive mindset and willingness to take risks) had a 4.3% greater chance of getting positions and were more likely to take up positions that offered 10% higher wages than those displaying so-called "feminine" personality traits (i.e., gentle, friendly, and affectionate)( Drydakis et al., 2018 ). This deep-seated implicit bias, held by all genders, has non-trivial consequences over women’s career in academia.

Transparency is a key element for equity during negotiations. We propose that institutions provide access to everyone's salary and also to a range of possible salaries per academic level. Gender differences in economic outcomes tend to be smaller when negotiators first receive information about the bargaining range in a negotiation ( Mazei et al., 2015 ). Such an approach could be complemented by providing information to faculty about ranges of research budgets, or salaries and construct a rational -rather than ad-hoc- process for determining how resources are allocated.

Removing stereotypes in both parties of the negotiations can improve women’s performance ( Kray and Kennedy, 2017 ). It has been shown that having supportive academic supervisors plays an important role in improving negotiational effectiveness for women ( Fiset and Saffie-Robertson, 2020 ). Also, for mentees eager to develop their negotiation skills, institutions could offer courses on this topic. For instance, several online services, highlighted on Table 1 , offer training materials on negotiation strategies, as well as materials targeted for companies wanting to improve their gender representation. These workshops provide techniques for negotiation and conflict resolution.

10. Gender inequalities are present in conferences

Conferences and meetings are crucial avenues for scientists to communicate new discoveries, form research collaborations, communicate with funding agencies, and attract new members to their labs and programs ( Calisi and a Working Group of Mothers in Science, 2018 ). For instance, invitations to seminars at different institutions increase scientists’ visibility and expand their academic networks. However, equally qualified women scientists are often given fewer opportunities to speak at conferences and seminars than men. For instance, nearly half of the conferences in neuroscience have fewer women speakers than the base rate of women working in the field of the conference (Conference Watch at a glance ∣ biaswatchneuro, How scientists are fighting against gender bias in conference speaker lineups). Given that conference presentations are an important indicator of the impact and significance of one’s research, this form of gender bias has negative implications for women during hiring and promotion. Inviting women speakers and providing them with resources that allow them to attend the conference contributes to their professional development and increases their visibility. This action also contributes to the perception of women researchers as leaders for young scientists in the audience. This visibility is especially important for boosting the confidence of young women researchers. Moreover, women in the conference audience generally remain less visible, as they ask fewer questions than men. This is due to both internal (e.g., being unsure whether their question is appropriate) and structural factors (e.g., when the first question is asked by a man, women are less likely to follow up) ( Carter et al., 2018 ).

Another important point that undermines the experience of women at conferences is unprofessional and inappropriate behavior ( Parsons, 2015 ) (see the below section 11 on sexual harassment). This may cause some scientists to avoid conferences due to feeling unsafe ( Richey et al., 2015 ). Specifically, sexual and gender harassment and micro-aggressions target primarily women, and are a common form of reported harassment at conferences ( Marts, 2017 ). Finally, disrespectful and unprofessional questions and feedback during poster sessions and talks may discourage women from presenting their work ( Biggs et al., 2018 ).

We recommend that invited participants take proactive actions to promote gender equity. They could ask the organizers what measures are taken to ensure that the symposium and/or conference will not be a man-dominated event, and could also decline to speak at conferences with an imbalanced speaker lineup. For instance, attendees can monitor progress in a conference’s history of gender balance in speaker selection and see the base rates of women in relevant subfields, as is already possible in neuroscience ( Table 1 ). We believe that scientists of all genders and levels of seniority should take personal responsibility to ensure professional conduct by speaking out against harassment and other biased behaviors.

Conferences can strive to ensure that symposia include gender-balanced speakers and chairs, at least in a ratio that matches the demographics of the field. Conference, seminar, and symposium organizers should have a list of women speakers that they can invite. They can search outside their personal and professional networks by consulting resources such as the directory compiled by Jennifer Glass and Minda Monteagudo which lists searchable databases of highly qualified women by subfield ( Table 1 ). As a notable example, proposals for symposia at the Federation of European Neuroscience Societies (FENS) Forum are required to include men and women speakers or provide a justification for single-gender symposia.

We also propose that organizers consider existing tools to mitigate their own bias. Gender balance at neuroscience conferences has been publicly monitored through the website BiasWatchNeuro ( Table 1 ). Such measures could be implemented in many academic fields. In the context of conferences, unlike that for citations, diversity must come from the top: the organizations hosting a conference should strive for a committee that is well trained regarding bias. The Organization for Human Brain Mapping (OHBM) has introduced an ‘Affirmative Attention’ approach, by which new Council members are elected through a ballot, so that the candidates for at least some open positions may only include women, to ensure that the gender distribution in the council remains equitable, no matter which candidates get elected ( Tzovara et al., 2021 ). Conference organizers can also offer programs that raise awareness of the issue of gender bias. For example, the annual meetings of several major conferences, such as the Society for Neuroscience, OHBM, or FENS, include educational courses, workshops and informational sessions on gender bias (Seeds of Change within OHBM: Three Years of Work Addressing Inclusivity and Diversity). Another example is the ‘power hour’ institutionalized by The Gordon Research Conferences which consists of a forum for conversations about diversity, inclusivity and related topics (The GRC Power Hour™).

However, in workshops about gender bias, often only highly successful women are represented on panels discussing bias and women’s careers in academia. In these instances, we believe that it is important to avoid promoting survivorship bias, which emphasizes positive outcomes without addressing the barriers and challenges that must be overcome to achieve that success more broadly among women scientists. Moreover, men are not usually invited as speakers in these events and are also usually absent from the audience, which renders them less aware of the issues around gender bias, and therefore less effective allies. We suggest that the way that the speakers and topics of panels are chosen must be improved to be more inclusive and represent the full spectrum of diversity in the community.

An inclusive code of conduct has been proposed as mandatory for each conference, stating what is and what is not appropriate behavior for conference attendees ( Favaro et al., 2016 ). Conference organizers should have clear plans of action in place in case harassment occurs, including anonymous reporting and removing confirmed harassers from the conference ( Marts, 2017 ; Parsons, 2015 ). The suggested code of conduct should also include respectful ways to provide constructive scientific feedback ( Favaro et al., 2016 ), a practice that should be implemented across all contexts within academia. Lastly, all attendees should feel concerned about and responsible for maintaining a respectable environment during conferences. Since it can sometimes be hard to intervene as things unfold in real-time, we suggest that conference organizers provide a specific contact where members can report unethical or inappropriate incidents.

11. Sexual harassment is a major obstacle encompassing all career stages

A recent exhaustive report on sexual assault led by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, and funded by the NIH, reported that rates of sexual harassment are as high as 58% for academic faculty and staff and between 20 to 50% for students. The majority of the sexual harassment experienced by women in academia consists of sexist hostility. These unacceptable rates are higher than any other work environment except for the military ( Johnson and Smith, 2018 ). The consequences of harassment are far-reaching and require widespread efforts to reduce these high rates if we are to see gender parity in a scientific workplace.

Sexual harassment falls into four main categories: micro-aggression (i.e., comments or actions that express prejudiced attitudes), sexual coercion, unwanted sexual attention, and gender harassment (see National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018 for detailed review). Harassment consists of actions that create a hostile and inequitable environment for members of a specific group. Harassment is not limited to the extreme form of physical assault; it also includes endorsing beliefs that someone’s intelligence is inferior to another’s, or making demeaning jokes that target one gender group.

Unfortunately, all types of sexual harassment are common and lead to negative outcomes for the people who experience them. In addition to the 58% of academic faculty or staff who experienced sexual harassment, 38% of women trainees and 23% of men trainees experienced sexual harassment from faculty ( Johnson and Smith, 2018 ). More egregious numbers are found in specific fields; a recent study reports that 75% of undergraduate women majoring in physics experienced sexual harassment ( Aycock et al., 2019 ). While peer-to-peer harassment is also prevalent, trainees experience worse professional outcomes when faculty at their university conducted the harassment. These numbers may underestimate the problem, as trainees might not feel comfortable speaking up when their career development, and sometimes even legal status in a country, depends on the person harassing them. In another study of 474 scientists, 30% of women reported feeling unsafe at work, compared to 2% of men ( Clancy et al., 2017 ). The rates were even higher for women of color, where almost 50% of women scientists of color reported feeling unsafe at work ( Clancy et al., 2017 ). These experiences are chronically stressful and have been linked to higher levels of depression, anxiety, and generally impaired psychological well-being ( Lim and Cortina, 2005 ; Parker and Griffin, 2002 ). People who have experienced sexual harassment report higher rates of absenteeism, tardiness, and use of sick leave (measured on scales where respondents indicated desirability, frequency, likelihood, and ease of engaging in these behaviors) and unfavorable job behaviors (e.g., making excuses to get out of work, neglecting tasks not evaluated on performance appraisal) ( Schneider et al., 1997 ). Finally, and not surprisingly, individuals who experience sexual harassment are more likely to leave their jobs. All of these statistics demonstrate that sexual harassment is both alarmingly common and reduces the scientific productivity and well-being of the people who have been harmed. Yet, when this behavior is reported, the whistle-blowers may be either retaliated against or there may be no repercussions for the perpetrators. Moreover, even the policies that aim to ‘protect’ victims of harassment have substantial negative consequences, which are more likely to occur to women than men. These include reluctance to have one-to-one meetings with women or to include them in social events, or reluctance to hire women for positions that require close contact with them ( Atwater et al., 2019 ).

Collegial behavior, that does not propagate harassment and micro-aggressions should be the bare minimum expectation in any lab or academic institution. Individuals of all levels should consider their personal responsibility to promote a respectful and professional environment, avoid and denounce unwelcome behavior when witnessed. Besides everyone’s own responsibility, it is essential that organizational leaders display an unequivocal anti-harassment message ( Buchanan et al., 2014 ).

Sexual harassment cannot be tolerated and must be severely reprehended by institutions. Although some initiatives for combating harassment exist, there is to date no evidence that current policies have succeeded in reducing harassment (ACD Working Group on Changing the Culture to End Sexual Harassment). To counter this ineffectiveness, the NIH has recently recommended that sexual harassment needs to be equated to scientific misconduct, including similar mechanisms for reporting, investigation, and adjudication.

Researchers found guilty of sexual harassment could be barred from applying for new grants over a period of years deemed appropriate by the various regulatory entities similar to the penalty for scientific misconduct. Examples of such entities in the USA would be the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), their Office of Research Integrity (ORI), and the NIH. Importantly, the committees involved in investigating and adjudicating harassment should be independent from the institution leaders ( Greider et al. 2019 ).

One solution often proposed to combat sexual harassment is anti-harassment training. This consists of requiring students and staff to participate in workshops detailing sexual harassment policies and what constitutes unwelcome behavior. This approach has been widely suggested, and is currently implemented in several institutions despite its debatable effectiveness in reducing harassment. Indeed, it has been shown that some approaches could have the opposite effect, with men being less likely to judge a situation as harassment after receiving training, and leading to gender stereotype reinforcement ( Roehling and Huang, 2018 ). Moreover, empirical studies have shown that training employees to recognize what constitutes harassment can be followed by decreases in women managers ( Dobbin and Kalev, 2019 ). By contrast, training managers to recognize signs of harassment and intervene, results in increases in women managers ( Dobbin and Kalev, 2019 ). This seeming discrepancy may be due to gender differences in perception of harassment, so that women are more likely to believe victims of harassment. Departments need to carefully design their sexual harassment training as studies have reported that the designs of such training are essential and need to be adapted to the targeted populations ( Dobbin and Kalev, 2019 ). Interventions that place trainees as allies, such as bystander intervention training (Bringing in the Bystander®), showed positive effects on sexual harassment prevention in academia and military sectors ( Buchanan et al., 2014 ; Cares et al., 2015 ; Katz and Moore, 2013 ; Potter and Moynihan, 2011 ). For instance, Potter et al. (2019) are developing videogames to educate college students bystander intervention skills in situations of sexual harassment and stalking.

One example of a novel, yet untested approach is the ‘Respect is Part of Research’ initiative by graduate students in the University of California Berkeley Physics Department. During these trainings, participants discuss case studies in small groups together with a facilitator, addressing what is wrong about the behavior of the actors in the example, separating intent from impact, and methods to resolve the situation. Providing trainees with the tools to handle difficult situations and creating a supportive community has the potential to significantly shift the culture towards more respectful behavior in academia. However, its effectiveness for combating harassment in the long-term still remains to be tested.

Another factor that can assist in reducing harassment is adopting clear anti-harassment policies in codes of conduct (Why and How to Develop an Event Code of Conduct), both at conferences, and in individual labs. Enforcing a code of conduct is a challenging task, and future efforts should focus on drafting clear policies for different scenarios.

To lower the rates of sexual harassment, all members of the scientific community, and the community at large, need to make widespread changes. Learning to recognize sexual harassment should be an ongoing goal for any nation, starting with education in schools. We recommend that all organizations develop programs charged with reducing the prevalence of sexual violence, sexual harassment, and stalking through prevention, advocacy, training, and healing (for example see the Path to Care center from University of California Berkeley). This approach is distinct from and complementary to the purpose of official university legal procedures (e.g., Title IX in the USA): while such officers legally arbitrate gender discrimination disputes, the University Program we envision would be dedicated to serving the survivors of sexual harassment, preventing new cases, and training the university-wide community.

12. Encompassing all sectors: family planning in academia

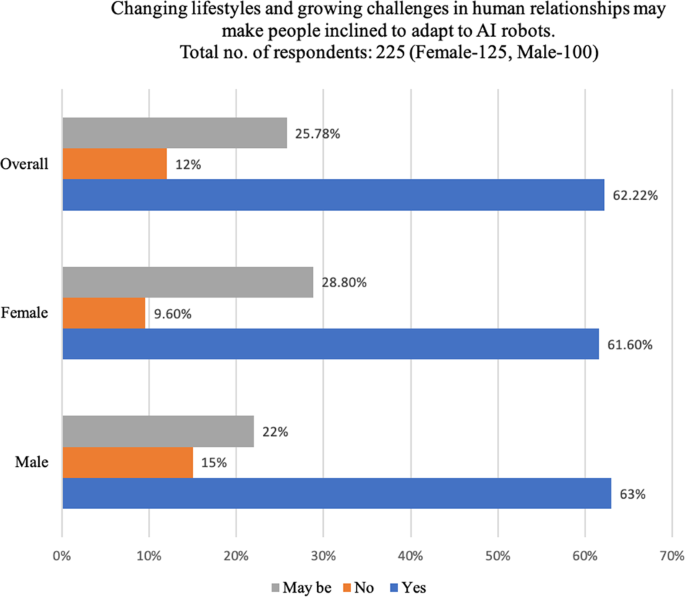

Gender inequity exists in the division of household labor. Women typically shoulder most of the burden in childcare and in maintenance of the household, even among dual career partners ( Chopra and Zambelli, 2017 ). Women have increasingly joined the paid labor force, increasing their total work time, but men have not increased the amount of time they spend in unpaid household work. The COVID-19 pandemic is the most recent evidence of the impact of gender inequality in the labor market ( Alon et al., 2020 ). During the lockdown, women scientists submitted fewer manuscripts and started fewer research projects than men ( Viglione, 2020 ), consistent with an additional and disproportionate burden of childcare. While the majority of studies consider households composed of one man and one woman, further work is needed to evaluate the relations between gender and labor in single-parent homes or same-gender parent homes.

Although academia has its perks for the single parent, same-gender parent, and different-gender parent families, such as flexible hours and additional time to tenure, other working conditions can become barriers for family planning. Career stages where funding and mobility are critical, such as transitions between graduate school, postgraduate training, and tenure positions, often correspond to a time when researchers may wish to start a family (see Figure 1 ). However, pregnancy, childbirth, nursing, parental leave, and early childcare take a considerable amount of time, physical and mental resources, and money that constitute a competitive disadvantage in a scientific career. Indeed, parental leave negatively impacts metrics of productivity of early career scientists who are parents ( Chapman et al., 2019 ), yet with a stronger effect for women ( Morgan et al., 2021 ); which in turn impacts the possibility to obtain grant funding (i.e., several calls are limited to a certain amount of years post-degree according to funding agency policies).

Women with children are reluctant to attend conferences due to the lack of childcare support ( Calisi and a Working Group of Mothers in Science, 2018 ). Conferences in distant locations add another layer of complexity, as transoceanic flights often mean a longer stay away from home. Adequate facilities such as lactation rooms are rarely provided, nor are support for a traveling caretaker to assist in the care of their infant as the scientist attends the meeting. This limited mobility reduces parents’ opportunities for international collaborations and funding, which are common criteria used for promotion and evaluations.

Importantly, women face even stronger discrimination when they are part of non-traditional family formations: single mothers experience a stronger work-family strain than partnered ones ( Baxter and Alexander, 2008 ). Studies of single mother doctoral students have shown that they fear being judged in their departments, and that they often feel excluded by university life and academic schedules ( AmiriRad, 2016 ). Although LGBTQ+ parents face similar challenges as cisgender and heterosexual parents ( King et al., 2013 ), LGBTQ+ individuals might have fewer health or retirement benefits, and face unequal treatment in academia ( Cech and Waidzunas, 2021 ; Thompson and Parry, 2017 ). Future studies should address the particular challenges and biases faced by single parent and LGBTQ+ families and their potential impact on academic achievements.

Apart from the academic aspect, most societies are not built to assist families where both parents pursue a demanding career path. For instance, public schools in some countries like Germany often stop in the early afternoon, and it can be hard to find public preschool or after school childcare. Moreover, working mothers often feel stigmatized as they risk being looked down upon by citizens of more “traditional” societies for their choices to work instead of staying at home with their children.

Parents should not have to choose between having a family and an academic career. Evaluation of academic progress should take into consideration delays caused by parenthood and childcare responsibilities. Individuals should also assess their own possible tendencies to judge or exclude academics with young children, and become prepared to support initiatives that would encourage their participation in gatherings, conferences, and other professional activities.

Institutions need to adopt official extensions of graduate, postdoctoral, and tenure timelines due to childbirth and parenthood. To address the financial difficulties for academic families, we suggest a number of measures. First, job security can be improved by creating longer-term contracts where possible, and by providing bridge funds at the department or university level to support trainees during gaps in funding ( Stewart and Valian, 2018 ). Both universities and funding institutions should put measures in place to prevent a gap in funding during parental leave ( Powell 2019 ). Special provisions for parenthood can be made in calls for proposals and funding mechanisms. A few funding organizations include childbirth in their policies as a valid reason to extend the eligibility window (from one year for NIH K awards to 18 months for ERC grants, or a 2 year extension to post-PhD limits per child for the Emmy Noether Program of the German Research Foundation), or subtract time for parental leave (“Research Project for Young Talent” proposed by the Research Council of Norway, 2–7 years post-PhD). Finally, efforts should be made to reduce the difficulty in returning to work after maternity leave, such as providing lactation rooms.