Become an Insider

Sign up today to receive premium content.

What Is Educational Technology (Ed Tech), and Why Should Schools Invest in It?

Alexandra Shimalla is a freelance journalist and education writer.

Long gone are the days of overhead projectors and handwritten papers. Today’s teachers have robust technology at their disposal, and students have grown up in an increasingly digital world . But, with so many software applications, devices and other technologies on the market, it’s easy for teachers to become overwhelmed with the array of opportunities available to them.

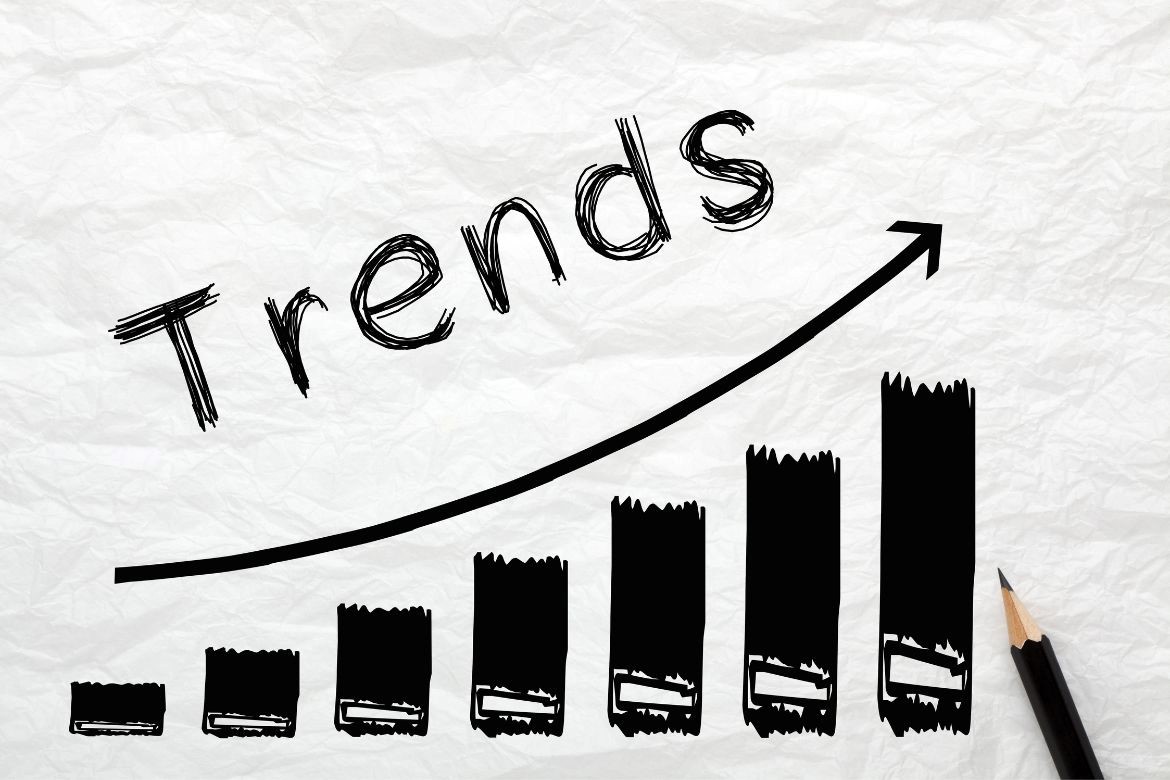

K–12 schools used, on average, 2,591 ed tech tools during the 2022-2023 school year, according to a Statista survey. This is a 1.7 percent increase from the 2021-2022 school year and a nearly 190 percent increase from the 2018-2019 school year, when districts used an average of 895 tools.

With all the technologies available, K–12 IT leaders and administrators need to ensure they’re selecting the right tools for their users. The best way to ensure educational technology is being used is to invest in software and hardware that are valuable to both students and teachers.

Click the banner to learn how to optimize your school’s device lifecycle.

What Is Ed Tech in K–12 Schools?

Educational technology, or ed tech, encompasses a wide variety of applications, software, hardware and infrastructure components — from online quizzes and learning management systems to individual laptops for students and the access points that enable Wi-Fi connectivity.

Interactive panels are a popular tool, and schools have recently implemented learning management systems that allow parents to connect with teachers. Even virtual and augmented reality can be found in some classrooms, says Rachelle Dené Poth, who teaches Spanish and STEAM (science, technology engineering, art and math) classes at Riverview School District . An International Society for Technology in Education–certified educator, Poth is also an attorney and author.

“AR and VR transform how students are learning by immersing them in a different environment, giving them a more hands-on, authentic and meaningful experience,” says Poth. “This enables them to better connect with the content in a way that they understand and can build upon, leveraging the new with the knowledge they already have.”

MORE ON EDTECH: Emerging technologies for modern classrooms steal the spotlight.

What Is the Value of Educational Technology Today?

Even if the district doesn’t have the latest VR tech, educational technology still plays a vital role in the classroom.

“I think ed tech is necessary in the sense that it allows us to do things that, if we were to go back, I could not imagine doing,” says David Chan, director of instructional technology for Evanston Township High School .

Before Chan joined the administrative team 10 years ago, he spent a decade in the classroom — an experience that he believes allows him to do his job better. Having been in the teachers’ position, he can make more informed decisions from the perspective of how technology can impact, benefit or burden the hundreds of teachers in his school.

“First and foremost, the ed tech should support the teaching and learning,” he says.

Certain ed tech, such as quizzes in the middle of class, can collect and analyze valuable data for teachers in real time, Chan adds. Online quizzes provide snapshots of where students are in the moment, allowing teachers to capitalize on crucial learning opportunities rather than reviewing and grading a handwritten quiz later when that opportunity has passed.

“We have always been able to personalize learning for our students pre-technology; it just took more time, and we had fewer resources,” Poth says. “With the different tools available today, especially with artificial intelligence and robust LMS platforms, it helps us have a better workflow and reduces the amount of time it takes to move between tools.”

The average number of educational technologies K–12 districts used during the 2022-2023 school year

Incorporating technology into the classroom can also highlight potential career paths for students. Through coding, creating a podcast, taking apart a drone or learning graphic design, students can explore various technologies that will likely play a role in their future .

“Technology allows students to get a bit more authentic with projects,” says Chan. “It makes them feel like it’s more than just a school project. It could be something they see themselves doing outside of school.”

What Is the Impact of Educational Technology?

When researching a new educational tool, the first thing to answer is the question of impact: How does this impact and provide value to teachers and students?

“We always want to focus on the why and the how, not the ‘wow’ factor,” says Poth. “Why should we use it, and how is it going to enhance or transform student learning? Because it worked for someone else’s class doesn’t guarantee that it’s going to have the same impact on other students. Always focus on the pedagogical value before purchasing the technology.”

DIVE DEEPER: Planning and administrator support are necessary to sustain devices.

Tech that’s difficult to use presents a significant obstacle to adoption. Narrow the potential list to solutions that don’t require complicated setup for educators, or ensure that the proper training and support are in place. “The best compliment I get from teachers is that they didn’t have to call my team to learn how to use it ,” Chan says.

It’s also crucial to consult the privacy policy of any new technology. Verify that it aligns with the necessary laws and regulations , as well as your school’s own policies.

Tips for K–12 Schools Investing in Ed Tech

Chan’s advice for all ed tech purchases — from trying something new to renewing an existing license — is to be slow and intentional. One of the biggest mistakes schools can make is to jump in too quickly.

“Piloting allows us to scale up in a responsible way,” he says.

After doing the research to ensure a new device or software aligns with the school environment, do a pilot run with a few licenses or devices. Ask teachers and students who participate for feedback. Having those conversations can aid IT teams with the full launch or with other technologies in the future.

Rachelle Dené Poth Spanish and STEAM Teacher, Riverview School District

A helpful tip, shares Chan, is setting up a standard workflow so the IT department is carefully reviewing every item the school pays for before it’s renewed. These checks are opportunities to review existing data from companies to see if the ed tech is being used at the volume expected. If not, don’t be afraid to cut the cord with services, particularly if teachers are unhappy with them, which impacts the return on investment .

Poth suggests enabling single sign-on , which streamlines access and prevents roadblocks to adoption. “It’s super helpful for students and teachers, especially when trying to bring different tools into the classroom.”

Ultimately, ed tech is here to stay, and its presence in the classroom will only increase. Administrators and IT leaders can start by analyzing the tools they currently have, then begin having conversations with teachers and students about ways to improve.

DISCOVER: District sets out to learn how its teachers are using technology.

- Personalized Learning

- Collaboration

- Digital Transformation

- Procurement

- Return on Investment

Related Articles

Unlock white papers, personalized recommendations and other premium content for an in-depth look at evolving IT

Copyright © 2024 CDW LLC 200 N. Milwaukee Avenue , Vernon Hills, IL 60061 Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- BookWidgets Teacher Blog

Lessons from technology - 8 Innovative educational projects

The new school year is about to start all over the world. In the US, it started the 1st of August, In Europe, most schools start on the 1st of September. Nonetheless, a new school year is always exciting. Schools try to surpass themselves every new school year.

To do that, schools set up schoolwide projects, and teachers try to reinvent themselves using their creativity. Frontline Education reached out to us with the idea of combining amazing stories of schools transforming their processes with technology by setting up innovating projects.

This post will show you 8 educational projects that make excellent use of technology to make both small and big changes. We hope that these ideas inspire you.

Innovative classroom projects

1. the camera doesn’t lie.

When we think of innovative technology, terms like artificial intelligence and machine learning certainly come to mind. But teachers at Martin County School District in Florida are enhancing their classrooms with a more ordinary piece of technology — a camera.

“Any serious athlete watches footage of their performances,” April Strong, a former teacher and now instructional coach, told us. “Why not teachers, too?”

April started using video in two ways. First, by watching other experienced teachers who have recorded and shared their teaching videos. Then, by reviewing her own classroom instruction. To get started, she borrowed an iPad from the school’s media center and simply pushed record every single day. The value, she found, was not only in accountability to her craft, but it also brought clarity to her teaching—and still does.

“Video brought clarity to my practice so I could bring the greatest work to my classroom for my students. That’s the power of video. Nobody told me I had to do it. There was no other reason other than it was the perfect time because I was wondering what I truly looked like as a teacher. Video was, and is still, very clarifying. I might be using the most effective strategy ever, but if I don’t actually see it as my students saw it, I’m not growing and I’m not truly clear on if I hit my target. That’s what makes me most passionate about video in the classroom.”

Using video helped shape how April and Martin County School District teachers become the best in their profession. When asked how others should get started, her message was simple: “All you need is your cell phone, and a place to prop it up, and the bravery to literally just push that red button.”

EdTech Hack

2. Johnsonville Learning network

Anthony Johnson is a 4th & 5th-grade science and social studies educator. He’s also an Apple Distinguished Educator, TED Innovative Educator, Lego Master Educator, Defined STEM Certified Educator and Rowan-Salisbury Schools Teacher of the Year for 2016-17. AND the mayor of Johnsonville, his classroom.

Anthony’s classroom, called Johnsonville, focuses on three main elements: collaboration, critical thinking, and citizenship. Anthony’s goal is to inspire a love for learning. Johnsonville is a very busy place that encourages hands-on learning and uses interesting projects to teach students everything about science and social studies.

He uses “Hotweels” to teach students the basics of physics like Newton’s third law, “Spheros”, “Lego” and drones to teach them about forces and motion, and a 3D printer to teach them about the human body. Check out how he does this right here:

Innovative school-wide projects

3. ar school wall.

Augmented Reality is an excellent tool to plan an interactive learning walk in your school to show (new) parents around. Only recently, principal Joost Dendooven of the Mozaiek primary school in Belgium renovated his school’s hallway with a new eye-catcher: a photo wall.

The school selected more than 400 photos out of the school’s archive and placed them on the wall. Then, the school added an augmented reality effect to the photos on the wall using the HP Reveal app. In order to add augmented reality effects to the photo wall, the school looked for interesting newspaper articles and fun videos about their school activities.

When parents or other visitors enter the hallway, they get an iPad or iPhone with the installed AR-app. All they have to do is scan a particular photo on the photo wall with their device and the image will come to life with some background information, a newspaper article or a video.

Even around the school and on the playground, they added AR-effects with videos and explanations of school activities that took place.

4. Cutting Edge Rural

Forty-five miles west of Columbus, Ohio sits Graham Local Schools in rural Champagne County. Three buildings make up the entire school district: one elementary building, a middle school, and a high school. Rolling hills and fertile farmland are abundant in this section of Ohio, access to professional development and neighboring resources, however, are not. So when then-superintendent Dr. Kirk Koennecke began his role, his challenge was making sure teachers had opportunities to grow while balancing budgeting needs and the reality of how far a district can send their teachers for those opportunities.

That’s where technology and innovative thinking came in.

Like many rural districts, it’s not always easy for Graham Local Schools to access in-person professional development, so they began using a blended learning model, allowing remote teachers to learn on their own time, in the way that works best for them.

“We’ve really tried to become more progressive and personalize a model of professional learning at Graham where teachers get to choose from a menu of opportunities, most of which are led by our own staff.”

Dr. Koennecke utilized personalized learning pathways, where teachers can choose an area of development, allowing them to feel a greater connection to their educational journey. He wanted to empower his teachers and even started encouraging them to meet students and professionals where they are — on any platform.

“The last thing that we did is, we’ve tried to push social media use with our teachers. While we don’t require it, I’m very proud of the way the use of Twitter and Facebook and Instagram have grown in our district to try to meet people where they are, especially now students. Our Instagram accounts are growing and growing because we’re trying to push information to students. But Twitter is a way that all of our leaders and many of our teachers not only share and celebrate information in each other, but also learn.”

5. Appy Day

As there are many interesting educational events around the globe, the Primary school “Mozaiek” is worth your visit (if you’re from Belgium of course). Every school that focuses on using technology to optimize a students’ learning outcomes should consider sharing their ideas by organizing an inspirational day for all educators in the environment. It’s very important that other principals and educators learn from each other and step out of their comfort zone. There’s only so much to learn.

Appy Day focuses on practical classroom examples and several “spark”- sessions. 6 Belgian Top teachers share their knowledge of how an iPad can be the lever to a powerful learning environment. Appy Day also teaches visitors how a school can transform digitally in the most efficient way. Maybe your school is next to organize an “Appy Day”.

Innovative world-wide school projects

6. the kakuma project.

Koen Timmers , a top-10 Global teacher award nominee, is the driving force behind the Kakuma Project project. This project, started in 2015, is a group of more than 350 teachers from 75 countries over 6 continents willing to offer free education via Skype. They sent some laptops to the Kakuma Refugee Camp (Kenya), and started to teach via Skype.

Imagine up to 200 students taking a look at one single laptop screen. The teachers teach courses like Maths, Science, English, and Religion to the refugees.

Besides the main goal – to educate refugee students – this project also connects students from all over the world with the refugee students so they get a better understanding of what “living as a refugee” actually means.

7. The innovation playlist

First, watch this video that raises an important question: “What is school for?”.

Now, dive into these important questions: To what extent does this video reflect the perspectives of different constituencies in your school community? Would you be willing to ask your students to watch it? Why or why not?

Rather difficult isn’t it? This video is one of the many resources on the innovation playlist, a playlist that wants to encourage educators and principals to change the old fashioned school system for the better. The Innovation Playlist can help your school make a positive and informed change. It represents a teacher-led model, based on small steps leading to big change. It shows you best practices from innovating educators and non-profits from across the US.

8. Teach SDGs

Teach SDGs stands for teaching Sustainable Development Goals. There are 17 SDG’s, such as “No poverty”, “Clean water and sanitation” or “Life below water”.

Teaching students about these topics and making them aware of these world problems is one thing. Engaging them to step up is another. Students need to look for “solutions” and pitch their idea. They can use social media and other tools to shape their project.

To give you an idea of the impact students can have: A school in Canada used a 3D printer to print coral reefs, a technique to make sure that the real coral reefs don’t fade. Another school found out about mealworms that consume plastic.

During this project, students make videos of what they’ve learned and share them with other schools so they learn from each other across the globe.

Looks like you got some new ideas for the starting new school year. I hope these innovative projects inspired you to think bigger and more creative. Or that they simply gave you some new ideas on how to develop your own teaching skills. If you need more on professional development, this post helps you to get started. And if you’re looking to digitize your lessons, you should try out BookWidgets . 👍

Join hundreds of thousands of subscribers, and get the best content on technology in education.

BookWidgets enables teachers to create fun and interactive lessons for tablets, smartphones, and computers.

- Become a Member

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computational Thinking

- Digital Citizenship

- Edtech Selection

- Global Collaborations

- STEAM in Education

- Teacher Preparation

- ISTE Certification

- School Partners

- Career Development

- ISTELive 24

- 2024 ASCD Annual Conference

- Solutions Summit

- Leadership Exchange

- 2024 ASCD Leadership Summit

- Edtech Product Database

- Solutions Network

- Sponsorship & Advertising

- Sponsorship & Advertising

- Learning Library

The Hottest Topics in Edtech in 2021

- Professional Development & Well-Being

For a few years now, we’ve shared the hottest edtech trends of the year based on the topics resonating with educators at the annual ISTE conference. Although the topics themselves often don’t change much from year to year, the approach to them does. But 2020 was a year like no other, and thus new topics emerged on the list and others moved up a few notches.

Digital citizenship, professional learning and social-emotional learning still made the list like they did the year before, but they took on new urgency as schooling moved online. Meanwhile, topics like e-sports, online learning design and creativity were new to the list.

All these topics will be well represented at ISTELive 21 this year. The fully online conference will run for four days, June 26-30. Here’s a look at the trending topics and why they are especially important now.

1. Digital citizenship

Digital citizenship has been a hot topic for educators for nearly a decade — but it has quickly evolved in the past two years — especially in the past year as remote and hybrid learning has shifted learning online.

In the beginning, digital citizenship was focused on safety, security and legality (protect your passwords, keep your identity secret, and cite sources when using intellectual property). Now the focus is on making sure students feel empowered to use digital tools and platforms to do good in the world — and that they do so responsibly.

The DigCitCommit movement was born out of this shift to focus on the opportunities of the digital world rather than the dangers. DigCitCommit breaks down digital citizenship into five focus areas:

Inclusive: Open to multiple viewpoints and being respectful in digital interactions. Informed: Evaluating the accuracy, perspectif and validity of digital media and social posts. Engaged: Using technology for civic engagement, problem solving and being a force for good. Balanced : Prioritizing time and activities online and off to promote mental and physical health. Alert : Being aware of online actions and their consequences and knowing how to be safe and ensuring others are safe online.

Look for digital citizenship sessions at ISTELive 21 that focus on global collaboration, media literacy and social justice projects.

2. Online learning design

One of the biggest challenges educators have faced in responding to the pandemic has been how to effectively move lessons that were designed for an in-person classroom online. Many educators around the world had to make that transition in less than a week in spring 2020 and, in some cases, less than a day.

What many discovered immediately was that you just can’t simply upload worksheets to Google Classroom and expect the same learning success.

Michele Eaton, author of the book, T he Perfect Blend: A Practical Guide to Designing Student-Centered Learning , says good in-person teaching doesn’t equate with good online teaching.

“I have a strong belief that if all we ever do is replicate what we do face to face, then online learning will just be a cheap imitation of the classroom experience.” In her post, 4 tips for creating successful online content , Eaton outlines ways educators can design online lessons that are interactive, reduce cognitive load, and build in formative assessments.

Look for ISTELive 21 sessions that focus on online learning strategies and ideas for the hybrid classroom. Check out ISTE’s Summer Learning Academy, a course designed to help educators take what they learned from teaching in online and hybrid settings and moving to the next level.

3. Equity and inclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed many of the ugly inequities that have existed in education for a long time. It also created a few new ones. When school moved online, many young learners and students with disabilities were unable to access learning without parental help, which was often unavailable because parents were working.

The lack of devices and bandwidth hampered many rural and low income students. Most districts were able to secure funding to get hotspots and laptops or tablets into the hands of students who needed them, but those solutions were not always ideal. Hotspots were at times unreliable and devices would be in disrepair. Because of these problems and others, many teachers reported a high percentage of missing students — those who never showed up online.

Patricia Brown, an instructional technology coach for Ladue School district in Missouri, said the pandemic has been a watershed moment. In the blog, COVID-19 Thrusts Digital Equity to the Forefront , Brown shares some of the complexities of the inequities wrought by the pandemic.

“It’s definitely bringing some attention to things that a lot of people have been talking about and nobody was listening to,” Brown said. “Now, when it affects people in their own communities, they are realizing they don’t have it together like they thought they had it together. People are having their eyes opened.”

Those inequities aren’t just limited to ensuring students have devices and internet access. Brown says there are multiple dimensions of digital equity. One focus is on the need for professional learning and providing support for teachers, students and families.

“When we talk about equity, we can talk a lot about devices and curriculum, but we also have to think about the basic needs that our kids and our families have,” Brown said. “We need to think about those basic needs, whether that’s providing lunches or breakfasts, or social-emotional resources for families or having counselors and social workers available,” Brown said. “That’s part of equity, too, providing what is needed for your population or for your community.”

4. Social-emotional learning and cultural competence

We’ve lumped these two important topics together because much of the anxiety and trauma students have faced during the pandemic relate to both. Social-emotional learning, or SEL, involves the skills required to manage emotions, set goals and maintain positive relationships, which are necessary for learning but also a tall order for students facing a barrage of COVID-related issues like family job loss, stressed parents and the illness or death of friends or relatives.

The pandemic has caused enormous emotional stress and trauma to students across the board, but the emotional effects have disproportionately affected students of color, English language learners and students in other marginalized groups.

That’s why in order to help students process their emotions, it’s important for educators to have cultural competence, which is the ability to understand, communicate with and interact with people across cultures.

In the blog, 3 Ways Teachers Can Integrate SEL Into Online Learning , educator Jorge Valenzuela writes that “dealing with the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic has caused multiple traumas — which have been heightened by news and graphic images of the murder of George Floyd and the outrage and fear that followed.”

That is why he says all educators should seek out cultural competence training in addition to learning about restorative justice, trauma-informed teaching and culturally responsive teaching.

5. Professional development

Teacher professional development, especially related to edtech, is nothing new, of course. But the pandemic changed that, too. No longer are teachers attending daylong face-to-face lectures at the district office or out-of-town seminars and events.

Because of social distancing, the urgency to quickly learn new skills, and increasingly tight budgets, many educators have formed professional learning communities within their schools and districts. Some of these are grouped by grade level, others by content area. In her post, 4 Benefits of an Active Professional Learning Community , Jennifer Serviss explores how PLCs enhance teaching and learning.

Many educators have sought PD online — some for the first time. Those used to attending conferences in person might feel at sea trying to plan for and navigate a virtual conference. In her post, 10 Tips for Getting the Most out of a Virtual PD Event , Nicole Zumpano, a regional edtech coordinator, shares ideas for making the most out of virtual PD.

It can seem daunting to choose the most worthwhile online conferences and courses in a learning landscape flooded with choices. Probably the best way to select: Look to the trusted sources. ISTE offers online courses and a slate of virtual events to prepare educators for the future of learning.

Esports — aka competitive video gaming — has exploded as a form of entertainment in the past decade, and now it’s naturally finding its way into schools, clubs and after-school programs. Many educators are embracing esports as a way to engage hard-to-reach students who don’t necessarily gravitate to athletic sports or academic pursuits. Research indicates that 40% of students involved in esports have never participated in school activities.

Esports also promote interest in STEM careers and are a pipeline to jobs in the burgeoning esports industry.

Kevin Brown, an esports specialist with the Orange County Department of Education in California, says educators can tap esports in the classroom to support just about every subject because esports connect student interests to learning in a positive way.

Brown says esports have seen explosive growth in the last few years. The North America Scholastic Esports Federation started as a regional program in Southern California with 25 clubs and 38 teams. In 2½ years, it has grown to include more than 1,000 clubs and 11,000 students in North America.

Many educators mistakenly believe that if they aren’t gamers themselves, they can’t incorporate esports in the curriculum or organize a club. Not true, says Joe McAllister, an education esports expert for CDW who helps schools and districts get programs off the ground.

He often sees reluctance from people who say, “Oh, I don't really play video games.”

“That’s OK. Do you do enjoy kids growing and learning and providing them structure? Of course, that’s what teachers do,” he said. “The content and strategy for the games, that’s all out there on YouTube and Twitch. Most students will bring that to the table.”

Esports was the topic of a daylong series of events at ISTE20 Live in December and will be a focus again at ISTELive 21. In the meantime, check out the ISTE Jump Start Guide " Esports in Schools ."

7. Augmented and virtual reality

Pokemon Go may have introduced the terms virtual and augmented reality to a majority of educators in 2017, but there’s a lot more learning potential in AR/VR than chasing around imaginary creatures. The game that took the world by storm has faded in popularity these days but AR/VR has not.

The reason for that, says Jaime Donally, author of the ISTE book, The Immersive Classroom: Create Customized Learning Experiences With AR/VR , is because AR/VR deepens learning. It allows students to see the wonders of the world up close and it grants them access to experiences that they wouldn’t be able to get any other way, such as an incredibly detailed 3D view of the human body or a front row seat to unfolding world events.

The technology is becoming more affordable and sophisticated all the time, allowing students to do more than consume AR/VR experiences. They can actually create them.

Most of the AR experiences in the past 10 years involved using a trigger image to superimpose an object or video on top. The trigger image is similar to a barcode telling the mobile device precisely what to add to the image. Newer AR technology eliminates the trigger image and places objects in your space by surface tracking. In the past four years, this technology is included on most mobile devices and uses ARKit for the Apple platform and ARCore for Android, Donally explained, which opens up even more possibilities for students and educators.

8. Project-based learning

At first blush, it seemed like project-based learning, or PBL, would be one of those educational strategies that would have to go by the wayside during remote and online learning. After all, you can’t really organize collaborative projects when students are not together in the same room, right?

“Wrong,” says Nichlas Provenzano, a middle school technology teacher and makerspace director in Michigan.

When the pandemic hit, Provenzano was teaching an innovation and design class, and it wasn’t immediately clear how he could teach that class remotely. He decided to implement genius hour, the ultimate PBL strategy. Genius hour is an instructional approach that allows students to decide what they want to learn and how they want to learn it. The teacher’s job is to support the student by offering resources and helping them understand complex material.

He told his students to create something using the resources they had at home. One student submitted images demonstrating his ability to build a side table that he designed himself.

Another student hydro-dipped some shoes and then created a website to demonstrate the process.

“This approach to personalized learning was a huge success in my middle school class just like it was in my high school class,” Provanzano says in the video, “ The emphasis on personalization increases engagement, but more importantly, it builds the skills necessary to be lifelong learners long after they leave our classrooms.

Learn how to infuse project-based learning in your classroom by enrolling in the ISTE U course, Leading Project-Based Learning With Technology .

9. Creativity

Of course creativity is nothing new. Cave drawings dating back to the late Stone Age continue to awe and inspire us, as do the ivory, stone and shell artifacts created by ancient peoples. Nevertheless, creativity is considered a hot topic because educators are embracing more creative and less traditional methods for students to demonstrate skills and content knowledge.

Tim Needles, an art teacher from Smithtown High School in New York, loves to show teachers how to incorporate creativity into all topic areas. In his video “ Digital Drawing Tools for Creative Online Learning ,” he demonstrates how to “draw with code,” using the Code.org lesson called Artist . It merges math and computer science with art.

Needles who has presented at ISTE’s Creative Constructor Lab, is also a big fan of sketchnoting, a method of taking notes by drawing pictures. Sketchnoting is not just a fun method for getting information on paper, it’s a proven strategy backed by learning science to help students recall information.

Nichole Carter, author of Sketchnoting in the Classroom , says that sketchnoting is not about drawing the perfect piece of art. It’s about getting the content on the page. That’s why she says it’s important for teachers to help student improve their visual vocabulary. Watch the video below to understand more about this.

These nine topics represent a mere fraction of the content you'll fine at ISTELive 21. Register today to ensure the best registration price, then return to the site in March to browse the program.

Diana Fingal is director of editorial content for ISTE.

- artificial intelligence

Digital learning and transformation of education

Digital technologies have evolved from stand-alone projects to networks of tools and programmes that connect people and things across the world, and help address personal and global challenges. Digital innovation has demonstrated powers to complement, enrich and transform education, and has the potential to speed up progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) for education and transform modes of provision of universal access to learning. It can enhance the quality and relevance of learning, strengthen inclusion, and improve education administration and governance. In times of crises, distance learning can mitigate the effects of education disruption and school closures.

What you need to know about digital learning and transformation of education

2-5 September 2024, UNESCO Headquarters, Paris, France

Digital competencies of teachers

in Member States of the Group of 77 and China

Best practices

The call for applications and nominations for the 2023 edition is open until 21 February 2024

Upcoming events

Open educational resources

A translation campaign to facilitate home-based early age reading

or 63%of the world’s population, were using the Internet in 2021

do not have a household computer and 43% of learners do not have household Internet.

to access information because they are not covered by mobile networks

in sub-Saharan Africa have received minimum training

Contact us at [email protected]

REALIZING THE PROMISE:

Leading up to the 75th anniversary of the UN General Assembly, this “Realizing the promise: How can education technology improve learning for all?” publication kicks off the Center for Universal Education’s first playbook in a series to help improve education around the world.

It is intended as an evidence-based tool for ministries of education, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, to adopt and more successfully invest in education technology.

While there is no single education initiative that will achieve the same results everywhere—as school systems differ in learners and educators, as well as in the availability and quality of materials and technologies—an important first step is understanding how technology is used given specific local contexts and needs.

The surveys in this playbook are designed to be adapted to collect this information from educators, learners, and school leaders and guide decisionmakers in expanding the use of technology.

Introduction

While technology has disrupted most sectors of the economy and changed how we communicate, access information, work, and even play, its impact on schools, teaching, and learning has been much more limited. We believe that this limited impact is primarily due to technology being been used to replace analog tools, without much consideration given to playing to technology’s comparative advantages. These comparative advantages, relative to traditional “chalk-and-talk” classroom instruction, include helping to scale up standardized instruction, facilitate differentiated instruction, expand opportunities for practice, and increase student engagement. When schools use technology to enhance the work of educators and to improve the quality and quantity of educational content, learners will thrive.

Further, COVID-19 has laid bare that, in today’s environment where pandemics and the effects of climate change are likely to occur, schools cannot always provide in-person education—making the case for investing in education technology.

Here we argue for a simple yet surprisingly rare approach to education technology that seeks to:

- Understand the needs, infrastructure, and capacity of a school system—the diagnosis;

- Survey the best available evidence on interventions that match those conditions—the evidence; and

- Closely monitor the results of innovations before they are scaled up—the prognosis.

RELATED CONTENT

Podcast: How education technology can improve learning for all students

To make ed tech work, set clear goals, review the evidence, and pilot before you scale

The framework.

Our approach builds on a simple yet intuitive theoretical framework created two decades ago by two of the most prominent education researchers in the United States, David K. Cohen and Deborah Loewenberg Ball. They argue that what matters most to improve learning is the interactions among educators and learners around educational materials. We believe that the failed school-improvement efforts in the U.S. that motivated Cohen and Ball’s framework resemble the ed-tech reforms in much of the developing world to date in the lack of clarity improving the interactions between educators, learners, and the educational material. We build on their framework by adding parents as key agents that mediate the relationships between learners and educators and the material (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The instructional core

Adapted from Cohen and Ball (1999)

As the figure above suggests, ed-tech interventions can affect the instructional core in a myriad of ways. Yet, just because technology can do something, it does not mean it should. School systems in developing countries differ along many dimensions and each system is likely to have different needs for ed-tech interventions, as well as different infrastructure and capacity to enact such interventions.

The diagnosis:

How can school systems assess their needs and preparedness.

A useful first step for any school system to determine whether it should invest in education technology is to diagnose its:

- Specific needs to improve student learning (e.g., raising the average level of achievement, remediating gaps among low performers, and challenging high performers to develop higher-order skills);

- Infrastructure to adopt technology-enabled solutions (e.g., electricity connection, availability of space and outlets, stock of computers, and Internet connectivity at school and at learners’ homes); and

- Capacity to integrate technology in the instructional process (e.g., learners’ and educators’ level of familiarity and comfort with hardware and software, their beliefs about the level of usefulness of technology for learning purposes, and their current uses of such technology).

Before engaging in any new data collection exercise, school systems should take full advantage of existing administrative data that could shed light on these three main questions. This could be in the form of internal evaluations but also international learner assessments, such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and/or the Progress in International Literacy Study (PIRLS), and the Teaching and Learning International Study (TALIS). But if school systems lack information on their preparedness for ed-tech reforms or if they seek to complement existing data with a richer set of indicators, we developed a set of surveys for learners, educators, and school leaders. Download the full report to see how we map out the main aspects covered by these surveys, in hopes of highlighting how they could be used to inform decisions around the adoption of ed-tech interventions.

The evidence:

How can school systems identify promising ed-tech interventions.

There is no single “ed-tech” initiative that will achieve the same results everywhere, simply because school systems differ in learners and educators, as well as in the availability and quality of materials and technologies. Instead, to realize the potential of education technology to accelerate student learning, decisionmakers should focus on four potential uses of technology that play to its comparative advantages and complement the work of educators to accelerate student learning (Figure 2). These comparative advantages include:

- Scaling up quality instruction, such as through prerecorded quality lessons.

- Facilitating differentiated instruction, through, for example, computer-adaptive learning and live one-on-one tutoring.

- Expanding opportunities to practice.

- Increasing learner engagement through videos and games.

Figure 2: Comparative advantages of technology

Here we review the evidence on ed-tech interventions from 37 studies in 20 countries*, organizing them by comparative advantage. It’s important to note that ours is not the only way to classify these interventions (e.g., video tutorials could be considered as a strategy to scale up instruction or increase learner engagement), but we believe it may be useful to highlight the needs that they could address and why technology is well positioned to do so.

When discussing specific studies, we report the magnitude of the effects of interventions using standard deviations (SDs). SDs are a widely used metric in research to express the effect of a program or policy with respect to a business-as-usual condition (e.g., test scores). There are several ways to make sense of them. One is to categorize the magnitude of the effects based on the results of impact evaluations. In developing countries, effects below 0.1 SDs are considered to be small, effects between 0.1 and 0.2 SDs are medium, and those above 0.2 SDs are large (for reviews that estimate the average effect of groups of interventions, called “meta analyses,” see e.g., Conn, 2017; Kremer, Brannen, & Glennerster, 2013; McEwan, 2014; Snilstveit et al., 2015; Evans & Yuan, 2020.)

*In surveying the evidence, we began by compiling studies from prior general and ed-tech specific evidence reviews that some of us have written and from ed-tech reviews conducted by others. Then, we tracked the studies cited by the ones we had previously read and reviewed those, as well. In identifying studies for inclusion, we focused on experimental and quasi-experimental evaluations of education technology interventions from pre-school to secondary school in low- and middle-income countries that were released between 2000 and 2020. We only included interventions that sought to improve student learning directly (i.e., students’ interaction with the material), as opposed to interventions that have impacted achievement indirectly, by reducing teacher absence or increasing parental engagement. This process yielded 37 studies in 20 countries (see the full list of studies in Appendix B).

Scaling up standardized instruction

One of the ways in which technology may improve the quality of education is through its capacity to deliver standardized quality content at scale. This feature of technology may be particularly useful in three types of settings: (a) those in “hard-to-staff” schools (i.e., schools that struggle to recruit educators with the requisite training and experience—typically, in rural and/or remote areas) (see, e.g., Urquiola & Vegas, 2005); (b) those in which many educators are frequently absent from school (e.g., Chaudhury, Hammer, Kremer, Muralidharan, & Rogers, 2006; Muralidharan, Das, Holla, & Mohpal, 2017); and/or (c) those in which educators have low levels of pedagogical and subject matter expertise (e.g., Bietenbeck, Piopiunik, & Wiederhold, 2018; Bold et al., 2017; Metzler & Woessmann, 2012; Santibañez, 2006) and do not have opportunities to observe and receive feedback (e.g., Bruns, Costa, & Cunha, 2018; Cilliers, Fleisch, Prinsloo, & Taylor, 2018). Technology could address this problem by: (a) disseminating lessons delivered by qualified educators to a large number of learners (e.g., through prerecorded or live lessons); (b) enabling distance education (e.g., for learners in remote areas and/or during periods of school closures); and (c) distributing hardware preloaded with educational materials.

Prerecorded lessons

Technology seems to be well placed to amplify the impact of effective educators by disseminating their lessons. Evidence on the impact of prerecorded lessons is encouraging, but not conclusive. Some initiatives that have used short instructional videos to complement regular instruction, in conjunction with other learning materials, have raised student learning on independent assessments. For example, Beg et al. (2020) evaluated an initiative in Punjab, Pakistan in which grade 8 classrooms received an intervention that included short videos to substitute live instruction, quizzes for learners to practice the material from every lesson, tablets for educators to learn the material and follow the lesson, and LED screens to project the videos onto a classroom screen. After six months, the intervention improved the performance of learners on independent tests of math and science by 0.19 and 0.24 SDs, respectively but had no discernible effect on the math and science section of Punjab’s high-stakes exams.

One study suggests that approaches that are far less technologically sophisticated can also improve learning outcomes—especially, if the business-as-usual instruction is of low quality. For example, Naslund-Hadley, Parker, and Hernandez-Agramonte (2014) evaluated a preschool math program in Cordillera, Paraguay that used audio segments and written materials four days per week for an hour per day during the school day. After five months, the intervention improved math scores by 0.16 SDs, narrowing gaps between low- and high-achieving learners, and between those with and without educators with formal training in early childhood education.

Yet, the integration of prerecorded material into regular instruction has not always been successful. For example, de Barros (2020) evaluated an intervention that combined instructional videos for math and science with infrastructure upgrades (e.g., two “smart” classrooms, two TVs, and two tablets), printed workbooks for students, and in-service training for educators of learners in grades 9 and 10 in Haryana, India (all materials were mapped onto the official curriculum). After 11 months, the intervention negatively impacted math achievement (by 0.08 SDs) and had no effect on science (with respect to business as usual classes). It reduced the share of lesson time that educators devoted to instruction and negatively impacted an index of instructional quality. Likewise, Seo (2017) evaluated several combinations of infrastructure (solar lights and TVs) and prerecorded videos (in English and/or bilingual) for grade 11 students in northern Tanzania and found that none of the variants improved student learning, even when the videos were used. The study reports effects from the infrastructure component across variants, but as others have noted (Muralidharan, Romero, & Wüthrich, 2019), this approach to estimating impact is problematic.

A very similar intervention delivered after school hours, however, had sizeable effects on learners’ basic skills. Chiplunkar, Dhar, and Nagesh (2020) evaluated an initiative in Chennai (the capital city of the state of Tamil Nadu, India) delivered by the same organization as above that combined short videos that explained key concepts in math and science with worksheets, facilitator-led instruction, small groups for peer-to-peer learning, and occasional career counseling and guidance for grade 9 students. These lessons took place after school for one hour, five times a week. After 10 months, it had large effects on learners’ achievement as measured by tests of basic skills in math and reading, but no effect on a standardized high-stakes test in grade 10 or socio-emotional skills (e.g., teamwork, decisionmaking, and communication).

Drawing general lessons from this body of research is challenging for at least two reasons. First, all of the studies above have evaluated the impact of prerecorded lessons combined with several other components (e.g., hardware, print materials, or other activities). Therefore, it is possible that the effects found are due to these additional components, rather than to the recordings themselves, or to the interaction between the two (see Muralidharan, 2017 for a discussion of the challenges of interpreting “bundled” interventions). Second, while these studies evaluate some type of prerecorded lessons, none examines the content of such lessons. Thus, it seems entirely plausible that the direction and magnitude of the effects depends largely on the quality of the recordings (e.g., the expertise of the educator recording it, the amount of preparation that went into planning the recording, and its alignment with best teaching practices).

These studies also raise three important questions worth exploring in future research. One of them is why none of the interventions discussed above had effects on high-stakes exams, even if their materials are typically mapped onto the official curriculum. It is possible that the official curricula are simply too challenging for learners in these settings, who are several grade levels behind expectations and who often need to reinforce basic skills (see Pritchett & Beatty, 2015). Another question is whether these interventions have long-term effects on teaching practices. It seems plausible that, if these interventions are deployed in contexts with low teaching quality, educators may learn something from watching the videos or listening to the recordings with learners. Yet another question is whether these interventions make it easier for schools to deliver instruction to learners whose native language is other than the official medium of instruction.

Distance education

Technology can also allow learners living in remote areas to access education. The evidence on these initiatives is encouraging. For example, Johnston and Ksoll (2017) evaluated a program that broadcasted live instruction via satellite to rural primary school students in the Volta and Greater Accra regions of Ghana. For this purpose, the program also equipped classrooms with the technology needed to connect to a studio in Accra, including solar panels, a satellite modem, a projector, a webcam, microphones, and a computer with interactive software. After two years, the intervention improved the numeracy scores of students in grades 2 through 4, and some foundational literacy tasks, but it had no effect on attendance or classroom time devoted to instruction, as captured by school visits. The authors interpreted these results as suggesting that the gains in achievement may be due to improving the quality of instruction that children received (as opposed to increased instructional time). Naik, Chitre, Bhalla, and Rajan (2019) evaluated a similar program in the Indian state of Karnataka and also found positive effects on learning outcomes, but it is not clear whether those effects are due to the program or due to differences in the groups of students they compared to estimate the impact of the initiative.

In one context (Mexico), this type of distance education had positive long-term effects. Navarro-Sola (2019) took advantage of the staggered rollout of the telesecundarias (i.e., middle schools with lessons broadcasted through satellite TV) in 1968 to estimate its impact. The policy had short-term effects on students’ enrollment in school: For every telesecundaria per 50 children, 10 students enrolled in middle school and two pursued further education. It also had a long-term influence on the educational and employment trajectory of its graduates. Each additional year of education induced by the policy increased average income by nearly 18 percent. This effect was attributable to more graduates entering the labor force and shifting from agriculture and the informal sector. Similarly, Fabregas (2019) leveraged a later expansion of this policy in 1993 and found that each additional telesecundaria per 1,000 adolescents led to an average increase of 0.2 years of education, and a decline in fertility for women, but no conclusive evidence of long-term effects on labor market outcomes.

It is crucial to interpret these results keeping in mind the settings where the interventions were implemented. As we mention above, part of the reason why they have proven effective is that the “counterfactual” conditions for learning (i.e., what would have happened to learners in the absence of such programs) was either to not have access to schooling or to be exposed to low-quality instruction. School systems interested in taking up similar interventions should assess the extent to which their learners (or parts of their learner population) find themselves in similar conditions to the subjects of the studies above. This illustrates the importance of assessing the needs of a system before reviewing the evidence.

Preloaded hardware

Technology also seems well positioned to disseminate educational materials. Specifically, hardware (e.g., desktop computers, laptops, or tablets) could also help deliver educational software (e.g., word processing, reference texts, and/or games). In theory, these materials could not only undergo a quality assurance review (e.g., by curriculum specialists and educators), but also draw on the interactions with learners for adjustments (e.g., identifying areas needing reinforcement) and enable interactions between learners and educators.

In practice, however, most initiatives that have provided learners with free computers, laptops, and netbooks do not leverage any of the opportunities mentioned above. Instead, they install a standard set of educational materials and hope that learners find them helpful enough to take them up on their own. Students rarely do so, and instead use the laptops for recreational purposes—often, to the detriment of their learning (see, e.g., Malamud & Pop-Eleches, 2011). In fact, free netbook initiatives have not only consistently failed to improve academic achievement in math or language (e.g., Cristia et al., 2017), but they have had no impact on learners’ general computer skills (e.g., Beuermann et al., 2015). Some of these initiatives have had small impacts on cognitive skills, but the mechanisms through which those effects occurred remains unclear.

To our knowledge, the only successful deployment of a free laptop initiative was one in which a team of researchers equipped the computers with remedial software. Mo et al. (2013) evaluated a version of the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) program for grade 3 students in migrant schools in Beijing, China in which the laptops were loaded with a remedial software mapped onto the national curriculum for math (similar to the software products that we discuss under “practice exercises” below). After nine months, the program improved math achievement by 0.17 SDs and computer skills by 0.33 SDs. If a school system decides to invest in free laptops, this study suggests that the quality of the software on the laptops is crucial.

To date, however, the evidence suggests that children do not learn more from interacting with laptops than they do from textbooks. For example, Bando, Gallego, Gertler, and Romero (2016) compared the effect of free laptop and textbook provision in 271 elementary schools in disadvantaged areas of Honduras. After seven months, students in grades 3 and 6 who had received the laptops performed on par with those who had received the textbooks in math and language. Further, even if textbooks essentially become obsolete at the end of each school year, whereas laptops can be reloaded with new materials for each year, the costs of laptop provision (not just the hardware, but also the technical assistance, Internet, and training associated with it) are not yet low enough to make them a more cost-effective way of delivering content to learners.

Evidence on the provision of tablets equipped with software is encouraging but limited. For example, de Hoop et al. (2020) evaluated a composite intervention for first grade students in Zambia’s Eastern Province that combined infrastructure (electricity via solar power), hardware (projectors and tablets), and educational materials (lesson plans for educators and interactive lessons for learners, both loaded onto the tablets and mapped onto the official Zambian curriculum). After 14 months, the intervention had improved student early-grade reading by 0.4 SDs, oral vocabulary scores by 0.25 SDs, and early-grade math by 0.22 SDs. It also improved students’ achievement by 0.16 on a locally developed assessment. The multifaceted nature of the program, however, makes it challenging to identify the components that are driving the positive effects. Pitchford (2015) evaluated an intervention that provided tablets equipped with educational “apps,” to be used for 30 minutes per day for two months to develop early math skills among students in grades 1 through 3 in Lilongwe, Malawi. The evaluation found positive impacts in math achievement, but the main study limitation is that it was conducted in a single school.

Facilitating differentiated instruction

Another way in which technology may improve educational outcomes is by facilitating the delivery of differentiated or individualized instruction. Most developing countries massively expanded access to schooling in recent decades by building new schools and making education more affordable, both by defraying direct costs, as well as compensating for opportunity costs (Duflo, 2001; World Bank, 2018). These initiatives have not only rapidly increased the number of learners enrolled in school, but have also increased the variability in learner’ preparation for schooling. Consequently, a large number of learners perform well below grade-based curricular expectations (see, e.g., Duflo, Dupas, & Kremer, 2011; Pritchett & Beatty, 2015). These learners are unlikely to get much from “one-size-fits-all” instruction, in which a single educator delivers instruction deemed appropriate for the middle (or top) of the achievement distribution (Banerjee & Duflo, 2011). Technology could potentially help these learners by providing them with: (a) instruction and opportunities for practice that adjust to the level and pace of preparation of each individual (known as “computer-adaptive learning” (CAL)); or (b) live, one-on-one tutoring.

Computer-adaptive learning

One of the main comparative advantages of technology is its ability to diagnose students’ initial learning levels and assign students to instruction and exercises of appropriate difficulty. No individual educator—no matter how talented—can be expected to provide individualized instruction to all learners in his/her class simultaneously . In this respect, technology is uniquely positioned to complement traditional teaching. This use of technology could help learners master basic skills and help them get more out of schooling.

Although many software products evaluated in recent years have been categorized as CAL, many rely on a relatively coarse level of differentiation at an initial stage (e.g., a diagnostic test) without further differentiation. We discuss these initiatives under the category of “increasing opportunities for practice” below. CAL initiatives complement an initial diagnostic with dynamic adaptation (i.e., at each response or set of responses from learners) to adjust both the initial level of difficulty and rate at which it increases or decreases, depending on whether learners’ responses are correct or incorrect.

Existing evidence on this specific type of programs is highly promising. Most famously, Banerjee et al. (2007) evaluated CAL software in Vadodara, in the Indian state of Gujarat, in which grade 4 students were offered two hours of shared computer time per week before and after school, during which they played games that involved solving math problems. The level of difficulty of such problems adjusted based on students’ answers. This program improved math achievement by 0.35 and 0.47 SDs after one and two years of implementation, respectively. Consistent with the promise of personalized learning, the software improved achievement for all students. In fact, one year after the end of the program, students assigned to the program still performed 0.1 SDs better than those assigned to a business as usual condition. More recently, Muralidharan, et al. (2019) evaluated a “blended learning” initiative in which students in grades 4 through 9 in Delhi, India received 45 minutes of interaction with CAL software for math and language, and 45 minutes of small group instruction before or after going to school. After only 4.5 months, the program improved achievement by 0.37 SDs in math and 0.23 SDs in Hindi. While all learners benefited from the program in absolute terms, the lowest performing learners benefited the most in relative terms, since they were learning very little in school.

We see two important limitations from this body of research. First, to our knowledge, none of these initiatives has been evaluated when implemented during the school day. Therefore, it is not possible to distinguish the effect of the adaptive software from that of additional instructional time. Second, given that most of these programs were facilitated by local instructors, attempts to distinguish the effect of the software from that of the instructors has been mostly based on noncausal evidence. A frontier challenge in this body of research is to understand whether CAL software can increase the effectiveness of school-based instruction by substituting part of the regularly scheduled time for math and language instruction.

Live one-on-one tutoring

Recent improvements in the speed and quality of videoconferencing, as well as in the connectivity of remote areas, have enabled yet another way in which technology can help personalization: live (i.e., real-time) one-on-one tutoring. While the evidence on in-person tutoring is scarce in developing countries, existing studies suggest that this approach works best when it is used to personalize instruction (see, e.g., Banerjee et al., 2007; Banerji, Berry, & Shotland, 2015; Cabezas, Cuesta, & Gallego, 2011).

There are almost no studies on the impact of online tutoring—possibly, due to the lack of hardware and Internet connectivity in low- and middle-income countries. One exception is Chemin and Oledan (2020)’s recent evaluation of an online tutoring program for grade 6 students in Kianyaga, Kenya to learn English from volunteers from a Canadian university via Skype ( videoconferencing software) for one hour per week after school. After 10 months, program beneficiaries performed 0.22 SDs better in a test of oral comprehension, improved their comfort using technology for learning, and became more willing to engage in cross-cultural communication. Importantly, while the tutoring sessions used the official English textbooks and sought in part to help learners with their homework, tutors were trained on several strategies to teach to each learner’s individual level of preparation, focusing on basic skills if necessary. To our knowledge, similar initiatives within a country have not yet been rigorously evaluated.

Expanding opportunities for practice

A third way in which technology may improve the quality of education is by providing learners with additional opportunities for practice. In many developing countries, lesson time is primarily devoted to lectures, in which the educator explains the topic and the learners passively copy explanations from the blackboard. This setup leaves little time for in-class practice. Consequently, learners who did not understand the explanation of the material during lecture struggle when they have to solve homework assignments on their own. Technology could potentially address this problem by allowing learners to review topics at their own pace.

Practice exercises

Technology can help learners get more out of traditional instruction by providing them with opportunities to implement what they learn in class. This approach could, in theory, allow some learners to anchor their understanding of the material through trial and error (i.e., by realizing what they may not have understood correctly during lecture and by getting better acquainted with special cases not covered in-depth in class).

Existing evidence on practice exercises reflects both the promise and the limitations of this use of technology in developing countries. For example, Lai et al. (2013) evaluated a program in Shaanxi, China where students in grades 3 and 5 were required to attend two 40-minute remedial sessions per week in which they first watched videos that reviewed the material that had been introduced in their math lessons that week and then played games to practice the skills introduced in the video. After four months, the intervention improved math achievement by 0.12 SDs. Many other evaluations of comparable interventions have found similar small-to-moderate results (see, e.g., Lai, Luo, Zhang, Huang, & Rozelle, 2015; Lai et al., 2012; Mo et al., 2015; Pitchford, 2015). These effects, however, have been consistently smaller than those of initiatives that adjust the difficulty of the material based on students’ performance (e.g., Banerjee et al., 2007; Muralidharan, et al., 2019). We hypothesize that these programs do little for learners who perform several grade levels behind curricular expectations, and who would benefit more from a review of foundational concepts from earlier grades.

We see two important limitations from this research. First, most initiatives that have been evaluated thus far combine instructional videos with practice exercises, so it is hard to know whether their effects are driven by the former or the latter. In fact, the program in China described above allowed learners to ask their peers whenever they did not understand a difficult concept, so it potentially also captured the effect of peer-to-peer collaboration. To our knowledge, no studies have addressed this gap in the evidence.

Second, most of these programs are implemented before or after school, so we cannot distinguish the effect of additional instructional time from that of the actual opportunity for practice. The importance of this question was first highlighted by Linden (2008), who compared two delivery mechanisms for game-based remedial math software for students in grades 2 and 3 in a network of schools run by a nonprofit organization in Gujarat, India: one in which students interacted with the software during the school day and another one in which students interacted with the software before or after school (in both cases, for three hours per day). After a year, the first version of the program had negatively impacted students’ math achievement by 0.57 SDs and the second one had a null effect. This study suggested that computer-assisted learning is a poor substitute for regular instruction when it is of high quality, as was the case in this well-functioning private network of schools.

In recent years, several studies have sought to remedy this shortcoming. Mo et al. (2014) were among the first to evaluate practice exercises delivered during the school day. They evaluated an initiative in Shaanxi, China in which students in grades 3 and 5 were required to interact with the software similar to the one in Lai et al. (2013) for two 40-minute sessions per week. The main limitation of this study, however, is that the program was delivered during regularly scheduled computer lessons, so it could not determine the impact of substituting regular math instruction. Similarly, Mo et al. (2020) evaluated a self-paced and a teacher-directed version of a similar program for English for grade 5 students in Qinghai, China. Yet, the key shortcoming of this study is that the teacher-directed version added several components that may also influence achievement, such as increased opportunities for teachers to provide students with personalized assistance when they struggled with the material. Ma, Fairlie, Loyalka, and Rozelle (2020) compared the effectiveness of additional time-delivered remedial instruction for students in grades 4 to 6 in Shaanxi, China through either computer-assisted software or using workbooks. This study indicates whether additional instructional time is more effective when using technology, but it does not address the question of whether school systems may improve the productivity of instructional time during the school day by substituting educator-led with computer-assisted instruction.

Increasing learner engagement

Another way in which technology may improve education is by increasing learners’ engagement with the material. In many school systems, regular “chalk and talk” instruction prioritizes time for educators’ exposition over opportunities for learners to ask clarifying questions and/or contribute to class discussions. This, combined with the fact that many developing-country classrooms include a very large number of learners (see, e.g., Angrist & Lavy, 1999; Duflo, Dupas, & Kremer, 2015), may partially explain why the majority of those students are several grade levels behind curricular expectations (e.g., Muralidharan, et al., 2019; Muralidharan & Zieleniak, 2014; Pritchett & Beatty, 2015). Technology could potentially address these challenges by: (a) using video tutorials for self-paced learning and (b) presenting exercises as games and/or gamifying practice.

Video tutorials

Technology can potentially increase learner effort and understanding of the material by finding new and more engaging ways to deliver it. Video tutorials designed for self-paced learning—as opposed to videos for whole class instruction, which we discuss under the category of “prerecorded lessons” above—can increase learner effort in multiple ways, including: allowing learners to focus on topics with which they need more help, letting them correct errors and misconceptions on their own, and making the material appealing through visual aids. They can increase understanding by breaking the material into smaller units and tackling common misconceptions.

In spite of the popularity of instructional videos, there is relatively little evidence on their effectiveness. Yet, two recent evaluations of different versions of the Khan Academy portal, which mainly relies on instructional videos, offer some insight into their impact. First, Ferman, Finamor, and Lima (2019) evaluated an initiative in 157 public primary and middle schools in five cities in Brazil in which the teachers of students in grades 5 and 9 were taken to the computer lab to learn math from the platform for 50 minutes per week. The authors found that, while the intervention slightly improved learners’ attitudes toward math, these changes did not translate into better performance in this subject. The authors hypothesized that this could be due to the reduction of teacher-led math instruction.

More recently, Büchel, Jakob, Kühnhanss, Steffen, and Brunetti (2020) evaluated an after-school, offline delivery of the Khan Academy portal in grades 3 through 6 in 302 primary schools in Morazán, El Salvador. Students in this study received 90 minutes per week of additional math instruction (effectively nearly doubling total math instruction per week) through teacher-led regular lessons, teacher-assisted Khan Academy lessons, or similar lessons assisted by technical supervisors with no content expertise. (Importantly, the first group provided differentiated instruction, which is not the norm in Salvadorian schools). All three groups outperformed both schools without any additional lessons and classrooms without additional lessons in the same schools as the program. The teacher-assisted Khan Academy lessons performed 0.24 SDs better, the supervisor-led lessons 0.22 SDs better, and the teacher-led regular lessons 0.15 SDs better, but the authors could not determine whether the effects across versions were different.

Together, these studies suggest that instructional videos work best when provided as a complement to, rather than as a substitute for, regular instruction. Yet, the main limitation of these studies is the multifaceted nature of the Khan Academy portal, which also includes other components found to positively improve learner achievement, such as differentiated instruction by students’ learning levels. While the software does not provide the type of personalization discussed above, learners are asked to take a placement test and, based on their score, educators assign them different work. Therefore, it is not clear from these studies whether the effects from Khan Academy are driven by its instructional videos or to the software’s ability to provide differentiated activities when combined with placement tests.

Games and gamification

Technology can also increase learner engagement by presenting exercises as games and/or by encouraging learner to play and compete with others (e.g., using leaderboards and rewards)—an approach known as “gamification.” Both approaches can increase learner motivation and effort by presenting learners with entertaining opportunities for practice and by leveraging peers as commitment devices.

There are very few studies on the effects of games and gamification in low- and middle-income countries. Recently, Araya, Arias Ortiz, Bottan, and Cristia (2019) evaluated an initiative in which grade 4 students in Santiago, Chile were required to participate in two 90-minute sessions per week during the school day with instructional math software featuring individual and group competitions (e.g., tracking each learner’s standing in his/her class and tournaments between sections). After nine months, the program led to improvements of 0.27 SDs in the national student assessment in math (it had no spillover effects on reading). However, it had mixed effects on non-academic outcomes. Specifically, the program increased learners’ willingness to use computers to learn math, but, at the same time, increased their anxiety toward math and negatively impacted learners’ willingness to collaborate with peers. Finally, given that one of the weekly sessions replaced regular math instruction and the other one represented additional math instructional time, it is not clear whether the academic effects of the program are driven by the software or the additional time devoted to learning math.

The prognosis:

How can school systems adopt interventions that match their needs.

Here are five specific and sequential guidelines for decisionmakers to realize the potential of education technology to accelerate student learning.

1. Take stock of how your current schools, educators, and learners are engaging with technology .

Carry out a short in-school survey to understand the current practices and potential barriers to adoption of technology (we have included suggested survey instruments in the Appendices); use this information in your decisionmaking process. For example, we learned from conversations with current and former ministers of education from various developing regions that a common limitation to technology use is regulations that hold school leaders accountable for damages to or losses of devices. Another common barrier is lack of access to electricity and Internet, or even the availability of sufficient outlets for charging devices in classrooms. Understanding basic infrastructure and regulatory limitations to the use of education technology is a first necessary step. But addressing these limitations will not guarantee that introducing or expanding technology use will accelerate learning. The next steps are thus necessary.

“In Africa, the biggest limit is connectivity. Fiber is expensive, and we don’t have it everywhere. The continent is creating a digital divide between cities, where there is fiber, and the rural areas. The [Ghanaian] administration put in schools offline/online technologies with books, assessment tools, and open source materials. In deploying this, we are finding that again, teachers are unfamiliar with it. And existing policies prohibit students to bring their own tablets or cell phones. The easiest way to do it would have been to let everyone bring their own device. But policies are against it.” H.E. Matthew Prempeh, Minister of Education of Ghana, on the need to understand the local context.

2. Consider how the introduction of technology may affect the interactions among learners, educators, and content .