- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Systematic review article, research competencies to develop academic reading and writing: a systematic literature review.

- Tecnologico de Monterrey, Escuela de Humanidades y Educación, Monterrey, Mexico

Rationale: The development of research skills in the higher education environment is a necessity because universities must be concerned about training professionals who use the methods of science to transform reality. Furthermore, within research competencies, consideration must be given to those that allow for the development of academic reading and writing in university students since this is a field that requires considerable attention from the educational field at the higher level.

Objective: This study aims to conduct a systematic review of the literature that allows the analysis of studies related to the topics of research competencies and the development of academic reading and writing.

Method: The search was performed by considering the following quality criteria: (1) Is the context in which the research is conducted at higher education institutions? (2) Is the development of academic reading and writing considered? (3) Are innovation processes related to the development of academic reading and writing considered? The articles analyzed were published between 2015 and 2019.

Results: Forty-two papers were considered for analysis after following the quality criterion questions. Finally, the topics addressed in the analysis were as follows: theoretical–conceptual trends in educational innovation studies, dominant trends and methodological tools, findings in research competencies for innovation in academic literacy development, types of innovations related to the development of academic reading and writing, recommendations for future studies on research competencies and for the processes of academic reading and writing and research challenges for the research competencies and academic reading and writing processes.

Conclusion: It was possible to identify the absence of studies about research skills to develop academic literacy through innovative models that effectively integrate the analysis of these three elements.

Introduction

Research skills today must be developed in such a way that students in higher education will be enabled to make them their own for good. This type of competencies is given fundamentally in the aspects of methodological domain, information gathering and the management of document-writing norms and technological tools. Furthermore, the usefulness of the existence of mediating didactics is recognized ( Aguirre, 2016 ). The competencies considered by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in its skills strategy are the following: the development of relevant competencies, the activation of those competencies in the labor market and the use of those competencies effectively for the economy and society ( OECD, 2017 ). The research competences established by Mogonea and Remus Mogonea (2019) from the implementation of a pedagogical research project are as follows: the acquisition of new knowledge, the identification of educational problems, synthesis and argumentation, metacognition, knowledge of new research methods, the possibility of developing research tools and the interpretation and dissemination of results. Research skills work for various disciplines and can even link them. Some studies have affirmed the value of facilitating interactions between researchers from different research fields within a discipline ( Hills and Richards, 2013 ). Therefore, research competencies are approached from distinct perspectives. In this study, the focus is on those that allow for the development of academic reading and writing, because it is an area that requires a boost because it is basic for undergraduate students to be able to understand texts of different kinds and to be able to write with academic rigor.

Academic writing is one aspect that has been focussed on in the educational context. It is a multiple construction that unites such essential elements as the understanding of the scientific field and the understanding of scientific research methodology, statistical knowledge and the understanding of the culture of native and foreign languages ( Lamanauskas, 2019 ). Currently, a change in expectations has emerged around academic writing, and it has become increasingly evident that a much longer and gradual orientation in the process of research and information gathering is desirable to better meet the needs of contemporary students ( Hamilton, 2018 ). On the basis of historical emphasis on writing instruction, five approaches are illustrated, namely, skills, creative writing, process, social practice, and socio-cultural perspective ( Kwak, 2017 ). Academic writing is thus conceived as a way in which young people can construct their own according to elements that provide academic rigor through an efficient interaction with texts.

Academic reading and writing are a fundamental part of the context of higher education. Academic reading and writing also includes the learning of foreign languages as the gender-based approach to the teaching of writing has been found to be useful in promoting the development of literacy through the explicit teaching of characteristics, functions, and options of grammar and vocabulary that are available to interpret and produce various specific genres ( Trojan, 2016 ). Young university students come from a system of basic and upper secondary education in which the fundamental thing was to learn through the repetition of texts, but now their ideas, knowledge, capacity for analysis and critical thinking are a central aspect ( Bazerman, 2014 ). Understanding reading practices and needs in the context of information seeking can refine our understanding of the choices and preferences of users for information sources (such as textbooks, articles, and multimedia content) and media (such as printed and digital tools used for reading) ( Carlino, 2013 ; Lopatovska and Sessions, 2016 ). In this sense, it is useful to consider academic literacy, a name that Carlino (2013) has given to teaching process that may (or may not) be put in place to facilitate students' access to the different written cultures of the disciplines (p. 370). Currently, the many ways in which students perform the process of academic reading and writing must be addressed so that an improvement in the process can be attained.

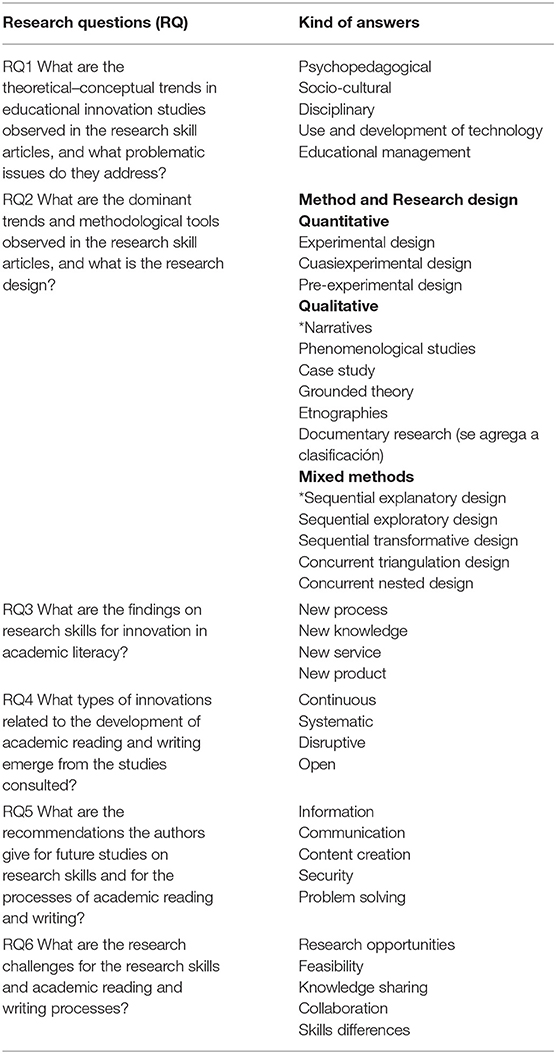

Within the study of research competencies for the development of academic reading and writing, theoretical–conceptual trends and methodological designs play an important role. Ramírez-Montoya and Valenzuela (2019) considered psychopedagogical, socio-cultural, use and development of technology, disciplinary and educational management studies as theoretical–conceptual trends. According to Harwell (2014) , for methodological analysis, the categories of experimental design, quasi-experimental design, pre-experimental design, and within quantitative methods are used, and for qualitative methods, phenomenological, narrative and case studies, grounded theory and ethnography are contemplated. Documentary research is also added because there are studies on this type related to the subject, which are considered to be excluded.

In the research field, the findings and innovation that are increasingly present are a fundamental part. For the area of findings, the classification contemplated by Ramírez-Montoya and Lugo-Ocando (2020) must be considered. The author commented that innovation can create a new process (organization, method, strategy, development, procedure, training, and technique), a new product (technology, article, instrument, material, device, application, manufacture, result, object, and prototype), a new service (attention, provision, assistance, action, function, dependence, and benefit) or new knowledge (transformation, impact, evolution, cognition, discernment, knowledge, talent, patent, model, and system). Various types of innovation are available, such as those addressed by Valenzuela and Valencia (2017) which consider the following: (a) continuous innovation: when small deviations in educational practices accumulate, they translate into profound changes; (b) systematic: it is methodical and ordered like the innovation of continuous improvement, but the scope and novelty of its changes may vary and even lead to substantial changes; and (c) disruptive: they are new contributions to the world and generate fundamental changes in the activities, structure and functioning of organizations. Another type of innovation is open innovation, which is defined by Chesbrough (2006) as the deliberate use of knowledge inputs and outputs to accelerate internal innovation and expand it for the external use of innovation in markets. Educational purposes and divergent contexts can determine the type of innovation applied.

Many factors converge in the development of academic reading and writing. Digital skills are essential elements in enriching academic reading and writing. In the framework for the development and understanding of digital competences in Europe, five areas of digital competences exist, namely, (a) information: judging its relevance and purpose through identifying, locating, retrieving, storing, organizing, and analyzing digital information; (b) communication: taking place in digital environments or using digital tools to link to others and interacting in networked communities; (c) content creation: some elements include creating and editing new content and enforcing intellectual property rights and licenses; (d) security: personal protection, protection of digital identity, and safe and sustainable use and (e) problem solving: some aspects include making informed decisions about which digital tools are best suited for which purpose or need, creatively using technologies and updating the skills of individuals ( Ferrari, 2013 ). The changing environment of higher education offers an uncertain information ecosystem that requires greater responsibility on the part of students to create new knowledge and to select and use information appropriately ( Association of College Research Libraries, 2000 ). The Association of College and Research Libraries 2016 includes some key information literacy (IL) concepts: information creation as a process, information as value, research as inquiry and search as strategic exploration. Academic literacy can be better developed if IL and digital competencies are considered.

Research studies have presented challenges that must be considered for future research. Within the research gaps addressed in the classification of Kroll et al. (2018) for the study of research competencies, some of the categories are appropriate: Research Topic (RT) 1: Collaboration, RT2: Feasibility, RT3: Knowledge Sharing, RT4: Research Opportunities and RT6: Skill Differences. Critical thinking and academic literacy are considered amongst the challenges for developing academic writing from research skills. The first is considered as the process that involves conceptualization, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of the information collected from observation and experience as a guide for belief and action ( Sellars et al., 2018 ). Academic literacy according to Solimine and Garcia-Quismondo (2020) grows within a competency-based educational model, in which competencies are recognized as the developments in the learners of informational behaviors and attitudes that make them expert evaluators of digital and virtual web contents to obtain knowledge and know-how. Reflection and critical thinking are basic elements for an adequate interaction in digital media.

Several items were identified from mapping and systematic literature reviews related to the topics of research skills and academic literacy development. Abu and Alheet (2019) conducted a study to identify those competencies that an individual must possess to be a good researcher. A competency-based assessment throughout the research training process to more objectively evaluate the development of doctoral students and early career scientists is proposed by Verderame et al. (2018) . Moreover, Zetina et al. (2017) concluded that designing strategies for the adequate development of research competencies with the purpose of training sufficiently qualified young researchers is crucial. Walton and Cleland (2017) also presented qualitative research with the purpose of establishing whether students as part of a degree module can demonstrate through their online textual publications their IL skills as a discursive competence and social practice. Lopatovska and Sessions (2016) conducted a study examining reading strategies in relation to information-seeking stages, tasks and reading media in an academic setting.

This study aims to determine how the three elements present in the quality criteria (research skills, academic reading and writing and innovation processes) of this systematic review of the literature can be linked so that they can serve as a basis for identifying which research skills can be used to develop academic reading and writing in higher education contexts through innovative models. IL is presented as a fundamental competence because for the adequate development of academic reading and writing, university students must be able to perform efficiently in the search, selection and treatment of information.

The method followed for the present research was the systematic review of literature [based on Kitchenham and Charters (2007) ], which considers within the phases to follow the review of a protocol to specify the research question. The search started with the articles that emerged from a systematic mapping of literature that was previously carried out; subsequently, quality criteria were defined that allowed refining the selection of articles for the systematic literature review, inclusion and exclusion criteria were also determined, and six research questions were also established for the analysis of the articles.

Research Questions

The starting point was to locate themes that were of interest for investigating writing processes within the framework of research skills and educational innovation to establish research questions. Six questions were located, and possible systems for classifying answers were studied on the basis of the literature. Table 1 lists the questions that guided the study.

Table 1 . Research questions and kind of answers in the systematic literature review.

Search Strategy

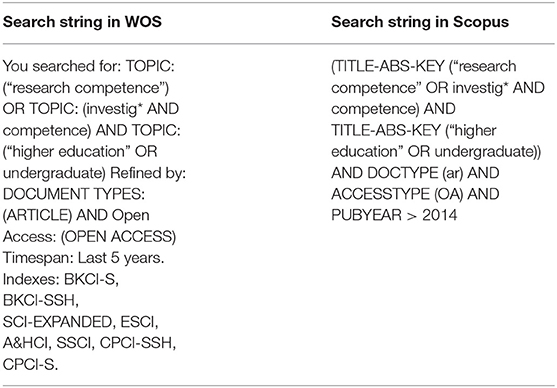

In a systematic mapping of literature (SML) that was previously conducted, the search strings shown in Table 2 were used. The search criteria are explained below.

Table 2 . Search strings in Scopus and WOS.

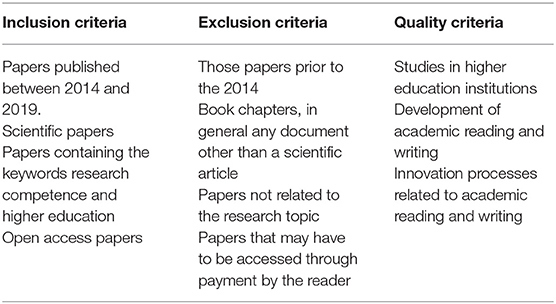

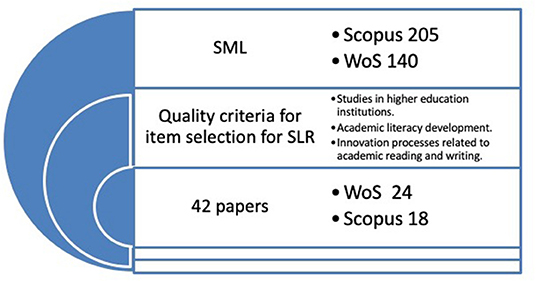

On the basis of the 345 articles that emerged from the search process that was conducted for the previous SML, the following quality criteria were considered for the selection of the articles to be included in this SLR: (a) Is the context in which the study is conducted in higher education institutions, (b) Is the development of academic reading and writing considered?, and (c) Are innovation processes related to the development of academic reading and writing considered? It was contemplated that they would cover at least two of three points to define the articles that would remain for the analysis. In the first instance, 52 articles were left, but those whose language was different from English and Spanish were later excluded, given the poor representativeness of articles written in other languages. Therefore, only 42 papers were finally analyzed.

Inclusion, Exclusion, and Quality Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria must capture and incorporate the questions that the SLR seeks to answer, and the criteria must also be practical to apply. If they are too detailed, then the selection may be excessively complicated and lengthy. For the systematic mapping, the disciplinary areas that had the highest number of articles were Education (40%) and Medicine (36%). For the systematic review of the literature, it was considered that the context for the selection of articles should be limited to higher education institutions. Table 3 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the SML and the quality criteria for article selection.

Table 3 . Inclusion, exclusion, and quality criteria.

Finally, after applying the quality criteria, there were 42 articles left to be analyzed in the SLR, which are shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4 . Articles that were analyzed.

RQ1 What are the theoretical–conceptual trends in educational innovation studies observed in the research skill articles?

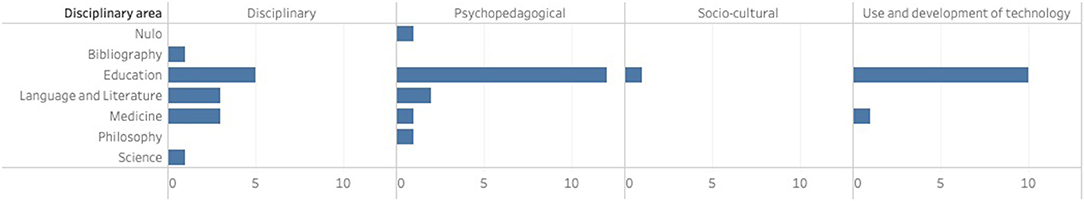

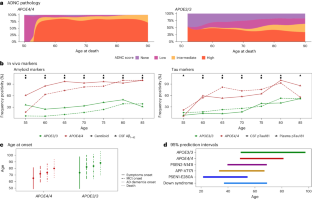

The 42 articles analyzed the disciplinary approaches according to the Library of Congress Classification, which made it possible to place them in the six disciplines referred to in this study and allowed their correspondence with the theoretical–conceptual trends of educational innovation (psychopedagogical, socio-cultural, disciplinary, use and development of technology and educational management), where a greater preponderance was found in articles under the heading of Psychopedagogical Studies (1, 2, 7, 8, 16–18, 20, 22, 24, 29, 30, 32, 34–36, 38), as shown in Figure 2 .

The disciplinary approach allows for the consideration of which areas the research topic has the greatest influence on and is generating the most interest for study. In carrying out systematic literature mappings, identifying the disciplinary areas that have a greater presence is highly useful because it serves as a basis for determining which area or areas can be focussed on for future systematic literature reviews.

RQ2 What are the dominant trends and methodological tools observed in the research skill articles?

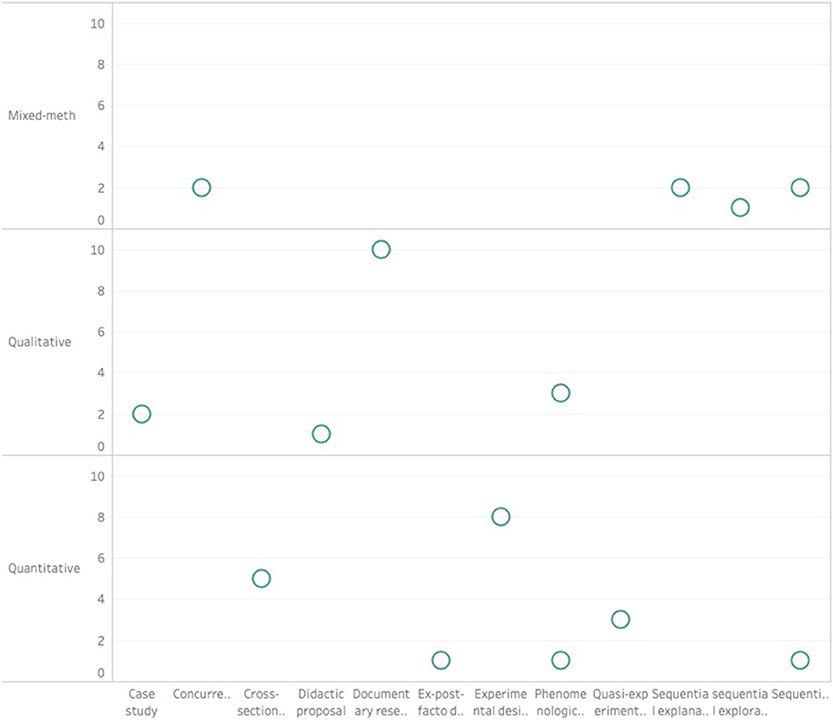

The study addressed the different research methods: quantitative, qualitative and mixed method. The classification used is shown in Figure 3 and allows identifying that in the experimental design the quantitative method predominated (4, 5, 10, 14, 21, 27, 30, 31), on the other hand in the documentary research there was a predominance of the qualitative method (6–8, 18, 26, 36–38, 41, 42).

To have a more detailed idea of the trend of the methods used in the articles that deal with the analysis of research skills for academic literacy development, starting only from the three main methods is insufficient. Having a sub-classification that allows us to know the types of research designs that are performed in each method is a must. Presenting the specific research design allows for more detailed information, especially if the entire process followed in the research method is clearly explained.

RQ3 What are the findings in research skills for innovation in academic literacy development?

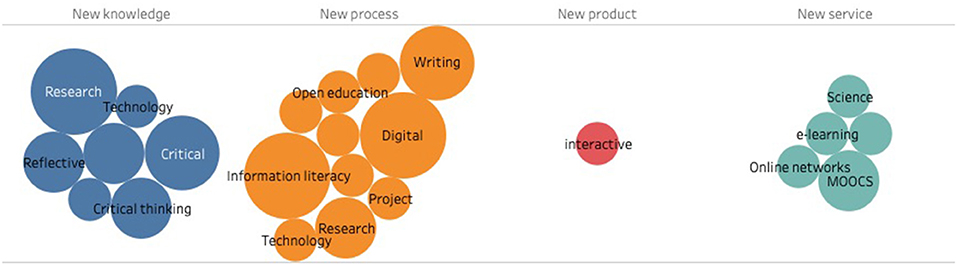

The findings focussed on four categories: (1) new knowledge (1, 3, 7, 9, 15, 20, 21, 24, 27, 29, 30, 32, 34–36) which were stated in this category when referring to transformation, impact, evolution, cognition, dissent, knowledge, talent, patent, model or system. For instance, Article 1 was considered because it talks about how students acquired knowledge about the choice of an appropriate research instrument and learned to articulate their identity as researchers, and Article 20 was considered in this category because the study investigated whether the teaching of communicative languages helps develop the critical thinking of students; (2) new process (2, 4–6, 8, 12, 14, 16, 18, 19, 22, 23, 25, 28, 37–42), the findings in this category considered an organization, a method, a strategy, a development, a procedure, a training or a technique, e.g., Article 2, were considered as the students who participated in the process of becoming good scholars by using appropriate online publications to create valid arguments by evaluating the work of others and Article 22, as this study analyses the strategies activated by a group of 36 Portuguese university students when faced with an academic writing practice in Spanish as a foreign language; (3) new product (10), findings were considered in this category when considering a technology, an article, a tool, a material, a device, an application, a manufacture, a result, an object or a prototype, e.g., Article 10 was integrated because the document illustrates the development of an online portal and a mobile application aimed at promoting student motivation and engagement; (4) new service (11, 13, 17, 26, 31, 33), the findings were stated in this category when considering elements, such as attention, provision, assistance, action, function, dependence or benefit, e.g., Article 17 that presents the Summer Science Program in México, which aims to provide university students with research competence and Article 33, as it states that online academic networks have been established as spaces for academics from all countries and as outlets for their insight and literacy. Below are the key words that appeared most often in each category in Figure 4 .

Innovation is present in the findings found in the articles through the idea that it starts from something existing to generate something new, gives a new meaning and a new idea through elements, such as those considered in the classification used in this systematic review of literature. Innovative elements do not necessarily have to contemplate technology, innovating can consist of providing new solutions that respond to specific needs, which can be useful not only in economic and social scenarios but also in the educational context.

RQ4 What types of innovations related to the development of academic reading and writing emerge from the studies consulted?

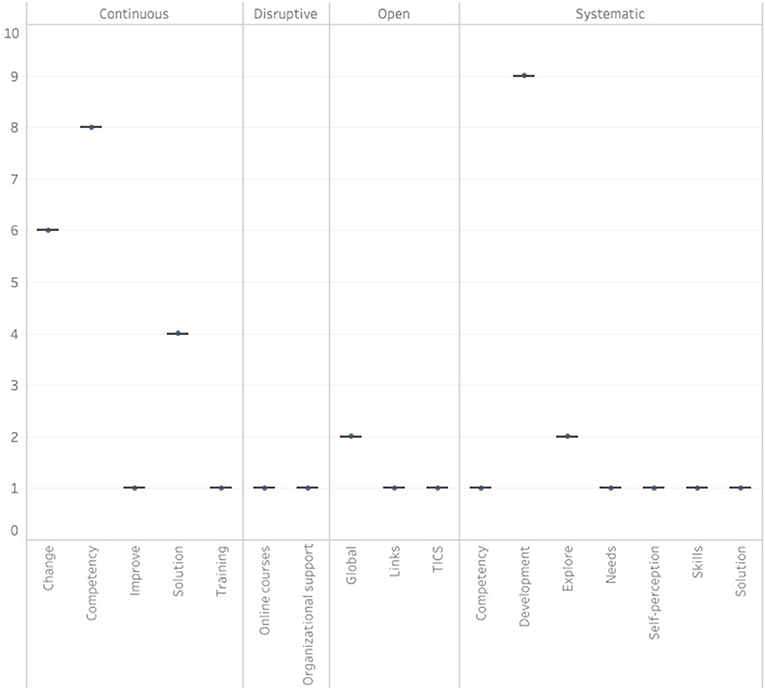

The categories on which the classification of the types of innovation focussed were the following: continuous, systematic, disruptive and open. In continuous innovation, the keywords change, competency, improve, solution and training were placed. In systematic innovation, the keywords were competency, development, explore, needs, self-perception, skills, and solution. In disruptive innovation, the keywords were online courses and organizational support. In open innovation, the keywords global, links and ICTS were located. In the systematic category, more articles were about development (2, 5–7, 11, 13, 14, 16, 21–23, 27, 28, 32, 35, 42), as shown in Figure 5 .

The distinct types of innovation allow us to know at what level an innovation is being conducted to know how much emphasis is given to the part of generating innovation within research if it is considered something that occurs gradually or if, on the contrary, it is considered that it requires drastic changes that can be generated even immediately. Moreover, nowadays, open innovation has become increasingly important, especially in the field of higher education where knowledge repositories are now considered open spaces.

RQ5 What are the recommendations that the authors give for future studies on research skills and for the processes of academic reading and writing?

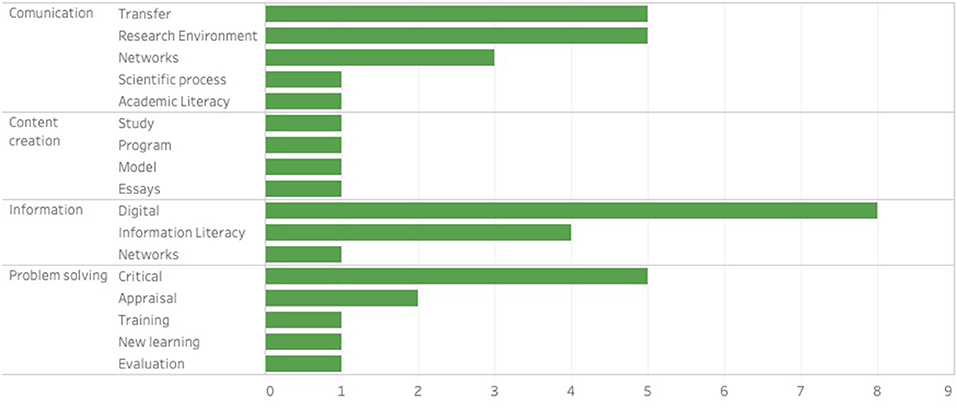

The study first identified the recommendations that the authors made for future studies in the framework of research skills and academic literacy processes. Subsequently, the categories presented in Figure 6 were established. The item that had the most presence around the category of Information was the digital element because it was considered in some studies that learning had a positive effect through the use of digital resources (6, 11, 13, 15, 29, 31, 41, 42).

Today, in the digital economy, the role of knowledge production in information systems is increasing dramatically. The same is true in the field of education; therefore, making appropriate use of these digital resources in accordance with the stated research purposes is necessary. The digital era is complex and requires flexible education that enhances new skills, and higher education students must be trained to efficiently use the wide diversity of digital resources now available to them and to perform well in virtual environments.

RQ6 What are the research challenges for the research skills and academic reading and writing processes?

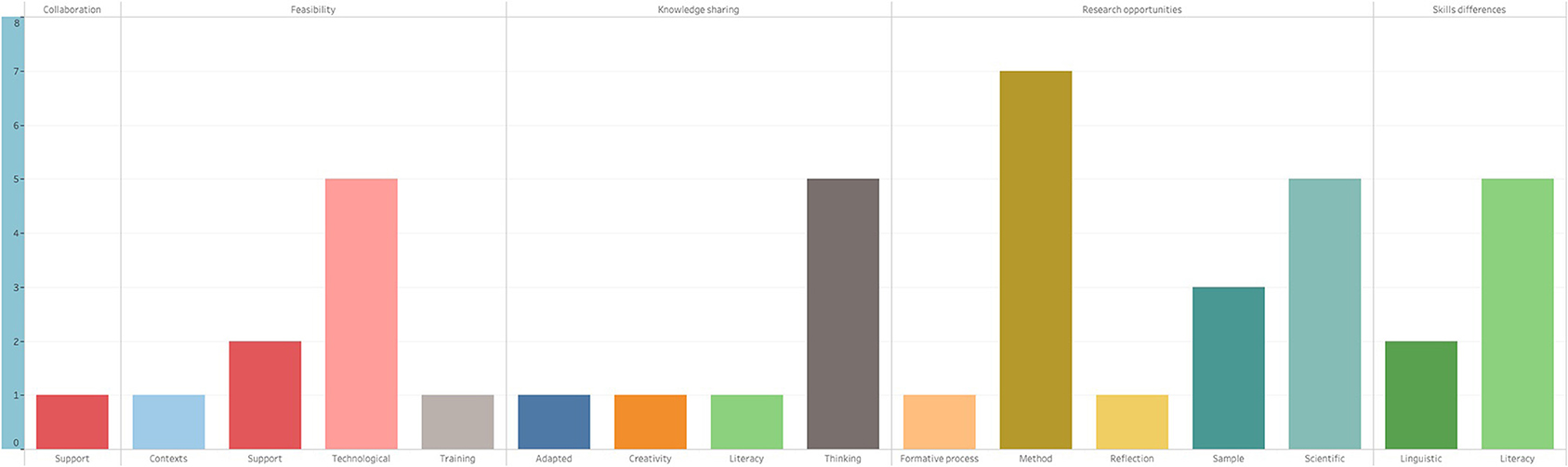

The challenges were analyzed, and the following were located: collaboration (support), feasibility (contexts, technological, training, and support), knowledge sharing (literacy, thinking, creativity and adapted), research opportunities (reflection, scientific, method, sample, formative process, and skills) and differences (literacy and linguistic). Amongst the challenges shown in the studies that were addressed in this study, those related to research opportunities (1, 4–6, 9, 11–14, 16, 17, 19, 30, 33, 34, 36, 39) stand out, followed by learning sharing (2, 8, 18, 20, 26, 27, 31, 42) and viability (7, 10, 15, 25, 29, 32, 38, 40, 41), as can be seen in Figure 7 .

The challenges in research allow us to identify on which topics the researcher should concentrate to be able to give solutions to problems posed around a research topic because knowing which obstacles have been presented in a specific research process is interesting so that they can serve as a basis for further studies. The challenges presented in research can be of various kinds, from questions such as the financial support required according to the type and time of research to the viability related to aspects such as the necessary skills or the mastery of the use of technology to make research feasible.

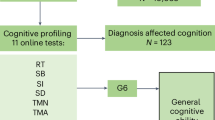

Amongst the theoretical–conceptual trends, the one corresponding to Psychopedagogical Studies has turned out to be the one that has focussed more on the analysis of research skills for the development of academic writing. Figure 1 depicts that there was a greater trend of articles in psychopedagogical matters and that they were distributed in various disciplinary areas. Psychopedagogical studies focus on cognitive elements and on social–emotional elements and improvements in academic achievement ( Ramírez-Montoya and Valenzuela, 2019 ). In this review, the psychopedagogical approach is framed mainly in the application of didactic techniques, educational programmes, forms of evaluation and training and capacity building.

Figure 1 . Quality criteria for papers selection for SLR.

Experimental studies are a frequently used method in the topic of research skills. Figure 2 shows that the most commonly used research design in the articles consulted is the experimental design. However, methodological designs are available in the studies analyzed. The older categorisations of experimental designs tend to use the language of the analysis of variance to describe these arrangements ( Harwell, 2014 ). In this study, the approach of that type of design was considered because randomization was sought for the selection of the sample to be investigated. Nonetheless, various methodological designs were used in the review, and it was even decided to consider research of a documentary nature to guide the present study.

Figure 2 . Theoretical–conceptual trends in educational innovation studies.

New processes are identified with greater emphasis on the analysis of research toward the development of academic reading and writing within the framework of research competencies. Figure 3 illustrates that according to the classification addressed, the category of new processes is the one that received the most mention in the analysis. Ramírez-Montoya and Lugo-Ocando (2020) validated that a new process is characterized amongst its elements by an organization, a method, a technique, and a procedure. In this analysis, it was possible to observe that to a great extent, the findings are based on processes that imply a follow-up to determine how the evolution to reach the proposed objectives occurs.

Figure 3 . Trends and methodological tools.

Systematic and continuous innovations have a strong presence in the area of innovation in research skill studies. Figure 4 shows the trend in these types of innovation. In terms of systematic innovation, there was a greater presence of the development aspect, whilst continuous innovation had a greater presence of the competence aspect. Continuous innovation is something that has to do with small changes that can make a difference, and systematic innovation is methodical and orderly like continuous improvement innovation. However, the scope and novelty of its changes can vary and even lead to substantial changes ( Valenzuela and Valencia, 2017 ). The innovations must be based on the objectives to be achieved and always with a view to achieving substantial improvement.

Figure 4 . Findings in research skills for academic literacy development.

Digital resources and skills present a valuable opportunity to enhance academic literacy development through research skills. Figure 5 shows that the digital aspect had a greater presence in the area of Information that was presented for the categorization of Recommendations for Future Studies. The digital competencies according to Ferrari (2013) are focussed on Information, Communication, Content Creation, Problem Solving and Security, but the latter was not present in the studies analyzed. Interacting through digital tools or in digital environments is a reality we are currently facing; therefore, students must be prepared to have digital competences, which allow them to have a better performance in general and enrich the framework in which they develop their academic reading and writing.

Figure 5 . Types of innovations related to the development of academic reading and writing.

Challenges in research skill studies show various themes, such as collaboration, sharing of learning, difference in skills or feasibility, and no single line is to be addressed. The categories corresponding to the challenges that have the greatest presence according to Figure 6 are the following: research opportunities and knowledge sharing. However, there is variety in the keywords that are derived from these. However, critical thinking and literacy (academic and information) are considered relevant by the subject matter. IL has important advantages for the proper selection and use of information ( Association of College Research Libraries, 2016 ), and academic literacy is now closely linked to the competencies for evaluating digital content and producing knowledge ( Solimine and Garcia-Quismondo, 2020 ). What is important is the acquisition of skills so that students in higher education can be effective in research and can adequately develop the process of academic reading and writing.

Figure 6 . Recommendations for future studies on research skills and processes of academic reading and writing.

Figure 7 . Research challenges for the research skills and academic reading and writing processes.

Limitations

Only the Web of Science and Scopus databases were used for the selection of articles for analysis in this systematic literature review. Although they are amongst the most important, other articles that could be relevant to the topic addressed in this study were left out. By including only studies that had higher education institutions as their context, we excluded studies conducted in extra-school contexts that could be significant. The three quality criteria that were used reduced the selection to 42 articles, which may be a small number, but they are the articles that are related to the specific objective of the research, which is to identify research skills that allow for the development of academic reading and writing.

Conclusions

Research competencies can work for several disciplines. In this systematic review of literature, the articles analyzed correspond to the disciplinary areas of Education; Language and Literature; Medicine; Library Science; Philosophy, Psychology and religion and Science, which implies that there is a multidisciplinary character to address the issues of research competencies and the development of academic literacy. Nevertheless, the discipline with the greatest presence is education, which allows us to identify that there is an increasing concern to promote the culture of research in this area, as well as to seek that students acquire the skills necessary for the better development of academic literacy.

Academic literacy is indeed a fundamental part of the higher education environment. The types of innovation to develop academic literacy that have the greatest presence are systematic and continuous innovation, the aspect that stands out from the first is development, and from the second are competition and change. Competencies are thus identified as a key element to be considered to achieve the development of academic literacy.

Research competencies for the development of academic reading and writing imply not only taking care of methodological aspects. It is not enough to take care of elements such as the formulation of the research question, the selection of the research method and design, the selection of instruments and the evaluation system. Crucial competencies, such as academic and information literacy (IL), must be considered because in this information society, which is not necessarily a knowledge society, one must be literate to be able to use information for the proposed purposes and to develop quality academic texts that can subsequently disseminate and support the expansion of knowledge in the various areas of higher education.

The aim of this research is to identify studies that address research competencies and those that address academic literacy through innovative elements, so that it can be determined how these three elements can be linked to each other to benefit university students in the sense of serving as a basis for generating initiatives to promote research competencies that can be used to develop academic literacy in higher education contexts through innovative models. It is intended that with the development of these competencies, university students can develop research skills, search for information efficiently in different environments and platforms, understand specialized texts in their area of study, and finally generate quality writing that can be published.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

IC-M carried out the systematic review of literature, carried out the analysis of the articles considered to be integrated in the present study, investigated and integrated the theoretical part, made the graphs and tables, wrote the article, and took care of form and content. MR-M reviewed in detail the form and content of the article, suggested authors for theoretical support, checked that the paragraphs had an adequate structure, and that the references were current, consistent, and correctly cited. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The study was conducted within the framework of the doctoral studies corresponding to the Ph.D. programme in Educational Innovation. Special thanks are due to the scholarships granted by CONACYT and Tecnologico de Monterrey. The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of Writing Lab, TecLabs, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico, in the production of this work.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.576961/full#supplementary-material

Abu, A., and Alheet, A. (2019). The role of researcher competencies in delivering successful research. Inform. Knowledge Manag . 9, 15–19. doi: 10.7176/IKM/9-1-05

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Aguirre, C. (2016). Desarrollo de Competencias de Investigación En Estudiantes de Educación Superior Con La Mediación de Herramientas de M-Learning & E-Learning. Revista Inclusión Desarrollo 3, 68–83. doi: 10.26620/uniminuto.inclusion.4.1.2017.68-83

Altomonte, S., Logan, B., Feisst, M., Rutherford, P., and Wilson, R. (2016). Interactive and situated learning in education for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Edu. 17, 417–443. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-01-2015-0003

Álvarez, D., and Arias, V. (2016). La enseñanza abierta como estrategia para la formación en competencias investigativas en educación superior. Revista Científica 26, 117–124. doi: 10.14483/udistrital.jour.RC.2016.26.a12

Armstrong, E. J. (2019). Maximising motivators for technology-enhanced learning for further education teachers: moving beyond the early adopters in a time of austerity. Res. Learn. Technol. 27:2032. doi: 10.25304/rlt.v27.2032

Association of College and Research Libraries (2000). Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education . Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries.

Association of College and Research Libraries (2016). Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries . Available online at: http://acrl.ala.org/ilstandards/ (accessed June 16, 2020).

Barroso-Osuna, J., Gutiérrez-Castillo, J. J., Llorente-Cejudo, M., del, C., and Valencia-Ortiz, R. (2019). Difficulties in the incorporation of augmented reality in university education: visions from the experts. J. New Approaches Edu. Res. 8, 126–141. doi: 10.7821/naer.2019.7.409

Bazerman, C. H. (2014). El Descubrimiento de la Escritura Académica. En Federico Navarro (coord.). Manual de Escritura Para Carreras de Humanidades . Buenos Aires: Editorial de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Google Scholar

Belyaeva, E. (2018). Emi Moocs for University lecturers. J. Teaching Engl. Specif. Acad. Purposes 6:165. doi: 10.22190/JTESAP1801165B

Bezanilla-Albisua, M. J., Poblete-Ruiz, M., Fernández-Nogueira, D., Arranz-Turnes, S., and Campo-Carrasco, L. (2018). El pensamiento crítico desde la perspectiva de los docentes universitarios. Estudios Pedagógicos 44, 89–113. doi: 10.4067/S0718-07052018000100089

Buchberger, B., Mattivi, J. T., Schwenke, C., Katzer, C., Huppertz, H., and Wasem, J. (2018). Critical appraisal of RCTs by 3rd year undergraduates after short courses in EBM compared to expert appraisal. GMS J. Med. Edu. 35, 1–17. doi: 10.3205/zma001171

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cárdenas, M. (2018). Enfoque de problematización tecnopedagógica de la competencia investigativa mediada por tecnologías. Revista Dilemas Contemporáneos 23, 1–13. Available online at: http://www.dilemascontemporaneoseducacionpoliticayvalores.com/

Carlino, P. (2013). Alfabetización académica diez años después. Revista Mexicana de Investigacion Educativa , 18, 355–381. Available online at: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=140/14025774003

Castaño-Garrido, C., Garay-Ruiz, U., and Themistokleous, S. (2017). De la revolución del software a la del hardware en educación superior. RIED 21:135. doi: 10.5944/ried.21.1.18823

CrossRef Full Text

Chesbrough, H. (2006). “Open innovation: researching a new paradigm,” in Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology , eds H. Chesbrough, and W. P. M. Vanhaverbeke (Boston: Harvard Business School Press), 1–9.

Emelyanova, I., Teplyakova, O., and Boltunova, L. (2017). The students' research competences formation on the master's programmes in pedagogy. Eur. J. Contemp. Edu. 6, 700–714. doi: 10.13187/ejced.2017.4.700

Eybers, O. O. (2018). Friends or foes? a theoretical approach towards constructivism, realism and students' wellbeing via academic literacy practices. South Afr. J. Higher Edu. 32, 251–269. doi: 10.20853/32-6-2998

Fernández-Sánchez, M. R., Sánchez-Oro, M., and Robina-Ramírez, R. (2016). La evaluación de la competencia digital en la docencia universitaria: el caso de los grados de empresariales y económicas. Revista Colombiana Ciencias Sociales 7:332. doi: 10.21501/22161201.1726

Ferrari, A. (2013). DIGCOMP: A Framework for Developing and Understanding Digital Competence in Europe , eds Y. Punie and B. Brecko, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. doi: 10.2788/52966

Gafiyatova, E. V., and Pomortseva, N. P. (2016). The role of background knowledge in building the translating/interpreting competence of the linguist. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 9:89999. doi: 10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i16/89999

Grijalva, A. A., and Urrea Zazueta, M. L. (2017). Cultura científica desde la universidad. Evaluación de la competencia investigativa en estudiantes de verano científico. Edu. Knowledge Soc. 18:15. doi: 10.14201/eks20171831535

Grosseck, G., Malita, L., and Bran, R. (2019). Digital university—issues and trends in romanian higher education. Brain-Broad Res. Artificial Intelligence Neurosci. 10, 108–122.

Hamilton, J. (2018). Academic reading requirements for commencing HE students - are peer-reviewed journals really the right place to start? Student Success 9:73. doi: 10.5204/ssj.v9i2.408

Hana, N., and Hacène, H. (2017). Creativity in the EFL classroom: exploring teachers' knowledge and perceptions. Arab World English J. 8, 352–364. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol8no4.24

Harwell, M. (2014). “Research design in qualitative/quantitative/mixed methods,” in The SAGE Handbook for Research in Education: Pursuing Ideas as the Keystone of Exemplary Inquiry , eds C. Conrad and R. Serlin (SAGE Publications). doi: 10.4135/9781483351377

Hills, H., and Richards, T. (2013). Modeling interdisciplinary research to advance behavioral health care. J. Behav. Health Services Res. 41, 3–7. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9374-7

Hosein, A., and Rao, N. (2017). Students' reflective essays as insights into student centred-pedagogies within the undergraduate research methods curriculum. Teaching Higher Edu. 22, 109–125. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2016.1221804

Hueso-Montoro, C., Aguilar-Ferrándiz, M., Cambil-Martín, J., García-Martínez, O., Serrano-Guzmán, M., and Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. (2016). Efecto de un programa de capacitación en competencias de investigación en estudiantes de ciencias de la salud. Enfermería Global 44, 141–151. doi: 10.6018/eglobal.15.4.229361

Kitchenham, B., and Charters, S. (2007). Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in SE . Keele University and Durham University Joint Report.

Kozlov, A. V., and Shemshurina, S. A. (2018). Fostering creativity in engineering universities: research activity and curriculum policy. Int. J. Instr. 11, 93–106. doi: 10.12973/iji.2018.1147a

Kroll, J., Richardson, I., Prikladnicki, R., and Audy, J. L. N. (2018). Empirical evidence in follow the sun software development: a systematic mapping study. Inform. Softw. Technol. 93, 30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2017.08.011

Kwak, S. (2017). Approaches reflected in academic writing MOOCs. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 18, 138–155. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v18i3.2845

Kwant, K. J., Custers, E. J. F. M., Jongen-Hermus, F. J., and Kluijtmans, M. (2015). Preparation by mandatory E-modules improves learning of practical skills: a quasi-experimental comparison of skill examination results. BMC Med. Edu. 15, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0376-4

La Garza, J. R., Kowalewski, K. F., Friedrich, M., Schmidt, M. W., Bruckner, T., Kenngott, H. G., et al. (2017). Does rating the operation videos with a checklist score improve the effect of E-learning for bariatric surgical training? Study Protocol Randomized Control. Trial Trials 18, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1886-7

Lamanauskas, V. (2019). Scientific article preparation: title, abstract and keywords. Probl. Edu. 21st Century 77, 456–462. doi: 10.33225/pec/19.77.456

Li, R., Raja, R., and Sazalie, A. (2015). An investigation into Chinese EFL learners' pragmatic competence. GEMA Online J. Language Stud. 15, 101–118. doi: 10.17576/gema-2015-1502-07

Lopatovska, I., and Sessions, D. (2016). Understanding academic reading in the context of information-seeking. Library Rev. 65, 502–18. doi: 10.1108/LR-03-2016-0026

Manso, C., Cuevas, A., Martínez, E., and García-Carpintero, E. (2015). Competencias informacionales en ciencias de la salud: una propuesta formativa para estudiantes de grado en enfermería. Revista Ibero-Americana de Ciência Da Informação . Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282974412_Competencias_informacionales_en_Ciencias_de_la_Salud_una_propuesta_formativa_para_estudiantes_de_grado_en_Enfermeria (accessed June 12, 2020).

Marzal, M., and Cruz-Palacios, E. (2018). Gaming como instrumento educativo para una educación en competencias digitales desde los academic skills centres. Revista General de Informacion y Documentacion 28, 489–506. doi: 10.5209/RGID.62836

Mogonea, F., and Remus Mogonea, F. (2019). The pedagogical research project - an essential tool for the development of research competencies in the field of education. Educatia 21 17, 49–59. doi: 10.24193/ed21.2019.17.05

Natsis, A., Papadopoulos, P., and Obwegeser, N. (2018). Research integration in information systems education: students' perceptions on learnin. J. Inform. Technol. Edu. Res. 17, 345–363. doi: 10.28945/4120

Niemczyk, E. K. (2018). Developing globally competent researchers: an international perspective. South African J. Higher Edu. 32, 171–185. doi: 10.20853/32-4-1602

OECD (2017). Diagnóstico de La OCDE Sobre La Estrategia de Competencias, Destrezas y Habilidades de México . Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/mexico/Diagnostico-de-la-OCDE-sobre-la-Estrategia-de-Competencias-Destrezas-y-Habilidades-de-Mexico-Resumen-Ejecutivo.pdf

Pirela, J. (2018). Modelos educativos y perfiles de los docentes de bibliotecología y ciencia de la información en venezuela. Bibliotecas Revista de La Escuela de Bibliotecología 36:1. doi: 10.15359/rb.36-1.3

Ramírez-Montoya, M. S., and Lugo-Ocando, J. (2020). Revisión sistemática de métodos mixtos en el marco de la innovación educative. Comunicar . doi: 10.3916/C65-2020-01

Ramírez-Montoya, M. S., and Valenzuela, J. (2019). Innovación Educativa: Tendencias Globales de Investigación e Implicaciones Prácticas . 1st ed. (Barcelona: Octaedro), 9–17.

Ratnawati, R., Faridah, D., Anam, S., and Retnaningdyah, P. (2018). Exploring academic writing needs of indonesian EFL undergraduate students. Arab World English J. 9, 420–432. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol9no4.31

Rodríguez-García, A. M., Trujillo-Torres, J. M., and Sánchez-Rodríguez, J. (2019). Impact of scientific productivity on digital competence of future teachers: bibliometric approach on scopus and web of science. Revista Complutense Educacion 30, 623–646. doi: 10.5209/RCED.58862

Rubio, M. J., Torrado, M., Quirós, C., and Valls, R. (2018a). Conversations on critical thinking: can critical thinking find its way forward as the skill set and mindset of the century? Edu. Sci. 8:8040205.

Rubio, M. J., Torrado, M., Quirós, C., and Valls, R. (2018b). Autopercepción de las competencias investigativas en estudiantes de último curso de pedagogía de la universidad de barcelona para desarrollar su trabajo de fin de grado. Revista Complutense Educ. 29, 335–354. doi: 10.5209/RCED.52443

Schulz-Quach, C., Wenzel-Meyburg, U., and Fetz, K. (2018). Can elearning be used to teach palliative care? - medical students' acceptance, knowledge, and self-estimation of competence in palliative care after elearning. BMC Med. Edu. 18, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1186-2

Sellars, M., Fakirmohammad, R., Bui, L., Fishetti, J., Niyozov, S., Reynolds, R., et al. (2018). Conversations on critical thinking: can critical thinking find its way forward as the skill set and mindset of the century? Educ. Sci . 8:205. doi: 10.3390/educsci8040205

Solimine, G., and Garcia-Quismondo, M. A. Y. M. (2020). Proposal of visual literacy indicators for competencies courses. an academic literacy perspective for academic excellence. JLIS.it 11. doi: 10.4403/jlis.it-12577

Solobutina, M., and Kalatskaya, N. (2017). The experience of students using MOOC's: motivation, attitude, efficiency. Helix 8, 2424–2429. doi: 10.29042/2018-2424-2429

Straková, Z., and Cimermanová, I. (2018). Critical thinking development-a necessary step in higher education transformation towards sustainability. Sustainability 10, 1–18. doi: 10.3390/su10103366

Sukhato, K., Sumrithe, S., Wongrathanandha, C., Hathirat, S., Leelapattana, W., and Dellow, A. (2016). To be or not to be a facilitator of reflective learning for medical students? a case study of medical teachers' perceptions of introducing a reflective writing exercise to an undergraduate curriculum. BMC Med. Edu. 16, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0624-2

Trigo, E., and Núñez, X. (2018). Análisis competencial de la escritura académica en español lengua extranjera (ELE) de Estudiantes Portugueses. Aula de Encuentro 20, 116–139. doi: 10.17561/ae.v20i2.7

Trojan, F. J. (2016). Learning to mean in Spanish writing: a case study of a genre_based pedagogy for standards-based writing instruction. Foreign Language Ann. 49, 317–335. doi: 10.1111/flan.12192

Valenzuela, J., and Valencia, A. (2017). “Innovación disruptiva, innovación sistemática y procesos de mejora continua...implican distintas competencias por desarrollar? 1st ed. in Innovación Educativa. Investigación, Formación y Visibilidad , eds M-S, Ramírez-Montoya and J. Valenzuela (Madrid: Editorial Síntesis), 109–134.

Valverde, M. T. (2018). Academic writing with information and communications technology in higher education [Escritura Académica Con Tecnologías de La Información y La Comunicación En Educación Superior]. Revista Educacion a Distancia 58:14. doi: 10.6018/red/58/14

Verderame, M. F., Freedman, V. H., Kozlowski, L. M., and McCormack, W. T. (2018). Competency-based assessment for the training of PhD students and early-career scientists. ELife 7, 1–5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34801

Viera, L., Ramírez, S., and Ana Fleisner, A. (2017). El laboratorio en química orgánica: una propuesta para la promoción de competencias científico-tecnológicas. Educación Química 28, 262–68. doi: 10.1016/j.eq.2017.04.002

Vtmnescu, E. M., Andrei, A., Gazzola, P., and Dominici, G. (2018). Online academic networks as knowledge brokers: the mediating role of organizational support. Systems 6, 1–13. doi: 10.3390/systems6020011

Walton, G., and Cleland, J. (2017). Information literacy: empowerment or reproduction in practice? a discourse analysis approach. J. Document. 73, 582–594. doi: 10.1108/JD-04-2015-0048

Willson, G., and Angell, K. (2017). Mapping the association of college and research libraries information literacy framework and nursing professional standards onto an assessment rubric. J. Med. Library Assoc. 105, 150–154. doi: 10.5195/JMLA.2017.39

Winch, J. (2019). Does communicative language teaching help develop students' competence in thinking critically? J. Language Edu. 5, 112–122. doi: 10.17323/jle.2019.8486

Zetina, C., Magaña, D., and Avendaño, K. (2017). Enseñanza de las competencias de investigación: un reto en la gestión educativa. Atenas Revista Científico Pedagógica 1, 1–14.

Keywords: educational innovation, higher education, research competencies, academic reading and writing, systematic literature review, research skills

Citation: Castillo-Martínez IM and Ramírez-Montoya MS (2021) Research Competencies to Develop Academic Reading and Writing: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Educ. 5:576961. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.576961

Received: 27 June 2020; Accepted: 14 December 2020; Published: 18 January 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Castillo-Martínez and Ramírez-Montoya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Isolda Margarita Castillo-Martínez, isoldamcm@hotmail.com

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.2 Developing Study Skills

Learning objectives.

- Use strategies for managing time effectively as a college student.

- Understand and apply strategies for taking notes efficiently.

- Determine the specific time-management, study, and note-taking strategies that work best for you individually.

By now, you have a general idea of what to expect from your college courses. You have probably received course syllabi, started on your first few assignments, and begun applying the strategies you learned about in Section 1.1 “Reading and Writing in College” .

At the beginning of the semester, your work load is relatively light. This is the perfect time to brush up on your study skills and establish good habits. When the demands on your time and energy become more intense, you will have a system in place for handling them.

This section covers specific strategies for managing your time effectively. You will also learn about different note-taking systems that you can use to organize and record information efficiently.

As you work through this section, remember that every student is different. The strategies presented here are tried and true techniques that work well for many people. However, you may need to adapt them slightly to develop a system that works well for you personally. If your friend swears by her smartphone, but you hate having to carry extra electronic gadgets around, then using a smartphone will not be the best organizational strategy for you.

Read with an open mind, and consider what techniques have been effective (or ineffective) for you in the past. Which habits from your high school years or your work life could help you succeed in college? Which habits might get in your way? What changes might you need to make?

Understanding Yourself as a Learner

To succeed in college—or any situation where you must master new concepts and skills—it helps to know what makes you tick. For decades, educational researchers and organizational psychologists have examined how people take in and assimilate new information, how some people learn differently than others, and what conditions make students and workers most productive. Here are just a few questions to think about:

- What is your learning style? For the purposes of this chapter, learning style refers to the way you prefer to take in new information, by seeing, by listening, or through some other channel. For more information, see the section on learning styles.

- What times of day are you most productive? If your energy peaks early, you might benefit from blocking out early morning time for studying or writing. If you are a night owl, set aside a few evenings a week for schoolwork.

- How much clutter can you handle in your work space? Some people work fine at a messy desk and know exactly where to find what they need in their stack of papers; however, most people benefit from maintaining a neat, organized space.

- How well do you juggle potential distractions in your environment? If you can study at home without being tempted to turn on the television, check your e-mail, fix yourself a snack, and so on, you may make home your work space. However, if you need a less distracting environment to stay focused, you may be able to find one on your college’s campus or in your community.

- Does a little background noise help or hinder your productivity? Some people work better when listening to background music or the low hum of conversation in a coffee shop. Others need total silence.

- When you work with a partner or group, do you stay on task? A study partner or group can sometimes be invaluable. However, working this way takes extra planning and effort, so be sure to use the time productively. If you find that group study sessions turn into social occasions, you may study better on your own.

- How do you manage stress? Accept that at certain points in the semester, you will feel stressed out. In your day-to-day routine, make time for activities that help you reduce stress, such as exercising, spending time with friends, or just scheduling downtime to relax.

Learning Styles

Most people have one channel that works best for them when it comes to taking in new information. Knowing yours can help you develop strategies for studying, time management, and note taking that work especially well for you.

To begin identifying your learning style, think about how you would go about the process of assembling a piece of furniture. Which of these options sounds most like you?

- You would carefully look over the diagrams in the assembly manual first so you could picture each step in the process.

- You would silently read the directions through, step by step, and then look at the diagrams afterward.

- You would read the directions aloud under your breath. Having someone explain the steps to you would also help.

- You would start putting the pieces together and figure out the process through trial and error, consulting the directions as you worked.

Now read the following explanations. Again, think about whether each description sounds like you.

- If you chose (a), you may be a visual learner . You understand ideas best when they are presented in a visual format, such as a flowchart, a diagram, or text with clear headings and many photos or illustrations.

- If you chose (b), you may be a verbal learner . You understand ideas best through reading and writing about them and taking detailed notes.

- If you chose (c), you may be an auditory learner . You understand ideas best through listening. You learn well from spoken lectures or books on tape.

- If you chose (d), you may be a kinesthetic learner . You learn best through doing and prefer hands-on activities. In long lectures, fidgeting may help you focus.

Your learning style does not completely define you as a student. Auditory learners can comprehend a flow chart, and kinesthetic learners can sit still long enough to read a book. However, if you do have one dominant learning style, you can work with it to get the most out of your classes and study time. Table 1.3 “Learning Style Strategies” lists some tips for maximizing your learning style.

Table 1.3 Learning Style Strategies

The material presented here about learning styles is just the tip of the iceberg. There are numerous other variations in how people learn. Some people like to act on information right away while others reflect on it first. Some people excel at mastering details and understanding concrete, tried and true ideas while others enjoy exploring abstract theories and innovative, even impractical ideas. For more information about how you learn, visit your school’s academic resource center.

Time Management

In college you have increased freedom to structure your time as you please. With that freedom comes increased responsibility. High school teachers often take it upon themselves to track down students who miss class or forget assignments. College instructors, however, expect you to take full responsibility for managing yourself and getting your work done on time.

Getting Started: Short- and Long-Term Planning

At the beginning of the semester, establish a weekly routine for when you will study and write. A general guideline is that for every hour spent in class, students should expect to spend another two to three hours on reading, writing, and studying for tests. Therefore, if you are taking a biology course that meets three times a week for an hour at a time, you can expect to spend six to nine hours per week on it outside of class. You will need to budget time for each class just like an employer schedules shifts at work, and you must make that study time a priority.

That may sound like a lot when taking multiple classes, but if you plan your time carefully, it is manageable. A typical full-time schedule of fifteen credit hours translates into thirty to forty-five hours per week spent on schoolwork outside of class. All in all, a full-time student would spend about as much time on school each week as an employee spends on work. Balancing school and a job can be more challenging, but still doable.

In addition to setting aside regular work periods, you will need to plan ahead to handle more intense demands, such as studying for exams and writing major papers. At the beginning of the semester, go through your course syllabi and mark all major due dates and exam dates on a calendar. Use a format that you check regularly, such as your smartphone or the calendar feature in your e-mail. (In Section 1.3 “Becoming a Successful College Writer” you will learn strategies for planning out major writing assignments so you can complete them on time.)

The two- to three-hour rule may sound intimidating. However, keep in mind that this is only a rule of thumb. Realistically, some courses will be more challenging than others, and the demands will ebb and flow throughout the semester. You may have trouble-free weeks and stressful weeks. When you schedule your classes, try to balance introductory-level classes with more advanced classes so that your work load stays manageable.

Crystal knew that to balance a job, college classes, and a family, it was crucial for her to get organized. For the month of September, she drew up a week-by-week calendar that listed not only her own class and work schedules but also the days her son attended preschool and the days her husband had off from work. She and her husband discussed how to share their day-to-day household responsibilities so she would be able to get her schoolwork done. Crystal also made a note to talk to her supervisor at work about reducing her hours during finals week in December.

Now that you have learned some time-management basics, it is time to apply those skills. For this exercise, you will develop a weekly schedule and a semester calendar.

- Working with your class schedule, map out a week-long schedule of study time. Try to apply the “two- to three-hour” rule. Be sure to include any other nonnegotiable responsibilities, such as a job or child care duties.

- Use your course syllabi to record exam dates and due dates for major assignments in a calendar (paper or electronic). Use a star, highlighting, or other special marking to set off any days or weeks that look especially demanding.

Staying Consistent: Time Management Dos and Don’ts

Setting up a schedule is easy. Sticking with it, however, may create challenges. A schedule that looked great on paper may prove to be unrealistic. Sometimes, despite students’ best intentions, they end up procrastinating or pulling all-nighters to finish a paper or study for an exam.

Keep in mind, however, that your weekly schedule and semester calendar are time-management tools. Like any tools, their effectiveness depends on the user: you. If you leave a tool sitting in the box unused (e.g., if you set up your schedule and then forget about it), it will not help you complete the task. And if, for some reason, a particular tool or strategy is not getting the job done, you need to figure out why and maybe try using something else.

With that in mind, read the list of time-management dos and don’ts. Keep this list handy as a reference you can use throughout the semester to “troubleshoot” if you feel like your schoolwork is getting off track.

- Set aside time to review your schedule or calendar regularly and update or adjust them as needed.

- Be realistic when you schedule study time. Do not plan to write your paper on Friday night when everyone else is out socializing. When Friday comes, you might end up abandoning your plans and hanging out with your friends instead.

- Be honest with yourself about where your time goes. Do not fritter away your study time on distractions like e-mail and social networking sites.

- Accept that occasionally your work may get a little off track. No one is perfect.

- Accept that sometimes you may not have time for all the fun things you would like to do.

- Recognize times when you feel overextended. Sometimes you may just need to get through an especially demanding week. However, if you feel exhausted and overworked all the time, you may need to scale back on some of your commitments.

- Have a plan for handling high-stress periods, such as final exam week. Try to reduce your other commitments during those periods—for instance, by scheduling time off from your job. Build in some time for relaxing activities, too.

- Do not procrastinate on challenging assignments. Instead, break them into smaller, manageable tasks that can be accomplished one at a time.

- Do not fall into the trap of “all-or-nothing” thinking: “There is no way I can fit in a three-hour study session today, so I will just wait until the weekend.” Extended periods of free time are hard to come by, so find ways to use small blocks of time productively. For instance, if you have a free half hour between classes, use it to preview a chapter or brainstorm ideas for an essay.

- Do not fall into the trap of letting things slide and promising yourself, “I will do better next week.” When next week comes, the accumulated undone tasks will seem even more intimidating, and you will find it harder to get them done.

- Do not rely on caffeine and sugar to compensate for lack of sleep. These stimulants may temporarily perk you up, but your brain functions best when you are rested.

The key to managing your time effectively is consistency. Completing the following tasks will help you stay on track throughout the semester.

- Establish regular times to “check in” with yourself to identify and prioritize tasks and plan how to accomplish them. Many people find it is best to set aside a few minutes for this each day and to take some time to plan at the beginning of each week.

- For the next two weeks, focus on consistently using whatever time-management system you have set up. Check in with yourself daily and weekly, stick to your schedule, and take note of anything that interferes. At the end of the two weeks, review your schedule and determine whether you need to adjust it.

- Review the preceeding list of dos and don’ts.

Writing at Work

If you are part of the workforce, you have probably established strategies for accomplishing job-related tasks efficiently. How could you adapt these strategies to help you be a successful student? For instance, you might sync up your school and work schedules on an electronic calendar. Instead of checking in with your boss about upcoming work deadlines, establish a buddy system where you check in with a friend about school projects. Give school the same priority you give to work.

Note-Taking Methods

One final valuable tool to have in your arsenal as a student is a good note-taking system. Just the act of converting a spoken lecture to notes helps you organize and retain information, and of course, good notes also help you review important concepts later. Although taking good notes is an essential study skill, many students enter college without having received much guidance about note taking.

These sections discuss different strategies you can use to take notes efficiently. No matter which system you choose, keep the note-taking guidelines in mind.

General Note-Taking Guidelines

- Before class, quickly review your notes from the previous class and the assigned reading. Fixing key terms and concepts in your mind will help you stay focused and pick out the important points during the lecture.

- Come prepared with paper, pens, highlighters, textbooks, and any important handouts.

- Come to class with a positive attitude and a readiness to learn. During class, make a point of concentrating. Ask questions if you need to. Be an active participant.

- During class, capture important ideas as concisely as you can. Use words or phrases instead of full sentences and abbreviate when possible.

- Visually organize your notes into main topics, subtopics, and supporting points, and show the relationships between ideas. Leave space if necessary so you can add more details under important topics or subtopics.

- Record the following:

- Review your notes regularly throughout the semester, not just before exams.

Organizing Ideas in Your Notes

A good note-taking system needs to help you differentiate among major points, related subtopics, and supporting details. It visually represents the connections between ideas. Finally, to be effective, your note-taking system must allow you to record and organize information fairly quickly. Although some students like to create detailed, formal outlines or concept maps when they read, these may not be good strategies for class notes, because spoken lectures may not allow time for elaborate notes.

Instead, focus on recording content simply and quickly to create organized, legible notes. Try one of the following techniques.

Modified Outline Format

A modified outline format uses indented spacing to show the hierarchy of ideas without including roman numerals, lettering, and so forth. Just use a dash or bullet to signify each new point unless your instructor specifically presents a numbered list of items.

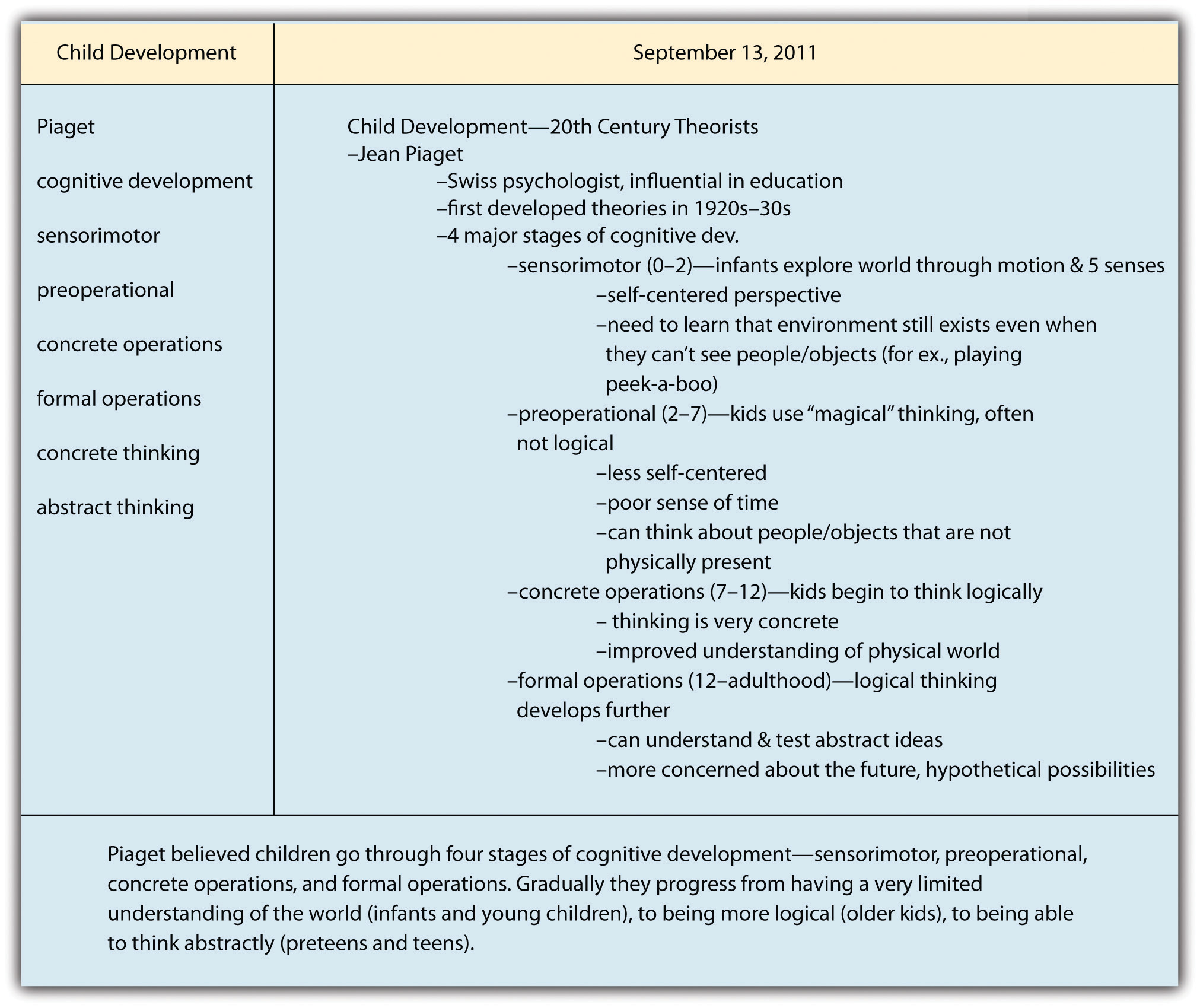

The first example shows Crystal’s notes from a developmental psychology class about an important theorist in this field. Notice how the line for the main topic is all the way to the left. Subtopics are indented, and supporting details are indented one level further. Crystal also used abbreviations for terms like development and example .

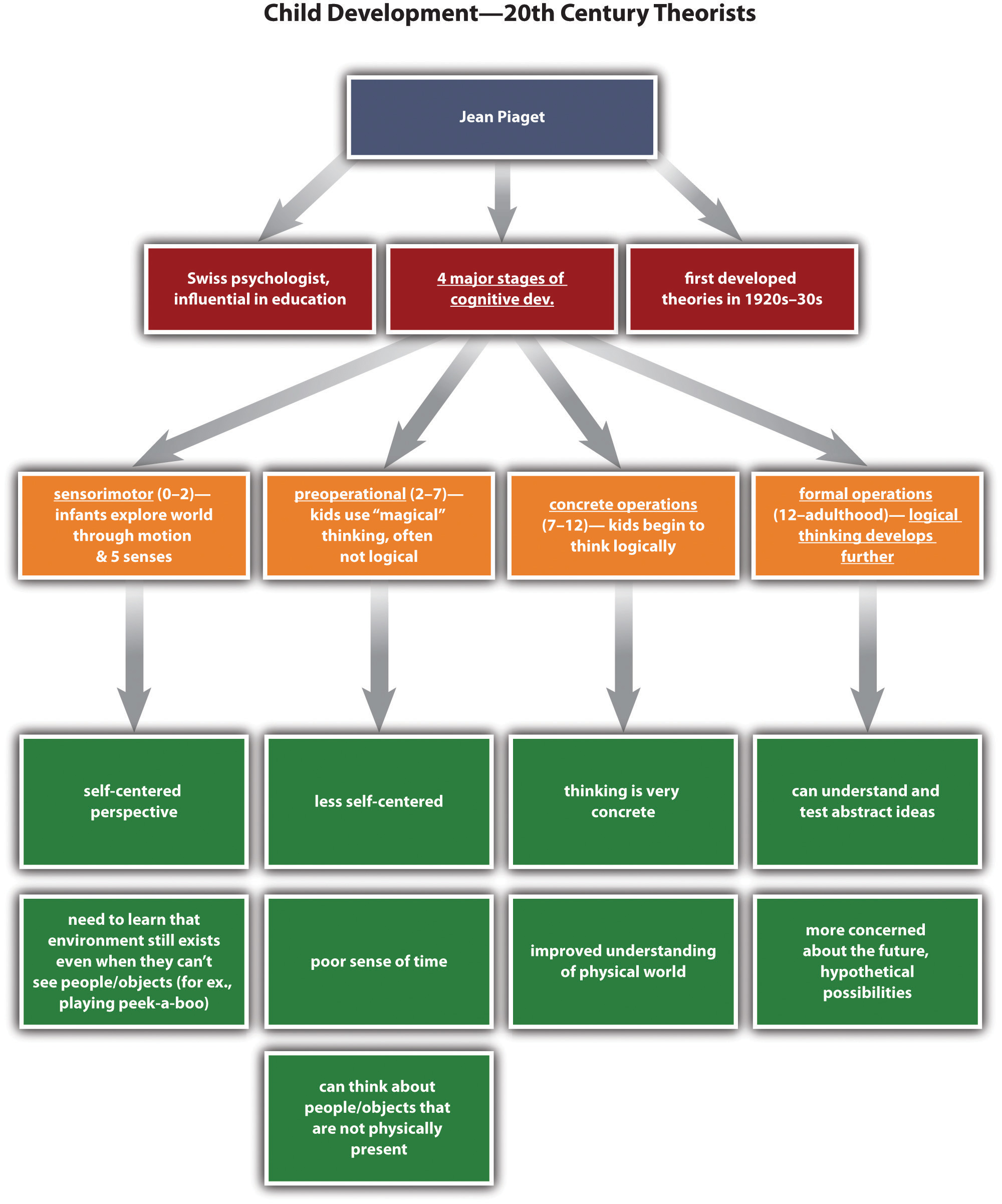

Idea Mapping

If you discovered in this section that you learn best with visual presentations, you may prefer to use a more graphic format for notes, such as an idea map. The next example shows how Crystal’s lecture notes could be set up differently. Although the format is different, the content and organization are the same.

If the content of a lecture falls into a predictable, well-organized pattern, you might choose to use a chart or table to record your notes. This system works best when you already know, either before class or at the beginning of class, which categories you should include. The next figure shows how this system might be used.

The Cornell Note-Taking System

In addition to the general techniques already described, you might find it useful to practice a specific strategy known as the Cornell note-taking system. This popular format makes it easy not only to organize information clearly but also to note key terms and summarize content.

To use the Cornell system, begin by setting up the page with these components:

- The course name and lecture date at the top of the page

- A narrow column (about two inches) at the left side of the page

- A wide column (about five to six inches) on the right side of the page

- A space of a few lines marked off at the bottom of the page

During the lecture, you record notes in the wide column. You can do so using the traditional modified outline format or a more visual format if you prefer.

Then, as soon as possible after the lecture, review your notes and identify key terms. Jot these down in the narrow left-hand column. You can use this column as a study aid by covering the notes on the right-hand side, reviewing the key terms, and trying to recall as much as you can about them so that you can mentally restate the main points of the lecture. Uncover the notes on the right to check your understanding. Finally, use the space at the bottom of the page to summarize each page of notes in a few sentences.

Using the Cornell system, Crystal’s notes would look like the following:

Often, at school or in the workplace, a speaker will provide you with pregenerated notes summarizing electronic presentation slides. You may be tempted not to take notes at all because much of the content is already summarized for you. However, it is a good idea to jot down at least a few notes. Doing so keeps you focused during the presentation, allows you to record details you might otherwise forget, and gives you the opportunity to jot down questions or reflections to personalize the content.

Over the next few weeks, establish a note-taking system that works for you.

- If you are not already doing so, try using one of the aforementioned techniques. (Remember that the Cornell system can be combined with other note-taking formats.)

- It can take some trial and error to find a note-taking system that works for you. If you find that you are struggling to keep up with lectures, consider whether you need to switch to a different format or be more careful about distinguishing key concepts from unimportant details.

- If you find that you are having trouble taking notes effectively, set up an appointment with your school’s academic resource center.

Key Takeaways

- Understanding your individual learning style and preferences can help you identify the study and time-management strategies that will work best for you.

- To manage your time effectively, it is important to look at the short term (daily and weekly schedules) and the long term (major semester deadlines).

- To manage your time effectively, be consistent about maintaining your schedule. If your schedule is not working for you, make adjustments.

- A good note-taking system must differentiate among major points, related subtopics, and supporting details, and it must allow you to record and organize information fairly quickly. Choose the format that is most effective for you.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Lippincott Open Access

How to study effectively

Alexander fowler.

a Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

Katharine Whitehurst

b Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital

Yasser Al Omran

c East Anglia NHS Deanery

Shivanchan Rajmohan

d Imperial College London

Yagazie Udeaja

e UCL Medical School, University College London

Kiron Koshy

f Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals

Buket Gundogan

g University College London Medical School, UK

The ability to study effectively is an essential part of completing a medical degree. To cope with the vast amount of information and skills needed to be acquired, it is necessary develop effective study techniques. In this article we outline the various methods students can use to excel in upcoming examinations.

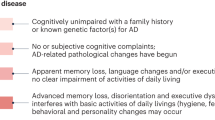

The ability to study effectively is essential in a medical degree. Firstly, having an effective way of learning is key to completing medical school, to cope with the vast volume of information taught. Secondly, medicine and surgery are careers that require constant learning; best practice is ever changing and it is important to be able to integrate these changes into your clinical practice. Thirdly, setting up efficient learning techniques while at medical school will be beneficial to you as and when you approach membership examinations, where study must be fitted around clinical commitments.

Studying effectively depends upon 2 factors: the content you intend to study and how you learn. Learning styles classically fall into 4 groups according to the VARK model (Visual, Aural, Read/Write, and Kinesthetic) but medical students seem to be multimodal in their learning style 1 . This implies that different learning techniques typically ascribed to certain learning styles may be beneficial to students of other learning styles and thus attempting to determine your unique learning style may help to consolidate your methods of study.

Broadly, study is divided into “Book Work” and “Practical Work.” As a medical student, this translates to “Written Papers” and “Clinical Exams,” respectively, although there is often significant overlap. Irrespective of what is to be studied, a plan must be considered first. A solid plan and revision timetable are critical to success upon examination. First, find the date of your examination/s, then work back to deduce how long you have to prepare. At this time, you must also consider the format of the examination, either by reading supplementary material offered by the medical school or by asking for first-hand accounts from students in the years above you who have experienced the examination and can provide extra tips and information. These quick tasks ensure that your preparation and prospective study is well suited to the examination you will do.

Some like to dedicate specific days of the week to certain topics and others, different times in a day and this will vary from person to person. It is possibly best to implement a mixture of the 2, where there is an initial block session to establish the basics, followed by a number of consolidation periods over time to go over and reinforce your learning 2 . For big topics, it is often easier and more time efficient to try and establish a pattern of learning that involves regular, small periods of work. Switching between topics when studying may also aid in effective learning 2 .