Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Nutrition articles from across Nature Portfolio

Nutrition is the organic process of nourishing or being nourished, including the processes by which an organism assimilates food and uses it for growth and maintenance.

Latest Research and Reviews

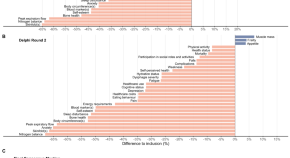

Critical outcomes to be included in the Core Outcome Set for nutritional intervention studies in older adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition: a modified Delphi Study

- Nuno Mendonça

- Christina Avgerinou

- Marjolein Visser

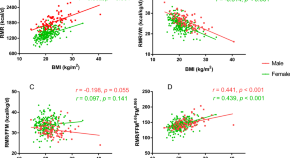

Multiple factor assessment for determining resting metabolic rate in young adults

- Wanqing Zhou

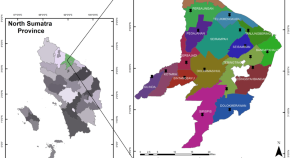

Monitoring and evaluation of childhood stunting reduction program based on fish supplement product in North Sumatera, Indonesia

- Bens Pardamean

- Rudi Nirwantono

- Sarma Nursani Lumbanraja

The influence of obesity, diabetes mellitus and smoking on fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD)

- S. B. Zwingelberg

- B. Lautwein

- B. O. Bachmann

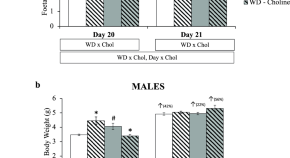

Maternal choline supplementation mitigates premature foetal weight gain induced by an obesogenic diet, potentially linked to increased amniotic fluid leptin levels in rats

- Zhi Xin Yau-Qiu

- Sebastià Galmés

- Ana María Rodríguez

Taurine reduces the risk for metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

- Chih-Chen Tzang

- Liang-Yun Chi

- Levent Özçakar

News and Comment

Hunger on campus: why US PhD students are fighting over food

Graduate students are relying on donated and discounted food in the struggle to make ends meet.

- Laurie Udesky

Personalized nutrition as the catalyst for building food-resilient cities

Data-driven personalized nutrition (PN) can address the complexities of food systems in megacities, aiming to enhance food resilience. By integrating individual preferences, health data and environmental factors, PN can optimize food supply chains, promote healthier dietary choices and reduce food waste. Collaborative efforts among stakeholders are essential to implement PN effectively.

- Anna Ziolkovska

- Christian Sina

Seafood access in Kiribati

- Annisa Chand

Metabolic product of excess niacin is linked to increased risk of cardiovascular events

A metabolic product of excess niacin promotes vascular inflammation in preclinical models and is associated with increased rates of major adverse cardiovascular events in humans.

- Gregory B. Lim

Introducing meat–rice: grain with added muscles beefs up protein

The laboratory-grown food uses rice as a scaffold for cultured meat.

- Jude Coleman

‘Blue foods’ to tackle hidden hunger and improve nutrition

Aquatic foods have been overlooked in moves to end food insecurity. That needs to change, says Christopher Golden.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Looking to the future: Agendas, directions, and resources for nutrition research

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

- 2 Translational and Clinical Research Centers, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

- 3 Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, USA.

- 4 Institute for Translational Medicine Clinical Research Center, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

- PMID: 38667339

- DOI: 10.1002/ncp.11154

The development and progression of nutrition as a scientific field is ever evolving and complex. Although the history of nutrition research began by exploring specific food components, it has evolved to encompass a more holistic view that considers the impact of dietary patterns over time, interactions with the environment, nutrition's role in disease processes, and public policy related to nutrition health. To guide the future direction of nutrition science, both federal and other professional organizations have established agendas and goals. The Strategic Plan for National Institutes of Health Nutrition Research outlines four goals and five cross-cutting research areas that are priorities to explore between 2020 and 2030. Similarly, the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition and other governmental and professional organizations have identified priority areas in their research agendas. Rigorous research studies are needed to explore these areas of interest while also considering practical implementation strategies for translating research into practice. Nutrition clinicians are uniquely positioned to lend expertise in the areas of research design, implementation, advocacy and evidence-based practice; there are numerous resources to support practitioners in these endeavors.

Keywords: federal nutrition research; nutrition policy; nutrition research; precision nutrition; translational science.

© 2024 The Authors. Nutrition in Clinical Practice published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.

Publication types

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplement Archive

- Article Collection Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Call for Papers

- Why Publish?

- About Nutrition Reviews

- About International Life Sciences Institute

- Editorial Board

- Early Career Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, conclusions, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Trends, challenges, opportunities, and future needs of the dietetic workforce: a systematic scoping review

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Merran Blair, Lana Mitchell, Claire Palermo, Simone Gibson, Trends, challenges, opportunities, and future needs of the dietetic workforce: a systematic scoping review, Nutrition Reviews , Volume 80, Issue 5, May 2022, Pages 1027–1040, https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab071

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Issues related to nutrition and health are prominent, yet it is unclear if the dietetics workforce is being used optimally.

Trends, challenges, opportunities, and future needs of the international dietetic workforce are investigated in this review, which was registered with Open Science Framework (10.17605/OSF.IO/DXNWE).

Eight academic and 5 grey-literature databases and the Google search engine were searched from 2010 onward according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines. Of 2050 articles screened, 184 were eligible for inclusion.

To chart data, a directed content analysis and a constant comparison technique were used.

The following 13 themes were identified: 1) emerging or expanding areas of practice; 2) skill development; 3) economic considerations; 4) nutrition informatics; 5) diversity within the workforce; 6) specific areas of practice; 7) further education; 8) intrapersonal factors; 9) perceptions of the profession; 10) protecting the scope of practice; 11) support systems; 12) employment outcomes; and 13) registration or credentialing.

The dietetics profession is aware of the need to expand into diverse areas of employment. Comprehensive workforce data are necessary to facilitate workforce planning.

A dietitian “is a professional who applies the science of food and nutrition to promote health, prevent and treat disease to optimize the health of individuals, groups, communities and populations.” 1 To use the professional title dietitian in many countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, requires a minimum of a bachelor’s degree qualification, in addition to a minimum of 500 supervised practice hours. This is in contrast to the title of nutritionist , which is less defined in many countries, with no minimum level of education; however, professional organizations suggest undergraduate degrees in nutrition science are preferred. 2 Dietitians can register with professional bodies in their country of practice, which allows them to treat individuals under various health insurance schemes and in a range of settings. In Australia, dietitians are given the title of Accredited Practicing Dietitian, in the United Kingdom, Canada, and New Zealand, the term is registered dietitian; in the United States, a qualified and registered dietitian is referred to as registered dietitian-nutritionist. For inclusivity, the term dietitian is used in this article.

Current rates of diet-related chronic disease are high, 3 and issues related to sustainable food production 4 and food security 5 , 6 are receiving more attention and requiring strategic action. Dietitians are health professionals who are well placed to address these issues 1 ; however, it is unclear if this workforce is being used optimally. Current dietetic workforce data are limited across the world and there is no objective evidence that gives a clear indication of employment rates of graduates 7 or whether the dietetics workforce is meeting population nutrition needs. 8 In the United Kingdom, approximately two thirds of dietitians work within the publicly funded National Health Service, but employment information is lacking on the one third who do not. 9 In the United States, job growth for dietetics is predicted to be higher than for other professions 10 ; however, some dietitians report leaving the profession for higher pay in alternative fields or being unable to find work. 11 In Australia, workforce supply is perceived to be greater than demand, 12 and anecdotal evidence suggests graduates struggle to find employment.

The goal of workforce development is to ensure that workforce members are able to obtain a sustainable livelihood, in addition to using the labor to achieve organizational goals that meet the needs of society. 13 , 14 Because of the changing nature of healthcare delivery 15 , 16 and consumer needs, 17 , 18 employment opportunities for dietitians are rapidly evolving. It is important that such changes be regularly assessed 19 to ensure the profession remains effective and relevant. The dietetic profession is aware of the need for planning, and comprehensive studies have been completed in both the United States 20–22 and the United Kingdom, 9 with plans underway for similar work in Australia 23 to explore the future of the dietetics profession. Work in the United Kingdom resulted in 16 recommendations for development of a dietetic workforce strategy that included increasing the visibility of the profession and preparing dietitians for more diverse roles through strategic leadership. 9 In the United States, researchers analyzed societal-change drivers and how they might affect the growth of the dietetic profession. 20 , 21 They sketched out 4 possible scenarios of the future the profession may face, depending on how it responds to these change drivers. 22 Although these projects included a systemic review 20 and an environmental scan, 9 which informed subsequent research, no systematic reviews addressing trends within the dietetic workforce have been published.

Our purpose in conducting this systematic scoping review was to investigate trends, challenges, opportunities, and future needs of the global dietetic workforce from a diverse range of literature. This information can be used to inform future workforce development strategies and to guide training priorities for the current and future international workforce. This will help ensure that members of the dietetic workforce are well placed to find employment and effectively improve the nutritional outcomes of our population.

This systematic scoping review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist 24 and with reference to the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis . 25 This review was registered with the Open Science Framework ( 10.17605/OSF.IO/DXNWE ). A scoping review was selected to be conducted in preference to synthesis approaches to capture the depth and breadth of the literature on the broad exploratory research question. 25 Grey literature was included because it has the benefit of contributing contemporary material from a broad range of stakeholders, 26 and publication delays in academic research can mean that results are indicative of past events, rather than current or future.

The following databases were searched on February 6, 2020, in in consultation with the subject specialist research librarian: Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus, Proquest Social Science Premium Collection, Scopus, and Business Source complete. Searching was also conducted in the following grey-literature databases: Open Grey, Grey Guide, MedlinePlus, Grey Literature Report, and Mednar; and thesis searching was conducted on Trove, Proquest Dissertations & Thesis Global, and Dart Europe E-Theses Portal. All searches were time restricted from January 2010 to February 2020 to capture information about the contemporary workforce from the past decade, rather than historical, outdated data. Only publications in English were included. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were predetermined on the basis of the PICOS model (ie, participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design) ( Table 1 ). Search terms ( Table 2 ) were used with appropriate variations according to the functionality of each database. All results were uploaded to Endnote X9 and then to Covidence systematic review software. 27 Title and abstract screening, followed by full-text screening, was completed in duplicate by 2 authors (M.B. and either L.M., S.G., or C.P.). Conflicts were discussed until consensus was reached.

PICOS criteria for inclusion of studies

Abbreviation: CPD, continuing professional development.

Search terms used for the scoping review exploring trends, challenges, opportunities, and future needs of the dietetic workforce

Grey-literature searching, using the search terms listed in Table 2 , was conducted using the Google search engine in February 2020. The first 10 pages of results (ie, the first 100 hits) were screened, initially via the Google search screen, then potentially relevant sites were viewed in full. 26 Reasons for exclusion were noted, and included pages were saved in PDF format for data extraction. Screening of results from the Google search was conducted by 1 researcher (M.B.). Duplicate screening was deemed unnecessary because consensus on eligibility had been reached during database screening and conflict resolution.

Data charting of included papers was completed in a spreadsheet and included year of publication, author, country where the research was conducted or the article was published, type of article, type of study, and, if applicable, research methods, population, and number of participants. In addition, a directed content analysis 28 , 29 was conducted whereby themes were deductively generated under the formative categories of 1) trends (namely, ways the workforce was developing or changing), 2) opportunities (ie, ways to achieve further development), 3) challenges (ie, obstacles to development), and 4) future needs (ie, aspects needed to strengthen the workforce) and recorded in the spreadsheet. This structure was formulated by the researchers with reference to existing research indicating that the dietetic workforce is in a state of flux and in need ofplanning. 9 , 20–22 . For the second stage in the data charting process, we used a constant comparison method 30 whereby common recurring themes were identified, within the formative categories, and these became the results of the review. Data charting was conducted by 1 researcher (M.B) with a subset of 10% (in total) charted by another researcher (either L.M., S.G., or C.P.) and cross-checked for comparison, with no major errors or omissions identified. Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence was not conducted, as is typical of scoping reviews. 24 The frequency of themes across studies was collated and a visual representation of the frequency of categories was developed on the basis of these data ( Figure 1 ).

Results of the scoping review exploring trends, challenges, opportunities, and future needs of the dietetic workforce, in descending order of commonality. Larger circles indicate the topic was referred to more often; however, this is a graphical representation only and circles are not to scale. Items listed in boxes are subcategories. Linking of circles indicates the path from most commonly to least commonly mentioned topic: emerging or expanding areas of practice (n=52); skill development (n=43); economic considerations (n=31); nutrition informatics (n=23); diversity within the workforce (n=20); specific areas of practice (n=20); additional education (n=17); intrapersonal factors (n=9); perceptions of the profession (n=9); support systems (n=5); protect the scope of practice (n=5); employment outcomes (n=3); registration and credentialing (n=3).

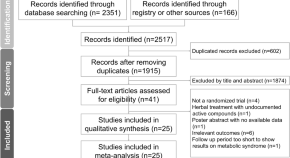

A total of 2050 articles were screened; of these, 184 were included in the scoping review ( Figure 2 ). Characteristics of the included articles are collated in Table 3 , and a comprehensive list of included articles is provided in Table S1 in the Supporting Information online. The following 13 themes were identified and are listed here in descending order of commonality: 1) emerging or expanding areas of practice; 2) skill development; 3) economic considerations; 4) nutrition informatics; 5) diversity within the workforce; 6) specific areas of practice; 7) additional education; 8) intrapersonal factors; 9) perceptions of the profession; 10) protecting the scope of practice; 11) support systems; 12) employment outcomes; and 13) registration or credentialing ( Figure 1 ). Subcategories were also identified under some themes.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of included studies in the systematic scoping review

Characteristics of articles included in the systematic scoping review

Abbreviations: JAND, Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; JADA, Journal of the American Dietetic Association.

Country where the research was conducted, or the article published.

Includes Australia and New Zealand; Australia and United Kingdom; Australia, United Kingdom, and United States; Ireland and United Kingdom; Sweden, Wales, and United States.

Includes China, Ghana, Israel, Italy, Malaysia, South Korea, Sudan.

Includes theses, abstracts, and 2 government reports.

Original research, excluding abstracts or theses.

Includes environmental scan, case study, Delphi survey, policy discourse analysis, nonrandomized controlled trial, prospective cohort.

Emerging or expanding areas of practice

A total of 51 different emerging or expanding areas of practice were identified ( Table S2 in the Supporting Information online). These were highlighted as employment opportunities to expand the scope of the profession 31 , 32 and ways in which dietitians can contribute valuable skills to benefit businesses and individuals. 31 , 33 , 34 Emerging areas were spoken of as a future need, because if dietitians did not fill these roles, they would be filled by other, potentially less qualified, individuals. 35

Skill development

A total of 21 different skills were identified (( Table S2 ) as both opportunities and future needs. Skill development was deemed to be a means by which dietitians would be able to “strengthen their ability to offer food and nutrition solutions in a wide range of situations.” 22 Clinical skills such as integrative and functional medicine 36 and nutritional genomics 37 were noted to be of increasing public interest. Skill development in these areas were suggested in order to meet the changing needs of consumers. 36 , 37 Social media skills were identified as a means to champion evidence-based nutrition information and to advocate for the profession. 38 Areas such as business skills, 22 collaboration, 39 client/customer focus, 40 computer literacy, 40 and financial management 41 were highlighted as skills desired by organizations. Sustainable food systems practices were identified as areas where dietitians can offer solutions to meet the needs of consumers and organizations. 42 It was also suggested that the profession encourage students to have dual degrees to strengthen skills in business and management. 22

Economic considerations

Four subcategories were identified relating to economic considerations: staffing ratios, supply and demand, compensation and benefits, and recruitment and retention.

Staffing ratios.

Inadequate staffing ratios were common 43–49 and described as a challenge because they may result in worse patient outcomes, 45 increased healthcare costs, 44 and increased staff turnover due to burnout. 47 In addition, dietitians were more commonly found in metropolitan areas, 49 which potentially results in lack of equitable access for individuals needing dietetic input. 48

Supply and demand.

Predictions of supply and demand varied between countries and over time. 19 , 20 , 50–53 The US Bureau of Labor Statistics predicted job growth to be “much faster than average” at 11% between 2018 and 2028. 10 Supply and demand were seen as dynamic, requiring ongoing assessment, and fundamental to workforce success. 21 , 22 , 54 An undersupply of dietitians was viewed as an opportunity for the existing workforce, resulting in higher pay rates. 19 Conversely, it was also seen as a challenge that could leave positions open for other professions, which would erode the potential economic advantage. 19 Attrition rates due to retirement were described as a challenge 20 that could result in a lack of qualified dietitians to fill senior positions. 19

Compensation and benefits.

Trends in compensation and benefits varied over time, sometimes keeping up with inflation 55 and sometimes not, 56 and a drop in wages was noted in the United States between 2015 and 2018 from USD 30.62/h to 30.45/h. 11 Higher wages were associated with higher education levels, as were specialty certifications, years of experience, and budgetary responsibility. 11 , 56 Direct client contact was associated with lower rates of pay, and supervisory roles were associated with higher pay rates. 11 , 56 Highest wages were reported in the “areas of food and nutrition management, consultation and business, and education and research.” 11

Some dietitians reported not working in dietetics because they found “a higher paying job outside of the field.” 11 Identified future needs included professional associations supporting members to achieve “recognition, respect and remuneration,” 56 creating job opportunities, 55 and giving members confidence in salary negotiations. 55 , 56

Recruitment and retention.

Opportunities reported to enhance staff retention included the chance for dietitians to specialize or undertake research, 57 opportunities for learning, 58 , 59 positive relationships with others (ie, staff and patients), 58 , 59 a supportive workplace culture, and recognition of the role of the dietitian from other staff members. 59 Factors reported to strengthen recruitment were enhanced job security and closeness of the position to home. 58

Nutrition informatics

Nutrition informatics was seen as a growth area 60–62 offering many opportunities for the dietetics profession. The primary benefit described was the gathering of large data sets that could be used to improve efficiency of interventions and enhance patient outcomes. 62–65 This area also was noted as a challenge because the dietetics profession was not adequately engaged in this field 66 and, at best, was moderately prepared. 63 , 66 It was reported that dietitians need to have greater input into nutritional informatics to ensure the systems developed are of benefit to the profession 62 , 64 and are in line with the Nutrition Care Process. 64 , 65 If dietitians were not involved in the development of nutrition informatics, studies suggested that another profession would fill these roles, 63 and the systems may not be fit for the purpose of dietetics. 64 To enhance dietetic involvement in nutrition informatics, future needs identified were training and professional development, 64 , 66 including certification, 64 leadership, 64 and mentoring. 63

Mobile health apps .

In the literature we reviewed, nutrition apps were seen as a valuable tool to assist in patient care 65 and, if used in conjunction with dietetic counselling, could enhance the client-dietitian relationship. 67 It was reported that dietitians want access to credible, well-designed apps that can be integrated into current practice. 67 However, mobile health apps (aka, mHealth apps) were reported to be poorly designed for collaborative treatment with a dietitian. 68 They were noted to have the potential to increase quality and efficiency of healthcare 68 by gathering real-time, noninvasive data; however, access to these data was reported to be limited. 69

Training, education, and advocacy on the part of dietetic associations were identified as future needs to ensure greater engagement with use of apps by dietitians. 70 In addition, greater collaboration among app designers, dietetic professional associations, and dietitians 67 was identified as necessary to ensure apps are optimal for use in dietetic practice. mHealth app development was identified as a growth industry and it was felt that if dietitians fail to be involved, they may leave these roles open to other, less qualified individuals. 71

Diversity within the workforce

Diversity was described as a challenge, with the dietetics profession being predominately homogenous (female and White) and not representative of the broader population. 72–74 This was reported to create a divide between the profession and the individuals they serve. 72 In addition to sex, gender 73 and race, 74 the need for diversity with reference to age, religion, socioeconomic status, 41 and disability 75 were also identified. Suggested ways to increase diversity included peer mentoring and targeted approaches to recruit more diverse students. 76 , 77

Specific areas of practice

Aspects relating to 7 different areas of practice were described. These included: high staff turnover in rural and remote practice, 78 low patient attendance rates in private practice, 79 the need for interprofessional support in primary health care, 80 the benefits of expanding food-service initiatives within the school setting, 81 and the challenges faced by academic dietetic educators 82 and sports dietitians requiring advocacy for services for college-level athletes. 83

Additional education

Advanced credentialing..

Dietitians were reported to have higher levels of advanced credentialing compared with other professions, 19 with many existing and planned advanced credentials available in the United States. 41 , 84 Opportunities associated with advanced credentialing were identified as expanding an individual dietitian’s scope of practice 84 and recognition of dietitians as leaders in food and nutrition by external stakeholders. 54 Advanced credentialing was also reported to lead to more rewarding job opportunities, 85 particularly in growth areas such as gerontology and chronic disease management. 86 Increased wages were a reported outcome of advanced credentialing, 51 and advanced credentialing was seen as beneficial to the profession because it resulted in more efficient and cost-effective interventions. 85

Challenges identified that are related to advanced credentialing included a previous lack of clearly defined pathways, 87 although many pathways were listed in a more recent article. 84 Residency programs were noted to be an effective method of delivery that incorporated practical learning 85 , 87 , 88 ; however, availability of funding for these was described as inconsistent 87 and sometimes acquired from multiple sources. 83 In addition, the general public were reported to lack understanding of the benefits of advanced credentialing 87 and employers yet to value or demand these credentials. 19

Extended scope of practice.

Extended scope of practice is the recognition of an additional skill that is outside of the defined scope of practice of a healthcare professional. 89 For dietitians, this can include activities such as blood glucose testing, adjusting insulin doses, inserting nasogastric tubes, 89 tube feeding management, 90 , 91 gastroenterologic treatment management, 92 and, depending on local legislation, prescribing of pharmaceuticals. 89 , 93 , 94

Dietitians in extended-scope-of-practice roles were noted to contribute to reduced healthcare costs resulting from streamlining of services and efficient patient-care management. 89–92 , 95 This was identified to be a result of fewer healthcare visits, 89 , 92 , 95 shorter waiting times, 91 and reduced hospital admissions. 90 Opportunities were reported to include an enhanced professional profile, with dietitians in extended-scope roles perceiving increased professional status 90 and recognition. 91 They also reported increased job satisfaction due to working to the full scope of their practice, and sharing the experience with other dietitians through a community of practice. 91 Acknowledgment and appreciation of advanced skills by the healthcare team were thought to result in enhanced working relationships. 90 , 91

The challenges associated with extended-scope roles related to the lack of strategic planning, with these roles reportedly forming out of unfilled vacancies. 90 To assist with more strategic planning, the development of a framework that incorporates the available options for extended scope of practice, 9 in addition to clearly defined learning programs and evaluation strategies, 91 was described as future needs. In 1 instance, it was reported that an extended-scope role caused conflict with nutrition nurse specialists because of the crossing of professional boundaries. 91 Supportive infrastructures were noted as essential for the creation and maintenance of these roles, such as clinical governance and stakeholder engagement. 91

Intrapersonal factors

Job satisfaction..

Trends in job satisfaction indicated that dietitians were moderately 96 or slightly 97 satisfied with their jobs, with dietitians in clinical positions reporting the lowest scores. 98 Age and experience were associated with higher levels of job satisfaction. 99 Key factors reported to enhance job satisfaction included: opportunities for promotion 96 , 97 , 99 , 100 and professional development, 100 flexibility in work hours, 100 a dynamic team environment, 100 a positive work atmosphere, 97 and higher salaries. 97–99 Other elements that were identified as increasing job satisfaction included “reward and recognition” 100 and “autonomy, meaning, recognition and respect.” 98 Issues with the physical environment and access to resources, 100 in addition to “poor perception of professional image,” 99 were reported to have a negative effect on job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction was a challenge, due to the reported costs associated with staff turnover, absenteeism, and reduced productivity 96 that occur when satisfaction levels are low. It was also seen as an opportunity, because increased job satisfaction was reported to lead to improved patient or customer satisfaction. 98

Stress and burnout.

Trends indicated that although dietitians had lower levels of burnout than other health professionals did, they still had moderate levels of emotional exhaustion. 101 In addition, their sense of personal accomplishment was only moderate, although this increased with age and years of experience. 101 The main challenge associated with stress and burnout was the potential for negative health consequences for the individual and decreased job performance, resulting in negative impacts on clients and organisations. 101

Challenges identified that increased stress and burnout were a perceived lack of respect from other healthcare professionals, due to a lack of understanding of the dietitian’s role. 102 In addition, unrealistic expectations as to what dietitians can achieve with limited time and resources and the lack of recognition associated with being a preceptor were reported as challenges. 102 Expectations that dietitians “conform to certain ideals, including thinness” were perceived to increase stress and burnout. 102 Future needs reported included additional training in “resilience, mindfulness and empathy,” as well as interprofessional approaches to combating stress. 102

Preparedness for practice.

Preparedness for practice was perceived as a challenge because of a lack of data on emerging areas of practice, 7 leading to difficulty in tailoring curricula toward employment opportunities. In addition, research specific to the workplace, involving graduates and employers, was identified as lacking. 7 Graduates reported feeling underprepared for new and emerging roles and were overwhelmed by the competition for traditional job opportunities. 103 Future needs identified included comprehensive graduate employment outcome data 7 and a realignment of course curricula to better prepare graduates for emerging roles. 103

Perceptions of the profession

Although the role of the dietitian was thought to have become less confusing to the public, 104 awareness of what a dietitian does was described as low. 105 Dietitians were reportedly seen as simply prescribers of diets, 105 , 106 and the general public had difficulty distinguishing between dietitians and other professions, such as naturopaths. 107 The level of education required to be a dietitian was reported to be poorly understood, 107 and there was an identified lack of clarity of the distinction between dietitians and nutritionists. 9 This was thought to result in a dilution of the credential and confusion regarding the dietitian’s role in healthcare. 9 As a profession, dietitians were reported to desire greater visibility and credibility and a clearer public profile that acknowledges them as experts in nutrition. 9 , 108

Dietitians also wished to be seen as a health professional who should be visited regularly, much like a dentist. 9 , 109 A transformation was reported to be occurring from the dietitian being a provider of information to being a provider of counselling-based treatment. 107 This was identified as an opportunity, because the public perceived treatments involving the transfer of information as requiring only short-term intervention, whereas they viewed a therapeutic, counselling style approach as a long-term strategy. 107 Both the dietetic profession and the public were reportedly struggling to adapt to this change from “information giver” to counsellor. 107

Strong partnerships with physicians provided opportunities, because referrals from them increased the likelihood of patients engaging in ongoing treatment. 107 In addition, physicians acknowledged that their own nutrition education is limited and they had positive opinions of the training and experience of dietitians. 107 Other opportunities identified included the work of special-interest groups with stakeholders relevant to their topic areas and incorporating a broader range of placement opportunities with a broader range of stakeholders. 9

Although dietitians felt they have much to contribute to the healthcare sector, they did not feel they had a voice that can be heard. 9 Professional associations were seen as the key to amplifying the voice of the profession and increasing visibility. 9 Some dietitians expressed concern that their professional association was not fully recognized by consumers or other healthcare practitioners. 110

Because of increasing competition in areas involving nutrition, future needs identified included “clear and compelling communication” with consumers to champion the brand of the dietitian above other potential sources of dietary advice. 105 Although consumers reported unfamiliarity with the credentials and training of dietitians, they did not have negative perceptions, so it was noted as beneficial for professional associations to continue to increase familiarity of the dietitian “brand.” 105 From the reviewed literature, we also identified that research was needed on the public perception of dietitians and nutritionists and to find ways to collaborate to provide enhanced clarity in distinguishing the 2 professions. 9

Support systems

Mentoring or professional support..

Mentoring was reported to offer opportunities in the form of enhanced confidence 111 , 112 and competence 112 , 113 and the chance for reflective practice. 111 , 113 These opportunities were noted to lead to improved productivity for both the mentor and mentee. 111 Other beneficial professional supports included working with another dietitian, peer-support networks, professional supervision, or working as part of a multidisciplinary, multicultural team. 112 Future needs identified included experienced and passionate mentors who create a trusting relationship and provide effective feedback. 113

Communities of practice.

Communities of practice were an effective method of increasing competence 114 and confidence to change practice, resulting in workforce retention 115 and development. 114

Protect the scope of practice

Protecting the scope of practice was described as “the greatest challenge” for the dietetic profession. 116 Competition in providing dietary advice and care was described as coming from other healthcare professionals, 19 , 22 whose expertise may have some nutrition overlap, as well as from individuals without academic training. 19

Opportunities within this area include the development of a workforce that adapts to the changing needs of society and whose value is acknowledged, because this type of workforce has less need to be protective of its scope of practice. 22 In addition, the creation of a more fluid scope of practice among healthcare professionals was noted as a way to enhance interdisciplinary collaboration. 21 A shared code of conduct for nutrition science professionals was suggested as a future need, because this may help define and protect the scope of practice. 117

Employment outcomes

Data related to employment outcomes had significant limitations. A comprehensive report from Australia was based on data from 2011, 118 now a decade out of date. From this report, trends indicated that less than half (45%) of individuals with a dietetic qualification worked as a dietitian, while 41% worked in unrelated occupations. 118 Another article reported on dietitians working in the public sector in a single state of Australia (namely, Victoria), 119 making this information biased toward hospital employment. Results from a study of dietitians who graduated from a single university in Canada indicated that employment may be increasingly difficult to obtain and graduates are having to work in rural or remote areas. 120

Registration or credentialing

Challenges faced in countries that were not members of the International Confederation of Dietetic Associations were distinctly different from those faced in countries where registration and credentialing are well established. In Sudan, professionalism and standards of practice were reported to be poorly defined. 121 In Ghana, an inadequate supply of dietitians in some areas and practitioners lacking formal qualifications were identified. 122 In China, a lack of educational opportunities and a poorly defined credentialing system were reported. 123

The purpose of this review was to investigate trends, challenges, opportunities, and future needs of the international dietetic workforce, from a diverse range of sources. The literature identified is predominantly focused on emerging areas of dietetic practice and skill development to meet current and future health nutrition needs of the population. This finding suggests the profession is aware of the need to adapt its skill set to successfully create jobs and have an impact on the changing food, nutrition, and health environments.

The number and scope of articles we identified demonstrate that the dietetics profession is contemplative of its position within society and how effectively it is serving communities. The profession is aware that healthcare delivery and the food and nutrition environment are changing, and is seeking information on how to adapt to these changes. There is considerable published work designed to understand and guide the future path of the profession, 9 , 20–22 with more underway. 23 Similar to the requirement that individual dietitians reflect on their own practice, 1 the profession as a whole appears to be reflective, questioning the place of dietetics within broader contexts.

The 2 most common themes identified in this scoping review were emerging or expanding areas of practice and skill development. Both of these topics have the potential to significantly enhance workforce development. Expansion of the profession into more diverse areas will lead to greater employment opportunities for dietitians, as well as increased capacity to meet the health and nutrition needs of society. Within the identified literature, emerging roles are most commonly presented as a way to expand the influence of the profession 9 and meeting the needs of society across multiple areas of healthcare and the food system. 20 , 21 The literature does not specify if emerging roles are considered important as a way to enhance employment, such as compensating for a lack of traditional roles (eg, clinical positions). Graduate employment data are lacking globally, resulting in a dearth of information regarding supply and demand for traditional roles.

The results of this review demonstrate that the topic of emerging areas of practice has been under discussion for at least a decade. 124 Despite this, dietetic education programs continue to focus on training students for clinical hospital roles, even though the majority of graduates are unlikely to work in this area. 118 Graduates are aware of the incongruence between training programs and employment opportunities, and they identify an overemphasis on clinical dietetics skills to the detriment of business and private practice skills. 103 Dietetics training programs need to reconsider their curricula to ensure training is reflective of workforce opportunities. To do this, it will be essential first to identify employment outcomes. Once these have been identified, training programs can consider implementing more diverse placement experiences to better prepare graduates for these emerging roles. Because teaching programs must meet accreditation standards, these may also need to be redefined to encourage contemporary placement settings.

Nutrition informatics was identified as an emerging area in this study, particularly relevant in light of the recent COVID-19 global pandemic. Large data sets, which can be gathered through informatics, have been identified as a valuable resource to help rapidly develop effective nutrition treatment strategies in situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic. 125 Well-designed mHealth apps can also compliment remote healthcare (eg, telehealth), as has become common during recent pandemic-associatedlockdowns. 126 Informatics will likely continue to be a rapidly expanding area for the dietetic profession as the world adapts to new healthcare models and global trends in technology.

This review has highlighted a significant lack of published workforce data. Although professional registration bodies generally gather information about their members, not all individuals with a dietetic qualification choose to become members of these organizations. Therefore, this information does not adequately capture individuals who take on nondietetic roles, nontraditional roles, those who remain unemployed. or those who choose not to be members. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics gathers workforce data on individuals who identify as working as dietitians; 10 however, as demonstrated in the Australian context, 118 almost half of individuals with a degree in dietetics work outside of the field. In addition, these data do not capture individuals who may be using the skills acquired during their dietetic degree but do not identify their primary role as “dietitian” (eg, academics teaching in dietetic programs). Comprehensive data that track graduates over time are necessary to identify if and why the profession is losing workforce members. These data are also essential to identify the most contemporary emerging areas as well as the potential impact on health and nutrition of populations. This, in turn, could guide the development of additional education priorities, and identification of specific industries in which advocacy can be targeted to enhance employment opportunities (eg, app developers 70 ).

Although graduate outcomes data will help identify current employment opportunities in the short term, ongoing research will also be needed. To remain relevant to consumer needs, more research should focus on what end users (ie, clients, patients, and the community) require from dietitians. If this area is not addressed, it is likely that other individuals will fill these gaps, as has been the case with unqualified social media “experts” providing nutrition information. 127 In addition, knowledge of the needs of the sectors and disciplines that interplay with the food system is required to identify trends, challenges, and opportunities where dietitians may play a role. It is also worth noting that none of the themes identified within this review has been “solved,” and all areas will require more exploration and development to strengthen the position of the dietetics profession. Leadership by the international dietetics community is needed, both in accreditation and training, to ensure the profession is at the forefront of contemporary developments.

Because food and nutrition have a role to play across many contexts and they affect every individual, the potential employment opportunities for dietitians are vast. Emerging employment areas include such diverse settings as policy development, agriculture, the education sector, 84 and social media. 38 By actively expanding the available fields of employment, the profession is embarking on a journey that appears to be unique to dietitians. Without precedent from other health disciplines, it is difficult to know how best to navigate these changes. What is most important is that the conversation is initiated and work begins in implementing the changes necessary to ensure the dietetic profession remains effective and relevant in the long term.

A strength of this review was that we included an international perspective; however, the restriction in publication language may have resulted in exclusion of perspectives from non–English-speaking countries, and, therefore, their perspectives remain unknown. The scoping review format and the inclusion of grey literature also meant that a broad range of opinions was included. However, this may also be a limitation, because the results were not generated solely from high-level evidence.

The global dietetic workforce is a potentially underused resource but recognizes its own need to adapt to the changing nutrition landscape. To understand this situation better, it is essential that professional bodies gather comprehensive workforce data that track graduates over time. This will assist the profession to stay abreast of emerging roles the workforce can use to expand its reach and effectiveness.

The authors express their gratitude to the unknown reviewers of this manuscript for their generous and constructive feedback.

Author contributions: All authors contributed to conceiving the study and to screening and data analysis. M.B. drafted the manuscript, and C.P., L.M., and S.G. provided critical revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. No individual meeting the authorship criteria has been omitted.

Funding . M.B. was supported by a scholarship from the Department of Nutrition, Dietetics and Food, Monash University, to undertake this work.

The funder had no input into the conception, design, performance, or approval of the work.

Declaration of interests. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

The following Supporting Information is available through the online version of this article at the publisher’s website.

Table S1 . A complete list of articles, identified through database searches and the Google search engine, that were included in the systematic scoping review of trends, challenges, opportunities, and future needs of the dietetic workforce.

Table S2 . Extended results of topics identified in the systematic scoping review

International Confederation of Dietetic Associations. International competency standards for dietitian-nutritionists. Available at: https://www.internationaldietetics.org/Downloads/International-Competency-Standards-for-Dietitian-N.aspx . Accessed October 30, 2020.

Dietitians Australia. Dietitian or nutritionist. Available at: https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/what-dietitans-do/dietitian-or-nutritionist/ . Accessed June 3, 2021.

Afshin A , Sur PJ , Fay KA , et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 . Lancet . 2019 ; 393 : 1958 – 1972 .

Google Scholar

Willett W , Rockström J , Loken B , et al. Food in the anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems . Lancet. 2019 ; 393 : 447 – 492 .

Kleve S , Booth S , Davidson ZE , et al. Walking the food security tightrope—exploring the experiences of low-to-middle income Melbourne households . Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018 ; 15 : 2206 .

Smith MD , Rabbitt MP , Coleman-Jensen A. Who are the world’s food insecure? New evidence from the Food and Agriculture Organization’s food insecurity experience scale . World Dev . 2017 ; 93 : 402 – 412 .

Morgan K , Kelly JT , Campbell KL , et al. Dietetics workforce preparation and preparedness in Australia: a systematic mapping review to inform future dietetics education research . Nutr Diet. 2019 ; 76 : 47 – 56 .

Ward B , Rogers D , Mueller C , et al. Entry-level dietetics practice today: results from the 2010 commission on dietetic registration entry-level dietetics practice audit . J Am Diet Assoc. 2011 ; 111 : 914 – 941 .

Hickson M , Child J , Collinson A. Future dietitian 2025: informing the development of a workforce strategy for dietetics . J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018 ; 31 : 23 – 32 .

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook: dietitians and nutritionists. US Department of Labor. Updated September 1, 2020 . Available at: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/dietitians-and-nutritionists.htm . Accessed June 22, 2020

Rogers D. Compensation and benefits survey 2017 . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018 ; 118 : 499 – 511 .

Morgan K , Campbell KL , Sargeant S , et al. Preparing our future workforce: a qualitative exploration of dietetics practice educators’ experiences . J Hum Nutr Diet. 2019 ; 32 : 247 – 258 .

Jacobs RL , Hawley JD. The emergence of ‘workforce development’: definition, conceptual boundaries and implications . In: International Handbook of Education for the Changing World of Work . Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer ; 2009 : 2537 – 2552 .

Google Preview

Government of Western Australia. Department of Training and Workforce Development. Workforce development. Updated December 17, 2019. Available at: https://www.dtwd.wa.gov.au/workforce-development . Accessed October 22, 2020 .

Green LA, Lanier D, Yawn BP, Dovey SM, Fryer GE. The ecology of medical care revisited. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:2021–2025.

Smith AC , Thomas E , Snoswell CL , et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) . J Telemed Telecare 2020 ; 26 : 309 – 313 . [CVOCROSSCVO]

Taylor M , Hill S. Consumer Expectations and Healthcare in Australia . Deakin, Australian Capital Territory, Australia : Australian Healthcare and Hospitals Association ; 2014 :

Pollard CM , Pulker CE , Meng X , et al. Who uses the Internet as a source of nutrition and dietary information? An Australian population perspective . J Med Internet Res. 2015 ; 17 : E209 .

Nyland N , Lafferty L. Implications of the Dietetics Workforce Demand Study . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 ; 112 : S92 – S94 .

Kicklighter JR , Dorner B , Hunter AM , et al. Visioning Report 2017: a preferred path forward for the nutrition and dietetics profession . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017 ; 117 : 110 – 127 .

Rhea M , Bettles C. Future changes driving dietetics workforce supply and demand: Future Scan 2012-2022 . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 ; 112 : S10 – S24 .

Rhea M , Bettles C. Four futures for dietetics workforce supply and demand: 2012-2022 Scenarios . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 ; 112 : S25 – S34 .

Council of Deans of Nutrition and Dietetics Australia and New Zealand. Futures Project. Available at: http://dieteticdeans.com/research.php . Accessed February 1, 2021.

Tricco AC , Lillie E , Zarin W , et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation . Ann Intern Med. 2018 ; 169 : 467 – 473 .

Peters M , Godfrey C , McInerney P , et al. Chapter 11: Scoping eeviews (2020 version). In: JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis . Available at: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global . Accessed February 26, 2020.

Godin K , Stapleton J , Kirkpatrick SI , et al. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada . Syst Rev. 2015 ; 4 : 138 – 138 .

Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation. Available at: www.covidence.org .

Hsieh H-F , Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis . Qual Health Res. 2005 ; 15 : 1277 – 1288 .

Assarroudi A , Heshmati Nabavi F , Armat MR , et al. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process . J Res Nurs . 2018 ; 23 : 42 – 55 .

Boeije H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews . Int J Methodol . 2002 ; 36 : 391 – 409 .

Mast A , DeMicco FJ. The medical SPA in healthcare: exploring the role of the registered dietitian. In: DeMicco FJ , Weis S , eds. Medical Tourism and Wellness: Hospitality Bridging Healthcare (H2H) . Boca Raton, FL : Taylor & Francis Group ; 2017 : 147 – 157 . doi:10.1201/9781315365671. [CVOCROSSCVO]

Biordi DL , Heitzer M , Mundy E , et al. Improving access and provision of preventive oral health care for very young, poor, and low-income children through a new interdisciplinary partnership . Am J Public Health. 2015 ; 105(suppl 2 ): e23 – e29 .

Blades M. Dietitians as entrepreneurs . Nutr Food Sci . 2013 ; 43 : 339 – 343 .

Orenstein BW , Conference currents. The rise of supermarket RDs . Today's Diet . 2014 ; 16 : 12 – 13 . [CVOCROSSCVO]

Mincher JL , Leson SM. Worksite wellness: an ideal career option for nutrition and dietetics practitioners . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014 ; 114 : 1895 – 1901 .

Goodman EM , Redmond J , Elia D , et al. Practice roles and characteristics of integrative and functional nutrition registered dietitian nutritionists . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018 ; 118 : 2356 – 2368.e1 .

Li SX , Collins J , Lawson S , et al. A preliminary qualitative exploration of dietitians' engagement with genetics and nutritional genomics: perspectives from international leaders . J Allied Health. 2014 ; 43 : 221 – 228 .

Chan T , . Qualitative Comparison of Nutrition Advice and Content from Registered Dietitian and Non-Registered Dietitian Bloggers. Ann Arbor, MI: Bradley University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2018 .

Fanzo JC , Graziose MM , Kraemer K , et al. Educating and training a workforce for nutrition in a post-2015 world . Adv Nutr. 2015 ; 6 : 639 – 647 .

Gaba A , Shrivastava A , Amadi C , et al. The nutrition and dietetics workforce needs skills and expertise in the New York metropolitan area . Glob J Health Sci. 2015 ; 8 : 14 – 24 .

Winterfeldt EA. Nutrition and Dietetics: Practice and Future Trends . 2nd ed. Burlington, MA : Jones & Bartlett Learning ; 2017 .

Penland A , Henry B. Influences Related to the Diffusion of Innovations Theory on the Incorporation of Sustainable Food Systems Practices within Dietetic Responsibilities. [PhD dissertation]. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois; 2014 ; 156 .[CVOCROSSCVO]

MacDonald Werstuck M , Buccino J. Dietetic staffing and workforce capacity planning in primary health care . Can J Diet Pract Res. 2018 ; 79 : 181 – 185 .

Cormack B , Oliver C , Farrent S , et al. Neonatal dietitian resourcing and roles in New Zealand and Australia: a survey of current practice . Nutr Diet 2019 ; 24 : 24 . [CVOCROSSCVO]

de Bock M , Jones TW , Fairchild J , et al. Children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes in Australasia: an online survey of model of care, workforce and outcomes . J Paediatr Child Health. 2019 ; 55 : 82 – 86 .

Ward F , O'Riordan J. A review of staffing levels and activity in paediatric dietetics . J Hum Nutr Diet. 2015 ; 28 : 95 – 106 .

Wilkinson SA , Duncan L , Barrett C , et al. Mapping of allied health service capacity for maternity and neonatal services in the southern Queensland Health Service District . Aust Health Rev. 2013 ; 37 : 614 – 619 .

Siopis G , Jones A , Allman-Farinelli M. The dietetic workforce distribution geographic atlas provides insight into the inequitable access for dietetic services for people with type 2 diabetes in Australia . Nutr Diet. 2020 ; 77 : 121 – 130 .

Brown LJ , Williams LT , Capra S. Developing dietetic positions in rural areas: what are the key lessons? Rural and Remote Health 2012 ; 12 : 1923 –1923.

Miller A . An in-depth analysis of the workforce characteristics of registered dietitians in Ontario . Ottawa, Canada: University of Ontario Institute of Technology, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2011 .

Rogers D. Dietetics trends as reflected in various primary research projects, 1995-2011 . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 ; 112 : S64 – S74 .

Hooker RS , Williams JH , Papneja J , et al. Dietetics supply and demand: 2010-2020 . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 ; 112 (suppl 3 ): S75 – S91 .

Barrett ST. U.S. Health Care Workforce: Supply and Demand Projections and Federal Planning Efforts. Dietitians and Nutritionists . Hauppauge, NY : Nova Science Publishers ; 2016 : 97 – 100 .

Stein K , Rops M. The Commission on Dietetic Registration: ahead of the trends for a competent 21st century workforce . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016 ; 116 : 1981 – 1997.e7 .

McCollum G. Compensation and benefits: positive trends . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014 ; 114 : 9 – 9 .

Escott-Stump SA. Increasing members' compensation, perceived value . J Am Diet Assoc. 2011 ; 111 : 1643 .

Plint H , Ball L , Hughes R , et al. Ten-year follow up of graduates from the Aspiring Dietitians Study: implications for dietetic workforce development . Nutr Diet. 2016 ; 73 : 241 – 246 .

Hughes R , Odgers-Jewell K , Vivanti A , et al. A study of clinical dietetic workforce recruitment and retention in Queensland . Nutr Diet . 2011 ; 68 : 70 – 76 .

Milosavljevic M , Noble G , Goluza I , et al. New South Wales public-hospital dietitians and how they feel about their workplace: an explorative study using a grounded theory approach . Nutr Diet . 2015 ; 72 : 107 – 113 .

Aase S. You, improved: understanding the promises and challenges nutrition informatics poses for dietetics careers . J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 ; 110 : 1794 – 1798 .

Ayres EJ , Hoggle LB. Advancing practice: using nutrition information and technology to improve health-the nutrition informatics global challenge . Nutr Diet . 2012 ; 69 : 195 – 197 .

Rusnak S , Charney P. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: nutrition informatics . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019 ; 119 : 1375 – 1382 .

Maunder K , Walton K , Williams P , et al. Strategic leadership will be essential for dietitian eHealth readiness: a qualitative study exploring dietitian perspectives of eHealth readiness . Nutr Diet. 2019 ; 76 : 373 – 381 .

Molinar LS , Childers AF , Hoggle L , et al. Increase in use and demand for skills illustrated by responses to Nutrition Informatics survey . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016 ; 116 : 1836 – 1842 .

Jones A , Mitchell LJ , O'Connor R , et al. Investigating the perceptions of primary care dietitians on the potential for information technology in the workplace: qualitative study . J Med Internet Res. 2018 ; 20 : e265 .

Maunder K , Walton K , Williams P , et al. eHealth readiness of dietitians . J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018 ; 31 : 573 – 583 .

Chen J , Lieffers J , Bauman A , et al. Designing health apps to support dietetic professional practice and their patients: qualitative results from an international survey . JMIR mHealth Uhealth. 2017 ; 5 : e40 .

Harricharan M , Gemen R , Celemin LF , et al. Integrating mobile technology with routine dietetic practice: the case of myPace for weight management . Proc Nutr Soc. 2015 ; 74 : 125 – 129 .

Chen J. Advancing Dietetic Practice through the Implementation and Integration of Smartphone Apps . Australia :University of Sydney; 2018 . Available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/259893611 .

Chen J , Lieffers J , Bauman A , et al. The use of smartphone health apps and other mobile health (mHealth) technologies in dietetic practice: a three country study . J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017 ; 30 : 439 – 452 .

Boyce B. Nutrition apps: opportunities to guide patients and grow your career . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014 ; 114 : 13 – 14 .

Warren JL. Diversity in Dietetics Matters: Experiences of Minority Female Registered Dietitians in Their Route to Practice . Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Akron, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing ; 2017 .

Joy P , Gheller B , Lordly D. Men who are dietitians: deconstructing gender within the profession to inform recruitment . Can J Diet Pract Res. 2019 ; 80 : 209 – 212 .

Whelan M. Latina and Black women's Perceptions of the dietetics major and profession . Buffalo, NY: State University of New York at Buffalo , ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2017 .

Baxter SD , Gordon B , Cochran N. Enhancing diversity and the role of individuals with disabilities in the dietetics profession . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020 ; 120 : 757 – 765 .

Bergman EA. Building a brighter tomorrow: diversity, mentoring, and the future of dietetics . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013 ; 113 : S5 .

Burt KG , Delgado K , Chen M , et al. Strategies and recommendations to increase diversity in dietetics . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019 ; 119 : 733 – 738 .

Brown L , Williams L , Capra S. Going rural but not staying long: recruitment and retention issues for the rural dietetic workforce in Australia . Nutr Diet . 2010 ; 67 : 294 – 302 .

Ball L , Larsson R , Gerathy R , et al. Working profile of Australian private practice accredited practising dietitians . Nutr Diet 2013 ; 70 : 196 – 205 . [CVOCROSSCVO]

Beckingsale L , Fairbairn K , Morris C. Integrating dietitians into primary health care: benefits for patients, dietitians and the general practice team . J Prim Health Care. 2016 ; 8 : 372 – 380 . doi:10.1071/HC16018

Hayes D , Dodson L. Practice paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: comprehensive nutrition programs and services in schools . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018 ; 118 : 920 – 931 .

Morgan K , Reidlinger DP , Sargeant S , et al. Challenges in preparing the dietetics workforce of the future: an exploration of dietetics educators’ experiences . Nutr Diet. 2019 ; 76 : 382 – 391 .

Erdman KA. A lifetime pursuit of a sports nutrition practice . Can J Diet Pract Res. 2015 ; 76 : 150 – 154 .

Academy Quality Management Committee. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: revised 2017 scope of practice for the registered dietitian nutritionist . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018 ; 118 : 141 – 165 .

Brody RA , Skipper A , Pavlinac J , et al. Achieving focused area and advanced practice status . Top Clin Nutr . 2013 ; 28 : 220 – 232 .

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Occupational Outlook Handbook, 2010-2011 Library Edition, Bulletin 2800. Health Diagnosing and Treating Practitioners: Dietitians and Nutritionists . 2010 ; 366 – 369 . Available at: https://centerforinquiry.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/33/quackwatch/2010-11OOH.pdf . Accessed August 30, 2021.

Maillet JO , Brody RA , Skipper A , et al. Framework for analyzing supply and demand for specialist and advanced practice registered dietitians . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 ; 112 : S47 – S55 .

Sowa M , Steele C. Establishing a pediatric registered dietitian (RD) residency program . Infant, Child, and Adolescent Nutrition . 2015 ; 7 : 38 – 43 .

Dietitians Australia. Dietitian scope of practice. Available at: https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/maintaining-professional-standards/dietitian-scope-of-practice/ . Accessed June 22, 2020.

Stanley W , Borthwick AM. Extended roles and the dietitian: community adult enteral tube care . J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013 ; 26 : 298 – 305 .

Simmance N , Cortinovis T , Green C , et al. Introducing novel advanced practice roles into the health workforce: dietitians leading in gastrostomy management . Nutr Diet. 2019 ; 76 : 14 – 20 .

Ryan D , Pelly F , Purcell E. The activities of a dietitian-led gastroenterology clinic using extended scope of practice . BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 ; 16 : 604 – 604 .

Raghunandan R , Tordoff J , Smith A. Non-medical prescribing in New Zealand: an overview of prescribing rights, service delivery models and training . Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2017 ; 8 : 349 – 360 .

Smith A. Non-medical prescribing in New Zealand: is it achieving its aims ? Int J Integr Care . 2017 ; 17 : 51 – 52 .

Palermo C. Creating the dietitians of the future . Nutr Diet. 2017 ; 74 : 323 – 326 .

Chen AH , Jaafar SN , Noor ARM. Comparison of job satisfaction among eight health care professions in private (non-government) settings . Malays J Med Sci 2012 ; 19 : 19 – 26 . [CVOCROSSCVO]

Sung KH , Kim HA , Jung HY. Comparative analysis of job satisfaction factors between permanently and temporarily employed school foodservice dietitians in Gyeongsangnam-do . J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr . 2013 ; 42 : 808 – 817 .

Martin J , Zaragoza M. Job Satisfaction among Registered Dietitians in Various Settings in the United States . Loma Linda, CA : Loma Linda University ; 2018 .

Visser J , Mackenzie A , Marais D. Job satisfaction of South African registered dietitians . South Afr J Clin Nutr . 2012 ; 25 : 112 – 119 .

Cody S , Ferguson M , Desbrow B. Exploratory investigation of factors affecting dietetic workforce satisfaction . Nutr Diet . 2011 ; 68 : 195 – 200 .

Gingras J , de Jonge L , Purdy N. Prevalence of dietitian burnout . J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010 ; 23 : 238 – 243 .

Eliot KA , Kolasa KM , Cuff PA. Stress and burnout in nutrition and dietetics: strengthening interprofessional ties . Nutr Today. 2018 ; 53 : 63 – 67 .

Morgan K , Campbell KL , Sargeant S , et al. Preparedness for advancing future health: a national qualitative exploration of dietetics graduates’ experiences . Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2020 ; 25 : 31 – 53 .

Gilbride JA , Parks SC , Dowling R. The potential of nutrition and dietetics practice . Top Clin Nutr . 2013 ; 28 : 209 – 219 .

Semans D. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics registered dietitian brand evaluation research results . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014 ; 114 : 1640 – 1646 .

Camossa ACA , Telarolli Junior R , Machado MLT. What dieticians do, in practice and in theory, in the family health strategy: views of health team professionals . Rev Nutr. 2012 ; 25 : 89 – 106 .

Endevelt R , Gesser-Edelsburg A. A qualitative study of adherence to nutritional treatment: perspectives of patients and dietitians . Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014 ; 8 : 147 – 154 .

Seher CL. The ‘Making’ and ‘Unmaking’ of the Dietetics Professional: A Feminist Poststructural Policy Analysis of Dietetics Boss Texts. Kent, OH: Kent State University; 2018 .

Iufer J , What does the dietitian of the future look like? Available at: https://foodandnutrition.org/blogs/stone-soup/dietitian-future-look-like/ . Accessed June 22, 2020.

Rogers D. Report on the Academy/Commission on Dietetic Registration 2016 Needs Satisfaction survey . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017 ; 117 : 626 – 631 .

Payne-Palacio JR , Canter DD. The Profession of Dietetics: A Team Approach. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning ; 2016 :

Beckingsale L , Fairbairn K , Morris C. ‘ Two working together is so much better than just one’: professional support needs of primary healthcare dietitians . Nutr Diet. 2016 ; 73 : 220 – 228 .

Palermo C , Hughes R , McCall L. An evaluation of a public health nutrition workforce development intervention for the nutrition and dietetics workforce . J Hum Nutr Diet . 2010 ; 23 : 244 – 253 .

Delbridge R , Wilson A , Palermo C. Measuring the impact of a community of practice in Aboriginal health . Stud Continuing Educ . 2018 ; 40 : 62 – 75 .

Wilson AM , Delbridge R , Palermo C. Supporting dietitians to work in Aboriginal health: qualitative evaluation of a Community of Practice mentoring circle . Nutr Diet. 2017 ; 74 : 488 – 494 .

Boyce B. Opening up opportunities through work in public policy . J Am Diet Assoc. 2011 ; 111 : 980 – 985 .

Collins J. Generational change in nutrition and dietetics: the millennial dietitian . Nutr Diet. 2019 ; 76 : 369 – 372 .

Health Workforce Australia. Australia's health workforce series: dietitians in focus. The Commonwealth of Australia. Available at: http://iaha.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/HWA_Australias-Health-Workforce-Series_Dietitians-in-focus_vF_LR.pdf . Accessed June 22, 2020.

Department of Health and Human Services. Victorian Allied Health Workforce Research Program: dietetics workforce report. Available at: http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/537387 . Accessed June 19, 2020.

Mudryj A , Farquhar K , Spence K , et al. Employment outcomes among registered dietitians following graduation in Manitoba . Can J Diet Pract Res. 2019 ; 80 : 87 – 90 .

Aljaaly E. The profession and practice of nutrition and dietetics in Sudan . IJSR. 2016 ; 6 : 90 – 102 .

Aryeetey RN , Boateng L , Sackey D. State of dietetics practice in Ghana . Ghana Med J. 2014 ; 48 : 219 – 224 .

Sun L , Dwyer J. Dietetics in China at the crossroads . Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2014 ; 23 : 16 – 26 . doi:10.6133/apjcn.2014.23.1.19

Aase S. Is an overseas dietetics career opportunity for you? J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 ; 110 : S33 – S35 .

Handu D , Moloney L , Rozga M , et al. Malnutrition care during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for registered dietitian nutritionists . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021 ; 121 : 979 – 987 .

Mehta P , Stahl MG , Germone MM , et al. Telehealth and nutrition support during the COVID-19 pandemic . J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020 ; 120 : 1953 – 1957 .

Adamski M , Truby H , M Klassen K , et al. Using the internet: nutrition information-seeking behaviours of lay people enrolled in a massive online nutrition course . Nutrients 2020 ; 12 : 750 .

- credentialing

- science of nutrition

- social support

- scope of practice

- informatics

Supplementary data

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1753-4887

- Print ISSN 0029-6643

- Copyright © 2024 International Life Sciences Institute

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Mindful Eating

What Is It?

Mindful eating stems from the broader philosophy of mindfulness, a widespread, centuries-old practice used in many religions. Mindfulness is an intentional focus on one’s thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations in the present moment. Mindfulness targets becoming more aware of, rather than reacting to, one’s situation and choices. Eating mindfully means that you are using all of your physical and emotional senses to experience and enjoy the food choices you make. This helps to increase gratitude for food, which can improve the overall eating experience. Mindful eating encourages one to make choices that will be satisfying and nourishing to the body. However, it discourages “judging” one’s eating behaviors as there are different types of eating experiences. As we become more aware of our eating habits, we may take steps towards behavior changes that will benefit ourselves and our environment.

How It Works

Mindful eating focuses on your eating experiences, body-related sensations, and thoughts and feelings about food, with heightened awareness and without judgment. Attention is paid to the foods being chosen, internal and external physical cues, and your responses to those cues. [1] The goal is to promote a more enjoyable meal experience and understanding of the eating environment. Fung and colleagues described a mindful eating model that is guided by four aspects: what to eat , why we eat what we eat , how much to eat , and how to eat . [1]

Mindful eating:

- considers the wider spectrum of the meal: where the food came from, how it was prepared, and who prepared it

- notices internal and external cues that affect how much we eat

- notices how the food looks, tastes, smells, and feels in our bodies as we eat

- acknowledges how the body feels after eating the meal

- expresses gratitude for the meal

- may use deep breathing or meditation before or after the meal

- reflects on how our food choices affect our local and global environment

Seven practices of mindful eating

- Honor the food . Acknowledge where the food was grown and who prepared the meal. Eat without distractions to help deepen the eating experience.

- Engage all senses . Notice the sounds, colors, smells, tastes, and textures of the food and how you feel when eating. Pause periodically to engage these senses.

- Serve in modest portions . This can help avoid overeating and food waste. Use a dinner plate no larger than 9 inches across and fill it only once.

- Savor small bites, and chew thoroughly . These practices can help slow down the meal and fully experience the food’s flavors.

- Eat slowly to avoid overeating . If you eat slowly, you are more likely to recognize when you are feeling satisfied, or when you are about 80% full, and can stop eating.

- Don’t skip meals . Going too long without eating increases the risk of strong hunger, which may lead to the quickest and easiest food choice, not always a healthful one. Setting meals at around the same time each day, as well as planning for enough time to enjoy a meal or snack reduces these risks.

- Eat a plant-based diet, for your health and for the planet . Consider the long-term effects of eating certain foods. Processed meat and saturated fat are associated with an increased risk of colon cancer and heart disease . Production of animal-based foods like meat and dairy takes a heavier toll on our environment than plant-based foods.

Watch: Practicing mindful eating

The Research So Far

The opposite of mindful eating, sometimes referred to as mindless or distracted eating, is associated with anxiety, overeating, and weight gain. [3] Examples of mindless eating are eating while driving, while working, or viewing a television or other screen (phone, tablet). [4] Although socializing with friends and family during a meal can enhance an eating experience, talking on the phone or taking a work call while eating can detract from it. In these scenarios, one is not fully focused on and enjoying the meal experience. Interest in mindful eating has grown as a strategy to eat with less distractions and to improve eating behaviors.

Intervention studies have shown that mindfulness approaches can be an effective tool in the treatment of unfavorable behaviors such as emotional eating and binge eating that can lead to weight gain and obesity, although weight loss as an outcome measure is not always seen. [5-7] This may be due to differences in study design in which information on diet quality or weight loss may or may not be provided. Mindfulness addresses the shame and guilt associated with these behaviors by promoting a non-judgmental attitude. Mindfulness training develops the skills needed to be aware of and accept thoughts and emotions without judgment; it also distinguishes between emotional versus physical hunger cues. These skills can improve one’s ability to cope with the psychological distress that sometimes leads to binge eating. [6]

Mindful eating is sometimes associated with a higher diet quality, such as choosing fruit instead of sweets as a snack, or opting for smaller serving sizes of calorie-dense foods. [1]