IMF: Why research and development is a crucial part of economic growth

Analysis suggests that the composition of R&D matters for growth. Image: Unsplash/Lucas Vasques

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Philip Barrett

Diaa noureldin, jean-marc natal, niels-jakob hansen.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, emerging technologies.

- Analysis by the IMF suggests that research and development are vital for economic progress.

- Cross-border collaboration is also crucial to help foster the innovation needed for long-term growth.

- COVID-19 vaccines are an example of innovation, helping save lives and bring forward the reopening of many economies.

The pandemic has rolled back decades of economic progress and wrought havoc on public finances. To build back better and fight climate change, sizable public investment needs to be sustainably financed. Boosting long-term growth—and thereby tax revenue—has rarely felt more pressing.

But what are the drivers of long-term growth? Productivity—the ability to create more outputs with the same inputs—is an important one. In our latest World Economic Outlook , we emphasize the role of innovation in stimulating long-term productivity growth . Surprisingly, productivity growth has been declining for decades in advanced economies despite steady increases in research and development (R&D), a proxy for innovation effort.

Knowledge transfer between countries is an important driver of innovation.

Our analysis suggests that the composition of R&D matters for growth. We find that basic scientific research affects more sectors, in more countries and for a longer time than applied research (commercially oriented R&D by firms), and that for emerging market and developing economies, access to foreign research is especially important. Easy technology transfer, cross-border scientific collaboration and policies that fund basic research can foster the kind of innovation we need for long-term growth.

Inventions draw on basic scientific knowledge

While applied research is important to bring innovations to market, basic research expands the knowledge base needed for breakthrough scientific progress. A striking example is the development of COVID-19 vaccines, which in addition to saving millions of lives has helped bring forward the reopening of many economies, potentially injecting trillions into the global economy . Like other major innovations, scientists drew on decades of accumulated knowledge in different fields to develop the mRNA vaccines.

Basic research is not tied to a particular product or country and can be combined in unpredictable ways and used in different fields. This means that it spreads more widely and remains relevant for a longer time than applied knowledge. This is evident from the difference in citations between scientific articles used for basic research, and patents (applied research). Citations for scientific articles peak at about eight years versus three years for patents.

Have you read?

How to find the best work-life balance for you, according to science, science denial: why it happens and 5 things you can do about it, this ‘citizen science’ project means anyone can help map the great barrier reef - from the comfort of home.

Spillovers are important for emerging markets and developing economies

While the bulk of basic research is conducted in advanced economies, our analysis suggests that knowledge transfer between countries is an important driver of innovation, especially in emerging market and developing economies.

Emerging market and developing economies rely much more on foreign than homegrown research (basic and applied) for innovation and growth. In countries where education systems are strong and financial markets deep, the estimated effect of foreign technology adoption on productivity growth—through trade, foreign direct investment or learning-by-doing—is particularly large. As such, emerging market and developing economies may find that policies to adapt foreign knowledge to local conditions are a better avenue for development than investing directly in homegrown basic research.

We gauge this by looking at data on research stocks —measures of accumulated knowledge through research expenditure. As the chart shows, a 1-percentage-point increase in foreign basic knowledge increases annual patenting in emerging market and developing economies by around 0.9 percentage point more than in advanced economies.

Innovation is a key driver of productivity growth

Why does patenting matter? It’s a proxy for measuring innovation. An increase in the stock of patents by 1 percent can increase productivity per worker by 0.04 percent. That may not sound like much, but it adds up. Small increases over time improve living standards.

We estimate that a 10 percent permanent increase in the stock of a country’s own basic research can increase productivity by 0.3 percent. The impact of the same increase in the stock of foreign basic research is larger. Productivity increases by 0.6 percent. Because these are average numbers only, the impact on emerging markets and developing economies is likely to be even bigger.

Basic science also plays a larger role in green innovation (including renewables) than in dirty technologies (such as gas turbines), suggesting that policies to boost basic research can help tackle climate change.

The Young Scientists Community , founded in 2008, brings together extraordinary rising-star scientists from various academic disciplines and geographies, all under the age of 40. Their mission is to help leaders engage with science and the role it plays in society.

The World Economic Forum trains and empowers Young Scientists to communicate cutting-edge research and champion evidence-based decision making, and in doing so, helps build a diverse global community of next-generation scientific leaders.

Each year, the Forum selects and onboards a new class of Young Scientists, adding to the growing 400+ alumni community. Meet the 2020 Young Scientists tackling the world’s most pressing challenges through scientific innovation. Get in touch to find out more about the community.

Policies for a more buoyant and inclusive future

Because private firms can only capture a small part of the uncertain financial reward of engaging in basic research, they tend to underinvest in it, providing a strong case for public policy intervention. But designing the right policies—including determining how you fund research—can be tricky. For example, funding basic research only at universities and public labs could be inefficient. Potentially important synergies between the private and public sector would be lost. It may also be difficult to disentangle basic and applied private research for the sake of subsidizing only the former.

Our analysis shows that an implementable hybrid policy that doubles subsidies to private research (basic and applied alike) and boosts public research expenditure by a third could increase productivity growth in advanced economies by 0.2 percentage point a year. Better targeting of subsidies to basic research and closer public‑private cooperation could boost this even further, at lower cost for public finances.

These investments would start to pay for themselves within about a decade and would have a sizeable impact on incomes. We estimate that per capita incomes would be about 12 percent higher than they are now had these investments been made between 1960 and 2018.

Finally, because of important spillovers to emerging markets, it is also key to ensure the free flow of ideas and collaboration across borders.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Emerging Technologies .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How to build the skills needed for the age of AI

Juliana Guaqueta Ospina

April 11, 2024

Space is booming. Here's how to embrace the $1.8 trillion opportunity

Nikolai Khlystov and Gayle Markovitz

April 8, 2024

These 6 countries are using space technology to build their digital capabilities. Here’s how

Simon Torkington

What is e-voting? Who’s using it and is it safe?

Victoria Masterson

April 4, 2024

This Dubai-based company turns used cooking oil into biofuels

4 lessons from Jane Goodall as the renowned primatologist turns 90

Gareth Francis

April 3, 2024

- Utility Menu

research page title

The Growth Lab hosts an interdisciplinary team that iterates between theory and practice of economic development to improve our understanding of how economies grow.

Our trademark methodologies, Economic Complexity and Growth Diagnostics, have revolutionized development thinking and inspired many places to reconsider their economic strategies.

Research Questions We Seek To Answer

What kinds of processes do countries, regions, and cities use to diversify their productive capacity and accumulate productive knowledge in order to accelerate growth?

How can migration and mobility help foster economic development and how do complementary skills impact labor market dynamics?

What is the role of special economic zones in tackling product diversification opportunities and how does it impact knowledge transfer and migration?

How can countries prioritize key policy decisions and sequencing to achieve their long-term strategy?

Search by Country Name, Project title, etc.

Academic research.

Our multidisciplinary team is working to uncover the mechanisms behind economic growth. Our three research pillars are: Economic Transformation; Diffusion of Knowledge and Technology; and Coordination of Knowhow.

- Publications

Policy Research

We are developing rigorous place-specific research on the constraints to sustained shared prosperity, translating these insights into inputs for policy design and collaborating with practitioners to learn from the process of implementation.

Research Spotlight

The Economic Tale of Two Amazons

This new paper synthesizes the findings of two Growth Lab projects that studied the nature of economic growth in the Peruvian and Colombian Amazon. While deforestation is often treated as inevitable to serve human needs, local and global, our research fails to find evidence of a tradeoff between economic growth and forest protection. The economic drivers in the Amazon are its urban areas often located far from the forest.

Read the Paper

The Impact of Return Migration on Employment and Wages in Mexican Cities

How does return migration affect local workers in Mexico? While migrants returning from the U.S. increase the local labor supply, they also return with new skills and knowhow, having been exposed to a more advanced U.S. economy. New research by Ricardo Hausmann and others, recently published in the Journal of Urban Economics , finds that returnees create jobs by inducing growth in the industries that hire them.

Read article Explore our migration research

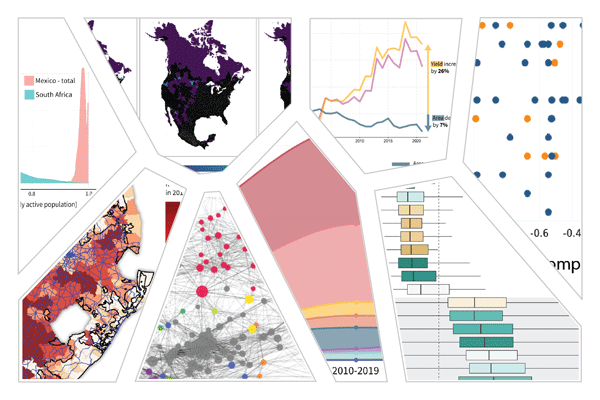

Top Visual Insights of 2023

Our multi-disciplinary team extended our pioneering research agenda to five continents in 2023. Our researchers engaged the world in leveraging decarbonization as a pathway for growth, identifying the barriers to migration and mobility of skills, examining inequality in cities and the effects of remoteness on growth, and understanding the role of innovation in economic complexity.

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Study: Democracy fosters economic growth

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

As long as democracy has existed, there have been democracy skeptics — from Plato warning of mass rule to contemporary critics claiming authoritarian regimes can fast-track economic programs.

But a new study co-authored by an MIT economist shows that when it comes to growth, democracy significantly increases development. Indeed, countries switching to democratic rule experience a 20 percent increase in GDP over a 25-year period, compared to what would have happened had they remained authoritarian states, the researchers report.

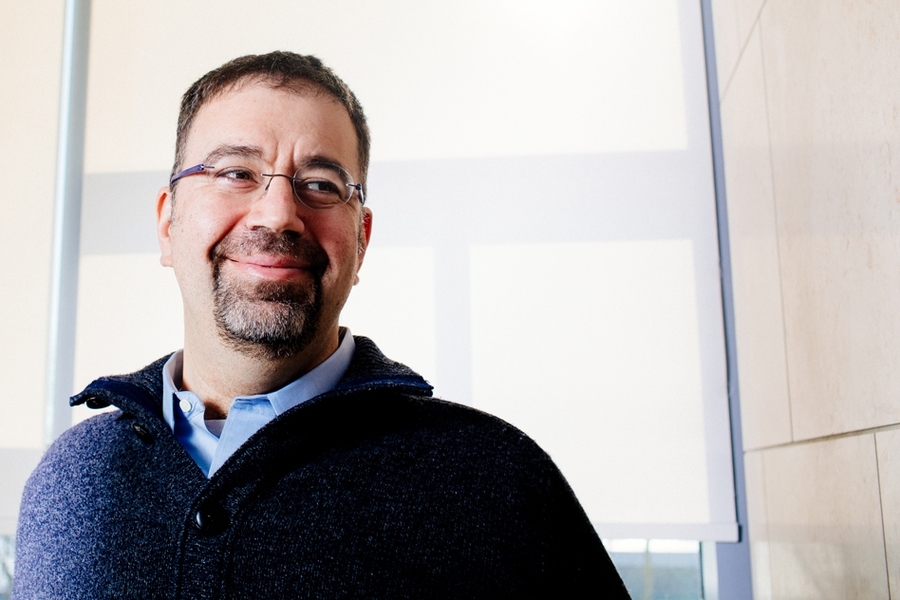

“I don’t find it surprising that it should be a big effect, because this is a big event, and nondemocracies, dictatorships, are messed up in many dimensions,” says Daron Acemoglu, an MIT economist and co-author of the new paper about the study.

Overall, Acemoglu notes, democracies employ broad-based investment, especially in health and human capital, which is lacking in authoritarian states.

“Many reforms that are growth-enhancing get rid of special favors that nondemocratic regimes have done for their cronies. Democracies are much more pro-reform,” he says.

The paper, “Democracy Does Cause Growth,” is published this month in the Journal of Political Economy . The co-authors are Acemoglu, who is the Elizabeth and James Killian Professor of Economics at MIT; Suresh Naidu, an associate professor of economics and international and public affairs at Columbia University; Pascual Restrepo, an assistant professor of economics at Boston University; and James Robinson, a political scientist and economist at the Harris School of Public Policy of the University of Chicago.

Study the “switchers”

Acemoglu and Robinson have worked together for nearly two decades on research involving the interplay of institutions, political systems, and economic growth. The current paper is one product of that research program.

To conduct the study, the researchers examined 184 countries in the period from 1960 to 2010. During that time, there were 122 democratizations of countries, as well as 71 cases in which countries moved from democracy to a nondemocratic type of government.

The study focuses precisely on cases where countries have switched forms of rule. That’s because, in part, simply evaluating growth rates in democracies and nondemocracies at any one time does not yield useful comparisons. China may have grown more rapidly than France in recent decades, Acemoglu notes, but “France is a developed economy and China started at 1/20 the income per capita of France,” among many other differences.

Instead, Acemoglu and his colleagues aimed to “ask more squarely the counterfactual question” of how a country would have done with another form of government. To properly address that, he adds, “The obvious thing to do is focus on switchers” — that is, the countries changing from one mode of government to another. By closely tracking the growth trajectories of national economies in those circumstances, the researchers arrived at their conclusion.

They also found that countries that have democratized within the last 60 years have generally done so not at random moments, but at times of economic distress. That sheds light on the growth trajectories of democracies: They start off slowly while trying to rebound from economic misery.

“Dictatorships collapse when they’re having economic problems,” Acemoglu says. “But now think about what that implies. It implies that you have a deep recession just before democratization, and you’re still going to have low GDP per capita for several years thereafter, because you’re trying to recover from this deep dive. So you’re going to see several years of low GDP during democracy.”

When that larger history is accounted for, Acemoglu says, “What we find is that [economies of democracies] slowly start picking up. So, in five or six years’ time they’re not appreciably richer than nondemocracies, but in a 10-to-15-year time horizon they become a little bit richer, and then by the end of 25 years, they are about 20 percent richer.”

Investing in people

As for the underlying mechanisms at work in the improved economies of democracies, Acemoglu notes that democratic governments tend to tax and invest more than authoritarian regimes do, particularly in medical care and education.

“Democracies … do a lot of things with their money, but two we can see are very robust are health and education,” Acemoglu says. The empirical data about those trends appear in a 2014 paper by the same four authors, “Democracy, Redistribution, and Inequality.”

For his part, Acemoglu emphasizes that the results include countries that have democratized but failed to enact much economic reform.

“That’s what’s remarkable about this result, by the way,” says Acemoglu. “There are some real basket-case democracies in our sample. … But despite that, I would say, the result is there.”

And despite the apparently sunny results of the paper, Acemoglu warns that there are no guarantees regarding a country’s political future. Democratic reforms do not help everyone in a society, and some people may prefer to let democracy wither for their own financial or political gain.

“It is possible to see this paper as an optimistic, good-news story [in which democracy] is a win-win,” says Acemoglu. “My reading is not a good-news story. … This paper is making the case that democracy is good for economic growth, but that doesn’t make it easy to sustain.”

In the study’s sample of countries, Acemoglu adds, “We have almost twice as many democratizations as reversals of democracy, but the last 10 years, that number’s going the other way around. So democracy doesn’t have a walk in the park. It’s important to understand what democracy’s benefits are and where its fault lines are. I see this as part of that effort.”

Support for the research was provided by the Bradley Foundation and the Army Research Office Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative.

Share this news article on:

Related links.

- Daron Acemoglu

- Department of Economics

Related Topics

- School of Humanities Arts and Social Sciences

- Social sciences

- Development

- Developing countries

- Political science

Related Articles

Is democracy dying?

Street signs

Three MIT scholars awarded prestigious Carnegie fellowships

State of growth

All the difference in the world

Previous item Next item

More MIT News

3 Questions: Enhancing last-mile logistics with machine learning

Read full story →

Women in STEM — A celebration of excellence and curiosity

A blueprint for making quantum computers easier to program

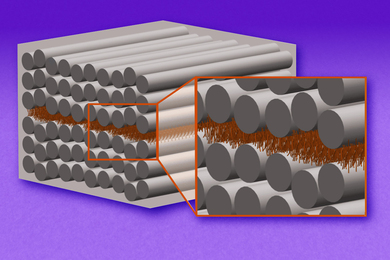

“Nanostitches” enable lighter and tougher composite materials

From neurons to learning and memory

A biomedical engineer pivots from human movement to women’s health

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

EconomicGrowth →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

New insights into the impact of financial inclusion on economic growth: A global perspective

Mohammad Naim Azimi

Faculty of Economics, Kabul University, Kabul, Afghanistan

Associated Data

The datasets for GDP growth, credit to the private sector, age dependency ratio, inflation rate, school enrollment rate, population growth rate, and trade openness (total imports of goods and services plus total exports of goods and services) are collected from the World Development Indicators that are available at ( https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators ). Datasets for the indicators of banking penetration, availability, and usage of financial services are collected from IMF’s Financial Access Survey available at ( https://data.imf.org/?sk=E5DCAB7E-A5CA-4892-A6EA-598B5463A34C ). Dataset for the rule of law is collected from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators available at ( https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/ ). All datasets are publicly available for replications by scholars.

Financial inclusion is critical to inclusive growth, proffering policy solutions to eradicate the barriers that exclude individuals from financial markets. This study explores the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth in a global perspective with a large number of panels classified by income and regional levels from 2002–2020. The analysis begins with the development of a comprehensive composite financial inclusion index comprised of penetration, availability, and usage of financial services and the estimation of heterogeneous panel data models augmented with well-known variables. The results obtained from the panel cointegration test support a long-run relationship between economic growth, financial inclusion, and the control variables in the full panel, income-level, and regional-level economies. Furthermore, the study employs a GMM (generalized method of moment) approach using System-GMM estimators to examine the effects of financial inclusion and the control predictors on economic growth. The results of the GMM model clearly indicate that financial inclusion has a significantly positive impact on economic growth across all panels, implying that financial inclusion is an effective tool in fostering rapid economic growth in the world. Finally, the study delves into the causality relationship between the predictors and provides statistical evidence of bidirectional causality between economic growth and financial inclusion, whereas it only supports unidirectional causality relationships from credit to the private sector, foreign direct investment, inflation rate, the rule of law, school enrollment ratio, and trade openness with no feedback causality. Moreover, the study fails to provide causality evidence from the age dependency ratio and population to economic growth.

1. Introduction

Financial inclusion is one of the growing research topics that has recently gained popularity in the literature and received considerable attention from scholars, academics, and policymakers alike. However, the theory of financial inclusion emerged during the 1930s (see, inter alia , [ 1 ]), but the root of a wide-ranging empirical literature dates back to the early 2000s [ 2 , 3 ]. Besides, since the spark of the millennium development goals by the United Nations, the policy orientation of the financial inclusion nexus with socioeconomic indicators, specifically economic growth, among all others, has gained prominence in the formulation and implementation of strategies for sustainable development regardless of the social and economic structure of the countries. The multi-dimensionality and non-uniformity of financial inclusion outreach [ 4 ] is assumed to foster economic growth through the gradual integration of people into a formal financial system by making financial services affordable and available at a reasonable cost, and, thus, it effects are highly pronounced vis-à-vis other growth drivers [ 5 ]. Although financial inclusion is observed as an effective instrument of social inclusion in satisfying the economic desires of poor and financially excluded individuals directly, it combats extreme poverty, reduces income inequality, and encourages human capital creativity indirectly, which, in turn, has a significant impact on the economic growth of a country. In this regard, perhaps, each jurisdiction requires contextual approaches translated into formal policy frameworks to facilitate an effective and extensive outreach of financial inclusion both for included and excluded segments of society to achieve a higher rate of economic growth in the long run [ 6 ]. However, financial inclusion-driven growth takes longer than general theoretical expectations, but the development of its policy framework must articulate three key principles: affordability and undue availability of financial services for all segments of society on the supply side; financial literacy and extensive accessibility on the demand side; and consumer protection, accountability, and institutional quality on the governance side [ 7 ].

In recognition of the importance of financial inclusion on economic growth, however, most of the recent studies have departed from the foundational theory of financial inclusion and dived either into endogenous or exogenous models. But regardless of the methodology and magnitude of the effects presented, the available empirical literature has taken three main directions. The first group of studies have examined the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth and other socioeconomic predictors in country-specific contexts with limited outcome generalizability (see, for instance, [ 8 – 14 ]). The second group of studies on financial inclusion impact has focused on specific regional classifications, such as Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), Asia’s developing economies, the One Belt One Road Initiative (OBRI), the Organization for Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) member countries (see, inter alia , [ 15 – 19 ]). The third group of empirical studies has focused either on the panels of mixed economies or developed and developing economies (see, for example, [ 20 – 25 ]).

Although an exception is given to empirical studies by Okonkwo and Ifeanyi [ 26 ] in low and middle-income countries; Van and Linh [ 27 ] in East Asia and the Pacific region; Emara and Mohieldin [ 28 ] in the Middle-East and North Africa (MENA); and Ghassibe et al. [ 29 ] in the Middle-East and Central Asia, the existing literature reports the non-existence of a comprehensive empirical study to have examined the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth from a global perspective to provide both statistical evidence on the scale of effects and comparative results by region and income-level economies to support extensive policy formulation. Therefore, it is imperative to direct the study by formulating three important questions. First, does financial inclusion have positive effects on economic growth in global, regional, and income-level economies, though some recent empirical studies provide counter-evidence? Second, are the effects of financial inclusion non-monotonic and vary across panels (global, regional, and income-level) due to economic size as represented by GDP growth? Third, are there any causality relationships between financial inclusion and economic growth with a feedback response?

The present study is an attempt to delve into the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth by controlling for major macroeconomic predictors from global, income-level, and regional-level perspectives. As an empirical fact, the literature is still evolving to understand the magnitude, extent, and direction of the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth—an emerging paradox—and the number of studies that have focused on country-specific, developed, and developing economies with mixed and even confounded results is not sufficient to support a global agenda on the subject. Moreover, the scarcity of a comprehensive empirical study highlighting the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth from a global perspective to facilitate extensive policy comparison is a significant missing gap in the literature and forms the key motivation for the present study.

The remaining sections of the study are structured as follows. Section two presents a review of literature discussing both theoretical and empirical concepts of financial inclusion and growth. Section three presents the data, variables, and construction methodology of the composite financial inclusion index. Section four develops the theoretical model of the study. Section five explains the estimation strategy of the panel data. Section six presents the results and discusses the findings. Section seven concludes the study.

2. Literature review

2.1 theoretical background.

The existing literature on the finance-growth nexus owes to Schumpeter’s [ 1 ] initial theory, stating that financial intermediaries are essential to advance technical innovations in businesses to ensure stable economic growth through saving mobilization, project evaluation, risk analysis, transaction, and money circulation conduits [ 30 ]. The theory predicts that missed opportunities are caused by inactive assets held both at personal and organizational disposal due to the absence of financial intermediaries to mobilize savings and enlarge money circulation. This, in turn, forces people to rely on wage-based savings and limits money circulation through financially profitable conduits. On the other hand, market imperfection insulates poor citizens from eluding poverty through limitation of access to formal financial products [ 15 ], whereas wider access to financial services has been excoriated as one of the most useful tactics for combating poverty, owing to the fact that higher levels of financial inclusion are linked to lower levels of income inequality and higher economic growth [ 31 ]. Since then, scholars have attempted to build various theoretical models to capture the notion of growth around the concept of Schumpeter and have provided many definitions to describe financial services (see, inter alia , [ 32 – 35 ]). Among all others, Sarma [ 36 ] has provided a comprehensive definition for the notion of financial services—that is, "financial inclusion" as a set of formal financial services to bankable individuals and the process through which such services are made available, accessible, and usable at reasonable economic cost. Thus, in line with this definition, financial inclusion can be regarded as one of the key drivers of economic growth through an increase in general consumption, higher profitable investments, a reduction in monetary overhang by the availability of financial services, and a shift from wage-based savings to return on investments [ 37 ]. Therefore, it entails two main principles that postulate the theory of financial inclusion. First, the beneficiary theory of financial inclusion, which comprises vulnerable group theory, dissatisfaction theory, and public good theory; and second, the theory of delivery of financial inclusion, comprising public money theory, echelon theory, and private money theory [ 38 ]. Thus, the latter—that is, the theory of delivery of financial inclusion—forms the theoretical direction of the present study. However, far from the basic theory of financial inclusion, almost all recent studies have considered either endogenous or exogenous growth models.

2.2 Measurement of financial inclusion

Although based on the multi-faceted theory of financial inclusion, there are numerous definitions that have a general consensus on the outreach of financial inclusion to provide excessive financial services to the bankable members of a nation, prioritizing the gradual integration of the excluded people into the formal financial system of an economy. Thus, giving rise to the conceptual importance, a comprehensive tool is essential to measure the impact of financial inclusion on various socioeconomic indicators. Despite other quasi-mechanisms (see, inter alia , [ 10 , 38 – 40 ]), this study follows Sarma [ 41 ], who enhanced the construction methodology of the composite financial inclusion index using a distance-based approach dissimilar to the human development index adopted by the United Nations Development Programs (UNDP), using average dimension indexes. A three-dimensional approach to construct the composite financial inclusion index is the banking penetration, availability, and usage of financial services, which are defined as follows.

Banking penetration—that is, access to financial services—indicates the number of users of financial services in an economy, measured by the number of deposit accounts per 1,000 adults and the number of depositors per 1,000 adults [ 41 – 43 ]. Here, the first indicator reflects the size of the bankable segment of society, while the second indicator shows the total number of banked individuals, comprising both active and non-active account holders with financial institutions [ 44 , 45 ]. Next is the availability dimension, which comprises two key indicators, such as the number of banks per 100,000 adults and the number of automated teller machines (ATMs) per 100,000 adults. It reflects the geographical availability of financial services in terms of banking outlets, bank branches, and the ATMs that are available for utilization [ 40 , 46 ]. Third is the usage dimension, which also comprises two key indicators, such as the number of loan accounts in banks per 1,000 people and the number of borrowers from banks per 1,000 adults. This dimension measures how customers use financial services in the form of transfers, remittances, borrowing, and savings to reflect the efficiency and inclusiveness of the financial services that are available to people in an economy [ 35 , 47 ].

2.3 Review of recent studies

Although the existing literature still evolves in presenting a sufficient number of empirical works on the effects of financial inclusion on various socioeconomic indicators to encourage comprehensive macroeconomic policy attempts (see, for instance, [ 48 , 49 ]), it owes its first study to Marc et al. [ 50 ], who claimed to have found statistical relationships between financial structure and economic growth. For brevity, this section reviews the most recent studies about the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth in different geographical contexts. For instance, Estrada et al. [ 51 ] examined the effects of financial systems, banks, and equity markets on economic growth in 125 developing countries. The authors have used simple methods and found that the financial system’s outreach postulates significant effects on economic growth, though the results might be confounded due to misspecification and the choice of financial inclusion predictors. Kpodar and Andrianaivo [ 52 ] evaluated the effects of information and communication technologies, mobile phone rollout, and the number of deposits per head—that is, the predictors of financial inclusion—on economic growth in a sample of African economies from 1988–2007. The authors employed the system generalized method of moment technique to overcome any endogeneity issue and found that financial inclusion is an effective tool to increase economic growth in the context of Africa.

Masoud and Hardaker [ 53 ] employed an endogenous growth model and a set of data for twelve years to examine the effects of stock market development and the banking sector on economic growth in forty-two emerging economies. The authors found that the stock market has a significant influence on the economic growth of the emerging markets and that they move together in the long run. Moreover, they argue that the banking sector is complementary to the stock market in easing customers’ access to their desired financial services. Lenka and Sharma [ 54 ] examined the effect of financial inclusion (penetration, access, and usage dimension) on economic growth in India. The authors used a set of time-series data from 1980–2014, a principal component analysis method to construct the financial inclusion index and the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) and error-correction methods to estimate the short and long-run effects of financial inclusion on growth. The authors found that financial inclusion has a positive effect on economic growth both in the short and long runs. Moreover, they also provided evidence of a unidirectional relationship between financial inclusion and economic growth.

Le et al. [ 55 ] tested the linkage between financial inclusion, growth, and other socioeconomic indicators in 20 Asian economies from 2011–2016 using a random effects model for panel data analysis. The authors found that Asian countries with a higher growth rate have higher financial inclusion to channelize higher economic growth; an inverse association between financial inclusion and unemployment rate; and the role of financial literacy in effectively utilizing the available financial services. Erlando et al. [ 56 ] examined the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth using a set of panel data for Eastern Indonesia. The authors employed the modified vector autoregressive method of Toda and Yamamoto, bivariate causality, and dynamic panel vector autoregressive methods. They found a statistically strong nexus between financial inclusion and economic growth, noticing that financial inclusion spurs economic. On the other hand, Nizam et al. [ 57 ] analyzed the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth in 63 developed and developing countries over the period from 2014–2017 using threshold regression analysis. The authors found that there is a threshold effect of financial inclusion on economic growth, implying that the effects are positive but are translated at a higher level than in the low level of the financial inclusion index.

Moreover, the existing literature indicates a counter-example about the negative effects of financial inclusion on economic growth by Rodríguez et al. [ 58 ]; who analyzed the relationships between them in 71 countries using a set of data spanning from 2007–2016; and applied ordinary least squares, the generalized method of moment with two-way fixed effects, and Granger causality methods to test their developed hypotheses. They found a negative association between financial inclusion and economic growth, highlighting that financial inclusion exerts an adverse effect on growth and a statistically significant causality nexus between them. Meanwhile, Shen et al. [ 59 ] used datasets from the WDI (World Development Indicators) and the IMF (International Monetary Funds) to examine the effects of financial inclusion index on economic growth in 105 countries. The authors used spatial data techniques to analyze the relationships between digital financial inclusion, growth, and other control variables and found that digital financial inclusion has a significantly positive impact on the economic growth of the countries.

Finally, Ozturk and Sana [ 60 ] examined the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth and environmental quality in forty-two countries linked with the One Belt One Road Initiative (OBRI) using a set of data spanning from 2007–2019. The authors employed pooled ordinary least squares (OLS), two-stage OLS, and the generalized method of moment (GMM) models. They found that financial inclusion has a positive impact on economic growth but has negative effects on environmental quality through the flow of CO2 emissions.

The purview of the existing literature reveals that the empirical studies conducted to examine the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth have left two significant gaps. First, it reports no comprehensive study to reflect the impact of financial inclusion on growth from a global perspective and no comparative results for cross-country groupings by income and regional levels using unified analytical methodology to highlight comprehensive policy implications to support the literal arguments of the paradigm shift—that is, a shift from financial development to financial inclusion as a global agenda. Second, the mixed and confounded results presented by the existing literature have enhanced the paradox of the effects of financial inclusion as a driver of growth. Therefore, to fill these gaps, it is important to formulate three key hypotheses. H 1 : As claimed by the initial concept, financial inclusion has a positive impact on economic growth regardless of economic size and structure across the globe. H 2 : Though the effects are positive on growth, they are non-monotonic and specified by the size of the economies, viz-à-viz, the GDP. H 3 : While financial inclusion explains economic growth, it is strongly affected by the growth rate of an economy—that is, there is a bidirectional link between them.

3. Data and variables

The datasets contain 218 countries across the world, employing annual observations spanning from 2004–2021 compiled from reliable sources and are organized by various panels reflecting income and regional level economies reported by the World Bank classification report [ 61 ]. The variables used are consistent with recent empirical literature and include GDP growth, the composite financial inclusion index, school enrollment rate, age dependency ratio, credit to the private sector, the rule of law, inflation rate, trade openness, the Gini index, and population growth rate. Table 1 provides complete information about them. The study employs GDP growth as the dependent variable proxied for economic growth and the composite financial inclusion index as the independent and key variable of interest. However, the construction method of the composite financial inclusion index (CFII) is discussed later; the present study controls for several macroeconomic predictors to avoid any omitted variable bias. Thus, the school enrollment ratio (SER) is used as a proxy for human capital development. Intuitively, an increase in school enrollment increases skills, knowledge, and creativity, thereby stimulating economic growth. Moreover, the age dependency ratio is used to control its effects on growth. Theory predicts that either too young or too old citizens would be cost-burdensome and negatively impact the growth. Credit to the private sector may also influence economic progression, viz-à-viz greater access to credit facilitates higher capital investment, thus spurring economic growth. Studies by Le et al. [ 55 ], Sayed and Shusha [ 43 ], and Rashdan and Eissa [ 45 ] suggest including the inflation rate as a control variable when delving into the effects of CFII on growth. It is important to understand the effects of higher inflationary episodes that cause the saving rates to decrease and suppress the citizens’ use of desired financial services. In light of the globalized economy, it is essential to augment the trade openness in the model to measures the cross-country access of financial services by traders. Despite controlling for the income inequality proxied by Gini index, the study also controls for the effects of institutional quality proxied by the rule of law. It is widely documented that the rule of law is an appropriate proxy for institutional quality when analyzing the effects of CFII on growth [ 62 ]. Finally, population growth rate is also used to control its effects on economic growth.

Notes: The Gini index compiled from SWIID is constructed by Solt [ 63 ]. WDI = World Development Indicators, FAS = Financial Access Survey, WGI = Worldwide Governance Indicators, SWIID = Standard World Income Inequality Database.

Unlike recent empirical studies that followed the construction methodology of the composite index explained by UNDP for HDI (Human Development Index), the present article adopts a more comprehensive method proposed by Sarma [ 41 ] to construct the CFII. Literally, financial inclusion outreach is based on three key dimensions, such as banking penetration, the availability, and the usage of financial services by the bankable population. To quantify, each dimension comprises two key indicators, and thereby, each indicator is assigned an appropriate numerical weight (see Table A1 of Appendix A in S1 Appendix ). The construction begins with the specification of dimension index observing minimum and maximum integers using d i = w i ( A ik , t − m i / M i − m i ), in which, d , w i , A i , m i , and M i present the normalized integer, weight, actual value of the country k in time t , lower limit (fixed by value 0), and upper limit (fixed by 90 th percentile rank) of the dimension i , respectively [ 64 ]. Considering this, the CFII is estimated using the notions of distance ( d ) achievements of points ( d 1 , d 2 , d 3 ,…, d n ) from ( O = 0, 0, 0,…, 0) being the worst point and from ( W = w 1 , w 2 , w 3 ,…, w n ) being an ideal point as:

where Eq (1) is used to estimate the normalized Euclidian distance between the achievement point ( x ) and worst position ( O ) on the n th space [ 65 ]. Then, to estimate the normalized inverse distance between ( x ) and ideal position ( W ) on the n th space, the following equation is employed:

Finally, to estimate the CFII, the average of Eqs ( 1 ) and ( 2 ) are taken as:

This method of CFII construction is widely used in financial econometrics as a standardized predictor of comprehensive financial inclusion index (see, for instance, [ 43 , 46 , 66 ]).

4. Model specification

To obtain specification for delving into the effects of composite financial inclusion index on economic growth, this study draws on Kim et al. [ 15 ] and Andiansyah [ 67 ] and begins with a long-run panel specification as:

where φ = intercept, η 1 − η 9 = long-run panel coefficients, t = 1, 2, …, = T , i = 1, 2, …, = N , u = error term of the model following identically and independently normal distribution ( i . i . n . d .) assumption, and all other variables hold the same meaning as explained before. Except for the rule of law, which is augmented to control for institutional quality on growth, the choice of other explanatory variables is based on recent empirical studies (see, inter alia , [ 27 , 67 – 70 ]). Moreover, it is expected that the signs of η 1 , η 2 , η 4 , and η 7 > 0, the signs of η 3 , η 6 , and η 9 < 0 and the sign of η 5 to be a-priori indeterminate; that is, based on the advancement of institutional quality in high-income and upper middle-income economies, it may show positive effects on growth, whilst a negative sign is expected in low-income economies due to deteriorating institutional quality.

5. Econometric methods

5.1 cointegration test.

From the reviewed literature and recent empirical studies on applied panel data techniques, the present study avoids testing the unit root of the predictors, considering the empirical fact that the number of units is greater than the observations in a panel [ 71 – 74 ]. Therefore, it dives into testing for the panel cointegration to establish the long-run nexus amid indicators. For the rejected null of cross-sectional independence in the panel, the use of common panel cointegration tests such as Kao [ 75 ] and Pedroni [ 76 ] may lead to biased results. Thus, the study employs the panel LM (Lagrange Multiplier) bootstrap cointegration test proposed by Westerlund and Edgerton [ 77 ], which allows for cross-sectional dependence and produces accurate results in small samples. It follows the same principal component analysis explained by Westerlund [ 78 ] and is initiated as:

where t = 1,…, T , i = 1, …, N and x it = x it −1 + v it exhibiting I(1) series presenting the K-dimensional regressor vector, D it presents the break dummy, F ^ t is the common factor, and λ ^ i is the factor loading for principal component analysis. Therefore, with the help of Eq (6) given below, the panel LM test statistics is computed as:

where φ , the change sign Δ, and ε are the intercept, first difference operator, and the error term of the model, respectively. Using the LM bootstrap, the null hypothesis indicates panel cointegration, given that the bootstrap ( p > 0.05) for the LM test statistics against its alternative of no cointegration for all cross-sections.

5.2 GMM approach

To estimate Eq (4) , and considering the properties of the panel data used in this study, whether cointegrated or not, it employs the generalized method of moment (GMM), which is an appropriate econometric approach suitable for the case of this study. The choice of using the GMM technique is based on empirical facts—the existence of cross-sectional dependence among country groupings, panel endogeneity, and the low frequency of observations compared to the number of units in the panel, say, T < N [ 79 ]. For brevity, considering a linear regression with endogenous regressors, this study initiates building the GMM model as:

where y it = the dependent variable, say, economic growth; u it = N × 1 vectors, ϑ = K × 1 vector for the unknown parameters, x it = N × K matrix for the explanatory variables, and u it is the error term of the model. Assuming that there is an endogeneity issue in the panel, it considers a matrix x it with N × L given that L > K , where z it matrix comprises a set of predictors that are strongly correlated with x it but have orthogonality with u it , say, they are not highly correlated with the error term. Thus, z it is assumed to be exogeneous following E ( z i t ′ u i t ) = 0 assumption [ 80 ]. For GMM estimation, there are two approaches, such as System GMM (Sys-GMM) and Difference GMM (Diff-GMM). For the Sys-GMM, the employed equation takes the following form:

where ln = natural log of the predictors, φ = coefficient of the lagged dependent variable, and ϑ = coefficient of the lagged explanatory variables, and other vector predictors hold the same meaning as explained before. Eq (8) is a level equation comprising fixed effects, while Diff-GMM transforms the predictors by first differencing to remove the fixed effects as:

where Δ u it = Δ η i + Δ ε it , say, u it − u it −1 = ( η i − η i ) + (Δ ε it − Δ ε it −1 ), and other variables hold the same meaning as explained before. Now, Eq (9) removes the fixed effects and does not vary along with the time, but the problem of panel endogeneity still remains. Moreover, Δ ln y it , which is the first-differenced lagged dependent variable is instrumented with its lagged value and its changes are shown by Eq (9) . According to Blundell and Bond [ 80 ], if the dependent variable is a random walk process, Eq (9) may produce biased and inconsistent estimate of φ in finite samples, especially when the time period is short, which is attributed to poor instruments in the model. To that end, preference is given to Sys-GMM estimation as it simultaneously computes two equations. One with a level, and the instruments in first differenced form. Second, with the first difference, the instruments are expressed in the level form. This method includes more moment conditions when the time period is short and the dependent variable is assumed to be a random walk. Therefore, it gains precision and small sample distortion is reduced. The Sys-GMM estimation is based on two approaches, such as 1Sys-GMM (one step system GMM) and 2Sys-GMM (two step system GMM), where the former assumes no heteroskedasticity and serial correlation and the latter corrects them by exploiting a weighting matrix based on the residuals from the 1Sys-GMM.

Moreover, GMM estimation has several empirical advantages over the common techniques for panel data analysis. First, it controls for omitted variable bias, correlation between the variables, and any potential measurement errors. Second, it produces consistent and accurate results of the coefficients for panel samples with N > T. Third, it corrects the unobserved endogeneity by transforming the regressors through differencing and removing the fixed effects. Fourth, in terms of heteroskedasticity and serial correlation, the Sys-GMM, which is an augmentation of the Diff-GMM, is more consistent, robust, and efficient.

As suggested by the existing literature, in this study, the analysis begins with the estimation of Eq (4) by pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) and the least squares dummy variable (LSDV) using fixed effects methods. Doing so leads the study to select an appropriate GMM estimator and avoid misspecification. Therefore, the pooled OLS panel estimate for φ is used as an upper bound, while the fixed effect estimates are used as the lower bounds. If the Diff-GMM estimates are close to or below the fixed effects estimates, Sys-GMM is more consistent and efficient as Diff-GMM would be biased due to weak instrumentation. Moreover, it is also important to test for instruments validity, for which Hansen’s [ 81 ] J-statistics and Sargan’s [ 82 ] methods are employed to test the validity of the instrumental variables augmented in the GMM model. Rejecting the null hypothesis implies that the instruments are invalid [ 83 ], while failing to reject the null implies otherwise. Furthermore, this study tests the null of no second-order serial correlation in the error term using the Arellano and Bond [ 79 ] method. Failing to reject the null implies that no second-order serial correlation exists and that the moment conditions are appropriately specified.

5.3 Panel causality test

Finally, this study delves into the causal relationships between economic growth and the composite financial inclusion and employs the proposed model of Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 84 ] causality test for heterogeneous panel. This test is suitable for the panels that exhibit cross-sectional dependence and when T < N, as in this case. Thus, it provides more consistent results than other common methods. The equation used to test the causality between the predictors is expressed as:

where α , λ , β , and ε are the intercept, the coefficient for the lagged dependent variable, the coefficient for the lagged independent variable, and the error term of the model, respectively. Eq (10) tests the null of no causality between the predictors in the cross-sections, using individual Wald statistics for each unit and averaged Wald statistics for the whole panel (see [ 84 ], for technical details).

6. Results and discussion

6.1 descriptive statistics.

The analysis begins with some important summary statistics about the variables, reported in Table B1 of Appendix B in S2 Appendix . It shows that the mean value for GDP growth is 2.74% for the full panel, while it is 2%, 4.48%, 5.69%, 6.13%, 1.52%, 1.11%, 4.91%, 1.41%, 2.12%, 3.87%, 1.78%, 5.71%, and 3.99% for low-income, middle-income, upper middle-income, high-income, OECD, non-OECD, East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and Caribbean, MENA, North America, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan African economies, respectively. On the other hand, the summary statistics indicate that the mean value for the composite financial inclusion index is 0.26, 0.78, 0.73, 0.69, 0.71, 0.82, 0.74, 0.71, 0.73, 0.68, 0.74, 0.79, 0.68, and 0.72 for the full panel, low-income, middle-income, upper middle-income, high-income, OECD, non-OECD, East Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and Caribbean, MENA, North America, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan African economies, respectively. It reveals that among all others, although the growth rate of the high-income countries has been the highest throughout the period, their CFII rank has relatively been lower than those of the low-income, middle-income, upper middle-income, OECD, MENA, North America, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan African countries. Moreover, another interesting indicator is the rule of law, which shows that its mean value does not necessarily correspond to the growth rate and the mean value of the financial inclusion outreach. For instance, the mean value of the rule of law is 90.33 percentile rank for high-income economies, which is the highest among all others, while its growth rate and CFII average rate are reported otherwise. For brevity, one can read through the variations among the predictors, but the study proceeds to delve into the cointegration among them.

6.2 Cointegration analysis

To ascertain the long-run nexus amid predictors, the Westerlund and Edgerton [ 77 ] cointegration test by LM bootstraps was computed, and the results are shown in Table 2 . For the rejected null hypothesis of no cointegration, except for the low-income economies, the findings reveal that there exists significant cointegration among the predictors in all panels. This implies that panel predictors move together in the long run—that is, the composite financial inclusion index, which is the key variable of interest, and other explanatory variables postulate significant effects on economic growth and cannot be deviated from long-run equilibrium. The results are consistent with the findings of Nwanne [ 85 ], Hassan [ 86 ], Ratnawati [ 87 ], and Ain et al. [ 88 ], who also established statistical long-run relationships between financial inclusion and economic growth. Moreover, the results satisfy the underlying theory of growth-financial inclusion [ 14 ], implying that excessive financial inclusion outreach facilitates higher capital mobility and integration of a higher proportion of unbanked individuals into the formal financial system, which leads to higher economic growth in the long run.

***, **, and * indicate significance at 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. () indicates Z-values. The corresponding p-values are robust and are performed under 100 bootstraps replications.

6.3 GMM estimates

As for the key results of interest, Tables Tables3 3 and and4 4 report the results of robust GMM estimation—that is, 1Sys-GMM, 2Sys-GMM, and Diff-GMM for the full panel, income level groupings, and regional economies. As discussed earlier, using empirical diagnostics, the Sys-GMM estimators are preferred over the Diff-GMM, and thus, the interpretation of the results and discussion of findings are based on the 2Sys-GMM results, though the results of the 1Sys-GMM are similar to those of the 2Sys-GMM. For robustness, it follows the Windmeijer [ 89 ] correction in the standard errors of the 2Sys-GMM estimation to control for the downward biasedness of standard errors, controlling the instrument matrix, observation weight, the difference-in-Sargan/Hansen test of instrument validity, and the forward orthogonal transform, which is an alternative to the differencing approach of Arellano and Bover [ 90 ], preserving sample size in panels with observational gaps.

***, **, and * indicate significance at 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. [] indicates test statistics.

For simplicity and use of limited space, the results of the pooled OLS and LSDV fixed effects models are omitted from the present study and will be available upon request. Moreover, to simplify reading through the results and to highlight significant findings, the study reports the results by income and regional classifications as shown in Tables Tables3 3 and and4 4 .

6.3.1 Full panel

The results of the full panel, thereby the world panel, reflect the overall effects of financial inclusion—a key variable of interest—and other explanatory predictors on economic growth, consisting of (218) countries. The results indicate that financial inclusion proxied by CFII (composite financial inclusion index) has a significantly positive impact on the world’s economic growth, implying that one percent increase in financial inclusion (penetration, availability, and usage of financial services) increases the world’s economic growth by 0.316%, ceteris-paribus. The results are consistent with the theoretical expectations about the positive growth-financial inclusion nexus and empirical findings of Kim et al. [ 15 ] for 55 member countries of the OIC (Organization of Islamic Cooperation), Siddik et al. [ 19 ] for 24 Asian developing economies, Singh and Stakic [ 18 ] for 8 SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) member countries, and Huang et al. [ 17 ] for 27 countries of the European Union. Though, for brevity, other explanatory variables, such as age dependency ratio (–), inflation rate (–), foreign direct investment (+), school enrollment ratio (+), trade openness (+), and population growth (–) have their varying expected effects on economic growth, the rule of law, which is augmented in the model to ascertain its mediating effects on growth, shows that institutional quality is significant to ease the impact of financial inclusion on growth. For instance, the results demonstrate that a 1% increase in the percentile rank of the rule of law causes economic growth to increase by 0.321% in a global context. This is supported by recent empirical findings by Valeriani and Peluso [ 91 ], Nguyen et al. [ 68 ], Salman et al. [ 12 ], and Radulović [ 92 ], who also documented the effects of institutional quality on economic growth. Furthermore, an economic intuition suggests that higher institutional quality—that is, comprehensive rule of law—facilitates indirect economic growth through various conduits, one of which is financial inclusion outreach.

Moreover, the control variables, such as age dependency ratio, inflation rate, and population growth rate, decrease economic growth by 0.024%, 0.010%, and 0.081%, respectively. The negativity of the age dependency ratio implies the reduction of productivity in the world and a declining long-run trend in growth, whilst the negativity of the inflation rate on growth may additionally cause excessive cost-burden for bankable customers and reduce the scope of financial inclusion. Although some recent studies found that population growth has a positive impact on the economy, the current study finds that a 1% increase in population growth rate reduces economic growth by 0.081%. This is consistent with the findings of Easterlin [ 93 ], Klasen [ 11 ], and Mason and Lee [ 94 ] on the combined population projected effects on lowering economic growth by 1 percentage point per year.

6.3.2 Income-level

However, the results are statistically significant for all income-level economies, but they reveal that for low-income countries, financial inclusion has a positive impact and increases economic growth by 0.085%, while comparatively, it increases the economic growth of middle-income, upper middle-income, high-income, OECD, and non-OECD member countries by 0.119%, 0.212%, 0.419%, 0.405%, and 0.146%, respectively. This highlights an important variation in the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth, varying with respect to the income level of the countries. Considering the rule of law as a proxy for institutional quality, the results indicate that its effect also varies across income-level groupings. It shows that, ceteris paribus, one percentile rank increase in the rule of law causes economic growth by 0.112%, 0.348%, 0.417%, 0.537%, 0.642%, 0.240% in low-income, middle-income, upper middle-income, high-income, OECD, and non-OECD countries, respectively. Thus, the variation of the effects of financial inclusion may be due to two key reasons: the economic size of the countries and the implementation of the rule of law in governing, allocating, and using financial resources for the sake of rapid growth. Consistently, Azimi [ 95 ] also clearly shows that the non-monotonic effects of the rule of law are based on the varying economic size of the country. The findings indicate that the higher the income level, the greater the impact of financial inclusion on economic growth will be. Furthermore, the results show that the theoretically expected effects of the control variables, such as age dependency ratio (–), credit to the private sector (+), foreign direct investment (+), inflation rate (–), school enrollment rate (+), trade openness (+), and population growth rate (–) on the economic growth of the income-level grouping are achieved. Not surprisingly, the impact of the control variables on growth is also found to be non-monotonic.

For instance, the credit to the private sector has a significantly positive effects on growth, showing that a 1% increase in credit to the private sector, the economic growth increases by 0.130%, 0.322%, 0.332%, 0.348% in low-income, middle-income, upper middle-income, and high-income economies, respectively. Olowofeso et al. [ 24 ], Cuong [ 23 ], and Samuel-Hope et al. [ 22 ] also found statistical evidence of the positive effects of credit to the private sector on economic growth in various economic contexts. On the other hand, foreign direct investment also posits positive effects on growth. Its effect on growth is 0.514%, 0.438%, 0.502%, 0.612%, 0.441%, and 0.604% for low-income, middle-income, upper middle-income, high-income, OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), and non-OECD member countries, respectively. Moreover, the negative association between the inflation rate and the age dependency ratio is lower in high-income but higher in low-income economies. For example, the negative effect of the inflation rate on growth is -0.382% in low-income countries, while it is -0.118%, -0.218%, and -0.117% in middle-income, upper middle-income, and high-income countries, respectively. Studies by Babajide et al. [ 96 ]; Lenka and Sharma [ 97 ]; Dahiya and Kumar [ 13 ]; and Okonkwo and Ifeanyi [ 26 ] also provide statistical evidence of the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth in low and middle-income countries. Consistently, Sethi and Acharya [ 21 ] found a significant association between growth and financial inclusion in 31 countries across the world, consisting of low, middle, and high-income economies, while Li et al. [ 20 ] extended the statistical findings of the effects of financial inclusion in OECD member countries, supporting the findings of the present study.

6.3.3 Regional-level

To facilitate better analysis and deeper insights into the effects of financial inclusion on economic growth, the present study delves into the matter using the regional classification of the countries. Comparatively, the results provide much deeper views of the growth-financial inclusion association in regional contexts. The results demonstrate that financial inclusion, which is the key variable of interest, is statistically significant at 1% level and spurs economic growth by 0.218% in East Asia and the Pacific, 0.209% in Europe and Central Asia, 0.408% in Latin America and the Caribbean, 0.501% in MENA, 0.256% in North America, 0.783% in South Asia, and 0.642% in Sub-Saharan African countries. Comparatively, the results indicate that South Asia’s growth has the highest reaction to financial inclusion among all others, while Europe and Central Asia’s growth rate has the lowest response to financial inclusion. The results are consistent with the findings of Van and Linh [ 27 ] in East Asia and the Pacific and Abdul Karim et al. [ 25 ] in sixty developed and developing economies, Adalessossi and Kaya [ 98 ] and Wokabi and Fatoki [ 99 ] in African countries, Thathsarani et al. [ 2 ] in eight South Asian countries, Gakpa [ 100 ] and Adedokun and Ağa [ 16 ] in Sub-Saharan African countries, Emara and Mohieldin [ 28 ] in MENA, and Ghassibe et al. [ 29 ] in the Middle-East and Central Asia, who also found that financial inclusion is a significant determinant of economic growth and an effective tool to facilitate greater financial integration. From a macroeconomic standpoint, increasing unbanked individuals’ access to financial services leads to increased money circulation and credit exchange in the economy, resulting in a significant impact on stable economic growth [ 101 ], whereas integrating unbanked individuals into the formal financial system results in a meaningful reduction in tax avoidance, money laundering, and transaction costs [ 57 ]. However, the proportional impact of financial inclusion is relatively lower than that of financial deepening, but it continues to encourage more unbanked populations to join the formal financial system to generate higher impacts on economic growth. For instance, in East Asia and the Pacific, the results indicate that financial inclusion significantly increases economic growth by 0.218%, while other predictors, such as credit to the private sector, foreign direct investment, the rule of law, school enrollment rate, and trade openness, also exert positive effects on growth by 1.378%, 0.783%, 0.321%, 1.032%, and 1.016%, respectively. A quick intra-comparison shows that financial deepening, human capital, and economic openness—that is, credit to the private sector, school enrollment ratio, and trade, respectively—have much higher effects on growth than financial inclusion in East Asia and the Pacific. The same results apply to all regional economies, except for South Asian countries that exhibit a different scale but similar magnitude. It is found that, in South Asia, a 1% increase in financial inclusion significantly causes economic growth to increase by 0.783%. With respect to both the inter-region and intra-region comparisons, the effects of financial inclusion on growth are higher than in other regional and income-level economies. This could be due to obvious factors such as significant advancements and support for financial inclusion in South Asia’s three most populous countries, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, which are constantly expanding the reach of their financial inclusion services. This finding is also supported by Thathsarani et al. [ 2 ] in eight South Asian economies, who found that the comparative effects of financial inclusion are lower than other financial development predictors on growth, and by Park and Mercado [ 102 ] in thirty-three developing economies, who provided similar findings on the comparative effects of financial inclusion on economic growth. For the control variables, the results indicate that age dependency ratio, inflation rate, and population growth are statistically significant and posit negative impacts on the economic growth of the regional economies, while credit to the private sector, foreign direct investment, school enrollment rate, and trade openness have positive associations with economic growth. Moreover, the results also show that institutional quality proxied by the rule of law has a significantly positive impact on economic growth, whereas, as theory suggests, higher institutional quality leads to efficient and effective delivery of financial services and thus paves the way for swift economic growth. The results reported in Tables Tables3 3 and and4 4 are statistically robust. The diagnostic checks of the relevant tests are reported at the rear part of the tables.

6.4 Causality nexus

Finally, the present study computes the panel causality test of Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 84 ] and reports the results in Table 5 , highlighting interesting results. They reveal that there is a significant bidirectional causality relationship between economic growth and financial inclusion at a 1% level in the full panel, income-level panels, and regional panels. Since feedback responses—that is, reverse causality statistics of the control variables—have not been significant, they are not reported in Table 5 . The results indicate that except for the age dependency ratio (ADR) and population growth rate (PGR), which are insignificant in causing economic growth in the full and all other classified panels, the rest of the variables, such as credit to the private sector, foreign direct investment, inflation rate, the rule of law, school enrollment ratio, and trade openness, are significant enough to exhibit unidirectional causality to cause economic growth. The results support the findings of Sharma [ 103 ], Mlachila et al. [ 104 ], Sethi and Acharya [ 21 ] in a panel of both developed and developing countries, and Gourène and Mendy [ 105 ] in the West African Economic and Monetary Union, who also found directional causality relationships between financial inclusion and economic growth in different economic contexts. The results are in contrast with those of Asmalidar and Pratomo [ 106 ], who claimed that there is no causality nexus amid financial inclusion and economic growth.

***, **, and * indicate significance at 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. = >/ indicates the null of no panel causality relationship. [] indicates p-values .

7. Conclusion