Peer Review

- Animal Subjects

- Biosecurity

- Collaboration

- Conflicts of Interest

- Data Management

- Human Subjects

- Publication

- Research Misconduct

- Social Responsibility

- Stem Cell Research

- Whistleblowing

- Regulations and Guidelines

- The integrity of science depends on effective peer review A published paper reflects not only on the authors of that paper, but also on the community of scientists. Without the judgment of knowledgeable peers as a standard for the quality of science, it would not be possible to differentiate what is and is not credible.

- Effective peer review depends on competent and responsible reviewers The privilege of being part of the research community implies a responsibility to share in the task of reviewing the work of peers.

For much of the last century, peer review has been the principal mechanism by which the quality of research is judged. In general, the most respected research findings are those that are known to have faced peer review. Most funding decisions in science are based on peer review. Academic advancement is generally based on success in publishing peer-reviewed research and being awarded funding based on peer review; further, it involves direct peer review of the candidate's academic career. In short, research and researchers are judged primarily by peers.

The peer-review process is based on the notion that, because much of academic inquiry is relatively specialized, peers with similar expertise are in the best position to judge one another's work. This mechanism was largely designed to evaluate the relative quality of research. However, with appropriate feedback, it can also be a valuable tool to improve a manuscript, a grant application, or the focus of an academic career. Despite these advantages, the process of peer review is hampered by both perceived and real limitations.

Critics of peer review worry that reviewers may be biased in favor of well-known researchers, or researchers at prestigious institutions, that reviewers may review the work of their competitors unfairly, that reviewers may not be qualified to provide an authoritative review, and even that reviewers will take advantage of ideas in unpublished manuscripts and grant proposals that they review. Many attempts have been made to examine these assumptions about the peer review process. Most have found such problems to be, at worst, infrequent (e.g., Abby et al., 1994; Garfunkel et al., 1994; Godlee et al., 1998; Justice et al., 1998; van Rooyen et al., 1998; Ward and Donnelly, 1998). Nonetheless, problems do occur.

Because the process of peer review is highly subjective, it is possible that some people will abuse their privileged position and act based on unconscious bias. For example, reviewers may be less likely to criticize work that is consistent with their own perceptions (Ernst and Resch, 1994) or to award a fellowship to a woman rather than a man (Wennerds and Wold, 1997). It is also important to keep in mind that peer review does not do well either at detecting innovative research or filtering out fraudulent, plagiarized, or redundant publications (reviewed by Godlee, 2000).

Despite its flaws, peer review does work to improve the quality of research. Considering the possible failings of peer review, the potential for bias and abuse, how can the process be managed so as to minimize problems while maintaining the advantages?

Most organizations reviewing research have specific guidelines regarding confidentiality and conflicts of interest. In addition, many organizations and institutions have guidelines dealing explicitly with the responsibilities of peer reviewers, such as those of the American Chemical Society (2006), the Society for Neuroscience (1998, and the Council of Biology Editors (CBE Peer Review Retreat Consensus Group, 1995).And, though currently suspended, there had been a federal requirement that made discussion of peer review part of instruction in the responsible conduct of research (Office of Research Integrity, 2000).

Peer review is governed by federal regulations in two respects. First, federal misconduct regulations can be invoked if a reviewer seriously abuses the review process, and second, peer review for the grant process prohibits review by individuals with conflicts of interest.

Despite these regulations, much of peer review is not directly regulated. It is governed instead by guidelines and custom.

Case Studies

Discussion questions.

- Based on your own experience, or on discussion with someone who is an experienced reviewer, which of the following are common practice? Which of the following should not be acceptable practice? a. The reviewer is not competent to perform a review, but does so anyway. b. Reviewer bias results in a negative review that is misleading or untruthful. c. The reviewer delays the review or provides an unfairly critical review for the purpose of personal advantage. d. The reviewer and his or her research group take advantage of privileged information to redirect research efforts. e. The reviewer shares review material with others (for the purpose of training or scientific discussion) without notifying or obtaining approval from the editor or funding agency.

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of having a reviewer blinded to the identity of manuscript authors, a grant applicant, or a candidate for academic advancement?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of having manuscript authors, a grant applicant, or a candidate for academic advancement blinded to the identity of a reviewer?

- What are the ethical responsibilities of peer reviewers?

- List and describe federal regulations relevant to peer review.

- Should reviewers working in the same field of research be excluded from reviewing each others' work? How can the risks of bias and the advantages of expertise be reconciled in the selection of peer reviewers?

- What are the responsibilities of a reviewer to preserve the confidentiality of work under review? What protections, if any, help to prevent the loss of confidentiality?

Additional Considerations

The purpose of peer review is not merely to evaluate the submitted work, but also to promote better work within the scientific community. As such, there are several essential responsibilities for peer reviews.

- Provide a timely response Reviewers should make every effort to complete a review in the time requested. If it is not possible to meet the conditions for the review, then the reviewer should promptly decline or see if some accommodation is possible. Research reports, grant applications, and academic files submitted for review all represent a significant investment of time and effort, and frequently the documents under review contain timely results that will suffer if delayed in the review process.

- Ensure Competence Reviewers who realize that their expertise is limited have a responsibility to make their degree of competence clear to the editor, funding agency, or academic institution asking for their expert opinion. A reviewer who does not have the requisite expertise is at risk of approving a submission that has substantial deficiencies or rejecting one that is meritorious. Such errors are a waste of resources and hamper the scientific enterprise.

- Avoid Bias Reviewers' comments and conclusions should be based on a consideration of the facts, exclusive of personal or professional bias. To the extent possible, the system of review should be designed to minimize actual or perceived bias on the reviewers' part. If reviewers have any interest that might interfere with an objective review, then they should either decline a role as reviewer or declare the conflict of interest to the editor, funding agency, or academic institution and ask how best to manage the conflict.

- Maintain Confidentiality Material submitted for peer review is a privileged communication that should be treated in confidence. Material under review should not be shared or discussed with anyone outside the designated review process unless approved by the editor, funding agency, or academic institution. Authors, grant applicants, and candidates for academic review have a right to expect that the review process will remain confidential. Reviewers unsure about policies for enlisting the help of others should ask.

- Avoid unfair advantage A reviewer should not take advantage of material available through the privileged communication of peer review. One exception is that if a reviewers becomes aware on the basis of work under review that a line of her or his own research is likely to be unprofitable or a waste of resources, then they may ethically discontinue that work (American Chemical Society, 2006; Society for Neuroscience, 1998. In such cases, the circumstances should be communicated to those who requested the review. Beyond this exception, every effort should be made to avoid even the appearance of taking advantage of information obtained through the review process. Potential reviewers concerned that their participation would be a substantial conflict of interest should decline the request to review.

- Offer constructive criticism Reviewers' comments should acknowledge positive aspects of the material under review, assess negative aspects constructively, and indicate clearly the improvements needed. The purpose of peer review is not to demonstrate the reviewer's proficiency in identifying flaws, but to help the authors or candidates identify and resolve weaknesses in their work.

- Abby M, Massey MD, Galandiuk S, Polk HC (1994): Peer review is an effective screening process to evaluate medical manuscripts. JAMA 272: 105-107.

- American Chemical Society (2006): Ethical guidelines to publication of chemical research. ACS Publications http://pubs.acs.org/userimages/ContentEditor/1218054468605/ethics.pdf

- CBE Peer Review Retreat Consensus Group (1995): Peer review guidelines - A working draft. CBE Views 18(5): 79-81.

- Ernst E, Resch KL (1994): Reviewer bias: a blinded experimental study. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine 124(2): 178-82.

- Garfunkel JM, Ulshen MH, Hamrick HJ, Lawson EE (1994): Effect of institutional prestige on reviewers' recommendations and editorial decisions. JAMA 272: 137-138.

- Godlee F, Gale CR, Martyn CN (1998): Effect on the quality of peer review of blinding reviewers and asking them to sign their reports. JAMA 280: 237-240.

- Godlee F (2000): The ethics of peer review. In (Jones AH, McLellan F, eds.): Ethical Issues in Biomedical Publication. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, pp. 59-84.

- Justice AC, Cho MK, Winker MA, Berlin JA, Rennie D, PEER Investigators (1998): Does masking author identity improve peer review quality? JAMA 280: 240-242.

- Office of Research Integrity (2000): PHS Policy on Instruction in RCR. http://ori.hhs.gov/policies/RCR_Policy.shtml

- Society for Neuroscience (1998): Responsible Conduct Regarding Scientific Communication. http://www.sfn.org/skins/main/pdf/Guidelines/ResponsibleConduct.pdf

- van Rooyen S, Godlee F, Evans S, Smith R, Black N (1998): Effect of blinding and unmasking on the quality of peer review. JAMA 280: 234-237.

- Wennerds C, Wold A (1997): Nepotism and sexism in peer review . Nature 307: 341.

- Terms of Use

- Site Feedback

- Open access

- Published: 18 August 2017

Improving the process of research ethics review

- Stacey A. Page ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6494-3671 1 , 2 &

- Jeffrey Nyeboer 3

Research Integrity and Peer Review volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

31 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

Research Ethics Boards, or Institutional Review Boards, protect the safety and welfare of human research participants. These bodies are responsible for providing an independent evaluation of proposed research studies, ultimately ensuring that the research does not proceed unless standards and regulations are met.

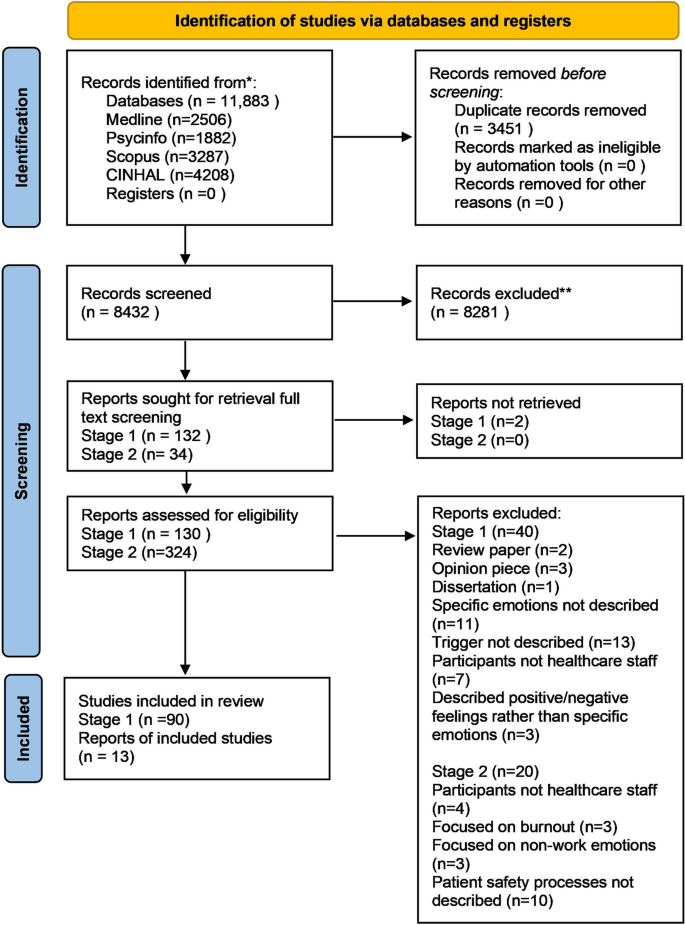

Concurrent with the growing volume of human participant research, the workload and responsibilities of Research Ethics Boards (REBs) have continued to increase. Dissatisfaction with the review process, particularly the time interval from submission to decision, is common within the research community, but there has been little systematic effort to examine REB processes that may contribute to inefficiencies. We offer a model illustrating REB workflow, stakeholders, and accountabilities.

Better understanding of the components of the research ethics review will allow performance targets to be set, problems identified, and solutions developed, ultimately improving the process.

Peer Review reports

Instances of research misconduct and abuse of research participants have established the need for research ethics oversight to protect the rights and welfare of study participants and the integrity of the research enterprise [ 1 , 2 ]. In response to such egregious events, national and international regulations have emerged that are intended to protect research participants (e.g. [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]).

Research Ethics Boards (REBs) also known as Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) and Research Ethics Committees (RECs) are charged with ensuring that research is planned and conducted in accordance with such laws and regulatory standards. In protecting the rights and welfare of participants, REBs must weigh possible harms to individuals against the plausible societal benefits of the research. They must ensure fair participant selection and, where applicable, confirm that appropriate provisions are in place for obtaining participant consent.

REBs often operate under the auspices of post-secondary institutions. Larger universities may support multiple REBs that serve different research areas, such as medical and health research and social science, psychology, and humanities research. Boards are constituted of people from a variety of backgrounds, each of whom contributes specific expertise to review and discussions. Members are appointed to the Board through established institutional practice. Nevertheless, most Board members bring a sincere interest and commitment to their roles. For university Faculty, Board membership may fulfil a service requirement that is part of their academic responsibilities.

The Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS2) advances a voluntary, self-governing model for REBs and institutions. The TCPS2 is a joint policy of Canada’s three federal research agencies (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council), and institutional and researcher adherence to the policy standards is a condition of funding. Recognizing the independence of REBs in their decision-making, institutions are required to support their functioning. Central to the agreement is that institutions conducting research must establish an REB and ensure that it has the “necessary and sufficient ongoing financial and administrative resources” to fulfil its duties (TCPS2 [ 3 ] p. 68). A similar requirement for support of IRB functioning is included in the US Common Rule (45 CFR 46.103 [ 5 ]). The operationalization of “necessary and sufficient” is subjective and likely to vary widely. To the extent that the desired outcomes (i.e. timely reviews and approvals) depend on the allocation of these resources, they too will vary.

Time and research ethics review

From the academic hallways to the literature, characterizations of REBs and the research ethics review process are seldom complimentary. While numerous criticisms have been levelled, it is the time to decision that is most consistently maligned [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ].

Factors associated with lengthy review time include incomplete or poorly completed applications [ 7 , 12 , 13 ], lack of administrative support [ 14 ], inadequately trained REB members [ 15 ], REB member competing commitments, expanding oversight requirements, and the sheer volume of applications [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Nevertheless, objective data on the inner workings of REBs are lacking [ 6 , 19 , 20 ].

Consequences of slow review times include centres’ withdrawing from multisite trials or limiting their participation in available trials [ 21 , 22 ], loss of needed research resources [ 23 ], and recruitment challenges in studies dependent on seasonal factors [ 24 ]. Lengthy time to study approval may ultimately delay patient access to potentially effective therapies [ 8 ].

Some jurisdictions have moved to regionalize or consolidate ethics review, using a centralized ethics review of protocols conducted on several sites. This enhances review efficiency for multisite research by removing the need for repeating reviews across centres [ 9 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ]. Recommendations for systemic improvement include better standardization of review practices, enhanced training for REB members, and requiring accreditation of review boards [ 9 ].

The research ethics review processes are not well understood, and no gold standard exists against which to evaluate board practices [ 19 , 20 ]. Consequently, there is little information on how REBs may systematically improve their methods and outcomes. This paper presents a model based on stakeholder responsibilities in the process of research ethics review and illustrates how each makes contributions to the time an application spends in this process. This model focusses on REBs operating under the auspices of academic institutions, typical in Canada and the USA.

Modelling the research ethics review process

The research ethics review process may appear to some like the proverbial black box. An application is submitted and considered and a decision is made:

SUBMIT > REVIEW > DECISION

In reality, the first step to understanding and improving the process is recognizing that research ethics review involves more than just the REB. Contributing to the overall efficiency—or inefficiency—of the review are other stakeholders and their roles in the development and submission of the application and the subsequent movement of the application back and forth between PIs, administrative staff, reviewers, the Board, and the Chair, until ideally the application is deemed ready for approval.

Identifying how a research ethics review progresses permits better understanding of the workflow, including the administrative and technological supports, roles, and responsibilities. The goal is to determine where challenges in the system exist so they can be remediated and efficiencies gained.

One way of understanding details of the process is to model it. We have used a modelling approach based in part on a method advanced by Ishikawa and further developed by the second author (JN) [ 29 , 30 ]. Traditionally, the Ishikawa “fishbone” or cause and effect diagram has been used to represent the components of a manufacturing enterprise and its application facilitates understanding how the elements of an operation may cause inefficiencies. This modelling provides a means of analysing process dispersion (e.g. who is accountable for what specific outcomes) and is frequently used when trying to understand time delays in undertakings.

In our model (Fig. 1 ), “Categories” represent key role actions that trigger a subsequent series of work activities. The “Artefacts” are the products resulting from a set of completed activities and reflect staged movement in the process. Implicit in the model is a temporal sequence and the passage of time, represented by the arrows.

Basic business activity model

Applying this strategy to facilitate understanding of time delays in ethics review requires that the problem (i.e. time) be considered in the context of all stakeholders. This includes those involved in the development and submission of the application, those involved in the administrative movement of the application through the system, those involved in the substantive consideration and deliberation of the application, and those involved in the final decision-making.

The model developed (Fig. 2 ) was based primarily on a review of the lead author’s (SP) institution’s REB application process. The model is generally consistent with the process and practices of several other REBs with which she has had experience over the past 20 years.

Research ethics activity model

What this model illustrates is that the research ethics review process is complex. There are numerous stakeholders involved, each of whom bears a portion of the responsibility for an application’s time in the system. The model illustrates a temporal sequence of events where, ideally, the movement of an application is unidirectional, left to right. Time is lost when applications stall or backflow in the process.

Stakeholders, accountabilities, and the research ethics review model

There are four main stakeholder groups in the research ethics review process: researchers/research teams, research ethics unit administrative staff, REB members, and the institution. Each plays a role in the transit of an application through the process and how well they undertake their role responsibilities affects the time that the application takes to move through. Table 1 presents a summary of recommendations for best practices.

Researchers

The researcher initiates the process of research ethics review by developing a proposal involving human participants and submitting an application. Across standards, the principal investigator is accountable for the conduct of the study, including adherence to research ethics requirements. Such standards are readily available both from the source (e.g. Panel on Research Ethics [Canada], National Institutes of Health [USA], Food and Drug Administration [USA]) and, typically, through institutional websites. Researchers have an obligation to be familiar with the rules for human participant research. Developing a sound proposal where ethics requirements are met at the outset places the application in a good position at the time of submission. Researchers are accountable for delays in review when ethical standards are not met and the application must be returned for revision. Tracking the reasons for return permits solutions, such as targeted educational activities, to be developed.

Core issues that investigators can address in the development of their applications include an ethical recruitment strategy, a sound consent process, and application of relevant privacy standards and legislation. Most research ethics units associated with institutions maintain websites where key information and resources may be found, such as consent templates, privacy standards, “frequently asked questions,” and application submission checklists [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Moreover, consulting with the REB in advance of submission may help researchers to prevent potentially challenging issues [ 15 ]. Investigators who are diligent in knowing about and applying required standards will experience fewer requests for revision and fewer stalls or backtracking once their applications are submitted. Some have suggested that researchers should be required, rather than merely expected, to have an understanding of legal and ethics standards before they are even permitted to submit an application [ 19 ].

The scholarly integrity of proposed research is an essential element of ethically acceptable human participant research. Researchers must be knowledgeable about the relevant scientific literature and present proposals that are justified based on what is known and where knowledge gaps exist. Research methods must be appropriate to the question and studies adequately powered. Novice or inexperienced researchers whose protocols have not undergone formal peer review (e.g. via supervisory committees, internal peer review committees, or competitive grant reviews) should seek consultation and informal peer review prior to ethics review to ensure the scientific validity of their proposals. While it is within the purview of REBs to question methods and design, it is not their primary mandate. Using REB resources for science review is an opportunity cost that can compromise efficient ethics review.

Finally, researchers are advised to review and proof their applications prior to submission to ensure that all required components have been addressed and the information in the application and supporting documents (e.g. consent forms, protocol) is consistent. Missing or discrepant information is causal to application return and therefore to time lost [ 7 ].

Administrators

Prior to submission, administrators may be the first point of contact for researchers seeking assistance with application requirements. Subsequently, they are often responsible for undertaking a preliminary, screening review of applications to make sure they are complete, with all required supporting documents and approvals in place. Once an application is complete, the administrative staff assign it to a reviewer. The reviewer may be a Board member or a subject-matter expert accountable to the Board.

Initial consultation and screening activities work best when staff have good knowledge of both institutional application requirements and ethics standards. Administrative checklists are useful tools to help ensure consistent application of standards in this preliminary application review. Poorly screened applications that reach reviewers may be delayed if the application must be returned to the administrator or the researcher for repair.

Reviewers typically send their completed reviews back to the administrators. In turn, the administrators either forward the applications to the Chair to consider (i.e. for delegated approval) or to a Board meeting agenda. In addition to ensuring that applications are complete, administrators may be accountable for monitoring how long a file is out for review. When reviews are delayed or incomplete for any reason, administrators may need to reassign the file to a different reviewer.

Administrators are therefore key players in the ethics review process, as they may be both initial resources for researchers and subsequently facilitate communication between researchers and Board members. Moreover, given past experience with both research teams and reviewers, they may be aware of areas where applicants struggle and when applications or reviews are likely to be deficient or delinquent. Actively tracking such patterns in the review process may reveal problems to which solutions can be developed. For example, applications consistently deficient in a specific area may signal the need for educational outreach and reviews that are consistently submitted late may provide impetus to recruit new Board members or reviewers.

REB members

The primary responsibility for evaluating the substantive ethics issues in applications and how they are managed rests with the REB members and the Chair. The Board may approve applications, approve pending modifications, or reject them based on their compliance with standards and regulations.

Like administrators, an REB member’s efficiency and review quality are enhanced by the use of standard tools, in this case standardized review templates, intended to guide reviewers and Board members to address a consistent set of criteria. Where possible, matching members’ expertise to the application to be reviewed also contributes to timely, good quality reviews.

REB functioning is enhanced with ongoing member training and education, yielding consistent, efficient application of ethics principles and regulatory standards [ 15 ]. This may be undertaken in a variety of ways, including Board member retreats, regular circulation of current articles, and attending presentations and conferences. REB Chairs are accountable to ensure consistency in the decisions made by the Board (TCPS 2014, Article 6.8). This demands that Chairs thoroughly understand ethical principles and regulatory standards and that they maintain awareness of previous decisions. Much time can be spent at Board meetings covering old ground. The use of REB decision banks has been recommended as a means of systematizing a record of precedents, thus contributing to overall quality improvement [ 34 ].

Institution

Where research ethics review takes place under the auspices of an academic institution, the institutions must typically take responsibility to adequately support the functioning of their Boards and promote a positive culture of research ethics [ 3 , 5 ]. Supporting the financial and human resource costs of participating in ongoing education (e.g. retreats, speakers, workshops, conferences) is therefore the responsibility of the institution.

Operating an REB is costly [ 35 ]. It is reasonable to assume that there is a relationship between the adequacy of resources allocated to the workload and flow and the time to an REB decision. Studies have demonstrated wide variability in times to determination [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 22 ]. However, comparisons are difficult to make because of confounding factors such as application volume, number of staff, number of REB members, application quality, application type (e.g. paper vs. electronic), and protocol complexity. Despite these variables, it appears that setting a modal target turnaround time of 6 weeks (±2 weeks) is reasonable and in line with the targets set in the European Union and the UK’s National Health Service [ 36 , 37 ]. Tracking the time spent at each step in the model may reveal where applications are typically delayed for long periods and may be indicative of areas where more resources need to be allocated or workflows redesigned.

As institutions grow their volumes of research, workloads correspondingly increase for institutional REBs. To maintain service levels, institutions need to ensure that resources allocated to REBs match the volume and intensity of work. Benchmarking costs (primarily human resources) relative to the number of applications and time to a decision will help to inform the allocation of resources needed to maintain desired service levels.

Finally, most REB members typically volunteer their Board services to the institution. Despite their good-faith intent to serve, Board members occasionally find that researchers view them as obstacles to or adversaries in the research enterprise. Board members may believe that researchers do not value the time and effort they contribute to review, while researchers may believe the REB and its members are unreasonable, obstructive, and a “thorn in their side” [ 15 ]. Clearly, relationships can be improved. Nevertheless, improving the timeliness and efficiency of research ethics review should help to soothe fevered brows on both sides of the issue.

Upshur [ 12 ] has previously noted that the contributions to research ethics such as Board membership and application review need to be accorded the same academic prestige as serving on peer review grant panels and editorial boards and undertaking manuscript reviews. In doing so, institutions will help to facilitate a culture of respect for, and shared commitment to, research ethics review, which may only benefit the process.

The activities, roles, and responsibilities identified in the ethics review model illustrate that it is a complex activity and that “the REB” is not a single entity. Multiple stakeholders each bear a portion of the accountability for how smoothly a research ethics application moves through the process. Time is used most efficiently when forward momentum is maintained and the application advances. Delays occur when the artefact (i.e. either the application or the application review) is not advanced as the accountable stakeholders fail to discharge their responsibilities or when the artefact fails to meet a standard and it is sent back. Ensuring that all stakeholders understand and are able to operationalize their responsibilities is essential. Success depends in part on the institutional context, where standards and expectations should be well communicated, and resources like education and administrative support provided, so that capacity to execute responsibilities is assured.

Applying this model will assist in identifying activities, accountabilities, and baseline performance levels. This information will contribute to improving local practice when deficiencies are identified and solutions implemented, such as training opportunities or reduction in duplicate activities. It will also facilitate monitoring as operational improvements over baseline performance could be measured. Where activities and benchmarks are well defined and consistent, comparisons both within and across REBs can be made.

Finally, this paper focused primarily on administrative efficiency in the context of research ethics review time. However, the identified problems and their suggested solutions would contribute not only to enhanced timeliness of review but also to enhanced quality of review and therefore human participant protection.

Beecher HK. Ethics and clinical research. NEMJ. 1966;274(24):1354–60.

Article Google Scholar

Kim WO. Institutional review board (IRB) and ethical issues in clinical research. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2012;62(1):3–12.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, December 2014. http://www.ethics.gc.ca/eng/index/ . Accessed 21 Jun 2017.

World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects as amended by the 64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013 U.S. Department of Health. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-researchinvolving-human-subjects/ . Accessed 21 Jun 2017.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, HHS.gov, Office for Human Research Protections. 45 CFR 46. Code of Federal Regulations. Title 45. Public Welfare. Department of Health and Human Services. Part 46. Protection of Human Subjects. Revised January 15, 2009. Effective July 14, 2009. Subpart A. Basic HHS Policy for Protection of Human Research Subjects. 2009. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/ . Accessed 21 Jun 2017.

Abbott L, Grady C. A systematic review of the empirical literature evaluating IRBs: what we know and what we still need to learn. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2011;6:3–19.

Egan-Lee E, Freitag S, Leblanc V, Baker L, Reeves S. Twelve tips for ethical approval for research in health professions education. Med Teach. 2011;33(4):268–72.

Hicks SC, James RE, Wong N, Tebbutt NC, Wilson K. A case study evaluation of ethics review systems for multicentre clinical trials. Med J Aust. 2009;191(5):3.

Google Scholar

Larson E, Bratts T, Zwanziger J, Stone P. A survey of IRB process in 68 U.S. hospitals. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36(3):260–4.

Silberman G, Kahn KL. Burdens on research imposed by institutional review boards: the state of the evidence and its implications for regulatory reform. Milbank Q. 2011;89(4):599–627.

Whitney SN, Schneider CE. Viewpoint: a method to estimate the cost in lives of ethics board review of biomedical research. J Intern Med. 2011;269(4):396–402.

Upshur REG. Ask not what your REB can do for you; ask what you can do for your REB. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(10):1113–4.

Taylor H. Moving beyond compliance: measuring ethical quality to enhance the oversight of human subjects research. IRB. 2007;29(5):9–14.

De Vries RG, Forsberg CP. What do IRBs look like? What kind of support do they receive? Account Res. 2002;9(3-4):199–216.

Guillemin M, Gillam L, Rosenthal D, Bolitho A. Human research ethics committees: examining their roles and practices. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7(3):38–49. doi: 10.1525/jer.2012.7.3.38 .

Grady C. Institutional review boards: purpose and challenges. Chest. 2015;148(5):1148–55.

Burman WJ, Reves RR, Cohn DL, Schooley RT. Breaking the camel’s back: multicenter clinical trials and local institutional review boards. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(2):152–7.

Whittaker E. Adjudicating entitlements: the emerging discourses of research ethics boards. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine. 2005;9(4):513–35. doi: 10.1177/1363459305056416 .

Turner L. Ethics board review of biomedical research: improving the process. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9(1):8–12.

Nicholls SG, Hayes TP, Brehaut JC, McDonald M, Weijer C, Saginur R, et al. A Scoping Review of Empirical Research Relating to Quality and Effectiveness of Research Ethics Review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0133639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133639 .

Mansbach J, Acholonu U, Clark S, Camargo CA. Variation in institutional review board responses to a standard, observational, pediatric research protocol. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(4):377–80.

Christie DRH, Gabriel GS, Dear K. Adverse effects of a multicentre system for ethics approval on the progress of a prospective multicentre trial of cancer treatment: how many patients die waiting? Internal Med J. 2007;37(10):680–6.

Greene SM, Geiger AM. A review finds that multicenter studies face substantial challenges but strategies exist to achieve institutional review board approval. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(8):784–90.

Jester PM, Tilden SJ, Li Y, Whitley RJ, Sullender WM. Regulatory challenges: lessons from recent West Nile virus trials in the United States. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27(3):254–9.

Flynn KE, Hahn CL, Kramer JM, Check DK, Dombeck CB, Bang S, et al. Using central IRBs for multicenter clinical trials in the United States. Plos One. 2013;8(1):e54999.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). Final NIH policy on the use of a single institutional review board for multi-site research. 2017. NOT-OD-16-094. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-16-094.html . Accessed 21 Jun 2017.

Check DK, Weinfurt KP, Dombeck CB, Kramer JM, Flynn KE. Use of central institutional review boards for multicenter clinical trials in the United States: a review of the literature. Clin Trials. 2013;10(4):560–7.

Dove ES, Townend D, Meslin EM, Bobrow M, Littler K, Nicol D, et al. Ethics review for international data-intensive research. Science. 2016;351(6280):1399–400.

Ishikawa K. Introduction to Quality Control. J. H. Loftus (trans.). Tokyo: 3A Corporation; 1990.

Nyeboer N. Early-stage requirements engineering to aid the development of a business process improvement strategy. Oxford: Kellogg College, University of Oxford; 2014.

University of Calgary. Researchers. Ethics and Compliance. CHREB. 2017. http://www.ucalgary.ca/research/researchers/ethics-compliance/chreb . Accessed 21 Jun 2017.

Harvard University. Committee on the Use of Human Subjects. University-area Institutional Review Board at Harvard. 2017. http://cuhs.harvard.edu . Accessed 21 Jun 2017.

Oxford University. UAS Home. Central University Research Ethics Committee (CUREC). 2016. https://www.admin.ox.ac.uk/curec/ . Accessed 21 Jun 2017.

Bean S, Henry B, Kinsey JM, McMurray K, Parry C, Tassopoulos T. Enhancing research ethics decision-making: an REB decision bank. IRB. 2010;32(6):9–12.

Sugarman J, Getz K, Speckman JL, Byrne MM, Gerson J, Emanuel EJ. The cost of institutional review boards in academic medical centers. NEMJ. 2005;352(17):1825–7.

National Health Service, Health Research Authority. Resources, Research legislation and governance, Standard Operating Procedures. 2017. http://www.hra.nhs.uk/resources/research-legislation-and-governance/standard-operating-procedures/ . Accessed 21 June 2017.

European Commission. Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 April 2001. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-1/dir_2001_20/dir_2001_20_en.pdf . Accessed 21 Jun 2017.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michael C. King for his review of the manuscript draft.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

The listed authors (SP, JN) have each undertaken the following: made substantial contributions to conception and design of the model; been involved in drafting the manuscript; have read and given final approval of the version to be published and participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Authors’ information

SP is the Chair of the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary. She is also a member of the Human Research Ethics Board at Mount Royal University and a member of the Research Ethics Board at the Alberta College of Art and Design. She serves on the Board of Directors for the Canadian Association of Research Ethics Boards.

JN is an Executive Technology Consultant specializing in Enterprise and Business Architecture. He has worked on process improvement initiatives across multiple industries as well as on the delivery of technology-based solutions. He was the project manager for the delivery of the IRISS online system for the Province of Alberta’s Health Research Ethics Harmonization initiative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Ethics approval and consent to participate, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Stacey A. Page

Conjoint Health Research Board, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

ITM Vocational University, Vadodara, Gujurat, India

Jeffrey Nyeboer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stacey A. Page .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Page, S.A., Nyeboer, J. Improving the process of research ethics review. Res Integr Peer Rev 2 , 14 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-017-0038-7

Download citation

Received : 31 March 2017

Accepted : 14 June 2017

Published : 18 August 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-017-0038-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Research ethics

- Research Ethics Boards

- Research Ethics Committees

- Medical research

- Applied ethics

- Institutional Review Boards

Research Integrity and Peer Review

ISSN: 2058-8615

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Ethics for Peer Reviewers

As a reviewer, you have a crucial role in supporting research integrity in the peer review and publishing process. This guide outlines some of the basic ethical principles that you should expect to follow.

These recommendations are based on the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) Ethical Guidelines for Peer Reviewers. Visit the COPE website to see the full ethical guidelines for reviewers.

PLOS is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). We abide by the COPE Core Practices and follow COPE’s best practice guidelines.

Basic ethical guidelines for peer reviewers

Choose assignments wisely

You should agree to review a manuscript only if you have the appropriate subject expertise and a sufficient amount of time to complete the review, in accordance with the journal deadline.

Provide an objective, honest, and unbiased review

→ Declare any potentially competing interests and/or recuse yourself from assignments if you have a conflict of interest. → Make sure your perspective is not influenced by authors’ origins, nationality, beliefs, gender, or other characteristics. → Do not impersonate another individual in your work as a reviewer.

Honor the confidentiality of the review process

Do not share information about manuscripts or reviews during or after peer review, and do not use any information from the review process for your own advantage.

Be respectful and professional

Make sure your review comments are professional. Keep your focus on the work and not on the individuals.

Read more about peer review ethics

Council of Science Editors, Reviewer Roles and Responsibilities

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, Responsibilities in the Submission and Peer Review Process – Reviewers

PLOS policy on ethical publishing practice

Thank you for helping to promote greater transparency and integrity in the review process!

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 14 December 2022

Advancing ethics review practices in AI research

- Madhulika Srikumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6776-4684 1 ,

- Rebecca Finlay 1 ,

- Grace Abuhamad 2 ,

- Carolyn Ashurst 3 ,

- Rosie Campbell 4 ,

- Emily Campbell-Ratcliffe 5 ,

- Hudson Hongo 1 ,

- Sara R. Jordan 6 ,

- Joseph Lindley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5527-3028 7 ,

- Aviv Ovadya ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8766-0137 8 &

- Joelle Pineau ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0747-7250 9 , 10

Nature Machine Intelligence volume 4 , pages 1061–1064 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

9218 Accesses

9 Citations

46 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Publisher Correction to this article was published on 11 January 2023

This article has been updated

The implementation of ethics review processes is an important first step for anticipating and mitigating the potential harms of AI research. Its long-term success, however, requires a coordinated community effort, to support experimentation with different ethics review processes, to study their effect, and to provide opportunities for diverse voices from the community to share insights and foster norms.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

As artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technologies continue to advance, awareness of the potential negative consequences on society of AI or ML research has grown. Anticipating and mitigating these consequences can only be accomplished with the help of the leading experts on this work: researchers themselves.

Several leading AI and ML organizations, conferences and journals have therefore started to implement governance mechanisms that require researchers to directly confront risks related to their work that can range from malicious use to unintended harms. Some have initiated new ethics review processes, integrated within peer review, which primarily facilitate a reflection on the potential risks and effects on society after the research is conducted (Box 1 ). This is distinct from other responsibilities that researchers undertake earlier in the research process, such as the protection of the welfare of human participants, which are governed by bodies such as institutional review boards (IRBs).

Box 1 Current ethics review practices

Current ethics review practices can be thought of as a sliding scale that varies according to how submitting authors must conduct an ethical analysis and document it in their contributions. Most conferences and journals are yet to initiate ethics review.

Key examples of different types of ethics review process are outlined below.

Impact statement

NeurIPS 2020 broader impact statements - all authors were required to include a statement of the potential broader impact of their work, such as its ethical aspects and future societal consequences of the research, including positive and negative effects. Organizers also specified additional evaluation criteria for paper reviewers to flag submissions with potential ethical issues.

Other examples include the NAACL 2021 and the EMNLP 2021 ethical considerations sections, which encourages authors and reviewers to consider ethical questions in their submitted papers.

Nature Machine Intelligence asks authors for ethical and societal impact statements in papers that involve the identification or detection of humans or groups of humans, including behavioural and socio-economic data.

NeurIPS 2021 paper checklist - a checklist to prompt authors to reflect on potential negative societal effects of their work during the paper writing process (as well as other criteria). Authors of accepted papers were encouraged to include the checklist as an appendix. Reviewers could flag papers that required additional ethics review by the appointed ethics committee.

Other examples include the ACL Rolling Review (ARR) Responsible NLP Research checklist, which is designed to encourage best practices for responsible research.

Code of ethics or guidelines

International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) code of ethics - ICLR required authors to review and acknowledge the conference’s code of ethics during the submission process. Authors were not expected to include discussion on ethical aspects in their submissions unless necessary. Reviewers were encouraged to flag papers that may violate the code of ethics.

Other examples include the ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct, which considers ethical principles but through the wider lens of professional conduct.

Although these initiatives are commendable, they have yet to be widely adopted. They are being pursued largely without the benefit of community alignment. As researchers and practitioners from academia, industry and non-profit organizations in the field of AI and its governance, we believe that community coordination is needed to ensure that critical reflection is meaningfully integrated within AI research to mitigate its harmful downstream consequences. The pace of AI and ML research and its growing potential for misuse necessitates that this coordination happen today.

Writing in Nature Machine Intelligence , Prunkl et al. 1 argue that the AI research community needs to encourage public deliberation on the merits and future of impact statements and other self-governance mechanisms in conference submissions. We agree. Here, we build on this suggestion, and provide three recommendations to enable this effective community coordination, as more ethics review approaches begin to emerge across conferences and journals. We believe that a coordinated community effort will require: (1) more research on the effects of ethics review processes; (2) more experimentation with such processes themselves; and (3) the creation of venues in which diverse voices both within and beyond the AI or ML community can share insights and foster norms. Although many of the challenges we address have been previously highlighted 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , this Comment takes a wider view, calling for collaboration between different conferences and journals by contextualizing this conversation against more recent studies 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 and developments.

Developments in AI research ethics

In the past, many applied scientific communities have contended with the potential harmful societal effects of their research. The infamous anthrax attacks in 2001, for example, catalysed the creation of the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity to prevent the misuse of biomedical research. Virology, in particular, has had long-running debates about the responsibility of individual researchers conducting gain-of-function research. Today, the field of AI research finds itself at a similar juncture 12 . Algorithmic systems are now being deployed for high-stakes applications such as law enforcement and automated decision-making, in which the tools have the potential to increase bias, injustice, misuse and other harms at scale. The recent adoption of ethics and impact statements and checklists at some AI conferences and journals signals a much-needed willingness to deal with these issues. However, these ethics review practices are still evolving and are experimental in nature. The developments acknowledge gaps in existing, well-established governance mechanisms, such as IRBs, which focus on risks to human participants rather than risks to society as a whole. This limited focus leaves ethical issues such as the welfare of data workers and non-participants, and the implications of data generated by or about people outside of their scope 6 . We acknowledge that such ethical reflection, beyond IRB mechanisms, may also be relevant to other academic disciplines, particularly those for whom large datasets created by or about people are increasingly common, but such a discussion is beyond the scope of this piece. The need to reflect on ethical concerns seems particularly pertinent within AI, because of its relative infancy as a field, the rapid development of its capabilities and outputs, and its increasing effects on society.

In 2020, the NeurIPS ML conference required all papers to carry a ‘broader impact’ statement examining the ethical and societal effects of the research. The conference updated its approach in 2021, asking authors to complete a checklist and to document potential downstream consequences of their work. In the same year, the Partnership on AI released a white paper calling for the field to expand peer review criteria to consider the potential effects of AI research on society, including accidents, unintended consequences, inappropriate applications and malicious uses 3 . In an editorial citing the white paper, Nature Machine Intelligence announced that it would ask submissions to carry an ethical statement when the research involves the identification of individuals and related sensitive data 13 , recognizing that mitigating downstream consequences of AI research cannot be completely disentangled from how the research itself is conducted. In another recent development, Stanford University’s Ethics and Society Review (ESR) requires AI researchers who apply for funding to identify if their research poses any risks to society and also explain how those risks will be mitigated through research design 14 .

Other developments include the rising popularity of interdisciplinary conferences examining the effects of AI, such as the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT), and the emergence of ethical codes of conduct for professional associations in computer science, such as the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM). Other actors have focused on upstream initiatives such as the integration of ethics reflection into all levels of the computer science curriculum.

Reactions from the AI research community to the introduction of ethics review practices include fears that these processes could restrict open scientific inquiry 3 . Scholars also note the inherent difficulty of anticipating the consequences of research 1 , with some AI researchers expressing concern that they do not have the expertise to perform such evaluations 7 . Other challenges include concerns about the lack of transparency in review practices at corporate research labs (which increasingly contribute to the most highly cited papers at premier AI conferences such as NeurIPS and ICML 9 ) as well as academic research culture and incentives supporting the ‘publish or perish’ mentality that may not allow time for ethical reflection.

With the emergence of these new attempts to acknowledge and articulate unique ethical considerations in AI research and the resulting concerns from some researchers, the need for the AI research community to come together to experiment, share knowledge and establish shared best practices is all the more urgent. We recommend the following three steps.

Study community behaviour and share learnings

So far, there are limited studies that have explored the responses of ML researchers to the launch of experimental ethics review practices. To understand how behaviour is changing and how to align practice with intended effect, we need to study what is happening and share learnings iteratively to advance innovation. For example, in response to the NeurIPS 2020 requirement for broader impact statements, a paper found that most researchers surveyed spent fewer than two hours working on this process 7 , perhaps retroactively towards the end of their research, making it difficult to know whether this reflection influenced or shifted research directions or not. Surveyed researchers also expressed scepticism about the mandated reflection on societal impacts 7 . An analysis of preprints found that researchers assessed impact through the narrow lens of technical contributions (that is, describing their work in the context of how it contributes to the research space and not how it may affect society), thereby overlooking potential effects on vulnerable stakeholders 8 . A qualitative analysis of a larger sample 10 and a quantitative analysis of all submitted papers 11 found that engagement was highly variable, and that researchers tended to favour the discussion of positive effects over negative effects.

We need to understand what works. These findings, all drawn from studies examining the implementation of ethics review at NeurIPS 2020, point to a pressing need to review actual versus intended community behaviour more thoroughly and consistently to evaluate the effectiveness of ethics review practices. We recognize that other fields have considered ethics in research in different ways. To get started, we propose the following approach, building on and expanding the analysis of Prunkl et al. 1 .

First, clear articulation of the purposes behind impact statements and other ethics review requirements is needed to evaluate efficacy and motivate future iterations by the community. Publication venues that organize ethics review must communicate expectations of this process comprehensively both at the level of individual contribution and for the community at large. At the individual level, goals could include encouraging researchers to reflect on the anticipated effects on society. At the community level, goals could include creating a culture of shared responsibility among researchers and (in the longer run) identifying and mitigating harms.

Second, because the exercise of anticipating downstream effects can be abstract and risks being reduced to a box-ticking endeavour, we need more data to ascertain whether they effectively promote reflection. Similar to the studies above, conference organizers and journal editors must monitor community behaviour through surveys with researchers and reviewers, partner with information scientists to analyse the responses 15 , and share their findings with the larger community. Reviewing community attitudes more systematically can provide data both on the process and effect of reflecting on harms for individual researchers, the quality of exploration encountered by reviewers, and uncover systemic challenges to practicing thoughtful ethical reflection. Work to better understand how AI researchers view their responsibility about the effects of their work in light of changing social contexts is also crucial.

Evaluating whether AI or ML researchers are more explicit about the downsides of their research in their papers is a preliminary metric for measuring change in community behaviour at large 2 . An analysis of the potential negative consequences of AI research can consider the types of application the research can make possible, the potential uses of those applications, and the societal effects they can cause 4 .

Building on the efforts at NeurIPS 16 and NAACL 17 , we can openly share our learnings as conference organizers and ethics committee members to gain a better understanding of what does and does not work.

Community behaviour in response to ethics review at the publication stage must also be studied to evaluate how structural and cultural forces throughout the research process can be reshaped towards more responsible research. The inclusion of diverse researchers and ethics reviewers, as well as people who face existing and potential harm, is a prerequisite to conduct research responsibly and improve our ability to anticipate harms.

Expand experimentation of ethical review

The low uptake of ethics review practices, and the lack of experimentation with such processes, limits our ability to evaluate the effectiveness of different approaches. Experimentation cannot be limited to a few conferences that focus on some subdomains of ML and computing research — especially for subdomains that envision real-world applications such as in employment, policing and healthcare settings. For instance, NeurIPS, which is largely considered a methods and theoretical conference, began an ethics review process in 2020, whereas conferences closer to applications, such as top-tier conferences in computer vision, have yet to implement such practices.

Sustained experimentation across subfields of AI can help us to study actual community behaviour, including differences in researcher attitudes and the unique opportunities and challenges that come with each domain. In the absence of accepted best practices, implementing ethics review processes will require conference organizers and journal editors to act under uncertainty. For that reason, we recognize that it may be easier for publication venues to begin their ethics review process by making it voluntary for authors. This can provide researchers and reviewers with the opportunity to become familiar with ethical and societal reflection, remove incentives for researchers to ‘game’ the process, and help the organizers and wider community to get closer to identifying how they can best facilitate the reflection process.

Create venues for debate, alignment and collective action

This work requires considerable cultural and institutional change that goes beyond the submission of ethical statements or checklists at conferences.

Ethical codes in scientific research have proven to be insufficient in the absence of community-wide norms and discussion 1 . Venues for open exchange can provide opportunities for researchers to share their experiences and challenges with ethical reflection. Such venues can be conducive to reflect on values as they evolve in AI or ML research, such as topics chosen for research, how research is conducted, and what values best reflect societal needs.

The establishment of venues for dialogue where conference organizers and journal editors can regularly share experiences, monitor trends in attitudes, and exchange insights on actual community behaviour across domains, while considering the evolving research landscape and range of opinions, is crucial. These venues would bring together an international group of actors involved throughout the research process, from funders, research leaders, and publishers to interdisciplinary experts adopting a critical lens on AI impact, including social scientists, legal scholars, public interest advocates, and policymakers.

In addition, reflection and dialogue can have a powerful role in influencing the future trajectory of a technology. Historically, gatherings convened by scientists have had far-reaching effects — setting the norms that guide research, and also creating practices and institutions to anticipate risks and inform downstream innovation. The Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA in 1975 and the Bermuda Meetings on genomic data sharing in the 1990s are instructive examples of scientists and funders, respectively, creating spaces for consensus-building 18 , 19 .

Proposing a global forum for gene-editing, scholars Jasanoff and Hulburt argued that such a venue should promote reflection on “what questions should be asked, whose views must be heard, what imbalances of power should be made visible, and what diversity of views exist globally” 20 . A forum for global deliberation on ethical approaches to AI or ML research will also need to do this.

By focusing on building the AI research field’s capacity to measure behavioural change, exchange insights, and act together, we can amplify emerging ethical review and oversight efforts. Doing this will require coordination across the entire research community and, accordingly, will come with challenges that need to be considered by conference organizers and others in their funding strategies. That said, we believe that there are important incremental steps that can be taken today towards realizing this change. For example, hosting an annual workshop on ethics review at pre-eminent AI conferences, or holding public panels on this subject 21 , hosting a workshop to review ethics statements 22 , and bringing conference organizers together 23 . Recent initiatives undertaken by AI research teams at companies to implement ethics review processes 24 , better understand societal impacts 25 and share learnings 26 , 27 also show how industry practitioners can have a positive effect. The AI community recognizes that more needs to be done to mitigate this technology’s potential harms. Recent developments in ethics review in AI research demonstrate that we must take action together.

Change history

11 january 2023.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-023-00608-6

Prunkl, C. E. A. et al. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3 , 104–110 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Hecht, B. et al. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.09544 (2021).

Partnership on AI. https://go.nature.com/3UUX0p3 (2021).

Ashurst, C. et al. https://go.nature.com/3gsQfvp (2020).

Hecht, B. https://go.nature.com/3AASZhf (2020).

Ashurst, C., Barocas, S., Campbell, R., Raji, D. in FAccT ‘22: 2022 ACM Conf. on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency 2057–2068 (2022).

Abuhamad, G. et al. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.13032 (2020).

Boyarskaya, M. et al. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.13416 (2020).

Birhane, A. et al. in FAccT ‘ 22: 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency 173–184 (2022).

Nanayakkara, P. et al. in AIES ‘ 21: Proc. 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society 795–806 (2021).

Ashurst, C., Hine, E., Sedille, P. & Carlier, A. in FAccT ‘22: 2022 ACM Conf. on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency 2047–2056 (2022).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. https://go.nature.com/3UTKOEJ (date accessed 16 September 2022).

Nat. Mach. Intell . 3 , 367 (2021).

Bernstein, M. S. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118 , e2117261118 (2021).

Pineau, J. et al. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 22 , 7459–7478 (2021).

Google Scholar

Benjio, S. et al. Neural Information Processing Systems. https://go.nature.com/3tQxGEO (2021).

Bender, E. M. & Fort, K. https://go.nature.com/3TWnbua (2021).

Gregorowius, D., Biller-Andorno, N. & Deplazes-Zemp, A. EMBO Rep. 18 , 355–358 (2017).

Jones, K. M., Ankeny, R. A. & Cook-Deegan, R. J. Hist. Biol. 51 , 693–805 (2018).

Jasanoff, S. & Hurlbut, J. B. Nature 555 , 435–437 (2018).

Partnership on AI. https://go.nature.com/3EpQwY4 (2021).

Sturdee, M. et al. in CHI Conf.Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts (CHI ’21 Extended Abstracts) ; https://doi.org/10.1145/3411763.3441330 (2021).

Partnership on AI. https://go.nature.com/3AzdNFW (2022).

DeepMind. https://go.nature.com/3EQyUWT (2022).

Meta AI. https://go.nature.com/3i3PBVX (2022).

Munoz Ferrandis, C. OpenRAIL; https://huggingface.co/blog/open_rail (2022).

OpenAI. https://go.nature.com/3GyZPYk (2022).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Partnership on AI, San Francisco, CA, USA

Madhulika Srikumar, Rebecca Finlay & Hudson Hongo

ServiceNow, Santa Clara, CA, USA

Grace Abuhamad

The Alan Turing Institute, London, UK

Carolyn Ashurst

OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA

Rosie Campbell

Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation, London, UK

Emily Campbell-Ratcliffe

Future of Privacy Forum, Washington, DC, USA

Sara R. Jordan

Design Research Works, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK

Joseph Lindley

Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, Cambridge, MA, USA

Aviv Ovadya

Meta AI, Menlo Park, CA, USA

Joelle Pineau

McGill University, Montreal, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Madhulika Srikumar .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Machine Intelligence thanks Carina Prunkl and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Srikumar, M., Finlay, R., Abuhamad, G. et al. Advancing ethics review practices in AI research. Nat Mach Intell 4 , 1061–1064 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-022-00585-2

Download citation

Published : 14 December 2022

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-022-00585-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

How to design an ai ethics board.

- Jonas Schuett

- Ann-Katrin Reuel

- Alexis Carlier

AI and Ethics (2024)

Machine learning in precision diabetes care and cardiovascular risk prediction

- Evangelos K. Oikonomou

- Rohan Khera

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2023)

Generative AI entails a credit–blame asymmetry

- Sebastian Porsdam Mann

- Brian D. Earp

- Julian Savulescu

Nature Machine Intelligence (2023)

Recommendations for the use of pediatric data in artificial intelligence and machine learning ACCEPT-AI

- V. Muralidharan

npj Digital Medicine (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Ethics responsibilities for peer reviewers

Jaap van Harten

About this video

When you accept a request to review a manuscript, what are you actually agreeing to? Some reviewers think they have a duty to identify authors’ unethical behavior, but, is that really the case? And are there any ethics “rules” reviewers should bear in mind when wielding their red pen?

In this webinar recording, experienced publisher Dr. Jaap van Harten answers those questions. He looks at the trust placed in reviewers not to share or reuse the contents of the unpublished manuscript. He explores the obligations of reviewers to provide an honest assessment of the work and highlight potential conflicts of interest. And, he reminds researchers they should only accept a review request if they have the time – and knowledge – required.

He also examines who carries the burden of ensuring a manuscript is free of plagiarism, fraud and other ethics issues. (Clue: the good news is, it’s not the reviewer! Although you can play an important role in flagging problem submissions.) You’ll come away armed with the confidence to identify where your reviewing responsibilities lie and the skills you need to meet them effectively

About the presenter

Executive Publisher Pharmacology & Pharmaceutical Sciences, Elsevier

Jaap van Harten was trained as a pharmacist at Leiden University, The Netherlands, and got a PhD in clinical pharmacology in 1988. He then joined Solvay Pharmaceuticals, where he held positions in pharmacokinetics, clinical pharmacology, medical marketing, and regulatory affairs. In 2000 he moved to Excerpta Medica, Elsevier’s Medical Communications branch, where he headed the Medical Department and the Strategic Publication Planning Department. In 2004 he joined Elsevier’s Publishing organization, initially as Publisher of the genetics journals and books, and currently as Executive Publisher Pharmacology & Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Recognizing peer reviewers: A webinar to celebrate editors and researchers

Transparency in peer review

How do I review a Data Article?

Generative AI in research evaluation

Building trust and engagement in peer review

Peer review - the nuts and bolts, quick guide research ethics.

Tools and resources for Reviewers

Transparency — the key to trust in peer review

Articles tagged in: Peer Review

Peer Review Week

Elsevier for Reviewers

Volunteer to Review

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

The view of synthetic biology in the field of ethics: a thematic systematic review provisionally accepted.

- 1 Ankara University, Türkiye

- 2 Department of Medical History and Ethics, School of Medicine, Ankara University, Ankara, Türkiye, Türkiye

The final, formatted version of the article will be published soon.

Synthetic biology is designing and creating biological tools and systems for useful purposes. It uses knowledge from biology, such as biotechnology, molecular biology, biophysics, biochemistry, bioinformatics, and other disciplines, such as engineering, mathematics, computer science, and electrical engineering. It is recognized as both a branch of science and technology. The scope of synthetic biology ranges from modifying existing organisms to gain new properties to creating a living organism from non-living components. Synthetic biology has many applications in important fields such as energy, chemistry, medicine, environment, agriculture, national security, and nanotechnology. The development of synthetic biology also raises ethical and social debates. This article aims to identify the place of ethics in synthetic biology. In this context, the theoretical ethical debates on synthetic biology from the 2000s to 2020, when the development of synthetic biology was relatively faster, were analyzed using the systematic review method. Based on the results of the analysis, the main ethical problems related to the field, problems that are likely to arise, and suggestions for solutions to these problems are included. The data collection phase of the study included a literature review conducted according to protocols, including planning, screening, selection and evaluation. The analysis and synthesis process was carried out in the next stage, and the main themes related to synthetic biology and ethics were identified. Searches were conducted in Web of Science, Scopus, PhilPapers and MEDLINE databases. Theoretical research articles and reviews published in peer-reviewed journals until the end of 2020 were included in the study. The language of publications was English. According to preliminary data, 1453 publications were retrieved from the four databases. Considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 58 publications were analyzed in the study. Ethical debates on synthetic biology have been conducted on various issues. In this context, the ethical debates in this article were examined under five themes: the moral status of synthetic biology products, synthetic biology and the meaning of life, synthetic biology and metaphors, synthetic biology and knowledge, and expectations, concerns, and problem solving: risk versus caution.

Keywords: Synthetic Biology, Ethics, Bioethics, Systematic review, Technology ethics, Responsible research and innovation

Received: 08 Mar 2024; Accepted: 10 May 2024.

Copyright: © 2024 Kurtoglu, Yıldız and Arda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: PhD. Ayse Kurtoglu, Ankara University, Ankara, Türkiye

People also looked at

- Coronavirus Updates

- Education at MUSC

- Adult Patient Care

- Hollings Cancer Center

- Children's Health

Biomedical Research

- Research Matters Blog

- NIH Peer Review