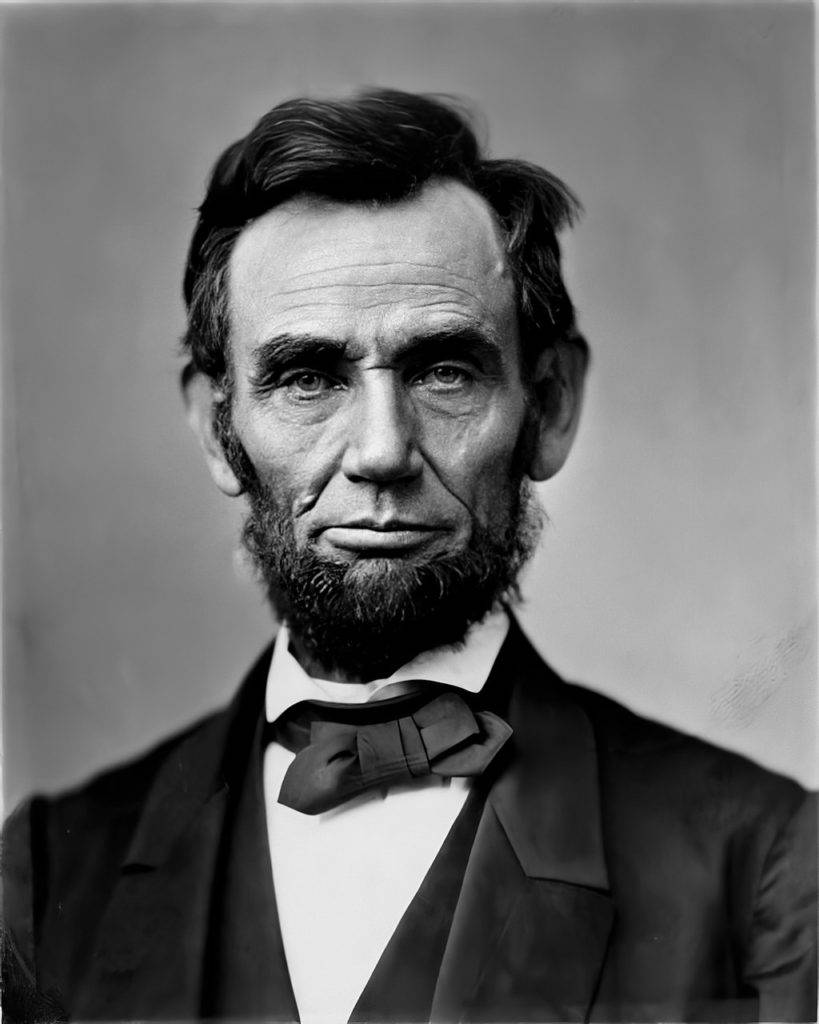

A Summary and Analysis of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

Here’s a question for you. Who was the main speaker at the event which became known as the Gettysburg Address? If you answered ‘Abraham Lincoln’, this post is for you. For the facts of what took place on the afternoon of November 19, 1863, four and a half months after the Union armies defeated Confederate forces in the Battle of Gettysburg, have become shrouded in myth. And one of the most famous speeches in all of American history was not exactly a resounding success when it was first spoken.

What was the Gettysburg Address?

The Gettysburg Address is the name given to a short speech (of just 268 words) that the US President Abraham Lincoln delivered at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery (which is now known as Gettysburg National Cemetery) in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on 19 November 1863. At the time, the American Civil War was still raging, and the Battle of Gettysburg had been the bloodiest battle in the war, with an estimated 23,000 casualties.

Gettysburg Address: summary

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

The opening words to the Gettysburg Address are now well-known. President Abraham Lincoln begins by harking back ‘four score and seven years’ – that is, eighty-seven years – to the year 1776, when the Declaration of Independence was signed and the nation known as the United States was founded.

The Declaration of Independence opens with the words: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal’. Lincoln refers to these words in the opening sentence of his declaration.

However, when he uses the words, he is including all Americans – male and female (he uses ‘men’ here, but ‘man’, as the old quip has it, embraces ‘woman’) – including African slaves, whose liberty is at issue in the war. The Union side wanted to abolish slavery and free the slaves, whereas the Confederates, largely in the south of the US, wanted to retain slavery.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

Lincoln immediately moves to throw emphasis on the sacrifice made by all of the fallen soldiers who gave their lives at Gettysburg, and at other battles during the Civil War. He reminds his listeners that the United States is still a relatively young country, not even a century old yet.

Will it endure when it is already at war with itself? Can all Americans be convinced that every single one of them, including its current slaves, deserves what the Declaration of Independence calls ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’?

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate – we can not consecrate – we can not hallow – this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

Lincoln begins the third and final paragraph of the Gettysburg Address with a slight rhetorical flourish: the so-called rule of three, which entails listing three things in succession. Here, he uses three verbs which are roughly synonymous with each other – ‘dedicate’, ‘consecrate’, ‘hallow’ – in order to drive home the sacrifice the dead soldiers have made. It is not for Lincoln and the survivors to declare this ground hallowed: the soldiers who bled for their cause have done that through the highest sacrifice it is possible to make.

Note that this is the fourth time Lincoln has used the verb ‘dedicate’ in this short speech: ‘and dedicated to the proposition …’; ‘any nation so conceived and so dedicated …’; ‘We have come to dedicate a portion …’; ‘we can not dedicate …’. He will go on to repeat the word twice more before the end of his address.

Repetition is another key rhetorical device used in persuasive writing, and Lincoln’s speech uses a great deal of repetition like this.

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Lincoln concludes his address by urging his listeners to keep up the fight, so that the men who have died in battles such as the Battle of Gettysburg will not have given their lives in vain to a lost cause. He ends with a now-famous phrase (‘government of the people, by the people, for the people’) which evokes the principle of democracy , whereby nations are governed by elected officials and everyone has a say in who runs the country.

Gettysburg Address: analysis

The mythical aura surrounding the Gettysburg Address, like many iconic moments in American history, tends to obscure some of the more surprising facts from us. For example, on the day Lincoln delivered his famous address, he was not the top billing: the main speaker at Gettysburg on 19 November 1863 was not Abraham Lincoln but Edward Everett .

Everett gave a long – many would say overlong – speech, which lasted two hours . Everett’s speech was packed full of literary and historical allusions which were, one feels, there to remind his listeners how learned Everett was. When he’d finished, his exhausted audience of some 15,000 people waited for their President to address them.

Lincoln’s speech is just 268 words long, because he was intended just to wrap things up with a few concluding remarks. His speech lasted perhaps two minutes, contrasted with Everett’s two hours.

Afterwards, Lincoln remarked that he had ‘failed’ in his duty to deliver a memorable speech, and some contemporary newspaper reports echoed this judgment, with the Chicago Times summarising it as a few ‘silly, flat and dishwatery utterances’ before hinting that Lincoln’s speech was an embarrassment, especially coming from so high an office as the President of the United States.

But in time, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address would come to be regarded as one of the great historic American speeches. This is partly because Lincoln eschewed the high-flown allusions and wordy style of most political orators of the nineteenth century.

Instead, he wanted to address people directly and simply, in plain language that would be immediately accessible and comprehensible to everyone. There is something democratic , in the broadest sense, about Lincoln’s choice of plain-spoken words and to-the-point sentences. He wanted everyone, regardless of their education or intellect, to be able to understand his words.

In writing and delivering a speech using such matter-of-fact language, Lincoln was being authentic and true to his roots. He may have been attempting to remind his listeners that he belonged to the frontier rather than to the East, the world of Washington and New York and Massachusetts.

There are several written versions of the Gettysburg Address in existence. However, the one which is viewed as the most authentic, and the most frequently reproduced, is the one known as the Bliss Copy . It is this version which is found on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. It is named after Colonel Alexander Bliss, the stepson of historian George Bancroft.

Bancroft asked Lincoln for a copy to use as a fundraiser for soldiers, but because Lincoln wrote on both sides of the paper, the speech was illegible and could not be reprinted, so Lincoln made another copy at Bliss’s request. This is the last known copy of the speech which Lincoln himself wrote out, and the only one signed and dated by him, so this is why it is widely regarded as the most authentic.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

The Gettysburg Address

Abraham lincoln, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Welcome to the LitCharts study guide on Abraham Lincoln's The Gettysburg Address . Created by the original team behind SparkNotes, LitCharts are the world's best literature guides.

The Gettysburg Address: Introduction

The gettysburg address: plot summary, the gettysburg address: detailed summary & analysis, the gettysburg address: themes, the gettysburg address: quotes, the gettysburg address: characters, the gettysburg address: symbols, the gettysburg address: theme wheel, brief biography of abraham lincoln.

Historical Context of The Gettysburg Address

Other books related to the gettysburg address.

- Full Title: The Gettysburg Address

- When Published: The speech was delivered on November 19, 1863, at the Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

- Literary Period: 19th century

- Genre: Speech

- Setting: Soldiers’ National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Extra Credit for The Gettysburg Address

The Other Gettysburg Address. At the cemetery dedication ceremony, President Lincoln was not the primary speaker. Edward Everett, one of the most celebrated speakers of the time, delivered a two-hour-long speech which was followed by Lincoln’s brief address. Everett later wrote to Lincoln and remarked, “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

A Lasting Legacy. The historian Garry Wills offers a unique perspective on the significance of the Gettysburg Address in his book Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America : “The Gettysburg Address has become an authoritative expression of the American spirit––as authoritative as the Declaration [of Independence] itself, and perhaps even more influential, since it determines how we read the Declaration. For most people now, the Declaration means what Lincoln told us it means, as a way of correcting the Constitution itself without overthrowing it.”

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, historic document, the gettysburg address (1863).

Abraham Lincoln | 1863

On November 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the most famous speeches in American history: the Gettysburg Address. The Union victory at Gettysburg was a key moment in the Civil War—thwarting General Robert E. Lee’s invasion of the North. President Lincoln offered this brief speech in a dedication ceremony for a new national cemetery near the Gettysburg battlefield. Lincoln was not even the featured speaker that day. Noted orator Edward Everett spoke for nearly two hours, while Lincoln spoke for a mere two minutes. In his powerful address, Lincoln embraced the Declaration of Independence, recalling how the nation was “conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” By resurrecting these promises, Lincoln committed post-Civil War America to “a new birth of freedom.” Following the Civil War, the Reconstruction Amendments—the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments—abolished slavery, wrote the Declaration of Independence’s commitment to freedom and equality into the Constitution, and promised to ban racial discrimination in voting. In so doing, the amendments sought to make Lincoln’s “new birth of freedom” a constitutional reality.

Selected by

The National Constitution Center

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate – we can not consecrate – we can not hallow – this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Explore the full document

Modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

The Words That Remade America

The significance of the Gettysburg Address

In the summer of 1863, General Robert E. Lee pushed northward into Pennsylvania. The Union army met him at Gettysburg, and from July 1 to July 3, the bloodiest battle of the war ensued. By the time it was over, the Confederates were in retreat, and the battlefield was strewn with more than 50,000 dead and wounded. Four months later, thousands gathered at Gettysburg to witness the dedication of a new cemetery. On the program was the standard assortment of music, remarks, and prayers. But what transpired that day was more extraordinary than anyone could have anticipated. In “The Words That Remade America,” the historian and journalist Garry Wills reconstructed the events leading up to the occasion, debunking the myth that President Lincoln wrote his remarks at the last minute, and carefully unpacking Lincoln’s language to show how—in just 272 words—he subtly cast the nation’s understanding of the Constitution in new, egalitarian terms. Wills’s book Lincoln at Gettysburg , from which the essay was adapted, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1993. —Sage Stossel

I N THE AFTERMATH of the Battle of Gettysburg, both sides, leaving fifty thousand dead or wounded or missing behind them, had reason to maintain a large pattern of pretense—Lee pretending that he was not taking back to the South a broken cause, Meade that he would not let the broken pieces fall through his fingers. It would have been hard to predict that Gettysburg, out of all this muddle, these missed chances, all the senseless deaths, would become a symbol of national purpose, pride, and ideals. Abraham Lincoln transformed the ugly reality into something rich and strange—and he did it with 272 words. The power of words has rarely been given a more compelling demonstration.

The residents of Gettysburg had little reason to be satisfied with the war machine that had churned up their lives. General George Gordon Meade may have pursued General Robert E. Lee in slow motion, but he wired headquarters that “I cannot delay to pick up the debris of the battlefield.” That debris was mainly a matter of rotting horseflesh and manflesh—thousands of fermenting bodies, with gas-distended bellies, deliquescing in the July heat. For hygienic reasons, the five thousand horses and mules had to be consumed by fire, trading the smell of decaying flesh for that of burning flesh. Human bodies were scattered over, or (barely) under, the ground. Suffocating teams of Union soldiers, Confederate prisoners, and dragooned civilians slid the bodies beneath a minimal covering as fast as possible—crudely posting the names of the Union dead with sketchy information on boards, not stopping to figure out what units the Confederate bodies had belonged to. It was work to be done hugger-mugger or not at all, fighting clustered bluebottle flies black on the earth, shoveling and retching by turns.

The whole area of Gettysburg—a town of only twenty-five hundred inhabitants—was one makeshift burial ground, fetid and steaming. Andrew Curtin, the Republican governor of Pennsylvania, was facing a difficult reelection campaign. He must placate local feeling, deal with other states diplomatically, and raise the funds to cope with corpses that could go on killing by means of fouled streams or contaminating exhumations.

Curtin made the thirty-two-year-old David Wills, a Gettysburg lawyer, his agent on the scene. Wills (who is no relation to the author) … meant to dedicate the ground that would hold the corpses even before they were moved. He felt the need for artful words to sweeten the poisoned air of Gettysburg. He asked the principal wordsmiths of his time to join this effort—Longfellow, Whittier, Bryant. All three poets, each for his own reason, found their muse unbiddable. But Wills was not terribly disappointed. The normal purgative for such occasions was a large-scale, solemn act of oratory, a kind of performance art that had great power over audiences in the middle of the nineteenth century. Some later accounts would emphasize the length of the main speech at the Gettysburg dedication, as if that were an ordeal or an imposition on the audience. But a talk of several hours was customary and expected then—much like the length and pacing of a modern rock concert. The crowds that heard Lincoln debate Stephen Douglas in 1858, through three-hour engagements, were delighted to hear Daniel Webster and other orators of the day recite carefully composed paragraphs for two hours at the least.

The champion at such declamatory occasions, after the death of Daniel Webster, was Webster’s friend Edward Everett. Everett was that rare thing, a scholar and an Ivy League diplomat who could hold mass audiences in thrall. His voice, diction, and gestures were successfully dramatic, and he habitually performed his well-crafted text, no matter how long, from memory. Everett was the inevitable choice for Wills, the indispensable component in the scheme for the cemetery’s consecration. Battlefields were something of a specialty with Everett—he had augmented the fame of Lexington and Concord and Bunker Hill by his oratory at those Revolutionary sites. Simply to have him speak at Gettysburg would add this field to the sacred roll of names from the Founders’ battles.

Everett was invited, on September 23, to appear October 23. That would leave all of November for filling the graves. But a month was not sufficient time for Everett to make his customary preparation for a major speech. He did careful research on the battles he was commemorating—a task made difficult in this case by the fact that official accounts of the engagement were just appearing. Everett would have to make his own inquiries. He could not be ready before November 19. Wills seized on that earliest moment, though it broke with the reburial schedule that had been laid out to follow on the October dedication. He decided to move up the reburial, beginning it in October and hoping to finish by November 19.

The careful negotiations with Everett form a contrast, more surprising to us than to contemporaries, with the casual invitation to President Lincoln, issued some time later as part of a general call for the federal Cabinet and other celebrities to join in what was essentially a ceremony of the participating states.

No insult was intended. Federal responsibility for or participation in state activities was not assumed then. And Lincoln took no offense. Though specifically invited to deliver only “a few appropriate remarks” to open the cemetery, he meant to use this opportunity. The partly mythical victory of Gettysburg was an element of his Administration’s war propaganda. (There were, even then, few enough victories to boast of.) Beyond that, he was working to unite the rival Republican factions of Governor Curtin and Simon Cameron, Edwin Stanton’s predecessor as Secretary of War. He knew that most of the state governors would be attending or sending important aides—his own bodyguard, Ward Lamon, who was acting as chief marshal organizing the affair, would have alerted him to the scale the event had assumed, with a tremendous crowd expected. This was a classic situation for political fence-mending and intelligence-gathering. Lincoln would take with him aides who would circulate and bring back their findings. Lamon himself had a cluster of friends in Pennsylvania politics, including some close to Curtin, who had been infuriated when Lincoln overrode his opposition to Cameron’s Cabinet appointment.

Lincoln also knew the power of his rhetoric to define war aims. He was seeking occasions to use his words outside the normal round of proclamations and reports to Congress. His determination not only to be present but to speak is seen in the way he overrode staff scheduling for the trip to Gettysburg. Stanton had arranged for a 6:00 A.M. train to take him the hundred and twenty rail miles to the noontime affair. But Lincoln was familiar enough by now with military movement to appreciate what Clausewitz called “friction” in the disposal of forces—the margin for error that must always be built into planning. Lamon would have informed Lincoln about the potential for muddle on the nineteenth. State delegations, civic organizations, military bands and units, were planning to come by train and road, bringing at least ten thousand people to a town with poor resources for feeding and sheltering crowds (especially if the weather turned bad). So Lincoln countermanded Stanton’s plan:

I do not like this arrangement. I do not wish to so go that by the slightest accident we fail entirely, and, at the best, the whole to be a mere breathless running of the gauntlet …

If Lincoln had not changed the schedule, he would very likely not have given his talk. Even on the day before, his trip to Gettysburg took six hours, with transfers in Baltimore and at Hanover Junction … [He] kept his resolution to leave a day early even when he realized that his wife was hysterical over one son’s illness soon after the death of another son. The President had important business in Gettysburg.

For a man so determined to get there, Lincoln seems—in familiar accounts—to have been rather cavalier about preparing what he would say in Gettysburg. The silly but persistent myth is that he jotted his brief remarks on the back of an envelope. (Many details of the day are in fact still disputed, and no definitive account exists.) Better-attested reports have him considering them on the way to a photographer’s shop in Washington, writing them on a piece of cardboard as the train took him on the hundred-and-twenty-mile trip, penciling them in David Wills’s house on the night before the dedication, writing them in that house on the morning of the day he had to deliver them, and even composing them in his head as Everett spoke, before Lincoln rose to follow him.

These recollections, recorded at various times after the speech had been given and won fame, reflect two concerns on the part of those speaking them. They reveal an understandable pride in participation at the historic occasion. It was not enough for those who treasured their day at Gettysburg to have heard Lincoln speak—a privilege they shared with ten to twenty thousand other people, and an experience that lasted no more than three minutes. They wanted to be intimate with the gestation of that extraordinary speech, watching the pen or pencil move under the inspiration of the moment.

That is the other emphasis in these accounts—that it was a product of the moment, struck off as Lincoln moved under destiny’s guidance. Inspiration was shed on him in the presence of others. The contrast with Everett’s long labors of preparation is always implied. Research, learning, the student’s lamp—none of these were needed by Lincoln, whose unsummoned muse was prompting him, a democratic muse unacquainted with the library. Lightning struck, and each of our informants (or their sources) was there when it struck …

These mythical accounts are badly out of character for Lincoln, who composed his speeches thoughtfully. His law partner, William Herndon, having observed Lincoln’s careful preparation of cases, recorded that he was a slow writer, who liked to sort out his points and tighten his logic and his phrasing. That is the process vouched for in every other case of Lincoln’s memorable public statements. It is impossible to imagine him leaving his Gettysburg speech to the last moment. He knew he would be busy on the train and at the site—important political guests were with him from his departure, and more joined him at Baltimore, full of talk about the war, elections, and policy … He could not count on any time for the concentration he required when weighing his words …

Lincoln’s train arrived toward dusk in Gettysburg. There were still coffins stacked at the station for completing the reburials. Lamon, Wills, and Everett met Lincoln and escorted him the two blocks to the Wills home, where dinner was waiting, along with almost two dozen other distinguished guests. Lincoln’s black servant, William Slade, took his luggage to the second-story room where he would stay that night, which looked out on the square.

Everett was already in residence at the Wills house, and Governor Curtin’s late arrival led Wills to suggest that the two men share a bed. The governor thought he could find another house to receive him, though lodgings were so overcrowded that Everett said in his diary that “the fear of having the Executive of Pennsylvania tumbled in upon me kept me awake until one.” Everett’s daughter was sleeping with two other women, and the bed broke under their weight. William Saunders, the cemetery’s designer, who would have an honored place on the platform the next day, could find no bed and had to sleep sitting up in a crowded parlor …

Early in the morning Lincoln took a carriage ride to the battle sites. Later, Ward Lamon and his specially uniformed marshals assigned horses to the various dignitaries (carriages would have clogged the site too much). Although the march was less than a mile, Lamon had brought thirty horses into town, and Wills had supplied a hundred, to honor the officials present.

Lincoln sat his horse gracefully (to the surprise of some), and looked meditative during the long wait while marshals tried to coax into line important people more concerned about their dignity than the President was about his. Lincoln was wearing a mourning band on his hat for his dead son. He also wore white gauntlets, which made his large hands on the reins dramatic by contrast with his otherwise black attire.

Everett had gone out earlier, by carriage, to prepare himself in the special tent he had asked for near the platform. At sixty-nine, he had kidney trouble and needed to relieve himself just before and after the three-hour ceremony. (He had put his problem so delicately that his hosts did not realize that he meant to be left alone in the tent; but he finally coaxed them out.) Everett mounted the platform at the last moment, after most of the others had arrived.

Those on the raised platform were hemmed in close by standing crowds. When it had become clear that the numbers might approach twenty thousand, the platform had been set at some distance from the burial operations. Only a third of the expected bodies had been buried, and those under fresh mounds. Other graves had been readied for the bodies, which arrived in irregular order (some from this state, some from that), making it impossible to complete one section at a time. The whole burial site was incomplete. Marshals tried to keep the milling thousands out of the work in progress.

Everett, as usual, had neatly placed his thick text on a little table before him—and then ostentatiously refused to look at it. He was able to indicate with gestures the sites of the battle’s progress, visible from where he stood. He excoriated the rebels for their atrocities, implicitly justifying the fact that some Confederate skeletons were still unburied, lying in the clefts of Devil’s Den under rocks and autumn leaves. Two days earlier Everett had been shown around the field, and places were pointed out where the bodies lay. His speech, for good or ill, would pick its way through the carnage.

As a former Secretary of State, Everett had many sources, in and outside government, for the information he had gathered so diligently. Lincoln no doubt watched closely how the audience responded to passages that absolved Meade of blame for letting Lee escape. The setting of the battle in a larger logic of campaigns had an immediacy for those on the scene which we cannot recover. Everett’s familiarity with the details was flattering to the local audience, which nonetheless had things to learn from this shapely presentation of the whole three days’ action. This was like a modern “docudrama” on television, telling the story of recent events on the basis of investigative reporting. We badly misread the evidence if we think Everett failed to work his customary magic. The best witnesses on the scene—Lincoln’s personal secretaries, John Hay and John Nicolay, with their professional interest in good prose and good theater—praised Everett at the time and ever after. He received more attention in their biography’s chapter on Gettysburg than did their own boss.

When Lincoln rose, it was with a sheet or two, from which he read. Lincoln’s three minutes would ever after be obsessively contrasted with Everett’s two hours in accounts of this day. It is even claimed that Lincoln disconcerted the crowd with his abrupt performance, so that people did not know how to respond (“Was that all?”). Myth tells of a poor photographer making leisurely arrangements to take Lincoln’s picture, expecting him to be standing for some time. But it is useful to look at the relevant part of the program:

Music. by Birgfield’s Band . Prayer. by Rev. T.H. Stockton, D.D. Music. by the Marine Band. ORATION. by Hon. Edward Everett. Music. Hymn composed by B. B. French. DEDICATORY REMARKS BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES. Dirge. sung by Choir selected for the occasion. Benediction. by Rev. H.L. Baugher, D.D.

There was only one “oration” announced or desired here. Though we call Lincoln’s text the Gettysburg Address, that title clearly belongs to Everett. Lincoln’s contribution, labeled “remarks,” was intended to make the dedication formal (somewhat like ribbon-cutting at modern openings). Lincoln was not expected to speak at length, any more than Rev. T. H. Stockton was (though Stockton’s prayer is four times the length of the President’s remarks). A contrast of length with Everett’s talk raises a false issue. Lincoln’s text is startlingly brief for what it accomplished, but that would be equally true if Everett had spoken for a shorter time or had not spoken at all.

Nonetheless, the contrast was strong. Everett’s voice was sweet and expertly modulated; Lincoln’s was high to the point of shrillness, and his Kentucky accent offended some eastern sensibilities. But Lincoln derived an advantage from his high tenor voice—carrying power. If there is agreement on any one aspect of Lincoln’s delivery, at Gettysburg or elsewhere, it is on his audibility. Modern impersonators of Lincoln, such as Walter Huston, Raymond Massey, Henry Fonda, and the various actors who give voice to Disneyland animations of the President, bring him before us as a baritone, which is considered a more manly or heroic voice—though both the Roosevelt Presidents of our century were tenors. What should not be forgotten is that Lincoln was himself an actor, an expert raconteur and mimic, and one who spent hours reading speeches out of Shakespeare to any willing (or sometimes unwilling) audience. He knew a good deal about rhythmic delivery and meaningful inflection. John Hay, who had submitted to many of those Shakespeare readings, gave high marks to his boss’s performance at Gettysburg. He put in his diary at the time that “the President, in a fine, free way, with more grace than is his wont, said his half dozen words of consecration.” Lincoln’s text was polished, his delivery emphatic; he was interrupted by applause five times. Read in a slow, clear way to the farthest listeners, the speech would take about three minutes. It is quite true the audience did not take in all that happened in that short time—we are still trying to weigh the consequences of Lincoln’s amazing performance. But the myth that Lincoln was disappointed in the result—that he told the unreliable Lamon that his speech, like a bad plow, “won’t scour”—has no basis. He had done what he wanted to do, and Hay shared the pride his superior took in an important occasion put to good use.

At the least, Lincoln had far surpassed David Wills’s hope for words to disinfect the air of Gettysburg. His speech hovers far above the carnage. He lifts the battle to a level of abstraction that purges it of grosser matter—even “earth” is mentioned only as the thing from which the tested form of government shall not perish. The nightmare realities have been etherealized in the crucible of his language.

Lincoln was here to clear the infected atmosphere of American history itself, tainted with official sins and inherited guilt. He would cleanse the Constitution—not as William Lloyd Garrison had, by burning an instrument that countenanced slavery. He altered the document from within, by appeal from its letter to the spirit, subtly changing the recalcitrant stuff of that legal compromise, bringing it to its own indictment. By implicitly doing this, he performed one of the most daring acts of open-air sleight of hand ever witnessed by the unsuspecting. Everyone in that vast throng of thousands was having his or her intellectual pocket picked. The crowd departed with a new thing in its ideological luggage, the new Constitution Lincoln had substituted for the one they had brought there with them. They walked off from those curving graves on the hillside, under a changed sky, into a different America. Lincoln had revolutionized the Revolution, giving people a new past to live with that would change their future indefinitely …

Lincoln’s speech at Gettysburg worked several revolutions, beginning with one in literary style. Everett’s talk was given at the last point in history when such a performance could be appreciated without reservation. It was made obsolete within a half hour of the time when it was spoken. Lincoln’s remarks anticipated the shift to vernacular rhythms which Mark Twain would complete twenty years later. Hemingway claimed that all modern American novels are the offspring of Huckleberry Finn . It is no greater exaggeration to say that all modern political prose descends from the Gettysburg Address …

The spare quality of Lincoln’s prose did not come naturally but was worked at. Lincoln not only read aloud, to think his way into sounds, but also wrote as a way of ordering his thought … He loved the study of grammar, which some think the most arid of subjects. Some claimed to remember his gift for spelling, a view that our manuscripts disprove. Spelling as he had to learn it (separate from etymology) is more arbitrary than logical. It was the logical side of language—the principles of order as these reflect patterns of thought or the external world—that appealed to him.

He was also, Herndon tells us, laboriously precise in his choice of words. He would have agreed with Mark Twain that the difference between the right word and the nearly right one is that between lightning and a lightning bug. He said, debating Douglas, that his foe confused a similarity of words with a similarity of things—as one might equate a horse chestnut with a chestnut horse.

As a speaker, Lincoln grasped Twain’s later insight: “Few sinners are saved after the first twenty minutes of a sermon.” The trick, of course, was not simply to be brief but to say a great deal in the fewest words. Lincoln justly boasted of his Second Inaugural’s seven hundred words, “Lots of wisdom in that document, I suspect.” The same is even truer of the Gettysburg Address, which uses fewer than half that number of words.

The unwillingness to waste words shows up in the address’s telegraphic quality—the omission of coupling words, a technique rhetoricians call asyndeton. Triple phrases sound as to a drumbeat, with no “and” or “but” to slow their insistency:

we are engaged … We are met … We have come … we can not dedicate … we can not consecrate … we can not hallow … that from these honored dead … that we here highly resolve … that this nation, under God … government of the people , by the people , for the people …

Despite the suggestive images of birth, testing, and rebirth, the speech is surprisingly bare of ornament. The language itself is made strenuous, its musculature easily traced, so that even the grammar becomes a form of rhetoric. By repeating the antecedent as often as possible, instead of referring to it indirectly by pronouns like “it” and “they,” or by backward referential words like “former” and “latter,” Lincoln interlocks his sentences, making of them a constantly self-referential system. This linking up by explicit repetition amounts to a kind of hook-and-eye method for joining the parts of his address. The rhetorical devices are almost invisible, since they use no figurative language. (I highlight them typographically here.)

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in A GREAT CIVIL WAR, testing whether that nation , or any nation so conceived and so dedicated , can long endure. We are met on a great BATTLE-FIELD of THAT WAR. We have come to dedicate a portion of THAT FIELD , as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate —we can not consecrate —we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here , have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from THESE HONORED DEAD we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion— that we here highly resolve that THESE DEAD shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Each of the paragraphs printed separately here is bound to the preceding and the following by some resumptive element. Only the first and last paragraphs do not (because they cannot) have this two-way connection to their setting. Not all of the “pointer” phrases replace grammatical antecedents in the technical sense. But Lincoln makes them perform analogous work. The nation is declared to be “dedicated” before the term is given further uses for individuals present at the ceremony, who repeat (as it were) the national consecration. The compactness of the themes is emphasized by this reliance on a few words in different contexts.

A similar linking process is performed, almost subliminally, by the repeated pinning of statements to this field, these dead, who died here , for that kind of nation. The reverential touching, over and over, of the charged moment and place leads Lincoln to use “here” eight times in the short text, the adjectival “that” five times, and “this” four times. The spare vocabulary is not impoverishing, because of the subtly interfused constructions, in which the classicist Charles Smiley identified “two antitheses, five cases of anaphora, eight instances of balanced phrases and clauses, thirteen alliterations.” “Plain speech” was never less artless. Lincoln forged a new lean language to humanize and redeem the first modern war.

This was the perfect medium for changing the way most Americans thought about the nation’s founding. Lincoln did not argue law or history, as Daniel Webster had. He made history. He came not to present a theory but to impose a symbol, one tested in experience and appealing to national values, expressing emotional urgency in calm abstractions. He came to change the world, to effect an intellectual revolution. No other words could have done it. The miracle is that these words did. In his brief time before the crowd at Gettysburg he wove a spell that has not yet been broken—he called up a new nation out of the blood and trauma.

[Lincoln] not only presented the Declaration of Independence in a new light, as a matter of founding law, but put its central proposition, equality, in a newly favored position as a principle of the Constitution … What had been mere theory in the writings of James Wilson, Joseph Story, and Daniel Webster—that the nation preceded the states, in time and importance—now became a lived reality of the American tradition. The results of this were seen almost at once. Up to the Civil War “the United States” was invariably a plural noun: “The United States are a free country.” After Gettysburg it became a singular: “The United States is a free country.” This was a result of the whole mode of thinking that Lincoln expressed in his acts as well as his words, making union not a mystical hope but a constitutional reality. When, at the end of the address, he referred to government “of the people, by the people, for the people,” he was not, like Theodore Parker, just praising popular government as a Transcendentalist’s ideal. Rather, like Webster, he was saying that America was a people accepting as its great assignment what was addressed in the Declaration. This people was “conceived” in 1776, was “brought forth” as an entity whose birth was datable (“four score and seven years” before) and placeable (“on this continent”), and was capable of receiving a “new birth of freedom.”

Thus Abraham Lincoln changed the way people thought about the Constitution …

The Gettysburg Address has become an authoritative expression of the American spirit—as authoritative as the Declaration itself, and perhaps even more influential, since it determines how we read the Declaration. For most people now, the Declaration means what Lincoln told us it means, as he did to correct the Constitution without overthrowing it … By accepting the Gettysburg Address, and its concept of a single people dedicated to a proposition, we have been changed. Because of it, we live in a different America.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Gettysburg Address

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 20, 2023 | Original: August 24, 2010

On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln delivered remarks, which later became known as the Gettysburg Address, at the official dedication ceremony for the National Cemetery of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania, on the site of one of the bloodiest and most decisive battles of the Civil War. Though he was not the featured orator that day, Lincoln’s brief address would be remembered as one of the most important speeches in American history. In it, he invoked the principles of human equality contained in the Declaration of Independence and connected the sacrifices of the Civil War with the desire for “a new birth of freedom,” as well as the all-important preservation of the Union created in 1776 and its ideal of self-government.

Burying the Dead at Gettysburg

From July 1 to July 3, 1863, the invading forces of General Robert E. Lee ’s Confederate Army clashed with the Army of the Potomac (under its newly appointed leader, General George G. Meade ) in Gettysburg, some 35 miles southwest of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania . Casualties were high on both sides: Out of roughly 170,000 Union and Confederate soldiers, there were 23,000 Union casualties (more than one-quarter of the army’s effective forces) and 28,000 Confederates killed, wounded or missing (more than a third of Lee’s army) in the Battle of Gettysburg . After three days of battle, Lee retreated towards Virginia on the night of July 4. It was a crushing defeat for the Confederacy, and a month later the great general would offer Confederate President Jefferson Davis his resignation; Davis refused to accept it.

Did you know? Edward Everett, the featured speaker at the dedication ceremony of the National Cemetery of Gettysburg, later wrote to Lincoln, "I wish that I could flatter myself that I had come as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes."

As after previous battles, thousands of Union soldiers killed at Gettysburg were quickly buried, many in poorly marked graves. In the months that followed, however, local attorney David Wills spearheaded efforts to create a national cemetery at Gettysburg. Wills and the Gettysburg Cemetery Commission originally set October 23 as the date for the cemetery’s dedication, but delayed it to mid-November after their choice for speaker, Edward Everett, said he needed more time to prepare. Everett, the former president of Harvard College, former U.S. senator and former secretary of state, was at the time one of the country’s leading orators. On November 2, just weeks before the event, Wills extended an invitation to President Lincoln, asking him “formally [to] set apart these grounds to their sacred use by a few appropriate remarks.”

Gettysburg Address: Lincoln’s Preparation

Though Lincoln was extremely frustrated with Meade and the Army of the Potomac for failing to pursue Lee’s forces in their retreat, he was cautiously optimistic as the year 1863 drew to a close. He also considered it significant that the Union victories at Gettysburg and at Vicksburg, under General Ulysses S. Grant , had both occurred on the same day: July 4, the anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence .

When he received the invitation to make the remarks at Gettysburg, Lincoln saw an opportunity to make a broad statement to the American people on the enormous significance of the war, and he prepared carefully. Though long-running popular legend holds that he wrote the speech on the train while traveling to Pennsylvania, he probably wrote about half of it before leaving the White House on November 18, and completed writing and revising it that night, after talking with Secretary of State William H. Seward , who had accompanied him to Gettysburg.

The Historic Gettysburg Address

On the morning of November 19, Everett delivered his two-hour oration (from memory) on the Battle of Gettysburg and its significance, and the orchestra played a hymn composed for the occasion by B.B. French. Lincoln then rose to the podium and addressed the crowd of some 15,000 people. He spoke for less than two minutes, and the entire speech was fewer than 275 words long. Beginning by invoking the image of the founding fathers and the new nation, Lincoln eloquently expressed his conviction that the Civil War was the ultimate test of whether the Union created in 1776 would survive, or whether it would “perish from the earth.” The dead at Gettysburg had laid down their lives for this noble cause, he said, and it was up to the living to confront the “great task” before them: ensuring that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

The essential themes and even some of the language of the Gettysburg Address were not new; Lincoln himself, in his July 1861 message to Congress, had referred to the United States as “a democracy–a government of the people, by the same people.” The radical aspect of the speech, however, began with Lincoln’s assertion that the Declaration of Independence–and not the Constitution–was the true expression of the founding fathers’ intentions for their new nation. At that time, many white slave owners had declared themselves to be “true” Americans, pointing to the fact that the Constitution did not prohibit slavery; according to Lincoln, the nation formed in 1776 was “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” In an interpretation that was radical at the time–but is now taken for granted–Lincoln’s historic address redefined the Civil War as a struggle not just for the Union, but also for the principle of human equality.

Gettysburg Address Text

The full text of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address is as follows:

"Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

"Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

"But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Gettysburg Address: Public Reaction & Legacy

On the day following the dedication ceremony, newspapers all over the country reprinted Lincoln’s speech along with Everett’s. Opinion was generally divided along political lines, with Republican journalists praising the speech as a heartfelt, classic piece of oratory and Democratic ones deriding it as inadequate and inappropriate for the momentous occasion.

In the years to come, the Gettysburg Address would endure as arguably the most-quoted, most-memorized piece of oratory in American history. After Lincolns’ assassination in April 1865, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts wrote of the address, “That speech, uttered at the field of Gettysburg…and now sanctified by the martyrdom of its author, is a monumental act. In the modesty of his nature he said ‘the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here; but it can never forget what they did here.’ He was mistaken. The world at once noted what he said, and will never cease to remember it.”

HISTORY Vault: The Secret History of the Civil War

The American Civil War is one of the most studied and dissected events in our history—but what you don't know may surprise you.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Analysis of a Speech , History of Public Speaking

The Gettysburg Address: An Analysis

Mannerofspeaking.

- November 19, 2010

On 19 November, we commemorate the anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in 1863.

In one of the first posts on this blog, I compared Lincoln’s two-minute address with the two-hour oration by Edward Everett on the same occasion. Today, people regard the former as one of the most famous speeches in American history; the latter largely forgotten. Indeed, Everett himself recognized the genius of Lincoln’s speech in a note that he sent to the President shortly after the event:

“I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

In a speech of only 10 sentences and 272 words, Lincoln struck a chord that would resonate through time. Why is this short speech so memorable?

First, it is important to remember the context. America was in the midst of a bloody civil war. Union troops had only recently defeated Confederate troops at the Battle of Gettysburg. It was a the turning point in the war. The stated purpose of Lincoln’s speech was to dedicate a plot of land that would become Soldier’s National Cemetery. However, Lincoln realized that he also had to inspire the people to continue the fight.

Below is the text of the Gettysburg Address, interspersed with my thoughts on what made it so memorable.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

- “Four score and seven” is much more poetic, much more elegant, much more noble than “Eighty-seven”. The United States had won its freedom from Britain 87 years earlier, embarking on the “Great Experiment”.

- Lincoln reminds the audience of the founding principles of the country: liberty and equality. In so doing, he sets up his next sentence perfectly.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.

- Here, Lincoln signals the challenge: the nation is under attack.

- He extends the significance of the fight beyond the borders of the United States. It is a question of whether any nation founded on the same principles could survive. Thus does the war — and the importance of winning it — take on an even greater significance.

We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

- Lincoln turns to recognize those who have fallen for their country.

- He uses contrast effectively. By stating “those who here gave their lives that this nation might live ” Lincoln makes what is perhaps the ultimate contrast: life vs death. Contrast is compelling. It creates interest. Communicating an idea juxtaposed with its polar opposite creates energy. Moving back and forth between the contradictory poles encourages full engagement from the audience.”

- He uses consonance — the repetition of the same consonant in short succession — through words with the letter “f”: battlefield; field; final; for; fitting.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow this ground.

- Notice the use of a “tricolon”: “can not dedicate … can not consecrate … can not hallow”. A tricolon is a powerful public speaking technique that can add power to your words and make them memorable.

- Say the sentence out loud and hear the powerful cadence and rhythm.

The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.

- This sentence is full of solemn respect for those who fought. It is an eloquent way of saying that their actions speak louder than Lincoln’s words.

- There is an alliteration: “poor power”.

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

- There is a double contrast in this sentence: “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here” / “but it can never forget what they did here.”

- Note the appeal to something larger. It is not the United States that will never forget, but the entire world.

- Ironically, Lincoln was wrong on this point. Not only do we remember his words to this day, we will continue to remember them in the future.

It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

- The final two sentence of the address sound a call to action, a resolve to complete “the unfinished work”.

- They are full of inspirational words such as “dedicated”, “nobly”, “great”, “honored”, “devotion”, “highly resolve”, “God”, “birth” and “freedom”.

- There are a couple of contrasts here: “the living ” with “the honored dead ”; and “these dead shall not have died in vain” with “this nation … shall have a new birth of freedom”.

- Earlier, Lincoln said that, in a sense, they could not dedicate the ground. Here, he tells the audience to dedicate themselves to “the unfinished work” and “the great task remaining before us”.

- He finishes with his famous tricolon: “of the people, by the people, for the people”.

In an excellent analysis of the Gettysburg Address, Nick Morgan offers an interesting perspective on Lincoln’s repetition of one word throughout the address:

And buried in the biblical phrasing there’s a further device that works unconsciously on the audience, and the reader, to weave some incantatory magic. I’ve discussed this speech many times with students, with clients, and with colleagues, and I always ask them what simple little word is repeated most unusually in the speech. No one ever spots it. …

When they look, people notice that the word ‘we’ is repeated 10 times. But that’s not unusual, or surprising, given that Lincoln was trying to rally the nation. The speech was all about ‘we’. No, what is unusual is the repetition of the word ‘here’. …

Eight times in 250 words — two minutes — Lincoln invokes the place — the hallowed ground of Gettysburg — by repeating the word ‘here’. As a result, he weaves some kind of spell on listeners, then and afterward, that is not consciously noticed, but unconsciously seems to have a powerful effect.

Repetition is an essential aspect of great public speaking. The trick is knowing what and how to repeat. Take a lesson from Lincoln. Sometimes its the little words that have the most power.

We can learn a lot about public speaking by studying the great speeches of history. The Gettysburg Address is one of the greats. Lincoln took his audience on a journey. It began with the founding of America and ended at a crossroads. He wanted to make sure that Americans chose the right path. And he did.

We might never deliver a speech or presentation that becomes as famous as the Gettysburg Address, but we can still make an impact when we speak. For a comprehensive, step-by-step overview of how to write a speech outline, please see this post .

And for a fitting conclusion to Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, enjoy this video.

Like this article?

I have read that Lincoln revised the Gettysburg Address more than 60 times. Regardless of whether or not that number is true, it’s obvious that he made every word pull its weight. Great post on this timeless speech.

Thanks, Patricia. If you click on the first link in the post, you will see that, in fact, there were different versions of the speech. I am not too familiar with the history, but it is interesting. But you are right about Lincoln making every word count. Cheers! John

Great analysis, John!

Thanks, Mel!

John – While president Lincoln’s command of the English language was impeccable, it would seem that the historical essence of his speech was much more important. That is Garry Wills’ contention in Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America (1193) — “a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Thus he relied more on the Declaration of Independence than the U.S. Constitution and made a bridge with European liberalism by using Giuseppe Mazzini’s words “the government of the people, by the people, for the people”. Cheers, Osvaldo

Osvaldo, thanks very much for the additional historical perspective. Very interesting indeed. It is a testment to Lincoln that he was able to draw on history and blend it seemlessly with the solemnity of the occasion to create such a masterpiece of a speech. Cheers! John

Again, a wonderful analysis. Contrast is such a strong idea, and Lincoln’s use of “We” does, too. A century and many score years later, Neuharth exploited to power of that word when he gave the world USA Today. “We” appeals to audience members, and readers.

Thanks for the comment, Harry. You’re right – “we” makes the audience feel like they are part of the story, part of the message, part of the solution.

Great analysis! It would help me to do my, study the “state of the Nation Address: an analysis” it gave me the idea. Thank you, Sir John Zimmer. I hope that you could do more analysis from different literature so that many students learn from you.

Thank you for the comment, Lileth. I am glad that you enjoyed the analysis. If you are looking for other speech analyses, you might find something useful at this link: http://mannerofspeaking.org/speech-analyses/ Regards, John

This should be read and seen every day to remind America what their fathers fought for, black and white .

Thank you for the comment, Carol.

Have you got any analysis and spoken language studies of President Obama’s Inaugral Address? If you haven’t I would be so happy and grateful if you could do one.

Hi Ali. Thank you for the comment and suggestion. I have not analyzed any of Barack Obama’s speeches, but have noted your idea and will certainly consider it for the future.

John, President Obama began using Lincoln’s Euclidean system for structuring his speeches in January, 2011, shortly after “Abraham Lincoln and the Structure of Reason” was published. We have a second book coming out analyzing numerous speeches by President Obama, demarcating them into the six elements of a Euclidean proposition. “Barack Obama, Abraham Lincoln, and the Structure of Reason”, published by Savas Beatie. This book will be out shortly in eBook format. Dan Van Haften

Thanks, Dan. I’ll be sure to have a look. John

Thanks so much! This really helped me with my literature homework.

Glad to hear it, Jen. Thanks for the comment.

There is a hidden structure to Abraham Lincoln’s speeches, including the Gettysburg Address. Lincoln used the structure of ancient Euclidean propositions. These contain six distinct elements, an enunciation (with a given and sought), an exposition, a specification, a construction, a proof and a conclusion. This discovery is described in a book I co-authored, “Abraham Lincoln and the Structure of Reason”.

Dan, thanks very much for sharing this insight with us. I was completely unaware of Lincoln’s fascination with Euclidean geometry. But your comment prompted me to do some digging and I came up with this anecdote from Lincoln himself:

“In the course of my law reading I constantly came upon the word “demonstrate”. I thought at first that I understood its meaning, but soon became satisfied that I did not. I said to myself, What do I do when I demonstrate more than when I reason or prove? How does demonstration differ from any other proof? “I consulted Webster’s Dictionary. They told of ‘certain proof,’ ‘proof beyond the possibility of doubt’; but I could form no idea of what sort of proof that was. I thought a great many things were proved beyond the possibility of doubt, without recourse to any such extraordinary process of reasoning as I understood demonstration to be. I consulted all the dictionaries and books of reference I could find, but with no better results. You might as well have defined blue to a blind man. “At last I said: Lincoln, you never can make a lawyer if you do not understand what demonstrate means; and I left my situation in Springfield, went home to my father’s house, and stayed there till I could give any proposition in the six books of Euclid at sight. I then found out what demonstrate means, and went back to my law studies.”

Thanks again for sharing this insight. Your book is now on my “to read” list. Cheers! John

John, The story about Lincoln wanting to learn what it means to demonstrate (and many more stories) are in our book. Thanks, Dan

Hi Dan. I knew that you would, of course, be familiar with the story but found it so interesting that I figured other readers would as well. I am looking forward to reading your book. Regards, John

John, Our new book, “Barack Obama, Abraham Lincoln, and the Structure of Reason”, was just released our publisher, Savas Beatie. This book shows how President Obama is using Lincoln’s Euclidean system to structure his speeches. The book is currently available as an eBook on Kindle and iBook, and soon will be available on the other digital platforms. Kindle: http://www.amazon.com/Barack-Abraham-Lincoln-Structure-ebook/dp/B008AKOFOO/ref=la_B0043H0XNA_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1339641707&sr=1-2 IBook: http://itunes.apple.com/us/book/barack-obama-structure-reason/id535241124?mt=11

Congratulations on the book release, Dan. John

Thanks for the analysis. This helps with my oral comm speeches! 🙂

Thank you for the comment, Violet. Glad the post helped and good luck with your speeches! John

While all of these assessments of Lincoln’s speech are clearly good ones, allow me to throw a wrench in the works. Has anyone ever considered why the country was fighting against itself, and further more does anyone feel that there is a reflection on the word “we” in Lincoln’s speech for all men. Including men and women that were bound by the institution of slavery. Lincoln was an abolitionist, and the very fact that he gave this speech on the border of slavery seems very interesting to me. “…all men are created equal”, really gets my wheels spinning. You know that Frederick Douglas and Lincoln were friends, the North would not have won this battle without the use of African American men fighting in their armies. Would love to hear some input about my random thoughts. Mike

Thanks for the comment, Mike. You raise important issues, but ones that go well beyond the focus of this blog. I’m not quite sure I understand what you mean by “a reflection on the word ‘we’ in Lincoln’s speech”, but going through the speech again, it seems to me that the “we” changes depending on the sentence. Sometimes “we” refers to the entire country; sometimes it refers to the people who were gathered at Gettysburg; sometimes it refers to those finding against slavery and the South. I do know that many African Americans did fight in the war (and I recall the movie “Glory” was about the first all-black regiment). I also know that there is still some debate over Lincoln’s response to the issue of emancipation, but my knowledge of American Civil War history is not good enough for me to express an educated opinion. Others may feel free to weigh in. Regards, John

For a little more information on slavery and abolitionism, I would like to point out that this speech and the Civil War would not have been necessary if the founding fathers had not removed the abolition of slavery from the Declaration of Independence. Not many people know that the Declaration was delayed because certain signers would not sign until the abolition of slavery was removed from the writing. Sad, but true.

Hope this helps a little,

Hi Terri. Thanks for sharing that bit of history. I did not that about the Declaration of Independence. Do you happen to know which founding fathers held out until the provision was removed? John

Thanks John, for such a detailed analysis! It has certainly gave me a new perspective of the address, as it was indeed, very helpful in my research. But more importantly, I have began to realize what a great influence the speech had on history. For example, before he gave the address people saw it as “The United States are a free goverment,” but now it is “The United States is a free goverment”. I’m doing a project called National History Day. People from all across the country compete at different levels, nationals being in D.C. The theme for this year is “Turning Points in History” and this is my thesis statement for my documentary. Garry Wills’ Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America has provided me with a great deal of information and I highly recommend it you. Lawson P.S. Sorry for the poor structure of my comment, I’m only in sixth grade.

Dear Lawson, Thank you very much for the thoughtful (and well structured!) comment. It is great to see young people such as yourself taking an interest in subjects such as Lincoln’s address and the historical context in which it was given. It bodes well for the future. I wish you the best of success in the competition and hope that you make it to Washington, D.C. Cheers! John Zimmer

Great analysis of the speech!

Thank you for such a detailed and comprehensive stylistic analysis of this speech, Mr. John. It was extremely helpful, as I have picked up this speech as the main primary text for a further oral activity in school. Your analysis has helped me to a great extent; thanks once more. Shaiv

Dear Shaiv, Thank you for the message. I am glad that you found the post helpful and wish you all the best with your studies. Regards, John

Thank you so soooo much for having such a detailed and good analysis of this speech! 🙂 It did help me with my report very well. I just wanted to tell you thank you thank you thank you!!!!!!!! You’re a lifesaver! I will be looking forward to your reply. Thank you Thank you Thank you! May GOD Bless you and your Family! Thanks again! Love, Adriana P.S. sorry for not having so many big advanced words I’m only in 7th grade Thanks again!

Dear Adriana, You’re welcome you’re welcome, you’re welcome! 🙂 I am glad that you found the post helpful. Thank you for stopping by to leave a comment. And don’t worry about not using “big advanced words”. Too many people try to use too many fancy words and it just makes their message more difficult to understand. When you write and when you speak, it is good to use a big word from time to time; however, for the most part, stick to the simple words. As Winston Churchill said, short words are the best words. Best of luck with your studies. John Zimmer

Thanks so much for your reply! p.s. (Don’t take offense of this question just curious) Do you speak Spanish? It would kinda be cool if you did because I do 🙂 BTW I made an A on my report thanks to you! I’ll be looking fwd to your reply! Love, Adriana peace, Love <3, Happiness :-), plus +, Star Paz, Amor, Felizidad, y, estrella!!!!!

Hi Adriana, Lo siento. No hablo muy bien espagnol. Congratulations on your report. Best regards, John Zimmer

Thanks! 🙂 I’m glad you replied thanks again! God Bless you and your family! love, Adriana p.s. its ok if you dont know spanish you might on the other hand know some other language and i respect that:-) alright bye!

Thank you so much for this detailed analysis! I have gone through many people’s analysis of The Gettysburg Address, yet none have been as helpful. I admire how you extracted effective public speaking techniques from the interpreptations of the words in this famous speech. My english assignment seemed like a piece of cake after reading this! Thanks again!

Thank you very much for the kind words about the post, Noor. I am glad that you found it helpful. Best of luck with the rest of your English, and other classes. John Zimmer PS – I’ve always liked the name Noor. I know that it means “Light”. (Atakelemu al arabiya. Qalilaan.)

Mr. John I agree with all the complements people had given you. I have a quick question, do you think the thesis of this speech is the first sentence? Thank you. Savi

Dear Savi, Thank you for the comment and the kind words. You pose an interesting question. Because the speech is so short, every sentence has great significance. In the first sentence, Lincoln reminds the audience of the principles on which the United States was founded. However, it is the final sentence that is the real call to action and, as you put it, the “thesis” of the speech. That sentence — and it is a long one — is as follows: “It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” Kind regards, John

What an interesting analysis on the Gettysburg Address! You seem to have taken heed to some unique points, such as the contrasting. and when the President says ‘world’ instead of our country. There’s definitely a lot more power and just over-all inspiring things to learn from Lincoln’s speech now that it’s been elaborated so finely. Similar to one of your reviewers, I was looking for a new way to view this address for an English assignment, as I was definitely looking at in black and white. I felt I wasn’t grasping all that there was so wisely embedded into it, but I’m glad that I had found this. Hopefully I can build off of your interpretation and further admire the Gettysburg Address.

Dear Annie, Thank you for the kind comment. I am glad that you found the post useful. I have no doubt that you (and others) can find more that it good about the Gettysburg Address. All the best, John

Dear John, Thank you so much for this detailed information. It really helped on my English assignment. 🙂 Nallely

Dear Nallely, Thank you for the comment. I am glad that the post helped you with your assignment. All the best for the rest of the school year. John

Great piece, John! This is very helpful. I’m a lover of great speeches!

Thanks very much for the comment and also for referencing my post on your blog. Thank you also for introducing me to the cyclorama. I had not heard of it before and I watched a video of it on YouTube. Truly impressive! John

Dear John, I just wanted to thank you for your speaking points and thoughts. Curiously enough, I am a criminal defense attorney in Los Angeles, California. While I have employed several of the tactics and forces that you discuss in your article, I have never seen them explained so well. Whether to a jury, judge, or prosecutor; I try to employ the methodology you describe and highlight with your eyesight. I think I just used some of your and Lincoln’s method. In any case, thank you for your concise evaluation of a pretty special speech. Yours, Andy

Andy, I very much appreciate your comments as I too am a lawyer. When I was practicing law in Canada, I found that judges appreciated eloquence but not verbosity, passion but not theatrics. And they especially liked it when barristers could cut through reams of evidence and present a simple, cogent argument on the key points. (They also liked it when lawyers had a bit of a sense of humour and would show their humanity.) The best presentation skills, in my view, are still the ones that have been handed down through the centuries. Thanks again and good luck with your cases. John

Hi sir. I have my oration presentation in my english class, can i use gettysburg address? If so, how can i perform it? I mean. Is there a body gestures or action? Or just simply standing while reciting? Thanks ahead. -Padate