Precolonial Period in the Philippines: 18 Facts You Need To Know

While Filipinos nowadays are pretty knowledgeable about the Spanish, American, and Japanese eras, the same cannot be said regarding the precolonial period in the Philippines. This is a shame because even before the three foreign races came, our ancestors lived in a veritable paradise.

Also Read: 15 Most Intense Archaeological Discoveries in Philippine History

Although it wasn’t perfect, that era was the closest thing we ever had to a Golden Age, a sentiment shared by national hero Jose Rizal, members of the Katipunan, noted historian Teodoro Agoncillo, and even some church historians.

Let’s look at some of the most interesting facts about the precolonial period in the Philippines and compelling reasons why we think life was better during this period in our nation’s history.

Table of Contents

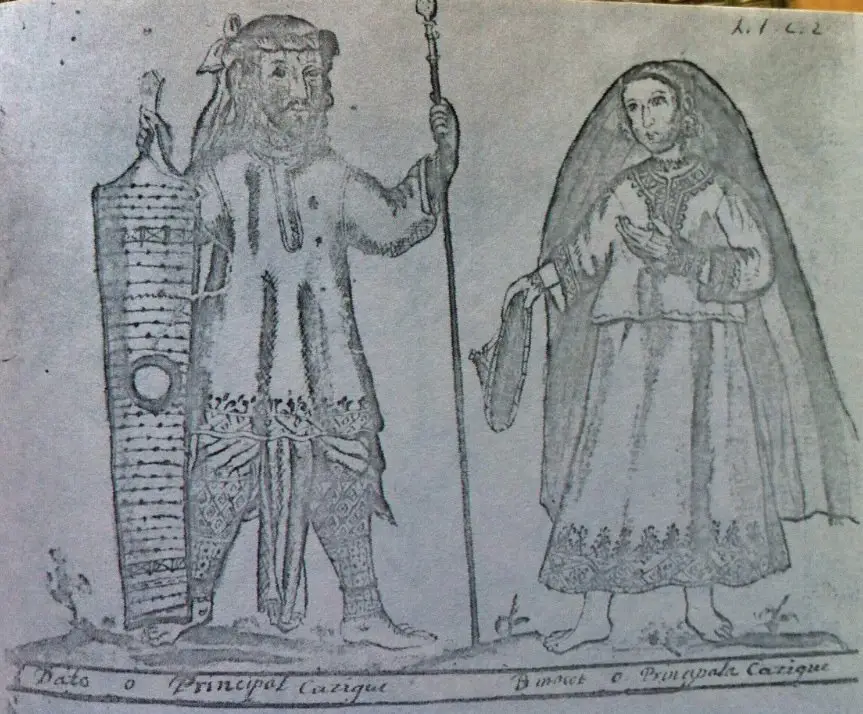

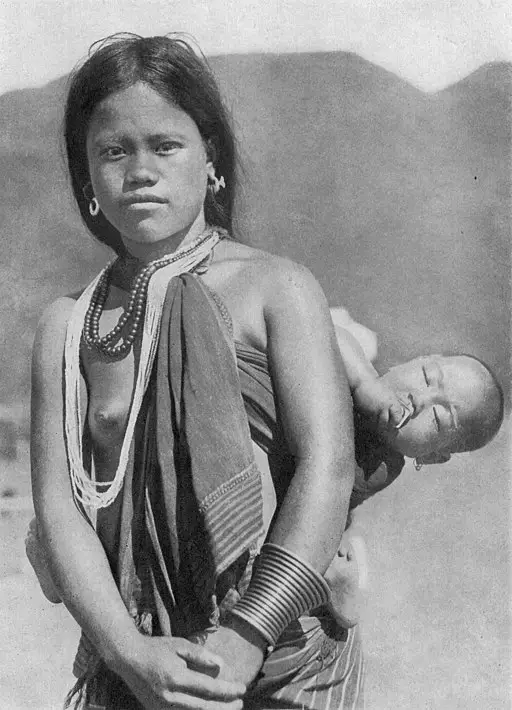

1. women enjoyed equal status with men.

During pre-colonial times, women shared equal footing with men in society. They were allowed to divorce, own and inherit property, and even lead their respective barangays or territories.

In matters of family, the women were the working heads, possessing the power of the purse and the sole right to name their children. They could dictate the terms of their marriage and even retain their maiden names if they chose to do so.

During this time, people traced their heritage to their fathers and mothers. It could be said that the precolonial period in the Philippines was largely matriarchal, with the opinions of women holding a significant weight in matters of politics and religion (they also headed the rituals as the babaylans ).

As a show of respect, men were even required to walk behind their wives. This largely progressive society that elevated women to such a high pedestal took a serious blow when the Spanish came. Eager to impose their patriarchal system, the Spanish relegated women to the homes, demonized the babaylans as satanic, and ingrained into our forefathers’ heads that women should be like Maria Clara —demure, self-effacing, and powerless.

2. Society Was More Tolerant in Pre-Colonial Philippines

While it could be said that our modern society is one of the most tolerant in the world, we owe our open-mindedness not to the Americans and certainly not to the Spanish but to the pre-colonial Filipinos.

Sexuality was not as suppressed, and no premium was given to virginity before the marriage. Although polygamy was practiced, men were expected to do so only if they could support and love each of their wives equally.

Homosexuals were also largely tolerated, as some babaylans were men in drag.

Back then, there were no doctors or priests our ancestors could turn to when things went awry. Their only hope was a spirit medium or shaman who could directly communicate with the spirits or gods . They were known in the Visayas as babaylan, while the Tagalogs called them catalonan ( katulunan ).

Also Read: The first same-sex marriage in the Philippines

More often than not, these babaylans or catalonans were women who came from prominent families. However, early Spanish missionaries reported men who assumed the role of a babaylan. That also suggests that these male versions may have existed long before the Spaniards arrived.

What’s more surprising is that some of these male babaylans dressed and acted like women . Visayans called them asog while the Tagalogs named them bayugin. In the 1668 book Historia de los Islas y Indios de Bisayas, Father Francisco Alcina further described an asog as:

“…impotent men and deficient for the practice of matrimony, considered themselves more like women than men in their manner of living or going about, even in their occupations….” The 16th-century manuscript Boxer Codex added even more intriguing details:

“The bayog or bayoguin are priest dressed in female garb……Almost all are impotent for the reproductive act, and thus they marry other males and sleep with them as man and wife and have carnal knowledge .”

As time passed, the term asog has taken on completely different meanings. In Aklan, for example, asog is now used to refer to a tomboy or a woman acting like a man.

Surprisingly, with the amount of sexual freedom, no prostitution existed during the pre-colonial days. Some literature suggests that the American period—which heavily emphasized capitalism and profiteering—introduced prostitution into the country on a massive scale.

3. The People Enjoyed a Higher Form of Government

The relationship between the ruler and his subjects was straightforward back then: In return for his protection, the people paid tribute and served him in times of war and peace.

Going by the evidence, we could say that our ancestors already practiced an early version of the Social Contract , a theory by prominent thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, which espoused the view that rulers owe their right to rule based on the people’s consent.

Conversely, if the ruler became corrupt or incompetent, the people had a right to remove him. And that’s precisely the kind of government our ancestors had. Although the datus technically came from the upper classes, he could be removed from his position by the lower classes if they found him wanting of his duties. Also, anyone (including women) could become the datu based on their merits, such as bravery, wisdom, and leadership ability.

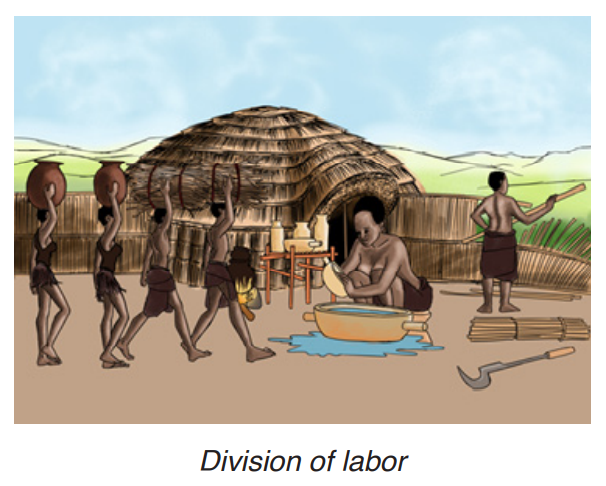

4. We Were Self-Sufficient

In terms of food, our forefathers did not suffer from any lack thereof. Blessed with such a resource-rich country, they had enough for themselves and their families.

Forests, rivers, and seas yielded plentiful meat, fish, and other foodstuffs. Later on, their diet became more varied, especially when they learned to till the land using farming techniques that were quite advanced for their time. The Banaue Rice Terraces are one such proof of our ancestors’ ingenuity.

READ: 7 Prehistoric Animals You Didn’t Know Once Roamed The Philippines

What’s more, they already had an advanced concept of agrarian equity. Men and women equally worked in the fields, and anyone could till public lands free of charge. Also, since they had a little-to-no concept of exploitation for profit, our ancestors generally took care of the environment well.

Such was the abundance of foodstuffs that Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, the most-successful Spanish colonizer of the islands, was said to have reported the “abundance of rice, fowls, and wine, as well as great numbers of buffaloes, deer, wild boar, and goats” when he first arrived in Luzon.

5. Gold Was Everywhere

There was plenty of gold in the islands during the precolonial period in the Philippines, and it used to be part of our ancestors’ everyday attire.

In the book by historian William Henry Scott, it was said that a “Samar datu by the name of Iberein was rowed out to a Spanish vessel anchored in his harbor in 1543 by oarsmen collared in gold; while wearing on his own person earrings and chains .”

Much of the gold artifacts recovered in the country are believed to have come from the ancient kingdom of Butuan, a major center of commerce from the 10th to the 13th century. Ancient Indian texts also suggest that merchant ships used to trade with people from what they called Survarnadvipa or “Islands of Gold,” believed by many as present-day Indonesia and the Philippines.

Related Article: Pinoy chef made the world’s most expensive sushi! – Covered with gold, diamonds

Precolonial treasures include ear ornaments called panika; bracelets known as kasikas; and the spectacular serpent-like gold chain called kamagi. Since their discovery, some of these valued gold artifacts have been looted, melted, and sold.

It didn’t matter to the treasure hunters that these gold ornaments were originally part of our ancestors’ bahandi (heirloom wealth) and probably originated here and in other places they traded with.

6. We Had Smoother Foreign Relations

We’ve all been taught that before the Spanish galleon trade, the pre-colonial Filipinos had already established trading and diplomatic relations with countries as far away as the Middle East.

Instead of cash, our ancestors exchanged precious minerals, manufactured goods, etc., with Arabs, Indians, Chinese, and other nationalities. Many foreigners permanently settled here during this period after marveling at the country’s beauty and people.

Out of the foreigners, the Chinese were most amazed at the pre-colonial Filipinos, especially regarding their extraordinary honesty. Chinese traders often wrote about the Filipinos’ sincerity and said they were one of their most trusted clientele since they did not steal their goods and always paid their debts.

Out of confidence, some Chinese were known to leave their items on the beaches to be picked up by the Filipinos and traded inland. When they returned, the Filipinos would give them back their bartered items without anything missing.

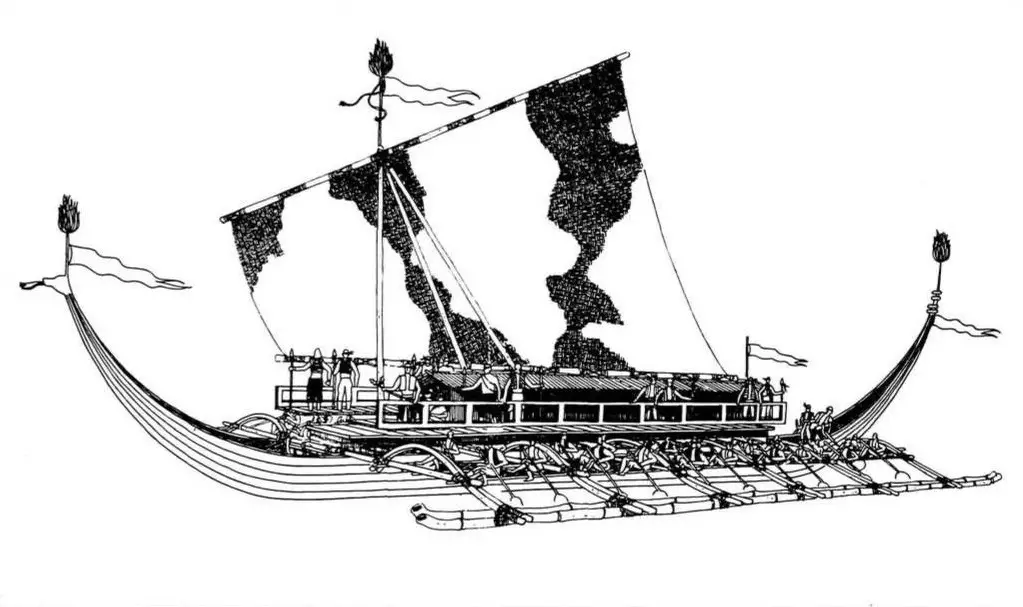

7. We Built Warships That Could “Sail Like Birds”

They may be primitive, but our ancestors made the most of what they had and created amazing marine architecture. The Visayan warship karakoa was the result of such ingenuity.

Note that our early plank-built vessels were made in the same tradition as other boats dating back to 3rd century BCE. And that probably explains why our karakoa is similar to Indonesia’s korakora.

In his paper “Boat-Building and Seamanship in Classic Philippine Society,” historian William Henry Scott described the karakoa as “ sleek, double-ended warships of low freeboard and light draft with a keel on one continuous curve…… and a raised platform amidships for a warrior contingent for ship-to-ship contact.”

The karakoa served not only as a warship but also as a trading vessel. Accounts from the 1561 Legazpi expedition described it as “a ship for sailing any place they wanted.”

And sailed they did, reaching places as far as Fukien coast in China where a bunch of Visayan pirates pillaged the villages sometime in the 12th century.

The flexibility of its plank-built hull and the coordination of a hundred or so paddlers all helped karakoa generate its best speed of 12 to 15 knots–three times the speed of a Spanish galleon. It was so efficient that Fr. Francisco Combés once wrote it could “ sail like birds.”

8. Our Forefathers in the Pre-Colonial Philippines Already Possessed a Working Judicial and Legislative System

Although not as advanced (or as complicated) as our own today, the fact that our ancestors already possessed a working judicial and legislative system shows that they were well-versed in the concept of justice.

Life in the pre-colonial Philippines was governed by a set of statutes, both unwritten and written, and contained provisions concerning civil and criminal laws. Usually, it was the datu and the village elders who promulgated such laws, which were then announced and explained to the people by a town crier called the umalohokan .

Related Article: 9 Philippine Government Agencies That Need To Reform Right Now

The datu and the elders also acted as de facto courts in case of disputes between individuals of their village. In the case of inter-barangay disputes, a local board composed of elders from different barangays would usually act as an arbiter.

Penalties for anyone guilty of a crime include censure, fines, imprisonment, and death. As we’ve said, the system was imperfect, but it worked.

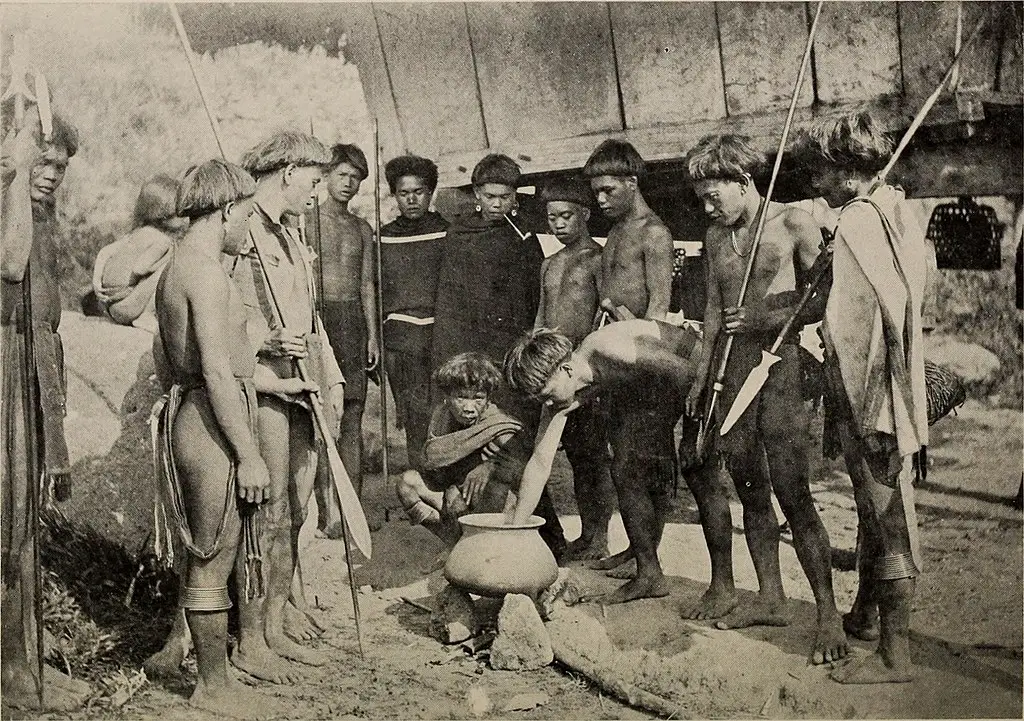

Tortures and trials by ordeal during this time were also common. You may have encountered “trial by ordeal” while reading stories from medieval Europe. It’s a method of judgment wherein an accused party would be asked to do something dangerous. If he luckily survives, he would be considered innocent. Otherwise, he would be proclaimed guilty.

Our ancestors–and even some of today’s indigenous peoples–had a similar custom. The difference is that our version didn’t usually end up in a life-or-death situation.

READ: 6 True Stories From Philippine History Creepier Than Any Horror Movie

The Ifugao, for example, subjected the involved parties to either a “hot water” or “hot bolo” ordeal. The former involved dropping pebbles in a pot filled with boiling water. The accused was then asked to dip his hands into the pot and remove the stones. Failure to do this or doing it with “undue haste” would be interpreted as a confession of guilt.

As the name suggests, the “hot bolo” ordeal required both suspects to have their hands touched by a scorching knife. The one who suffered the most burns would be declared guilty.

Other methods included giving lighted candles to the suspects; the guilty party was the one whose candle died off first. There’s also one which asked both persons to chew rice and later spit it out, the guilty person being the one who spits the thickest saliva.

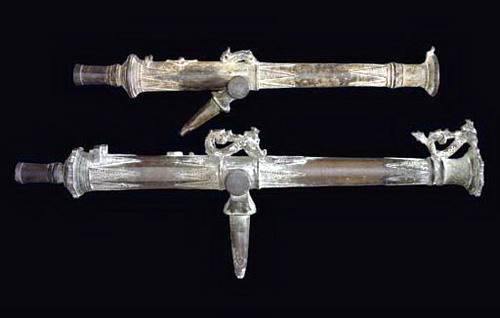

9. They Had the Know-How To Make Advanced Weapons

Our ancestors—far from being the archetypal spear-carrying, bahag -wearing tribesmen we picture them as— were proficient in war. Aside from wielding swords and spears, they also knew how to make and fire guns and cannons. Rajah Sulayman, in particular, was said to have owned a huge 17-foot-long iron cannon.

Aside from the offensive weapons, our ancestors also knew how to construct massive fortresses and body armor. For instance, the Moros living in the south often wore armor that covered them head-to-toe. And yes, they also carried guns with them.

With all these weapons at their disposal and the fact that they were good hand-to-hand combatants, you’d think that the Spanish would have had a more challenging time colonizing the country. Sadly, the Spanish cleverly exploited the regionalist tendencies of the pre-colonial Filipinos. This divide-and-conquer strategy would be the primary reason why the Spanish successfully controlled the country for more than 300 years.

10. Several Professions Already Existed

Aside from being farmers, hunters, weapon-makers, and seafarers, the pre-colonial Filipinos also dabbled—and excelled—in several other professions.

To name a few, many became involved in such professions as mining, textiles, and smithing. Owing to the excellent craftsmanship of the Filipinos, locally-produced items such as pots, jewelry, and clothing were highly-sought in other countries. It is reported that products of Filipino origin might have even reached as far away as ancient Egypt. Clearly, our ancestors were very skilled artisans.

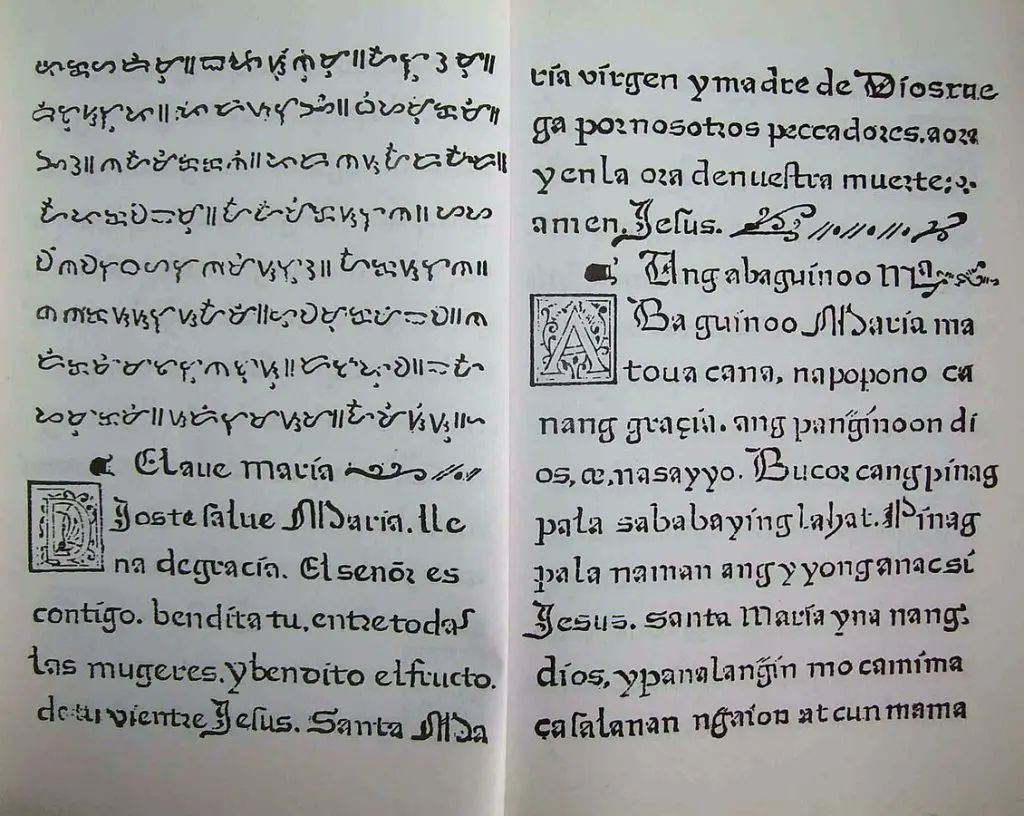

11. We Had Our Own Writing System

Using the ancient system of writing called the baybayin , the pre-colonial Filipinos educated themselves very well, so much so that when the Spanish finally arrived, they were shocked to find out that the Filipinos possessed a literacy rate higher than that of Madrid!

Father Chirino observed that there is “hardly a man, and much less a woman, who does not read and write,” while Morga wrote that there were very few who “do not write it (baybayin) very well and correctly.”

The baybayin is believed to be one of the indigenous alphabets in Asia that originated from the Sanskrit of ancient India.

Composed of 17 symbols, the ancient baybayin has survived in a few artifacts and Father Plasencia’s Doctrina Christiana en lengua Española y Tagala, the only example of the baybayin from the 16th century.

As to why the baybayin quickly disappeared, there are a few possible reasons. First, we were unlike China, which was miles ahead in writing and record-keeping. Instead, our ancestors used anything they could get their hands on as their writing pad (leaves, bamboo tubes, the bark of trees, you name it), while pointed weapons or saps of trees served as their ink.

The Boxer Codex also suggests that the content of whatever our ancestors wrote was relatively insignificant: “They have neither books nor histories nor do they write anything of any length but only letters and reminders to one another.”

Of course, the Spaniards also contributed to the early death of our ancient syllabic writing. Historian Teodoro Agoncillo believed so: “Aside from the destructive work of the elements, the early Spanish missionaries, in their zeal to propagate the Catholic religion, destroyed many manuscripts on the ground that they were the work of the Devil himself.”

12. They Compressed Their Babies’ Skulls for Aesthetic Reasons

In the ancient Visayas, being beautiful could be as simple as having a flat forehead and nose. But since humans are not usually born with these features, the Visayans used a device called tangad to achieve them.

The tangad was a comb-like set of thin rods that was put above the baby’s forehead, surrounded by bandages, and fastened at some point behind. Babies’ skulls are the most pliable, so this continuous pressure often results in elongated heads.

Some of these deformed skulls were recovered from various burial grounds in the Visayan region. Two are on display today at the Aga Khan Museum in Marawi.

Upon close examination of these skulls, it was also discovered that their shape varies depending on whether the pressure was applied between the forehead and the upper or lower part of the occiput (i.e., back of the skull). Hence, some had “normally arched foreheads but were flat behind, others were flattened at both front and back, and a few were asymmetrical because of uneven pressure.”

13. You Could Judge How Brave a Man Was by the Color of His Clothes

Clothing in the pre-colonial Philippines reflected one’s social standing and, in the case of men, how many enemies they had killed.

In the Visayas, for example, basic clothing included bahag (G-string) for men and malong (tube skirt) for women. The material used to make these clothes could indicate the wearer’s social status, with the abaca being the most valued textile reserved for the elites.

READ: The Controversial Origin of Philippines’ National Costume

The Visayan bahag was slightly larger than those worn by present-day inhabitants of Zambales, Cordillera, and the Cagayan Valley. They usually had natural colors, but warriors who personally killed an enemy could wear red bahag.

The same rule applied to the male headdress called pudong. Red was and still is the symbol of bravery, which explains why the most prolific warriors at that time proudly wore red bahag and pudong .

Historian William Henry Scott writes:

“A red ‘pudong’ was called ‘magalong’, and was the insignia of braves who had killed an enemy. The most prestigious kind of ‘pudong,’ limited to the most valiant, was, like their G-strings, made of ‘pinayusan,’ a gauze-thin abaca of fibers selected for their whiteness, tie-dyed a deep scarlet in patterns as fine as embroidery, and burnished to a silky sheen. Such pudong were lengthened with each additional feat of valor: real heroes therefore let one end hang loose with affected carelessness.”

14. Human Sacrifice Was a Bloody, Fascinating Mess

It’s not easy to be a slave in the ancient Philippines. When a warrior died, a slave was traditionally tied and buried beneath his body. If one was killed violently or if someone from the ruling class died (say, a datu ), human sacrifices were almost always required.

Father Juan de Plasencia, an early missionary who authored “Relacion de las Costumbres de Los Tagalos” in 1589, provided us with a vivid portrait of an ancient burial:

“Before interring him (the chief), they mourned him for four days; and afterward laid him on a boat which serve as a coffin or bier….. If the deceased had been a warrior, a living slave was tied beneath his body until in this wretched way he died .”

Sometimes, as a last resort, an alipin was sacrificed in the hope that the ancestor spirits would take the slave instead of the dying datu. The slave could be an atubang or a personal attendant who had accompanied the datu all his life. The prize of his loyalty was often to die in the same manner as his master. So, if the datu died of drowning, the slave would also be killed by drowning. This is because of onong or the belief that those who belonged to the departed must suffer the same fate.

Related Article: Rare ritual burial may reveal cannibalistic ancestry .

Slaves from foreign lands could also be sacrificed. An itatanun expedition had the intention of taking captives from other communities. After being intoxicated, these captives would then be killed in the most brutal ways. Pioneer missionary Martin de Rada reported one case in Butuan wherein the slave was bound to a cross before being tortured by bamboo spikes, hit with a spear, and finally thrown into the river.

They believed that the dying datu was being attacked by the spirits of men he once defeated, and the only way to satisfy the ancestors was to kill a slave.

15. It Was Considered a Disgrace for a Woman To Have Many Children

There was no “family planning” in the pre-colonial Philippines. Everything they did was based on existing customs and beliefs, one of which was that having many children was undesirable and even a disgrace.

Such was their fear of having more children that pregnant women were prohibited from eating kambal na saging or similar food. They believed eating it would cause them to give birth to twins, which greatly insulted them .

Almost everyone also practiced abortion. The Boxer Codex reported that it was done with the help of female abortionists who used massage, herbal medicines, and even a stick to get the baby out of the womb.

READ: 10 Shocking Old-Timey Practices Filipinos Still Do Today

For others, having multiple children made them feel like pigs, so pregnant women with their second or third child would resort to abortion to get rid of their pregnancy. Poverty was another reason, as reported by Miguel de Loarca: “….when the property is to be divided among all the children, they will all be poor, and that it is better to have one child and leave him wealthy.”

According to historian William Henry Scott, the Visayans also had a custom of abandoning babies with debilitating defects, which made many observers conclude that “Visayans were never born blind or crippled.”

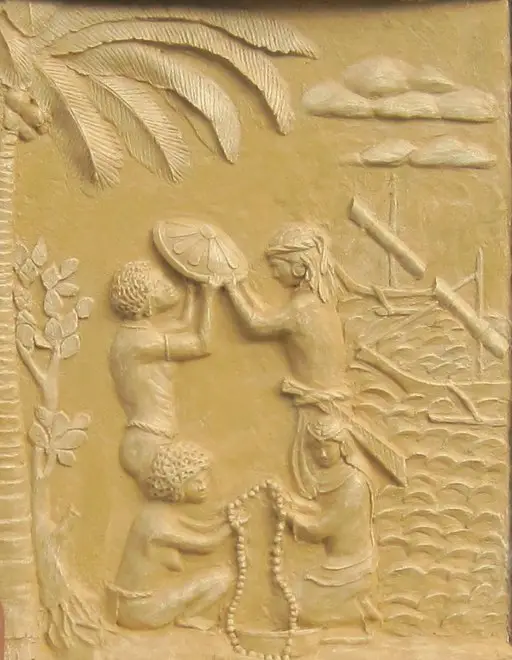

16. Celebrating a Girl’s First Menstruation, Pre-Colonial Style

Although menarche (first menstruation) is memorable for many women today, it rarely becomes a cause for celebration. In the precolonial era, however, this transition was seen as a crucial period in womanhood, so much so that all girls were required to go through an elaborate rite of passage.

The said ceremony was known as “dating” among ancient Tagalogs. It was usually held with the help of a catalonan ( babaylan ), the go-to priestess-cum-doctor at that time. During the ritual, the girl having her first period was secluded, covered, and blindfolded.

Isolation usually lasted four days if the woman was a commoner, while those belonging to the principal class had to go through this process for as long as a month and twenty days!

The Boxer Codex explains that our ancestors blindfolded the girl so she wouldn’t see anything dishonest and prevent her from growing up a “bad woman. ” The mantles covering her, on the other hand, shielded her from wind blows, which they believed could lead to insanity.

The girl was prohibited from eating anything apart from two eggs or four mouthfuls of rice–morning and night, for four straight days. As if that’s not enough, the girl was also not allowed to talk to anybody for fear of becoming talkative. All of these, while her friends and relatives feasted and celebrated.

Also Read: 35 Outrageous Filipino Superstitions You Didn’t Know Existed

Each morning throughout the ceremony, the blindfolded girl was led to the river for her ritual bath. Her feet couldn’t touch the ground, so a catalonan or a male helper assisted her. The girl would be either led to the river through an “elevated walkway of planks” or carried by a male helper on his shoulder.

After immersing eight times in the water, the girl was carried back home where she would be rubbed with traditional male scents like civet or musk. Father Placensia, who witnessed the ritual, discovered later that the natives did this “ in order that the girl might bear children, and have fortune in finding a husband to their taste , who would not leave them widows in their youth.”

17. Social Classes Were Not As Permanent as We Thought

When the ancient Filipinos started trading with outsiders, the economy also started to improve. This was when social classes emerged, and life suddenly became unfair.

As you may recall from the HEKASI subject that bored you as a kid, there existed four classes of pre-colonial Filipinos: There was the ruling datu class; the wealthy warrior class called maharlika; the timawa or freemen; and the most ‘unfortunate’ of them all–the alipin or uripon class.

Also Read: 11 Things From Philippine History Everyone Pictures Incorrectly

The alipin was divided into two sub-classes: the namamahay or those who owned their houses and only served their masters on an as-needed basis; and the saguiguilid who didn’t own a thing nor enjoyed any social privileges.

You might think being born a slave then was tantamount to being doomed for life. However, that’s not the case, as there were reports of those who moved up or down the pre-colonial social ladder.

In the case of the alipin, he could improve his social status by marriage. For example, as recorded by Father Plasencia, “if the maharlikas had children by their slaves, the children and their mothers became free.” Of course, this thing didn’t happen all the time, neither was it applicable to all social classes.

An alipin could also buy his freedom from his master if he were lucky enough to obtain gold through “war, by the grade of goldsmith, or otherwise.” However, note that inter-class mobility could only happen one step at a time. In other words, an alipin could never bypass other classes to become a datu overnight, and vice versa.

Other classes could also be demoted to the slave class for various reasons. Save for the datu or chiefs, anyone who committed a crime and failed to pay the fine would become a slave.

As for the datu, he could end up a low-ranked individual either because of poor leadership, which would prompt his followers to abandon him, or through an inter- barangay war, during which the captured and defeated datu , as well as his family, would lose some of their social privileges.

18. Courtship Was a Long, Arduous, and Expensive Process

Paninilbihan, or the custom requiring the guy to work for the girl’s family before marriage, was already prevalent during the pre-colonial period in the Philippines. From chopping wood to fetching water, the soon-to-be-groom would do everything to win his girl’s hand.

READ: The bizarre, painful sexual practices of early Filipinos

It often took months or even years before the parents were finally convinced that he was the right man for their daughter. And even at that point, the courtship wasn’t over yet.

The man was required to give bigay-kaya, or a dowry in the form of land, gold, or dependents. Of course, he needed the help of his parents to raise the required amount. Spanish chronicler Father Plasencia reported that a bigger dowry was usually given to a favored son, especially if he was about to tie the knot with the chief’s daughter. In the case of the Visayans, this dowry was usually given to the father-in-law, who would not entrust it to the couple until they had children.

Also Read: A Photo Of Ifugaos in Wedding Dress (1900)

In other areas of the country, the dowry was just the beginning. According to historian Teodoro Agoncillo, there was also the panghimuyat or the payment for the “mother’s nocturnal efforts in rearing the girl to womanhood” ; the bigay-suso or payment for the girl’s wet nurse (if there’s any) who breastfed her when she’s still a baby; and the himaraw or the “reimbursement for the amount spent in feeding the girl during her infancy.”

As if that’s not enough to make the would-be groom go bankrupt, there was also the sambon among the Zambals which was a “bribe'” given to the girl’s relatives. Fortunately, through a custom called pamumulungan or pamamalae , the groom’s parents had the chance to meet the in-laws, haggle all they could, and make the final arrangements before the marriage.

Agoncillo, T. (1990). History of the Filipino People (8th ed.). Quezon City: C & E Publishing, Inc.

Burton, R. (1919). Ifugao Law. American Archaeology And Ethnology , 15 (1).

Carpio, A. (2014). Historical Facts, Historical Lies, And Historical Rights In The West Philippine Sea (1st ed., pp. 8-9).

Geremia-Lachica, M. (1996). Panay’s Babaylan: The Male Takeover. Review Of Women’s Studies , 6 (1), 54-58.

Jocano, F. (1998). Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage . Punlad Research House.

Junker, L. (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms . University of Hawaii Press.

Philippine Gold: Treasures of Forgotten Kingdoms . (2015). Asia Society . Retrieved 8 April 2016

Remoto, D. (2002). Happy and gay . philSTAR.com . Retrieved 9 April 2016

Scott, W. (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society . Ateneo University Press.

Vega, P. (2011). The World of Amaya: Unleashing the Karakoa . GMA News Online . Retrieved 8 April 2016

Written by FilipiKnow

in Facts & Figures , History & Culture

Last Updated April 10, 2023 03:27 PM

FilipiKnow strives to ensure each article published on this website is as accurate and reliable as possible. We invite you, our reader, to take part in our mission to provide free, high-quality information for every Juan. If you think this article needs improvement, or if you have suggestions on how we can better achieve our goals, let us know by sending a message to admin at filipiknow dot net

Browse all articles written by FilipiKnow

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

Esiel Cabrera

Philippine Literature during Pre-Colonial Period

Precolonial Period

Filipinos often lose sight of the fact that the first period of the Philippine literary history is the longest. Certain events from the nation’s history had forced lowland Filipinos to begin counting the years of history from 1521, the first time written records by Westerners referred to the archipelago later to be called “Las Islas Filipinas”. However, the discovery of the “Tabon Man” in a cave in Palawan in 1962, has allowed us to stretch our prehistory as far as 50,000 years back. The stages of that prehistory show how the early Filipinos grew in control over their environment. Through the researches and writings about Philippine history, much can be reliably inferred about precolonial Philippine literature from an analysis of collected oral lore of Filipinos whose ancestors were able to preserve their indigenous culture by living beyond the reach of Spanish colonial administrators.

The oral literature of the precolonial Filipinos bore the marks of the community. The subject was invariably the common experience of the people constituting the village-food-gathering, creature and objects of nature, work in the home, field, forest or sea, caring for children, etc. This is evident in the most common forms of oral literature like the riddle, the proverbs and the song, which always seem to assume that the audience is familiar with the situations, activities and objects mentioned in the course of expressing a thought or emotion. The language of oral literature, unless the piece was part of the cultural heritage of the community like the epic, was the language of daily life. At this phase of literary development, any member of the community was a potential poet, singer or storyteller as long as he knew the language and had been attentive to the conventions f the forms.

Thousands of maxims, proverbs, epigrams, and the like have been listed by many different collectors and researchers from many dialects. Majority of these reclaimed from oblivion com from the Tagalos, Cebuano, and Ilocano dialects. And the bulk are rhyming couplets with verses of five, six seven, or eight syllables, each line of the couplet having the same number of syllables. The rhyming practice is still the same as today in the three dialects mentioned. A good number of the proverbs is conjectured as part of longer poems with stanza divisions, but only the lines expressive of a philosophy have remained remembered in the oral tradition. Classified with the maxims and proverbs are allegorical stanzas which abounded in all local literature. They contain homilies, didactic material, and expressions of homespun philosophy, making them often quoted by elders and headmen in talking to inferiors. They are rich in similes and metaphors. These one stanza poems were called Tanaga and consisted usually of four lines with seven syllables, all lines rhyming.

The most appreciated riddles of ancient Philippines are those that are rhymed and having equal number of syllables in each line, making them classifiable under the early poetry of this country. Riddles were existent in all languages and dialects of the ancestors of the Filipinos and cover practically all of the experiences of life in these times.

Almost all the important events in the life of the ancient peoples of this country were connected with some religious observance and the rites and ceremonies always some poetry recited, chanted, or sung. The lyrics of religious songs may of course be classified as poetry also, although the rhythm and the rhyme may not be the same.

Drama as a literary from had not yet begun to evolve among the early Filipinos. Philippine theater at this stage consisted largely in its simplest form, of mimetic dances imitating natural cycles and work activities. At its most sophisticated, theater consisted of religious rituals presided over by a priest or priestess and participated in by the community. The dances and ritual suggest that indigenous drama had begun to evolve from attempts to control the environment. Philippine drama would have taken the form of the dance-drama found in other Asian countries.

Prose narratives in prehistoric Philippines consisted largely or myths, hero tales, fables and legends. Their function was to explain natural phenomena, past events, and contemporary beliefs in order to make the environment less fearsome by making it more comprehensible and, in more instances, to make idle hours less tedious by filling them with humor and fantasy. There is a great wealth of mythical and legendary lore that belongs to this period, but preserved mostly by word of mouth, with few written down by interested parties who happen upon them.

The most significant pieces of oral literature that may safely be presumed to have originated in prehistoric times are folk epics. Epic poems of great proportions and lengths abounded in all regions of the islands, each tribe usually having at least one and some tribes possessing traditionally around five or six popular ones with minor epics of unknown number.

Filipinos had a culture that linked them with the Malays in the Southeast Asia, a culture with traces of Indian, Arabic, and, possibly Chinese influences. Their epics, songs, short poems, tales, dances and rituals gave them a native Asian perspective which served as a filtering device for the Western culture that the colonizers brought over from Europe.

Ten Reasons Why Life Was Better In PreColonial Philippines

Let’s look at some of the compelling reasons why we think life was really better during the pre-Spanish Philippines.

- Women Enjoyed Equal Status with Men.

During precolonial times, women shared equal footing with men in society. They were allowed to divorce, own and inherit property, and even lead their respective barangays or territories.

In matters of family, the women were for all intents and purposes the working heads, possessing the power of the purse and the sole right to name their children. They could dictate the terms of their marriage and even retain their maiden names if they chose to do so.

During this time, people also traced their heritage to both their father and mother. In fact, it could be said that precolonial Philippines was largely matriarchal, with the opinions of women holding great weight in matters of politics and religion (they also headed the rituals as the babaylans).

As a show of respect, men were even required to walk behind their wives. This largely progressive society that elevated women to such a high pedestal took a serious blow when the Spanish came. Eager to impose their patriarchal system, the Spanish relegated women to the homes, demonized the babaylans as satanic, and ingrained into our forefathers’ heads that women should be like Maria Clara—demure, self-effacing, and powerless.

- Society Was More Tolerant Back Then.

While it could be said that our modern society is one of the most tolerant in the world, we owe our open-mindedness not to the Americans and certainly not to the Spanish, but to the precolonial Filipinos.

Aside from allowing divorce, women back then also had a say in how many children they wanted. Sexuality was not as suppressed, and no premium was given to virginity before marriage. Although polygamy was practiced, men were expected to do so only if they could support and love each of his wives equally. Homosexuals were also largely tolerated, seeing as how some of the babaylans were actually men in drag.

Surprisingly, with the amount of sexual freedom, no prostitution existed during the pre-colonial days. In fact, some literature suggests that the American period—which heavily emphasized capitalism and profiteering—introduced prostitution into the country on a massive scale.

- The People Enjoyed A Higher Standard Of Government.

The relationship of the ruler to his subjects was very simple back then: In return for his protection, the people pay tribute and serve him both in times of war and peace.

Going by the evidence, we could say that our ancestors already practiced an early version of the Social Contract, a theory by prominent thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau which espoused the view that rulers owe their right to rule on the basis of the people’s consent.

Conversely, if the ruler became corrupt or incompetent, then the people had a right to remove him. And that’s exactly the kind of government our ancestors had. Although the datus technically came from the upper classes, he could be removed from his position by the lower classes if they found him wanting of his duties. Also, anyone (including women) could become the datu based on their merits such as bravery, wisdom, and leadership ability.

- We Were Self-Sufficient.

In terms of food, our forefathers did not suffer from any lack thereof. Blessed with such a resource-rich country, they had enough for themselves and their families.

Forests, rivers, and seas yielded plentiful supplies of meat, fish, and other foodstuffs. Later on, their diet became more varied especially when they learned to till the land using farming techniques that were quite advanced for their time. The Banaue Rice Terraces is one such proof of our ancestors’ ingenuity.

What’s more, they already had an advanced concept of agrarian equity. Men and women equally worked in the fields, and anyone could till public lands free of charge. Also, since they had little-to-no concept of exploitation for profit, our ancestors generally took care of the environment well.

Such was the abundance of foodstuffs that Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, the most-successful Spanish colonizer of the islands, was said to have reported the “abundance of rice, fowls, and wine, as well as great numbers of buffaloes, deer, wild boar and goats” when he first arrived in Luzon.

- We Had Smoother Foreign Relations.

We’ve all been taught that before the Spanish galleon trade, the precolonial Filipinos had already established trading and diplomatic relations with countries as far away as the Middle East.

In lieu of cash, our ancestors exchanged precious minerals, manufactured goods, etc. with Arabs, Indians, Chinese, and several other nationalities. During this time period, many foreigners permanently settled here after marveling at the beauty of the country and its people.

Out of the foreigners, it was the Chinese who were amazed at the precolonial Filipinos the most, especially when it came to their extraordinary honesty. Chinese traders often wrote about the Filipinos’ sincerity and said they were one of their most trusted clientele since they did not steal their goods and always paid their debts.

In fact, some Chinese—out of confidence—were known to simply leave their items on the beaches to be picked up by the Filipinos and traded inland. When they returned, the Filipinos would give them back their bartered items without anything missing.

- Our Forefathers Already Possessed A Working Judicial And Legislative System.

Although not as advanced (or as complicated) as our own today, the fact that our ancestors already possessed a working judicial and legislative system just goes to show that they were well-versed in the concept of justice.

Life in precolonial Philippines was governed by a set of statutes, both unwritten and written, and contained provisions with regards to civil and criminal laws. Usually, it was the Datu and the village elders who promulgated such laws, which were then announced and explained to the people by a town crier called the umalohokan.

The Datu and the elders also acted as de facto courts in case of disputes between individuals of their village. In case of inter-barangay disputes, a local board composed of elders from different barangays would usually act as an arbiter.

Penalties for anyone found guilty of a crime include censures, fines, imprisonment and death. Tortures and trials by ordeal during this time were also common. Like we’ve said, the system was not perfect, but it worked.

- They Had The Know-how To Make Advanced Weapons.

A lantaka (rentaka in Malay), a type of bronze cannon mounted on merchant vessels travelling the waterways of the Malay Archipelago. Its use was greatest in precolonial Southeast Asia, especially in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Via Wikipedia.

Our ancestors—far from being the archetypal spear-carrying, bahag-wearing tribesmen we picture them to be—were very proficient in the art of war. Aside from wielding swords and spears, they also knew how to make and fire guns and cannons. Rajah Sulayman, in particular, was said to have owned a huge 17-feet-long iron cannon.

Aside from the offensive weapons, our ancestors also knew how to construct huge fortresses and body armor. The Moros living in the south for instance, often wore armor that covered them head-to-toe. And yes, they also carried guns with them.

With all these weapons at their disposal and the fact that they were good hand-to-hand combatants, you’d think that the Spanish would have had a harder time colonizing the country. Sadly, the Spanish cleverly exploited the regionalist tendencies of the precolonial Filipinos. This divide-and-conquer strategy would be the major reason why the Spanish successfully controlled the country for more than 300 years.

- Several Professions Already Existed.

Aside from being farmers, hunters, weapon-makers, and seafarers, the precolonial Filipinos also dabbled—and excelled—in several other professions as well.

To name a few, many became involved in such professions as mining, textiles, and smiting. Owing to the excellent craftsmanship of the Filipinos, locally-produced items such as pots, jewelry, and clothing were highly-sought in other countries. In fact, it is reported that products of Filipino origin might have even reached as far away as ancient Egypt. Clearly, our ancestors were very skilled artisans.

- The Literacy Rate Was High.

Using the ancient system of writing called the baybayin, the precolonial Filipinos educated themselves very well, so much so that when the Spanish finally arrived, they were shocked to find out that the Filipinos possessed a literacy rate higher than that of Madrid!

However, the high literacy rate also proved to be a double-edged sword for the Filipinos once the Spanish arrived. Eager to evangelize and subjugate our ancestors, the missionaries exploited the baybayin for their own ends, learning and using it to translate their various works. Consequently, the precolonial Filipinos became more easily susceptible to foreign influence.

- We Already Had An Advanced Civilization.

Contrary to foreign accounts, our ancestors were not just some backwards, jungle-living savages. In reality, precolonial Philippines already possessed a very advanced civilization way before the coming of the Spanish.

Our ancestors possessed a complex working society and a culture replete with works of arts and literature. When the colonizers came, everything contradictory to their own system had to go. Sculptures, texts, religious ceremonies, and virtually anything else deemed obscene, evil or a threat to their rule were eliminated.

Conclusively, we can only speculate what would have happened had our ancestors never been colonized in the first place. Although the Spanish era (and the American period by extension) did have their good points, would it have really been worth it all in the end?

Reflection:

Precolonial Literature in the Philippines by one means or another gave us an illustration from the past. It underscores on how our literature began in the country which is the Philippines. From that point forward, we Filipinos do truly have beautiful and awesome literature that we can some way or another be pleased with. Philippines indeed, without a doubt a nation that is rich in custom and tradition through having diverse characteristics. It was evident that each of the tribes we have had their own specific manner of living which some way or another make them stand-out from others. As what have aforementioned, their folk speeches, folk songs, folk narratives, indigenous rituals and mimetic dances really affirmed our ties with our Southeast Asian neighbors. Even when their lifestyle before was not the same as we have now, they really have these techniques and ways on preserving their traditions for them to be able to pass it from generation to another generation. The differing qualities and abundance of Literature in the Philippines advanced next to each other with the nation’s history. This can best be acknowledged in the sense that the nation’s precolonial cultural traditions are very much abundant. Through these things, I can truly say that Philippines is a home of diverse and unique culture, norms and tradition.

I would like to thank the owner of this articles that I used. These were very helpful for my project.

You could visit the real website and my reference for this. 🙂

http://www.filipiknow.net/life-in-pre-colonial-philippines/

http://www.angelfire.com/la2/litera1/precolonial.html

Share this:

4 thoughts on “ philippine literature during pre-colonial period ”.

Hi, great work! May I know the artist of the artwork above? Thanks!

Thank you. However, I am not certain who really made the artwork above. But most probably, its a Filipino art piece.

This is a great and a scholastic work! I really find it helpful especially in providing reference and justification to the highly organized system of the pre-colonial Philippine society. Thanks for posting.

Thank you so much. Delighted that this helps. God bless.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1: Pre- and Early Colonial Literature

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 41809

- Wendy Kurant

- University of North Georgia via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students will be able to

- Categorize the types of Native American tales and their contribution to their respective tribes’ cultures.

- Identify significant tropes and motifs of movement in Native American creation stories.

- Identify the cultural characteristics of Native American creation, trickster, and first contact stories distinct from European cultural characteristics.

- Identify elements of trickster stories.

- Understand how the search for the Westward passage to Asia led to the European discovery of the Americas.

- Understand how the search for commodities led to territorial appropriation of North American land by various European countries.

- Understand the role religion played in European settlement in North America.

- Understand how their intended audience and purpose affected the content and tone of European exploration accounts.

- 1.1.1: Native American Accounts

- 1.1.2: European Exploration Accounts

- 1.2.1: Creation Story (Haudenosaunee (Iroquois))

- 1.2.2: How the World Was Made (Cherokee)

- 1.2.3: Talk Concerning the First Beginning (Zuni)

- 1.2.4: From the Winnebago Trickster Cycle

- 1.2.5: Origin of Disease and Medicine (Cherokee)

- 1.2.6: Thanksgiving Address (Haudenosaunee (Iroquois))

- 1.2.7: The Arrival of the Whites (Lenape (Delaware))

- 1.2.8: The Coming of the Whiteman Revealed - Dream of the White Robe and Floating Island (Micmac)

- 1.2.9: Reading and Review Questions

- 1.3.1: Letter of Discovery (1493)

- 1.3.2: Reading and Review Questions

- 1.4.1: From The Relation of Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca (1542)

- 1.4.2: Reading and Review Questions

- 1.5.1: From A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1588)

- 1.5.2: Reading and Review Questions

- 1.6.1: From The Voyages and Explorations of Sieur de Champlain (1613)

- 1.6.2: Reading and Review Questions

- 1.7.1: From The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (1624)

- 1.7.2: Reading and Review Questions

- 1.8.1: From A Description of New Netherland, the Country

- 1.8.2: Reading and Review Questions

Thumbnail: John Smith from an illustration in The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles ; with the names of the Adventurers, Planters, and Governours from their first beginning, Ano: 1584. (Public Domain; engraver uncertain via Wikipedia )

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 1

- Native American societies before contact

- Native American culture of the Southwest

- Native American culture of the West

- Native American culture of the Northeast

- Native American culture of the Southeast

- Native American culture of the Plains

Lesson summary: Native American societies before contact

- Native American societies before European contact

- Pre-colonization European society

- African societies and the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade

- European and African societies before contact

Native North America

Core historical theme, review question.

- How did environment and geography determine migration and hunting patterns for pre-Columbian societies?

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Teacher Elena

It's not just a job, it's an adventure.

Pre-Colonial Philippine Literature: Forms, Examples, and Frequently Asked Questions

The Philippines has a long history of storytelling, even before the Spanish arrived. These stories, passed down by word of mouth for many generations, were more than just entertainment. They were a way for our ancestors to teach people things, share important values, and connect with their culture. This blog will answer the question: “What are the dominant literary forms of pre-colonial Philippines?”

We’ll discuss each form of Philippine literature during pre-colonial period. We’ll also include pre-colonial literature examples and a brief explanation supporting each.

Forms of Philippine Literature During Pre-Colonial Period

Proverbs, known in Filipino as salawikain , are like practical advice passed down through generations. They often use rhymes to make them easier to remember and teach essential skills for navigating daily life.

Some examples include:

Riddles, or bugtong in Filpino, are mind teasers that challenge wit and creativity. Often poetic and playful, they use descriptions or metaphors to lead the listener to the answer.

During the pre-colonial period in the Philippines, riddles were a common form of oral literature. They are like proverbs but differ in one thing—they demand an answer.

Filipino riddles often have a humorous tone, but their answers are often more serious than expected.

Here are examples of Philippine riddles:

Filipinos expressed their emotions and experiences through songs. These beautiful songs capture the joys and sorrows of our ancestors’ lives, from finding love to saying goodbye, and everything in between.

Here are five examples of Philippine folk songs during the pre-colonial period:

- Ili-ili (Ilongo): A lullaby that is an example of folk song in the Philippines during the pre-colonial period.

- Panawagon and Balitao (Ilongo): These are examples of love songs that were sung during the pre-colonial period.

- Bayok (Maranao): This is a type of folk song that originated from the Maranao people, a Muslim ethnic group in the Philippines, and is still sung today.

- Ambahan (Mangyan): This is a seven-syllable per-line (heptasyllabic) poem about human relationships, social entertainment, and a tool for teaching the young. It is an example of the traditional music of the Mangyans, an indigenous group in the Philippines.

These were narratives passed down, often explaining natural phenomena or cultural practices. These narratives also tell stories of origin. Often, they’re called myths and legends.

Here’s how they differ:

These are the crown jewels of pre-colonial literature. These lengthy narrative poems recount the adventures and misadventures of heroes and supernatural beings.

Here are a few examples:

Frequently Asked Questions about the Pre-colonial Philippine Literature

What is the pre-colonial era in the philippines.

The Philippines’ pre-colonial era is like the Philippines before history books were written down. It’s a long time ago, way before the Spanish came in the 16th century. Imagine a Philippines made up of many independent communities with their own languages, customs, and traditions.

What is Philippine literature during the pre-colonial period?

Since there weren’t any printing presses yet, literature back then wasn’t like the books we read today. Instead, stories were passed down from generation to generation by word of mouth. Our ancestors would tell folktales, sing songs, recite poems, and chant proverbs to keep their traditions alive.

What is the difference between pre-colonial and colonial literature?

The main difference is when they were created . Colonial literature refers to stories written during the Spanish era, often influenced by European themes and religion. Literature written beyond this period, including American and Japanese, is also considered colonial literature. Pre-colonial literature, on the other hand, reflects the beliefs, way of life, and heroes of Filipinos before the arrival of the colonizers.

Why is pre-colonial literature important in the Philippines?

Pre-colonial literature is super important because it tells us much about how people lived back then. It shows their values, beliefs, and even how they saw the world around them. It’s like a window to the past!

What are the characteristics of pre-colonial literature in the Philippines?

Since it was passed down orally, pre-colonial stories often use repetition, rhyming, and vivid language to make them easier to remember and sing. They also focus on themes like bravery, community, and respect for nature.

How can these pre-colonial forms of literature be of use to your life right now?

Precolonial literature is like a treasure chest for understanding our past. These stories, myths, and poems are like windows into how people lived, what they believed in, and what was important to them way before colonization. This can help us appreciate our roots and where our traditions might come from. Plus, the lessons and morals in these stories are timeless. It’s like getting advice from old, wise people.

Do you think you can still use the lessons they teach in your daily life?

Yes! Even though things are different now, the lessons in precolonial literature can still totally apply today. They teach us about bravery, honesty, respect, and dealing with tough choices. These values are important no matter what time period you’re in. So, next time you read a pre-colonial story, think about the lesson it might be trying to tell. It might surprise you how relevant it can be!

If you’re looking for more resources about literature , then make sure to browse my website .

Share this:

Related posts.

21st Century Literary Genres: A Guide to Evolving Forms of Storytelling

March 29, 2024 May 5, 2024

Opening Remarks for Parents Meeting Sample

March 3, 2024 March 29, 2024

Guest Speaker Invitation Letter Sample

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Politics and Society in Pre-colonial Africa: Implications for Governance in Contemporary Times

- First Online: 06 October 2017

Cite this chapter

- Alinah K. Segobye 3

3347 Accesses

The African continent is acknowledged as a leader in the history of human development and the origins of contemporary institutions. The evidence of human origins from southern and eastern Africa has highlighted the importance of Africa to the development of humanity. In areas such as cognitive development, the origins of social behavior (including the institution of the family, rituals and advances in tool technologies ranging from stone to metals), Africa is richly endowed with material evidence. This chapter focuses on the nature of pre-colonial political institutions and how they informed the development of African societies and civilizations. The chapter draws examples from the tapestry of African societies across time and space and highlights how these developments influenced local, regional and global systems including trade, urbanism and technology.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bisson, Michael. 2000. Precolonial Copper Metallurgy: Sociopolitical Context. In Ancient African Metallurgy: The Sociocultural Context , ed. Michael S. Bisson, Terry S. Childs, De Philip Barros, Augustin F.C. Holl, and Joseph O. Vogel, vol. 2, 83–145. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Google Scholar

Bisson, Michael S., Terry S. Childs, De Philip Barros, Augustin F.C. Holl, and Joseph O. Vogel. 2000. Ancient African Metallurgy: The Sociocultural Context . Vol. 2, 83–145. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Bonner, P. 2007. The Myth of the Vacant Land. In A Search for Origins: Silence, History and South Africa’s ‘Cradle of Humankind’ , ed. P. Bonner, A. Esterhuysen, and T. Jenkins. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Chirikure, Shadreck. 2007. Metals in Society: Iron Production and its Position in Iron Age Communities of Southern Africa. Journal of Social Archaeology 7 (1): 72–100.

Article Google Scholar

De Barros, P. 2000. Iron Metallurgy. In Ancient African Metallurgy: The Sociocultural Context , ed. M. Bisson et al., 149–173. Walnut Creek: Alta Mira.

Holl, Augustin. 2000. Metals and Precolonial African Society. In Ancient African Metallurgy: The Sociocultural Context , ed. Michael S. Bisson, Terry S. Childs, Philip Barros De, Augustin F.C. Holl, and Joseph O. Vogel, vol. 2, 1–91. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

Huffman, Thomas N. 1996. Snakes & Crocodiles: Power and Symbolism in Ancient Zimbabwe . Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Huffman, Thomas. 2007. The Early Iron Age at Broederstroom and around the ‘Cradle of Humankind’. In A Search for Origins: Silence, History and South Africa’s ‘Cradle of Humankind’ , ed. Philip Lewis Bonner and Amanda Esterhuysen, 148–161. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Iliffe, J. 2007. Africans: The History of a Continent . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Insoll, Timothy. 2003. The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa . Cambridge: Cambridge University press.

Marks, Shula. 1980. South-Africa-Myth of the Empty Land. History Today 30: 7–12.

Meskell, Lynn. 1999. Archaeologies of Social Life: Age, Sex, Class et Cetera in Ancient Egypt . Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Ndoro, Webber. 2001. Your Monument Our Shrine: The Preservation of Great Zimbabwe . Vol. 19. Uppsala: Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University.

New African 2015. Buying Democracy: The Fate of Elections in Africa. No 549.

New African 2015. Mercury Rising: Africa’s Land Issue Heats Up. No 550.

New African 2015. To go or not to go: The Drama over African Presidential Terms. No. 551.

New African. Debating the post-2015 Development Goals: Africa’s Future in Whose Hands? No. 553.

Phillipson, David W. 2005. African Archaeology . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pikirayi, I. 2000. The Zimbabwe Culture: Origins and Decline of Southern Zimbabwe States . Walnut Creek: Alta Mira.

Reid, Richard J. 2011. A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present . Vol. 7. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

Reid, R.J. 2012. A History of Modern Africa: 1800 to the Present . 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Reid, Andrew, and Alinah Segobye. 2000a. Politics, Society and Trade on the Eastern Margins of the Kalahari. Goodwin Series 8: 58–68.

Reid, Andrew, and Alinah K. Segobye. 2000b. An Ivory Cache from Botswana. Antiquity 74 (284): 326–331.

Sall, Alioune, and Alinah K. Segobye. 2013. How Do We Realise the Elusive Vision of an Africa-led Development Agenda? Pretoria: HSRC Press.

Schoeman, Maria H. 2006. Imagining Rain-Places: Rain-Control and Changing Ritual Landscapes in the Shashe-Limpopo Confluence Area, South Africa. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 61: 152–165.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

Alinah K. Segobye

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Thabo Mbeki African Leadership Institute, University of South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa

Samuel Ojo Oloruntoba

Department of History, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA

Toyin Falola

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Segobye, A.K. (2018). Politics and Society in Pre-colonial Africa: Implications for Governance in Contemporary Times. In: Oloruntoba, S., Falola, T. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of African Politics, Governance and Development. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95232-8_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95232-8_9

Published : 06 October 2017

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-95231-1

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-95232-8

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care