- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Rheumatoid arthritis

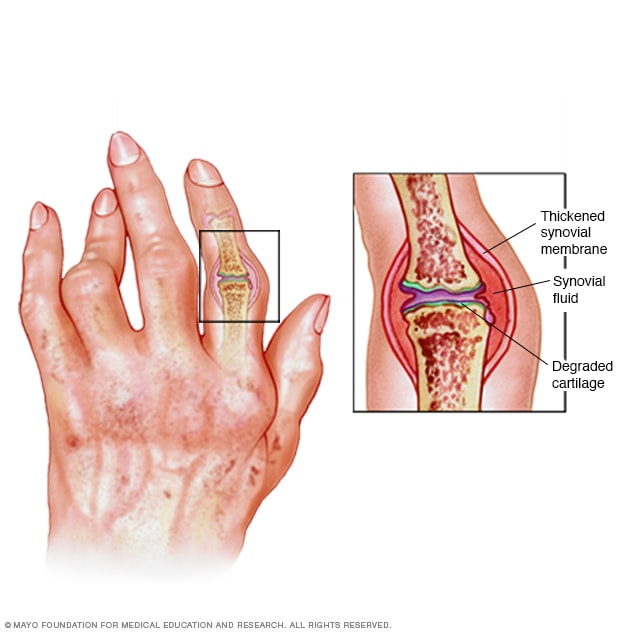

Rheumatoid arthritis can cause pain, swelling and deformity. As the tissue that lines your joints (synovial membrane) becomes inflamed and thickened, fluid builds up and joints erode and degrade.

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic inflammatory disorder that can affect more than just your joints. In some people, the condition can damage a wide variety of body systems, including the skin, eyes, lungs, heart and blood vessels.

An autoimmune disorder, rheumatoid arthritis occurs when your immune system mistakenly attacks your own body's tissues.

Unlike the wear-and-tear damage of osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis affects the lining of your joints, causing a painful swelling that can eventually result in bone erosion and joint deformity.

The inflammation associated with rheumatoid arthritis is what can damage other parts of the body as well. While new types of medications have improved treatment options dramatically, severe rheumatoid arthritis can still cause physical disabilities.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to Arthritis

- Assortment of Products for Independent Living from Mayo Clinic Store

- Products for Mobility and Safety

Signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis may include:

- Tender, warm, swollen joints

- Joint stiffness that is usually worse in the mornings and after inactivity

- Fatigue, fever and loss of appetite

Early rheumatoid arthritis tends to affect your smaller joints first — particularly the joints that attach your fingers to your hands and your toes to your feet.

As the disease progresses, symptoms often spread to the wrists, knees, ankles, elbows, hips and shoulders. In most cases, symptoms occur in the same joints on both sides of your body.

About 40% of people who have rheumatoid arthritis also experience signs and symptoms that don't involve the joints. Areas that may be affected include:

- Salivary glands

- Nerve tissue

- Bone marrow

- Blood vessels

Rheumatoid arthritis signs and symptoms may vary in severity and may even come and go. Periods of increased disease activity, called flares, alternate with periods of relative remission — when the swelling and pain fade or disappear. Over time, rheumatoid arthritis can cause joints to deform and shift out of place.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have persistent discomfort and swelling in your joints.

Vivien Williams: Pain, swelling and stiffness in your joints — all are symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. But because these symptoms come and go, the condition can sometimes be tricky to diagnose. And it's important to get the right diagnosis because starting treatment early can make a difference.

Virginia Wimmer, has rheumatoid arthritis: Give me your best shot!

Ms. Williams: At first, Virginia Wimmer blamed her painful joints on too much volleyball.

Ms. Wimmer: In my knees and in my wrists.

Ms. Williams: For a couple years, she put up with the pain and swelling that would come and go. Then things got much worse.

Ms. Wimmer: I couldn't have a ball touch my arms.

Ms. Williams: She couldn't do much of anything, let alone play outside with her daughter.

Ms. Wimmer: That was really hard. She'd have to beg me to play with her, and teach her, and help her. And I just had to sit and watch.

Ms. Williams: Virginia was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis.

Nisha Manek, M.D., Rheumatology, Mayo Clinic: Rheumatoid arthritis is an inflammatory condition. It's also associated with the immune system.

Ms. Williams: Dr. Nisha Manek says it happens when the immune system becomes deregulated. You see, the joint capsule has a lining of tissue called the synovium. The synovium makes fluid that keeps joints lubricated. When you have rheumatoid arthritis, your immune system sends antibodies to the synovium and causes inflammation. This causes pain and joint damage, especially in small joints in the fingers and wrists. But it can affect any joint.

The good news is that treatment for rheumatoid arthritis has improved dramatically over the last years. Medications, such as methotrexate, help bring the immune system back into balance and steroids can help calm flare-ups. So what was once an often crippling disease can now be controlled for many people — people like Virginia whose disease is pretty severe.

Ms. Wimmer: You can get to the point where you are doing the things that you love and that is the goal.

Ms. Williams: Dr. Manek says if you have pain, swelling and stiffness in your joints that comes and goes and is on both sides of your body, see your doctor to see if it is rheumatoid arthritis.

Rheumatoid is different than osteoarthritis which damages joints because of wear and tear.

For Medical Edge, I'm Vivien Williams.

More Information

- Rheumatoid arthritis: Does pregnancy affect symptoms?

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease. Normally, your immune system helps protect your body from infection and disease. In rheumatoid arthritis, your immune system attacks healthy tissue in your joints. It can also cause medical problems with your heart, lungs, nerves, eyes and skin.

Doctors don't know what starts this process, although a genetic component appears likely. While your genes don't actually cause rheumatoid arthritis, they can make you more likely to react to environmental factors — such as infection with certain viruses and bacteria — that may trigger the disease.

Risk factors

Factors that may increase your risk of rheumatoid arthritis include:

- Your sex. Women are more likely than men to develop rheumatoid arthritis.

- Age. Rheumatoid arthritis can occur at any age, but it most commonly begins in middle age.

- Family history. If a member of your family has rheumatoid arthritis, you may have an increased risk of the disease.

- Smoking. Cigarette smoking increases your risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis, particularly if you have a genetic predisposition for developing the disease. Smoking also appears to be associated with greater disease severity.

- Excess weight. People who are overweight appear to be at a somewhat higher risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis.

Complications

Rheumatoid arthritis increases your risk of developing:

- Osteoporosis. Rheumatoid arthritis itself, along with some medications used for treating rheumatoid arthritis, can increase your risk of osteoporosis — a condition that weakens your bones and makes them more prone to fracture.

- Rheumatoid nodules. These firm bumps of tissue most commonly form around pressure points, such as the elbows. However, these nodules can form anywhere in the body, including the heart and lungs.

- Dry eyes and mouth. People who have rheumatoid arthritis are much more likely to develop Sjogren's syndrome, a disorder that decreases the amount of moisture in the eyes and mouth.

- Infections. Rheumatoid arthritis itself and many of the medications used to combat it can impair the immune system, leading to increased infections. Protect yourself with vaccinations to prevent diseases such as influenza, pneumonia, shingles and COVID-19.

- Abnormal body composition. The proportion of fat to lean mass is often higher in people who have rheumatoid arthritis, even in those who have a normal body mass index (BMI).

- Carpal tunnel syndrome. If rheumatoid arthritis affects your wrists, the inflammation can compress the nerve that serves most of your hand and fingers.

- Heart problems. Rheumatoid arthritis can increase your risk of hardened and blocked arteries, as well as inflammation of the sac that encloses your heart.

- Lung disease. People with rheumatoid arthritis have an increased risk of inflammation and scarring of the lung tissues, which can lead to progressive shortness of breath.

- Lymphoma. Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of lymphoma, a group of blood cancers that develop in the lymph system.

- Is depression a factor in rheumatoid arthritis?

- Rheumatoid arthritis: Can it affect the eyes?

- Rheumatoid arthritis: Can it affect the lungs?

- Rheumatoid arthritis. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. https://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Rheumatic_Disease/default.asp. Accessed Feb. 9, 2021.

- Rheumatoid arthritis. American College of Rheumatology. https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Rheumatoid-Arthritis. Accessed Feb. 9, 2021.

- Matteson EL, et al. Overview of the systemic and nonarticular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Feb. 9, 2021.

- Goldman L, et al., eds. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Feb. 9, 2021.

- Ferri FF. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2021. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Feb. 9, 2021.

- Kellerman RD, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Conn's Current Therapy 2021. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Feb. 9, 2021.

- Moreland LW, et al. General principles and overview of management of rheumatoid arthritis in adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Feb. 9, 2021.

- Xeljanz, Xeljanz XR (tofacitinib): Drug safety communication — Initial safety trial results find increased risk of serious heart-related problems and cancer with arthritis and ulcerative colitis medicine. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/xeljanz-xeljanz-xr-tofacitinib-drug-safety-communication-initial-safety-trial-results-find-increased. Accessed Feb. 23, 2021.

- Office of Patient Education. Arthritis: Caring for your joints. Mayo Clinic. 2017.

- Living with arthritis. American Occupational Therapy Association. https://www.aota.org/About-Occupational-Therapy/Patients-Clients/Adults/Arthritis.aspx. Accessed Feb. 23, 2021.

- Renaldi RZ. Total joint replacement for severe rheumatoid arthritis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Feb. 9, 2021.

- Rheumatoid arthritis: In depth. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/rheumatoid-arthritis-in-depth. Accessed Feb. 23, 2021.

- Chang-Miller A (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Feb. 27, 2021.

- 6 tips to manage rheumatoid arthritis symptoms

- Does stress make rheumatoid arthritis worse?

- Ease rheumatoid arthritis pain when grocery shopping

- How do I reduce fatigue from rheumatoid arthritis?

- Protect your joints while housecleaning

- Rethinking Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis and exercise

- Tips to make your mornings easier

Associated Procedures

- C-reactive protein test

- Elbow replacement surgery

- Hip replacement

- Knee replacement

- Rheumatoid factor

- Sed rate (erythrocyte sedimentation rate)

- Shoulder replacement surgery

- Spinal fusion

News from Mayo Clinic

- Mayo Clinic researchers identify link between gut bacteria and pre-clinical autoimmunity and aging in rheumatoid arthritis Oct. 07, 2023, 11:00 a.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

AMY M. WASSERMAN, MD

Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(11):1245-1252

Patient information : A handout on this topic is available at https://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases-conditions/rheumatoid-arthritis.html .

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations to disclose.

Rheumatoid arthritis is the most commonly diagnosed systemic inflammatory arthritis. Women, smokers, and those with a family history of the disease are most often affected. Criteria for diagnosis include having at least one joint with definite swelling that is not explained by another disease. The likelihood of a rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis increases with the number of small joints involved. In a patient with inflammatory arthritis, the presence of a rheumatoid factor or anti-citrullinated protein antibody, or elevated C-reactive protein level or erythrocyte sedimentation rate suggests a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Initial laboratory evaluation should also include complete blood count with differential and assessment of renal and hepatic function. Patients taking biologic agents should be tested for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and tuberculosis. Earlier diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis allows for earlier treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic agents. Combinations of medications are often used to control the disease. Methotrexate is typically the first-line drug for rheumatoid arthritis. Biologic agents, such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, are generally considered second-line agents or can be added for dual therapy. The goals of treatment include minimization of joint pain and swelling, prevention of radiographic damage and visible deformity, and continuation of work and personal activities. Joint replacement is indicated for patients with severe joint damage whose symptoms are poorly controlled by medical management.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common inflammatory arthritis, with a lifetime prevalence of up to 1 percent worldwide. 1 Onset can occur at any age, but peaks between 30 and 50 years. 2 Disability is common and significant. In a large U.S. cohort, 35 percent of patients with RA had work disability after 10 years. 3

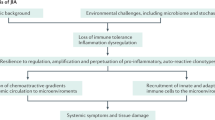

Etiology and Pathophysiology

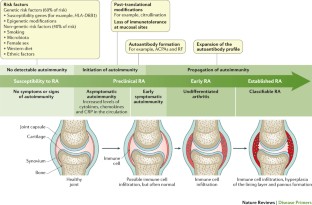

Like many autoimmune diseases, the etiology of RA is multifactorial. Genetic susceptibility is evident in familial clustering and monozygotic twin studies, with 50 percent of RA risk attributable to genetic factors. 4 Genetic associations for RA include human leukocyte antigen-DR4 5 and -DRB1, and a variety of alleles called the shared epitope. 6 , 7 Genome-wide association studies have identified additional genetic signatures that increase the risk of RA and other autoimmune diseases, including STAT4 gene and CD40 locus. 5 Smoking is the major environmental trigger for RA, especially in those with a genetic predisposition. 8 Although infections may unmask an autoimmune response, no particular pathogen has been proven to cause RA. 9

RA is characterized by inflammatory pathways that lead to proliferation of synovial cells in joints. Subsequent pannus formation may lead to underlying cartilage destruction and bony erosions. Overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-6, drives the destructive process. 10

RISK FACTORS

Older age, a family history of the disease, and female sex are associated with increased risk of RA, although the sex differential is less prominent in older patients. 1 Both current and prior cigarette smoking increases the risk of RA (relative risk [RR] = 1.4, up to 2.2 for more than 40-pack-year smokers). 11

Pregnancy often causes RA remission, likely because of immunologic tolerance. 12 Parity may have long-lasting impact; RA is less likely to be diagnosed in parous women than in nulliparous women (RR = 0.61). 13 , 14 Breastfeeding decreases the risk of RA (RR = 0.5 in women who breastfeed for at least 24 months), whereas early menarche (RR = 1.3 for those with menarche at 10 years of age or younger) and very irregular menstrual periods (RR = 1.5) increase risk. 14 Use of oral contraceptive pills or vitamin E does not affect RA risk. 15

TYPICAL PRESENTATION

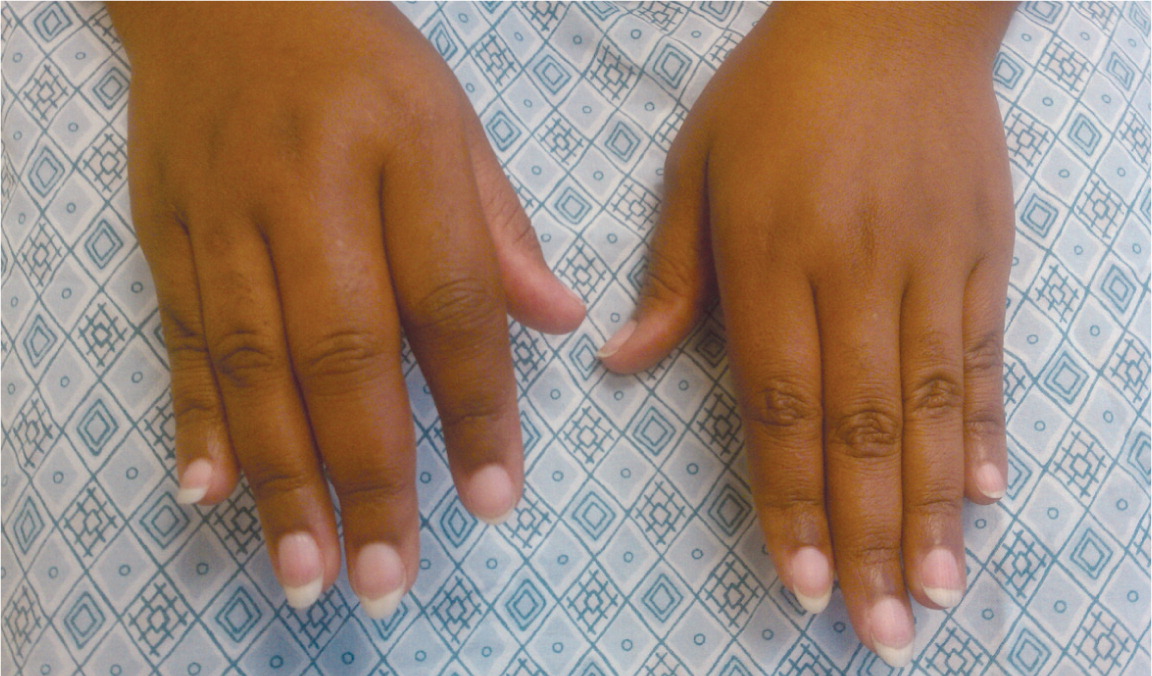

Patients with RA typically present with pain and stiffness in multiple joints. The wrists, proximal interphalangeal joints, and metacarpophalangeal joints are most commonly involved. Morning stiffness lasting more than one hour suggests an inflammatory etiology. Boggy swelling due to synovitis may be visible ( Figure 1 ) , or subtle synovial thickening may be palpable on joint examination. Patients may also present with more indolent arthralgias before the onset of clinically apparent joint swelling. Systemic symptoms of fatigue, weight loss, and low-grade fever may occur with active disease.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism collaborated to create new classification criteria for RA ( Table 1 ) . 16 The new criteria are an effort to diagnose RA earlier in patients who may not meet the 1987 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria. The 2010 criteria do not include presence of rheumatoid nodules or radiographic erosive changes, both of which are less likely in early RA. Symmetric arthritis is also not required in the 2010 criteria, allowing for early asymmetric presentation.

In addition, Dutch researchers have developed and validated a clinical prediction rule for RA ( Table 2 ) . 17 , 18 The purpose of this rule is to help identify patients with undifferentiated arthritis that is most likely to progress to RA, and to guide follow-up and referral.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Autoimmune diseases such as RA are often characterized by the presence of autoantibodies. Rheumatoid factor is not specific for RA and may be present in patients with other diseases, such as hepatitis C, and in healthy older persons. Anti-citrullinated protein antibody is more specific for RA and may play a role in disease pathogenesis. 6 Approximately 50 to 80 percent of persons with RA have rheumatoid factor, anti-citrullinated protein antibody, or both. 10 Patients with RA may have a positive antinuclear antibody test result, and the test is of prognostic importance in juvenile forms of this disease. 19 C-reactive protein levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are often increased with active RA, and these acute phase reactants are part of the new RA classification criteria. 16 C-reactive protein levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate may also be used to follow disease activity and response to medication.

Baseline complete blood count with differential and assessment of renal and hepatic function are helpful because the results may influence treatment options (e.g., a patient with renal insufficiency or significant thrombocytopenia likely would not be prescribed a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug [NSAID]). Mild anemia of chronic disease occurs in 33 to 60 percent of all patients with RA, 20 although gastrointestinal blood loss should also be considered in patients taking corticosteroids or NSAIDs. Methotrexate is contraindicated in patients with hepatic disease, such as hepatitis C, and in patients with significant renal impairment. 21 Biologic therapy, such as a TNF inhibitor, requires a negative tuberculin test or treatment for latent tuberculosis. Hepatitis B reactivation can also occur with TNF inhibitor use. 22 Radiography of hands and feet should be performed to evaluate for characteristic periarticular erosive changes, which may be indicative of a more aggressive RA subtype. 10

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Skin findings suggest systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, or psoriatic arthritis. Polymyalgia rheumatica should be considered in an older patient with symptoms primarily in the shoulder and hip, and the patient should be asked questions related to associated temporal arteritis. Chest radiography is helpful to evaluate for sarcoidosis as an etiology of arthritis.

Patients with inflammatory back symptoms, a history of inflammatory bowel disease, or inflammatory eye disease may have spondyloarthropathy. Persons with less than six weeks of symptoms may have a viral process, such as parvovirus. Recurrent self-limited episodes of acute joint swelling suggest crystal arthropathy, and arthrocentesis should be performed to evaluate for monosodium urate monohydrate or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals. The presence of numerous myofascial trigger points and somatic symptoms may suggest fibromyalgia, which can coexist with RA. To help guide diagnosis and determine treatment strategy, patients with inflammatory arthritis should be promptly referred to a rheumatology subspecialist. 16 , 17

After RA has been diagnosed and an initial evaluation performed, treatment should begin. Recent guidelines have addressed the management of RA, 21 , 22 but patient preference also plays an important role. There are special considerations for women of childbearing age because many medications have deleterious effects on pregnancy. Goals of therapy include minimizing joint pain and swelling, preventing deformity (such as ulnar deviation) and radiographic damage (such as erosions), maintaining quality of life (personal and work), and controlling extra-articular manifestations. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are the mainstay of RA therapy.

DMARDs can be biologic or nonbiologic ( Table 3 ) . 23 Biologic agents include monoclonal antibodies and recombinant receptors to block cytokines that promote the inflammatory cascade responsible for RA symptoms. Methotrexate is recommended as the first-line treatment in patients with active RA, unless contraindicated or not tolerated. 21 Leflunomide (Arava) may be used as an alternative to methotrexate, although gastrointestinal adverse effects are more common. Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) or hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) is recommended as monotherapy in patients with low disease activity or without poor prognostic features (e.g., seronegative, nonerosive RA). 21 , 22

Combination therapy with two or more DMARDs is more effective than monotherapy; however, adverse effects may also be greater. 24 If RA is not well controlled with a nonbiologic DMARD, a biologic DMARD should be initiated. 21 , 22 TNF inhibitors are the first-line biologic therapy and are the most studied of these agents. If TNF inhibitors are ineffective, additional biologic therapies can be considered. Simultaneous use of more than one biologic therapy (e.g., adalimumab [Humira] with abatacept [Orencia]) is not recommended because of an unacceptable rate of adverse effects. 21

NSAIDS AND CORTICOSTEROIDS

Drug therapy for RA may involve NSAIDs and oral, intramuscular, or intra-articular corticosteroids for controlling pain and inflammation. Ideally, NSAIDs and corticosteroids are used only for short-term management. DMARDs are the preferred therapy. 21 , 22

COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES

Dietary interventions, including vegetarian and Mediterranean diets, have been studied in the treatment of RA without convincing evidence of benefit. 25 , 26 Despite some favorable outcomes, there is a lack of evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture in placebo-controlled trials of patients with RA. 27 , 28 In addition, thermotherapy and therapeutic ultrasound for RA have not been studied adequately. 29 , 30 A Cochrane review of herbal treatments for RA concluded that gamma-linolenic acid (from evening primrose or black currant seed oil) and Tripterygium wilfordii (thunder god vine) have potential benefits. 31 It is important to inform patients that serious adverse effects have been reported with use of herbal therapy. 31

EXERCISE AND PHYSICAL THERAPY

Results of randomized controlled trials support physical exercise to improve quality of life and muscle strength in patients with RA. 32 , 33 Exercise training programs have not been shown to have deleterious effects on RA disease activity, pain scores, or radiographic joint damage. 34 Tai chi has been shown to improve ankle range of motion in persons with RA, although randomized trials are limited. 35 Randomized controlled trials of Iyengar yoga in young adults with RA are underway. 36

DURATION OF TREATMENT

Remission is obtainable in 10 to 50 percent of patients with RA, depending on how remission is defined and the intensity of therapy. 10 Remission is more likely in males, nonsmokers, persons younger than 40 years, and in those with late-onset disease (patients older than 65 years), with shorter duration of disease, with milder disease activity, without elevated acute phase reactants, and without positive rheumatoid factor or anti- citrullinated protein antibody findings. 37

After the disease is controlled, medication dosages may be cautiously decreased to the minimum amount necessary. Patients will require frequent monitoring to ensure stable symptoms, and prompt increase in medication is recommended with disease flare-ups. 22

JOINT REPLACEMENT

Joint replacement is indicated when there is severe joint damage and unsatisfactory control of symptoms with medical management. Long-term outcomes are good, with only 4 to 13 percent of large joint replacements requiring revision within 10 years. 38 The hip and knee are the most commonly replaced joints.

Long-term Monitoring

Although RA is considered a disease of the joints, it is also a systemic disease capable of involving multiple organ systems. Extra-articular manifestations of RA are included in Table 4 . 1 , 2 , 10

Patients with RA have a twofold increased risk of lymphoma, which is thought to be caused by the underlying inflammatory process, and not a consequence of medical treatment. 39 Patients with RA are also at an increased risk of coronary artery disease, and physicians should work with patients to modify risk factors, such as smoking, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol. 40 , 41 Class III or IV congestive heart failure (CHF) is a contraindication for using TNF inhibitors, which can worsen CHF outcomes. 21 In patients with RA and malignancy, caution is needed with continued use of DMARDs, especially TNF inhibitors. Biologic DMARDs, methotrexate, and leflunomide should not be initiated in patients with active herpes zoster, significant fungal infection, or bacterial infection requiring antibiotics. 21 Complications of RA and its treatments are listed in Table 5 . 1 , 2 , 10

Patients with RA live three to 12 years less than the general population. 40 Increased mortality in these patients is mainly due to accelerated cardiovascular disease, especially in those with high disease activity and chronic inflammation. The relatively new biologic therapies may reverse progression of atherosclerosis and extend life in those with RA. 41

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms rheumatoid arthritis, extra-articular manifestations, and disease-modifying antirheumatic agents. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, Clinical Evidence, the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence, and UpToDate. Search date: September 20, 2010.

Etiology and pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. In: Firestein GS, Kelley WN, eds. Kelley's Textbook of Rheumatology . 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009: 1035–1086.

Bathon J, Tehlirian C. Rheumatoid arthritis clinical and laboratory manifestations. In: Klippel JH, Stone JH, Crofford LJ, et al., eds. Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases . 13th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2008: 114–121.

Allaire S, Wolfe F, Niu J, et al. Current risk factors for work disability associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(3):321-328.

MacGregor AJ, Snieder H, Rigby AS, et al. Characterizing the quantitative genetic contribution to rheumatoid arthritis using data from twins. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(1):30-37.

Orozco G, Barton A. Update on the genetic risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6(1):61-75.

Balsa A, Cabezón A, Orozco G, et al. Influence of HLA DRB1 alleles in the susceptibility of rheumatoid arthritis and the regulation of antibodies against citrullinated proteins and rheumatoid factor. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(2):R62.

McClure A, Lunt M, Eyre S, et al. Investigating the viability of genetic screening/testing for RA susceptibility using combinations of five confirmed risk loci. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(11):1369-1374.

Bang SY, Lee KH, Cho SK, et al. Smoking increases rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility in individuals carrying the HLA-DRB1 shared epitope, regardless of rheumatoid factor or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody status. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(2):369-377.

Wilder RL, Crofford LJ. Do infectious agents cause rheumatoid arthritis?. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991(265):36-41.

Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2010;376(9746):1094-1108.

Costenbader KH, Feskanich D, Mandl LA, et al. Smoking intensity, duration, and cessation, and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis in women. Am J Med. 2006;119(6):503.e1-e9.

Kaaja RJ, Greer IA. Manifestations of chronic disease during pregnancy. JAMA. 2005;294(21):2751-2757.

Guthrie KA, Dugowson CE, Voigt LF, et al. Does pregnancy provide vaccine-like protection against rheumatoid arthritis?. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(7):1842-1848.

Karlson EW, Mandl LA, Hankinson SE, et al. Do breast-feeding and other reproductive factors influence future risk of rheumatoid arthritis? Results from the Nurses' Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3458-3467.

Karlson EW, Shadick NA, Cook NR, et al. Vitamin E in the primary prevention of rheumatoid arthritis: the Women's Health Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(11):1589-1595.

Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative [published correction appears in Ann Rheum Dis . 2010;69(10):1892]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(9):1580-1588.

van der Helm-van Mil AH, le Cessie S, van Dongen H, et al. A prediction rule for disease outcome in patients with recent-onset undifferentiated arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(2):433-440.

Mochan E, Ebell MH. Predicting rheumatoid arthritis risk in adults with undifferentiated arthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(10):1451-1453.

Ravelli A, Felici E, Magni-Manzoni S, et al. Patients with antinuclear antibody-positive juvenile idiopathic arthritis constitute a homogeneous subgroup irrespective of the course of joint disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):826-832.

Wilson A, Yu HT, Goodnough LT, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med. 2004;116(suppl 7A):50S-57S.

Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762-784.

Deighton C, O'Mahony R, Tosh J, et al.; Guideline Development Group. Management of rheumatoid arthritis: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2009;338:b702.

AHRQ. Choosing medications for rheumatoid arthritis. April 9, 2008. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/14/85/RheumArthritisClinicianGuide.pdf . Accessed June 23, 2011.

Choy EH, Smith C, Doré CJ, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy and toxicity of combining disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis based on patient withdrawal. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44(11):1414-1421.

Smedslund G, Byfuglien MG, Olsen SU, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dietary interventions for rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(5):727-735.

Hagen KB, Byfuglien MG, Falzon L, et al. Dietary interventions for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;21(1):CD006400.

Wang C, de Pablo P, Chen X, et al. Acupuncture for pain relief in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1249-1256.

Kelly RB. Acupuncture for pain. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(5):481-484.

Robinson V, Brosseau L, Casimiro L, et al. Thermotherapy for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;2(2):CD002826.

Casimiro L, Brosseau L, Robinson V, et al. Therapeutic ultrasound for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3(3):CD003787.

Cameron M, Gagnier JJ, Chrubasik S. Herbal therapy for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:CD002948.

Brodin N, Eurenius E, Jensen I, et al. Coaching patients with early rheumatoid arthritis to healthy physical activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(3):325-331.

Baillet A, Payraud E, Niderprim VA, et al. A dynamic exercise programme to improve patients' disability in rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(4):410-415.

Hurkmans E, van der Giesen FJ, Vliet Vlieland TP, et al. Dynamic Exercise programs (aerobic capacity and/or muscle strength training) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(4):CD006853.

Han A, Robinson V, Judd M, et al. Tai chi for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;3:CD004849.

Evans S, Cousins L, Tsao JC, et al. A randomized controlled trial examining Iyengar yoga for young adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Trials. 2011;12:19.

Katchamart W, Johnson S, Lin HJ, et al. Predictors for remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(8):1128-1143.

Wolfe F, Zwillich SH. The long-term outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis: a 23-year prospective, longitudinal study of total joint replacement and its predictors in 1,600 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(6):1072-1082.

Baecklund E, Iliadou A, Askling J, et al. Association of chronic inflammation, not its treatment, with increased lymphoma risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):692-701.

Friedewald VE, Ganz P, Kremer JM, et al. AJC editor's consensus: rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(3):442-447.

Atzeni F, Turiel M, Caporali R, et al. The effect of pharmacological therapy on the cardiovascular system of patients with systemic rheumatic diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9(12):835-839.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2011 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 08 February 2018

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Josef S. Smolen 1 ,

- Daniel Aletaha 1 ,

- Anne Barton 2 ,

- Gerd R. Burmester 3 ,

- Paul Emery 4 , 5 ,

- Gary S. Firestein 6 ,

- Arthur Kavanaugh 6 ,

- Iain B. McInnes 7 ,

- Daniel H. Solomon 8 ,

- Vibeke Strand 9 &

- Kazuhiko Yamamoto 10

Nature Reviews Disease Primers volume 4 , Article number: 18001 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

60k Accesses

1366 Citations

271 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Autoimmunity

- Biological therapy

- Small molecules

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune disease that primarily affects the joints and is associated with autoantibodies that target various molecules including modified self-epitopes. The identification of novel autoantibodies has improved diagnostic accuracy, and newly developed classification criteria facilitate the recognition and study of the disease early in its course. New clinical assessment tools are able to better characterize disease activity states, which are correlated with progression of damage and disability, and permit improved follow-up. In addition, better understanding of the pathogenesis of RA through recognition of key cells and cytokines has led to the development of targeted disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Altogether, the improved understanding of the pathogenetic processes involved, rational use of established drugs and development of new drugs and reliable assessment tools have drastically altered the lives of individuals with RA over the past 2 decades. Current strategies strive for early referral, early diagnosis and early start of effective therapy aimed at remission or, at the least, low disease activity, with rapid adaptation of treatment if this target is not reached. This treat-to-target approach prevents progression of joint damage and optimizes physical functioning, work and social participation. In this Primer, we discuss the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of RA.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 1 digital issues and online access to articles

92,52 € per year

only 92,52 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Global epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Autoinflammation and autoimmunity across rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases

Malmstrom, V., Catrina, A. I. & Klareskog, L. The immunopathogenesis of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis: from triggering to targeting. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17 , 60–75 (2017).

PubMed Google Scholar

Myasoedova, E., Crowson, C. S., Kremers, H. M., Therneau, T. M. & Gabriel, S. E. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955–2007. Arthritis Rheum. 62 , 1576–1582 (2010).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tobon, G. J., Youinou, P. & Saraux, A. The environment, geo-epidemiology, and autoimmune disease: rheumatoid arthritis. J. Autoimmun 35 , 10–14 (2010).

Malemba, J. J. et al . The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo—a population-based study. Rheumatology 51 , 1644–1647 (2012).

Peschken, C. A. & Esdaile, J. M. Rheumatic diseases in North America's indigenous peoples. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 28 , 368–391 (1999).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kawatkar, A. A., Portugal, C., Chu, L.-H. & Iyer, R. Racial/ethnic trends in incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in a large multi-ethnic managed care population [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 64 , S1061 (2012).

Google Scholar

MacGregor, A. J. et al . Characterizing the quantitative genetic contribution to rheumatoid arthritis using data from twins. Arthritis Rheum. 43 , 30–37 (2000).

Stahl, E. A. et al . Bayesian inference analyses of the polygenic architecture of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Genet. 44 , 483–489 (2012).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Padyukov, L. et al . A genome-wide association study suggests contrasting associations in ACPA-positive versus ACPA-negative rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70 , 259–265 (2011).

Gregersen, P. K., Silver, J. & Winchester, R. J. The shared epitope hypothesis: an approach to understanding the molecular genetics of susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 30 , 1205–1213 (1987). This is the single most important paper on the genetics of RA, after the seminal work of Peter Stastny detecting the association between RA and HLA-DR4, and explains the differences in associations found between different populations by a short amino acid sequence common to all these molecules.

Weyand, C. M., Hicok, K. C., Conn, D. L. & Goronzy, J. J. The influence of HLA-DRB1 genes on disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Intern. Med. 117 , 801–806 (1992).

Okada, Y. et al . Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature 506 , 376–381 (2014).

Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature 447 , 661–678 (2007).

Stahl, E. A. et al . Genome-wide association study meta-analysis identifies seven new rheumatoid arthritis risk loci. Nat. Genet. 42 , 508–514 (2010).

Raychaudhuri, S. et al . Genetic variants at CD28, PRDM1 and CD2/CD58 are associated with rheumatoid arthritis risk. Nat. Genet. 41 , 1313–1318 (2009).

Eyre, S. et al . High-density genetic mapping identifies new susceptibility loci for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Genet. 44 , 1336–1340 (2012).

Begovich, A. B. et al . A missense single-nucleotide polymorphism in a gene encoding a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTPN22) is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75 , 330–337 (2004).

Remmers, E. F. et al . STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 357 , 977–986 (2007).

Thomson, W. et al . Rheumatoid arthritis association at 6q23. Nat. Genet. 39 , 1431–1433 (2007).

Barton, A. et al . Rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility loci at chromosomes 10p15, 12q13 and 22q13. Nat. Genet. 40 , 1156–1159 (2008).

Raychaudhuri, S. Recent advances in the genetics of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol 22 , 109–118 (2010).

Karlson, E. W. et al . Cumulative association of 22 genetic variants with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis risk. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69 , 1077–1085 (2010).

Viatte, S. et al . Replication of associations of genetic loci outside the HLA region with susceptibility to anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide-negative rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68 , 1603–1613 (2016).

Viatte, S. et al . Genetic markers of rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility in anti-citrullinated peptide antibody negative patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71 , 1984–1990 (2012).

Trynka, G. et al . Chromatin marks identify critical cell types for fine mapping complex trait variants. Nat. Genet. 45 , 124–130 (2013).

Martin, P. et al . Capture Hi-C reveals novel candidate genes and complex long-range interactions with related autoimmune risk loci. Nat. Commun. 6 , 10069 (2015).

McGovern, A. et al . Capture Hi-C identifies a novel causal gene, IL20RA, in the pan-autoimmune genetic susceptibility region 6q23. Genome Biol. 17 , 212 (2016).

Viatte, S. et al . Association between genetic variation in FOXO3 and reductions in inflammation and disease activity in inflammatory polyarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68 , 2629–2636 (2016).

Krabben, A., Huizinga, T. W. & Mil, A. H. Biomarkers for radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Pharm. Des. 21 , 147–169 (2015).

Lee, J. C. et al . Human SNP links differential outcomes in inflammatory and infectious disease to a FOXO3-regulated pathway. Cell 155 , 57–69 (2013).

Oliver, J., Plant, D., Webster, A. P. & Barton, A. Genetic and genomic markers of anti-TNF treatment response in rheumatoid arthritis. Biomark Med. 9 , 499–512 (2015).

Gomez-Cabrero, D. et al . High-specificity bioinformatics framework for epigenomic profiling of discordant twins reveals specific and shared markers for ACPA and ACPA-positive rheumatoid arthritis. Genome Med. 8 , 124 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al . Epigenome-wide association data implicate DNA methylation as an intermediary of genetic risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 , 142–147 (2013). This paper describes the importance of epigenetic modifications beyond genetic factors in the pathogenesis of RA.

Meng, W. et al . DNA methylation mediates genotype and smoking interaction in the development of anti-citrullinated peptide antibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 19 , 71 (2017).

Frank-Bertoncelj, M. et al . Epigenetically-driven anatomical diversity of synovial fibroblasts guides joint-specific fibroblast functions. Nat. Commun. 8 , 14852 (2017).

Ngo, S. T., Steyn, F. J. & McCombe, P. A. Gender differences in autoimmune disease. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 35 , 347–369 (2014).

Crowson, C. S. et al . The lifetime risk of adult-onset rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 63 , 633–639 (2011).

Alpizar-Rodriguez, D., Pluchino, N., Canny, G., Gabay, C. & Finckh, A. The role of female hormonal factors in the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 56 , 1254–1263 (2017).

Alamanos, Y., Voulgari, P. V. & Drosos, A. A. Incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis, based on the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria: a systematic review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 36 , 182–188 (2006).

Sugiyama, D. et al . Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69 , 70–81 (2010).

Vesperini, V. et al . Association of tobacco exposure and reduction of radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from a French multicenter cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 65 , 1899–1906 (2013).

CAS Google Scholar

Kallberg, H. et al . Smoking is a major preventable risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis: estimations of risks after various exposures to cigarette smoke. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70 , 508–511 (2011).

Sokolove, J. et al . Increased inflammation and disease activity among current cigarette smokers with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional analysis of US veterans. Rheumatology 55 , 1969–1977 (2016).

Svendsen, A. J. et al . Differentially methylated DNA regions in monozygotic twin pairs discordant for rheumatoid arthritis: an epigenome-wide study. Front. Immunol. 7 , 510 (2016).

Jiang, X., Alfredsson, L., Klareskog, L. & Bengtsson, C. Smokeless tobacco (moist snuff) use and the risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: results from a case-control study. Arthritis Care Res. 66 , 1582–1586 (2014).

Naranjo, A. et al . Smokers and non smokers with rheumatoid arthritis have similar clinical status: data from the multinational QUEST-RA database. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 28 , 820–827 (2010).

Stolt, P. et al . Silica exposure is associated with increased risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: results from the Swedish EIRA study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64 , 582–586 (2005).

Webber, M. P. et al . Nested case-control study of selected systemic autoimmune diseases in World Trade Center rescue/recovery workers. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67 , 1369–1376 (2015).

Too, C. L. et al . Occupational exposure to textile dust increases the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: results from a Malaysian population-based case-control study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75 , 997–1002 (2016).

Hajishengallis, G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15 , 30–44 (2015).

Kharlamova, N. et al . Antibodies to Porphyromonas gingivalis indicate interaction between oral infection, smoking, and risk genes in rheumatoid arthritis etiology. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68 , 604–613 (2016).

Konig, M. F. et al . Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans-induced hypercitrullination links periodontal infection to autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Transl Med. 8 , 369ra176 (2016).

Chen, J. et al . An expansion of rare lineage intestinal microbes characterizes rheumatoid arthritis. Genome Med. 8 , 43 (2016).

Scher, J. U. et al . Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. eLife 2 , e01202 (2013).

Pianta, A. et al . Two rheumatoid arthritis-specific autoantigens correlate microbial immunity with autoimmune responses in joints. J. Clin. Invest. 127 , 2946–2956 (2017).

Naciute, M. et al . Frequency and significance of parvovirus B19 infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Gen. Virol. 97 , 3302–3312 (2016).

Gasque, P., Bandjee, M. C., Reyes, M. M. & Viasus, D. Chikungunya pathogenesis: from the clinics to the bench. J. Infect. Dis. 214 (Suppl. 5), S446–S448 (2016).

Tan, E. M. & Smolen, J. S. Historical observations contributing insights on etiopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis and role of rheumatoid factor. J. Exp. Med. 213 , 1937–1950 (2016).

Ljung, L. & Rantapaa-Dahlqvist, S. Abdominal obesity, gender and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis — a nested case-control study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 18 , 277 (2016).

Lu, B., Solomon, D. H., Costenbader, K. H. & Karlson, E. W. Alcohol consumption and risk of incident rheumatoid arthritis in women: a prospective study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66 , 1998–2005 (2014).

Lee, Y. C. et al . Post-traumatic stress disorder and risk for incident rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 68 , 292–298 (2016).

Camacho, E. M., Verstappen, S. M. & Symmons, D. P. Association between socioeconomic status, learned helplessness, and disease outcome in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 64 , 1225–1232 (2012).

Radner, H., Lesperance, T., Accortt, N. A. & Solomon, D. H. Incidence and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 69 , 1510–1518 (2017).

Lopez-Mejias, R. et al . Cardiovascular risk assessment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the relevance of clinical, genetic and serological markers. Autoimmun. Rev. 15 , 1013–1030 (2016).

Sparks, J. A. et al . Rheumatoid arthritis and mortality among women during 36 years of prospective follow-up: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Arthritis Care Res. 68 , 753–762 (2016).

Markusse, I. M. et al . Long-term outcomes of patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis after 10 years of tight controlled treatment: a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 164 , 523–531 (2016).

Masi, A. T. Articular patterns in the early course of rheumatoid arthritis. Am. J. Med. 75 , 16–26 (1983).

Makrygiannakis, D. et al . Smoking increases peptidylarginine deiminase 2 enzyme expression in human lungs and increases citrullination in BAL cells. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67 , 1488–1492 (2008).

Dissick, A. et al . Association of periodontitis with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. J. Periodontol. 81 , 223–230 (2010).

Holers, V. M. Autoimmunity to citrullinated proteins and the initiation of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 25 , 728–735 (2013).

Muller, S. & Radic, M. Citrullinated autoantigens: from diagnostic markers to pathogenetic mechanisms. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 49 , 232–239 (2015).

Trouw, L. A., Huizinga, T. W. & Toes, R. E. Autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis: different antigens — common principles. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72 (Suppl. 2), ii132–ii136 (2013).

Aletaha, D. et al . 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69 , 1580–1588 (2010). This article explains that after almost 25 years, new RA classification criteria were developed in a data-driven, consensus process; these criteria also allow classification of patients with early RA who failed to be classified with the previous criteria.

Nielen, M. M. et al . Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 50 , 380–386 (2004). After the seminal observations of Kimmo Aho on the presence of RF and anti-keratin antibodies (which later became known as ACPAs), this paper reveals that ACPA (and RF) precedes the clinical symptoms of RA by assessing sera from blood donors.

Aletaha, D., Alasti, F. & Smolen, J. S. Rheumatoid factor, not antibodies against citrullinated proteins, is associated with baseline disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17 , 229 (2015).

Laurent, L. et al . IgM rheumatoid factor amplifies the inflammatory response of macrophages induced by the rheumatoid arthritis-specific immune complexes containing anticitrullinated protein antibodies. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74 , 1425–1431 (2015).

Sokolove, J. et al . Rheumatoid factor as a potentiator of anti-citrullinated protein antibody-mediated inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66 , 813–821 (2014).

van Beers, J. J. et al . ACPA fine-specificity profiles in early rheumatoid arthritis patients do not correlate with clinical features at baseline or with disease progression. Arthritis Res. Ther. 15 , R140 (2013).

Deane, K. D. et al . The number of elevated cytokines and chemokines in preclinical seropositive rheumatoid arthritis predicts time to diagnosis in an age-dependent manner. Arthritis Rheum. 62 , 3161–3172 (2010).

de Hair, M. J. et al . Features of the synovium of individuals at risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: implications for understanding preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66 , 513–522 (2014).

Kraan, M. C. et al . Asymptomatic synovitis precedes clinically manifest arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 41 , 1481–1488 (1998).

Arend, W. P. & Firestein, G. S. Pre-rheumatoid arthritis: predisposition and transition to clinical synovitis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 8 , 573–586 (2012).

Steiner, G. Auto-antibodies and autoreactive T-cells in rheumatoid arthritis: pathogenetic players and diagnostic tools. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 32 , 23–36 (2007).

Kinslow, J. D. et al . Elevated IgA plasmablast levels in subjects at risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68 , 2372–2383 (2016).

Shi, J. et al . Anti-carbamylated protein (anti-CarP) antibodies precede the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73 , 780–783 (2014).

Bohler, C., Radner, H., Smolen, J. S. & Aletaha, D. Serological changes in the course of traditional and biological disease modifying therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72 , 241–244 (2013).

Klarenbeek, P. L. et al . Inflamed target tissue provides a specific niche for highly expanded T-cell clones in early human autoimmune disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71 , 1088–1093 (2012).

Ai, R. et al . DNA methylome signature in synoviocytes from patients with early rheumatoid arthritis compared to synoviocytes from patients with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67 , 1978–1980 (2015).

Castor, C. W. The microscopic structure of normal human synovial tissue. Arthritis Rheum. 3 , 140–151 (1960).

McInnes, I. B. & Schett, G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 365 , 2205–2219 (2011).

Bartok, B. & Firestein, G. S. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol. Rev. 233 , 233–255 (2010).

Stanczyk, J. et al . Altered expression of MicroRNA in synovial fibroblasts and synovial tissue in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 58 , 1001–1009 (2008).

Philippe, L. et al . MiR-20a regulates ASK1 expression and TLR4-dependent cytokine release in rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72 , 1071–1079 (2013).

Lefevre, S. et al . Synovial fibroblasts spread rheumatoid arthritis to unaffected joints. Nat. Med. 15 , 1414–1420 (2009).

Ziff, M. Relation of cellular infiltration of rheumatoid synovial membrane to its immune response. Arthritis Rheum. 17 , 313–319 (1974).

Humby, F. et al . Ectopic lymphoid structures support ongoing production of class-switched autoantibodies in rheumatoid synovium. PLOS Med. 6 , e1 (2009).

Randen, I. et al . Clonally related IgM rheumatoid factors undergo affinity maturation in the rheumatoid synovial tissue. J. Immunol. 148 , 3296–3301 (1992).

Catrina, A. I., Ytterberg, A. J., Reynisdottir, G., Malmstrom, V. & Klareskog, L. Lungs, joints and immunity against citrullinated proteins in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 10 , 645–653 (2014).

Orr, C. et al . Synovial tissue research: a state-of-the-art review. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 13 , 463–475 (2017).

Kiener, H. P. et al . Cadherin 11 promotes invasive behavior of fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 60 , 1305–1310 (2009).

Keyszer, G. et al . Differential expression of cathepsins B and L compared with matrix metalloproteinases and their respective inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: a parallel investigation by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. Arthritis Rheum. 41 , 1378–1387 (1998).

Bottini, N. & Firestein, G. S. Duality of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in RA: passive responders and imprinted aggressors. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 9 , 24–33 (2013).

Muller-Ladner, U. et al . Synovial fibroblasts of patients with rheumatoid arthritis attach to and invade normal human cartilage when engrafted into SCID mice. Am. J. Pathol. 149 , 1607–1615 (1996).

Tak, P. P., Zvaifler, N. J., Green, D. R. & Firestein, G. S. Rheumatoid arthritis and p53: how oxidative stress might alter the course of inflammatory diseases. Immunol. Today 21 , 78–82 (2000).

Ai, R. et al . Joint-specific DNA methylation and transcriptome signatures in rheumatoid arthritis identify distinct pathogenic processes. Nat. Commun. 7 , 11849 (2016).

Schett, G. & Gravallese, E. Bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis: mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 8 , 656–664 (2012).

Redlich, K. & Smolen, J. S. Inflammatory bone loss: pathogenesis and therapeutic intervention. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 11 , 234–250 (2012).

Harre, U. et al . Induction of osteoclastogenesis and bone loss by human autoantibodies against citrullinated vimentin. J. Clin. Invest. 122 , 1791–1802 (2012).

Krishnamurthy, A. et al . Identification of a novel chemokine-dependent molecular mechanism underlying rheumatoid arthritis-associated autoantibody-mediated bone loss. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75 , 721–729 (2016).

Hayer, S. et al . Tenosynovitis and osteoclast formation as the initial preclinical changes in a murine model of inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 56 , 79–88 (2007).

Nakano, S. et al . Immunoregulatory role of IL-35 in T cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 54 , 1498–1506 (2015).

Behrens, F. et al . MOR103, a human monoclonal antibody to granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor, in the treatment of patients with moderate rheumatoid arthritis: results of a phase Ib/IIa randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74 , 1058–1064 (2015).

Smolen, J. S., Aletaha, D. & McInnes, I. B. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 388 , 2023–2038 (2016).

Genovese, M. C. et al . Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 374 , 1243–1252 (2016).

Boyle, D. L. et al . The JAK inhibitor tofacitinib suppresses synovial JAK1-STAT signalling in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74 , 1311–1316 (2015).

Genovese, M. C. Inhibition of p38: has the fat lady sung? Arthritis Rheum. 60 , 317–320 (2009).

Genovese, M. C. et al . A phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of 2 dosing regimens of fostamatinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to a tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist. J. Rheumatol. 41 , 2120–2128 (2014).

Firestein, G. S. The disease formerly known as rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 16 , 114 (2014).

Smolen, J. S. et al . Validity and reliability of the twenty-eight-joint count for the assessment of rheumatoid arthritis activity. Arthritis Rheum. 38 , 38–43 (1995).

Koduri, G. et al . Interstitial lung disease has a poor prognosis in rheumatoid arthritis: results from an inception cohort. Rheumatology 49 , 1483–1489 (2010).

Bongartz, T. et al . Incidence and mortality of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 62 , 1583–1591 (2010).

Minichiello, E., Semerano, L. & Boissier, M. C. Time trends in the incidence, prevalence, and severity of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Joint Bone Spine 83 , 625–630 (2016).

Theander, L. et al . Severe extraarticular manifestations in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: risk factors and incidence in relation to treatment with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. J. Rheumatol 44 , 981–987 (2017).

Aggarwal, R. et al . Distinctions between diagnostic and classification criteria? Arthritis Care Res. 67 , 891–897 (2015).

Radner, H., Neogi, T., Smolen, J. S. & Aletaha, D. Performance of the 2010 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73 , 114–123 (2014).

Hazlewood, G. et al . Algorithm for identification of undifferentiated peripheral inflammatory arthritis: a multinational collaboration through the 3e initiative. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 87 , 54–58 (2011).

Kurko, J. et al . Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis — a comprehensive review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 45 , 170–179 (2013).

Aletaha, D. & Smolen, J. S. Joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis progresses in remission according to the Disease Activity Score in 28 joints and is driven by residual swollen joints. Arthritis Rheum. 63 , 3702–3711 (2011).

Gormley, G. J. et al . Can diagnostic triage by general practitioners or rheumatology nurses improve the positive predictive value of referrals to early arthritis clinics? Rheumatology 42 , 763–768 (2003).

Villeneuve, E. et al . A systematic literature review of strategies promoting early referral and reducing delays in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72 , 13–22 (2013).

de Rooy, D. P., van der Linden, M. P., Knevel, R., Huizinga, T. W. & van der Helm-van Mil, A. H. Predicting arthritis outcomes — what can be learned from the Leiden Early Arthritis Clinic? Rheumatology 50 , 93–100 (2011).

van der Helm- van Mil, A. H. et al . A prediction rule for disease outcome in patients with recent-onset undifferentiated arthritis: how to guide individual treatment decisions. Arthritis Rheum. 56 , 433–440 (2007).

van Aken, J. et al . Five-year outcomes of probable rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate or placebo during the first year (the PROMPT study). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73 , 396–400 (2014).

Weinblatt, M. E. Efficacy of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Rheumatol 34 (Suppl. 2), 43–48 (1995).

Visser, K. & van der Heijde, D. Optimal dosage and route of administration of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 68 , 1094–1099 (2009).

van Ede, A. E. et al . Effect of folic or folinic acid supplementation on the toxicity and efficacy of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: a forty-eight week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 44 , 1515–1524 (2001). This study changed the approach to methotrexate therapy, showing that folate substitution does not reduce the efficacy but highly improves the tolerability of methotrexate, thus allowing optimal dosing of the drug.

Felson, D. T. et al . American College of Rheumatology preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 38 , 727–735 (1995).

van der Heijde, D. M. et al . Validity of single variables and composite indices for measuring disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 51 , 177–181 (1992). This article presents the first definition of a continuous measure for disease activity; its derivative, DAS28, became more widely used because it is less time-consuming to evaluate and further simplifications of composite measures were developed with CDAI and SDAI.

Smolen, J. S. et al . A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology 42 , 244–257 (2003).

van der Heide, A. et al . The effectiveness of early treatment with “second-line” antirheumatic drugs. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 124 , 699–707 (1996). This is one of the first studies to reveal the importance of the early institution of DMARD therapy and thus the inappropriateness of the pyramid approach, although patients still had relatively long-standing disease.

Huizinga, W. J., Machold, K. P., Breedveld, F. C., Lipsky, P. E. & Smolen, J. S. Criteria for early rheumatoid arthritis: From Bayes’ law revisited to new thoughts on pathogenesis. (Conference summary). Arthritis Rheum. 46 , 1155–1159 (2002).

Nell, V. et al . Benefit of very early referral and very early therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 43 , 906–914 (2004).

McCarty, D. J. Suppress rheumatoid inflammation early and leave the pyramid to the Egyptians. J. Rheumatol 17 , 1117–1118 (1990).

Grigor, C. et al . Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 364 , 263–269 (2004).

Aletaha, D. et al . Remission and active disease in rheumatoid arthritis: defining criteria for disease activity states. Arthritis Rheum. 52 , 2625–2636 (2005).

Felson, D. T. et al . American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70 , 404–413 (2011). This paper provides a new definition for remission that is sufficiently stringent to be associated with lack of considerable residual disease activity, functional impairment and progression of damage.

Smolen, J. S. et al . Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75 , 3–15 (2016). This study defines the pathways to optimizing disease control in RA on the basis of available evidence and consensus finding,

Elliott, M. J. et al . Randomised double-blind comparison of chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumour necrosis factor alpha (cA2) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 344 , 1105–1110 (1994). This is the first controlled study showing the efficacy of a biological agent in RA — namely, the anti-TNF antibody infliximab.

Maini, R. N. et al . Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 41 , 1552–1563 (1998).

Mierau, M. et al . Assessing remission in clinical practice. Rheumatology 46 , 975–979 (2007).

Verstappen, S. M. M. et al . Intensive treatment with methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: aiming for remission. Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMERA, an open-label strategy trial). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 66 , 1443–1449 (2007).

Klarenbeek, N. B. et al . The impact of four dynamic, goal-steered treatment strategies on the 5-year outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the BeSt study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70 , 1039–1046 (2011).

Smolen, J. S. et al . EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76 , 960–977 (2017).

Singh, J. A. et al . 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 68 , 1–25 (2016).

Lau, C. S. et al . APLAR rheumatoid arthritis treatment recommendations. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 18 , 685–713 (2015).

Smolen, J. S., Aletaha, D., Grisar, J. C., Stamm, T. A. & Sharp, J. T. Estimation of a numerical value for joint damage-related physical disability in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69 , 1058–1064 (2010).

Aletaha, D., Smolen, J. & Ward, M. M. Measuring function in rheumatoid arthritis: identifying reversible and irreversible components. Arthritis Rheum. 54 , 2784–2792 (2006).

Aletaha, D., Alasti, F. & Smolen, J. S. Optimisation of a treat-to-target approach in rheumatoid arthritis: strategies for the 3-month time point. Ann. Rheum. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208324 (2015).

Haraoui, B. et al . Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: a Canadian physician survey. J. Rheumatol. 39 , 949–953 (2012).

Pascual-Ramos, V., Contreras-Yanez, I., Villa, A. R., Cabiedes, J. & Rull-Gabayet, M. Medication persistence over 2 years of follow-up in a cohort of early rheumatoid arthritis patients: associated factors and relationship with disease activity and with disability. Arthritis Res. Ther. 11 , R26 (2009).

Schoenthaler, A. M., Schwartz, B. S., Wood, C. & Stewart, W. F. Patient and physician factors associated with adherence to diabetes medications. Diabetes Educ. 38 , 397–408 (2012).

Kuusalo, L. et al . Impact of physicians’ adherence to treat-to-target strategy on outcomes in early rheumatoid arthritis in the NEO-RACo trial. Scand. J. Rheumatol 44 , 449–455 (2015).

Solomon, D. H. et al . Implementation of treat to target in rheumatoid arthritis through a learning collaborative: results of the TRACTION trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. (in press).

Smolen, J. S. & Aletaha, D. Forget personalised medicine and focus on abating disease activity. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72 , 3–6 (2013).

Van der Heijde, D. M.F. M., van't Hof, M., van Riel, P. L. & van de Putte, L. B. A. Development of a disease activity score based on judgement in clinical practice by rheumatologists. J. Rheumatol 20 , 579–581 (1993).

Prevoo, M. L. L., van't Hof, M. A., Kuper, H. H., van de Putte, L. B. A. & van Riel, P. L.C. M. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 38 , 44–48 (1995).

Bakker, M. F., Jacobs, J. W., Verstappen, S. M. & Bijlsma, J. W. Tight control in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: efficacy and feasibility. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 66 (Suppl. 3), iii56–iii60 (2007).

Smolen, J. S. & Aletaha, D. The assessment of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 28 (Suppl. 59), S18–S27 (2010).

Smolen, J. S. et al . Brief Report: Remission rates with tofacitinib treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison of various remission criteria. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69 , 728–734 (2017).

Smolen, J. S. & Aletaha, D. Interleukin-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab and attainment of disease remission in rheumatoid arthritis: the role of acute-phase reactants. Arthritis Rheum. 63 , 43–52 (2011).

Emery, P. et al . IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67 , 1516–1523 (2008).

Schoels, M., Alasti, F., Smolen, J. S. & Aletaha, D. Evaluation of newly proposed remission cut-points for disease activity score in 28 joints (DAS28) in rheumatoid arthritis patients upon IL-6 pathway inhibition. Arthritis Res. Ther. 19 , 155 (2017).

Studenic, P., Smolen, J. S. & Aletaha, D. Near misses of ACR/EULAR criteria for remission: effects of patient global assessment in Boolean and index-based definitions. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71 , 1702–1705 (2012).

Aletaha, D., Martinez-Avila, J., Kvien, T. K. & Smolen, J. S. Definition of treatment response in rheumatoid arthritis based on the simplified and the clinical disease activity index. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 71 , 1190–1196 (2012).

Dorner, T. et al . The changing landscape of biosimilars in rheumatology. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75 , 974–982 (2016).

Schneider, C. K. Biosimilars in rheumatology: the wind of change. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 72 , 315–318 (2013).

van der Goes, M. C. et al . Monitoring adverse events of low-dose glucocorticoid therapy: EULAR recommendations for clinical trials and daily practice. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69 , 1913–1919 (2010).

Verschueren, P. et al . Methotrexate in combination with other DMARDs is not superior to methotrexate alone for remission induction with moderate-to-high-dose glucocorticoid bridging in early rheumatoid arthritis after 16 weeks of treatment: the CareRA trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74 , 27–34 (2015).

de Jong, P. H. et al . Randomised comparison of initial triple DMARD therapy with methotrexate monotherapy in combination with low-dose glucocorticoid bridging therapy; 1-year data of the tREACH trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73 , 1331–1339 (2014).

Nam, J. L. et al . Remission induction comparing infliximab and high-dose intravenous steroid, followed by treat-to-target: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial in new-onset, treatment-naive, rheumatoid arthritis (the IDEA study). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73 , 75–85 (2014). This is an important study showing that methotrexate plus glucocorticoids is not inferior to methotrexate plus anti-TNF in early RA, thus refuting the use of biological agents before methotrexate.

LaRochelle, G. E. Jr, LaRochelle, A. G., Ratner, R. E. & Borenstein, D. G. Recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in patients with rheumatic diseases receiving low-dose prednisone. Am. J. Med. 95 , 258–264 (1993).

Pincus, T., Sokka, T., Castrejon, I. & Cutolo, M. Decline of mean initial prednisone dosage from 3 to 3.6 mg/day to treat rheumatoid arthritis between 1980 and 2004 in one clinical setting, with long-term effectiveness of dosages less than 5 mg/day. Arthritis Care Res. 65 , 729–736 (2013).

del Rincón, I., Battafarano, D. F., Restrepo, J. F., Erikson, J. M. & Escalante, A. Glucocorticoid dose thresholds associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 66 , 264–272 (2014).

Smolen, J. S. et al . Predictors of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis treated with high-dose methotrexate without or with concomitant infliximab. Results from the ASPIRE trial. Arthritis Rheum. 54 , 702–710 (2006).

Kiely, P., Walsh, D., Williams, R. & Young, A. Outcome in rheumatoid arthritis patients with continued conventional therapy for moderate disease activity—the early RA network (ERAN). Rheumatology 50 , 926–931 (2011).

van der Lubbe, P. A., Dijkmans, B. S., Markusse, H., Nassander, U. & Breedveld, F. C. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of CD4 monoclonal antibody therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 38 , 1097–1106 (1995).

Blanco, F. J. et al . Secukinumab in active rheumatoid arthritis: a phase III randomized, double-blind, active comparator- and placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69 , 1144–1153 (2017).

Bonelli, M. et al . Abatacept (CTLA-4IG) treatment reduces the migratory capacity of monocytes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 65 , 599–607 (2013).

Buch, M. H. et al . Updated consensus statement on the use of rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70 , 909–920 (2011).

Nam, J. L. et al . Efficacy of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76 , 1113–1136 (2017).

Chatzidionysiou, K. et al . Efficacy of glucocorticoids, conventional and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76 , 1102–1107 (2017).

Fleischmann, R. et al . Baricitinib, methotrexate, or combination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and no or limited prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69 , 506–517 (2017).

Fleischmann, R. et al . Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib monotherapy, tofacitinib with methotrexate, and adalimumab with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (ORAL Strategy): a phase 3b/4, double-blind, head-to-head, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 390 , 457–468 (2017).

Weinblatt, M. E. et al . Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a phase IIIb, multinational, prospective, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum. 65 , 28–38 (2013).