- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Effective Transition Words for Research Papers

What are transition words in academic writing?

A transition is a change from one idea to another idea in writing or speaking and can be achieved using transition terms or phrases. These transitions are usually placed at the beginning of sentences, independent clauses, and paragraphs and thus establish a specific relationship between ideas or groups of ideas. Transitions are used to enhance cohesion in your paper and make its logical development clearer to readers.

Types of Transition Words

Transitions accomplish many different objectives. We can divide all transitions into four basic categories:

- Additive transitions signal to the reader that you are adding or referencing information

- Adversative transitions indicate conflict or disagreement between pieces of information

- Causal transitions point to consequences and show cause-and-effect relationships

- Sequential transitions clarify the order and sequence of information and the overall structure of the paper

Additive Transitions

These terms signal that new information is being added (between both sentences and paragraphs), introduce or highlight information, refer to something that was just mentioned, add a similar situation, or identify certain information as important.

Adversative Transitions

These terms and phrases distinguish facts, arguments, and other information, whether by contrasting and showing differences; by conceding points or making counterarguments; by dismissing the importance of a fact or argument; or replacing and suggesting alternatives.

Causal Transitions

These terms and phrases signal the reasons, conditions, purposes, circumstances, and cause-and-effect relationships. These transitions often come after an important point in the research paper has been established or to explore hypothetical relationships or circumstances.

Sequential Transitions

These transition terms and phrases organize your paper by numerical sequence; by showing continuation in thought or action; by referring to previously-mentioned information; by indicating digressions; and, finally, by concluding and summing up your paper. Sequential transitions are essential to creating structure and helping the reader understand the logical development through your paper’s methods, results, and analysis.

How to Choose Transitions in Academic Writing

Transitions are commonplace elements in writing, but they are also powerful tools that can be abused or misapplied if one isn’t careful. Here are some ways to ensure you are using transitions effectively.

- Check for overused, awkward, or absent transitions during the paper editing process. Don’t spend too much time trying to find the “perfect” transition while writing the paper.

- When you find a suitable place where a transition could connect ideas, establish relationships, and make it easier for the reader to understand your point, use the list to find a suitable transition term or phrase.

- Similarly, if you have repeated some terms again and again, find a substitute transition from the list and use that instead. This will help vary your writing and enhance the communication of ideas.

- Read the beginning of each paragraph. Did you include a transition? If not, look at the information in that paragraph and the preceding paragraph and ask yourself: “How does this information connect?” Then locate the best transition from the list.

- Check the structure of your paper—are your ideas clearly laid out in order? You should be able to locate sequence terms such as “first,” “second,” “following this,” “another,” “in addition,” “finally,” “in conclusion,” etc. These terms will help outline your paper for the reader.

For more helpful information on academic writing and the journal publication process, visit Wordvice’s Academic Resources Page. And be sure to check out Wordvice’s professional English editing services if you are looking for paper editing and proofreading after composing your academic document.

Wordvice Tools

- Wordvice APA Citation Generator

- Wordvice MLA Citation Generator

- Wordvice Chicago Citation Generator

- Wordvice Vancouver Citation Generator

- Wordvice Plagiarism Checker

- Editing & Proofreading Guide

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write the Best Journal Submissions Cover Letter

- 100+ Strong Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- How to Write an Abstract

- Which Tense to Use in Your Abstract

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- Common Phrases Used in Academic Writing

Other Resources Around the Web

- MSU Writing Center. Transition Words.

- UW-Madison Writing Center. Transition Words and Phrases.

Transitions

What this handout is about.

In this crazy, mixed-up world of ours, transitions glue our ideas and our essays together. This handout will introduce you to some useful transitional expressions and help you employ them effectively.

The function and importance of transitions

In both academic writing and professional writing, your goal is to convey information clearly and concisely, if not to convert the reader to your way of thinking. Transitions help you to achieve these goals by establishing logical connections between sentences, paragraphs, and sections of your papers. In other words, transitions tell readers what to do with the information you present to them. Whether single words, quick phrases, or full sentences, they function as signs that tell readers how to think about, organize, and react to old and new ideas as they read through what you have written.

Transitions signal relationships between ideas—relationships such as: “Another example coming up—stay alert!” or “Here’s an exception to my previous statement” or “Although this idea appears to be true, here’s the real story.” Basically, transitions provide the reader with directions for how to piece together your ideas into a logically coherent argument. Transitions are not just verbal decorations that embellish your paper by making it sound or read better. They are words with particular meanings that tell the reader to think and react in a particular way to your ideas. In providing the reader with these important cues, transitions help readers understand the logic of how your ideas fit together.

Signs that you might need to work on your transitions

How can you tell whether you need to work on your transitions? Here are some possible clues:

- Your instructor has written comments like “choppy,” “jumpy,” “abrupt,” “flow,” “need signposts,” or “how is this related?” on your papers.

- Your readers (instructors, friends, or classmates) tell you that they had trouble following your organization or train of thought.

- You tend to write the way you think—and your brain often jumps from one idea to another pretty quickly.

- You wrote your paper in several discrete “chunks” and then pasted them together.

- You are working on a group paper; the draft you are working on was created by pasting pieces of several people’s writing together.

Organization

Since the clarity and effectiveness of your transitions will depend greatly on how well you have organized your paper, you may want to evaluate your paper’s organization before you work on transitions. In the margins of your draft, summarize in a word or short phrase what each paragraph is about or how it fits into your analysis as a whole. This exercise should help you to see the order of and connection between your ideas more clearly.

If after doing this exercise you find that you still have difficulty linking your ideas together in a coherent fashion, your problem may not be with transitions but with organization. For help in this area (and a more thorough explanation of the “reverse outlining” technique described in the previous paragraph), please see the Writing Center’s handout on organization .

How transitions work

The organization of your written work includes two elements: (1) the order in which you have chosen to present the different parts of your discussion or argument, and (2) the relationships you construct between these parts. Transitions cannot substitute for good organization, but they can make your organization clearer and easier to follow. Take a look at the following example:

El Pais , a Latin American country, has a new democratic government after having been a dictatorship for many years. Assume that you want to argue that El Pais is not as democratic as the conventional view would have us believe.

One way to effectively organize your argument would be to present the conventional view and then to provide the reader with your critical response to this view. So, in Paragraph A you would enumerate all the reasons that someone might consider El Pais highly democratic, while in Paragraph B you would refute these points. The transition that would establish the logical connection between these two key elements of your argument would indicate to the reader that the information in paragraph B contradicts the information in paragraph A. As a result, you might organize your argument, including the transition that links paragraph A with paragraph B, in the following manner:

Paragraph A: points that support the view that El Pais’s new government is very democratic.

Transition: Despite the previous arguments, there are many reasons to think that El Pais’s new government is not as democratic as typically believed.

Paragraph B: points that contradict the view that El Pais’s new government is very democratic.

In this case, the transition words “Despite the previous arguments,” suggest that the reader should not believe paragraph A and instead should consider the writer’s reasons for viewing El Pais’s democracy as suspect.

As the example suggests, transitions can help reinforce the underlying logic of your paper’s organization by providing the reader with essential information regarding the relationship between your ideas. In this way, transitions act as the glue that binds the components of your argument or discussion into a unified, coherent, and persuasive whole.

Types of transitions

Now that you have a general idea of how to go about developing effective transitions in your writing, let us briefly discuss the types of transitions your writing will use.

The types of transitions available to you are as diverse as the circumstances in which you need to use them. A transition can be a single word, a phrase, a sentence, or an entire paragraph. In each case, it functions the same way: First, the transition either directly summarizes the content of a preceding sentence, paragraph, or section or implies such a summary (by reminding the reader of what has come before). Then, it helps the reader anticipate or comprehend the new information that you wish to present.

- Transitions between sections: Particularly in longer works, it may be necessary to include transitional paragraphs that summarize for the reader the information just covered and specify the relevance of this information to the discussion in the following section.

- Transitions between paragraphs: If you have done a good job of arranging paragraphs so that the content of one leads logically to the next, the transition will highlight a relationship that already exists by summarizing the previous paragraph and suggesting something of the content of the paragraph that follows. A transition between paragraphs can be a word or two (however, for example, similarly), a phrase, or a sentence. Transitions can be at the end of the first paragraph, at the beginning of the second paragraph, or in both places.

- Transitions within paragraphs: As with transitions between sections and paragraphs, transitions within paragraphs act as cues by helping readers to anticipate what is coming before they read it. Within paragraphs, transitions tend to be single words or short phrases.

Transitional expressions

Effectively constructing each transition often depends upon your ability to identify words or phrases that will indicate for the reader the kind of logical relationships you want to convey. The table below should make it easier for you to find these words or phrases. Whenever you have trouble finding a word, phrase, or sentence to serve as an effective transition, refer to the information in the table for assistance. Look in the left column of the table for the kind of logical relationship you are trying to express. Then look in the right column of the table for examples of words or phrases that express this logical relationship.

Keep in mind that each of these words or phrases may have a slightly different meaning. Consult a dictionary or writer’s handbook if you are unsure of the exact meaning of a word or phrase.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Some experts argue that focusing on individual actions to combat climate change takes the focus away from the collective action required to keep carbon levels from rising. Change will not be effected, say some others, unless individual actions raise the necessary awareness.

While a reader can see the connection between the sentences above, it’s not immediately clear that the second sentence is providing a counterargument to the first. In the example below, key “old information” is repeated in the second sentence to help readers quickly see the connection. This makes the sequence of ideas easier to follow.

Sentence pair #2: Effective Transition

Some experts argue that focusing on individual actions to combat climate change takes the focus away from the collective action required to keep carbon levels from rising. Other experts argue that individual actions are key to raising the awareness necessary to effect change.

You can use this same technique to create clear transitions between paragraphs. Here’s an example:

Some experts argue that focusing on individual actions to combat climate change takes the focus away from the collective action required to keep carbon levels from rising. Other experts argue that individual actions are key to raising the awareness necessary to effect change. According to Annie Lowery, individual actions are important to making social change because when individuals take action, they can change values, which can lead to more people becoming invested in fighting climate change. She writes, “Researchers believe that these kinds of household-led trends can help avert climate catastrophe, even if government and corporate actions are far more important” (Lowery).

So, what’s an individual household supposed to do?

The repetition of the word “household” in the new paragraph helps readers see the connection between what has come before (a discussion of whether household actions matter) and what is about to come (a proposal for what types of actions households can take to combat climate change).

Sometimes, transitional words can help readers see how ideas are connected. But it’s not enough to just include a “therefore,” “moreover,” “also,” or “in addition.” You should choose these words carefully to show your readers what kind of connection you are making between your ideas.

To decide which transitional word to use, start by identifying the relationship between your ideas. For example, you might be

- making a comparison or showing a contrast Transitional words that compare and contrast include also, in the same way, similarly, in contrast, yet, on the one hand, on the other hand. But before you signal comparison, ask these questions: Do your readers need another example of the same thing? Is there a new nuance in this next point that distinguishes it from the previous example? For those relationships between ideas, you might try this type of transition: While x may appear the same, it actually raises a new question in a slightly different way.

- expressing agreement or disagreement When you are making an argument, you need to signal to readers where you stand in relation to other scholars and critics. You may agree with another person’s claim, you may want to concede some part of the argument even if you don’t agree with everything, or you may disagree. Transitional words that signal agreement, concession, and disagreement include however, nevertheless, actually, still, despite, admittedly, still, on the contrary, nonetheless .

- showing cause and effect Transitional phrases that show cause and effect include therefore, hence, consequently, thus, so. Before you choose one of these words, make sure that what you are about to illustrate is really a causal link. Novice writers tend to add therefore and hence when they aren’t sure how to transition; you should reserve these words for when they accurately signal the progression of your ideas.

- explaining or elaborating Transitions can signal to readers that you are going to expand on a point that you have just made or explain something further. Transitional words that signal explanation or elaboration include in other words, for example, for instance, in particular, that is, to illustrate, moreover .

- drawing conclusions You can use transitions to signal to readers that you are moving from the body of your argument to your conclusions. Before you use transitional words to signal conclusions, consider whether you can write a stronger conclusion by creating a transition that shows the relationship between your ideas rather than by flagging the paragraph simply as a conclusion. Transitional words that signal a conclusion include in conclusion , as a result, ultimately, overall— but strong conclusions do not necessarily have to include those phrases.

If you’re not sure which transitional words to use—or whether to use one at all—see if you can explain the connection between your paragraphs or sentence either out loud or in the margins of your draft.

For example, if you write a paragraph in which you summarize physician Atul Gawande’s argument about the value of incremental care, and then you move on to a paragraph that challenges those ideas, you might write down something like this next to the first paragraph: “In this paragraph I summarize Gawande’s main claim.” Then, next to the second paragraph, you might write, “In this paragraph I present a challenge to Gawande’s main claim.” Now that you have identified the relationship between those two paragraphs, you can choose the most effective transition between them. Since the second paragraph in this example challenges the ideas in the first, you might begin with something like “but,” or “however,” to signal that shift for your readers.

- picture_as_pdf Transitions

Effective Transitions in Research Manuscripts

- Peer Review

- A transition is a word or phrase that connects consecutive sentences or paragraphs

- Transitions can strengthen your argument by joining ideas and clarifying parts of your manuscript

Updated on June 25, 2013

A transition is a word or phrase that connects consecutive sentences or paragraphs. Effective transitions can clarify the logical flow of your ideas and thus strengthen your argument or explanation. Here, two main transitional tools are discussed: demonstrative pronouns and introductory terms.

Demonstrative pronouns

The demonstrative pronouns this , that , these , and those can be used to emphasize the relationship between adjacent sentences. For example, “Western blotting is a widely used method. This [technique] is favored by protein biochemists.” The use of This or This technique rather than The technique helps to connect the two sentences, indicating that Western blotting is still being discussed in the second sentence. Note that the inclusion of a noun ( technique ) after the pronoun ( this ) decreases ambiguity .

Introductory words or phrases

These transitions are placed at the beginning of the second sentence and are often followed by a comma to improve readability. Introductory words and phrases are distinct from coordinating conjunctions ( and , but , for , nor , or , so , yet ), which are used to bridge two independent clauses within a single sentence rather than two separate sentences. These conjunctions should not be placed at the beginning of a sentence in formal writing. Below are several examples of transitional words and phrases that are frequently used in academic writing, including potential replacements for common informal terms:

To learn more about the special usage of the italicized terms in the table, please see our post on introductory phrases .

Keep in mind that transitions that are similar in meaning are not necessarily interchangeable (such as in conclusion and thus ). A few other transitional words may be particularly helpful when writing lists or describing sequential processes, such as in the methods section of a research paper: next , then , meanwhile , first , second , third , and finally .

In sum, transitions are small additions that can substantially improve the flow of your ideas. However, if your manuscript is not well organized, transitions will not be sufficient to ensure your reader's understanding, so be sure to outline the progression of your ideas before writing.

We hope that this editing tip will help you to integrate effective transitions into your writing. Keep in mind - AJE's English Editing Service specializes in word choice and grammar. Utilize our service for professional help. As always, please email us at [email protected] with any questions.

Michaela Panter, PhD

See our "Privacy Policy"

Transitional Words and Phrases

One of your primary goals as a writer is to present ideas in a clear and understandable way. To help readers move through your complex ideas, you want to be intentional about how you structure your paper as a whole as well as how you form the individual paragraphs that comprise it. In order to think through the challenges of presenting your ideas articulately, logically, and in ways that seem natural to your readers, check out some of these resources: Developing a Thesis Statement , Paragraphing , and Developing Strategic Transitions: Writing that Establishes Relationships and Connections Between Ideas.

While clear writing is mostly achieved through the deliberate sequencing of your ideas across your entire paper, you can guide readers through the connections you’re making by using transitional words in individual sentences. Transitional words and phrases can create powerful links between your ideas and can help your reader understand your paper’s logic.

In what follows, we’ve included a list of frequently used transitional words and phrases that can help you establish how your various ideas relate to each other. We’ve divided these words and phrases into categories based on the common kinds of relationships writers establish between ideas.

Two recommendations: Use these transitions strategically by making sure that the word or phrase you’re choosing matches the logic of the relationship you’re emphasizing or the connection you’re making. All of these words and phrases have different meanings, nuances, and connotations, so before using a particular transitional word in your paper, be sure you understand its meaning and usage completely, and be sure that it’s the right match for your paper’s logic. Use these transitional words and phrases sparingly because if you use too many of them, your readers might feel like you are overexplaining connections that are already clear.

Categories of Transition Words and Phrases

Causation Chronology Combinations Contrast Example

Importance Location Similarity Clarification Concession

Conclusion Intensification Purpose Summary

Transitions to help establish some of the most common kinds of relationships

Causation– Connecting instigator(s) to consequence(s).

accordingly as a result and so because

consequently for that reason hence on account of

since therefore thus

Chronology– Connecting what issues in regard to when they occur.

after afterwards always at length during earlier following immediately in the meantime

later never next now once simultaneously so far sometimes

soon subsequently then this time until now when whenever while

Combinations Lists– Connecting numerous events. Part/Whole– Connecting numerous elements that make up something bigger.

additionally again also and, or, not as a result besides even more

finally first, firstly further furthermore in addition in the first place in the second place

last, lastly moreover next second, secondly, etc. too

Contrast– Connecting two things by focusing on their differences.

after all although and yet at the same time but

despite however in contrast nevertheless nonetheless notwithstanding

on the contrary on the other hand otherwise though yet

Example– Connecting a general idea to a particular instance of this idea.

as an illustration e.g., (from a Latin abbreviation for “for example”)

for example for instance specifically that is

to demonstrate to illustrate

Importance– Connecting what is critical to what is more inconsequential.

chiefly critically

foundationally most importantly

of less importance primarily

Location– Connecting elements according to where they are placed in relationship to each other.

above adjacent to below beyond

centrally here nearby neighboring on

opposite to peripherally there wherever

Similarity– Connecting to things by suggesting that they are in some way alike.

by the same token in like manner

in similar fashion here in the same way

likewise wherever

Other kinds of transitional words and phrases Clarification

i.e., (from a Latin abbreviation for “that is”) in other words

that is that is to say to clarify to explain

to put it another way to rephrase it

granted it is true

naturally of course

finally lastly

in conclusion in the end

to conclude

Intensification

in fact indeed no

of course surely to repeat

undoubtedly without doubt yes

for this purpose in order that

so that to that end

to this end

in brief in sum

in summary in short

to sum up to summarize

Improving Your Writing Style

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Clear, Concise Sentences

Use the active voice

Put the action in the verb

Tidy up wordy phrases

Reduce wordy verbs

Reduce prepositional phrases

Reduce expletive constructions

Avoid using vague nouns

Avoid unneccessarily inflated words

Avoid noun strings

Connecting Ideas Through Transitions

Using Transitional Words and Phrases

Writers' Center

Eastern Washington University

Writing Your Paper: Transitions

- Brainstorming

- Creating a Hook

- Revising, Editing, and Proofreading

Transitions

- Formal Writing

- Active vs. Passive Voice

- Peer Review

- Point of View

Transitions are words and/or phrases used to indicate movement or show change throughout a piece of writing. Transitions generally come at the beginning or end of a paragraph and can do the following:

- Alert readers of connections to, or further evidence for, the thesis

- Function as the topic sentence of paragraphs

- Guide readers through an argument

- Help writers stay on task

Transitions sentences often indicate or signal:

- Change to new topic

- Connection/flow from previous topic

- Continuity of overall argument/thesis

Transitions show connections between ideas. You must create these connections for the reader to move them along with your argument. Without transitions, you are building a house without nails. Things do not hold together.

Transition Words and Phrases

Transitions can signal change or relationship in these ways:

Time - order of events

Examples: while, immediately, never, after, later, earlier, always, soon, meanwhile, during, until now, next, following, once, then, simultaneously, so far

Contrast - show difference

Examples: yet, nevertheless, after all, but, however, though, otherwise, on the contrary, in contrast, on the other hand, at the same time

Compare - show similarity

Examples: in the same way, in like manner, similarly, likewise

Position - show spatial relationships

Examples: here, there, nearby, beyond, wherever, opposite to, above, below

Cause and effect

Examples: because, since, for that reason, therefore, consequently, accordingly, thus, as a result

Conclusion - wrap up/summarize the argument

Writing strong transitions often takes more than simply plugging in a transition word or phrase here and there. In a piece of academic writing, writers often need to use signposts, or transition sentences that signal the reader of connections to the thesis. To form a signpost, combine transition words, key terms from the thesis, and a mention of the previous topic and new topic.

Transition/signpost sentence structure:

[Transition word/phrase] + [previous topic] + [brief restatement of or reference to thesis/argument] + [new topic] = Signpost

- Do not think of this as a hard and fast template, but a general guide to what is included in a good transition.

- Transitions link the topic of the previous paragraph(s) to the topic of the present paragraph(s) and connect both to the overall goal/argument. You'll most often find signposts at the beginning of a paragraph, where they function as topic sentences .

Sample signpost using complimentary transition phrase:

According to [transition phrase] the same overall plan for first defeating Confederate forces in the field and then capturing major cities and rail hubs [overall thesis restated] that Grant followed by marching the Army of the Potomac into Virginia [previous topic] , Sherman likewise [transition word] advanced into Georgia to drive a dagger into the heart of the Confederacy [new topic] .

Contrasting ideas have the same essential format as complimentary but may use different transition words and phrases:

In contrast to [transition phrase] F.D.R., who maintained an ever-vigilant watchfulness over the Manhattan project [previous topic + reference to overall thesis] , Truman took over the presidency without any knowledge of the atomic bomb or its potential power [new topic] .

The overall structure of an essay with transitions may look something like this:

*Note how transitions may come at beginning or end of paragraphs, but either way they signal movement and change.

You can learn more about essay structure HERE .

[ Back to resource home ]

[email protected] 509.359.2779

Cheney Campus JFK Library Learning Commons

Stay Connected!

inside.ewu.edu/writerscenter Instagram Facebook

Transition Resources

Here are a couple of good sites with extensive lists of transition words and phrases:

https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/Transitions.html

Academic Phrasebank http://www.phrasebank.manchester.ac.uk

- << Previous: Structure

- Next: Formal Writing >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 2:50 PM

- URL: https://research.ewu.edu/c.php?g=53658

Research Paper Transition Examples

Searching for effective research paper transition examples? Learn how to make effective transitions between sections of a research paper. There are two distinct issues in making strong transitions:

- Does the upcoming section actually belong where you have placed it?

- Have you adequately signaled the reader why you are taking this next step?

The first is the most important: Does the upcoming section actually belong in the next spot? The sections in your research paper need to add up to your big point (or thesis statement) in a sensible progression. One way of putting that is, “Does the architecture of your paper correspond to the argument you are making?” Getting this architecture right is the goal of “large-scale editing,” which focuses on the order of the sections, their relationship to each other, and ultimately their correspondence to your thesis argument.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

It’s easy to craft graceful transitions when the sections are laid out in the right order. When they’re not, the transitions are bound to be rough. This difficulty, if you encounter it, is actually a valuable warning. It tells you that something is wrong and you need to change it. If the transitions are awkward and difficult to write, warning bells should ring. Something is wrong with the research paper’s overall structure.

After you’ve placed the sections in the right order, you still need to tell the reader when he is changing sections and briefly explain why. That’s an important part of line-by-line editing, which focuses on writing effective sentences and paragraphs.

Examples of Effective Transitions

Effective transition sentences and paragraphs often glance forward or backward, signaling that you are switching sections. Take this example from J. M. Roberts’s History of Europe . He is finishing a discussion of the Punic Wars between Rome and its great rival, Carthage. The last of these wars, he says, broke out in 149 B.C. and “ended with so complete a defeat for the Carthaginians that their city was destroyed . . . .” Now he turns to a new section on “Empire.” Here is the first sentence: “By then a Roman empire was in being in fact if not in name.”(J. M. Roberts, A History of Europe . London: Allen Lane, 1997, p. 48) Roberts signals the transition with just two words: “By then.” He is referring to the date (149 B.C.) given near the end of the previous section. Simple and smooth.

Michael Mandelbaum also accomplishes this transition between sections effortlessly, without bringing his narrative to a halt. In The Ideas That Conquered the World: Peace, Democracy, and Free Markets , one chapter shows how countries of the North Atlantic region invented the idea of peace and made it a reality among themselves. Here is his transition from one section of that chapter discussing “the idea of warlessness” to another section dealing with the history of that idea in Europe.

The widespread aversion to war within the countries of the Western core formed the foundation for common security, which in turn expressed the spirit of warlessness. To be sure, the rise of common security in Europe did not abolish war in other parts of the world and could not guarantee its permanent abolition even on the European continent. Neither, however, was it a flukish, transient product . . . . The European common security order did have historical precedents, and its principal features began to appear in other parts of the world. Precedents for Common Security The security arrangements in Europe at the dawn of the twenty-first century incorporated features of three different periods of the modern age: the nineteenth century, the interwar period, and the ColdWar. (Michael Mandelbaum, The Ideas That Conquered the World: Peace, Democracy, and Free Markets . New York: Public Affairs, 2002, p. 128)

It’s easier to make smooth transitions when neighboring sections deal with closely related subjects, as Mandelbaum’s do. Sometimes, however, you need to end one section with greater finality so you can switch to a different topic. The best way to do that is with a few summary comments at the end of the section. Your readers will understand you are drawing this topic to a close, and they won’t be blindsided by your shift to a new topic in the next section.

Here’s an example from economic historian Joel Mokyr’s book The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress . Mokyr is completing a section on social values in early industrial societies. The next section deals with a quite different aspect of technological progress: the role of property rights and institutions. So Mokyr needs to take the reader across a more abrupt change than Mandelbaum did. Mokyr does that in two ways. First, he summarizes his findings on social values, letting the reader know the section is ending. Then he says the impact of values is complicated, a point he illustrates in the final sentences, while the impact of property rights and institutions seems to be more straightforward. So he begins the new section with a nod to the old one, noting the contrast.

In commerce, war and politics, what was functional was often preferred [within Europe] to what was aesthetic or moral, and when it was not, natural selection saw to it that such pragmatism was never entirely absent in any society. . . . The contempt in which physical labor, commerce, and other economic activity were held did not disappear rapidly; much of European social history can be interpreted as a struggle between wealth and other values for a higher step in the hierarchy. The French concepts of bourgeois gentilhomme and nouveau riche still convey some contempt for people who joined the upper classes through economic success. Even in the nineteenth century, the accumulation of wealth was viewed as an admission ticket to social respectability to be abandoned as soon as a secure membership in the upper classes had been achieved. Institutions and Property Rights The institutional background of technological progress seems, on the surface, more straightforward. (Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress . New York: Oxford University Press, 1990, p. 176)

Note the phrase, “on the surface.” Mokyr is hinting at his next point, that surface appearances are deceiving in this case. Good transitions between sections of your research paper depend on:

- Getting the sections in the right order

- Moving smoothly from one section to the next

- Signaling readers that they are taking the next step in your argument

- Explaining why this next step comes where it does

Return to writing a body of a research paper to see typical transition words and phrases.

Learn how to write a body of a research paper .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

All the Transition Words You'll Ever Need for Academic Writing

In academic writing, transitions are the glue that holds your ideas together. Without them, your writing would be illogical and lack flow, making it difficult for your audience to understand or replicate your research.

In this article, we will discuss the types of transitions based on their purpose. Familiarizing yourself with these most-used and best transition terms for academic writing will help bring clarity to your essays and make the writing process much easier on you.

Types of transitions

There are four types of transitions: Causal, Sequential, Adversative and Additive. Below, we've listed the most commonly used transitions in each of these categories, as well as examples of how they might be used to begin a paragraph or sentence.

When you use causal transitions, you are letting your reader know that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between ideas or paragraphs or consequences.

- Accordingly ("Accordingly, the author states…")

- All else being equal ("All else being equal, these ideas correlate…")

- As a consequence ("As a consequence, all data were aggregated…")

- As a result (of this) ("As a result of this finding, scholars now agree…")

- Because (of the fact that) ("Because of the fact that these numbers show signs of declining,…")

- Because (of this) ("Because of this, scholars determined…")

- Consequently ("Consequently, the research was stalled…")

- Due to (the fact that) ("Due to the fact that all prior studies showed similar results,…")

- For the purpose(s) of ("For the purposes of our argument, we will…")

- For this reason ("For this reason, the researchers…")

- Granted (that) ("Granted that the numbers were significantly higher, the study…")

- Granting (that) ("Granting that the data was collected incorrectly, the researchers felt…")

- If…then ("If this data is significant, then it is obvious that…")

- If so ("If so, the data is not useable…")

- In the event ("In the event that it is not significant, we should consider that…")

- Inasmuch as ("Insomuch as the authors attempt to refute these findings, research suggests that…")

- In the hope that ("In the hope that new data will encourage more in-depth research, the author found that….")

- In that case ("In that case, we've found that…")

- Only if ("Only if data is insubstantial should findings be ignored, thus…")

- Otherwise ("Otherwise, the research would continue…")

- Owing to (the fact) ("Owing to the fact that the gathered data is incorrect, …")

- Provided (that) ("Provided that the same results occur, we can assume that…")

- Since ("Since it would seem futile to continue to study this topic, we posit that…")

- So as to ("So as to clarify past remarks, we initiated further research…")

- So long as ("So long as there is established credibility, this journal seeks….")

- So much (so) that ("The data is manipulated so much so that it can't be used to clarify…")

- Therefore ("Therefore, this result compromises the exploration into…")

- That being the case ("That being the case, we should look into alternatives…")

- Thus ("Thus, it would see that further research…")

- Unless ("Unless this calls to question the original hypothesis, the exploration of this topic would be…")

- With (this fact) in mind ("With this fact in mind, let's consider another alternative…")

- Under those circumstances ("Under those circumstances, fewer participants…")

Sequential transitions show a numerical sequence or the continuation of a thought or action. They are used to establish an order to your main points in an academic essay, and help create a logical outline for your writing.

- (Once) again ("Once again, this is not a reason for lack of rigor…")

- After (this) ("After this, it would seem most prudent to…")

- Afterwards ("Afterwards, it seemed a moot point to determine…")

- Altogether ("Altogether, these data suggest that…")

- Anyway ("Anyway, such loss would prove to be damaging..")

- As (was) mentioned earlier/above ("As was mentioned above, the lack of attention given to…")

- As (was) stated before ("As was stated before, there is little evidence show…")

- As a final point ("As a final point, consider the connection between…")

- At any rate ("At any rate, loss of significance was vital to…")

- By the way ("By the way, one can't assume that…")

- Coincidentally ("Coincidentally, this affected the nature of…")

- Consequently ("Consequently, Smith found that…")

- Eventually ("Eventually, more was needed to sustain…")

- Finally ("Finally, we now know that…"

- First ("First, it seems that even with the additional data…")

- First of all ("First of all, none of the respondents felt that…")

- Given these points ("Given these points, it's easy to see that…")

- Hence ("Hence, we see that the above details…")

- In conclusion ("In conclusion, since the data shows significant growth...")

- In summary ("In summary, there are not enough studies to show the correlation…")

- In the (first/second/third) place ("In the first place, we found that…")

- Incidentally ("Incidentally, no findings showed a positive outlook…")

- Initially ("Initially, we noticed that the authors….")

- Last ("Last, the most significant growth appeared to happen when…")

- Next ("Next, it's important to note that…")

- Overall ("Overall, we found that….")

- Previously ("Previously, it was shown that…")

- Returning to the subject ("Returning to the subject, careful observation of trends…")

- Second ("Second, it was impossible to know the…")

- Secondly ("Secondly, in looking at variable related to…")

- Subsequently ("Subsequently, we found that…")

- Summarizing (this) ("Summarizing this, the authors noted that…")

- Therefore ("Therefore, the connection is unknown between…")

- Third ("Third, when data were collected…")

- Thirdly ("Thirdly, we noticed that…")

- Thus ("Thus, there was no evidence that…)

- To conclude ("To conclude, the findings suggest that…")

- To repeat ("To repeat, no studies found evidence that…")

- To resume ("To resume the conversation, we began discussing…")

- To start with ("To start with, there is no evidence that…")

- To sum up ("To sum up, significant correlation was found…")

- Ultimately ("Ultimately, no studies found evidence of…")

Adversative Transitions

Adversative transitions show contrast, counter arguments or an alternative suggestion.

- Above all ("Above all, we found that…"

- Admittedly ("Admittedly, the findings suggest that…")

- All the same ("All the same, without knowing which direction the study would take…")

- Although ("Although much is to be learned from…")

- At any rate ("At any rate, we concluded that...")

- At least ("At least, with these results, we can…")

- Be that as it may ("Be that as it may, there was no significant correlation between…")

- Besides ("Besides, it is obvious that…")

- But ("But, the causal relationship between…")

- By way of contrast ("By the way of contrast, we note that…")

- Conversely ("Conversely, there was no correlation between…")

- Despite (this) ("Despite this, the findings are clear in that…")

- Either way ("Either way, studies fail to approach the topic from…")

- Even more ("Even more, we can conclude that…")

- Even so ("Even so, there is a lack of evidence showing…")

- Even though ("Even though the participants were unaware of which ….")

- However (However, it becomes clear that…")

- In any case ("In any case, there were enough reponses…")

- In any event ("In any event, we noted that…")

- In contrast ("In contrast, the new data suggests that…")

- In fact ("In fact, there is a loss of…")

- In spite of (this) ("In spite of this, we note that…")

- Indeed ("Indeed, it becomes clear that…")

- Instead (of) ("Instead of publishing our findings early, we chose to")

- More/Most importantly ("More importantly, there have not been any…")

- Nevertheless ("Nevertheless, it becomes clear that…")

- Nonetheless ("Nonetheless, we failed to note how…")

- Notwithstanding (this) ("Notwithstanding this, there was little evidence…")

- On the contrary ("On the contrary, no active users were…")

- On the other hand ("On the other hand, we cannot avoid…")

- Primarily ("Primarily, it becomes significant as…")

- Rather ("Rather, none of this is relevant…")

- Regardless (of) ("Regardless of previous results, the authors…")

- Significantly ("Significantly, there was little correlation between…")

- Still ("Still, nothing was noted in the diary…")

- Whereas ("Whereas little evidence has been given to…")

- While ("While causality is lacking…")

- Yet ("Yet, it becomes clear that…")

Additive Transitions

You'll use an additive transition to relate when new information is being added or highlighted to something that was just mentioned.

- Additionally ("Additionally, it can be noted that…")

- Also ("Also, there was no evidence that….")

- As a matter of fact ("As a matter of fact, the evidence fails to show…")

- As for (this) ("As for this, we can posit that…")

- By the same token ("By the same token, no studies have concluded…")

- Concerning (this) ("Concerning this, there is little evidence to…")

- Considering (this) ("Considering this, we must then return to…")

- Equally ("Equally, there was no correlation…")

- Especially ("Especially, the study reveals that…")

- For example ("For example, a loss of one's….")

- For instance ("For instance, there was little evidence showing…")

- Furthermore ("Furthermore, a lack of knowledge on…")

- In a similar way ("In a similar way, new findings show that…")

- In addition to ("In addition to this new evidence, we note that…")

- In fact ("In fact, none of the prior studies showed…")

- In other words ("In other words, there was a lack of…")

- In particular ("In particular, no relationship was revealed…")

- In the same way ("In the same way, new studies suggest that…")

- Likewise ("Likewise, we noted that…)

- Looking at (this information) ("Looking at this information, it's clear to see how…)

- Moreover ("Moreover, the loss of reputation of…")

- Namely ("Namely, the authors noted that…")

- Not only…but also ("Not only did the study reveal new findings, but also it demonstrated how….")

- Notably ("Notably, no other studies have been done…")

- On the subject of (this) ("On the subject of awareness, participants agreed that….")

- One example (of this is) ("One example of this is how the new data…")

- Particularly ("Particularly, there is little evidence showing…")

- Regarding (this) ("Regarding this, there were concerns that…")

- Similarly ("Similarly, we note that…")

- Specifically ("Specifically, there were responses that…")

- That is ("That is, little attention is given to…")

- The fact that ("The fact that the participants felt misinformed…")

- This means (that) ("This means that conclusive findings are…")

- To illustrate ("To illustrate, one participant wrote that….")

- To put it another way ("To put it another way, there is little reason to…")

- What this means is ("What this means is the authors failed to…")

- With regards to (this) ("With regards to this, we cannot assume that…")

Making the choice

When deciding which transition would best fit in each instance, keep in mind a few of these tips:

- Avoid using the same transition too much, as it could make your writing repetitive.

- Check at the beginning of each paragraph to ensure that a) you've included a transition, if one was needed, and b) it's the correct transition to accurately relate the type of logical connection you're forming between ideas.

- Be sure that if you are using sequential transitions, they match. For example, if you use "first" to highlight your first point, "second" should come next, then "third," etc. You wouldn't want to use "first", followed by "secondly."

Related Posts

How Long Should My Academic Essay Be?

Tips for Writing Scientific Papers

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

4 Types of Transition Words for Research Papers

Researchers often use transition words in academic writing to help guide the reader through text and communicate their ideas well. While these facilitate easy understanding and enhance the flow of the research paper, setting the wrong context with transition words in academic writing can disrupt tone and impact.

So how do you appropriately use transition words in research papers? This article explores the importance of using transitions in academic writing and explains the four types of transition words that can be used by students and researchers to improve their work.

Table of Contents

Why are transition words used in academic writing, additive transitions, adversative transitions, causal transitions, sequential transitions.

Transition words are the key language tools researchers use to communicate their ideas and concepts to readers. They not only reiterate the key arguments being made by the authors but are crucial to improving the structure and flow of the written language. Generally used at the beginning of sentences and paragraphs to form a bridge of communication, transition words can vary depending on your objective, placement, and structuring.

The four types of transition words in academic writing or research papers are additive transitions, adversative transitions, causal transitions, and sequential transitions. Let us look at each of these briefly below.

Types of Transition Words in Academic Writing

These types of transition words are used to inform or alert the reader that new or additional information is being introduced or added to something mentioned in the previous sentence or paragraph. Some examples of words in this category are – moreover, furthermore, additionally, and so on. Phrases like in fact, in addition to, considering this are examples of additive transition phrases that are commonly used.

Used to show contrast, offer alternative suggestions, or present counter arguments and differences, adversative transitions allow researchers to distinguish between different facts, or arguments by establishing or suggesting positions or alternatives opposing them. Examples of adversative transitions include, however, conversely, nevertheless, regardless, rather, and so on. Phrases like on the contrary, in any case, even though provide an adversative transition to arguments in a research paper.

By using causal transitions in their writing, authors can let readers know that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between two or more ideas or paragraphs. It is used to establish the key/important reasons, circumstances, or conditions of the argument being made or while studying hypothetical associations. Since, unless, consequently are some of the words in this type of transitions while in the event that, as a result are some of the causal phrases.

These transition words help to convey the continuation of a thought or action by a numerical sequence by alluding and referring to information or arguments that have been made earlier. Sequential transitions essentially bring order to the researcher’s main points or ideas in the research paper and help to create a logical outline to the arguments. These transition words and phrases essentially guide the reader through the research paper’s key methods, results, and analysis. Some examples of this type of transitions are initially, coincidentally, subsequently and so on. First of all, to conclude, by the way are a few examples of sequential transition phrases.

Researchers must carefully review their research paper, ensuring appropriate and effective use of transition words and phrases in academic writing. During the manuscript editing process, watch for transitions that may be out of context or misplaced. Remember, these words serve as tools to connect ideas and arguments, fostering logical and coherent flow in paragraphs. Double-check the necessity and accuracy of transitions at the beginning of sentences or paragraphs, ensuring they effectively bind and relate ideas and arguments. And finally, avoid repetition of the same transition words in your academic writing.

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- How to Paraphrase Research Papers Effectively

- 3 Easy Ways for Researchers to Improve Their Academic Vocabulary

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

What is a Descriptive Essay? How to Write It (with Examples)

Gift $10, get $10: celebrate thanksgiving with paperpal, you may also like, what is academic writing: tips for students, what is hedging in academic writing , how to use ai to enhance your college..., how to use paperpal to generate emails &..., ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., do plagiarism checkers detect ai content, word choice problems: how to use the right..., how to avoid plagiarism when using generative ai..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai....

The Power of Transition Words: How they connect and clarify your academic writing

Academic writing demands clear communication of ideas to facilitate the exchange of knowledge, and to ensure that information is conveyed accurately and comprehensively. It serves as a vehicle for critical thinking, analysis, and synthesis, allowing scholars to contribute meaningfully to their fields of study. By employing suitable analogies and metaphors, writers can better understand the significance of their craft and strive to hone their skills in order to contribute meaningfully to the academic community. Let’s understand how we can achieve excellence in academic writing by using transition words.

What Are Transition Words?

Transition words are words or phrases that help establish connections between sentences, paragraphs, or ideas in a piece of writing. They act as bridges, guiding readers through the logical flow of information and signalling relationships between different parts of the text. Furthermore, they provide coherence and cohesion to your writing by clarifying the relationships between ideas, adding structure, and improving the overall readability.

Download this FREE infographic and make appropriate use of every transition word to enhance your academic writing.

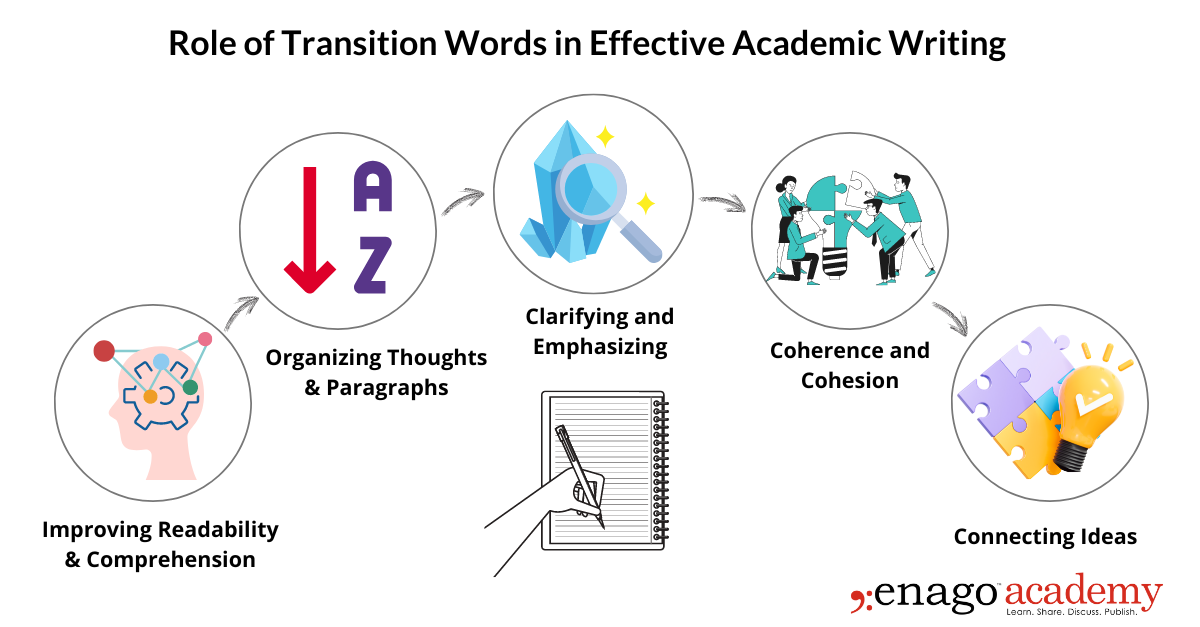

Role of Transition Words in Effective Academic Writing

Transition words play a crucial role in enhancing clarity and coherence in academic writing. They act as linguistic signposts that guide readers through the text, helping them understand the relationships between ideas, and ensuring a smooth flow of information. The primary roles of these words in enhancing clarity and coherence can be summarized as follows:

A. Improving Readability and Comprehension

By facilitating smooth transitions and organizing information effectively, these words enhance the readability and comprehension of academic writing. They help readers navigate through complex texts, understand complex ideas, and follow the structure of the argument. Transition words facilitate reader navigation and comprehension, enhancing the reading experience with increased engagement and accessibility.

B. Organizing Thoughts and Paragraphs

Transition words assist in organizing thoughts and structuring the content of an academic paper. They provide a framework for presenting ideas in a coherent and systematic manner. By indicating sequence, order, or cause and effect relationships, these words help writers create a logical flow that guides readers smoothly from one point to the next. They enable the construction of well-organized paragraphs and facilitate the development of cohesive arguments.

C. Clarifying and Emphasizing

Transition words contribute to the clarity and precision of academic writing. They help define terms, rephrase or restate ideas, and provide necessary explanations. Additionally, they aid in emphasizing key points and drawing attention to important information. By strategically utilizing these words, writers can guarantee clear understanding of their ideas and effective conveyance of the intended message to the reader.

D. Coherence and Cohesion

Transition words are instrumental in creating coherence and cohesion within an academic paper. Coherence refers to the logical and smooth progression of ideas, while cohesion refers to the interconnectedness and unity of the text. They act as cohesive devices, linking sentences and paragraphs together and establishing a cohesive flow of information. They strengthen the logical connections between ideas, prevent abrupt shifts, and enable readers to follow the writer’s argument effortlessly.

E. Connecting Ideas

Transition words bridge the gap between sentences, paragraphs, and sections of an academic paper. They establish logical connections, indicating how ideas are related and allowing readers to follow the author’s train of thought. Whether showing addition, similarity, contrast, or example, these words help readers navigate between concepts and comprehend the overall message more effectively.

Types of Transition Words in Academic Writing

The types of transition words vary based on the situations where you can use them to enhance the effectiveness of your academic writing.

1. Addition

“Addition” transition words are used to introduce additional information or ideas that support or supplement the main point being discussed. They serve to expand upon the topic, provide further evidence, or present examples that strengthen your claims.

Examples of Addition Transition Words:

- Furthermore, the study not only analyzed the effects of X but also examined the impact of Y.

- Moreover, the results not only confirmed the initial hypothesis but also revealed additional insights.

- Additionally, previous research has shown consistent findings, strengthening the validity of our study.

2. Comparison and Contrast

“Comparison and Contrast” transition words are used in academic writing when you want to highlight similarities, differences, or relationships between different concepts, ideas, or findings. They help to establish clear connections and facilitate the comparison and contrast of various elements within your research.

Examples of Comparison and Contrast Transition Words:

- Similarly, other researchers have reported comparable findings, corroborating the generalizability of our results.

- In contrast, previous studies have demonstrated consistent patterns, reinforcing the existing body of knowledge.

- In comparison, the current study offers a unique perspective by examining the relationship from a different angle.

3. Cause and Effect

“Cause and Effect” transition words are used when you want to demonstrate the relationship between a cause and its resulting effect or consequence. They help to clarify the cause-and-effect relationship, allowing readers to understand the connections between different variables, events, or phenomena.

Examples of Cause and Effect Transition Words:

- As a result, the data provides compelling evidence for a causal relationship between X and Y.

- Consequently, the hypothesis can be supported by the observed patterns in the collected data.

- Hence, the proposed model is validated, given the consistent and statistically significant results.

4. Example and Illustration

“Example and Illustration” transition words are used when you want to provide specific instances, evidence, or illustrations to support and clarify your main points or arguments. These words help to make your ideas more tangible and concrete by presenting real-life examples or specific cases.

Examples of “Example and Illustration” Transition Words:

- For example, one study conducted by Jackson et al. (2018) demonstrated a similar phenomenon in a different context.

- To illustrate this point, consider the case of Company X, which experienced similar challenges in implementing the proposed strategy.

- In particular, the data highlights the importance of considering demographic factors, such as age and gender, in the analysis.

5. Sequence and Chronology

“Sequence and Chronology” transition words are used in academic research papers when you want to indicate the order, progression, or sequence of events, ideas, or processes. These words help to organize information in a logical and coherent manner, ensuring that readers can follow the chronological flow of your research.

Examples of “Sequence and Chronology” Transition Words:

- First and foremost, the study aims to examine the long-term effects of intervention X on outcome Y.

- Subsequently, the participants were randomly assigned to either the control or experimental group.

- Finally, the data analysis revealed significant temporal trends that require further investigation.

6. Clarification and Restatement

“Clarification and Restatement” transition words are used in academic writing when you want to provide further explanation, clarify a point, or restate an idea in a different way. These words ensure that readers understand your arguments and ideas clearly, avoiding any ambiguity or confusion.

Examples of “Clarification and Restatement” Transition Words:

- In other words, the phenomenon can be explained by the interplay of various psychological and environmental factors.

- Specifically, the term “efficiency” refers to the ability to achieve maximum output with minimum resource utilization.

- To clarify, the concept of “sustainability” encompasses the ecological, economic, and social dimensions of development.

7. Emphasis

“Emphasis” transition words are used when you want to place special emphasis on certain points, ideas, or findings. These words help to draw attention to key information, highlight the significance of particular aspects, or underscore the importance of your arguments.

Examples of Emphasis Transition Words:

- Notably, this study addresses a significant gap in the existing literature.

- Importantly, the findings have implications for future policy decisions.

- In particular, the study examined the relationship between age and cognitive performance.

8. Summary and Conclusion

“Summary and Conclusion” transition words are employed in academic writing when you want to provide a concise summary of the main points discussed in your paper and draw a conclusion based on the findings or arguments presented. These help to signal the end of your paper and provide closure to your research.

Examples of “Summary and Conclusion” Transition Words

- In conclusion, the findings unequivocally support the initial hypothesis, emphasizing the significance of the proposed theory.

- Overall, the results indicate a consistent pattern, providing a foundation for future research in this area.

- In summary, this research makes a valuable contribution to the existing literature by extending our understanding of the topic.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Using Transition Words in Academic Writing

When using transition words in academic writing, it’s important to be mindful of common mistakes to ensure that your writing remains clear, cohesive, and effective.

1. Overusing Transition Words

Using too many transition words can make your writing appear cluttered and disrupt the flow of your ideas. Avoid overloading your sentences or paragraphs with excessive transitions. Instead, use them strategically to enhance clarity and coherence.

2. Using Inappropriate or Irrelevant Transitions

Choose transition words that are appropriate for the context and purpose of your writing. Avoid using them when they don’t align with the relationship between the ideas you are connecting. Ensure that the transitions you use are relevant and contribute to the overall coherence of your writing.

3. Neglecting Proofreading and Editing

As with any aspect of writing, proofreading and editing are crucial when using transition words. Carefully review your writing to ensure that you use transitions correctly and effectively. Look for any inconsistencies, redundancies, or errors in your use of transitions and make necessary revisions.

4. Failing to Understand the Meaning

It’s important to understand the precise meaning and usage of transition words before incorporating them into your writing. Using a transition word incorrectly or inappropriately can lead to confusion or misinterpretation. Therefore, it is important to consult reliable resources or style guides to familiarize yourself with the correct usage of each of these words.

5. Neglecting the Logical Flow

Transition words should help guide the reader through your writing and create a logical flow of ideas. Failing to use appropriate transitions can result in a disjointed or fragmented presentation. Ensure that your transitions establish clear connections and maintain the coherence of your writing.

6. Relying Only on Transition Words

While transition words are valuable tools, they should not replace effective writing and organization. Relying solely on transitions to connect your ideas can lead to weak or poorly structured writing. Focus on developing strong topic sentences, clear paragraph organization, and logical progression of ideas alongside the use of these words.

7. Ignoring Sentence Variety

Use transition words to enhance the variety and sophistication of your sentence structures. Avoid using the same words repeatedly, as this can make your writing monotonous. Instead, explore different transitions that convey the specific relationships between your ideas.

In essence, the strategic use of transition words is a powerful tool that connects and clarifies your academic writing. Furthermore, it elevates your work from a mere collection of ideas to a cohesive, well-structured, and thought-provoking piece of scholarship. By mastering the art of using these words effectively, you can enhance the impact of your academic writing and contribute meaningfully to your field of study.

What are your thoughts on other grammar nuances that can make academic writing more effective? Share your opinion in the comments below or write an article on our Open Platform !

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Trending Now

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

Concept Papers in Research: Deciphering the blueprint of brilliance

Concept papers hold significant importance as a precursor to a full-fledged research proposal in academia…

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI…

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing Transitions

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Good transitions can connect paragraphs and turn disconnected writing into a unified whole. Instead of treating paragraphs as separate ideas, transitions can help readers understand how paragraphs work together, reference one another, and build to a larger point. The key to producing good transitions is highlighting connections between corresponding paragraphs. By referencing in one paragraph the relevant material from previous paragraphs, writers can develop important points for their readers.

It is a good idea to continue one paragraph where another leaves off. (Instances where this is especially challenging may suggest that the paragraphs don't belong together at all.) Picking up key phrases from the previous paragraph and highlighting them in the next can create an obvious progression for readers. Many times, it only takes a few words to draw these connections. Instead of writing transitions that could connect any paragraph to any other paragraph, write a transition that could only connect one specific paragraph to another specific paragraph.

Complete List of Transition Words

100 Words and Phrases to Use Between Paragraphs

Viorika Prikhodko / E+ / Getty Images

- Writing Essays

- Writing Research Papers

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

Once you have completed the first draft of your paper, you will need to rewrite some of the introductory sentences at the beginning and the transition statements at the end of every paragraph . Transitions, which connect one idea to the next, may seem challenging at first, but they get easier once you consider the many possible methods for linking paragraphs together—even if they seem to be unrelated.

Transition words and phrases can help your paper move along, smoothly gliding from one topic to the next. If you have trouble thinking of a way to connect your paragraphs, consider a few of these 100 top transitions as inspiration. The type of transition words or phrases you use depends on the category of transition you need, as explained below.

Additive Transitions

Probably the most common type, additive transitions are those you use when you want to show that the current point is an addition to the previous one, notes Edusson , a website that provides students with essay-writing tips and advice . Put another way, additive transitions signal to the reader that you are adding to an idea and/or your ideas are similar, says Quizlet , an online teacher and student learning community. Some examples of additive transition words and phrases were compiled by Michigan State University writing lab. Follow each transition word or phrase with a comma:

- In the first place

- Furthermore

- Alternatively

- As well (as this)

- What is more

- In addition (to this)

- On the other hand

- Either (neither)

- As a matter of fact

- Besides (this)

- To say nothing of

- Additionally

- Not to mention (this)

- Not only (this) but also (that) as well

- In all honesty

- To tell the truth

An example of additive transitions used in a sentence would be:

" In the first place , no 'burning' in the sense of combustion, as in the burning of wood, occurs in a volcano; moreover , volcanoes are not necessarily mountains; furthermore , the activity takes place not always at the summit but more commonly on the sides or flanks..." – Fred Bullard, "Volcanoes in History, in Theory, in Eruption"

In this and the examples of transitions in subsequent sections, the transition words or phrases are printed in italics to make them easier to find as you peruse the passages.

Adversative Transitions

Adversative transitions are used to signal conflict, contradiction, concession, and dismissal, says Michigan State University. Examples include:

- In contrast

- But even so

- Nevertheless

- Nonetheless

- (And) still

- In either case

- (Or) at least

- Whichever happens

- Whatever happens

- In either event

An example of an adversative transition phrase used in a sentence would be: