Advertisement

Unemployment Scarring Effects: An Overview and Meta-analysis of Empirical Studies

- Review article

- Published: 17 May 2023

Cite this article

- Mattia Filomena ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4099-9168 1 , 2

833 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article reviews the empirical literature on the scarring effects of unemployment, by first presenting an overview of empirical evidence relating to the impact of unemployment spells on subsequent labor market outcomes and then exploiting meta-regression techniques. Empirical evidence is homogeneous in highlighting significant and often persistent wage losses and strong unemployment state dependence. This is confirmed by a meta-regression analysis under the assumption of a common true effect. Heterogeneous findings emerge in the literature, related to the magnitude of these detrimental effects, which are particularly penalizing in terms of labor earnings in case of unemployment periods experienced by laid-off workers. We shed light on further sources of heterogeneity and find that unemployment is particularly scarring for men and when studies’ identification strategy is based on selection on observables.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The gender pay gap in the USA: a matching study

Katie Meara, Francesco Pastore & Allan Webster

The effect of health on economic growth: a meta-regression analysis

Masagus M. Ridhwan, Peter Nijkamp, … Luthfi M.Irsyad

Hidden costs of entering self-employment: the spouse’s psychological well-being

Safiya Mukhtar Alshibani, Ingebjørg Kristoffersen & Thierry Volery

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Moreover, further outcomes discussed by the literature on scarring are family formation, crime and negative psychological implications in terms of well-being, life satisfaction and mental health (see e.g. Helbling and Sacchi 2014 ; Strandh et al. 2014 ; Mousteri et al. 2018 ; Clark and Lepinteur 2019 ).

A further strand of the recent literature focuses on the effect of adverse labor market conditions at graduation, for example focusing on the effect of local unemployment rate or graduating during a recession (see e.g. Raaum and Roed, 2006 ; Kahn 2010 ; Oreopoulos et al. 2012 ; Kawaguchi and Murao 2014 ; Altonji et al. 2016 ). The consequences of economic downturns on wages, labor supply and social outcomes for young labor market entrants have been recently surveyed by Cockx ( 2016 ), Von Wachter (2020) and Rodriguez et al. ( 2020 ).

The stigma effect means that individuals who have been unemployed face lower chances of being hired because employers may use their past history of unemployment as a negative signal.

Thus, papers using traditional multivariate descriptive analysis, duration models, or OLS regressions with a reduced number of controls which do not properly address endogeneity issues and are unlikely to have a causal interpretation (endogeneity issues are discussed in SubSect. 3.2 ).

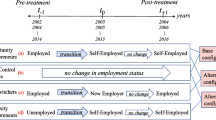

For intergenerational scars we mean that studies focused on the effect of parents’ unemployment experiences on the children’ future employment status (see e.g. Karhula et al. 2017 ). For macroeconomic conditions at graduation we mean that we excluded that literature focused on the local unemployment rate at graduation or other local labor market conditions, rather than on individual unemployment experience and state dependence (see e.g. Oreopoulos et al. 2012 ; Raaem and Roed, 2006 ).

When we could not directly retrieve the t -statistics because not reported among the study results, we computed them as the ratio between the estimated unemployment effects ( \({\beta }_{i}\) ) and their standard errors. If studies only displayed the estimated effects and their 95% confidence intervals, the standard error can be calculated by SE = ( ub − lb )/(2 × 1.96), where ub and lb are the upper bound and the lower bound, respectively.

We removed from the meta-regression analysis 8 articles because they did not contain sufficient information to compute the t -statistic of the estimated scarring effect. They are reported in italics in Tables 5 and 6 .

For employment outcomes we mean the likelihood of experiencing future unemployment, the probability to have a job later (employability), the fraction of days spent at work or the hours worked during the following years (labor market participation), the call-backs from employers in case of field experiment. Earning outcomes include hourly wages, labor earnings, income, etc.

Since many studies did not provide precise information on the number of covariates, we approximated \({dk}_{i}\) with the number of observations minus 2. Indeed, given that in microeconometric applications the sample sizes are very often much larger than the number of the parameters, the calculation of the partial correlation coefficient is quite robust to errors in deriving \({dk}_{i}\) (Picchio 2022 ).

The publication bias is the bias arising from the tendency of editors to publish more easily findings consistent with a conventional view or with statistically significant results, whereas studies that find small or no significant effects tend to remain unpublished (Card and Krueger 1995 ).

We employed the Precision Effect Estimate with Standard Error (PEESE) specification because its quadratic form of the standard errors has been proven to be less biased and often more efficient to check for heterogeneity than the FAT-PET specification when there is a nonzero genuine effect (Stanley and Doucouliagos 2014 ). Nevertheless, the results from the FAT-PET specification are very similar to the ones from the PEESE model.

Abebe DS, Hyggen C (2019) Moderators of unemployment and wage scarring during the transition to young adulthood: evidence from Norway. In: Hvinden B, Oreilly J, Schoyen MA, Hyggen C (eds) Negotiating early job insecurity. Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Google Scholar

Adascalitei D, Morano CP (2016) Drivers and effects of labour market reforms: evidence from a novel policy compendium. IZA J Labor Policy 5(1):1–32

Article Google Scholar

Ahmad N (2014) State dependence in unemployment. Int J Econ Financ Issues 4(1):93

Altonji JG, Kahn LB, Speer JD (2016) Cashier or consultant? Entry labor market conditions, field of study, and career success. J Law Econ 34(1):S361–S401

Arranz JM, García-Serrano C (2003) Non-employment and subsequent wage losses. Instituto de Estudios Fiscales, No. 19-03

Arranz JM, Davia MA, García-Serrano C (2005) Labour market transitions and wage dynamics in Europe. ISER Working Paper Series, No. 2005-17

Arulampalam W (2001) Is unemployment really scarring? Effects of unemployment experiences on wages. Econ J 111(475):F585–F606

Arulampalam W, Booth AL, Taylor MP (2000) Unemployment persistence. Oxf Econ Pap 52(1):24–50

Arulampalam W, Gregg P, Gregory M (2001) Introduction: unemployment scarring. Econ J 111(475):F577–F584

Ayllón S (2013) Unemployment persistence: not only stigma but discouragement too. Appl Econ Lett 20(1):67–71

Ayllón S, Valbuena J, Plum A (2021) Youth unemployment and stigmatization over the business cycle in Europe. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 84(1):103–129

Baert S, Verhaest D (2019) Unemployment or overeducation: which is a worse signal to employers? De Econ 167(1):1–21

Baumann I (2016) The debate about the consequences of job displacement. Springer, Cham, pp 1–33

Becker, Gary. 1975. Human capital: a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Second Edition. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Biewen M, Steffes S (2010) Unemployment persistence: is there evidence for stigma effects? Econ Lett 106(3):188–190

Birkelund GE, Heggebø K, Rogstad J (2017) Additive or multiplicative disadvantage? The scarring effects of unemployment for ethnic minorities. Eur Sociol Rev 33(1):17–29

Borland J (2020) Scarring effects: a review of Australian and international literature. Aust J Labour Econ 23(2):173–188

Bratberg E, Nilsen OA (2000) Transitions from school to work and the early labour market experience. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 62:909–929

Brodeur A, Cook N, Heyes A (2020) Methods matter: p-hacking and publication bias in causal analysis in economics. Am Econ Rev 110(11):3634–3660

Brodeur A, Lé M, Sangnier M, Zylberberg Y (2016) Star wars: the empirics strike back. Am Econ J Appl Econ 8(1):1–32

Burda MC, Mertens A (2001) Estimating wage losses of displaced workers in Germany. Labour Econ 8(1):15–41

Burdett K (1978) A theory of employee job search and quit rates. Am Econ Rev 68(1):212–220

Böheim R, Taylor MP (2002) The search for success: do the unemployed find stable employment? Labour Econ 9(6):717–735

Cameron CA, Gelbach JB, Miller DL (2008) Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Rev Econ Stat 90(3):414–427

Card D, Krueger AB (1995) Time-series minimum-wage studies: a meta-analysis. Am Econ Rev 85(2):238–243

Chamberlain G (1984) Panel data. Handb Econ 2:1247–1318

Clark AE, Lepinteur A (2019) The causes and consequences of early-adult unemployment: evidence from cohort data. J Econ Behav Organ 166:107–124

Cockx B, Picchio M (2013) Scarring effects of remaining unemployed for long-term unemployed school-leavers. J R Stat Soc A Stat Soc 176(4):951–980

Cockx B (2016) Do youths graduating in a recession incur permanent losses? IZA World Labor

Couch KA (2001) Earnings losses and unemployment of displaced workers in Germany. ILR Rev 54(3):559–572

Deelen A, de Graaf-Zijl M, van den Berge W (2018) Labour market effects of job displacement for prime-age and older workers. IZA J Labor Econ 7(1):3

Dieckhoff M (2011) The effect of unemployment on subsequent job quality in Europe: a comparative study of four countries. Acta Sociol 54(3):233–249

Doiron D, Gørgens T (2008) State dependence in youth labor market experiences, and the evaluation of policy interventions. J Econometr 145(1–2):81–97

Dorsett R, Lucchino P (2018) Young people’s labour market transitions: the role of early experiences. Labour Econ 54:29–46

Doucouliagos H (1995) Worker participation and productivity in labor-managed and participatory capitalist firms: a meta-analysis. ILR Rev 49(1):58–77

Eicher TS, Papageorgiou C, Raftery AE (2011) Default priors and predictive performance in Bayesian model averaging, with application to growth determinants. J Appl Economet 26(1):30–55

Eliason M, Storrie D (2006) Lasting or latent scars? Swedish evidence on the long-term effects of job displacement. J Law Econ 24(4):831–856

Eriksson S, Rooth D-O (2014) Do employers use unemployment as a sorting criterion when hiring? Evidence from a field experiment. Am Econ Rev 104(3):1014–1039

Fallick BC (1996) A review of the recent empirical literature on displaced workers. ILR Rev 50(1):5–16

Farber HS, Herbst CM, Silverman D, Von Watcher T (2019) Whom do employers want? The role of recent employment and unemployment status and age. J Law Econ 37(2):323–349

Farber HS, Silverman D, Von Watcher T (2016) Determinants of callbacks to job applications: an audit study. Am Econ Rev 106(5):314–318

Farber HS, Silverman D, Von Watcher T (2017) Factors determining callbacks to job applications by the unemployed: an audit study. RSF Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci 3(3):168–201

Filomena M, Picchio M (2022) Retirement and health outcomes in a meta-analytical framework. J Econ Surv (forthcoming)

Fraja De, Gianni SL, Rockey J (2021) The wounds that do not heal: the lifetime scar of youth unemployment. Economica 88(352):896–941

Gangji A, Plasman R (2008) Microeconomic analysis of unemployment persistence in Belgium. Int J Manpow 29(3):280–298

Gangji A, Plasman R (2007) The Matthew effect of unemployment: how does it affect wages in Belgium. DULBEA Working Papers 07-19.RS, ULB—Universite Libre de Bruxelles

Gangl M (2004) Welfare states and the scar effects of unemployment: a comparative analysis of the United States and West Germany. Am J Sociol 109(6):1319–1364

Gangl M (2006) Scar effects of unemployment: an assessment of institutional complementarities. Am Sociol Rev 71(6):986–1013

Gartell M (2009) Unemployment and subsequent earnings for Swedish college graduates. A study of scarring effects. Arbetsrapport 2009:2, Institute for Futures Studies

Gaure S, Røed K, Westlie L (2008) The impacts of labor market policies on job search behavior and post-unemployment job quality. IZA Discussion Papers 3802, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA)

Ghirelli C (2015) Scars of early non-employment for low educated youth: evidence and policy lessons from Belgium. IZA J Eur Labor Stud 4(1):20

Gibbons R, Katz LF (1991) Layoffs and lemons. J Law Econ 9(4):351–380

Gregg P (2001) The impact of youth unemployment on adult unemployment in the NCDS. Econ J 111(475):F626–F653

Gregg P, Tominey E (2005) The wage scar from male youth unemployment. Labour Econ 12(4):487–509

Gregory M, Jukes R (2001) Unemployment and subsequent earnings: estimating scarring among British men 1984–94. Econ J 111(475):607–625

Guvenen F, Karahan F, Ozkan S, Song J (2017) Heterogeneous scarring effects of full-year nonemployment. Am Econ Rev 107(5):369–373

Hamermesh DS (1989) What do we know about worker displacement in the US? Ind Relat J Econ Soc 28(1):51–59

Havránek T, Horvath R, Irsova Z, Rusnak M (2015) Cross-country heterogeneity in intertemporal substitution. J Int Econ 96(1):100–118

Havránek T, Stanley TD, Doucouliagos H, Bom P, Geyer-Klingeberg J, Ichiro Iwasaki W, Reed R, Rost K, van Aert RCM (2020) Reporting guidelines for meta-analysis in economics. J Econ Surv 34(3):469–475

Heckman JJ (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47(1):153–161

Helbling LA, Sacchi S (2014) Scarring effects of early unemployment among young workers with vocational credentials in Switzerland. Emp Res Voc Educ Train 6(1):12

Heylen V (2011) Scarring, the effects of early career unemployment. In ECPR General conference, 2011/08/24–2011/08/27, University of Iceland, Reykjavik

Hämäläinen K (2003) Education and unemployment: state dependence in unemployment among young people in the 1990s. VATT Institute for Economic Research, No. 312

Jacobson LS, LaLonde RJ, Sullivan DG (1993) Earnings losses of displaced workers. Am Econ Rev 83(4):685–709

Jovanovic B (1979a) Firm-specific capital and turnover. J Polit Econ 87(6):1246–1260

Jovanovic B (1979b) Job matching and the theory of turnover. J Polit Econ 87(5, Part 1):972–990

Kahn LB (2010) The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy. Labour Econ 17(2):303–316

Karhula A, Lehti H, Erola J (2017) Intergenerational scars? The long-term effects of parental unemployment during a depression. Res Finn Soc 10:87–99

Kawaguchi D, Murao T (2014) Labor-market institutions and long-term effects of youth unemployment. J Money Credit Bank 46(S2):95–116

Kletzer LG (1998) Job displacement. J Econ Perspect 12(1):115–136

Kletzer LG, Fairlie RW (2003) The long-term costs of job displacement for young adult workers. ILR Rev 56(4):682–698

Knights S, Harris MN, Loundes J (2002) Dynamic relationships in the Australian labour market: heterogeneity and state dependence. Econ Record 78(242):284–298

Kroft K, Lange F, Notowidigdo MJ (2013) Duration dependence and labor market conditions: evidence from a field experiment. Q J Econ 128(3):1123–1167

Kuchibhotla M, Orazem PF, Ravi S (2020) The scarring effects of youth joblessness in Sri Lanka. Rev Dev Econ 24(1):269–287

Lazear EP (1986) Raids and offer matching. In: Ehrenberg R (ed) Research in Labor Economics, vol 8. JAI Press, Greenwich

Lockwood B (1991) Information externalities in the labour market and the duration of unemployment. Rev Econ Stud 58(4):733–753

De Luca G, Magnus JR (2011) Bayesian model averaging and weighted-average least squares: equivariance, stability, and numerical issues. Stata Journal 11(4):518–544

Lupi C, Ordine P (2002) Unemployment scarring in high unemployment regions. Econ Bull 10(2):1–8

Magnus JR, De Luca G (2016) Weighted-average least squares (WALS): a survey. J Econ Surv 30(1):117–148

Magnus JR, Powell O, Prüfer P (2010) A comparison of two model averaging techniques with an application to growth empirics. J Econometr 154(2):139–153

Manzoni A, Mooi-Reci I (2011) Early unemployment and subsequent career complexity: a sequence-based perspective. Schmollers Jahrbuch J Appl Soc Sci Stud ZeitschrFür Wirtschaftsund Sozialwissenschaften 131(2):339–348

Mavromaras K, Sloane P, Wei Z (2015) The scarring effects of unemployment, low pay and skills under-utilization in Australia compared. Appl Econ 47(23):2413–2429

Mincer J (1974) Schooling, experience, and earnings. National Bureau of Economic Research Inc, Cambridge

Mooi-Reci I, Ganzeboom HB (2015) Unemployment scarring by gender: human capital depreciation or stigmatization? Longitudinal evidence from the Netherlands, 1980–2000. Soc Sci Res 52:642–658

Mortensen DT (1987) Job search and labor market analysis. In: Ashenfelter O, Layard R (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 2, Chapter 15, pp 849–919, Elsevier

Mortensen DT (1988) Wages, separations, and job tenure: on-the-job specific training or matching? J Law Econ 6(4):445–471

Mousteri V, Daly M, Delaney L (2018) The scarring effect of unemployment on psychological well-being across Europe. Soc Sci Res 72:146–169

Mroz TA, Savage TH (2006) The long-term effects of youth unemployment. J Hum Resour 41(2):259–293

Mundlak Y (1978) On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econometrica 69–85

Möller J, Umkehrer M (2015) Are there long-term earnings scars from youth unemployment in Germany? Jahrbücher Für Nationalökon Und Stat 235(4–5):474–498

Nekoei A, Weber A (2017) Does extending unemployment benefits improve job quality? American Economic Review 107(2):527–561

Nickell S, Jones P, Quintini G (2002) A picture of job insecurity facing British men. Econ J 112(476):1–27

Nilsen ØA, Reiso KH (2014) Scarring effects of early-career unemployment. Nord Econ Policy Rev 1:13–46

Nordström Skans O (2011) Scarring effects of the first labor market experience. IZA Discussion Papers 5565, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA)

Nunley JM, Pugh A, Romero N, Alan Seals R (2017) The effects of unemployment and underemployment on employment opportunities: results from a correspondence audit of the labor market for college graduates. ILR Rev 70(3):642–669

Nüß P (2018) Duration dependence as an unemployment stigma: evidence from a field experiment in Germany. Technical report, Economics Working Paper.

Oberholzer-Gee F (2008) Nonemployment stigma as rational herding: a field experiment. J Econ Behav Organ 65(1):30–40

Omori Y (1997) Stigma effects of nonemployment. Econ Inq 35(2):394–416

Ordine P, Rose G (2015) Educational mismatch and unemployment scarring. Int J Manpower 36(5):733

Oreopoulos P, Von Watcher T, Heisz A (2012) The short- and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4(1):1–29

Pastore F, Quintano C, Rocca A (2021) Some young people have all the luck! The duration dependence of the school-to-work transition in Europe. Labour Econ 70:101982

Petreski M, Mojsoska-Blazevski N, Bergolo M (2017) Labor-market scars when youth unemployment is extremely high: evidence from Macedonia. East Eur Econ 55(2):168–196

Picchio M, van Ours JC (2013) Retaining through training even for older workers. Econ Educ Rev 32(1):29–48

Picchio M (2022) Meta-analysis. In: Zimmermann KF (eds) Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics. Springer, Cham. (forthcoming)

Pissarides CA (1992) Loss of skill during unemployment and the persistence of employment shocks. Q J Econ 107(4):1371–1391

Plum A, Ayllón S (2015) Heterogeneity in unemployment state dependence. Econ Lett 136:85–87

Raaum O, Røed K (2006) Do business cycle conditions at the time of labor market entry affect future employment prospects? Rev Econ Stat 88(2):193–210

Rodriguez JS, Colston J, Wu Z, Chen Z (2020) Graduating during a recession: a literature review of the effects of recessions for college graduates. Centre for College Workforce Transitions (CCWT), University of Wisconsin

Schmillen A, Umkehrer M (2017) The scars of youth: effects of early-career unemployment on future unemployment experience. Int Labour Rev 156(3–4):465–494

Shi LP, Wang S (2021) Demand-side consequences of unemployment and horizontal skill mismatches across national contexts: an employer-based factorial survey experiment. Soc Sci Res 104:102668

Spence M (1973) Job market signaling. Q J Econ 87(3):355–374

Spivey C (2005) Time off at what price? The effects of career interruptions on earnings. ILR Rev 59(1):119–140

Stanley TD (2005) Beyond publication bias. J Econ Surv 19(3):309–345

Stanley TD (2008) Meta-regression methods for detecting and estimating empirical effects in the presence of publication selection. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 70(1):103–127

Stanley TD, Doucouliagos H (2014) Meta-regression approximations to reduce publication selection bias. Res Synth Methods 5(1):60–78

Stewart MB (2007) The interrelated dynamics of unemployment and low-wage employment. J Appl Economet 22(3):511–531

Strandh M, Winefield A, Nilsson K, Hammarström A (2014) Unemployment and mental health scarring during the life course. Eur J Pub Health 24(3):440–445

Tanzi GM (2022) Scars of youth non-employment and labour market conditions. Italian Econ J (forthcoming)

Tatsiramos K (2009) Unemployment insurance in Europe: unemployment duration and subsequent employment stability. J Eur Econ Assoc 7(6):1225–1260

Tumino A (2015) The scarring effect of unemployment from the early’90s to the great recession. ISER Working Paper Series, No. 2015-05

Ugur M (2014) Corruption’s direct effects on per-capita income growth: a meta-analysis. J Econ Surv 28(3):472–490

Verho J (2008) Scars of recession: the long-term costs of the Finnish economic crisis. Working Paper Series 2008:9, IFAU—Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy

Vishwanath T (1989) Job search, stigma effect, and escape rate from unemployment. J Law Econ 7(4):487–502

Von Wachter T (2020) The persistent effects of initial labor market conditions for young adults and their sources. J Econ Perspect 34(4):168–194

Vooren M, Haelermans C, Groot W, van den Brink HM (2019) The effectiveness of active labor market policies: a meta-analysis. J Econ Surv 33(1):125–149

Webb MD (2014) Reworking wild bootstrap based inference for clustered errors. Queen’s Economics Department Working Paper No. 1315, Kingston, Canada

Wooldridge JM (2005) Simple solutions to the initial conditions problem in dynamic, nonlinear panel data models with unobserved heterogeneity. J Appl Economet 20(1):39–54

Xue X, Cheng M, Zhang W (2021) Does education really improve health? A meta-analysis. J Econ Surv 35(1):71–105

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges financial support from the Cariverona Foundation Ph.D. research scholarship. He is particularly grateful to Matteo Picchio and Claudia Pigini for their comments and suggestions on a preliminary version of this paper. He also thanks the Associate Editor Massimiliano Bratti and two anonymous reviewers, whose comments were very useful for an important improvement of the paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics and Social Sciences, Marche Polytechnic University, Piazzale Martelli 8, 60121, Ancona, Italy

Mattia Filomena

Department of Public Economics, Masaryk University, Lipová 41a, 60200, Brno, Czech Republic

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mattia Filomena .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

See Tables 5 and 6 .

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Filomena, M. Unemployment Scarring Effects: An Overview and Meta-analysis of Empirical Studies. Ital Econ J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00228-4

Download citation

Received : 09 April 2022

Accepted : 15 April 2023

Published : 17 May 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00228-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Unemployment scarring effects

- State dependence

- Earning penalties

- Causal effect

- Meta-analysis

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

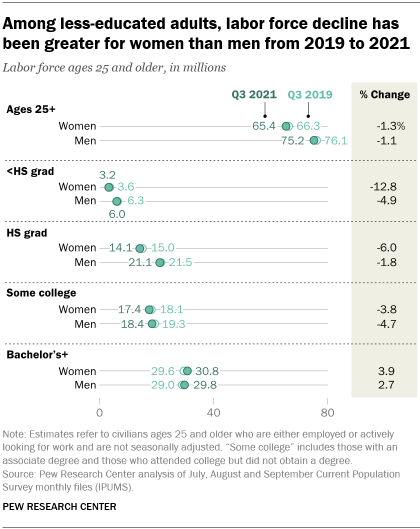

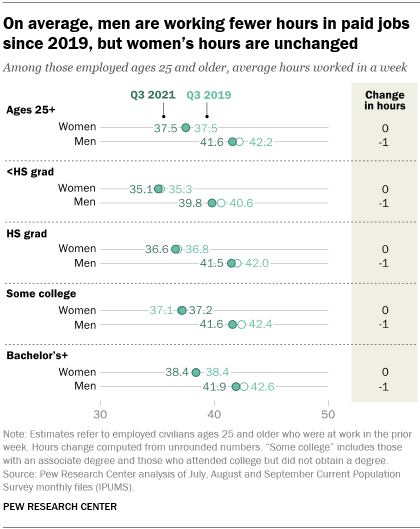

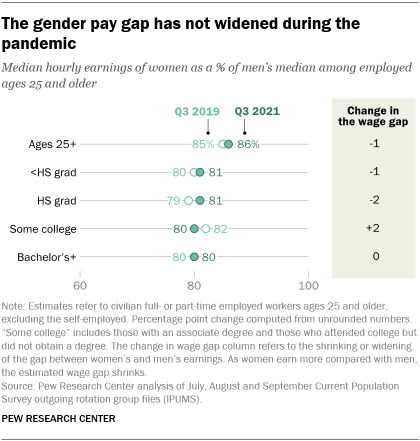

The Pandemic's Impact on Unemployment and Labor Force Participation Trends

Following early 2020 responses to the pandemic, labor force participation declined dramatically and has remained below its 2019 level, whereas the unemployment rate recovered briskly. We estimate the trend of labor force participation and unemployment and find a substantial impact of the pandemic on estimates of trend. It turns out that levels of labor force participation and unemployment in 2021 were approaching their estimated trends. A return to 2019 levels would then represent a tight labor market, especially relative to long-run demographic trends that suggest further declines in the participation rate.

At the end of 2019, the labor market was hotter than it had been in years. Unemployment was at a historic low, and participation in the labor market was finally increasing after a prolonged decline. That tight labor market came to an abrupt halt with the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020.

Now, two years later, the labor market has mostly recovered from the depths of the pandemic recession. The unemployment rate is close to pre-pandemic lows, and job openings are at record highs. Yet, participation and employment rates have remained persistently below pre-pandemic levels. This suggests the possibility that the pandemic has permanently reduced participation in the economy and that current participation rates reflect a new normal. In this article, we explore how the pandemic has affected labor markets and whether a new normal is emerging.

What Is "Normal"?

One way to define the normal level of a variable is to estimate its trend and compare the observed data with the estimated trend values. Constructing a trend essentially means drawing a smooth line through the variations in the actual data.

But this means that constructing the trend for a point in time typically involves considering what happened both before and after that point in time. Thus, constructing the trend at the end of a sample is especially hard, since we do not yet know how the data will evolve.

We construct trends for three aggregate labor market ratios — the labor force participation (LFP) rate, the unemployment rate and the employment-population ratio (EPOP) — using methods described in our 2019 article " Projecting Unemployment and Demographic Trends ."

First, we estimate statistical models for LFP and unemployment rates of demographic groups defined by age, gender and education. For each gender and education, we decompose its unemployment and LFP into cyclical components common to all age groups and smooth local trends for age and cohort effects.

Second, we aggregate trends from the estimates of the group-specific trends. Specifically, we construct the trend for the aggregate LFP rate as the population-share-weighted sum of the corresponding estimated trends for demographic groups. We construct the aggregate unemployment rate and EPOP trends from the group-specific LFP and unemployment trends and the groups' population shares.

In our previous work, we estimated the trends for the unemployment rate and LFP rate of a gender-education group separately using maximum likelihood methods. The estimates reported in this article are based on the joint estimation of LFP and unemployment rate trends using Bayesian methods.

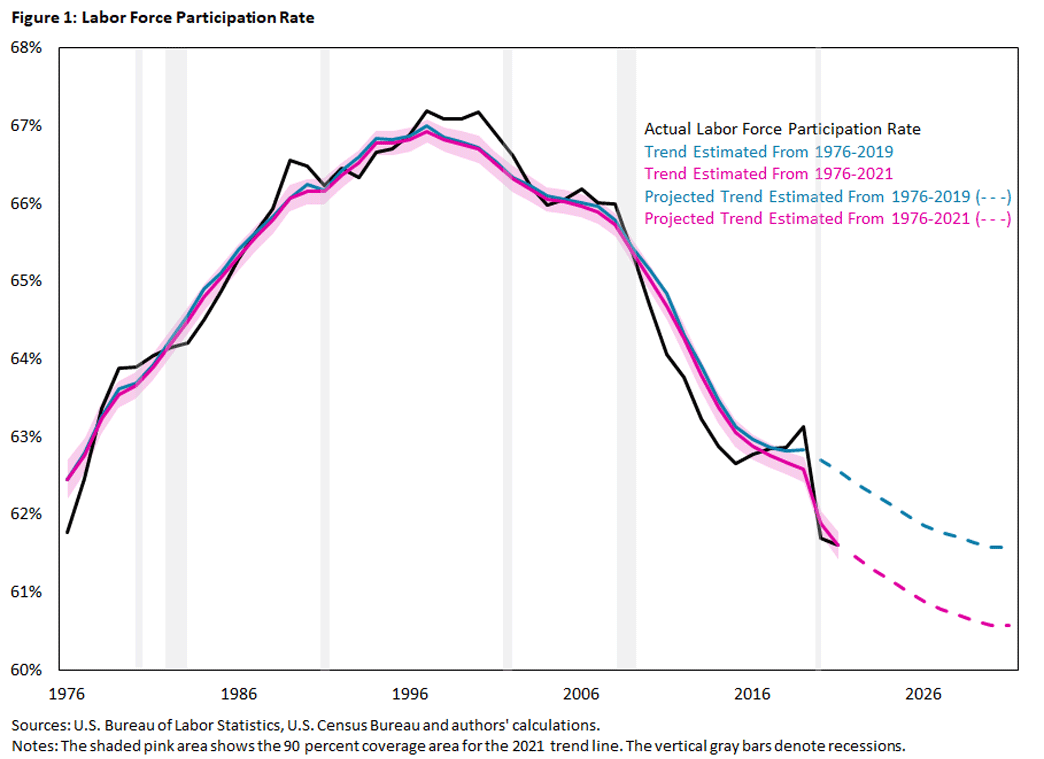

We separately estimate the trends using data from 1976 to 2019 (pre-pandemic) and from 1976 to 2021 (including the pandemic period). Figures 1, 2 and 3 display annual averages for the three aggregate labor market ratios — the LFP rate, the unemployment rate and EPOP, respectively — from 1976 to 2021.

In each figure, the solid black line denotes the observed values, and the blue and pink lines denote the estimated trend using data from 1976 up to and including 2019 and 2021, respectively. The estimated trends are subject to uncertainty, and the plotted trends represent the median estimate of the trend.

For the estimates based on data up to 2021, we also include the 90 percent coverage area shown as the shaded pink area. According to the statistical model, there is a 90 percent probability that the trend is contained in the coverage area. The blue and pink dotted lines represent our projections on how the labor market ratios will evolve until 2031, again based on the estimated trend up to and including 2019 and 2021. The shaded gray vertical areas highlight recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Pre-Pandemic Trends: 1976-2019

We start with the pre-pandemic trends for the LFP rate and unemployment rate estimated for data from 1976 through 2019. After a long recovery from the 2007-09 recession, the LFP rate was 63.1 percent in 2019 (slightly above the estimated trend value of 62.8 percent), and the unemployment rate was 3.7 percent (noticeably below its estimated trend value of 4.7 percent).

The LFP rate being above trend and the unemployment rate being below trend reflects the characterization of the 2019 labor market as "hot." But note that even though the LFP rate exceeded its trend value in 2019, it was still lower than during the 2007-09 period. This difference is accounted for by the declining trend in the LFP rate.

As noted in our 2019 article , LFP rates and unemployment rates differ systematically across demographic groups. Participation rates tend to be higher for younger, more-educated workers and for men. Unemployment rates tend to be lower for men and for the older and more-educated population.

Thus, changes in the population composition over time — that is, the relative size of demographic groups — will affect the aggregate LFP and unemployment rates, in addition to changes in the LFP and unemployment rate trends of the demographic groups.

As also noted in our 2019 article, the hump-shaped trend of the aggregate LFP rate reflects a variety of forces:

- Prior to 1990, the aggregate LFP rate was boosted by an upward trend in the LFP rate of women. But after 1990, the LFP rate of women began declining. Combining this with declining trend LFP rates for other demographic groups has reduced the aggregate LFP rate.

- Changes in the age distribution had a limited impact prior to 2005, but the aging population since then has lowered the aggregate LFP rate substantially.

- Increasing educational attainment has contributed positively to aggregate LFP throughout the period.

The steady decline of the unemployment rate trend reflects mostly the contributions from an older and more-educated population and, to some extent, a decline in the trend unemployment rates of demographic groups.

Pre-Pandemic Expectations of Future LFP and Unemployment Trends

Our statistical model of smooth local trends for the LFP and unemployment rates of demographic groups has the property that the best forecast for future trend values of demographic groups is their last estimated trend value. Thus, the model will only predict a change in the trend of aggregate ratios if the population shares of its constituent groups are changing.

We combine the U.S. Census Bureau population forecasts for the gender-age groups with an estimated statistical model of education shares for gender-age groups to forecast population shares of our demographic groups from 2020 to 2031 (the dotted blue lines in Figures 1 and 2).

As we can see, the changing demographics alone imply further reductions of 1 percentage point and 0.2 percentage points in the trend LFP rate and unemployment rate, respectively. This projection is driven by the forecasted aging of the population, which is only partially offset by the forecasted higher educational attainment.

Based on data up to 2019, the same aggregate LFP rates in 2021 as in 2019 would have represented a substantial cyclical deviation upward from the pre-pandemic trends.

It is notable that the unemployment rate is much more volatile relative to its trend than the LFP rate is. In other words, cyclical deviations from trend are much more pronounced for the unemployment rate than for the LFP rate.

In fact, in our estimation, the behavior of the unemployment rate determines the common cyclical component of both the unemployment rate and the LFP rate. Whereas the unemployment rate spikes in recessions, the LFP rate response is more muted and tends to lag recessions. This feature will be important for interpreting how the estimated trend LFP rate changed with the pandemic.

Finally, Figure 3 combines the information from the LFP rate and unemployment rate and plots actual and trend rates for EPOP. On the one hand, given the relatively small trend decline of the unemployment rate, the trend for EPOP mainly reflects the trend for the LFP rate and inherits its hump-shaped path and the projected decline over the next 10 years. On the other hand, EPOP inherits the volatility from the unemployment rate. In 2019, EPOP is notably above trend, by about 1 percentage point.

Unemployment and Labor Force Participation During the Pandemic

The behavior of unemployment resulting from the pandemic-induced recession was different from past recessions:

- The entire increase in unemployment between February and April 2020 was accounted for by the increase in unemployment from temporary layoffs. This differed from previous recessions, when a spike in permanent layoffs led the bulge of unemployment in the trough.

- The recovery started in May 2020, and the speed of recovery was also much faster than in previous recessions. After only seven months, unemployment declined by 8 percentage points.

- The behavior of the unemployment rate is reflected in the 2020 recession being the shortest NBER recession on record: It lasted for two months (March to April 2020).

To summarize, the runup and decline of the unemployment rate during the pandemic were unusually rapid, but the qualitative features were not that different from previous recessions after properly accounting for temporary layoffs, as noted in the 2020 working paper " The Unemployed With Jobs and Without Jobs . "

The decline in the LFP rate was sharp and persistent. The LFP rate dropped from 63.4 percent in February 2020 to 60.2 percent in April 2020, an unprecedented drop during such a short period of time. After a rebound to 61.7 percent in August 2020, the LFP rate essentially moved sideways and remained below 62 percent until the end of 2021.

The large drop in the aggregate LFP rate has been attributed to, among others:

- More people — especially women — leaving the labor force to care for children because of school closings or to care for relatives at increased health risk, as noted in the 2021 work " Assessing Five Statements About the Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Women (PDF) " and the 2021 article " Caregiving for Children and Parental Labor Force Participation During the Pandemic "

- An increase in retirement due to health concerns, as noted in the 2021 working paper " How Has COVID-19 Affected the Labor Force Participation of Older Workers? "

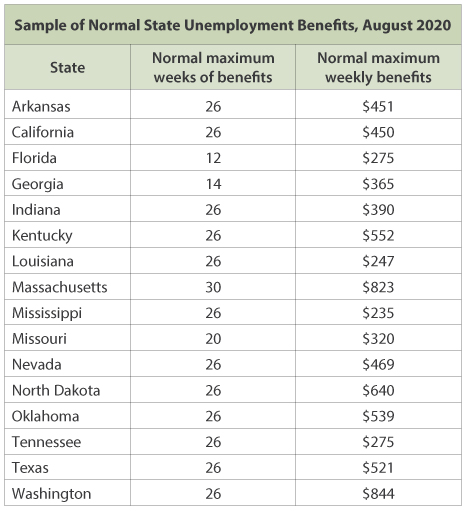

- Generous pandemic income transfers and unemployment insurance programs, as noted in the 2021 article " COVID Transfers Dampening Employment Growth, but Not Necessarily a Bad Thing "

All of these factors might impact the participation trend, but by how much?

The Pandemic's Effect on Trend Estimates for LFP and Unemployment

The aggregate trend assessment for the LFP and unemployment rates has changed considerably as a result of 2020 and 2021. Repeating the estimation of trend and cycle for our demographic groups using data from 1976 up to 2021 yields the pink trend lines in Figures 1 and 2.

The updated trend estimates now put the positive cyclical gap in 2019 for LFP at 0.5 percentage points (rather than 0.3 percentage points) and the negative cyclical gap for the unemployment rate at 1.4 percentage points (rather than 1 percentage point). That is, by this estimate of the trend, the labor market in 2019 was even hotter than by the estimates from the 1976-2019 period.

In 2021, the actual LFP rate is essentially at trend, and the unemployment rate is only slightly above trend. That is, by this estimate of the trend, the labor market is relatively tight.

Notice that even though the new 2021 trend estimates for both the LFP and the unemployment rates differ noticeably from the trend values predicted for 2021 based on data up to 2019, the trend revisions for the LFP rate are limited to more recent years, whereas the trend revisions for the unemployment rate apply to the whole sample.

The difference in revisions is related to how confident we can be about the estimated trends. The 90 percent coverage area is quite narrow for the LFP rate for the entire sample up to the last four years. Thus, there is no need to drastically revise the estimated trend prior to 2017.

On the other hand, the 90 percent coverage area for the trend unemployment rate is quite broad throughout the sample. That is, a wide range of values for trend unemployment is potentially consistent with observed unemployment values. Consequently, the last two observations lead to a wholesale reassessment of the level of the trend unemployment rate.

Another way to frame the 2020-21 trend revisions is as follows. The unemployment rate is very cyclical, deviations from trend are large, and though the sharp increase and decline of the unemployment rate in 2020-21 is unusual, an upward level shift of the trend unemployment rate best reflects the additional pandemic data.

The LFP rate, however, is usually not very cyclical, and it is only weakly related to the unemployment rate. Since the model assumes that the cyclical response does not change over the sample, it then attributes the large 2020-21 drop of the LFP rate to a decline in its trend and ultimately to a decline of the trend LFP rates of most demographic groups.

Finally, the EPOP trend is again mainly determined by the LFP trend, seen in Figure 3. Including the pandemic years noticeably lowers the estimated trend for the years from 2017 onwards. The cyclical gap in 2019 is now estimated to be 1.4 percentage points, and 2021 EPOP is close to its estimated trend.

What Does the Future Hold?

In our framework, current estimates of trend LFP and the unemployment rate for demographic groups are the best forecasts of future rates. Combined with projected demographic changes, this implies a continued noticeable downward trend for the LFP rate and a slight downward trend for the unemployment rate.

The trend unemployment rate is low, independent of how we estimate the trend. But given the highly unusual circumstances of the pandemic, the model may well overstate the decline in the trend LFP rate. Therefore, it is likely that the "true" trend lies somewhere between the trends estimated using data up to 2019 and data up to 2021.

That being a possibility, it remains that labor markets as of now have been unusually tight by most other measures, such as nominal wage growth and posted job openings relative to hires. This suggests that the true trend is closer to the revised 2021 trend than to the 2019 trend. In other words, the LFP rate and unemployment rate at the end of 2021 relative to the 2021 estimate of trend LFP and unemployment rate are consistent with a tight labor market.

Andreas Hornstein is a senior advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Marianna Kudlyak is a research advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Hornstein, Andreas; and Kudlyak, Marianna. (April 2022) "The Pandemic's Impact on Unemployment and Labor Force Participation Trends." Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief , No. 22-12.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

V iews expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Subscribe to Economic Brief

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.

By submitting this form you agree to the Bank's Terms & Conditions and Privacy Notice.

Thank you for signing up!

As a new subscriber, you will need to confirm your request to receive email notifications from the Richmond Fed. Please click the confirm subscription link in the email to activate your request.

If you do not receive a confirmation email, check your junk or spam folder as the email may have been diverted.

Phone Icon Contact Us

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Far-Reaching Impact of Job Loss and Unemployment *

Jennie e. brand.

University of California – Los Angeles

Job loss is an involuntary disruptive life event with a far-reaching impact on workers’ life trajectories. Its incidence among growing segments of the workforce, alongside the recent era of severe economic upheaval, has increased attention to the effects of job loss and unemployment. As a relatively exogenous labor market shock, the study of displacement enables robust estimates of associations between socioeconomic circumstances and life outcomes. Research suggests that displacement is associated with subsequent unemployment, long-term earnings losses, and lower job quality; declines in psychological and physical well-being; loss of psychosocial assets; social withdrawal; family disruption; and lower levels of children’s attainment and well-being. While reemployment mitigates some of the negative effects of job loss, it does not eliminate them. Contexts of widespread unemployment, although associated with larger economic losses, lessen the social-psychological impact of job loss. Future research should attend more fully to how the economic and social-psychological effects of displacement intersect and extend beyond displaced workers themselves.

A central tradition of research in sociology and economics seeks to identify and take account of the processes shaping socioeconomic outcomes, including the mechanisms that affect mobility and define opportunity structures. A notable strand of this research has assessed the extent to which job loss, often accompanied by a period of unemployment, divides the career achievement of workers. With the recent severe economic upheaval came a precipitous increase in attention to the study of job loss and unemployment. Much of this work has understandably focused on economic outcomes as indicated by employment levels and earnings, but another important body of research has attended to the wider impact of job loss.

A few definitions help fix ideas. Job separation includes both voluntary (worker initiated job separation, or “quitting”) and involuntary job termination. Job loss is generally understood as indicating involuntary separation that occurs when workers are fired or laid off, where layoffs occur as a result of firms downsizing, restructuring, closing plants or relocating. Involuntary job loss may also indicate job separation as a result of health conditions. In this case, the separation may be worker initiated, but nevertheless be considered to some degree involuntary. Job displacement is a specific form of involuntary job loss that does not include workers being fired or termination for health reasons; it is reserved for involuntary job separation that is the result of economic and business conditions that are largely beyond the control of the individual worker and thus presumably less governed by worker performance. Strict definitions include some period of pre-displacement firm-specific tenure, such as three years in the Displaced Worker Survey of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Some studies on job loss focus attention on involuntary job loss, while others focus more specifically on job displacement. I nevertheless use these terms somewhat interchangeably throughout this review, as the distinctions are not always explicitly made in the literature and are to some degree amorphous.

Individual-level (involuntary) unemployment occurs when individuals are without a job and actively seeking employment; some definitions allow discouraged workers who have dropped out of the labor force to be counted among the unemployed, or at least among the jobless. Unemployment is one potential consequence of job loss. Job loss, as opposed to unemployment, is a discrete event and is not synonymous with unemployment. A period (at times a prolonged period) of unemployment typically, but not necessarily, accompanies job loss. However, unemployment is not necessarily preceded by job loss, and displaced workers are not generally representative of the unemployed population ( Kletzer 1998 ). Job loss is a discrete event, while unemployment is a state, with a great deal of heterogeneity with respect to instigation and duration. Job displacement is more of an exogenous shock than unemployment, or job loss more broadly defined, allowing for better estimates of the consequences of socioeconomic mobility. I spend considerably more time on job displacement than on unemployment, per se, in this review.

This review proceeds as follows. I begin with a description of trends and risk factors associated with job loss, and then consider some methodological and interpretative issues in estimating displacement effects. I then review the economic impact of job loss. Thereafter I thoroughly attend to the wider impact of worker displacement. I conclude with several directions for future research. I focus my review on job loss in the United States.

Trends in and Risk Factors Associated with Job Loss

Widespread job insecurity, waves of job loss, and associated periods of unemployment and income loss have characterized the last several decades in the U.S. ( Farber 2010 ; Farley 1996 ; Kalleberg 2000 , 2009 ; Kletzer 1998 ; Wetzel 1995 ). Most Americans believe that employment stability has declined ( Hollister 2011 ), and job displacement is now considered a common feature of the U.S. labor market. The macroeconomic trends commonly associated with worker displacement include: technological change; foreign trade and the shift to production offshore to take advantage of low-wage foreign workers; immigration; firms’ greater use of outside suppliers, subcontractors, and partners, and the paring down of the activities of the firm; the shift in U.S. consumption from manufactured goods to services; poor firm management; weakened labor unions; and regional and national economic downturn.

High levels of workers displacement marked the last four recessions in the U.S. The early 1980s recession convinced firms to utilize effective new equipment, shift production to modern plants, and lay off thousands of workers ( Farley 1996 ). Wetzel (1995) wrote: “Industrial firms that had prided themselves on lifetime paternalistic commitments to their production workers – largely men with average or below-average educational attainment – slashed employment … The abrupt contraction struck at the heart of the middle class by drastically impacting mature family men with strong labor force attachment, good work histories, and long job tenure” (p. 101). The economic recovery of the 1980s was marked by large employment gains; nevertheless, unemployment persisted at a relatively high rate and newly created jobs were in general of a lower quality than jobs from which workers had lost. The early 1990s recession was marked by the creation of flat organization and elimination of middle management positions. High levels, particularly during economic recessions, of job loss and unemployment characterize the U.S. labor market since 1990. In the 1990s through early 2000s, worker layoffs, once regarded as organizational failure, were increasingly utilized as a labor allocative process available to firms in order to preserve shareholder value. Ensuing waves of downsizing, reorganization, mergers and takeovers rewarded some individuals with great prosperity while others were threatened with displacement, unemployment, and downward mobility ( Baumol et al. 2003 ). The recessionary period from the end of 2007 to mid-2009, the “Great Recession,” was deeper and more extensive than any other since the Great Depression of the 1930s ( Hout, Levanon, and Cumberworth 2011 ). The U.S. unemployment rate hovered around 9 to 10 percent in 2009–2011, the highest rate since the early 1980s recession and roughly twice the pre-crisis rate. The proportion of families with an unemployed member was roughly 12 percent in 2009, up from about 6 percent in 2007. The large increase in long-term unemployment in this most recent recession is suggestive of longer-term structural labor market changes ( Katz 2010 ).

While macroeconomic and firm-level factors influence the incidence of job loss and unemployment, a number of individual-level characteristics also govern the risk of displacement. Men and blacks and Hispanics had a higher probability of being displaced than women and whites in the 1980s; family background disadvantage, blue-collar and manufacturing work, low occupational status, low job tenure, and low levels of education likewise heightened the risk of job loss over this period (Brand 2005; Farber 2005 ). Job loss rates increased for women and for whites in the 1990s, as well as for college-educated and high tenure workers (Couch 1998; Farber 1993b , 1997b , 2005 ). While educated workers maintain a lower risk of displacement, the increased rates have nevertheless aroused public concern that the structure of job loss qualitatively changed over recent decades, increasing vulnerability to job loss across the population ( Fallick 1996 ; Farber 1993a , 1993b , 2010 ).

Estimating Effects of Job Loss

Abrupt changes in socioeconomic conditions provide a sort of “natural experiment” offering a stronger basis for inference than the usual practice of examining the covariation of outcomes with socioeconomic status that may arise from a variety of sources over an indeterminate period of time. The study of job displacement, thus, provides a unique opportunity to assess within individual changes in socioeconomic conditions that are relatively exogenous to individual characteristics. Indeed, scholars often explicitly describe the study of displacement as a purer way to estimate the effects of socioeconomic shocks ( Stevens 2014 ). Nevertheless, the study of displacement does not fully mitigate selection issues, as job loss is clearly conditioned by factors that are also associated with levels of subsequent outcomes. A primary concern in attempting to identify effects of job loss is the potential presence of unobservable characteristics that affect both worker displacement and subsequent outcomes. That is, we are left with the fundamental question of whether workers who were displaced from jobs have outcomes that are different than they otherwise would have been had they not been displaced. If employers make targeted decisions regarding whom to displace, there is a possibility that it is relatively less productive workers (e.g. lower levels of motivation, commitment, and ability), workers with physical or mental health issues, and socially inept workers who both are more likely to lose jobs and have worse economic and social outcomes. Scholars, however, have found few differences across several leading estimators of causal effects (including regression, matching, difference-in-difference and fixed effects models), suggesting a degree of robustness regarding the nature of the observed associations between displacement and life outcomes in the face of various technical assumptions and model specifications ( Brand 2006 ; Coelli 2011 ; Stevens and Schaller 2009).

Yet another strategy to deal with possible selection bias is to adopt a quasi-experimental strategy that tracks the well-being of workers following a plant closure. When an entire organization closes, it is unlikely that a workers’ specific characteristics are responsible for the displacement. Thus if the results for plant closings and more individualized lay-offs are similar, we have a firmer basis for claiming the validity of the effect estimates for the full population of displaced workers. Likewise, job losses occurring during recessionary periods, in which large numbers of individuals lose jobs, may provide better causal estimates of job loss ( Stevens 2014 ). A few caveats as to inferences we can make from mass layoff studies are nevertheless in order. While such studies make strong claims for having eliminated the influence of selection, plant closure studies are typically limited to specific populations (often blue-collar workers) in specific geographic areas, restricting generalizability to the U.S. workforce as a whole. That is, studies of plant closures ostensibly sacrifice external for internal validity. Some closure studies are also lacking a control group of non-displaced workers. Additionally, plant closure studies may still be subject to selection bias, as more qualified and adaptive employees may leave the plant upon word of the impending closure. The same can be said for studies of workers displaced during recessions.

Job losses due to layoffs and those due to plant closings, and job loss occurring in different economic contexts, may also produce different effects because they are potentially different treatment conditions. In the case of layoffs and job loss during economic expansions, the greater likelihood for discretionary dismissal of employees can call into question competency and character and act as a signal of below-average productivity, to the displaced workers, as well as to their families and communities, and in the labor market. If potential employers interpret layoffs as indications of ineptitude, hiring will be discouraged. The resulting difficulty of laid-off workers to secure suitable reemployment may result in greater long-term economic losses. Economic distress, alongside attribution of job loss to one’s own shortcomings, and the stigma of a layoff and resulting strained relations with colleagues, friends, and/or family members, can in turn lead laid off workers to lower self-esteem, anxiety, and depressive symptoms (Leana and Feldman 1992; Miller and Hoppe 1994 ). Individually laid of workers may also lack similarly strained workers to offer a network of support ( Miller and Hoppe 1994 ; Brand, Levy, and Gallo 2008 ). These circumstances contrast with that of job loss due to plant closings and loss occurring in economic recessions, in which clearly external influences, including the health of the macro-economy and firms’ decisions to restructure or relocate business units, provokes separation. Because such factors are clearly beyond the control of individual employees, plant closings do not involve a negative signal that raises transaction costs for displaced workers. Indeed workers displaced due to business closings are victims of an event that could befall anyone, and seldom perceive themselves as responsible for the job loss. Thus, such workers may endure lower economic and social-psychological burdens. 1

Economic Effects of Job Loss

Increasing job insecurity and displacement has motivated a large body of research on effects, beginning with economic losses. The average displaced worker experiences a long period of unemployment ( Brand 2004 ; Chan and Stevens 1999; Fallick 1996 ; Farber 2003, 2005 ; Kletzer 1998 ; Podgursky and Swaim 1987 ; Ruhm 1991 ), but the duration has a high degree of worker variance ( Seitchik 1991 ). Unemployment among displaced workers generally lasts longer during recessions than expansions ( Farber 1993a ; Kletzer 1991 , 1998 ). The impact of job loss on careers is considerable even when workers do not experience long-term unemployment. Displaced workers suffer substantial earnings losses, which are generally more persistent than unemployment effects ( Brand 2004 ; Cha and Morgan 2010 ; Chan and Stevens 1999, 2001 ; Couch 1998; Couch, Jolly, and Placzek 2011 ; Couch and Placzek 2010 ; Davis and von Wachter 2012 ; Fallick 1996 ; Farber 2003, 2005 ; Jacobson, LaLonde, and Sullivan 1993 ; Kletzer 1998 ; Podgursky and Swaim 1987 ; Ruhm 1991 ; Seitchik 1991 ; Stevens 2014 ; von Wachter 2010 ). Couch and Placzek (2010) report an immediate 33 percent earnings loss and as much as a 15 percent loss six years following job separation. The cumulative lifetime earning loss is estimated to be roughly 20 percent, with wage scarring observed as long as 20 years post-displacement ( Brand and von Wachter 2013 ; Davis and von Wachter 2012 ; von Wachter 2010 ; von Wachter, Song, and Manchester 2009). Reemployed displaced workers are more likely than their non-displaced counterparts to be employed part-time, and this likelihood has increased over time, particularly during recessions ( Farber 1993b , 2003, 2005 ). Displaced workers may also find, when reemployed, that their jobs are of lower quality in terms of job authority, autonomy, and employer-offered benefits in comparison to both the jobs they lost and those held by their non-displaced counterparts ( Brand 2004 , 2006 ; Podgursky and Swaim 1987 ). Workers also withstand greater job instability for at least a decade following a displacement event ( von Wachter 2010 ).

While economic losses occur for displaced workers across demographic categories, across industries and throughout the skill distribution ( von Wachter 2010 ), there is nevertheless effect variation by worker characteristics. Displaced workers’ losses reflect both industry-specific decline and the loss of firm- and industry-specific skills ( Kalleberg 2000 ). Older workers with higher pre-displacement tenure, those who change industries, and those who experience multiple job losses thus experience greater earnings losses ( Carrington and Zaman 1994 ; Couch, Jolly, and Placzek 2009; Fallick 1996 ; Jacobson, LaLonde, & Sullivan 1993 ; Stevens 1997; von Wachter 2010 ). As greater skill transferability is expected for educated workers, employment, earnings, and job quality reductions are typically more pronounced for less-educated workers ( Farber 1997 , 2003, 2005 ; Kletzer 1991 , 1998 ; Podgursky and Swaim 1987 ; Seitchik 1991 ). Still, as the incidence of displacement for more educated workers has increased, the transition difficulties for such workers have increased as well.

While displaced workers’ economic costs are substantial during both economic recessions and expansions, losses are cyclical ( Couch, Jolly, and Placzek 2011 ; Davis and von Wachter 2012 ; Fallick 1996 ; Farber 1993a , 1997a , 2005 ; Jacobson, LaLonde, and Sullivan 1993 ; Kletzer 1998 ; von Wachter 2010 ). As few firms hire during economic contractions, displaced workers seeking reemployment are in a poorer negotiating position than during economic expansions. Davis and von Wachter (2012) find that men lose an average of 1.4 years of pre-displacement earnings if displaced in mass-layoff events that occur when the national unemployment rate is below 6 percent, and lose 2.8 years of pre-displacement earnings if displaced when the unemployment rate exceeds 8 percent. Similarly, Couch, Jolly, and Placzek (2011) find that long-term earnings losses for displaced workers during a recessionary period are about 2 to 4 times larger than for those observed during a period of economic expansion.

There is some debate over variation in economic losses by the specific form of job loss. Recent work (Kashinsky 2002; Stevens 1997; von Wachter 2010 ) has questioned the findings of an influential study by Gibbons and Katz (1991) that suggested that layoffs are associated with greater economic losses than are plant closings. Gibbons and Katz (1991) argued that in the case of a layoff, the discretionary dismissal of employees acts as a signal of below average productivity, stigmatizing laid-off workers, resulting in large employment and earnings losses. On the contrary, a plant closing, in which all workers are terminated without discretion, does not carry a comparable performance signal, rendering earnings penalties less severe. Extending this argument to differences in earnings losses by economic context, we might expect countercyclical earnings losses, as the stigma associated with displacement during an economic contraction should be less than that during an economic expansion. However, as I note above, such losses are cyclical. In support of the evidence for cyclicality, we should expect larger earnings losses from job loss due to plant closings as such closures may indicate weak local or macro economic conditions. Krashinsky (2002) argues that the Gibbons and Katz (1991) result is driven by the fact that small plants are more likely to close, and that layoffs that occur from larger, higher-wage employment establishments result in larger earnings losses. 2

Several mechanisms help explicate the large economic losses of displaced workers. Earnings and job quality declines are likely to increase with unemployment duration. Yet it is unclear whether this association is the result of length of unemployment itself, and possible stigma effects, or because those workers facing the greatest challenges in the labor market take longer to find a new job ( von Wachter 2010 ). Workers are also disadvantaged in the market if industries in which they were previously employed shift their operations elsewhere or permanently reduce their employment levels. Relatedly, lower job quality upon reemployment is a function of the loss of a high quality match between the worker and the job ( Fallick 1996 ). While a worker generally only leaves a job voluntarily when he or she believes there are relative gains in career attainment to be made, displaced workers likely feel an urgency to find a new job and are in a poor position to perform a quality job screening ( Newman 1988 ).

Non-Economic Effects of Job Loss

Job loss is a negative, often unpredictable event that entails a sequence of stressful experiences, from job loss notification, anticipation, dismissal, and often unemployment, to (in most cases) job search, re-training and eventual reemployment, often at jobs with lower wages and job quality. Yet the impact of job loss and unemployment is not limited to economic decline; it is also associated with considerable, long-term non-economic consequences for displaced workers, as well as for their families and communities. Displaced workers face psychological and physical distress, personal reassessment in relation to individual values and societal pressures, and new patterns of interaction with family and peers. Much of the work on the non-economic consequences of job loss is consistent with a large literature demonstrating a strong correlation between indicators of socioeconomic status and individual life chances and well-being. However, as displacement is a relatively exogenous labor market shock, its study enables a stronger causal link between socioeconomic circumstances and life outcomes. In this section, I begin reviewing individual worker effects on psychological and physical well-being, and then consider the consequences for families and communities.

Job Loss and Psychological Well-Being

A large literature on mental health has focused on the impact of stressful life events, such as unemployment and job loss. Job loss disrupts more than just income flow; it disrupts individuals’ status, time structure, demonstration of competence and skill, and structure of relations. It carries societal stigma, creating a sense of anxiety, insecurity, and shame ( Newman 1988 ). The loss of a job presents a source of acute stress associated with the immediate disruption to a major social role, as well as chronic stress resulting from continuing economic and social and psychological strain (House 1987; Pearlin et al. 1981 ). Research suggests that displaced workers report higher levels of depressive symptoms, somatization, and anxiety and the loss of psychosocial assets including self-acceptance, self-confidence, self-esteem, morale, life satisfaction, goal and meaning in life, social support, and sense of control ( Brand, Levy, and Gallo 2008 ; Burgard, Brand and House 2007 ; Catalano et al. 2011 ; Dooley, Fielding and Levi 1996 ; Darity and Goldsmith 1996 ; Dooley, Prause, and Ham-Rowbottom 2000 ): Gallo et al. 2000 ; Gallo et al. 2006a ; Hamilton et al. 1990 ; Jahoda 1981 , 1982 ; Jahoda, Lazarsfeld, and Zeisel 1933[1971] ; Kasl and Jones 2000; Kessler, Turner, and House 1988 , 1989 ; Leana and Feldman 1992 ; McKee-Ryan et al. 2005 ; Miller and Hoppe 1994 ; Paul and Moser 2009 ; Pearlin et al. 1981 ; Turner 1995 ; Warr and Jackson 1985 ). 3 The increase in reported symptoms of depression and anxiety among displaced workers compared to non-displaced workers is roughly 15 to 30 percent ( Burgard, Brand, and House 2007 ; Catalano et al. 2011 ; Paul and Moser 2009 ). Leading explanations for why job loss and unemployment negatively impact well-being include lowered self-esteem, sense of purpose, and control; heightened apathy, idleness, isolation, and the breakdown of social personality structure; and a loss of the positive derivatives of participating in a work environment, such as skill use, time structure, economic security, interpersonal socialization, and valued societal position ( Darity and Goldsmith 1996 ; Jahoda 1982 ; Jahoda, Lazarsfeld, and Zeisel 1933[1971] ; McKee-Ryan et al. 2005 ). 4

Although displacement is more of an exogenous shock than other types of job mobility, the possibility of omitted variable bias nevertheless threatens the validity of results associating job loss to subsequent outcomes. Of particular concern in the study of psychological well-being, workers with psychological distress and lacking self-confidence and morale may be those workers most likely to be displaced from jobs. Studies have used various approaches to address this selection problem, most often attempting to control for a range of factors that impact the likelihood of job loss and subsequent well-being. Studies continue to find an association, although often reduced in magnitude. For example, Burgard, Brand, and House (2007) adjust for numerous social background characteristics, including baseline psychological health, and find a significant effect of job loss on depressive symptoms. Moreover, using meta-analytic techniques drawing on over 100 empirical studies, McKee-Ryan et al. (2005) find consistency in results across multiple kinds of studies and hundred of data points suggesting a relationship between job loss and worker well-being. Studies based on plant closures, thought to be less prone to issues of selection, continue to find an increased risk of mental distress among the displaced ( Hamilton et al. 1990 ). 5

As is true with the economic consequences of job loss, the effects of job loss on psychological well-being vary by a range of factors, including demographic characteristics, socio-emotional skills and social support, and the economic context. While more disadvantaged workers may be more vulnerable to financial shocks ( Hamilton et al. 1990 ), such economic adversity is a comparatively normative experience; by contrast, job displacement and socioeconomic decline may instigate an acute sense of deprivation among more advantaged families whose peers tend to be likewise advantaged and for whom displacement is a considerable shock ( Brand and Simon Thomas 2014 ). That is, judgments of disruptive events depend on the experience of similar situations in the past, and higher levels of past adversity may lessen the impact of current adversity ( Clark, Georgellis, and Sanfey 2001 ; Dooley, Prause, and Ham-Rowbottom 2000 ). If the difficulties posed by job loss and unemployment are primarily financial, then reemployment has the potential to remove much of the stress, particularly if the income is comparable to what the worker had been earning. If job loss profoundly alters one’s self-concept and place in society, however, the extent to which reemployment will reverse these effects is unclear. While significant effects of reemployment have been documented among blue-collar workers ( Kessler, Turner, and House 1989 ; Warr and Jackson 1985 ), professionals and upper-level, white-collar workers do not seem to recover as readily. In contrast to the literature on the economic effects, attention has also been paid to variation in the effects of job loss by socio-emotional skills and social support. For example, worker response to displacement varies by individual work-role centrality, or employment commitment, where workers who place more importance on the work role to their sense of self suffer more from job loss. Individuals also vary in their coping resources, i.e. the personal, financial, and social resources they draw on to cope with job loss, and social support, such as social integration, availability of friends, relatives, and co-workers, and marital status and spousal support ( Darity and Goldsmith 1996 ; Leana and Feldman 1988 ; Pearlin et al. 1981 ).

The experience of job loss and unemployment may also vary by the economic context. Displacement that occurs during recessions, in which many workers are laid off, is associated with greater economic losses than displacement that occurs during economic expansions ( Couch, Jolly, and Placzek 2011 ; Davis and von Wachter 2011; Fallick 1996 ; von Wachter 2010 ). However, contexts of widespread unemployment lessen the internalization of blame and social stigma associated with job loss ( Brand, Levy, and Gallo 2008 ; Charles and Stephens 2004 ; Clark 2003 , 2010 ; Miller and Hoppe 1994 ). That is, displaced workers may benefit from a “social norm effect”: as aggregate unemployment increases, one’s own unemployment represents a smaller deviation from the social norm ( Clark 2010 ), and thus displacement effects on social-psychological well-being may be less in contexts of mass layoffs. Turner (1995) shows a three-way interaction, indicating that unemployment effects on psychological well-being are strongest in low unemployment areas, particularly among individuals with a college-level education. While economic burden is greater among workers with lower socioeconomic status and those displaced in higher unemployment contexts, personal attribution is greater among higher status victims of job loss and those displaced in low unemployment contexts ( Kessler, Turner, and House 1988 ; Pearlin et al. 1981 ; Turner 1995 ). These interactions highlight that results are sensitive to the population, geographic location, and time period under study.

Scholars have proposed a number of mechanisms to explain the relationship between job loss and psychological well-being. First, economic deprivation and downward socioeconomic mobility provide leading explanations for the relationship between job loss and psychological distress, as indicated by unemployment duration ( Clark, Georgellis, and Sanfey 2001 ; McKee-Ryan et al. 2005 ) and income loss ( Gallo et al. 2006a ; Kasl and Jones 2000; Kessler, Turner, and House 1988 ; Warr and Jackson 1985 ). Second, job loss and unemployment can dampen self-esteem, aspirations, and time structure; incite resignation, apathy, uncertainty, and stigmatization; and frustrate one’s social identity by replacing a socially approved role with one of markedly lower prestige ( Jahoda 1982 ; Jahoda, Lazarsfeld, and Zeisel 1933[1971] ). Scholars either include these measures within the set of dependent variables of interest, or treat the psychosocial indicators as mediators linking job loss to depressive symptoms. Third, family and social strain help to explain the relationship ( Darity and Goldsmith 1996 ). Fourth, additional stressful life events that occur subsequent to job loss, such as additional job losses, divorce, health shocks, and migration explain some of the effects. Although scholars routinely implicate these mechanisms, few studies rigorously empirically test these mediating influences ( Catalano et al. 2011 ).

Job Loss and Physical Well-Being

Job loss has been linked to both short and long-term declines in physical health, including worse self-reported health, physical disability, cardiovascular disease, a greater number of reported medical conditions, increase in hospitalization, higher use of medical services, higher use of disability benefits, an increase in self-destructive behaviors and suicide, and mortality ( Burgard, Brand, and House 2007 ; Catalano et al. 2011 ; Dooley, Fielding, and Levi 1996 ; Ferrie et al. 1998 ; Gallo et al. 2000 ; Gallo et al. 2004 ; Gallo et al. 2006b ; Gallo et al. 2009 ; Kasl and Jones 2000; Kessler, Turner, and House 1988 ; McKee-Ryan et al. 2005 ; Strully 2009 ; Turner 1995 ). For example, Gallo et al. (2004 , 2006b) found that job loss doubled the risk of subsequent myocardial infarction and stroke among older workers. Sullivan and von Wachter (2009) and von Wachter (2010) found a 50 to 100 percent increase in mortality the year following displacement and a 10 to 15 percent increase in mortality rates for the next 20 years.

Despite a large literature suggesting an association between job loss and ill health, the causal relationship remains contested due to concerns over selection bias. The fundamental concern is whether job loss leads to ill health, or whether at least some or all of the observed association occurs because those individuals who have poor health are more likely to lose jobs. Even with a rich set of pre-displacement covariates, the question remains as to whether models fully adjust for pre-displacement health, personality and psychosocial characteristics, lifestyle, and labor market experiences that may lead to both job loss and ill health. Burgard, Brand, and House (2007) continue to find a significant association between involuntary job loss and overall self-rated health even after adjustment for social background characteristics and baseline health. More nuanced analyses of specific reasons for job loss and the timing of job loss relative to health shocks reveal that those who lose their jobs for health-related reasons have, not surprisingly, the most precipitous declines in health. Effects of job losses for non-health reasons on self-rated poor health are relatively small ( Burgard, Brand, and House 2007 ). Studies of plant closures also show that workers’ health declines following job loss (Arnetz et al. 1991; Beal and Nethercott 1987; Gore 1978; Iversen, Sabroe, and Damsgaard 1989; Kasl and Cobb 1970; Kessler, House, and Turner 1987; Strully 2009 ).

Variation in displacement effects and the mechanisms linking job loss to physical health are similar to psychological effects, including economic loss ( Sullivan and von Wachter 2009 ; von Wachter 2010 ) and erosion of psychosocial assets and social support ( Eliason and Storrie 2009 ) and subsequent adverse life events. Yet a few comments specific to the mediating effects on physical health are merited. The effect of job loss and unemployment on depressive symptoms may manifest itself in physiological outcomes, thus the impact of job loss on psychological well-being can help explain the effect on physical health. In addition, health behaviors, such as greater alcohol and drug use, unhealthy food consumption and less exercise, and sleep quality, may partially mediate the association. On the other hand, for some individuals, the increase in discretionary time due to unemployment may be used to pursue health-promoting behaviors, such as physical activity, that might precipitate weight loss or encourage alcohol temperance ( Catalano et al. 2011 ). Another clear mechanism is the loss of employer-offered health insurance and reduced access to medical care.

Job Loss and Families