- Open access

- Published: 28 September 2018

Posttraumatic stress disorder: from diagnosis to prevention

- Xue-Rong Miao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0665-8271 1 ,

- Qian-Bo Chen 1 ,

- Kai Wei 1 ,

- Kun-Ming Tao 1 &

- Zhi-Jie Lu 1

Military Medical Research volume 5 , Article number: 32 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

54k Accesses

43 Citations

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a chronic impairment disorder that occurs after exposure to traumatic events. This disorder can result in a disturbance to individual and family functioning, causing significant medical, financial, and social problems. This study is a selective review of literature aiming to provide a general outlook of the current understanding of PTSD. There are several diagnostic guidelines for PTSD, with the most recent editions of the DSM-5 and ICD-11 being best accepted. Generally, PTSD is diagnosed according to several clusters of symptoms occurring after exposure to extreme stressors. Its pathogenesis is multifactorial, including the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, immune response, or even genetic discrepancy. The morphological alternation of subcortical brain structures may also correlate with PTSD symptoms. Prevention and treatment methods for PTSD vary from psychological interventions to pharmacological medications. Overall, the findings of pertinent studies are difficult to generalize because of heterogeneous patient groups, different traumatic events, diagnostic criteria, and study designs. Future investigations are needed to determine which guideline or inspection method is the best for early diagnosis and which strategies might prevent the development of PTSD.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a recognized clinical phenomenon that often occurs as a result of exposure to severe stressors, such as combat, natural disaster, or other events [ 1 ]. The diagnosis of PTSD was first introduced in the 3rd edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association) in 1980 [ 2 ].

PTSD is a potentially chronic impairing disorder that is characterized by re-experience and avoidance symptoms as well as negative alternations in cognition and arousal. This disease first raised public concerns during and after the military operations of the United States in Afghanistan and Iraq, and to date, a large number of research studies report progress in this field. However, both the underlying mechanism and specific treatment for the disease remain unclear. Considering the significant medical, social and financial problems, PTSD represents both to nations and to individuals, all persons caring for patients suffering from this disease or under traumatic exposure should know about the risks of PTSD.

The aim of this review article is to present the current understanding of PTSD related to military injury to foster interdisciplinary dialog. This article is a selective review of pertinent literature retrieved by a search in PubMed, using the following keywords: “PTSD[Mesh] AND military personnel”. The search yielded 3000 publications. The ones cited here are those that, in the authors’ view, make a substantial contribution to the interdisciplinary understanding of PTSD.

Definition and differential diagnosis

Posttraumatic stress disorder is a prevalent and typically debilitating psychiatric syndrome with a significant functional disturbance in various domains. Both the manifestation and etiology of it are complex, which has caused difficulty in defining and diagnosing the condition. The 3rd edition of the DSM introduced the diagnosis of PTSD with 17 symptoms divided into three clusters in 1980. After several decades of research, this diagnosis was refined and improved several times. In the most recent version of the DSM-5 [ 3 ], PTSD is classified into 20 symptoms within four clusters: intrusion, active avoidance, negative alterations in cognitions and mood as well as marked alterations in arousal and reactivity. The diagnosis requirement can be summarized as an exposure to a stressor that is accompanied by at least one intrusion symptom, one avoidance symptom, two negative alterations in cognitions and mood symptoms, and two arousal and reactivity turbulence symptoms, persisting for at least one month, with functional impairment. Interestingly, in the DSM-5, PTSD has been moved from the anxiety disorder group to a new category of ‘trauma- and stressor-related disorders’, which reflects the cognizance alternation of PTSD. In contrast to the DSM versions, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD) has proposed a substantially different approach to diagnosing PTSD in the most recent ICD-11 version [ 4 ], which simplified the symptoms into six under three clusters, including constant re-experiencing of the traumatic event, avoidance of traumatic reminders and a sense of threat. The diagnosis requires at least one symptom from each cluster which persists for several weeks after exposure to extreme stressors. Both diagnostic guidelines emphasize the exposure to traumatic events and time of duration, which differentiate PTSD from some diseases with similar symptoms, including adjustment disorder, anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and personality disorder. Patients with the major depressive disorder (MDD) may or may not have experienced traumatic events, but generally do not have the invasive symptoms or other typical symptoms that PTSD presents. In terms of traumatic brain injury (TBI), neurocognitive responses such as persistent disorientation and confusion are more specific symptoms. It is worth mentioning that some dissociative reactions in PTSD (e.g., flashback symptoms) should be recognized separately from the delusions, hallucinations, and other perceptual impairments that appear in psychotic disorders since they are based on actual experiences. The ICD-11 also recognizes a sibling disorder, complex PTSD (CPTSD), composed of symptoms including dysregulation, negative self-concept, and difficulties in relationships based on the diagnosis of PTSD. The core CPTSD symptom is PTSD with disturbances in self-organization (DSO).

In consideration of the practical applicability of the PTSD diagnosis, Brewin et al. conducted a study to investigate the requirement differences, prevalence, comorbidity, and validity of the DSM-5 and ICD-11 for PTSD criteria. According to their study, diagnostic standards for symptoms of re-experiencing are higher in the ICD-11 than the DSM, whereas the standards for avoidance are less strict in the ICD-11 than in the DSM-IV [ 5 ]. It seems that in adult subjects, the prevalence of PTSD using the ICD-11 is considerably lower compared to the DSM-5. Notably, evidence suggested that patients identified with the ICD-11 and DSM-5 were quite different with only partially overlapping cases; this means each diagnostic system appears to find cases that would not be diagnosed using the other. In consideration of comorbidity, research comparing these two criteria show diverse outcomes, as well as equal severity and quality of life. In terms of children, only very preliminary evidence exists suggesting no significant difference between the two. Notably, the diagnosis of young children (age ≤ 6 years) depends more on the situation in consideration of their physical and psychological development according to the DSM-5.

Despite numerous investigations and multiple revisions of the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, it remains unclear which type and what extent of stress are capable of inducing PTSD. Fear responses, especially those related to combat injury, are considered to be sufficient enough to trigger symptoms of PTSD. However, a number of other types of stressors were found to correlate with PTSD, including shame and guilt, which represent moral injury resulting from transgressions during a war in military personnel with deeply held moral and ethical beliefs. In addition, military spouses and children may be as vulnerable to moral injury as military service members [ 6 ]. A research study on Canadian Armed Forces personnel showed that exposure to moral injury during deployments is common among military personnel and represents an independent risk factor for past-year PTSD and MDD [ 7 ]. Unfortunately, it seems that pre- and post-deployment mental health education was insufficient to moderate the relationship between exposure to moral injury and adverse mental health outcomes.

In general, a large number of studies are focusing on the definition and diagnostic criteria of PTSD and provide considerable indicators for understanding and verifying the disease. However, some possible limitations or discrepancies continue to exist in current research studies. One is that although the diagnostic criteria for a thorough examination of the symptoms were explicit and accessible, the formal diagnosis of PTSD using structured clinical interviews was relatively rare. In contrast, self-rating scales, such as the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) [ 8 ] and the Impact of Events Scale (IES) [ 9 ], were used frequently. It is also noteworthy that focusing on PTSD explicitly could be a limitation as well. The complexity of traumatic experiences and the responses to them urge comprehensive investigations covering all aspects of physical and psychological maladaptive changes.

Prevalence and importance

Posttraumatic stress disorder generally results in poor individual-level outcomes, including co-occurring disorders such as depression and substance use, and physical health problems. According to the DSM-5 reporting, more than 80% of PTSD patients share one or more comorbidities; for instance, the morbidity of PTSD with concurrent mild TBI is 48% [ 8 ]. Moreover, cognitive impairment has been identified frequently in PTSD. The reported incidence rate for PTSD ranges from 5.4 to 16.8% in military service members and veterans [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ], which is almost double those in the general population. The estimated prevalence of PTSD varies depending on the group of patients studied, the traumatic events occurred, and the measurement method used (Table 1 ). However, it still reflects the profound effect of this mental disease, especially with the rise in global terrorism and military conflict in recent years. While PTSD can arise at any life stage in any population, most research in recent decades has focused on returned veterans; this means most knowledge regarding PTSD has come from the military population. Meanwhile, the impact of this disease on children has received scant attention.

The discrepancy of PTSD prevalence in males and females is controversial. In a large study of OEF/OIF veterans, the prevalence of PTSD in males and females was similar, although statistically more prevalent in men versus women (13% vs. 11%) [ 15 ]. Another study on the Navy and Marine Corps showed a slightly higher incidence for PTSD in the women compared to men (6.6% vs. 5.3%) [ 12 ]. However, the importance of combat exposure is unclear. Despite a lower level of combat exposure than male military personnel, females generally have considerably higher rates of military sexual trauma, which is significantly associated with the development of PTSD [ 16 ].

It is reported that 44–72% of veterans suffer high levels of stress after returning to civilian life. Many returned veterans with PTSD show emotion regulation problems, including emotion identification, expression troubles and self-control issues. Nevertheless, a meta-analytic investigation of 34 studies consistently found that the severity of PTSD symptoms was significantly associated with anger, especially in military samples [ 17 ]. Not surprisingly, high levels of PTSD and emotional regulation troubles frequently lead to poor family functioning or even domestic violence in veterans. According to some reports, parenting difficulties in veteran families were associated with three PTSD symptom clusters. Evans et al. [ 18 ] conducted a survey to evaluate the impact of PTSD symptom clusters on family functioning. According to their analysis, avoidance symptoms directly affected family functioning, whereas hyperarousal symptoms had an indirect association with family functioning. Re-experience symptoms were not found to impact family functioning. Notably, recent epidemiologic studies using data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) reported that veterans with PTSD were linked to suicide ideations and behaviors [ 19 ] (e.g., non-suicidal self-injury, NSSI), in which depression as well as other mood disruptions, often serve as mediating factors.

Previously, there was a controversial attitude toward the vulnerability of young children to PTSD. However, growing evidence suggests that severe and persistent trauma could result in stress responses worse than expected as well as other mental and physical sequelae in child development. The most prevalent traumatic exposures for young children above the age of 1 year were interpersonal trauma, mostly related to or derived from their caregivers, including witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV) and maltreatment [ 20 ]. Unfortunately, because of the crucial role that caregivers play in early child development, these types of traumatic events are especially harmful and have been associated with developmental maladaptation in early childhood. Maladaptation commonly represents a departure from normal development and has even been linked to more severe effects and psychopathology. In addition, the presence of psychopathology may interfere with the developmental competence of young children. Research studies have also broadened the investigation to sequelae of PTSD on family relationships. It is proposed that the children of parents with symptoms of PTSD are easily deregulated or distressed and appear to face more difficulties in their psychosocial development in later times compared to children of parents without. Meanwhile, PTSD veterans described both emotional (e.g., hurt, confusion, frustration, fear) and behavioral (e.g., withdrawal, mimicking parents’ behavior) disruption in their children [ 21 ]. Despite the increasing emphasis on the effects of PTSD on young children, only a limited number of studies examined the dominant factors that influence responses to early trauma exposures, and only a few prospective research studies have observed the internal relations between early PTSD and developmental competence. Moreover, whether exposure to both trauma types in early life is associated with more severe PTSD symptoms than exposure to one type remains an outstanding question.

Molecular mechanism and predictive factors

The mechanisms leading to posttraumatic stress disorder have not yet been fully elucidated. Recent literature suggests that both the neuroendocrine and immune systems are involved in the formulation and development of PTSD [ 22 , 23 ]. After traumatic exposures, the stress response pathways of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic nervous system are activated and lead to the abnormal release of glucocorticoids (GC) and catecholamines. GCs have downstream effects on immunosuppression, metabolism enhancement, and negative feedback inhibition of the HPA axis by binding to the GC receptor (GR), thus connecting the neuroendocrine modulation with immune disturbance and inflammatory response. A recent meta-analysis of 20 studies found increased plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a), interleukin-1beta (IL-1b), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in individuals with PTSD compared to healthy controls [ 24 ]. In addition, some other studies speculate that there is a prospective association of C-reactive protein (CRP) and mitogen with the development of PTSD [ 25 ]. These findings suggest that neuroendocrine and inflammatory changes, rather than being a consequence of PTSD, may in fact act as a biological basis and preexisting vulnerability for developing PTSD after trauma. In addition, it is reported that elevated levels of terminally differentiated T cells and an altered Th1/Th2 balance may also predispose an individual to PTSD.

Evidence indicates that the development of PTSD is also affected by genetic factors. Research has found that genetic and epigenetic factors account for up to 70% of the individual differences in PTSD development, with PTSD heritability estimated at 30% [ 26 ]. While aiming to integrate genetic studies for PTSD and build a PTSD gene database, Zhang et al. [ 27 ] summarized the landscape and new perspective of PTSD genetic studies and increased the overall candidate genes for future investigations. Generally, the polymorphisms moderating HPA-axis reactivity and catecholamines have been extensively studied, such as FKBP5 and catechol-O-methyl-transferase (COMT). Other potential candidates for PTSD such as AKT, a critical mediator of growth factor-induced neuronal survival, were also explored. Genetic research has also made progress in other fields. For example, researchers have found that DNA methylation in multiple genes is highly correlated with PTSD development. Additional studies have found that stress exposure may even affect gene expression in offspring by epigenetic mechanisms, thus causing lasting risks. However, some existing problems in the current research of this field should be noted. In PTSD genetic studies, variations in population or gender difference, a wide range of traumatic events and diversity of diagnostic criteria all may attribute to inconsistency, thus leading to a low replication rate among similar studies. Furthermore, PTSD genes may overlap with other mental disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. All of these factors indicate an urgent need for a large-scale genome-wide study of PTSD and its underlying epidemiologic mechanisms.

It is generally acknowledged that some mental diseases, such as major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, are associated with massive subcortical volume change. Recently, numerous studies have examined the relationship between the morphology changes of subcortical structures and PTSD. One corrected analysis revealed that patients with PTSD show a pattern of lower white matter integrity in their brains [ 28 ]. Prior studies typically found that a reduced volume of the hippocampus, amygdala, rostral ventromedial prefrontal cortex (rvPFC), dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), and the caudate nucleus may have a relationship with PTSD patients. Logue et al. [ 29 ] conducted a large neuroimaging study of PTSD that compared eight subcortical structure volumes (nucleus accumbens, amygdala, caudate, hippocampus, pallidum, putamen, thalamus, and lateral ventricle) between PTSD patients and controls. They found that smaller hippocampi were particularly associated with PTSD, while smaller amygdalae did not show a significant correlation. Overall, rigorous and longitudinal research using new technologies, such as magnetoencephalography, functional MRI, and susceptibility-weighted imaging, are needed for further investigation and identification of morphological changes in the brain after a traumatic exposure.

Psychological and pharmacological strategies for prevention and treatment

Current approaches to PTSD prevention span a variety of psychological and pharmacological categories, which can be divided into three subgroups: primary prevention (before the traumatic event, including prevention of the event itself), secondary prevention (between the traumatic event and the development of PTSD), and tertiary prevention (after the first symptoms of PTSD become apparent). The secondary and tertiary prevention of PTSD has abundant methods, including different forms of debriefing, treatments for Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) or acute PTSD, and targeted intervention strategies. Meanwhile, the process of primary prevention is still in its infancy and faces several challenges.

Based on current research on the primary prevention of post-trauma pathology, psychological and pharmacological interventions for particular groups or individuals (e.g., military personnel, firefighters, etc.) with a high risk of traumatic event exposure were applicable and acceptable for PTSD sufferers. Of the studies that reported possible psychological prevention effects, training generally included a psychoeducational component and a skills-based component relating to stress responses, anxiety reducing and relaxation techniques, coping strategies and identifying thoughts, emotion and body tension, choosing how to act, attentional control, emotion control and regulation [ 30 , 31 , 32 ]. However, efficiency for these training has not been evaluated yet due to a lack of high-level evidence-based studies. Pharmacological options have targeted the influence of stress on memory formation, including drugs relating to the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the autonomic nerve system (especially the sympathetic nerve system), and opiates. Evidence has suggested that pharmacological prevention is most effective when started before and early after the traumatic event, and it seems that sympatholytic drugs (alpha and beta-blockers) have the highest potential for primary prevention of PTSD [ 33 ]. However, one main difficulty limiting the exploration in this field is related to rigorous and complex ethical issues, as the application of pre-medication for special populations and the study of such options in hazardous circumstances possibly touches upon questions of life and death. Significantly, those drugs may have potential side effects.

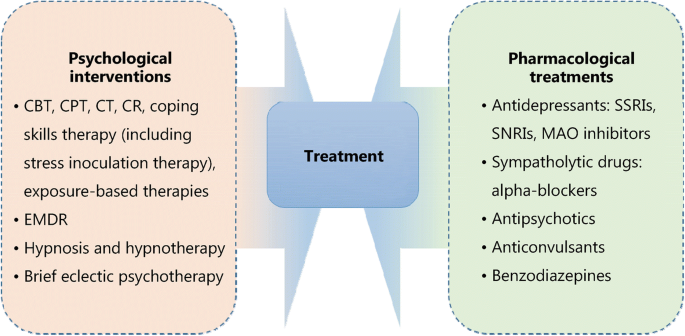

There are several treatment guidelines for patients with PTSD produced by different organizations, including the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS), the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, and the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (VA, DoD) [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Additionally, a large number of research studies are aiming to evaluate an effective treatment method for PTSD. According to these guidelines and research, treatment approaches can be classified as psychological interventions and pharmacological treatments (Fig. 1 ); most of the studies provide varying degrees of improvement in individual outcomes after standard interventions, including PTSD symptom reduction or remission, loss of diagnosis, release or reduction of comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions, quality of life, disability or functional impairment, return to work or to active duty, and adverse events.

Psychological and pharmacological strategies for treatment of PTSD. CBT. Cognitive behavioral therapy; CPT. Cognitive processing therapy; CT. Cognitive therapy; CR. Cognitive restructuring; EMDR. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; SSRIs. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRIs. Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; MAO. Monoamine oxidase

Most guidelines identify trauma-focused psychological interventions as first-line treatment options [ 39 ], including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), cognitive therapy (CT), cognitive restructuring (CR), coping skills therapy (including stress inoculation therapy), exposure-based therapies, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), hypnosis and hypnotherapy, and brief eclectic psychotherapy. These treatments are delivered predominantly to individuals, but some can also be conducted in family or group settings. However, the recommendation of current guidelines seems to be projected empirically as research on the comparison of outcomes of different treatments is limited. Jonas et al. [ 40 ] performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis of the evidence for treatment of PTSD. The study suggested that all psychological treatments showed efficacy for improving PTSD symptoms and achieving the loss of PTSD diagnosis in the acute phase, and exposure-based treatments exhibited the strongest evidence of efficacy with high strength of evidence (SOE). Furthermore, Kline et al. [ 41 ] conducted a meta-analysis evaluating the long-term effects of in-person psychotherapy for PTSD in 32 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including 2935 patients with long-term follow-ups of at least 6 months. The data suggested that all studied treatments led to lasting improvements in individual outcomes, and exposure therapies demonstrated a significant therapeutic effect as well with larger effect sizes compared to other treatments.

Pharmacological treatments for PTSD include antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, sympatholytic drugs such as alpha-blockers, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, and benzodiazepines. Among these medications, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, topiramate, risperidone, and venlafaxine have been identified as efficacious in treatment. Moreover, in the Jonas network meta-analysis of 28 trials (4817 subjects), they found paroxetine and topiramate to be more effective for reducing PTSD symptoms than most other medications, whereas evidence was insufficient for some other medications as research was limited [ 40 ]. It is worth mentioning that in these studies, efficacy for the outcomes, unlike the studies of psychological treatments, was mostly reported as a remission in PTSD or depression symptoms; other outcomes, including loss of PTSD diagnosis, were rarely reported in studies.

As for the comparative evidence of psychological with pharmacological treatments or combinations of psychological treatments and pharmacological treatments with other treatments, evidence was insufficient to draw any firm conclusions [ 40 ]. Additionally, reports on adverse events such as mortality, suicidal behaviors, self-harmful behaviors, and withdrawal of treatment were relatively rare.

PTSD is a high-profile clinical phenomenon with a complicated psychological and physical basis. The development of PTSD is associated with various factors, such as traumatic events and their severity, gender, genetic and epigenetic factors. Pertinent studies have shown that PTSD is a chronic impairing disorder harmful to individuals both psychologically and physically. It brings individual suffering, family functioning disorders, and social hazards. The definition and diagnostic criteria for PTSD remain complex and ambiguous to some extent, which may be attributed to the complicated nature of PTSD and insufficient research on it. The underlying mechanisms of PTSD involve changes in different levels of psychological and molecular modulations. Thus, research targeting the basic mechanisms of PTSD using standard clinical guidelines and controlled interference factors is needed. In terms of treatment, psychological and pharmacological interventions could relief PTSD symptoms to different degrees. However, it is necessary to develop systemic treatment as well as symptom-specific therapeutic methods. Future research could focus on predictive factors and physiological indicators to determine effective prevention methods for PTSD, thereby reducing its prevalence and preventing more individuals and families from struggling with this disorder.

Abbreviations

American Psychiatric Association

Acute stress disorder

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Catechol-O-methyl-transferase

Cognitive processing therapy

Complex posttraumatic stress disorder

Cognitive restructuring

C-reactive protein

Cognitive therapy

Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

Disturbances in self-organization

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids receptor

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

International classification of diseases

Impact of events scale

Interleukin-1beta

Interleukin-6

Institute of Medicine

Intimate partner violence

International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies

Monoamine oxidase

Major depressive disorder

United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

Non-suicidal self-injury

Posttraumatic diagnostic scale

Posttraumatic stress disorder

Randomized controlled trials

Rostral ventromedial prefrontal cortex

Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors;

Strength of evidence

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

DoD Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense

Veterans Health Administration

World Health Organization

White J, Pearce J, Morrison S, Dunstan F, Bisson JI, Fone DL. Risk of post-traumatic stress disorder following traumatic events in a community sample. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2015;24(3):1–9.

Article Google Scholar

Kendell RE. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd ed., revised (DSM-III-R). America J Psychiatry. 1980;145(10):1301–2.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. America J Psychiatry. 2013. doi: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.744053 .

Maercker A, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, Cloitre M, Reed GM, Van OM, et al. Proposals for mental disorders specifically associated with stress in the international classification of Diseases-11. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1683–5.

Brewin CR, Cloitre M, Hyland P, Shevlin M, Maercker A, Bryant RA, et al. A review of current evidence regarding the ICD-11 proposals for diagnosing PTSD and complex PTSD. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;58(1): 1–15.

Google Scholar

Nash WP, Litz BT. Moral injury: a mechanism for war-related psychological trauma in military family members. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013;16(4):365–75.

Nazarov A, Fikretoglu D, Liu A, Thompson M, Zamorski MA. Greater prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in deployed Canadian Armed Forces personnel at risk for moral injury. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;137(4):342–54.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychol Assess. 1997;9(9):445–51.

Gnanavel S, Robert RS. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th edit) and the impact of events scale-revised. Chest. 2013;144(6):1974–5.

Reijnen A, Rademaker AR, Vermetten E, Geuze E. Prevalence of mental health symptoms in Dutch military personnel returning from deployment to Afghanistan: a 2-year longitudinal analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):341–6.

Sundin J, Herrell RK, Hoge CW, Fear NT, Adler AB, Greenberg N, et al. Mental health outcomes in US and UK military personnel returning from Iraq. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(3):200–7.

Macera CA, Aralis HJ, Highfill-McRoy R, Rauh MJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder after combat zone deployment among navy and marine corps men and women. J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(6):499–505.

Macgregor AJ, Tang JJ, Dougherty AL, Galarneau MR. Deployment-related injury and posttraumatic stress disorder in US military personnel. Injury. 2013;44(11):1458–64.

Sandweiss DA, Slymen DJ, Leardmann CA, Smith B, White MR, Boyko EJ, et al. Preinjury psychiatric status, injury severity, and postdeployment posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(5):496–504.

Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Gima K, Chu A, Marmar CR. Getting beyond "Don't ask; don't tell": an evaluation of US veterans administration postdeployment mental health screening of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(4):714–20.

Street AE, Rosellini AJ, Ursano RJ, Heeringa SG, Hill ED, Monahan J, et al. Developing a risk model to target high-risk preventive interventions for sexual assault victimization among female U.S. army soldiers. Clin Psychol Sci. 2016;4(6):939–56.

Olatunji BO, Ciesielski BG, Tolin DF. Fear and loathing: a meta-analytic review of the specificity of anger in PTSD. Behav Ther. 2010;41(1):93–105.

Evans L, Cowlishaw S, Hopwood M. Family functioning predicts outcomes for veterans in treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Fam Psychol. 2009;23(4):531–9.

Mckinney JM, Hirsch JK, Britton PC. PTSD symptoms and suicide risk in veterans: serial indirect effects via depression and anger. J Affect Disord. 2017;214(1):100–7.

Briggsgowan MJ, Carter AS, Ford JD. Parsing the effects violence exposure in early childhood: modeling developmental pathways. J Pediatric Psychol. 2012;37(1):11–22.

Enlow MB, Blood E, Egeland B. Sociodemographic risk, developmental competence, and PTSD symptoms in young children exposed to interpersonal trauma in early life. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(6):686–94.

Newport DJ, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr Opin eurobiol. 2009;14(1 Suppl 1):13.

Neigh GN, Ali FF. Co-morbidity of PTSD and immune system dysfunction: opportunities for treatment. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;29:104–10.

Passos IC, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Costa LG, Kunz M, Brietzke E, Quevedo J, et al. Inflammatory markers in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1002.

Eraly SA, Nievergelt CM, Maihofer AX, Barkauskas DA, Biswas N, Agorastos A, et al. Assessment of plasma C-reactive protein as a biomarker of posttraumatic stress disorder risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(4):423.

Lebois LA, Wolff JD, Ressler KJ. Neuroimaging genetic approaches to posttraumatic stress disorder. Exp Neurol. 2016;284(Pt B):141–52.

Zhang K, Qu S, Chang S, Li G, Cao C, Fang K, et al. An overview of posttraumatic stress disorder genetic studies by analyzing and integrating genetic data into genetic database PTSD gene. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;83(1):647–56.

Bolzenius JD, Velez CS, Lewis JD, Bigler ED, Wade BSC, Cooper DB, et al. Diffusion imaging findings in US service members with mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000378 [Epub ahead of print].

Logue MW, Rooij SJHV, Dennis EL, Davis SL, Hayes JP, Stevens JS, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: a multi-site ENIGMA-PGC study. Biol. Psychiatry . 2018;83(3):244–53.

Sijaric-Voloder S, Capin D. Application of cognitive behavior therapeutic techniques for prevention of psychological disorders in police officers. Health Med. 2008;2(4):288–92.

Deahl M, Srinivasan M, Jones N, Thomas J, Neblett C, Jolly A. Preventing psychological trauma in soldiers: the role of operational stress training and psychological debriefing. Brit J Med Psychol. 2000;73(1):77–85.

Wolmer L, Hamiel D, Laor N. Preventing children's posttraumatic stress after disaster with teacher-based intervention: a controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(4):340–8 348.e1–2.

Skeffington PM, Rees CS, Kane R. The primary prevention of PTSD: a systematic review. J Trauma Dissociation. 2013;14(4):404–22.

Jaques H. Introducing the national institute for health and clinical excellence. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(17):2111–2.

PubMed Google Scholar

Schnyder U. International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS). Psychosomatik Und Konsiliarpsychiatrie. 2008;2(4):261.

Bulger RE. The institute of medicine. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1992;2(1):73–7.

Anderle R, Brown DC, Cyran E. Department of Defense[C]. African Studies Association. 2011;2011:340–2.

Feussner JR, Maklan CW. Department of Veterans Affairs[J]. Med Care. 1998;36(3):254–6.

Sripada RK, Rauch SA, Liberzon I. Psychological mechanisms of PTSD and its treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(11):99.

Jonas DE, Cusack K, Forneris CA, Wilkins TM, Sonis J, Middleton JC, et al. Psychological and pharmacological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Agency Healthcare Res Quality (AHRQ). 2013;4(1):1–760.

Kline AC, Cooper AA, Rytwinksi NK, Feeny NC. Long-term efficacy of psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59:30–40.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We thank Jamie Bono for providing professional writing suggestions.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371084 and 31171013 by ZJL), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81100276 by XRM).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Third Affiliated Hospital of Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China

Xue-Rong Miao, Qian-Bo Chen, Kai Wei, Kun-Ming Tao & Zhi-Jie Lu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ZJL and XRM conceived the project. QBC, KW and KMT conducted the article search and acquisition. XRM and QBC analyzed the data. XRM wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and discussed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Xue-Rong Miao .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not Applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Miao, XR., Chen, QB., Wei, K. et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder: from diagnosis to prevention. Military Med Res 5 , 32 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-018-0179-0

Download citation

Received : 20 March 2018

Accepted : 10 September 2018

Published : 28 September 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-018-0179-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cognitive impairment

- Psychological interventions

- Neuroendocrine

Military Medical Research

ISSN: 2054-9369

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 20 September 2021

Prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and threat processing: implications for PTSD

- M. Alexandra Kredlow 1 na1 ,

- Robert J. Fenster 2 na1 ,

- Emma S. Laurent ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4820-8332 1 ,

- Kerry J. Ressler ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5158-1103 2 &

- Elizabeth A. Phelps ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6215-8159 1

Neuropsychopharmacology volume 47 , pages 247–259 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

41k Accesses

78 Citations

61 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Posttraumatic stress disorder can be viewed as a disorder of fear dysregulation. An abundance of research suggests that the prefrontal cortex is central to fear processing—that is, how fears are acquired and strategies to regulate or diminish fear responses. The current review covers foundational research on threat or fear acquisition and extinction in nonhuman animals, healthy humans, and patients with posttraumatic stress disorder, through the lens of the involvement of the prefrontal cortex in these processes. Research harnessing advances in technology to further probe the role of the prefrontal cortex in these processes, such as the use of optogenetics in rodents and brain stimulation in humans, will be highlighted, as well other fear regulation approaches that are relevant to the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and involve the prefrontal cortex, namely cognitive regulation and avoidance/active coping. Despite the large body of translational research, many questions remain unanswered and posttraumatic stress disorder remains difficult to treat. We conclude by outlining future research directions related to the role of the prefrontal cortex in fear processing and implications for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Post-traumatic stress disorder: clinical and translational neuroscience from cells to circuits

Kerry. J. Ressler, Sabina Berretta, … William A. Carlezon Jr

Prefrontal-hippocampal interactions supporting the extinction of emotional memories: the retrieval stopping model

Michael C. Anderson & Stan B. Floresco

Sex differences in auditory fear discrimination are associated with altered medial prefrontal cortex function

Harriet L. L. Day, Sopapun Suwansawang, … Carl W. Stevenson

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a maladaptive and debilitating psychiatric disorder typically accompanied by an extreme sense of fear at the time of trauma occurrence, with characteristic re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptoms in the months and years following the trauma. PTSD has a prevalence of ~6% but can occur in 25–35% of individuals who have experienced severe psychological trauma, such as combat veterans, refugees, and assault victims [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. The differential risk determining those who do versus those who do not develop PTSD is multifactorial [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. It is in part genetic, with at least 30–40% risk heritability for PTSD following trauma [ 8 , 9 , 10 ], and in part depends on past personal history, including adult and childhood trauma and psychological factors which may differentially mediate fear and emotion regulation. Additionally, considerable evidence now supports a model in which PTSD can be viewed, in part, as a disorder of fear dysregulation. This is advantageous because the neural circuitry underlying threat and fear-related behaviors in mammals, including the amygdala–hippocampus–medial prefrontal circuit, is among the most well-understood behavioral circuits in neuroscience [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Further, the study of threat behavior and its underlying circuitry has led to some of the most rapid progress in understanding learning and memory processes.

Although the amygdala and other subcortical regions are perhaps best understood with relationship to threat processing across species, burgeoning evidence has provided substantial support for the role of different regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) in particular in regulating the encoding of threat-related behaviors across species and the emotion of fear in humans. Furthermore, the PFC has a critical role in threat inhibition and extinction, as well as in processes such as emotion regulation and avoidance.

In contrast to the promise of current scientific approaches, in the clinic PTSD remains very difficult to treat [ 15 , 16 ]. The best current treatments are in the form of exposure-based cognitive-behavioral therapies, which are thought to act on the neurocircuitry of threat extinction, in particular through the PFC. The medication treatments for PTSD are primarily limited to traditional serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, which are used for a broad range of depression and anxiety disorders. Advances in understanding the neural circuit of regulation of threat, fear, and PTSD symptoms may lead to novel and more robust treatment approaches.

This review aims to synthesize our current understanding of the role of the PFC in threat behaviors and threat-related emotional processing, and the role of multiple PFC subregions in PTSD. As acknowledged, this line of research is relevant to the treatment of disorders characterized by fear, such as PTSD. However, in line with the two-system view of fear and anxiety [ 17 ] and in order to not make assumptions about emotional states, the term “threat” will be used when referring to the behavioral, psychophysiological, or neural outcomes of conditioning research. The term “fear” will be reserved for describing studies in which the subjective emotion of fear was assessed or discussing the emotion more generally.

Nonhuman animal research on threat processing

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of the rodent regulates a balance between goal-oriented and habitual behaviors [ 18 , 19 ]. The mPFC receives massive inputs from subcortical structures, including the amygdala, hippocampus, ventral striatum, hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray, and cerebellum, among others, that allow it to integrate the behavioral state of the animal and adjust behavioral decisions on a moment-to-moment basis. One of the most important mPFC functions is to integrate information about potential threats in the environment with other organismal drives to determine behavioral outputs [ 20 ].

Decades of basic research on the mPFC in rodents indicate that it plays a key role in the expression and storage of the Pavlovian threat response and the establishment of threat-related extinction memories [ 21 ]. Technological advances have evolved from lesion and pharmacologic studies to experiments utilizing circuit-perturbing and single-cell approaches, which are beginning to provide data at the cell-type resolution for the role of this critical structure in the threat response. Below, we will briefly review the anatomy of the rodent mPFC, the data implicating mPFC circuitry in the threat response and in threat extinction, molecular changes in mPFC cell types with threat acquisition and extinction, and future steps in these lines of research.

Anatomy of rodent mPFC

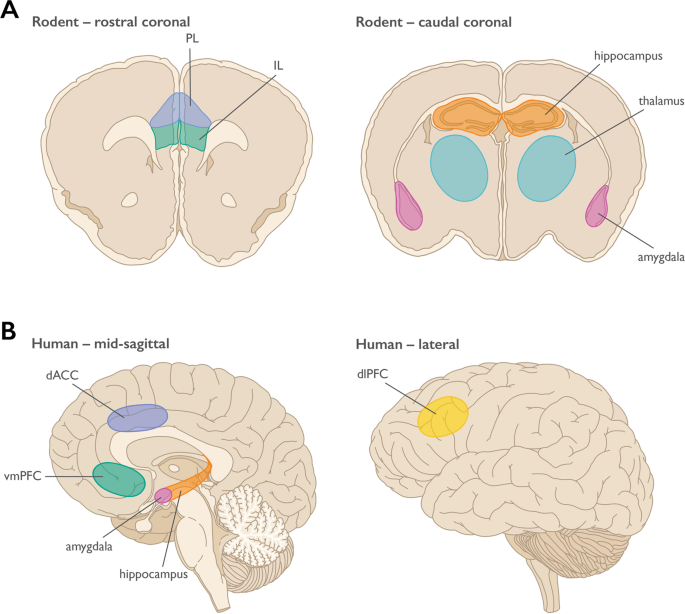

Like most cortical regions, the mPFC is a multi-layered structure of heterogeneous cell types, composed of excitatory pyramidal neurons, inhibitory interneurons, and support cells. Beginning with Brodmann, there have been debates about the existence and location of the mPFC in rodents due to the lack of a prominent granular layer [ 22 ; see Preuss and Wise, this issue]. Cross-species comparisons can be more easily made with respect to connectivity patterns [ 23 ]. The rodent mPFC is generally considered to consist of the medial precentral area (Fr2), the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), prelimbic cortex (PL), and infralimbic cortex (IL) [ 24 ] (see Fig. 1a ).

a Rodent anatomy highlighting regions involved in threat learning, extinction, avoidance, and the contextual modulation of threat expression; b Human anatomy highlighting regions involved in threat learning, extinction, avoidance, cognitive regulation, and the contextual modulation of threat expression. PL = prelimbic cortex, IL = infralimbic cortex; dACC = dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, vmPFC = ventromedial prefrontal cortex, dlPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

For the purposes of this review, we will focus on rodent PL and IL, although recent work has implicated dACC in observational threat pathways, which may be relevant to PTSD from witnessed trauma [ 25 ]. Histologically in the mouse, PL and IL differ in the thickness of layer II/III and the prominence of layer separations between superficial II/III and layer V; however, this boundary is not easily demarcated [ 26 , 27 ]. Both PL and IL receive cortical input, as well as unidirectional projections from the hippocampus, mainly CA1 and subiculum [ 24 ]. Projections to the amygdala are bidirectional, although there are differences in the projection patterns of PL and IL to the amygdaloid complex, and there is some controversy about whether PL and IL synapse onto functionally different cell types [ 28 , 29 ]. Although there is some overlap in projection patterns, IL projects most heavily to lateral septum, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, amygdala, hypothalamus, and brainstem, while PL sends more projections to insular cortex, nucleus accumbens, thalamus, and raphe nuclei [ 29 ]. The differences in these projection patterns suggest diverging functional roles for these adjacent structures.

Evidence for PL/IL distinction

For the past 20 years, there has been an extensive, although debated, literature showing differential roles for PL and IL in threat conditioning and threat extinction [ 21 ]. The first study to demonstrate a role for the rodent ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) came from Morgan et al., who lesioned the mPFC [ 30 ]. A follow-up study demonstrated that more dorsal areas of the mPFC affected threat learning, while more ventral mPFC was required for threat extinction [ 31 ]. Quirk et al. supported this result when they [ 32 ] performed electrolytic lesions of the rat vmPFC and assessed threat extinction memory. They found that lesions that included caudal IL ablated threat extinction memories, while those that excluded the area had no effect. Pharmacological inactivation of PL and IL with agents such as the GABA agonist muscimol further suggested opposing roles for these structures in threat conditioning and threat extinction, respectively [ 33 ]. However, these results have not been universally reproduced [ 34 , 35 ]. More recent studies from the Quirk laboratory have used optogenetics to drive or inhibit activity in excitatory IL neurons during threat extinction. These data suggest that IL neurons are necessary for encoding threat extinction memories but may not be necessary for threat extinction memory storage or retention [ 36 ]. These findings also suggest that the threat extinction memory trace may be represented by different cell populations over time. Indeed, it has been known that the threat memory is likely constituted by a distributed network of cells across a range of brain regions. Inputs to the mPFC likely help to drive evolution of the memory trace over time.

Modulation of mPFC by subcortical structures

Because the mPFC must guide behavior on a moment-to-moment basis, it needs to receive a constant stream of information from subcortical structures and send out a coordinated response. The mPFC receives dense innervation from many subcortical structures, but we will focus here upon three crucial inputs: the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus. The canonical role of the hippocampus in threat circuitry is to encode context-specific information of a threat trace, as it is crucial for an organism to be able to distinguish threats as belonging to a particular context. The hippocampus itself appears to have a dorsal-ventral functional gradient, with the dorsal hippocampus encoding context more specifically, while the ventral hippocampus (vHPC) includes affective information as well [ 37 ].

The vHPC sends dense direct projections to the mPFC from CA1, but also bidirectional disynaptic indirect connections to the mPFC through the reuniens nucleus of the thalamus and the perirhinal cortex [ 38 ]. Lesion studies of the hippocampus suggest a critical role in context processing [ 39 ]. Reversible inactivation of the dorsal hippocampus, through either pharmacologic or chemogenetic means, interferes with context-specific information of a threat memory [ 40 , 41 ]. Inhibition of double-projecting vHPC neurons to the mPFC and basolateral amygdala (BLA) interferes with contextual threat recall [ 42 ] and disconnection of the vHPC from the mPFC interferes with renewal of threat memories, a context-dependent process [ 43 ]. Activity-tagging coupled with optogenetic inhibition suggests that threat conditioning and extinction memories exist in separate populations of neurons within the hippocampus [ 44 ], and the hippocampus may influence mPFC activity through feed-forward inhibition mechanisms through parvalbumin interneurons [ 45 ]. In return, the mPFC appears to suppress expression of erroneous contexts in a “top-down” manner through a disynaptic pathway through the reuniens nucleus of the thalamus [ 46 ]. In addition, there may be more routes of information flow from the PFC to the hippocampus, including direct routes from the nearby anterior cingulate [ 47 ].

The amygdala communicates the salience of the threat cue to the mPFC (see Murray and Fellows, this issue, for further discussion of amygdala-PFC interactions). For thirty years, the amygdala has been implicated in both threat learning [ 48 ] and threat extinction [ 49 ] processes. The BLA sends bidirectional projections to the mPFC [ 50 ]. There is evidence to suggest that there is a dorso-ventral topographic segregation of BLA input to the mPFC; more dorsal projections (to PL) encode threat-stimulating information while more ventral projections (to IL) encode threat extinction-related information [ 51 ]. Synaptic connections between PL neurons and BLA inputs also strengthen in response to stress, in part through endocannabinoid-mediated mechanisms [ 52 ]. Projection neurons within the BLA exhibit plasticity when conditioned stimulus-unconditioned stimulus pairings occur and convey this information to the mPFC.

Finally, nuclei within the thalamus help bind threat memories to context and facilitate shifts in the mPFC threat memory trace over time. The reuniens nucleus of the thalamus coordinates oscillatory synchrony between the mPFC and the vHPC, which is necessary for proper contextual representation of threat memories [ 46 , 53 ]. The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus plays a crucial role in the encoding of threat memories over time [ 54 ] and appears to be necessary in shifting the temporal nature of how the mPFC encodes threat memories [ 55 ].

Molecular pathways in rodent mPFC

At the molecular level, threat conditioning and extinction are associated with epigenetic, transcriptional, and translational changes that likely modify synaptic weights and cell firing properties that persistently alter circuit function. Introduction of the translational inhibitor anisomycin, either intraventricularly or into the mPFC, causes a failure to retain threat extinction memories. This suggests that translation of new protein is necessary for the formation of a novel threat extinction memory [ 56 ]. Threat conditioning and threat recall are associated with unique, cell-type-specific transcriptional changes that persist for weeks after initial training [ 57 ]. Threat extinction also requires transcriptional processes within IL: injection of an inhibitor of PARP-1, a gene involved in ADP-ribosylaton that is necessary for transcription, into mPFC impairs contextual threat extinction [ 58 ].

The BDNF-TrkB neurotrophic factor pathway has also been extensively studied with regards to mPFC and memory formation in mPFC. Expression of Bdnf in PL is necessary for consolidation of cued threat conditioning [ 59 ], while infusion of Bdnf into IL after threat acquisition is sufficient to diminish threat responses in the absence of extinction training [ 60 ]. Threat extinction is also associated with epigenetic modification. In the IL, threat extinction is associated with acetylation of histones near the Bdnf locus [ 61 ], changes to the p300/CBP complex (PCAF) [ 62 ], as well as deposition of DNA-modification marks such as 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and N6-methyl-2’deoxyadenosine (m6dA) near loci of activity-dependent genes such as Bdnf .

Additionally, inhibition of PCAF in IL was shown to interfere with threat extinction [ 62 ]. Recently, Li et al. [ 63 ], have shown that knockdown of N6amt1 , the gene responsible for m6dA deposition, within IL, blocks changes to the m6dA mark at the Bdnf promoter in vivo and impairs threat extinction retention. These findings suggest that alterations in m6dA deposition are necessary for the formation of threat extinction memories within IL [ 63 ]. These findings also strongly support the hypothesis that threat extinction memory requires epigenetic changes within IL. Our understanding of the molecular changes that occur within the mPFC during threat-related processes are still in their infancy. Gene expression changes are unique to cell type, and cell-type-specific investigations of mPFC in threat conditioning and extinction are just beginning.

Stress and threat reactions

One potential factor that alters the ability to control emotional responses via altering PFC function is stress (for review, see 64,65, Kalin and Barbas, this issue). Studies in animal models have shown that acute stress leads to changes in neuronal signaling that impair function in the dlPFC [ 64 ] and IL cortex [ 66 ]. These changes are proposed to be due to the impact of increased catecholamines, in particular noradrenergic and dopaminergic signaling, on PFC neuronal activity with even relatively mild acute stress exposure [ 64 , 65 , 67 ]. Stress also impacts signaling within the amygdala. Noradrenergic signaling from the locus coeruleus to the amygdala was recently shown to be necessary to produce the immediate extinction deficit, an impairment in extinction learning that occurs soon after fear learning and is thought to be related to the stress of the fear learning process [ 68 ]. Activity of CRF-expressing neurons within the CeA was also recently shown to contribute to this phenomenon [ 69 ]. In rodents, chronic stress also impacts neural activity in both PL and IL cortex [ 70 ] and leads to structural changes in IL cortex [ 71 ]. One consequence of stress-related PFC impairment is enhanced threat learning and impaired extinction retention in rodent models [ 66 , 70 ].

In the next section we will explore the role of PFC in human threat processing research, from acquisition and encoding of threat, to its extinction and extinction recall. We will also further integrate additional findings with regards to other threat and avoidance behaviors in response to threat stimuli and the impact of stress on the PFC. Finally, we will examine how these different brain regions and behaviors are dysregulated in threat-related disorders such as PTSD.

Preclinical human threat processing research

Threat learning.

Perhaps it is not surprising, given the extensive research with nonhuman animals, that research in humans confirms a role for the amygdala and PFC in threat learning (see Fig. 1b and Fig. 2a ). The role of the amygdala was first demonstrated in patients with amygdala damage. Relative to healthy controls, both bilateral [ 72 ] and unilateral [ 73 ] amygdala damage resulted in impaired conditioned responses, as measured by the skin conductance response (SCR). However, these patients were able to verbally report the contingency between the conditioned stimulus and shock after the procedure, which was impaired in patients with hippocampal damage whose amygdala was intact [ 72 , 74 ]. These findings suggest that the amygdala is only critical for the implicit, physiological expression of threat learning in humans, with conscious knowledge about the threatening nature of stimuli in the environment remaining intact, despite amygdala lesions. Furthermore, these findings demonstrate that there are additional brain regions that are critical for the expression of the subjective fear and threat responses, including PFC areas that are discussed in more detail below.

a Healthy Threat Circuit. Regions involved in threat learning and the control of threat reactions via extinction, context, avoidance, or cognitive regulation. In healthy individuals the coordination of this circuit enables adaptive threat expression. b PTSD Threat Circuit. The dlPFC, vmPFC/IL, and hippocampus show impaired functioning with PTSD, whereas the amygdala and dACC/PL are enhanced. Disrupted connections between regions are indicated by dashed lines. The disrupted threat circuit with PTSD results in maladaptive threat expression. Prefrontal cortex regions are highlighted within the beige circle. Terms for animal/human homologous regions are in the same circles. PL = prelimbic cortex, IL = infralimbic cortex, dACC = dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, vmPFC = ventromedial prefrontal cortex, dlPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Consistent with these early patient studies, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies soon followed that showed increased blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal in the amygdala to a conditioned stimulus (relative to stimulus never paired with shock) [ 75 , 76 ], and the magnitude of this BOLD response was correlated with the strength of the conditioned response [ 76 ]. Interestingly, this differential amygdala BOLD response was only apparent in the early stages of threat conditioning. This finding is somewhat surprising given rodent research showing long-lasting changes in the amygdala lateral nucleus with threat learning. However, there is electrophysiological evidence in rodents showing that a subset of lateral nucleus amygdala neurons respond preferentially during initial learning [ 77 ], and there is greater responding overall at this time. It may be the case that BOLD changes in the amygdala can only be observed at time windows when there are larger populations of neurons responding, such as initial learning. One major limitation of fMRI for investigations of amygdala function in humans is that it is a relatively coarse measurement. Although the spatial resolution of standard BOLD imaging is generally 3 mm, in practice, with spatial smoothing and group averaging, the actual resolution is greater than 10 mm, which covers a substantial portion of the amygdala (which is slightly more than 1000 mm 3 in humans) and makes it very difficult to detect discrete responses in amygdala subnuclei. The challenges of using BOLD imaging to study the human amygdala is reflected in recent meta-analyses of fMRI threat learning studies, which fail to find BOLD changes in the amygdala [ 78 ], in spite of its critical role in threat learning in rodent models and patient studies.

In contrast to difficulties in detecting BOLD changes in the amygdala during threat learning, meta-analyses and individual studies reliably show activation in a number of other brain regions, including the insula cortex, which is linked to physiological arousal responses [ 79 ], the striatum, and the dACC (e.g., [ 76 , 78 , 80 ]). The dACC is a prefrontal region that is proposed to be the human homolog of the PL cortex in rodents [ 80 ]. As discussed earlier, the PL in rodents has been suggested to play a role in the expression of threat learning via projections to the basolateral amygdala, with stimulation of this region increasing conditioned freezing and inactivation reducing it.

In rodents, the PL and IL cortex are located adjacent to one another in the mPFC. In primate models, however, the PL and IL are farther apart. The primate PL cortex is thought to be divided into rostral and caudal regions with different connectivity patterns. The rostral region is thought to be more similar to the PL in rodents, with the dACC being the human homologue for that region [ 23 , 81 ]. Consistent with this suggestion, Milad et al. [ 80 ] found that both cortical thickness, and BOLD response magnitude to a conditioned stimulus in this region, were correlated with the strength of the conditioned response as measured with SCR in humans.

Although the basic circuitry of threat learning seems to be preserved across species, a primary difference between humans and other animals is that humans, more often than not, learn about threats in the environment via social interactions. For example, children learn to fear germs by being told about their existence and observing others engaging in actions attempting to avoid them. This ability is adaptive in that humans do not need to be physically harmed to learn about threats in the environment. It can also be maladaptive in that we can develop robust fears for events that are imagined and anticipated but never actually experienced, contributing greatly to human anxiety and fear-related disorders. To what extent do the brain systems involved in threat learning from direct experience, that have been investigated in rodent models, map onto socially acquired, imagined threats in humans?

To address this question, brain imaging and patient studies have examined threat learning through verbal instruction (e.g., being told a blue square predicts a shock, and then being shown a blue square) or observation (e.g., watching someone else receive a shock paired with a blue square, and then being shown a blue square). Consistent with Pavlovian threat conditioning, fMRI studies of both instructed and observational threat learning show activation in the amygdala, dACC, and insula [ 82 ]. For instructed learning, the amygdala BOLD response is left-lateralized [ 83 ], and only patients with left, but not right, amygdala damage show impaired physiological evidence of threat learning, perhaps because of the verbally mediated nature of this learning [ 84 ]. In contrast, observational learning results in increased bilateral BOLD signal in the amygdala, both when observing someone else receiving a shock paired with a conditioned stimulus (learning), and when viewing the conditioned stimulus afterwards (test). In addition, during observational learning, activation in a rostral mPFC region that has been implicated in mentalizing about others is correlated with the strength of the learned threat response as measured by SCR [ 85 ], and learning is stronger with greater empathy for the person being observed [ 86 ]. These results suggest that while the social learning of threat may engage unique neural circuitry due to the nature of the learning, it also takes advantage of the phylogenetically older mechanisms of Pavlovian threat conditioning for threat expression.

Threat extinction

Much like threat learning, neuroimaging studies of threat extinction in humans have identified brain regions that parallel those involved in extinction in rodents (see Figs. 1b and 2a ). The vmPFC is proposed to be the homologue for the IL in rodents [ 87 ] and serves to inhibit threat responses produced by the amygdala. There is consistent evidence of increases in BOLD signal in the vmPFC during extinction learning [ 88 , 89 , 90 ] and recall [ 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 ] (for review, see [ 93 , 94 , 95 ]). Further, the degree of activation of the vmPFC has been shown to be positively correlated with the degree of extinction, or extinction retention, as measured by SCR [ 89 , 90 ], consistent with the suggested role of the IL in extinction in rodent models.

Brain morphology studies also point to the human vmPFC being involved in extinction. Milad et al. [ 96 ] found vmPFC thickness to be positively correlated with extinction recall. Specifically, greater thickness was associated with smaller SCR to the conditioned stimulus during extinction recall, suggestive of better extinction recall (see also [ 97 ]). Subsequently, Winkelman et al. [ 98 ] examined the relationship between vmPFC thickness and extinction learning, rather than recall, and found similar results. Greater vmPFC thickness was associated with smaller differential SCR during early extinction learning, suggestive of better extinction learning.

Targeting extinction with neuromodulation, neuroplasticity, and context modulation

One drawback of these MRI studies, however, is that they are correlational in nature. Unlike research conducted in rodents, specific brain regions in humans cannot be lesioned or tagged, nor can regions that are not on the surface of the brain be disrupted. Researchers are able, however, to stimulate or disrupt surface frontal regions of the brain in humans using non-invasive devices. For example, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) applies a low-intensity current through two electrodes attached to the scalp, and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) delivers an electric current through a coiled wire placed on the scalp, creating a magnetic field across the skull. Both of these strategies are thought to modulate neuronal activity in the human brain.

Using these techniques, a few recent brain stimulation studies [ 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 ] have been conducted in humans to probe the role of the vmPFC in extinction. For example, Dittert et al. [ 100 ] administered tDCS via bitemporal electrodes aimed at the vmPFC prior to and during extinction and found that tDCS, relative to sham, stimulation resulted in faster early extinction learning. Similarly, Raij et al. [ 102 ] found that TMS, during extinction learning, to an area of the frontal cortex functionally connected to the vmPFC (i.e., the left lateral PFC), but not to an area of the frontal cortex thought to be unconnected to the vmPFC, led to enhanced extinction recall. Although these studies provide some insight into the role of the vmPFC in extinction, given the location of the vmPFC and the fact that tDCS and TMS are applied externally, it is difficult to be certain that the vmPFC in particular was stimulated in these studies.

Consistent with animal models of extinction circuitry, the vmPFC interacts with other regions such as the amygdala and hippocampus to modulate threat responses during extinction. From rodent research showing that intra-amygdala infusion of the NMDA receptor agonist d-cycloserine, which enhances NMDA-dependent plasticity, facilitates extinction learning, and successful translation of this work to humans (see [ 104 ] for review), we know that the human amygdala plays a role in extinction learning. Human imaging studies, however, have been less consistent with finding changes in BOLD signal in the amygdala during extinction [ 76 , 88 , 90 , 95 , 105 ]. Much like with threat acquisition, it may be that the involvement of the amygdala in extinction is more subtle and difficult to detect using standard fMRI techniques [ 106 ]. Nonetheless, imaging research does point to changes in the relationship between the PFC and amygdala during extinction. Connectivity analyses have demonstrated functional coupling between the mPFC and amygdala during extinction learning [ 107 ], and vmPFC and amygdala during extinction recall [ 89 , 108 ].

Also consistent with animal models (e.g., [ 40 ]), research suggests that the hippocampus is involved in contextual modulation of extinction and works in concert with the PFC during contextual extinction learning. One of the first studies demonstrating hippocampal involvement in extinction showed that patients with damage to the hippocampus failed to show contextually modulated reinstatement of conditioned responses following extinction [ 74 ]. Brain imaging studies of the contextual modulation of extinction typically manipulate the visual background during extinction and report hippocampal activation during extinction recall [ 89 , 91 , 92 ]. Importantly, functional connectivity analyses also suggest coupling of the PFC and hippocampus during contextual extinction learning [ 107 ] and recall [ 89 ].

Sleep is another factor that has been shown to modulate threat control in humans. Sleep has been shown to enhance both threat learning, and the generalization of extinction learning in humans and other animals. The documented role for sleep in memory consolidation is proposed to extend to both threat memories and extinction memories. Which of these competing memory representations is selectively strengthened depends on contextual factors such a recency of learning and replay [ 109 ]. Because of evidence for sleep’s modulation of extinction learning across species, it has been suggested that disruptions of sleep following acute trauma, or predating the traumatic experience, may contribute to the etiology or perpetuation of PTSD [ 110 ].

Avoidance/active coping

Another method of reducing conditioned threat reactions is through active avoidance or coping. Initial rodent research on the neural circuitry of active avoidance found that while the passive expression of conditioned threat responses engages a pathway from the lateral nucleus to the central nucleus, when the animal engages in an action to avoid the unconditioned stimulus, projections from the lateral nucleus to the basal nucleus to the nucleus accumbens are involved. However, in order for the animal to produce an avoidance action, conditioned freezing must be inhibited which requires the IL cortex, much like in the expression of extinction (see [ 111 ] for a review).

One benefit of avoidance learning over extinction for controlling threat reactions is that avoidance learning results in a persistent reduction in the passive conditioned response, even when the avoidance action is no longer available [ 112 ]. This is in contrast to extinction in which the conditioned response often returns through spontaneous recovery, renewal, or reinstatement. Both the acquisition of avoidance, and the reduction of the persistent conditioned threat reaction following avoidance learning, are blocked by the injection of protein synthesis inhibitors into the IL. This indicates that plasticity in the IL is critical for the persistent reduction of conditioned responses with avoidance [ 112 ]. Mirroring these findings, studies have shown that previous history with escapable shock results in a lasting reduction of the conditioned response, and this effect is eliminated with IL inactivation [ 113 ].

In humans, there is evidence that both avoidance learning and history with escapable shock can persistently reduce conditioned threat actions as measured with SCR, even when no avoidance action is available [ 114 , 115 ]. However, in order to persistently diminish threat conditioned responses in humans, avoidance actions need to be learned through trial and error and there needs to be a subjective sense of control over the unconditioned stimulus during learning [ 115 ]. Simply providing the option of an action to avoid the unconditioned stimulus yields no lasting reduction of conditioned responses when the avoidance action is no longer available, and in fact can increase them by preventing extinction learning (called “protection from extinction”, [ 116 ]). Consistent with the circuity of avoidance learning detailed in rodent models, trial-by-trial avoidance learning yields increased BOLD activation in the vmPFC and ventral striatum, relative to standard extinction [ 114 ], suggesting the brain mechanisms of active coping are preserved across species.

Emotion regulation

Although extinction and active coping can be investigated across species, humans have the unique ability to use cognitive strategies to alter emotional responses, such as responses to fear provoking stimuli (for review, [ 117 ]). One common emotion regulation strategy is cognitive reappraisal. This strategy involves reframing thoughts (also called “appraisals”) about a stimulus in order to change the emotional response that that stimulus evokes. Emotion regulation strategies can be employed with the goal of either upregulating (i.e., increasing) or downregulating (i.e., decreasing) emotions. Here, the primary focus is on data related to downregulating negative emotions, fear in particular, as these data are most relevant to PTSD and its treatment. We highlight reappraisal, which is proposed to be similar to cognitive restructuring in clinic. Neuroimaging research has provided insight into the brain regions involved in emotion regulation in humans. Studies to date suggest that emotion regulation strategies aimed at downregulating negative emotions engage cognitive control regions of the PFC, which then modulate the amygdala via various potential pathways to influence negative emotional responses.

The most recent meta-analysis of fMRI studies of emotion regulation [ 118 ] found that all strategies aimed at downregulating negative emotions were collectively associated with increased BOLD signal in the following areas: ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC). While these were the largest areas of convergence, activation was also found in other areas (i.e., the bilateral inferior parietal lobule, supplementary motor area, pre-supplementary motor area, left middle temporal gyrus, and posterior cingulate gyrus). These findings were relatively consistent with a prior meta-analysis [ 119 ], with the exception that the prior meta-analysis also found decreased BOLD signal in the amygdala and parahippocampal gyrus, consistent with the notion that cognitive control regions of the PFC modulate amygdala activity during emotion regulation. One potential reason for differing results across these two meta-analyses may be differences in the studies examined and proportions of various emotion regulation strategies included. There is some evidence that different emotion regulation strategies may recruit distinct brain regions. For example, Dörfel et al. [ 120 ] found that some emotion regulation strategies are associated with reduced activity in the amygdala, whereas others are not.

Nonetheless, the majority of imaging research to date on emotion regulation focuses on the strategy of cognitive reappraisal. Meta-analyses of cognitive reappraisal alone have consistently found increased BOLD signal in the dlPFC, vlPFC, and dmPFC [ 93 , 121 , 122 ] and decreased BOLD signal in the amygdala [ 93 , 121 ]. The dlPFC is thought to be an important driver of emotion regulation and hypothesized to be involved in the manipulation of appraisals of stimuli in working memory [ 121 , 122 , 123 ]. The vlPFC is hypothesized to support choosing and inhibiting appraisals of stimuli [ 121 , 124 , 125 ] or potentially may signal salience and the need to reappraise [ 122 ]. Finally, the dmPFC is hypothesized to support abstracting affective meaning of stimuli or the processes of self-reflecting and identifying one’s own affective reactions to stimuli [ 121 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 ].