EDITORIAL article

Editorial: emotional intelligence: current research and future perspectives on mental health and individual differences.

- 1 Giovanni Maria Bertin Department of Education Studies, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 2 Department of Management, College of Business, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, United States

- 3 Department of Psychology, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

Editorial on the Research Topic Emotional intelligence: Current research and future perspectives on mental health and individual differences

The last two decades have seen a steadily growing interest in emotional intelligence (EI) research and its applications. As a side effect of this boom in research activity, a flood of conceptualizations and measures of EI have been introduced. Consequently, the label “EI” has been used for a wide array of (often conflicting) models and measures, which has impeded consistent summaries of empirical evidence. This confusion among models/measures is problematic because different measurement approaches produce different results, which makes it difficult to theorize what EI really is or what it predicts since there is limited consistency in the empirical data. On one side there are proponents of the ability model (see Mayer et al., 2016 ) which recognizes that EI includes four distinct types of ability and defines EI as the ability to perceive and integrate emotion to facilitate thoughts, understand and regulate emotions to promote personal growth ( Mayer and Salovey, 1997 ). This kind of EI would only be measurable through maximum performance tests. On the opposite side, we find supporters of the trait model. In particular, Petrides et al. (2007) defines trait EI as a constellation of emotional perceptions assessed through questionnaires and rating scales. The theory of trait EI is summarized with applications from the domains of clinical, educational, and organizational psychology ( Petrides et al., 2016 ) and it's clearly distinguished from the notion of EI as a cognitive ability. Of course, there is no scarcity of other models and perspectives of EI, including mixed approaches, often used in professional setting to train and evaluate management potential and skills, that consider EI as a broad concept that includes (among others) motivations, interpersonal and intrapersonal abilities, empathy, personality factors and wellbeing (see Mayer et al., 2008 ).

In accordance with Hughes and Evans (2018) , we argue that various conceptualizations of EI may be considered constituents of existing perspectives of cognitive ability (ability EI), personality (trait EI), emotion regulation (EI competencies), and emotional awareness (the aptitude to conceptualize and describe one's own emotions and those of others). Across all models, EI involves handling emotions and putting them at the disposal of thinking activity. Although EI is an ability to understand and control emotions in general, this is only a small part of some models of EI. Indeed, trait EI concerns our perceptions of our emotional world and comprises a broad collection of traits linked to the opportunity of understanding, managing, and utilizing our own and other people's emotions, helping us figure out and dealing with emotional and social situations. All these facets are critical for intelligent behavior because they enable and facilitate our capacities for resilience, communication, and reasoning, to name a few, across the life span. Indeed, existing literature suggests that individual differences in EI consistently predict human behavior and EI is now recognized by the scientific community as a relevant psychological factor for several important real-life domains, including a successful socialization, community mental health and individual wellbeing. To advance the field both theoretically and practically, this special issue aims to provide new data which may help to critically review EI's theory.

The collection of articles is quite diverse and covers a number of issues relevant to an advancement of the field by including participants from several cultural contexts (e.g., Italian, Brazilian, and Turkish). Seven articles used self-report tools for the assessment of EI, while only two studies employed an ability measure (the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test). With regards to the topic being addressed, one study focuses on psychometrics, and confirms the validity of the Trait EI Questionnaire as an assessment tool for trait EI in a large Brazilian sample ( Zuanazzi et al. ), while seven analyzed the relationship between EI and research questions pertaining the domain of psychological health and wellbeing. Among these, the papers by García-Martínez et al. and Kökçam et al. analyze instead the relationship between EI and stress management in university students. García-Martínez et al. found mixed results compared to existing literature on the path from EI and academic achievement, while Kökçam et al. found that EI plays an important role in the identification of stress profiles.

Through a systematic review Pérez-Fernández et al. highlights that EI may be a protective factor of emotional disorders in general population and offers a starting point for a theoretical and practical understanding of the role played by EI in the management of diabetes. Along these lines Sergi et al. showed that the domains of EI involved in emotion recognition and control in the social context to reduce the risk to be affected by depression and anxiety, while Pulido-Martos et al. show the contribution of socioemotional resources (including EI) to the preservation of mental health. Iqbal et al. considered the associations among EI, relational engagement (RE) and cognitive outcomes (COs) and found that EI directly and indirectly influenced COs during the pandemic: the students with higher levels of EI and RE may achieve better COs.

Last, the two articles using the Mayer–Salovey–Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test show that coping strategies mediate the relationships of ability EI with both well- and ill-being ( MacCann et al. ), and give some preliminary evidence on the associations between ability EI, attachment security, and reflective functioning ( Rosso ).

Despite their specific aims, these studies demonstrate the importance to stake on individuals' EI to favor a high psychological and physical wellbeing. At the same time, the present articles collection highlights some open issues to be addressed by future research, including: putting order and possibly connecting the existence of many conflicting models and related measures of EI; deepen the study of the relation between EI with other partially overlapping constructs; identify the most helpful training to increase EI in individuals of all ages, such as children and their parents, adolescents, adults.

Author contributions

GM and FA drafted the editorial. RB, DJ, and ET participated in the discussion on the ideas presented and have edited and supervised the editorial. All authors approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Hughes, D. J., and Evans, T. R. (2018). Putting ‘emotional intelligences' in their place: introducing the integrated model of affect-related individual differences. Front. Psychol. 9, 2155. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02155

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., and Salovey, P. (2016). The ability model of emotional intelligence: principles and updates. Emot. Rev . 8, 290–300. doi: 10.1177/1754073916639667

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mayer, J. D., Roberts, R. D., and Barsade, S. G. (2008). Human abilities: emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol . 59, 507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646

Mayer, J. D., and Salovey, P. (1997). “What is emotional intelligence?,” in Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Educators , eds P. Salovey and D. Sluyter (New York, NY: Basic Books), 3–31.

Google Scholar

Petrides, K. V., Mikolajczak, M., Mavroveli, S., Sanchez-Ruiz, M.-J., Furnham, A., and Pérez-González, J.-C. (2016). Developments in trait emotional intelligence research. Emot. Rev . 8, 335–341. doi: 10.1177/1754073916650493

Petrides, K. V., Pita, R., and Kokkinaki, F. (2007). The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. Br. J. Psychol. 98, 273–289. doi: 10.1348/000712606X120618

Keywords: emotional intelligence, mental health, psychological wellbeing, individual differences, emotions

Citation: Mancini G, Biolcati R, Joseph D, Trombini E and Andrei F (2022) Editorial: Emotional intelligence: Current research and future perspectives on mental health and individual differences. Front. Psychol. 13:1049431. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1049431

Received: 20 September 2022; Accepted: 04 October 2022; Published: 13 October 2022.

Edited and reviewed by: Stefano Triberti , University of Milan, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Mancini, Biolcati, Joseph, Trombini and Andrei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Giacomo Mancini, giacomo.mancini7@unibo.it

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Emotional Intelligence Measures: A Systematic Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Basic Psychology, Faculty of Psychology and Speech Therapy, Universitat de València, 46010 Valencia, Spain.

- 2 Psychology Research Institute, Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Lima 15102, Peru.

- 3 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Universidad Nacional Federico Villarreal, San Miguel 15088, Peru.

- PMID: 34946422

- PMCID: PMC8701889

- DOI: 10.3390/healthcare9121696

Emotional intelligence (EI) refers to the ability to perceive, express, understand, and manage emotions. Current research indicates that it may protect against the emotional burden experienced in certain professions. This article aims to provide an updated systematic review of existing instruments to assess EI in professionals, focusing on the description of their characteristics as well as their psychometric properties (reliability and validity). A literature search was conducted in Web of Science (WoS). A total of 2761 items met the eligibility criteria, from which a total of 40 different instruments were extracted and analysed. Most were based on three main models (i.e., skill-based, trait-based, and mixed), which differ in the way they conceptualize and measure EI. All have been shown to have advantages and disadvantages inherent to the type of tool. The instruments reported in the largest number of studies are Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i), Schutte Self Report-Inventory (SSRI), Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test 2.0 (MSCEIT 2.0), Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS), Wong and Law's Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS), and Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue). The main measure of the estimated reliability has been internal consistency, and the construction of EI measures was predominantly based on linear modelling or classical test theory. The study has limitations: we only searched a single database, the impossibility of estimating inter-rater reliability, and non-compliance with some items required by PRISMA.

Keywords: emotional intelligence; measure; questionnaire; scale; systematic review; test.

Publication types

The Truth About Emotional Intelligence

For those who have it, it predicts success in many ways..

By Psychology Today Contributors published March 5, 2024 - last reviewed on March 6, 2024

A Brief History of Emotional Intelligence

Everyone values EI, but actually learning the component skills is another matter entirely.

By Marc Brackett, Ph.D., and Robin Stern, Ph.D.

Thirty-four years ago, in a world still debating whether emotions were a disruptive or adaptive force, two research psychologists proposed the concept of emotional intelligence . Peter Salovey and John Mayer contended that there is “a set of skills contributing to the accurate appraisal of emotions in self and others and the effective regulation of emotion in self and others” and that feelings could be harnessed to motivate oneself and to achieve in life. So unorthodox was the notion that people could benefit from their emotions that their article could find a home only in an obscure journal. Five years later, psychologist-writer Daniel Goleman, unconstrained by scholarly review processes, penned Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ , which widely popularized the idea.

Decades later, there exists a general understanding that emotions matter and can serve people’s goals ; emotions have a seat at the table. From gaslighting to rizz , recent words of the year, people have adopted the language of emotions. Parents want their children to have emotional intelligence, and the new field of social and emotional learning is helping teachers bring it into classrooms. Adults understand the importance of EI in relationships and consider it a desirable quality in a partner. CEOs see it as essential to the 21st-century workplace, a requirement for good decision-making , inspiring others, team functioning, and general productivity ; headhunters pose interview questions to assess it.

Further, we know from theory and some preliminary research that the skills of emotional intelligence actually matter. People who have them are healthier, happier, more effective, and more productive. EI predicts things of importance for children and adults. And if the worth of EI wasn’t clear before 2020, the pandemic halted so much social interaction—the growth medium of EI—that just about everyone hungered for human contact and stumbled in their social and emotional well-being.

However chastened the world is about the value of understanding yourself, maintaining friendships, and mastering daily frustrations, it’s inescapable that mental health in the U.S. has been declining in recent decades, especially among the young. If EI contributes to mental health and offers tools to address disappointments and uncertainties, how could that be?

As we see it, the number-one problem is implementation. People give lip service to wanting EI but don’t necessarily devote effort to gaining the skills. You can’t hold a one-hour workshop or put kids in a circle to talk about their feelings and call it EI. Emotional intelligence consists of a set of skills that advance developmentally, as people do, and their teaching has to be aligned with social and cognitive development. Just being aware of emotions is not enough. And you can’t teach EI to children unless you teach adults first; parents have to live it at home, teachers have to model it in school.

Becoming emotionally healthy and emotionally intelligent is hard work. That’s a hard sell in a culture that, over the past 30 years, has promoted the idea that you can gain mental health by taking a pill. Effort must go not only into gaining mental health but also maintaining it.

Emotional intelligence supports mental health, but it isn’t the whole of mental health. People get anxious or depressed for many reasons: Their biology may incline them to it. A partner suffers a debilitating experience. A breadwinner gets laid off. The more readily a person can recognize and label their emotional responses to life’s roller coaster, the better able they are to address those feelings while experiencing them, so as not to be overwhelmed by them.

Another major factor eroding the mental health of the population is that the world is exponentially more complicated today than even 30 years ago. There are more reasons for kids and adults to be anxious and overwhelmed. Climate change is an existential threat. There are school shootings. The governance of the country has been openly roiling for close to a decade, with a new level of uncertainty accompanying elections.

You can’t talk about mental health today without talking about technology. Digital technology was becoming available globally just as the concept of EI was introduced. When you are staring at a screen much of the day versus interacting with a live person, you miss out on important emotional currency.

At the same time, algorithms are keeping people in a state of emotional upheaval. Social media in particular have deliberately built into their platforms mechanisms to activate the nervous system . Research has shown a correlation between anxiety and time spent on social media.

It’s not impossible to course correct. The world has moved beyond the Freudian idea that emotions sit in a cauldron of the unconscious , driving us to do things we don’t want to do. We have an emotion system for a reason. Emotions are helpful. Happiness tells you that you are achieving your goals. Fear alerts you to prepare for danger. All emotions are data and information. There are skills that can help people use them wisely, but every one of them has to be learned.

Marc Brackett, Ph.D ., is the founding director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and a professor in the Child Study Center. Robin Stern, Ph.D ., is the associate director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and an associate research scientist in the Child Study Center.

Why You Should Expand Your Emotional Vocabulary

Emotional granularity, or the ability to precisely name a wide range of emotions, plays a critical role in psychological wellness. Here’s how to cultivate it.

By Katrina McCoy, Ph.D.

We’ve all felt it—the nagging of an unpleasant emotion that is difficult to name or explain. Maybe you chalk it up to feeling “off” or “upset.”

But finding more precise labels for our emotions can help us feel better—both in the moment and over the long term. This precise labeling of emotions is called emotional granularity.

The Benefits of Emotional Granularity Emotional granularity is a skill, and researchers have demonstrated its important role in psychological well-being for decades. For example, a 2015 review of the research on emotional granularity found that folks who could differentiate their emotions while experiencing intense distress were less likely to engage in potentially harmful coping strategies, such as binge drinking, lashing out at others, and hurting themselves.

This means a person who describes feeling “angry,” “disappointed,” “sad,” or “ashamed” in the context of, let’s say, a conflict with a friend is likely to cope more effectively with those feelings than a person who uses vague descriptions, such as feeling “bad” or “upset.”

Impressively, the benefits of emotional granularity extend beyond any specific moment of distress. That same 2015 review found that people who describe and label their emotions more specifically have less severe episodes of anxiety and depression .

How Emotional Granularity Works How does using more specific language to describe unpleasant experiences reduce distress? A straightforward answer is this: The more accurately we can describe our emotional experience and the context in which the experience is happening, the more information we have to decide what will help. Neuroscience even suggests that labeling our emotions can decrease activity in brain areas associated with negative emotions.

Yet a more nuanced answer requires us to take a step back and look at the components from which our emotions are made. Start by answering a simple question: What are emotions?

Neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett succinctly sums up emotion as “your brain’s creation of what your bodily sensations mean about what is going on around you in the world.” Imagine this: Your heart is racing, your palms are sweaty, and you’re short of breath. If you are walking down a dark street alone at night, you might label your experience as fear . Now, imagine you are experiencing those same physical sensations while enjoying a candle-lit meal with a romantic interest. In that case, you might label the experience as attraction .

Thus, the same constellation of physiologic experiences organizes us around different actions depending on the context. In the first example, our fear functions to keep us safe and readies us to fight, flee, or freeze. In the second example, our attraction functions to focus our attention on our love interest, thus increasing our connectedness (and therefore regulation and well-being).

Importantly, our personal histories determine what predictions and needs we might have in any specific context. Throughout our lives, we collect diverse emotional experiences, typically first labeled by our early caregivers, which help us categorize and form our emotion concepts—the diverse collection of physical sensations, thoughts, and situations we learn to associate with a particular emotion.

Our concept of anger, for example, may include a flushed face, muscle tension, and being cut off in traffic. Our concept of anger may also have a racing heart, the urge to speak loudly, and thoughts of being taken for granted by a relationship partner. These categorizations help us to navigate our physiology in the context of the specific situation, to figure out if we should take a breath and focus on a podcast—if, say, we were cut off in traffic—or use communication skills to improve our relationship if we’re feeling taken for granted.

More precise language leads to more tailored responses (“mild annoyance” cues letting it go, whereas “outrage” cues advocating for change). Not only that, more precise language can allow us to incorporate details that create a different emotion category altogether. For example, if you home in to notice and describe hunger during a relational conflict, you may save yourself from experiencing anger.

How to Strengthen Emotional Granularity Precisely labeling your emotional experiences, then, is likely to improve your quality of life. But how should you go about developing this skill? Experts recommend creating new emotion concepts and examining our existing concepts more closely.

In her book How Emotions Are Made , Feldman Barrett suggests that one of the easiest ways to build new emotion concepts is to learn new words. She also suggests we can add to our emotion concepts by being “collector(s) of experiences” through perspective-taking (e.g., reading books, watching movies) and trying new things.

To start, explore the emotion words collected in the list below. Find one or two words you don’t typically use and ask yourself if they describe your recent experiences. Perhaps when you next notice that nagging, nameless emotion, you will skim this list of emotion words to find the ones that resonate.

Katrina McCoy, Ph.D ., is a psychotherapist, educator, consultant, and scholar with a private practice based in Westchester, New York.

......................................................

Name That Feeling

Happy, sad, and angry are useful terms but aren’t enough to describe the full range of our emotional experience. Explore this list to identify emotion words that better capture your feelings.

Anger Rage Indignation Vengefulness Wrath

Sadness Despair Disappointment Sorrow Grief

Happiness Joy Contentment Pleasure Exhilaration

Fear Anxiety Dread Terror Apprehension

You’ve Named Your Emotions—What Now?

Being aware of your emotions isn’t enough; you also have to manage them. These four strategies can help you master this second pillar of emotional intelligence.

By Michael Wiederman, Ph.D.

Awareness of your and others’ emotions is the foundation on which emotional intelligence rests. But awareness, in itself, is not enough. Here, let’s consider four ways you can develop another critical pillar of EI: emotional self- management .

1. Pause to mentally distance. In an emotionally charged situation, the path of least resistance is to follow your feelings. Instead, take conscious control of your attention and shift from allowing your limbic system to guide your behavior (reacting) to engaging your cerebral cortex (responding). Doing so lets you choose how to act.

Of course, mentally stepping out of a whirlwind of emotion is easier said than done. As a first step, it can be helpful to note the particular physical experiences that accompany troublesome emotions. Then, when a situation arises that triggers those physical responses, take a moment to mentally step out of your immediate experience. Asking yourself a question, or imagining what you might look like to others, often does the trick. At that point, although still physiologically keyed up, you’ll be able to more calmly consider the best course of action. In other words, you won’t be just reacting; you’ll be choosing how to act.

2. Take control of your self-talk . We’re frequently unaware of how much chatter goes on in the background of our minds. Such self-talk might not be in fully articulated phrases but just flashes of thought about what’s happening, what should be, or how right we are and how wrong someone else is.

Becoming aware of your self-talk is an important skill because it is those background beliefs that fuel our emotional responses. To genuinely defuse a strong negative emotion requires examining the underlying belief and how accurate or useful it is.

You may be tempted to justify the belief (This situation should not be so difficult!) but, instead, recognize that the situation is the way it is, no matter how much you wish otherwise. Ask yourself: How useful is it to me to keep clinging to this belief? You might also flex your conscious awareness to focus on asking: Over what parts of this situation do I have some degree of control? What do I need to do to exercise that control?

3. Enlist partners. Ask others you trust to help you recognize when your emotions seem to be getting the best of you. Agree on a gesture or word to serve as a signal that your trusted individual wonders whether you’re riding the led-by-your-limbic-system train.

Of course, they may get it wrong—and even when they’re right, it can feel irritating to be called out when you’re already keyed up. But instead of responding defensively, focus on the fact that this person is offering a gift—one that you asked for!—and is taking a risk. Respond with grace and gratitude .

4. Cultivate curiosity. Our brains are wired to draw conclusions quickly. These judgments are not necessarily accurate but often feel as if they are, and they are responsible for many of our negative emotional states. Working to be more curious about other peoples’ experiences, including their interpretation of events and their own motives for their behavior, helps inhibit such hasty judgments.

To be able to apply the brakes on your strong emotional reaction when triggered, practicing curiosity in situations that are not nearly as charged is a good way to build that skill for when it’s most important. A side benefit of cultivating curiosity is that it also promotes a sense of empathy and deeper connection with those you better try to understand.

A common thread across these strategies is the ability to recognize an emotional storm and decide to shift to conscious intentionality rather than reaction. Like any skill, it requires practice, and there will be lapses along the way. However, the benefits, both professional and personal, can be immense. How might your life be enhanced by greater emotional self-control ?

Michael Wiederman, Ph.D ., is a former clinical psychology professor who now works full-time applying psychology to the workplace.

Emotional Intelligence Is a Skill Set

Peter Salovey, a co-author of the original paper on EI, clears up some widespread misunderstandings.

In the late 1980s, John Mayer and I noticed that there were separate groups studying facial expressions, emotion vocabulary, and emotion self-management, all independently. We thought there was a framework under which all those topics fit—an arsenal of skills that describe abilities having to do with the emotions. We called it “emotional intelligence.”

The skills form four basic clusters. The first is identifying emotions in yourself and in others, through verbal and nonverbal means.

A second is understanding how emotion vocabulary gets used, how emotions transition over time, what the consequences are of an emotional arousal—for example, why shame often leads to anger, why jealousy often contains a component of envy.

A third area is emotion management, which includes managing not only one’s own emotions but also the emotions of others.

The fourth is the use of emotions, such as in cognitive activities like solving a problem and making a decision.

Once we had a way to measure emotional intelligence, we realized that we had to demonstrate that EI matters above and beyond standard features of personality , such as the Big Five personality traits ( openness to experience , conscientiousness , agreeableness , neuroticism , and extraversion ) and beyond traditional intelligence as measured by an IQ test. Only if emotional intelligence still accounted for variance in important outcomes could we claim that it has validity.

Over the next 20 years, we showed that, in fact, it did predict outcomes in school, at work, and in relationships. It predicted who would receive positive performance evaluations and get recommended for raises, who would be viewed as contributing the most creative ideas and leading a group. It correlated with aspects of friendship and positive social relations—less aggression , less use of illicit substances, more friends, greater satisfaction in relationships with friends. In lab experiments, EI predicted subjects’ behavior with a stranger: Those with EI were more able to elicit information, and strangers rated the interaction as more pleasant. People viewing films of the interactions rated those with EI as more empathic .

There has been a lot of playing with the construct of emotional intelligence—for example, regarding the features as traits. But that does not yield any unique information. I think it’s best to stick to a definition of EI based on skills and abilities.

Peter Salovey, Ph.D ., is the president of Yale University.

Submit your response to this story to [email protected] .

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of this issue.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 June 2021

Emotional intelligence: predictor of employees’ wellbeing, quality of patient care, and psychological empowerment

- Leila Karimi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2364-504X 1 ,

- Sandra G. Leggat 1 ,

- Timothy Bartram 2 ,

- Leila Afshari 3 ,

- Sarah Sarkeshik 1 &

- Tengiz Verulava 4

BMC Psychology volume 9 , Article number: 93 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

18 Citations

83 Altmetric

Metrics details

The study explored the role of emotional intelligence (EI) on employees’ perceived wellbeing and empowerment, as well as their performance, by measuring their quality of care.

The baseline data for the present project was collected from 78 staff of a Victorian aged care organization in Australia. Self-administered surveys were used to assess participants’ emotional intelligence, general well-being, psychological empowerment, quality of care, and demographic characteristics. The model fit was assessed using structural equation modelling by AMOS (v 24) software.

The evaluated model confirmed that emotional intelligence predicts the employees’ psychological empowerment, wellbeing, and quality of care in a statistically significant way.

Conclusions

The current research indicates that employees with higher EI will more likely deliver a better quality of patient care. Present research extends the current knowledge of the psychological empowerment and wellbeing of employees with a particular focus on emotional intelligence as an antecedent in an under-investigated setting like aged care setting in Australia.

Peer Review reports

Today's organisations are under increasing pressure to expand the quality of work and ability to compete in the workplace that is continuously changing. These changes involve increased dependency on social skills and new technologies, continuous competency development, risk-taking, networking, and innovation. They also include changes in organisational structure and relationships, such as reduced hierarchies, blurred boundaries, moves to teams as basic building blocks, and increased complexity of work. As the current pandemic has shown, they also embrace profound and fast changes to the way we work in the face of crises and organisations are looking at new strategies to promote such qualities as wellbeing, psychological empowerment and work engagement which are antecedents of job satisfaction and quality of patient care [ 1 , 2 , 3 ].

There is strong evidence that EI is an important factor in improving work performance [ 4 ]. Research indicates that higher EI leads to enhanced psychological wellbeing and higher rates of positive emotional states [ 5 , 6 , 7 ], and that emotional intelligence training can develop meaningfulness at work and happiness [ 8 , 9 ]. In a meta-analysis, O'Boyle et al. [ 10 ] found overall validity for three streams of EI research (ability measures, self- and peer-report measures, and mixed models) predicting job performance equally well. EI also influences the success with which employees interact with colleagues, the strategies they use to manage conflict and stress, and positively contributes to several aspects of workplace performance [ 11 ].

Researching the relationship between EI and job satisfaction among nurses, Gong et al. [ 12 ] examined the mediating effect of psychological empowerment and work engagement in this association. Using structural equation modelling, they found that high trait EI may improve occupational wellbeing through the chain-mediating effects of these two constructs. A 2017 meta-analysis of EI and work attitudes has found that all three types of EI are significantly related to job satisfaction [ 13 ]. The results indicate that workers with higher EI have higher job satisfaction, higher organizational commitment, and are less likely to change jobs. Another recent study has found statistically significant positive relationships between EI, empowering leadership, psychological empowerment and work engagement [ 14 ]. This finding suggests that EI training of health workers to improve psychological empowerment and work engagement could help their organisations to improve their relationships with patients, provide better care, and reduce staff turnover. Emotional intelligence may be most important in the service sector and in other jobs where employees interact with customers. Several studies found a positive association between the EI of nurses and service quality and patients' compliance with care [ 15 , 16 , 17 ].

There is evidence that communication effectiveness and job satisfaction of the employees are related to their managers' EI [ 18 ]. Research shows that leaders who build effective interpersonal relationships with those in lower rank are using EI to lead individuals to work more effectively and with increased overall job satisfaction [ 19 , 20 ]. Udod et al. [ 21 ] found that leaders who use EI to build interpersonal relationships with their subordinates achieve higher overall job satisfaction and better work effectiveness among those employees. These positive changes are strongly influenced by the leaders who value and respect their employee’s opinions, abilities, personal emotions, and character. Increased empowerment was directly related to the support and level of autonomy given by the leader and a work environment allowing career growth and development [ 21 ].

There has been much interest in empowerment in the workplace for a variety of reasons. Studies found that empowering subordinates contributes to managerial and organisational effectiveness. There is a significant relationship between psychological empowerment and work engagement. Alotaibi et al. [ 14 ] investigated the role of EI and empowering leadership (EL) in improving psychological empowerment and work engagement. They found significant positive relationships between EI, EL, psychological empowerment and work engagement, suggesting that EI is a good predictor of EL and psychological empowerment, while EL supports work engagement.

Staff empowerment is linked to work behaviours, attitudes, and performance. It tends to have a direct effect on performance and indirect effects through its influence on job satisfaction and innovativeness [ 22 ]. In healthcare, employee empowerment denotes the level to which caregivers have the authority to make decisions, such as evaluating the patient condition and determining the most suitable treatment. A review of studies exploring the effect of structural empowerment of nurses on quality outcomes in hospitals found that there are positive associations between the structural empowerment of nurses and the quality of outcomes, such as patient safety, work effectiveness, efficiency, and patient‐centeredness of patient care in hospitals [ 23 ].

Quality of healthcare can be defined in many ways. The Institute of Medicine defines quality as the "degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” [ 24 ]. A more recent study defined quality of healthcare, using various healthcare stakeholder perceptions and expectations, as “consistently delighting the patient by providing efficacious, effective and efficient healthcare services according to the latest clinical guidelines and standards, which meet the patient's needs and satisfies providers” [ 25 ].

Many nursing studies have shown an association between EI and nurses' quality of care. A 2017 study examining the relationship between patient satisfaction and EI skills of nurses found a strong correlation between the satisfaction scores and emphatic concern, utilization of emotions, and emotional awareness subheadings of the patients [ 26 ]. A 2018 study, exploring the role of EI in engagement in nurses, found that nurses with higher levels of EI also scored higher in engagement. The greatest predictor of engagement was the interpersonal factor [ 27 ]. A study investigating emotional labour among Australian community nurses found that emotional labour and EI predicts wellbeing as well as job-stress [ 28 ]. With the current shortage in the nursing workforce, effective EI training may provide the key to keeping nurses in their jobs while helping them reduce job-stress and burnout levels. Emotional intelligence also seems to correlate highly with wellbeing in nurses, has a positive correlation with work performance and the ability to positively affect patient safety [ 29 , 30 , 31 ]. Today, EI is one of the most sought-after skills in the workplace. When it comes to healthcare workers and nurses, increased EI may save lives, not to mention relieve stress.

The model fit was in this study was assessed using structural equation modelling (SEM). SEM has been used successfully in research involving EI and nurses. For example, a 2016 study used SEM to analyse the goodness of fit of the hypothetical model of nurses' turnover intention. The results suggest that increasing EI in nurses might significantly decrease nurses' turnover intention by reducing the effect of emotional labour on burnout [ 32 ]. Another study used SEM to examine the mediatory role of positive and negative affect at work. The researchers found that these mediate the relationship between EI and job satisfaction with positive affect exerting a stronger influence [ 33 ].

The present research project investigated the importance of EI as an antecedent to wellbeing, psychological empowerment and quality of care. The research is one of the few studies in Australia in a much under-researched area of aged care setting. It contributes to international literature by examining the EI link with the three constructs. Thus, it was hypothesised that:

Higher emotional intelligence is a predictor of better wellbeing,

Higher emotional intelligence is a predictor of psychological empowerment,

Higher emotional intelligence leads to better quality of patient care among aged care staff.

This study aimed to further explore the role of EI on psychological empowerment and the quality of care and wellbeing in an aged care setting. The current research used a sample of 78 participants of a Victorian aged care facility. The workers from all levels of the organisation having contact with the residents were included, including personal care workers (PCW), nurses, and lifestyle, food and safety staff.

The demographic characteristic of the staff are detailed in Table 1 . The staffs' age on average was 45.7 years, and they had almost 12 years of experience of working in their position, with 25 working hours per week. Majority of the staff were female (82%), nursing and personal care workers (61%).

General wellbeing

The General Well-being Questionnaire (GWBQ), developed by Cox et al. [ 34 ]. The GWBQ is a scale with 24 questions that assess general malaise frequency on a 5-Likert response where a high score is indicating lower wellbeing.

- Psychological empowerment

Psychological empowerment Scale [ 35 ] for evaluating the perceived empowerment on a 5-likert response using 12 statements, where higher score represent higher level of empowerment.

Patient satisfaction

Patient Satisfaction with Nursing Care Quality Questionnaire (PSNCQQ) [ 36 ] was used to measure the quality of patient care. The terminology was modified slightly to make it suitable for use in an aged care population. Seventeen items were adapted (two items related to the discharge, and after-discharge coordination were removed as were not relevant to the aged care setting); higher scores refer to a higher quality of patient care.

Emotional quotient inventory (EQ-i 2.0®)

The EQ-i 2.0 used in this study which assesses the social and emotional elements [ 37 ]. Sing 133 questions on a Likert response of 1 (never/rarely) to 5 (always/almost always). The EQ-i 2.0 is a self-report measure to measure constructs related to EI. A total score of the EQ-I 2.0 was used in this study to measure emotional intelligence (EI).

Validity and reliability

All the surveys used in this study are pre-validated scales. However, the reliability of the scales was also assessed in this study. The study scales showed excellent reliability: The General Wellbeing Questionnaire (GWBQ) (α = 0.92) and Psychological Empowerment (α = 0.92), PSNCQQ (α = 0.91).

Ethical considerations

The Human Research Ethics Committee of the participating organisation was obtained for this study.

Data analysis

Structural equation modelling (SEM) by AMOS (v 24) software was used to assess the model fit. Chi-square as a goodness of fit statistics provides a good description of the data. A non-significant chi-square means the proposed hypothesis of model fit is supported, and the null model (no relationship between constructs) is rejected. However, chi-square is highly influenced by sample size; therefore, a more robust measure of the relative chi-square (CMIN/DF) is used for model fit evaluation. Besides, other fit indices are proposed, including the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). RMSEA is the suggested fit indices representing absolute fit; CFI is recommended for model comparison. A combination of these fit indices, such as CMIN/DF, RMSEA and CFI, are commonly used in research. The AIC is another measure of fit that was used for this study. The smaller value of AIC indicates a superior model fit [ 38 ].

Normality and bootstrapping approach

The normal distribution of data and outliers were assessed before proceeding with the model fit evaluation. Although the data were within the normal threshold at univariate level (where kurtosis and skewness were smaller than 7 and 3 in order), multivariate critical ratio and kurtosis were greater than 1.96 and 5 in order, indicating violation of the normality assumptions. Hence the bootstrapping procedure was implemented due to violation of normality and relatively small sample size (n = 78), to assess the parameter estimates. The number of bootstrapping subsamples needs to be high enough to deliver valid results. They must be higher than the number of valid observations in the original dataset (in this study, higher than 78). As a general rule, 500 bootstrap samples are recommended in SEM [ 39 ]. In this study, the bootstrapping procedure and the Bollen-Stine bootstrap procedure were implemented to test the proposed model.

Model evaluation

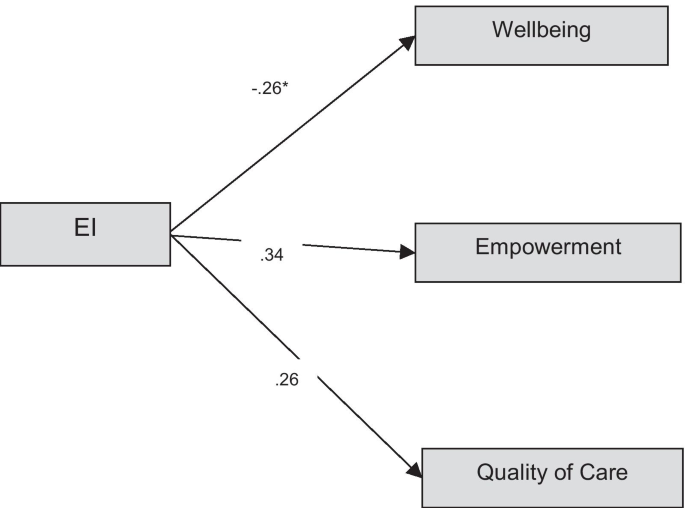

Figure 1 presents the model used in this study and evaluated by SEM. The model fit evaluation indicated χ 2 /df less than 3 which represents great goodness of model fit (χ 2 /df (19) = 1.39). The fit indices in Table 2 also show acceptable fit for the model (CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.07 (0.05, 0.06). RMSEA less than 0.08 and 0.05 & CFI of greater than 0.90 and 0.95 were considered as marginal and good fit respectively for this study. AIC for the proposed model was significantly smaller which indicated a better model fit (AIC = 76.53). The standardised regression weights were all significant (p < 0.05) and presented in Table 3.

Path coefficients of the proposed model. Note : *higher score in wellbeing represents lower wellbeing and high illness

The paths of factor loadings of emotional intelligence to wellbeing, quality of care and psychological empowerment were all significant (p < 0.05). Figure 1 presents the standardised factor loadings of the model. Psychological empowerment deemed to be significantly related to EI skills (β = 0.34). Quality of care was correlated positively with EI skills where higher EI skills were associated with a higher level of quality of care (β = 0.26). Wellbeing (ill health) was negatively associated with EI skills where higher EI associated with the lower level of illness (β = 0.26).

The bootstrapping procedure showed relatively stable parameter estimates, demonstrating the validity of the results. The Bollen-Stine approach showed that the evaluated model was not significantly changed from the model resulting from 500 bootstrapping samples (p = 0.13).

The present project, aimed to explore the role of EI with wellbeing, quality of patient care and psychological empowerment among a group of Australian aged care employees. The evaluated model confirmed that emotional intelligence is related to all three variables in a statistically significant but moderate way. Both psychological empowerment and quality of care were significantly related to EI skills. Wellbeing (ill health) was significantly predicted by EI skills.

This study shows that those with a high level of EI are possibly more psychologically empowered.

According to Spreitzer [ 35 ] and Kanter [ 40 ], psychologically empowered employees are driven by intrinsic motivation, and they are more likely to perform effectively [ 22 , 41 ]. However, the results need to be treated with caution because SEM-based analyses reported here are estimates based on cross-sectional data; they do not provide sufficient evidence to demonstrate the existence of a causal relationship.

The results also suggest that if EI is related to employees' wellbeing, empowerment and quality of care, then implementation of interventions for employees in the healthcare sector to learn and practice EI skills seem to be valuable for employee empowerment and consequently for enhancing employees' performance. This finding has been substantiated by an integrative literature review by Kline et al. [ 42 ] who found that EI is central to nursing practice and should be included in nursing education. Evidence shows that EI impacts on ethical decision-making, critical thinking, evidence and knowledge use in practice.

The study also provided evidence for a significant association between EI and wellbeing of employees, demonstrating that staff with higher EI are more likely to have better emotional and psychological wellness. This finding is in line with recent studies such as Karimi et al. [ 28 ], [ 43 ], that reported a significant relationship between EI and wellbeing among nurses and aged care staff.

Finally, the findings indicate that the employees' EI is related to the quality of the care for the aged care residents. Specifically, the care provided by emotionally intelligent employees is more likely to result in desired outcomes for the residents and consequently in an increased level of residents' satisfaction with the quality of patient care.

Our study extends the current knowledge of psychological empowerment and wellbeing of employees with a particular focus on emotional intelligence as an antecedent. Our findings demonstrate that employees' emotional intelligence not only relates to the residents' satisfaction with the quality of patient care but also seems to be associated with employees' psychological empowerment and wellbeing. This indicates that EI is an important skill to be learnt in order to generate the desired outcomes for two main stakeholders in the aged care sector: the residents and the employees.

Although bootstrapping procedure used to report more stable and valid results, the relatively small sample size and lack of previous studies on Australian aged care made the generalizability of the findings limited. Future studies on aged care setting with a bigger sample size is recommended. In addition, longitudinal studies assessing the EI training skills on employees' mental health and performance is strongly recommended in order to shed more light in this area.

The aged care industry is facing significant challenges with difficulties in staff retention, recruitment, and most importantly, in the quality of patient care. The current study highlighted the need for paying attention to non-clinical skills such as EI (in addition to clinical) for quality care improvement in the aged care industry as well as improving psychological empowerment and wellbeing. The findings suggest that EI contributes to employee empowerment and quality of patient care and adds valuable skills that are important in working with aged care residents and other stakeholders.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Emotional intelligence

The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

Comparative fit index

General Well-being Questionnaire

Emotional quotient inventory

Moura D, Orgambídez A, Jesus S. Psychological empowerment and work engagement as predictors of work satisfaction: a sample of hotel employees. J Spat Organ Dyn. 2015;III:125–34.

Google Scholar

Bartram T, Karimi L, Leggat SG, Stanton P. Social identification: linking high performance work systems, psychological empowerment and patient care. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2014;25(17):2401–19.

Article Google Scholar

Scheepers RA, Boerebach BCM, Arah OA, Heineman MJ, Lombarts KMJMH. A systematic review of the impact of physicians’ occupational well-being on the quality of patient care. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(6):683–98.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Karimi L, Leggat SG, Bartram T, Rada J. The effects of emotional intelligence training on the job performance of Australian aged care workers. Health Care Manage Rev. 2020;45(1):41–51.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lin DT, Liebert CA, Tran J, Lau JN, Salles A. Emotional intelligence as a predictor of resident well-being. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(2):352–8.

Guerra-Bustamante J, León-Del-Barco B, Yuste-Tosina R, López-Ramos VM, Mendo-Lázaro S. Emotional intelligence and psychological well-being in adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(10):1720.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cejudo J, Rodrigo-Ruiz D, López-Delgado ML, Losada L. Emotional intelligence and its relationship with levels of social anxiety and stress in adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):56.

Thory K. Developing meaningfulness at work through emotional intelligence training. Int J Train Dev. 2016;20(1):58–77.

Callea A, De Rosa D, Ferri G, Lipari F, Costanzi M. Are more intelligent people happier? Emotional intelligence as mediator between need for relatedness, happiness and flourishing. Sustainability. 2019;11(4):56.

O’Boyle EH, Humphrey RH, Pollack JM, Hawver TH, Story PA. The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: a meta-analysis. J Organ Behav. 2010;32(5):788–818.

Brackett MA, Rivers SE, Salovey P. Emotional intelligence: implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2011;5(1):88–103.

Gong Y, Wu Y, Huang P, Yan X, Luo Z. Psychological empowerment and work engagement as mediating roles between trait emotional intelligence and job satisfaction. Front Psychol. 2020;11(232):56.

Miao C, Humphrey RH, Qian S. A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence and work attitudes. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2017;90(2):177–202.

Alotaibi SM, Amin M, Winterton J. Does emotional intelligence and empowering leadership affect psychological empowerment and work engagement? Leadersh Org Dev J. 2020;41(8):971–91.

Adams KL, Iseler JI. The relationship of bedside nurses’ emotional intelligence with quality of care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014;29(2):174–81.

Warren B. Healthcare Emotional Intelligence: Its role in patient outcomes and organizational success. 2014. http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/healthcare-emotional-intelligence-its-role-in-patient-outcomes-and-organizational-success.html .

Ezzatabadi MR, Bahrami MA, Hadizadeh F, Arab M, Nasiri S, Amiresmaili M, et al. Nurses’ emotional intelligence impact on the quality of hospital services. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14(12):758–63.

Jorfi H, Yacco HFB, Shah IM. Role of gender in emotional intelligence: relationship among emotional intelligence, communication effectiveness and job satisfaction. Int J Manag. 2012;29(4):590.

Cummings G. Investing relational energy: the hallmark of resonant leadership. Nurs Leadersh Tor Ont. 2004;17(4):76–87.

Heckemann B, Schols JM, Halfens RJ. A reflective framework to foster emotionally intelligent leadership in nursing. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23(6):744–53.

Udod SA, Hammond-Collins K, Jenkins M. Dynamics of emotional intelligence and empowerment: the perspectives of middle managers. SAGE Open. 2020;10(2):2158244020919508.

Fernandez S, Moldogaziev T. Employee empowerment, employee attitudes, and performance: testing a causal model. Public Adm Rev. 2013;73(3):490–506.

Goedhart NS, van Oostveen CJ, Vermeulen H. The effect of structural empowerment of nurses on quality outcomes in hospitals: a scoping review. J Nurs Manag. 2017;25(3):194–206.

Shaneyfelt TM. Building bridges to quality. JAMA. 2001;286(20):2600–1.

Mohammad MA. Healthcare service quality: towards a broad definition. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2013;26(3):203–19.

Oyur CG. The relationship between patient satisfaction and emotional intelligence skills of nurses working in surgical clinics. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1363–8.

Pérez-Fuentes MDC, Molero Jurado MDM, Gázquez Linares JJ, Oropesa Ruiz NF. The role of emotional intelligence in engagement in nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9):1915.

PubMed Central Google Scholar

Karimi L, Leggat SG, Donohue L, Farrell G, Couper GE. Emotional rescue: the role of emotional intelligence and emotional labour on well-being and job-stress among community nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(1):176–86.

Codier E. Emotional intelligence: why walking the talk transforms nursing care. Am Nurse Today. 2012;7(4):56.

Codier E, Codier DD. Could emotional intelligence make patients safer? Am J Nurs. 2017;117(7):56.

Ann Bernasyl EV. The relationship between nurses’ emotional intelligence and their perceived work performance. Univ Visayas J Res. 2015;9(1):56.

Hong E, Lee YS. The mediating effect of emotional intelligence between emotional labour, job stress, burnout and nurses’ turnover intention. Int J Nurs Pract. 2016;22(6):625–32.

Kafetsios K, Zampetakis LA. Emotional intelligence and job satisfaction: testing the mediatory role of positive and negative affect at work. Pers Individ Differ. 2008;44(3):712–22.

Cox T, Thirlaway M, Gotts G, Cox S. The nature and assessment of general well-being. J Psychosom Res. 1983;27(5):353–9.

Spreitzer GM. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad Manag J. 1995;38(5):1442–65.

Laschinger HKS. Job and career satisfaction and turnover intentions of newly graduated nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2012;20:472–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01293.x .

Statistical Solutions. Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i) 2.0 2015. http://www.statisticssolutions.com/emotional-quotient-inventory-eq-i-2-0/ .

Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Petrov BN, Csaki BF, editors. Second international symposium on information theory. Budapest: Academiai Kiado; 1973. p. 267–81.

Cheung GW, Lau RS. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organ Res Methods. 2007;11(2):296–325.

Kanter R. Power failure in management circuits. Harv Bus Rev. 1979;57:65–75.

Kirkman BL, Rosen B. A model of work team empowerment. In: Woodman RW, Pasmore WA, editors. Research in organizational change and development, vol. 10. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1997. p. 131–67.

Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press; 1998.

Karimi L, Bartram T, Leggat S. The effects of emotional intelligence training on the job performance of Australian aged care workers. Health Care Manag Rev. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000200 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The researchers acknowledge the aged care staff and residents and their next of kin who participated in this research and kindly shared their time and experience.

Part of the project was funded by the Royal Freemasons Aged Care (3.1062). The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Plenty Rd, Bundoora, VIC, Australia

Leila Karimi, Sandra G. Leggat & Sarah Sarkeshik

School of Management, College of Business, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

Timothy Bartram

School of Business, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

Leila Afshari

School of Medicine and Healthcare Management, Caucasus University, Tbilisi, Georgia

Tengiz Verulava

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the study and development of the paper. All authors have agreed on the final version of the paper and either had: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design (TB, SL, LK), acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data (LK, LA, SS, TV) and/or (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content (SL, TB, LK, TV, LA, SS). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Leila Karimi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The Human Research Ethics Committee of the participating organisation was obtained for this study. Participation in the study was voluntary and written consent was obtained for each participant.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Karimi, L., Leggat, S.G., Bartram, T. et al. Emotional intelligence: predictor of employees’ wellbeing, quality of patient care, and psychological empowerment. BMC Psychol 9 , 93 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00593-8

Download citation

Received : 17 May 2020

Accepted : 14 May 2021

Published : 04 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00593-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Quality of patient care

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Can emotional intelligence be improved? A randomized experimental study of a business-oriented EI training program for senior managers

Raquel gilar-corbi.

Developmental and Educational Psychology Department, University of Alicante, San Vicente del Raspeig, Alicante, Spain

Teresa Pozo-Rico

Bárbara sánchez, juan-luís castejón, associated data.

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Purpose: This article presents the results of a training program in emotional intelligence. Design/methodology/approach: Emotional Intelligence (EI) involves two important competencies: (1) the ability to recognize feelings and emotions in oneself and others, and (2) the ability to use that information to resolve conflicts and problems to improve interactions with others. We provided a 30-hour Training Course on Emotional Intelligence (TCEI) for 54 senior managers of a private company. A pretest-posttest design with a control group was adopted. Findings: EI assessed using mixed and ability-based measures can be improved after training. Originality/value: The study’s results revealed that EI can be improved within business environments. Results and implications of including EI training in professional development plans for private organizations are discussed.

Introduction

This research study focused on EI training in business environments. Accordingly, the aim of the study was to examine the effectiveness of an original EI training program in improving the EI of senior managers. In this article, we delineate the principles and methodology of an EI training program that was conducted to improve the EI of senior managers of a private company The article begins with a brief introduction to the main models of EI that are embedded with the existing scientific literature. This is followed by a description of the EI training program that was conducted in the present study and presentation of results about its effectiveness in improving EI. Finally, the present findings are discussed in relation to the existing empirical literature, and the limitations and conclusions of the present study are articulated.

Defining EI

Various models of emotional intelligence (EI) have been proposed. The existing scientific literature offers three main models of EI: mixed, ability, and trait models. First, mixed models conceptualize EI as a combination of emotional skills and personality dimensions such as assertiveness and optimism [ 1 , 2 ]. Thus, according to the Bar-On model [ 3 ], emotional-social intelligence (ESI) is a multifactorial set of competencies, skills, and facilitators that determine how people express and understand themselves, understand and relate to others, and respond to daily situations The construct of ESI consists of 10 key components (i.e., self-regard, interpersonal relationships, impulse control, problem solving, emotional self-awareness, flexibility, reality-testing, stress tolerance, assertiveness, and empathy) and five facilitators (optimism, self-actualization, happiness, independence, and social responsibility). Emotionally and socially intelligent people accept and understand their emotions; they are also capable of expressing themselves assertively, being empathetic, cooperating with and relating to others in an appropriate manner, managing stressful situations and changes successfully, solving personal and interpersonal problems effectively, and having an optimistic perspective toward life. Second, ability models of EI focus on the processing of information and related abilities [ 3 ]. Accordingly, Mayer and Salovey [ 4 ] have conceptualized EI as a type of social intelligence that entails the ability to manage and understand one’s own and others’ emotions. Indeed, this implies that EI also entails the ability to use emotional information to manage thoughts and actions in an adaptive manner [ 5 ]. Third, the trait EI approach understands EI as emotion-related information [ 6 ]. According to trait models, EI refers to self-perceptions and dispositions that can be incorporated into fundamental taxonomies of personality. Therefore, according to Petrides and Furnham [ 7 ], trait EI is partially determined by several dimensions of personality and can be situated within the lower levels of personality hierarchies. However, it is a distinct construct that can be differentiated from other personality constructs. In addition, the construct of trait EI includes various personality dispositions as well as the self-perceived aspects of social intelligence, personal intelligence, and ability EI. The following facets are subsumed by the construct of trait EI: adaptability, assertiveness, emotion perception (self and others), emotion expression, management (others), and regulation, impulsiveness (low), relationships, self-esteem, self-motivation, social awareness, stress management, trait empathy, happiness, and optimism [ 7 ]. Finally, as Hodzic et al. [ 8 ] have indicated, most existing definitions of EI permit us to draw the conclusion that EI is a measurable individual characteristic that refers to a way of experiencing and processing emotions and emotional information. It is noteworthy that these models are not mutually exclusive [ 7 ].

Effects of EI on different outcomes

EI has been found to be related to workplace performance in highly demanding work environments (see e.g. [ 9 ]). Consequently, companies, entities, and organizations tend to recognize the importance of EI, promote it on a daily basis to facilitate career growth, and recruit those who possess this ability. [ 10 ].

With regard to research that has examined the EI-performance link, Van Rooy and Viswesvaran [ 11 ] conducted a metanalytic study to examine the predictive power of EI in the workplace. They found that approximately 5% of the variance in workplace performance was explained by EI, and this percentage is adequately significant to increase savings and promote improvements within organizations. In addition, the authors concluded that further in-depth investigations are needed to comprehensively understand the construct of EI.

However, the EI-performance link must be interpreted with caution. Specifically, Joseph and Newman [ 12 ] examined emotional competence in the workplace and found that EI predicts performance among those with high emotional labor jobs but not their counterparts with low emotional labor jobs. In addition, they indicated that further research is required to delineate the relationship between EI and actual job performance, gender and race differences in EI, and the utility of different types of EI measures that are based on ability or mixed models in training and selection. Accordingly, Pérez-González and Qualter [ 13 ] have underscored the need for emotional education. Further, Brasseur et al. [ 14 ] found that better job performance is related to EI, especially among those with jobs for which interpersonal contact is very important.

It is noteworthy that EI is positively related to job satisfaction. Accordingly, Chiva and Alegre [ 15 ] found that there was an indirect positive relationship between self-reported EI (i.e., as per mixed models) and job satisfaction. A total of 157 workers from several companies participated in this study. These findings suggest that people with higher levels of EI are more satisfied with their jobs and demonstrate a greater capacity for learning than their counterparts with lower levels of EI.

Similarly, Sener, Demirel, and Sarlak [ 16 ] adopted a mixed model of EI and examine its effect on job satisfaction. They found that individuals with strong emotional and social competencies demonstrated greater self-control. A total of 80 workers participated in this study. They were able to manage and understand their own and others’ emotions in an intelligent and adaptive manner in their personal and professional lives.

In addition, EI (i.e., as per mixed models) predicts job success because it influences one’s ability to deal with environmental demands and pressures [ 17 ]. Therefore, it has been contended that several components of EI (i.e., as per mixed models) contribute to success and productivity in the workplace [ 18 ]; future research studies should extend this line of inquiry. Several studies have shown that people with high levels of ability EI communicate in an interesting and assertive manner, which in turn makes others feel more comfortable in the workplace [ 19 ]. In addition, it has been contended that EI (i.e., as per mixed models) plays a valuable role in group development because effective teamwork occurs when team members possess knowledge about the strengths and weaknesses of others and the ability to use these strengths when necessary [ 15 , 20 ]. It is especially important for senior managers to demonstrate high levels of EI because they play a predominant role in team management, leadership, and organizational development.

Finally, studies that have examined the relationship between EI and wellbeing have found that ability EI is a predictor of professional success, wellbeing, and socially relevant outcomes [ 21 – 23 ]. Extending this line of inquiry, Slaski and Cartwright [ 24 ] investigated the relationship between EI and the quality of working life among middle managers and found that higher levels of EI is related to better performance, health, and wellbeing.

EI and leadership

The actions of organizational leaders play a crucial role in modulating the emotional experiences of employees [ 25 ]. Accordingly, Thiel, Connelly, and Griffith [ 26 ] found that, within the workplace, emotions affect critical cognitive tasks including information processing and decision making. In addition, the authors have contended that leadership plays a key role in helping subordinates manage their emotions. In another study, Batool [ 27 ] found that the EI of leaders have a positive impact on the stress management, motivation, and productivity of employees.

Gardner and Stough [ 28 ] further investigated the relationship between leadership and EI among senior managers and found that leaders’ management of positive and negative emotions had a beneficial impact on motivation, optimism, innovation, and problem resolution in the workplace. Therefore, the EI of directors and managers is expected to be positively correlated with employees’ work motivation and achievement.

Additionally, EI competencies are involved in the following activities: choosing organizational objectives, planning and organizing work activities, maintaining cooperative interpersonal relationships, and receiving the support that is necessary to achieve organizational goals [ 29 ]. In this regard, some authors have provided compelling theoretical arguments in favor of the existence of a relationship between EI and leadership [ 30 – 34 ]. In this way, several researches [ 30 – 34 ] show that EI is a core and key variable positively related to effective and transformational leadership and this is important for positive effects on job performance and attitudes that are desirable in the organization.

Further, people with high levels of EI are more capable of regulating their emotions to reduce work stress [ 35 ]; thus, it is necessary to emphasize the importance of EI in order to meet the workplace challenges of the 21st century.

In conclusion, EI competencies are considered to be key qualities that individuals who occupy management positions must possess [ 36 ]. Further, EI transcends managerial hierarchies when an organization flourishes [ 37 ]. Finally, emotionally intelligent managers tend to create a positive work environment that improves the job satisfaction of employees [ 38 ].

EI trainings

Past studies have shown that training improves the EI of students [ 22 , 39 , 40 – 44 ], employees [ 45 – 47 ], and managers [ 48 – 52 ]. More specifically, within the academic context, Nelis et al. [ 22 ] found that group-based EI training significantly improved emotion identification and management skills. In another study, Nelis et al. [ 39 ] found that EI training significantly improved emotion regulation and comprehension and general emotional skills. It also had a positive impact on psychological wellbeing, subjective perceptions of health, quality of social relations, and employability. Similarly, several studies that have been conducted within the workplace have shown that EI can be improved through training [ 45 – 52 ] and have underscored the key role that it plays in effective performance [ 53 , 54 ].

In addition, two relevant metanalyses [ 8 , 55 ] concluded that there has been an increase in research interest in EI, recognition of its influence on various aspects of people’s lives, and the number of interventions that aim to improve EI. Relatedly, Kotsou et al. [ 55 ] and Hodzic et al. [ 8 ] reviewed the findings of past studies that have examined the effects of EI training to explore whether such training programs do indeed improve EI.

First, Hodzic et al. [ 8 ] concluded that EI training has a moderate effect on EI and that interventions that are based on ability models of EI have the largest effects. In addition, the improvements that had resulted from these interventions were found to have been temporally sustained.