- Religious Beliefs In The United Kingdom (Great Britain)

Freedom of Religion in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom, comprised of England , Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland , guarantees freedom of religion to its citizens and residents through 3 different regulations. One of these laws is the European Convention on Human Rights, which guarantees the right to free religious choice. Although freedom of religion is well established and practiced, some religious preference is given by the government. In the case of the monarchy for example, only Protestants may become king or queen (although they are now free to marry Catholics without losing their succession to the throne). Additionally, the Church of England is the state church of that country and the monarch swears an oath to protect both the Church of England and the Church of Scotland. Residents of the UK follow several different beliefs. Those beliefs are discussed below.

Irreligion in Great Britain

Irreligion is the lack of a religious belief, and includes such subcategories as atheism and agnosticism. Nearly half (49%) of the population of the UK identifies as irreligious. This number is one of the highest in Europe, although it follows a regional pattern toward secularization. Many researchers believe the UK has entered a period of post-Christianity in which the previously dominant Christian religion has given way to different values and cultures. Of the four countries that make up the UK, England is the least religious, followed by Scotland, Wales, and then Northern Ireland.

Anglican Christianity

Anglican Christianity is practiced in regional jurisdictions, such as the Church of England, Church of Scotland, Church of Ireland, and Church of Wales. In 1534, it split away from the Catholic church, prompting what is now known as the English Reformation era. Historically, this has been the predominant Christian denomination in the UK. Today, 17% of the population identify as Anglican.

Other Non-Catholic Christians

Besides Anglicanism and Catholicism, other Christian beliefs are practiced by 17% of the British population. A few of these denominations include non-Anglican Protestants, Orthodox Christians, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists. Many of the Protestant churches in Scotland broke away from the Anglican church, Church of Scotland, in the 19th Century. England and Wales began to form non-Anglican Protestant churches in the 1980’s. The Protestant denomination is the second largest in Northern Ireland. Methodism was introduced to England in the 18th Century and today, has around 290,000 members throughout Great Britain, but only 3,000 in Scotland. Church attendance of all of these denomination is declining.

Roman Catholicism

Catholicism has a long history in the United Kingdom. For nearly 200 years, however, from the 1500’s until the 1700’s, the Catholic church would not recognize the English monarchy. During this time, Catholics suffered discrimination, and were prohibited from voting, joining Parliament, and owning land. Today, 8% of the British population identifies as Catholic. The majority of these followers are in Northern Ireland where around 40% of the people are Catholic, and it is the dominant religion around the inland areas of Northern Ireland. In Scotland, approximately 15.9% of the population identifies as Catholic. This number drops significantly in England and Wales where it is only 7.4%.

The percentage of the population identifying as Muslim in the United Kingdom is 5%. The majority of these followers live in England and Wales, where they make up 3% of the population. They make up only .8% of the population in Scotland and in Northern Ireland fewer than 2,000 people practice Islam. Although these numbers are small, they grew 10 times faster than the population between 2001 and 2009.

Approximately 3% of the population practices some other religion not listed above. These religions include Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Sikhism, and the Baha’i Faith. Indian and Eastern religions in the United Kingdom are growing in size as immigrants continue to arrive from English-speaking areas, particularly former British colonies, in South and East Asia.

More in Society

Understanding Stoicism and Its Philosophy for a Better Life

Countries With Zero Income Tax For Digital Nomads

The World's 10 Most Overcrowded Prison Systems

Manichaeism: The Religion that Went Extinct

The Philosophical Approach to Skepticism

How Philsophy Can Help With Your Life

3 Interesting Philosophical Questions About Time

What Is The Antinatalism Movement?

Religious diversity is exploding – here’s what a faith-positive Britain might actually look like

Junior Research Fellow in Theology, University of Oxford

Disclosure statement

Dr Christopher Wadibia receives funding from a postdoctoral research fellowship specialising in race, theology, and religious studies based at Pembroke College, University of Oxford.

University of Oxford provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

The future of the UK’s Inter Faith Network (IFN), a long-standing charity that promotes dialogue and cooperation between Britain’s religious groups, is in doubt after the government announced it was withdrawing funding for the group. Communities secretary Michael Gove has cited concerns that a member of the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB), with which the government has suspended cooperation since 2009, has been appointed an IFN trustee.

In response to Gove’s letter, the IFN has said it had never been advised “to expel the MCB from membership”. It also said that while the government might choose not to engage with the MCB, doing so “is not a sensible option open to the IFN if it is to achieve the purposes for which the government funds it in the first place”.

Founded in 1987, the IFN represents Baha’i, Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, Jain, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh and Zoroastrian faith groups. In the charity’s 37-year history, religious pluralism in the UK has grown exponentially – and is still growing despite an overall decline in religiosity .

This underlines the importance of the interfaith dialogue the charity exists to promote. Indeed, the government-commissioned Bloom review of England’s growing religious pluralism, published in 2023, made a similar point when examining how the government might best acknowledge the value different faith groups bring to society.

The UK’s increasingly diverse faith landscape

In 2018, the Pew Research Centre published “Being Christian in Western Europe,” a survey of religion in 15 western European countries . The majority of the adults surveyed in 14 of the 15 countries considered themselves “non-practicing Christians”.

The survey found that the UK had roughly three times as many non-practicing Christians (55%) than church-going Christians (18%). It concluded that the notion of Christian identity remains a meaningful religious, political and sociocultural marker.

It also noted that many people have “gradually drifted away from religion, stopped believing in religious teachings, or were alienated by scandals or church positions on social issues.”

The rising number of people who subscribe to no religion belies the fact that the Christian proportion of the population is changing too. In 2023, British journalist Tomiwa Owolade reported on how demographic shifts are reshaping churches across the UK. Between 1980 and 2015, churches saw a 19% rise in attendance by non-white worshippers.

“Without immigration,” he wrote, “the decline of Christianity would be even more profound: it is largely white British people who are abandoning their faith.”

Recent migration from Hong Kong has seen the Chinese Christian community in the UK grow substantially. As of 2023, there are about 115,000 Chinese Christians worshipping at over 200 churches across the UK.

Newly arrived Chinese Christians bring with them a belief in the importance of Bible reading. They are strengthening Church of England congregations in cities including Manchester, Liverpool and Bristol.

This highlights how migrant populations in the UK and more broadly in western Europe wield increasing influence in terms of spirituality and belief. Between 2011 and 2021, the proportion of the population of England and Wales that identifies as Muslim has grown, from 4.8% (2.71 million people) to 6.5% (3.87 million) .

Other fast-growing religious groups in the UK include Shamanism, whose followers have increased from 650 people in 2011 to at least 8,000 in 2021 . Its emphasis on all things in nature – from people to the environment – being treated with dignity and respect distinctively appeals to the growing number of people in the UK who live with climate anxiety .

How the government engages with faith groups

Until now, UK politicians have largely only engaged with local faith groups in public when it has been politically expedient to do so. A primary motivation has often been to not be criticised by detractors for excluding communities on the basis of religion. This approach is underpinned by an Enlightenment theory of secularism, which sees engaging with issues of religion as unworthy of the looming headaches such engagement might cause.

The 2023 Bloom review, by contrast, calls for government to build constructive relationships with faith groups. “It should be the government’s responsibility,” Bloom writes, “to equip all civil and public servants with the basic factual knowledge to be able to recognise and understand the diverse religious life of the population.”

Appointed in 2019 by Boris Johnson, who was then prime minister, Colin Bloom was commissioned to explore what the government could do to better acknowledge and support the contribution faith groups make to society. He investigated how to better promote shared values and tackle harmful practices and how to promote both freedom of religion and freedom of speech. He also looked at how government officials might improve their faith literacy.

To be faith literate is to understand how belief systems differ and how those distinct from your own shape other people’s attitudes, values and experiences. In a bid to boost equality, Bloom recommends that government workplaces and educational settings adopt the term “faith-sensitive”.

As opposed to the flattening out of difference that a “faith-blind” approach can take, promoting faith-sensitivity encourages people in positions of authority to acknowledge, understand and treat with respect diverse belief systems.

The language the UK government uses on faith-related subjects matters. It models – for everyone living in the UK – how to best engage with diverse manifestations of belief .

I would argue that Bloom’s emphasis on a faith-sensitive government approach does not go far enough. It implies that the government’s priority should be to not cause offense. Even better would be a “faith-positive” approach that actively ascribes value to the contributions faith communities can make to everyday British life.

Back in 2001, the IFN said , “Greater awareness about the faith of others is crucial as we enter the 21st century in the UK because ignorance is a major contributor to prejudice and even to conflict.” Two decades on, the shocking rises in incidents of antisemitism and Islamophobia , in recent months, point to how urgently that remains true.

Early 20th century English writer G.K. Chesterton once affectionately wrote, “Let your religion be less a theory and more a love affair.” He was offering a framework to help British Christians better understand their faith. A similarly faith-positive approach to all of Britain’s belief systems would both recognise and value quite what people of faith can bring to wider British society.

- Freedom of speech

- Christianity

- Religious freedom

- Zoroastrianism

- Give me perspective

- UK religions

Events and Communications Coordinator

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

About this free course

Become an ou student, download this course, share this free course.

Start this free course now. Just create an account and sign in. Enrol and complete the course for a free statement of participation or digital badge if available.

1.1 Who is religious in Britain?

Religion in contemporary Britain appears to be something of a contradiction. The percentage of the population who are active religious adherents is falling. The number of people identifying as ‘non-religious’ accounts, by some estimates, for nearly half of the British population (NatCen Social Research, 2016).

Yet religion retains immense cultural influence, and the absolute numbers of religiously motivated people remain significant enough to require consideration in local and national policy decisions. A variety of religiously committed people are also regularly encountered on high streets and neighbourhoods throughout Britain.

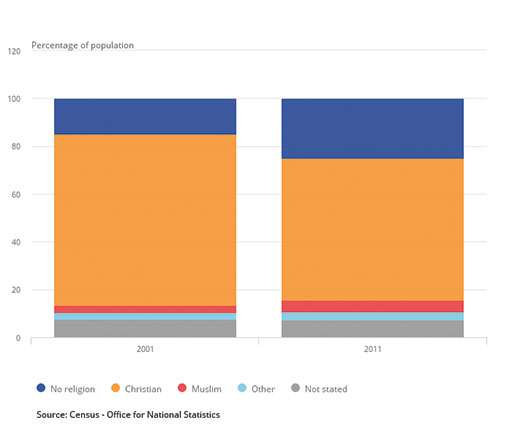

The figure below compares how the population of England and Wales defined their religious identity in the 2001 and 2011 censuses.

This is a stacked bar graph. The y axis shows the percentage of the population and the x axis shows the year. There are two bars, one for 2001 and one for 2011. There is a key at the bottom showing each categories colour. The categories are ‘No religion’, ‘Christian’, ‘Muslim’, ‘Other’, and ‘Not stated’. For 2001 the following percentages are shown: No religion: 14.8%, Christian: 71.7%, Muslim: 3%, Other: 2.8%, and Not stated: 7.7%. For 2011 the following percentages are shown: No religion: 25.1%, Christian: 59.3%, Muslim: 4.8%, Other: 3.6%, and Not stated: 7.2%.

The largest section of the population is represented in orange, those who identify with the general label of ‘Christian’. This included 69% of the population of England and Wales in the 2011 census (White, 2012). In Scotland, 54% of the population identified as Christian (National Records of Scotland, 2013a).

The most noticeable change between 2001 and 2011 is the increase in the blue ‘No religion’ identification. In 2011, nearly 25% of the population of England and Wales were happy to identify with this label (White, 2012). In Scotland, 37% of the population identified as non-believers in the 2011 census (National Records of Scotland, 2013b).

Yet what exactly it means to self-identify as ‘non-religious’ is a subject that is not very well understood. Recent research suggests that being ‘non-religious’ does not usually equate to being a committed atheist or humanist. Rather identifying as ‘non-religious’ might signify a position of personal disinterest about matters relating to religion (Lee, 2016).

Reinforcing the continuing cultural influence of Christianity, the Church of England has been established in law since 1534, and the national churches of Wales and Scotland still have significant political and popular influence in their respective areas.

The Christian religion underpins much of Britain’s legal and cultural assumptions. The Church of England exerts influence on legislation through the ‘Lords Spiritual’, 26 bishops who sit in the House of Lords.

Where religion ends and culture begins is not necessarily straightforward. This is one of many things the study of religion exposes. The unique history of Northern Ireland creates a very different religious landscape. Here 41% identified as Catholic and 42% identified with Presbyterian, Church of Ireland or other Protestant denominations. Those identified as non-religious made up less than 17% of the population in 2011 (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2012).

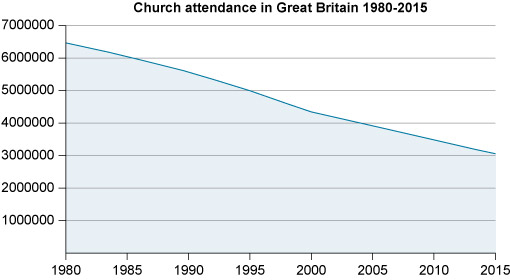

Despite the continued legal and cultural significance of Christianity in Britain, it is also clear that only a small proportion of the British population attend church on Sunday. Recent counts put this number as less than 6% of the British population. Yet the absolute number of regular churchgoers still total over 3 million, a significant section of the population. (Brierley in McAndrew, 2016)

This is a line graph showing chuch attendance in Great Britain between 1980 and 2015. The y axis shows attendance in millions. The x axis shows the year in 5 year increments from 1980 to 2015. Attendance is plotted along a fairly straight line from 6.5 million in 1980 to 3 million in 2015.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

What role can religion play in modern Britain?

Your editorial ( If organised mainstream Christianity is on the way out, what will replace it? , 16 July) poses a question of profound importance concerning the kind of society and culture we hope our grandchildren’s children will live in. Perhaps a hint of the direction of travel is to be found on the letters page (13 July), where the Director of Cafod (Catholic Agency for Overseas Development) describes recent practical action and political campaigning by thousands of members of faith communities who, in face of the climate emergency and the threat of ecological collapse, “hear the cry of the earth, and of the poor who experience the injustice of climate change”. She cites the spiritual leader of the largest Christian community, Pope Francis, who in Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home, his 2015 message to the peoples of the world made clear that the mission of the church now includes an urgent priority to support efforts to prevent further environmental deterioration and to achieve a sustainable lifestyle.

Developments in the academic fields of ecology and religion and “spiritual environmentalism”, especially in North America, give an advance glimpse of a future in which humankind rediscovers our capacity to wonder at the “sacred” mystery of the emergence and evolution of life in the universe, and reinstates our neglected relationship with the natural world on which our survival as a species ultimately depends. Perhaps an “eco-theology” is the future to which the last 2,000 years of history have been pointing? Michael Barrett Oxford

That organised religion continues to decline is tough news for the faithful few, but the bigger question is how do we evaluate such facts? Is life in Britain better for all because not so many go to church, synagogue or mosque? Or is that question also too simple when we can all see that there is good and bad in all faiths and in those who are not religious? Guardian readers will also know that more people read the tabloids and the rightwing press than the Guardian. Is the value of everything to be determined by a show of hands or would God still care about us even if more and more people are unaware of Him? And do we still believe in the Guardian because of its simple faith that facts are sacred and better than fake news if it is not popular to say so? Rev Dr Donald Norwood Oxford

Humanism certainly has the potential to fill the gap left by organised religion with a robust grounding in moral philosophies stretching back to the Greeks, via the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and modern British philosophy (something we should be proud of). Although only about 6% of UK adults identified as “humanist” in a 2014 YouGov poll, 36% said they shared humanist values. However, humanism faces an uphill struggle when the government insists on funding yet more single-religion faith schools.

I only discovered humanism in my 50s. Nobody ever told me about humanism at school – a situation I am trying to remedy through school volunteering for Humanists UK. As to whether irreligion should be “organised”, the established religions have amply demonstrated that such organisations are more concerned with their own survival than the welfare of their participants. It seems unlikely to me that young people will turn back to such outdated institutions when they have failed to provide global leadership on the pressing issues of inequality, human rights and climate destruction.

Hopefully, the next generation will learn to think for themselves and become capable of recognising that it is the responsibility of humans alone to make the world a better place. Richard Gilyead Saffron Walden, Essex

By far the biggest factor in the long-term decline of organised religion in western Europe has been the rise of moral autonomy. Attitudes to same-sex marriage, homosexuality, women’s rights, abortion and assisted suicide have shifted in a generation. There has been a groundswell of public opinion in favour of more liberal approaches towards the rights and freedoms of the individual. The result is religion-free morals. Three things only remain to be dealt with. The Church of England remains the established religion, automatic places are granted to 26 Anglican bishops in the House of Lords , and the state funds religious groups to run discriminatory schools that inculcate children with their beliefs. Doug Clark Currie, Midlothian

Your leader comments on the latest BSA survey and the continuing decline in organised religion, not least in the Church of England. On Sunday last, in most mainstream churches, the gospel story of the good Samaritan will have been read. Here is a story familiar and indeed loved by most of the population of non-churchgoers and believers alike. The outsider who shows love and compassion is exalted above the representatives of organised religion whose rules forbade them risking being in contact with the man lying in the gutter. Jesus preferred love in action to “good religion”, with its rules about who was (and was not) included in the household of God. Organised religion – “Church”– might still need to learn the lesson that its founder seems to have wanted people to be more compassionate, not more religious. Let’s strive for goodness in our present society and perhaps godliness will follow. Rev Adrian Alker Chair, Progressive Christianity Network Britain

It is very surprising that your editorial makes no reference to agnosticism, the conviction that nothing is known or can be known of the existence or nature of God. Is its omission part of human arrogance? Tom Swallow Kenilworth, Warwickshire

Your editorial notes that the latest British Social Attitudes survey records just 1% of under-24s now identifying as Anglican. This statistic alone shows what nonsense it is that the Church of England can still be regarded and treated as the “established” church, yet 26 seats in the House of Lords are reserved for its archbishops and senior bishops. I think Iran is the only other country whose legislature grants such privileges to the leaders of its state religion. We still like to present ourselves as a “modern democracy” – hoping others don’t notice this anomaly (or the 92 hereditary members of the House of Lords). John Boaler Calne, Wiltshire

Read more Guardian letters – click here to visit gu.com/letters

- Anglicanism

- Christianity

- Catholicism

- Pope Francis

Most viewed

Religion in the UK - practising your faith

As a multi-faith society, students of all religions can expect to feel welcome in the UK, along with plenty of places to practise their faith. With a history of multiculturalism dating back hundreds of years, we have well-established communities representing all major religions, and a deep commitment to supporting students’ religious needs on campus.

Most schools, colleges and universities have prayer rooms that anyone can use, as do most public places, such as hotels, hospitals and airports. There are also many organisations representing students of a particular faith who can provide information and support from day one.

Most universities have multi-faith chaplaincy services, designed to provide spiritual support to all their students. Chaplains invite all students to drop-in and talk, as well as leading services and directing all aspects of the university’s religious life.

We are proud to be a very tolerant society in every way, and it is against the law to discriminate against anyone because of their race, nationality, or religion. This is one of the most influential reasons international students from all over the world choose the UK for their studies.

What faiths are represented in the UK?

The UK’s official religion is Christianity, and churches of all denominations can be found throughout the UK, such as Catholic, Protestant, Baptist and Methodist. The main other religions are Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Judaism and Buddhism.

In the larger towns and cities in the UK it’s easy to find somewhere to practise your faith as well as a community of people there to welcome you, whether that be a church, mosque, gurdwara, temple or synagogue. In smaller towns, you may find only Christian churches. Having strong religious communities in our cities also makes it easy to find additional things such as foods that are a key part of your faith.

Can I wear religious items in the UK?

Many people in the UK choose to wear their items of religious dress every day (such as turbans, hijabs and yarmulkes) and to observe religious festivals, such as Christmas, Eid, Diwali or Hanukkah. As a tolerant country you are free to choose exactly how you want to integrate your faith into your life.

To find out more about how your university can help you practise your faith, and if it has a dedicated organisation that you can join, get in touch with their pastoral care team directly.

Student-led religious organisations:

- FOSIS (The Federation of Student Islamic Societies)

- Ahmadiyya Muslim Students Association UK

- British Organisation of Sikh Students

- Student Christian Movement

- National Hindu Students’ Forum UK

- Network of Buddhist Organisations

- The Union of Jewish Students

More in this section

The UK is a union of four nations – England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, with similarities and differences that make studying in each nation unique.

English is spoken across the UK, but it is not the only native official language. In London alone it is estimated that you can hear over 300 languages.

Dive into the UK’s rich history and contemporary culture by enjoying the world-famous events, local celebrations and public holidays.

The weather in the UK can be unpredictable. But with the right clothes and the right attitude, you can enjoy the UK, whatever the weather.

Enjoy the huge variety of food the UK has to offer. Here are our eight top tips for shopping, cooking and eating out while at university.

Travel and transport

Whether you’re based in the city or the countryside, you’ll be able to travel to most places in the UK quickly and see a lot during your time here.

Health and welfare

With one of the most advanced healthcare systems in the world, as an international student in the UK you will be looked after.

A warm welcome

The UK is a modern society that embraces all ways of life. Everyone is welcome. As an international student in the UK, you’ll feel at home wherever you go.

Support while you study

Moving to the UK to study is exciting, but we know that getting settled into a new country can be daunting, too. Find out how and where to get support.

Student life in the UK

A UK education goes far beyond what you learn from your studies. Discover the unforgettable student experiences you can have when you study in the UK.

Sign up to our newsletter

Get the latest updates and advice on applications, scholarships, visas and events.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with EHR?

- About The English Historical Review

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Books for Review

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Religion and Society in Twentieth-Century Britain

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

R. Mckibbin, Religion and Society in Twentieth-Century Britain, The English Historical Review , Volume CXXII, Issue 499, December 2007, Pages 1464–1468, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cem387

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In this book, Callum Brown presents a ‘strong’ explanation for the apparent decline of religion in twentieth-century Britain. The argument is broadly as follows. Neither world war was fatal to British Christianity, and both had a marked religious or quasi-religious culture. Although women were crucial, and increasingly crucial, to the life and success of British religion, men developed their own forms of religious observance, such as the rituals of Armistice Day or the singing of ‘Abide With Me’ before the Cup Final. Despite what is widely thought, the working class was not especially irreligious; indeed, the upper working class was perhaps the most religious segment of British society. Nor was there any serious questioning of ‘Christian’ precepts, and until the 1960s no significant weakening of religious influence on the moral choices people made as to the size of their families. The twentieth century was not a story of gradual moral secularisation: rather it is the story—until the 1960s—of a continuously powerful ‘restrictive Christian state’. In fact, Brown argues, the 1950s were even more morally restrictive than the 1930s. Throughout this period British Christianity was dominated by two different and competing systems: an undemanding religion, ‘mellow religion’, and a very demanding evangelicalism. The 1960s, however, saw the collapse of both. They were undermined by the emergence of a hedonistic popular culture, by theological attacks on conventional religious belief (of which the most celebrated was John Robinson's Honest to God [1963]) and by the withdrawal of women en masse from the church, itself the result of a number of moral, technological (the Pill) and social changes which the churches were incapable of understanding. That decade also saw the end of casual church attendance. The division today is no longer between those who go to church irregularly and those who go regularly, but between those who go regularly and those who never go at all. Britain has thus become one of the most secular societies in the world. The rather militant religion of contemporary Britain, much influenced by charismatic-pentecostal movements, is militant because of weakness rather than strength. Christians now concentrate on getting believers into positions of importance rather than getting the population back to church. This ‘white’ secularism is, however, not shared by many of Britain's ethnic minorities. Britain is a secular society only because whites constitute the large majority of the population.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-4534

- Print ISSN 0013-8266

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Debating the Faith: Religion and Letter Writing in Great Britain, 1550-1800

- © 2013

- Anne Dunan-Page 0 ,

- Clotilde Prunier 1

, Études Anglophones, Université de Provence, Aix-Marseille I, Aix-en-Provence, France

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

Ouest Nanterre-La Défen, Université Paris, Nanterre Cedex, France

- First book to highlight the role of letters as key documents in religious communication and debate

- Discussion on epistolary culture

- Contains interdisciplinary chapters on the role of letters in British Culture, Protestantism and Catholicism ?

Part of the book series: International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives internationales d'histoire des idées (ARCH, volume 209)

5950 Accesses

13 Citations

2 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (12 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

- Gary Schneider

Protestant Identities

Scribal networks and sustainers in protestant martyrology.

- Mark Greengrass

Thomas Browne, the Quakers, and a Letter from a Judicious Friend

- Reid Barbour

Writing Authority in the Interregnum: The Pastoral Letters of Richard Baxter

- Alison Searle

Letters and Records of the Dissenting Congregations: David Crosley, Cripplegate and Baptist Church Life

Anne Dunan-Page

Representations of British Catholicism

‘for the greater glory’: irish jesuit letters and the irish counter-reformation, 1598–1626.

- David Finnegan

Negotiating Catholic Kingship for a Protestant People: ‘Private’ Letters, Royal Declarations and the Achievement of Religious Detente in the Jacobite Underground, 1702–1718

- Daniel Szechi

‘Every Time I Receive a Letter from You It Gives Me New Vigour’: The Correspondence of the Scalan Masters, 1762–1783

Clotilde Prunier

Religion, Science and Philosophy

Utopian intelligences: scientific correspondence and christian virtuosos.

- Claire Preston

Debating the Faith: Damaris Masham (1658–1708) and Religious Controversy

- Sarah Hutton

Evangelical Calvinists Versus the Hutcheson Circle: Debating the Faith in Scotland, 1738–1739

- James Moore

Questioning Church Doctrine in Private Correspondence in the Eighteenth Century: Jean Bouhier’s Doubts Concerning the Soul

- Ann Thomson

Back Matter

- British Catholicism

- British Protestantism

- epistolary writing

- religious letters in early-modern Britain

- role of letters in religious communication

- role of letters in sustaining faith

About this book

Editors and affiliations, about the editors, bibliographic information.

Book Title : Debating the Faith: Religion and Letter Writing in Great Britain, 1550-1800

Editors : Anne Dunan-Page, Clotilde Prunier

Series Title : International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives internationales d'histoire des idées

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5216-0

Publisher : Springer Dordrecht

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law , Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013

Hardcover ISBN : 978-94-007-5215-3 Published: 06 November 2012

Softcover ISBN : 978-94-017-8222-7 Published: 14 December 2014

eBook ISBN : 978-94-007-5216-0 Published: 05 November 2012

Series ISSN : 0066-6610

Series E-ISSN : 2215-0307

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : X, 218

Topics : History of Philosophy , Religious Studies, general , History of Science

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN

Published by Reilly Glasscock Modified over 9 years ago

Similar presentations

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

Great Britain

Jul 17, 2014

470 likes | 1.22k Views

Great Britain. Great Britain. Great Britain is made up of the countries of England, Scotland and Wales. The Kingdom of Great Britain was established on 1 st May 1707 when the three countries signed the Acts of Union.

Share Presentation

- national flag

- longest undersea rail tunnel

- huge sculpture

Presentation Transcript

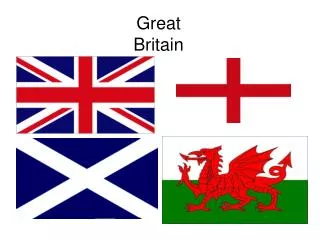

Great Britain • Great Britain is made up of the countries of England, Scotland and Wales. • The Kingdom of Great Britain was established on 1st May 1707 when the three countries signed the Acts of Union. • In 1801 the Kingdom of Great Britain merged with the Kingdom of Ireland to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. • After the Irish war of independence it is now the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The southern part of Ireland is now the Republic of Ireland.

Great Britain only refers to the countries of England, Scotland and Wales and some of the outlaying islands such as the Isle of Wight, the Hebrides, Anglesey, Orkney and Shetland. • It is surrounded by around 1000 islands and islets. • Great Britain does not include the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands.

Geography • Great Britain is northwest of Continental Europe and is separated by the North Sea and the English Channel. • The English channel becomes narrow at the Straits of Dover and here Great Britain is only 34 kilometres from Continental Europe. • The greatest distance between two points is 968km between John O’Groats in Caithness, Scotland and Land’s End in Cornwall, England.

Great Britain is physically connected to Continental Europe by the Channel Tunnel. • This is the longest undersea rail tunnel in the world. • Construction began in 1988 and it was completed in 1994. • London to Paris now takes 2 hours and 15 minutes on the train.

Great Britain’s highest mountain is Ben Nevis in Scotland and is 1334 metres tall. • The longest river in Great Britain is the river Severn at 354 kilometres long. • The largest city in Great Britain is London.

England is the biggest country in Great Britain but no place in England is more than 120km from the sea. • In the south west the landscape is rolling hills whilst the south east is mostly flat. The north and west are more mountainous and have areas such as the Lake District. • Wales and Scotland are far more mountainous than England.

England • The capital of England is London. • Other big cities in England are Birmingham, Bristol, Manchester, Liverpool and Newcastle. • Historic cities include Bath, Canterbury and Stratford-upon-Avon. • The population of England is around 59 million which accounts for 84% of the population of Great Britain. • England is divided in to 48 counties.

England’s patron saint is Saint George. • The St George’s Cross has been the national flag of England since the 13th century. • The Royal Arms of England are the 3 lions. These are seen on the England football and cricket kits. • England’s flower in the red Tudor rose. This is seen on the England rugby union kit. • The national anthem is called God Save the Queen.

Bath • Bath is home to some of the oldest Roman Baths in the World and is the only place in Britain where there are natural hot thermal waters.

Tyne and Wear • The Angel of the North is a huge sculpture on a hill in Gateshead. • Newcastle is know for its dramatic bridges, including the Tyne Bridge.

Stratford-Upon-Avon • This was the birthplace of William Shakespeare and is also where he is buried at Holy Trinity Church.

Wiltshire • Stonehenge is believed to have been built in around 3100BC. • It remains a mystery as to what its purpose was.

Scotland • The capital of Scotland is Edinburgh, however, Glasgow is a bigger city. • Aberdeen is the third biggest city in Scotland and also Europe’s oil capital. • The population of Scotland is around 5 million with 1.2 million people estimated to live in Glasgow. • Scotland has three official languages, English, Scots and Scottish Gaelic. • Only 7% of the population are fluent in Scots or Gaelic.

Scotland’s patron saint is Saint Andrew. • Their flag is the St Andrew’s Cross or Saltire and is the longest flag still in use. It was first used in the 9th century. • The Scottish emblem is one red lion. • The Scottish floral emblem is a Thistle. • Scotland’s national anthem can also be God Save the Queen however, this is rarely used and the unofficial anthem, O Flower of Scotland, is far more common.

Edinburgh • Edinburgh is a UNESCO World Heritage sight. • The site of the castle has been inhabited since 900BC.

Glasgow • Famous architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh was born in Glasgow, his designs can be seen all over the city, including the Armadillo.

Wales • The capital of Wales is Cardiff. • Other notable cities are Swansea and Newport. • The population is around 3 million people. • Wales is officially bilingual, both English and Welsh are used on things such as road signs. • Around 20% of the population are fluent in Welsh. • Wales also has the longest recognised place name in the world: Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch

The patron saint of Wales is Saint David. • The national flag of Wales is the Red Dragon and came in to use in the 1400s. • The national emblems of Wales are the leek and the daffodil. • The Prince of Wales heraldic badge of three feathers is also used to symbolise Wales. • The national anthem of Wales is Land of my Fathers.

Cardiff • Cardiff Castle is a medieval castle and palace. • In the 1800s the Marquess of Bute had his architect transform the castle in to a lavish palace.

Newport • Settlements have been found here dating back to the Bronze Age. • The Normans built Newport Castle in 1088 on the site of an old Bronze Age castle.

- More by User

Great Britain. Britain is an island in the Atlantic Ocean and it is situated in the north-west of Europe. Starting from 1801 along with Northern Ireland. It forms the United Kingdom. The borders are Anglesey, Isle of Wight, the Hebrides Islands, the Orkney Islands and Shetland Islands.

457 views • 4 slides

Great Britain. Great Britain is build up of four Home Nations:. England Northen Ireland Scotland Wales These Home Nations were separated in the past. . UK. But, today the four Home Nations are united and Great Britain has another name – U nited K ingdoms - UK. Geography.

327 views • 0 slides

GREAT BRITAIN

GREAT BRITAIN . By Nick Causey, Nick Soper , Amapreet Kaur , Navya Jaikumar. David Lloyd George. Rise to Power. Born on January 17 th , 1863 Trained to become a lawyer Opened own practice Learned the art of public speaking

756 views • 61 slides

Great Britain. Great Britain. United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Includes: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Collectively referred to as the UK or Great Britain Size of Oregon Approx 60 million residents Island separated by English Channel . UK.

885 views • 41 slides

Great Britain. Agenda. The country The people The religion The queen Their believes Typically British Conclusion. Great Britain. United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Population: ~ 60 million people Capital Cities: United Kingdom: London England : London

692 views • 26 slides

Great Britain. Capital is London. Made by: Oskar Kwapiński, Krystian Paprzycki and Filip Królikowski. Monuments England.

365 views • 10 slides

Great Britain. Grande Bretagne. three countries. Scotland. England. Wales. trois régions . L'Ecosse. L'Angleterre. Le pays de Galles. England. L'Angleterre. Wales. Le pays de Galles. Scotland. L'Ecosse. The United Kingdom is an island. Le Royaume-Uni est une île. three seas.

436 views • 32 slides

GREAT BRITAIN. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The UK consists of four main parts which are: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Their capitals are London, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast. Language.

1.3k views • 22 slides

Great Britain

Great Britain . Clothing. Costumes- very much a western society they wear very much the same as any other modern western such as jeans and tee shirts to full business suits for office work. Some of the ladies wear corsets all the time for show.

374 views • 7 slides

Germany. France. Russia. Great Britain . The Race That Led to WWI. Revolutions That Rocked Europe.

333 views • 12 slides

GREAT BRITAIN. Vypracovali: Janka Gurínová Ivana Janoušková. MAP. BRITAIN. There are several names for Britain : Britain , Great Britain , United Kingdom (UK) There are four countries in the UK: England , Scotland , Wales and Northern Ireland. FLAG.

935 views • 11 slides

Great Britain. Great Britain Map. The Union Jack. England. Patron St.George red rose flower England flag White colour. Wales.

351 views • 10 slides

Great Britain. I would like to tell you about my favorite country. It’s Great Britain. It’s an English-speaking country and I would like to go to Britain. I would like to visit many beautiful and interesting places. And I would like to tell you about these places now.

690 views • 14 slides

Great Britain. Greetings

151 views • 3 slides

GREAT BRITAIN. WALES. The first tribe who settled in Wales was the Britons , a Celtic tribe . It is located in the western area of Great Britain . Cardiff, the capital, is the most important seaport .

2.03k views • 27 slides

Great Britain. My favourite country is Great Britain, which capital is London. And my project is about this wonderful city. LONDON is the capital of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. It is one of

1.07k views • 23 slides

Great Britain. By: Erin Armstrong, Brittany Hart & Raza Naqvi. Security Concerns. Hostile powers dominating European Continent Financial Security of the country. Physical Issues, greatly weakened Britain could not ensure safety or prosperity of her people. Issues, Values,& Fundamentals.

285 views • 8 slides

Great Britain. Symbols. How was the flag of United Kindom made ?.

267 views • 9 slides

Great Britain. Map of Great Britain. About Great Britain. Great Britain is the official name given to the two kingdoms of England and Scotland , and the principality of Wales . Great Britain is made up of: England - The capital is London . Scotland - The capital is Edinburgh .

569 views • 6 slides

Great Britain. Lea Kiilaspea Pille-Riin Jakobson Katariina Lepik Silvia Kutsar. Great Britain. Is an island in the Atlantic ocean London 60 million people. Unemployment. Total 7,1% Youth 14,1%. Unemployment benefits. Unemployment compensation 40-50% of their previous pay Six months

330 views • 8 slides

Great Britain. The King and Parliament. Great Britain came into existence in 1707 when the governments of England and Scotland were united. The term British came into use to refer to both English and Scots. Parliament. Monarchy.

264 views • 7 slides

GREAT BRITAIN. PORTSMOUTH. MARITIME MUSEUM. PORTSMOUTH. HMS Warrior at the entrance to the Maritime Museum. HMS Warrior 1860-sailing with steam drive. Stoommachine. Opgevist oud anker. HMS VICTORY.

626 views • 49 slides

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Sikhism (0.7%) Judaism (0.4%) Buddhism (0.4%) Other religion (0.4%) Religion not stated (7.2%) British society is one of the most secularised in the world and in many surveys determining religious beliefs of the population agnosticism, nontheism, atheism, secular humanism, and non-affiliation are views shared by a majority of Britons. [1]

Islam. The percentage of the population identifying as Muslim in the United Kingdom is 5%. The majority of these followers live in England and Wales, where they make up 3% of the population. They make up only .8% of the population in Scotland and in Northern Ireland fewer than 2,000 people practice Islam. Although these numbers are small, they ...

Today it is the second largest religion in the UK. Islam has been present in the United Kingdom since it's information in 1707, though it was not legally recognised until the Trinitarian Act in 1812. The growing number of Muslims has resulted in the establishment of more than 1,500 mosques in the UK. 9. JEWISH In the 2001 Census, 266,740 ...

United Kingdom - Christianity, Islam, Judaism: The various Christian denominations in the United Kingdom have emerged from schisms that divided the church over the centuries. The greatest of these occurred in England in the 16th century, when Henry VIII rejected the supremacy of the pope. This break with Rome facilitated the adoption of some Protestant tenets and the founding of the Church of ...

United Kingdom France Australia Germany Canada Spain Italy Russia United States Poland Greece Brazil Mexico Indonesia Morocco Nigeria Iran Philippines Believe Don't believe United Kingdom UK base: 3,056 people in the UK aged 18+, surveyed 1 Mar-9 Sept 2022. Other countries all surveyed in wave 7 of WVS at various points between 2017 and 2022.

British society is one of the most secularised in the world and in many surveys determining religious beliefs of the population agnosticism, nontheism, atheism, secular humanism, and non-affiliation are views shared by a majority of Britons. Historically, it was dominated for over 1,400 years by various forms of Christianity, which replaced preceding Romano-British religions, including Celtic ...

Religion in modern Britain ... a Wesleyan chapel 1819 - a Methodist chapel Late 19th c. - the Spitalfields Great Synagogue 1976 - a mosque, the London (now Brick Lane) Jamme Masjid ... Regional differences Iconic buildings PowerPoint Presentation Successful churches High levels of migration Other faith communities A many-layered and ...

Between 2011 and 2021, the proportion of the population of England and Wales that identifies as Muslim has grown, from 4.8% (2.71 million people) to 6.5% (3.87 million). Other fast-growing ...

Having a Prime Minister of the United Kingdom or President of the United States who shares the moral values and religious beliefs of its citizens is relatively important to Brits and Americans, from 57% of people in the UK to 67% of people in the US, but many, including more than four-in-10 of those who are not religiously

The Christian religion underpins much of Britain's legal and cultural assumptions. The Church of England exerts influence on legislation through the 'Lords Spiritual', 26 bishops who sit in the House of Lords. Where religion ends and culture begins is not necessarily straightforward. This is one of many things the study of religion exposes.

Presentation Transcript. Religion in the United Kingdom has been dominated, for over 1,400 years, by various forms ofChristianity. History of religion in the UK • Britain used to be a Roman Catholic country. • In 1533, during the reign of Henry VIII, England broke from the Roman Catholic Church to form the Anglican Church.

Oxford. Humanism certainly has the potential to fill the gap left by organised religion with a robust grounding in moral philosophies stretching back to the Greeks, via the Renaissance, the ...

The UK's official religion is Christianity, and churches of all denominations can be found throughout the UK, such as Catholic, Protestant, Baptist and Methodist. The main other religions are Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Judaism and Buddhism. In the larger towns and cities in the UK it's easy to find somewhere to practise your faith as well as ...

Early Modern Britain and the world, 1500-1750 overview - OCR B Changing ideas about religion. Huge changes in Britain's world role emerged from the Reformation, the beginnings of European ...

Today I am very happy to be joined by Professor James Early to discuss how Christianity was reintroduced to the British Isles or to be precise, how it was in...

Extract. In this book, Callum Brown presents a 'strong' explanation for the apparent decline of religion in twentieth-century Britain. The argument is broadly as follows. Neither world war was fatal to British Christianity, and both had a marked religious or quasi-religious culture. Although women were crucial, and increasingly crucial, to ...

The United Kingdom comprises the whole of the island of Great Britain —which contains England, Wales, and Scotland —as well as the northern portion of the island of Ireland. The name Britain is sometimes used to refer to the United Kingdom as a whole. The capital is London, which is among the world's leading commercial, financial, and ...

Within the field of Law and Religion, it is not possible to provide a single response from the United Kingdom as a whole. An analysis of any aspect within this field will require us to focus on England and Wales, Footnote 1 Scotland and Northern Ireland, separately, since they are separate jurisdictions with widely divergent legislation in the area of Law and Religion.

About this book. The first book to address the role of correspondence in the study of religion, Debating the Faith: Religion and Letter Writing in Great Britain, 1550-1800 shows how letters shaped religious debate in early-modern and Enlightenment Britain, and discusses the materiality of the letters as well as questions of form and genre.

1 THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN. It is a monarch state situated in the North-West of Europe. UK is composed of four countries: 1-England 2-Scotland 3-Wales 4-Northern Ireland The Uk is surrounded by Atlantic Ocean,the North Sea and the English Channel that separates the UK from the continent. The flag of the UK is the UNION FLAG,also ...

Presentation Transcript. Great Britain • Great Britain is made up of the countries of England, Scotland and Wales. • The Kingdom of Great Britain was established on 1st May 1707 when the three countries signed the Acts of Union. • In 1801 the Kingdom of Great Britain merged with the Kingdom of Ireland to create the United Kingdom of Great ...

2. 3. In geography, Great Britain is the largest island in Europe. It is the main part of the United Kingdom. It contains England, Scotland and Wales. England is the biggest part of the island. England is in the southeast. Wales is to the west of England. Scotland is to the north of England.