We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it. Privacy policy

Open-Ended Questions in Qualitative Research: Strategies, Examples, and Best Practices

Table of content, understanding open-ended questions, designing open-ended questions, types of open-ended questions, conducting interviews and focus groups with open-ended questions, analyzing and interpreting open-ended responses, challenges and limitations of using open-ended questions, best practices for using open-ended questions in qualitative research, definition of open-ended questions.

Open-ended questions are a research tool that allows for a wide range of possible answers and encourages respondents to provide detailed and personalized responses. These types of questions typically begin with phrases such as “ How ,” “ What ,” or “ Why “, and require the respondent to provide their thoughts and opinions.

Open-ended questions are crucial in the following scenarios:

Understanding complex phenomena : When a topic is complex, multi-faceted, or difficult to measure with numerical data, qualitative research can provide a more nuanced and detailed understanding.

Studying subjective experiences: When the focus is on people’s perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, or experiences, qualitative research is better suited to capture the richness and diversity of their perspectives.

Developing theories: When a researcher wants to develop a model or theory to explain a phenomenon, qualitative research can provide a rich source of data to support the development of such hypotheses.

Evaluating programs or interventions: Qualitative research can help to evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions by collecting feedback from participants, stakeholders, or experts.

Researchers use open-ended methods in research, interviews, counseling, and other situations that may require detailed and in-depth responses.

Benefits of Using Open-Ended Questions in Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is most appropriate when the research question is exploratory, complex, subjective, theoretical, or evaluative. These questions are valuable in qualitative research for the following reasons:

More In-depth Responses

Open-ended questions allow participants to share their experiences and opinions in their own words, often leading to more in-depth and detailed responses. For example, if a researcher is studying cancer survivors’ experiences, an open-ended question like, “Can you tell me about your experience with cancer?” may elicit a more detailed and nuanced response than a closed-ended question like “Did you find your cancer diagnosis to be difficult?”

Flexibility

Open-ended questions give the participant flexibility to respond to the questions in a way that makes sense to them, often revealing vital information that the researcher may have overlooked.

Better Understanding

Open-ended questions provide the researcher with a better understanding of the participant’s perspectives, beliefs, attitudes, and experiences, which is crucial in gaining insights into complex issues.

Uncovering New Insights

Open-ended questions can often lead to unexpected responses and reveal new information. When participants freely express themselves in their own words, they may bring up topics or perspectives that the researcher had not considered.

Building Rapport

Open-ended questions help build rapport with the participant, allowing the researcher to show interest in the participant’s responses and provide a space for them to share their experiences without feeling judged. This can lead to a positive research experience for participants, which may increase the likelihood of their continued participation in future studies.

Validating or Challenging Existing Theories

By allowing participants to provide their own perspectives and experiences, researchers can compare and contrast these responses with existing theories to see if they align or diverge. If the data from participants align with existing hypotheses, this can provide additional support for this data. On the other hand, if the information diverges from existing theories, this can indicate a need for further investigation or revision of the existing data.

Avoiding Bias and Preconceived Notions

Researchers may unintentionally guide participants towards a particular answer or perspective when using close-ended questions. This can introduce bias into the data and limit the range of responses that participants provide. By using open-ended questions, researchers can avoid this potential source of bias and allow participants to express their unique perspectives.

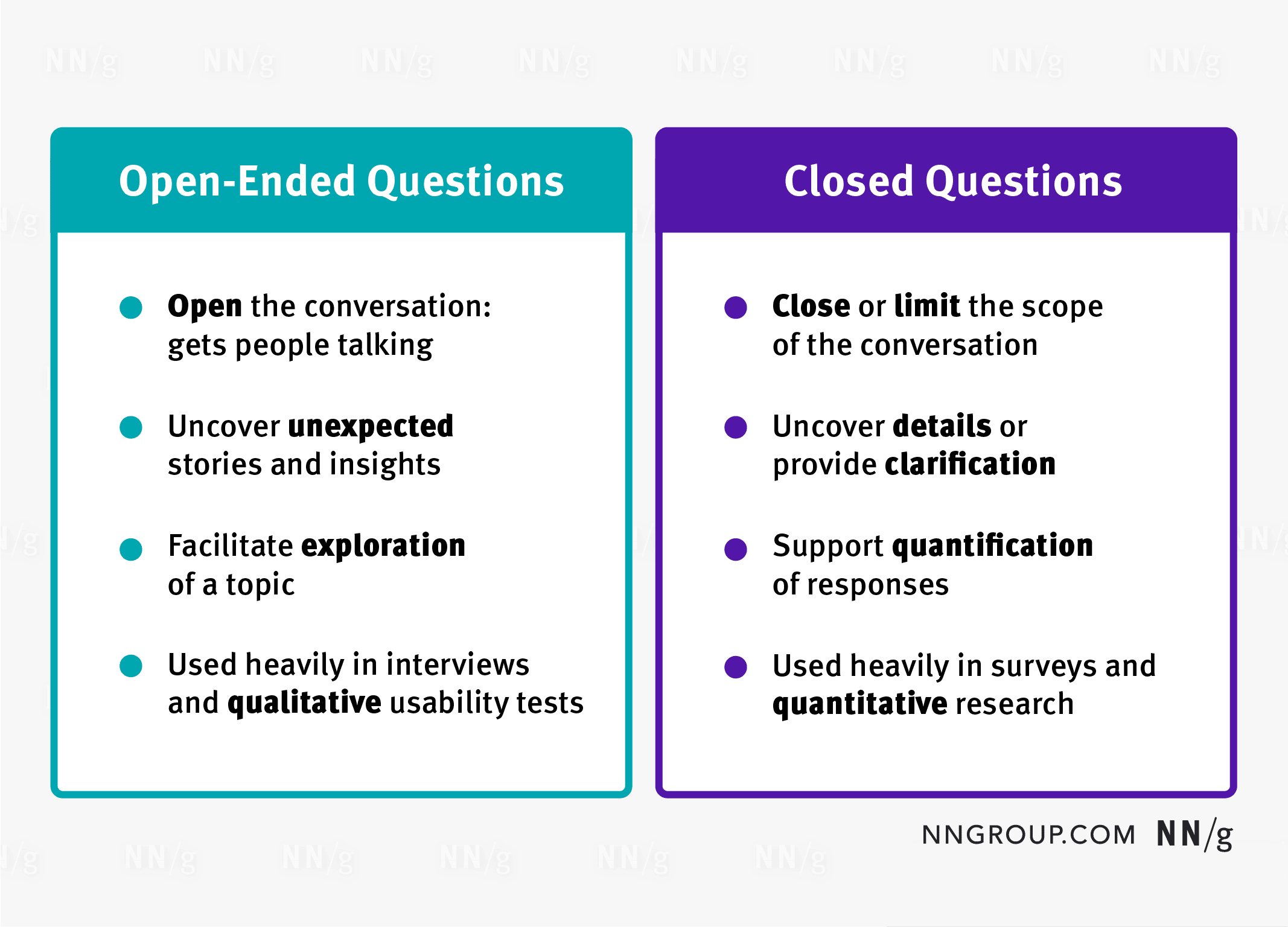

Differences Between Open-Ended and Closed-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions encourage numerous responses and allow respondents to provide their thoughts and opinions. “ What ,” “ How, ” or “ Why ” are some of the words used to phrase open-ended questions and are designed to elicit more detailed and expansive answers. Researchers use open-ended questions in ethnography, interviews , and focus groups to gather comprehensive information and participants’ insights.

Some examples of open-ended questions include:

- What do you think about the current state of the economy?

- How do you feel about global warming?

- Why did you choose to pursue a career in law?

On the other hand, closed-ended questions only allow for a limited set of responses and are typically answered with a “Yes” or “No” or a specific option from a list of multiple choices. These questions are handy in surveys, customer service interactions and questionnaires to collect quantitative data that can be easily analyzed and quantified. They are significant when you want to gather specific information hastily or when you need to confirm or deny a particular fact.

Some examples of closed-ended questions include:

- What was your shopping experience with our company like?

- Have you ever traveled to Europe before?

- Which of these brands do you prefer: Nike, Adidas, or Puma?

Both open-ended and closed-ended questions have their place in research and communication. Open-ended questions can provide rich and detailed information, while closed-ended questions can provide specific and measurable data. The appropriate question type typically depends on the research or communication goals, context and the information required.

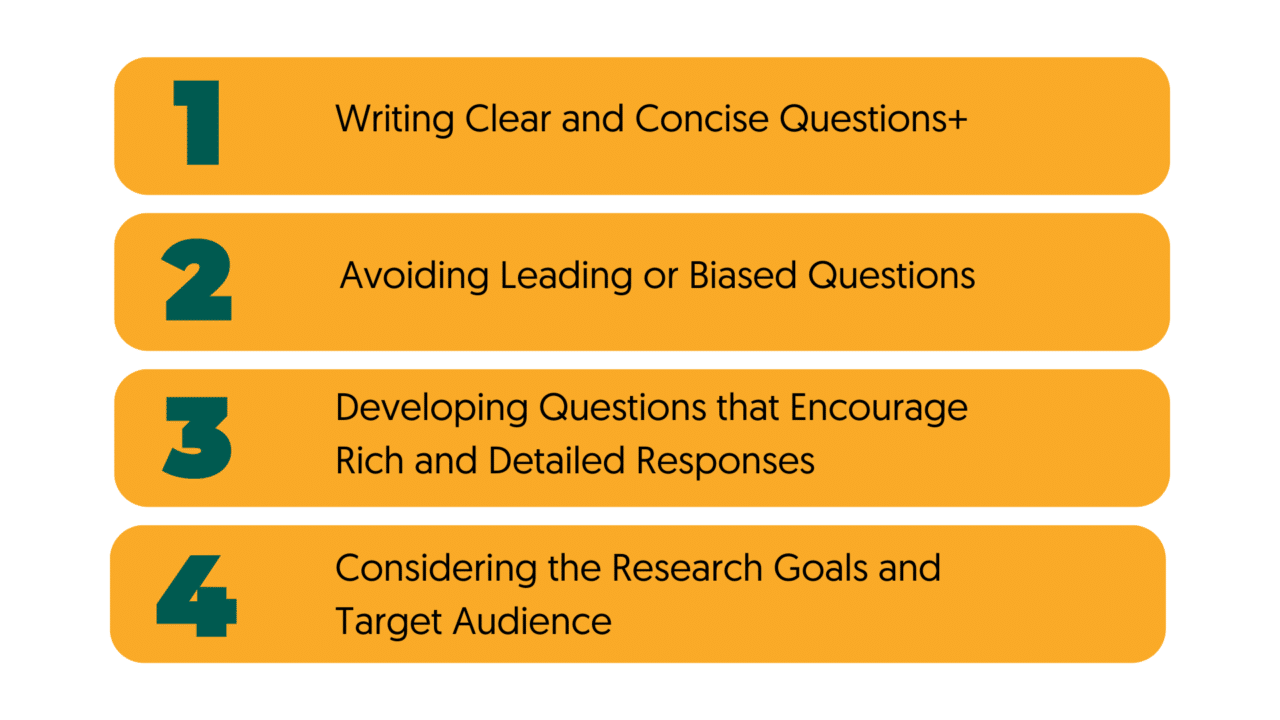

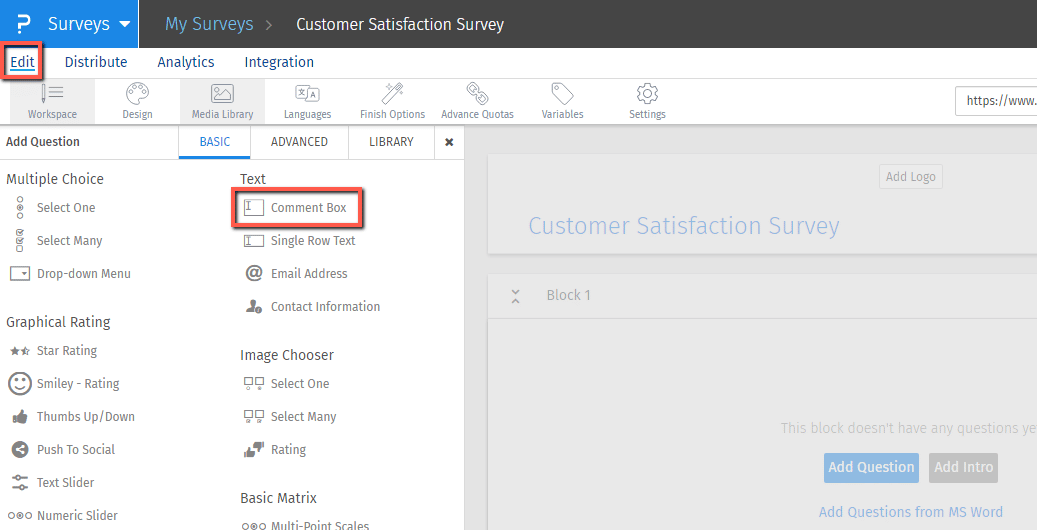

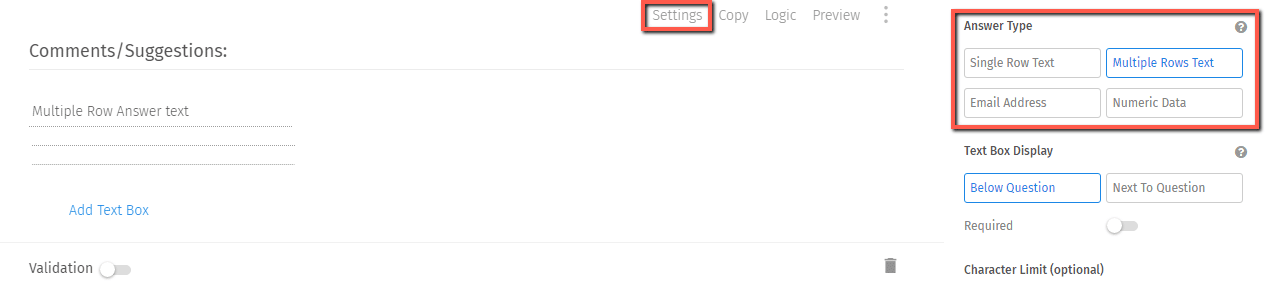

Designing open-ended questions requires careful consideration and planning. Open-ended questions elicit more than just a simple “yes” or “no” response and instead allow for a broad range of answers that provide insight into the respondent’s thoughts, feelings, or experiences. When designing open-ended questions in qualitative research, it is critical to consider the best practices below:

Before designing your questions, you must predetermine what you want to learn from your respondents. This, in turn, will help you craft clear and concise questions that are relevant to your research goals. Use simple language and avoid technical terms or jargon that might confuse respondents.

Avoid leading or biased language that could influence and limit the respondents’ answers. Instead, use neutral wording that allows participants to share their authentic thoughts and opinions. For example, instead of asking, “Did you enjoy the food you ate?” ask, “What was your experience at the restaurant?”

One of the advantages of open-ended questions is that they allow respondents to provide detailed and personalized responses. Encourage participants to elaborate on their answers by asking follow-up questions or probing for additional information.

One can deliver open-ended questions in various formats, including interviews, surveys, and focus groups. Consider which one is most appropriate for your research goals and target audience. Additionally, before using your questions in a survey or interview, test them with a small group of people to make sure they are clear and functional.

Open-ended questions give a participant the freedom to answer without restriction. Furthermore, these questions evoke detailed responses from participants, unlike close-ended questions that tend to lead to one-word answers.

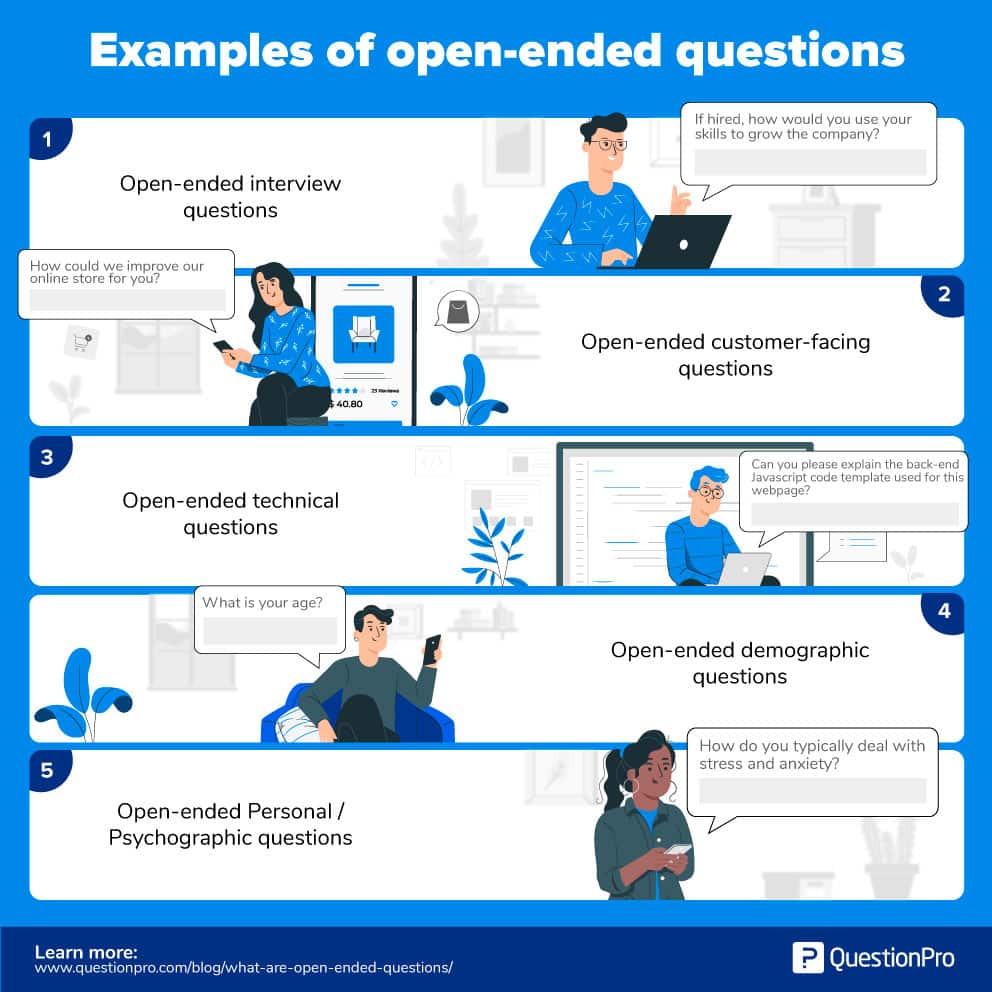

Open-Ended Questions Categories

When a researcher wants to explore a topic or phenomenon that is not well understood, qualitative research can help generate hypotheses and insights. For instance, “Can you tell me more about your thoughts on animal poaching in Africa?” or “What is your opinion on the future of social media in business?”

Researchers use these questions to prompt respondents to think more deeply about a particular topic or experience, sometimes using anecdotes related to a specific topic. For example, “What did you learn from that experience?” or “How do you think you could have handled that situation differently?

Researchers use probing questions to gain deeper insight into a participant’s response. These questions aim to understand the reasoning and emotion behind a particular answer. For example, “What did you learn from that mistake?” or “How do you think you could have handled that situation differently?

These questions get more information or clarify a point. For example, “Can you explain that further?” or “Can you give me an example?”

These questions ask the respondents to imagine a hypothetical scenario and provide their thoughts or reactions. Examples of hypothetical questions include “What would you do if you won the lottery?” or “How do you think society would be different if everyone had access to free healthcare?”

These questions ask the respondent to describe something in detail, such as a person, place, or event. Examples of descriptive questions include “Can you tell me about your favorite vacation?” or “How would you describe your ideal job?”

When preparing for an interview , it is important to understand the types of interviews available, what topics will be covered, and how to ask open-ended questions.

Questions should be asked in terms of past, present, and future experiences and should be worded in such a way as to invite a more detailed response from the participant. It is also important to establish a clear sequence of questions so that all topics are addressed without interrupting the flow of conversation.

Planning and Preparing For Interviews and Focus Groups

Before starting an interview or focus group, creating a list of topics or areas you want to explore during your research is essential. Consider what questions will help you gain the most insight into the topic.

Once you’ve identified the topics, you can create more specific questions that will be used to guide the conversation. It can be helpful to categorize your questions into themes to ensure all topics are addressed during the interview.

As you write your questions, aim to keep them as open-ended as possible so that the participant has space to provide detailed feedback. Avoid leading questions and try to avoid yes or no answers. Also, allow participants to provide any additional thoughts they may have on the topic.

Let’s say you’re researching customer experience with an online store. Your broad topic categories might be customer service, product selection, ease of use, and shipping. Your questions could cover things like:

- How satisfied are you with the customer service?

- What do you think about the product selection?

- Is it easy to find the products you’re looking for?

Best Practices

During the conversation, only one person can talk at a time, and everyone should be able to contribute. To ensure participants understand the questions being asked, try asking them in multiple ways.

It is also important to pause briefly and review the question that has just been discussed before moving on. In addition, brief pauses and silences before and after asking a new question may help facilitate the discussion. If participants begin talking about something that may be an answer to a different question during the discussion, then feel free to allow the conversation to go in that direction.

With these strategies, examples, and best practices in mind, you can ensure that your interviews and focus groups are successful.

Tips For Asking Open-Ended Questions During Interviews and Focus Groups

Asking open-ended questions during interviews and focus groups is critical to qualitative research. Open-ended questions allow you to explore topics in-depth, uncover deeper insights, and gain valuable participant feedback.

However, crafting your questions with intention and purpose is important to ensure that you get the most out of your research.

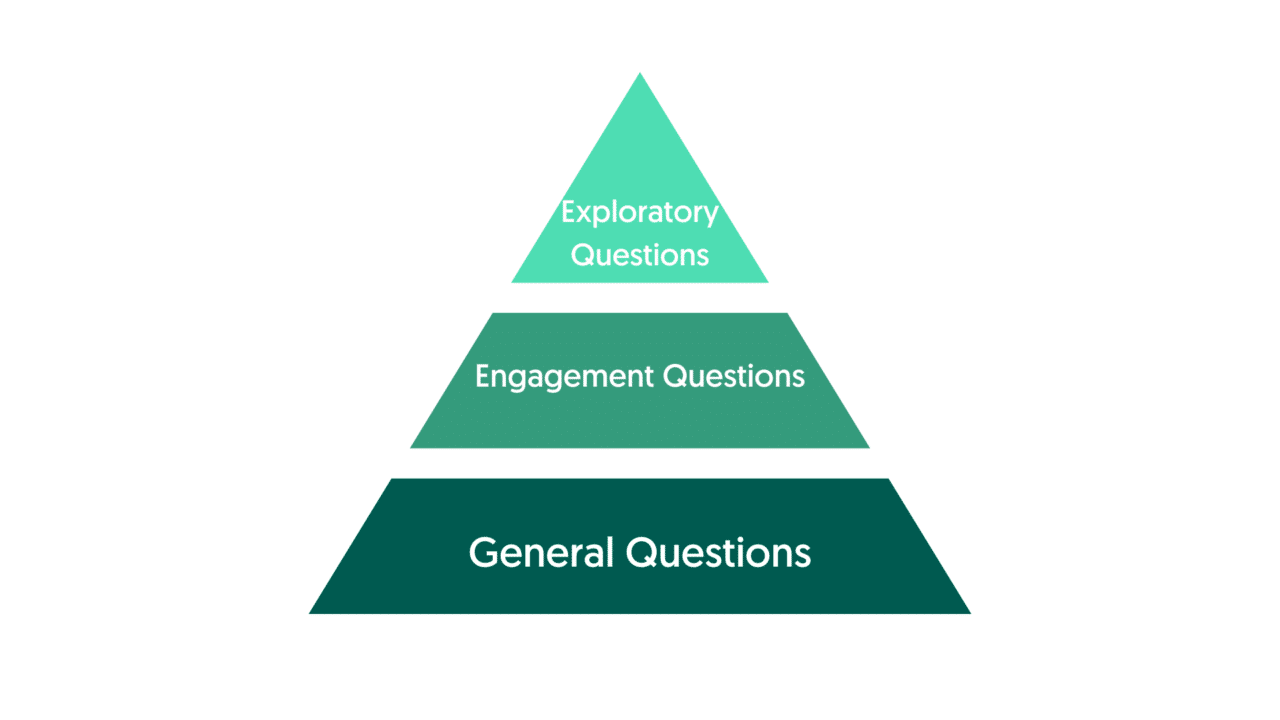

Start With General Questions

When crafting open-ended questions for interviews or focus groups, it’s important to start with general questions and move towards more specific ones. This strategy helps you uncover various perspectives and ideas before getting into the details.

Using neutral language helps to avoid bias and encourages honest answers from participants. It’s important to determine the goal of the focus group or interview before asking any questions. These findings will help guide your conversation and keep it on track.

Use of Engagement Questions

To get the conversation started during interviews or focus groups, engagement questions are a great way to break the ice. These types of questions can be about anything from personal experiences to interests.

For example: “How did you get here, and what was one unusual thing you saw on your way in?”, “What do you like to do to unwind in your free time?” or “When did you last purchase a product from this line?”.

Use of Exploratory Questions

Exploratory questions about features are also useful in this type of research. Questions such as: “What features would you talk about when recommending this product to a friend?”, “If you could change one thing about this product, what would you change?”, or “Do you prefer this product or that product, and why?” all help to uncover participants’ opinions and preferences.

Exploratory questions about experiences are also helpful; questions such as: “Tell me about a time you experienced a mishap when using this product?” help to identify potential problems that need to be addressed.

Researchers can gain valuable insights from participants by using these tips for asking open-ended questions during interviews and focus groups.

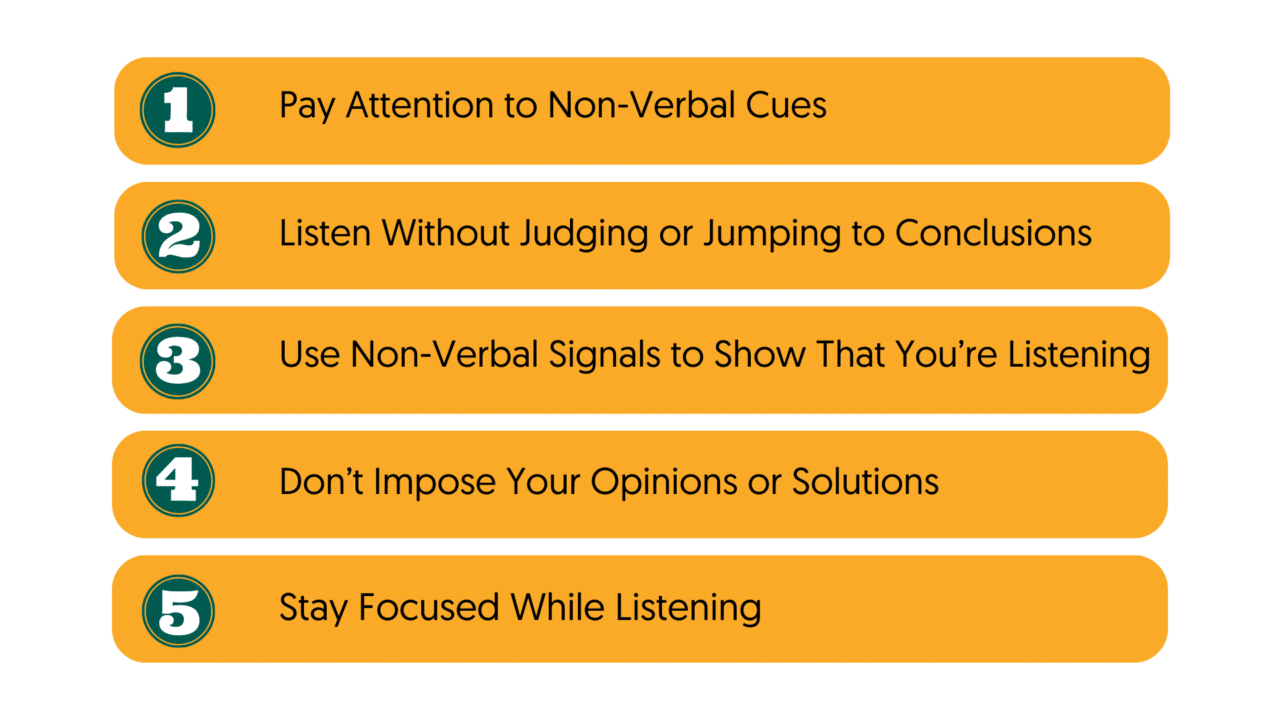

Strategies For Active Listening and Follow-Up Questioning

Active listening is an important skill to possess when conducting qualitative research. It’s essential to ensure you understand and respond to the person you are interviewing effectively. Here are some strategies for active listening and follow-up questioning:

Pay Attention to Non-Verbal Cues

It is important to pay attention to non-verbal cues such as body language and voice when listening. Pay attention to their facial expressions and tone of voice to better understand what they are saying. Make sure not to interrupt the other person, as this can make them feel like their opinions aren’t being heard.

Listen Without Judging or Jumping to Conclusions

It is important to listen without judgment or jumping to conclusions. Don’t plan what to say next while listening, as this will stop you from understanding what the other person is saying.

Use Non-Verbal Signals to Show That You’re Listening

Nodding, smiling, and making small noises like “yes” and “uh huh” can show that you are listening. These signals can help the person feel more comfortable and open up more.

Don’t Impose Your Opinions or Solutions

When interviewing someone, it is important not to impose your opinions or solutions. It is more important to understand the other person and try to find common ground than it is to be right.

Stay Focused While Listening

Finally, it is critical to stay focused while listening. Don’t let yourself get distracted by your own thoughts or daydreaming. Remain attentive and listen with an open mind.

These are all key elements in effectively gathering data and insights through qualitative research.

Qualitative research depends on understanding the context and content of the responses to open-ended questions. Analyzing and interpreting these responses can be challenging for researchers, so it’s important to have a plan and strategies for getting the most value out of open-ended responses.

Strategies For Coding and Categorizing Responses

Coding qualitative data categorizes and organizes responses to open-ended questions in a research study. It is an essential part of the qualitative data analysis process and helps identify the responses’ patterns, themes, and trends.

Thematic Analysis and Qualitative Data Analysis Software

These are two methods for automated coding of customer feedback. Thematic analysis is the process of identifying patterns within qualitative data. This process can be done by manually sorting through customer feedback or using a software program to do the work for you.

Qualitative data analysis software also facilitates coding by providing powerful visualizations that allow users to identify trends and correlations between different customer responses.

Manual Coding

Manual coding is another method of coding qualitative data, where coders sort through responses and manually assign labels based on common themes. Coding the qualitative data, it makes it easier to interpret customer feedback and draw meaningful conclusions from it.

Coding customer feedback helps researchers make data-driven decisions based on customer satisfaction. It helps quantify the common themes in customer language, making it easier to interpret and analyze customer feedback accurately.

Strategies for manual coding include using predetermined codes for common words or phrases and assigning labels to customers’ responses according to certain categories. Examples of best practices for coding include using multiple coders to review responses for accuracy and consistency and creating a library of codes for ease of use.

Identifying Themes and Patterns in Responses

These processes involve reviewing the responses and searching for commonalities regarding words, phrases, topics, or ideas. Doing so can help researchers to gain a better understanding of the material they are analyzing.

There are several strategies that researchers can use when it comes to identifying themes and patterns in open-ended responses.

Manual Scan

One strategy is manually scanning the data and looking for words or phrases that appear multiple times.

Automatic Scan

Another approach is to use qualitative analysis software that can provide coding, categorization, and data analysis.

For example, if a survey asked people about their experience with a product, a researcher could look for common phrases such as “it was easy to use” or “I didn’t like it.” The researcher could then look for patterns regarding how frequently these phrases were used.

Concept Indicator Model

This model is an important part of the coding process in classic grounded theory. It involves a continuous process of exploring and understanding open-ended responses, which can often lead to the development of new conceptual ideas.

Coding Process

The coding process is broken down into two parts: substantive coding and theoretical coding. Substantive coding involves organizing data into meaningful categories, while theoretical coding looks at how those categories relate.

Forms of Coding

Within the concept indicator model are two forms of coding: open coding and selective coding. Open coding is used to explore responses without predetermined theories or preconceived ideas. It is an iterative process involving connecting categories and generating tentative conclusions.

On the other hand, selective coding uses predetermined theories or ideas to guide data analysis.

The concept indicator model also uses a cycling approach known as constant comparison and theoretical sampling. Constant comparison is the process of constantly comparing new data with previous data until saturation is reached.

Theoretical sampling involves examining different data types to determine which ones will be more useful for exploring the concepts and relationships under investigation.

Gaining experience and confidence in exploring and confirming conceptual ideas is essential for success in the concept indicator model.

Strategies such as brainstorming and creating examples can help analysts better understand the various concepts that emerge from the data.

Best practices such as involving multiple coders in the process, triangulating data from different sources, and including contextual information can also help increase the accuracy and reliability of coding results.

Interpreting and Analyzing Open-Ended Responses in Relation to Your Research Questions

- Ensure Objectives are Met: For any study or project, you must ensure your objectives are met. To achieve this, the responses to open-ended questions must be categorized according to their subject, purpose, and theme. This step will help in recognizing patterns and drawing out commonalities.

- Choose A Coding Method: Once you have identified the themes, you must choose a coding method to interpret and analyze the data.

There are various coding strategies that can be employed. For example, a directed coding strategy will help you focus on the themes you have identified in your research objectives. In contrast, an axial coding method can be used to connect related concepts together. With a coding method, it will be easier to make sense of the responses.

Use Narrative Analysis

This process involves looking for story elements such as plot, characters, setting, and conflict in the text. It can be useful for identifying shared experiences or values within a group.

By looking for these narrative elements, you can better understand how individuals perceive their own experiences and those of others.

Analyze the Findings

However, to understand the meanings that the responses may have, it is also important to analyze them. This stage is where techniques such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and textual analysis come in.

These methods provide valuable insights into how the responses are related to each other and can help uncover potential connections and underlying motivations.

Summarize Your Findings

Once you have interpreted and analyzed the data, it is time to decide on your key findings. For example, you can summarize your findings according to different themes, discuss any implications of your research or suggest ways in which further research can be carried out.

These strategies provide valuable insights into the qualitative data collected from open-ended questions. However, to ensure that the data’s most effective outcomes are obtained, you need to familiarize yourself with the best practices in qualitative research.

Open-ended questions have the potential to generate rich and nuanced data in qualitative research. However, they also present certain challenges and limitations that researchers and educators need to be aware of.

We will now explore some of the challenges associated with using open-ended questions, including potential biases and subjectivity in responses, social desirability bias, and response bias.

We will also discuss strategies to address these challenges, such as balancing open-ended and closed-ended questions in research design. By understanding these limitations and employing best practices, researchers and educators can use open-ended questions to gather meaningful data and insights.

Addressing potential biases and subjectivity in responses

When we use open-ended questions in qualitative research, it’s crucial to be mindful of potential biases and subjectivity in responses. It’s natural for participants to bring their own experiences and beliefs to the table, which can impact their answers and skew the data. To tackle these challenges, we can take several steps to ensure that our research findings are as accurate and representative as possible.

One way to minimize subjectivity is to use neutral and unbiased language when framing our questions. By doing so, we can avoid leading or loaded questions that could influence participants’ responses. We can also use multiple methods to verify data and check responses, like conducting follow-up interviews or comparing responses with existing literature.

Another important consideration is to be open and transparent about the research process and participants’ rights. Addressing these biases also includes providing informed consent and guaranteeing confidentiality so that participants feel comfortable sharing their genuine thoughts and feelings. By recruiting diverse participants and ensuring that our data is representative and inclusive, we can also reduce potential biases and increase the validity of our findings.

By tackling biases and subjectivity in responses head-on, we can gather reliable and insightful data that can inform future research and enhance teaching methods.

Dealing with social desirability bias and response bias

In qualitative research, social desirability bias and response bias can pose significant challenges when analyzing data. Social desirability bias occurs when participants tend to respond in ways that align with social norms or expectations, rather than expressing their true feelings or beliefs. Response bias, on the other hand, happens when participants provide incomplete or inaccurate information due to factors like memory lapse or misunderstanding of the question.

To address these biases, researchers can use various strategies to encourage participants to be more candid and honest in their responses.

For instance, researchers can create a safe and supportive environment that fosters trust and openness, allowing participants to feel comfortable sharing their true thoughts and experiences. Researchers can also use probing techniques to encourage participants to elaborate on their answers, helping to uncover underlying beliefs and attitudes.

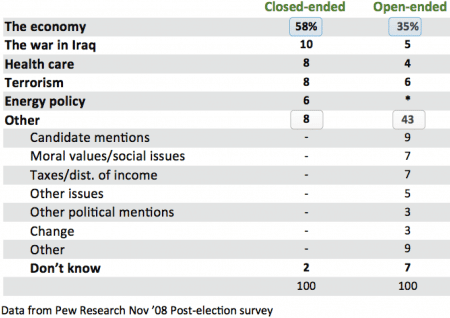

It’s also a good idea to mix up the types of questions you ask, utilizing both open-ended and closed-ended inquiries to get a variety of responses. Closed-ended questions can aid in the verification or confirmation of participants’ comments, but open-ended questions allow for a more in-depth investigation of themes and encourage participants to submit extensive and personal responses.

Balancing open-ended and closed-ended questions in your research design

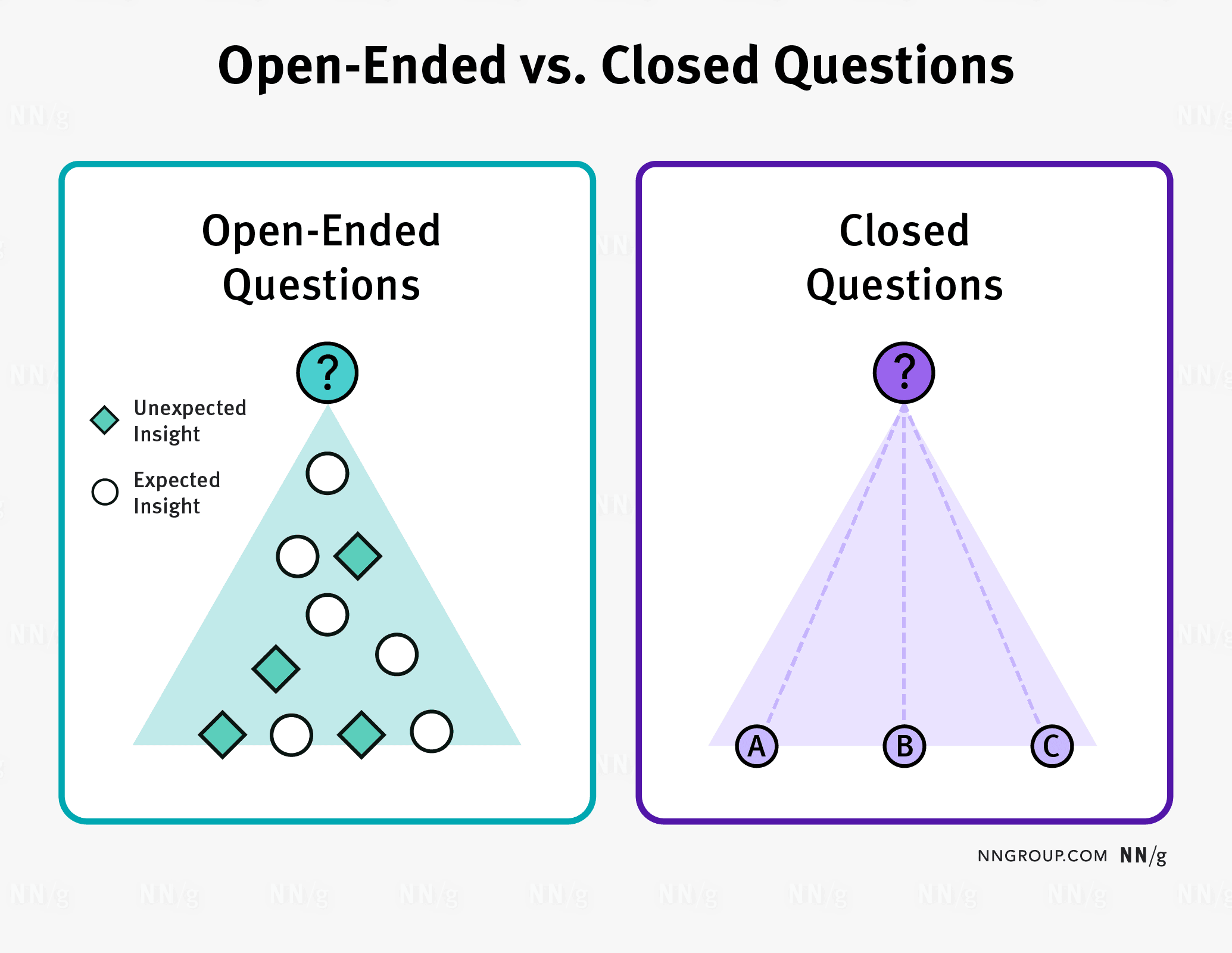

An appropriate combination of open-ended and closed-ended questions is essential for developing an effective research design. Open-ended questions allow participants to provide detailed, nuanced responses and offer researchers the opportunity to uncover unexpected insights.

However, too many open-ended questions can make analysis challenging and time-consuming. Closed-ended questions, on the other hand, can provide concise and straightforward data that’s easy to analyze but may not capture the complexity of participants’ experiences.

Balancing the use of open-ended and closed-ended questions necessitates a careful evaluation of the study objectives, target audience, and issue under examination. Researchers must also consider the available time and resources for analysis.

When designing a research study, it’s essential to prioritize the research goals and choose questions that align with those goals. Careful selection of questions guarantees that the data gathered is pertinent and adds to a greater knowledge of the topic under consideration. Researchers should also consider the participants’ backgrounds and experiences and select questions that are appropriate and sensitive to their needs. Furthermore, adopting a mix of open-ended and closed-ended questions can assist researchers in triangulating data, which allows them to cross-validate their findings by comparing results from multiple sources or techniques.

Lastly, we will be exploring the best practices for utilizing open-ended questions in qualitative research. We cover a range of helpful tips and strategies for creating a research design that fosters rich and nuanced data while maintaining the integrity of your research.

Building an effective connection with your research participants, developing carefully developed research questions that align with your research objectives, remaining flexible and adaptable in your approach, and prioritizing ethical considerations throughout your research process are some of the key best practices we explore.

Building Rapport with Participants

Building rapport with research participants is an essential component of conducting effective qualitative research. Building rapport is all about creating trust and providing a comfortable environment where participants can feel free to share their thoughts and experiences.

The first thing a researcher should do is to introduce themselves and make the participant understand why the research is significant. Additionally, active listening is critical in building rapport. Listening attentively to your participants’ responses and asking follow-up questions can demonstrate your interest in their experiences and perspective.

Maintaining a nonjudgmental, impartial position is also essential in developing rapport. Participants must feel free to express their opinions and experiences without fear of being judged or prejudiced.

Using respectful language, maintaining eye contact, and nodding along to participants’ responses can show that you are invested in their stories and care about their experiences.

Overall, establishing rapport with participants is an ongoing process that requires attention, care, and empathy.

Developing clear research questions

In research, developing clear research questions is an essential component of qualitative research using open-ended questions. The research questions provide a clear direction for the research process, enabling researchers to gather relevant and insightful data.

To create effective research questions, they must be specific, concise, and aligned with the overall research objectives. It is crucial to avoid overly broad or narrow questions that could impact the validity of the research.

Additionally, researchers should use language that is easy to understand. Researchers should avoid any technical jargon that may lead to confusion.

The order of the questions is also significant; they should flow logically, building on each other and ensuring they make sense. By developing clear research questions, researchers can collect and analyze data in a more effective and meaningful manner.

Maintaining a flexible and adaptable approach

When conducting qualitative research, maintaining a flexible and adaptable approach is crucial. Flexibility enables researchers to adjust their research methods and questions to ensure they capture rich and nuanced data that can answer their research questions.

However, staying adaptable can be a daunting task, as researchers may need to modify their research approach based on participants’ responses or unforeseen circumstances.

To maintain flexibility, researchers must have a clear understanding of their research questions and goals, while also remaining open to modifying their methods if necessary. It is also essential to keep detailed notes and regularly reflect on research progress to determine if adjustments are needed.

Staying adaptable is equally important as it requires researchers to be responsive to changes in participants’ attitudes and perspectives. Being able to pivot research direction and approach based on participant feedback is critical to achieving accurate and meaningful results.

Maintaining a flexible and adaptive strategy allows researchers to collect the most extensive and accurate data possible, resulting in a more in-depth understanding of the research topic. While it can be challenging to remain flexible and adaptable, doing so will ultimately lead to more robust research findings and greater insights into the topic at hand.

Being aware of ethical considerations

When conducting research, It is critical to remember the ethical aspects that control how individuals interact with one another in society and how these factors affect research. Ethical considerations refer to the principles or standards that should guide research to ensure it is conducted in an honest, transparent, and respectful manner.

Before beginning the study, researchers must obtain informed consent from participants. Obtaining consent means providing clear and comprehensive information about the research, its purpose, what participation entails, and the potential risks and benefits. Researchers must ensure that participants understand the information and voluntarily consent to participate.

Protecting the privacy and confidentiality of participants must be essential for researchers. They should look into safeguarding personal information, using pseudonyms or codes to protect identities, and securing any identifying information collected.

Researchers must avoid asking questions that are too personal, sensitive, or potentially harmful. If harm or distress occurs, researchers should provide participants with appropriate support and referral to relevant services.

Using open-ended questions in qualitative research presents both challenges and benefits. To address potential limitations, researchers should remain objective and neutral, create a safe and non-judgmental space, and use probing techniques. Best practices include building rapport, developing clear research questions, and being flexible. Open-ended questions offer the benefits of revealing rich and nuanced data, allowing for flexibility, and building rapport with participants. Ethical considerations must also be a top priority.

Interesting topics

- How to add subtitles to a video? Fast & Easy

- Subtitles, Closed Captions, and SDH Subtitles: How are they different?

- Why captions are important? 8 good reasons

- What is an SRT file, how to create it and use it in a video?

- Everything You Need for Your Subtitle Translation

- Top 10 Closed Captioning and Subtitling Services 2023

- The Best Font for Subtitles : our top 8 picks!

- Davinci Resolve

- Adobe After Effects

- Final Cut Pro X

- Adobe Premiere Rush

- Canvas Network

- What is Transcription

- Interview Transcription

- Transcription guidelines

- Audio transcription using Google Docs

- MP3 to Text

- How to transcribe YouTube Videos

- Verbatim vs Edited Transcription

- Legal Transcriptions

- Transcription for students

- Transcribe a Google hangouts meeting

- Best Transcription Services

- Best Transcription Softwares

- Save time research interview transcription

- The best apps to record a phone call

- Improve audio quality with Adobe Audition

- 10 best research tools every scholar should use

- 7 Tips for Transcription in Field Research

- Qualitative and Quantitative research

- Spotify Podcast Guideline

- Podcast Transcription

- How to improve your podcasting skills

- Convert podcasts into transcripts

- Transcription for Lawyers: What is it and why do you need it?

- How transcription can help solve legal challenges

- The Best Transcription Tools for Lawyers and Law Firms

- Panelist area

- Become a panelist

Qualitative research: open-ended and closed-ended questions

Our guide to market research can be downloaded free of charge

From a very young age, we have been taught what open-ended , and closed-ended questions are. How are these terms applied to qualitative research methods , and in particular to interviews?

Kathryn J. Roulston reveals her definitions of an open-ended and closed-ended question in qualitative interviews in the SAGE Encyclopedia on Qualitative Research Methods . If you want to better understand how qualitative methods fit within a market research approach, we suggest you take a look at our step-by-step guide to market research which can be downloaded in our white papers section (free of charge and direct; we won’t ask you any contact details first).

credits : Shutterstock

Only for our subscribers: exclusive analyses and marketing advice

"I thought the blog was good. But the newsletter is even better!"

Introduction

- Closed-ended question

- Open-ended question

Examples of closed and open-ended questions for satisfaction research

Examples of closed and open-ended questions for innovation research, some practical advice.

Let us begin by pointing out that open and closed-ended questions do not at first glance serve the same purpose in market research. Instead, open-ended questions are used in qualitative research (see the video above for more information) and closed-ended questions are used in quantitative research. But this is not an absolute rule.

In this article, you will, therefore, discover the definitions of closed and open-ended questions. We will also explain how to use them. Finally, you will find examples of how to reformulate closed-ended questions into open-ended questions in the case of :

- satisfaction research

- innovation research

Essential elements to remember

Open-ended questions:

- for qualitative research (interviews and focus groups)

- very useful in understanding in detail the respondent and his or her position concerning a defined topic/situation

- particularly helpful in revealing new aspects , sub-themes, issues, and so forth that are unknown or unidentified

Closed-ended questions:

- for quantitative research (questionnaires and surveys)

- suitable for use with a wide range of respondents

- allow a standardised analysis of the data

- are intended to confirm the hypotheses (previously stated in the qualitative part)

A closed-ended question

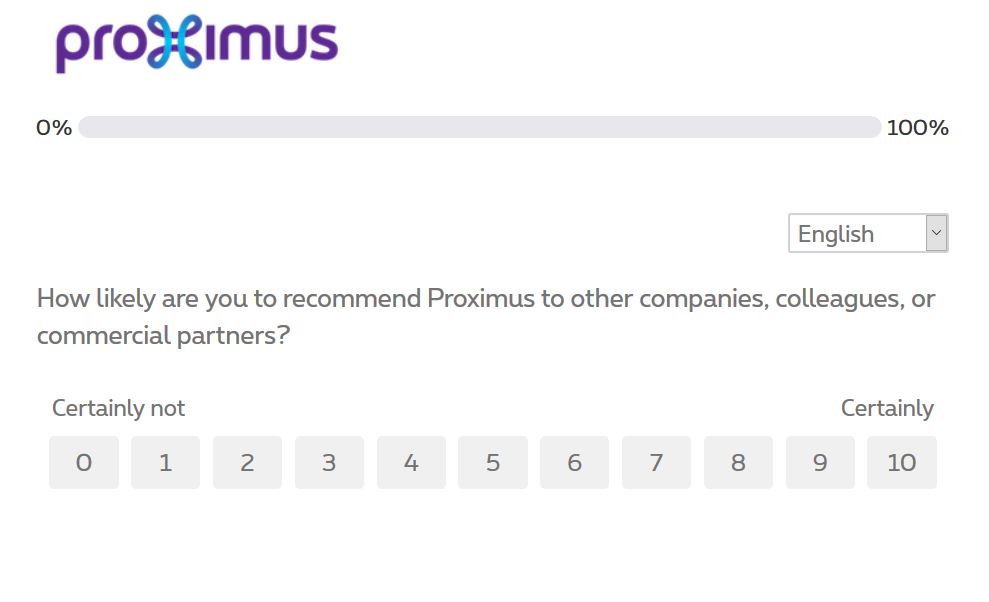

A closed-ended question offers, as its name suggests, a limited number of answers. For example, the interviewee may choose a response from a panel of given proposals or a simple “yes” or “no”. They are intended to provide a precise, clearly identifiable and easily classified answer.

This type of question is used in particular during interviews whose purpose is to be encoded according to pre-established criteria. There is no room for free expression, as is the case for open-ended questions. Often, this type of question is integrated into 1-to-1 interview guides and focus groups and allows the interviewer to collect the same information from a wide range of respondents in the same format. Indeed, closed-ended questions are designed and oriented to follow a pattern and framework predefined by the interviewer.

Two forms of closed-ended questions were identified by the researchers: specific closed-ended questions , where respondents are offered choice answers, and implicit closed-ended questions , which include assumptions about the answers that can be provided by respondents.

A specific closed-ended question would be formulated as follows, for example: “how many times a week do you eat pasta: never, once or twice a week, 3 to 4 times, 5 times a week or more?” The adapted version in the form of an implicit closed-ended question would be formulated as follows: “how many times a week do you eat pasta? ». The interviewer then assumes that the answers will be given in figures.

The Net Promoter Score (or NPS) is an example of closed question (see example above)

While some researchers consider the use of closed-ended questions to be restrictive, others see in these questions – combined with open-ended questions – the possibility of generating different data for analysis. How these closed-ended questions can be used, formulated, sequenced, and introduced in interviews depends heavily upon the studies and research conducted upstream.

Read also Creating a questionnaire for quantitative market research

In what context are closed-ended questions used?

- Quantitative research (tests, confirmation of the qualitative research and so on).

- Research with a large panel of respondents (> 100 people)

- Recurrent research whose results need to be compared

- When you need confirmation, and the possible answers are limited in effect

An open-ended question

An open-ended question is a question that allows the respondent to express himself or herself freely on a given subject. This type of question is, as opposed to closed-ended questions, non-directive and allows respondents to use their own terms and direct their response at their convenience.

Open-ended questions, and therefore without presumptions, can be used to see which aspect stands out from the answers and thus could be interpreted as a fact, behaviour, reaction, etc. typical to a defined panel of respondents.

For example, we can very easily imagine open-ended questions such as “describe your morning routine”. Respondents are then free to describe their routine in their own words, which is an important point to consider. Indeed, the vocabulary used is also conducive to analysis and will be an element to be taken into account when adapting an interview guide, for example, and/or when developing a quantitative questionnaire.

As we detail in our market research whitepaper , one of the recommendations to follow when using open-ended questions is to start by asking more general questions and end with more detailed questions. For example, after describing a typical day, the interviewer may ask for clarification on one of the aspects mentioned by the respondent. Also, open-ended questions can also be directed so that the interviewee evokes his or her feelings about a situation he or she may have mentioned earlier.

In what context are open-ended questions used?

- Mainly in qualitative research (interviews and focus groups)

- To recruit research participants

- During research to test a design, a proof-of-concept, a prototype, and so on, it is essential to be able to identify the most appropriate solution.

- Analysis of consumers and purchasing behaviour

- Satisfaction research , reputation, customer experience and loyalty research, and so forth.

- To specify the hypotheses that will enable the quantitative questionnaire to be drawn up and to propose a series of relevant answers (to closed-ended questions ).

It is essential for the interviewer to give respondents a framework when using open-ended questions. Without this context, interviewees could be lost in the full range of possible responses, and this could interfere with the smooth running of the interview. Another critical point concerning this type of question is the analytical aspect that follows. Indeed, since respondents are free to formulate their answers, the data collected will be less easy to classify according to fixed criteria.

The use of open-ended questions in quantitative questionnaires

Rules are made to be broken; it is well known. Most quantitative questionnaires, therefore, contain free fields in which the respondent is invited to express his or her opinions in a more “free” way. But how to interpret these answers?

When the quantity of answers collected is small (about ten) it will be easy to proceed manually, possibly by coding (for more information on the coding technique, go here ). You will thus quickly identify the main trends and recurring themes.

On the other hand, if you collect hundreds or even thousands of answers, the analysis of these free answers will be much more tedious. How can you do it? In this case, we advise you to use a semantic analysis tool. This is most often an online solution, specific to a language, which is based on an NLP (Natural Language Processing) algorithm. This algorithm will, very quickly, analyse your corpus and bring out the recurring themes . It is not a question here of calculating word frequencies, but instead of working on semantics to analyse the repetition of a subject.

Of course, the use of open-ended questions in interviews does not exclude the use of closed-ended questions. Alternating these two types of questions in interviews, whether 1-to-1 interviews, group conversations or focus groups, is conducive not only to maintaining a specific dynamic during the interview but also to be able to frame specific responses while leaving certain fields of expression free. In general, it is interesting for the different parties that the interview ends with an open-ended question where the interviewer asks the interviewee if he or she has anything to add or if he or she has any questions.

In this type of research, you confront the respondent with a new, innovative product or service. It is therefore important not to collect superficial opinions but to understand in depth the respondent’s attitude towards the subject of the market research.

As you will have understood, open-ended questions are particularly suitable for qualitative research (1-to-1 interviews and focus groups). How should they be formulated?

The Five W’s; (who did what, where, when, and why ) questioning method should be used rigorously and sparingly :

- Who? Who? What? Where? When? How? How much? “are particularly useful for qualitative research and allow you to let your interlocutor develop and elaborate a constructed and informative answer.

- Use the CIT (Critical Incident Technique) method with formulations that encourage your interviewer to go into the details of an experience: “Can you describe/tell me…? “, ” What did you feel? “, ” According to you… “

- Avoid asking “Why?”: this question may push the interviewer into a corner, and the interviewer may seek logical reasoning for his or her previous answer. Be gentle with your respondents by asking them to tell you more, to give you specific examples, for example.

In contrast, closed-ended questions are mainly used and adapted to quantitative questionnaires since they facilitate the analysis of the results by framing the participants’ answers.

Image: Shutterstock

- Market research methods

19 July 2021

Very useful sir….

Post your opinion

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Don't forget to check your spam folder .

You didn't receive the link?

Pour offrir les meilleures expériences, nous utilisons des technologies telles que les cookies pour stocker et/ou accéder aux informations des appareils. Le fait de consentir à ces technologies nous permettra de traiter des données telles que le comportement de navigation ou les ID uniques sur ce site. Le fait de ne pas consentir ou de retirer son consentement peut avoir un effet négatif sur certaines caractéristiques et fonctions.

Qualitative Study

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Nebraska Medical Center

- 2 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting

- 3 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting/McLaren Macomb Hospital

- PMID: 29262162

- Bookshelf ID: NBK470395

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervene or introduce treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypotheses as well as further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a stand-alone study, purely relying on qualitative data or it could be part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and application of qualitative research.

Qualitative research at its core, ask open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers such as ‘how’ and ‘why’. Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions at hand, qualitative research design is often not linear in the same way quantitative design is. One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be difficult to accurately capture quantitatively, whereas a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a certain time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify and it is important to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore ‘compete’ against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each, qualitative and quantitative work are not necessarily opposites nor are they incompatible. While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites, and they are certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined that there is a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated together.

Examples of Qualitative Research Approaches

Ethnography

Ethnography as a research design has its origins in social and cultural anthropology, and involves the researcher being directly immersed in the participant’s environment. Through this immersion, the ethnographer can use a variety of data collection techniques with the aim of being able to produce a comprehensive account of the social phenomena that occurred during the research period. That is to say, the researcher’s aim with ethnography is to immerse themselves into the research population and come out of it with accounts of actions, behaviors, events, etc. through the eyes of someone involved in the population. Direct involvement of the researcher with the target population is one benefit of ethnographic research because it can then be possible to find data that is otherwise very difficult to extract and record.

Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory is the “generation of a theoretical model through the experience of observing a study population and developing a comparative analysis of their speech and behavior.” As opposed to quantitative research which is deductive and tests or verifies an existing theory, grounded theory research is inductive and therefore lends itself to research that is aiming to study social interactions or experiences. In essence, Grounded Theory’s goal is to explain for example how and why an event occurs or how and why people might behave a certain way. Through observing the population, a researcher using the Grounded Theory approach can then develop a theory to explain the phenomena of interest.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is defined as the “study of the meaning of phenomena or the study of the particular”. At first glance, it might seem that Grounded Theory and Phenomenology are quite similar, but upon careful examination, the differences can be seen. At its core, phenomenology looks to investigate experiences from the perspective of the individual. Phenomenology is essentially looking into the ‘lived experiences’ of the participants and aims to examine how and why participants behaved a certain way, from their perspective . Herein lies one of the main differences between Grounded Theory and Phenomenology. Grounded Theory aims to develop a theory for social phenomena through an examination of various data sources whereas Phenomenology focuses on describing and explaining an event or phenomena from the perspective of those who have experienced it.

Narrative Research

One of qualitative research’s strengths lies in its ability to tell a story, often from the perspective of those directly involved in it. Reporting on qualitative research involves including details and descriptions of the setting involved and quotes from participants. This detail is called ‘thick’ or ‘rich’ description and is a strength of qualitative research. Narrative research is rife with the possibilities of ‘thick’ description as this approach weaves together a sequence of events, usually from just one or two individuals, in the hopes of creating a cohesive story, or narrative. While it might seem like a waste of time to focus on such a specific, individual level, understanding one or two people’s narratives for an event or phenomenon can help to inform researchers about the influences that helped shape that narrative. The tension or conflict of differing narratives can be “opportunities for innovation”.

Research Paradigm

Research paradigms are the assumptions, norms, and standards that underpin different approaches to research. Essentially, research paradigms are the ‘worldview’ that inform research. It is valuable for researchers, both qualitative and quantitative, to understand what paradigm they are working within because understanding the theoretical basis of research paradigms allows researchers to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the approach being used and adjust accordingly. Different paradigms have different ontology and epistemologies . Ontology is defined as the "assumptions about the nature of reality” whereas epistemology is defined as the “assumptions about the nature of knowledge” that inform the work researchers do. It is important to understand the ontological and epistemological foundations of the research paradigm researchers are working within to allow for a full understanding of the approach being used and the assumptions that underpin the approach as a whole. Further, it is crucial that researchers understand their own ontological and epistemological assumptions about the world in general because their assumptions about the world will necessarily impact how they interact with research. A discussion of the research paradigm is not complete without describing positivist, postpositivist, and constructivist philosophies.

Positivist vs Postpositivist

To further understand qualitative research, we need to discuss positivist and postpositivist frameworks. Positivism is a philosophy that the scientific method can and should be applied to social as well as natural sciences. Essentially, positivist thinking insists that the social sciences should use natural science methods in its research which stems from positivist ontology that there is an objective reality that exists that is fully independent of our perception of the world as individuals. Quantitative research is rooted in positivist philosophy, which can be seen in the value it places on concepts such as causality, generalizability, and replicability.

Conversely, postpositivists argue that social reality can never be one hundred percent explained but it could be approximated. Indeed, qualitative researchers have been insisting that there are “fundamental limits to the extent to which the methods and procedures of the natural sciences could be applied to the social world” and therefore postpositivist philosophy is often associated with qualitative research. An example of positivist versus postpositivist values in research might be that positivist philosophies value hypothesis-testing, whereas postpositivist philosophies value the ability to formulate a substantive theory.

Constructivist

Constructivism is a subcategory of postpositivism. Most researchers invested in postpositivist research are constructivist as well, meaning they think there is no objective external reality that exists but rather that reality is constructed. Constructivism is a theoretical lens that emphasizes the dynamic nature of our world. “Constructivism contends that individuals’ views are directly influenced by their experiences, and it is these individual experiences and views that shape their perspective of reality”. Essentially, Constructivist thought focuses on how ‘reality’ is not a fixed certainty and experiences, interactions, and backgrounds give people a unique view of the world. Constructivism contends, unlike in positivist views, that there is not necessarily an ‘objective’ reality we all experience. This is the ‘relativist’ ontological view that reality and the world we live in are dynamic and socially constructed. Therefore, qualitative scientific knowledge can be inductive as well as deductive.”

So why is it important to understand the differences in assumptions that different philosophies and approaches to research have? Fundamentally, the assumptions underpinning the research tools a researcher selects provide an overall base for the assumptions the rest of the research will have and can even change the role of the researcher themselves. For example, is the researcher an ‘objective’ observer such as in positivist quantitative work? Or is the researcher an active participant in the research itself, as in postpositivist qualitative work? Understanding the philosophical base of the research undertaken allows researchers to fully understand the implications of their work and their role within the research, as well as reflect on their own positionality and bias as it pertains to the research they are conducting.

Data Sampling

The better the sample represents the intended study population, the more likely the researcher is to encompass the varying factors at play. The following are examples of participant sampling and selection:

Purposive sampling- selection based on the researcher’s rationale in terms of being the most informative.

Criterion sampling-selection based on pre-identified factors.

Convenience sampling- selection based on availability.

Snowball sampling- the selection is by referral from other participants or people who know potential participants.

Extreme case sampling- targeted selection of rare cases.

Typical case sampling-selection based on regular or average participants.

Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative research uses several techniques including interviews, focus groups, and observation. [1] [2] [3] Interviews may be unstructured, with open-ended questions on a topic and the interviewer adapts to the responses. Structured interviews have a predetermined number of questions that every participant is asked. It is usually one on one and is appropriate for sensitive topics or topics needing an in-depth exploration. Focus groups are often held with 8-12 target participants and are used when group dynamics and collective views on a topic are desired. Researchers can be a participant-observer to share the experiences of the subject or a non-participant or detached observer.

While quantitative research design prescribes a controlled environment for data collection, qualitative data collection may be in a central location or in the environment of the participants, depending on the study goals and design. Qualitative research could amount to a large amount of data. Data is transcribed which may then be coded manually or with the use of Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software or CAQDAS such as ATLAS.ti or NVivo.

After the coding process, qualitative research results could be in various formats. It could be a synthesis and interpretation presented with excerpts from the data. Results also could be in the form of themes and theory or model development.

Dissemination

To standardize and facilitate the dissemination of qualitative research outcomes, the healthcare team can use two reporting standards. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research or COREQ is a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is a checklist covering a wider range of qualitative research.

Examples of Application

Many times a research question will start with qualitative research. The qualitative research will help generate the research hypothesis which can be tested with quantitative methods. After the data is collected and analyzed with quantitative methods, a set of qualitative methods can be used to dive deeper into the data for a better understanding of what the numbers truly mean and their implications. The qualitative methods can then help clarify the quantitative data and also help refine the hypothesis for future research. Furthermore, with qualitative research researchers can explore subjects that are poorly studied with quantitative methods. These include opinions, individual's actions, and social science research.

A good qualitative study design starts with a goal or objective. This should be clearly defined or stated. The target population needs to be specified. A method for obtaining information from the study population must be carefully detailed to ensure there are no omissions of part of the target population. A proper collection method should be selected which will help obtain the desired information without overly limiting the collected data because many times, the information sought is not well compartmentalized or obtained. Finally, the design should ensure adequate methods for analyzing the data. An example may help better clarify some of the various aspects of qualitative research.

A researcher wants to decrease the number of teenagers who smoke in their community. The researcher could begin by asking current teen smokers why they started smoking through structured or unstructured interviews (qualitative research). The researcher can also get together a group of current teenage smokers and conduct a focus group to help brainstorm factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke (qualitative research).

In this example, the researcher has used qualitative research methods (interviews and focus groups) to generate a list of ideas of both why teens start to smoke as well as factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke. Next, the researcher compiles this data. The research found that, hypothetically, peer pressure, health issues, cost, being considered “cool,” and rebellious behavior all might increase or decrease the likelihood of teens starting to smoke.

The researcher creates a survey asking teen participants to rank how important each of the above factors is in either starting smoking (for current smokers) or not smoking (for current non-smokers). This survey provides specific numbers (ranked importance of each factor) and is thus a quantitative research tool.

The researcher can use the results of the survey to focus efforts on the one or two highest-ranked factors. Let us say the researcher found that health was the major factor that keeps teens from starting to smoke, and peer pressure was the major factor that contributed to teens to start smoking. The researcher can go back to qualitative research methods to dive deeper into each of these for more information. The researcher wants to focus on how to keep teens from starting to smoke, so they focus on the peer pressure aspect.

The researcher can conduct interviews and/or focus groups (qualitative research) about what types and forms of peer pressure are commonly encountered, where the peer pressure comes from, and where smoking first starts. The researcher hypothetically finds that peer pressure often occurs after school at the local teen hangouts, mostly the local park. The researcher also hypothetically finds that peer pressure comes from older, current smokers who provide the cigarettes.

The researcher could further explore this observation made at the local teen hangouts (qualitative research) and take notes regarding who is smoking, who is not, and what observable factors are at play for peer pressure of smoking. The researcher finds a local park where many local teenagers hang out and see that a shady, overgrown area of the park is where the smokers tend to hang out. The researcher notes the smoking teenagers buy their cigarettes from a local convenience store adjacent to the park where the clerk does not check identification before selling cigarettes. These observations fall under qualitative research.

If the researcher returns to the park and counts how many individuals smoke in each region of the park, this numerical data would be quantitative research. Based on the researcher's efforts thus far, they conclude that local teen smoking and teenagers who start to smoke may decrease if there are fewer overgrown areas of the park and the local convenience store does not sell cigarettes to underage individuals.

The researcher could try to have the parks department reassess the shady areas to make them less conducive to the smokers or identify how to limit the sales of cigarettes to underage individuals by the convenience store. The researcher would then cycle back to qualitative methods of asking at-risk population their perceptions of the changes, what factors are still at play, as well as quantitative research that includes teen smoking rates in the community, the incidence of new teen smokers, among others.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

- Introduction

- Issues of Concern

- Clinical Significance

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Publication types

- Study Guide

Qualitative Research Questions: Gain Powerful Insights + 25 Examples

We review the basics of qualitative research questions, including their key components, how to craft them effectively, & 25 example questions.

Einstein was many things—a physicist, a philosopher, and, undoubtedly, a mastermind. He also had an incredible way with words. His quote, "Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted," is particularly poignant when it comes to research.

Some inquiries call for a quantitative approach, for counting and measuring data in order to arrive at general conclusions. Other investigations, like qualitative research, rely on deep exploration and understanding of individual cases in order to develop a greater understanding of the whole. That’s what we’re going to focus on today.

Qualitative research questions focus on the "how" and "why" of things, rather than the "what". They ask about people's experiences and perceptions , and can be used to explore a wide range of topics.

The following article will discuss the basics of qualitative research questions, including their key components, and how to craft them effectively. You'll also find 25 examples of effective qualitative research questions you can use as inspiration for your own studies.

Let’s get started!

What are qualitative research questions, and when are they used?

When researchers set out to conduct a study on a certain topic, their research is chiefly directed by an overarching question . This question provides focus for the study and helps determine what kind of data will be collected.

By starting with a question, we gain parameters and objectives for our line of research. What are we studying? For what purpose? How will we know when we’ve achieved our goals?

Of course, some of these questions can be described as quantitative in nature. When a research question is quantitative, it usually seeks to measure or calculate something in a systematic way.

For example:

- How many people in our town use the library?

- What is the average income of families in our city?

- How much does the average person weigh?

Other research questions, however—and the ones we will be focusing on in this article—are qualitative in nature. Qualitative research questions are open-ended and seek to explore a given topic in-depth.

According to the Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry , “Qualitative research aims to address questions concerned with developing an understanding of the meaning and experience dimensions of humans’ lives and social worlds.”

This type of research can be used to gain a better understanding of people’s thoughts, feelings and experiences by “addressing questions beyond ‘what works’, towards ‘what works for whom when, how and why, and focusing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation,” states one paper in Neurological Research and Practice .

Qualitative questions often produce rich data that can help researchers develop hypotheses for further quantitative study.

- What are people’s thoughts on the new library?

- How does it feel to be a first-generation student at our school?

- How do people feel about the changes taking place in our town?

As stated by a paper in Human Reproduction , “...‘qualitative’ methods are used to answer questions about experience, meaning, and perspective, most often from the standpoint of the participant. These data are usually not amenable to counting or measuring.”

Both quantitative and qualitative questions have their uses; in fact, they often complement each other. A well-designed research study will include a mix of both types of questions in order to gain a fuller understanding of the topic at hand.

If you would like to recruit unlimited participants for qualitative research for free and only pay for the interview you conduct, try using Respondent today.

Crafting qualitative research questions for powerful insights

Now that we have a basic understanding of what qualitative research questions are and when they are used, let’s take a look at how you can begin crafting your own.

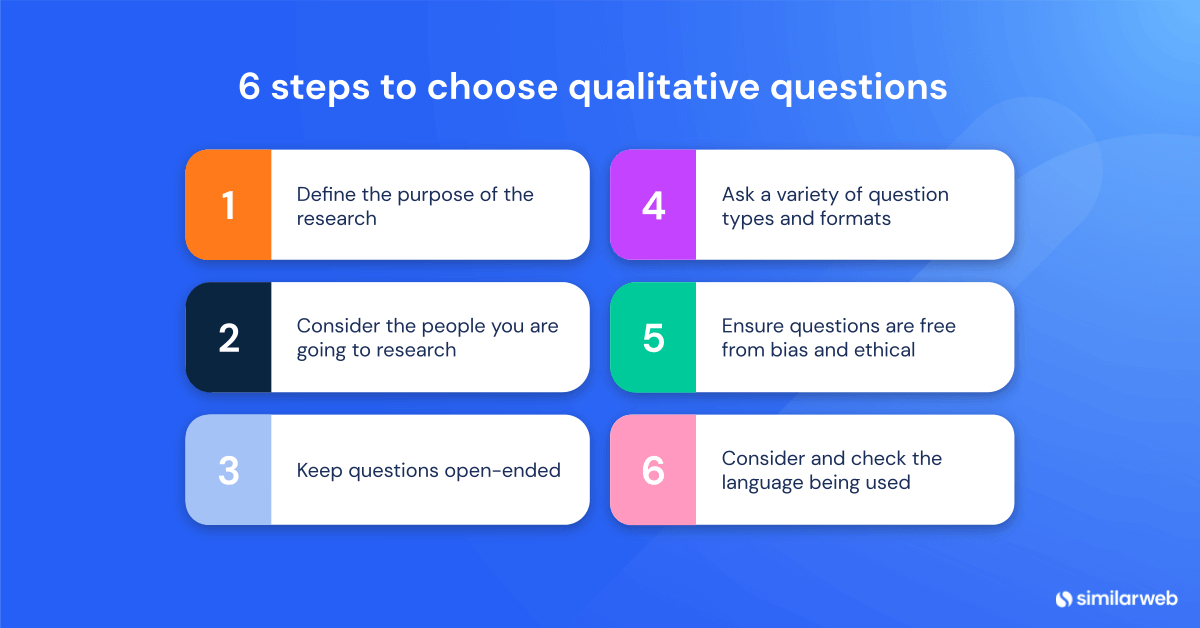

According to a study in the International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, there is a certain process researchers should follow when crafting their questions, which we’ll explore in more depth.

1. Beginning the process

Start with a point of interest or curiosity, and pose a draft question or ‘self-question’. What do you want to know about the topic at hand? What is your specific curiosity? You may find it helpful to begin by writing several questions.

For example, if you’re interested in understanding how your customer base feels about a recent change to your product, you might ask:

- What made you decide to try the new product?

- How do you feel about the change?

- What do you think of the new design/functionality?

- What benefits do you see in the change?

2. Create one overarching, guiding question

At this point, narrow down the draft questions into one specific question. “Sometimes, these broader research questions are not stated as questions, but rather as goals for the study.”

As an example of this, you might narrow down these three questions:

into the following question:

- What are our customers’ thoughts on the recent change to our product?

3. Theoretical framing

As you read the relevant literature and apply theory to your research, the question should be altered to achieve better outcomes. Experts agree that pursuing a qualitative line of inquiry should open up the possibility for questioning your original theories and altering the conceptual framework with which the research began.

If we continue with the current example, it’s possible you may uncover new data that informs your research and changes your question. For instance, you may discover that customers’ feelings about the change are not just a reaction to the change itself, but also to how it was implemented. In this case, your question would need to reflect this new information:

- How did customers react to the process of the change, as well as the change itself?

4. Ethical considerations

A study in the International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education stresses that ethics are “a central issue when a researcher proposes to study the lives of others, especially marginalized populations.” Consider how your question or inquiry will affect the people it relates to—their lives and their safety. Shape your question to avoid physical, emotional, or mental upset for the focus group.

In analyzing your question from this perspective, if you feel that it may cause harm, you should consider changing the question or ending your research project. Perhaps you’ve discovered that your question encourages harmful or invasive questioning, in which case you should reformulate it.

5. Writing the question

The actual process of writing the question comes only after considering the above points. The purpose of crafting your research questions is to delve into what your study is specifically about” Remember that qualitative research questions are not trying to find the cause of an effect, but rather to explore the effect itself.

Your questions should be clear, concise, and understandable to those outside of your field. In addition, they should generate rich data. The questions you choose will also depend on the type of research you are conducting:

- If you’re doing a phenomenological study, your questions might be open-ended, in order to allow participants to share their experiences in their own words.

- If you’re doing a grounded-theory study, your questions might be focused on generating a list of categories or themes.

- If you’re doing ethnography, your questions might be about understanding the culture you’re studying.

Whenyou have well-written questions, it is much easier to develop your research design and collect data that accurately reflects your inquiry.

In writing your questions, it may help you to refer to this simple flowchart process for constructing questions:

Download Free E-Book

25 examples of expertly crafted qualitative research questions

It's easy enough to cover the theory of writing a qualitative research question, but sometimes it's best if you can see the process in practice. In this section, we'll list 25 examples of B2B and B2C-related qualitative questions.

Let's begin with five questions. We'll show you the question, explain why it's considered qualitative, and then give you an example of how it can be used in research.

1. What is the customer's perception of our company's brand?

Qualitative research questions are often open-ended and invite respondents to share their thoughts and feelings on a subject. This question is qualitative because it seeks customer feedback on the company's brand.

This question can be used in research to understand how customers feel about the company's branding, what they like and don't like about it, and whether they would recommend it to others.

2. Why do customers buy our product?

This question is also qualitative because it seeks to understand the customer's motivations for purchasing a product. It can be used in research to identify the reasons customers buy a certain product, what needs or desires the product fulfills for them, and how they feel about the purchase after using the product.

3. How do our customers interact with our products?

Again, this question is qualitative because it seeks to understand customer behavior. In this case, it can be used in research to see how customers use the product, how they interact with it, and what emotions or thoughts the product evokes in them.

4. What are our customers' biggest frustrations with our products?

By seeking to understand customer frustrations, this question is qualitative and can provide valuable insights. It can be used in research to help identify areas in which the company needs to make improvements with its products.

5. How do our customers feel about our customer service?

Rather than asking why customers like or dislike something, this question asks how they feel. This qualitative question can provide insights into customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction with a company.

This type of question can be used in research to understand what customers think of the company's customer service and whether they feel it meets their needs.

20 more examples to refer to when writing your question

Now that you’re aware of what makes certain questions qualitative, let's move into 20 more examples of qualitative research questions:

- How do your customers react when updates are made to your app interface?

- How do customers feel when they complete their purchase through your ecommerce site?

- What are your customers' main frustrations with your service?

- How do people feel about the quality of your products compared to those of your competitors?

- What motivates customers to refer their friends and family members to your product or service?

- What are the main benefits your customers receive from using your product or service?

- How do people feel when they finish a purchase on your website?

- What are the main motivations behind customer loyalty to your brand?

- How does your app make people feel emotionally?

- For younger generations using your app, how does it make them feel about themselves?

- What reputation do people associate with your brand?

- How inclusive do people find your app?

- In what ways are your customers' experiences unique to them?

- What are the main areas of improvement your customers would like to see in your product or service?

- How do people feel about their interactions with your tech team?

- What are the top five reasons people use your online marketplace?

- How does using your app make people feel in terms of connectedness?

- What emotions do people experience when they're using your product or service?

- Aside from the features of your product, what else about it attracts customers?

- How does your company culture make people feel?