Problem solving

Worrying is a natural response to life's problems. But when it takes over and we can start to feel overwhelmed, it can really help to take a step back and break things down.

Learning new ways to work through your problems can make them feel more manageable, and improve your mental and physical wellbeing.

Video: Problem solving

The tips in this video can help you to find strategies and solutions for tackling the problems that can be solved, and learning how to manage and cope with those that cannot.

Steps and strategies to help you solve problems

1. focus on your values.

Feeling like you have lots of problems to solve in different areas of your life can make it difficult to know how and where to start.

A great way to focus is to write down a few areas of your life that are most important to you right now – for example, a relationship, finances or a long-term goal like studying or developing your career.

This can make it easier to prioritise which problems to tackle.

2. Tackle problems with possible solutions first

It's important to work out if your problem can be solved or is a "hypothetical worry" – things that are out of your control even though you might think about them often.

They might be based on something that happened in the past that cannot be changed or a worry about the future that starts with "what if…".

Ask yourself whether a problem can be dealt with by doing something practical. If the answer is no, it's a hypothetical worry.

Make a list of your problems, and work out which are solvable and which are hypothetical.

3. Set aside time to work through solvable problems

Set aside 5 or 10 minutes to think about possible solutions for one of your solvable problems.

Try to be as open-minded as you can, even if some ideas feel silly. Thinking broadly and creatively is often when the best solutions come to mind.

It may feel difficult at first but, over time, this approach can start to feel easier.

Once you have some ideas, think through or write down:

- the pros and cons of each solution

- whether it's likely to work

- if you have everything you need to try it

4. Make a plan

The next step is to choose a solution you want to try and make a plan for putting it into action. Try to be specific:

- What are you going to do?

- Do you need the support of anybody else?

- How much time do you need?

- When will you do it?

5. Try 'worry time'

Not all of our problems can be solved right away, but it can be difficult to switch off and stop ourselves from dwelling on them.

Using the "worry time" technique to stick to a short set time – say 10 to 15 minutes in the evening – for worrying can make this much easier to manage.

You can learn more about the worry time technique on tackling your worries .

6. Find time to relax

Worrying about our problems can make it harder to relax, but there are lots of things you can try to help you clear your mind and feel calmer.

The most important thing is to find what works for you. It might be getting active, spending time on an existing hobby or trying a new one, or techniques like mindfulness, meditation or our progressive muscle relaxation exercise.

Video: Progressive muscle relaxation

This video will guide you through an exercise to help you recognise when you're starting to get tense, and relax your body and mind.

7. Review and reflect

Once you start trying new approaches to solving and managing problems, consider setting aside time to review what went well with your solutions or anything else you noticed.

Make notes of the problems you face and any strategies you use to overcome them. This can come in handy later on and also be a good reminder of what works best for you.

Ticking off on a checklist any problems you manage to solve is a great way to recognise your achievements and boost your confidence.

8. Give journaling a go

Sometimes getting our thoughts out of our head – and down onto paper, our phones or anything else – is a great way to stop our worries and "what ifs" from spiralling out of control.

Expressing ourselves in this way can also make it easier to spot when our thoughts are unhelpful and we may benefit from a more balanced outlook. Give it a go to see if this works for you.

More self-help CBT techniques you can try

Bouncing back from life's challenges.

Taking steps to stay on top of your mental wellbeing and build resilience can really help you deal with problems when times are tougher. Learn more, and see tips and techniques you can use.

Tackling your worries

Facing your fears

Staying on top of things

Find more ideas to try in self-help CBT techniques

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Solving problems the cognitive-behavioral way, problem solving is another part of behavioral therapy..

Posted February 2, 2022 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

- What Is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?

- Find a therapist who practices CBT

- Problem-solving is one technique used on the behavioral side of cognitive-behavioral therapy.

- The problem-solving technique is an iterative, five-step process that requires one to identify the problem and test different solutions.

- The technique differs from ad-hoc problem-solving in its suspension of judgment and evaluation of each solution.

As I have mentioned in previous posts, cognitive behavioral therapy is more than challenging negative, automatic thoughts. There is a whole behavioral piece of this therapy that focuses on what people do and how to change their actions to support their mental health. In this post, I’ll talk about the problem-solving technique from cognitive behavioral therapy and what makes it unique.

The problem-solving technique

While there are many different variations of this technique, I am going to describe the version I typically use, and which includes the main components of the technique:

The first step is to clearly define the problem. Sometimes, this includes answering a series of questions to make sure the problem is described in detail. Sometimes, the client is able to define the problem pretty clearly on their own. Sometimes, a discussion is needed to clearly outline the problem.

The next step is generating solutions without judgment. The "without judgment" part is crucial: Often when people are solving problems on their own, they will reject each potential solution as soon as they or someone else suggests it. This can lead to feeling helpless and also discarding solutions that would work.

The third step is evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of each solution. This is the step where judgment comes back.

Fourth, the client picks the most feasible solution that is most likely to work and they try it out.

The fifth step is evaluating whether the chosen solution worked, and if not, going back to step two or three to find another option. For step five, enough time has to pass for the solution to have made a difference.

This process is iterative, meaning the client and therapist always go back to the beginning to make sure the problem is resolved and if not, identify what needs to change.

Advantages of the problem-solving technique

The problem-solving technique might differ from ad hoc problem-solving in several ways. The most obvious is the suspension of judgment when coming up with solutions. We sometimes need to withhold judgment and see the solution (or problem) from a different perspective. Deliberately deciding not to judge solutions until later can help trigger that mindset change.

Another difference is the explicit evaluation of whether the solution worked. When people usually try to solve problems, they don’t go back and check whether the solution worked. It’s only if something goes very wrong that they try again. The problem-solving technique specifically includes evaluating the solution.

Lastly, the problem-solving technique starts with a specific definition of the problem instead of just jumping to solutions. To figure out where you are going, you have to know where you are.

One benefit of the cognitive behavioral therapy approach is the behavioral side. The behavioral part of therapy is a wide umbrella that includes problem-solving techniques among other techniques. Accessing multiple techniques means one is more likely to address the client’s main concern.

Salene M. W. Jones, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist in Washington State.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Provide Psychosocial Skills Training and Cognitive Behavioral Interventions

What to Know

Psychosocial skills training and cognitive behavioral interventions teach specific skills to students to help them cope with challenging situations, set goals, understand their thoughts, and change behaviors using problem-solving strategies.

Psychosocial skills training asks students to explore whether their behaviors align with their personal values. Cognitive behavioral interventions teach students to identify their own unhelpful thoughts and replace them with thoughts that are more helpful. Students might practice helpful coping behaviors and find positive activities to try. Doing these things can improve their mood and other symptoms of mental distress.

Districts and schools can deliver interventions in one-on-one settings, small groups, and classrooms. Some interventions focus on concepts that are also taught in social skill and emotional development programs, like self-control and decision-making. A counselor or therapist can lead these programs.

What Can Schools Do?

Promote acceptance and commitment to change.

Schools can help promote acceptance and positive behavior change for students through psychosocial skills training and dialectical behavior therapy. Psychosocial skills training asks students to explore whether their behaviors align with their personal values. Students who see that their behavior does not match their values can decide to make behavior changes. These trainings also help students accept what they cannot change and focus on what they can change. Dialectical behavior therapy teaches mindfulness, acceptance, and commitment skills.

Approaches using acceptance and commitment to change are associated with increases in students’ coping skills and decreases in depression and physical symptoms of depression.

Provide Cognitive Behavioral Interventions

Cognitive behavioral interventions for schools often include multiple sessions. They can be used for one student or a small group. Sessions often follow a standardized manual of activities to help students examine their own thoughts and behaviors. The interventions can include asking students to share what they learn about their thoughts and behaviors with their parents and other people. In some interventions, session leaders focus on a specific topic. Other interventions target mental health symptoms, like depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress.

Cognitive behavioral interventions can improve students’ mental health in many ways, including decreasing anxiety, depression, and symptoms related to post-traumatic stress.

- LARS & LISA

- Tools for Getting Along Curriculum—Behavior Management Resource Guide

- Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS )

- Bounce Back

- Brief Intervention for School Clinicians

- Skills for Academic and Social Success

- Building Confidence

Engage Students in Coping Skills Training Groups

Coping skills training groups use principles of cognitive behavioral intervention to teach students skills to help them handle specific problems. Students can also use these skills to help them cope when their lives are changing. Similar to social, emotional, and behavioral learning programs, coping skills training often focuses on building resilience, or being able to “bounce back” when bad things happen. Students can practice skills outside of the small group, like they would with social skills and emotional development lessons.

Coping skills training groups can increase coping skills for students and decrease anxiety and depression.

- Journey of Hope

- High School Transition Program

Focus on Equity

Students who have been exposed to trauma may receive trauma-focused or trauma-informed interventions in school. Cognitive behavioral interventions that are trauma-informed meet the unique needs of students exposed to traumatic experiences. These interventions teach problem-solving and relaxation techniques and help reduce trauma-related symptoms, including behavioral challenges. Trauma-informed interventions can also improve students’ coping strategies.

Implementation Tips

Cognitive behavioral interventions and psychosocial skills training help with many kinds of student needs. They can be used at multiple grade levels. Leaders can:

- Work with school mental health staff to find ways for students to practice their new behaviors and coping skills.

- Use the Multitiered Systems of Support (MTSS) framework to ensure that students are appropriately matched with classroom, small-group, or individual interventions that meet their needs.

Want to Learn More?

For more details on MTSS and providing psychosocial skills training and cognitive behavioral interventions, see Promoting Mental Health and Well-Being in Schools: An Action Guide for School Administrators [PDF - 3 MB]

- Increase Students’ Mental Health Literacy

- Promote Mindfulness

- Promote Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Learning

- Enhance Connectedness Among Students, Staff, and Families

- Support Staff Well-Being

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

22 Best Counseling Interventions & Strategies for Therapists

Counseling is highly beneficial, with “far-reaching effects in life functioning” (Cochran & Cochran, 2015, p. 7).

While therapeutic relationships are vital to a positive outcome, so too are the selection and use of psychological interventions targeting the clients’ capability, opportunity, motivation, and behavior (Michie et al., 2014).

This article introduces some of the best interventions while identifying the situations where they are likely to create value for the client, helping their journey toward meaningful, value-driven goals.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains:

What is a counseling intervention, list of popular therapeutic interventions, how to craft a treatment plan 101, 13 helpful therapy strategies, interventions & strategies for career counseling, 2 best interventions for group counselors, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

“Changing ingrained behavior patterns can be challenging” and must avoid or at least reduce the risk of reverting (Michie et al., 2014, p. 11).

The American Psychological Association (n.d., para. 1) describes an intervention as “any action intended to interfere with and stop or modify a process, as in treatment undertaken to halt, manage, or alter the course of the pathological process of a disease or disorder.”

Interventions are intentional behaviors or “change strategies” introduced by the counselor to help clients implement problem management and move toward goals (Nelson-Jones, 2014):

- Counselor-centered interventions are where the counselor does something to or for the client, such as providing advice.

- Client-centered interventions empower the client, helping them develop their capacity to intervene in their own problems (for example, monitoring and replacing unhelpful thinking).

Creating or choosing the most appropriate intervention requires a thorough assessment of the client’s behavioral targets, what is needed, and how best to achieve them (Michie et al., 2014).

The selection of the intervention is guided by the:

- Nature of the problem

- Therapeutic orientation of the counselor

- Willingness and ability of the client to proceed

During counseling, various interventions are likely to be needed at different times. For that reason, counselors will require a broad range of techniques that fit the client’s needs, values, and culture (Corey, 2013).

In recent years, an increased focus has been on the use of evidence-based practice, where the choice and use of interventions is based on the best available research to make a difference in the lives of clients (Corey, 2013).

“Clients are hypothesis makers and testers” who have the reflective capacity to think about how they think (Nelson-Jones, 2014, p. 261).

Helping clients attend to their thoughts and learn how to instruct themselves more effectively can help them break repetitive patterns of insufficiently strong mind skills while positively influencing their feelings.

The following list includes some of the most popular interventions used in a variety of therapeutic settings (modified from Magyar-Moe et al., 2015; Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2015; Cochran & Cochran, 2015; Corey, 2013):

Detecting and disputing demanding rules

Rigid, demanding thinking is identified by ‘musts,’ ‘oughts,’ and ‘shoulds’ and is usually unhelpful to the client.

For example:

I must do well in this test, or I am useless. People must treat me in the way I want; otherwise, they are awful.

Clients can be helped to dispute such thinking using “reason, logic, and facts to support, negate or amend their rules” (Nelson-Jones, 2014, p. 265).

Such interventions include:

- Functional disputing Pointing out to clients that their thinking may stand in the way of achieving their goals

- Empirical disputing Encouraging clients to evaluate the facts behind their thoughts

- Logical disputing Highlighting the illogical jumps in their thinking from preferences to demands

- Philosophical disputing Exploring clients’ meaning and satisfaction outside of life issues

Identifying automatic perceptions

Our perceptions greatly influence how we think. Clients can benefit from recognizing they have choices in how they perceive things and avoiding jumping to conclusions.

- Creating self-talk Self-talk can be helpful for most clients and can target anger management, stress handling, and improving confidence. For example:

This is not the end of the world. I’ve done this before; I can do it well again.

- Creating visual perceptions Building on the client’s existing visual images can be helpful in understanding and working through problematic situations (and their solutions).

One simple exercise to help clients see the strong relationship between visualizing and feeling involves asking clients to think of someone they love. Almost always, they form a mental image along with a host of feelings.

Visual relaxation is a powerful self-helping skill involving clients taking time out of their busy life to find calm through vividly picturing a real or imagined relaxing scene.

Creating better expectations

Clients’ explanatory styles (such as expecting to fail) can create self-fulfilling prophecies. Interventions can help by:

- Assessing the likelihood of risks or rewards

- Increasing confidence in the potential for success

- Identifying coping skills and support factors

- Time projection Imagery can help by enabling the client to step into a possible future where they manage and overcome difficult times or worrying situations.

For example, the client can imagine rolling forward to a time when they are successful in a new role at work or a developing relationship.

Creating realistic goals

Goals can motivate clients to improve performance and transition from where they are now to where they would like to be. However, it is essential to make sure they are realistic, or they risk causing undue pressure and compromising wellbeing.

The following interventions can help (Nelson-Jones, 2014):

- Stating clear goals The following questions are helpful when clients are setting goals :

Does the goal reflect your values? Is the goal realistic and achievable? Is the goal specific? Is the goal measurable? Does the goal have a timeframe?

Helping clients to experience feelings

Counseling can influence clients’ emotions and their physical reactions to emotions by helping them (Nelson-Jones, 2014):

- Experience feelings

- Express feelings

- Manage feelings

- Empty chair dialogue This practical intervention involves the client engaging in an imaginary conversation with another person; it helps “clients experience feelings both of unresolved anger and also of weakness and victimization” (Nelson-Jones, 2014, p. 347).

The client may be asked to shift to the empty chair and play the other person’s part to explore conflict, interactions, and emotions more fully (Corey, 2013).

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

“Counselors and counseling trainees make choices both concerning specific interventions and about interventions used in combination” (Nelson-Jones, 2014, p. 223).

Through early and continued engagement with the client throughout the counseling approach , the counselor and client set specific, measurable, and achievable goals and create a treatment plan with a defined intervention strategy (Dobson, 2010).

The treatment plan becomes a map, combining interventions to reach client goals and overcome problems – to get from where they are now to where they want to be. However, no plan should be too fixed or risk preventing the client’s progress in their ‘wished-for’ direction. Rather, it must be open for regular revisit and modification (Nelson-Jones, 2014).

Counseling and therapeutic treatment plans vary according to the approaches used and the client’s specific needs but should be strength-based and collaborative. Most treatment plans typically consider the following points (modified from GoodTherapy, 2019):

- History and assessment – E.g., psychosocial history, symptom onset, past and present diagnoses, and treatment history

- Present concerns – The current concerns and issues that led the client to counseling

- Counseling contract – A summary of goals and desired changes, responsibility, and the counseling approach adopted

- Summary of strengths – It can be helpful to summarize the client’s strengths, empowering them for goal achievement.

- Goals – Measurable treatment goals are vital to the treatment plan.

- Objectives – Goals are broken down into smaller, achievable outcomes that support achievement during counseling.

- Interventions – Interventions should be planned early to support objectives and overall goals.

- Tracking progress and outcomes – Regular treatment plan review should include updating progress toward goals.

While a vital aspect of the counseling process is to ensure that treatment takes an appropriate direction for the client, it is also valuable and helpful for clients and insurance companies to understand likely timescales.

“Depression is one of the most common mental health disorders with a high burden of disease and the leading cause of years of life lost due to disability” (Hu et al., 2020, p. 1).

- Exercise interventions Research has shown that even low-to-moderate levels of exercise can help manage and treat depression (Hu et al., 2020).

- Gratitude Practicing gratitude can profoundly affect how we see our lives and those around us. Completing gratitude journals and reviewing three positive things that have happened at the end of the day have been shown to decrease depression and promote wellbeing (Shapiro, 2020).

- Behavioral activation Scheduling activities that result in positive emotions can help manage and overcome depression (Behavioral Activation for Depression, n.d.).

Anxiety can stop clients from living their lives fully and experiencing positive emotions. Many interventions can help, including:

- Understanding your anxiety triggers Interoceptive exposure techniques focus on reproducing sensations associated with anxiety and other difficult emotions. Clients benefit from learning to identify anxiety triggers, behavioral changes, and associated bodily sensations (Boettcher et al., 2016).

- Using a building image Clients are asked to form a mental image of themselves as a building. Their description of its state of repair and quality of foundation provides helpful insight into the client’s wellbeing and degree of anxiety (Thomas, 2016).

Grief therapy

Grief therapy helps clients accept reality, process the pain, and adjust to a new world following the loss of a loved one. Several techniques can help, including (modified from (Worden, 2018):

- Creating memory books Compiling a memory book containing photographs, memorabilia, stories, and poems can help families come together, share their grief, and reminisce.

- Directed imagery Like the ‘empty chair’ technique, through imagining the missing loved one in front of them, the grieving person is given the opportunity to talk to them.

Substance abuse

“There has been significant progress and expansion in the development of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for substance abuse and dependence” (Jhanjee, 2014, p. 1). Psychological interventions play a growing role in disorder treatment programs; they include:

- Brief optimistic interventions Brief advice is delivered following screening and assessment to at-risk individuals to reduce drinking and other harmful activities.

- Motivational interviewing This technique involves using targeted questioning while expressing empathy through reflective listening to resolve client ambivalence about their substance abuse.

Marriage therapy

Interventions are a vital aspect of marriage therapy , often targeting communication skills, problem-solving, and taking responsibility (Williams, 2012).

They can include the following interventions:

- Taking responsibility It is vital that clients take responsibility for their actions within a relationship. The counselor will work with the couple, asking the following questions, as required (modified from Williams, 2012):

How have you contributed to the relationship’s problems? What changes are needed to improve the relationship? Are you willing to make the changes needed?

- Create an action plan Once the couple agrees, the changes will be combined into a plan, with specific actions to help them achieve their goal.

Helping cancer patients

“There is no evidence to suggest that having counseling will help treat or cure your cancer”; however, it may help with coping, relationship issues, and dealing with practical problems (Cancer Research UK, 2019, para. 16).

Several counseling interventions that have proven helpful with the psychological burden include (Guo et al., 2013):

- Psychoeducation Sharing the importance of mental wellbeing and coping with the client and involving them in their cancer treatment can reduce anxiety and improve confidence.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Replacing incorrect or unhelpful beliefs can help the client achieve a more positive outlook regarding the treatment.

Career counselors help individuals or groups cope more effectively with career concerns, including (Niles & Harris-Bowlsbey, 2017):

- Career choice

- Managing career changes and transitions

- Job-related stress

- Looking for a job

While there are many interventions and strategies, the following are insightful and effective:

- Creating narratives Working with clients to build personal career narratives can help them see their movement through life with more meaning and coherence and better understand their decisions. Such an intervention can be valuable in looking forward and choosing the next steps.

- Group counseling Multiple group sessions can be arranged to cover different aspects of career-related issues and related emotional issues. They may include role-play or open discussion around specific topics.

The ultimate goals are usually to “help group members respond to each other with a combination of therapeutic attending, and sharing their own reactions and related experiences” (Cochran & Cochran, 2015, p. 329).

Examples of group interventions include:

- Circle of friends This group intervention involves gathering a child’s peers into a circle of friendly support to encourage and help them with problem-solving. The intervention has led to increased social acceptance of children with special needs (Magyar-Moe et al., 2015).

- Group mindfulness Mindfulness in group settings has been shown to be physically and mentally beneficial (Shapiro, 2020). New members may start by performing a body-scan meditation where they bring awareness to each part of their body before turning their attention to their breathing.

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

We have many free interventions, using various approaches and mediums, that support the counseling process and client goal achievement.

- Nudge Interventions in Groups The group provides a valuable setting for exploring the potential of ‘nudges’ to alter behavior in a predictable way.

- Developing Interoceptive Exposure Therapy Interventions This worksheet explores the sensations behind panic attacks and phobias.

- Therapist Interoceptive Exposure Record Use this helpful log to track interoceptive exposure interventions.

- Motivational Interviewing This template uses the five stages of change to consider the client’s readiness for change and the appropriate interventions to use.

- Breaking Out of the Comfort Zone Making changes typically requires clients to step out of their comfort zone. This worksheet identifies opportunities to embrace new challenges.

More extensive versions of the following tools are available with a subscription to the Positive Psychology Toolkit© , but they are described briefly below:

- Benefit finding

Psychological research has identified long-term benefits to using benefit finding, with individuals reporting new appreciation for their strengths and building resilience (e.g., Affleck & Tennen, 1996; Davis et al., 1998; McMillen et al., 1997).

- Begin by talking about a traumatic event.

- Focus on the positive aspects of the experience.

- Consider what the experience has taught you.

- Identify how the experience has helped you grow

- Self-compassion box

Self-compassion is a crucial aspect of our psychological wellbeing, made up of showing ourselves kindness, accepting imperfection, and paying attention to personal suffering with clarity and objectivity.

- Step one – Begin by recognizing the uncompassionate self.

- Step two – Select self-compassion reminders.

- Step three – Redirect attention to self-compassion.

- Step four – Reflect on creating more self-compassion in life.

Over time, the client should see the gaps closing between where they are now and where they want to be.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others reach their goals, check out this collection of 17 validated motivation & goal achievement tools for practitioners. Use them to help others turn their dreams into reality by applying the latest science-based behavioral change techniques.

Counseling uses interventions to create positive change in clients’ lives. They can be performed individually but typically form part of a treatment or intervention plan developed with the client.

Each intervention helps the client work toward their goals, strengthen their capabilities, identify opportunities, increase motivation, and modify behavior.

They aim to create sufficient momentum to support change and avoid the risk of the client reverting, transitioning the client (often one small step at a time) from where they are now to where they want to be.

While some interventions have value in multiple settings – individual, group, career, couples, family – others are specific and purposeful. Many interventions target unhelpful, repetitive thinking patterns and aim to replace harmful thoughts, unrealistic expectations, or biased thinking. Others create a possible future where the client can engage with what might be or could happen , coming to terms with change or their own negative emotions.

Use this article to explore the range of interventions available to counselors in sessions or as homework. Try them out in different settings, working with the client to identify their value or potential for modification.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

- Affleck, G., & Tennen, H. (1996). Construing benefits from adversity: Adaptational significance and dispositional underpinnings. Journal of Personality , 64 , 899–922.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Intervention. In APA dictionary of psychology . Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://dictionary.apa.org/intervention

- Behavioral Activation for Depression. (n.d.). Retrieved February 16, 2022, from https://medicine.umich.edu/sites/default/files/content/downloads/Behavioral-Activation-for-Depression.pdf

- Boettcher, H., Brake, C. A., & Barlow, D. H. (2016). Origins and outlook of interoceptive exposure. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry , 53 , 41–51.

- Cancer Research UK. (2019). How counselling can help . Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/coping/emotionally/talking-about-cancer/counselling/how-counselling-can-help

- Cochran, J. L., & Cochran, N. H. (2015). The heart of counseling: Counseling skills through therapeutic relationships . Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Corey, G. (2013). Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy . Cengage.

- Davis, C. G., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Larson, J. (1998). Making sense of loss and benefiting from the experience: Two construals of meaning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 75 , 561–574.

- Dobson, K. S. (Ed.) (2010). Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Guo, Z., Tang, H. Y., Li, H., Tan, S. K., Feng, K. H., Huang, Y. C., Bu, Q., & Jiang, W. (2013). The benefits of psychosocial interventions for cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes , 11 (1), 1–12.

- GoodTherapy. (2019, September 25). Treatment plan . Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/psychpedia/treatment-plan

- Hu, M. X., Turner, D., Generaal, E., Bos, D., Ikram, M. K., Ikram, M. A., Cuijpers, P., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2020). Exercise interventions for the prevention of depression: a systematic review of meta-analyses. BMC Public Health , 20 (1), 1255.

- Jhanjee, S. (2014). Evidence-based psychosocial interventions in substance use. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine , 36 (2), 112–118.

- Magyar-Moe, J. L., Owens, R. L., & Conoley, C. W. (2015). Positive psychological interventions in counseling. The Counseling Psychologist , 43 (4), 508–557.

- McMillen, J. C., Smith, E. M., & Fisher, R. H. (1997). Perceived benefit and mental health after three types of disaster. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 65 , 733–739.

- Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions . Silverback.

- Nelson-Jones, R. (2014). Practical counselling and helping skills . Sage.

- Niles, S. G., & Harris-Bowlsbey, J. (2017). Career development interventions . Pearson.

- Shapiro, S. L. (2020). Rewire your mind: Discover the science + practice of mindfulness . Aster.

- Sommers-Flanagan, J., & Sommers-Flanagan, R. (2015). Study guide for counseling and psychotherapy theories in context and practice: Skills, strategies, and techniques (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Thomas, V. (2016). Using mental imagery in counselling and psychotherapy: A guide to more inclusive theory and practice . Routledge.

- Williams, M. (2012). Couples counseling: A step by step guide for therapists . Viale.

- Worden, J. W. (2018). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner . Springer.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Hello wonderful staff members, I do hope you are well. I wanted to convey my sincerest gratitude for your free informative resource of brilliant information. I am an adult online psychology first year student as well as a sex therapy student, apart from my brilliant instructors with my sex therapy professors . I am on my own to teach myself with my psychology your resource have been my salvation as an independent psychology learning student. Your articles are all life enhancing written with comprehension and depth while not fraught with verbosity and complex language. I want you to know that your company’s generosity in making these articles free are the missing link in all students who would like to advance their academic careers. With profound appreciation Michelle

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Youth Counseling: 17 Courses & Activities for Helping Teens

From a maturing body and brain to developing life skills and values, the teen years can be challenging, and mental health concerns may arise. Teens [...]

How To Plan Your Counseling Session: 6 Examples

Planning is crucial in a counseling session to ensure that time inside–and outside–therapy sessions is well spent, with the client achieving a successful outcome within [...]

Applied Positive Psychology in Therapy: Your Ultimate Guide

Without a doubt, this is an exciting time for positive psychology in therapy. Many academics and therapists now recognize the value of this fascinating, evolving [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (3)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 07 October 2021

Young people’s mental health is finally getting the attention it needs

You have full access to this article via your institution.

A kite-flying festival in a refugee camp near Syria’s border with Turkey. The event was organized in July 2020 to support the health and well-being of children fleeing violence in Syria. Credit: Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency/Getty

Worldwide, at least 13% of people between the ages of 10 and 19 live with a diagnosed mental-health disorder, according to the latest State of the World’s Children report , published this week by the United Nations children’s charity UNICEF. It’s the first time in the organization’s history that this flagship report has tackled the challenges in and opportunities for preventing and treating mental-health problems among young people. It reveals that adolescent mental health is highly complex, understudied — and underfunded. These findings are echoed in a parallel collection of review articles published this week in a number of Springer Nature journals.

Anxiety and depression constitute more than 40% of mental-health disorders among young people (those aged 10–19). UNICEF also reports that, worldwide, suicide is the fourth most-common cause of death (after road injuries, tuberculosis and interpersonal violence) among adolescents (aged 15–19). In eastern Europe and central Asia, suicide is the leading cause of death for young people in that age group — and it’s the second-highest cause in western Europe and North America.

Collection: Promoting youth mental health

Sadly, psychological distress among young people seems to be rising. One study found that rates of depression among a nationally representative sample of US adolescents (aged 12 to 17) increased from 8.5% of young adults to 13.2% between 2005 and 2017 1 . There’s also initial evidence that the coronavirus pandemic is exacerbating this trend in some countries. For example, in a nationwide study 2 from Iceland, adolescents (aged 13–18) reported significantly more symptoms of mental ill health during the pandemic than did their peers before it. And girls were more likely to experience these symptoms than were boys.

Although most mental-health disorders arise during adolescence, UNICEF says that only one-third of investment in mental-health research is targeted towards young people. Moreover, the research itself suffers from fragmentation — scientists involved tend to work inside some key disciplines, such as psychiatry, paediatrics, psychology and epidemiology, and the links between research and health-care services are often poor. This means that effective forms of prevention and treatment are limited, and lack a solid understanding of what works, in which context and why.

This week’s collection of review articles dives deep into the state of knowledge of interventions — those that work and those that don’t — for preventing and treating anxiety and depression in young people aged 14–24. In some of the projects, young people with lived experience of anxiety and depression were co-investigators, involved in both the design and implementation of the reviews, as well as in interpretation of the findings.

Quest for new therapies

Worldwide, the most common treatment for anxiety and depression is a class of drug called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which increase serotonin levels in the brain and are intended to enhance emotion and mood. But their modest efficacy and substantial side effects 3 have spurred the study of alternative physiological mechanisms that could be involved in youth depression and anxiety, so that new therapeutics can be developed.

Mental health: build predictive models to steer policy

For example, researchers have been investigating potential links between depression and inflammatory disorders — such as asthma, cardiovascular disease and inflammatory bowel disease. This is because, in many cases, adults with depression also experience such disorders. Moreover, there’s evidence that, in mice, changes to the gut microbiota during development reduce behaviours similar to those linked to anxiety and depression in people 4 . That suggests that targeting the gut microbiome during adolescence could be a promising avenue for reducing anxiety in young people. Kathrin Cohen Kadosh at the University of Surrey in Guildford, UK, and colleagues reviewed existing reports of interventions in which diets were changed to target the gut microbiome. These were found to have had minimal effect on youth anxiety 5 . However, the authors urge caution before such a conclusion can be confirmed, citing methodological limitations (including small sample sizes) among the studies they reviewed. They say the next crop of studies will need to involve larger-scale clinical trials.

By contrast, researchers have found that improving young people’s cognitive and interpersonal skills can be more effective in preventing and treating anxiety and depression under certain circumstances — although the reason for this is not known. For instance, a concept known as ‘decentring’ or ‘psychological distancing’ (that is, encouraging a person to adopt an objective perspective on negative thoughts and feelings) can help both to prevent and to alleviate depression and anxiety, report Marc Bennett at the University of Cambridge, UK, and colleagues 6 , although the underlying neurobiological mechanisms are unclear.

In addition, Alexander Daros at the Campbell Family Mental Health Institute in Toronto, Canada, and colleagues report a meta-analysis of 90 randomized controlled trials. They found that helping young people to improve their emotion-regulation skills, which are needed to control emotional responses to difficult situations, enables them to cope better with anxiety and depression 7 . However, it is still unclear whether better regulation of emotions is the cause or the effect of these improvements.

Co-production is essential

It’s uncommon — but increasingly seen as essential — that researchers working on treatments and interventions are directly involving young people who’ve experienced mental ill health. These young people need to be involved in all aspects of the research process, from conceptualizing to and designing a study, to conducting it and interpreting the results. Such an approach will lead to more-useful science, and will lessen the risk of developing irrelevant or inappropriate interventions.

Science careers and mental health

Two such young people are co-authors in a review from Karolin Krause at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Canada, and colleagues. The review explored whether training in problem solving helps to alleviate depressive symptoms 8 . The two youth partners, in turn, convened a panel of 12 other youth advisers, and together they provided input on shaping how the review of the evidence was carried out and on interpreting and contextualizing the findings. The study concluded that, although problem-solving training could help with personal challenges when combined with other treatments, it doesn’t on its own measurably reduce depressive symptoms.

The overarching message that emerges from these reviews is that there is no ‘silver bullet’ for preventing and treating anxiety and depression in young people — rather, prevention and treatment will need to rely on a combination of interventions that take into account individual needs and circumstances. Higher-quality evidence is also needed, such as large-scale trials using established protocols.

Along with the UNICEF report, the studies underscore the transformational part that funders must urgently play, and why researchers, clinicians and communities must work together on more studies that genuinely involve young people as co-investigators. Together, we can all do better to create a brighter, healthier future for a generation of young people facing more challenges than ever before.

Nature 598 , 235-236 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02690-5

Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E. & Binau, S. G. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 128 , 185–199 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Thorisdottir, I. E. et al. Lancet Psychiatr. 8 , 663–672 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Murphy, S. E. et al. Lancet Psychiatr. 8 , 824–835 (2021).

Murray, E. et al. Brain Behav. Immun. 81 , 198–212 (2019).

Cohen Kadosh, K. et al. Transl. Psychiatr. 11 , 352 (2021).

Bennett, M. P. et al. Transl Psychiatr. 11 , 288 (2021).

Daros, A. R. et al. Nature Hum. Behav . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01191-9 (2021).

Krause, K. R. et al. BMC Psychiatr. 21 , 397 (2021).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Psychiatric disorders

- Public health

The rise of eco-anxiety: scientists wake up to the mental-health toll of climate change

News Feature 10 APR 24

Use fines from EU social-media act to fund research on adolescent mental health

Correspondence 09 APR 24

‘Without these tools, I’d be lost’: how generative AI aids in accessibility

Technology Feature 08 APR 24

Lethal dust storms blanket Asia every spring — now AI could help predict them

News 15 APR 24

Bird flu outbreak in US cows: why scientists are concerned

News Explainer 08 APR 24

Adopt universal standards for study adaptation to boost health, education and social-science research

Correspondence 02 APR 24

India is booming — but there are worries ahead for basic science

News 10 APR 24

How to break big tech’s stranglehold on AI in academia

Brazil’s postgraduate funding model is about rectifying past inequalities

Junior Group Leader Position at IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

The Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) is one of Europe’s leading institutes for basic research in the life sciences. IMBA is located on t...

Austria (AT)

IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

Research Group Head, BeiGene Institute

A cross-disciplinary research organization where cutting-edge science and technology drive the discovery of impactful Insights

Pudong New Area, Shanghai

BeiGene Institute

Open Rank Faculty, Center for Public Health Genomics

Center for Public Health Genomics & UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center seek 2 tenure-track faculty members in Cancer Precision Medicine/Precision Health.

Charlottesville, Virginia

Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia

Husbandry Technician I

Memphis, Tennessee

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude)

Lead Researcher – Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 26 October 2011

Problem-solving therapy for depression and common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: piloting a task-shifting primary mental health care intervention in a population with a high prevalence of people living with HIV

- Dixon Chibanda 1 ,

- Petra Mesu 2 ,

- Lazarus Kajawu 1 , 2 ,

- Frances Cowan 3 , 4 ,

- Ricardo Araya 5 &

- Melanie A Abas 6

BMC Public Health volume 11 , Article number: 828 ( 2011 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

204 Citations

172 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is limited evidence that interventions for depression and other common mental disorders (CMD) can be integrated sustainably into primary health care in Africa. We aimed to pilot a low-cost multi-component 'Friendship Bench Intervention' for CMD, locally adapted from problem-solving therapy and delivered by trained and supervised female lay workers to learn if was feasible and possibly effective as well as how best to implement it on a larger scale.

We trained lay workers for 8 days in screening and monitoring CMD and in delivering the intervention. Ten lay workers screened consecutive adult attenders who either were referred or self-referred to the Friendship Bench between July and December 2007. Those scoring above the validated cut-point of the Shona Symptom Questionnaire (SSQ) for CMD were potentially eligible. Exclusions were suicide risk or very severe depression. All others were offered 6 sessions of problem-solving therapy (PST) enhanced with a component of activity scheduling. Weekly nurse-led group supervision and monthly supervision from a mental health specialist were provided. Data on SSQ scores at 6 weeks after entering the study were collected by an independent research nurse. Lay workers completed a brief evaluation on their experiences of delivering the intervention.

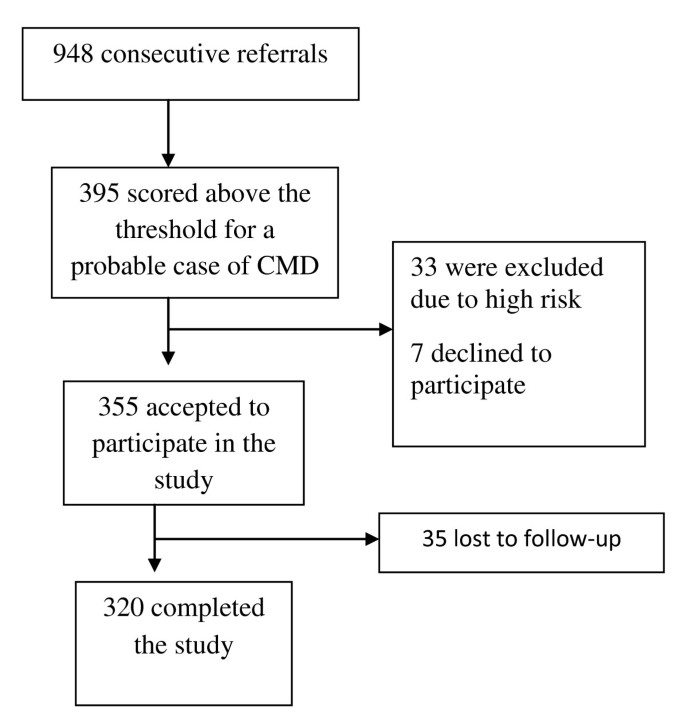

Of 395 potentially eligible, 33 (8%) were excluded due to high risk. Of the 362 left, 2% (7) declined and 10% (35) were lost to follow-up leaving an 88% response rate (n = 320). Over half (n = 166, 52%) had presented with an HIV-related problem. Mean SSQ score fell from 11.3 (sd 1.4) before treatment to 6.5 (sd 2.4) after 3-6 sessions. The drop in SSQ scores was proportional to the number of sessions attended. Nine of the ten lay workers rated themselves as very able to deliver the PST intervention.

We have found preliminary evidence of a clinically meaningful improvement in CMD associated with locally adapted problem-solving therapy delivered by lay health workers through routine primary health care in an African setting. There is a need to test the effectiveness of this task-shifting mental health intervention in an appropriately powered randomised controlled trial.

Trial registration

ISRCTN: ISRCTN25476759

Peer Review reports

Mental disorders cause considerable suffering, disability and social exclusion in Africa, and are poorly recognised and undertreated [ 1 , 2 ]. In Zimbabwe, common mental disorders, such as depression mixed with anxiety, are found in over 25% of those attending primary health care services or maternal services, and in up to 30% of females in the community [ 3 – 5 ]. In the Zimbabwean Shona language, thinking too much ( kufungisisa ), along with deep sadness ( kusuwisisa ), and painful heart (moyo unorwadza) are terms in common use for emotional distress being close to European and American categories of common forms of depression and anxiety [ 3 , 6 ]

There is increasing evidence, mainly from other world regions but also rapidly growing evidence from within low income countries, that improving mental health is a low cost approach to improve quality of life and reduce disability [ 7 , 8 ]. Very little of this evidence, however, is from Africa. In Chile, low intensity low-cost treatments for depression have been integrated into primary health care [ 9 ]. These include, for example, psycho education, problem-solving therapy and self-help approaches [ 10 , 11 ]. Problem-solving therapy has been shown to be effective for depression and common mental health problems [ 12 , 13 ]. Previous attempts to deliver care for common mental disorders through primary care clinics in Zimbabwe although promising in the short-term had shown little long-term success due to reliance on overstretched nursing staff and lack of supervision [ 14 ]. In 2005, a government operation in Mbare , a township in Harare, resulted in many people becoming homeless or losing their livelihoods [ 15 ] and was perceived by the Mbare community to lead to high rate of emotional distress. Local stakeholders identified the need for a community mental health intervention. This had to be at no extra cost to the primary health care clinic, to utilise space outside the overcrowded clinic rooms, and to use methods already tested locally. A pilot intervention based on a problem-solving approach was identified [ 16 ]. It was suggested this be delivered by lay health workers via a 'Friendship Bench' ( Chigaro Chekupanamazano ) placed in the clinic grounds, and that a system of supervision and stepped care be part of the package. A team comprising psychologists, a primary care nurse and a psychiatrist adapted existing training materials on problem solving therapy [ 16 , 17 ] in the light of experience working with lay workers and general nurses in primary care. Adaptations included at least one home visit by the lay workers early in the therapy given it is normal practice for lay workers to visit clients in their homes, and encouraging clients to schedule some positive activities that really mattered to them to make life more rewarding. The training and the intervention were pre-tested in 5 lay workers and 143 primary care clients and found to be acceptable to them and to the lay workers. The aim of this pilot was to gather preliminary data on the effectiveness of this intervention and to see if the intervention would be feasible, and if so to gather ideas about how best to implement it on a larger scale.

Mbare is a high density suburb or township in the south of Harare. It is characterized by ethnic diversity and high unemployment with most residents relying on informal trading. The literacy rate is estimated to be over 90%. There are three government run Primary Health Care (PHC) clinics, staffed almost exclusively by general nurses, for a population of approximately 200 000. The study took place in all three clinics.

Twenty lay workers, locally termed health promoters, support the nurses at these three clinics. The lay workers are a respected group of primary health care providers, commonly referred to as ambuya utano (grandmother health provider) (Figure 1 ). In Mbare , all lay workers are female, literate, have at least primary school education, and have lived locally for at least 15 years. Their mean age is 58 years. Their main role is in community health outreach, which includes supporting people living with HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis by providing individual and family support (practical, psychological and spiritual) and encouraging medication adherence. They also deliver community health education and promotion e.g. through encouraging immunisation and methods to control disease outbreaks. Lay workers report weekly to the environmental health officer and a nurse-manager. The lay workers cover geographical patches, which are sections of the community demarcated by the City of Harare according to street grids. Each geographical patch has approximately 3000 inhabitants. Ten lay workers were selected at random for this pilot: three from two of the clinics and four from the largest clinic.

Some of the lay health workers involved in the Friendship Bench project, sitting in front of one of the Benches .

Participants

Inclusion criteria: aged 18 and over; residents of geographical patches in Mbare , Harare, covered by the ten selected lay workers; score > 7 on Shona Symptom Questionnaire screen for common mental disorders. Exclusion criteria: requiring acute medical attention such that they cannot participate; severe psychiatric symptoms and/or risk to self or others requiring specialist referral as assessed by primary care research nurse

Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe and written informed consent was sought from all participants. The study was registered as a non-controlled trial http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN25476759

Recruitment

We aimed to recruit from the clinic staff, from the community, and from the lay workers themselves. The psychiatrist (DC) and psychologists (PM, KJ) presented to the clinic nursing staff and to all 20 lay workers the rationale for the project and referral methods to the friendship Bench. Notices written in the local vernacular language explaining the location and uses of the benches were placed at six different points within the entrance hall and waiting area of each clinic.

The lay workers introduced and publicised the Friendship Bench to the community through community stakeholders' meetings and during visits to people's homes, churches, schools and police stations. They introduced it as an adjunct to their normal daily community health outreach activity. They described the Friendship Bench approach as aimed at addressing common mental health issues such as kufungisisa (thinking too much) as a result of, among other things, HIV infection, AIDS, domestic violence, family sickness and poverty.

Clients were either referred or could self refer to the Friendship Bench, which was available Mon-Friday 9.00 am to 12.00 pm at each clinic. Those referred or who self-referred were directed by nursing or reception staff to sit on the Friendship Bench which in each clinic was a large wooden bench located under a tree within sight of the lay workers' office. One duty lay worker was responsible for the Bench each day on rotation and would approach the Bench after a potential client sat on it. The duty lay worker was responsible for collecting data on inclusion criteria including residential and basic demographic information and on psychological symptoms using the Shona Symptom Questionnaire (SSQ) [ 4 ]. She also gathered information on recent stressors using a brief life events screen based on one used previously in Harare [ 18 ]. Everyone was offered some education, advice and often sign-posted to support services. Those meeting inclusion criteria were referred to a research nurse for assessment of risk to self or to others (e.g. suicidal ideation, history of deliberate self harm, very severe symptoms). She referred those excluded on these grounds to the visiting psychiatrist (DC). She invited those meeting eligibility criteria to participate in the pilot and took written informed consent. She then referred them back to the lay worker who made arrangements for their first Friendship Bench session within 2-5 days with a lay worker that covered their geographical patch.

Outcome measure

The main outcome measure was the Shona Symptom Questionnaire (SSQ). The SSQ is a 14-item screening tool for common mental disorders, integrating local idioms and internationally recognised items for emotional distress. It was developed and validated in Zimbabwe using exemplary cross-cultural methods [ 4 ]. It is self-administered and has a reliable internal consistency (r = 0.85) and satisfactory sensitivity and specificity, with a score of > = 8 being the cut-point. It is based on a yes/no response and asks about symptoms such as thinking too much, failing to concentrate, work lagging behind, insomnia, suicidal ideation, unhappiness and so on, over a 1 week period. All participants were approached six to eight weeks after their first treatment session to complete a self-administered SSQ which was collected by the research nurse in the absence of the attending lay worker.

The Intervention

The intervention consisted of brief individual talking therapy based on problem-solving therapy delivered by a lay worker. Most sessions took place sitting on a bench termed "The Friendship Bench" ( Chigaro Chekupanamazano ). The Friendship Benches were made for the project by local craftsmen (see Figure 1 ). They are located within the grounds of each of the three participating clinics in a discrete area under the trees in the clinic gardens.

Table 1 shows the activities involved in the delivery of the Friendship Bench. The lay worker would initially explain to all participants how to self-administer the screening tool, the Shona Symptom Questionnaire. Problem-solving therapy (PST) included identification and exploration of problems, and identification and implementation of solutions, based on prior principles [ 19 ]. Our PST was a locally developed seven-step plan previously used in partnership with government, lay and traditional care providers [ 16 ]. Up to a maximum of 6 sessions on the Bench were offered with the second session taking place at the client's home and sometimes also one of the later sessions. Those most in financial need were referred to two local income-generating projects (peanut butter making; recycling). The problem solving therapy was enhanced with a component of activity scheduling in that clients were also encouraged to carry out activities that really mattered to them to make life more rewarding. Home visits included prayer. Prayer was already a well recognised part of the support provided by LW in their community health outreach role in Mbare , which has a 98% Christian population with more than 70 Christian faith groups. On average each prayer lasts 15-30 minutes and is delivered by one lay worker together with the family. The aim of the prayer is to comfort the sick and the family. The use of prayer in formal gatherings related to health is a common practice in Zimbabwe. The existing prayer format used prior to the introduction of the Friendship Bench was incorporated in the six sessions without any alterations.

Training, selection and supervision of facilitators

All 20 lay workers were trained.

We provided an 8-day training run by two clinical psychologists (PM and LK), a general nurse trained in systemic counselling (ST) and a psychiatrist (DC). This covered didactic lectures on common mental disorders (CMD), including kufungisisa (thinking too much) but particularly focussed on skills to identify CMD using the Shona Symptoms Questionnaire [ 4 ], and to manage CMD using simple psycho-education and problem-solving therapy [ 16 – 19 ]. Lay workers then took part in two days of pre-testing including screening, identification, and referral processes within the clinic, and referral of 'red flags' (critical case-situations such as suicidal risk). We made use of practise with clients on the Friendship Bench and in clients' homes'. We developed a client referral manual, which included a list of NGO's, private and public institutions, and church organizations to be used by lay workers or patients.

Ten lay workers were selected at random for the pilot: three from two of the clinics and four from the largest clinic.

A daily peer-support group for lay workers was introduced. The peer group meetings were facilitated by one of the lay workers who would then present during weekly group supervision where all lay workers participated. A clinic staff nurse trained in counseling provided weekly group supervision at the largest clinic. The clinical psychologist and the psychiatrist provided further supervision every fortnightly and monthly, respectively.

We developed a brief 6-item questionnaire with a 4-point Likert scale for the lay workers to evaluate the PST intervention. For instance, we asked them to rate the ease with which they had learned the problem-solving therapy approach, the ease with which they delivered the intervention and the proportion of clients who appeared to benefit from the PST approach. We asked the lay workers to complete this once 6 weeks after the study has begun. We also carried out one focus group with 6 of the 10 workers and asked them to describe their experiences of delivering the intervention. Their responses were recorded in writing and analysed for content and themes by two of the authors.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations and proportions) were estimated for those who participated, who declines, who were lost to follow, and who were excluded due to psychiatric risk. We used t-tests and regression models to test changes in SSQ scores before and after completion of the treatment, adjusting for SSQ scores at baseline. Data were entered and analysed using EpiInfo 2002 and STATA 10.0 (Release 10, College Station, TX: Stata Corporation. 2003) after range checks and double entry of all questionnaires.

Recruitment and attrition at follow-up

Between July and November 2007, 948 persons visited the Bench. Of these 948 persons who visited the Bench, 395 (42%) scored above the cut-point of the Shona Symptom Questionnaire (SSQ). Among these, 33 (8%) with a mean SSQ score of 11.8 (sd 1.2) were excluded from the pilot study due to being severely depressed and/or suicidal and were referred to the psychologist or psychiatrist (see Figure 2 ). Of the 362 invited to take part, 2% (7) declined and 10% (35) were lost to follow-up leaving an 88% response rate (320 participants). Of the 395, 188 (48%) presented with an HIV-related problem of whom 166 (88%) participated.

Flow diagram of recruitment into the study .

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the 395 who scored above the cut-point of the SSQ, according to whether or not they entered the study. Participants were more likely to be female. More of those who participated were female and married (70% female, 57% married) compared to those who declined (42% female, 43% married) or who were those lost to follow-up (40% female, 41% married). Those with less than eight years of education were more likely to be lost to follow-up than to participate. The primary reasons presented for visiting the Bench among those who participated were HIV-related, somatic complaints and domestic violence.

Most of those who participated were referred to the Friendship Bench by clinic staff (35%) and lay workers (24%). Other common forms of referral were: friend/relative (13%), self-referral (12%) or police (9%).

Psychological symptoms scores before and after the six-week intervention period

All participants completed a minimum of 3 sessions over a six week period with 20%, 30%, 21% and 30% completing 3, 4, 5 or 6 sessions respectively.

The mean SSQ score for the 320 cases was 11.3 (sd 1.4) before treatment. After receiving between 3 to 6 sessions the mean score dropped by 4.8 points to 6.5 (sd 2.4) [t = 13.6 (p = 0.0087)]. For those completing 3 or more sessions, 66% recovered to below case level on the SSQ at 6-8 weeks

Table 3 shows the drop in SSQ scores according to the number of sessions attended, adjusting for baseline SSQ score. The more sessions attended the larger the drop in SSQ scores with a drop of more than 3 points observed among those who attended all six sessions.

Lay workers evaluation

Nine of the ten lay workers rated themselves as very able to deliver the PST intervention. All of them rated at least half of their clients as benefiting from PST with 7/10 rating 'more than half' of their clients benefiting from the intervention. Themes emerging from the focus group suggested that the lay workers viewed effective ingredients of the Friendship Bench to include:

Their position of trust in the community-clients viewed them as wise and confidential. The clients viewed them as 'persons who would not gossip' which was 'reassuring in a small community'

Being able to visit clients in their homes which they felt instilled hope

Minimising stigma associated with having a mental health problem. The lay workers heard from their clients that as they were already connected with public health work (rather than psychiatry) and carried out home visits routinely as part of their work on public health promotion and that it was not stigmatising for clients with kufungisisa (thinking too much) to be visited.

The structured 'talk therapy' helped them to monitor the progress and challenges that clients were facing.

Breaking down the problems into specific and manageable steps

Giving feedback to clients.

In the focus group, the lay workers reported several case histories of their clients. These included the following:

A female client who had been to the bench with a score of 12/14 on the SSQ at baseline and subsequently received 2 home visits described the lay health workers as 'bringing peace' in her home, and 'less agitation' from her partner. Her score dropped to 7/14 after six sessions.

ii) A female client with an SSQ of 11/14 dropped to 6/14 after five sessions which included a home visit after she presented with being unable to come to terms with her HIV status.

iii) A female senior member of the local protestant church described the home visits as 'hope for those of us who are unable to open up in a church congregation about our HIV status'. Her score went down to 5/14 from 10/14 after 6 sessions.

This is the first example of lay health workers in Africa delivering a low intensity mental health intervention, using locally adapted tools, for common mental disorders in primary care. We have shown that it is feasible for lay workers to deliver this intervention for depression and common mental disorders, and that recruitment to the intervention from primary care, community agencies and self-referral was also feasible (Figure 2 ). The treatment appeared acceptable to the community and the lay workers were able to integrate the intervention into their routine work. Preliminary findings also show that the intervention is efficacious in reducing psychological morbidity, with a drop in score of nearly 5 points on the 14-item psychological outcome scale after 3-6 sessions, and efficacy proportional to the number of sessions attended. Over half of those who participated had presented with a problem related to HIV.

Chance does not seem a likely explanation for our finding as the significance value for the drop in score after 3-6 sessions was at p < 0.01 level. Bias may explain some of the results in that women and married participants were more likely to participate than to decline or to be lost to follow-up and those with lower education were more likely to be lost to follow-up than to participate. However, overall, the response rate of 88% was extremely high so it appears unlikely that bias is playing a major role in explaining the results. Measurement error is also unlikely to explain the findings. The Shona Symptom Questionnaire was developed using optimal cross-cultural methods and has been validated against an international diagnostic interview with most of those scoring at or above the recommended cut-off having mixed depression and anxiety or pure depression using ICD criteria [ 4 ].

We do not have a comparison group from the same study who did not receive the intervention. However, a prospective study in primary care in Harare showed that a mean drop in score of 4.7 (sd 6.3) on the SSQ was associated with recovery from 'case' to 'non-case' and with significantly less disability [ 20 ] (see Table 3 of the Patel paper). These authors further report that those who experienced a drop in score of 4 or more points on the SSQ were more likely to self-report an improvement in health than those who remained at case-level on the SSQ. Our crude mean drop in score of 4.8 points thus appears to represent a meaningful drop in score indicating efficacy of the Friendship Bench intervention. Furthermore, our finding that drop in score was significantly correlated with the number of sessions attended, even after adjusting for baseline SSQ score, adds weight to our assertion that the intervention appears to be efficacious. In our pilot, 34% remained cases at 6-8 weeks follow-up after the intervention, whereas in the Patel et al study [ 20 ], where there was no specific intervention, 48% of primary health care attenders remained cases.

The quantitative findings are supported by the lay workers evaluation. All of them rated at least half of their clients as benefiting from problem-solving therapy with 7/10 rating 'more than half' of their clients benefiting from the intervention. Themes that emerged from qualitative work support the argument that implementing this intervention through an existing public health intervention and by mature women with a position of trust in the community, helps explain its apparent efficacy. The lay workers-or 'grandmother health providers' are viewed as wise, confidential, authoritative and not prone to gossip. As the lay workers were already respected for their public health work, participants said they did not find it not stigmatising to be visited.

The intervention is theoretically closely linked to problem-solving therapy, which has been shown to be effective for depression and common mental health problems [ 12 , 13 ], together with an activity scheduling component [ 21 ]. It incorporates local adaptations that are integral to the routine work of the therapists who are culturally sanctioned lay health workers, known and respected as 'grandmother health providers'. For instance, the inclusion of Christian prayer for 15 minutes during 1 or 2 of the 6 sessions was part of the existing practice of the lay workers and it would have been inappropriate to remove that normal practice. While there is no evidence from randomised controlled trials that prayer is an effective treatment for depression in Christians, there is some suggestion from non-randomised studies with small samples that religious activities may benefit depression [ 22 ].