Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Banned by the law, practiced by the society: The study of factors associated with dowry payments among adolescent girls in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, India

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Validation

Affiliation Department of Mathematical Demography & Statistics, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Roles Writing – original draft

Affiliation Department of Population Policies and Programmes, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Affiliation Department of Public Health and Mortality Studies, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation

* E-mail: [email protected]

Roles Formal analysis

Roles Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

- Shobhit Srivastava,

- Shekhar Chauhan,

- Ratna Patel,

- Strong P. Marbaniang,

- Pradeep Kumar,

- Ronak Paul,

- Preeti Dhillon

- Published: October 15, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Despite the prohibition by the law in 1961, dowry is widely prevalent in India. Dowry stems from the early concept of ’Stridhana,’ in which gifts were given to the bride by her family to secure some personal wealth for her when she married. However, with the transition of time, the practice of dowry is becoming more common, and the demand for a higher dowry becomes a burden to the bride’s family. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the factors associated with the practice of dowry in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

We utilized information from 5206 married adolescent girls from the Understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults (UDAYA) project survey conducted in two Indian states, namely, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Dowry was the outcome variable of this study. Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to explore the factors associated with dowry payment during the marriage.

The study reveals that dowry is still prevalent in the state of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Also, the proportion of dowry varies by adolescent’s age at marriage, spousal education, and household socioeconomic status. The likelihood of paid dowry was 48 percent significantly less likely (OR: 0.52; CI: 0.44–0.61) among adolescents who knew their husbands before marriage compared to those who do not know their husbands before marriage. Adolescents with age at marriage more than equal to legal age had higher odds to pay dowry (OR: 1.60; CI: 1.14–2.14) than their counterparts. Adolescents with mother’s who had ten and above years of education, the likelihood of dowry was 33 percent less likely (OR: 0.67; CI: 0.45–0.98) than their counterparts. Adolescents belonging to the richest households (OR: 1.48; CI: 1.13–1.93) were more likely to make dowry payments than adolescents belonging to poor households.

Limitation of the dowry prohibition act is one of the causes of continued practices of dowry, but major causes are deeply rooted in the social and cultural customs, which cannot be changed only using laws. Our study suggests that only the socio-economic development of women will not protect her from the dowry system, however higher dowry payment is more likely among women from better socio-economic class.

Citation: Srivastava S, Chauhan S, Patel R, Marbaniang SP, Kumar P, Paul R, et al. (2021) Banned by the law, practiced by the society: The study of factors associated with dowry payments among adolescent girls in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, India. PLoS ONE 16(10): e0258656. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656

Editor: Nishith Prakash, University of Connecticut, UNITED STATES

Received: February 17, 2021; Accepted: October 3, 2021; Published: October 15, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Srivastava et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data can be found from the following link: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/RRXQNT .

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The preponderance of dowry and bride-price practices is culturally driven and existed as a way of marriage requirements [ 1 ]. In various traditional societies, the transfer of money or goods accompanies the initiation of marriage. When made to groom families from the bride families, such transfers are widely classified as dowry [ 2 ]. Historically, dowry served the fundamental purpose of inheritance for women as men were thought to inherit the family property in the Indian context [ 3 ]. Moreover, dowry has been seen as a way to compensate the groom’s family for the economic support they would provide to the new member of the family, i.e., the bride, as women tend to have a small role in the market economy and are dependent on their husbands [ 4 ]. The above interpretation holds true in the Indian scenario as historically; dowry has been practiced in upper-caste families where women’s economic opportunities are limited. In the lower caste; where women are seen as economic contributors, the bride-price’s custom was more common [ 5 ]. However, dowry dynamics have been changing in recent times, and people from the upper and lower caste are practicing dowry. Furthermore, recent studies noted that the dowry system is prevalent across many cultures and is no longer is treated as a contribution towards a suitable beginning of the practical life of newly married couples [ 6 ].

In India, dowry has been prevalent for ages. The custom of dowry in India is a deeply rooted cultural phenomenon [ 7 ]. The concept of Sanskritization was proposed by eminent sociologist Srinivas in 1952, and many communities that never took dowry before started practicing dowry probably due to the phenomenon of Sanskritization [ 8 ]. A study has noticed that dowry is being practiced in about 93 percent of Indian marriage and is almost universal [ 9 ]. Not only this, but studies have also noted that dowry payments have increased manifolds in India [ 10 , 11 ]. A clear explanation for rising dowry payments is the marriage squeeze [ 12 ]. However, in her study, Anderson refuted the claims of any association between marriage squeeze and dowry payments [ 11 ]. Marriage squeeze depicts tightness of marriage market. Chiplunkar and Weaver (2019) carefully documented the transition of dowry payments in India using the 1999 wave of the ARIS-REDS data and test which theories about dowry inflation are consistent with the data and which are not [ 13 ]. Chiplunkar and Weaver (2019) show that the theory of sanskritization cannot explain dowry inflation. Similarly, they also find that the REDS data offers limited support to the marriage squeeze hypothesis. Few researchers postulated the theory of ’sex ratios and dowry’ whereby changes in sex ratios due to population growth could alter dowry payments [ 8 , 14 , 15 ]. The spousal age gap difference remains a concern as male marry at older ages than women, so when population grows, as was the case in India in the 1950s and 1960s, there will be a surplus of women at marriageable ages relative to men at marriageable ages. In the resulting "marriage squeeze", competition over relatively scarce grooms may cause an increase in dowry [ 2 , 16 ]. Contrary to these predictions, Chiplunkar and Weaver do not find that sex ratio in the marriage market is related to increases in the prevalence or size of dowry [ 13 ]. Instead, the "squeeze" appears to be relieved by changes in the age of marriage, with a smaller average age difference between brides and grooms [ 11 ]. Zhang & Chan (1999) utilizing 1989 Taiwan Women and Family Survey data of 25–60 years old women stated that dowry improves the bride’s welfare in her family [ 17 ]. They further stated that dowry represents bequest by altruistic parents for a daughter which not only increases the wealth of new conjugal household but also enhances the bargaining power of the bride [ 17 ].

Researchers unanimously agreed that the issue of dowry could be associated with gender inequality and female deprivation [ 7 , 18 ]. Alfano (2017) argued that the presence of son preference resulting from deeply rooted attitudes that boys are more valuable than girls is mostly attributed to the dowry payments [ 19 ]. Alfano (2017) further stated that the economic intuition that sons are cheaper to raise than daughters stem from the dowry [ 19 ]. He opined that dowries increase the economic returns to sons and decrease the return to daughters [ 19 ]. Kumar (2020) is of the opinion that dowry prevails because of disempowerment of women, male dominance, and financial dependence on men [ 20 ]. He further stated that inability to give dowry causes victimization of brides; whereas, the glorification of dowry generates son preference leading to female feticide, sex-ratio imbalances, and gender inequality [ 20 ]. Prevailing son preference in Indian societies leads to female feticide so as to avoid the burden of dowry [ 21 – 23 ]. Bhalotra et al., (2020) found a positive relationship between gold prices and the value of dowry payments [ 21 ]. They stated that payment in gold is essential in Indian marriages and further validated that gold prices marked the financial burden of dowry [ 21 ]. Further, Bhalotra et al. (2020) evidently provided evidence that gold prices impact dowry value and, that parents react to unexpected increases in gold prices by committing girl abortion or neglecting girls in the first month of life, when neglect more easily translates into death [ 21 ].

Parents desire their daughters to marry educated men with urban jobs, because such men have higher and more certain incomes, which are not subject to climatic cycles and which are paid monthly, and because the wives of such men will be freed from the drudgery of rural work and will usually live apart from their parents-in-law. In a sellers’ market, created by relative scarcity, there was no alternative but to offer a dowry with one’s daughter [ 24 ]. A different notion was put forward by Bloch & Rao (2002), where they stated that husbands are more likely to beat their wives when the wife’s family is rich because there are more resources to extract and the returns are greater [ 25 ]. A husband’s greater satisfaction with the marriage, indicated by higher numbers of male children, reduces the probability of violence against women [ 25 ]. Thus, it is likely that aspects of violent behavior are strongly linked to economic incentives [ 25 ]. Previous research has documented numerous factors associated with the dowry, such as socio-economic factors of the families [ 26 ], failure of the government in curbing the practice of dowry [ 27 ], first-born gender in the family [ 28 ]. A study showed that increasing the returns to women’s human capital could lead to the disappearance of marriage payments altogether [ 29 ]. Edlund (2006) hypothezing that rise in dowry payments in India has been associated with the disadvantaged position of women in the marriage market, has shown that in a much-used data set on dowry inflation, net dowries did not increase in the period after 1950 [ 30 ]. Moreover, the stagnation of net dowries after 1950 undermine claims that marriage market conditions for brides have worsened [ 30 ]. Answering the query of whether dowry is bequest or price, Arunachalam & Logam (2016) found that more than a quarter of marriages use dowry as bequests [ 31 ]. Arunachalam & Logam (2016) further noticed limited evidence on marriage squeeze as a factor for dowry [ 31 ].

It was around sixty years back when India enacted the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, to prohibit the giving or taking of the dowry. However, the act has been unsuccessful in curbing down the dowry’s menace and failed in its basic fundamental of eliminating the demand for dowry [ 7 ]. The dowry is so profoundly entrenched that a way out seems a bit tedious task; even well-educated families begin saving wealth for their daughter after she is born in anticipation of the futuristic dowry payments [ 6 ]. Traditional marriage institutions affect the household’s financial decisions and influence saving behaviour [ 28 ]. Despite acknowledging the problem of dowry widely, there is a paucity of empirical studies that systematically analyze the correlates of dowry among adolescent girls in recent times [ 13 ]. Given the growing concerns about the dowry’s socioeconomic consequences, it is imperative to explore the correlates of dowry in India. Therefore, we have tried to examine the factors associated with dowry in India. This study captures data from adolescents aged 15–19 years of age. While examining the correlates of dowry among adolescent girls, this study contributes to the existing literature examining factors associated with dowry.

This study’s data came from Understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults (UDAYA) project survey conducted in two Indian states Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, in 2016 by the Population Council under the guidance of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The survey collected detailed information on family, media, community environment, assets acquired in adolescence, and quality of transitions to young adulthood indicators. A total of 150 primary sampling units (PSUs)—villages in rural areas and census wards in urban areas have been selected in the state in order to conduct interviews in the required number of households. The 150 PSUs were further divided equally into rural and urban areas, that is, 75 for rural respondents and 75 for urban respondents. Within each sampling domain, survey adopted a multi-stage systematic sampling design. The 2011 census list of villages and wards (each consisting of several census enumeration blocks [CEBs] of 100–200 households) served as the sampling frame for the selection of villages and wards in rural and urban areas, respectively. This list was stratified using four variables, namely, region, village/ward size, proportion of the population belonging to scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, and female literacy. The UDAYA provide the estimates for states as a whole as well as urban and rural areas of the states. The required sample for each sub-group of adolescents was determined at 920 younger boys, 2,350 older boys, 630 younger girls, 3,750 older girls, and 2,700 married girls in the state. The sample size for Uttar Pradesh and Bihar was 10,350 and 10,350 adolescents aged 10–19 years, respectively. The sample size for this study was 5,206 adolescent girls who were married at the time of the survey [ 32 , 33 ]. In the present study the unmarried boys and girls were dropped and only married adolescent girls were included in the sample. Fig 1 represents the sample selection procedure for the present study.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.g001

Outcome variables

Dowry was the outcome variable of this study, which was binary. The question was framed as: "whether dowry paid at the time of marriage or later"? the response was coded as 0 means "no" and 1 means "yes." The variable measures the response of dowry if demanded during marriage or after marriage.

Explanatory variables

- Interaction with husband before marriage was named as "Husband known before marriage" and was recoded as not known and known.

- Age at marriage was recoded as less than legal age (<18 years) and more than equals to legal age (≥18 years). The sample in 18 and above age category would be small as the dataset contained married adolescent’s girl aged 15–19 years.

- Spousal age gap was recoded wife older/almost the same age (wife older or one year younger than husband) and husband older (husband two or more years older than wife).

- Spousal education recoded both not educated, only husband educated, only wife educated, and both educated.

- Working status of the respondent was recoded as no and yes.

- Whether vocation training was received or not by the respondent

- Mother’s education of the respondent was recoded as no education, 1–7, 8–9, and 10 and above years of education.

- Land ownership among in-laws was coded as no and yes. The measurements about the land owned was not available in the data set.

- Caste was recoded as Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (SC/ST) and non-SC/ST. The Scheduled Caste include a group of population which is socially segregated and financially/economically by their low status as per Hindu caste hierarchy. The Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) are among the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups in India [ 34 ].

- Religion was recoded as Hindu and non-Hindu.

- Wealth index was recoded as poorest, poorer, middle, richer, and richest. The survey measured household economic status, using a wealth index composed of household asset data on ownership of selected durable goods, including means of transportation, as well as data on access to a number of amenities. The wealth index was constructed by allocating the following scores to a household’s reported assets or amenities. Principal component analysis technique was used for creating the wealth index variable. The scores were divided into five quintiles using xtile command in Stata 14.

- Residence was available in data as urban and rural.

- Data were available for two states, i.e., Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, as the survey was conducted in these two states only.

Statistical analysis

Univariate, bivariate, and multivariate logistic regression analysis [ 35 ] were performed to find the factors associated with dowry payment during marriage.

Where π is the expected proportional response for the logistic model; β 0 ,….., β M are the regression coefficient indicating the relative effect of a particular explanatory variable on the outcome. These coefficients change as per the context in the analysis in the study. Svyset command using Stata 14 was used to control for complex survey design. Additionally, individual weights were used to present the representative results. Further it was evident from the robustness check that logit model had a better fit. S4 and S5 Tables provide the summary statistics and correlation matrix along with plot of logistic predicted probabilities vs linear model ( S1 Fig ) and Plot of logistic predicted probabilities vs linear probability model (LPM) ( S2 Fig ).

Next, we check the stability of the regression coefficients and their sensitivity to selection bias using standard methods [ 36 , 37 ]. We obtain bias-adjusted coefficients and calculate the absolute deviation from the non-bias-adjusted regression estimates to understand the extent of bias. Further, we calculate Oster’s δ, whose value higher than one would indicate that the regression coefficients are insensitive to omitted variable bias and variable selection bias [ 37 ]. All estimates were obtained with the assumption that the bias-adjusted model would explain 1.3 times variation in dowry payment status compared to the non-bias-adjusted model. The statistical analyses for coefficient stability check were performed using the psacalc command by estimating linear probability models in STATA [ 38 ].

The socio-demographic profile of the study population (married adolescents aged 15–19 years) is presented in Table 1 . About 65 percent of adolescent girls did not know their husbands before marriage. Most husbands were older than their wives (91%) in the study population, and 64 percent of spouses (both) were educated. Only 11.7 percent of adolescent girls were working, and about 16 percent of adolescent girls received vocational training. Around 42 percent of girls’ in-laws had land ownership. Nearly 30 percent of adolescents belonged to the SC/ST group, and most adolescents were Hindu (82.5%) and lived in rural areas (86%).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.t001

Table 2 depicts the distribution of adolescents who paid dowry by background characteristics. Overall, around 86 percent of adolescent girls reported that dowry was paid for their marriage. Bivariate results revealed that paid dowry was significantly higher among those who did not know their husbands before marriage (87.2%) than their counterparts (82.9%). It was more prevalent among those whose age at marriage was more than the legal age (89.1%). Similarly, dowry was more prevalent among married adolescent women whose husbands were older and higher if both husband and wife were educated. Interestingly, paid dowry was significantly higher among those who were not working (86%) and received vocational training (91%). Moreover, paid dowry was lower among the non-Hindu community (84.5%). Interestingly, the dowry was more prevalent in the richest households (88.7%). The rural-urban differential was observed for paid dowry. For instance, rural adolescents (86.8%) reported higher paid dowry than urban (78.7%) counterparts. S2 Table provides estimates for Uttar Pradesh and Bihar separately.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.t002

Estimates from logistic regression analysis for adolescents who paid dowry by important predictors were presented in Table 3 . The likelihood of paid dowry was 48 percent significantly less likely (OR: 0.52; CI: 0.44–0.61) among adolescents who knew their husbands before marriage compared to those who do not know their husbands before marriage. Moreover, if adolescent girls who got marry after legal age (OR: 1.60; CI: 1.14–2.14) were 60 per cent more likely to pay dowry than their counterparts. The likelihood of paid dowry was 25 percent more likely among adolescents whose husband was older (OR: 1.25; CI: 1.03–1.67) than their counterparts. The odds of paid dowry were 39 percent, 47 percent, and 89 percent significantly more likely if only husband (OR: 1.39; CI: 1.05–1.83), only wife (OR: 1.47; CI: 1.11–1.96), and both were educated (OR: 1.89; CI: 1.48–2.4) respectively, than when both were not educated. Interestingly, if an adolescent’s mother was having ten and above years of education, the likelihood of dowry was 33 percent less likely (OR: 0.67; CI: 0.45–0.98) than their counterparts. Wealth quintile has a positive relationship with adolescents who paid dowry for marriage. For instance, the odds of paid dowry were 33 percent, 39 percent, and 48 percent more likely among adolescents whose family gave dowry to marry them in middle (OR: 1.33; CI: 1.03–1.73), richer (OR: 1.39; CI: 1.06–1.83), and richest (OR: 1.48; CI: 1.07–2.05) families respectively compared to poorest counterparts. Moreover, the likelihood of paid dowry was 54 percent more likely in rural areas (OR: 1.54; CI: 1.28–1.86) than urban areas. Importantly, Bihar has higher odds for paid dowry (OR: 1.42; CI: 1.19–1.70) compared to Uttar Pradesh. Additionally, the estimates were provided for urban and rural place of residence as many covariates may vary by place of residence ( S1 Table ). Moreover, stepwise regression analysis was used to check for sensitivity bias ( S3 Table ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.t003

Table 4 gives the results of the coefficient stability check of the explanatory variables of dowry payment among female adolescents. From the bias-adjusted estimates (see column 8), we observed that the multivariable association between husband familiar before marriage, age at marriage, spousal education, wealth index, residence and state with dowry payment is statistically significant (at 5% level) and lies in the same direction as the uncontrolled estimates. Moreover, from the difference shown in column 10, we can say that the bias-adjusted and non-bias-adjusted regression coefficients are similar. However, Oster’s delta revealed that the statistically significant multivariable association of age at marriage and state with dowry payment suffers from omitted-variable and selection bias.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.t004

The practice of dowry is widely prevalent in India [ 9 ], despite the prohibition by the law in 1961. Dowry stems from the early concept of ’Stridhana,’ in which gifts were given to the bride by her family to secure some personal wealth for her when she married [ 39 ]. However, with the transition of time, dowry has become a common practice, and the demand for a higher dowry becomes a burden to the bride’s family. Srinivasan (2005) describes that modern dowry comprises demands that include gold, cash, and consumer goods that far exceed what families can afford, exploiting its obligatory symbolic nature and the fact that they are gifts of love woman from her natal family [ 40 ]. This study aimed to determine the factors associated with the practice of dowry among adolescent girls. The study reveals that the practice of dowry is still prevalent and is influenced by many factors such as spousal age gap, spousal education, and household socioeconomic status.

Our study report that a girl knowing her husband before marriage is less likely to pay dowry than those not known about the husband. This may be because the information about knowing each other is much better in a love match [ 41 ], and the practice of dowry is almost non-existent in the case of love marriage [ 40 , 42 ]. Other studies mentioned that in an arranged marriage where information about each other is limited, the groom’s quality is inferred through his education, associated with the dowry level [ 41 ]. The age of the bride is the main factor in marital negotiation, particularly in rural India. Our study found that a girl married to a husband older than her is more likely to pay dowry than an older girl or of similar age to her husband. One possible explanation by Maitra (2006) in his study on dowry inflation in India, argues that the excess supply of younger brides in the marriage market can leads to increase in dowry price when an older man marries the younger brides [ 43 ]. Another reason could be groom late age at marriage may be associated with pursuing of higher education [ 44 ]. Higher groom education is often found to be associated with higher dowry; this is because due to the competition among the brides for a particular groom leads to offers of higher and higher prices of dowries [ 41 ]. Also, suppose a potential bride’s cares about the qualities of the groom like commitment, sincerity, and loyalty which is important for a peaceful marriage, however if these qualities are unobservable and likely to be true, the brides may judge from the groom education as the signal of these qualities [ 45 ]. Hence, the bride’s family is ready to pay more dowries for a more educated person, not for higher education, but the underlying desirable qualities signals [ 45 ].

However, our study reveals contrasting results as girl education does not impact reducing the amount of dowry paid. Dalmia & Lawrence (2005) while examined the continued prevalence of dowry system in India explained that the amount of dowry or money transfer from brides and their families to grooms and their families does not decrease with increasing bride’s level of education [ 2 ]. Our results show that educated girls are more likely to pay dowry than the uneducated girls whose husband is also not educated. One possible explanation could be that the brides’ education is a good indicator of her household wealth. Hence, higher education and higher dowry are effects of bride’s household wealth [ 45 ]. Girl having a higher level of education tends to marry at a later age because they are more job aspirants than the lower educated girl [ 46 ]. The study of Dhamija & Chowdhury(2020) noted that a delay in marriage is associated with more education, low fertility, and possibly higher dowry for Indian women [ 47 ]. Findings by Field & Ambrus (2008) show that marriage opportunities curtail schooling investment suggest that the benefits to girls of delaying marriage come at a cost to the families, probably in higher dowry payments or less desirable spouses [ 48 ]. A more educated girl puts her parents in a difficult situation because it is very difficult to get a suitable boy for an educated girl. By virtue of her feminine status, a girl is expected to marry a man who should be in a better position and more educated than her. Drèze & Sen (1995) explained that if an educated girl marries a more educated boy, then the dowry payment will be more likely to increase with the groom’s education [ 49 ]. As Mathew (1987) explained, the expected dowry’s mean value increased with the prestige of the groom’s education [ 50 ]. Foreign degrees drew the highest dowries, Ph.D. degree received the lowest than engineering and medical degrees. However, on the other way, in the case of a rift, a more educated bride is more likely to walk out of the marriage, and the groom is bearing a greater risk of separation. So, given grooms value marital life’s stability or longevity, they will want to be paid a higher price for marrying with more educated brides as a premium for bearing the additional risk that such marriages entail [ 45 ].

The studies of Saroja & Chandrika (1991) found that as the bride, parental income increased, and dowry also increased [ 51 ]. This is consistent with our study’s findings, where the girls from the wealthier family were more likely to pay the dowry at marriage. The possible reason for this result is that the higher the parents’ income, the chance with which dowry demands can be agreed with ease, and more smoothly, the dowry payment can take place [ 52 ]. Our study shows that girls from Bihar were more likely to pay dowry than girls in Uttar Pradesh, this finding warrant qualitative study on dowry practices between these two states, because the information from the present study is not sufficient to draw a conclusion for this finding.

The study has some limitations as the study was conducted only in two Indian states, so the researchers could not establish a general conclusion from this study. Also, as our study in quantitative, we are unable to capture the individual social and cultural view point on dowry practice. Additionally, national representative data will be helpful for further study to understand the scenario of dowry practice in India, as because India is a country with diverse social and cultural practices, dowry will vary with respect to their cultural norms. Although the coefficient stability check revealed that the majority of the explanatory characteristics are insensitive to omitted-variable and selection bias, the results for age at marriage and state need to be interpreted with caution.

The study sought to explore the factors associated with the practice of dowry in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. It is evident from this study that the practice of dowry is still widespread, and the results show that increasing age, education, and household economic status of girls are associated with the likelihood of high dowry payment. Limitation of the dowry prohibition act is one of the causes of continued practices of dowry [ 53 ]. However, significant causes are deeply rooted in social and cultural customs, which cannot be changed using laws. Our study suggests that socio-economic development of women will not protect her from the dowry system, however higher dowry payment is more likely among women from better socio-economic class.

Supporting information

S1 fig. plot of logistic predicted probabilities vs. linear model..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s001

S2 Fig. Plot of logistic predicted probabilities vs. LPM.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s002

S1 Table. Logistic regression estimates for adolescents who paid dowry by background characteristics (15–19 years).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s003

S2 Table. Percentage distribution of adolescents who paid dowry by region, 15–19 years.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s004

S3 Table. Stepwise logistic regression estimates for adolescents who paid dowry by background characteristics (15–19 years).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s005

S4 Table. Summary statistics for LPM.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s006

S5 Table. Correlation index for robustness check of LPM.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258656.s007

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to Population Council, India for providing UDAYA data for research. This paper was written using data collected as part of Population Council’s UDAYA study, which is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

- 1. Conteh JA. Dowry and Bride-Price. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies. American Cancer Society; 2016. pp. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss548

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 5. Srinivas MN 1916–1999. Religion and society among the Coorgs of South India. Oxford University Press; 2003.

- 7. Mathew MV. Dowry Customs. The Encyclopedia of Women and Crime. American Cancer Society; 2019. pp. 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118929803.ewac0097

- 13. Chiplunkar G, Weaver J. Prevalence and evolution of dowry in India. 2019. http://www.ideasforindia.in/topics/social-identity/prevalence-and-evolution-of-dowry-in-india.html .

- 16. Sautmann A. Partner Search and Demographics: The Marriage Squeeze in India. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2011 Aug. Report No.: ID 1915158. 10.2139/ssrn.1915158.

- 20. Kumar R. Dowry System: Unequalizing Gender Equality. Gender Equality. Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2020. pp. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70060-1_21-1

- PubMed/NCBI

- 28. Anukriti S, Kwon S, Prakash N. Household Savings and Marriage Payments: Evidence from Dowry in India. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2018 May. Report No.: ID 3170253. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3170253 .

- 35. Osborne JW. Best Practices in Quantitative Methods. SAGE; 2008.

- 38. Oster E. PSACALC: Stata module to calculate treatment effects and relative degree of selection under proportional selection of observables and unobservables.

- 43. Maitra S. Can Population Growth Cause Dowry Inflation. Princeton University; 2006.

- 49. Dreze J, Sen A. India: Economic Development and Social Opportunity. OUP Catalogue. Oxford University Press; 1999. https://ideas.repec.org/b/oxp/obooks/9780198295280.html .

Dowry Inflation: Perception or Reality?

- Original Research

- Published: 16 March 2022

- Volume 41 , pages 1641–1672, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Jane Lankes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3158-4742 1 ,

- Mary K. Shenk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2002-1469 2 ,

- Mary C. Towner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0784-1860 3 &

- Nurul Alam ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1202-4451 4

428 Accesses

3 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

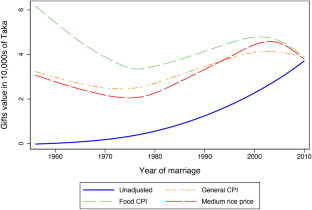

Research on South Asia has consistently documented increasing dowry amounts over the past several decades. Although recent studies have largely concluded this is due to an overall rise in prices, and therefore not a real increase per se, methodological limitations make this difficult to discern. In this paper, we assess: (1) if dowry amounts increased faster than the general inflation rate, and (2) how dowry amounts increased relative to income. Using data on rural Bangladesh from 1955 to 2010, we show trends in gross dowry, net dowry, and the ratio of dowry to income using multiple inflation adjustments. We find that only some aspects of dowries rose in certain periods, but the ratio of dowry to income steadily increased across time. We discuss implications of these results for understanding past contradictory findings and for gaining insight into the mechanisms by which widespread perceptions of dowry inflation may be maintained.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Consume more, work longer, and be unhappy: possible social roots of economic crisis.

Francesco Sarracino & Małgorzata Mikucka

Governor Baffi’s View on the Italian Great Inflation

Elena Seghezza

On the heterogeneity of dowry motives

Raj Arunachalam & Trevon D. Logan

Data Availability

Inflation data that support the findings of this study are included as part of the Online Resources. Data on dowry used in this paper are not de-identified, and therefore not available for public use.

Abe, N., Inakura, N., Tonogi, A. (2017). Effects of the entry and exit of products on price indexes. DP17-2

Ambrus, A., Field, E., & Torero, M. (2010). Muslim family law, prenuptial agreements, and the emergence of dowry in Bangladesh. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125 (3), 1349–1397.

Google Scholar

Amin, S., & Cain, M. T. (1997). The rise of dowry in Bangladesh. In G. W. Jones, J. C. Caldwell, R. M. Douglas, & R. M. D’Souze (Eds.), The continuing demographic transition (pp. 290–306). Oxford University Press.

Anderson, S. (2003). Why dowry payments declined with in Europe but are rising in India modernization. Journal of Political Economy, 111 (2), 269–310.

Anderson, S. (2004). Dowry and property rights . University of British Columbia.

Anderson, S. (2007a). The economics of dowry and brideprice. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21 (4), 151–174.

Anderson, S. (2007b). Why the marriage squeeze cannot cause dowry inflation. Journal of Economic Theory, 137 (1), 140–152.

Arunachalam, R., & Logan, T. D. (2016). On the heterogeneity of dowry motives. Journal of Population Economics, 29 (1), 135–166.

Aziz, A. (1979). Kinship in Bangladesh . International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research Bangladesh.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (1975). Statistical yearbook of Bangladesh, 1975 . Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (1980). Statistical yearbook of Bangladesh, 1980 . Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (1985). Statistical yearbook of Bangladesh, 1985 . Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (1990). Statistical yearbook of Bangladesh, 1990 . Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (1995). Statistical yearbook of Bangladesh, 1995 . Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (2000). Statistical yearbook of Bangladesh, 2000 . Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (2005). Statistical yearbook of Bangladesh, 2005 . Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). (2011). Statistical yearbook of Bangladesh, 2011 . Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

Barro, R. J. (1999). Inequality, growth, and investment . NBER.

Beckett, M., Da Vanzo, J., Sastry, N., Panis, C., & Peterson, C. (2001). The quality of retrospective data: An examination of long-term recall in a developing country. Journal of Human Resources, 36 (3), 593–625.

Bhat, P. N. M., & Halli, S. S. (1999). Demography of brideprice and dowry: Causes and consequences of the Indian marriage squeeze. Population Studies, 53 (2), 129–148.

Billig, M. S. (1991). The marriage squeeze on high-caste Rajasthani women. The Journal of Asian Studies, 50 (2), 341–360.

Billig, M. S. (1992). The marriage squeeze and the rise of groomprice in India’s Kerala state. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 23 (2), 197–216.

Boyce, J., & Ravallion, M. (1991). A dynamic econometric model of agricultural wage determination in Bangladesh. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 53 (4), 361–376.

Boticini, M., & Siow, A. (2003). Why dowries? The American Economic Review, 93 (4), 1385–1398.

Brunner, H.-P., Rahman, S. H., & Khatri, S. K. (2012). Regional integration and economic development in South Asia . Edward Elgar Publishing.

Caldwell, J. C., Reddy, P. H., & Caldwell, P. (1983). The causes of marriage change in south India. Population Studies, 37 (3), 343–361.

Caplan, L. (1984). Bridegroom price in urban India: Class, caste and ‘Dowry Evil’ among Christians in Madras. Man, New Series, 19 (2), 216–233.

Carroll, L. (1986). Fatima in the house of lords. Modern Law Review, 49 , 776–781.

Chari, A. V., & Maertens, A. (2020). What’s your child worth? An analysis of expected dowry payments in rural India. World Development . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104927

Article Google Scholar

Chiplunkar, G., & Weaver, J. (2019). Marriage markets and the rise of dowry in India. SSRN Journal . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3590730

Chowdhury, A. R. (2010). Money and marriage: The practice of dowry and brideprice in rural India.

Chowdhury, S., Mallick, D., & Chowdhury, P. R. (2017). Natural shocks and marriage markets: Evolution of Mehr and dowry in Muslim marriages. SSRN Journal . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2949111

Dalmia, S. (2004). A hedonic analysis of marriage transactions in India: Estimating determinants of dowries and demand for groom characteristics in marriage. Research in Economics, 58 (3), 235–255.

Dalmia, S., & Lawrence, P. G. (2005). The institution of dowry in India: Why it continues to prevail. The Journal of Developing Areas, 38 (2), 71–93.

Dalmia, S., & Lawrence, P. G. (2010). Dowry inflation in India: An examination of the evidence for and against it. Journal of International Business and Economics, 10 (3), 58–74.

Dang, G., Kulkarni, V. S., Gaiha, R. 2018. “Dowry death or murder?” The Sunday Guardian, March 17

Deaton, A. (2003). Prices and poverty in India, 1987–2000. Economic and Political Weekly, 38 (4), 362–368.

Deolalikar, A. B., & Rao, V. (1998). The demand for dowries and bride characteristics in marriage: Empirical estimates for rural south-central India. In K. Maithreyi, R. Sudershan, & A. Shariff (Eds.), Gender, population, and development (pp. 122–140). Oxford University Press.

Diamond-Smith, N., Luke, N., & McGarvey, S. (2008). ‘Too Many Girls, Too Much Dowry’: Son preference and daughter aversion in rural Tamil Nadu, India. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 10 (7), 697–708.

Edlund, L. (2000). The marriage squeeze interpretation of dowry inflation: A comment. Journal of Political Economy, 108 (6), 1327–1333.

Edlund, L. (2006). The price of marriage: Net vs. gross flows and the South Asian dowry debate. Journal of the European Economic Association, 4 (2/3), 542–551.

Epstein, T. S. (1973). South India: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Mysore villages revisited . Macmillan.

Esteve-Volart, B. (2004). Dowry in rural Bangladesh: participation as insurance against divorce . London School of Economics.

Fazalbhoy, N. (2005). Muslim women and property. In Z. Hasan & R. Menon (Eds.), The diversity of muslim women’s lives in India. Rutgers University Press.

Fluch, M., & Stix, H. (2005). Perceived inflation in Austria—extent, explanations, effects. Monetary Policy and the Economy, Q3 , 22–47.

Georganas, S., Healy, P. J., & Li, N. (2014). Frequency bias in consumers’ perceptions of inflation: An experimental study. European Economic Review, 67 , 144–158.

Giménez, L., & Jolliffe, D. (2014). Inflation for the poor in Bangladesh: A comparison of CPI and household survey data. Bangladesh Development Studies, 37 (1–2), 57–81.

Gondal, S. (2015). The dowry system in India—problem of dowry deaths. Journal of Indian Studies, 1 (1), 37–41.

Harrell, S., & Dickey, S. A. (1985). Dowry systems in complex societies. Ethnology, 24 (2), 105–120.

Hausman, J. (2002). Sources of bias and solutions to bias in the CPI. 9298

Hossain, M. (2017). Women’s education, religion and fertility in Bangladesh . Stockholms Universitet.

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). (2013). Rising wages in Bangladesh. Discussion paper 01249. Washington, D.C

Jayachandran, S. (2015). The roots of gender inequality in developing countries. Annual Review of Economics, 7 (1), 63–88.

Kaur, K. (2016). “How the practice of dowry makes life hell for a bride (and creates more social evils).” Youth Ki Awaaz, March 14

Khan, H. T. A., & Raeside, R. (2005). Socio-demographic changes in Bangladesh: A study on impact. BRAC University Journal, II (1), 1–11.

Kohler, U., & Kreuter, F. (2012). Data analysis using stata (3rd ed.). Stata Press.

Lindenbaum, S. (1981). Implications for women of changing marriage transactions in Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning, 12 (11), 394–401.

Logan, T. D., & Arunachalam, R. (2014). Is there dowry inflation in south Asia? An assessment of the evidence. Historical Methods, 47 (2), 81–94.

Maitra, S. (2007). Dowry and bride price. In W. A. Darity (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social sciences. Cengage Learning.

Makino, M. (2019). Dowry and women’s status in rural Pakistan. Journal of Population Economics, 32 , 769–797.

Matin, K.A. (2014). Income inequality in Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh

Melser, D., & Webster, M. (2021). Multilateral methods, substitution bias, and chain drift: Some empirical comparisons. Review of Income and Wealth, 67 (3), 759–785.

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. (1973). 25 years of Pakistan in statistics, 1947–1972 . Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

Rahman, P. M. M., Noriatsu, M., & Ikemoto, Y. (2013). Dynamics of poverty in rural Bangladesh . Springer.

Rama, M., Béteille, T., Li, Y., Mitra, P. K., & Newman, J. L. (2015). Addressing inequality in South Asia . The World Bank.

Rao, V. (1993a). Dowry ‘Inflation’ in rural India: A statistical investigation. Population Studies, 47 (2), 283–293.

Rao, V. (1993b). The rising price of husbands: A hedonic analysis of dowry increases in rural India. Journal of Political Economy, 101 (4), 666–677.

Rao, V. (2000). The marriage squeeze interpretation of dowry inflation: Response. Journal of Political Economy, 108 (6), 1334–1335.

Ravallion, M., & Sen, B. (1996). When method matters: Monitoring poverty in Bangladesh. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 44 (4), 761–792.

Roulet, M. (1996). Dowry and prestige in North India. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 30 (1), 89–107.

Sheel, R. (1997). Institutionalisation and expansion of dowry system in colonial North India. Economic and Political Weekly, 32 (28), 1709–1718.

Shenk, M. (2004). Embodied capital and heritable wealth in complex cultures: A class-based analysis of parental investment in urban South India. Research in Economic Anthropology , 23 , 307–33.

Shenk, M.K. (2005). How much gold will you put on your daughter?: A behavioral ecology perspective on dowry marriage. 05–07

Shenk, M.K. (2007). Dowry and Public Policy in Contemporary India: The Behavioral Ecology of a ‘Social Evil’. Human Nature , 18 , 242–63.

Shenk, M. K., Towner, M. C., Kress, H. C., & Alam, N. (2013a). Does absence matter?: A comparison of three types of father absence in rural Bangladesh. Human Nature , 24 , 76–110.

Shenk, M. K., Towner, M. C., Kress, H. C., & Alam, N. (2013b). A model comparison approach shows stronger support for economic models of fertility decline. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 110 (20), 8045–50.

Shenk, M. K., Towner, M. C., Starkweather, K., Atkisson, C. J., & Alam, N. (2014). The evolutionary demography of sex ratios in rural Bangladesh. In M. A. Gibson & D. W. Lawson (Eds.), Applied Evolutionary Anthropology: Darwinian Approaches to Contemporary World Issues (pp. 141–73).

Shenk, M. K., Towner, M. C., Voss, E. A., & Alam, N. (2016). Consanguineous marriage, kinship ecology, and market transition. Current Anthropology , 57 (Supplement 13), S167–S180.

Srinivas, M. N. (1984). Some reflections on dowry . Oxford University Press.

Srinivasan, S. (2005). Daughters or dowries? The changing nature of dowry practices in South India. World Development, 33 (4), 593–615.

Talwar Oldenburg, V. (2002). Dowry murder: The imperial origins of a cultural crime . Oxford University Press.

Uberoi, P. (1994). Family, kinship, and marriage in India . Oxford University Press.

Ul Kabir, M. (2019). “Stop the culture of dowry.” The Daily Observer, February 20

Upadhya, C. B. (1990). Dowry and women’s property in coastal Andhra Pradesh. Contributions to Indian Sociology, 24 (1), 29–59.

World Bank. (2008). Poverty assessment for Bangladesh: Creating opportunities and bridging the east-west divide . World Bank.

World Economic Forum. (2020). The global social mobility report 2020: Equality, opportunity and a new economic imperative . World Economic Forum.

World Food Programme (WFP). (2013). Bangladesh Food Security Monitoring Bulletin . World Food Programme.

Wright, A. (2020). Making kin from gold: Dowry, gender, and Indian labor migration to the gulf. Cultural Anthropology, 35 (3), 435–461.

Zhang, X., Rashid, S., Ahmad, K., & Ahmed, A. (2014). Escalation of real wages in Bangladesh: Is it the beginning of structural transformation? World Development, 64 , 273–285.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Sarah Damaske, Dr. David Nolin, Dr. Susan Schaffnit, Dr. Robert Lynch, Dr. Saman Naz, and the Penn State Population Research Institute Family Working Group for their helpful comments and insights. This research was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) to the Population Research Institute at The Pennsylvania State University for Population Research Infrastructure (P2C HD041025) and Family Demography Training (T32 HD007514); the National Science Foundation (BCS-0924630 & BCS-1839269); and The Pennsylvania State University Demography Graduate Program.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology and Criminology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA

Jane Lankes

Department of Anthropology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA

Mary K. Shenk

Department of Integrative Biology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA

Mary C. Towner

Centre for Population, Urbanization and Climate Change, ICDDR,B (International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh), Dhaka, Bangladesh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jane Lankes .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, to report.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 6220 KB)

Supplementary file2 (xlsx 218 kb), rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lankes, J., Shenk, M.K., Towner, M.C. et al. Dowry Inflation: Perception or Reality?. Popul Res Policy Rev 41 , 1641–1672 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-022-09705-7

Download citation

Received : 18 May 2021

Accepted : 14 February 2022

Published : 16 March 2022

Issue Date : August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-022-09705-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Gross dowry

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Europe PMC Author Manuscripts

The social construction of ‘dowry deaths’

Jyoti belur.

a Department of Security and Crime Science, UCL, 35 Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9EZ, UK

Nick Tilley

Nayreen daruwalla.

b Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action, Urban Health Centre, Room No. 110, Dharavi, Mumbai 400 017, India

Meena Kumar

c Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College and General Hospital, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Road, Sion West, Mumbai 400 022, India

Vinay Tiwari

d Burns, Plastic and Maxillofacial Surgery, VM Medical College and Safdarjang Hospital, New Delhi 110 029, India

David Osrin

e UCL Institute for Global Health, Institute of Child Health, 30 Guilford Street, London WC1N 1EH, UK

The classification of cause of death is real in its consequences: for the reputation of the deceased, for her family, for those who may be implicated, and for epidemiological and social research and policies and practices that may follow from it. The study reported here refers specifically to the processes involved in classifying deaths of women from burns in India. In particular, it examines the determination of ‘dowry death’, a class used in India, but not in other jurisdictions. Classification of death is situated within a framework of special legal provisions intended to protect vulnerable women from dowry-related violence and abuse. The findings are based on 33 case studies tracked in hospital in real time, and interviews with 14 physicians and 14 police officers with experience of dealing with burns cases. The formal class into which any given death is allocated is shown to result from motivated accounting processes representing the interests and resources available to the doctors, victims, victim families, the victim’s husband and his family, and ultimately, the police. These processes may lead to biases in research and to injustice in the treatment of victims and alleged offenders. Suggestions are made for methods of ameliorating the risks.

1. Introduction

In any jurisdiction, decisions have to be made about whether a death is natural or unnatural. If deemed unnatural, further decisions have to be made about whether it was accidental or non-accidental; and if non-accidental, whether self-inflicted or caused by a third party. In the event of death caused by a third party, decisions have to be made about whether anyone is culpable or not. Accounts of events leading up to the death are important in reconstructing the circumstances and cause, which in turn, inform the class into which it is placed. Those formally involved in classifying unnatural deaths vary by country and may include physicians, pathologists, district health officers, coroners, police officers, magistrates, public prosecutors, judges, and morticians ( Brooke, 1974 ).

This paper deals with classification in India of young women’s deaths as a result of burns into three broad classes of unnatural death – accident, culpable homicide and suicide – supplemented by a further class, ‘dowry death’, that is available when the deceased is female and has been married for less than seven years. It contributes to the wider literature discussed below on factors affecting the classification of equivocal deaths. Dowry deaths may occur by various means, including poisoning, hanging or burning. Recognition by lawmakers that women in India have traditionally been vulnerable to dowry-related abuse by their in-laws, sometimes resulting in their death, has led to the enactment of special legal provisions to prevent such abuse and cruelty. We examine the ways in which women’s deaths by burning do or do not come to be suspected as, treated as, and formally classified as dowry deaths. When a death is classified thus, the woman’s husband or other family members are automatically considered suspect and we examine the impact of this classification on the subsequent prosecution and conviction of perpetrators.

2. Background and literature review

‘Dowry deaths’ comprise a unique category of deaths in India. The custom of payment of dowry by the bride’s family to the prospective bridegroom’s family is ancient and widely prevalent. One of the many explanations for it is that it is a form of compensation to the groom’s family for sheltering the woman for life ( Ahmad, 2008 ). Other explanations include the concept of ‘ varadakshina ’: making a gift to the bridegroom to honour him. A third explanation invokes the Hindu Succession Act, which even after its amendment in 2005, confers less than equal property rights on the female child. As a result, customarily dowry is a one-time payment of ‘ streedhan ’ in lieu of her share of the family wealth at the time of her marriage ( Sharma et al., 2002 ; Anderson, 2007 ). In addition, given low employment prospects and low earning capacity for women in general, dowry becomes a rational investment in the groom’s prospects and his high future earning potential ( Van Willigan and Channa, 1991 ; Anderson, 2007 ). The more educated the woman, the more educated her potential partner ought to be and thus the higher the ‘price’ he commands in the negotiation process ( Van Willigan and Channa, 1991 ) as brides compete for more desirable grooms ( Anderson, 2007 ). What might have been, in an earlier time, a means of economically empowering a woman at the time of marriage, has metamorphosed in many cases into an instrument of exploitation of the bride’s family by the groom and/or his family.

When demands for cash, jewellery or goods remain unfulfilled in arranged marriages, or when the dowry is deemed unsatisfactory ( Banerjee, 2013 ), the resulting tensions may lead to the husband or his extended family harassing the woman, sometimes to the extent of killing her or creating such intolerable conditions that she decides to take her own life. Such deaths are termed ‘dowry deaths’ in the Indian Penal Code (defined in section 304B). A conundrum for classification purposes is that both homicides and suicides can constitute ‘dowry deaths’ ( Banerjee, 2013 ). Table 1 shows that the number of recorded dowry deaths has been growing very slowly, but it is unclear whether this is because the numbers have remained stable or reporting practices have remained unchanged. Nevertheless, the numbers are sufficiently high to generate concern.

Recorded dowry deaths in India ( Crime in India 2011 ).

Traditionally, dowry deaths (homicidal and suicidal) occurred through immolation. Indeed, even though in recent years dowry-related deaths as a result of poisoning or hanging may have been increasing, the term dowry death has become synonymous with ‘bride burning’ in popular discourse ( Bedi, 2012 ; Varma, 2012 ). In this paper we focus only on dowry deaths as a result of burns.

The appropriate criminal justice response to the death of a woman from burns follows India’s Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973. Section 174 outlines the response to suicide, homicide, accident, or death under suspicious circumstances, and is applied particularly to women within seven years of marriage. The police are to report the incident to a magistrate (who follows section 176 and is empowered to hold an inquest), and, with at least two people from the neighbourhood in attendance, to report on the appearance of the body and the apparent cause of death.

The Indian Penal Code (IPC) was amended specifically to deal with dowry-related violence, cruelty and dowry deaths in 1983. Section 498A IPC penalizes harassment (or any kind) of a woman by her marital family. Unnatural death of a woman within seven years of marriage attracts penal provisions of section 304B IPC. This section defines dowry death as the unnatural death of a woman following harassment or cruelty by her husband or his relatives in connection with a demand for dowry. In cases where a woman commits suicide, as a result of harassment (not related to dowry) from her husband or his relatives, section 306 IPC addresses abetment of suicide. If it is a dowry-related suicide both sections 304B and 306 are applicable.

Finally, amendments to the Indian Evidence Act (IEA) introduced a presumption of abetted suicide, which is a form of dowry death, and a separate presumption of dowry death ( Ravikanth, 2000 ). Section 113A of the IEA gives the court the powers to presume abetment on the part of the husband or his relatives if a woman commits suicide within 7 years of marriage, if the husband or his relatives subjected her to cruelty. Section 113B provides that the courts ‘shall’ presume dowry death in case of unnatural death of a woman within 7 years of marriage, where prior to death either the husband or his relatives subjected the woman to harassment or cruelty. The 91st Report of the Law Commission enumerated the need for such a presumption in order to ensure that an unnatural death of a woman will entail “the need for investigation by the police or an inquest by the Magistrate into the cause of death becomes strong” ( LCI, 1983 : 4).

2.1. Classifying dowry deaths

The methods of – and difficulties entailed in – classifying unnatural deaths have been highlighted in previous research ( Atkinson, 1971 ; Taylor, 1982 ). Atkinson’s (1971 ; 166) research highlighted the fact that “technological, cultural and administrative influences” on the production of official mortality statistics (referring to suicide statistics) were seldom acknowledged. He suggested that the study of the processes – social and legal – by which official classifications of death are produced can be useful in placing official statistics in perspective and in identifying whether any systematic, non-random biases affect their production.

We explore the process of classification of death of women by burning within the conceptual framework of ‘death brokering’ ( Timmermans, 2005 ), which refers to activities of authorities to render individual deaths culturally appropriate. Timmermans (2005) acknowledges that ‘death brokering’ of unexpected deaths by forensic experts in late modern Western societies involves classifying “profoundly equivocal deaths into contested moral categories”. These forensic experts employ a variety of “cultural scripts” to render sense to these seemingly senseless deaths (2005: 995). In India, the police are primary ‘death brokers’ and employ culturally appropriate scripts to classify death of a woman within seven years of marriage as dowry-related (or not). This involves police officers engaging in a set of social negotiations with the victim, her natal (family of birth) and marital (husband’s family) families, health practitioners, and forensic experts to render the definition of an individual death socially and legally acceptable. How these cultural scripts come to be constructed becomes vital in understanding how dowry deaths are ‘brokered’.

2.2. Burning as a cause of women’s deaths in India

Fire-related injuries are the leading cause of death among women in India in the age group 15–34 years ( Sanghavi et al., 2009 ). Public health research has focused on the causes of burn-related deaths among women, their patterns and trends ( Sawhney, 1989 ; Sharma et al., 2002 ; Ambade and Godbole, 2006 ; Peck et al., 2008 ; Ahuja et al., 2009 ; Sanghavi et al., 2009 ). Collectively the research literature suggests that accidents are responsible for a majority of burns, followed by suicide attempts and finally by homicidal attempts ( Sawhney, 1989 ; Mago et al., 2005 ; Ambade and Godbole, 2006 ; Ambade et al., 2007 ; Kumar et al., 2007 ; Ahuja et al., 2009 ; Chakraborty et al., 2010 ; Ganesamoni et al., 2010 ). Shaha and Mohanty’s (2006) analysis of victim and burn characteristics, based on post mortem reports, found that a majority of female victims were in the age group 18–26 years; were relatively uneducated; were from lower socio-economic positions; and were predominantly Hindu. In the cases studied burns mostly occurred during the daytime, in closed spaces, and kerosene was the main medium used.

While some epidemiological studies of deaths by burning acknowledge the possibility that misclassification of death can occur ( Sanghavi et al., 2009 ), analyses are still conducted on the presumption that the classification can be and is unambiguous. However, the classification of a woman’s death within seven years of marriage is far from straightforward in India. It is especially hard to distinguish between some kinds of intentional and accidental deaths. Neeleman and Wessely (1997) (citing Rockett and Smith, 1995 ) suggest that some methods of death such as drowning (‘soft methods’) are less easily classified as definitely suicidal than others such as hanging (‘hard methods’). Extending their logic, we suggest that death by burning is a ‘soft method’ in terms of ambiguity in determining whether it was accidental or intentional. Public health studies support the suggestion that classification of death by burning is difficult ( Sanghavi et al., 2009 ).

The legal, moral, and forensic, ambiguities involved in classifying an unnatural death suicide, as discussed in traditional psychological and sociological research ( Durkheim 1897 , Stengel, 1964 ; Douglas, 1970 ; Atkinson, 1971 ; Taylor, 1982 ; Pescosolido and Mendelsohn, 1986 ; Neeleman and Wessely, 1997 ; Lindquist and Gustaffsson, 2002 ; Shiner et al., 2009 ; Scourfield et al., 2010 ; Claassen et al., 2010 ), are intensified in the socio-legal context of classifying unnatural deaths of women within seven years of marriage in India, regardless of the cause of death. The literature shows that factors influencing death investigations include racial, religious, cultural, and family concerns which affect medico-legal verdicts ( Carpenter et al., 2011 ; Huguet et al., 2010 ; Timmermans, 2006 ). This study contributes to the wider literature on death classification.

2.3. Formal procedures for classifying women’s deaths by burning

The formal procedure for classifying the death of a woman within seven years of marriage and the available classes and relevant statutes are shown in Fig. 1 .

Official procedure for classification of death of women from burns.

When a woman suffers burns she is, more often than not, taken to the hospital. The police are informed by the hospital and a ‘medico-legal’ case is established. The police attend the hospital to gather available information there. The police secure the scene of the incident. A magistrate is called and records a ‘dying declaration’ (DD) that provides an authoritative victim account of the circumstances surrounding her burns. The DD may be taken by someone else, normally a doctor or police officer, if the magistrate is unable to record it, for example, because the woman fails to survive long enough. The magistrate holds an inquest, drawing on the DD, a post-mortem and statements from the women’s family. Finally, the police classify the death taking advice from findings from the magistrate’s inquest, into one of the categories shown in Fig. 1 .

The inclusion of dowry deaths as a formal offence category in India reflects both an acknowledgement of and a means of trying to deal with violence against women. This is as a result of the way sexual divisions are played out in the sub-continent. Moreover, the emphasis on the accounts given by dying women themselves represents an effort to give them an authoritative voice, where they would clearly otherwise have none in bringing perpetrators to justice. The victim can act as her own witness. In the expectation that she is likely to die she may be presumed to have no vested interest in misleading the magistrate over the course of events leading to her demise. The testimony in her account is therefore granted special privilege.

3. Data and methods

A total of 59 semi-structured interviews were conducted with three groups of respondents: women (and their family members) admitted to two major burns units over two months (May–June) in 2012, health care providers, and police officers. The research sites were two of the largest burns units in two of India’s largest cities, Delhi and Mumbai. The researchers had working relationships with the hospital and police in Mumbai and chose the hospital in Delhi with the largest burns unit in the country as comparator.

Three research assistants were attached to the burns units in both hospitals to conduct case studies for a period of 45 days. They interviewed 33 people, including admitted women who were capable of interview (with family members in some cases), or family members of those unable to take part in an interview. In addition, 14 semi-structured interviews were undertaken with doctors, forensic pathologists and nurses by the third and last authors, and 14 with police officers by the first author. Sampling was purposive.

All interviews took place in private areas, were audio-recorded and transcribed in full. Two interviews with practitioners were conducted with two respondents together. Equal numbers of clinicians, including doctors, forensic pathologists and nurses working in the burns wards were interviewed in each city. Eight police officers in Mumbai and six in Delhi were interviewed. Officers working in five police stations in each city, where cases of women with burns had been investigated in the past year, were selected and officers of the rank of Assistant Commissioners and Inspectors with relevant investigative experience were interviewed.

Interviews were conducted in one or more languages, including English, Hindi and Marathi. All the interviews were translated literally into English and then transcribed. As a result, the quotes are sometimes in non-standard English because they are reported verbatim. Framework analysis ( Ritchie and Spencer, 1994 ; Srivastava and Thomson, 2009 ) was used to examine the processes by which the police classify deaths. The analysis consisted of five steps: classifying the interview material into codes and categories; identifying a thematic framework; indexing; mapping to explore links between various themes; and interpreting and analysing emerging links from the data. The first three and last authors were extensively involved in this process.

4. Ethical approval

The project was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College and General Hospital (IEC/14/12), the Ethical Committee of VM Medical College and Safdarjang Hospital (58-11-EC4/8), and the UCL Research Ethics Committee (3546/002).

5. Findings

Respondents largely agreed on the early processes described in Fig. 1 . Medico legal cases were registered in every event of burns. Police took cognizance of all serious burns patients who might die and whose deaths could potentially be classified as dowry-related (female within seven years of marriage), and every attempt was made to record their dying declaration, preferably by a Magistrate. There was no evidence that some were filtered out earlier. However, there was disagreement between the police and other interviewees over whether scenes of incidents were always visited and secured promptly.

In the following sections interviewees’ perceptions on the various strands that influence police classification are drawn together.

5.1. The victim’s account: her dying declaration

The DD is treated as an authoritative statement for classifying the incident along lines summarized in Fig. 1 , in the event that the woman dies. The DD usually follows one of three major narratives, with obvious implications for classification:

- My clothes caught fire in a kitchen accident.

- I was attempting to commit suicide by setting myself on fire.

- My husband and/or his family set me on fire.

What became clear, however, is that the woman’s account in her DD is constructed in ways shaped by the situation in which it is made and is also liable to change as her situation changes. For the 33 women involved in our case studies, 22 incidents were described by themselves or their relatives as accidental, five as suicidal, and six as homicidal. Interviewees claimed that, more often than not, in her first statement the woman usually explains her burns as a kitchen accident. Subsequently, when her parents arrive at the hospital, they encourage her (if she is still alive) to tell the truth about the incident,

Several interviewees, including eight clinicians, nine police officers and four victims or their families, mentioned that often initial accounts given by the victim change over time. As one interviewee put it:

“… there are quite a few patients who want to change their statements. Initially they come, the in-laws are involved in burning, the in-laws are with them, so initially they pretend that it was an accident. Two days later the parents of the girl arrive, then she has the guts to say, no, it was not an accident, it was this.” (SKII Doctor, Delhi).

While families sometimes provide the woman with the necessary courage to tell the truth, at other times their influence can be more pernicious. One interviewee described her experience:

“To the extent that occasionally I feel that the girl or woman who’s burned is kind of tutored by her family members to say that this was homicide. Change the statement, though it really might be suicide. Simply put the net on the in-laws.” (M3, Clinician, Mumbai).

This view was reinforced by a police officer, who interpreted the motivations behind why such changes in account might happen,

“Mostly it is like this – on the first day she had not made any allegations and then there are not very good relations between the two families and we know that the in-laws were troubling her. The girl’s parents tell her, why did you say like this, why did you not tell the truth and all that. So the girl says, ok, I will tell the truth and then the family members come and register a report saying that please record our daughter’s statement again.” (P11, Inspector, Delhi)

One factor at work in the victim’s initial account of her burns was deemed to be fear: fear of the in-laws who are around the victim at the time of admission, or fear of the future, how she would return to her marital home or who would look after her children. As time passes, other influences came into play. One physician, who disbelieved many of the initial accounts he heard, said of one woman,

“… she was almost 80 to 90 percent burnt and that time she was telling it was accidental. I sent all the relatives outside and I spoke with her ki [that] you don’t worry we all are there. Whatever has happened you please tell us. So that time she told ki ‘family members, my mother-in-law and my husband they burnt’.” (M2, Doctor, Mumbai).

A police officer said that,

“Women have a psychology that they are very emotional – maybe that is that they have emotions that why should I trouble my husband, my children need looking after, I might survive or not. So she tells the doctor no – it was a mistake, it was an accident … After a couple of days her family members meet her, she discusses this with them and then her version changes. I have seen many instances of this where the woman has changed her version thrice in three days or twice in four days. (P11, Inspector, Delhi)

Two noteworthy points are raised by the officer: first, that whether the woman will ‘tell the truth’ depends upon the relations between the two families; and second, that the woman’s family is expected to take the initiative and contact the police with a request to record her statement again.

5.2. Woman’s natal family accounts of cause of death

The woman’s family’s testimony is of vital importance in both the inquest and subsequent classification of death by the police. Even if she has made no accusations in her DD, but her near relatives allege harassment, officers asserted that they had no choice but to register a case against the husband or in-laws. Respondents suggested that the accounts by family members often failed accurately to report the circumstances surrounding the woman’s death. They might choose to portray it as an accident or allege dowry death, depending upon circumstances and their situation.

When asked to explain why victims or their families assert that the cause of burns was accidental when it was probably not the truth, one interviewee said,

“Her father-in-law says that. Don’t register the FIR (First Information Report) … I said why should we harass them [in-laws], we will do according to the wishes of daughter, if she says I have to go there [to her marital home], why FIR? Why should we break her home?” (R1b, Father of patient, Delhi)

Clearly, this interviewee did not report the real cause of burns as being homicidal because of pressure from his daughter’s in-laws and because his daughter wanted to return to her marital home when (and if) she recovered. Initiating criminal proceedings would jeopardise her return to her husband’s home. Another reason mentioned for reluctance on the part of the victim or her family to accuse the in-laws of homicidal intent, even if true, was concern over the upbringing of children. A consultant clinician in the burns ward in Delhi said,

“The in-laws say “We won’t look after your child if you open your mouth.” So because of fear the patients do not say what actually happened.” (SK1, Consultant, Delhi)

Previous research has shown that natal families use allegations of dowry death to conduct negotiations with the woman’s in-laws during the run-up to the trial to share or transfer the upbringing of the children ( Berti, 2010 ). On the other hand, sometimes it was also the case that the victim’s family allege harassment because,