CLINICAL CASE

Differential diagnosis and initial evaluation, clinical case (continued), definition and classification of hes, approach to therapy, eosinophil-targeted therapies and hes, predictors of response to targeted therapy, potential risks of eosinophil depletion, conclusions, acknowledgment, conflict-of-interest disclosure, off-label drug use, approach to the patient with suspected hypereosinophilic syndrome.

- Split-Screen

- Request Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

- Open the PDF for in another window

Amy D. Klion; Approach to the patient with suspected hypereosinophilic syndrome. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2022; 2022 (1): 47–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/hematology.2022000367

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Visual Abstract

Hypereosinophilic syndromes (HES) are a heterogenous group of rare disorders with clinical manifestations ranging from fatigue to life-threatening endomyocardial fibrosis and thromboembolic events. Given the broad differential diagnosis of HES, a comprehensive approach is needed to identify potential secondary (treatable) causes and define end-organ manifestations. Classification by clinical HES subtype is also useful in terms of assessing prognosis and guiding therapy. Corticosteroids remain the mainstay of initial therapy in the setting of acute, life-threatening PDGFR mutation-negative HES. Whereas the recent availability of eosinophil-targeted therapies with extraordinary efficacy and little apparent toxicity is changing the treatment paradigm, especially for idiopathic HES and overlap syndromes, questions remain unanswered regarding the choice of agent, impact of combination therapies, and long-term effects of eosinophil depletion. This review provides a case-based discussion of the differential diagnosis of HES, including the classification by clinical HES subtype. Treatment options are reviewed, including novel eosinophil-targeted agents recently approved for the treatment of HES and/or other eosinophil-associated disorders. Primary (myeloid) disorders associated with hypereosinophilia are not be addressed in depth in this review.

To describe the heterogeneity of clinical presentations of hypereosinophilia

To discuss the approach to targeted therapy of hypereosinophilic syndrome

A 38-year-old previously healthy woman presented with intermittent but intense pruritus without rash. The pruritus initially involved only her ankles but subsequently spread up her legs with accompanying angioedema of the thighs and buttocks that prevented her from being able to wear pants. Antihistamines were ineffective, and a short course of solumedrol prescribed for sinusitis did not relieve the pruritus or swelling. A dermatologist prescribed oral and topical antibiotics for presumed folliculitis without improvement. One year after the onset of the symptoms, a complete blood count was performed and revealed anemia, thrombocytopenia (platelets 34 000), and eosinophilia (14.0 × 10 9 /L). She was referred to hematology.

Eosinophilia, defined as an absolute eosinophil count (AEC) >0.45 × 10 9 /L, is quite common, occurring in 1% to 2% of the general population. 1 In contrast, hypereosinophilia (HE; AEC ≥1.5 × 10 9 /L) is extremely rare, with an estimated incidence of 0.315 to 6.3 per 100 000 in the United States. 2 The potential etiologies of eosinophilia (including HE) are varied and include allergic, infectious, neoplastic, genetic, and immune disorders ( Table 1 ). Moreover, clinical symptoms are extremely heterogeneous. Dermatologic, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal manifestations are most frequently reported, but any organ system can be affected, and progression can occur over time without effective therapy. 3 A careful and complete history and physical examination, including prior complete blood counts (if available), medication and travel history, assessment of cancer risk factors, and family history, is essential to narrow the differential. Initial laboratory and diagnostic testing should include complete blood count with differential, routine chemistries, serum immunoglobulin levels, B12 and tryptase, and assessment of lymphocyte clonality and phenotype. If there is a possible history of Strongyloides exposure, no matter how remote, serologic testing should be performed and/or empiric ivermectin (150 µg/kg × 1 dose) administered to prevent potentially fatal hyperinfection syndrome. Bone marrow biopsy and chest/abdomen/pelvis imaging should be strongly considered in any patient with AEC ≥1.5 × 10 9 /L and no clear secondary cause of the HE. Additional testing, including testing for parasitic infections other than Strongyloides , should be guided by the clinical history and disease manifestations.

Disorders associated with marked eosinophilia

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

A bone marrow biopsy specimen was hypercellular with increased eosinophils and plasma cells. Testing for FIP1L1::PDGFRA was negative. She was treated with prednisone 60 mg daily for presumed idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with clinical and hematologic improvement. However, as the prednisone was tapered, the eosinophilia, pruritus, and edema returned. She was referred to Mayo Clinic for further evaluation, which included an indeterminate serologic test for Strongyloides . She was treated with 2 doses of ivermectin and a 2-week course of albendazole. During this time, the prednisone was slowly tapered despite a rising AEC, peaking at 26.0 × 10 9 /L on prednisone 5 mg every other day, and recurrent symptoms. The prednisone dose was increased to 25 mg daily, and hydroxyurea therapy (500 mg twice daily) was initiated. This was ineffective, and she was referred to the National Institutes of Health for further evaluation.

At the time of referral, she complained of fatigue, swelling, and extreme pruritus. Physical examination revealed symmetric nonpitting edema of the thighs and excoriations predominantly on the lower legs. Laboratory testing was notable for AEC 3.01 × 10 9 /L; platelets 114 000; markedly elevated IgG, IgM, and IgE; and normal serum B12 and tryptase. Computed tomography (CT) scan was notable for borderline splenomegaly and minimal diffuse lymphadenopathy. Repeat bone marrow again showed only increased eosinophils. Mast cells were not increased, and testing for D816V KIT was negative. T-cell receptor testing by polymerase chain reaction showed a clonal pattern, and flow cytometry was notable for an aberrant CD3 – CD4 + CD10 + T-cell population, consistent with a diagnosis of lymphocytic variant hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). B-cell clonality studies were negative. She was started on interferon α 1 mU daily with resolution of eosinophilia, platelets >50 k and symptomatic improvement.

The definition of HES has evolved over time since Chusid's landmark description of 14 patients with idiopathic HE and varied clinical manifestations in 1975. 4 Whereas the current World Health Organization definition uses the term HES to describe only idiopathic HE with clinical manifestations, 5 a recently updated consensus definition provides a broader approach that recognizes the overlap in clinical presentation between idiopathic and other types of HES, the imperfect sensitivity and specificity of available diagnostic testing, and the identification of new etiologies of HES over time 6 ( Table 2 ). In this consensus definition, a diagnosis of HE requires AEC >1.5 × 10 9 /L on 2 examinations at least 1 month apart (to exclude laboratory error but allow diagnosis without a delay of 6 months) and/or tissue HE (to recognize the arbitrary nature of the AEC cutoff in the setting of clear eosinophil-mediated disease). HES is defined as HE with evidence of end-organ dysfunction attributable to the eosinophilia, irrespective of the cause. To address the heterogeneity of disorders included in this umbrella definition of HES and help guide diagnostic procedures and therapeutic choices, the following clinical subtypes have been proposed ( Table 3 ) 7 : (1) myeloid HE/HES (suspected or proven eosinophilic myeloid neoplasm, including those associated with rearrangements of PDGFRA and other recurrent molecular abnormalities), (2) lymphocytic variant HE/HES (presence of a clonal or phenotypically aberrant T-cell population that produces cytokines that drive the eosinophilia), (3) overlap HES (single-organ-restricted eosinophilic disorders and clinically defined eosinophilic syndromes that overlap in presentation with idiopathic HES; ie, eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis), (4) associated HE/HES (in the context of a defined disorder, such as a helminth infection, neoplasm, immunodeficiency, or hypersensitivity reaction), (5) familial HE/HES (occurrence in >1 family member excluding associated HE/HES), and (6) idiopathic HE/HES (unknown cause and exclusion of other subtypes).

Definitions of hypereosinophilic syndrome

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CEL-NOS, chronic eosinophilic leukemia-not otherwise specified; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; WHO, World Health Organization.

Initial assessment of the patient with hypereosinophilia

Can be dramatically affected by corticosteroid therapy.

Not all patients with LHES will have clonal or aberrant T-cell populations detectable by routine testing.

CT, computed tomography; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis and polyangiitis; MHES, myeloid variant hypereosinophilic syndrome; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NGS, next-generation sequencing; PET, positron emission tomography.

Lymphocytic variant HES (LHES) was first described in 1994 in a 30-year-old man with pruritus and cough and a large CD2 + CD3 – CD4 + T-cell population that produced interleukin (IL) 4 and IL-5 in response to stimulation. 8 Since that time, other surface phenotypes have been described, and there have been several informative case series describing the clinical and laboratory findings of patients with LHES. 9 - 11 Equally frequent in males and females, LHES most often presents with dermatologic manifestations. That said, any organ system can be involved, and some patients with asymptomatic HE have clonal aberrant T-cell populations indistinguishable from those with symptomatic LHES. Serum IgM, IgE, and serum and thymus and activation-regulated chemokine levels are elevated in most patients with LHES and can provide useful diagnostic clues. 12 Whereas the gold standard for diagnosis of LHES is identification of a clonal and/or aberrant population of T cells producing type 2 cytokines, intracellular flow cytometry is not available at most centers, and the diagnosis most often relies on a compatible clinical picture and demonstration of a clonal and/or aberrant T-cell population in the peripheral blood. Expanded surface phenotyping is often necessary to demonstrate and/or confirm the aberrant population. 12 , 13 It is important to recognize that the surface phenotype of the clonal population in LHES can be indistinguishable from that seen in T-cell malignancies (especially angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma). 14 Thus, LHES is a diagnosis of exclusion. Moreover, progression of LHES to a lymphoid malignancy occurs in approximately 10% of patients, sometimes after many years of stable disease. 15 - 17 Consequently, at a minimum, patients with LHES should undergo assessment for occult lymphoma at diagnosis and in the setting of an increase in size of the clonal T-cell population or development of resistance to previously effective therapy.

Despite the differences in definitions, the general approach to HE is very similar between World Health Organization and the consensus group ( Figure 1 ). Since secondary causes of eosinophilia, such as helminth infection, typically require a different therapeutic approach, these should be considered early in the diagnostic process. If an underlying etiology is identified or highly suspected, specific treatment should be initiated. Primary (clonal/neoplastic) eosinophilia is also important to identify early due to prognostic and therapeutic implications. 18 Finally, the presence and severity of clinical manifestations should be assessed as this will affect both the nature and urgency of therapeutic intervention. For example, careful monitoring without therapy may be appropriate for asymptomatic HE without evidence of end-organ involvement (hypereosinophilia of undetermined significance), 19 whereas urgent intervention is needed in the context of myocarditis or thromboembolism.

Initial approach to the patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Prednisone remains the mainstay of therapy in the acute setting for severe and/or life-threatening manifestations of HES. If the eosinophilia does not dramatically decrease within 24 to 48 hours, additional therapy should be considered depending on the suspected clinical subtype (ie, imatinib for patients with clinical findings suggestive of a myeloid neoplasm, cyclophosphamide for patients with manifestations suggestive of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis). The use of eosinophil-targeting biologics in the acute setting remains controversial but is supported by case reports and small series. 20 Once the patient is stable, further evaluation should focus on the identification of the most likely clinical subtype ( Table 3 ). With the exception of patients with myeloid HES, 18 most patients with symptomatic HES respond rapidly to corticosteroid therapy, although toxicity and resistance limit the utility of this therapy in the long term. 3 Conventional second-line agents, including hydroxyurea and interferon α, are fraught with similar issues but have advantages in select populations/clinical HES subtypes ( Tables 3 and 4 ).

Selected therapeutic agents for the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes

Mepolizumab, which is approved for the treatment of HES, has better efficacy and lower toxicity but is expensive and not available in all countries.

Primary outcome of the phase 3 trial of mepolizumab for PDGFRA -negative, steroid-responsive HES in adults: reduction of disease flares over a 32-week period in patients receiving mepolizumab and stable background therapy compared with those receiving placebo and stable background therapy. 21 Dual primary outcomes of the phase 3 trial of mepolizumab for relapsing or treatment-refractory EGPA in adults: total accrued weeks of remission, defined as a Birmingham vasculitis score of 0 on less than 4 mg prednisone daily for 52 weeks, and proportion of participants in remission at weeks 36 and 48. 23

CS, corticosteroid; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis and polyangiitis; MHES, myeloid variant hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Over the next 4 years, she remained relatively stable on interferon α therapy with partially controlled symptoms, AEC <1.0 to 2.0 × 10 9 /L, but was unable to taper prednisone below 12.5 mg daily without significant worsening. Her clonal T-cell population increased to approximately 30% of total lymphocytes, prompting repeat CT scan and bone marrow, which were unchanged, and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan, which showed no evidence of lymphoma. She was enrolled on a phase 2 placebo-controlled trial of benralizumab.

The availability of biologics targeting IL-5 (mepolizumab and reslizumab) and its receptor (benralizumab), all of which are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of asthma, has profoundly altered the approach to the treatment of idiopathic, lymphocytic, and overlap variants of HES. Whereas corticosteroids are still recommended as initial therapy in most cases, eosinophil-targeting biologics have shown excellent safety and efficacy profiles in the treatment of HES, 21 - 23 leading to the recent approval of mepolizumab for HES and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis and the initiation of phase 3 trials of benralizumab for the same indications. Of note, mepolizumab and reslizumab cause maturational arrest in the bone marrow with dramatic but incomplete reduction of blood and tissue eosinophilia. In contrast, benralizumab, an afucosylated monoclonal antibody to IL-5 receptor α, targets eosinophils, basophils, and their precursors for antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, resulting in complete (or near- complete) depletion in all tissues studied to date. Although definitive data are lacking, what little information is available concerning the efficacy of these agents in myeloid forms of HES is discouraging. 22 , 24 , 25

Other agents that directly or indirectly decrease blood and tissue eosinophilia are in development for HES and/or approved for select eosinophilic indications ( Table 4 ). These include lirentelimab (an afucosylated antibody to Siglec-8 that depletes eosinophils and basophils and inhibits mast cell activation), 26 dupilumab (a monoclonal antibody to IL-4 receptor α approved for asthma, atopic dermatitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, and eosinophilic esophagitis that blocks IL-4 and IL-13 signaling and eotaxin-mediated tissue migration of eosinophils), 27 and dexpramipexole (an orally available small molecule that causes maturational arrest and eosinophil depletion through an unknown mechanism). 28

After an initial response to benralizumab, interferon α was discontinued. Two weeks later, eosinophilia and severe symptoms returned. Benralizumab was discontinued, and she was started on prednisone 60 mg in addition to interferon α. She subsequently developed acute sensorineural hearing loss that resolved with cessation of interferon α and a prednisone burst. Cyclosporine was added. Due to persistent symptoms and inability to taper prednisone below 20 mg daily, she was enrolled on a phase 3 placebo-controlled trial of mepolizumab. Her symptoms improved, and she was able to taper prednisone to 9 mg daily, at which point she developed cough and shortness of breath requiring hospital admission. Evaluation was notable for ground-glass infiltrates, diffuse lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly. Lymph node biopsy (approximately 10 years after her initial diagnosis) revealed angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. She was treated with CHOP-R (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate [Oncovin], prednisone, and rituximab) with transient response. Romidepsin was added, but she developed right-sided heart failure and died of respiratory failure.

There is currently little available information to guide the initial choice of biologic for a patient with HES. Although AEC has been shown to predict response to IL-5/IL-5 receptor targeting agents in patients with asthma, neither serum IL-5 levels nor eosinophil count at initiation of treatment were found to predict response to mepolizumab in the phase 3 trial in patients with PDGFRA -negative, corticosteroid-responsive HES, 29 and neither historic peak nor baseline AEC predicted response to benralizumab in a phase 2 trial in patients with PDGFRA -negative, treatment-refractory HES. 22 The only consistent finding across trials has been differences across clinical HES subtypes, with decreased response rates and/or increased relapse rates in patients with lymphocytic variant HES 22 , 25 , 30 - 32 ( Figure 2 ). That said, responses to the different biologics targeting the IL-5 axis are variable, and a lack of response to one agent does not preclude success with another. 32

Clinical subtypes of hypereosinophilic syndrome: frequency distribution of 554 patients referred to the National Institutes of Health for unexplained eosinophilia. EGID, eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis and polyangiitis; EO FASCIITIS, eosinophilic fasciitis.

Over the past 10 to 15 years, it has become increasingly apparent that eosinophils play an important role in homeostatic processes, including tissue remodeling, tumor surveillance, metabolic function, and immunoregulation. 33 Although this has led to theoretical concerns about the effects of long-term therapy with biologics and other agents that significantly reduce eosinophils in blood and tissue, data to date suggest that eosinophil depletion in humans is safe. 25 , 34 - 37 Importantly, there have been no reports of an increased incidence of malignancy or autoimmune disease related to eosinophil depletion, and even subtle immunologic consequences demonstrated in murine models, such as impaired vaccine responses, have not been replicated in human studies. 22 , 34 , 38 , 39 This lack of significant toxicity is likely due, at least in part, to the redundancy and complexity of the human immune system, which raises potential concerns as the number of targeted therapies and biologics increases and the use of combination therapies becomes more common. It is also important to note that toxicities may be restricted to specific populations or clinical settings (ie, patients exposed to helminth infection, infected with coronavirus disease 2019, or at high risk of autoimmune disease), for which there are little to no prospective data to date.

Whereas eosinophilia is common in the general population, HES are a heterogeneous and complex group of rare disorders with clinical manifestations that span the range of medical subspecialties. Comprehensive clinical evaluation is necessary both to assess end-organ manifestations and determine the most likely etiology and/or clinical subtype of HES, as this information has important therapeutic and prognostic implications. Although corticosteroids continue to be first-line therapy in most situations, novel targeted therapies are rapidly replacing conventional cytotoxic and broad immunosuppressive agents as second-line agents of choice for the treatment of eosinophil-associated clinical manifestations. Despite the lack of safety signals to date, vigilance and prospective studies are needed to confirm the safety of these agents over the long term and to assess the impact of blocking multiple lineages and/or pathways on homeostatic processes.

This work was funded by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Amy D. Klion: no competing financial interests to declare.

Amy D. Klion: all of the drugs discussed, with the exception of imatinib and mepolizumab, are considered off-label for the treatment of hypereosinophilic syndromes.

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Email alerts

Affiliations, american society of hematology.

- 2021 L Street NW, Suite 900

- Washington, DC 20036

- TEL +1 202-776-0544

- FAX +1 202-776-0545

ASH Publications

- Blood Advances

- Hematology, ASH Education Program

- ASH Clinical News

- The Hematologist

- Publications

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 05 September 2019

Acute kidney injury secondary to thrombotic microangiopathy associated with idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome: a case report and review of the literature

- Diana Curras-Martin 1 ,

- Swapnil Patel 1 ,

- Huzaif Qaisar 1 ,

- Sushil K. Mehandru 1 ,

- Avais Masud 1 ,

- Mohammad A. Hossain 1 ,

- Gurpreet S. Lamba 1 ,

- Harry Dounis 1 ,

- Michael Levitt 1 &

- Arif Asif 1

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 13 , Article number: 281 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

2057 Accesses

2 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Renal involvement in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome is uncommon. The mechanism of kidney damage can be explained as occurring via two distinct pathways: (1) thromboembolic ischemic changes secondary to endocardial disruption mediated by eosinophilic cytotoxicity to the myocardium and (2) direct eosinophilic cytotoxic effect to the kidney.

Case presentation

We present a case of a 63-year-old Caucasian man who presented to our hospital with 2 weeks of progressively generalized weakness. He was diagnosed with idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with multiorgan involvement and acute kidney injury with biopsy-proven thrombotic microangiopathy. Full remission was achieved after 8 weeks of corticosteroid therapy.

Further studies are needed to investigate if age and absence of frank thrombocytopenia can serve as a prognostic feature of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome, as seen in this case.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is characterized by an absolute eosinophil count greater than 1500 cells/mm 3 observed at least twice with a minimum interval of 4 weeks, multiorgan involvement, and presence of tissue damage without an identifiable underlying cause [ 1 ]. Renal involvement in HES varies from 7% to 36%; however, kidney injury mediated by thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is rare [ 2 ]. To the best of our knowledge, only two cases of idiopathic HES [ 3 ] and one case of myeloproliferative-variant HES [ 4 ] have been reported. None of the reported cases achieved normal kidney function after treatment. The pathophysiology of renal impairment in HES can be explained by two mechanisms: (1) an ischemic kidney injury secondary to cardiac mural thrombus mediated by eosinophilic cytotoxicity to the heart (endocardium and myocardium) and (2) direct eosinophilic cytotoxic effect to the kidney [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. We present a rare case of idiopathic HES with multiorgan failure and renal biopsy-proven TMA in which complete remission was achieved after 8 weeks of steroid therapy.

A 63-year-old Caucasian man presented to our hospital with 2 weeks of progressive generalized weakness, vague abdominal discomfort, and dyspnea on exertion requiring more frequent use of his inhaler. He did not report similar symptoms in the past, and he denied any associated chest pain, cough, changes in bowel habits, fevers, chills, weight loss, recent travel, tick bites, or sick contacts. His past medical history was relevant for chronic bronchitis diagnosed 10 years ago. He was a former one-pack-per-day smoker for 20 years. His family history was noncontributory.

Clinical findings

The patient’s vital signs at presentation showed a blood pressure of 128/84 mmHg, heart rate of 75 beats/minute, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/minute, oxygen saturation of 99% on room air, and body temperature of 97.7 °F. On physical examination, the patient was in no apparent distress and was awake, alert, and oriented to person, place, and time. His heart and lung examination revealed sinus tachycardia and diffuse expiratory wheezes throughout the lung fields. The patient’s abdominal examination was pertinent for a nonperitonitic tenderness to palpation in the left upper quadrant. His neurological examination was remarkable for weakness in the right upper extremity. His laboratory data are summarized in Table 1 .

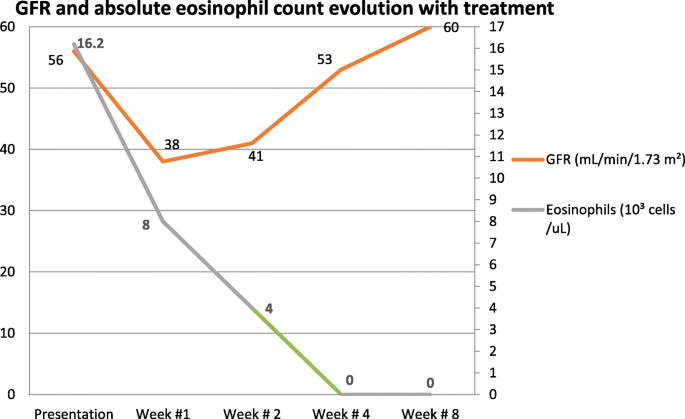

See Fig. 1 for the timeline of the patient’s kidney function and absolute eosinophil count while receiving steroid treatment.

Kidney function and absolute eosinophil count evolution on steroid treatment. GFR Glomerular Filtration Rate

Diagnostic assessment

Findings of computed tomography (CT) of the patient’s brain were unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his brain revealed subacute infarcts involving the left frontal white matter and left cerebellum; in addition, an evolving subacute infarct was seen in the left corona radiata. CT of the chest demonstrated diffuse ground-glass opacity, and CT of the abdomen was remarkable for a wedge-shaped area of low attenuation in the spleen consistent with splenic infarct. His transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a mural apical thrombus in the left ventricular (LV) apex with reduced ejection fraction (31–35%). Cardiac MRI performed 7 days after anticoagulation therapy was initiated showed a diffuse subendocardial scarring of the middle to apical LV segments and the right ventricular side of the septum. It also revealed evidence of edema of the middle anteroseptum and apical septum, consistent with endomyocardial fibrosis. However, no mural thrombus was visualized.

A presumptive diagnosis of HES was made on the basis of presenting symptoms, laboratory data, and imaging studies. Investigation for secondary causes, including immunological testing (Table 2 ), blood and urine cultures, ova and parasites, and infectious serology (Table 3 ), were unrevealing, and results of urine drug screening were negative. Bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a normocellular bone marrow population with eosinophilia comprising 60–70%, without evidence of lymphoproliferative disorder or metastatic neoplasm. Cytogenetic analysis was unrevealing: negative for breakpoint cluster region-Abelson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1 ( BCR-ABL1 ) fusion, eosinophilia-associated platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha ( PDGFRA ), platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta ( PDGFRB ), fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 ( FGFR1 ), Janus kinase 2 ( JAK2 ) mutation, and JAK2 pericentriolar material 1 ( PCM1 ) fusion.

Due to the stigma of hemolysis (normocytic acute anemia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase and bilirubin, positive schistocytes with relative thrombocytopenia), further investigation was pursued. The result of the Coombs test (direct and indirect) was negative. A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 motif 13 (ADAMTS13) activity level was greater than 50%, and the expression of complement regulatory proteins CD59 and CD55 on erythrocytes was within normal limits as determined by flow cytometry.

Due to a further decline in the estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) early in the patient’s hospital course, a kidney biopsy was pursued. Renal biopsy revealed a glomerular and vascular TMA, interstitial fibrosis, and inflammation with focal eosinophils (Fig. 1 ). IHC staining for eosinophil granule major basic protein 1 (MBP1) was not performed.

Therapeutic intervention

Our patient was started on prednisone 1 mg/kg daily and a heparin protocol at 18 U/kg/hour with an activated partial thromboplastin time goal of 60–100 seconds. Simultaneously, warfarin was initiated. Once the patient’s international normalized ratio was within therapeutic range (2.0–3.0), he was anticoagulated with heparin and warfarin for an additional 48 hours. His eosinophil count and estimated GFR were monitored on an outpatient basis, and his prednisone dose was gradually tapered. After the eighth week, the patient was maintained on 5 mg of prednisone daily.

Follow-up and outcomes

By the time the renal biopsy report was available, the patient’s kidney function had started to recover; hence, no further intervention was required. After initiation of treatment with steroids, the patient achieved resolution of pulmonary, cardiac, neurologic, and abdominal symptoms. Repeat echocardiography after 5 weeks showed improvement of LV ejection fraction to 50–55%. Complete normalization of eosinophil count and renal function was observed after 4 and 8 weeks of therapy, respectively (Fig. 1 ). At his 10-week follow-up, the patient continued to do well under close surveillance for renal and cardiac complications. At 12-month follow-up, he continued to have a normal eosinophil count and renal function. However, cardiac MRI showed persistent endocardial fibrosis.

HES is an uncommon disorder, marked by overproduction of eosinophils, eosinophilia greater than 1500/mm 3 , tissue infiltration, and organ damage. Idiopathic HES requires exclusion of primary and secondary causes of hypereosinophilia as well as lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilia [ 1 ]. For the period from 2001 to 2005, the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program reported an age-adjusted incidence of 0.036 per 100,000 person-years for myeloproliferative HES. The incidence of idiopathic HES remains obscure [ 6 ]. The most common presenting symptoms are weakness, fatigue, cough, and dyspnea, followed by fever, rash, rhinitis, and in rare cases angioedema [ 7 ]. The mortality of HES is close to 10%, with the leading cause of death attributed to cardiac events followed by thromboembolic phenomena [ 8 ].

The pathogenesis of HES is mediated by “piecemeal degranulation” or eosinophil activation and secretion of the granule cationic proteins (such as eosinophil peroxidase, eosinophil cationic protein, eosinophil - derived neurotoxin, and MBP1) and eosinophil-expressed cytokines (such as RANTES [regulated on activation, normal T expressed and secreted] and interleukin [ 4 , 9 ]). Eosinophil granule cationic proteins have the capability to activate inflammatory cells such as mast cells to induce inflammatory mediators and direct tissue-damaging cytotoxicity. These multiple proinflammatory activities lead to endothelial damage, thrombosis by activation of complement and coagulation cascade, and direct platelet stimulation and downregulation of thrombomodulin by MBP1 [ 5 , 9 ].

Renal involvement in idiopathic HES is a rare entity, with only a handful of cases reported in the medical literature (Table 4 ) [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. TMA is a life-threatening syndrome of systemic microvascular occlusions and is characterized by sudden or gradual onset of thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and renal or other end-organ damage [ 22 ]. It has been associated with diverse diseases and syndromes, such as systemic infections, cancer, pregnancy complications (for example, preeclampsia, eclampsia, HELLP [hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count] syndrome), autoimmune disorders (for example, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, antiphospholipid syndrome), hematopoietic stem cell or organ transplant, severe hypertension, and cocaine-induced [ 22 , 23 ]. Liapis et al. first reported two cases of TMA associated with idiopathic HES, along with a third case of myeloproliferative variant of HES in association with TMA [ 3 ] (Table 5 ). Of the cases described by Liapis et al ., none had full renal recovery. In contrast, our patient did remarkably well with steroid and anticoagulation therapy. After discharge, his eosinophil count remained stable with resolution of renal injury with prednisone.

The mechanism of kidney damage in TMA with HES can occur via two different pathways: (1) direct eosinophilic cytotoxic effects to the renal vasculature and (2) ischemia secondary to thromboembolic events due to endocardial disruption. Subsequently, endothelial damage and complement cascade activation will result in TMA [ 1 , 2 , 5 ]. Similarly to our patient’s case and cases reported previously, Spry [ 10 ] reported that one of every five patients with HES developed hypertension and some degree of proteinuria. However, the described patients presented late in the course of HES and most likely had ischemic changes to the kidney secondary to cardioembolism rather than intrinsic eosinophilic cytotoxicity [ 2 ].

A multicenter analysis demonstrated that steroids alone induced partial or complete response at 4 weeks of treatment in 85% of the patients [ 24 ]. It was also observed that patients with positive factor interacting with PAPOLA [poly(A) polymerase alpha] and CPSF1 (cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor) ( FIP1L1 )– PDGFRA gene fusion had a higher response to imatinib than those without [ 24 ]. It has been hypothesized that the deletion of genetic material as occurs in HES may result in gain of fusion proteins [ 25 ].

We report the only patient treated solely with a steroid, and a complete resolution of acute kidney injury was achieved, in contrast to previously reported cases. We hypothesize that factors such as the patient’s age group, proteinuria, and relative thrombocytopenia might be important to consider as prognostic factors.

TMA of the kidney in association with idiopathic HES is rare. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of HES with multiorgan involvement that was successfully treated with a corticosteroid alone. Further studies are needed to investigate if age, absence of frank thrombocytopenia, and proteinuria can serve as prognostic features, as seen in our patient’s case.

Gotlib J. World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2017;92(11):1243–59.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Shehwaro N, Langlois AL, Gueutin V, Izzedine H. Renal involvement in idiopathic hypereosinophic syndrome. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6(3):272–6.

Liapis H, Ho AK, Graeme DB, Gleich MG. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with the hypereosinophilic syndrome. Kidney Int. 2005;67(5):1806–11.

Article Google Scholar

Langlois AL, Shehwaro N, Rondet C, Benbrik Y, Maloum K, Gueutin V, Rouvier P, Izzedine H. Renal thrombotic microangiopathy and FIP1L1/PDGFRα-associated myeloproliferative variant of hypereosinophilic syndrome. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6(4):418–20.

Ackerman SJ, Bochner BS. Mechanisms of eosinophilia in the pathogenesis of hypereosinophilic disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2007;27(3):357–75.

Crane MM, Chang CM, Kobayashi MG. Incidence of myeloproliferative hypereosinophilic syndrome in the Unites States and an estimate of all hypereosinophilic syndrome incidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:179–81.

Weller PF, Bubley GJ. The idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Am Soc Hematol Blood. 1994;83:2759–79.

CAS Google Scholar

Podjasek JC, Butterfield JH. Mortality in hypereosinophilic syndrome: 19 years of experience at Mayo Clinic with a review of the literature. Leuk Res. 2013;37(4):392–5.

Thomas LL, Page SM. Inflammatory cell activation by eosinophil granule proteins. Chem Immunol. 2000;76:99–117.

Spry CJ. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: clinical features, laboratory findings and treatment. Allergy. 1982;37:539–51.

Shah TH, Koul AN, Shah S, Khan UH, Koul PA, Sofi FA, Mufti S, Jan RA. Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome presenting as IgA Nephropathy with nephrotic range proteinuria. Open J Nephrol. 2013;3(2):101–3.

Bulucu F, Can C, Inal V, Baykal Y, Erikçi S. Renal involvement in a patient with idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Clin Nephrol. 2002;57(2):171–3.

Richardson P, Dickinson G, Nash S, Hoffman L, Steingart R, Germain M. Crescentic glomerulonephritis and eosinophilic interstitial infiltrates in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71(833):175–8.

Choi YJ, Lee JD, Yang KI, et al. Immunotactoid glomerulopathy associated with idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Am J Nephrol. 1998;18:337–43.

Motellon JL, Bernis, Garcia-Sanchez A, Gruss E, Tarver JA. Renal involvement in the hypereosinophilic syndrome: case report. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:401–3.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Navarro I, Torras J, Goma M, Cruzado JM, Grinyó JM. Renal involvement as the first manifestation of hypereosinophilic syndrome: a case report. NDT Plus. 2009;2(5):379–81.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Smith A, Fernando SL. Renal infarction in hypereosinophilic syndrome. Intern Med J. 2012;42:1162–3.

Garella G, Marra L. Hypereosinophilic syndrome and renal insufficiency [in Italian]. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1990;42:135–6.

Ohguchi H, Sugawara T, Harigae H. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura complicated with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Inter Med. 2009;48:1687–90.

Hirszel P, Cashell AW, Whelan TV, et al. Urinary Charcot-Leyden crystals in the hypereosinophilic syndrome with acute renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1988;12:319–22.

Frigui M, Hmida MB, Jallouli M, et al. Membranous glomerulopathy associated with idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21:320–2.

PubMed Google Scholar

Asif A, Ali Nayer A, Haas CS. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in the setting of complement-amplifying conditions: case reports and a review of the evidence for treatment with eculizumab. J Nephrol. 2017;30(3):347–62.

Dejman A, Alavi SN, Thomas DB, Stefanovic A, Asif A, Nayer A. The potential role of complements in cocaine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy. Clin Kidney J. 2018;11(1):26–8.

Ogbogu PU, Bochner BS, Butterfield JH, Gleich GJ, Huss-Marp J, Kahn JE, Leiferman KM, Nutman TB, Pfab F, Ring J, Rothenberg ME, Roufosse F, Sajous MH, Sheikh J, Simon D, Simon HU, Stein ML, Wardlaw A, Weller PF, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective analysis of clinical characteristics and response to therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6):1319–25.

Cools J, DeAngelo DJ, Gotlib J, Stover EH, Legare RD, Cortes J, Kutok J, Clark J, Galinsky I, Griffin JD, Cross NC, Tefferi A, Malone J, Alam R, Schrier SL, Schmid J, Rose M, Vandenberghe P, Verhoef G, Boogaerts M, Wlodarska I, Kantarjian H, Marynen P, Coutre SE, Stone R, Gilliland DG. A tyrosine kinase created by fusion of the PDGFRA and FIP1L1 genes as a therapeutic target of imatinib in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(13):1201–14.

Download references

Patient perspective

Our patient has experienced a progressive recovery and is in good spirits.

This project was not supported by any grant or funding agency.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, Internal Medicine Residency Program, Jersey Shore University Medical Center, Hackensack Meridian Health, Neptune, NJ, 07753, USA

Diana Curras-Martin, Swapnil Patel, Huzaif Qaisar, Sushil K. Mehandru, Avais Masud, Mohammad A. Hossain, Gurpreet S. Lamba, Harry Dounis, Michael Levitt & Arif Asif

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

DCM, SP, and HQ developed the idea for the report and wrote the manuscript with input from all the other authors. The manuscript was revised by all the authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Diana Curras-Martin .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Curras-Martin, D., Patel, S., Qaisar, H. et al. Acute kidney injury secondary to thrombotic microangiopathy associated with idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 13 , 281 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2187-4

Download citation

Received : 05 December 2018

Accepted : 04 July 2019

Published : 05 September 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2187-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome

- Eosinophilic cytotoxicity

- Thrombotic microangiopathy

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Advertisement

Eosinophilic cystitis mimicking bladder cancer—considerations on the management based upon a case report and a review of the literature

- Original Article

- Published: 12 February 2021

- Volume 479 , pages 523–527, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Bernd J. Schmitz-Dräger ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4004-1857 1 , 2 ,

- Andreas Skutetzki 3 ,

- Ralf J. Rieker 4 , 5 ,

- Siegfried A. Schwab 6 ,

- Robert Stöhr 5 ,

- Ekkehardt Bismarck 1 ,

- Orlin Savov 1 ,

- Thomas Ebert 1 ,

- Natalya Benderska-Söder 1 &

- Arndt Hartmann 5

614 Accesses

7 Citations

Explore all metrics

The hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a rare disorder characterized by hypereosinophilia and infiltration of various organs with eosinophils. Eosinophilic cystitis (EC), mimicking bladder cancer clinically but also in ultrasound and in radiographic imaging, is one potential manifestation of the HES occurring in adults as well as in children. This case report describes the course of disease in a 57-year-old male presenting with severe gait disorders and symptoms of a low compliance bladder caused by a large retropubic tumor. After extensive urine and serologic examination and histologic confirmation of EC the patient was subjected to medical treatment with cetirizine and prednisolone for 5 weeks. While gait disorders rapidly resolved, micturition normalized only 10 months after initiation of therapy. Based upon this course the authors recommend patience and reluctance concerning radical surgical intervention in EC.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The clinical and imaging features of eosinophilic cystitis in children: a case series study

Yanan Chen, Min Ji, … Zhiming Yang

Eosinophilic cystitis: a case report of a pseudotumoral lesion

Mirco Cleva, Bruschi Ennio, … Valentino Massimo

Chronic Eosinophilic Cystitis: Up to Date Evidence Review

Omar M. Alabed Allat, Mohamed N. Alnoomani, … Amr M. Emara

Brown EW (1960) Eosinophilic granuloma of the bladder. J Urol 83:665–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(17)65773-2

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

van den Ouden D (2000) Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic cystitis: a pooled analysis of 135 cases. Eur Urol 37:386–394

Article Google Scholar

Sparks S, Kaplan A, DeCambre M, Kaplan G, Holmes N (2013) Eosinophilic cystitis in the pediatric population: a case series and review of the literature. J Pediatr Urol 9(6 Pt A):738–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.11.004

Choi MY, Tsigelny IF, Boichard A, Skjevik ÅA, Shabaik A, Kurzrock R (2017) BRAF mutation as a novel driver of eosinophilic cystitis. Cancer Biol Ther 18(9):655–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384047.2017.1360449

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zaman SR, Vermeulen TL, Parry J (2013) Eosinophilic cystitis: treatment with intravesical steroids and oral antihistamines. BMJ Case Rep 2013:bcr2013009327. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-009327

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhou AG, Amin A, Yates JK, Diamond DA, Tyminski MM, Badway JA, Ellsworth PI, Aidlen JT, Owens CL (2017) Mass forming eosinophilic cystitis in pediatric patients. Urology. 101:139–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2016.11.002

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wong-You-Cheong JJ, Woodward PJ, Manning MA, Davis CJ (2006) From the archives of the AFIP: inflammatory and nonneoplastic bladder masses: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 26(6):1847–1868

Duong DT, Goodman HS (2019) Eosinophilic cystitis caused by Candida glabrata: a case report. Urol Case Rep 26:100970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eucr.2019.100970

Hidoussi A, Slama A, Jaidane M, Zakhama W, Youssef A, Ben Sorba N, Mosbah AF (2007) Eosinophilic cystitis induced by bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) intravesical instillation. Urology 70:591.e9–591.10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.032

Caso J, Qin D, Sexton WJ (2010) Eosinophilic cystitis following immediate post-resection intravesical instillation of mitomycin-C. Can J Urol 17:5223–5225

PubMed Google Scholar

Itano NM, Malek RS (2001) Eosinophilic cystitis in adults. J Urol 165:805–807

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ackerman SJ, Bochner BS (2007) Mechanisms of eosinophilia in the pathogenesis of hypereosinophilic disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am 27:357–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2007.07.004

Hwang EC, Kwon DD, Kim CJ, Kang TW, Park K, Ryu SB, Ma JS (2006) Eosinophilic cystitis causing spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder in a child. Int J Urol 13:449–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01320.x

Download references

Acknowledgements

Technical assistance of Mrs. T. Sander is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

St. Theresienkrankenhaus, Nürnberg, Urologie 24, Nuremberg, Germany

Bernd J. Schmitz-Dräger, Ekkehardt Bismarck, Orlin Savov, Thomas Ebert & Natalya Benderska-Söder

Department of Urology and Pediatric Urology, Friedrich-Alexander University, Erlangen, Germany

Bernd J. Schmitz-Dräger

Department of Trauma Surgery and Orthopedic Surgery, Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, University Hospital Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany

Andreas Skutetzki

Department of Pathology, St. Theresienkrankenhaus, Nuremberg, Germany

Ralf J. Rieker

Institute of Pathology, Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, University Hospital Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany

Ralf J. Rieker, Robert Stöhr & Arndt Hartmann

Radiologis, Dr. Meer und Kollegen, Oberasbach-Nuremberg, Zirndorf, Germany

Siegfried A. Schwab

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Bernd J. Schmitz-Dräger: concept, literature review, manuscript drafting; Andreas Skutetzki: literature review, manuscript drafting; Ralf J. Rieker: pathology studies, manuscript drafting; Siegfried A. Schwab: radiology studies, manuscript drafting; Robert Stöhr: molecular analysis, manuscript drafting; Ekkehardt Bismarck: data retrieval, manuscript drafting; Orlin Savov: manuscript drafting; Thomas Ebert: manuscript drafting; Natalya Benderska-Söder: data retrieval, literature review, manuscript drafting; Arndt Hartmann: manuscript drafting

Ethics declarations

The authors declare compliance with acknowledged ethical standards and good clinical practice (GCP). As this is a retrospective case report without disclosing patient-identifiable information and no protocol-based interventions, IRB approval was not requested.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Schmitz-Dräger, B.J., Skutetzki, A., Rieker, R.J. et al. Eosinophilic cystitis mimicking bladder cancer—considerations on the management based upon a case report and a review of the literature. Virchows Arch 479 , 523–527 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-021-03049-x

Download citation

Received : 12 January 2021

Revised : 25 January 2021

Accepted : 28 January 2021

Published : 12 February 2021

Issue Date : September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-021-03049-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Inflammatory pseudotumor

- Bladder tumor

- Eosinophilic cystitis

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome presenting as capsular warning syndrome: A case report and literature review

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Neurology and Institute of Neurology, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

- PMID: 37682184

- PMCID: PMC10489470

- DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000034682

Rationale: Few reports of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome exist presenting as ischemic cerebrovascular disease, and the majority are watershed infarction. We report the first case of idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome that has clinical features of capsular warning syndrome lasting 6 weeks.

Patient concerns: A 26-year-old man complained of recurrent right limb weakness, accompanying slurred speech, and right facial paresthesia.

Diagnoses: The patient was diagnosed with idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (IHES).

Interventions: Adequate glucocorticoid and anticoagulant treatments were given.

Outcomes: The patient's motor ability improved, and he was discharged 2 weeks later. Muscle strength in the right-side extremities had fully recovered at a 3-month follow-up after discharge.

Lessons: This case suggests that idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome should be considered as a cause of capsular warning syndrome, and the dose of glucocorticoid and the efficacy evaluation index needs to be reevaluated for the treatment of ischemic cerebrovascular disease associated with idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Copyright © 2023 the Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Publication types

- Case Reports

- Anticoagulants

- Body Fluids*

- Cerebrovascular Disorders*

- Glucocorticoids / therapeutic use

- Hypereosinophilic Syndrome* / complications

- Hypereosinophilic Syndrome* / diagnosis

- Hypereosinophilic Syndrome* / drug therapy

- Glucocorticoids

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- World J Gastrointest Surg

- v.15(7); 2023 Jul 27

- PMC10405125

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome with hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome: A case report and literature review

Department of Gastroenterology, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, College of Medicine Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China

Bing-Hong Wang

Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery and Minimally Invasive Surgery, Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital, Hangzhou Medical College, Hangzhou 310014, Zhejiang Province, China

Yang-Jie Guo

Yu-ning zhang, xiao-li chen, yan-fei fang, wen-hao guo.

Department of Pathology, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, College of Medicine Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China

Zhen-Zhen Wen

Department of Gastroenterology, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, College of Medicine Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China. nc.ude.ujz@9105133

Supported by the National Science of Foundation Committee of Zhejiang Province, No. LY22H160003 ; and the Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science Foundation; No. 2021441200 and No. 2021RC083.

Corresponding author: Zhen-Zhen Wen, PhD, Associate Chief Physician, Department of Gastroenterology, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, College of Medicine Zhejiang University, No. 3 East Qingchun Road, Hangzhou 310016, Zhejiang Province, China. nc.ude.ujz@9105133

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is classified as primary, secondary or idiopathic. Idiopathic HES (IHES) has a variable clinical presentation and may involve multiple organs causing severe damage. Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HSOS) is characterized by damage to the endothelial cells of the hepatic sinusoids of the hepatic venules, with occlusion of the hepatic venules, and hepatocyte necrosis. We report a case of IHES with HSOS of uncertain etiology.

CASE SUMMARY

A 70-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital with pruritus and a rash on the extremities for > 5 mo. He had previously undergone antiallergic treatment and herbal therapy in the local hospital, but the symptoms recurred. Relevant examinations were completed after admission. Bone marrow aspiration biopsy showed a significantly higher percentage of eosinophils (23%) with approximately normal morphology. Ultrasound-guided hepatic aspiration biopsy indicated HSOS. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the upper abdomen showed hepatic venule congestion with hydrothorax and ascites. The patient was initially diagnosed with IHES and hepatic venule occlusion. Prednisone, low molecular weight heparin and ursodeoxycholic acid were given for treatment, followed by discontinuation of low molecular weight heparin due to ecchymosis. Routine blood tests, biochemical tests, and imaging such as enhanced CT of the upper abdomen and pelvis were reviewed regularly.

Hypereosinophilia may play a facilitating role in the occurrence and development of HSOS.

Core Tip: Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (IHES) is characterized by a continuous increase and abnormal accumulation of eosinophils in the peripheral blood. Its clinical manifestations vary, and may involve multiple organs and cause serious damage. Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HSOS) can lead to veno-occlusion and hepatocyte necrosis. We report a case of IHES with HSOS. However, the cause of HSOS was unknown, and we could not determine whether it was caused by herbal medicine or IHES. Prednisone, low molecular weight heparin and ursodeoxycholic acid were given. Hypereosinophilia may play a facilitating role in the occurrence and development of HSOS.

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome (IHES) is characterized by a continuous increase and abnormal accumulation of eosinophils in the peripheral blood[ 1 ]. Its clinical manifestations vary from asymptomatic eosinophilia to severe multi-tissue injury and even terminal organ failure, including damage to lungs, heart, digestive tract, skin, and peripheral or central nervous system[ 1 , 2 ].

Hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (HSOS), namely, hepatic veno-occlusive disease (HVOD), is characterized by injury of the sinusoidal endothelial cells of hepatic venules, which leads to occlusion of venules and necrosis of hepatocytes. Its clinical manifestations are weight gain with or without ascites, hepatogenic right upper abdominal pain, hepatomegaly and jaundice[ 3 ].

Other complications of hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) have been reported previously, including HSOS, but in that case, HES was considered to be involved in the occurrence and development of HSOS[ 4 , 5 ]. Here, we report a case of IHES with unknown etiology of hepatic venule occlusion and review previous literature in PubMed.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints.

A 70-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital with itchy skin on his extremities for > 5 mo.

History of present illness

Five months before admission, without obvious inducement, the patient showed pruritus and red patches on the palms of both hands and soles of both feet. The patches protruded from the skin. He had no history of insect bites, no food or drug allergies, and no abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. The patient paid no attention to these symptoms. The itching and rash did not subside for 3 mo and he attended the local hospital for treatment. A diagnosis of urticaria was made, and he was given antiallergic treatment with clavulvoxel gel but the details are unknown; after which, the itching symptoms improved. However, during this period, itching on the palms of both hands and soles of both feet occurred repeatedly, and spread to the limbs and face. The nature of the skin rash on the limbs was the same as before, and his face showed extensive redness and swelling, without itching and discomfort. One month before admission, he attended the local hospital for treatment in the Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The ingredients of this treatment were frankincense, Rehmannia glutinosa , Akebia quinata , Paeonia albiflora pall, licorice, Prunella vulgaris , chrysanthemum, Divaricate saposhnikovia , gentian, poria, myrrh, Angelica sinensis , Sophora flavescens , dandelion and Angelica dahurica . After > 1 wk of treatment, the rash dissipated, but there was still itching and discomfort in both hands and feet. Three days before admission, he attended Shaoxing People’s Hospital for treatment. Cetirizine and ebastine were given for antiallergic treatment. The patient then went to the Department of Gastroenterology Outpatient of Run Run Shaw Hospital affiliated to Zhejiang University Medical College for further treatment and was proposed to be admitted to the hospital due to eosinophilia.

History of past illness

The patient was previously healthy and generally in good condition.

Personal and family history

The patient denied any family genetic history.

Physical examination

The patient’s vital signs were stable and his spirit was good. The skin and sclera were yellow, and asthma, fever and gastrointestinal symptoms were absent. Urine and stools were normal. The palms of both hands and the soles of both feet had red patches protruding from the skin. There was no enlargement of superficial lymph nodes throughout the body. Pulmonary and cardiac examinations did not show any significant abnormalities. The abdomen was flat and soft without tenderness or rebound pain. There was no percussion pain in the liver area, and the liver and spleen were not felt under the ribs. Murphy sign and mobile dullness were negative, and bowel sounds were 4 times/min. Edema in the lower extremities was not observed and pathological signs were not elicited.

Laboratory examinations

Auxiliary examination of the hematological system after admission found that the platelet count was 75 × 10 9 /L (normal range, 125–350 × 10 9 /L), percentage of neutrophils was 31.4% (normal range, 40.0%–75.0%), percentage of eosinophils was 34.4% (normal range, 0.4%–8.0%), absolute number of eosinophils was 2.47 × 10 9 /L (normal range, 0.02–0.52 × 10 9 /L), eosinophil count was 2800.0/μL (normal range, 50.0–300.0/μL), and red blood cell count, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, and absolute number of lymphocytes were all within the normal range. Coagulation function tests showed that prothrombin time (PT) was 15.5 s (normal range, 11.5–14.5 s), PT% was 71.0% (normal range, 80.0%–120.0%), PT control was 13.0 s, international normalized ratio was 1.25 (normal range, 0.90–1.10) and D-dimer was 0.86 μg/mL (normal range, 0.0–0.50 μg/mL).

Blood and stools from the digestive system were negative for protozoa, fecal egg accumulation, parasites and fungi. Serum tumor marker tests revealed increased levels of carbohydrate antigen (CA)125 [743.30 U/mL (< 35.0 U/mL)] and ferritin [626.0 μg/L (30.0–400.0 μg/L)], but CA19-9, alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and total prostate-specific antigen were within normal limits. Blood biochemistry showed that alanine transaminase (59 U/L), aspartate transaminase (60 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (445 U/L), glutamyl transpeptidase (931 U/L), total bilirubin (31.5 μmol/L), direct bilirubin (20.6 μmol/L), total bile acid (21.28 μmol/L), and C-reactive protein (12.7 mg/L) were elevated, while albumin (35.1 g/L), albumin and globulin ratio (1.12), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (0.75 mmol/L), β-hydroxybutyric acid (0.01 mmol/L), retinol binding protein (24 mg/L) and cholinesterase (2951 U/L) were decreased. Lactate dehydrogenase was within the normal range.

Among the laboratory examination indicators targeting the rheumatic immune system, levels of IgG (17.50 g/L) and IgE (266.0 IU/mL) were increased. IgA, IgM, complement components C3 and C4, rheumatoid factor, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, IgG4, and antinuclear antibody profiles were normal.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antibody (12.55 IU/L) and HBV core antibody (4.68 S/CO) were increased, while HBV e antibody (0.99S/CO) was decreased. Antibodies against hepatitis C virus (HCV), Treponema pallidum and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative. Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen-IgG was high (616.0) while IgM was negative. Tuberculosis-infected T cells were unreactive and Mycobacterium tuberculosis -specific antigen pore was 0. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgG antibody was high (> 250.0) while CMV IgM antibody was negative.

Imaging examinations

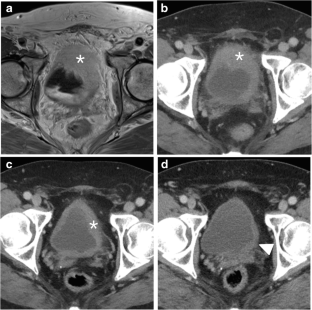

Gastroduodenoscopy showed chronic superficial atrophic gastritis with erosion, predominantly in the gastric sinus and gastric horn and body, and ulceration in the duodenal bulb, with pathology suggesting chronic inflammation of the stomach and duodenum (Figure (Figure1A 1A and andB). B ). No significant abnormalities were seen on colonoscopy, and pathology reported chronic inflammation of the mucosa of the terminal ileum, ileocecal region, ascending colon and rectum (Figure (Figure1C 1C and andD). D ). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the upper abdomen suggested hepatic venule congestion with hydrothorax and ascites (Figure (Figure2A 2A and andB). B ). Chest CT showed nodules beside the right oblique fissure, a few infectious lesions in the left upper lobe, and paraseptal emphysema in both upper lungs. There was a small amount of pleural effusion on both sides accompanied by pulmonary tissue distension, and inflammatory fibrous lesions scattered in both lungs. The apical pleura of the lungs was thickened. Cardiac ultrasound suggested mild aortic regurgitation.

Gastrointestinal endoscopy and pathology. A: Gastroduodenoscopy revealed an ulcerated scar on the duodenal bulb; B: Pathology of the intestinal mucosa of the duodenal bulb showed chronic inflammation with localized erosion (magnification, 10 ×); C: Painless colonoscopy showed no significant abnormalities in the mucosa of the terminal ileum; D: Pathology of the mucosa of the terminal ileum showed chronic inflammation (magnification 10 ×).

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography images of the upper abdomen of the patient. A and B: Pretreatment enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed edema around the portal branch and fine compressed flattening of the inferior hepatic segment and hepatic veins with ascites; C and D: Post-treatment enhanced CT showed that the inferior vena cava and hepatic veins of the hepatic segment were thin, and congestion of the hepatic venules was improved.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Pathological findings on ultrasound-guided liver puncture biopsy supported the diagnosis of HSOS. Lamellar hepatic sinusoidal dilatation and congestion with loss of hepatocytes and a residual reticulofibrous stent were seen (Figure (Figure3A 3A and andB). B ). Bone marrow biopsy revealed active proliferation of bone marrow tissue but a significantly higher percentage of eosinophils (23%) with approximately normal morphology (Figure (Figure3C 3C and andD). D ). PDGFR gene rearrangement and BCR / ABL fusion gene were negative. Combined with the above laboratory test indicators, imaging examinations and pathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with IHES and hepatic venule occlusion, after excluding tumors of the hematological and digestive systems, parasite, fungus and other infections causing eosinophilia, hereditary metabolic liver diseases such as alcoholic liver disease and Wilson’s disease, connective tissue diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and IgG4-related diseases, and infections with hepatitis A virus, HBV, HCV, HDV, HEV, HIV, T. pallidum , Epstein–Barr virus, tuberculosis, and CMV.

Pathology of liver and bone puncture of the patient. A and B: Ultrasound-guided liver puncture biopsy suggested hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. Hepatic lobular structures, hydropic degeneration of hepatocytes, dilated and stagnant lamellar hepatic sinusoids with loss of hepatocytes, residual reticulofibrous scaffolds and insignificant inflammatory cell infiltration were seen (A: magnification 10 ×; B: magnification 40 ×); C and D: Bone marrow aspiration biopsy showed an active proliferation of bone marrow tissue but a significantly higher percentage of eosinophils (23%) with approximately normal morphology (C: magnification 10 ×; D: magnification 40 ×).

On the tenth day after admission, the patient was treated with prednisone 25 mg orally three times daily (1 mg/kg) and the absolute eosinophil count started to decrease. Subsequently, anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin 0.4 mL subcutaneously once daily was added. In addition, the patient was treated with ursodeoxycholic acid at 250 mg orally three times daily. The patient was discharged from the hospital on January 17, 2022, in good general condition with symptom improvement after treatment.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After discharge, the patient underwent regular routine blood tests, eosinophil count, liver and coagulation function tests, and contrast-enhanced CT of the upper abdomen and pelvis to adjust the drug dose (Figure (Figure2C 2C and andD). D ). On January 21, 2020, 4 d after discharge, the absolute number of eosinophils decreased to 0.01 × 10 9 /L, and the dose of prednisone was adjusted to 15 mg orally twice daily, which was reduced to 10 mg twice daily 1 mo later. On April 13, 2020, the absolute number of eosinophils increased to 0.55 × 10 9 /L, and has been in the normal range since then. The dose of prednisone was reduced to 5 mg in July 2020, and the drug was discontinued in December 2020 when the absolute number of eosinophils was normal. However, the dose was increased to 5 mg per day as the absolute eosinophil count increased to 2.21 × 10 9 /L. The dose was maintained for 1 year and then changed to 4 mg daily until now. In addition, anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin was discontinued 4 mo after discharge due to petechiae on the patient’s body. To date, under treatment with prednisone and ursodeoxycholic acid, the results of liver function tests, eosinophil count, and CT scanning have all indicated that the patient is in good condition.

HES is defined as an absolute eosinophil count in the peripheral blood > 1.5 × 10 9 /L after two examinations (interval > 1 mo) and (or) a bone marrow nucleated cell count eosinophil percentage ≥ 20% and (or) pathologically confirmed extensive tissue eosinophil infiltration, and (or) significant eosinophil granular protein deposition (in the presence or absence of obvious infiltration of eosinophils in tissues)[ 6 ]. The most important characteristic of HES is hypereosinophilia accompanied by eosinophil-mediated organ damage and (or) dysfunction, while excluding other potential causes.

HES is divided into primary, reactive or idiopathic HES. The proportion of eosinophils in the bone marrow nucleated cell count of our patient was ≥ 20%, and the absolute count of eosinophils in peripheral blood was ≥ 1.5 × 10 9 /L. PDGFR gene rearrangement and BCR / ABL fusion gene were negative, which excluded clonal HES. The patient had no previous allergic disease, parasitic infection, connective tissue disease, splenomegaly, endocardial disease or severe mucosal ulcer disease, and no increase in CD25 + atypical spindle-shaped mast cells on bone marrow aspiration. Because the patient had no inflammatory reaction, tumors of the hematological and digestive systems were excluded. The patient was diagnosed with IHES as the cause of HES was unknown.

The onset of IHES is usually insidious, with large differences in clinical manifestations and lack of specificity, which may involve damage to the lungs, heart, digestive tract, skin, or peripheral or central nervous system. Thrombosis is a more common manifestation, and it has been documented that thromboembolic complications may occur in a quarter of HES patients[ 7 ]. Some reports have pointed out that HES can cause portal or hepatic vein thrombosis or Budd–Chiari syndrome, which are summarized in Table Table1 1 [ 4 , 5 , 8 - 26 ]. This patient presented with maculopapular rash and pruritus as the first manifestations, consistent with the diversity of clinical manifestations of IHES.

Summary of cases reported regarding hypereosinophilic syndrome with sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, portal vein thrombosis, or Budd–Chiari syndrome

SOS: Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome; CT: Computed tomography; NA: Not available; IV: Intravenous injection; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori .

HSOS, also known as HVOD, is an intrahepatic postsinusoidal portal hypertension resulting from stenosis or occlusion of the central and inferior lobular veins of the liver after injury, which, as described above, leads to weight gain with or without ascites, right upper abdominal pain of hepatic origin, hepatomegaly, and jaundice[ 3 ]. The occurrence of hepatic venule occlusion is mainly associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), while chemotherapeutic agents have also been suggested to cause hepatic venule occlusion, such as inotuzumab ozogamicin[ 27 , 28 ], gemtuzumab ozogamicin[ 29 ] and other targeted drugs, as well as oxaliplatin[ 30 , 31 ]. Herbs containing pyrrolizidine alkaloid (PA) have also been reported to cause occlusion of hepatic venules, that is, PA-HSOS, such as Gynura segetum [ 32 - 34 ] and Heliotropium eichwaldii [ 35 ]. In this case, the patient presented with jaundice. Imaging showed hepatic venule congestion and ascites, and liver puncture indicated hepatic venule occlusion. However, he had not been treated with HSCT or chemotherapeutic drugs, and it cannot be excluded that the herbs he received caused the hepatic venule occlusion. It is reported that peony may cause adverse reactions in the liver[ 36 ], but there is no literature to show that these herbs taken by the patient contain PA, and there is no report indicating that these herbs are associated with hepatic venule occlusion.

In 1995, Kojima and Sasaki[ 4 ] reported a case of HES complicated by acute HSOS. The HSOS caused a series of clinical symptoms that returned to normal after the use of corticosteroids to treat HES. In addition, eosinophil granular proteins led to direct tissue damage and a local blood hypercoagulable state. It was considered that hypereosinophilia was involved in the development of hepatic venule occlusion[ 4 ]. A case of HSOS with hypereosinophilia reported by Yamaga et al [ 5 ] was relieved after treatment with prednisone and ursodeoxycholic acid[ 5 ]. In our patient, the severity of hepatic venule occlusion and changes in liver function indicators changed with the indicators of eosinophils. Although no eosinophil infiltration was found in the liver biopsy, the eosinophil and liver function indicators began to return to normal after the patient was treated with prednisone. However, when the dose of prednisone was reduced toward discontinuation, the eosinophils increased again, and the symptoms of hepatic venule occlusion were aggravated, and pelvic effusion increased. With the continued use of prednisone, these indicators returned to normal. Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that the hepatic venule occlusion was caused by IHES.

The pathogenesis of HSOS involves the injury of endothelial cells and hepatocytes in the hepatic sinusoids caused by HSCT, chemotherapeutic agents, PA, etc ., as well as locally released cytokines that also induce the activation of cell adhesion molecules on endothelial cells, leading to local cell damage and shedding[ 37 ], resulting in activation of the coagulation cascade, the formation of blood clots, and the loss of thrombus-fibrinolytic balance[ 38 ]. Not only do eosinophils cause tissue damage[ 39 , 40 ], but they can also be rapidly recruited to the site of injury for platelet adhesion to form thrombus and are activated through direct interaction with platelets. Activated eosinophils contribute to platelet activation, inhibit the function of thrombomodulin[ 41 , 42 ], and promote thrombus formation[ 43 ]. It is speculated from the pathogenesis that hypereosinophilia may lead to venous thrombosis and hepatic venule occlusion through an imbalance of the coagulation fibrinolysis balance caused by endothelial cell injury.

Prednisone is preferred for the first-line treatment of IHES, and imatinib, interferon, azathioprine, hydroxyurea, or monoclonal antibodies can be chosen as second-line therapeutic agents[ 6 ]. The present case was also treated with prednisone and the dose was reduced or restored according to the condition.

With regard to the pharmacological treatment of hepatic venule occlusion, there is no specific drug available at present, and symptomatic supportive treatment is mostly given, including liver protection, diuresis, and microcirculation improvement. High-dose hormone shock therapy may be effective for HSCT-HSOS, during which the risk of infection needs to be monitored[ 44 ], while the therapeutic effect of HSOS caused by other reasons is uncertain. In addition, anticoagulation can be administered, especially in patients in the acute/subacute phase in the presence of manifestations such as ascites and jaundice, and some studies have shown that low molecular weight heparin can play a therapeutic role[ 45 ]. Defibrotide is effective for the prevention and treatment of HSCT-HSOS[ 44 ], as well as recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin[ 46 , 47 ] and ursodeoxycholic acid[ 44 ]. However, most studies have focused on HSCT-HSOS and a small number on PA-HSOS. Therefore, the treatment modality for HSOS remains to be clarified and standardized. In this case, using the new EBMT criteria for HSOS in adults, we judged that the patient had mild HSOS based on the time since first clinical symptoms, bilirubin levels, transaminases, weight increase and renal function[ 48 ], and was treated with low molecular weight heparin combined with ursodeoxycholic acid.