Navigating Literacy Challenges, Fostering a Love of Reading

- Posted February 15, 2024

- By Jill Anderson

- Language and Literacy Development

- Learning Design and Instruction

- Teachers and Teaching

How do we teach children to love reading amidst the ongoing debates surrounding literacy curriculums and instructional methods, and the emphasis on student outcomes? It's something Senior Lecturer Pamela Mason thinks about a lot. She's been both a teacher and school leader, and has spent decades training teachers on literacy instruction. She says it takes many pieces coming together to create the perfect mix — especially making it fun — for successful reading instruction.

As data continues to show dips in children's reading assessments nationwide, some states like Florida and Mississippi have been able to make progress and capture the attention of educators.

"There's a whole systemic approach to literacy improvement. A lot of people looking at Mississippi say, 'Oh, it's because there's going to be third grade retention. Yes, that is part of their literacy plan, but there's so much more. There's in-school support. There's after school support. There's even books being given free to families who attend schools who are underperforming," she says. "So we have this merging of teachers, and community, and families, and administrators, all shining a light on the importance of literacy, and hopefully we're keeping some of the joy involved in that, as well."

JILL ANDERSON: I'm Jill Anderson. This is the Harvard EdCast. Pamela Mason knows teaching reading takes more than just a great curriculum to make an impact. She's a Harvard expert on literacy pedagogy and has spent decades not just as a teacher and leader in the classroom, but also training reading coaches and specialists.

As more districts change literacy curriculums, she says we need to focus on supports and resources and sustaining those efforts for teachers. She knows many educators are under pressure in ways that student outcomes often override the process of learning to read. Mason says a big piece of learning to read is just making it fun. I wanted to know more about how the debates around literacy and changing curriculums impact teaching reading and how educators and families can teach children to love reading.

First, I asked her about the complexities in learning to read and teaching reading.

PAMELA MASON: Every child who starts school in kindergarten, or even in pre-K, they're very excited about learning how to read because they see people in their lives reading what looked to them like squiggles, and they're making sense of them. They are laughing about them, they're sharing them, and so there's a lot of motivation to figure out how to read. For most of our languages, there is a connection between what those squiggles are, we know them as letters, into sounds, and the letters work together to make words.

So there is this code that learners need to learn, and that is what we're seeing in terms of what we call phonics, matching sounds to symbols, symbols to sounds, and putting those symbols and sounds together to come up with words, come up with sentences, paragraphs, and whole stories. So that's what's involved in learning how to read.

In terms of teaching how to read, then we need to have the teachers kind of back up and say, "All right. We're going to start with sounds and symbols and make those symbols into words." And that is what we see as the kind of phonics instruction in schools. While they're making symbols into sounds, and sounds into symbols, and learning how to read, learners need to be joyful about it. They want to have fun with words.

Even little kids, when they're just learning to talk, make up silly little rhymes because they're experimenting with language. And that same joy and feeling of experimentation should carry over, actually, into how we teach reading. I don't think any of us would continue learning how to do something if somebody kept telling us how hard it was, how important it was, how necessary it was. Yes, we know that a lot about things as adults that we do in life, but if there's no joy in it, why bother, or we're like half invested in it.

So having teachers think about how to give good instruction and engender this joy so that we have children who know how to read, enjoy reading, and so they want to read. And there's a lot of research around that cyclical positive reinforcement, of-- you do something, you get better at it, it feels good, you do it more. And we can think about that as adults, things that we've learned how to do as adults, and so what keeps us in the game. And success and joy keep us all in the game.

JILL ANDERSON: I imagine it has to be hard for literacy instructors, any kind of teacher, trying to teach kids how to read, just because it feels like there's so much pressure. It's easy for that joy, I would imagine, to just disappear.

PAMELA MASON: Yes, there has been a lot of pressure, especially coming out of the pandemic and thinking about the learning loss that may have happened. And whilst we have children for whom reading doesn't click, right, but in keeping at it, and providing them with extra support, we still need to hold out that this can be fun, this can be interesting. They may be interested in a hobby or a sport, and so bringing that in and showing how learning how to read will help them in that endeavor, or that people that they look up to are readers, so that we can always kind of keep that motivation going.

As Jeanne Chall said, "A good program in the hands of a great teacher is optimum," but we need to also get the learners thinking about their agency and their interest in reading. We see that also with children who come to us who are multilingual.

JILL ANDERSON: Right.

PAMELA MASON: They know a lot about language. They know of home language that they've learned to speak. They may have learned to read it. And then they come to our classrooms where most of the time English is the language of instruction, and so it looks a little different to them. But helping teachers see the assets that these learners bring, that they already know a language and it's just applying some of those skills to this new language, English, our language of instruction. And so I think it's important that we really think about all of those aspects of our learners and how we can help them decode the language and then understand it. That's the whole point of it.

PAMELA MASON: It's not just rattling off rhyming words, or word families, or all the words you can think of that begin with the letter B. It's around reading something that's interesting that you can understand and you want to understand.

JILL ANDERSON: We're seeing a lot of movement to change literacy curriculums around the country, and some states-- Florida, Mississippi, those have been highlighted as doing really, really well with reading. How important are literacy curriculums as a piece of this puzzle?

PAMELA MASON: The literacy curriculums are an important piece in that you want to have a good arc of learning.

JILL ANDERSON: Mm.

PAMELA MASON: You want to have good sound pedagogy as well as content. But the other thing that we see is when districts or schools decide that they need to adopt a literacy curriculum they're saying explicitly, or implicitly, there's a problem we need to solve.

PAMELA MASON: So what is that problem? And so there's some self-study that goes on. What are our learners doing well? What aren't they doing well? Is it the curriculum? Is it the teaching? And when they decide it's the curriculum, then they usually have a committee. And the International Literacy Association really describes this process where teachers and specialists come together and say, all right, what do our learners need? How do these curriculum address this need? And then when the curriculum gets adopted, usually from the publisher, you get an influx of support. They may bring consultants or specialists to do professional learning for grade levels or for whole schools, and then you have ongoing literacy coaching that help teachers get used to the new program, and implement it.

And as we see in Florida, with, "Just Read, Florida!" and in Mississippi, a lot of their progress in the National Assessment of Educational Progress has stemmed from this infusion of time, attention, and resources-- money and human resources, to help teachers do a better job. If the story of stone soup, you know-- you're adding all these different things, so you add all of these different variables which are all very important. And it's this infusion of attention, and support, and validation, and so, then you get the Mississippi miracle. You get a lot of success in Florida. You get success in Alabama. In our country, these are not states that one would look to as intellectual powerhouses, which is really unfair.

PAMELA MASON: But it is because of the National Assessment of Educational Progress. They haven't done well, but now they're doing much better, and everyone is kind of scratching their heads. Well, if you actually look at what they're doing, there's a whole systemic approach to literacy improvement. A lot of people looking at Mississippi say, oh it's because there's going to be third grade retention. Yes, that is part of their literacy plan, but there's so much more. There's in-school support. There's after school support. There's even books being given free to families who attend schools who are underperforming.

So we have this merging of teachers, and community, and families, and administrators, all shining a light on the importance of literacy, and hopefully we're keeping some of the joy involved in that, as well. And so it's really hard to tease out-- if they did this without this, would they have the same results? And in terms of being an educator, and looking at learners, you don't want to say, "All right. You get this, and you get this, and we'll see who comes out on top." I mean, I understand that's part of research design, but in terms of having been a school leader you want all of your learners to have the very best from everybody. In terms of the teachers, and the families, and the learners, we're all in it together.

JILL ANDERSON: Because I do wonder if after some of those districts and states get propped up, if other districts in other states might say, "Oh hey, we should look at our curriculum and change it, too." But then maybe they don't put all that support in, all those additional resources, to not just get through the first year but to sustain it.

PAMELA MASON: Exactly. That's important, that it's sustainable. And though Mississippi had this great increase in the NAEP, in 2019, there was a slight drop in 2022, and so you wonder whether the shine has gone off the apple, you know, whether some of the resources may have been pulled out, because it's not an inexpensive endeavor. So one again has to wonder whether everybody's getting all of this attention and so we all rise to the occasion, and then the attention wanes, and we're thinking, "Oh well. You know, let's kind of ease back in." And perhaps we're not maintaining our enthusiasm in being at the top of our game.

JILL ANDERSON: Right. One of the things about literacy that has always fascinated me is the endless debate around it even though we seem to know what works. You're someone who supports-- teaches literacy specialists, literacy coaches, what do you think is getting lost in all of these endless debates we have?

PAMELA MASON: The basic debate is, do we teach code or phonics, or do we teach meaning? And we have to teach it all.

PAMELA MASON: In our language there is a code, and to hide that code and not open that code up to our learners, it's just not right, and it's not going to come out with good results. But once we help our learners with the code, you're giving them a key, --

PAMELA MASON: --but they have to have a door to open, and that's comprehension. And so how does knowing all these words, and how to say them, open up poetry, open up narrative, open up mysteries, open up fantasy, so that oh, this is why I'm learning that "B" says "buh", because I can talk about battles, and bullets, and all kinds of horizons and things that we can think of. So it's really important to have that comprehension. So there has to be the, this is the code, this is the meaning, and we need to work it together.

JILL ANDERSON: What do you hear from the teachers, and the specialists, and the coaches, who are coming to you taking professional development, or just coming for a degree? Are they just exhausted from all this debate?

PAMELA MASON: The ones that I work with are on some level exhausted but also eager to know what should I be doing? What does work? And we try to avoid the notion of best practices versus best practicing.

We're in it and we're always learning more about how people learn to read, and how people learn to read in multiple languages. And so education is a process. Being an educator is a process. And so we're always trying to do what's best with the knowledge that we have at this time.

So they're very anxious and willing to do better, and to find out new techniques, and how do they work, and when do they work, and really becoming observers of children and kid watchers. And sometimes that one technique will work for maybe 90% of your learners, and there's that 10% that just not clicking. And so what about those learners? What about your curriculum? What about the way you're delivering your curriculum? It's always about what you teach, and also how you teach it.

You may need to tweak it a little bit just to grab those other learners and get them feeling accomplished, and seeing their growth, and them seeing their own growth. That's also very important.

JILL ANDERSON: So I want to distinguish between these two ideas. One that you had kind of mentioned earlier about finding some joy. And it seems like there is teaching kids to read, and then there's teaching children to love reading. What's the difference, and how do you implement that while adhering to the science of reading?

PAMELA MASON: Well, we know how to teach children how to read.

PAMELA MASON: And then providing them with a reading menu, a reading diet, that's varied. That we have short pieces that they read, long pieces, silly pieces, pieces that tell them why the roots go down and the stems go up, which most children want to know. They're very interested in how their world works. Giving them that variety will help them be more joyous.

The other issue is text difficulty. There is a push, and rightly so, to have our learners at an appropriate level of difficulty, at their grade level, and supporting them to do more. But I'm sorry, I'm not going to cuddle up with a physics textbook at the end of a long day.

JILL ANDERSON: Yeah. [LAUGHING]

PAMELA MASON: And so even as a skilled reader, sometimes I just want to read something lighter. Sometimes we call them our summer beach books. I enjoy actually reading young adult fiction.

It keeps me in touch with what the young adults are reading, are interested in. They're very well written, and they're fun.

I need that variety in my reading diet, and our learners need that variety in their reading diet, so that they, again, maintain that joy. That it's not always this arduous task of, "What does the author mean? What is the deep meaning?" You know, sometimes you just want to have fun with your reading.

JILL ANDERSON: So just letting them choose whatever they want, even when it's always graphic novels.

PAMELA MASON: Yes, there's nothing wrong with graphic novels. There are adult graphic novels. Octavia Butler's work is now in a graphic novel form. And actually involving a lot more parts of your brain, because the words are fewer than if it were in a text, but you're seeing visual images, you're seeing expressions. So you know how the characters are feeling, rather than being told how they're feeling, and so it is a multiple literacy. So you're reading words, you're reading visuals, you're reading how the characters are situated on the page to each other.

So there's a lot of literacies going on with graphic novels, and I have to say that I'm still developing some of those literacies, because I'm a linear reader. I like reading text, and when I see all of those images, and the bubbles, I'm not sure do I go left to right, up to down. But again, some of our learners-- just like a fish to water. They're very comfortable with that, and it's interesting to hear them talk about how they navigate that presentation of text and multiliteracies.

JILL ANDERSON: Is there one thing that you would recommend reading teachers try to do?

PAMELA MASON: Find texts that their learners want to read.

JILL ANDERSON: Is that hard, though?

PAMELA MASON: Sometimes the children don't know what they like.

JILL ANDERSON: Yeah.

PAMELA MASON: And so experimenting, and giving learners permission not to finish a book. I mean, as an adult, have you finished every book you've started? I'll tell you, quite frankly, I haven't. You know, yes, you want to give it some time to reveal the storyline, to understand the setting, and the characters, and then sometimes you can say, "Yeah, no. No thanks." And there's no shame in that. This is not the genre, or the author, or the style, or the setting, or the time period in which this text is situated, and it's OK.

If they're constantly only reading the first couple of pages and dropping it, then we need to be more--

PAMELA MASON: -- focused and really try to help the reader find something that they like, either around topic, around difficulty level, and then get them through it. I'm not trying to say that they should be grazing all the time, kind of at a literacy buffet, --

PAMELA MASON: -- but they do need to sit down and have a whole meal. But finding which type of literature, that type of reading, that type of text, is important.

JILL ANDERSON: Because I can imagine for some children, especially those who are just resistant to reading, it can be really hard to find that one type of book, or a genre, or something that they're even open to reading.

PAMELA MASON: Yes. And sometimes a book of short stories will be fine, or plays on books, so we have, "The Three Little Pigs," and then we have Jon Scieszka's story of the real-- this true story of the three little pigs where it's told from the wolf's perspective.

PAMELA MASON: And it's hysterical. It gives you an opportunity to talk about perspective-taking, and you know, do you believe the wolf, or was he really trying to cover up that he wanted to eat the pig? You can find different books that put a different spin on traditional stories or traditional points of view that may be engaging to some learners that are reluctant.

JILL ANDERSON: What about parents? We know that they play a huge role in their child's reading. As a parent you get in front of a teacher, maybe 10 minutes or 20 minutes a year, for a parent teacher conference. Is there anything that they should be asking their child's teacher about reading?

PAMELA MASON: They should ask the teacher what it is that the teacher is working on in terms of a comprehension skill. Are they working on sequencing? Are they working on knowing fact versus opinion? Are they working on character development? What is this character like? How are they changing throughout the story? And then when the parents, the families are talking with their child about what they're reading, be it for school or be it for leisure, then ask those same types of questions so that the child gets the hint that, oh what I'm learning in school, actually, I'm supposed to be applying any and every time I read. And that is important.

And it also helps open up the conversation between children and their families. What are you reading? Blah blah blah. Do you like it? Yes. End of conversation. [LAUGHING] Rather than, oh, what are you reading? Who's your favorite character? Why is that your favorite character? Would you want that character to be your friend, or not? Is that character a good person or someone that you would want to keep away from? So that kind of opens up the conversation around the storyline.

I would encourage families not to kind of get out the flashcards, and, all right, all right, we're going to do reading today. And then, all right, these are the 20 words you need to know at the snap of a finger. We'll leave that at school, and hopefully not a lot of that is happening in school. But it should be again bringing in that joy. The other aspect of reading that I encourage families to do is to read.

JILL ANDERSON: Right, read together.

PAMELA MASON: We're always telling our children, it's important to read. When do they see you reading?

JILL ANDERSON: Right. [SURPRISED LAUGHING]

PAMELA MASON: When do they see you reading and laughing out loud? When do they see you reading and, you know-- oh my god, I don't believe they just did that! So it's again, you're talking the talk-- reading is important. But you need to walk the talk. You need to do it. And there have been times in my family where I just kind of go in the living room with a book, and sit down and-- don't bother me, I'm reading. Wait, wait, wait, wait a minute. Wait, wait, wait till I get to the end of this chapter, then-- then we can talk. As long as, you know, nothing-- there's no dire emergency in the family, it can wait.

That's also important, that we don't kind of wait till the our children go to bed for us to read. And then--

JILL ANDERSON: Interesting.

PAMELA MASON: --we kind of look like, somewhat like, hypocrites. We're saying reading is important but they never see us read. Writing is important. When do they see you write?

JILL ANDERSON: Right

PAMELA MASON: It could be a book, it could be just the recipe. And talking out loud, "Oh, all right. I need to get these ingredients. All right, what needs to go first?" And that sequencing, those are all comprehension skills. And so talking out loud, thinking out loud about what you're reading, be it for pleasure, be it for information, be it procedural-- recipes are procedural. Test is in the outcome. "Maybe I didn't put this ingredient in." Or, "Maybe I should have left it in the oven. It said 10 minutes but maybe it needed 12 minutes, or 15 minutes."

And so again, that's all those decisions are based on text.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

JILL ANDERSON: OK. Well, thank you very much, Pamela.

PAMELA MASON: Well, thank you, Jill, for having me. It's been great talking about literacy with you.

JILL ANDERSON: Pamela Mason is a senior lecturer and director of the Jeanne Chall Reading Lab, at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, where she also teaches the workshop, "Culturally Responsive Literature Instruction." This is the Harvard EdCast, produced by the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Thanks for listening.

An education podcast that keeps the focus simple: what makes a difference for learners, educators, parents, and communities

Related Articles

To Weather the "Literacy Crisis," Do What Works

Virtual Running Records During the Pandemic

Phase Two: The Reach

Reach Every Reader on its impact and the project’s next phase

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Why Reading Is Important for Children’s Brain Development

Early childhood is a critical period for brain development , which is important for boosting cognition and mental well-being. Good brain health at this age is directly linked to better mental heath, cognition, and educational attainment in adolescence and adulthood. It can also provide resilience in times of stress.

But, sadly, brain development can be hampered by poverty. Studies have shown that early childhood poverty is a risk factor for lower educational attainment. It is also associated with differences in brain structure, poorer cognition, behavioral problems, and mental health symptoms.

This shows just how important it is to give all children an equal chance in life. But until sufficient measures are taken to reduce inequality and improve outcomes, our new study, published in Psychological Medicine , shows one low-cost activity that may at least counteract some of the negative effects of poverty on the brain: reading for pleasure.

Wealth and brain health

Higher family income in childhood tends to be associated with higher scores on assessments of language, working memory, and the processing of social and emotional cues. Research has shown that the brain’s outer layer, called the cortex, has a larger surface area and is thicker in people with higher socioeconomic status than in poorer people.

Being wealthy has also been linked with having more grey matter (tissue in the outer layers of the brain) in the frontal and temporal regions (situated just behind the ears) of the brain. And we know that these areas support the development of cognitive skills.

The association between wealth and cognition is greatest in the most economically disadvantaged families . Among children from lower-income families, small differences in income are associated with relatively large differences in surface area. Among children from higher-income families, similar income increments are associated with smaller differences in surface area.

Importantly, the results from one study found that when mothers with low socioeconomic status were given monthly cash gifts, their children’s brain health improved . On average, they developed more changeable brains (plasticity) and better adaptation to their environment. They also found it easier to subsequently develop cognitive skills.

Our socioeconomic status will even influence our decision making . A report from the London School of Economics found that poverty seems to shift people’s focus toward meeting immediate needs and threats. They become more focused on the present with little space for future plans—and also tended to be more averse to taking risks.

It also showed that children from low-socioeconomic-background families seem to have poorer stress coping mechanisms and feel less self-confident.

But what are the reasons for these effects of poverty on the brain and academic achievement? Ultimately, more research is needed to fully understand why poverty affects the brain in this way. There are many contributing factors that will interact. These include poor nutrition and stress on the family caused by financial problems. A lack of safe spaces and good facilities to play and exercise in, as well as limited access to computers and other educational support systems, could also play a role.

Reading for pleasure

There has been much interest of late in leveling up. So what measures can we put in place to counteract the negative effects of poverty that could be applicable globally?

Our observational study shows a dramatic and positive link between a fun and simple activity—reading for pleasure in early childhood—and better cognition, mental health, and educational attainment in adolescence.

We analyzed the data from the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development (ABCD) project, a U.S. national cohort study with more than 10,000 participants across different ethnicities and and varying socioeconomic status. The dataset contained measures of young adolescents ages nine to 13 and how many years they had spent reading for pleasure during their early childhood. It also included data on their cognitive health, mental health, and brain health.

About half of the group of adolescents started reading early in childhood, whereas the others, approximately half, had never read in early childhood, or had begun reading later on.

Meet the Greater Good Toolkit for Kids

28 practices, scientifically proven to nurture kindness, compassion, and generosity in young minds

We discovered that reading for pleasure in early childhood was linked with better scores on comprehensive cognition assessments and better educational attainment in young adolescence. It was also associated with fewer mental health problems and less time spent on electronic devices.

Our results showed that reading for pleasure in early childhood can be beneficial regardless of socioeconomic status. It may also be helpful regardless of the children’s initial intelligence level. That’s because the effect didn’t depend on how many years of education the children’s parents had had—which is our best measure for very young children’s intelligence (IQ is partially heritable).

We also discovered that children who read for pleasure had larger cortical surface areas in several brain regions that are significantly related to cognition and mental health (including the frontal areas). Importantly, this was the case regardless of socioeconomic status. The result therefore suggests that reading for pleasure in early childhood may be an effective intervention to counteract the negative effects of poverty on the brain.

While our current data was obtained from families across the United States, future analyses will include investigations with data from other countries—including developing countries, when comparable data become available.

So how could reading boost cognition exactly? It is already known that language learning, including through reading and discussing books, is a key factor in healthy brain development. It is also a critical building block for other forms of cognition, including executive functions (such as memory, planning, and self-control) and social intelligence.

Because there are many different reasons why poverty may negatively affect brain development, we need a comprehensive and holistic approach to improving outcomes. While reading for pleasure is unlikely, on its own, to fully address the challenging effects of poverty on the brain, it provides a simple method for improving children’s development and attainment.

Our findings also have important implications for parents, educators, and policymakers in facilitating reading for pleasure in young children. It could, for example, help counteract some of the negative effects on young children’s cognitive development of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

About the Authors

Barbara jacquelyn sahakian.

Barbara Jacquelyn Sahakian, Ph.D. , is a professor of clinical neuropsychology at the University of Cambridge.

Christelle Langley

Christelle Langley, Ph.D. , is a postdoctoral research associate in cognitive neuroscience at the University of Cambridge.

Jianfeng Feng

Jianfeng Feng, Ph.D. , is a professor of science and technology for brain-inspired intelligence/computer science at Fudan University.

Yun-Jun Sun

Yun-Jun Sun, Ph.D. , is a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Science and Technology for Brain-Inspired Intelligence at Fudan University.

You May Also Enjoy

A Feeling for Fiction

Eight of Our Favorite Asian American Picture Books

How Reading Science Fiction Can Build Resilience in Kids

Changing our Minds

How Reading Fiction Can Shape Our Real Lives

Nine Picture Books That Illuminate Black Joy

- Curriculum and Instruction Master's

- Reading Masters

- Reading Certificate

- TESOL Master's

- TESOL Certificate

- Educational Administration Master’s

- Educational Administration Certificate

- Autism Master's

- Autism Certificate

- Leadership in Special and Inclusive Education Certificate

- High Incidence Disabilities Master's

- Secondary Special Education and Transition Master's

- Secondary Special Education and Transition Certificate

- Virtual Learning Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Video Gallery

- Financial Aid

Reading Revolution: The Science of Reading in Education

The Science of Reading has significant implications for education, as it provides evidence-based guidance for teaching reading skills to students of all ages. By applying the research findings from this field, educators can design effective reading instruction that helps all students develop strong reading skills and reach their full potential.

Looking for a way to improve reading skills in your classroom? Dive into the exciting world of the Science of Reading! Discover the latest and most effective techniques that will enhance your students' comprehension, vocabulary, and overall reading experience. With these strategies, you'll be able to create engaging and empowering lessons that will take your students to new heights of achievement.

What is the Science of Reading?

The Science of Reading refers to the body of research that explores how we learn to read, why some people struggle with reading, and how we can effectively teach reading skills. This field draws on various disciplines, including psychology, linguistics, and neuroscience, to uncover the cognitive and neurological processes involved in reading.

The Science of Reading has its roots in decades of research on the cognitive and neurological processes involved in reading. This research has helped to identify the critical skills and strategies that readers need to become proficient, including phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension.

While the principles of the Science of Reading have been well-established for many years, it has taken time for them to gain widespread recognition in the world of education. In recent years, however, there has been a growing movement to apply evidence-based practices from the Science of Reading to reading instruction in schools.

In the United States, the Science of Reading has gained significant attention and momentum in recent years, particularly in response to persistent gaps in reading achievement among students. In 2019, the National Council on Teacher Quality released a report on teacher preparation programs that found many programs weren’t adequately preparing teachers to teach reading based on the Science of Reading. 1 This report helped to spur a national conversation about the need for evidence-based reading instruction.

In response, several states have taken action to promote the Science of Reading in education. In 2019, the state of Mississippi passed the Literacy-Based Promotion Act, which requires all K-3 teachers to receive training in evidence-based reading instruction, including the Science of Reading. Other states, including Florida and Arkansas, have also passed laws mandating evidence-based reading practices in schools.

The Science of Reading has also gained recognition and influence in other parts of the world. In the United Kingdom, the Education Endowment Foundation has funded a number of studies on the effectiveness of evidence-based reading interventions. In Australia, the New South Wales Department of Education has developed a comprehensive literacy strategy based on the Science of Reading.

The Science of Reading represents a significant shift in the way educators approach reading instruction. By incorporating evidence-based practices from this field, educators can help ensure that all students have the opportunity to become proficient readers.

Five key findings of the Science of Reading

The Science of Reading provides strong evidence-based guidance for teaching reading skills. Research has identified critical reading skills, including phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. Studies have also shown that explicit and systematic instruction in these skills is more effective than implicit or incidental instruction.

Additionally, the Science of Reading emphasizes the importance of early intervention for students who struggle with reading, as well as ongoing assessments and progress monitoring to ensure that all students are making progress.

Phonemic awareness

The ability to identify and manipulate individual sounds in words is a critical precursor to reading. Children who struggle with phonemic awareness may have difficulty sounding out words and comprehending text.

Teaching the relationship between letters and their corresponding sounds (phonics) is a crucial component of reading instruction. A strong understanding of phonics helps children decode unfamiliar words and develop reading fluency.

A robust vocabulary is essential for reading comprehension. Children who are exposed to a rich and diverse range of words from an early age are more likely to become strong readers.

The ability to read quickly and accurately is a hallmark of skilled reading. Fluency is developed through regular reading practice and explicit instruction in reading skills.

Comprehension

The ultimate goal of reading is to understand and learn from the text. Skilled readers use a variety of strategies to comprehend what they read, including making connections between new information and prior knowledge, asking questions, and visualizing.

Shaping the future of learning with SoR

The Science of Reading is shaping the future of education by incorporating evidence-based practices, identifying at-risk students, and designing curriculum materials based on research-based principles. Advocates are working to ensure educators have access to the latest research findings and instructional practices.

Here are some of the ways the Science of Reading is shaping education:

Reading instruction based on evidence

The Science of Reading emphasizes the importance of teaching phonics, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension explicitly and systematically. Educators can use evidence-based instructional practices to help students develop these critical reading skills.

Teacher training and professional development

Many educators have not received comprehensive training in the Science of Reading. To address this gap, teacher training programs and professional development opportunities are beginning to incorporate evidence-based practices from the Science of Reading.

Assessment and intervention

The Science of Reading helps educators identify students who may be at risk for reading difficulties and provide targeted interventions to support their reading development.

Curriculum development

Educators can use the research-based principles of the Science of Reading to inform the design and selection of curriculum materials that support the development of strong reading skills.

Policy and advocacy

The Science of Reading has prompted discussions and debates about education policies related to reading instruction and assessment. Advocates for evidence-based reading instruction are working to ensure educators have access to the latest research findings and instructional practices.

Understanding reading fluency: The frameworks of SoR

The skills and processes that underlie fluent reading are complex and multifaceted and require a thorough understanding to effectively develop and teach.

Two main frameworks commonly used to understand reading fluency are The Simple View of Reading and Scarborough's Rope. 2

The Simple view of reading

The Simple View of Reading is a model that describes reading comprehension as the product of two main components: word recognition (decoding) and language comprehension. This framework emphasizes the importance of developing decoding and language comprehension skills to achieve reading fluency.

Scarborough’s Rope

Scarborough's Rope is another framework that provides a detailed view of the multiple skills and processes required for fluent reading. The framework presents reading as a multifaceted "rope," with individual strands representing various reading sub-skills, including phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. Each strand is interwoven with the others, and all are necessary for strong reading ability.

Together, these frameworks provide a structured and comprehensive approach to analyzing and developing the necessary skills for reading proficiency. By understanding the various components of reading fluency and how they relate to one another, educators can effectively develop targeted interventions and instruction to support students' reading development.

The seven principles of the Science of Reading

The Science of Reading is a body of research that has identified critical principles for effective reading instruction. These principles are based on decades of research into how children learn to read. These principles are also proven to be effective in promoting reading proficiency among students of all backgrounds. Here are seven key principles that every educator should know:

- Reading is not a natural skill and must be explicitly taught.

- Phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension are foundational skills that must be taught systematically and explicitly.

- Direct, explicit instruction is more effective than implicit or incidental instruction.

- Effective instruction must be evidence-based and guided by ongoing assessment and progress monitoring.

- High-quality reading instruction is essential for all students, especially those who are struggling.

- Engaging instruction that includes multiple modes and senses is more effective than passive instruction.

- Early intervention is critical for students who are struggling with reading. 2

By understanding and implementing these principles, educators can help ensure that all students have the opportunity to develop strong reading skills and become confident, capable readers.

Support bi-literate and bilingual students with Science of Reading

Research-based instruction can be a powerful tool in supporting bi-literate and bilingual students, who comprise a significant portion of English learners in public schools across the United States. Over 75% of English learners in public schools are Spanish-speaking (NCES, 2021). 3 Celebrating the existing skills and strengths of these students through research-based instruction helps them develop new skills that support their continued growth.

Effective instruction for bi-literate and bilingual students should also align with the principles of the Science of Reading, which emphasizes evidence-based instruction and the explicit teaching of foundational skills like phonics and vocabulary. Integrating these principles into instruction for bi-literate and bilingual students can help them build strong literacy skills in both languages and become confident, capable readers in all areas.

Research has shown that explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics is particularly important for bi-literate and bilingual students who are learning to read in two languages. This type of instruction can help students develop a strong foundation in both languages and support their ongoing growth as readers.

Similarly, instruction in vocabulary and comprehension strategies can help bi-literate and bilingual students develop strong reading skills in both languages. By focusing on evidence-based instruction that aligns with the Science of Reading, educators can help ensure that all students, including bi-literate and bilingual learners, have access to the tools and strategies they need to become successful readers.

Ultimately, the Science of Reading provides a strong foundation for effective reading instruction in schools and helps ensure that all students, including bi-literate, bilingual students, and native language speakers have the opportunity to become proficient readers.

A deep understanding of their strengths and needs, as well as an ongoing commitment to evidence-based instruction, promotes their continued growth and development and super-charges your impact as an educator.

Learn the latest SoR education skills at KU

Looking to take your career in education to the next level? The Curriculum and Teaching online Master's program at KU is the perfect opportunity to do just that. With a focus on the latest essential skills in the field—including the Science of Reading—our program equips you with the knowledge and expertise needed to make a meaningful impact in today's ever-evolving educational landscape.

With the flexibility of online learning, you can gain these skills while maintaining your busy schedule. Join our community of passionate educators and take the first step towards advancing your career today.

According to U.S. News and World Report, KU offers the #19 Best Online Master's in Education Programs for Curriculum and Instruction. 4

Our admissions advisors are here to answer your questions, Contact us today.

- Retrieved on April 14, 2023, from www.nctq.org/publications/A-Fair-Chance

- Retrieved on April 14, 2023, from scienceofreading.amplify.com/

- Retrieved on April 14, 2023, from www.nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf/english-learners

- Retrieved on April 14, 2023, from usnews.com/education/online-education/university-of-kansas-155317

Return to Blog

IMPORTANT DATES

Stay connected.

Link to twitter Link to facebook Link to youtube Link to instagram

The University of Kansas has engaged Everspring , a leading provider of education and technology services, to support select aspects of program delivery.

The University of Kansas prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, ethnicity, religion, sex, national origin, age, ancestry, disability, status as a veteran, sexual orientation, marital status, parental status, retaliation, gender identity, gender expression and genetic information in the University's programs and activities. The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the non-discrimination policies and is the University's Title IX Coordinator: the Executive Director of the Office of Institutional Opportunity and Access, [email protected] , 1246 W. Campus Road, Room 153A, Lawrence, KS, 66045, (785) 864-6414 , 711 TTY.

Saturday-May-18-2024

Why Read? The importance of instilling a love of reading early.

Definitionally, literacy is the ability to “read, write, spell, listen, and speak.”

Carol Anne St. George, EdD, an associate professor and literacy expert at the University of Rochester’s Warner School of Education, wants kids to fall in love with reading .

“It helps grow their vocabulary and their understanding about the world,” she says. “The closeness of snuggling up with a favorite book leads to an increase in self-confidence and imagination, and helps children gain a wealth of knowledge from the books you share. And it only takes 15 minutes a day of reading together to nurture this growth.”

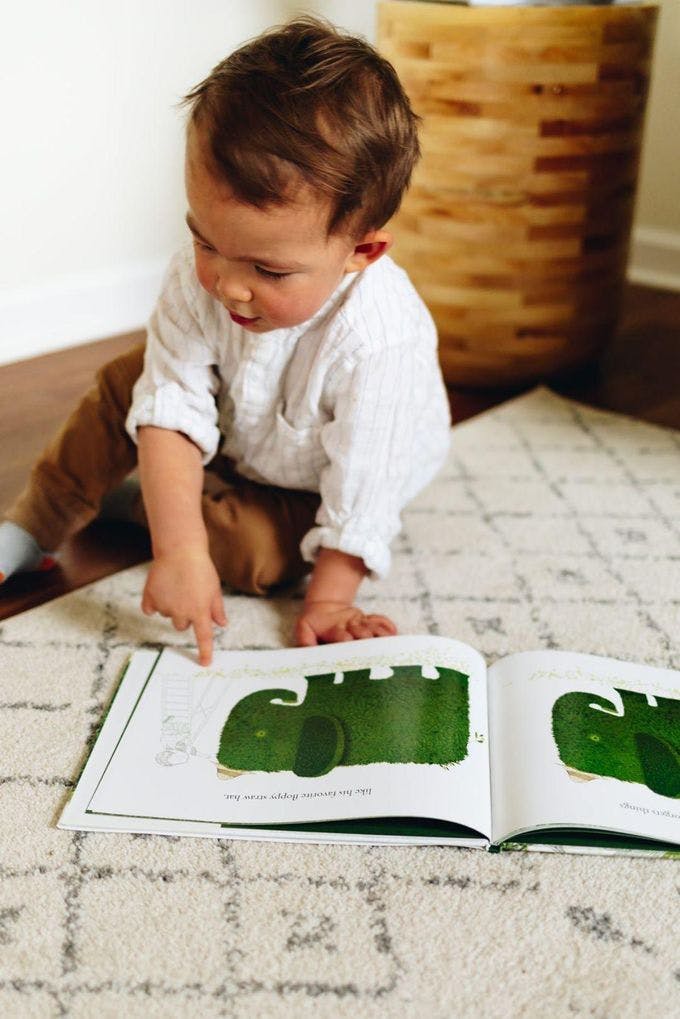

Reading is necessary for learning, so instilling a love of reading at an early age is the key that unlocks the door to lifelong learning. Reading aloud presents books as sources of pleasant, entertaining, and exciting formative experiences for children to remember. Children who value books are more motivated to read on their own and will likely continue to hold that value for the rest of their lives.

Instilling a love of reading early gives a child a head start on expanding their vocabulary and building independence and self-confidence. It helps children learn to make sense not only of the world around them but also people, building social-emotional skills and of course, imagination.

“Reading exposes us to other styles, other voices, other forms, and other genres of writing. Importantly, it exposes us to writing that’s better than our own and helps us to improve,” says author and writing teacher, Roz Morris. “Reading—the good and the bad—inspires you.”

Not only that, but reading is a critical foundation for developing logic and problem-solving skills. Cognitive development is “the construction of thought processes, including remembering, problem solving, and decision-making, from childhood through adolescence to adulthood” (HealthofChildren.com).

Why Focus on Summer?

Summer vacation makes up about one-quarter of the calendar year. This is a time when students face different opportunities based on the social and economic status of their families. An analysis of summer learning (Cooper, Nye, et al., 1996) found that “all students lost mathematics and reading knowledge over the summer…This evidence also indicated that losses were larger for low-income students, particularly in reading.” Summer reading has emerged as a key component of state legislation aimed at promoting student literacy.

The Horizons at Warner program is committed to maintaining and improving student literacy with our kids every summer they return. Nationwide, each affiliate of Horizons National administers reading assessments to students during the first and last weeks of program. Pre-assessment allows our teachers to customize the learning experience on a student-need basis, and post-assessment reinforces this by not only revealing student progress in each area, but by giving insight into how we can improve program design in the future.

Research demonstrates that if a child is not reading at grade level by third grade, their ability to meet future academic success and graduate on time is diminished. Teachers know that up to third grade children are learning to read. After third grade, students are reading to learn. According to St. George, it is impossible to be successful in science, social studies, and even mathematics without a strong foundation in reading and literacy.

On average, we see an improvement by 1 to 3 reading levels in our students here at Horizons at Warner. Keeping true to our mission, these levels will account for all and more of the percentage of summer learning loss that we know our students would face without this kind of academic intervention, and leave our students five to six months ahead of where they would have been without Horizons.

Reading TO children

According to Jim Trelease, author of the best-seller, The Read-Aloud Handbook: “Every time we read to a child, we’re sending a ‘pleasure’ message to the child’s brain… You could even call it a commercial, conditioning the child to associate books and print with pleasure” (ReadAloud.org)

Developing a connection between “pleasure” and reading is crucial. Learning is the minimum requirement for success in every field of life.

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, how reading for pleasure helps students develop academically.

As an educator and a parent, one crucial practice I desire in my students and children is that reading becomes as pervasive and uncontrollable a habit as nail biting or tapping their pen during a lecture. I want students and children to read for the same reason George Leigh Mallory climbed Everest: Because it is there.

The many benefits of reading for pleasure

The American Library Association has also found a strong connection between daily independent reading habits and overall student performance. The ALA cites findings from a number of studies:

- Students who read independently become better readers, score higher on achievement tests in all subject areas, and have greater content knowledge than those who do not

- The more elementary-aged students read outside of school, the higher they scored on reading achievement tests

- Multiple studies support that even a small amount of independent reading increases primary and elementary students’ reading comprehension, vocabulary growth, spelling facility, understanding of grammar, and knowledge of the world

One key factor in the positive influence of this reading seems to be that it is voluntary — students seek out books and participate of their own volition.

Early exposure to reading appears to pay off in that it creates an expectation in children that reading is an essential part of their daily lives, thus the families of pre-readers in preschool, kindergarten, and early elementary must be encouraged to expose them to reading through story time at the library or reading as daily habit in the home.

As students grow up, it appears that some level of independence should be encouraged as it supports their commitment to reading and that later elementary and middle-school students should be spurred to choose their own books within a challenging framework.

The bad news: Americans are reading less

A 2007 study from the National Endowment for the Arts showed that American students are reading less. Over the course of 10 years — 1992 to 2002 — adults showed an overall decline in reading for fun of about seven percent and students showed a similar decline, approximately five percent.

Theories on the reason for the decline abound, but the biggest lies in the idea of displacement. It is thought that American reading times are being sacrificed for television or other hobbies. This drop in reading for pleasure has serious side effects, namely a trickle-down influence on students. Teachers have attempted to rectify the problem by assigning reading homework, only to meet frustration when students are noncompliant.

How educators can support independent reading

As an educator, I am aware of student resistance to homework and hope that rather than an assignment , my students will pick up the habit of daily doses of reading. Research supports the strong positive correlative effect of 20-60 minutes of daily reading.

Subsequent research has found that the best amount may vary; low-level readers benefit from 15-20 minutes whereas high level readers get the greatest benefit from reading 45 minutes or more. Regardless of the best individual amount, research consistently shows that time dedicated to independent reading pays off.

Because teachers have a significant influence on their students’ habits and performance, one solution is to set high expectations of them as readers. I begin each Monday morning by asking my students what they have read over the weekend, which is often rewarded with insightful discussions of newspaper articles and books; I am never afraid to suggest new reading to them. Modeling consistent independent reading for my students, and expecting the same from them, is a key means of influencing their behavior.

My son’s teacher has the same expectations of her class, though she goes a step further and asks them to keep a record of their reading as a method of reflecting upon and rewarding the effort they have put into their daily habits. My daughter’s teacher has his students blog about the reading they’ve done and gives them tangible rewards, marking their progress on the ceiling with paper books.

The rewards encourage competition between classmates and the blog entries pique the interest of other students, who then read the same book and generate discussions with their fellow readers. Regardless of how it is accomplished, the general theme is the same: We collectively expect our students to read and, as students often do, they rise to the expectation.

Monica Fuglei is a graduate of the University of Nebraska in Omaha and a current adjunct faculty member of Arapahoe Community College in Colorado, where she teaches composition and creative writing.

You may also like to read

- 5 Ways To Help Students Improve Reading Skills

- ‘Geometry Pro’ App Helps Students Master the Basics

- How to Use Reading to Teach ELL Students

- How to Determine the Best Reading Program for Your Students

- Five Strategies to Help Improve Students' Reading Levels

- 4 Ways to Help ESOL Students Reach First Grade Reading Levels

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

- Online & Campus Bachelor's in Elementary Educ...

- Online & Campus Doctorate in Education (EdD) ...

- Certificates in Trauma-Informed Education and...

Five ways that reading with children helps their education

Research Associate, Psychology of Education, Coventry University

Disclosure statement

Emma Vardy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Coventry University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

For book lovers, reading to their children may seem obvious. Why would they not want to pass on their love of literature? However, researchers have shown there are more benefits for both adult and child that come with reading than just building a bond – particularly when it comes to education.

A lot of research has been done into the effects of children engaging with literacy related activities at home. Much of this focuses on the early years, and how the literacy environment helps to develop emergent literacy skills. Shared book reading early on stimulates language and reading development , for example.

But the home literacy environment doesn’t stop being important once children have learnt to read. The opportunities that a child has to read at the home, and parental beliefs and behaviours, continue to impact on children’s reading throughout the school years. Here are just five ways that reading with your child can help their general education.

1. It opens up new worlds

Reading together as a family can instil a love of books from an early age. By taking the time to turn the pages together, adults can help children see that reading is something to enjoy and not a chore. Some schoolchildren read because they like it but others do it because they will be rewarded – with stickers in a school reading diary for example. Those children who read because they enjoy it read more books, and read more widely too. So giving your child a love of books helps expand their horizons.

2. It can build confidence

Children judge their own ability to read from observing their classroom peers, and from conversations with parents and teachers. When sharing a book, and giving positive feedback, parents can help children develop what is known as self-efficacy – a perceived ability to complete the specific activity at hand. Self-efficacy has been shown to be important for word reading . Children who think they cannot read will be less inclined to try, but by using targeted praise while reading together, parents can help children develop belief in their own skills.

3. It can build positive reading attitudes

Studies have shown that the more opportunities a child has to engage with literacy based activities at home, the more positive their reading attitudes tend to be. Children are more likely to read in their leisure time if there is another member of the family that reads, creating a reading community the child feels they belong to. Parental beliefs and actions are related to children’s own motivations to read, though of course it is likely that this relationship is bidirectional –- parents are more likely to suggest reading activities if they know that their child has enjoyed them in the past.

4. It expands their language

When reading a book together, children are exposed to a wide range of language. In the early stages of literacy development this is extremely important. Good language development is the foundation to literacy development after all, and increased language exposure is one of the fundamental benefits of shared book reading.

Shared book reading early on can have a long-term benefit by increasing vocabulary skills. And if they encounter a word they don’t understand, they have a grown up on hand to explain it to them in a way that makes sense to them. When children are taught to read while sharing a book, it can improve alphabet knowledge, decoding skills, spelling, and other book-related knowledge (such as how to actually read a book). Doing something as simple as sounding out the letters of a word they do not understand can vastly improve a child’s skills.

5. It can help their speech and language awareness

Formal shared reading can also involve the use of intonation, rhythm and pauses to model what is known as prosody. This is not a skill that is directly taught, but by simply pausing when needed or changing the tone of your voice can help children develop fluency when reading aloud. This is one of the reasons that shared book reading is not just for pre-schoolers. Demonstrating what is involved in reading complex text aloud fluently is very valuable for children of all ages.

You don’t need a lot of money, or even hours of spare time to read with children. Even small efforts can have big benefits. Nor does it have to be just at bedtime. Sharing a book, a magazine or a comic can take place any time of the day.

The most important thing to remember is to have fun. Interest in reading emerges from enjoying it with a parent. If you’re interested and make an effort, it can have a huge impact on a child’s engagement with reading.

- reading skill

- World Book Day

Compliance Lead

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Why Every Educator Needs to Understand the Science of Reading

Teachers of all kinds, from elementary reading specialists to high school science teachers, rely on their students’ literacy abilities to effectively deliver instruction. However, not all teachers receive the same literacy education training—and it’s not all equal. At the forefront of the current literacy conversation is the science of reading, a gold-standard body of research that provides educators with foundational knowledge about how students best learn to read. Understanding the science of reading is key for educators to provide the best possible literacy support to their students.

Nationally recognized author and authority on literacy education, Dr. Louisa Moats, has written widely about the professional learning teachers require, the importance of brain science, and the relationships among language, reading, and spelling.

Q: In your opinion, why do so many students fail to become proficient in reading?

Dr. Moats: Many factors contribute to the “achievement gap” in reading—insufficient early childhood language development, insufficient familiarity with books and print, differences in “wiring” or the brain’s capacity to analyze speech, and so forth. The solution to reading problems, no matter what their origin, is instruction by a well-informed teacher who knows how to help kids overcome those disadvantages.

Q: For decades, you have been a spokesperson for reading research and what we understand about how children learn to read. Can you define the science of reading?

Dr. Moats: The body of work referred to as the “science of reading” is not an ideology, a philosophy, a political agenda, a one-size-fits-all approach, a program of instruction, nor a specific component of instruction. It is the emerging consensus from many related disciplines, based on literally thousands of studies, supported by hundreds of millions of research dollars, conducted across the world in many languages. These studies have revealed a great deal about how we learn to read, what goes wrong when students don’t learn, and what kind of instruction is most likely to work the best for the most students.

Q: Is there evidence that the science of reading can make a difference in reducing reading problems?

Dr. Moats: Yes, those findings about effective instruction are what’s driving our commitment to try to change the status quo. Whole states, as with Mississippi on the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), can make significant gains. But we have a series of studies showing that by the end of first grade, the rate of serious reading problems can be reduced to about 5% or less.

Q: There has been much discussion about the science of reading. For example, Emily Hanford of American Public Media has brought new attention to the concept. Do you feel educators are becoming more familiar with the science of reading and are applying this into their teaching?

Dr. Moats: These days, I have moments when I feel more optimistic. Emily Hanford’s reports have been the catalyst sparking our current national discussion. A growing number of states are confronting what is wrong with the way many children are being taught to read. I’m inspired by the dialogue and courage of the people who know enough about the science of reading to offer a vigorous critique of those practices, programs, and approaches that just don’t work for many children. I am also optimistic about the recent report out from the National Council on Teacher Quality. There’s an increasing trend of new teachers being trained in the components of reading, and I think that many veteran educators are open to deepening their learning.

However, there’s still a long way to go. In general, our teaching practice lags far behind what the research tells us. We consolidated the research on what it takes to teach children to read way back in the early 1990s, and yet today a majority of teachers still haven’t been given the knowledge or instruction to effectively teach children to read.

Q: Some states, like Mississippi and Ohio, are improving student literacy rates across the entire state. To what do you attribute this noticeable rate of improvement in those states?

Dr. Moats: Change in those states and others is a consequence of many converging factors, including unambiguous and consistent leadership from the state level; statewide delivery of professional development (mainly with Lexia® LETRS®) to most teachers; in-class coaching to help teachers apply their professional learning; standards and incentives for both students and teachers, as is manifest on required tests; and support for changes in how teachers are licensed in the first place.

Q: Could you tell us a bit about LETRS and how it supports educators?

Dr. Moats: LETRS (Language Essentials for Teachers of Reading and Spelling) empowers teachers to understand the what, why, and how of scientifically based reading instruction. We focus on teaching essential components including phoneme awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension that should be taught during reading and spelling lessons to obtain the best results for all students. Teaching reading is a complex undertaking because, ideally, all aspects of language are explicitly addressed within a curriculum that is rich and meaningful. Not only do teachers need to understand how kids are learning to read, but also, they must adopt instructional routines, activities, and approaches that can be used to differentiate instruction.

After going through the LETRS training, educators generally have a better sense of what they should be looking for in a reading curriculum and are much more critical consumers. For example, in one state we had a strong group of teachers who learned a tremendous amount about early reading through LETRS. When the state pushed to adopt a particular program, these educators could immediately identify the program’s significant design weaknesses based on what they had learned from LETRS.

Q: What should school and district leaders consider when evaluating programs that support what is known about the science of reading?

Dr. Moats: Here are a few important things for leaders to consider when evaluating programs. First, ideally, there should be explicit instruction in foundational skills for approximately 45 minutes daily that follows a lesson routine: review, explain the concept, provide guided practice, provide more (independent) practice, spell and write to dictation, read decodable text. Then, determine if the instruction in phoneme awareness, phonics, and text reading is informed by knowledge of both the speech-sound system and the orthographic system. Third, examine the scope and sequence for order and pacing of concept introduction. Intervention materials should be aligned with [Tier I] classroom instructional materials but provide more intensive practice. Avoid any program that includes drawing shapes around words, making alphabetic word walls, teaching the “cueing systems” approach (appealing to context to guess at unknown words), or that does not follow a clear scope and sequence where one skill is built upon another.

Q: What advice would you give to district or school leaders who want to change how reading is being taught in their classrooms?

Dr. Moats: Invest in teacher education before investing in specific programs. Any program will be more powerful if knowledgeable, confident teachers are using it. In fact, we have evidence that if teachers do not understand either the content or the rationale for explicit teaching, they are unlikely to get results even if the program they have been given is well designed. The program is only a tool; teachers must know how to use it. It’s a wonderful thing when we understand what we’re doing, why, and for whom we’re doing it.

The science of reading offers educators a deep understanding into how students learn to read. Effective professional learning can help teachers deepen their understanding of literacy instruction and improve student outcomes. Learn more about LETRS and Lexia® Aspire™, a new professional learning program for teachers of older students, to see how the science of reading can accelerate your students’ knowledge acquisition.

Learn more about the ways LETRS prepares educators with the science of how reading and language work together to build strong literacy skills. Visit lexialearning.com/LETRS .

You Might Also Like

Lexia ® LETRS ® Professional Learning

Professional Learning for Educators

Transforming Literacy Instruction: How the Science of Reading Improves Student Outcomes

Only 31% of California’s fourth-grade students read proficiently. During this webinar, your peers share successful strategic plans that improve student literacy achievement by empowering teachers to understand and apply the principles of the science of reading.

State Resources

Put Structured Literacy to Work in Washington’s Classrooms

Instructional tools based in the science of reading and Structured Literacy can help students comprehend and apply literacy skills.Learn more here about how Lexia®‘s evidence-based literacy approach aligns with Washington standards.

A Cambium Learning® Group Brand

The Importance of Reading to Your Children

It’s undeniable that a child’s reading skills are important to their success in school, work, and life in general. And it is very possible to help ensure your child’s success by reading to them starting at a very early age. Continue reading to learn more about the top benefits of reading to children and how reading can support them for the future.

7 Benefits of Reading to Children

Whether you’re reading a classic novel or fairy tales before bed, reading aloud to children can significantly benefit your child’s life. Some benefits reading to children include:

Supported cognitive development

Improved language skills.

- Preparation for academic success

Developing a special bond with your child

Increased concentration and discipline, improved imagination and creativity, cultivating a lifelong love of reading.

Reading to young children is proven to improve cognitive skills and help along the process of cognitive development. Cognitive development is the emergence of the ability to think and understand; it’s “the construction of thought processes, including remembering, problem solving, and decision-making, from childhood through adolescence to adulthood” ( HealthofChildren.com ). It refers to how a person perceives and thinks about his or her world through areas such as information processing, intelligence, reasoning, language development, attention span, and memory.

When you begin reading aloud to your child, it essentially provides them with background knowledge on their young world, which helps them make sense of what they see, hear, and read. According to the IRA/NAEYC position statement (1998) “It is the talk that surrounds the reading that gives it power, helping children to bridge what is in the story and their own lives,” rather than just the vocalization of the words. Introducing reading into your young child’s life, and the conversations that it will prompt, helps them to make sense of their own lives, especially at a young age.

This study of early brain development explains “In the first few years of life, more than 1 million new neural connections are formed every second.” Consider this citation from a study on toddlers’ cognitive development as a result of being read aloud to: “A child care provider reads to a toddler. And in a matter of seconds, thousands of cells in these children’s growing brains respond. Some brain cells are ‘turned on,’ triggered by this particular experience. Many existing connections among brain cells are strengthened. At the same time, new brain cells are formed, adding a bit more definition and complexity to the intricate circuitry that will remain largely in place for the rest of these children’s lives.”

Therefore, the more adults read aloud to their children, the larger their vocabularies will grow and the more they will know and understand about the world and their place in it, assisting their cognitive development and perception.

Reading daily to young children, starting in infancy, can help with language acquisition, communication skills, social skills, and literacy skills. This is because reading to your children in the earliest months stimulates the part of the brain that allows them to understand the meaning of language and helps build key language, literacy and social skills.

In fact, a recent brain scan study found that “reading at home with children from an early age was strongly correlated with brain activation in areas connected with visual imagery and understanding the meaning of language” ( TIME.com )

These cognitive skills and critical thinking skills are especially important when you consider that, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics , more than one in three American children start kindergarten without the skills they need to learn to read. About two-thirds of children can’t read proficiently by the end of the third grade.

Furthermore, while a child will be able to latch onto vocabulary and language he or she hears around him or her, introducing reading into their auditory learning provides another benefit: it introduces the language of books, which differs from language heard in daily life. Whether it’s a children’s book or classic novel, book language is more descriptive, and tends to use more formal grammatical structures.

Prepare for academic success

Early reading with your child is a true one-on-one opportunity for children to communicate with their parents and parents to communicate with their children. It allows children to grow their vocabulary skills with exposure to new words and listening skills they develop from hearing someone read to them that become vital to their academic success.

Studies have shown that “the more words that are in a child’s language world, the more words they will learn, and the stronger their language skills are when they reach kindergarten, the more prepared they are to be able to read, and the better they read, the more likely they will graduate from high school” ( PBS.org ).

Numerous studies have shown that students who are exposed to reading before preschool are more likely to do well when they reach their period of formal education. According to a study completed by the University of Michigan , there are five early reading skills that are essential for development. They are:

- Phonemic awareness – Being able to hear, identify, and play with individual sounds in spoken words.

- Phonics – Being able to connect the letters of written language with the sounds of spoken language.

- Vocabulary – The words kids need to know to communicate effectively.

- Reading comprehension – Being able to understand and get meaning from what has been read.

- Fluency (oral reading) – Being able to read text accurately and quickly.

While children will encounter these literacy skills and language development once they reach elementary school and beyond, you can help jumpstart their reading success by reading to them during infancy and their early toddler years.

While they won’t be able to practice fluency or phonics at that stage, they will get an earlier introduction to phonetic awareness, vocabulary and reading comprehension, all of which will set them up for success as they grow and interact with the world around them.

It goes without saying that reading to your young child on a regular basis can help you forge a stronger relationship with them. When it comes to children, one of the most important things you can do to positively influence their development is spend time with them. Reading to your children provides a great opportunity to set up a regular, shared event where you can look forward to spending time together. With shared reading, your child will trust and expect that you will be there for them. The importance of trust to small children cannot be overstated.

Reading a favorite book to your children not only helps you bond with them, but also gives your children a sense of intimacy and well-being. This feeling of intimacy helps your child feel close to you, and the feelings of love and attention encourage positive growth and development.

With babies specifically, although they may not be able to understand what you’re saying when you read to them, reading aloud provides a level of invaluable nurturing and reassurance. Very young babies love to hear familiar voices, and reading is the perfect outlet to create this connection.