A Review of Formative Language Assessment Research and Implications for Practitioners

- First Online: 04 March 2023

Cite this chapter

- Tony Burner 4

Part of the book series: New Language Learning and Teaching Environments ((NLLTE))

449 Accesses

Formative assessment is any assessment that promotes students’ learning. Learner-centeredness is vital for formative assessment or assessment for learning to succeed. This chapter reviews the most recent research on formative language assessment and sums up the implications for practitioners. Database searches in the largest databases for educational research (ERIC and SCOPUS) with a combination of the keywords “formative”, “language” and “assessment” were conducted. The searches were limited to the last five years (2016–2021) and to peer-reviewed articles only. The analysis categorized the articles’ contents according to the nature of formative assessment (e.g., peer assessment, self-assessment, portfolio assessment), the mode of formative assessment (e.g., written, oral, multimodal), the context of formative assessment (e.g., country, class level, language subject, duration) and the methods used (e.g., observations, interviews, surveys). A final synthesis of the findings resulted in practical advice for practitioners and possible further avenues for research and development projects in schools.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Allal, L. (2016). The co-regulation of student learning in an assessment for learning culture. In D. Laveault & L. Allal (Eds.), Assessment for learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation (pp. 259–273). Springer International Publishing.

Chapter Google Scholar

Andrade, H. L., & Cizek, G. J. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of formative assessment . Routledge.

Google Scholar

Assessment Reform Group. (2002). Researched-based principles of assessment for learning to guide classroom practice . Retrieved from http://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/assessment-reform-group

Bachman, L., & Palmer, A. (1996). Language testing in practice . Oxford University Press.

Bachman, L., & Palmer, A. (2010). Language Assessment in Practice . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5 (1), 7–74.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21 (1), 5–31.

Article Google Scholar

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for learning . Open University Press.

Gan, Z., & Leung, C. (2019). Illustrating formative assessment in task-based language teaching. ELT Journal, 74 (1), 10–19.

Gardner, J. (Ed.). (2012). Assessment and learning (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd..

Hadwin, A., & Oshige, M. (2011). Self-regulation, coregulation, and socially shared regulation: Exploring perspectives of social in self-regulated learning theory. Teachers College Record, 113 , 240–264.

Khodabakhshzadeh, H., Kafi, Z., & Hosseinnia, M. (2018). Investigating EFL teachers’ conceptions and literacy of formative assessment: Constructing and validating an inventory. International Journal of Instruction, 11 (1), 139–152.

McGarrell, H., & Verbeem, J. (2007). Motivating revision of drafts through formative feedback. English Language Teaching Journal, 61 (3), 228–236.

Rea-Dickins, P. (2001). Mirror, mirror on the wall: Identifying processes of classroom assessment. Language Testing, 18 (4), 429–462.

Ross, S. J. (2005). The impact of assessment method on foreign language proficiency growth. Applied Linguistics, 26 (3), 317–342.

Scriven, M. S. (1967). The methodology of evaluation. In R. W. Tyler, R. M. Gagne, & M. Scriven (Eds.), Perspectives of curriculum evaluation (pp. 39–83). Rand McNally.

Swaffield, S. (2011). Getting to the heart of authentic Assessment for learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 18 (4), 433–449.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes . Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language . The MIT Press.

Wiliam, D. (2011). What is assessment for learning? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37 (1), 3–14.

Wiliam, D., Lee, C., Harrison, C., & Black, P. (2004). Teachers developing assessment for learning: Impact on student achievement. Assessment in Education, 11 (1), 49–65.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of South-Eastern Norway, Drammen, Norway

Tony Burner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tony Burner .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Moray House School of Education and Sport, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Sin Wang Chong

King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, Bangkok, Thailand

Hayo Reinders

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Burner, T. (2023). A Review of Formative Language Assessment Research and Implications for Practitioners. In: Chong, S.W., Reinders, H. (eds) Innovation in Learning-Oriented Language Assessment. New Language Learning and Teaching Environments. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18950-0_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18950-0_2

Published : 04 March 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-18949-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-18950-0

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Key Concepts

- The View From Here

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About ELT Journal

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- Introduction

- Conceptualizing formative assessment

- Task-based language teaching

- Formative assessment in task-based language teaching

- Acknowledgement

- < Previous

Illustrating formative assessment in task-based language teaching

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Zhengdong Gan, Constant Leung, Illustrating formative assessment in task-based language teaching, ELT Journal , Volume 74, Issue 1, January 2020, Pages 10–19, https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccz048

- Permissions Icon Permissions

There has been an increasing professional and policy interest in using formative assessment as part of the learning process in the classroom, with increasing numbers of educators regarding it as an effective means of closing the gap between students’ current and desired performance. However, there is a range of different views on what actually constitutes formative assessment and how it may be incorporated into regular classroom teaching. Furthermore, formative assessment is often misconstrued in reality, and teachers face considerable challenges in implementing formative assessment in their daily classes, particularly in the ESL teaching context. The purpose of this article is, therefore, to review how formative assessment has recently been discussed in both general education and L2 assessment fields, and to illustrate how formative assessment can be implemented in task-based language teaching in the daily ESL classroom.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-4526

- Print ISSN 0951-0893

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Formative Assessment

Introduction, the evolution of formative assessment.

- Theory and Formative Assessment

- Formative Assessment and Student Achievement

- The Role of Feedback in Formative Assessment

- Formative Assessment Process and Practice in the Classroom?

- Formative Assessment as Part of a Balanced Assessment System

- Developing Teacher Capacity for Formative Assessment

- National and International Reports

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Academic Achievement

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Gender, Power, and Politics in the Academy

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- Non-Formal & Informal Environmental Education

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Formative Assessment by Leslie W. Grant , Christopher R. Gareis , Sarah P. Hylton LAST REVIEWED: 29 July 2020 LAST MODIFIED: 26 May 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0062

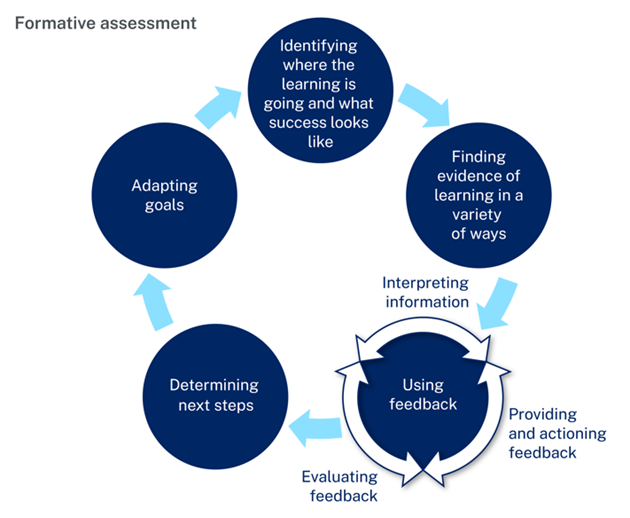

Formative assessment has received international attention as an instructional approach that has great potential to improve teaching and learning. The concept has roots in educational evaluation practices and has evolved over time, from a focus on formative evaluation to formative assessment or assessment for learning. Although one singular definition has not emerged among researchers, scholars, and practitioners, shared themes across the sources suggest the emergence of common elements of formative assessment: Formative assessment is a cyclical process that involves interactions among teachers and students. Those interactions include prompting thinking and eliciting information. The information is then gathered and analyzed by both the teacher and the students. Finally, teachers and students provide feedback, and the student makes use of the feedback to either confirm or improve their understandings and/or skills. Research into these common elements will continue to inform our evolving understanding of the formative assessment process. This article first addresses the evolution of formative assessment and the theories that have informed the conceptualization of and research into the formative assessment process. The work of the Assessment Reform Group in the 1990s catapulted formative assessment into the spotlight for teacher education programs, teacher professional development, and educational research primarily due to claims of the impact on student achievement. This article provides often cited, seminal research studies claiming to provide evidence of a link between formative assessment and student achievement. Being central to the formative assessment process, works addressing the role of feedback are explored. The next two sections focus on works that have emerged to support implementation of the formative assessment process in the classroom and works to support the development of balanced assessment systems that include formative assessment at both the classroom and the school system levels. Over time, professional organizations have developed and revised standards to address both uses of assessments, to include formative assessments, in the classroom as well as standards for the development of educator knowledge, skills, and dispositions. The standards provided in this article represent the most referenced standards in the assessment and evaluation field. Finally, national reports from the United States and international reports noted in the final section provide insight into evolving policies and practices and signal the emergence over time of agreement on common elements of the formative assessment process.

Formative assessment has become a mainstay in educational discourse and practice. The first reference to the term “formative” has roots in curriculum development and evaluation. Cronbach 1963 refers to the idea of using evaluation as a tool for improving curricular programs. Scriven 1967 builds on Cronbach’s work in proposing the term “formative” as a way of clarifying the roles of evaluation. Bloom 1971 applies Scriven’s definition to the process of teaching and learning, by using the term to describe a way of improving student learning. Bloom, et al. 1971 links the idea of formative evaluation to the instructional approach of mastery learning as an instructional process that includes the use of data to improve both teaching and learning. During the 1980s and 1990s, educational researchers continued to expand on the ideas and theories proposed, and use of the term “formative evaluation” was replaced by the term “formative assessment.” Sadler 1989 builds on the definitions previously offered, highlighting the role of the student in the assessment process and viewing student self-assessment as critical to improved student learning. First published in 1994, Gipps 2012 documents the shift in how the educational community views assessment, including a shift from a psychometric view to the development of assessments and use of assessment data by teachers to guide instruction. The is distinguished as a classic text and it was thus reprinted in 2012. During the 1990s and the early 2000s, the Assessment Reform Group in the United Kingdom focused on the development of formative assessment practices and provided a definition of formative assessment. Written by Assessment Reform Group members, Harlen and James 1997 affirms that a distinction between formative and summative assessment is needed due to the confluence of these two roles of assessment in the field. The term “assessment for learning” was first coined in Assessment Reform Group 1999 to further delineate the differences between the goals and roles of summative and formative assessment and extended by the vision of assessment not only for learning but also of learning and as learning found in Earl 2003 . Stiggins and Chappuis 2012 highlights the importance of assessment for learning and situates it as the key practice of classroom assessment.

Assessment Reform Group. 1999. Assessment for learning: Beyond the black box . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ., School of Education.

In this text, the authors first coin the term “assessment for learning” to distinguish it from the more conventional and long-standing notion of “assessment of learning.” The purpose of assessment of learning is to verify student learning, whereas the purpose of assessment for learning is to contribute to the acquisition, or forming, of learning.

Bloom, B. S. 1971. Learning for mastery. In Handbook on formative and summative evaluation of student learning . Edited by B. S. Bloom, J. T. Hastings, and G. F. Madaus, 43–57. New York: McGraw-Hill.

This book chapter connects the concept of mastery learning with formative evaluation. The author indicates that formative tests are used to gauge student learning, to diagnose difficulties, and to design interventions so that the student achieves mastery of a unit of instruction.

Bloom, B. S., J. T. Hastings, and G. F. Madaus. 1971. Formative evaluation. In Handbook on formative and summative evaluation of student learning . Edited by B. S. Bloom, J. T. Hastings, and G. F. Madaus, 117–138. New York: McGraw-Hill.

A book chapter that builds on Scriven’s definition of formative evaluation in curriculum development and implementation. The authors apply this definition to planning, instructional delivery, and student learning, with guidance on how to create assessments and use assessment data.

Cronbach, L. J. 1963. Course improvement through evaluation. Teacher’s College Record 64.8: 672–683.

In perhaps the earliest intimations of the concept of formative evaluation, Cronbach calls for an evaluation process that focuses on gathering and reporting information to use in guiding decisions in an educational program and in curriculum development while the program can be modified.

Earl, L.?M. 2003. Assessment as learning: Using classroom assessment to maximize student learning . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

The author describes a vision for the future of assessment as being composed of assessment of,for , and as learning. Principles of assessment for learning are illustrated with examples from multiple subject areas and grade levels. Assessment as learning focuses on the role of students as active participants in their own learning, which the author describes as virtually absent from most classrooms at the time of publication of the text.

Gipps, C. V. 2012. Beyond testing: Towards a theory of educational assessment . Classic ed. London: Routledge.

First published in 1994 in London by the Falmer publishing house, this book explores the evolution of how assessment is viewed. The author delineates the move from the psychometric view of assessment and a focus on testing to a classroom view of assessment that includes the development of a culture of assessment and a wider range of assessment tools and uses.

Harlen, W., and M. James. 1997. Assessment and learning: Differences and relationships between formative and summative assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 4.3: 365–379.

DOI: 10.1080/0969594970040304

In this article, the authors focus on providing clarity on the differences between formative and summative assessment. In addition, the authors provide conditions by which formative assessments can be used for summative purposes. These conditions include the use of external criteria for assessing student learning, viewing the results of formative assessment holistically across a period of instruction, and ensuring inter-rater reliability across teachers.

Sadler, D. R. 1989. Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science 18.2: 119–144.

DOI: 10.1007/BF00117714

In this article, Sadler focuses on the judgments made about the quality of student work, discussing not only who makes such judgments but also how they are made and used. He posits that students must be able to appraise their own work and draw on their own skills to make modifications to their learning, thus alluding to the intersection of formative and self-assessment. The importance of feedback is emphasized.

Scriven, M. 1967. The methodology of evaluation. In Perspectives of curriculum evaluation . Edited by R. W. Tyler, R. M. Gagné, and M. Scriven, 39–85. Rand McNally Education. Chicago: Rand McNally.

In this monograph, Scriven proposes the use of the terms “formative” and “summative” to provide clarity about roles and goals within the evaluation community. The role of formative evaluation is to make improvements while the focus of the evaluation can still be improved. By comparison, summative evaluation is used to determine the merit or worth of an educational program.

Stiggins, R. J., and J. Chappuis. 2012. An introduction to student-involved assessment FOR learning . 6th ed. Boston: Pearson.

This classic textbook on classroom assessment may be the earliest example of a text that uses assessment for learning as the organizing conceptual framework for the principles, strategies, and techniques that it presents. This textbook is written for pre-service teachers, and it accentuates the intentional involvement of students in gauging their own learning.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Mixed Methods Research

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Program Evaluation

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.39.149.46]

- 185.39.149.46

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT IN LANGUAGE TEACHING

Related Papers

Formative Assessment

John "Jack" States

Effective ongoing assessment, referred to in the education literature as formative assessment or progress monitoring, is indispensable in promoting teacher and student success. Feedback through formative assessment is ranked at or near the top of practices known to significantly raise student achievement. For decades, formative assessment has been found to be effective in clinical settings and, more important, in typical classroom settings. Formative assessment produces substantial results at a cost significantly below that of other popular school reform initiatives such as smaller class size, charter schools, accountability, and school vouchers. It also serves as a practical diagnostic tool available to all teachers. A core component of formal and informal assessment procedures, formative assessment allows teachers to quickly determine if individual students are progressing at acceptable rates and provides insight into where and how to modify and adapt lessons, with the goal of making sure that students do not fall behind.

Studies In Educational …

Anton Havnes , Olga Dysthe

Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness

Jason Harlacher

Teaching and learning English

Tony Burner

As is evident from chapter 17 in the book, assessment is a central aspect of the learning process. In this chapter, Tony Burner takes a closer look at formative assessment and how it can be incorporated in daily classroom routines. After discussing the concept of formative assessment and self-assessment, he explains the importance of formative feedback. Then he explores three forms of formative assessment, namely process writing, peer assessment and portfolio assessment.

Educational Assessment

Dylan Wiliam

welly ardiansyah

The use of formative assessments, or other diagnostic efforts within classrooms, provides information that should help facilitate improved pedagogical practices and instructional outcomes. However, a review of the formative assessment literature revealed that there is no agreed upon lexicon with regard to formative assessment and suspect methodological approaches in the efforts to demonstrate positive effects that could be attributed to formative assessments. Thus, the purpose of this article was to set out to clarify the terminology related to formative assessment and its usage

Bernie Moreno

Sharon Gedye

Journal of Education and Practice

Dr Ved K U M A R Mishra

Muhammad U Farooq

In principle, summative assessment (SA) and formative assessment FA are employed in educational settings for distinctly different purposes. The former is used mainly for administrative purposes and the latter for promoting students' academic competence and developing their self-learning skills. Strong evidence, however, could be traced in empirical research available suggesting that in some settings the difference between the two is virtually unobtrusive. This paper will highlight formative assessment processes in a Saudi public university. Besides, it will investigate the extent to which formative assessment proved formative in raising the standard of students' learning, and how it was dealt with differently from its summative counterpart. The findings of this study are based on a mixed method enquiry. Both quantitative and qualitative data were gathered from English-major students of the university. A survey was distributed among 600 students; of whom 465 returned their responses. The numerical data were analysed using SPSS software for mean and standard deviation. In addition, eight individual and four focus-group interviews were conducted. For further triangulation of the data, eighteen lessons of five different teachers were observed. The qualitative data were analysed employing a qualitative data analysis (QDA). The results indicated that, practically, there was no observable difference between how the students studied for the two kinds of assessment and how these different modes of assessment impacted on their learning. In addition, the two types of assessment were found to be dealt with in a highly similar fashion. Students did not receive adequate feedback. Therefore, the study has clear implications for the institutional approach toward formative assessment. Likewise, this critical state of affairs necessitates a complete overhaul in teachers and students' beliefs concerning formative assessment.

RELATED PAPERS

Meroul Imran

Classica - Revista Brasileira de Estudos Clássicos

Paulo Vasconcellos

Bopaya Bidanda

Mahdi Davari

Psycho-Oncology

William Breitbart

Brazilian Journal of Health Review

Rafaela Ramos Dantas

Environmental Conservation

Jérôme Mathieu

Rev. Colomb. de Computación

Jonas A. Montilva C.

Journal of Intelligent Systems

shah hussain

The Journal of Organic Chemistry

Mauricio Vidal Fonseca

ASGHAR : Journal of Children Studies

siti Isyanti

Gabriel Trueba

Nora Castro

Chibuife Isaac Chukwuebuka

The oncologist

mario valdes

Beatriz Gomes

Frontiers in Ophthalmology

Meg Bentley

Bulletin of the History of Archaeology

Peter Rowley-Conwy

Marsanda kahi Timba

Brain Research

Hiroyoshi Miyakawa

Cell biology and development

Helen Gebremedhen

Journal of Algebra

Patricia Palacios

David Hanson

Ebook - IX Congresso nacional de educação

Jairo Barduni , Campbell Rocha , Raquel Pereira

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Formative Assessment of Language: an Essential Feature of Curriculum Design

Effective teachers evaluate and respond to students’ learning both in the moment and in a systematic, ongoing way. They make as-needed adjustments to their instruction and encourage students to reflect on their learning by providing timely and actionable feedback. This process is referred to as ‘formative assessment’.

Robert Stake, an evaluation researcher once said, “When the cook tastes the soup, that’s formative; when the guests taste the soup, that’s summative” (quoted in Scriven, 1991). In other words, rather than assessment of learning, formative assessment is assessment for learning and it is essential to the learning process.

Because multilingual learners (MLL) have to learn new content and new language simultaneously, teachers need to assess and provide timely and actionable feedback on students’ language as well as their content knowledge. When teachers have the resources and knowledge to analyze student language and identify next steps in their language developement, they can refine instruction to help students pay attention to and engage actively in their own learning.

Effective materials are designed to include formative assessment that:

- guides teachers to look for evidence of content and skills learning,

- plans for how to respond to learning needs with suggested scaffolds and modifications,

- helps teachers to demonstrate how to share learning goals with students,

- helps students understand how their learning is progressing (metacognition), and what to do next to support their continued progress.

- Examples include turn and talks, quick writes, student identification and correction of errors, gallery walks, etc.

These same formative assessment activities can also be used to understand language learning and guide teachers to collect samples of student language. Teachers can analyze the samples based on language targets related to the content and support the next steps in students’ language development. The language analyzed needs to occur naturally as part of the learning activities. This means students need opportunities to practice language in conversations and writing about content so they can make the language their own.

All students, regardless of language background must be explicitly taught language in a way that builds on their current reading, writing, listening and speaking skills within the content area, but it is especially important for those learning in a new language.

For many teachers, learning to look for and respond to language evidence will mean a significant shift in instructional practice. This is why formative assessment of language and content must be designed into instructional materials.

Designing for Effective Formative Assessment of Language

How can content developers approach design with a language lens?

First, content developers must analyze what students need to DO with language (in addition to concepts and skills) as they proceed through tasks and lessons and create language goals and success criteria. Just as units are organized sequentially to build content area knowledge and skills, the lessons should build on students’ content area language so that they produce increasingly more precise language forms and functions . When content developers design materials with an initial analysis of language demands for each unit, then there are opportunities to build into the lessons, relevant and responsive scaffolds and supports that teachers can use to understand students’ knowledge, skills, and language use.

Formative Assessment in Unit Design

Let me provide an example. In a middle school science unit on light and matter (spectroscopy), the unit goal may be for students to develop a model and explanation for how light interacts with an object’s material so that we see differently under different conditions. Each lesson has a goal and success criteria organized in a sequence that facilitates students’ eventual conceptual mastery and ability to demonstrate their understanding and apply it in a summative unit assessment. Students may need to analyze phenomena and describe that phenomena in writing and illustration, and make inferences about how that phenomena relates to other phenomena.

Some of the language demands of that unit might include:

- learning and using science terms (light waves, frequencies, reflect, refract, bend),

- developing the linguistic structures of analysis (inherent in science and engineering practices )

- describing their observations of light and matter, and

- making inference statements based on students’ observations.

Teachers should focus on those critical language features that students need to engage in reading, talking and writing about light and matter in science. Lessons should progress from providing opportunities for students to use their own language resources (including home language), to enhancing their language with more specialized science terminology and language and literacy patterns associated with the content and skills. The unit must build in many opportunities for students to see, use, and practice the specialized science language so that the words, phrases, patterns become part of their language repertoire.

There are many assessment tools and routines that can be built into and across the curriculum. For example, guidance for collecting language observation notes with specific look fors or listen fors on each student’s performance in group work or presentations will help teachers notice patterns in language related to the goals of the lesson.

In the science unit mentioned above, look fors / listen fors might guide teachers to notice and give feedback on the following:

- students’ word choices related to light and matter throughout the unit,

- words or phrases typically used in descriptions (e.g. for example, involves, can be defined, for instance).

- features of descriptive text structure (e.g. main idea, unique features, supporting ideas, examples), and

- sentence structures typical in written analysis of phenomena.

Guidance for collecting written work samples and using a language lens while assessing those samples will help teachers respond with language scaffolds, direct instruction, or other responsive teaching methods. Routines such as Stronger and Clearer or Collect and Display can allow for teacher, self and peer assessment.

Teachers should not focus on teaching correct language use. Too much focus on correctness can inhibit MLL participation and confidence. As the linguist James Gee would say, we need to apprentice students to the Discourse community. Effective guidance helps teachers “apprentice” students by engaging them in activities that develop their language awareness and help them discover and learn how language is used within the content.

Formative assessment guidance is essential if teachers are to more effectively adapt and respond to what students are saying and doing as they develop content area language and content skills and knowledge simultaneously. Only through intentional design of materials, and support for effective implementation can language development be built into teachers’ instructional practice and students’ classroom experience.

---------------------------------------

Resources for Content Developers:

- This Fall, ELSF will hold its annual in-person content developer institute, Demystifying Curricular Design for Multilingual Learners . Instructional materials’ designers and writers can expect to dive more deeply into how to design effective formative assessments of language and content.

- ELSF recently updated our Do’s and Don’ts of Formative Assessment to make them supportive for content developers in designing curriculum. Download the PDF now.

Renae Skarin has almost 30 years of experience working with English learner and minoritized populations through research, advocacy, and program development and implementation with educators nationwide and abroad. She currently serves as the Senior Advisor for Content at the English Learners Success Forum (ELSF) where she leads its research efforts to identify strategies and develop resources for improving education policies and practices with regard to high quality instructional materials for multilingual learners. Before joining ELSF she served as an associate researcher at Understanding Language at Stanford University. She received her M.A. in Second Language Studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and did Doctoral studies in Educational Linguistics at Stanford University.

QUESTIONS? COMMENTS?

Please get in touch with us..

- Headphones for Schools

- Customer cases

- Become a reseller

Language Teaching Strategies , Tips for Language Teachers

Language skills assessments: formative and summative assessment.

More about us

In order to understand the progress that language learners are making, language educators should ensure that language skills assessments are a key part of their regular teaching programme. Although many people incorrectly assume that assessment only refers to taking a test, assessment is much broader than that and often takes place in the classroom without much fanfare.

This blog post looks at the two main types of language skills assessments in detail: summative assessment and formative assessment. We will explore how each type can contribute to an educator’s understanding of their students as well as providing some tips and tricks to help teachers maximise the effectiveness of the assessment they undertake.

What is summative assessment?

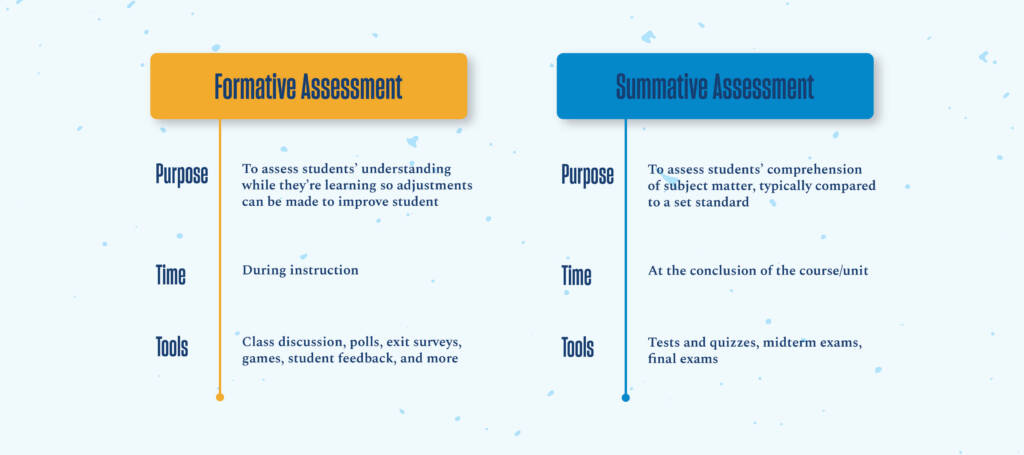

Summative assessment is described by Irons 2007 as “any assessment activity which results in a mark or grade which is subsequently used as judgment on student performance.” It is therefore usually used to summarise what a learner has achieved at the end of a period of time, relative to the learning aims and any relevant standards.

The period of time is, of course, dependent on what the teacher wants to find out. The summative assessment could therefore occur at the end of a topic, at the end of a term or at the end of a year. The format of the summative assessment is also determined by the educator – it could be a written test, a reading observation, a conversation with a native language speaker or a collaborative group task. As such, in the context of language teaching, the output of the summative assessment should be recorded in an appropriate format, whether that’s a written response or an audio recording.

Whatever format is used, the assessment will show what the student has learnt at/by a particular point in time. This can then provide individual and group data that is used to track progress and inform stakeholders (e.g. students, senior leaders, parents etc.).

However, because summative assessment only serves to reflect what a student has learned in the past (Ahmed, Ali & Ali Shah, 2019), it does present some drawbacks for the student. As Myers 2019 states the most significant issue is that very little is usually done to help learners to address the deficiencies identified in the summative assessment. The class simply marches onto the next topic and the gaps in student achievement continue to broaden.

Furthermore, this assessment format is also frequently characterised as relying on grades and scores. It often does not provide a complete picture of the student’s level of knowledge beyond that demonstrated in the assessment.

What is formative assessment?

The second major type of assessment type is known as formative assessment. This was defined by Irons in 2008 as: “Any task or activity which creates feedback (or ‘feedforward’) for students about their learning. Formative assessment does not carry a grade which is subsequently used in summative judgment”. Ahmed, Ali and Ali Shah (2019) take this a step further by arguing that formative assessment does not only support students, it also “informs teachers about how to adjust their teachings, appropriately.”

As such, formative assessment usually takes place at the same time as the teaching is being delivered. Conducting assessments on an ongoing basis allows learners and educators to assess progress more frequently. Teachers are then better able to see what concepts or skills have been mastered, or not, and can then restructure their content / lessons accordingly.

A formative assessment may actually look very similar to the summative assessment outlined above – they might even be a formal test. The difference is that the results are not always recorded or shared with others. They’re simply used to highlight areas that require further work, which is then incorporated into future lessons and activities.

However, formative assessments do also have drawbacks.They may act to demotivate those learners who grasp concepts more quickly and who have to sit through repeated teaching on the same topics. Myers 2019 also expresses concern that formative assessment can be incredibly time consuming for teachers and can lead to increased workload and unnecessary stress.

How do these language skills assessment types work together?

Of course, it is possible for the two forms of assessment to work powerfully together and language educators should ideally seek to balance both forms of assessment throughout their language courses. At the very simplest level, the use of summative assessment techniques ensures that students take their studies seriously and do not use continuous assessment as an excuse to slack off. Furthermore, the results from summative assessments can (and should!) be used formatively by both students and educators to guide their efforts and activities in subsequent courses.

It is also possible for educators to design formative assessments so that they scaffold learning (and assessment) and contribute to an overall summative task. This lowers the workload on the students and provides them with necessary feedback to improve their final performance. Conversely, summative assessments can also be completed and complemented with outputs / resources that enable teachers to use the results to inform future teaching and learning – they therefore deliver a clear formative benefit.

Tips to implement an effective language learning assessment system in your classroom

- As always, the better you know your students and their preferred learning styles, the more accurate and effective your assessments will be. To that end, talk to them and trial the different assessment approaches individually, and in combination, to work out what’s most effective for your setting and classes.

- In either instance, take the time to explain the rationale behind your choice of assessment model clearly to students. It can also be worth emphasising the need for regular assessment and the benefits that it brings to them as learners – it’s not just testing for testing sake after all! And always be open with students about your evaluation, rubrics, and mark schemes. They should be completely clear about what you’re looking for and how every assessment will be marked.

- Bear in mind the Swedish and Norwegian word “ lagom ”, when planning your assessments. It means “just the right amount” and a balanced approach will certainly be welcomed by your students. Try to use a variety of different activities, tests and outputs to engage all students. Similarly aim to avoid having one single massive summative assessment that carries a disproportionate amount of weight in students’ final grade. No one needs the extra stress in their lives!

- Whatever assessment approach you follow, do try and mark it promptly. Otherwise students will have forgotten their answers and will have already moved on to the next topic in the curriculum. On that point, make sure to keep a record of student grades and always provide an opportunity to go through the assessment with students to address any gaps in understanding before moving on.

- Linked to the above, try to emphasise the positive elements of their performance rather than highlighting what they got wrong. Where possible, always encourage and motivate them to do even better next time.

- And finally, explore how concepts of peer evaluation and self-assessment could be used in your classroom. In peer evaluation, students are asked to review each other’s work and to identify areas for further development and focus. In the latter, students are encouraged to critically review their own work, to consider how they could improve and what gaps in their knowledge need to be addressed.

Whatever assessment approach you use to measure your students’ knowledge, Sanako’s market-leading tools include a wealth of unique features that help language educators teach languages more efficiently and more successfully. It’s why the world’s leading educational institutions choose Sanako as their preferred supplier to support online and in-person language lesson delivery.

If you are interested in learning more about how Sanako products support language teachers and students and would like to see how they could benefit your institution, book a FREE remote demo now to see them in action.

Feature request

Become a partner, cookie consent, privacy overview.

- Our Mission

Using Formative Assessment to Measure Student Progress

Teachers can use the feedback they gain from assessing to drive instructional outcomes and help students understand what success looks like.

Perhaps my favorite commentary on formative assessment is this analogy offered by education professor Dylan Wiliam : “I flew back from Seattle a few weeks ago. Just imagine what the pilot would have done if he would have flown east for nine hours and then after nine hours he’d say, ‘It’s time to land.’ So he’ll put the plane down and he’ll ask, ‘Is this London?’ And of course, even if it’s not London, he says, ‘Well, everybody’s gotta get off, because I have to get off to the next journey.’ And that’s exactly the way that we’ve assessed in the past.”

Formative assessment, implemented correctly, is a continuous measure of student success throughout any unit of study. When we provide students with quick, real-time information about their progress, they gain valuable knowledge that transcends any grade.

Ensure that grades accurately measure student performance

Although many teachers would love to abandon grades from an ideological perspective, that is not usually possible given school or district constraints. When thinking about grading, teachers can become mired in details that distract from the overall purpose of formative assessment. For example, some education experts argue that assessments cannot be formative if any data is recorded in the grade book.

By placing too much emphasis on grades over performance, however, this perspective overlooks the most important benefits that formative assessment produces: the delivery of “no secrets” instruction that is aligned to transparent and equitable feedback . To that end, formative assessments can be graded, but with two provisos:

- Any formative grade should not be weighted heavily enough to have a significant impact on overall success, and students must also have the opportunity to reassess their work and make improvements. Otherwise, the grade is summative, not formative.

- Formative grades must be a true reflection of student success toward a goal. If they are arbitrary or placed in the grade book for completion, the entire formative process is compromised.

In essence, formative assessment supports the idea that process is more important than product; therefore, the ultimate goal is centered on learning, not a grade. Any grade that either is given as a formality or is not grounded in criteria for success cannot be formative.

Understand the purpose of formative assessment

As education writer Stephen Chappuis explains, formative assessment is designed to deliver information about student progress during instruction. Thinking back to Dylan Wiliam’s comparison of the assessment process to a flight plan, consider the difference between a classroom in which there is little to no transparency and one in which “no secrets” learning outcomes are clear to all. In Classroom A, students read a short article about why exercise is important. The teacher explains that their task is to read silently and then fill out short-answer responses to the questions.

After class, the teacher collects their work, checks that students have answered the questions, and enters a grade in the “completion” category. While the teacher may feel that she has done something to help students make progress, she has only provided an activity that is devoid of any opportunity for assessment. Therefore, she has no way of determining whether students reached a learning goal that was never explicitly communicated to them.

In Classroom B, the teacher has the same content and curricular focus, but her process is different as she begins by explicitly sharing the desired learning outcome: “Today, we will examine the reasons that exercise is considered beneficial.” To begin, students sit in groups to read an assigned section of the article about the importance of exercise. Then, using a jigsaw-style method , students move into different groups so that each member can teach the rest of their classmates about what they learned in their assigned portion. At the end of the class, students complete an exit ticket with the following prompts:

- Share the reasons listed in the article that exercise is important, writing a brief explanation for each reason (one or two sentences).

- Of the reasons given in the article about the importance of exercise, which one do you most agree with, and why? Fully explain your answer.

The teacher in Classroom B can determine, based on the answers on the exit ticket, how fully students understood the objective of the day and develop next steps that accurately reflect progress toward learning outcomes.

Clearly, the teacher in Classroom B is engaging in formative assessment that provides insight into where her students are in terms of their learning. When instruction is planned with the outcome at the forefront of focus, formative data is far more likely to reflect accurate measures of success. However, when students complete tasks for a grade that does not connect to any kind of specific target, there is no way to determine where they stand in relation to the goal.

Remember that feedback, not grades, should drive instruction

Teachers often call grades “feedback,” but the truth is that an evaluative measure like a numerical score does not tell students that much about their progress toward a skill or standard, nor does a letter grade. However, effective feedback protocols based on clear, student-friendly criteria demystify how success on any given assignment is defined.

Going back to the kids in Classroom B who are learning about the importance of exercise, imagine that their formative assessment (in this case, an exit ticket) includes the following criteria for success:

- You have accurately summarized the ideas in the article about the importance of exercise.

- Your response fully answers both questions in complete sentences.

- You have provided details that help to explain what reasons for exercise are the most meaningful to you.

If students have this list before they complete the formative assessment, they fully understand what a successful product should incorporate. Then, the teacher can point out where they are not yet seeing success in the feedback with comments like “You have not yet mentioned your own reasons that exercise is important, which is a necessary step in showing that you can apply the concepts in this article to your own experience.”

With a process like the one above, the formative assessment is easily streamlined, as the teacher directly indicates which criteria have been met and which need improvement. For example, sorting students into categories of “meets” and “not yet” provides a helpful snapshot of where the class generally stands with reaching academic goals.

Ultimately, the goal of formative assessment is for teachers to clearly indicate a leaning target so that students can accurately attribute their academic performance to clear criteria for success with aligned, streamlined feedback. This helps us meet our true goal: helping kids understand what makes them successful so they can continue to grow and thrive.

What about your thoughts on the role of grades in formative assessment—do you use them? Why or why not? Answer in the comments.

Created by the Great Schools Partnership , the GLOSSARY OF EDUCATION REFORM is a comprehensive online resource that describes widely used school-improvement terms, concepts, and strategies for journalists, parents, and community members. | Learn more »

Formative Assessment

Formative assessment refers to a wide variety of methods that teachers use to conduct in-process evaluations of student comprehension, learning needs, and academic progress during a lesson, unit, or course. Formative assessments help teachers identify concepts that students are struggling to understand, skills they are having difficulty acquiring, or learning standards they have not yet achieved so that adjustments can be made to lessons, instructional techniques, and academic support .

The general goal of formative assessment is to collect detailed information that can be used to improve instruction and student learning while it’s happening . What makes an assessment “formative” is not the design of a test, technique, or self-evaluation, per se, but the way it is used—i.e., to inform in-process teaching and learning modifications.

Formative assessments are commonly contrasted with summative assessments , which are used to evaluate student learning progress and achievement at the conclusion of a specific instructional period—usually at the end of a project, unit, course, semester, program, or school year. In other words, formative assessments are for learning, while summative assessments are of learning. Or as assessment expert Paul Black put it, “When the cook tastes the soup, that’s formative assessment. When the customer tastes the soup, that’s summative assessment.” It should be noted, however, that the distinction between formative and summative is often fuzzy in practice, and educators may hold divergent interpretations of and opinions on the subject.

Many educators and experts believe that formative assessment is an integral part of effective teaching. In contrast with most summative assessments, which are deliberately set apart from instruction, formative assessments are integrated into the teaching and learning process. For example, a formative-assessment technique could be as simple as a teacher asking students to raise their hands if they feel they have understood a newly introduced concept, or it could be as sophisticated as having students complete a self-assessment of their own writing (typically using a rubric outlining the criteria) that the teacher then reviews and comments on. While formative assessments help teachers identify learning needs and problems, in many cases the assessments also help students develop a stronger understanding of their own academic strengths and weaknesses. When students know what they do well and what they need to work harder on, it can help them take greater responsibility over their own learning and academic progress.

While the same assessment technique or process could, in theory, be used for either formative or summative purposes, many summative assessments are unsuitable for formative purposes because they do not provide useful feedback. For example, standardized-test scores may not be available to teachers for months after their students take the test (so the results cannot be used to modify lessons or teaching and better prepare students), or the assessments may not be specific or fine-grained enough to give teachers and students the detailed information they need to improve.

The following are a few representative examples of formative assessments:

- Questions that teachers pose to individual students and groups of students during the learning process to determine what specific concepts or skills they may be having trouble with. A wide variety of intentional questioning strategies may be employed, such as phrasing questions in specific ways to elicit more useful responses.

- Specific, detailed, and constructive feedback that teachers provide on student work , such as journal entries, essays, worksheets, research papers, projects, ungraded quizzes, lab results, or works of art, design, and performance. The feedback may be used to revise or improve a work product, for example.

- “Exit slips” or “exit tickets” that quickly collect student responses to a teacher’s questions at the end of a lesson or class period. Based on what the responses indicate, the teacher can then modify the next lesson to address concepts that students have failed to comprehend or skills they may be struggling with. “Admit slips” are a similar strategy used at the beginning of a class or lesson to determine what students have retained from previous learning experiences .

- Self-assessments that ask students to think about their own learning process, to reflect on what they do well or struggle with, and to articulate what they have learned or still need to learn to meet course expectations or learning standards.

- Peer assessments that allow students to use one another as learning resources. For example, “workshopping” a piece of writing with classmates is one common form of peer assessment, particularly if students follow a rubric or guidelines provided by a teacher.

In addition to the reasons addressed above, educators may also use formative assessment to:

- Refocus students on the learning process and its intrinsic value, rather than on grades or extrinsic rewards.

- Encourage students to build on their strengths rather than fixate or dwell on their deficits. (For a related discussion, see growth mindset .)

- Help students become more aware of their learning needs, strengths, and interests so they can take greater responsibility over their own educational growth. For example, students may learn how to self-assess their own progress and self-regulate their behaviors.

- Give students more detailed, precise, and useful information. Because grades and test scores only provide a general impression of academic achievement, usually at the completion of an instructional period, formative feedback can help to clarify and calibrate learning expectations for both students and parents. Students gain a clearer understanding of what is expected of them, and parents have more detailed information they can use to more effectively support their child’s education.

- Raise or accelerate the educational achievement of all students, while also reducing learning gaps and achievement gaps .

While the formative-assessment concept has only existed since the 1960s, educators have arguably been using “formative assessments” in various forms since the invention of teaching. As an intentional school-improvement strategy, however, formative assessment has received growing attention from educators and researchers in recent decades. In fact, it is now widely considered to be one of the more effective instructional strategies used by teachers, and there is a growing body of literature and academic research on the topic.

Schools are now more likely to encourage or require teachers to use formative-assessment strategies in the classroom, and there are a growing number of professional-development opportunities available to educators on the subject. Formative assessments are also integral components of personalized learning and other educational strategies designed to tailor lessons and instruction to the distinct learning needs and interests of individual students.

While there is relatively little disagreement in the education community about the utility of formative assessment, debates or disagreements may stem from differing interpretations of the term. For example, some educators believe the term is loosely applied to forms of assessment that are not “truly” formative, while others believe that formative assessment is rarely used appropriately or effectively in the classroom.

Another common debate is whether formative assessments can or should be graded. Many educators contend that formative assessments can only be considered truly formative when they are ungraded and used exclusively to improve student learning. If grades are assigned to a quiz, test, project, or other work product, the reasoning goes, they become de facto summative assessments—i.e., the act of assigning a grade turns the assessment into a performance evaluation that is documented in a student’s academic record, as opposed to a diagnostic strategy used to improve student understanding and preparation before they are given a graded test or assignment.

Some educators also make a distinction between “pure” formative assessments—those that are used on a daily basis by teachers while they are instructing students—and “interim” or “benchmark” assessments, which are typically periodic or quarterly assessments used to determine where students are in their learning progress or whether they are on track to meeting expected learning standards. While some educators may argue that any assessment method that is used diagnostically could be considered formative, including interim assessments, others contend that these two forms of assessment should remain distinct, given that different strategies, techniques, and professional development may be required.

Some proponents of formative assessment also suspect that testing companies mislabel and market some interim standardized tests as “formative” to capitalize on and profit from the popularity of the idea. Some observers express skepticism that commercial or prepackaged products can be authentically formative, arguing that formative assessment is a sophisticated instructional technique, and to do it well requires both a first-hand understanding of the students being assessed and sufficient training and professional development.

Alphabetical Search

14 Examples of Formative Assessment [+FAQs]

Traditional student assessment typically comes in the form of a test, pop quiz, or more thorough final exam. But as many teachers will tell you, these rarely tell the whole story or accurately determine just how well a student has learned a concept or lesson.

That’s why many teachers are utilizing formative assessments. While formative assessment is not necessarily a new tool, it is becoming increasingly popular amongst K-12 educators across all subject levels.

Curious? Read on to learn more about types of formative assessment and where you can access additional resources to help you incorporate this new evaluation style into your classroom.

What is Formative Assessment?

Online education glossary EdGlossary defines formative assessment as “a wide variety of methods that teachers use to conduct in-process evaluations of student comprehension, learning needs, and academic progress during a lesson, unit, or course.” They continue, “formative assessments help teachers identify concepts that students are struggling to understand, skills they are having difficulty acquiring, or learning standards they have not yet achieved so that adjustments can be made to lessons, instructional techniques, and academic support.”