An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Nutritional Status During Pregnancy and Lactation. Nutrition During Lactation. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1991.

Nutrition During Lactation.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

1 Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations

During the past decade, the benefits of breastfeeding have been emphasized by many authorities and organizations in the United States. Federal agencies have set specific objectives to increase the incidence and duration of breastfeeding (DHHS, 1980, 1990), and the Surgeon General has held workshops on breastfeeding and human lactation (DHHS, 1984, 1985). At the federal and state levels, the Special Supplemental Food Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) has produced materials designed to promote breastfeeding (e.g., Malone, 1980; USDA, 1988). Furthermore, the Office of Maternal and Child Health has sponsored breastfeeding projects (e.g., The Steering Committee to Promote Breastfeeding in New York City, 1986), as have state health departments and others. However, less attention has been given to two general topics: (1) the effects of breastfeeding on the nutritional status and long-term health of the mother and (2) the effects of the mother's nutritional status on the volume and composition of her milk and on the potential subsequent effects of those changes on infant health. The present report was designed to address these topics.

This summary briefly describes the origin of this effort and the process; provides key definitions; reviews what was learned about who is breastfeeding in the United States and if those women are well nourished; discusses nutritional influences on milk volume or composition; and describes how breastfeeding may affect infant growth, nutrition, and health, as well as maternal health. It then presents major conclusions, clinical recommendations, and the research recommendations most directly related to the nutrition of lactating women in the United States.

- Origin Of This Study

This study was undertaken at the request of the Maternal and Child Health Program (Title V, Social Security Act) of the Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In response to that request, the Food and Nutrition Board's Committee on Nutritional Status During Pregnancy and Lactation and its Subcommittee on Nutrition During Lactation were asked to evaluate current scientific evidence and formulate recommendations pertaining to the nutritional needs of lactating women, giving special attention to the needs of lactating adolescents; women over age 35; and women of black, Hispanic, or Southeast Asian origin. Part of this task included consideration of the effects of maternal dietary intake and nutritional status on the volume and composition of human milk, the appropriateness of various anthropometric methods for assessing nutritional status during lactation, and the effects of lactation both on maternal and infant health and on the nutritional status of both the mother and the infant.

- Approach To The Study

The study was limited to consideration of healthy U.S. women and their healthy, full-term infants. The Subcommittee on Nutrition During Lactation conducted an extensive literature review, consulted with a variety of experts, and met as a group seven times to discuss the data and draw conclusions from them. The Committee on Nutritional Status During Pregnancy and Lactation (the advisory committee) reviewed and commented on the work of the subcommittee and helped establish appropriate linkages between this report and the reports on weight gain and nutrient supplements during pregnancy contained in Nutrition During Pregnancy —a report prepared by two other subcommittees of this advisory committee (IOM, 1990). Compared with earlier reports from the National Research Council, Nutrition During Pregnancy recommended a higher range of weight gain (11.5 to 16 kg, or 25 to 35 lb, for women of normal prepregnancy weight for height). In addition, it advised routine low-dose iron supplementation during pregnancy, but supplements of other vitamins or minerals were recommended only under special circumstances.

In examining the nutritional needs of lactating women, priority was given to energy and to those nutrients believed to be consumed in amounts lower than Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) by many women in the United States. These nutrients include calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc, folate, and vitamin B 6 . Careful attention was given to the effects of lactation on various indicators of nutritional status, such as measurements of levels of biochemical compounds; functions related to specific nutrients; nutrient levels in specific body compartments; and height, weight, or other indicators of body size or adiposity. The subcommittee took into consideration that weight gain recommendations for pregnant women have been raised (see Nutrition During Pregnancy [IOM, 1990]) and that average weight gains of U.S. women during pregnancy have risen over the past two decades.

When possible, a distinction was made between exclusive breastfeeding, defined as the consumption of human milk as the sole source of energy, and partial breastfeeding, defined as the consumption of human milk in combination with formula or other foods, or both.

The nutritional demands imposed by lactation were estimated from data on volume and composition of milk produced by healthy, successfully lactating women, as done in Recommended Dietary Allowances (NRC, 1989). When it was feasible, evidence relating to possible depletion of maternal stores or to a decrease in the specific nutrient content of milk resulting from low maternal intake of the nutrient was also addressed. Because of the complex relationships between the nutrition of the mother and infant, the subcommittee examined the nutrition and growth of the breastfed infant.

The terms maternal health and infant health were interpreted in a broad sense. Consideration was given to both beneficial and adverse consequences for the health of the mother and her offspring, both during lactation and long after breastfeeding has been discontinued. For the mother, there was a search for evidence of differences in outcome related to whether or not she had breastfed. For the infant, evidence was sought for differences in outcome related to the method of feeding (breast compared with bottle). The possible influences of breastfeeding on prevention or promotion of chronic disease were addressed.

To the extent possible, this report includes detailed coverage of published evidence linking maternal nutrition, breastfeeding, and maternal and infant health. Because breastfeeding is encouraged primarily as a method for promoting the health of infants, considerable attention is also directed toward infant health even when there is no established relationship to maternal nutritional status. Recognizing the serious gaps in knowledge of nutrition during lactation, the subcommittee gave much thought to establishing directions for research.

The members of the subcommittee realized that nutrition is not the sole determinant of successful breastfeeding. A network of overlapping social factors including access to maternal leave, instructions concerning breastfeeding, availability of prenatal care, the length of hospital stay following delivery, infant care in the workplace, and the public attitudes toward breastfeeding are important. Given the goals of this report, the subcommittee did not specifically address those factors, but it recognizes that they should be considered in depth by public health groups that are attempting to improve rates of breastfeeding in this and other countries.

- What Was Learned

Who Is Breastfeeding

The incidence and duration of breastfeeding changed markedly during the twentieth century—first declining, then rising, and, from the early 1980s, declining once again. Currently, women who choose to breastfeed tend to be well educated, older, and white. Data on the incidence and duration of breastfeeding in the United States are especially limited for mothers who are economically disadvantaged and for those who are members of ethnic minority groups. The best data for any minority groups are for black women. Their rates of breastfeeding are substantially lower than those for white women, but factors that distinguish breastfeeding from nonbreastfeeding women tend to be similar among black and white women. Social, cultural, economic, and psychological factors that influence infant feeding choices by adolescent mothers are not well understood. In the United States, where few employers provide paid maternity leave, return to work outside the home is associated with a shorter duration of breastfeeding, but little else is known about when mothers discontinue either exclusive or partial breastfeeding. Such data are needed to estimate the total nutrient demands of lactation.

How Can It Be Determined Whether Lactating Women Are Well Nourished

The few lactating women who have been studied in the United States have been characterized as well nourished, but this observation cannot be generalized since these subjects were principally white women with some college education. Women from less advantaged, less well studied populations may be at higher risk of nutritional problems but tend not to breastfeed.

To determine whether women are adequately nourished, investigators use biochemical or anthropometric methods, or both. For lactating women, however, there are serious gaps and limitations in the data collected with these methods. Consequently, there is no scientific basis for determining whether poor nutritional status is a problem among certain groups of these women. To identify the nutrients likely to be consumed in inadequate amounts by lactating women, the subcommittee used an approach involving nutrient densities (nutrient intakes per 1,000 kcal) calculated from typical diets of nonlactating U.S. women. That is, they made the assumption that the average nutrient densities of the diets of lactating women would be the same as those of nonlactating women but that lactating women would have higher total energy intake (and therefore higher nutrient intake). Using this approach, the nutrients most likely to be consumed in amounts lower than the RDAs for lactating women are calcium, zinc, magnesium, vitamin B 6 , and folate.

Data for U.S. women indicate that successful lactation occurs regardless of whether a woman is thin, of normal weight, or obese. Anthropometric measurements (such as weight, weight for height, and skinfold thickness) have not been useful for predicting the success of lactation among the few U.S. women who have been studied. The predictive ability is not known for anthropometric measurements that fall outside the ranges observed in these limited samples.

Lactating women eating self-selected diets typically lose weight at the rate of 0.5 to 1.0 kg (˜1 to 2 lb) per month in the first 4 to 6 months of lactation. Such weight loss is probably physiologic. During the same period, values for subscapular and suprailiac skinfold thickness also decrease; triceps skinfold thickness does not. Not all women lose weight during lactation; studies suggest that approximately 20% may maintain or gain weight.

Biochemical data for lactating women have been obtained only from small, select samples. Such data are of limited use in the clinical situation because there are no norms for lactating women, and the norms for nonpregnant, nonlactating women may not be applicable to breastfeeding women. For example, there appear to be changes in plasma volume post partum, and there are changes in blood nutrient values over the course of lactation that are unrelated to changes in plasma volume.

Does Maternal Nutritional Status or Dietary Intake Influence Milk Volume

The mean volume of milk secreted by healthy U.S. women whose infants are exclusively breastfed during the first 4 to 6 months is approximately 750 to 800 ml/day, but there is considerable variability from woman to woman and in the same woman at different times. The standard deviation of daily milk intake by infants is about 165 ml; thus, 5% of women secrete less than 550 ml or more than 1,200 ml on a given day. The major determinant of milk production is the infant's demand for milk, which in turn may be influenced by the size, age, health, and other characteristics of the infant as well as by his or her intake of supplemental foods. The potential for milk production may be considerably higher than that actually produced, as evidenced by findings that the milk volumes produced by women nursing twins or triplets are much higher than those produced by women nursing a single infant.

Studies of healthy women in industrialized countries demonstrate that milk volume is not related to maternal weight or height or indices of fatness. In developing countries, there is conflicting evidence about whether thin women produce less milk than do women with higher weight for height.

Increased maternal energy intake has not been linked with increased milk production, at least among well-nourished women in industrialized countries. Nutritional supplementation of lactating women in developing countries where undernutrition may be a problem has generally been reported to have little or no impact on milk volume, but most studies have been too small to test the hypothesis adequately and lacked the design needed for causal inference. Studies of animals indicate that there may be a threshold below which energy intake is insufficient to support normal milk production, but it is likely that most studies in humans have been conducted on women with intakes well above this postulated threshold.

The weight loss ordinarily experienced by lactating women has no apparent deleterious effects on milk production. Although lactating women typically lose 0.5 to 1 kg (˜1 to 2 lb) per month, some women lose as much as 2 kg (˜4 lb) per month and successfully maintain milk volume. Regular exercise appears to be compatible with production of an adequate volume of milk.

The influence of maternal intake of specific nutrients on milk volume has not been investigated satisfactorily. Early studies in developing countries suggest a positive association of protein intake with milk volume, but those studies remain inconclusive. Fluids consumed in excess of thirst do not increase milk volume.

Does Maternal Nutritional Status Influence Milk Composition

The composition of human milk is distinct from the milk of other mammals and from infant formulas ordinarily derived from them. Human milk is unique in its physical structure, types and concentrations of macronutrients (protein, fat, and carbohydrate), micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), enzymes, hormones, growth factors, host resistance factors, inducers/modulators of the immune system, and anti-inflammatory agents.

A number of generalizations can be made about the effects of maternal nutrition on the composition of milk (see also Table 1-1 ):

Possible Influences of Maternal Intake on the Nutrient Composition of Human Milk and Nutrients for Which Clinical Deficiency Is Recognizable in Infants.

- Even if the usual dietary intake of a macronutrient is less than that recommended in Recommended Dietary Allowances (NRC, 1989), there will be little or no effect on the total amount of that nutrient in the milk. However, the proportions of the different fatty acids in human milk vary with maternal dietary intake.

- The concentrations of major minerals (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, sodium, and potassium) in human milk are not affected by the diet. Maternal intakes of selenium and iodine are positively related to their concentrations in human milk, but there is no convincing evidence that the concentrations of other trace elements in human milk are affected by maternal diet.

- The vitamin content of human milk is dependent upon the mother's current vitamin intake and her vitamin stores, but the strength of the relationships varies with the vitamin. Chronically low maternal intake of vitamins may result in milk that contains low amounts of these essential nutrients.

- The content of at least some nutrients in human milk may be maintained at a satisfactory level at the expense of maternal stores. This applies particularly to folate and calcium.

- Increasing the mother's intake of a nutrient to levels above the RDA ordinarily does not result in unusually high levels of the nutrient in her milk; vitamins B 6 and D, iodine, and selenium are exceptions. Studies have not been conducted to evaluate the possibility that high levels of nutrients in milk are toxic to the infant.

- Some studies suggest that poor maternal nutrition is associated with decreased concentrations of certain host resistance factors in human milk, whereas other studies do not suggest this association.

In What Ways May Breastfeeding Affect Infant Growth and Health

Infant nutrition.

Several factors influence the nutritional status of the breastfed infant: the infant's nutrient stores (which are largely determined by the length of gestation and maternal nutrition during pregnancy), the total amount of nutrients supplied by human milk (which is influenced by the extent and duration of breastfeeding), and certain genetic and environmental factors that affect the way nutrients are absorbed and used.

Human milk is ordinarily a complete source of nutrients for the exclusively breastfed infant. However, if the infant or mother is not exposed regularly to sunlight or if the mother's intake of vitamin D is low, breastfed infants may be at risk of vitamin D deficiency. Breastfed infants are susceptible to deficiency of vitamin B 12 if the mother is a complete vegetarian—even when the mother has no symptoms of that vitamin deficiency.

The risk of hemorrhagic disease of the newborn is relatively low. Nonetheless, all infants (regardless of feeding mode or of maternal nutritional status) are at some risk for this serious disease unless they are supplemented with a single dose of vitamin K at birth.

Full-term, exclusively breastfed infants ordinarily maintain a normal iron status for their first 6 months of life, regardless of maternal iron intake. Providing solid foods may reduce the percentage of iron absorbed by the partially breastfed infant, making it important in such cases to ensure that adequate iron is provided in the diet.

Growth and Development

Breastfed infants gain weight at about the same rate as formula-fed infants during the first 2 to 3 months post partum, although breastfed infants usually ingest less milk and thus have a lower energy intake. After the first few months post partum, healthy breastfed infants gain weight more slowly than those who are formula fed. In general, this pattern is not altered by the introduction of solid foods. Differences in linear growth between breastfed and formula-fed infants are small if statistical techniques are used to control differences in size at birth.

Infant Morbidity and Mortality

Several types of health problems occur less often or appear to have less serious consequences in breastfed than in formula-fed infants. These include certain infectious diseases (especially ones involving the intestinal and respiratory tracts), food allergies, and, perhaps, certain chronic diseases. There is suggestive evidence that severe maternal malnutrition might reduce the degree of immune protection afforded by human milk, but further studies will be required to address that issue.

Few infectious agents are commonly transmitted to the infant via human milk. The most prominent ones are cytomegalovirus in all populations that have been studied and human T lymphocytotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) in certain Asian populations. The transmission of cytomegalovirus by breastfeeding does not result in disease; the consequences of the transmission of HTLV-1 by breastfeeding are unknown. There are some case reports that indicate that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can be transmitted by breastfeeding as a result of the transfusion of HIV-contaminated blood during the immediate postpartum period. The likelihood of transmitting HIV via breastfeeding by women who tested seropositive for the agent during pregnancy has not been determined. Public policy on this issue has ranged from the Centers for Disease Control's recommendation not to breastfeed under these circumstances to the World Health Organization's encouragement to breastfeed, especially among women in developing countries.

In developing countries, mortality rates are lower among breastfed infants than among those who are formula fed. It is not known whether this advantage also holds in industrialized countries, in which death rates are lower in general. It is reasonable to believe that breastfeeding will lead to lower mortality among disadvantaged groups in industrialized countries if they have higher than usual infant and child mortality rates, but this issue has not been studied.

Medications, Drugs, and Environmental Contaminants

The few prescription drugs that are contraindicated during lactation because of potential harm to the infant can usually be avoided and replaced with safer acceptable ones. For example, there are a number of safe and effective substitutes for the antibiotic chloramphenicol, which is contraindicated for lactating women. If treatment with antimetabolites or radiotherapeutics is required by the mother, breastfeeding is contraindicated.

Cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption by lactating women in excess of 0.5 g/kg of maternal weight may be harmful to the infant, partly because of potential reduction in milk volume. Furthermore, a single report (Little et al., 1989) associates heavy alcohol use by the mother with retarded psychomotor development of the infant at 1 year of age. Infrequent cigarette smoking, occasional consumption of small amounts of alcohol, and moderate ingestion of caffeine-containing products are not considered to be contraindicated during breastfeeding. Use of illicit drugs is contraindicated because of the potential for drug transfer through the milk as well as hazards to the mother. Since the limited information on the impact of these habits upon the nutrition of women in the childbearing years is reviewed in Nutrition During Pregnancy (IOM, 1990), they were not considered further by this subcommittee.

In the uncommon situation of a high risk of exposure to such environmental contaminants as organochlorinated compounds (such as dichlorodiphenyl-trichloroethane [DDT] or polychlorinated biphenyls [PCBs]) or toxic metals (such as mercury), risks must be weighed against the benefits of breastfeeding for both mother and infant on a case-by-case basis. In areas of unusually high exposure, levels of the contaminant should be measured in the mother's blood and milk.

How Does Breastfeeding Affect Maternal Nutrition and Health

Breastfeeding substantially increases the mother's requirements for most nutrients. The magnitude of the total increase is most strongly affected by the extent and duration of lactation. Adequacy of intakes of calcium, magnesium, zinc, folate, and vitamin B 6 merits special attention since average intakes may be below those recommended. The net long-term effect of lactation on bone mass is uncertain. Some data associate lactation with short-term bone loss, whereas most recent studies suggest a protective long-term effect. Those data are provocative but of such preliminary nature that no definitive conclusions may be drawn from them.

Although most lactating women lose weight gradually during lactation, some do not. The influence of lactation on long-term postpartum weight retention and maternal risk of adult-onset obesity has not been determined.

A well-documented effect of lactation is delayed return to ovulation. In addition, some recent epidemiologic evidence indicates that breastfeeding may lessen the risk that the mother will develop breast cancer, but the data are not consistent across all studies.

- Conclusions And Recommendations

The major conclusions of the report are as follows.

Women living under a wide variety of circumstances in the United States and elsewhere are capable of fully nourishing their infants by breastfeeding them. Throughout its deliberations, the subcommittee was impressed by evidence that mothers are able to produce milk of sufficient quantity and quality to support growth and promote the health of infants—even when the mother's supply of nutrients and energy is limited. With few exceptions (identified later in the summary under "Infant Growth and Nutrition"), the full-term exclusively breastfed infant will be well nourished during the first 4 to 6 months after birth.

In contrast, the lactating woman is vulnerable to depletion of nutrient stores through her milk. Measures should be taken to promote food intake during lactation that will prevent net maternal losses of nutrients, especially of calcium, magnesium, zinc, folate, and vitamin B 6 .

Breastfeeding is recommended for all infants in the United States under ordinary circumstances. Exclusive breastfeeding is the preferred method of feeding for normal full-term infants from birth to age 4 to 6 months. Breastfeeding complemented by the appropriate introduction of other foods is recommended for the remainder of the first year, or longer if desired. The subcommittee and advisory committee recognize that it is difficult for some women to follow these recommendations for social or occupational reasons. In these situations, appropriate formula feeding is an acceptable alternative.

Data are lacking for use in developing strategies to identify lactating women who are at risk of depleting their own nutrient stores. Although nutrient intake appears adequate for the small number of lactating women who have been studied in the United States, evidence from U.S. surveys of nonpregnant, nonlactating women suggests that usual dietary intake of certain nutrients by disadvantaged women is likely to be somewhat lower than that by women of higher socioeconomic status. Thus, if breastfeeding rates increase among less advantaged women as a result of efforts to promote breastfeeding, it will be important to examine more completely the nutrient intake of these women during lactation.

If lactating women follow eating patterns similar to those of the average U.S. woman in sufficient quantity to meet their energy requirements, they are likely to meet the recommended intakes of all nutrients except perhaps calcium and zinc. However, if they curb their energy intakes, their intakes of several nutrients are likely to be less than the RDA.

Recommendations for Women Who Wish To Breastfeed and for Their Care Providers

Because of serious gaps in information about nutrition assessment and nutrient requirements during lactation and about effects of maternal nutrition on the wide array of components in the milk, the following recommendations should be considered preliminary. Although they reflect the best judgment of the subcommittee and advisory committee, these recommendations are open to reconsideration as the knowledge base grows.

Diet and Vitamin-Mineral Supplementation

Lactating women should be encouraged to obtain their nutrients from a well-balanced, varied diet rather than from vitamin-mineral supplements.

- Provide women who plan to breastfeed or who are already doing so with nutrition information that is culturally appropriate (that is, information that is sensitive to the foodways, eating practices, and health beliefs and attitudes of the cultural group). To facilitate the acquisition of this information, health care providers are encouraged to make effective use of teaching opportunities during prenatal visits, hospitalization following delivery, and routine postpartum visits for maternal or pediatric care.

- Encourage lactating women to follow dietary guidelines that promote a generous intake of nutrients from fruits and vegetables, whole-grain breads and cereals, calcium-rich dairy products, and protein-rich foods such as meats, fish, and legumes. Such a diet would ordinarily supply a sufficient quantity of essential nutrients. The individual recommendations should be compatible with the woman's economic situation and food preferences. The evidence does not warrant routine vitamin-mineral supplementation of lactating women.

- If dietary evaluation suggests that the diet does not provide the recommended amounts of one or more nutrients, encourage the woman to select and consume foods that are rich in those nutrients.

- For women whose eating patterns lead to a very low intake of one or more nutrients, provide individualized diet counseling (preferred) or recommend nutrient supplementation (as described in Table 1-2 ).

- Encourage sufficient intake of fluids—especially water, juice, and milk—to alleviate natural thirst. It is not necessary to encourage fluid intakes above this level.

- The elimination of major nutrient sources (e.g., all dairy products) from the maternal diet to treat allergy or colic in the breastfed infant is not recommended unless there is evidence from oral elimination-challenge studies to determine whether the mother is sensitive or intolerant to the food or that the breastfed infant reacts to the foods ingested by the mother. If a key nutrient source is eliminated from the maternal diet, the mother should be counseled on how to achieve adequate nutrient intake by substituting other foods.

Suggested Measures for Improving Nutrient Intake of Women with Restrictive Eating Patterns.

A Defined Health Care Plan for Lactating Women

There should be a well-defined plan for the health care of the lactating woman that includes screening for nutritional problems and providing dietary guidance. Since preparation for lactation should begin during the prenatal period, the physician, midwife, nutritionist, or other member of the obstetric team should introduce general information about nutrition during lactation and should screen for possible problems related to nutrition. Ideally, more extensive evaluation and counseling should take place during hospitalization for childbirth. If that is precluded by the brevity of the hospital stay, an early visit to an appropriate health care professional by the mother or a visit to the mother's home is advisable.

To implement routine screening economically and practically, the subcommittee considers it sufficient to continue the practice of weighing women (using standard procedures as described in Nutrition During Pregnancy [IOM, 1990]) at scheduled visits and to ask a few simple questions to determine the following:

- Are calcium-rich foods eaten regularly?

- Does the diet include vitamin D-fortified milk or cereal or is there adequate exposure to ultraviolet light?

- Are fruits and vegetables eaten regularly?

- Is the mother a complete vegetarian?

- Is the mother restricting her food intake severely in an attempt to lose weight or to treat certain medical conditions?

- Are there life circumstances (e.g., poverty, or abuse of drugs or alcohol) that might interfere with an adequate diet?

It is not necessary to obtain measurements of skinfold thickness or to conduct laboratory tests as a part of the routine assessment of the nutritional status of lactating women.

The subcommittee recognizes that establishing standard health care procedures for lactating women requires expanded training of health care providers. Activities to achieve this expanded training are being initiated by the Surgeon General's workshop committee comprising representatives from the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and other professional organizations.

Breastfeeding Practices

Efforts to support lactation must consider breastfeeding practices.

- Because the early management of lactation has a strong influence on the establishment of an adequate milk supply, breastfeeding guidance should be provided prenatally and continued in the hospital after delivery and during the early postpartum period.

- All hospitals providing obstetric care should provide knowledgeable staff in the immediate postpartum period who have responsibility for providing support and guidance in initiating breastfeeding and measures to promote establishment of an ample supply of milk.

- Breastfeeding practices that are responsive to the infant's natural appetite should be promoted. In the first few weeks, infants should nurse at least 8 times per day, and some may nurse as often as 15 or more times per day. After the first month, infants fed on demand usually nurse 5 to 12 times per day.

Maternal Weight

Women who plan to breastfeed or who are breastfeeding should be given realistic, health-promoting advice about weight change during lactation.

- Advise women that it is normal to lose weight during the first 6 months of lactation. The average rate of weight loss is 0.5 to 1.0 kg (˜ 1 to 2 lb)/month after the first month post partum. However, not all women who breastfeed lose weight; some women gain weight post partum, whether or not they breastfeed. If a lactating woman is overweight, a weight loss of up to 2 kg (˜4.5 lb) per month is unlikely to adversely affect milk volume, but such women should be alert for any indications that the infant's appetite is not being satisfied. Rapid weight loss (>2 kg/month after the first month post partum) is not advisable for breastfeeding women.

- Advise women who choose to curb their energy intake to pay special attention to eating a balanced, varied diet and to including foods rich in calcium, zinc, magnesium, vitamin B 6 , and folate. Encourage energy intake of at least 1,800 kcal/day. Calcium, multivitamin-mineral supplements, or both may be advised when dietary sources are marginal and it is unlikely that appropriate dietary practices will or can be followed. Intakes below 1,500 kcal/day are not recommended at any time during lactation, although fasts lasting less than 1 day have not been shown to decrease milk volume. Liquid diets and weight loss medications are not recommended. Since the impact of curtailing maternal energy intake during the first 2 to 3 weeks post partum is unknown, dieting during this period is not recommended.

Maternal Substance Use and Abuse

The use of illicit drugs should be actively discouraged, and affected women (regardless of their mode of feeding) should be assisted to enter a rehabilitative program that makes provision for the infant. The use of certain legal substances by lactating women is also of concern, including the potential for alcohol abuse.

- There is no scientific evidence that consumption of alcoholic beverages has a beneficial impact on any aspect of lactation performance. If alcohol is used, advise the lactating woman to limit her intake to no more than 0.5 g of alcohol per kg of maternal body weight per day. Intake over this level may impair the milk ejection reflex. For a 60-kg (132-lb) woman, 0.5 g of alcohol per kg of body weight corresponds to approximately 2 to 2.5 oz of liquor, 8 oz of table wine, or 2 cans of beer.

- Actively discourage smoking among lactating women, not only because it may reduce milk volume but because of its other harmful effects on the mother and her infant.

- Discourage intake of large quantities of coffee, other caffeine-containing beverages and medications, and decaffeinated coffee. The equivalent of 1 to 2 cups of regular coffee daily is unlikely to have a deleterious effect on the nursling, although preliminary evidence suggests that maternal coffee intake may adversely influence the iron content of milk and the iron status of the infant.

Infant Growth and Nutrition

The subcommittee recommends that health care providers be informed about the differences in growth between healthy breastfed and formula-fed infants. On average, breastfed infants gain weight more slowly than those fed formula after the first 2 to 3 months. Slower weight gain, by itself, does not justify the use of supplemental formula. When in doubt, clinicians should evaluate adequacy of growth according to the guidelines described by Lawrence (1989).

Regardless of what the mother eats, the following steps should be taken to ensure adequate nutrition of breastfed infants.

- All newborns should receive a 0.5- to 1.0-mg injection or a 1.0-to 2.0-mg oral dose of vitamin K immediately after birth regardless of the type of feeding that will be offered the infant.

- If the infant's exposure to sunlight appears to be inadequate, the infant should be given a 5- to 7.5-µg supplement of vitamin D per day.

- Fluoride supplements should be provided to breastfed infants if the fluoride content of the household drinking-water supply is low (<0.3 ppm)

- When breastfeeding is complemented by other foods, and by 6 months of age in any case, the infant should be given food rich in bioavailable iron or a daily low-dose oral iron supplement.

Infant Health

Health care providers should recognize that breastfeeding is recommended to reduce the incidence and severity of certain infectious gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases and other disorders in infancy. Breastfeeding ordinarily confers health benefits to the infant, but in certain rare cases it may pose some health risks, as indicated below.

- For mothers requiring medication and desiring to breastfeed, the clinician should select the medication least likely to pass into the milk and to the infant.

- Although medications rarely pose a problem during lactation, breastfeeding is contraindicated in the case of a few. Such drugs include antineoplastic agents, therapeutic radiopharmaceuticals, some but not all antithyroid agents, and antiprotozoan agents.

- In those rare cases when there is heavy exposure to pesticides, heavy metals, or other contaminants that may pass into the milk, breastfeeding is not recommended if maternal levels are high.

Recommendations for Nutrition Monitoring

The committee recommends that the U.S. government provide a mechanism for periodically monitoring trends in lactation and developing normative indicators of nutritional status during lactation.

- Monitoring of trends . Data are needed on the incidence and duration of breastfeeding among the population as a whole, and among some particularly vulnerable subpopulations. Exclusive, partial, and minimal breastfeeding should be distinguished; and data should be collected at several ages during infancy. Current or planned surveys by such agencies as the National Center for Health Statistics or the Nutrition Monitoring Division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture could be modified to serve these goals.

- Developing normative indicators of nutritional status . There is a need for data on dietary intakes by, and nutritional status among, lactating women and their relationship to lactation performance. Identification of groups of lactating women who are at nutritional risk is a problem of public health importance.

Research Recommendations

In its deliberations, the subcommittee was well aware that many factors (such as hospital practices, social attitudes, governmental policies, and exposure to infectious agents) may have a great influence on breastfeeding rates and lactation performance and that there is a need for studies to examine approaches that hold the most promise for improving both of these. Similarly, the subcommittee recognized the great need for studies to examine the short- and long-term benefits of breastfeeding in the United States among mothers and infants in all segments of the population, but especially among disadvantaged groups, which currently have the lowest rates of breastfeeding. Research recommendations concerning several of these issues (infant mortality, growth charts for breastfed infants, possible transmission of HIV, indicators of infant nutritional status) are contained in Chapter 10 . They have been excluded from this summary, not because they are unimportant, but rather because they relate only indirectly to the nutrition of healthy U.S. women during lactation.

- Research is needed to develop indicators of nutritional status for lactating women. First, the identification of normative values for nutritional status should be based on observations of representative, healthy, lactating women in the United States. In addition, indicators are needed of both (1) risks of adverse outcomes related to the mother's dietary intake and (2) the potential of the mother or her nursing infant to benefit from interventions designed to improve their nutritional status or health.

- Research is needed to identify groups of lactating women in the United States who are at nutritional risk or who could benefit from nutrition intervention programs. In general, it has been difficult to identify groups of mothers and infants in the United States with nutritional deficits that are severe enough to have measurable functional consequences. Priority should be given to the study of lactating women in subpopulations believed to be at risk of inadequate intake of certain nutrients, such as calcium by blacks and vitamin A by low-income women. The potential influence of culture-specific food beliefs on nutrient intake of lactating women should be included in any such investigations.

- Intervention studies of improved design and technical sophistication are needed to investigate the effects of maternal diet and nutritional status on milk volume; milk composition; infant nutritional status, growth, and health; and maternal health. The nursing dyad (the mother and her infant) has seldom been the focus of studies. Thus, a key aspect of this recommendation is concurrent examination of the mother, the volume and composition of the milk, and the infant. The design of such research needs to be adequate for causal inference; thus, if possible, it should include random assignment of lactating subjects to treatment groups. Appropriate sampling and handling of milk for the valid assessment of energy density, nutrient concentration, and total milk volume are essential, as is accurate measurement of nutrient concentrations.

With regard to the energy balance of lactating women, the threshold below which energy intake is insufficient to support adequate milk production has not yet been identified. Resolution of this question will probably require supplementation studies of women in developing countries whose diets are chronically energy deficient. Although such deficient diets are not common in the United States, identification of the level of energy intake that is too low to support lactation will be useful in establishing guidelines for women who want to breastfeed but who also want to restrict their energy intake to lose weight. Although chronically low energy intakes by women in disadvantaged populations may not be completely analogous to acute energy restriction among otherwise well-nourished women, ethical considerations limit the kinds of investigations that could directly address the influence of energy restriction. In supplementation studies, measurements should be made of lactation performance and of any impact on the mother's nutritional status and health, including the period of lactation amenorrhea.

With regard to specific nutrients, the impact of relatively low intakes of folate, vitamin B 6 , calcium, zinc, and magnesium during lactation on the mother's nutritional status and health needs to be assessed in more detail. As a part of this assessment, studies of the absorption of calcium, zinc, and magnesium during lactation will be useful. There is also a need to identify a reliable indicator of vitamin B 6 status of infants and to document the relationships between this indicator, maternal vitamin B 6 intake, and vitamin B 6 content in milk. Finally, resolution of the conflicting findings concerning the impact of maternal protein intake on milk volume would be desirable.

- DHHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 1980. Promoting Health/Preventing Disease: Objectives for the Nation . Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 102 pp.

- DHHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 1984. Report of the Surgeon General's Workshop on Breastfeeding and Human Lactation . DHHS Publ. No. HRS-D-MC 84-2. Health Resources and Services Administration, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, Md. 93 pp.

- DHHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 1985. Followup Report: The Surgeon General's Workshop on Breastfeeding & Human Lactation . DHHS Publ. No. HRS-D-MC 85-2. Health Resources and Services Administration, Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, Md. 46 pp.

- DHHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 1990. Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives. Conference Edition . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health, Washington, D.C. 672 pp.

- IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1990. Nutrition During Pregnancy: Weight Gain and Nutrient Supplements . Report of the Subcommittee on Nutritional Status and Weight Gain During Pregnancy, Subcommittee on Dietary Intake and Nutrient Supplements During Pregnancy, Committee on Nutritional Status During Pregnancy and Lactation, Food and Nutrition Board. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C. 468 pp.

- Lawrence, R.A. 1989. Breastfeeding: A Guide for the Medical Profession , 3rd ed. C.V. Mosby, St. Louis. 652 pp.

- Little, R.E., K.W. Anderson, C.H. Ervin, B. Worthington-Roberts, and S.K. Clarren. 1989. Maternal alcohol use during breastfeeding and infant mental and motor development at one year . N. Engl. J. Med. 321:425-430. [ PubMed : 2761576 ]

- Malone, C. 1980. Breast-Feeding. Cumberland County WIC Program, People's Regional Opportunity Program, Portland, Maine . 13 pp.

- NRC (National Research Council). 1989. Recommended Dietary Allowances , 10 th ed. Report of the Subcommittee on the Tenth Edition of the RDAs, Food and Nutrition Board, Commission on Life Sciences. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C. 284 pp.

- The Steering Committee to Promote Breastfeeding in New York City. 1986. The Art and Science of Breastfeeding . Division of Maternal and Child Health, Bureau of Health Care Delivery and Assistance, Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C. 74 pp.

- USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture). 1988. Promoting Breastfeeding in WIC: A Compendium of Practical Approaches . FNS-256. Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Alexandria, Va. 171 pp.

- Cite this Page Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Nutritional Status During Pregnancy and Lactation. Nutrition During Lactation. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1991. 1, Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations.

- PDF version of this title (3.5M)

- Disable Glossary Links

In this Page

Related information.

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations - Nutrition During Lactation Summary, Conclusions, and Recommendations - Nutrition During Lactation

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Open access

- Published: 26 November 2021

Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of Breastfeeding: a scoping review of the literature

- Bridget Beggs 1 ,

- Liza Koshy 1 &

- Elena Neiterman 1

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 2169 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

22 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Despite public health efforts to promote breastfeeding, global rates of breastfeeding continue to trail behind the goals identified by the World Health Organization. While the literature exploring breastfeeding beliefs and practices is growing, it offers various and sometimes conflicting explanations regarding women’s attitudes towards and experiences of breastfeeding. This research explores existing empirical literature regarding women’s perceptions about and experiences with breastfeeding. The overall goal of this research is to identify what barriers mothers face when attempting to breastfeed and what supports they need to guide their breastfeeding choices.

This paper uses a scoping review methodology developed by Arksey and O’Malley. PubMed, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and PsychInfo databases were searched utilizing a predetermined string of keywords. After removing duplicates, papers published in 2010–2020 in English were screened for eligibility. A literature extraction tool and thematic analysis were used to code and analyze the data.

In total, 59 papers were included in the review. Thematic analysis showed that mothers tend to assume that breastfeeding will be easy and find it difficult to cope with breastfeeding challenges. A lack of partner support and social networks, as well as advice from health care professionals, play critical roles in women’s decision to breastfeed.

While breastfeeding mothers are generally aware of the benefits of breastfeeding, they experience barriers at individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels. It is important to acknowledge that breastfeeding is associated with challenges and provide adequate supports for mothers so that their experiences can be improved, and breastfeeding rates can reach those identified by the World Health Organization.

Peer Review reports

Public health efforts to educate parents about the importance of breastfeeding can be dated back to the early twentieth century [ 1 ]. The World Health Organization is aiming to have at least half of all the mothers worldwide exclusively breastfeeding their infants in the first 6 months of life by the year 2025 [ 2 ], but it is unlikely that this goal will be achieved. Only 38% of the global infant population is exclusively breastfed between 0 and 6 months of life [ 2 ], even though breastfeeding initiation rates have shown steady growth globally [ 3 ]. The literature suggests that while many mothers intend to breastfeed and even make an attempt at initiation, they do not always maintain exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life [ 4 , 5 ]. The literature identifies various barriers, including return to paid employment [ 6 , 7 ], lack of support from health care providers and significant others [ 8 , 9 ], and physical challenges [ 9 ] as potential factors that can explain premature cessation of breastfeeding.

From a public health perspective, the health benefits of breastfeeding are paramount for both mother and infant [ 10 , 11 ]. Globally, new mothers following breastfeeding recommendations could prevent 974,956 cases of childhood obesity, 27,069 cases of mortality from breast cancer, and 13,644 deaths from ovarian cancer per year [ 11 ]. Global economic loss due to cognitive deficiencies resulting from cessation of breastfeeding has been calculated to be approximately USD $285.39 billion dollars annually [ 11 ]. Evidently, increasing exclusive breastfeeding rates is an important task for improving population health outcomes. While public health campaigns targeting pregnant women and new mothers have been successful in promoting breastfeeding, they also have been perceived as too aggressive [ 12 ] and failing to consider various structural and personal barriers that may impact women’s ability to breastfeed [ 1 ]. In some cases, public health messaging itself has been identified as a barrier due to its rigid nature and its lack of flexibility in guidelines [ 13 ]. Hence, while the literature on women’s perceptions regarding breastfeeding and their experiences with breastfeeding has been growing [ 14 , 15 , 16 ], it offers various, and sometimes contradictory, explanations on how and why women initiate and maintain breastfeeding and what role public health messaging plays in women’s decision to breastfeed.

The complex array of the barriers shaping women’s experiences of breastfeeding can be broadly categorized utilizing the socioecological model, which suggests that individuals’ health is a result of the interplay between micro (individual), meso (institutional), and macro (social) factors [ 17 ]. Although previous studies have explored barriers and supports to breastfeeding, the majority of articles focus on specific geographic areas (e.g. United States or United Kingdom), workplaces, or communities. In addition, very few articles focus on the analysis of the interplay between various micro, meso, and macro-level factors in shaping women’s experiences of breastfeeding. Synthesizing the growing literature on the experiences of breastfeeding and the factors shaping these experiences, offers researchers and public health professionals an opportunity to examine how various personal and institutional factors shape mothers’ breastfeeding decision-making. This knowledge is needed to identify what can be done to improve breastfeeding rates and make breastfeeding a more positive and meaningful experience for new mothers.

The aim of this scoping review is to synthesize evidence gathered from empirical literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding. Specifically, the following questions are examined:

What does empirical literature report on women’s perceptions on breastfeeding?

What barriers do women face when they attempt to initiate or maintain breastfeeding?

What supports do women need in order to initiate and/or maintain breastfeeding?

Focusing on women’s experiences, this paper aims to contribute to our understanding of women’s decision-making and behaviours pertaining to breastfeeding. The overarching aim of this review is to translate these findings into actionable strategies that can streamline public health messaging and improve breastfeeding education and supports offered by health care providers working with new mothers.

This research utilized Arksey & O’Malley’s [ 18 ] framework to guide the scoping review process. The scoping review methodology was chosen to explore a breadth of literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding. A broad research question, “What does empirical literature tell us about women’s experiences of breastfeeding?” was set to guide the literature search process.

Search methods

The review was undertaken in five steps: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant literature, (3) iterative selection of data, (4) charting data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting results. The inclusion criteria were set to empirical articles published between 2010 and 2020 in peer-reviewed journals with a specific focus on women’s self-reported experiences of breastfeeding, as well as how others see women’s experiences of breastfeeding. The focus on women’s perceptions of breastfeeding was used to capture the papers that specifically addressed their experiences and the barriers that they may encounter while breastfeeding. Only articles written in English were included in the review. The keywords utilized in the search strategy were developed in collaboration with a librarian (Table 1 ). PubMed, CINAHL, Sociological Abstracts, and PsychInfo databases were searched for the empirical literature, yielding a total of 2885 results.

Search outcome

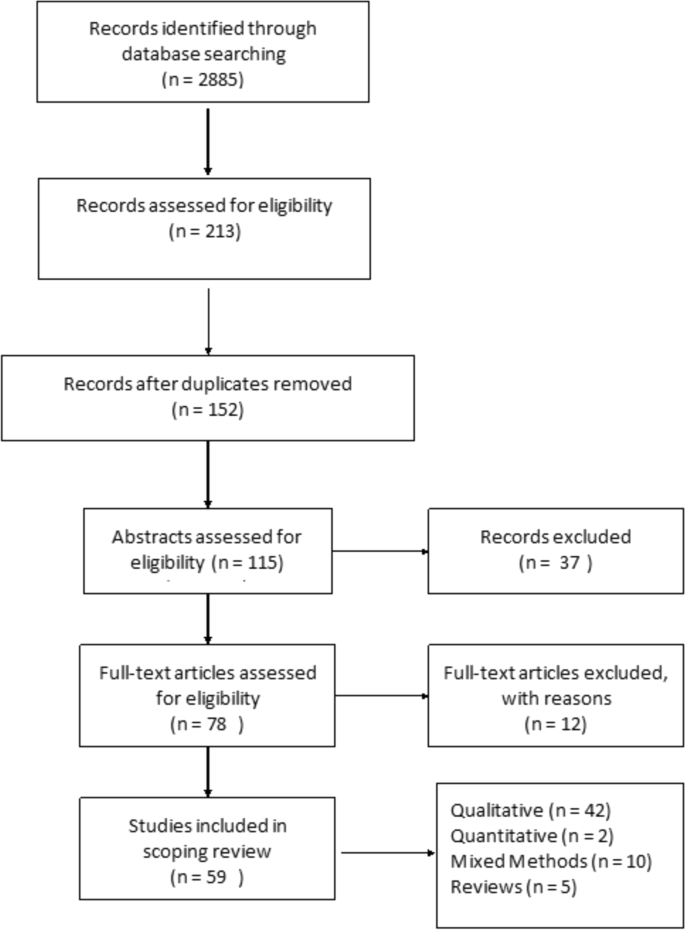

The articles deemed to fit the inclusion criteria ( n = 213) were imported into RefWorks, an online reference manager tool and further screened for eligibility (Fig. 1 ). After the removal of 61 duplicates and title/abstract screening, 152 articles were kept for full-text review. Two independent reviewers assessed the papers to evaluate if they met the inclusion criteria of having an explicit analytic focus on women’s experiences of breastfeeding.

Prisma Flow Diagram

Quality appraisal

Consistent with scoping review methodology [ 18 ], the quality of the papers included in the review was not assessed.

Data abstraction

A literature extraction tool was created in MS Excel 2016. The data extracted from each paper included: (a) authors names, (b) title of the paper, (c) year of publication, (d) study objectives, (e) method used, (f) participant demographics, (g) country where the study was conducted, and (h) key findings from the paper.

Thematic analysis was utilized to identify key topics covered by the literature. Two reviewers independently read five papers to inductively generate key themes. This process was repeated until the two reviewers reached a consensus on the coding scheme, which was subsequently applied to the remainder of the articles. Key themes were added to the literature extraction tool and each paper was assigned a key theme and sub-themes, if relevant. The themes derived from the analysis were reviewed once again by all three authors when all the papers were coded. In the results section below, the synthesized literature is summarized alongside the key themes identified during the analysis.

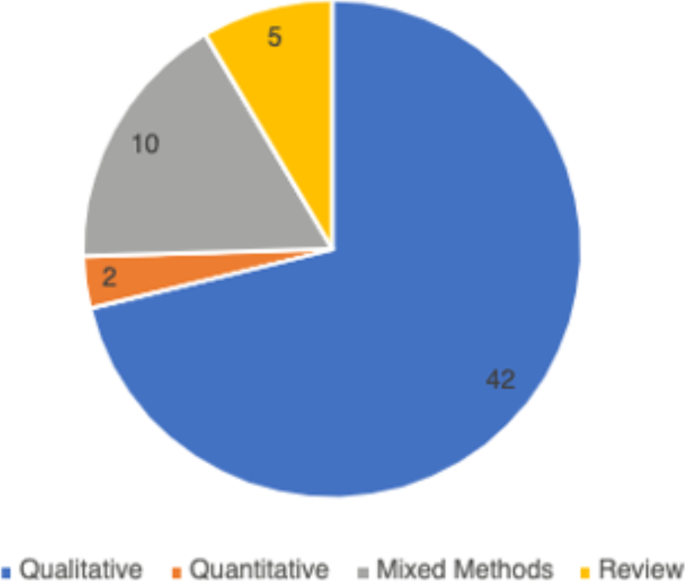

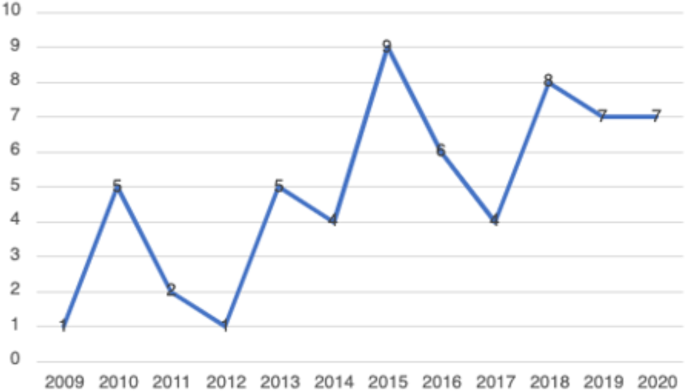

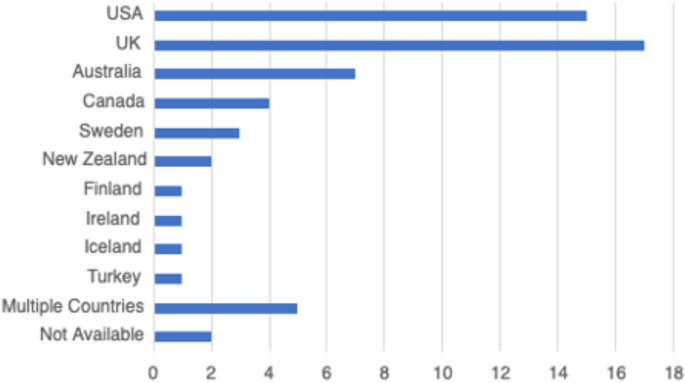

In total, 59 peer-reviewed articles were included in the review. Since the review focused on women’s experiences of breastfeeding, as would be expected based on the search criteria, the majority of articles ( n = 42) included in the sample were qualitative studies, with ten utilizing a mixed method approach (Fig. 2 ). Figure 3 summarizes the distribution of articles by year of publication and Fig. 4 summarizes the geographic location of the study.

Types of Articles

Years of Publication

Countries of Focus Examined in Literature Review

Perceptions about breastfeeding

Women’s perceptions about breastfeeding were covered in 83% ( n = 49) of the papers. Most articles ( n = 31) suggested that women perceived breastfeeding as a positive experience and believed that breastfeeding had many benefits [ 19 , 20 ]. The phrases “breast is best” and “breastmilk is best” were repeatedly used by the participants of studies included in the reviewed literature [ 21 ]. Breastfeeding was seen as improving the emotional bond between the mother and the child [ 20 , 22 , 23 ], strengthening the child’s immune system [ 24 , 25 ], and providing a booster to the mother’s sense of self [ 1 , 26 ]. Convenience of breastfeeding (e.g., its availability and low cost) [ 19 , 27 ] and the role of breastfeeding in weight loss during the postpartum period were mentioned in the literature as other factors that positively shape mothers’ perceptions about breastfeeding [ 28 , 29 ].

The literature suggested that women’s perceptions of breastfeeding and feeding choices were also shaped by the advice of healthcare providers [ 30 , 31 ]. Paradoxically, messages about the importance and relative simplicity of breastfeeding may also contribute to misalignment between women’s expectations and the actual experiences of breastfeeding [ 32 ]. For instance, studies published in Canada and Sweden reported that women expected breastfeeding to occur “naturally”, to be easy and enjoyable [ 23 ]. Consequently, some women felt unprepared for the challenges associated with initiation or maintenance of breastfeeding [ 31 , 33 ]. The literature pointed out that mothers may feel overwhelmed by the frequency of infant feedings [ 26 ] and the amount as well as intensity of physical difficulties associated with breastfeeding initiation [ 33 ]. Researchers suggested that since many women see breastfeeding as a sign of being a “good” mother, their inability to breastfeed may trigger feelings of personal failure [ 22 , 34 ].

Women’s personal experiences with and perceptions about breastfeeding were also influenced by the cultural pressure to breastfeed. Welsh mothers interviewed in the UK, for instance, revealed that they were faced with judgement and disapproval when people around them discovered they opted out of breastfeeding [ 35 ]. Women recalled the experiences of being questioned by others, including strangers, when they were bottle feeding their infants [ 9 , 35 , 36 ].

Barriers to breastfeeding

The vast majority ( n = 50) of the reviewed literature identified various barriers for successful breastfeeding. A sizeable proportion of literature (41%, n = 24) explored women’s experiences with the physical aspects of breastfeeding [ 23 , 33 ]. In particular, problems with latching and the pain associated with breastfeeding were commonly cited as barriers for women to initiate breastfeeding [ 23 , 28 , 37 ]. Inadequate milk supply, both actual and perceived, was mentioned as another barrier for initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding [ 33 , 37 ]. Breastfeeding mothers were sometimes unable to determine how much milk their infants consumed (as opposed to seeing how much milk the infant had when bottle feeding), which caused them to feel anxious and uncertain about scheduling infant feedings [ 28 , 37 ]. Women’s inability to overcome these barriers was linked by some researchers to low self-efficacy among mothers, as well as feeling overwhelmed or suffering from postpartum depression [ 38 , 39 ].

In addition to personal and physical challenges experienced by mothers who were planning to breastfeed, the literature also highlighted the importance of social environment as a potential barrier to breastfeeding. Mothers’ personal networks were identified as a key factor in shaping their breastfeeding behaviours in 43 (73%) articles included in this review. In a study published in the UK, lack of role models – mothers, other female relatives, and friends who breastfeed – was cited as one of the potential barriers for breastfeeding [ 36 ]. Some family members and friends also actively discouraged breastfeeding, while openly questioning the benefits of this practice over bottle feeding [ 1 , 17 , 40 ]. Breastfeeding during family gatherings or in the presence of others was also reported as a challenge for some women from ethnic minority groups in the United Kingdom and for Black women in the United States [ 41 , 42 ].

The literature reported occasional instances where breastfeeding-related decisions created conflict in women’s relationships with significant others [ 26 ]. Some women noted they were pressured by their loved one to cease breastfeeding [ 22 ], especially when women continued to breastfeed 6 months postpartum [ 43 ]. Overall, the literature suggested that partners play a central role in women’s breastfeeding practices [ 8 ], although there was no consistency in the reviewed papers regarding the partners’ expressed level of support for breastfeeding.

Knowledge, especially practical knowledge about breastfeeding, was mentioned as a barrier in 17% ( n = 10) of the papers included in this review. While health care providers were perceived as a primary source of information on breastfeeding, some studies reported that mothers felt the information provided was not useful and occasionally contained conflicting advice [ 1 , 17 ]. This finding was reported across various jurisdictions, including the United States, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Netherlands, where mothers reported they had no support at all from their health care providers which made it challenging to address breastfeeding problems [ 26 , 38 , 44 ].

Breastfeeding in public emerged as a key barrier from the reviewed literature and was cited in 56% ( n = 33) of the papers. Examining the experiences of breastfeeding mothers in the United States, Spencer, Wambach, & Domain [ 45 ] suggested that some participants reported feeling “erased” from conversations while breastfeeding in public, rendering their bodies symbolically invisible. Lack of designated public spaces for breastfeeding forced many women to alter their feeding in public and to retreat to a private or a more secluded space, such as one’s personal car [ 25 ]. The oversexualization of women’s breasts was repeatedly noted as a core reason for the United States women’s negative experiences and feelings of self-consciousness about breastfeeding in front of others [ 45 ]. Studies reported women’s accounts of feeling the disapproval or disgust of others when breastfeeding in public [ 46 , 47 ], and some reported that women opted out of breastfeeding in public because they did not want to make those around them feel uncomfortable [ 25 , 40 , 48 ].

Finally, return to paid employment was noted in the literature as a significant challenge for continuation of breastfeeding [ 48 ]. Lack of supportive workplace environments [ 39 ] or inability to express milk were cited by women as barriers for continuing breastfeeding in the United States and New Zealand [ 39 , 49 ].

Supports needed to maintain breastfeeding

Due to the central role family members played in women’s experiences of breastfeeding, support from partners as well as female relatives was cited in the literature as key factors shaping women’s breastfeeding decisions [ 1 , 9 , 48 ]. In the articles published in Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom, supportive family members allowed women to share the responsibility of feeding and other childcare activities, which reduced the pressures associated with being a new mother [ 19 , 20 ]. Similarly, encouragement, breastfeeding advice, and validation from healthcare professionals were identified as positively impacting women’s experiences with breastfeeding [ 1 , 22 , 28 ].

Community resources, such as peer support groups, helplines, and in-home breastfeeding support provided mothers with the opportunity to access help when they need it, and hence were reported to be facilitators for breastfeeding [ 19 , 22 , 33 , 44 ]. An increase in the usage of social media platforms, such as Facebook, among breastfeeding mothers for peer support were reported in some studies [ 47 ]. Public health breastfeeding clinics, lactation specialists, antenatal and prenatal classes, as well as education groups for mothers were identified as central support structures for the initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding [ 23 , 24 , 28 , 33 , 39 , 50 ]. Based on the analysis of the reviewed literature, however, access to these services varied greatly geographically and by socio-economic status [ 33 , 51 ]. It is also important to note that local and cultural context played a significant role in shaping women’s perceptions of breastfeeding. For example, a study that explored women’s breastfeeding experiences in Iceland highlighted the importance of breastfeeding in Icelandic society [ 52 ]. Women are expected to breastfeed and the decision to forgo breastfeeding is met with disproval [ 52 ]. Cultural beliefs regarding breastfeeding were also deemed important in the study of Szafrankska and Gallagher (2016), who noted that Polish women living in Ireland had a much higher rate of initiating breastfeeding compared to Irish women [ 53 ]. They attributed these differences to familial and societal expectations regarding breastfeeding in Poland [ 53 ].

Overall, the reviewed literature suggested that women faced socio-cultural pressure to breastfeed their infants [ 36 , 40 , 54 ]. Women reported initiating breastfeeding due to recognition of the many benefits it brings to the health of the child, even when they were reluctant to do it for personal reasons [ 8 ]. This hints at the success of public health education campaigns on the benefits of breastfeeding, which situates breastfeeding as a new cultural norm [ 24 ].

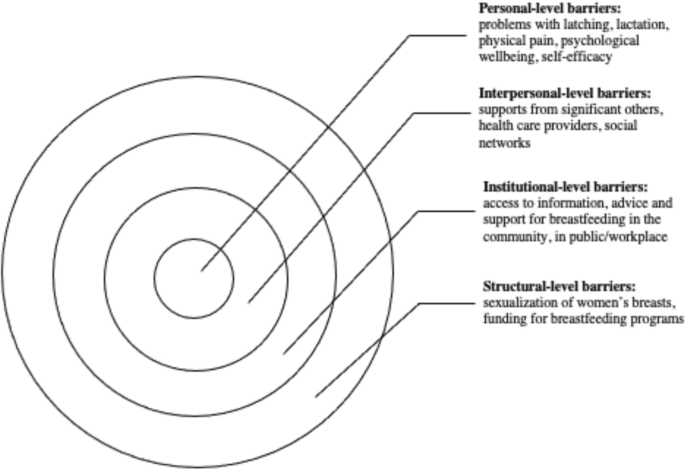

This scoping review examined the existing empirical literature on women’s perceptions about and experiences of breastfeeding to identify how public health messaging can be tailored to improve breastfeeding rates. The literature suggests that, overall, mothers are aware of the positive impacts of breastfeeding and have strong motivation to breastfeed [ 37 ]. However, women who chose to breastfeed also experience many barriers related to their social interactions with significant others and their unique socio-cultural contexts [ 25 ]. These different factors, summarized in Fig. 5 , should be considered in developing public health activities that promote breastfeeding. Breastfeeding experiences for women were very similar across the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, and Australia based on the studies included in this review. Likewise, barriers and supports to breastfeeding identified by women across the countries situated in the global north were quite similar. However, local policy context also impacted women’s experiences of breastfeeding. For example, maintaining breastfeeding while returning to paid employment has been identified as a challenge for mothers in the United States [ 39 , 45 ], a country with relatively short paid parental leave. Still, challenges with balancing breastfeeding while returning to paid employment were also noticed among women in New Zealand, despite a more generous maternity leave [ 49 ]. This suggests that while local and institutional policies might shape women’s experiences of breastfeeding, interpersonal and personal factors can also play a central role in how long they breastfeed their infants. Evidently, the importance of significant others, such as family members or friends, in providing support to breastfeeding mothers was cited as a key facilitator for breastfeeding across multiple geographic locations [ 29 , 34 , 48 ]. In addition, cultural beliefs and practices were also cited as an important component in either promoting breastfeeding or deterring women’s desire to initiate or maintain breastfeeding [ 15 , 29 , 37 ]. Societal support for breastfeeding and cultural practices can therefore partly explain the variation in breastfeeding rates across different countries [ 15 , 21 ]. Figure 5 summarizes the key barriers identified in the literature that inhibit women’s ability to breastfeed.

Barriers to Breastfeeding

At the individual level, women might experience challenges with breastfeeding stemming from various physiological and psychological problems, such as issues with latching, perceived or actual lack of breastmilk, and physical pain associated with breastfeeding. The onset of postpartum depression or other psychological problems may also impact women’s ability to breastfeed [ 54 ]. Given that many women assume that breastfeeding will happen “naturally” [ 15 , 40 ] these challenges can deter women from initiating or continuing breastfeeding. In light of these personal challenges, it is important to consider the potential challenges associated with breastfeeding that are conveyed to new mothers through the simplified message “breast is best” [ 21 ]. While breastfeeding may come easy to some women, most papers included in this review pointed to various challenges associated with initiating or maintaining breastfeeding [ 19 , 33 ]. By modifying public health messaging regarding breastfeeding to acknowledge that breastfeeding may pose a challenge and offering supports to new mothers, it might be possible to alleviate some of the guilt mothers experience when they are unable to breastfeed.

Barriers that can be experienced at the interpersonal level concern women’s communication with others regarding their breastfeeding choices and practices. The reviewed literature shows a strong impact of women’s social networks on their decision to breastfeed [ 24 , 33 ]. In particular, significant others – partners, mothers, siblings and close friends – seem to have a considerable influence over mothers’ decision to breastfeed [ 42 , 53 , 55 ]. Hence, public health messaging should target not only mothers, but also their significant others in developing breastfeeding campaigns. Social media may also be a potential medium for sharing supports and information regarding breastfeeding with new mothers and their significant others.

There is also a strong need for breastfeeding supports at the institutional and community levels. Access to lactation consultants, sound and practical advice from health care providers, and availability of physical spaces in the community and (for women who return to paid employment) in the workplace can provide more opportunities for mothers who want to breastfeed [ 18 , 33 , 44 ]. The findings from this review show, however, that access to these supports and resources vary greatly, and often the women who need them the most lack access to them [ 56 ].

While women make decisions about breastfeeding in light of their own personal circumstances, it is important to note that these circumstances are shaped by larger structural, social, and cultural factors. For instance, mothers may feel reluctant to breastfeed in public, which may stem from their familiarity with dominant cultural perspectives that label breasts as objects for sexualized pleasure [ 48 ]. The reviewed literature also showed that, despite the initial support, mothers who continue to breastfeed past the first year may be judged and scrutinized by others [ 47 ]. Tailoring public health care messaging to local communities with their own unique breastfeeding-related beliefs might help to create a larger social change in sociocultural norms regarding breastfeeding practices.

The literature included in this scoping review identified the importance of support from community services and health care providers in facilitating women’s breastfeeding behaviours [ 22 , 24 ]. Unfortunately, some mothers felt that the support and information they received was inadequate, impractical, or infused with conflicting messaging [ 28 , 44 ]. To make breastfeeding support more accessible to women across different social positions and geographic locations, it is important to acknowledge the need for the development of formal infrastructure that promotes breastfeeding. This includes training health care providers to help women struggling with breastfeeding and allocating sufficient funding for such initiatives.

Overall, this scoping review revealed the need for healthcare professionals to provide practical breastfeeding advice and realistic solutions to women encountering difficulties with breastfeeding. Public health messaging surrounding breastfeeding must re-invent breastfeeding as a “family practice” that requires collaboration between the breastfeeding mother, their partner, as well as extended family to ensure that women are supported as they breastfeed [ 8 ]. The literature also highlighted the issue of healthcare professionals easily giving up on women who encounter problems with breastfeeding and automatically recommending the initiation of formula use without further consideration towards solutions for breastfeeding difficulties [ 19 ]. While some challenges associated with breastfeeding are informed by local culture or health care policies, most of the barriers experienced by breastfeeding women are remarkably universal. Women often struggle with initiation of breastfeeding, lack of support from their significant others, and lack of appropriate places and spaces to breastfeed [ 25 , 26 , 33 , 39 ]. A change in public health messaging to a more flexible messaging that recognizes the challenges of breastfeeding is needed to help women overcome negative feelings associated with failure to breastfeed. Offering more personalized advice and support to breastfeeding mothers can improve women’s experiences and increase the rates of breastfeeding while also boosting mothers’ sense of self-efficacy.

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. First, the focus on “women’s experiences” rendered broad search criteria but may have resulted in the over or underrepresentation of specific findings in this review. Also, the exclusion of empirical work published in languages other than English rendered this review reliant on the papers published predominantly in English-speaking countries. Finally, consistent with Arksey and O’Malley’s [ 18 ] scoping review methodology, we did not appraise the quality of the reviewed literature. Notwithstanding these limitations, this review provides important insights into women’s experiences of breastfeeding and offers practical strategies for improving dominant public health messaging on the importance of breastfeeding.

Women who breastfeed encounter many difficulties when they initiate breastfeeding, and most women are unsuccessful in adhering to current public health breastfeeding guidelines. This scoping review highlighted the need for reconfiguring public health messaging to acknowledge the challenges many women experience with breastfeeding and include women’s social networks as a target audience for such messaging. This review also shows that breastfeeding supports and counselling are needed by all women, but there is also a need to tailor public health messaging to local social norms and culture. The role social institutions and cultural discourses have on women’s experiences of breastfeeding must also be acknowledged and leveraged by health care professionals promoting breastfeeding.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Wolf JH. Low breastfeeding rates and public health in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(12):2000–2010. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/ https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.12.2000

World Health Organization, UNICEF. Global nutrition targets 2015: Breastfeeding policy brief 2014.

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). Breastfeeding in the UK. 2019 [cited 2021 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/about/breastfeeding-in-the-uk/

Semenic S, Loiselle C, Gottlieb L. Predictors of the duration of exclusive breastfeeding among first-time mothers. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(5):428–441. [cited 2021 Apr 21] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/ https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20275