Differentiating between descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches

Affiliations.

- 1 Sultan Qaboos University College of Nursing, Muscat, Oman.

- 2 University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa.

- PMID: 26168810

- DOI: 10.7748/nr.22.6.22.e1344

Aim: To provide insight into how descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches can guide nurse researchers during the generation and application of knowledge.

Background: Phenomenology is a discipline that investigates people's experiences to reveal what lies 'hidden' in them. It has become a major philosophy and research method in the humanities, human sciences and arts. Phenomenology has transitioned from descriptive phenomenology, which emphasises the 'pure' description of people's experiences, to the 'interpretation' of such experiences, as in hermeneutic phenomenology. However, nurse researchers are still challenged by the epistemological and methodological tenets of these two methods.

Data sources: The data came from relevant online databases and research books.

Review methods: A review of selected peer-reviewed research and discussion papers published between January 1990 and December 2013 was conducted using CINAHL, Science Direct, PubMed and Google Scholar databases. In addition, selected textbooks that addressed phenomenology as a philosophy and as a research methodology were used.

Discussion: Evidence from the literature indicates that most studies following the 'descriptive approach' to research are used to illuminate poorly understood aspects of experiences. In contrast, the 'interpretive/hermeneutic approach' is used to examine contextual features of an experience in relation to other influences such as culture, gender, employment or wellbeing of people or groups experiencing the phenomenon. This allows investigators to arrive at a deeper understanding of the experience, so that caregivers can derive requisite knowledge needed to address such clients' needs.

Conclusion: Novice nurse researchers should endeavour to understand phenomenology both as a philosophy and research method. This is vitally important because in-depth understanding of phenomenology ensures that the most appropriate method is chosen to implement a study and to generate knowledge for nursing practice.

Implications for research/practice: This paper adds to the current debate on why it is important for nurse researchers to clearly understand phenomenology as a philosophy and research method before embarking on a study. The paper guides novice researchers on key methodological decisions they need to make when using descriptive or interpretive phenomenological research approaches.

Keywords: Nursing research; descriptive phenomenology; interpretive phenomenology; novice researchers; qualitative research; research methodology.

Publication types

- Comparative Study

- Data Collection / methods*

- Nursing Methodology Research

- Nursing Research / methods*

- Peer Review, Research

- Qualitative Research

- Research Design*

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

12 Interpretive research

Chapter 11 introduced interpretive research—or more specifically, interpretive case research. This chapter will explore other kinds of interpretive research. Recall that positivist or deductive methods—such as laboratory experiments and survey research—are those that are specifically intended for theory (or hypotheses) testing. Interpretive or inductive methods—such as action research and ethnography—one the other hand, are intended for theory building. Unlike a positivist method, where the researcher tests existing theoretical postulates using empirical data, in interpretive methods, the researcher tries to derive a theory about the phenomenon of interest from the existing observed data.

The term ‘interpretive research’ is often used loosely and synonymously with ‘qualitative research’, although the two concepts are quite different. Interpretive research is a research paradigm (see Chapter 3) that is based on the assumption that social reality is not singular or objective. Rather, it is shaped by human experiences and social contexts (ontology), and is therefore best studied within its sociohistoric context by reconciling the subjective interpretations of its various participants (epistemology). Because interpretive researchers view social reality as being embedded within—and therefore impossible to abstract from—their social settings, they ‘interpret’ the reality though a ‘sense-making’ process rather than a hypothesis testing process. This is in contrast to the positivist or functionalist paradigm that assumes that the reality is relatively independent of the context, can be abstracted from their contexts, and studied in a decomposable functional manner using objective techniques such as standardised measures. Whether a researcher should pursue interpretive or positivist research depends on paradigmatic considerations about the nature of the phenomenon under consideration and the best way to study it.

However, qualitative versus quantitative research refers to empirical or data-oriented considerations about the type of data to collect and how to analyse it. Qualitative research relies mostly on non-numeric data, such as interviews and observations, in contrast to quantitative research which employs numeric data such as scores and metrics. Hence, qualitative research is not amenable to statistical procedures such as regression analysis, but is coded using techniques like content analysis. Sometimes, coded qualitative data is tabulated quantitatively as frequencies of codes, but this data is not statistically analysed. Many puritan interpretive researchers reject this coding approach as a futile effort to seek consensus or objectivity in a social phenomenon which is essentially subjective.

Although interpretive research tends to rely heavily on qualitative data, quantitative data may add more precision and clearer understanding of the phenomenon of interest than qualitative data. For example, Eisenhardt (1989), [1] in her interpretive study of decision-making in high-velocity firms (discussed in the previous chapter on case research), collected numeric data on how long it took each firm to make certain strategic decisions—which ranged from approximately six weeks to 18 months—how many decision alternatives were considered for each decision, and surveyed her respondents to capture their perceptions of organisational conflict. Such numeric data helped her clearly distinguish the high-speed decision-making firms from the low-speed decision-makers without relying on respondents’ subjective perceptions, which then allowed her to examine the number of decision alternatives considered by and the extent of conflict in high-speed versus low-speed firms. Interpretive research should attempt to collect both qualitative and quantitative data pertaining to the phenomenon of interest, and so should positivist research as well. Joint use of qualitative and quantitative data—often called ‘mixed-mode design’—may lead to unique insights, and is therefore highly prized in the scientific community.

Interpretive research came into existence in the early nineteenth century—long before positivist techniques were developed—and has its roots in anthropology, sociology, psychology, linguistics, and semiotics. Many positivist researchers view interpretive research as erroneous and biased, given the subjective nature of the qualitative data collection and interpretation process employed in such research. However, since the 1970s, many positivist techniques’ failure to generate interesting insights or new knowledge has resulted in a resurgence of interest in interpretive research—albeit with exacting methods and stringent criteria to ensure the reliability and validity of interpretive inferences.

Distinctions from positivist research

In addition to the fundamental paradigmatic differences in ontological and epistemological assumptions discussed above, interpretive and positivist research differ in several other ways. First, interpretive research employs a theoretical sampling strategy, where study sites, respondents, or cases are selected based on theoretical considerations such as whether they fit the phenomenon being studied (e.g., sustainable practices can only be studied in organisations that have implemented sustainable practices), whether they possess certain characteristics that make them uniquely suited for the study (e.g., a study of the drivers of firm innovations should include some firms that are high innovators and some that are low innovators, in order to draw contrast between these firms), and so forth. In contrast, positivist research employs random sampling —or a variation of this technique—in which cases are chosen randomly from a population for the purpose of generalisability. Hence, convenience samples and small samples are considered acceptable in interpretive research—as long as they fit the nature and purpose of the study—but not in positivist research.

Second, the role of the researcher receives critical attention in interpretive research. In some methods such as ethnography, action research, and participant observation, the researcher is considered part of the social phenomenon, and their specific role and involvement in the research process must be made clear during data analysis. In other methods, such as case research, the researcher must take a ’neutral’ or unbiased stance during the data collection and analysis processes, and ensure that their personal biases or preconceptions do not taint the nature of subjective inferences derived from interpretive research. In positivist research, however, the researcher is considered to be external to and independent of the research context, and is not presumed to bias the data collection and analytic procedures.

Third, interpretive analysis is holistic and contextual, rather than being reductionist and isolationist. Interpretive interpretations tend to focus on language, signs, and meanings from the perspective of the participants involved in the social phenomenon, in contrast to statistical techniques that are employed heavily in positivist research. Rigor in interpretive research is viewed in terms of systematic and transparent approaches to data collection and analysis, rather than statistical benchmarks for construct validity or significance testing.

Lastly, data collection and analysis can proceed simultaneously and iteratively in interpretive research. For instance, the researcher may conduct an interview and code it before proceeding to the next interview. Simultaneous analysis helps the researcher correct potential flaws in the interview protocol or adjust it to capture the phenomenon of interest better. The researcher may even change their original research question if they realise that their original research questions are unlikely to generate new or useful insights. This is a valuable—but often understated—benefit of interpretive research, and is not available in positivist research, where the research project cannot be modified or changed once the data collection has started without redoing the entire project from the start.

Benefits and challenges of interpretive research

Interpretive research has several unique advantages. First, it is well-suited for exploring hidden reasons behind complex, interrelated, or multifaceted social processes—such as inter-firm relationships or inter-office politics—where quantitative evidence may be biased, inaccurate, or otherwise difficult to obtain. Second, it is often helpful for theory construction in areas with no or insufficient a priori theory. Third, it is also appropriate for studying context-specific, unique, or idiosyncratic events or processes. Fourth, interpretive research can also help uncover interesting and relevant research questions and issues for follow-up research.

At the same time, interpretive research also has its own set of challenges. First, this type of research tends to be more time and resource intensive than positivist research in data collection and analytic efforts. Too little data can lead to false or premature assumptions, while too much data may not be effectively processed by the researcher. Second, interpretive research requires well-trained researchers who are capable of seeing and interpreting complex social phenomenon from the perspectives of the embedded participants, and reconciling the diverse perspectives of these participants, without injecting their personal biases or preconceptions into their inferences. Third, all participants or data sources may not be equally credible, unbiased, or knowledgeable about the phenomenon of interest, or may have undisclosed political agendas which may lead to misleading or false impressions. Inadequate trust between the researcher and participants may hinder full and honest self-representation by participants, and such trust building takes time. It is the job of the interpretive researcher to ‘see through the smoke’ (i.e., hidden or biased agendas) and understand the true nature of the problem. Fourth, given the heavily contextualised nature of inferences drawn from interpretive research, such inferences do not lend themselves well to replicability or generalisability. Finally, interpretive research may sometimes fail to answer the research questions of interest or predict future behaviours.

Characteristics of interpretive research

All interpretive research must adhere to a common set of principles, as described below.

Naturalistic inquiry: Social phenomena must be studied within their natural setting.

Because interpretive research assumes that social phenomena are situated within—and cannot be isolated from—their social context, interpretations of such phenomena must be grounded within their sociohistorical context. This implies that contextual variables should be observed and considered in seeking explanations of a phenomenon of interest, even though context sensitivity may limit the generalisability of inferences.

Researcher as instrument: Researchers are often embedded within the social context that they are studying, and are considered part of the data collection instrument in that they must use their observational skills, their trust with the participants, and their ability to extract the correct information. Further, their personal insights, knowledge, and experiences of the social context are critical to accurately interpreting the phenomenon of interest. At the same time, researchers must be fully aware of their personal biases and preconceptions, and not let such biases interfere with their ability to present a fair and accurate portrayal of the phenomenon.

Interpretive analysis: Observations must be interpreted through the eyes of the participants embedded in the social context. Interpretation must occur at two levels. The first level involves viewing or experiencing the phenomenon from the subjective perspectives of the social participants. The second level is to understand the meaning of the participants’ experiences in order to provide a ‘thick description’ or a rich narrative story of the phenomenon of interest that can communicate why participants acted the way they did.

Use of expressive language: Documenting the verbal and non-verbal language of participants and the analysis of such language are integral components of interpretive analysis. The study must ensure that the story is viewed through the eyes of a person, and not a machine, and must depict the emotions and experiences of that person, so that readers can understand and relate to that person. Use of imageries, metaphors, sarcasm, and other figures of speech are very common in interpretive analysis.

Temporal nature: Interpretive research is often not concerned with searching for specific answers, but with understanding or ‘making sense of’ a dynamic social process as it unfolds over time. Hence, such research requires the researcher to immerse themself in the study site for an extended period of time in order to capture the entire evolution of the phenomenon of interest.

Hermeneutic circle: Interpretive interpretation is an iterative process of moving back and forth from pieces of observations (text), to the entirety of the social phenomenon (context), to reconcile their apparent discord, and to construct a theory that is consistent with the diverse subjective viewpoints and experiences of the embedded participants. Such iterations between the understanding/meaning of a phenomenon and observations must continue until ‘theoretical saturation’ is reached, whereby any additional iteration does not yield any more insight into the phenomenon of interest.

Interpretive data collection

Data is collected in interpretive research using a variety of techniques. The most frequently used technique is interviews (face-to-face, telephone, or focus groups). Interview types and strategies are discussed in detail in Chapter 9. A second technique is observation . Observational techniques include direct observation , where the researcher is a neutral and passive external observer, and is not involved in the phenomenon of interest (as in case research), and participant observation , where the researcher is an active participant in the phenomenon, and their input or mere presence influence the phenomenon being studied (as in action research). A third technique is documentation , where external and internal documents—such as memos, emails, annual reports, financial statements, newspaper articles, or websites—may be used to cast further insight into the phenomenon of interest or to corroborate other forms of evidence.

Interpretive research designs

Case research . As discussed in the previous chapter, case research is an intensive longitudinal study of a phenomenon at one or more research sites for the purpose of deriving detailed, contextualised inferences, and understanding the dynamic process underlying a phenomenon of interest. Case research is a unique research design in that it can be used in an interpretive manner to build theories, or in a positivist manner to test theories. The previous chapter on case research discusses both techniques in depth and provides illustrative exemplars. Furthermore, the case researcher is a neutral observer (direct observation) in the social setting, rather than an active participant (participant observation). As with any other interpretive approach, drawing meaningful inferences from case research depends heavily on the observational skills and integrative abilities of the researcher.

Action research . Action research is a qualitative but positivist research design aimed at theory testing rather than theory building. This is an interactive design that assumes that complex social phenomena are best understood by introducing changes, interventions, or ‘actions’ into those phenomena, and observing the outcomes of such actions on the phenomena of interest. In this method, the researcher is usually a consultant or an organisational member embedded into a social context —such as an organisation—who initiates an action in response to a social problem, and examines how their action influences the phenomenon, while also learning and generating insights about the relationship between the action and the phenomenon. Examples of actions may include organisational change programs—such as the introduction of new organisational processes, procedures, people, or technology or the replacement of old ones—initiated with the goal of improving an organisation’s performance or profitability. The researcher’s choice of actions must be based on theory, which should explain why and how such actions may bring forth the desired social change. The theory is validated by the extent to which the chosen action is successful in remedying the targeted problem. Simultaneous problem-solving and insight generation are the central feature that distinguishes action research from other research methods (which may not involve problem solving), and from consulting (which may not involve insight generation). Hence, action research is an excellent method for bridging research and practice.

There are several variations of the action research method. The most popular of these methods is participatory action research , designed by Susman and Evered (1978). [2] This method follows an action research cycle consisting of five phases: diagnosing, action-planning, action-taking, evaluating, and learning (see Figure 12.1). Diagnosing involves identifying and defining a problem in its social context. Action-planning involves identifying and evaluating alternative solutions to the problem, and deciding on a future course of action based on theoretical rationale. Action-taking is the implementation of the planned course of action. The evaluation stage examines the extent to which the initiated action is successful in resolving the original problem—i.e., whether theorised effects are indeed realised in practice. In the learning phase, the experiences and feedback from action evaluation are used to generate insights about the problem and suggest future modifications or improvements to the action. Based on action evaluation and learning, the action may be modified or adjusted to address the problem better, and the action research cycle is repeated with the modified action sequence. It is suggested that the entire action research cycle be traversed at least twice so that learning from the first cycle can be implemented in the second cycle. The primary mode of data collection is participant observation, although other techniques such as interviews and documentary evidence may be used to corroborate the researcher’s observations.

Ethnography . The ethnographic research method—derived largely from the field of anthropology—emphasises studying a phenomenon within the context of its culture. The researcher must be deeply immersed in the social culture over an extended period of time—usually eight months to two years—and should engage, observe, and record the daily life of the studied culture and its social participants within their natural setting. The primary mode of data collection is participant observation, and data analysis involves a ‘sense-making’ approach. In addition, the researcher must take extensive field notes, and narrate her experience in descriptive detail so that readers may experience the same culture as the researcher. In this method, the researcher has two roles: rely on her unique knowledge and engagement to generate insights (theory), and convince the scientific community of the transsituational nature of the studied phenomenon.

The classic example of ethnographic research is Jane Goodall’s study of primate behaviours. While living with chimpanzees in their natural habitat at Gombe National Park in Tanzania, she observed their behaviours, interacted with them, and shared their lives. During that process, she learnt and chronicled how chimpanzees seek food and shelter, how they socialise with each other, their communication patterns, their mating behaviours, and so forth. A more contemporary example of ethnographic research is Myra Bluebond-Langer’s (1996) [3] study of decision-making in families with children suffering from life-threatening illnesses, and the physical, psychological, environmental, ethical, legal, and cultural issues that influence such decision-making. The researcher followed the experiences of approximately 80 children with incurable illnesses and their families for a period of over two years. Data collection involved participant observation and formal/informal conversations with children, their parents and relatives, and healthcare providers to document their lived experience.

Phenomenology. Phenomenology is a research method that emphasises the study of conscious experiences as a way of understanding the reality around us. It is based on the ideas of early twentieth century German philosopher, Edmund Husserl, who believed that human experience is the source of all knowledge. Phenomenology is concerned with the systematic reflection and analysis of phenomena associated with conscious experiences such as human judgment, perceptions, and actions. Its goal is (appreciating and describing social reality from the diverse subjective perspectives of the participants involved, and understanding the symbolic meanings (‘deep structure’) underlying these subjective experiences. Phenomenological inquiry requires that researchers eliminate any prior assumptions and personal biases, empathise with the participant’s situation, and tune into existential dimensions of that situation so that they can fully understand the deep structures that drive the conscious thinking, feeling, and behaviour of the studied participants.

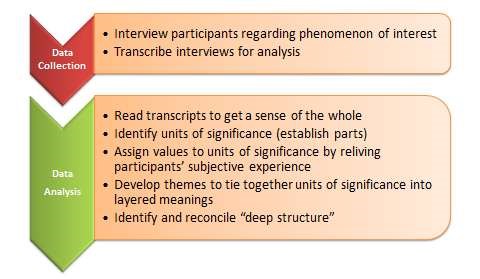

Some researchers view phenomenology as a philosophy rather than as a research method. In response to this criticism, Giorgi and Giorgi (2003) [4] developed an existential phenomenological research method to guide studies in this area. This method, illustrated in Figure 12.2, can be grouped into data collection and data analysis phases. In the data collection phase, participants embedded in a social phenomenon are interviewed to capture their subjective experiences and perspectives regarding the phenomenon under investigation. Examples of questions that may be asked include ‘Can you describe a typical day?’ or ‘Can you describe that particular incident in more detail?’. These interviews are recorded and transcribed for further analysis. During data analysis , the researcher reads the transcripts to: get a sense of the whole, and establish ‘units of significance’ that can faithfully represent participants’ subjective experiences. Examples of such units of significance are concepts such as ‘felt-space’ and ‘felt-time’, which are then used to document participants’ psychological experiences. For instance, did participants feel safe, free, trapped, or joyous when experiencing a phenomenon (‘felt-space’)? Did they feel that their experience was pressured, slow, or discontinuous (‘felt-time’)? Phenomenological analysis should take into account the participants’ temporal landscape (i.e., their sense of past, present, and future), and the researcher must transpose his/herself in an imaginary sense into the participant’s situation (i.e., temporarily live the participant’s life). The participants’ lived experience is described in the form of a narrative or using emergent themes. The analysis then delves into these themes to identify multiple layers of meaning while retaining the fragility and ambiguity of subjects’ lived experiences.

Rigor in interpretive research

While positivist research employs a ‘reductionist’ approach by simplifying social reality into parsimonious theories and laws, interpretive research attempts to interpret social reality through the subjective viewpoints of the embedded participants within the context where the reality is situated. These interpretations are heavily contextualised, and are naturally less generalisable to other contexts. However, because interpretive analysis is subjective and sensitive to the experiences and insight of the embedded researcher, it is often considered less rigorous by many positivist (functionalist) researchers. Because interpretive research is based on a different set of ontological and epistemological assumptions about social phenomena than positivist research, the positivist notions of rigor—such as reliability, internal validity, and generalisability—do not apply in a similar manner. However, Lincoln and Guba (1985) [5] provide an alternative set of criteria that can be used to judge the rigor of interpretive research.

Dependability. Interpretive research can be viewed as dependable or authentic if two researchers assessing the same phenomenon, using the same set of evidence, independently arrive at the same conclusions, or the same researcher, observing the same or a similar phenomenon at different times arrives at similar conclusions. This concept is similar to that of reliability in positivist research, with agreement between two independent researchers being similar to the notion of inter-rater reliability, and agreement between two observations of the same phenomenon by the same researcher akin to test-retest reliability. To ensure dependability, interpretive researchers must provide adequate details about their phenomenon of interest and the social context in which it is embedded, so as to allow readers to independently authenticate their interpretive inferences.

Credibility. Interpretive research can be considered credible if readers find its inferences to be believable. This concept is akin to that of internal validity in functionalistic research. The credibility of interpretive research can be improved by providing evidence of the researcher’s extended engagement in the field, by demonstrating data triangulation across subjects or data collection techniques, and by maintaining meticulous data management and analytic procedures—such as verbatim transcription of interviews, accurate records of contacts and interviews—and clear notes on theoretical and methodological decisions, that can allow an independent audit of data collection and analysis if needed.

Confirmability. Confirmability refers to the extent to which the findings reported in interpretive research can be independently confirmed by others—typically, participants. This is similar to the notion of objectivity in functionalistic research. Since interpretive research rejects the notion of an objective reality, confirmability is demonstrated in terms of ‘intersubjectivity’—i.e., if the study’s participants agree with the inferences derived by the researcher. For instance, if a study’s participants generally agree with the inferences drawn by a researcher about a phenomenon of interest—based on a review of the research paper or report—then the findings can be viewed as confirmable.

Transferability. Transferability in interpretive research refers to the extent to which the findings can be generalised to other settings. This idea is similar to that of external validity in functionalistic research. The researcher must provide rich, detailed descriptions of the research context (‘thick description’) and thoroughly describe the structures, assumptions, and processes revealed from the data so that readers can independently assess whether and to what extent the reported findings are transferable to other settings.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management Journal , 32(3), 543–576. ↵

- Susman, G. I. and Evered, R. D. (1978) An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Administrative Science Quarterly , 23, 582–603. ↵

- Bluebond-Langer, M. (1996). In the shadow of illness: Parents and siblings of the chronically ill child . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ↵

- Giorgi, A., & Giorgi, B. (2003). Phenomenology. In J. A. Smith (ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 25–50). London: Sage Publications ↵

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry . Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. ↵

Social Science Research: Principles, Methods and Practices (Revised edition) Copyright © 2019 by Anol Bhattacherjee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

11 Descriptive and interpretive approaches to qualitative research

- Published: June 2005

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter explores descriptive and interpretive approaches to qualitative research. This includes the formulation of the problem, data collection, the specifics of sampling, data analysis in descriptive/interpretive qualitative research, generation of categories, and extracting and interpreting the main findings.

Qualitative research methods today are a diverse set, encompassing approaches such as empirical phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, protocol analysis and discourse analysis. By one common definition ( Polkinghorne, 1983 ), all these methods rely on linguistic rather than numerical data, and employ meaning-based rather than statistical forms of data analysis. Distinguishing between measuring things with words and measuring them in numbers, however, may not be a particularly useful way of characterising different approaches to research. Instead, other distinctive features of qualitative research may turn out to be of far greater importance ( Elliott, 1999 ):

emphasis on understanding phenomena in their own right (rather than from some outside perspective);

open, exploratory research questions (vs. closed-ended hypotheses);

unlimited, emergent description options (vs. predetermined choices or rating scales);

use of a special strategies for enhancing the credibility of design and analyses (see Elliott, Fischer and Rennie, 1999 ); and

definition of success conditions in terms of discovering something new (vs. confirming what was hypothesised).

Space limitations preclude a complete survey of this rapidly growing field of research methods. Instead, we will focus on what are today regarded as established, well-used methods within the descriptive–interpretive branch of qualitative research. (In particular, we will not cover discourse analysis, e.g., Potter and Wetherell, 1987 ; Stokoe and Wiggins , this volume, or ethnography.) These methods came into their own in the 1970s and 1980s, and have become mainstream in education, nursing, and increasingly in psychology, particularly in non-traditional or professional training schools. Because there is now an extensive history with these methods, standards of good research practice have emerged (e.g., Elliott et al ., 1999 ).

Descriptive–interpretive qualitative research methods go by many ‘brand names’ in which various common elements are mixed and matched according to particular researchers’ predilections; currently popular variations include grounded theory ( Henwood and Pigeon, 1992 ; Strauss and Corbin, 1998 ), empirical phenomenology ( Giorgi, 1975 ; Wertz, 1983 ), hermeneutic-interpretive research ( Packer and Addison, 1989 ), interpretative phenomenological analysis ( Smith, Jarman, Osborn, 1999 ), and Consensual Qualitative Research ( Hill, Thompson, Williams, 1997 ). Following Barker, Pistrang and Elliott (2002) , we find the emphasis on brand names to be confusing and somewhat proprietary. Thus, in our treatment here, we take a generic approach that emphasises common methodological practices rather than relatively minor differences. It is our hope to be able to encourage readers to develop their own individual mix of methods that lend themselves to the topic under investigation and the researchers’ preferences and style of collecting and analysing qualitative data.

In the approach to qualitative research we present here, we begin with the formulation of the research problem, followed by a discussion of issues in qualitative data collection and sampling. We will then go on to present common strategies of data analysis, before concluding by summarising principles of good practice in descriptive-interpretive qualitative research and providing suggestions for further reading and learning.

Formulating the problem

Previously, some qualitative researchers believed that it was better to go into the field without first reading the available literature. The reason for this position was the belief that becoming familiar with previous knowledge would ‘taint’ the researcher, predisposing them to impose their preconceptions on the data and raising the danger of not being sensitive enough to allow the data speak for themselves in order to reveal essential features of the phenomenon. It is our view that this approach is somewhat naive. For one thing, it is now understood that bias is an unavoidable part of the process of coming to know something and that knowledge is impossible without some kind of previous conceptual structure. Far from removing the researcher’s influence on the data, remaining ignorant of previous work on a phenomenon simply ensures that one’s work will be guided by uninformed rather than informed expectations.

For this reason, the formulation of the research problem in qualitative research is similar in many ways to that in quantitative research. As a consequence, before commencing data collection, researchers carefully examine available knowledge and theory, carrying out a thorough literature search that includes up to date information on the topic of investigation. Strauss and Corbin (1998) refer to this as ‘theoretical sensitivity’ quoting Pasteur’s motto, ‘Discovery favours the prepared mind’.

An important feature of this initial phase, however, is that the researcher should become as aware of possible of the nature of their pre-understandings of the phenomenon, as these are likely to shape the data collection, analysis and interpretation. At the same time, the researcher should regard their expectations lightly, in a way that is open to unexpected meanings.

The formulation of research problem is guided by the traditional questions: e.g., What do we know about the phenomenon? Why is it important to know more? What has influenced previous research findings (methodology, social context, researcher theory)? What do we want to make clearer by the new study? Note that the problem formulation itself may not imply a need for a qualitative approach. Therefore, the researcher should not prejudge the question of whether they will use qualitative methods for the study. Instead, use of a qualitative strategy should emerge as a means to answer the particular research questions ( Elliott, 1995 , 2000 ).

The research questions leading to employing qualitative data collection and analysis strategies are usually open-ended and exploratory in nature. Barker et al . (2002) suggest that exploratory questions, suitable as the base for qualitative inquiry are typically used when: (a) there is little known in a particular research area; (b) existing research is confusing, contradictory, or not moving forward; or (c) the topic is highly complex. As to the aim of exploratory questions, Elliott (2000) sees the following types:

Definitional : What is the nature of this phenomenon? What are its defining features? (e.g., What does it mean for patients with metastatic breast cancer to experience help in this existential support group treatment?)

Descriptive : What kinds or varieties does the phenomenon appear in? What aspects does it have? (e.g., In what ways do adolescent patients in a cognitive behavioural treatment for diabetes self-care change?)

Interpretive : Why does the phenomenon come about? How does it unfold over time? (e.g., What is the story or sequence of patients’ improvement in a post-surgery cardiac rehabilitation programme? What changes led to what other changes?)

Critical/action : What’s wrong (or right) about the phenomenon? How could it be made better? (e.g., What complaints do patients have about a specialist sleep disorder clinic?)

Deconstruction : What assumptions are made in this research? Whose social or political interests are served by it? (e.g., What are the cultural and sociopolitical implications of the way in which patient outcome has been measured in behavioural medicine research, such as focusing on pathology as opposed to health?)

Data collection

While the formulation of the research problem does not distinguish sharply between quantitative and qualitative research traditions, data collection often differs dramatically. There is a difference in the format of the data, but also in the general strategy for obtaining the data. As to the format, simply stated, qualitative inquiry looks for verbal accounts or descriptions in words, or it puts observations into words (occasionally it also uses other forms of description, e.g., drawings by children with leukaemia). Another major difference is that it uses open-ended questions. However, more importantly, it also uses an open-ended strategy for obtaining the data. By ‘open-ended’ we mean not only that participants are encouraged to elaborate on their accounts, or that observations are not restricted to certain pre-existing categories. Rather, open-endedness refers to the general strategy of data gathering. It means that inquiry is flexible and carefully adapted to the problem at hand and to the individual informant’s particular experiences and abilities to communicate those experiences, making each interview unique.

There are several methods of obtaining information for qualitative inquiry. Qualitative interviews are the most common general approach, with semi-structured and unstructured interview formats predominating. In these forms of interview, participants are asked to provide elaborated accounts about particular experiences (e.g., tell me about a time when your asthma was particularly severe). The interviewer should have basic skills plus additional training in open-ended interviewing; such interviews are very similar to the empathic exploration found in good person-centred therapy ( Mearns and Thorne, 1999 ). Good practice is to develop an interview guide that helps the interviewer focus the interview without imposing too much structure. Hill et al . (1997) recommend providing interviewees with a list of questions before the interview.

Variant formats

Self-report questionnaires are used much less in qualitative research, because they typically do not stimulate the needed level of elaboration sought by the qualitative researcher. However, given time and space constraints, questionnaires may be used as well. In that case they naturally consist of open-ended questions and ask respondents for elaboration, examples, etc. A good practice is to build in the opportunity to follow-up on questionnaires by phone interview ( Hill et al ., 1997 ) or email correspondence, as responses often do not provide enough elaboration to understand the respondents’ point.

A popular alternate form of qualitative interview is the focus group (see Wilkinson , this volume, for more information), a group format in which participants share and discuss their views of a particular topic (e.g., needed services for teenagers with spina bifida), allowing access to a large number of possible views and a replication of naturalistic social influence and consensus processes. A special form of qualitative interview, used, for example, in research on helping processes (e.g., between breast cancer patients and their partners; Barker, Pistrang and Rutter, 1997 ), is tape-assisted recall. Here, a recording of an interaction is played back for the interviewee so that they can recall and describe their experience of particular moments ( Elliott, 1986 ). Finally, think-aloud protocols ( McLeod, 1999 ) are special forms of interview in which the participant is asked to verbalise their thought processes as they deal with a problem (e.g., managing an episode of high blood sugar).

When observational methods are used in qualitative research they typically make extensive use of field notes or memos. These notes are primarily descriptive and observational but may also include the researcher’s interpretations and reactions, as long as these are clearly labelled as such. Qualitative observational methods often use non-interview archival data, such as tape recordings and associated transcripts of doctor–patient interactions. (Projective techniques can also be used as methods of data collection in qualitative research but are rarely seen, especially in clinical and health psychology.)

There are three key aspects typical of the data collection in descriptive/interpretive qualitative research worth mentioning at this point:

First, despite the fact that data collection in qualitative research generally does not use pre-existing categories for sorting the data, it always has a focus. The focus is naturally driven by the specific research questions. (At the same time, however, the general research approach encourages constructive critique and openness to reassessment of the chosen focus, if the data begin to point in a different direction.)

Second, qualitative interviews are distinguished by their deliberate giving of power to respondents, in the sense that they become co-researchers. The interviewer tries to empower respondents to take the lead and to point out important features of the phenomenon as they see it. For example, respondents may be encouraged not only to reveal aspects of their experiences that were not expected by the researcher, but also to suggest improvements in the research procedure.

Last but not least, a triangulation strategy is often used in this kind of research, with data gathered by multiple methods (e.g., observation and interviewing). This strategy can yield a richer and more balanced picture of the phenomenon, and also serves as a cross-validation method.

Specifics of sampling

Sampling in qualitative research, as in the quantitative tradition, is focused on the application of findings beyond the research sample. However, we cannot talk about generalisability in a traditional sense of stratified random sampling. Qualitative research does not aim at securing confidence intervals of studied variables around exact values in a population. Instead, qualitative research typically tries to sample broadly enough and to interview deeply enough that all the important aspects and variations of the studied phenomenon are captured in the sample – whether the sample be 8 or 100! Generalisability of specific population values or relationships is thus replaced by a thorough specification of the characteristics of the sample, so that one can make judgements about the applicability of the findings. As to the sample size, qualitative research does not use power analysis to determine the needed n , but instead mostly commonly uses the criterion of saturation ( Strauss and Corbin, 1998 ), which means adding new cases to the point of diminishing returns, when no new information emerges. Obviously, given the nature of the data collected, and the time-consuming nature of analysis (see below) the size of the samples is usually much lower than in quantitative research.

In order to satisfy the saturation criterion, the most common sampling strategy used in qualitative research can be labelled as purposeful sampling ( Creswell, 1998 ). That is, if the study aims to depict central, important or decisive aspects of the investigated phenomenon, then sampling should assure that these are covered. In the grounded theory tradition, where the result of the study is a complete theory of the phenomenon, the preferred sampling strategy is referred to as theoretical sampling . This kind of sampling is driven by the need of the researchers to cover the relevant aspects of developing theory. Obviously then, sampling in qualitative research can and should be flexible and should reflect the research problem, ranging from sampling for maximum variation to focusing in-depth on a single exceptional case (see sampling strategies in Miles and Huberman, 1994 ).

Data analysis in descriptive/interpretive qualitative research

Qualitative research also requires flexibility during the analysis phase as well, with procedures developing in response to the ongoing analysis. Critical challenge is a key but sometimes overlooked aspect of qualitative data analysis, as the researcher uses constant critical (but not paralysing) self-reflection and challenging scepticism with regard to the analysis methods and the emerging results. We could say that all steps of the analysis are taken prudently with much reflection. Checking and auditing all steps of the analysis is natural part of the qualitative research, as well as careful archiving of each step of the analysis for later checking. The analysis has also to be systematic and organised , so the researcher can easily locate information the data set and can trace provisional results of the analysis back to the context of the data.

However, in spite of cherishing flexibility, qualitative research often employs a general strategy that provides the backbone for the analysis. In grounded theory, this strategy is referred to as axial coding ( Strauss and Corbin, 1998 ); in consensual qualitative research ( Hill et al ., 1997 ), it takes the form of a set of general domains that are used to organise the data (e.g., context → illness onset → coping → outcome).

We provide here a general framework for descriptive/interpretive qualitative research. We use this framework in our own work (e.g., Elliott et al , 1994 ; Timulak and Elliott, 2003 ) and note that it is similar to and influenced by comparable frameworks used by other researchers (e.g., Hill et al ., 1997 ). Even in our own research work, however, it is just a general structure that we use flexibly and, as appropriate, modify or add to.

Data preparation

The first step of analysis is data preparation. The data are usually obtained in the form of notes and tape recordings. In case of tape recordings, the data are first transcribed verbatim. In case of the combination of researcher observational notes and transcribed recordings, the notes are usually interwoven with the transcripts, often using different fonts, so that the researcher’s voice can be clearly distinguished from the informant’s voice in the data. During this stage of the analysis, it is worthwhile to read the whole data set, so that the researcher can get the whole picture of the studied phenomenon. During this initial reading, insights and understandings begin to emerge and are written down as memos. This is a kind of pre-analysis that can influence future steps of the analysis because the first relevancies start to unfold.

During or after the initial reading an initial editing of the data often takes place. Obvious redundancies, repetitions, and unimportant digressions are omitted. One must, of course, be sure that the deleted data do not constitute important and relevant aspects of the phenomenon. Checks in the form of independent and challenging auditing processes by either the main analyst or others can be applied here also.

Delineating and processing meaning units

Next, we start to divide the data into distinctive meaning units (cf. Rennie, Phillips and Quartaro, 1988 ; Wertz, 1983 ). Meaning units are usually parts of the data that even if standing out of the context, would communicate sufficient information to provide a piece of meaning to the reader. The length of the meaning unit depends on the judgement of the researcher, who must assess how different lengths of meaning unit will affect the further steps of the analysis and who also should adopt a meaning unit size that is appropriate to their cognitive style and the data at hand. Generally, the longer the meaning unit is the bigger number (variety) of meanings it contains but the clearer its contextual meaning will be.

As we delineate the meaning units, we can shorten them by getting rid of redundancies that do not change the meanings contained in them. For example, in a study of significant events in cognitive therapy with a diabetic patient, the data might read: ‘What was important for me was that the therapist verbalised exactly how I feel about my diabetes. The words she used helped me to be more aware of the things about it that I am having trouble with.’ A shortened version of this, which we would use in the further analysis, might then look as follows: ‘T verbalised exactly how P felt about her illness – it helped P to be more aware of what aspects of it P is having trouble with.’ (T stands for the therapist and P for the patient.)

The meaning units are the units with which we do the analysis. However, it is good to be able to trace them back to the full data protocol, in case we need to be able clarify something from the context. For that reason it is a very good idea to assign a consecutive code (in numbers and letters) to each meaning unit. The code should localise the unit in the original protocol. For example, if for each case we use different letter, we immediately know where meaning unit H82 came from. This procedure facilitates auditing.

Finding an overall organising structure for the data

Naturally, different sets of meaning units describe different aspects of the phenomenon. From their pre-research understanding of the phenomenon and their first reading of the data the researcher already has some ideas about some very broad headings for organising the phenomenon into different processes or phases, referred to as domains . In fact, the researchers often introduce this structure into the data from the beginning via the interview question themselves. Nevertheless, the researcher typically waits until they finally sit down to code the data before developing a formal version of this organising framework in relation to the first one or two data protocols. Consistent with this practice, Hill et al . (1997) recommend sorting the data into domains that provide a conceptual framework for the data, referred to in grounded theory as axial coding ( Strauss and Corbin, 1998 ). As noted, this framework for meaningfully organising the data should be flexible and tested until it fits the data. It is important that the researcher always be open to using the data to restructure the organising conceptual framework. Critical auditing and testing out different possible frameworks are both useful strategies here.

In studies reported in the literature, it is possible to find various kinds of relationship between domains, including temporal sequence (these things happened before these things), causes (this influenced this), significations (that is what this thing means now), etc. We typically find a variety of different types of structuring. Sometimes the domains may also mirror the different sources of the data, e.g., different kinds of observation, different kinds of self-report. If it is conceptually meaningful or in cases when the researcher is not sure about the structuring the data for the moment, it is possible to assign some data to more than one domain.

Generation of categories

Next, the meaning units are coded or categorised within each of the domains into which they have been organised. The categories evolve from the meanings in the meaning units. The word category refers to the aim of discerning regularities or similarities in the data ( Glaser and Strauss, 1967 ). Creation of categories is an interpretive process on the part of the researcher (or in many cases the team of researchers, cf. Hill et al ., 1997 ), in which the researcher is trying to respect the data and use category labels close to the original language of participants. On the other hand, ideas for categories also come in part from the researcher’s knowledge of previous theorising and findings in other studies. Categorising is thus an interactive process in which priority is given to the data but understanding is inevitably facilitated by previous understanding. It is a kind of dialogue with the data . (In grounded theory this step is referred to as open coding .)