An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

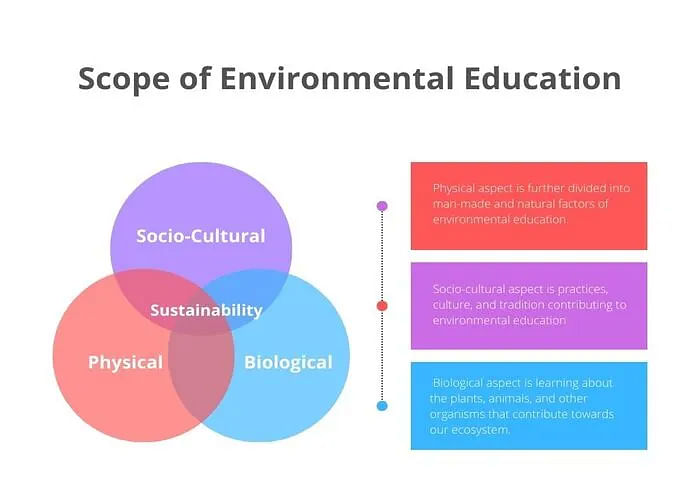

What is Environmental Education?

Environmental education is a process that allows individuals to explore environmental issues, engage in problem solving, and take action to improve the environment. As a result, individuals develop a deeper understanding of environmental issues and have the skills to make informed and responsible decisions.

The components of environmental education are:

- Awareness and sensitivity to the environment and environmental challenges

- Knowledge and understanding of the environment and environmental challenges

- Attitudes of concern for the environment and motivation to improve or maintain environmental quality

- Skills to identify and help resolve environmental challenges

- Participation in activities that lead to the resolution of environmental challenges

Environmental education does not advocate a particular viewpoint or course of action. Rather, environmental education teaches individuals how to weigh various sides of an issue through critical thinking and it enhances their own problem-solving and decision-making skills.

The National Environmental Education Act of 1990 requires EPA to provide national leadership to increase environmental literacy. EPA established the Office of Environmental Education to implement this program.

- Environmental Education Home

- National Environmental Education Advisory Council (NEEAC)

- National Environmental Education Training Program

- Presidential Innovation Award for Environmental Educators

- President's Environmental Youth Award

- Environmental Education (EE) Grants

What is Environmental Education?

Environmental education is a learning process that increases people's knowledge and awareness about the environment and associated challenges, develops the necessary skills and expertise to address the challenges, and fosters attitudes, motivations, and commitments to make informed decisions and take responsible action.

Why Does Environmental Education Matter?

Did you grow up catching fireflies, playing in the creek, or building forts in your backyard? Most children in today’s world won’t , which means that when they grow up, they may not have a vested interest in protecting our natural resources and natural spaces. Environmental educators across North Carolina are working to change that.

Environmental education is critical for a sustainable future. It provides time in, and a connection to, the outdoors which research has shown to improve academic p erformance and physical, mental, and emotional health - making it just as important for our participants as it is for the planet. More than ever, children and adults need to know how ecological systems work and why they matter. The health of the environment is inseparable from humans’ well-being and economic prosperity . People require knowledge, tools and sensitivity to successfully address and solve environmental problems in their daily lives.

Environmental education...has the power to transform lives and society. It informs and inspires. It influences attitudes. It motivates action. Environmental education is a key tool in expanding the constituency for the environmental movement and creating healthier and more civically-engaged communities. -North American Association for Environmental Education

Environmental education works.

Over the last few decades, thousands of studies have been completed to analyze the effectiveness of EE. “The studies clearly showed that students taking part in environmental education programming gained knowledge about the environment. But the studies also showed that learning about the environment is just the tip of the iceberg.” (NAAEE)

This research has demonstrated that environmental education:

Has widespread public support

Improves standardized test sc ores and academic performance

Promotes 21st century skills such as critical thinking, oral communication, analytical skills, problem solving, and higher-order thinking

Supports STEM topics and is interdisciplinary

Bolsters civic engagement and empowerment

Sparks stewardship behavior and environmental actions

Encourages students’ personal growth including teamwork, confidence, autonomy, and leadership

Increases motivation and interest in learning

Is an “equalizer” allowing educators to cater to multiple student interests, skills, abilities, and special needs,Helps improve teacher skills and classroom engagement

Is a cost-effective investment, promoting multiple environmental and societal benefits, and

Strengthens communities by connecting schools to local organizations and agencies.

To learn more about the original research, you can check out eeWorks and the Children’s and Nature Network’s Research Library.

Environmental Education Promotes

Environmental literacy.

“Environmental education is a resource that transcends the classroom—both in character and scope. In the classroom and beyond, the desired outcome of environmental education is environmental literacy. What is Environmental Literacy? In North Carolina, environmental literacy is defined as the ability to make informed decisions about issues affecting shared natural resources while balancing cultural perspectives, the economy, public health and the environment.

An environmentally literate citizen:

Understands how natural systems and human social systems work and relate to one another,

Combines this understanding with personal attitudes and experiences to analyze various facets of environmental issues,

Develops the skills necessary to make responsible decisions based on scientific, economic, aesthetic, political, cultural and ethical considerations; and

Practices personal and civic responsibility for decisions affecting our shared natural resources.

Environmental literacy is dependent upon formal education opportunities as well as nonformal education about the environment that takes place in settings such as parks, zoos, nature centers, community centers, youth camps, etc. It is the combination of these formal and nonformal experiences that leads to an environmentally literate citizenry. North Carolina requires an environmentally literate citizenry who make informed decisions about complex environmental issues affecting the economy, public health and safety, and shared natural resources, such as the water, air and land on which life depends.” - North Carolina’s Environmental Literacy Plan

Ways to Get Involved in Environmental Education

Learn more about the organizations and research supporting environmental education. Increase our efforts to support North Carolina’s classroom teachers, naturalists, park rangers, nonformal educators, government employees, students and volunteers by contributing to EENC . Spread the word. Encourage your kids’ teachers to get involved. Volunteer at your local environmental education center. Become an environmental educator. Join our community .

Want a printable copy of this information to share? We have two PDF versions available:

With citations

With clickable links

North American Association for Environmental Education

- About NAAEE

- Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Environmental Education

- Get Involved

- Annual Reports

- Awards for Excellence

- CEE-Change Fellowship

- Certification

- Civic Engagement

- Climate Change Education

- Coalition for Climate Education Policy

- EE 30 Under 30

- E-STEM Initiatives

- Guidelines for Excellence

- Global Initiatives

- Higher Education Accreditation

- Natural Start Alliance

- Research and Evaluation

- Superintendents' EE Collaborative (SEEC)

- Learn About Our Affiliates

- Find Your Affiliate

- Affiliates on eePRO

- NAAEE Newsletters

- Donate Here

- Become a Sustaining Member

- EE Futures Fund

- NAAEE Legacy Society

Education We Need for the World We Want

Environmental education has the power to transform lives and society. It informs, inspires, and influences attitudes. It motivates action. EE is a key tool in expanding the environmental movement and creating healthier and more civically-engaged communities.

About EE and Why It Matters

What Is Environmental Education?

Environmental education (EE) is a process that helps individuals, communities, and organizations learn more about the environment, and develop skills and understanding about how to address global challenges. It has the power to transform lives and society. It informs and inspires. It influences attitudes. It motivates action.

Why Do We Need Environmental Education?

The environment sustains all life on earth. It provides us with nourishment and inspiration. Our economy thrives on a healthy environment. A growing body of research tells us that time spent in nature provides physical and psychological benefits. Our personal and cultural identities are often tied to the environment around us. At the same time, it’s impossible not to be deeply concerned about the unprecedented environmental, social, and economic challenges we face as a global society—from climate change and loss of species and habitats, to declines in civic engagement, decreasing access to nature, a growing gap between the haves and have nots, and other threats to our health, security, and future survival.

Demonstrating the Power of Environmental Education

Environmental education is a process that helps individuals, communities, and organizations learn more about the environment, develop skills to investigate their environment and to make intelligent, informed decisions about how they can help take care of it.

The Tbilisi Definition of Environmental Education: 1977

EE is a learning process that increases people’s knowledge and awareness about the environment and its associated challenges, develops the necessary skills and expertise to address the challenges, and fosters attitudes, motivations, and commitments to make informed decisions and take responsible action. Learn about the history of EE through the History of EE eeLEARN module , exploring some of the milestones and people who have influenced the field.

EE is built on the principles of sustainability, focusing on how people and nature can exist in productive harmony. As the Brundtland Report stated (Our Common Future, 1987), “to create a more sustainable society, we need to determine how to meet the needs of the present without compromising our ability to meet the needs of the future.” The work in this field focuses on building ecological integrity, and environmental health, and creating a fair and just society with shared prosperity.

Key Underpinnings of the Field

The field of EE is characterized by key underpinnings, including a focus on learners of all ages—from early childhood to seniors. It focuses on the importance of experiential, interdisciplinary education, and helping all learners develop problem-solving and decision-making skills, understand how to be a civically engaged citizen, and how to create a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable society. EE also advances key societal issues—from the Next Generation Science Standards to STEM to climate change education.

- Focus on systems thinking

- Lifelong learning: cradle to grave

- Equity & Inclusion

- Focus on sound science

- Built on a sustainability platform

- Interdisciplinary

- Sense of place

- Reflects best practice in education (learner-centered, experiential, and project-based learning)

- Informed decision making

Environmental Education Professionals

Environmental education is a broad umbrella that is focused on creating a more sustainable future using the power of education. In addition to being a process for learning, it is a profession that is focused on using best practice in education to help create societal change to address the social and environmental issues facing society. Environmental educators work in all segments of society. They work with students, teachers, administrators, and school boards to green schools—focusing on curriculum, professional development, schoolyards, and school buildings, and more. They work with businesses to educate managers, employees, and vendors about environmental, health, and economic issues. They are facilitators of citizen science programs to help people understand the scientific process and use the data to help protect species, habitat, communities, and ecological processes. They are professors in universities who train the next generation of teachers, environmental professionals, business leaders, and others. They work with journalists to tell the story about the value of environmental education and with decision makers to advocate for environmental education. They work hand-in-hand with conservation professionals to help engage people and communities in finding solutions to conservation issues—from loss of biodiversity to climate change. And they work with health professionals who educate doctors, nurses, and other health professionals about the critical link between health and environment and how to increase time in nature to address health issues. They are naturalists helping to connect more people to nature and build stewardship values that last a lifetime.

More about environmental education: EE Briefing for Grantmakers Across the Spectrum Guidelines for Excellence Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Special Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Reasons to submit

- About BioScience

- Journals Career Network

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Potentially Offensive Content

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Managing complexity and valuing science, responding to demographic changes, responding to the new “geography of childhood”, activity-based learning, sidestepping the psychology of despair, references cited.

- < Previous

Challenges for Environmental Education: Issues and Ideas for the 21st Century: Environmental education, a vital component of efforts to solve environmental problems, must stay relevant to the needs and interests of the community and yet constantly adapt to the rapidly changing social and technological landscape

Stewart J. Hudson is president of the Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation, 290 Pratt Street, Meriden, CT 06450.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Stewart J. Hudson, Challenges for Environmental Education: Issues and Ideas for the 21st Century: Environmental education, a vital component of efforts to solve environmental problems, must stay relevant to the needs and interests of the community and yet constantly adapt to the rapidly changing social and technological landscape, BioScience , Volume 51, Issue 4, April 2001, Pages 283–288, https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0283:CFEEIA]2.0.CO;2

- Permissions Icon Permissions

As we enter a new century and millennium, environmental educators must come up with new knowledge and techniques that address the demands of a constantly evolving social and technological landscape, while ensuring that environmental education stays relevant to the needs and interests of the community. These challenges to environmental education require that we reexamine the way we do research and train environmental professionals and educators, as well as the way we communicate environmental information to the general public.

Great strides have already been made in strengthening environmental education for the general public. This is particularly true in terms of defining environmental education and its objectives ( Ruskey and Wilkie 1994 ). In the past few years, the North American Association for Environmental Educators has spearheaded an effort to develop mechanisms both to strengthen standards for environmental education and to make it possible to achieve them. A solid base for environmental education already exists. In the United States, there are many leaders in the field, and these individuals have had an extraordinary impact on environmental education. There is also a plethora of organizations and material available for all age groups and most learning situations (see the box on p. 287), which can be incorporated in broad-based environmental education efforts to meet diverse needs. As scientists and educators, we have the opportunity and the responsibility to utilize and expand this resource base.

The way we plan today for public education on the environment will have dramatic effects on the future quality of life. Effective and meaningful environmental education is a challenge we must take seriously if we and future generations are to enjoy the benefits of our natural heritage. This article identifies some of the current and future challenges to environmental education in the United States and offers suggestions on how best to address them. Although some of the examples and education models involve freshwater systems, the concepts behind the educational strategies can be applied to most other environmental settings. Some of the information presented here may be applicable in other countries struggling with the challenges of environmental education.

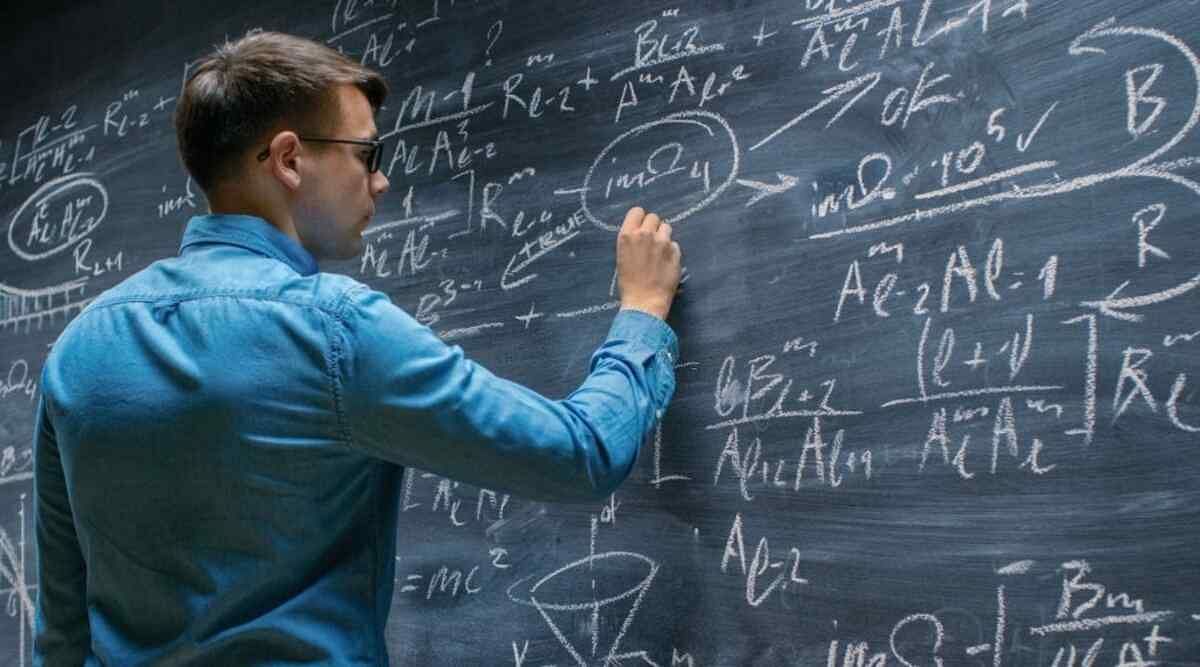

Environmental problems have become increasingly difficult to understand and to evaluate, yet environmental issues are more often expressed in “sound bites” than explained by sound reasoning. Moreover, reasonable treatment of environmental concerns often falls prey to the political agendas of those who have a vested interest in an unsustainable, resource-extractive approach to economic development. The challenge, then, is to express the complexity of modern environmental issues in ways that are understandable and inviting, and at the same time to ensure that science continues to play an important role in explaining and evaluating environmental issues and in forging solutions to environmental problems.

For example, there is a large gap between what members of the general public hear and what they understand about environmental problems related to aquatic resources. Everyone knows that Americans are concerned about safe drinking water. However, a survey conducted by the National Environmental Education and Training Foundation (NEETF) showed that only “about one in four American adults knows that the leading cause of water pollution is surface water running off the land, from farm fields to city streets” ( NEETF 1997 ). In referring to “Consumer Confidence Reports” that will soon be provided by water companies and utilities, NEETF reports that “even if the bill-payer reads the report, its technical nature may be daunting” ( NEETF 1997 ).

Nor does the gap narrow for other environmental issues. Some measure of scientific acuity is necessary for comprehending these issues, and there is some evidence that the United States lags behind other industrialized countries in science and math education. As an article on the “ABCs of Science Education” reports, “Even our best and brightest are falling behind—the top scoring 20% of US eighth graders are taught what seventh graders are taught in high-scoring nations” ( Tibbets 1997–1998. .

Moreover, at times there have been efforts to “dumb down” the existing scientific underpinnings of environmental knowledge as a means of advancing an agenda that depends on an unsustainable, resource-extractive approach to economic development. This movement attacks environmental education almost across the board, claiming that the loss of biological diversity, declining health of aquatic resources, and human-induced climate change, among other issues, are not worth worrying about. The general thrust of these contrarian attacks is that there is no science behind the environmental concerns shared by a majority of the American public; additionally, the argument goes, environmental education materials that fail to point this out are unduly biased ( Manilov and Schwarz 1996–1997 ). Although this anti-ecoeducation movement has abated somewhat, it will always be a critical factor in shaping environmental education in the United States.

Environmental education must teach about science itself and about the use of the scientific method—an important supplement to belief systems and value judgments—to help evaluate and respond to environmental threats. Educational materials that omit the important role of science and the general rules of scientific inquiry are damaging to the field of environmental education.

The need to include science in educational efforts does not, however, excuse educators from the obligation to communicate in an understandable way that invites further inquiry from those who might be intimidated by scientifically complex subjects. The case of Pfiesteria is a good example. When the first reports came out about the effects of Pfiesteria on fish stocks and humans in and around the Chesapeake Bay and coastal North Carolina, this toxic organism quickly became a hot-button issue discussed in the form of sound bites in a variety of media sources. Those who knew the most about the subject (including JoAnn Burkholder, internationally recognized expert on Pfiesteria ) struggled valiantly both to express the problem in understandable terms and to identify areas of certainty and uncertainty. The National Wildlife Federation also became deeply involved in the issue; coverage in the organization's magazine and in activist materials was objective, backed by science, and communicated in understandable terms and, perhaps most important, in ways that invited further inquiry ( Broad 1997 , Carroll 1998 , Davis 1998 , Dolan 1998 ).

This last aspect of the Federation's involvement with the issue—the production of materials that both explain scientific inquiry and provide mechanisms for further exploration—is a critical component of environmental education. Various materials evidence this kind of approach, but two that deserve special mention are the National Wildlife Federation's NatureScope volumes Diving into Oceans and Wading into Wetlands ( Braus et al. 1989a , 1989b ). These publications describe activities that can help sharpen scientific learning skills and provide resources and suggestions for obtaining further information about aquatic resources. An extraordinary array of leading experts in the scientific community contributed to both volumes through the peer review process and editorial comment.

Science has provided the greatest evidence, to date, of the damage we have done and are doing to the planet. The need to rely on science to support environmental education programs and materials continues nonetheless, obligating scientists to learn new skills for communicating and making complex subjects understandable to the public.

Obviously, planning for environmental education must take into account significant demographic changes in the United States. What are those demographic trends, and how will they most likely affect the nature of environmental education? First, minority populations dominate population growth; the number of non-Hispanic whites is expected to begin declining in the third decade of this century. Another noteworthy demographic change, in addition to greater cultural diversity, is that the number of aging but active baby boomers will increase over the next several decades. A third important societal shift concerns the nature of the family—namely, changes in its traditional constitution and in the amount of time that family members spend with one another ( Crispell 1995 , Kate 1998 ).

An increasingly diverse society, larger numbers of older Americans, and family life that is geared around schedules rather than free time all have important implications for environmental education. Clearly, environmental education must be of interest to, and available to, diverse audiences. Fortunately, some pioneering efforts show how this process might be initiated. One of the nation's leading environmental education organizations, the National Audubon Society, has built a partnership with the United Negro College Fund and the CSX Corporation to create a scholarship program for minority students who wish to become more involved in environmental programming ( CSX Corporation 2001 ). The Earth Tomorrow program of the National Wildlife Federation is targeted specifically at inner-city, largely African–American, student populations, and a recent edition of the Federation's National Wildlife Week was issued in both Spanish and English ( Flicker 1998 , Rogers 1998 , Tunstall 1998 ). The Roots & Shoots program of the Jane Goodall Institute has adapted a curriculum packet for diverse audiences with the help of numerous local organizations in Los Angeles with a particular focus on at-risk and culturally diverse communities ( McCarty et al. 1998 ).

Designing programs for diverse audiences is not an easy process. It involves much more than mere linguistic translation, although language is important. It requires the involvement of the potential audiences in program design. Moreover, programs must be designed to be sustainable within the communities they seek to involve.

Other trends in US demographics—the rapidly aging population of the country and the harried nature of family life—also need to be addressed. The Environmental Alliance for Senior Involvement (EASI) takes an interesting approach: It enlists senior citizens as well as young people to monitor the quality of aquatic resources in Pennsylvania and other states by appealing to their commitment to volunteerism and to the environment. (The EASI Web site is shown in the box on p. 287.)

In terms of reaching families, one of the strategies employed by the National Wildlife Federation is to create opportunities for parents and other caregivers and adult family members to interact with children through the NatureLink program, which was developed in conjunction with the Canon Clean Earth Campaign. Often associated with fishing and other uses of aquatic resources, the program has produced Natural Fun, a guide that suggests nature education activities that allow families to spend time together ( NWF 1997 ). What these and other outdoor-oriented programs share is an understanding that the constitution of families and the nature of “family time” have changed. Outdoor education programs in particular must be designed to provide opportunities for families with increasingly crowded schedules to spend time together. Most important, these programs have to be fun and engaging to compete with other demands on families' time, and their outcomes must be both obvious and rewarding to the program participants.

Demographic changes in the United States in the 21st century will dramatically change the potential audience for environmental education. If environmental education keeps pace with this changing audience, the overall environmental movement will benefit by staying relevant to future generations and by inspiring individuals to take action to conserve natural resources and protect the environment. Lessons learned in the United States may well prove useful in the growth of environmental education in other countries as well, particularly those concerning materials and programs that effectively reach ethnically and culturally diverse populations.

In a 1992 survey of fifth and sixth graders in the United States, 9 percent of the children said that they learned environmental information from home; 31 percent reported that they learned from school; and a majority, 53 percent, listed the media as their primary teacher. Such media-inspired children may become fierce in their desire to save condors and whales. In Santa Fe, New Mexico, for example, each May the children of as politically correct a group of yuppie parents as one is likely to find don the costumes of endangered animals for All Species Day and parade proudly through the downtown streets.... Contact with even common wild creatures has become rare for most American children.

The challenge this pattern presents is not to supplant newer information sources but to complement them with a menu of linked opportunities that promote a continuum of experience, as well as learning that incorporates outdoor education and hands-on activities.

In addition to serving the ends of environmental education, making an extra effort to promote outdoor experiences to a generation whose first encounter with a mouse is likely to be with the one sitting next to the computer is important for significant developmental reasons. Mary Rivkin (1995) , an expert in early childhood development and author of The Great Outdoors: Restoring Children's Right to Play Outside, believes that children have to experience nature directly in order to learn and develop in healthy, appropriate ways. The variety and richness of natural settings all contribute more than do manufactured indoor environments to physical, cognitive, and emotional development ( Rivkin 1995 ).

In short, the changed geography of childhood means that environmental education programs must provide a continuum of experiences from online to hands-on. The Animal Tracks program of the National Wildlife Federation ( NWF 2001 ) is one good example. A recently issued kit on water quality issues provides online resources, but it also suggests various activities, including the creation of aquatic habitats at schools that encourage hands-on, inquiry-based learning. This approach does not denigrate the newer sources of information; it merely ensures that they are part of a continuum that incorporates learning in nature as a necessary way of learning about nature. This philosophy is also evident in the programs of the Massachusetts Audubon Society (see the box on page 287), which couples its online and media-focused programming with more hands-on activities, such as those promoted in its Pondwatchers guide, a brochure about aquatic systems in the northeastern United States (Massachusetts Audubon Society n.d.).

This generation of children also gets more knowledge about nature from television documentaries than from actual experience of the natural world. That kind of change in the geography of childhood should not be taken as cause for attacking some incredibly valuable forms of educating people about the environment, including IMAX films, programming by the Discovery Channel and others, and online resources such as Jubilee's Journey, a CD-ROM available from the Jane Goodall Institute. Instead, there is ample opportunity for ensuring that educational materials relating to, say, aquatic resources couple traditional cognitive learning materials with hands-on experience, whether it involves water quality testing, restoration of streamside habitat, or the creation of wetlands as part of a schoolyard habitat project. Two organizations involved in this kind of work are the Izaak Walton League and the National Wildlife Federation.

One of the greatest challenges for education generally is to produce measurable results. Unfortunately, reaching this goal is neither easy nor devoid of the politics of testing and the endless philosophical debates over what constitutes marked increases in learning and knowledge. Environmental education, though not exempt from these issues, provides some exciting opportunities for enhancing learning, sharpening observation and problem-solving skills, and producing measurable outcomes.

A clear understanding of what we are educating our children for will give us guidelines on the structure of educational programs. There is a fair consensus among all involved in debates about educational reform that one of the principal goals of education is to enhance the ability of children to become productive members of society, as well as to advance a variety of skills that are productive for the development of children. It is in teaching children to become responsible and productive members of society that we are most likely to find significant and tangible benefits from environmental education.

In many school systems across the United States, students must devote a certain amount of time to community service as a prerequisite for graduation. This requirement is not something that is added to the learning experience for purely altruistic reasons, but rather because community service is part of the learning-by-doing philosophy that has guided US education for almost a century. Likewise, teaching about the environment is most effective if it incorporates activities that seek to produce tangible results.

For example, a number of organizations, including the Izaak Walton League, the Missouri Conservation Foundation, the Riverwatch Network, and GREEN (see the box on p. 287), have developed programs that involve children and adults in monitoring the environmental quality of streams and other bodies of water. Although testing water quality by itself does not directly enhance the environment, inevitably these programs lead to other results, such as streamside restoration, improved industrial practices, and policy changes, all of which deliver measurable and effective outcomes ( Middleton 1998 ). One very successful and widely used program for stream protection, restoration, and education, sponsored by the Izaak Walton League of America, is called Save Our Streams ( Middleton 2001 ).

Other programs, such as Cascadia Quest, which is based in Seattle, Washington, are even more closely focused on service activities. Indeed, Cascadia Quest students have restored salmon habitat, replanted eroded slopes, worked on urban streams, and made other improvements to water resources in and around the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere in the world. The Roots & Shoots program of the Jane Goodall Institute also is service oriented: It requires participants to undertake activities to protect animals, enhance the environment, and help develop their local community. Activities in these three areas have helped enhance the quality of local aquatic resources on behalf of people, wildlife, and the environment ( Cascadia Quest 1997 ).

This kind of activity-based learning often produces economic as well as environmental benefits. For example, the Campus Ecology program of the National Wildlife Federation published a study entitled “Green Investment, Green Return.” The study lists projects undertaken on college campuses across the United States that both improve the environment and save money. These campus “greening” activities address problems ranging from water conservation to reductions in the use of pesticides and other toxic substances in landscaping and other campus activities. To reiterate, if one of the goals of education is to nurture the growth of productive members of society, then these kinds of programs are most certainly viable and valuable ( Keniry and Lyon 1998 ).

Effective education requires the recognition of appropriate and meaningful strategies to help students discover more about the natural world, assemble information and facts, and solve problems. Detailed analyses are needed to more fully evaluate different learning styles and different areas of knowledge. Howard Gardner, a professor of education at Harvard University, posits several distinct types of intelligence, including one that relates directly to intelligence about the natural world. He therefore asserts the need to create different approaches to evaluate the impact of educational programs on these distinct forms of learning and knowledge.

Problem solving, for example, is an important, requisite objective of the educational process, and research by Gardner and others suggests that hands-on environmental activities are an effective means of enhancing problem-solving skills ( Knox 1995 ). Moreover, William Hammond, an environmental education expert, adds that a new approach to education and action “does not require the abandonment of technology and scientific rationality. It permits the blending of the best of the industrial modern world with the most useful and constructive post-industrial thought. When students are invited to move their education beyond the walls of the classroom and engage in genuine action, they are given the opportunity to synthesize knowledge, skill, and character; to test their preconceptions and misconceptions against real experience; and to learn both to follow and to lead as members of a learning organization” ( Hammond 1997 ).

As Hammond suggests, the positive benefits of hands-on learning can enhance students' ability to become more conversant with the array of new technologies now being developed. There are many exciting and successful programs already in place. The Roots & Shoots program provides recognition to clubs that work on substantial projects in three different areas—protecting the environment, caring for animals, and helping communities. The NatureLink program at the National Wildlife Federation calls for participants to complete an “Earth Pledge,” and the Federation's Schoolyard Habitat program measures its success in terms of the number of schools that create habitats on school grounds.

Environmental educators should embrace the need for results as a particular strength of environmental education, especially those programs that can produce materials and experiences that cover a broad range of hands-on learning. Environmental education can—must—lead from awareness to action. That message should be reflected in program design and implementation, as well as in the way environmental education is defined and valued.

Learning more about the environment generally means learning more about what we have done to the environment rather than what we have done to care for it. Although environmental education certainly requires learning about the resilience of nature, it is the catalog of harm that will seem most evident to educators and students over the next several decades. The danger is that this catalog of harm will contribute to a psychology of despair—a loss of hope for the future and a sense that we as individuals cannot make a difference. The danger of despair is especially true for would-be educators who have been in the environmental trenches fighting for years, even decades.

Without underestimating the magnitude of the environmental challenges that we face globally as well as locally, and while noting the limits to what can be accomplished in the short run, we must realize there are ways to sidestep the psychology of despair. One is to recognize those who are making a difference in the world, especially young people, and to celebrate their accomplishment. Two of the most socially responsible (and profitable) corporations that are doing just that are Stonyfield Farm of Manchester, New Hampshire, and Tom's of Maine. The Planet Protectors program of Stonyfield Farm recognizes the achievement of individuals who have made substantial contributions to environmental protection. Tom's offers a Lifetime Achiever's Award to individuals who benefit the environment.

Another important way to avoid the psychology of despair is to promote the belief that individual responsibility and action can make a difference. Certainly the extent of environmental harm that the world-renowned Jane Goodall has witnessed firsthand over the last 40 years would give her ample excuse to be downcast and pessimistic about the future. Nevertheless, while fully acknowledging the challenges before us, it is her message of hope that is one of the most effective and best remembered parts of her frequent lectures. In public venues around the world, Dr. Goodall demonstrates her point by offering examples of individuals who have made a difference. JoAnn Burkholder is a great example of the kind of person Dr. Goodall cites. Despite threats and intimidation from those who opposed her efforts—agricultural and other interests—Dr. Burkholder uncovered threats to aquatic resources through her codiscovery of Pfiesteria, a deadly bacterium. Burkholder continues to educate people across the country about this dangerous organism and the man-made pollution that allows Pfiesteria to flourish. Dr. Goodall's overall message is one of hope. She offers four forces that provide hope for the future: the power and creativity of the human brain to solve problems; the resiliency of nature once we approach it from a position of respect; the strength and vitality of young people around the world; and the indomitable human spirit ( Goodall 1999 ).

To become involved in respecting nature and protecting the environment over the long term, people need to have a sense of hope and gratification from environmental education. Building programs that merely catalog harm without advancing the sense that accomplishments can be made will not offer the kind of fun and enriching learning environment that creates a sustainable commitment to environmental protection. While the study of nature would be incomplete without discussing the threats to the natural world, an appreciation of nature should not be lacking in environmental education programs. It is teaching about the miracles of the natural world, more than anything else, that will engender a sustainable and creative learning environment.

Although great strides have been made in protecting aquatic resources, human population growth and industrial use will continue to pose significant challenges to the protection of these basic resources. While environmental education is sometimes characterized as “soft” and gets less attention than other aspects of environmental protection, it is through environmental education that future environmental advocates and problem solvers are created. To generate new leaders in the environmental field over the new century, and to foster the general public's knowledge and concern for the environment, environmental education should recognize and begin responding effectively to several major challenges. These include changes in demographics and experience, effective integration of newer sources of information with experiential learning opportunities, the effective communication of environmental issues to the public, and the avoidance of the psychology of despair.

Braus J . 1989a. Diving into Oceans. Vienna (VA): National Wildlife Federation.

Braus J . 1989b. Wading into Wetlands. Vienna (VA): National Wildlife Federation.

Broad WJ. . 1997. Battling the cell from hell. National Wildlife Magazine (August–September): 10.

Carroll G. . 1998. Are our coastal waters turning deadly? National Wildlife Magazine (April–May): 42.

Cascadia Quest . 1997. A World of Young Leaders in King County. Seattle (WA): Cascadia Quest.

Crispell D. . 1995. Generations to 2025. American Demographics (April).

CSX Corporation . 2001. CSX Scholars Program. (20 Mar 2001; www.csx.com/aboutus/employment/scholars ).

Davis C. . 1998. Pollution Paralysis. Vienna (VA): National Wildlife Federation.

Dolan K. . 1998. Saving Our Watersheds. Vienna (VA): National Wildlife Federation.

Flicker JD. . 1998. Building diversity at Audubon. Audubon (March–April).

Goodall J. . 1999. Reason for Hope. New York: Warner Books.

Hammond WF. . 1997 . Educating for action. Green Teacher . 50 : 7

Kate TN. . 1998. Two careers, one marriage. American Demographics (April).

Keniry J Lyon J. . 1998. Green Investment, Green Return. Vienna (VA): National Wildlife Federation.

Knox RA. . 1995. Brainchild. Boston Globe Magazine, 5 Nov, p. 23.

Manilov M Schwarz T. . 1996–1997. An assault on eco-education. Earth Island Journal (winter): 36.

McCarty J . 1998. Roots & Shoots LA. Washington (DC): Jane Goodall Institute.

Massachusetts Audubon Society. n.d . Pondwatchers: Guide to Ponds and Vernal Pools of Eastern North America. Lincoln (MA): Massachusetts Audubon Society.

Middleton JV. . 1998. Stream Doctor Project: Community Driven Stream Restoration. Presentation at workshop on Environmental Education Outreach for Aquatic Resource Conservation, ESA–ASLO meeting; June 1998; St. Louis, MO.

Middleton JV. . 2001 . The Stream Doctor Project: Community-driven stream restoration. BioScience . 51 : 293 – 296 .

Nabham GP Trimble S. . 1994. The Geography of Childhood: Why Children Need Wild Places. Boston (MA): Beacon Press.

[NEETF] National Environmental Education and Training Foundation . 1997. Annual Report. Washington (DC): NEETF.

[NWF] National Wildlife Federation . 1997. Natural Fun. Vienna (VA): National Wildlife Federation.

[NWF] National Wildlife Federation . 2001. Animal Tracks. (21 Mar 2001; www.nwf.org/animaltracks/index.html ).

Rivkin MS. . 1995. The Great Outdoors: Restoring Children's Right to Play Outside. New York: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Rogers CS. . 1998. Earth tomorrow: Meeting the urban challenges. Michigan Natural Resources Magazine (May–June).

Ruskey A Wilkie R. . 1994. Promoting Environmental Education. Stevens Point (WI): National Wildlife Federation and the University of Wisconsin Stevens Point Press.

Tibbets J. . 1997–1998 . The ABCs of science education. Coastal Heritage, South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium . 12 : 4

Tunstall M. . 1998. 1998. Nature's Web: Caring for the Land. Vienna (VA): National Wildlife Federation.

Among popular Web sites for information on environmental education are the following:

www.janegoodall.org

www.nwf.org

www.wwf.org

www.earthforce.org

www.naaee.org

www.easi.org

www.massaudubon.org

www.riverwatch.org

www.igc.apc.org/green

Author notes

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1525-3244

- Copyright © 2024 American Institute of Biological Sciences

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

New Tools for Environmental Protection: Education, Information, and Voluntary Measures (2002)

Chapter: 9 perspectives on environmental education in the united states.

Below is the uncorrected machine-read text of this chapter, intended to provide our own search engines and external engines with highly rich, chapter-representative searchable text of each book. Because it is UNCORRECTED material, please consider the following text as a useful but insufficient proxy for the authoritative book pages.

9 Perspectives on Environmental Education in the United States John Ramsey and Harold R. Hungerford T his chapter addresses the question of what environmental education (EE) is, explores some of its critical challenges, and describes an effective, long-standing curricular approach to environmental education and its re- search implications. OVERVIEW OF ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Letâs begin with the concept of environmental education. According to Stapp (1969), environmental education is aimed at producing a citizenry that is knowl- edgeable about the biophysical environment and its associated problems, aware of how to solve these problems, and motivated to work toward their solution. An important element implied by this definition is a problem-solving approach, per- haps characterized as informed decision making in a democratic society at both personal and societal levels. Disinger (1983), Harvey (1977), Simmons (2000), and others state a similar conceptualization. This concept is congruent with the progressive philosophy of American education, a tenet of which is the fostering of citizenship participation in a democracy. The progressive, âresponsible citizenâ approach to environmental education is taken by the North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE), the largest environmental education organization in the United States. This organization incorporated the problem-solving approach into a national pol- icy document, Excellence in Environmental Education: Guidelines for Learning (NAAEE, 1999a). This document, which operationalized critical knowledge, skills, and dispositions, can be viewed as the fieldâs standards. Modeled on other recent national education policy guidelines, such as the mathematics and 147

148 PERSPECTIVES ON ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES science education standards, it draws heavily not only on the work of the Amer- ican authors cited earlier but also on two major international policy documents, the Belgrade Charter (1975) and the Tbilisi Declaration (1977). Both of these international policy documents were developed as a result of the United Nationsâ interest in human activity and the environment. A significant amount of controversy remains about the definition of envi- ronmental education. Some writers express the need for an ecology-based ap- proach rather than the problem-solving one implicit in the technology-capitalism dimension of Western society. They claim that ecology must be the basis for human activity and that ecological parameters cannot simply be factored into an economic equation of costs and benefits. European writers and others take a postmodern approach, emphasizing individual development and opposing a sys- temic, outcomes-based approach. These writers decry top-down, prescriptive policies and behavior-based curricula. Disinger (1983) provides a more com- plete treatment of the definitional aspects of environmental education. Regard- less of definition, the following characteristics appear to be essential elements in most environmental education perspectives. Environmental education ⢠is based on knowledge of ecology and social systems, drawing on disci- plines in the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities; ⢠reaches beyond biological and physical phenomena to consider social, economic, political, technological, cultural, historic, moral, and aesthetic aspects of environmental issues; ⢠recognizes that the understanding of feelings, values, attitude, and per- ceptions at the center of environmental issues is essential to analyzing and resolving these issues; and ⢠emphasizes critical thinking and problem-solving skills needed for in- formed, reasoned personal decisions and public action (Disinger and Monroe, 1994). The major challenges to effective environmental education in the United States are interrelated, and so there is no significance implied by the discussion order that follows. One major challenge for the field is that it lacks a formal niche in the K-12 curriculum, suggesting that it is not in the mainstream of American education. This situation arises in part from the decentralized nature of the U.S. school system, with each state and school district declaring its own independent curriculum. It is also related to the multidisciplinary nature of the field, a characteristic that makes it difficult for environmental education to fit into a disciplinary curricular system that is responding more and more to âbasics- onlyâ demands for accountability rather than to the broad dimensions of a liberal, general education. Environmental education is either ignored or viewed by main- stream educators as a supplement to the curriculum that must justify its inclusion by enriching other subjects, such as history and science. In our view, the role of

JOHN RAMSEY AND HAROLD R. HUNGERFORD 149 environmental education in American education will remain marginal unless a K-16 curricular niche is established for it. It is not surprising that todayâs teachers are not prepared to teach environ- mental education. Neither the formal education curricula nor teachersâ profes- sional training experiences have prepared them for this instructional challenge. Very little environmental education is required of preservice teachers (i.e., those in training who have not yet begun their teaching careers), and there is limited organizational infrastructure for it at the state level. Fewer than 15 percent of preservice teachers take a formal EE course, and state-level data are equally slim. Kirk et al. (1993) offer perhaps the most recent state-level overview. The current teaching force lacks training in environmental education, and there is no provision for it in the preservice training of new teachers or in ongoing in- service training. Most EE curricular materials were designed as supplemental lessons to be infused episodically into a given curriculum (for instance, Project WILD, Project Learning Tree). A plethora of print and video materials of highly variable quality is offered by many private and public curriculum developers. Some of these materials have been described as biased, inaccurate, incomplete, or propagandiz- ing by both critics and supporters of environmental education. In the face of this criticism, NAAEE has developed a set of guidelines for developing, selecting, and evaluating materials (NAAEE, 1999b). The guidelines address fairness and accuracy, balanced viewpoints, depth of understanding, critical and creative thinking, and civic responsibility, as well as other instructional criteria. Major initiatives are needed to evaluate existing curricula to ensure that the highest quality products are recommended. Despite attempts to upgrade the quality of EE materials, conservative factions in the United States continue to criticize materials that are related to specific issues (e.g., the greenhouse effect). Instead they promote a version of environmental science that is âfact based.â For exam- ple, the study of eutrophication as a conceptâmeaning the process of a body of waterâs becoming rich in nutrients but deficient in oxygenâis acceptable to them, but the examination of eutrophication as a function of nonpoint pollution in Galveston Bay, Texas, and of its sources, is not acceptable. A MODEL CURRICULUM One environmental education curriculum program, called Investigating and Evaluating Environmental Issues and Actions (IEEIA), has been developed over time, accumulating an extensive research and evaluation base (Hungerford et al., 1996; Ramsey, 2000; Winther, 2000). It meets the NAAEE guidelines and aug- ments many of the outcomes identified by other discipline standards, such as national science standards. It is structured for insertion (as opposed to supple- mental infusion) into the curriculum. And it has been the target of numerous research and evaluation publications.

150 PERSPECTIVES ON ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES Its initial development was as a one-semester curriculum designed for use at the middle school level. Subsequently, it was published in two themes, environ- mental and science-technology-society, and in two formats, modular and case study. These changes expanded the initial programâs use from Grade 5 through high school. The case study programs use the same instructional structure as the initial IEEIA program but are built around specific topics, including coastal marine issues, endangered species issues, and solid waste issues. The following discussion focuses on the environmental theme and the modular format. The model grew out of one teacherâs desire to allow his junior high school students both to investigate environmental issues of interest to them and to enable them to develop the skills needed to conduct such an issue-based investigation. Over the years the model has been refined as more and more teachers and students have provided input and as more research information has become avail- able. In addition, it became apparent early in the development process that a component of citizenship participation (i.e., citizen action) was needed because students often wished to do something about the issues they investigated after completing their research. Today, the published versions of the curriculum re- flect generally accepted instructional goals beginning with background informa- tion that leads to issue awareness, issue investigation and evaluation, and citizen- ship participation/issue resolution. The curriculum is organized into a series of six modules or chapters. The modules are interdisciplinary in nature and introduce students to the characteris- tics of issues, the skills needed for obtaining and processing information, the skills needed for analyzing and investigating issues, and the skills needed by responsible citizens for issue resolution. The following description provides a brief overview of each module. Module I: Environmental Problem Solving: This module contains lessons using actual environmental issues to develop the skills necessary to understand and analyze issues independently. These skills include discriminating among the interrelationships of events, problems, and issues, as well as understanding the role of beliefs and values in issues. Issue analysis, the skill of unpacking the critical components of an issue, is introduced and practiced. The concept of interaction, that is, the interrelatedness of human activities and the natural world, is also introduced, demonstrated, and applied. Rather than focus on a particular body of information or ideas, these lessons focus on the skills necessary for students to analyze the complexity of environmental issues. Module II: Getting Started on Issue Investigation: These lessons begin the skills necessary to start an issue investigation. Students identify issues, write research questions, and learn how to obtain information from secondary sources and how to compare and evaluate information sources. These lessons focus on finding, analyzing, and evaluating secondary source information about issues. Module III: Using Surveys, Questionnaires, and Opinionnaires in Environ- mental Investigations: Students learn how to obtain information using primary

JOHN RAMSEY AND HAROLD R. HUNGERFORD 151 methods of investigation. Initially, they learn how to develop surveys, question- naires, and âopinionnaires.â Subsequently, they learn sampling techniques, how to administer data collection instruments, and how to record collected data. These lessons focus on social science inquiry skills in the context of environ- mental beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Module IV: Interpreting Data From Investigations: Students learn how to draw conclusions, make inferences, and formulate recommendations. They also learn how to produce and interpret graphs. These lessons prepare students to interpret and communicate findings using data related to environmental issues. Module V: Investigating an Environmental Issue: Students autonomously select and investigate an issue. This process involves the application and synthe- sis of skills learned thus far. The modelâs developers recommend that studentsâ investigations be reported back to their peers in formal classroom presentations. In this section of the program, students âtake over,â undertaking an inquiry into an authentic environmental issue approved and facilitated by the teacher. Module VI: Environmental Action Strategies: Students learn the major methods of citizenship action, analyze the effectiveness of individual versus group action, and develop issue resolution action plans. This action plan is evaluated against a set of predetermined criteria designed to assess the social, cultural, and ecological implications of citizenship actions. Finally, the action plan may be implemented if the students wish. In this section students use their investigation data to formulate a plan for possible participation as a citizen in the solution of the issue under investigation. The recommended outcomes of the program are to enable students to ⢠inquire successfully into ill-defined problems, ⢠demonstrate responsible citizenship in the community, ⢠interact successfully with environmental issues, ⢠use higher-order thinking skills, and ⢠think reflectively in terms of alternative positions related to issues. The foundation of the program is the preparation for and undertaking of an authentic environmental investigation on the part of a student or a small group of students. Its structure provides a framework for teachers and students to manage complex intellectual activities. It is important to note that the most powerful educational experiences for students result from projects for investigation that they choose in their local community or region. IEEIA has its roots in a variety of philosophical perspectives, beginning with John Dewey, who wrote at length on instructional models that reflect the democratic process and the scientific method. A number of eminent educators who followed Dewey either supported the same notion or independently arrived at a similar philosophy of education. Among these were Kilpatrick (progressive

152 PERSPECTIVES ON ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES education), Counts (social problem solving and reconstructionism), and Hullfish and Smith (reflectivity). Curricular approaches such as IEEIA are structured to help learners under- stand that democracy for a social group involves the investigation of problems and the development of solutions. Furthermore, this model provides for an attempt at issue resolution by having learners choose a desired method for help- ing resolve the issue (i.e., an action plan) and subsequently evaluate that method. In these ways, this model appears to reflect progressivism quite well. And, given that studentsâ action plans often call for some form of social reform, the model carries with it characteristics associated with reconstructionism as well. RESEARCH ABOUT ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIOR The previous discussion noted that problem solving in terms of personal and social environmental decision making is a critical goal of environmental educa- tion. Given this, letâs look at what is known about responsible environmental behavior. A number of studies of adults have been done from an environmental education perspective that offer insight into the relevant psychological attributes (Hines et al., 1986/1987; Sia et al., 1985/1986; Sivek, 1989/1990; Lierman, 1995; Marcinkowski, 2000; Volk and McBeth, 2000; Zelezny, 2000). (Studies from other perspectives are discussed elsewhere in this volume: Schultz, Chapter 4; Lutzenhiser, Chapter 3; Thøgerson, Chapter 5; Stern, Chapter 12.) Hines et al. (1986/1987) conducted a meta-analysis of research on responsible environmen- tal behavior, reviewing studies from a variety of fields and using statistical pro- cedures to determine the strength of the relationship between responsible envi- ronmental behavior and associated variables. Positive correlations were found for verbal commitment, locus of control, attitude, personal responsibility, knowl- edge, education level, income, and economic orientation. Using Hinesâ findings, Sia et al. (1985/1986) studied the predictors of environmental behavior in two populations of adults, one environmentally active and the other environmentally inactive. Siaâs prediction model was based on eight variables, six of which were determined to be significant using regression analysis procedures and which accounted for 52 percent of the variance. The findings indicated that skill in using action strategies, environmental sensitivity, and knowledge of environ- mental action strategies accounted for the majority of the variance. Siaâs find- ings were replicated by Sivek (1989/1990) and extended by Marcinkowski (2000) and Lierman (1995). Thus, the research indicates that responsible environmental behavior is associated with the following variables: ⢠Environmental sensitivity (i.e., feelings of comfort in and empathy to- ward natural areas), ⢠Knowledge of ecological concepts, ⢠Knowledge of environmental problems and issues,

JOHN RAMSEY AND HAROLD R. HUNGERFORD 153 ⢠Skill in identifying, analyzing, investigating, and evaluating environmen- tal problems and solutions, ⢠Beliefs and values (i.e., beliefs are what individuals hold to be true, and values are what they hold to be important regarding problems/issues and alternative solution/action strategies), ⢠Knowledge of environmental action strategies (i.e., consumerism, politi- cal action, persuasion, legal action, and physical actions), ⢠Skill in using environmental action strategies, and ⢠Internal locus of control (i.e., the belief that by working alone or with others an individual can influence or bring about the desired outcomes). Hungerford and Volk (1990) used these variables to generate a model of responsible environmental behavior for environmental educators. Their model contains all the variables identified in the previous research, but the terms âown- ership,â âempowerment,â and âentry-levelâ were added as category descriptors indicating the relationship of the variables to IEEIA instruction. Ownership refers to a construct of factors associated with personal knowledge and affect about environmental issues. Empowerment refers to a construct of factors asso- ciated with a sense of efficacy about issue solutions. Entry-level refers to factors that could be thought of as prior knowledge and dispositions (see Figure 9-1). This discussion reflects the attempts of environmental educators and re- searchers to understand psychological and other factors associated with respon- sible environmental behavior. These findings were used as a reference frame- work in the design of the IEEIA curriculum. Additional research was then undertaken to determine the extent to which the key variables associated with responsible environmental behavior were affected by IEEIA instruction. The following section presents these studies. RESEARCH ABOUT IEEIA Eleven studies have examined the effects of IEEIA instruction in middle- grade settings: Ramsey et al. (1981), Klingler (1982), Volk and Hungerford (1981), Ramsey (1987), Ramsey (1993), Holt (1988), Bluhm et al. (1995), Blu- hm and McBeth (1996), Withrow (1988), Simpson (1991), and Culen and Volk (2000). All these studies reported statistically significant, positive differences in responsible environmental behavior as a result of instruction, and many reported positive increases in the associated variables. For example, Ramsey et al. (1981) compared IEEIA-based instruction with environmental awareness and control treatments in Grade 8. He reported positive results on two outcome variables, knowledge of action and responsible environmental behavior. Three years later, Ramsey conducted a followup study of the students involved in the original study. Graduate students conducted double-blind interviews with students in- volved in all three groups. The graduate students identified all the subjects

154 PERSPECTIVES ON ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES Entry-level Ownership Empowerment C variables variables variables I T I Z Major variables Major variables Major variables E N Environmental In-depth knowledge Knowledge of and S sensitivity about issues skill in using H environmental I Personal investment action strategies P in issues and the environment Locus of control B (Expectancy of E reinforcement) H Intention to act A V I O Minor variables Minor variables Minor variables R Knowledge of Knowledge of the In-depth ecology consequences of knowledge behavior - both about issues Androgyny positive and negative Attitudes Personal commitment toward to issue resolution pollution, technology, and economics FIGURE 9-1 Major and minor variables involved in environmental citizenship behavior. participating in the IEEIA treatment and found higher levels of responsible envi- ronmental behavior in the IEEIA group, despite the absence of subsequent in- structional reinforcement during the ensuing three-year period. One variable, environmental sensitivity, was not found to be affected by IEEIA treatment in any of the studies. Environmental sensitivity focuses on attributes that provide an individual with an empathetic view of the environment. Sensitivity research (e.g., Peterson, 1982; Sward and Marcinkowski, 2000; Tan- ner, 1980) strongly indicates that environmental sensitivity is one of the major precursors to environmental behavior. It seems to develop at an early age, when individuals experience pristine outdoor settings with adults who are important to them. Thus, it would be surprising if IEEIA, a formal classroom instructional treatment, could influence environmental sensitivity. What is important for en- vironmental educators are the findings that IEEIA can foster responsible envi- ronmental behavior as well as gains in many of the allied factors.

JOHN RAMSEY AND HAROLD R. HUNGERFORD 155 In summary, research on IEEIA shows that for instruction to be effective, five elements are necessary. Students should have 1. Sound problem identification skills: They should be able to identify problems that are important to them in the communities or regions in which they live (Volk and Hungerford, 1981). 2. A degree of environmental sensitivity: Sensitivity is critical as a precur- sor to behavior. And although it may be possible, it is not easy for the formal classroom to accomplish this (Peterson, 1982; Sward and Marcinkowski, 2000; Tanner, 1980). 3. Issue investigation and evaluation skills: The ability to investigate and subsequently to evaluate issues runs throughout much of the research discussed in this chapter. It would be hard to tease out the precise com- ponents (in a research sense), but we know that students must be able to effectively evaluate important issues before they can make intelligent decisions about what to do about them. It also appears that a key element in the concept of ownership is personal involvement by students in issues under investigation (Sia et al., 1985/1986; Hines, 1986/1987; Marcinkowski, 2000; Ramsey, 1987, 2000; Ramsey et al., 1981). 4. Knowledge of and perceived skill in the use of citizenship action strate- gies: These skills include persuasion, political action, consumerism and the variables show up over and over again in one form or another in a great preponderance of the research discussed here. Also, these variables may well be the easiest to deal with in the classroom. How valuable they would be in and of themselves, however, without the framework of issue investigation, is unclear. It is hypothesized that there is a synergistic effect here, and the Klingler (1982) research indicates rather strongly that both are needed (Sia et al., 1985/1986; Hines et al., 1986/1987; Marcinkowski, 2000; Ramsey, 1993, 2000; Ramsey et al., 1981). 5. An internal locus of control: Locus of control is a key element in the concept of empowerment. Knowledge of action strategies without a con- comitant feeling that the action will result in something positive probably wonât get the job done. So opportunities must be provided that give students a feeling of success (even though we know that success is not met at every turn in citizenship roles). The teacher is a powerful force in helping students make good citizenship decisions, helping them find suc- cess on one hand and salving their defeats on the other (Sia et al., 1985/ 1986; Hines et al., 1986/1987; Marcinkowski, 2000). In the future, other researchers may find that variables left out of the list above should have been included. It may be that other variables that show signif- icant implications may operate only with certain populations under certain con- ditions. And some may be related to the ones listed above, such as knowledge of

156 PERSPECTIVES ON ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES issues, verbal commitment to take action, beliefs about and attitudes toward pollution and technology, a sense of personal commitment, and attitudes toward economics. SOME SUGGESTIONS It is important to remember that environmental sensitivity needs to be initi- ated at an early age. Because this is a difficult attribute for the formal classroom situation to influence, it may be the most difficult to achieve. Classroom teach- ers canât turn learners into family campers, trappers, hunters, fishers, hikers, and people associated with other sensitivity-building avocations. Of course, the school can sponsor outdoor activities, but can it provide them in a dimension designed specifically to promote sensitivity? Remember, the outdoor activities reported by sensitive individuals focus largely on long-term experiences in rela- tively pristine environments. And these activities are done either on an individ- ual basis or with one or two close associates. The class field trip may not be an appropriate vehicle. However, it may be possible for the school to accommodate some of these experiences by planning activities that take place in relatively small groups and in relatively pristine environments at times that can maximize at least a modicum of awe and wonder, that is, sincere appreciation. And there must be many such experiences. Perhaps the best opportunity that the school has for achieving sensitivity is to combine high-quality outdoor activities with high-quality role models. Teach- ers should themselves demonstrate a high level of sensitivity, be able to commu- nicate this sensitivity to learners, and be willing to lead students to aesthetic environmental experiences via books, television, and other media, along with outdoor experiences. Beyond sensitivity, a number of behavior-related attributes can be influ- enced by planning for instruction that eventually involves learners in the investi- gation and resolution of issues. Young children can receive instruction on envi- ronmental issues through what is called the extended case study. The traditional case study deals with issues at a basic level of awareness. The extended case study is divided into five components: 1. A carefully selected issue topic around which a case study can be devel- oped, such as municipal solid waste disposal, a locally endangered spe- cies, land use management in the community/region, air/water/aesthetic pollution, loss of wetlands, forest fire management, preservation of eco- logically important plant/animal communities, and population growth; 2. Science content, which serves as prerequisite knowledge to understand- ing the scientific nature of a chosen issue; 3. Issue awareness, which focuses on the anatomy of that issue (the players

JOHN RAMSEY AND HAROLD R. HUNGERFORD 157 involved and their positions, beliefs, and values), the history of the issue, and possible solutions and impediments to them; 4. Some aspect of issue investigation, which gets learners involved in data collection regarding that issue (e.g., surveys, questionnaires, opinion- naires, interviews with key players), and 5. Citizenship skills (strategies such as political action and consumerism) that can be used to help resolve the issue coupled with an action plan that is developed cooperatively by the students and teachers and implemented if desired. Older students, middle school and higher, should receive both case study instruction (at a more sophisticated level) and IEEIA instruction. With this strategy, teachers guide students through an introduction to issues, identifying problems, analyzing issues, using primary and secondary sources to obtain infor- mation about issues, recording and interpreting collected data, and demonstrat- ing citizenship strategies used in society for the remediation of issues. Major activities in this strategy include allowing the students to choose an issue of interest, guiding them in investigating and evaluating it, and reporting the find- ings to peers. The issue investigation is followed by the development of an action plan for helping to remediate that issue; it can be implemented or not, depending on the attitude of the student and judgment of the teacher. It should be stressed that behavior-directed instruction needs to be articulat- ed across grade levels. There is some evidence (not reported in this chapter) that the behaviors sought will tend to erode unless there is periodic reinforcement across grade levels. This erosion is not complete, but students, as they grow older and receive no reinforcement, tend to back away from citizenship behavior as they lose teacher support and a social support system. Similarly, the skills associated with responsible citizenship behavior should be developed across sub- ject areas with a number of content specialists (such as science, social studies, language arts, and home economics) working cooperatively using a team-teach- ing/infusion approach. Whether the school should fulfill the role of change agent in society depends entirely on the perspectives held by those making instructional decisions. How- ever, many educators firmly believe that âteaching about somethingâ will influ- ence behavior. If this were absolutely true, then everyone would vote; no one would contract a venereal disease; everyone would be scientifically literate; the average citizen would love classical literature; manâs inhumanity to man would be diminished or absent; no teenager would have an unwanted pregnancy; all laws would be respected; no animals or plants would be endangered; and people would not smoke. The same is probably true for citizenship responsibility re- garding the environment. Environmental educators have long argued for the importance of making people aware of environmental issues. But researchers