Narrative Analysis 101

Everything you need to know to get started

By: Ethar Al-Saraf (PhD)| Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to research, the host of qualitative analysis methods available to you can be a little overwhelming. In this post, we’ll unpack the sometimes slippery topic of narrative analysis . We’ll explain what it is, consider its strengths and weaknesses , and look at when and when not to use this analysis method.

Overview: Narrative Analysis

- What is narrative analysis (simple definition)

- The two overarching approaches

- The strengths & weaknesses of narrative analysis

- When (and when not) to use it

- Key takeaways

What Is Narrative Analysis?

Simply put, narrative analysis is a qualitative analysis method focused on interpreting human experiences and motivations by looking closely at the stories (the narratives) people tell in a particular context.

In other words, a narrative analysis interprets long-form participant responses or written stories as data, to uncover themes and meanings . That data could be taken from interviews, monologues, written stories, or even recordings. In other words, narrative analysis can be used on both primary and secondary data to provide evidence from the experiences described.

That’s all quite conceptual, so let’s look at an example of how narrative analysis could be used.

Let’s say you’re interested in researching the beliefs of a particular author on popular culture. In that case, you might identify the characters , plotlines , symbols and motifs used in their stories. You could then use narrative analysis to analyse these in combination and against the backdrop of the relevant context.

This would allow you to interpret the underlying meanings and implications in their writing, and what they reveal about the beliefs of the author. In other words, you’d look to understand the views of the author by analysing the narratives that run through their work.

The Two Overarching Approaches

Generally speaking, there are two approaches that one can take to narrative analysis. Specifically, an inductive approach or a deductive approach. Each one will have a meaningful impact on how you interpret your data and the conclusions you can draw, so it’s important that you understand the difference.

First up is the inductive approach to narrative analysis.

The inductive approach takes a bottom-up view , allowing the data to speak for itself, without the influence of any preconceived notions . With this approach, you begin by looking at the data and deriving patterns and themes that can be used to explain the story, as opposed to viewing the data through the lens of pre-existing hypotheses, theories or frameworks. In other words, the analysis is led by the data.

For example, with an inductive approach, you might notice patterns or themes in the way an author presents their characters or develops their plot. You’d then observe these patterns, develop an interpretation of what they might reveal in the context of the story, and draw conclusions relative to the aims of your research.

Contrasted to this is the deductive approach.

With the deductive approach to narrative analysis, you begin by using existing theories that a narrative can be tested against . Here, the analysis adopts particular theoretical assumptions and/or provides hypotheses, and then looks for evidence in a story that will either verify or disprove them.

For example, your analysis might begin with a theory that wealthy authors only tell stories to get the sympathy of their readers. A deductive analysis might then look at the narratives of wealthy authors for evidence that will substantiate (or refute) the theory and then draw conclusions about its accuracy, and suggest explanations for why that might or might not be the case.

Which approach you should take depends on your research aims, objectives and research questions . If these are more exploratory in nature, you’ll likely take an inductive approach. Conversely, if they are more confirmatory in nature, you’ll likely opt for the deductive approach.

Need a helping hand?

Strengths & Weaknesses

Now that we have a clearer view of what narrative analysis is and the two approaches to it, it’s important to understand its strengths and weaknesses , so that you can make the right choices in your research project.

A primary strength of narrative analysis is the rich insight it can generate by uncovering the underlying meanings and interpretations of human experience. The focus on an individual narrative highlights the nuances and complexities of their experience, revealing details that might be missed or considered insignificant by other methods.

Another strength of narrative analysis is the range of topics it can be used for. The focus on human experience means that a narrative analysis can democratise your data analysis, by revealing the value of individuals’ own interpretation of their experience in contrast to broader social, cultural, and political factors.

All that said, just like all analysis methods, narrative analysis has its weaknesses. It’s important to understand these so that you can choose the most appropriate method for your particular research project.

The first drawback of narrative analysis is the problem of subjectivity and interpretation . In other words, a drawback of the focus on stories and their details is that they’re open to being understood differently depending on who’s reading them. This means that a strong understanding of the author’s cultural context is crucial to developing your interpretation of the data. At the same time, it’s important that you remain open-minded in how you interpret your chosen narrative and avoid making any assumptions .

A second weakness of narrative analysis is the issue of reliability and generalisation . Since narrative analysis depends almost entirely on a subjective narrative and your interpretation, the findings and conclusions can’t usually be generalised or empirically verified. Although some conclusions can be drawn about the cultural context, they’re still based on what will almost always be anecdotal data and not suitable for the basis of a theory, for example.

Last but not least, the focus on long-form data expressed as stories means that narrative analysis can be very time-consuming . In addition to the source data itself, you will have to be well informed on the author’s cultural context as well as other interpretations of the narrative, where possible, to ensure you have a holistic view. So, if you’re going to undertake narrative analysis, make sure that you allocate a generous amount of time to work through the data.

When To Use Narrative Analysis

As a qualitative method focused on analysing and interpreting narratives describing human experiences, narrative analysis is usually most appropriate for research topics focused on social, personal, cultural , or even ideological events or phenomena and how they’re understood at an individual level.

For example, if you were interested in understanding the experiences and beliefs of individuals suffering social marginalisation, you could use narrative analysis to look at the narratives and stories told by people in marginalised groups to identify patterns , symbols , or motifs that shed light on how they rationalise their experiences.

In this example, narrative analysis presents a good natural fit as it’s focused on analysing people’s stories to understand their views and beliefs at an individual level. Conversely, if your research was geared towards understanding broader themes and patterns regarding an event or phenomena, analysis methods such as content analysis or thematic analysis may be better suited, depending on your research aim .

Let’s recap

In this post, we’ve explored the basics of narrative analysis in qualitative research. The key takeaways are:

- Narrative analysis is a qualitative analysis method focused on interpreting human experience in the form of stories or narratives .

- There are two overarching approaches to narrative analysis: the inductive (exploratory) approach and the deductive (confirmatory) approach.

- Like all analysis methods, narrative analysis has a particular set of strengths and weaknesses .

- Narrative analysis is generally most appropriate for research focused on interpreting individual, human experiences as expressed in detailed , long-form accounts.

If you’d like to learn more about narrative analysis and qualitative analysis methods in general, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach blog here . Alternatively, if you’re looking for hands-on help with your project, take a look at our 1-on-1 private coaching service .

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

Thanks. I need examples of narrative analysis

Here are some examples of research topics that could utilise narrative analysis:

Personal Narratives of Trauma: Analysing personal stories of individuals who have experienced trauma to understand the impact, coping mechanisms, and healing processes.

Identity Formation in Immigrant Communities: Examining the narratives of immigrants to explore how they construct and negotiate their identities in a new cultural context.

Media Representations of Gender: Analysing narratives in media texts (such as films, television shows, or advertisements) to investigate the portrayal of gender roles, stereotypes, and power dynamics.

Where can I find an example of a narrative analysis table ?

Please i need help with my project,

how can I cite this article in APA 7th style?

please mention the sources as well.

My research is mixed approach. I use interview,key_inforamt interview,FGD and document.so,which qualitative analysis is appropriate to analyze these data.Thanks

Which qualitative analysis methode is appropriate to analyze data obtain from intetview,key informant intetview,Focus group discussion and document.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Narrative Writing: A Complete Guide for Teachers and Students

MASTERING THE CRAFT OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narratives build on and encourage the development of the fundamentals of writing. They also require developing an additional skill set: the ability to tell a good yarn, and storytelling is as old as humanity.

We see and hear stories everywhere and daily, from having good gossip on the doorstep with a neighbor in the morning to the dramas that fill our screens in the evening.

Good narrative writing skills are hard-won by students even though it is an area of writing that most enjoy due to the creativity and freedom it offers.

Here we will explore some of the main elements of a good story: plot, setting, characters, conflict, climax, and resolution . And we will look too at how best we can help our students understand these elements, both in isolation and how they mesh together as a whole.

WHAT IS A NARRATIVE?

A narrative is a story that shares a sequence of events , characters, and themes. It expresses experiences, ideas, and perspectives that should aspire to engage and inspire an audience.

A narrative can spark emotion, encourage reflection, and convey meaning when done well.

Narratives are a popular genre for students and teachers as they allow the writer to share their imagination, creativity, skill, and understanding of nearly all elements of writing. We occasionally refer to a narrative as ‘creative writing’ or story writing.

The purpose of a narrative is simple, to tell the audience a story. It can be written to motivate, educate, or entertain and can be fact or fiction.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING NARRATIVE WRITING

Teach your students to become skilled story writers with this HUGE NARRATIVE & CREATIVE STORY WRITING UNIT . Offering a COMPLETE SOLUTION to teaching students how to craft CREATIVE CHARACTERS, SUPERB SETTINGS, and PERFECT PLOTS .

Over 192 PAGES of materials, including:

TYPES OF NARRATIVE WRITING

There are many narrative writing genres and sub-genres such as these.

We have a complete guide to writing a personal narrative that differs from the traditional story-based narrative covered in this guide. It includes personal narrative writing prompts, resources, and examples and can be found here.

As we can see, narratives are an open-ended form of writing that allows you to showcase creativity in many directions. However, all narratives share a common set of features and structure known as “Story Elements”, which are briefly covered in this guide.

Don’t overlook the importance of understanding story elements and the value this adds to you as a writer who can dissect and create grand narratives. We also have an in-depth guide to understanding story elements here .

CHARACTERISTICS OF NARRATIVE WRITING

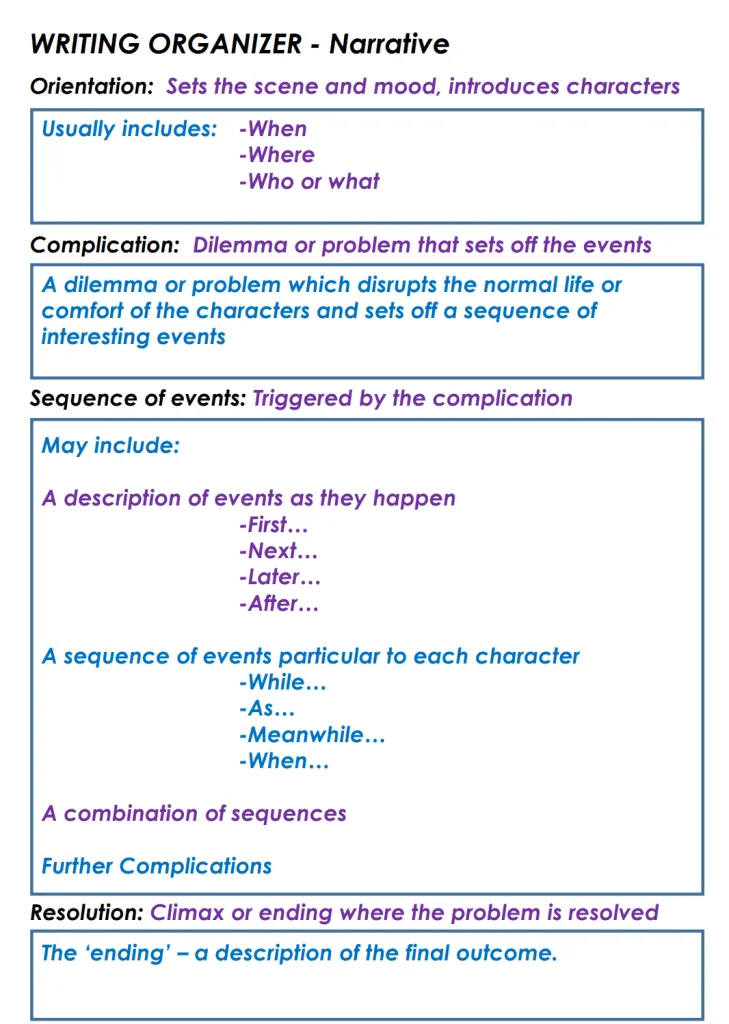

Narrative structure.

ORIENTATION (BEGINNING) Set the scene by introducing your characters, setting and time of the story. Establish your who, when and where in this part of your narrative

COMPLICATION AND EVENTS (MIDDLE) In this section activities and events involving your main characters are expanded upon. These events are written in a cohesive and fluent sequence.

RESOLUTION (ENDING) Your complication is resolved in this section. It does not have to be a happy outcome, however.

EXTRAS: Whilst orientation, complication and resolution are the agreed norms for a narrative, there are numerous examples of popular texts that did not explicitly follow this path exactly.

NARRATIVE FEATURES

LANGUAGE: Use descriptive and figurative language to paint images inside your audience’s minds as they read.

PERSPECTIVE Narratives can be written from any perspective but are most commonly written in first or third person.

DIALOGUE Narratives frequently switch from narrator to first-person dialogue. Always use speech marks when writing dialogue.

TENSE If you change tense, make it perfectly clear to your audience what is happening. Flashbacks might work well in your mind but make sure they translate to your audience.

THE PLOT MAP

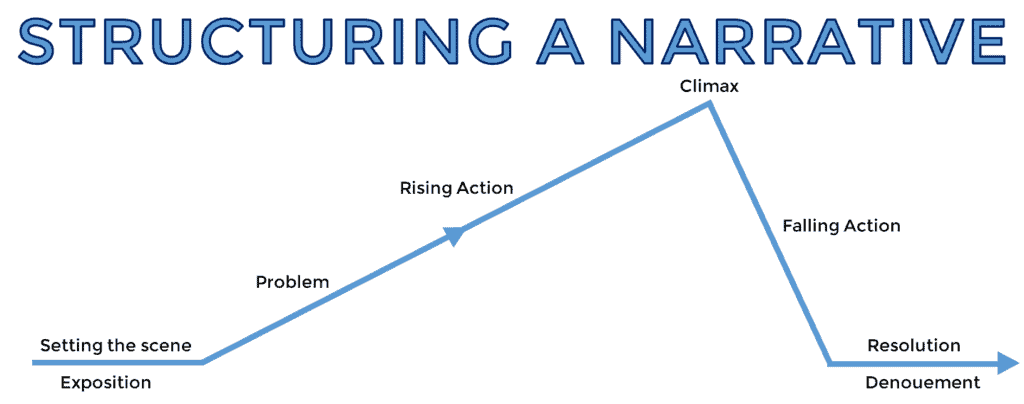

This graphic is known as a plot map, and nearly all narratives fit this structure in one way or another, whether romance novels, science fiction or otherwise.

It is a simple tool that helps you understand and organise a story’s events. Think of it as a roadmap that outlines the journey of your characters and the events that unfold. It outlines the different stops along the way, such as the introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, that help you to see how the story builds and develops.

Using a plot map, you can see how each event fits into the larger picture and how the different parts of the story work together to create meaning. It’s a great way to visualize and analyze a story.

Be sure to refer to a plot map when planning a story, as it has all the essential elements of a great story.

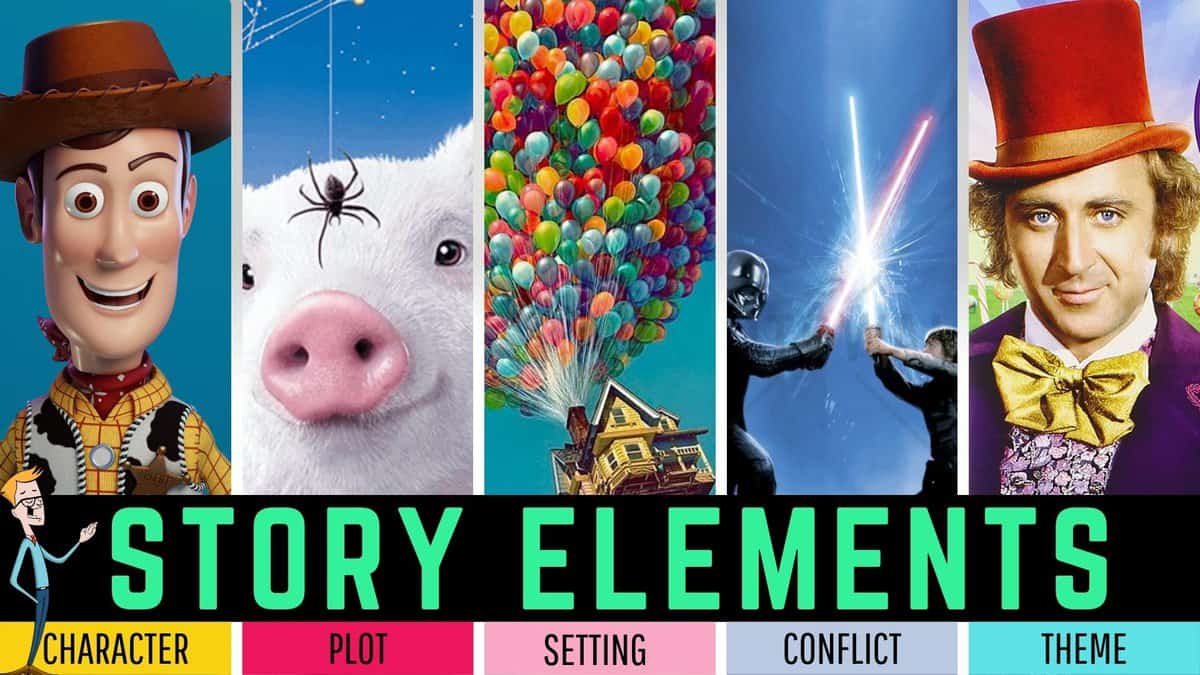

THE 5 KEY STORY ELEMENTS OF A GREAT NARRATIVE (6-MINUTE TUTORIAL VIDEO)

This video we created provides an excellent overview of these elements and demonstrates them in action in stories we all know and love.

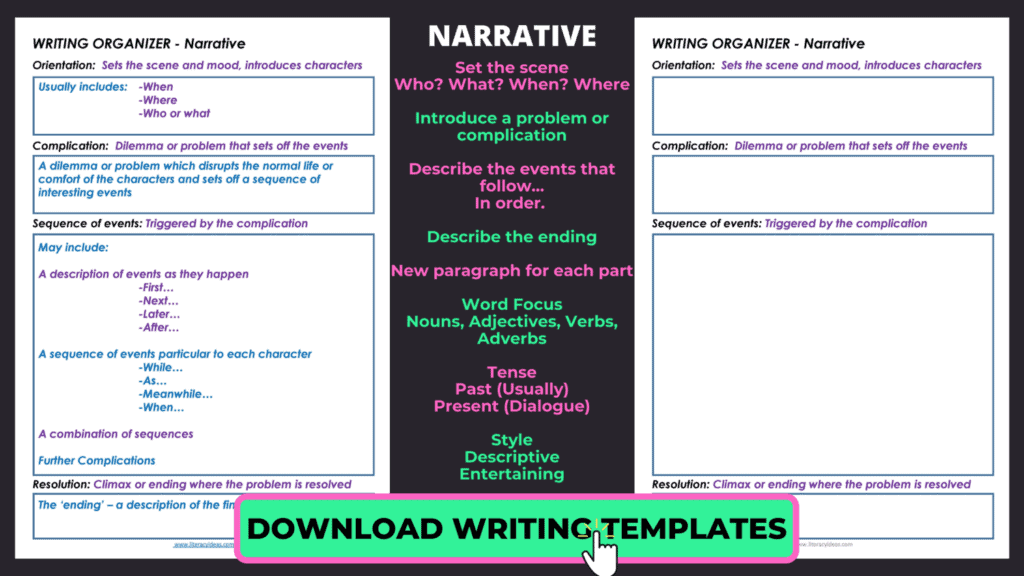

HOW TO WRITE A NARRATIVE

Now that we understand the story elements and how they come together to form stories, it’s time to start planning and writing your narrative.

In many cases, the template and guide below will provide enough details on how to craft a great story. However, if you still need assistance with the fundamentals of writing, such as sentence structure, paragraphs and using correct grammar, we have some excellent guides on those here.

USE YOUR WRITING TIME EFFECTIVELY: Maximize your narrative writing sessions by spending approximately 20 per cent of your time planning and preparing. This ensures greater productivity during your writing time and keeps you focused and on task.

Use tools such as graphic organizers to logically sequence your narrative if you are not a confident story writer. If you are working with reluctant writers, try using narrative writing prompts to get their creative juices flowing.

Spend most of your writing hour on the task at hand, don’t get too side-tracked editing during this time and leave some time for editing. When editing a narrative, examine it for these three elements.

- Spelling and grammar ( Is it readable?)

- Story structure and continuity ( Does it make sense, and does it flow? )

- Character and plot analysis. (Are your characters engaging? Does your problem/resolution work? )

1. SETTING THE SCENE: THE WHERE AND THE WHEN

The story’s setting often answers two of the central questions in the story, namely, the where and the when. The answers to these two crucial questions will often be informed by the type of story the student is writing.

The story’s setting can be chosen to quickly orient the reader to the type of story they are reading. For example, a fictional narrative writing piece such as a horror story will often begin with a description of a haunted house on a hill or an abandoned asylum in the middle of the woods. If we start our story on a rocket ship hurtling through the cosmos on its space voyage to the Alpha Centauri star system, we can be reasonably sure that the story we are embarking on is a work of science fiction.

Such conventions are well-worn clichés true, but they can be helpful starting points for our novice novelists to make a start.

Having students choose an appropriate setting for the type of story they wish to write is an excellent exercise for our younger students. It leads naturally onto the next stage of story writing, which is creating suitable characters to populate this fictional world they have created. However, older or more advanced students may wish to play with the expectations of appropriate settings for their story. They may wish to do this for comic effect or in the interest of creating a more original story. For example, opening a story with a children’s birthday party does not usually set up the expectation of a horror story. Indeed, it may even lure the reader into a happy reverie as they remember their own happy birthday parties. This leaves them more vulnerable to the surprise element of the shocking action that lies ahead.

Once the students have chosen a setting for their story, they need to start writing. Little can be more terrifying to English students than the blank page and its bare whiteness stretching before them on the table like a merciless desert they must cross. Give them the kick-start they need by offering support through word banks or writing prompts. If the class is all writing a story based on the same theme, you may wish to compile a common word bank on the whiteboard as a prewriting activity. Write the central theme or genre in the middle of the board. Have students suggest words or phrases related to the theme and list them on the board.

You may wish to provide students with a copy of various writing prompts to get them started. While this may mean that many students’ stories will have the same beginning, they will most likely arrive at dramatically different endings via dramatically different routes.

A bargain is at the centre of the relationship between the writer and the reader. That bargain is that the reader promises to suspend their disbelief as long as the writer creates a consistent and convincing fictional reality. Creating a believable world for the fictional characters to inhabit requires the student to draw on convincing details. The best way of doing this is through writing that appeals to the senses. Have your student reflect deeply on the world that they are creating. What does it look like? Sound like? What does the food taste like there? How does it feel like to walk those imaginary streets, and what aromas beguile the nose as the main character winds their way through that conjured market?

Also, Consider the when; or the time period. Is it a future world where things are cleaner and more antiseptic? Or is it an overcrowded 16th-century London with human waste stinking up the streets? If students can create a multi-sensory installation in the reader’s mind, then they have done this part of their job well.

Popular Settings from Children’s Literature and Storytelling

- Fairytale Kingdom

- Magical Forest

- Village/town

- Underwater world

- Space/Alien planet

2. CASTING THE CHARACTERS: THE WHO

Now that your student has created a believable world, it is time to populate it with believable characters.

In short stories, these worlds mustn’t be overpopulated beyond what the student’s skill level can manage. Short stories usually only require one main character and a few secondary ones. Think of the short story more as a small-scale dramatic production in an intimate local theater than a Hollywood blockbuster on a grand scale. Too many characters will only confuse and become unwieldy with a canvas this size. Keep it simple!

Creating believable characters is often one of the most challenging aspects of narrative writing for students. Fortunately, we can do a few things to help students here. Sometimes it is helpful for students to model their characters on actual people they know. This can make things a little less daunting and taxing on the imagination. However, whether or not this is the case, writing brief background bios or descriptions of characters’ physical personality characteristics can be a beneficial prewriting activity. Students should give some in-depth consideration to the details of who their character is: How do they walk? What do they look like? Do they have any distinguishing features? A crooked nose? A limp? Bad breath? Small details such as these bring life and, therefore, believability to characters. Students can even cut pictures from magazines to put a face to their character and allow their imaginations to fill in the rest of the details.

Younger students will often dictate to the reader the nature of their characters. To improve their writing craft, students must know when to switch from story-telling mode to story-showing mode. This is particularly true when it comes to character. Encourage students to reveal their character’s personality through what they do rather than merely by lecturing the reader on the faults and virtues of the character’s personality. It might be a small relayed detail in the way they walk that reveals a core characteristic. For example, a character who walks with their head hanging low and shoulders hunched while avoiding eye contact has been revealed to be timid without the word once being mentioned. This is a much more artistic and well-crafted way of doing things and is less irritating for the reader. A character who sits down at the family dinner table immediately snatches up his fork and starts stuffing roast potatoes into his mouth before anyone else has even managed to sit down has revealed a tendency towards greed or gluttony.

Understanding Character Traits

Again, there is room here for some fun and profitable prewriting activities. Give students a list of character traits and have them describe a character doing something that reveals that trait without ever employing the word itself.

It is also essential to avoid adjective stuffing here. When looking at students’ early drafts, adjective stuffing is often apparent. To train the student out of this habit, choose an adjective and have the student rewrite the sentence to express this adjective through action rather than telling.

When writing a story, it is vital to consider the character’s traits and how they will impact the story’s events. For example, a character with a strong trait of determination may be more likely to overcome obstacles and persevere. In contrast, a character with a tendency towards laziness may struggle to achieve their goals. In short, character traits add realism, depth, and meaning to a story, making it more engaging and memorable for the reader.

Popular Character Traits in Children’s Stories

- Determination

- Imagination

- Perseverance

- Responsibility

We have an in-depth guide to creating great characters here , but most students should be fine to move on to planning their conflict and resolution.

3. NO PROBLEM? NO STORY! HOW CONFLICT DRIVES A NARRATIVE

This is often the area apprentice writers have the most difficulty with. Students must understand that without a problem or conflict, there is no story. The problem is the driving force of the action. Usually, in a short story, the problem will center around what the primary character wants to happen or, indeed, wants not to happen. It is the hurdle that must be overcome. It is in the struggle to overcome this hurdle that events happen.

Often when a student understands the need for a problem in a story, their completed work will still not be successful. This is because, often in life, problems remain unsolved. Hurdles are not always successfully overcome. Students pick up on this.

We often discuss problems with friends that will never be satisfactorily resolved one way or the other, and we accept this as a part of life. This is not usually the case with writing a story. Whether a character successfully overcomes his or her problem or is decidedly crushed in the process of trying is not as important as the fact that it will finally be resolved one way or the other.

A good practical exercise for students to get to grips with this is to provide copies of stories and have them identify the central problem or conflict in each through discussion. Familiar fables or fairy tales such as Three Little Pigs, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, Cinderella, etc., are great for this.

While it is true that stories often have more than one problem or that the hero or heroine is unsuccessful in their first attempt to solve a central problem, for beginning students and intermediate students, it is best to focus on a single problem, especially given the scope of story writing at this level. Over time students will develop their abilities to handle more complex plots and write accordingly.

Popular Conflicts found in Children’s Storytelling.

- Good vs evil

- Individual vs society

- Nature vs nurture

- Self vs others

- Man vs self

- Man vs nature

- Man vs technology

- Individual vs fate

- Self vs destiny

Conflict is the heart and soul of any good story. It’s what makes a story compelling and drives the plot forward. Without conflict, there is no story. Every great story has a struggle or a problem that needs to be solved, and that’s where conflict comes in. Conflict is what makes a story exciting and keeps the reader engaged. It creates tension and suspense and makes the reader care about the outcome.

Like in real life, conflict in a story is an opportunity for a character’s growth and transformation. It’s a chance for them to learn and evolve, making a story great. So next time stories are written in the classroom, remember that conflict is an essential ingredient, and without it, your story will lack the energy, excitement, and meaning that makes it truly memorable.

4. THE NARRATIVE CLIMAX: HOW THINGS COME TO A HEAD!

The climax of the story is the dramatic high point of the action. It is also when the struggles kicked off by the problem come to a head. The climax will ultimately decide whether the story will have a happy or tragic ending. In the climax, two opposing forces duke things out until the bitter (or sweet!) end. One force ultimately emerges triumphant. As the action builds throughout the story, suspense increases as the reader wonders which of these forces will win out. The climax is the release of this suspense.

Much of the success of the climax depends on how well the other elements of the story have been achieved. If the student has created a well-drawn and believable character that the reader can identify with and feel for, then the climax will be more powerful.

The nature of the problem is also essential as it determines what’s at stake in the climax. The problem must matter dearly to the main character if it matters at all to the reader.

Have students engage in discussions about their favorite movies and books. Have them think about the storyline and decide the most exciting parts. What was at stake at these moments? What happened in your body as you read or watched? Did you breathe faster? Or grip the cushion hard? Did your heart rate increase, or did you start to sweat? This is what a good climax does and what our students should strive to do in their stories.

The climax puts it all on the line and rolls the dice. Let the chips fall where the writer may…

Popular Climax themes in Children’s Stories

- A battle between good and evil

- The character’s bravery saves the day

- Character faces their fears and overcomes them

- The character solves a mystery or puzzle.

- The character stands up for what is right.

- Character reaches their goal or dream.

- The character learns a valuable lesson.

- The character makes a selfless sacrifice.

- The character makes a difficult decision.

- The character reunites with loved ones or finds true friendship.

5. RESOLUTION: TYING UP LOOSE ENDS

After the climactic action, a few questions will often remain unresolved for the reader, even if all the conflict has been resolved. The resolution is where those lingering questions will be answered. The resolution in a short story may only be a brief paragraph or two. But, in most cases, it will still be necessary to include an ending immediately after the climax can feel too abrupt and leave the reader feeling unfulfilled.

An easy way to explain resolution to students struggling to grasp the concept is to point to the traditional resolution of fairy tales, the “And they all lived happily ever after” ending. This weather forecast for the future allows the reader to take their leave. Have the student consider the emotions they want to leave the reader with when crafting their resolution.

While the action is usually complete by the end of the climax, it is in the resolution that if there is a twist to be found, it will appear – think of movies such as The Usual Suspects. Pulling this off convincingly usually requires considerable skill from a student writer. Still, it may well form a challenging extension exercise for those more gifted storytellers among your students.

Popular Resolutions in Children’s Stories

- Our hero achieves their goal

- The character learns a valuable lesson

- A character finds happiness or inner peace.

- The character reunites with loved ones.

- Character restores balance to the world.

- The character discovers their true identity.

- Character changes for the better.

- The character gains wisdom or understanding.

- Character makes amends with others.

- The character learns to appreciate what they have.

Once students have completed their story, they can edit for grammar, vocabulary choice, spelling, etc., but not before!

As mentioned, there is a craft to storytelling, as well as an art. When accurate grammar, perfect spelling, and immaculate sentence structures are pushed at the outset, they can cause storytelling paralysis. For this reason, it is essential that when we encourage the students to write a story, we give them license to make mechanical mistakes in their use of language that they can work on and fix later.

Good narrative writing is a very complex skill to develop and will take the student years to become competent. It challenges not only the student’s technical abilities with language but also her creative faculties. Writing frames, word banks, mind maps, and visual prompts can all give valuable support as students develop the wide-ranging and challenging skills required to produce a successful narrative writing piece. But, at the end of it all, as with any craft, practice and more practice is at the heart of the matter.

TIPS FOR WRITING A GREAT NARRATIVE

- Start your story with a clear purpose: If you can determine the theme or message you want to convey in your narrative before starting it will make the writing process so much simpler.

- Choose a compelling storyline and sell it through great characters, setting and plot: Consider a unique or interesting story that captures the reader’s attention, then build the world and characters around it.

- Develop vivid characters that are not all the same: Make your characters relatable and memorable by giving them distinct personalities and traits you can draw upon in the plot.

- Use descriptive language to hook your audience into your story: Use sensory language to paint vivid images and sequences in the reader’s mind.

- Show, don’t tell your audience: Use actions, thoughts, and dialogue to reveal character motivations and emotions through storytelling.

- Create a vivid setting that is clear to your audience before getting too far into the plot: Describe the time and place of your story to immerse the reader fully.

- Build tension: Refer to the story map earlier in this article and use conflict, obstacles, and suspense to keep the audience engaged and invested in your narrative.

- Use figurative language such as metaphors, similes, and other literary devices to add depth and meaning to your narrative.

- Edit, revise, and refine: Take the time to refine and polish your writing for clarity and impact.

- Stay true to your voice: Maintain your unique perspective and style in your writing to make it your own.

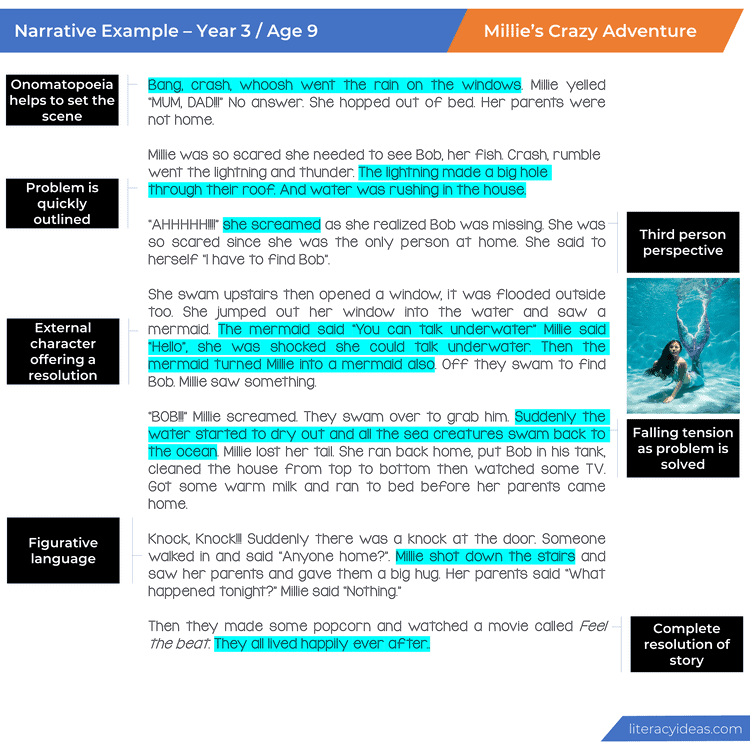

NARRATIVE WRITING EXAMPLES (Student Writing Samples)

Below are a collection of student writing samples of narratives. Click on the image to enlarge and explore them in greater detail. Please take a moment to read these creative stories in detail and the teacher and student guides which highlight some of the critical elements of narratives to consider before writing.

Please understand these student writing samples are not intended to be perfect examples for each age or grade level but a piece of writing for students and teachers to explore together to critically analyze to improve student writing skills and deepen their understanding of story writing.

We recommend reading the example either a year above or below, as well as the grade you are currently working with, to gain a broader appreciation of this text type.

NARRATIVE WRITING PROMPTS (Journal Prompts)

When students have a great journal prompt, it can help them focus on the task at hand, so be sure to view our vast collection of visual writing prompts for various text types here or use some of these.

- On a recent European trip, you find your travel group booked into the stunning and mysterious Castle Frankenfurter for a single night… As night falls, the massive castle of over one hundred rooms seems to creak and groan as a series of unexplained events begin to make you wonder who or what else is spending the evening with you. Write a narrative that tells the story of your evening.

- You are a famous adventurer who has discovered new lands; keep a travel log over a period of time in which you encounter new and exciting adventures and challenges to overcome. Ensure your travel journal tells a story and has a definite introduction, conflict and resolution.

- You create an incredible piece of technology that has the capacity to change the world. As you sit back and marvel at your innovation and the endless possibilities ahead of you, it becomes apparent there are a few problems you didn’t really consider. You might not even be able to control them. Write a narrative in which you ride the highs and lows of your world-changing creation with a clear introduction, conflict and resolution.

- As the final door shuts on the Megamall, you realise you have done it… You and your best friend have managed to sneak into the largest shopping centre in town and have the entire place to yourselves until 7 am tomorrow. There is literally everything and anything a child would dream of entertaining themselves for the next 12 hours. What amazing adventures await you? What might go wrong? And how will you get out of there scot-free?

- A stranger walks into town… Whilst appearing similar to almost all those around you, you get a sense that this person is from another time, space or dimension… Are they friends or foes? What makes you sense something very strange is going on? Suddenly they stand up and walk toward you with purpose extending their hand… It’s almost as if they were reading your mind.

NARRATIVE WRITING VIDEO TUTORIAL

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your student’s writing skills through proven teaching strategies.

When teaching narrative writing, it is essential that you have a range of tools, strategies and resources at your disposal to ensure you get the most out of your writing time. You can find some examples below, which are free and paid premium resources you can use instantly without any preparation.

FREE Narrative Graphic Organizer

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

NARRATIVE WRITING CHECKLIST BUNDLE

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES ABOUT NARRATIVE WRITING

Narrative Writing for Kids: Essential Skills and Strategies

7 Great Narrative Lesson Plans Students and Teachers Love

Top 7 Narrative Writing Exercises for Students

How to Write a Scary Story

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 20, 2023

Creative Nonfiction: How to Spin Facts into Narrative Gold

Creative nonfiction is a genre of creative writing that approaches factual information in a literary way. This type of writing applies techniques drawn from literary fiction and poetry to material that might be at home in a magazine or textbook, combining the craftsmanship of a novel with the rigor of journalism.

Here are some popular examples of creative nonfiction:

- The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Weijun Wang

- Intimations by Zadie Smith

- Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

- Translating Myself and Others by Jhumpa Lahiri

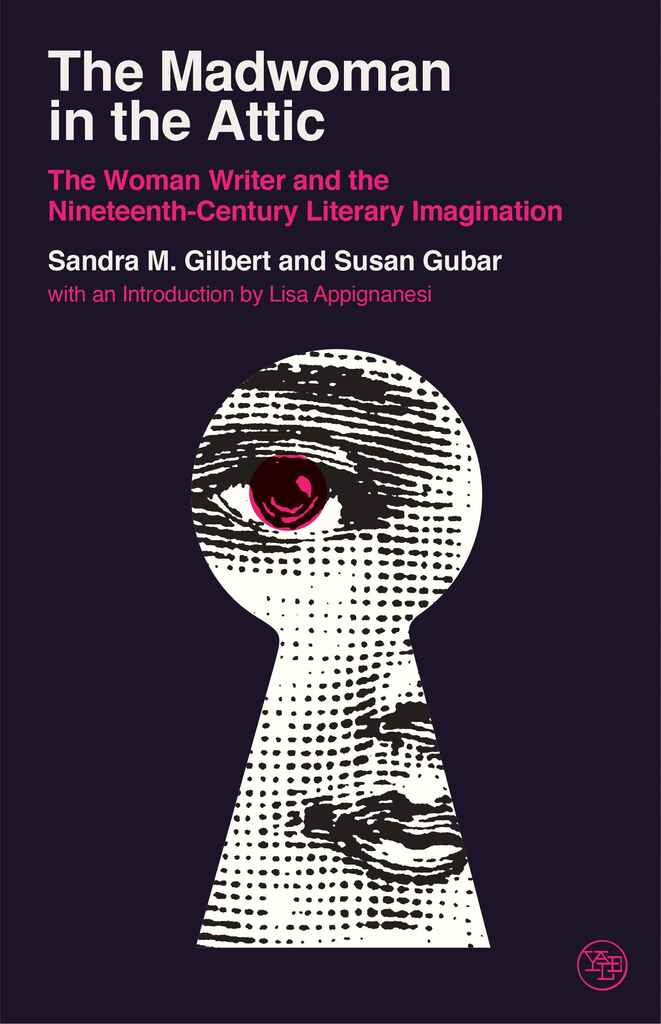

- The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

- I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

- Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino

Creative nonfiction is not limited to novel-length writing, of course. Popular radio shows and podcasts like WBEZ’s This American Life or Sarah Koenig’s Serial also explore audio essays and documentary with a narrative approach, while personal essays like Nora Ephron’s A Few Words About Breasts and Mariama Lockington’s What A Black Woman Wishes Her Adoptive White Parents Knew also present fact with fiction-esque flair.

Writing short personal essays can be a great entry point to writing creative nonfiction. Think about a topic you would like to explore, perhaps borrowing from your own life, or a universal experience. Journal freely for five to ten minutes about the subject, and see what direction your creativity takes you in. These kinds of exercises will help you begin to approach reality in a more free flowing, literary way — a muscle you can use to build up to longer pieces of creative nonfiction.

If you think you’d like to bring your writerly prowess to nonfiction, here are our top tips for creating compelling creative nonfiction that’s as readable as a novel, but as illuminating as a scholarly article.

Write a memoir focused on a singular experience

Humans love reading about other people’s lives — like first-person memoirs, which allow you to get inside another person’s mind and learn from their wisdom. Unlike autobiographies, memoirs can focus on a single experience or theme instead of chronicling the writers’ life from birth onward.

For that reason, memoirs tend to focus on one core theme and—at least the best ones—present a clear narrative arc, like you would expect from a novel. This can be achieved by selecting a singular story from your life; a formative experience, or period of time, which is self-contained and can be marked by a beginning, a middle, and an end.

When writing a memoir, you may also choose to share your experience in parallel with further research on this theme. By performing secondary research, you’re able to bring added weight to your anecdotal evidence, and demonstrate the ways your own experience is reflective (or perhaps unique from) the wider whole.

Example: The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking , for example, interweaves the author’s experience of widowhood with sociological research on grief. Chronicling the year after her husband’s unexpected death, and the simultaneous health struggles of their daughter, The Year of Magical Thinking is a poignant personal story, layered with universal insight into what it means to lose someone you love. The result is the definitive exploration of bereavement — and a stellar example of creative nonfiction done well.

📚 Looking for more reading recommendations? Check out our list of the best memoirs of the last century .

Tip: What you cut out is just as important as what you keep

When writing a memoir that is focused around a singular theme, it’s important to be selective in what to include, and what to leave out. While broader details of your life may be helpful to provide context, remember to resist the impulse to include too much non-pertinent backstory. By only including what is most relevant, you are able to provide a more focused reader experience, and won’t leave readers guessing what the significance of certain non-essential anecdotes will be.

💡 For more memoir-planning tips, head over to our post on outlining memoirs .

Of course, writing a memoir isn’t the only form of creative nonfiction that lets you tap into your personal life — especially if there’s something more explicit you want to say about the world at large… which brings us onto our next section.

Pen a personal essay that has something bigger to say

Personal essays condense the first-person focus and intimacy of a memoir into a tighter package — tunneling down into a specific aspect of a theme or narrative strand within the author’s personal experience.

Often involving some element of journalistic research, personal essays can provide examples or relevant information that comes from outside the writer’s own experience. This can take the form of other people’s voices quoted in the essay, or facts and stats. By combining lived experiences with external material, personal essay writers can reach toward a bigger message, telling readers something about human behavior or society instead of just letting them know the writer better.

Example: The Empathy Exams by Leslie Jamison

Leslie Jamison's widely acclaimed collection The Empathy Exams tackles big questions (Why is pain so often performed? Can empathy be “bad”?) by grounding them in the personal. While Jamison draws from her own experiences, both as a medical actor who was paid to imitate pain, and as a sufferer of her own ailments, she also reaches broader points about the world we live in within each of her essays.

Whether she’s talking about the justice system or reality TV, Jamison writes with both vulnerability and poise, using her lived experience as a jumping-off point for exploring the nature of empathy itself.

Tip: Try to show change in how you feel about something

Including external perspectives, as we’ve just discussed above, will help shape your essay, making it meaningful to other people and giving your narrative an arc.

Ultimately, you may be writing about yourself, but readers can read what they want into it. In a personal narrative, they’re looking for interesting insights or realizations they can apply to their own understanding of their lives or the world — so don’t lose sight of that. As the subject of the essay, you are not so much the topic as the vehicle for furthering a conversation.

Often, there are three clear stages in an essay:

- Initial state

- Encounter with something external

- New, changed state, and conclusions

By bringing readers through this journey with you, you can guide them to new outlooks and demonstrate how your story is still relevant to them.

Had enough of writing about your own life? Let’s look at a form of creative nonfiction that allows you to get outside of yourself.

Tell a factual story as though it were a novel

The form of creative nonfiction that is perhaps closest to conventional nonfiction is literary journalism. Here, the stories are all fact, but they are presented with a creative flourish. While the stories being told might comfortably inhabit a newspaper or history book, they are presented with a sense of literary significance, and writers can make use of literary techniques and character-driven storytelling.

Unlike news reporters, literary journalists can make room for their own perspectives: immersing themselves in the very action they recount. Think of them as both characters and narrators — but every word they write is true.

If you think literary journalism is up your street, think about the kinds of stories that capture your imagination the most, and what those stories have in common. Are they, at their core, character studies? Parables? An invitation to a new subculture you have never before experienced? Whatever piques your interest, immerse yourself.

Example: The Botany of Desire by Michael Pollan

If you’re looking for an example of literary journalism that tells a great story, look no further than Michael Pollan’s The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s-Eye View of the World , which sits at the intersection of food writing and popular science. Though it purports to offer a “plant’s-eye view of the world,” it’s as much about human desires as it is about the natural world.

Through the history of four different plants and human’s efforts to cultivate them, Pollan uses first-hand research as well as archival facts to explore how we attempt to domesticate nature for our own pleasure, and how these efforts can even have devastating consequences. Pollan is himself a character in the story, and makes what could be a remarkably dry topic accessible and engaging in the process.

Tip: Don’t pretend that you’re perfectly objective

You may have more room for your own perspective within literary journalism, but with this power comes great responsibility. Your responsibilities toward the reader remain the same as that of a journalist: you must, whenever possible, acknowledge your own biases or conflicts of interest, as well as any limitations on your research.

Thankfully, the fact that literary journalism often involves a certain amount of immersion in the narrative — that is, the writer acknowledges their involvement in the process — you can touch on any potential biases explicitly, and make it clear that the story you’re telling, while true to what you experienced, is grounded in your own personal perspective.

Approach a famous name with a unique approach

Biographies are the chronicle of a human life, from birth to the present or, sometimes, their demise. Often, fact is stranger than fiction, and there is no shortage of fascinating figures from history to discover. As such, a biographical approach to creative nonfiction will leave you spoilt for choice in terms of subject matter.

Because they’re not written by the subjects themselves (as memoirs are), biographical nonfiction requires careful research. If you plan to write one, do everything in your power to verify historical facts, and interview the subject’s family, friends, and acquaintances when possible. Despite the necessity for candor, you’re still welcome to approach biography in a literary way — a great creative biography is both truthful and beautifully written.

Example: American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

Alongside the need for you to present the truth is a duty to interpret that evidence with imagination, and present it in the form of a story. Demonstrating a novelist’s skill for plot and characterization, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s American Prometheus is a great example of creative nonfiction that develops a character right in front of the readers’ eyes.

American Prometheus follows J. Robert Oppenheimer from his bashful childhood to his role as the father of the atomic bomb, all the way to his later attempts to reckon with his violent legacy.

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

The biography tells a story that would fit comfortably in the pages of a tragic novel, but is grounded in historical research. Clocking in at a hefty 721 pages, American Prometheus distills an enormous volume of archival material, including letters, FBI files, and interviews into a remarkably readable volume.

📚 For more examples of world-widening, eye-opening biographies, check out our list of the 30 best biographies of all time .

Tip: The good stuff lies in the mundane details

Biographers are expected to undertake academic-grade research before they put pen to paper. You will, of course, read any existing biographies on the person you’re writing about, and visit any archives containing relevant material. If you’re lucky, there’ll be people you can interview who knew your subject personally — but even if there aren’t, what’s going to make your biography stand out is paying attention to details, even if they seem mundane at first.

Of course, no one cares which brand of slippers a former US President wore — gossip is not what we’re talking about. But if you discover that they took a long, silent walk every single morning, that’s a granular detail you could include to give your readers a sense of the weight they carried every day. These smaller details add up to a realistic portrait of a living, breathing human being.

But creative nonfiction isn’t just writing about yourself or other people. Writing about art is also an art, as we’ll see below.

Put your favorite writers through the wringer with literary criticism

Literary criticism is often associated with dull, jargon-laden college dissertations — but it can be a wonderfully rewarding form that blurs the lines between academia and literature itself. When tackled by a deft writer, a literary critique can be just as engrossing as the books it analyzes.

Many of the sharpest literary critics are also poets, poetry editors , novelists, or short story writers, with first-hand awareness of literary techniques and the ability to express their insights with elegance and flair. Though literary criticism sounds highly theoretical, it can be profoundly intimate: you’re invited to share in someone’s experience as a reader or writer — just about the most private experience there is.

Example: The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

Take The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, a seminal work approaching Victorian literature from a feminist perspective. Written as a conversation between two friends and academics, this brilliant book reads like an intellectual brainstorming session in a casual dining venue. Highly original, accessible, and not suffering from the morose gravitas academia is often associated with, this text is a fantastic example of creative nonfiction.

Tip: Remember to make your critiques creative

Literary criticism may be a serious undertaking, but unless you’re trying to pitch an academic journal, you’ll need to be mindful of academic jargon and convoluted sentence structure. Don’t forget that the point of popular literary criticism is to make ideas accessible to readers who aren’t necessarily academics, introducing them to new ways of looking at anything they read.

If you’re not feeling confident, a professional nonfiction editor could help you confirm you’ve hit the right stylistic balance.

Give your book the help it deserves

The best editors, designers, and book marketers are on Reedsy. Sign up for free and meet them.

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

Is creative nonfiction looking a little bit clearer now? You can try your hand at the genre , or head to the next post in this guide and discover online classes where you can hone your skills at creative writing.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your publishing dreams to life

The world's best editors, designers, and marketers are on Reedsy. Come meet them.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest Content

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 4, Issue 1

- Combining creative writing and narrative analysis to deliver new insights into the impact of pulmonary hypertension

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Julia C Goddard 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Iain J Armstrong 2 ,

- David G Kiely 2 ,

- Charlie A Elliot 2 ,

- Athanasios Charalampopoulos 2 ,

- Robin Condliffe 2 ,

- Brendan J Stone 4 and

- Ian Sabroe 1 , 2 , 3

- 1 Department of Infection, Immunity and Cardiovascular Science, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health , University of Sheffield , Sheffield , UK

- 2 Sheffield Pulmonary Vascular Disease Unit , Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust , Sheffield , UK

- 3 Medical Humanities Sheffield , University of Sheffield , Sheffield , UK

- 4 School of English, Faculty of Arts and Humanities , University of Sheffield , Sheffield , UK

- Correspondence to Prof Ian Sabroe; i.sabroe{at}sheffield.ac.uk

Introduction Pulmonary hypertension is life limiting. Delays in diagnosis are common, and even after treatment has been initiated, pulmonary hypertension has marked effects on many aspects of social and physical function. We believed that a new approach to examining disease impact could be achieved through a combination of narrative research and creative writing.

Methods Detailed unstructured narrative interviews with people with pulmonary hypertension were analysed thematically. Individual moments were also summarised and studied using creative writing, in which the interviewer created microstories from narrative and interview data. Stories were shared with their subjects, and with other patients, clinicians, researchers and the wider public. The study was carried out in hospital and in patients’ homes.

Results Narrative analysis generated a rich data set which highlighted profound effects of pulmonary hypertension on identity, and demonstrated how the disease results in very marked personal change with ongoing and unpredictable requirement for adaptation. The novel methodology of microstory development proved to be an effective tool to summarise, communicate and explore the consequences of pulmonary hypertension and the clinical challenges of caring for patients with this illness.

Conclusions A holistic approach to treatment of chronic respiratory diseases such as pulmonary hypertension requires and benefits from explicit exploration of the full impacts of the illness. Narrative analysis and the novel approach of targeted microstory development can form a valuable component of the repertoire of approaches to effectively comprehend chronic disease and can also facilitate patient-focused discussion and interventions.

- Primary Pulmonary Hypertension

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2017-000184

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare condition in which increased pulmonary arterial resistance results in progressive right ventricular failure. Median survival in untreated idiopathic disease is <3 years and, although specific therapies are now available, it is still associated with reduced life expectancy. Sufferers may appear well at rest, even when cardiac output is critically limited, leading to diagnostic delay and a substantial associated medical and psychological morbidity. 1

High-impact medical research has become dominated by fundamental science or the development of new interventions. However, the delivery of good clinical care is often centred in profoundly personal interactions that change outcomes for individuals very powerfully. 2 Quality of life can be assessed by clinically relevant and applicable scoring systems 3–5 and correlates with outcomes. 6 Study of these qualitative aspects of healthcare, though central to clinical practice, is rarely accorded high impact, perhaps both because of its perceived immediate failure to generate a new therapeutic target, and also in the difficulty there is in precisely quantifying the impact that it has. Qualitative studies in pulmonary hypertension have nonetheless highlighted the challenges for patients of developing an understanding of their illness and of coping with its progression, 7 and holistic care includes close attention to qualitative factors. 8

Narrative analysis is a qualitative research discipline developing deeper understanding of (in the medical case) illness from unstructured subject-derived data. Narrative approaches have roles in developing key clinical skills in clinical practitioners, 9 and narrative research and practice have an important place in clinical medicine. 10–12 Clinical practice operates in a narrative environment in which evidence-based medicine is applied within the context of individual patient stories. However, applying results of narrative studies to clinical practice is more challenging; the impact can be felt by highlighting paradigms or assumptions that are made, often without conscious thought. The length of narratives and their examination by techniques such as thematic analysis do not lend themselves to linking of narratives to changes in management within an individual, and communicating key findings in a concise form is challenging.

We believed that a narrative approach would yield specific and valuable insights into the challenges and management of PAH. We took a new approach using interpretative observer-dependent creative writing to summarise narratives and present them as microstories. We believed creating microstories would generate a new way to analyse these narratives, and simultaneously make the narratives more accessible to others. These stories have revealed themselves to be remarkable for their ability to reveal and communicate experiences of illness that are fundamental to a deeper understanding of an individual’s changing circumstances. These stories were received well by the participants who inspired them and have proved to be a powerful initiator of conversation and the reflective sharing of meaningful experience in other patients, family members and clinical care teams.

Unstructured interviews were conducted by one author (JCG) in a variety of locations (hospital ward, hospital canteen/café, patient’s home). Conversations were initiated with open-ended questions but with an aim to initiate discussions about the patient’s illness. Data were recorded and transcribed, and subjected to narrative and thematic analysis using subjective qualitative evaluation to identify key themes arising from the interviews. The study was approved by NRES Yorkshire and The Humber Ref 14/YH/1016.

Microstories were defined arbitrarily as short stories of approximately 200–300 words. Topics were identified by transcript review by JCG as being reflective of important or pivotal moments for the participant at that point in time, and stories were written by JCG. Where names or initials are used in attributed comments or stories, these were randomly selected from a predetermined list and are therefore deidentified. Where random anonymised initials are used to identify speakers of individual comments, the same initials are used for the same individual throughout. Evaluation of microstories was undertaken through (1) by showing them to the participants who inspired them and, if they chose, to their families (2) a focus group made up of patients with pulmonary hypertension and their partners, independent to the narrative collection, recruited through the Pulmonary Hypertension Association UK and under the same ethically approved main study protocol, and (3) a public 1-day exhibition of microstories developed and supported by a local arts charity, Ignite Imaginations.

Interviews were conducted with 12 patients from the Sheffield Pulmonary Vascular Disease Unit. Two patients were in the 20–29 year age group, four in the 30–39 year group, two in the 50–59 year group, three in the 60–69 year group and one in the 70–79 year group. Where possible, multiple interviews were conducted with the same person to allow for new themes to emerge and participants to reflect upon previous conversations. Six male and six female patients were recruited. Three patients were interviewed once, six were interviewed twice, one interviewed three times and one interviewed four times. Twenty-three interviews of average length 70 min were undertaken, transcribed and analysed. Prominent themes were identified, which included the prolonged delays in diagnosis experienced between symptom onset and specialist centre referral, impact of diagnosis, complexity of therapy, frequency of hospital admissions, access to information and the reassurance of care delivered by an expert unit in a supportive ‘family’ environment. Impact of the diagnosis showed up in discussions of life expectancy, holiday planning, effect of illness on children, other family members and friends, and effects on ability to work, undertake exercise and perform routine tasks.

Narratives revealed PAH to have marked effects on individuals that changed sometimes rapidly with time. Many subjects showed evidence of a frequent reappraisal of their illness and its impacts, and the fluctuating priorities and issues displayed in the narratives highlight a need for healthcare workers to be very sensitive to changing patient concerns. Specific themes are discussed here. Narrative analysis seeks to consider the individual as a whole, rather than only one element of their story. Therefore, microstories have been used to illustrate specific themes to present the change within the context of an individual, rather than an abstract concept.

In this manuscript, we explore issues around diagnosis , perceptions of liaison between local and specialist services , symptoms and their impact , impact on family and young children , coping , and how narratives change.

A diagnosis

To finally get a diagnosis! Amanda has been waiting for it for months, for years even. She has been feeling ill, feeling exhausted, feeling unlike herself and not knowing why. The doctors told her there was nothing wrong, that she was fine, that had she thought about visiting a therapist?

But now she has the answer! The answer may bring up more questions than it answers but it explains the fatigue. It explains why she wasn’t able to play with her kids, why she couldn’t take them to school, why she couldn’t help with their homework.

The diagnosis doesn’t provide a cure, it doesn’t mean all her problems are solved. But it helps many of them. They say the medications may just be for the symptoms but this is what she has been looking for. She feels normal again.

She no longer has to go out in a wheelchair, feeling like an old woman. She can walk up and down stairs unaided. She can drive again. She has got her independence back.

The diagnosis is not an easy one and there are still many more challenges to face but at least now she knows what she is facing. At least now she has some help. At least now she has a reason for it.

It takes on average 2½ years from onset of symptoms to diagnosis in PH and consequently many participants spoke of their diagnosis and the process leading up to it. Despite having such a poor prognosis, many found the diagnosis a relief; it bought with it an understanding of why they were experiencing symptoms, and also provided an opportunity for appropriate treatment. The quotes below show participants’ attitudes towards getting a diagnosis, and comments from being misdiagnosed. All quotations are taken as spoken from transcribed audio.

“And I thought, ‘Well, I’m just unfit’.” JB (male)

“And she said, ‘I think you’ve got angina’.” TL (male)

“Got misdiagnosed as asthma for a long time.” BW (male)

“Then when [the doctor] told me that I’d got it. It were like a weight had been lifted. It’s scarier not knowing, than knowing.” EJ (female)

“It’s nice to actually have a diagnosis… the medicine to help you carry on and remain stable.” SW (female)

Perceptions of liaison between local and specialist services

Insider’s knowledge.

Andy smiles to himself as he sees the confused look on the doctor’s face. He knows full well that this doctor, and probably most of the people on the ward, haven’t heard of his disease, most people haven’t. And Andy knows roughly what’s about to happen next as well. There’s a few ways that it can go, but it tends to follow a certain pattern.

The doctor may try and bluff his way through it. Entertaining, but obvious. They may look it up on their phone. Wikipedia has a lot to answer for. The preferred option is, however, that they ask.

After living with the disease for half a decade now Andy has a range of explanations at his fingertips. He has the one for younger children. He has one for when he’s in a rush. He has one for his grandma’s friends who are being polite and enquiring after his health. And, of course, he has one for doctors who admit to knowing little about this rare condition.

It can become a little awkward if they don’t ask. If they demand that he listen to them, that they are the doctor and they know more, that they understand what the ECG means. Andy may not know what each of the little squiggles on the page mean but he knows his ECG isn’t going to look normal, isn’t going to look like everyone else’s. He could have told them this at the beginning as well, if only they had asked.

Symptoms and their impact

Changing plans.

A lot of people make plans leading up to retirement and these can be plans about anything and everything. Harry and his wife, Barbara, looked forward to his retirement because it meant more time spent enjoying each other’s company and enjoying their old age. Harry had always worked a demanding job with long hours and they were looking forward to relaxing and travelling more, taking up new hobbies and spending more time on their old ones. It was a retirement that was well deserved.

But health is difficult to plan for. Harry’s breathing is gradually getting worse and tiredness is starting to creep in. And with great sadness, he has had to give up his motorbike. It was a heavy, ‘long-legged’ bike and the worry was that the weight of it would be too much for Harry. It was a huge wrench for him, and one that isn’t forgotten easily; each time he is sitting in traffic watching the motorcyclists weave their way through cars.

Not all is lost though. He has been a petrol-head for years and still drives the circuits he loves in the newest cars. Only now he adjusts the time he spends driving—a little less is better than nothing.

It might not be the retirement they planned for, but Harry and Barbara will carry on. After all, the road between home and the hospital alone is a delight to drive, especially in the early morning when it is free of traffic. Arriving early, there is time for a coffee and breakfast before facing whatever clinic has in store for them.

Other participants spoke of their physical symptoms. Tiredness and shortness of breath featured heavily, as did sensations of palpitations. Professor Havi Carel, a philosopher who has reported on her own lung disease, observed ‘Our attention is drawn to the malfunctioning body part… it becomes the focus of our attention, rather than the invisible background for our activities.’ 13 So it was for the patients in our study:

“It’s not a tired. It’s like you’ve been hit by a bus three times. And I want to feel what it’s like to just be tired.” EJ (female)

“My heart’s fluttering about so much, I think I’m going to pass out.” BP (female)

“Sometimes I’ll go to bed and I’ll feel that bad, I think I won’t wake up in the morning.” EJ (female)

“What does me head in most is how random it is.” SJ (male)

Patients have commented additionally how the disease is hidden from those around them, since at rest patients are usually not breathless, and do not usually experience overt stigmatising of their illness.

“ Outwardly… I look fine, and I do to everybody else, so loads of people think I’m putting it on or I pick and choose when my illness affects me.” CE (female)

Microstories were produced to reflect on this dominant component to narratives, illustrated in the online supplement story, ‘Well, this don’t seem right!”.

Impact on family and young children

It is natural and normal to worry about your children and it is something that any parent will know well. But as Maggie watches her son her worries run much deeper than the normal concerns of whether they have nice friends, how they’re doing at school, if they’re happy. She is watching him for signs of the same illness she has—the illness that she carries in her genes and that she thinks about every day. It is something she turns over in her mind each time she looks at her son.

She describes the guilt she feels, a powerful emotion. One even more powerful because it is not her fault, there was nothing she did wrong—fate rolled the wrong dice for her and only time will tell if it rolled the wrong dice for her son. Watching and waiting is a difficult prescription to carry out but Maggie hopes to wait for a long time, hopes that she will always be watching and waiting.

Because she will. She will always be watching her son and this is what will protect her children from whatever the future holds. There is nothing more powerful than a parent’s love.

Participants with young children often spoke about how if affected the way they were able to act as parent, and respond to societal and family expectations. This was especially apparent if they viewed themselves as ‘failing’ at something they feel they should be doing. Some patients also made specific comments on their preparedness for death and their own funerals, and expressed concern about the future impact on their partners and children.

“I still wanted to be a mum, I still wanted to be a wife… it’s not fair on my son, it’s not fair on my husband.” CE (female)

“I try not to let it affect them. I mean, it’s going to affect them, I’m in here [hospital] and they’re, they’re out there.” EJ (female)

“I knew I couldn’t go home [from hospital for Christmas]. That would have been very disruptive… I didn’t want to be an imposition on the family.” JB (male)

“You feel a bit lazy if you can’t do what everyone else does; run a house, look after your kids.” SW (female)

“Planned me funeral, I’ve wrote everything down.” EJ (female)

“I’ve made a list of my will or what I want to happen at my funeral and things like that.” CE (female)

Separate elements

Old Sophia. That’s what she wants back, Old Sophia. The person she used to be, before all this. The more relaxed one, the one that had less to worry about, the one whose days passed easily.

If it’s Old Sophia does that make now New Sophia? I don’t think so. I’m not sure but I think now is Now Sophia.

Now Sophia is battling through each day, battling through the thoughts that fill her mind. There’s so much there, there’s so much to accumulate and process, there’s so much emotion, so much energy there.

It’s like there’s different people, people she has separated in her mind. There is the memory of Old Sophia, there is Now Sophia and there is always Show Sophia.

Show Sophia is the one that people see when Now Sophia is feeling low, when not everything’s going well. But that doesn’t mean Show Sophia is miserable, it’s the opposite, Show Sophia is bubbly, happy and lively. She’s the one that’s always there with a smile and a wave, always asking how you are, always feeling fabulous, if you ask her.

Show Sophia hides the pain, the difficulties, the struggles. Hides the strain that can be getting through each day.

All these Sophias are all there in one—in Sophia. All these Sophias are needed sometimes to understand what is going on, to deal with it and to carry on each day, to keep getting through. Each of these different parts of her combine, they’re all her, even if one is stronger on one day and another on another, each of these elements are what has made her, her.

Made her Sophia. The one who will continue to fight.

Betty pulls out the tissues, this is the second time I’ve made her cry and this time she’s prepared. She’s even got tissues for the friend sitting next to her whose eyes are also watering. I tell them that soon I’m going to be banned from speaking to any of the patients or their friends.

But she starts laughing again soon. Betty always laughs. Betty normally laughs at herself. Something she’s done or something she’s thought. But this is something I’ve often found when talking to people. Humour is a way of coping with things.

Dark humour, dry humour, self-humour. Anything to make light of it. Anything that undermines the issues, mocks it. It will be controlled, not the other way round. Humour is a way of making the disease your own, not you the disease’s.

Betty just takes it a step further. She laughs at everything and anything. Our conversations always make me smile. Life is not there to be taken too seriously, life is there to have fun.

‘And I’ll do it!’

Four words. Four words that can mean different things depending on how they’re said. Katy says them with such confidence, such surety that you can’t help believe her. Said by her, when she’s convinced, would persuade anyone that the impossible is possible.

She will prove people wrong, other’s expectations are there to be broken. There’s nothing that’ll motivate her to do something like being told that she can’t. Can’t is not a word that Katy knows or uses—can’t is something for those much less stubborn. Katy knows how to beat the odds, she’s not here to play someone else’s game. She’s here to play her own game under her own rules—to try and try again.

And she will. She will do it.

Specific illustrations of the use of humour and irony as part of a coping process are also illustrated in these individual quotations:

“And that is, that’s one of the hardest things, is not being able to know how long. Because nobody can say, but do I get my patio windows? Am I going to be able to live in the house for a length of time?” BP (female)

“They’re making jokes about how fat my tummy is and stuff.” CE (female)

“It’s best to laugh at it because [you] take control of it then. It’s yours to take the mick out of. My condition has me, I don’t have my condition.” BW (male)

Changing narratives

A narrative is not simply just written, or spoken, but is built up out of a person’s previous experiences and their expectations of the future. The microstories often provided a better representation of a narrative and an individual, providing greater information than individual quotes.

Beneath the surface

I sit and listen to what this gentleman is talking about. The things that worry him are little things, they’re not big worries, they only seem to highlight the privileged life that he’s led. His concerns reflect on things that most people don’t worry about. Not being able to organise fixing up the house doesn’t bother many people, for some paying the rent is enough.

But then I read through his transcript, then I look through it again. There’s not much there. It’s why the little things stood out. Because they’re the only things that are really there. Where’s everything else? At one point he thought he wasn’t leaving hospital. He thought he would die on the ward. He hasn’t said much about that.

How much hasn’t he said? What’s going on beneath the surface? What are his thoughts during the night when it’s dark and quiet on the ward? How much is this really hurting him?

Working things through

It’s so difficult knowing what’s going on in someone’s head. Often people don’t know themselves what’s going on, what they are working through subconsciously, what’s about to show its face. How can you always know?