Home — Essay Samples — War — Treaty of Versailles — How Could Ww2 Have Been Prevented

How Could WW2 Have Been Prevented

- Categories: Treaty of Versailles

About this sample

Words: 579 |

Published: Mar 19, 2024

Words: 579 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

I. introduction, ii. failure of the treaty of versailles, a. overview of the treaty of versailles, b. analysis of how the harsh terms of the treaty may have contributed to the rise of adolf hitler and the nazi party, c. discussion on how a more lenient or balanced treaty could have prevented the economic hardships and resentment that led to wwii.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: War

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1381 words

1 pages / 407 words

2 pages / 694 words

3 pages / 1195 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles, which marked the end of World War 1 (WWI), had a destabilizing effect on the German economy in the 1920s and created intense animosity between European powers. Ordinary citizens of Germany felt betrayed [...]

The Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919 at the end of World War I, is often regarded as one of the most controversial and contentious agreements in modern history. This treaty imposed harsh penalties on Germany, leading many to [...]

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914, otherwise known as “the shot heard round the world”, is widely recognized as the immediate cause of the First World War. However, while Ferdinand’s assassination [...]

The League of Nations was an organization there to maintain the peace in our world by solving disputes. However, have they really achieved their aim? Were they successful? According to historical facts, the League of Nation has [...]

Treaty of Versailles - The Treaty of Versailles ended World War I between Germany and the Allied Powers. Because Germany had lost the war, the treaty was very harsh against Germany. Germany was forced to "accept the [...]

After the World War I, President Wilson lead to the establishment of the League of Nations but was unable to guide the United States into this general society of states. Because the International Commission for Air Navigation [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

World War II Was Avoidable

Introduction.

World War II was a global war that lasted between 1939 and 1945. It was fought between two military alliances that included the Allies and the Axis. The Axis alliance comprised Japan, Italy, and Germany while the Allies alliance constituted France, the United States, Great Britain, and China. The war broke out two decades after World War I, which set the stage for another global conflict that would be more devastating.

The rise of Adolf Hitler to power created the foundation for the conflict. He became the leader at a time when Germany was economically and politically unstable. His National Sociality (Nazi) Party enhanced the nation’s military capacity, and Hitler entered into strategic agreements with Italy and Japan to support his world domination agenda. The conflict lasted for 16 years and led to millions of deaths and the massive destruction of property. Approximately 45-60 million people were killed, including the 6 million Jews that were murdered during the Holocaust. Despite its dire ramifications, World War II could have been avoided had the Allies stopped Hitler from expanding his empire.

The Treaty of Versailles

One of the major reasons given as a contributing factor to World War II was the Treaty of Versailles that was signed on 28 June 1919 in order to bring an end to World War I. It concluded the five-year bloody conflict between the Allied Powers and Germany and laid the foundation for what later became the Second World War (Freeman 34). Germany was viewed as a major antagonist in World War One and on the losing end.

Therefore, the Allied Powers included certain clauses in the Treaty of Versailles to punish the Germans for the atrocities that they had committed in the previous war. Moreover, the Allied Powers held the belief that Germany and its allies were responsible for the war and they would rearm their military and cause more damage if stringent measures were not implemented to avoid such an outcome (Overy 44). The terms of the treaty required Germany to give up 10 percent of its territory, undergo disarmament, pay reparation in ships, gold, securities, and commodities, and relinquish its overseas empire to the Allied powers (Freeman 35).

Germany gave up several empires and suffered a ruined economy after paying the reparations, according to the requirements of the “War Guilt Clause” (Overy 46). The financial depression that ensued thrust the government into chaos and the nation faced starvation as it was incapable of affording enough food for its population. Conscription was proscribed and the size of the German military was greatly limited (Freeman 35).

Clauses that demanded Germany to take responsibility for the war were included in the agreement. These clauses attained the intended objectives of their inclusion: reparations for the destructions cast Germany into a huge debt and consequent depression. As a result of the poor economic state, Germany had to find a way to revive the economy. War is a profitable endeavor, and Germany initiated a war to remedy its poor economic situation. World War II was caused by a myriad of factors. However, one of them was the Carthaginian peace that emanated from the Treaty of Versailles.

Impact of the Treaty

The treaty was aimed at ending the war and resolving the disputes that had led to the First World War. However, it prevented cooperation among European nations and intensified the underlying issues that had led to the conflict. The Germans, Austrians, Bulgarians, and the Hungarians viewed the Treaty as punishment (Overy 48). Therefore, they violated the limiting provisions of the agreement. The situation created a fertile ground for the rise of Hitler to power as his party promised the people that they would rearm the military, reclaim German territory, and gain prominence in international politics (Freeman 40). The promise to restore the economy and Germany’s prominence in international politics led to the election of Hitler, whose actions contributed to World War II.

Some historians argue that had the Treaty of Versailles not been as harsh to the Germans as it had been, the Second World War could have been avoided. Hitler was against the treaty because it had crippled Germany by placing numerous restrictions that hampered its economic and military expansion. The moves to rearm Germany, sign treaties with Italy, and expand his empire originated from a need to restore Germany (Overy 51).

Many Germans were against the radical tenets that the Nazi party held. However, the promise to restore Germany’s prominence among world powers motivated them to vote for Hitler. Had the Treaty of Versailles been fair to both Germany and its allies, the Second World War would never have occurred. Probably, Hitler would not have ascended to power because his election was founded on the hope of economic restoration that he offered to the people.

Adolf Hitler’s Rule

Hitler’s promise to restore Germany was his claim to power as the Germans wanted someone to revive the economy, empower the military, and reclaim the nation’s dignity. It was clear from the early days of Hitler’s rule that his major goal was to conquer the world and dominate. As mentioned earlier, the Allies created the Treaty of Versailles to punish Germany for its involvement in World War I. They pushed Germany into desperation and laid a foundation for future conflicts. The Allied powers did not respond accordingly when Hitler’s intentions of global domination became apparent. They should have stopped him and prevented the massive loss of lives and destruction of property that ensued from the Second World War.

Hitler’s actions were planned and strategic since the beginning of his rule, and his intentions became clearer as the years passed. For example, Germany violated the Treaty of Versailles regarding military training and armament, enlarged the army, nullified the treaty, and withdrew from the Conference for the Reduction and Limitation of Armaments (Freeman 56). In 1936, Hitler invaded and demilitarized Rhineland, thus violating the Locarno Pact that had been signed in 1925 (Overy 57).

These moves should have signaled Hitler’s aggression to the Allies. However, they ignored the overt violations of the treaties and overlooked his move to annex Austria into Nazi Germany. A preventive war against Hitler could have prevented the Second World War.

The Munich Agreement was another failure on the side of the Allies. It involved France, Germany, Great Britain, and Italy, and it allowed Germany to annex Sudetenland, without attacking Czechoslovakia (Overy 63). Hitler announced that the conquest would be his last bid to expand the German empire and the agreement was lauded as a peace milestone. However, several months later, Hitler took over Czechoslovakia, Slovakia, and the port city of Klaipeda (Freeman 58).

The Allied Powers foresaw Hitler conquering Poland because by this time, his intention of dominating the world had been made clear by his acts of aggression. However, they did not stop him as they chose to avoid a recurrence of the events of World War I. They adhered to a policy of appeasement as weaker nations suffered under the ruthless rule of Hitler. His actions were supported by the declaration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt that each nation had a right to determine its destiny (Overy 73). A war against Hitler was declared too late after he invaded Poland in 1939. ermany conquered Norway and Denmark and invaded France and Russia. During these invasions, the US ignored the conflicts but joined in later.

Anschluss in 1938

The annexation of Austria into a Greater Germany is one of the occurrences that could have been prevented, and as a result, avoided World War II. The annexation was an overt violation of the Treaty of Versailles that Hitler had unsuccessfully tried earlier, but failed because he had a weak army (Overy 77). In 1938, Hitler had a stronger army that was ready for war. Moreover, he did not meet with resistance from Italy because he had united with Mussolini and signed the Anti-Comintern Act a year earlier. Therefore, he was prepared for Anschluss. Hitler rallied the Nazi party in Austria to cause riots while demanding unity with Germany.

As the riots continued, Hitler pressured Chancellor Schuschnigg into giving in to his demands. Unsure of the decision to make, he reached out to France and Britain for assistance (Overy 91). However, the two nations made it clear that they were proponents of unity. After being ignored, the Chancellor held a vote so that the Austrian people could decide on the matter. Hitler gave the responsibility of overseeing the vote to German soldiers, whose main goal was to intimidate the voters. 99.75% of the people who participated in the practice voted to have Austria and Germany unite (Freeman 67).

The win was proof enough to Hitler that he was powerful enough to expand his empire and that the Allied powers would not oppose his moves to contravene the statutes of the Treaty of Versailles. If France and Britain had offered military assistance to Austria in order to stop the annexation, they would have stopped Hitler from advancing his agenda of conquering the world and creating tensions that caused another war. The outcome would have been different had the Allies declared war on Hitler during this moment rather than after he invaded Poland because by then, it was too late.

Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939 was followed by a 6-month period of the Phoney War that was characterized by conflicts on a minor scale. During this period, no bombs were dropped and fighting was minimal. Hitler had successfully expanded his empire without much opposition. Therefore, he did not expect the Allies to declare war on him after invading Poland (Freeman 76). At this time, Germany was not prepared for a major war, and Hitler could have been stopped.

World War II could have been avoided had the Allied Powers declared war on Hitler at this point. He would have probably backed down and signed peace treaties because his army was not strong enough to fight a major war. The Allies should have used their power to compel Hitler to adhere to the stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles. This could have led to a shorter and less disastrous war as Germany would probably fight back. The Phoney war was an indication that Germany was unwilling to fight after recovering from the aftermath of World War I. The Allies should have taken that as an indication that Germany was ready to avoid another war at all costs for purposes of self-preservation.

World War II was one of the most destructive global wars that could have been avoided. Millions of people were killed, including more than 6 million Jews. After the defeat of Germany in World War I, clauses were appended to the Treaty of Versailles to punish Germany as one of the main aggressors. The treaty was aimed at bringing peace. However, it treated Germany harshly, and as a result, destroyed its economy and military. The people starved and the economy disintegrated.

Hitler was elected because he gave the people hope by promising them to restore the economy and the nation’s former glory. The Allies could have stopped the War had they acted on Hitler’s infringement of the Treaty. However, they allowed him to rearm and expand his military, as well as invade other countries. They should have opposed his agenda of conquering the world, which was evident from the actions he took during the early years of his rule. World War II could have been avoided had the Allied Powers declared war on Hitler before he had rearmed his military and gained confidence by conquering other nations. For example, the Anschluss could have been stopped by France and Britain ignored Austria’s requests for assistance.

Works Cited

Freeman, Richard Z. A Concise History of the Second World War: Its Origin, Battles, and Consequences . Merriam Press, 2016.

Overy, Richard. The Origins of the Second World War . 4th ed., Routledge, 2017.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, January 26). World War II Was Avoidable. https://studycorgi.com/world-war-ii-was-avoidable/

"World War II Was Avoidable." StudyCorgi , 26 Jan. 2022, studycorgi.com/world-war-ii-was-avoidable/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'World War II Was Avoidable'. 26 January.

1. StudyCorgi . "World War II Was Avoidable." January 26, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/world-war-ii-was-avoidable/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "World War II Was Avoidable." January 26, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/world-war-ii-was-avoidable/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "World War II Was Avoidable." January 26, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/world-war-ii-was-avoidable/.

This paper, “World War II Was Avoidable”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: January 26, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

World War II showed that war must be avoided at all costs and democracies must resist aggression, says Stanford historian

World War II provided two contradictory lessons: war must be avoided at all costs and democracies must resist aggression, says Stanford historian James J. Sheehan .

On the 75th anniversary of “Victory in Europe Day” – the day when people from across the world celebrated the acceptance of Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender to the Allied forces of the United States, the United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union on May 8, 1945 – Sheehan discusses the difficult challenges ahead, despite war in Europe being over.

Sheehan is the Dickason Professor in the Humanities and Professor of History emeritus in the School of Humanities and Sciences. He is the author of Where Have All the Soldiers Gone? The Transformation of Modern Europe, a history of war and peace in 20th-century Europe.

Are there any elements to VE Day that you think have been largely forgotten, overlooked or misunderstood?

It is important to realize what actually occurred on May 8, 1945. Most wars end when one side either surrenders or agrees to a cease-fire. That is what happened on Nov. 11, 1918, when the representatives of the German government agreed to an armistice and then, seven months later, signed a peace treaty. On May 8, 1945, there was no German state recognized by its enemies. In three different places, the commanders of the German armed forces surrendered unconditionally. Civil and military authority in what had been the German state was assumed by the allies. Germany was divided among them. Although peace treaties were signed with Germany’s allies in 1947, a final treaty that recognized Germany as a fully sovereign state did not take place until 1991. One of the ironies of the postwar settlement is that, despite the absence of a formal peace treaty, it turned out to be so durable.

You have studied how, for centuries, war defined Europe’s narrative and affected every aspect of political, social and cultural life. How did World War II change Europe’s relationship to war?

In many ways, Europeans’ view of war was transformed by the First World War, which demonstrated the full destructive potential of modern combat. Pacificism, which had always been a fringe movement, now became much more widespread. Unfortunately, there were still those, like Adolf Hitler, who saw war as a necessary means of expanding their state and reorganizing their societies. Without Hitler, and the resources of Europe’s most powerful state, a second European war would not have happened. In 1939, when the war began in Europe, there was very little popular enthusiasm, even in Germany. People knew what modern war could mean, although few imagined just how devastating it would be.

How did World War II transform views on pacifism and militarism?

The war provided two contradictory lessons: the first was that war was to be avoided at all costs, the second was that democracies had to be ready to resist aggression. The second lesson led most western European states, including Germany, to rearm and join the Atlantic alliance. Gradually, as the European system evolved into a stalemate between the United States and the Soviet Union, each armed with nuclear weapons, the first lesson prevailed. By the 1970s, many Europeans feared a war between the two global superpowers, but few believed that war among the European states could ever happen again.

James Sheehan

Skip to Main Content of WWII

The great debate.

From our 21st-century point of view, it is hard to imagine World War II without the United States as a major participant. Before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, however, Americans were seriously divided over what the role of the United States in the war should be, or if it should even have a role at all. Even as the war consumed large portions of Europe and Asia in the late 1930s and early 1940s, there was no clear consensus on how the United States should respond.

Top Image Courtesy of the Associated Press

The US ambivalence about the war grew out of the isolationist sentiment that had long been a part of the American political landscape and had pervaded the nation since World War I. Hundreds of thousands of Americans were either killed or wounded during that conflict, and President Woodrow Wilson’s idealistic plan to ensure permanent peace through international cooperation and American leadership failed to become a reality. Many Americans were disillusioned by how little their efforts had accomplished and felt that getting so deeply involved on the global stage in 1917 had been a mistake.

Neither the rise of Adolf Hitler to power nor the escalation of Japanese expansionism did much to change the nation’s isolationist mood in the 1930s. Most Americans still believed the nation’s interests were best served by staying out of foreign conflicts and focusing on problems at home, especially the devastating effects of the Great Depression. Congress passed a series of Neutrality Acts in the late 1930s, aiming to prevent future involvement in foreign wars by banning American citizens from trading with nations at war, loaning them money, or traveling on their ships.

But by 1940, the deteriorating global situation was impossible to ignore. Nazi Germany had annexed Austria and Czechoslovakia and had conquered Poland, Belgium, the Netherlands, and France. Great Britain was the only major European power left standing against Hitler’s war machine. The urgency of the situation intensified the debate in the United States over whether American interests were better served by staying out or getting involved.

Isolationists believed that World War II was ultimately a dispute between foreign nations and that the United States had no good reason to get involved. The best policy, they claimed, was for the United States to build up its own defenses and avoid antagonizing either side. Neutrality , combined with the power of the US military and the protection of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, would keep Americans safe while the Europeans sorted out their own problems. Isolationist organizations like the America First Committee sought to influence public opinion through print, radio, and mass rallies. Aviator Charles Lindbergh and popular radio priest Father Charles Coughlin were the Committee’s most powerful spokesmen. Speaking in 1941 of an “independent American destiny,” Lindbergh asserted that the United States ought to fight any nation that attempted to meddle in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere. However, he argued, American soldiers ought not to have to “fight everybody in the world who prefers some other system of life to ours.”

Interventionists believed the United States did have good reasons to get involved in World War II, particularly in Europe. The democracies of Western Europe, they argued, were a critical line of defense against Hitler’s fast-growing strength. If no European power remained as a check against Nazi Germany, the United States could become isolated in a world where the seas and a significant amount of territory and resources were controlled by a single powerful dictator. It would be, as President Franklin Delano Roosevelt put it, like “living at the point of a gun,” and the buffer provided by the Pacific and Atlantic would be useless. Some interventionists believed US military action was inevitable, but many others believed the United States could still avoid sending troops to fight on foreign soil, if only the Neutrality Acts could be relaxed to allow the federal government to send military equipment and supplies to Great Britain. William Allen White, Chairman of an interventionist organization called the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, reassured his listeners that the point of helping Britain was to keep the United States out of the war. “If I were making a motto for [this] Committee,” he said, “it would be ‘The Yanks Are Not Coming.’”

Female isolationists from the America First Committee, Keep America Out of War, and the Mothers’ Crusade picket British Ambassador Lord Halifax in Chicago, May 8, 1941. (Image: Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock Photo, F2AWAM.)

"We well know that we cannot escape danger, or the fear of danger, by crawling into bed and pulling the covers over our heads."

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Public opinion polling was still in its infancy as World War II approached, but surveys suggested the force of events in Europe in 1940 had a powerful impact on American ideas about the war. In January of that year, one poll found that 88% of Americans opposed the idea of declaring war against the Axis powers in Europe. As late as June, only 35% of Americans believed their government should risk war to help the British. Soon after, however, France fell, and in August the German Luftwaffe began an all-out bombing campaign against Great Britain. The British Royal Air Force valiantly repelled the German onslaught, showing that Hitler was not invincible. A September 1940 poll found that 52% of Americans now believed the United States ought to risk war to help the British. That number only increased as Britain continued its standoff with the Germans; by April 1941 polls showed that 68% of Americans favored war against the Axis powers if that was the only way to defeat them.

Like this article? Read more in our online classroom.

From the Collection to the Classroom: Teaching History with The National WWII Museum

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, ended the debate over American intervention in both the Pacific and European theaters of World War II. The day after the attack, Congress declared war on Imperial Japan with only a single dissenting vote. Germany and Italy— Japan’s allies—responded by declaring war against the United States. Faced with these realities and incensed by the attack on Pearl Harbor, everyday Americans enthusiastically supported the war effort. Isolation was no longer an option.

The Attack On Pearl Harbor December 7, 1941

The National WWII Museum will commemorate the 80th anniversary of Pearl Harbor with 80 days of articles, oral histories, artifacts, and more.

Explore Further

The Fallen Crew of the USS Arizona and Operation 85

The Operation 85 project aims to identify unknown servicemen who perished aboard the USS Arizona during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

'Maxwell Opened My Eyes': Rosa Parks, WWII Defense Worker

Before her historic protest in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Rosa Parks was a Home Front worker at Maxwell Airfield.

Patchwork Plane: Building the P-47 Thunderbolt

Roughly 100 companies, coast to coast, helped Republic Aviation Corporation manufacture each P-47 Thunderbolt.

The Chopping Block: The Fate of Warplanes after WWII

After the war, hundreds of thousands of US warplanes remained—but the military needed only a fraction of them.

War Time: How America's Wristwatch Industry Became a War Casualty

Prior to World War II, there was a thriving American wristwatch industry, but it became a casualty of the war.

Standing against "Universal Death": The Russell–Einstein Manifesto

Penned by philosopher Bertrand Russell and endorsed by Albert Einstein, the document warned human beings about the existential threat posed by the new hydrogen bomb.

1936, a Year for the Worker: Factory Occupations and the Popular Front’s Victory in France

The election of the Popular Front government in France and a wave of factory occupations secured huge gains for French workers.

The Women's Army Corps and the Manhattan Project

Wilma Betty Gray's WAC journey began when she boarded a train, destination unknown. Her assignment was Oak Ridge, Tennessee, for the Manhattan Project.

The Debate Behind U.S. Intervention in World War II

73 years ago, President Roosevelt was mulling a third term, and Charles Lindbergh was praising German air strength. A new book looks at the dramatic months leading up to the election of 1940.

"DEAR FRISKY," President Roosevelt wrote in May 1940 to Roger Merriman, his history professor at Harvard and the master of Eliot House. "I like your word 'shrimps.' There are too many of them in all the Colleges and Universities -- male and female. I think the best thing for the moment is to call them shrimps publicly and privately. Most of them will eventually get in line if things should become worse."

To designate young isolationists, who deluded themselves into believing that America could remain aloof, secure, and distant from the wars raging in Europe, Roosevelt liked the amusing term "shrimps"-- crustaceans possessing a nerve cord but no brain. In that critical month of May 1940, he finally realized that it was probably a question of when, not if, the United States would be drawn into war. Talk about neutrality or noninvolvement was no longer seasonable as the unimaginable dangers he had barely glimpsed in 1936 erupted into what he termed a "hurricane of events."

On the evening of Sunday, May 26, 1940, days after the Germans began their thrust west, as city after city fell to the Nazi assault, a somber Roosevelt delivered a fireside chat about the dire events in Europe.

Earlier that evening, the president had distractedly prepared drinks for a small group of friends in his study. There was none of the usual banter. Dispatches were pouring into the White House. "All bad, all bad," Roosevelt grimly muttered, handing them to Eleanor to read. But in his talk, as he tried to prepare Americans for what might lie ahead, he set a reflective, religious tone.

"On this Sabbath evening," he said in his reassuring voice, "in our homes in the midst of our American families, let us calmly consider what we have done and what we must do." But before talking about his decision to vastly increase the nation's military preparedness, he hurled an opening salvo at the isolationists.

They came in different sizes and shapes, he explained. One group of them constituted a Trojan horse of pro-German spies, saboteurs, and traitors. While not naming names, he singled out those who sought to arouse people's "hatred" and "prejudices" by resorting to "false slogans and emotional appeals." With fifth columnists who sought to "divide and weaken us in the face of danger," Roosevelt declared, "we must and will deal vigorously." Another group of isolationists, he explained, opposed his administration's policies simply for the sake of opposition -- even when the security of the nation stood at risk.

The president recognized that some isolationists were earnest in their beliefs and acted in good faith. Some were simply afraid to face a dark and foreboding reality. Others were gullible, eager to accept what they were told by some of their fellow Americans, that what was happening in Europe was "none of our business." These "cheerful idiots," as he would later call them in public, naively bought into the fantasy that the United States could always pursue its peaceful and unique course in the world.

They "honestly and sincerely" believed that the many hundreds of miles of salt water would protect the nation from the nightmare of brutality and violence gripping much of the rest of the world. Though it might have been a comforting dream for FDR's "shrimps," the president argued that the isolationist fantasy of the nation as a safe oasis in a world dominated by fascist terror evoked for himself and for the overwhelming majority of Americans not a dream but a "nightmare of a people without freedom -- the nightmare of a people lodged in prison, handcuffed, hungry, and fed through the bars from day to day by the contemptuous, unpitying masters of other continents."

Two weeks after that fireside chat, on June 10, 1940, Roosevelt gave another key address about American foreign policy. This time it was in the Memorial Gymnasium of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, to an audience that included his son Franklin, Jr., who was graduating from the Virginia Law School. That same day, the president received word that Italy would declare war on France and was sending four hundred thousand troops to invade the French Mediterranean coast. In his talk, FDR deplored the "gods of force and hate" and denounced the treacherous Mussolini. "On this tenth day of June, 1940," he declared, "the hand that held the dagger has plunged it into the back of its neighbor."

Recommended Reading

You’re Showering Too Much

The Predator That Makes Great White Sharks Flee in Fear

Who Wins When Cash Is No Longer King?

But more than a denunciation of Mussolini's treachery and double-dealing, the speech finally gave a statement of American policy. It was time to "proclaim certain truths," the president said. Military and naval victories for the "gods of force and hate" would endanger all democracies in the western world. In this time of crisis, America could no longer pretend to be "a lone island in a world of force." Indeed, the nation could no longer cling to the fiction of neutrality. "Our sympathies lie with those nations that are giving their life blood in combat against these forces." Then he outlined his policy. America was simultaneously pursuing two courses of action. First, it was extending to the democratic Allies all the material resources of the nation; and second, it was speeding up war production at home so that America would have the equipment and manpower "equal to the task of any emergency and every defense." There would be no slowdowns and no detours. Everything called for speed, "full speed ahead!" Concluding his remarks, he summoned, as he had in 1933 when he first took the oath of office, Americans' "effort, courage, sacrifice and devotion."

It was a "fighting speech," wrote Time magazine, "more powerful and more determined" than any the president had yet delivered about the war in Europe. But the reality was actually more complicated.

On the one hand, the president had taken sides in the European conflict. No more illusions of "neutrality." And he had delivered a straightforward statement of the course of action he would pursue. On the other hand, he was not free to make policy unilaterally; he still had to contend with isolationists in Congress. On June 10, the day of his Charlottesville talk, with Germans about to cross the Marne southeast of Paris, it was clear that the French capital would soon fall. France's desperate prime minister, Paul Reynaud, asked Roosevelt to declare publicly that the United States would support the Allies "by all means short of an expeditionary force." But Roosevelt declined. He sent only a message of support labeled "secret" to Reynaud; and in a letter to Winston Churchill, he explained that "in no sense" was he prepared to commit the American government to "military participation in support of the Allied governments." Only Congress, he added, had the authority to make such a commitment.

"We all listened to you last night," Churchill wired the president the day after the Charlottesville address, pleading, as he had done earlier in May, for more arms and equipment from America and paring down his request for destroyers from "forty or fifty" to "thirty or forty." "Nothing is so important," he wrote. In answer to Churchill's urgent appeal, the president arranged to send what he cleverly called "surplus" military equipment to Great Britain. Twelve ships sailed for Britain, loaded with seventy thousand tons of bomber planes, rifles, tanks, machine guns, and ammunition-- but no destroyers were included in the deal. Sending destroyers would be an act of war, claimed Senator David Walsh of Massachusetts, the isolationist chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee. Walsh also discovered the president's plan to send twenty torpedo boats to Britain. Flying into a rage, he threatened legislation to prohibit such arms sales. Roosevelt backed down -- temporarily -- and called off the torpedo boat deal.

Even as Nazi troops, tanks, and planes chalked up more conquests in Europe, the contest between the shrimps and the White House was not over. On the contrary, the shrimps still occupied a position of formidable strength.

The glamorous public face and articulate voice of the isolationist movement belonged to the charismatic and courageous Charles Lindbergh. His solo flight across the Atlantic in May 1927 had catapulted the lanky, boyish, 25- year- old pilot onto the world stage. "Well, I made it," he said with a modest smile upon landing at Le Bourget airfield in Paris, as thousands of delirious French men and women broke through military and police lines and rushed toward his small plane. When he returned to New York two weeks later, flotillas of boats in the harbor, a squadron of twenty- one planes in the sky, and four million people roaring "Lindy! Lindy!" turned out to honor him in a joy-mad city, draped in flags and drenched in confetti and ticker tape. "No conqueror in the history of the world," wrote one newspaper, "ever received a welcome such as was accorded Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh yesterday."

On May 19, 1940, a week before the president gave his fireside chat denouncing isolationists and outlining plans to build up American defenses, Lindbergh had made the isolationist case in his own radio address. The United States was not in danger from a foreign invasion unless "American people bring it on" by meddling in the affairs of foreign countries. The only danger to America, the flier insisted, was an "internal" one.

Though the president had explained that the Atlantic and Pacific oceans could no longer provide safe boundaries and could not protect the American continent from attack, Lindbergh insisted that the two vast oceans did indeed guarantee the nation's safety. "There will be no invasion by foreign aircraft," he stated categorically in his reedy voice, "and no foreign navy will dare to approach within bombing range of our coasts." America's sole task, he underscored, lay in "building and guarding our own destiny." If the nation stuck to a unilateral course, avoided entanglements abroad, refrained from intervening in European affairs, and built up its own defenses, it would be impregnable to foreign incursions. In any case, he stressed, it was pointless for the United States to risk submerging its future in the wars of Europe, for the die had already been cast. "There is no longer time for us to enter this war successfully," he assured his radio audience.

Deriding all the "hysterical chatter of calamity and invasion," Lindbergh charged that President Roosevelt's angry words against Germany would lead to "neither friendship nor peace."

Friendship with Nazi Germany? Surely Lindbergh realized that friendship between nations signifies their mutual approval, trust, and assistance. But so starry- eyed was he about German dynamism, technology, and military might and so detached was he from the reality and consequences of German aggression and oppression that even on that day of May 19, when the headline in the Washington Post read, "NAZIS SMASH THROUGH BELGIUM, INTO FRANCE" and when tens of thousands of desperate Belgian refugees poured across the border into France, Lindbergh said he believed it would make no difference to the United States if Germany won the war and came to dominate all of Europe. " Regardless of which side wins this war ," he stated in his May 19 speech without a whiff of hesitation or misgiving, "there is no reason . . . to prevent a continuation of peaceful relationships between America and the countries of Europe." The danger, in his opinion, was not that Germany might prevail but rather that Roosevelt's antifascist statements would make the United States "hated by victor and vanquished alike." The United States could and should maintain peaceful diplomatic and economic relations with whichever side won the war. Fascism, democracy-- six of one, half a dozen of the other. His defeatist speech could not have been "better put if it had been written by Goebbels himself," Franklin Roosevelt remarked two days later.

As the mighty German army broke through French defenses and thundered toward Paris, the dominance of Germany in Europe seemed obvious, inevitable, and justified to Lindbergh. Why, then, he wondered, did Roosevelt persist in his efforts to involve the nation in war? "The only reason that we are in danger of becoming involved in this war," he concluded in his May 19 speech, "is because there are powerful elements in America who desire us to take part. They represent a small minority of the American people, but they control much of the machinery of influence and propaganda." It was a veiled allusion to Jewish newspaper publishers and owners of major Hollywood movie studios. He counseled Americans to " strike down these elements of personal profit and foreign interest." While his recommendation seemed to border on violence, he was also reviving the centuries-old anti-Semitic myth of Jews as stateless foreigners, members of an international conspiratorial clique with no roots in the "soil" and interested only in "transportable" paper wealth.

"The Lindberghs and their friends laugh at the idea of Germany ever being able to attack the United States," wrote radio correspondent William Shirer, stationed in Berlin. "The Germans welcome their laughter and hope more Americans will laugh." Also heartened by Lindbergh's words was the German military attaché in Washington, General Friedrich von Boetticher. "The circle about Lindbergh," von Boetticher wrote in a dispatch to Berlin, "now tries at least to impede the fatal control of American policy by the Jews." The day after Lindbergh's speech, the defiant Hollywood studio heads, Jack and Harry Warner, wrote to Roosevelt to assure him that they would "do all in our power within the motion picture industry . . . to show the American people the worthiness of the cause for which the free peoples of Europe are making such tremendous sacrifices."

Who could have foreseen in 1927 that Lindbergh, whose flight inspired a sense of transatlantic community and raised idealistic hopes for international cooperation, would come to embody the fiercest, most virulent brand of isolationism? Two years after his feat, Lindbergh gained entrée to the Eastern social and financial elite when he married Anne Morrow, the daughter of Dwight Morrow. A former J. P. Morgan partner and the ambassador to Mexico, Dwight Morrow would be elected as a Republican to the United States Senate in 1930, just before his death in 1931. Charles and Anne seemed to lead charmed lives-- until their 20- month- old son was snatched from his crib in their rural New Jersey home in March 1932. Muddy footprints trailed across the floor in the second-floor nursery to an open window, beneath which a ladder had stood. "The baby's been kidnapped!" cried the nurse as she ran downstairs. The governor of New York, Franklin Roosevelt, immediately placed all the resources of the state police at the disposal of the New Jersey authorities. Two months later, the small body was found in a shallow grave. A German- born carpenter who had served time in prison for burglary, Bruno Hauptmann, was charged with the crime; Lindbergh identified his voice as the one he heard shouting in the darkness of a Bronx cemetery when he handed over $50,000 in ransom.

Carrying a pistol visible in a shoulder holster, Lindbergh attended the trial in January 1935, sitting just a few seats away from the accused. After Hauptmann's conviction and move for an appeal, Eleanor Roosevelt oddly and gratuitously weighed in, second- guessing the jury and announcing that she was a "little perturbed" that an innocent man might have been found guilty. But the conviction stood, and Hauptmann would be executed in the electric chair in April 1936.

In December 1935, in the wake of the trial, Charles and Anne, harassed and sometimes terrified by intrusive reporters as well as by would- be blackmailers, fled to Europe with their 3-year-old son, Jon. "America Shocked by Exile Forced on the Lindberghs" read the three-column headline on the front page of the New York Times .

Would the crowd- shy Lindbergh and his wife find a calm haven in Europe? The Old World also has its gangsters, commented a French newspaper columnist, adding that Europe "suffers from an additional disquieting force, for there everyone is saying, 'There is going to be war soon.'" The Nazi press, however, took a different stance. "As Germans," wrote the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung with an absence of irony, "we cannot understand that a civilized nation is not able to guarantee the safety of the bodies and lives of its citizens."

For several years the Lindberghs enjoyed life in Europe, first in England, in a house in the hills near Kent, and later on a small, rocky island off the coast of Brittany. In the summer of 1936, the couple visited Germany, where they were wined and dined by Hermann Goering, second only to Hitler in the Nazi hierarchy, and other members of the party elite. Goering personally led Lindbergh on an inspection tour of aircraft factories, an elite Luftwaffe squadron, and research facilities. The American examined new engines for dive bombers and combat planes and even took a bomber up in the air. It was a "privilege" to visit modern Germany, the awestruck Lindbergh said afterward, showering praise on "the genius this country has shown in developing airships." Photographers snapped pictures of Charles and his wife, relaxed and smiling in Goering's home. Lindbergh's reports on German aviation overflowed with superlatives about "the astounding growth of German air power," "this miraculous outburst of national energy in the air field," and the "scientific skill of the race ." The aviator, however, showed no interest in speaking with foreign correspondents in Germany, "who have a perverse liking for enlightening visitors on the Third Reich," William Shirer dryly noted.

In Berlin, Lindbergh's wife, Anne, was blinded by the glittering façade of a Potemkin village. She was enchanted by "the sense of festivity, flags hung out, the Nazi flag, red with a swastika on it, everywhere , and the Olympic flag, five rings on white." The Reich's dynamism was so impressive. "There is no question of the power, unity and purposefulness of Germany," she wrote effusively to her mother, adding that Americans surely needed to overcome their knee-jerk, "puritanical" view that dictatorships were "of necessity wrong, evil, unstable." The enthusiasm and pride of the people were "thrilling." Hitler himself, she added on a dreamy, romantic note, "is a very great man, like an inspired religious leader-- and as such rather fanatical-- but not scheming, not selfish, not greedy for power, but a mystic, a visionary who really wants the best for his country and on the whole has rather a broad view."

On August 1, 1936, Charles and Anne attended the opening ceremonies of the Olympic Games in Berlin, sitting a few feet away from Adolf Hitler. As the band played "Deutschland über alles," blond- haired little girls offered bouquets of roses to the Führer, the delighted host of the international games. Theodore Lewald, the head of the German Organizing Committee, declared the games open, hailing the "real and spiritual bond of fi re between our German fatherland and the sacred places of Greece founded nearly 4,000 years ago by Nordic immigrants." Leaving the following day for Copenhagen, Lindbergh told reporters at the airport that he was "intensely pleased" by what he had observed. His presence in the Olympic Stadium and his warm words about Germany helpfully added to the luster and pride of the Nazis. Also present at the Olympic games, William Shirer overheard people in Nazi circles crow that they had succeeded in "making the Lindberghs 'understand' Nazi Germany."

In truth, Lindbergh had glimpsed a certain unsettling fanaticism in Germany, but, as he reasoned to a friend, given the chaotic situation in Germany after World War I, Hitler's achievements "could hardly have been accomplished without some fanaticism." Not only did he judge that the Führer was "undoubtedly a great man," but that Germany, too, "has more than her share of the elements which make strength and greatness among nations." Despite some reservations about the Nazi regime, Lindbergh believed that the Reich was a "stabilizing factor" in Europe in the 1930s. Another visit to Germany in 1937 confirmed his earlier impressions. German aviation was "without parallel in history"; Hitler's policies "seem laid out with great intelligence and foresight"; and any fanaticism he had glimpsed was offset by a German "sense of decency and value which in many ways is far ahead of our own ."

In the late spring of 1938, Lindbergh and his wife moved to the tiny Breton island of Illiec, where Charles could carry on lengthy conversations with his neighbor and mentor, Dr. Alexis Carrel, an award-winning French scientist and eugenicist who instructed the flier in his scientific racism. In his 1935 book Man, the Unknown , Carrel had laid out his theories, his criticism of parliamentary democracy and racial equality. Asserting that the West was a "crumbling civilization," he called for the "gigantic strength of science" to help eliminate "defective" individuals and breeds and prevent "the degeneration of the [white] race." In the introduction to the German edition of his book, he praised Germany's "energetic measures against the propagation of retarded individuals, mental patients, and criminals."

In the fall of 1938, Charles and Anne returned to Germany. In October, at a stag dinner in Berlin hosted by the American ambassador and attended by the Italian and Belgian ambassadors as well as by German aircraft designers and engineers, Goering surprised the aviator by bestowing on him, "in the name of the Führer," Germany's second- highest decoration, a medal-- the Service Cross of the Order of the German Eagle-- embellished with a golden cross and four small swastikas. Lindbergh wore it proudly that evening. Afterward, when he returned from the embassy, he showed the medal to Anne, who correctly predicted that it would become an "albatross."

The Lindberghs wanted to spend the winter in Berlin, and Anne even found a suitable house in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee. They returned to Illiec to pack up for the move, but changed their plans when they learned of Kristallnacht. "My admiration for the Germans is constantly being dashed against some rock such as this," Lindbergh lamented in his diary, expressing dismay at the persecution of Jews at the hands of Nazi thugs. Concerned that their taking up residence in Berlin might cause "embarrassment" to the German and American governments, he and Anne rented an apartment in Paris instead. And yet, Lindbergh's deep admiration for Germany was not seriously dampened. On the contrary, crossing the border from Belgium into Germany in December 1938, Lindbergh was captivated by the fine-looking young German immigration officer whose "air of discipline and precision," he wrote, was "in sharp contrast to the easygoing pleasantness of Belgium and France." Germany still offered the striking image of the virility and modern technology he prized. The spirit of the German people, he told John Slessor, a deputy director in Britain's Air Ministry, was "magnificent"; he especially admired their refusal to admit that anything was impossible or that any obstacle was too great to overcome. Americans, he sighed, had lost that strength and optimism. Strength was the key to the future. It appeared eminently rational and fair to Charles Lindbergh that Germany should dominate Europe because, as he wrote, "no system . . . can succeed in which the voice of weakness is equal to the voice of strength."

In April 1939, Lindbergh returned to the United States, his wife and two young sons following two weeks later. A few years earlier he had discussed with his British friends the possibility of relinquishing his American citizenship, but now he decided that if there was going to be a war, he would remain loyal to America. Even so, on the same day that he and Anne discussed moving back to America, he confessed in his diary that, of all the countries he had lived in, he had "found the most personal freedom in Germany." Moreover, he still harbored "misgivings" about the United States; critical of the shortsightedness and vacillation" of democratic statesmen, he was convinced that, in order to survive in the new totalitarian world, American democracy would have to make "great changes in its present practices."

Back on American soil in April, Lindbergh immediately launched into a tireless round of meetings with scientists, generals, and government officials, spreading the word about the remarkable advances in aviation he had seen in Germany and pushing for more research and development of American air and military power. Though he believed in American isolation, he also believed in American preparedness.

On April 20, 1939, Lindbergh had a busy day in Washington: first a meeting with Secretary of War Harry Woodring and then one with President Roosevelt at the White House. After waiting for forty-five minutes, the aviator entered the president's office. "He is an accomplished, suave, interesting conversationalist," Lindbergh wrote later that day in his diary. "I liked him and feel that I could get along with him well." But he suspected that they would never agree on "many fundamentals" and moreover sensed that there was "something about him I did not trust, something a little too suave, too pleasant, too easy. . . . Still, he is our President," Lindbergh concluded. He would try to work with him, he noted, cautiously adding that "I have a feeling that it may not be for long."

Emerging after half an hour from a side exit of the executive mansion, Lindbergh found himself besieged by photographers and reporters. The boisterous scene was "disgraceful," the camera- shy aviator bitterly judged. "There would be more dignity and self-respect among African Savages." After their meeting, neither Lindbergh nor the White House would shed any light on what had been discussed. Rumors would later surface that, at that April meeting or several months later, the president had offered the aviator a cabinet appointment, but such rumors were never substantiated.

From the White House that April day, Lindbergh went to a session of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and spoke about the importance of establishing a program to develop technologically advanced aircraft. While he backed the NACA's recommendation that the government allocate $10 million for a West Coast research center, not even that represented sufficient progress in Lindbergh's mind. It would still leave the United States "far behind a country like Germany in research facilities," he wrote in his diary. "We could not expect to keep up with the production of European airplanes as long as we were on a peacetime basis."

Lindbergh was unrelenting in his message about military preparedness. One scientist who listened carefully to him was Vannevar Bush, the chairman of the NACA and head of the Carnegie Institution, a research organization in Washington. After several more meetings that spring, the two men agreed that a plan was needed to revive the NACA. Bush "soaked up" Lindbergh's opinions, wrote Bush's biographer G. Pascal Zachary. Indeed, so impressed was Bush that he offered Lindbergh the chairmanship or vice chairmanship of the NACA-- an offer he aviator declined. Early in 1940 Bush received another report from Lindbergh that repeated his alarm about a serious lack of engine research facilities in the United States and called for "immediate steps to remedy this deficiency."

Deeply concerned after reading Lindbergh's recommendations, Bush drafted a proposal for the creation of a National Defense Research Council (NDRC), an organization that would supervise and fund the work of American engineers and scientists. On June 12, 1940, Bush met for the first time with President Roosevelt in the Oval Office. He handed him his memo--four short paragraphs on a single sheet of paper. It was enough, one of Bush's colleagues later wrote, to convince the president of the need to harness technology for possible war. Taking out his pen, he wrote on the memo the magical words, "OK-- FDR."

During the war, two thirds of the nation's physicists would be working under Vannevar Bush. One of the secret projects he supervised until 1943, when it was turned over to the army, was known as Section S1. The S1 physicists sought to unlock energy from the fission of atoms of a rare isotope of uranium. And among the starting places for that work as well as for Bush's creation of the NDRC were his informative and disturbing conversations with Charles Lindbergh.

In June 1940, as France fell to Nazi troops and planes, Lindbergh turned to memories of his father for reassurance and wisdom. "Spent the evening reading Father's Why Is Your Country at War? " he wrote in his diary. That 1917 book justified the son's alarm at the prospect of America's entry into another European war. Charles Lindbergh, Sr., a progressive Minnesota Republican who died in 1924, had served in the House of Representatives from 1907 to 1917. His young son, Charles, ran errands and addressed letters for him and occasionally was seen in the House gallery, watching his father on the floor below. Although Lindbergh, Sr., had been a follower of Theodore Roosevelt, on the question of American participation in the First World War, he and the bellicose TR parted company.

Why Is Your Country at War? was a long- winded, turgid antiwar tract, arguing that the United States had been drawn into the war by the machinations of "cowardly politicians," wealthy bankers, and the Federal Reserve Bank. The senior Lindbergh did not oppose the violence of war per se. Rather, this midwestern agrarian railed against the injustice of a war organized and promoted as a for-profit enterprise by the "wealth grabbers" of Wall Street, people like the Morgans and the Rockefellers. Ironically, the men of the "power elite" whom he most despised might have included his son's future father- in-law, Dwight Morrow, a Morgan partner-- though Lindbergh, Jr., later told an interviewer that he believed that his father and Dwight Morrow would probably have liked each other. At bottom, the elder Lindbergh's screed was a rambling, populist, socialist primer that offered radical remedies for the twin evils of war and capitalism.

When his book appeared in print, Lindbergh, Sr., had to defend himself--not against the charge that he was anticapitalist, which would have been true, but rather against the charge that he was pro- German. He was hung in effigy and taunted as a "friend of the Kaiser." Though there was nothing pro-German in the book, the accusations contributed to his defeat when he ran for governor of Minnesota in 1918. "If you are really for America first," he wrote in his own defense, "then you are classed as pro-German by the big press[es] which are supported by the speculators."

Like his father, Charles Lindbergh, Jr., would also face allegations that he was pro-German. But in his case the indictment rang true.

In the aviator's mind, Germany had it made. In England there was "organization without spirit," he would tell a radio audience in August 1940. "In France there was spirit without organization; in Germany there were both." Indeed, the more Lindbergh had lived among the English people, the less confidence he had in them. They struck him, he wrote, as unable to connect to a "modern world working on a modern tempo." And sadly, he judged that it was too late for them to catch up, "to bring back lost opportunity." Britain's only hope, as he once mentioned to his wife, was to learn from the Germans and to adopt their methods in order to survive. Nor did he have confidence or respect for democracy in the United States. On the American continent, he felt surrounded by mediocrity. Writing in his diary in the summer of 1940, he bemoaned the decline of American society--"the superficiality, the cheapness, the lack of understanding of, or interest in, fundamental problems." And making the problems worse were the Jews. "There are too many places like New York already," he wrote, alluding to that city's Jewish population. "A few Jews add strength and character to a country, but too many create chaos. And we are getting too many."

Was Lindbergh a Nazi? He was "transparently honest and sincere," remarked Sir John Slessor, the Royal Air Force marshal who met several times with Lindbergh. It was Lindbergh's very "decency and naiveté," Slessor later said, that convinced him that the aviator was simply "a striking example of the effect of German propaganda." One of Lindbergh's acquaintances, the journalist and poet Selden Rodman, also tried to explain the aviator's affinity for Nazi Germany. "Perhaps it is the conservatism of his friends and the aristocratic racial doctrines of Carrel that have made him sympathetic to Nazism," Rodman wrote. "Perhaps it is the symbolism of his lonely flight and the terrible denouement of mass-worship and the kidnapping that have driven him to the unpopular cause because it is unpopular; that always makes the Byronic hero spurn fame and fortune for guilt and solitary persecution."

For his part, Lindbergh knew that many of his views were unpopular in certain circles, but, as he told a nationwide radio audience in 1940, "I would far rather have your respect for the sincerity of what I say than attempt to win your applause by confining my discussion to popular concepts." Mistaking sincerity for intelligence and insight, he considered himself a realist who grasped that German technological advances had profoundly and irrevocably altered the balance of power in Europe. The only issue, he once explained to Ambassador Joseph Kennedy, was "whether this change will be peaceably accepted, or whether it must be tested by war." Priding himself on his clear- eyed understanding of military strength, he darkly predicted in June 1940, before the Battle of Britain had even begun, that the end for England "will come fast." The playwright Robert Sherwood, whom FDR would draft in the summer of 1940 to join his speechwriting team, may have come closest to the truth about Lindbergh. The aviator, he dryly commented, had "an exceptional understanding of the power of machines as opposed to the principles which animate free men." As Sherwood suggested, Lindbergh may simply have been naive about politics, ignorant about history, uneducated in foreign policy and national security, and deluded by his infatuation with German technology and vigor. Perhaps he did not fully appreciate, Sherwood said, the extent to which the German people "are now doped up with the cocaine of world revolution and the dream of world domination."

Despite his exuberant enthusiasm for Germany, his disenchantment with democracy, the zealous applause he received from fascists in the United States and in Germany, his admiration for the racial ideas of Alexis Carrel, his increasingly extremist and anti- Semitic speeches, and the fact that his simplistic views mirrored Nazi propaganda in the United States, Lindbergh seemed to want what he believed was best for America. And yet Franklin Roosevelt may have been instinctively correct in his own less nuanced view.

"I am absolutely convinced that Lindbergh is a Nazi," FDR said melodramatically to his secretary of the treasury and old Dutchess County neighbor and friend, Henry Morgenthau, in May 1940, two days after Lindbergh's May 19 speech. "If I should die tomorrow, I want you to know this." The president lamented that the 38-year-old flier "has completely abandoned his belief in our form of government and has accepted Nazi methods because apparently they are efficient."

Others in the White House shared that assessment. Lindbergh, Harold Ickes sneered, pretentiously posed as a "heavy thinker" but never uttered "a word for democracy itself." The aviator was the "Number 1 Nazi fellow traveler," Ickes said. The delighted German embassy wholeheartedly agreed. "What Lindbergh proclaims with great courage," wrote the German military attaché to his home office in Berlin, "is certainly the highest and most effective form of propaganda." In other words, why would Germany need a fifth column in the United States when it had in its camp the nation's hero, Charles Lindbergh?

This is an excerpt from 1940: FDR, Willkie, Lindbergh, Hitler--the Election amid the Storm , by Susan Dunn, published by Yale University Press, 2013.

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

World War II showed that war must be avoided at all costs and democracies must resist aggression, says Stanford historian

On the 75th anniversary of World War II ending in Europe, Stanford historian James Sheehan discusses the challenges that persisted and the legacies that remained at the end of the war.

World War II provided two contradictory lessons: war must be avoided at all costs and democracies must resist aggression, says Stanford historian James J. Sheehan .

James Sheehan (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

On the 75th anniversary of “Victory in Europe Day” – the day when people from across the world celebrated the acceptance of Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender to the Allied forces of the United States, the United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union on May 8, 1945 – Sheehan discusses the difficult challenges ahead, despite war in Europe being over.

Sheehan is the Dickason Professor in the Humanities and Professor of History emeritus in the School of Humanities and Sciences. He is the author of Where Have All the Soldiers Gone? The Transformation of Modern Europe , a history of war and peace in 20th-century Europe.

Are there any elements to VE Day that you think have been largely forgotten, overlooked or misunderstood?

It is important to realize what actually occurred on May 8, 1945. Most wars end when one side either surrenders or agrees to a cease-fire. That is what happened on Nov. 11, 1918, when the representatives of the German government agreed to an armistice and then, seven months later, signed a peace treaty. On May 8, 1945, there was no German state recognized by its enemies. In three different places, the commanders of the German armed forces surrendered unconditionally. Civil and military authority in what had been the German state was assumed by the allies. Germany was divided among them. Although peace treaties were signed with Germany’s allies in 1947, a final treaty that recognized Germany as a fully sovereign state did not take place until 1991. One of the ironies of the postwar settlement is that, despite the absence of a formal peace treaty, it turned out to be so durable.

You have studied how, for centuries, war defined Europe’s narrative and affected every aspect of political, social and cultural life. How did World War II change Europe’s relationship to war?

In many ways, Europeans’ view of war was transformed by the First World War, which demonstrated the full destructive potential of modern combat. Pacificism, which had always been a fringe movement, now became much more widespread. Unfortunately, there were still those, like Adolf Hitler, who saw war as a necessary means of expanding their state and reorganizing their societies. Without Hitler, and the resources of Europe’s most powerful state, a second European war would not have happened. In 1939, when the war began in Europe, there was very little popular enthusiasm, even in Germany. People knew what modern war could mean, although few imagined just how devastating it would be.

How did World War II transform views on pacifism and militarism?

The war provided two contradictory lessons: the first was that war was to be avoided at all costs, the second was that democracies had to be ready to resist aggression. The second lesson led most western European states, including Germany, to rearm and join the Atlantic alliance. Gradually, as the European system evolved into a stalemate between the United States and the Soviet Union, each armed with nuclear weapons, the first lesson prevailed. By the 1970s, many Europeans feared a war between the two global superpowers, but few believed that war among the European states could ever happen again.

As the world remembers 75 years since VE Day, what legacies remain today?

On May 8, 1945, the Allied forces of the United States, the United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union officially accepted the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany. “Victory in Europe Day,” commonly known as “VE Day,” was celebrated across Europe, America and other parts of the world. (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons)

VE Day has a different meaning in each of the countries involved in the war. For Americans, it recalls a moment of triumph, a time to remember the accomplishments and sacrifices that made victory possible. The Second World War has a moral clarity for Americans that is not shared by the other participants, in large part because the U.S. was the only one to emerge from the war with greater wealth and power. Britain remembers the resolve personified by [Prime Minister Winston] Churchill, but the cost of the war was great and the immediate postwar years were dreary. For the British, the legacy of 1945 is less potent than that of 1918. For them, Nov. 11, not May 8, is the most important day of national commemoration. In France, the war left a complicated legacy. After the French armies were defeated in a matter of weeks in 1940, France was allied with Germany. French president Charles de Gaulle managed to transform this dismal record into a legacy of resistance and regeneration, but the truth of France’s wartime role keeps intruding on this legend. For Germans, the war ended in the midst of enormous destruction and death. Only as Germany (especially in the western half) began to recover could May 1945 seem like a new beginning rather than a catastrophic end. May 8, 1945, is especially important for Russians, whose suffering was greatest and whose contribution to the German defeat was the most significant. This is why Putin planned to have a great celebration in Moscow this year that was designed to remind Russians of what they had done and what they could do again.

What would you say to your current students about VE Day?

May 8, 1945, began the longest period of peace in European history. We should not take the absence of war for granted, nor should we lose sight of the policies that made a peaceful Europe possible and the vigilance that is still necessary to preserve it. The establishment of peace, the British historian Michael Howard wrote, “is a task which has to be tackled afresh every day of our lives … no formula, no organization and no political or social revolution can ever free mankind from this inexorable duty.” The Second World war reminds us how essential this task remains.

- Official Biography

- The Churchill Documents

- Book Reviews

- Bibliography

- Annotated Bibliography: Works About WSC

- The Churchill Timeline,1874-1977

- Churchill on Palestine, 1945-46

- Road to Israel, 1947-49

- The Art of Winston Churchill Gallery

- Churchill Conference Archive

- Dramatizations

- Documentaries

Churchill and the Rhineland: “They Had Only to Act to Win”

- By RICHARD M. LANGWORTH

- | September 14, 2023

- Category: Churchill Between the Wars Explore

“We dedicate ourselves to achieving an understanding between the peoples of Europe and particularly an understanding with our Western peoples and neighbors. After three years, I believe that, with the present day, the struggle for German equal rights can be regarded as closed…. We have no territorial claims to make in Europe.” —Adolf Hitler to the Reichstag after reoccupying the Rhineland, 7 March 1936. Following this speech, Hitler dissolved the Reichstag.

The Rhineland challenge

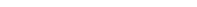

The Rhineland in western Germany is bordered by the River Rhine in the east and France and the Benelux countries in the west. It includes the industrial Ruhr Valley, the famous cities of Aachen, Bonn, Cologne, Düsseldorf, Essen, Koblenz, Mannheim and Weissbaden, and several bridgeheads into Germany proper.

After the end of the First World War, the Rhineland was occupied by the victorious Allies. Though the occupation was set to last through 1935, military forces withdrew in 1930 as a good-will gesture to the Weimar Republic. 1 The Allies retained the right to reoccupy the Rhineland should Germany violate the Treaty of Versailles .

In March 1936, a few thousand German troops marched into the Rhineland while the populace waved swastika flags. The soldiers had orders to “turn back and not to resist” if challenged by the all-dominant French Army. Hitler later said that the forty-eight hours following his action were the tensest of his life. 2

Since the occupied Saarland had been returned to Germany after a plebiscite in January 1935, the Rhineland was Hitler’s first foray into territory where he was not permitted. Churchill’s defenders correctly cite the Rhineland as confirming his warnings about Hitler. But what Churchill actually proposed to do about it is not as clear. 3

“Confronted by terrible circumstances”

Two months before Hitler’s action, Churchill predicted that a Rhineland incursion would raise “a very grave European issue, and no one can tell what would come of it…. The League of Nations Union folk, who have done their best to get us disarmed, may find themselves confronted by terrible circumstances.” 4

Hitler’s future foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop , recorded how Hitler conceived of slipping the occupation past the Western allies. Summoning Ribbentrop in January, Hitler said: “[I]t occurred to me last night how we can occupy the Rhineland without any friction. We return to the League!” 5 Germany had left the League of Nations in 1933.

Ribbentrop said he too (of course) had just had this very idea. He suggested they strike while the French and British were on one of their weekend holidays. Hitler acted on Saturday March 7th. France, he said had abrogated the Rhine agreements by a military alliance with Russia: “The Locarno Rhine Pact has lost its meaning and ceased in practice to exist.” 6

True to plan, Hitler added a sweetener, proposing “a real pacification of Europe between states that are equal in rights.” Germany would return to the League of Nations, provided her colonies, stripped at Versailles, were returned.

Would France march?

The question turned on France. Would she now reassert control of the Rhineland? Or just dither and do nothing? Anthony Eden , Britain’s foreign secretary, was sanguine: Great Britain would stand by France, and he offered military staff conversations.

Unfortunately for staff conversations, the French military was led by General Maurice Gamelin , a “nondescript fonctionnaire .” Under pressure, “he became everything a commander ought not to be: indecisive, given to issuing impulsive orders which he almost always countermanded, and timid to and beyond a fault.” 7 The French government may have yearned for a way to stop Hitler. Gamelin and his military colleagues were more worried about stopping him from invading France proper. 8

British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin believed France was unwilling to act—with or without Britain. Churchill doubted this, given the resolve of French Foreign Minister Pierre Flandin . Four days after Hitler’s action Flandin visited London. Churchill recalled:

He told me he proposed to demand from the British Government simultaneous mobilisation of the land, sea, and air forces of both countries, and that he had received assurances of support from all the nations of the “Little Entente” [Czechoslovakia, Rumania and Yugoslavia] and from other States. He read out an impressive list of the replies received. There was no doubt that superior strength still lay with the Allies of the former war. They had only to act to win. 9

Baldwin’s reluctance

Churchill urged Flandin to press his views with Baldwin, who was unsympathetic. He knew little of foreign affairs, he said, but he did know the British people wanted peace. Flandin replied that if Germany could tear up Locarno, what use were treaties? The French people were resolved, he said: “everything was at stake.” All Flandin asked of his British ally was a “free hand.” 10 But Baldwin doubted that Flandin had the support of his cabinet in Paris.

Flandin modified his plea. Suppose the Anglo-French “invite” Hitler to leave, pending negotiations, which would probably restore the Rhineland to Germany anyway? Even this was too much for Baldwin. “I have not the right to involve England,” he said. “Britain is not in a state to go to war.” Flandin was deflated, and as Baldwin suspected, the French cabinet was divided. 11

Some have suggested that Flandin never really wanted French military action—merely sanctions by the League of Nations . But sanctions were not forthcoming. Perhaps Flandin merely proposed to convene the League Council and adopt “sanctions by stages.” 12 Baldwin remained unmoved.