As a traditional introduction to a solving season, the 19th International Solving Contest (ISC) will be held this Sunday, January 29. A set of chess problems will be simultaneously offered to more than 500 solvers around the world at 11 AM CET. The local controllers will be responsible for the legality of the results on site, while the central controllers Axel Steinbrink (Germany) and Luc Palmans (Belgium), will do the hard work of checking scanned solving sheets sent from all competitions. Chess composition lives on enthusiasm and voluntary work, even when it comes to such a huge project.

The ISC type of hybrid solving competition is becoming increasingly popular since it allows enthusiasts from many countries to participate without extra costs. In 2023, the ISC will reach 42 locations in 26 different countries: Belgium, Brazil, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Great Britain, Georgia, Germany, Greece, India, Israel, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Mongolia, Netherlands, North Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Switzerland.

There are three ISC categories ranging by format and levels of difficulty. Category 1 is for the most ambitious solvers, Category 2 is for solvers rated up to 2000, and Category 3 is for U13 solvers born in 2010 and later.

The first two categories count for the solvers rating. They include 12 problems split into two rounds of 120 minutes each. There will twelve problems, two from each of the six different genres: mate in 2, mate in 3, mate in more moves, endgame, helpmate and selfmate.

Category 3 is a youth competition aimed at popularizing composition and discovering new talents. It lasts 120 minutes and includes six problems: 4 in 2 moves, 1 in 3 moves, and 1 endgame.

ISC is a relaxed and joyful event whose primary mission is to spread the beauty of chess art. You can see people of all ages, races and backgrounds joining it in very different ways.

To test your solving skills and feel the atmosphere of this competition you can tackle two entries from the previous 2022 ISC edition.

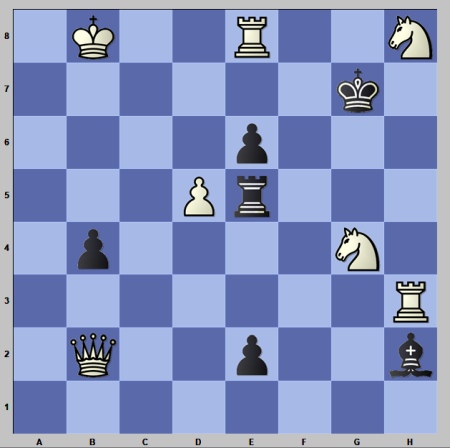

The first one is a hard nut to crack from Category 3:

1) White to play and mate in 2 moves

(HINT: We are searching for an unconventional move)

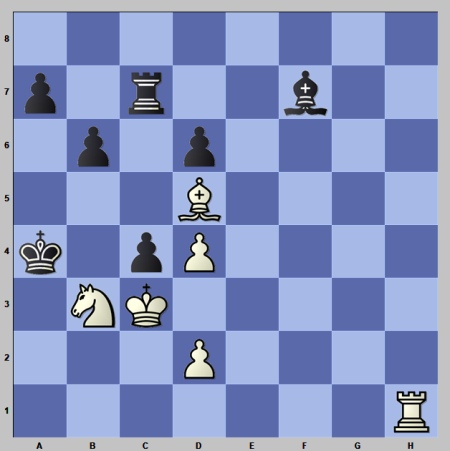

The next endgame was on the table for Category 2:

2) White to play and win

(HINT: White is a piece up, but cxb3+ is a huge threat. Is it possible to coordinate pieces and take advantage of Black’s king vulnerable position?)

You can find more ISC details on the Solving page of the World Federation for Chess Composition .

Soon after the 19th ISC, the season of national solving championships will begin. Most of them are open for foreign participants, as the legs of the yearly World Solving Cup.

The first one to come is the Finnish Chess Solving Championship, held annually since 1980. It will take place on Saturday, February 18, at Chess Arena in Helsinki. The announcement is published on the WFCC homepage, in the section World Solving Cup 2022-2023.

The Finnish championship lasts three hours (from 1 to 4 PM in 2023) and is conducted in one session with 12-15 problems to be solved. There will also be a B-group for young and/or less experienced solvers with only orthodox mates and studies. The director of the competition, Neal Turner, a long-time Secretary of the WFCC, has been devoted to solving competitions in Finland for decades.

The Finish Chess Problem Society (Suomen Tehtäväniekat) was established in 1935. From the 1st World Chess Solving Championship (WCSC) 1977, Finnish solvers were dominating. In the years 1977-95, their national team, led by Pauli Perkonoja , collected seven gold medals. This long-standing record was matched by the German team in 2002 and broken by the Polish squad in 2016. (Poland won 12 out of the last 13 WCSCs).

In 1982 Pauli Perkonoja (born 1941) became the first solver to be granted the title of International Solving Grandmaster of the FIDE. He won the individual competition of the WCSC seven times (the first four times, it was an unofficial title). At the age of 64, Pauli won the 1st European Chess Solving Championship and soon after withdrew from international competitions.

Finland has produced two more World Champions and Solving Grandmasters. Kari Valtonen won WCSC 1984, and Jorma Paavilainen did it in 2001. International Solving Master Harri Hurme (1945-2019) was an irreplaceable member of the golden national team.

Pauli Perkonoja still holds the Finnish record with 14 domestic titles, ahead of Jorma Paavilainen and Kari Karhunen, who won the national championship ten times each.

The Finnish Chess Problem Society produces chess problem books and a high-quality magazine,” Tehtäväniekka ”, edited by Jorma Paavilainen. The Society has been represented in the World Federation for Chess Composition by Hannu Harkola, now WFCC Honorary Member. A tireless worker on behalf of chess composition, Harkola has been involved in its international organization for more than 50 years.

The solutions to the problems from the ISC 2022

1: (F. Giegold National Zeitung 1971) 1.Rc3 ! threatening with Rc7#; 1…bxc3 2.Qb7#

2: (Minski, Hergert original for ISC 2 022) 1.Bc6! Rxc6 2.d5! Bxd5 3.Ra1+ Kb5 4.Nd4+ Kc5 5.Rb1! (threatening with 6.Rb5#) a6 6.Rb5+! axb5 7.Nb3+ cxb3 8.d4#!

Official website: https://www.wfcc.ch/

A knack for problem-solving?

It is the program of choice for anyone who loves the game and wants to know more about it. Start your personal success story with ChessBase and enjoy the game even more.

ONLINE SHOP

Weapons against the caro kann vol. 1 & vol. 2.

Vol. 1: Panov and Two Knights

€59.90

Opening Encyclopaedia 2024

Anyone who seriously deals with openings cannot avoid the opening encyclopaedia. Whether beginner or grandmaster. The Opening Encyclopaedia is by far the most comprehensive chess theory work: over 1,463(!) theory articles offer a huge fund of ideas!

€149.90

A Supergrandmaster's Guide to Openings Vol.1: 1.e4

This video course includes GM Anish Giri's deep insights and IM Sagar Shah's pertinent questions to the super GM. In Vol.1 all the openings after 1.e4 are covered.

€49.90

A Supergrandmaster's Guide to Openings Vol.2: 1.d4, 1.c4 and Sidelines

This video course includes GM Anish Giri's deep insights and IM Sagar Shah's pertinent questions to the super GM. While Vol.1 dealt with 1.e4, Vol.2 has all the openings after 1.d4 as well as 1.c4 and sidelines are covered.

A Supergrandmaster's Guide to Openings Vol.1 & 2

€89.90

The Sharp Arkhangelsk Variation in the Ruy Lopez

Great players always have their own successful variations in the opening.

€35.90

ChessBase Magazine Extra 218

Videos: Nico Zwirs on the Vienna Game (1.e4 e5 2.Nc3 Nf6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.d3 c6 5.f4) and part 2 of “Mikhalchishins miniatures”. “Lucky bag” with 53 commented games by Romain Edouard, Michal Krasenkow, Samvel Ter-Sahakyan, Gabriel Sargissian, Nodirbek Yakubboe

€14.90

Master the Kalashnikov Sicilian

Dive into the fascinating world of the Sicilian Kalashnikov variation! We will uncover the secrets of this explosive opening from the very first moves: 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 e5.

€34.90

Najdorf: A dynamic grandmaster repertoire against 1.e4 Vol.1 to 3

In the first part of the video series, we will look at White’s four main moves: 6. Bg5, 6. Be3, 6. Be2 and 6. Bc4.

€99.90

Fritztrainer in App Store

for iPads and iPhones

Pop-up for detailed settings

We use cookies and comparable technologies to provide certain functions, to improve the user experience and to offer interest-oriented content. Depending on their intended use, cookies may be used in addition to technically required cookies, analysis cookies and marketing cookies. You can decide which cookies to use by selecting the appropriate options below. Please note that your selection may affect the functionality of the service. Further information can be found in our privacy policy .

WINTON BRITISH CHESS SOLVING CHAMPIONSHIP

The Winton British Chess Solving Championship (WBCSC)

The Winton British Chess Solving Championship is run annually. Solvers who successfully solve an initial mate in two are sent a second round featuring eight problems of various types. The highest scorers in the second round are invited to the Final, which is held at Eton College in February. The results of the Final play a large part in determining the selection of Great Britain teams for international events. The BCSC began in 1979, sponsored at the time by Lloyds Bank. Since 2004 the event has been sponsored by Winton, which allows the BCPS to pay travelling expenses for finalists. The event forms one leg of the World Solving Cup, and overseas solvers are welcome to compete for WSC points and prize money, though they are not eligible for travelling expenses.

Use the menu above to navigate around the site. About takes you to a potted history of the event and more details about its format. Selecting Current Year ... will produce details and results from the current competition. Select Seeds to see a list of seeded solvers who do not need to enter the Starter Round. Prize-winners will display a list of prize-winners and Archive leads to a list of results from previous years.

Developed and maintained by Brian Stephenson.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Chess: national solving championship open for entries from Britain

Entry is free, the prize fund is expected to be at least £1,200, and the winner qualifies for the 2023 world solving championship

This week’s puzzle is the opening round of a national contest where Guardian readers traditionally perform strongly and in numbers. You have to work out how White, playing as usual up the board, can force checkmate in two moves, however Black defends.

The puzzle is the first stage of the annual Winton British Solving Championship, organised by the British Chess Problem Society. The competition is open to British residents only and entry is free. Its prize fund is expected to be at least £1,200, plus awards to juniors.

To take part, simply send White’s first move to Nigel Dennis, Boundary House, 230 Greys Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1QY. The email route is [email protected] . Please include your name, home address and postcode and mark your entry “Guardian”. If you were under 18 on 31 August 2021, please give your date of birth.

The closing date is 31 July. After that all solvers will receive the answer. Those who get it right will also be sent a postal round of eight problems, with plenty of time for solving. The best 20-25 entries from the postal round, plus the best juniors, will be invited to the final in February 2023 (subject to any Covid‑19 restrictions).

The champion will qualify for the Great Britain team in the 2023 world solving championship, an event where GB is often a medal contender. The starter problem is tricky, though less so than two years ago when a hidden variation which involved queen’s side castling even defeated some computers. Obvious moves rarely work. It is easy to make an error, so review your answer before sending it. Good luck to all Guardian entrants.

China’s world No 2, Ding Liren, the pre-tournament favourite for the world championship Candidates in Madrid, suffered a disastrous start in Friday’s opening round when he was outclassed by Ian Nepomniachtchi , who six months ago had failed to win a single game in his 4-0 world title defeat by Magnus Carlsen.

Ding’s over-complex strategic play with the white pieces was brutally refuted by Russia’s Nepomniachtchi, who played under a neutral Fide flag. The Muscovite massed his black army against the white king, and his pawn advance g7-g5! led to a rapid breakthrough. Ding resigned in the face of a forced checkmate.

The only other decisive game in the opening round was the all-American clash. Fabiano Caruana, the 2018 world title challenger, defeated the five-time US champion Hikaru Nakamura by using his more active pieces to create defensive weaknesses which opened up the streamer’s king.

Round-one results: Jan-Krzysztof Duda (Poland) 0.5 Richard Rapport (Hungary), Ding Liren (China) 0-1 Ian Nepomniachtchi (Fide); Fabiano Caruana (US) 1-0 Hikaru Nakamura (US); Teimour Radjabov (Azerbaijan) 0.5 Alireza Firouzja (France).

There are still 13 rounds to go, but the standout round-two pairing on Saturday is Nepomniachtchi v Caruana. The impressive start by both grandmasters already gives this matchup between Carlsen’s 2021 and 2018 challengers the potential to be a first prize decider.

Play is at the Palacio de Santona in the centre of Madrid. Rounds start at 2pm BST and last approximately five or six hours. The games are free and live to watch online, with move by move grandmaster commentaries and a handy sidebar which enables non-players to see at a glance who is winning, Your favourite major chess site is likely to screen the games live. Chess24 will have the all-time No 1 woman, Judit Polgar, as its main commentator.

There is no English competitor to follow at Madrid but on Monday England teams will be the top seeds in both the World Senior over-50 and over-65 championships at Acqui Terme, Italy.

England over-50s field GMs Michael Adams, Nigel Short, John Emms, Mark Hebden and Keith Arkell. It is the first time that Adams, now 51, has been eligible. Much depends on whether he and Short can recapture some of their golden form of 1993 and 2004 when they were world championship finalists, and whether the squad can avoid any mishaps which could give a rival an advantage in match points.

The United States team are second seeds with a team consisting mainly of ex-Russians who learnt their skills in the former Soviet Union. Georgia, the No 3 seeds, will include the legendary former world women’s champion Nona Gaprindashvili, now aged 81. GM John Nunn leads England over-65s, supported by Paul Littlewood, Nigel Povah, Tony Stebbings and Ian Snape.

- Leonard Barden on chess

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

21 May 2023 | 2 min read

2023 British Chess Solving Championship

Congratulations to David Hodge who is the new Winton British Chess Solving Champion. The event, which Winton has proudly sponsored since 2003, sees competitors solve chess problems against the clock. Professor Metsel finished in second place and third place was taken by junior solver Kamila Hryshchenko. All three will be part of the British team competing at the European Chess Solving Championship in Bratislava this June.

Related News

Winton british chess solving championship.

Congratulations to David Hodge who won the 2024 Winton British Chess Solving Championship.

Winton Prizes for Excellence in Statistics

Congratulations to the winners of the prizes awarded by the LSE Department of Statistics.

Winton Imperial College student prizes

Winton is sponsoring 10 student prizes at Imperial College London this academic year.

FN100 Women in Finance 2023

Winton's Brigid Rentoul maintained her position on this prestigious annual shortlist.

- Leaderboard

ChessPuzzle.net: Improve your chess by solving chess puzzles

"chess is 99% tactics" - richard teichmann.

Tactics are the most important aspect of the game for chess players of all levels, from beginner to grandmaster.

On ChessPuzzle.net you can learn, train, and improve your tactical skills based on positions that happened in real tournament games.

6th December 2023: ChessPuzzle.net Version 3 is here

Starting with the most popular puzzles - checkmates.

Read the blog post

Daily Puzzle

Solve today's daily puzzle

More daily puzzles

Add the daily puzzle to your own website

Select from six modes of play:

Master Chess Tactics with Puzzle Academy

- Your personalized learning solution

- Systematically learn key tactical motifs and master them through personalized workout sessions.

- Tracks your progress and adapts to your strengths and weaknesses

- Progress through an adaptable skill tree with 8 courses and over 200,000 puzzles

- Experience a comprehensive curriculum, from fundamentals to advanced tactics and endgames

- Master complex and beautiful combinations with multiple tactical motifs

- Learn spectacular checkmate combinations by combining tactical motifs and checkmate patterns

Get ready for real games with Puzzle Inception

- Train your tactical alertness and positional evaluation

- Learn when to look for tactics in real game situations

- Evaluate positions without knowing if there's a tactic

- Improve your in-game decision-making skills

Customize Your Training with Puzzle Filter

- Select the difficulty

- Master specific motifs like knight forks

- Practice checkmate patterns, such as smothered mate

- Explore tactics from your favorite openings

- Unlock countless possibilities for personalized training

Boost your concentration with Puzzle Climb

- Test your tactical abilities

- Sharpen your focus

- Master challenging puzzles

- Climb the leaderboard

Puzzle Practice

- Sharpen your vision and calculation abilities

- Receive a rating to monitor your progress

- Puzzles tailored to your skill level

- Enjoy beautiful chess puzzles

Checkmate Armageddon

- Practice checkmate patterns

- Fast-paced gameplay: High stakes action with every move

- Beginners and experts alike can enjoy this adrenaline-pumping game mode

- Unleash your inner chess hero and save the world from Armageddon

New feature: Endgame training

With Puzzle Academy, you can now practice endgames with a large number of examples, honing your endgame skills until they become second nature. This is much more effective than just reading about endgames in a book and hoping to remember the key concepts in the heat of a game.

0

Warning: Your browser is out of date and unsupported. Please update your browser.

Australian Chess Problem Composition

Welcome to OzProblems.com, a site all about chess problems in Australia and around the world! Whether you are new to chess compositions or an experienced solver, we have something for you. Our aim is to promote the enjoyment of chess problems, which are at once interesting puzzles and the most artistic form of chess.

Problem of the Week

698. Ado Kraemer & Erich Zepler Neue Leipziger Zeitung 1931, 1st-2nd Prize =

Problem World

An in-depth introduction to the art of chess composition, examining various problem types and themes.

What is a Chess Problem?

Glossary of Chess Problem Terms .

Weekly Problems

The weekly problem’s solution will appear on the following Saturday, when a new work is quoted.

See last week's problem with solution: No.697 .

Australian Problemists

Prominent Australian problemists write about their involvement in the contemporary problem scene, and present some of their best compositions.

Oz Archives

A comprehensive collection of Australian chess problem materials, including e-books, articles, magazines and columns (all free downloads).

A chess problem blog by Peter Wong, covering a range of subjects. The main page provides a topic index.

See latest post below, followed by links to other recent entries.

Use the contact form on the About page to:

Comment on a Weekly Problem you have solved.

Subscribe to OzProblems updates.

Ask about any aspect of chess problems.

Capture-free proof games

10 Mar . 202 4

In proof game problems , the objective is to find the precise sequence of moves to reach the diagram position, starting from the standard array. Because the problem position comes about directly from the full assembly of 32 pieces, the principle about economy of force in compositions doesn’t necessarily hold and the rule can even be turned on its head. In contrast to “massacre” proof games – a sub-type where the diagram positions are super-economical in terms of the number of pieces – proof game positions with most or all of the 32 units present may be viewed as more pristine or neat, exhibiting “economy of captures.” Totally capture-free play thus becomes a positive feature, or a challenging restriction, with which to accomplish a problem’s principal theme, whatever that might be.

Continue to blog

Help retractors

2 Feb . 202 4

The Holst promotion theme

17 Dec . 2023

Chess diagram change on OzProblems

2 Nov . 2023

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sensors (Basel)

Dynamics of the Prefrontal Cortex during Chess-Based Problem-Solving Tasks in Competition-Experienced Chess Players: An fNIR Study

Telmo pereira.

1 Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra, Coimbra Health School, 3046-854 Coimbra, Portugal; tp.arbmiocsetse@omlet (T.P.); tp.arbmiocsetse@cam (M.A.C.); tp.arbmiocsetse@sca (A.C.S.)

Maria António Castro

2 Centre for Mechanical and Engineering Materials and Processes, University of Coimbra, 3030-788 Coimbra, Portugal

Santos Villafaina

3 Faculty of Sport Science, University of Extremadura. Avda: Universidad S/N, 10003 Cáceres, Spain; se.xenu@tneufpj

António Carvalho Santos

Juan pedro fuentes-garcía.

This study aimed to compare the dynamics of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), between adult and adolescent chess players, during chess-based problem-solving tasks of increasing level of difficulty, relying on the identification of changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2) and hemoglobin (HHb) through the functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) method. Thirty male federated chess players (mean age: 24.15 ± 12.84 years), divided into adults and adolescents, participated in this cross-sectional study. Participants were asked to solve three chess problems with different difficulties (low, medium, and high) while changes in HbO2 and HHb were measured over the PFC in real-time with an fNIRS system. Results indicated that the left prefrontal cortex (L-PFC) increased its activation with the difficulty of the task in both adolescents and adults. Interestingly, differences in the PFC dynamics but not in the overall performance were found between adults and adolescents. Our findings contributed to a better understanding of the PFC resources mobilized during complex tasks in both adults and adolescents.

1. Introduction

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) has been thoroughly described as the center of cognitive function, being involved in executive functions that include decision-making and problem-solving, also taking part in attention, memory, planning, motor control, and cognitive flexibility [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. The PFC, also called the frontal associative cortex and the Magister of the mind [ 4 ], is heavily interconnected with other brain regions, receiving quite diverse sensory and cognitive inputs based on which overall coordination of behavior is implemented. Thus, this brain region, particularly the dorsolateral part, is responsible for the temporal organization of behavior, language, and reasoning [ 5 ], and the definition and coordination of plans for action [ 6 ] entailing its conceptualization and flexibility to the environmental demands [ 7 ]. Furthermore, emotional and inhibitory control processes have been associated with the orbitofrontal region of the PFC, while the medial region has implications in motivation and behavioral drive [ 5 ].

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of the frontal lobe, and particularly the PFC, in problem-solving tasks [ 8 , 9 ] including playing chess games [ 10 ]. Playing Chess is a particular and challenging activity that requires the orchestration of diverse cognitive resources such as memory, attention, and perceptual grouping [ 11 ]. It also involves the recognition of complex spatial relationships as determined by the game rules, and thus, the need to simultaneously handle multiple objects under such rule constraints [ 12 ]. In addition, motor timing, movement selection, and gait control are also enrolled in the multi-componential processes involved in chess-playing, all facets under PFC control [ 13 ]. Other studies have looked into the overall pattern of brain activation as a function of the level of expertise, identifying differences in the cortical resources engaged during chess-playing activities, with the experts manifesting significant activation of areas related to object perception or expertise-related pattern recognition [ 14 , 15 ], as well as recruitment in brain areas involved in knowledge storage and retrieval and memory, whilst the novice players activate predominantly brain areas involved in learning and retrieving of new information [ 10 ]. Higher activation of brain regions involved in attention and problem-solving was also demonstrated in expert chess players engaging a chess-based problem-solving task [ 16 ], highlighting the existence of significant differences in brain dynamics, and underlying cognitive operations in chess players.

The PFC is also of great interest in adolescence due to its relation to cognitive control and emotion processing [ 17 ]. Differences between adult and adolescence PFC have been reported, identifying a reduction in the gray matter between adolescence and adulthood [ 18 ]. This indicates that during adolescence, the prefrontal regions are still developing [ 19 ]. In this regard, the lateral regions of the PFC are the latest developing areas involved in executive regions [ 20 ]. A recent study examined the brain electrical pattern of adolescent chess players during problem-solving tasks [ 21 ]. However, this study did not compare the brain processing of adolescent and adult chess players.

Much of the available evidence concerning brain activation during chess playing tasks have been based on fMRI and electrophysiological methods, but to the best of our knowledge, no studies have previously addressed the PFC activation associated with chess playing tasks with a functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) method. This method provides information on hemodynamic changes associated with cortical activation by noninvasively measuring changes in the relative ratios of deoxygenated hemoglobin (HHb) and oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2) [ 22 ]. Comparatively to other non-invasive neuroimaging methodologies, fNIR is more tolerant to motion artifacts and provides a balance between spatial and temporal resolution, thus being a good method for tasks involving motor components [ 23 , 24 ].

Previous studies have compared the dynamics of the PFC between adults and adolescents using emotional tasks [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]. However, to the best of our knowledge, these comparisons have not been performed using high cognitive demand tasks such as chess. This would be relevant as it would allow reporting whether the differences in the PFC between adolescents and adults [ 18 ] have any impact on the dynamics of the PFC or in the task performance during high demand cognitive tasks. Hence, we sought to compare the dynamics of the PFC activation during three chess-based problem-solving tasks of increasing level of difficulty in both competitive adult and adolescent chess players, relying on the identification of changes in HbO2 and HHb. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experimental approach of the PFC activation in such particular challenging chess tasks monitored with fNIR, and, therefore, the results could contribute to a better understanding of the PFC resources mobilized during the handling of complex problems associated with chess playing in both adults and adolescents.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. study design and participants.

Federated players from official Portuguese chess clubs were invited to participate in a cross-sectional study. The playing level for chess was determined by the ELO rating system, developed by Arpad Elo and introduced by the World Chess Federation (FIDE) as a ranking system [ 28 ]. It is a method for calculating the relative skill levels of players in competitor-versus-competitor games [ 29 ]. All the participants were classified according to the ranking system of the FIDE. Exclusion criteria included (1) inability to perform the tasks with the computer, (2) diseases that affect the autonomic and central nervous system, (3) not being on medication, and (4) not being classified by the International Chess Federation with ELO. A total of 31 players was selected to participate (30 males; 1 female) and screened for suitability based on clinical history, behavioral profile, and chess practice characterization. The female player was excluded to avoid gender bias. All the remaining volunteers met the research requirements and were included in the study, thus, a total of 30 male chess players (24.15 ± 12.84 years) were enrolled, with more than 4 years of continuous competitive chess playing experience (participation in chess competition on average: 10.79 ± 7.73 years). Half of the study population were adults (age > 19 years) and half were adolescents. The participants all had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. After a detailed description of the objective and research methodology, all participants signed an informed consent. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Anonymity and confidentiality of the collected data were assured, and the study was developed for scientific purposes only, free of any financial or economic interests. All procedures were approved by the University Research Ethics committee (approval number: 85/2015).

2.2. Procedure

Data collection was made in an appropriate room, with adequate temperature and humidity, in a dimmed environment where light would not contaminate the collected information, and silent, so the participant’s concentration was not disturbed during the tests. Before the tests, a structured questionnaire was filled with sociodemographic information and details regarding the chess playing history, including years of practice, years of competitive playing, hours of practice per day and days of practice per week, and habit of playing in digital chess platforms and solving problems. The individual ELO score was calculated [ 28 , 29 ]. The participants were questioned about their baseline level of motivation towards the task and the degree of tiredness, providing such information on a 10-point scale.

The participants were then instructed on how to perform the tasks and all the requirements to ensure the quality of the physiological information and the ecological approach of the chess-based problem-solving tasks. The participants were seated in a comfortable chair in front of a computer screen that ran the chess problems and were monitored with a 16-channel fNIRS stand-alone functional brain imaging system (fNIR100A-2, Biopac System Inc., CA, USA), adjusted on the forehead and insulated using a dark light-proof tape. The fNIRS acquisition was performed with a dedicated computer running the COBI Studio program [ 30 ]. Real-time monitoring of HbO2 and HHb in the prefrontal cortex were performed while the participant solved each one of the three chess problems randomly presented. After each problem-solving task, the participants were inquired how they perceived the task in terms of complexity, difficulty, and level of engagement stress.

2.3. Chess Problems

Before starting the experimental task, procedures and protocol requirements were explained to the participants. Moreover, all participants underwent a familiarization period with the computer and the equipment required for testing. Participants conducted a total of three chess-based problem-solving tasks. The problem-solving tasks were selected from Total Chess Training CT-ART 3.0 (Convekta, Moscow, Russia) by a FIDE master (ELO rating of 2300 or more). These chess problems consisted of three levels of difficulty intended for chess players with an ELO rating of 1600–2400 raised by Blokh [ 31 ], with 1 being the lowest and 10 the highest level of difficulty: low-level (1), medium-level (5), and high-level (10) chess problems. Participants had two and a half minutes to solve each problem. Two moves for each problem were required (see Figure 1 ).

Representation of the three chess-based problem-solving tasks by level of complexity: ( a ) panel—low level problem (L); ( b ) panel—medium level problem (M); ( c ) panel—high level problem (H).

The Fritz 15 software, using Stockfish 6, 64 BIT, for Windows was used as chess engine [ 32 ]. It is one of the strongest chess engines in the world and it is open source (GPL license). In addition, chess engines are a useful tool for chess training, being similar to the tactical responses given by humans [ 33 ]. A laptop was employed (Intel Core i7-6500U, (Intel, Santa Clara, USA) 1 TB, 8 GB memory DDR3L-SDRAM, (Dell, Round Rock, USA)). In order to simulate a real chess environment, the Fritz software automatically responded to moves with the best move previously computed by the research group, simulating a real chess environment. The research technician selected the Fritz level according to the ELO level of each player. This methodology was used in previous studies [ 34 , 35 , 36 ].

2.4. Functional Brain Imaging—fNIRS

The measurement of prefrontal cortex activity was performed with an fNIRS system (fNIR100A-2, Biopac System Inc., CA, USA), as previously stated, which detects changes in HbO2 and HHb (both in μmol/L) resulting from brain activation [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. Signal acquisition was performed using a sensor pad containing 4 light sources (LED) and 10 light detectors with a fixed source-detector distance of 2.5 cm and a depth of light penetration of approximately 1.5 cm beneath the scalp, generating an array of 16 measurement sites (voxels or channels) per wavelength [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. The sensor array is embedded in a flexible pad and is placed over the forehead during signal acquisition. The light sources emit two infrared light wavelengths (730 nm and 850 nm) for every 16 channels. As the light penetrates the scalp, part of it is absorbed by the hemoglobin and the remaining light reaches the detectors in a banana-shaped path. Thus, concentrations of hemoglobin are calculated by the ratio of light absorbed at different wavelengths, considering that HbO2 and HHb have different absorption coefficients. The sampling rate of the system was 2 Hz and LED current and detector gain was adjusted prior to the acquisition to prevent signal saturation. The fNIRS acquisition was made for each problem-solving task, resulting in one signal file for each problem. The acquisition started with an initial 10-s baseline recording, after which the task was initiated, and was managed with a dedicated laptop running the Cognitive Optical Brain Imaging (COBI) Studio program [ 23 ] (Biopac system Inc., CA, USA). Figure 2 represents an example of the mean changes in HbO2 and HHb recorded for one participant during the time course of the three experimental tasks.

Example of the relative changes in oxygenated hemoglobin and deoxygenated hemoglobin in one participant during the three experimental tasks. Bin 0 marks the baseline and Bin 11 the end of each task. The relative changes were computed as the mean change in the overall optodes. ( a ) panel—low level problem (L); ( b ) panel—medium level problem (M); ( c ) panel—high level problem (H).

2.5. Data Processing

After visual inspection and elimination of low-quality channels and motion artifacts, the raw files were filtered with a 20-order low-pass finite impulse response (FIR) filter (0.02–0.40 Hz) and a cutoff frequency set at 0.1 Hz to remove long-term drift [ 30 ], high-frequency noise, and cardiac and respiratory cycle effects [ 23 , 24 ]. After this process, a sliding-window motion artifact rejection algorithm was used to filter out spikes and to improve signal quality [ 23 ]. Relative changes in the concentration of HbO2 (ΔHbO2) and HHb (ΔHHb) were calculated based on the modified Beer–Lambert law [ 23 , 24 , 37 ], with a 10-s baseline recorded at the beginning of each task. Blood oxygenation (Δoxy) was calculated as the difference of ΔHbO2–ΔHHb. Blood volume changes (ΔHbT) were calculated as ΔHbO2 + ΔHHb.

All aspects of data processing were managed with the fNIR software [ 23 , 24 , 30 ], version 4.5 (Biopac system Inc., USA). The absolute values obtained after data processing were Z-scored and outliers were removed [ 37 ]. Data per channel was averaged for each condition and four regions of interest (ROI) for the prefrontal cortex were created, as previously proposed [ 13 ], by grouping anatomically congruent channels. The generated ROIs were the left prefrontal cortex (L-PFC), the right prefrontal cortex (R-PFC), the left medial prefrontal cortex (LM-PFC), and the right medial prefrontal cortex (RM-PFC). For studying laterality effects, we further considered the mean left hemisphere prefrontal cortex (LH-PFC) and the mean right hemisphere prefrontal cortex (RH-PFC) by grouping channels accordingly.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data was gathered in Excel 2016 (Microsoft Office, Redmond, WA, USA), and then imported to SPSS Statistics version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) for statistical analysis.

Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, and χ 2 or Fisher exact tests were used when appropriate. The Shapiro–Wilks test was used to confirm the normal distribution of all continuous variables, expressed as mean and standard deviation. As stated before, the fNIRS variables were Z-scored. Other continuous variables with a non-normal distribution were log-transformed. Student’s t -test was applied for group comparisons of descriptive variables only. Individual variables were checked for homogeneity of variance via Levene’s test. A repeated-measures ANOVA was used to evaluate modifications of the variables between the three problem-solving tasks, in the whole population, in each, and between groups. Factors included in the ANOVA were task (three increasing levels of difficulty) and ROI (four prefrontal cortex locations, as described previously). Group was also entered (two levels: adults and adolescents) to test for interactions. The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used when sphericity was violated, and the Bonferroni adjustment was adopted for multiple comparisons designed to locate the significant effects of a factor. A correlational analysis, using Pearson correlation coefficient, was performed to test for age or years of practice effects on the fNIRS parameters. Significant correlations would be included as covariates in an ANCOVA analysis for the functional biomarkers. A two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered significant. The magnitude of the effects was also checked with the η p 2 value.

The main characterization of the study population is summarized in Table 1 . The 30 male chess players enrolled in the study and had a mean age of 24.15 ± 12.84 years, ranging from 13 to 55 years. All participants were clinically healthy, with three participants reporting the use of medication (mainly anti-histaminic drugs). Mean chess practice was 14.00 ± 10.30 years (range: 6–43 years) and mean chess competition participation time was 10.92 ± 7.85 years (range: 4–40 years). The mean ELO was 1677 ± 332, and all participants referred to regular chess practicing habits as depicted in Table 1 . The majority of the participants attributed the beginning of their chess playing either to school activities (46.7%) or family influence (36.6%). The population was divided according to age into a group of adults (age above 19 years) and adolescents (age between 13 and 19 years). As expected, the adults had a significantly longer chess playing background, although no significant differences were observed concerning chess practicing habits. Similar patterns of playing with digital chess platforms and problem-solving training routines were observed in adults and adolescents.

Characterization of the participants according to age, chess practicing habits, and individual ELO.

Regarding the initial levels of motivation towards the tasks of the study, a mean score of 7.67 ± 2.26 was obtained for the entire population, with similar results in the adults (mean score: 7.80 ± 2.54) and the adolescents (mean score: 7.53 ± 2.03; p = 0.753). The degree of initial tiredness showed a similar trend, with a mean initial score of 2.30 ± 2.07 in the whole population, and no differences comparing adults and adolescents ( p = 0.467).

The majority of the players ( n = 22; 73.3%) were able to solve the low difficulty problem, independently of their age (adults: n = 12; adolescents: n = 10; p = 0.409). Regarding the medium difficulty problem, half of the participants were able to solve them, with no significant differences between the adults and the adolescents ( p = 0.715). None of the participants were able to find the solution for the high difficulty problem.

Table 2 summarizes the main findings for the functional biomarkers in the whole study population. An overall increase in PFC oxygenation with task difficulty was observed, with a mean Δoxy of 0.78 ± 0.21 μmol/L in the low difficulty task, increasing to 0.91 ± 0.26 μmol/L in the medium difficulty task and 0.98 ± 0.25 μmol/L in the high difficulty task (F = 8.782; p < 0.001; η p 2 = 0.232). Considering the four defined ROIs, significant changes in all four biomarkers were observed only over the L-PFC, showing an increase in ∆HbO2, Δoxy, and ΔHbT with increasing task complexity. These changes were followed by a significant decrease in ∆HHb, indicating a higher activation in the L-PFC as a function of the difficulty of the problem-solving tasks. The aforementioned results explain the significant changes observed when comparing hemispheric contributions according to the task difficulty, with significant changes observed for the left hemisphere region of the PFC (L-PFC and LM-PFC; Δoxy F = 10.896; p < 0.001; η p 2 = 0.273) but not for the right hemisphere region (R-PFC and RM-PFC; Δoxy F = 1.637; p = 0.203; η p 2 = 0.053).

Prefrontal cortex dynamics according to the variation of the functional biomarkers in the three problem-solving chess tasks.

∆HbO2—variation in oxyhemoglobin; ∆HHb—variation in deoxyhemoglobin; ∆HbT—variation in total hemoglobin; ∆oxy—difference between oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin; L-PFC—left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; R-PFC—right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; LM-PFC—left medial prefrontal cortex; RM-PFC—right medial prefrontal cortex.

Considering the main findings for the functional biomarkers in the adolescents and the adults, different patterns of oxygenation were depicted as demonstrated in Figure 3 . A significant Task difficulty*ROI*Group interaction was observed regarding the ∆HbO2 (F interaction = 2.580; p = 0.020; η p 2 = 0.084) and the ∆oxy (F interaction = 2.345; p = 0.034; η p 2 = 0.077), but not for the ∆HHb and the ∆HbT. In both groups, significant changes were observed in the L-PFC, with an increase in ∆HbO2, Δoxy, and ΔHbT and a decrease in ∆HHb with increasing task complexity. A significant effect was also observed for the ∆HbO2 in the medium level chess problem, with the adolescents presenting significant greater relative change over the R-PFC when compared with the adults ( F = 4.808; p = 0.004; η p 2 = 0.147). No significant changes were observed in the low-level chess problem, but differences emerged with increasing complexity of the task, mainly located in the R-PFC and the dorsolateral regions (both LM- and RM-PFC) for the medium level chess problem, and in the L-PFC for the high-level chess problem. In the medium level chess problem, the adolescents presented higher relative changes in Δoxy over the R-PFC and smaller relative changes in Δoxy over the dorsolateral regions of the PFC. In the higher complexity task, the L-PFC responded more in the adults, leading to greater relative change in the Δoxy as compared with the adolescents. No significant differences were observed between groups in what concerns the overall PFC oxygenation levels in the three experimental conditions. To test for age or years of practice effects, we performed a correlational analysis of the fNIRS parameters and these two covariates. A significant (weak to moderate) correlation was found only between age and the LM-PFC changes in HbO2 ( r = 0.371; p = 0.044), HHb ( r = −0.378; p = 0.039), and Oxy ( r = 0.449; p = 0.013). Consequently, we performed an ANCOVA analysis for the functional biomarkers, with age as covariate, and no substantive changes were observed in the factorial results regarding the ∆HbO2 (F interaction = 2.286; p = 0.038; η p 2 = 0.078) and the ∆oxy (F interaction = 3.421; p = 0.003; η p 2 = 0.112), although a significant task difficulty*ROI*Group interaction was depicted for the ∆HHb (F interaction = 2.590; p = 0.020; η p 2 = 0.088) when age was included as covariate in the model.

Relative changes in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HHb) in the adolescents group (( a ) panel) and in the adults group (( b ) panel), according to the level of difficulty of the chess-based problem-solving tasks. L-PFC—left prefrontal cortex; R-PFC—right prefrontal cortex; LM-PFC—left medial prefrontal cortex; RM-PFC—right medial prefrontal cortex.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the dynamics of the PFC activation during three chess-based problem-solving tasks of increasing level of difficulty in competitive adult and adolescent chess players. Several main findings emerged. First, the activation of the PFC, measured by fNIR spectroscopy, was increased with more demanding chess problems in both adolescent and adult chess players. Second, differences in the patterns of PFC activation were found between adult and adolescent chess players. Adult chess players showed greater relative changes in blood oxygenation over the dorsolateral regions of the PFC and greater activation of the L-PFC during the high difficulty problem, whereas the adolescent chess players showed a greater relative change in the ∆oxy in the R-PFC in the medium level task. However, an alternative explanation could emerge. In this regard, since the performance is the same in the two groups, it could be that younger participants exhibited lower mental effort in the high level condition. Moreover, adults could be more engaged in the high level problem-solving task than young chess players (less motivated than adult chess players). In this line, a lower PFC activation when an individual drops the task has been found in fNIRs studies [ 38 , 39 ].

Considering the factorial profiles of changes in oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin, a more efficient management of cognitive resources is apparent in adult chess players, regardless of the overall level of PFC activation. Interestingly, these differences in PFC activation had no consequences in the overall performance. These results have a significant relevance in the field of chess since fNIR spectroscopy could be used to determine the cognitive load of a task as well as to test if a training could change the efficiency of the PFC. In addition, future studies should use this technology in older adults or special populations to evaluate the effects of therapies in the PFC activation.

In order to study the PFC activation, we employed fNIR spectroscopy to measure the relative changes in HbO2 and HHb during the chess tasks. Changes in HbO2 have been considered as the most sensitive parameter to measure activity-dependent changes in regional cerebral blood flow [ 40 , 41 , 42 ] and is also particularly sensitive to mental workload variations [ 37 , 42 ]. Our main findings are consistent with the involvement of the PFC during the experimental tasks, increasing its activation following the increase in the complexity of the experimental tasks. Furthermore, the defined ROIs in the PFC showed different contributions as a function of the difficulty of the chess problems, particularly in the L-PFC in which a progressively higher activation was identified through the four considered biomarkers with increasing level of difficulty. The increased activation of the PFC for increasingly more demanding chess problems was observed both in adults and adolescents, although the level of activation in the considered ROIs was different particularly in the medium and high difficulty level. The adult chess players showed greater relative changes in blood oxygenation over the dorsolateral regions of the PFC and greater activation of the L-PFC during the high difficulty problem as compared with the adolescents, which showed a greater relative change in the ∆oxy in the R-PFC in the medium level task. Notwithstanding, these between-group differences in the PFC activation had no consequence in the overall performance during the tasks, since no differences were observed between the groups when comparing the level of success solving either experimental scenario.

The enrollment of the PFC in complex tasks has been widely demonstrated [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 9 ] and was also observed in our study. Furthermore, the dorsolateral region of the PFC has been shown to play a crucial role in the overall coordination of several cognitive resources which are necessary during problem-solving tasks, such as the temporal organization of behavior, language, and reasoning [ 5 ], the definition and coordination of plans for action [ 6 ], and the flexibility to the environmental demands [ 7 ]. This PFC region was mostly active in the chess players during the experimental tasks, and particularly the L-PFC was quite sensitive to changes in the cognitive load as expressed by the difficulty of the problem, with increasing activation following the increase in the complexity of the tasks.

The differences in the patterns of PFC activation in adult and adolescent players could express the interaction of both brain maturation and level of expertise or experience. In fact, previous research identified the recruitment of different psychological functions and the activation of different brain areas or different magnitudes of activation of the same brain areas during chess-related activities in expertise versus novice players [ 10 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. This is in line with our findings which highlight the existence of significant differences in the PFC dynamics during chess-based problem-solving tasks comparing the adult with adolescent chess players. This could confirm that the differences in the PFC detected by previous studies [ 18 ] also affect the functioning of the PFC. Curiously, the different patterns of PFC activation were not followed by differences in terms of the overall performance during the task, and, therefore, the differences in brain dynamics over the PFC could merely translate into greater underlying efficiency in the adult players. This could be connected with the chunking theory and its augmented theory, the template theory [ 43 ]. Chase and Simon [ 44 ] proposed that Masters access information in long-term memory rapidly by recognizing familiar constellations of pieces on the board, the patterns acting as cues that trigger access to the chunks. This could be the reason why cognitive processes are more efficient in adults than in adolescent chess players. However, future studies should investigate this hypothesis.

This study has several limitations that should be considered. The small number of participants is a significant aspect, particularly on the between-group comparison, even though the results were consistent in the most relevant outcomes considered in the study. We did not analyze the temporal changes in PFC oxygenation during the tasks, and, therefore, the time course of hemodynamic changes during the problem-solving tasks was not considered for the analysis. Considering that the fNIRS system used in this research does not integrate short channels-based technology, we cannot exclude the possibility of picking extra-cerebral oxygenation signals. Such limitation could have been obviated through the use of task replications, and, therefore, further studies should include replications in the experimental design. The difference in the ELO score and overall chess experience between groups could also explain some of the observed differences at the group level and should be addressed in future research. Due to the heterogeneity of our sample, future studies should explore the PFC activation during problem-solving tasks in different levels of expertise (novice vs. expert paradigm) in age-matched groups.

5. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study addressing the dynamics of the PFC activation during chess-based problem-solving tasks with fNIR spectroscopy. The PFC dynamics differ in adults and adolescents, corresponding to a more efficient cortical organization in the adult players for the same overall level of performance. Furthermore, we demonstrated the participation of the PFC during complex chess problem tasks, with the L-PFC responding with increasing activation to the increasing level of difficulty of the tasks and corresponding cognitive load in both adults and adolescents.

Our findings contributed to a better understanding of the PFC resources mobilized during the handling of complex problems associated with chess-playing, also adding evidence to the understanding of the neural substrate underlying overall human problem-solving mechanisms. Moreover, revealed differences in the PFC functioning between adults and adolescents during high cognitive demand tasks should be investigated in future studies. Further studies should also include the continuous measurement of fNIRS-based biomarkers to allow for the examination of spontaneous hemodynamic fluctuations (as in Verdière et al.’s [ 45 ] study), as well as the adoption of more sophisticated NIRS technologies, such as high-definition near-infrared spectroscopy or diffuse optical tomography. Studying the functional correlates of unsuccessful moves during chess playing could also add novel insights, and connectivity metrics could also support the study of hemispheric interplay during complex chess problem tasks, contributing to a better understanding of cortical dynamics in chess playing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.P. and S.V.; data curation, T.P., M.A.C., S.V., and A.C.S.; formal analysis, T.P.; funding acquisition, J.P.F.-G.; investigation, T.P., M.A.C., and S.V.; methodology, M.A.C. and S.V.; project administration, J.P.F.-G.; resources, A.C.S. and J.P.F.-G.; software, T.P. and A.C.S.; validation, M.A.C. and J.P.F.-G.; visualization, A.C.S. and J.P.F.-G.; writing—original draft, T.P.; writing—review & editing, M.A.C., S.V., A.C.S., and J.P.F.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This study has been conducted thanks to the contribution of the Ministry of Economy and Infrastructure of the Junta de Extremadura through the European Regional Development Fund. A way to make Europe. (GR18129). Furthermore, S.V. was supported by a grant from the regional department of economy and infrastructure of the Government of Extremadura and the European Social Fund (PD16008) and by a research mobility grant of the AUIP—Asociación Universitaria Iberoamericana de Postgrado. The funders played no role in the study design, the data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

FIDE Candidates 2024: How do you ace the chess marathon?

- Shyam Vasudevan

The FIDE Candidates tournament is a chess marathon: 21 days, 14 matches per player, eight of the world's best chess players and one grand prize. There's only one real objective in this cut-throat competition: finish first.

How do you prepare for a tournament like this, where the margin for error is so slim that one bad move could potentially end your chances of becoming world champion?

The key is to approach it like any other tournament, says coach RB Ramesh, who has two players at the tournament: Rameshbabu Praggnanandhaa and Vaishali.

While it may not appear so, chess is a ridiculously exhausting sport - both mentally and physically. And it gets all the more taxing in a tournament like the Candidates, which is played over three weeks.

During the tournament

Ramesh's advice is simple: eat and sleep well and play plenty of other sports. "It can get very tiring very soon, especially if a player is going through a bad phase; this can be an extremely prolonged agony event. It's very important to start well so that we don't get into that bracket. With positive outcomes, it becomes easier to push forward."

"I've asked both to sleep well so that their body and mind get sufficient rest and also go for long walks or play sports, whatever is available at the venue. In general, to have a healthy routine and stick as close to it as possible."

A routine is also something that five-time world champion Viswanathan Anand swears by. But at the same time, he feels you can offer suggestions on how to stay mentally and physically fresh, but you also need to account for the rigours of the tournament.

"You have suggestions, but each player is also used to their routines. When they follow their routine, their dopamine goes up and you shouldn't tinker too much with that. You'll have to allow it to be dictated by the tournament and the tournament situation. Some days you'll feel disgusted with yourself at the end. You might've spoiled a long game and then coming to you and saying 'Here's how many carbs you should have, how much protein you should have' doesn't make sense," he says.

Preparing in Chennai

In their bid to prepare for the Candidates, players often go into some form of isolation - away from the public glare - to cut out the noise and get into the zone. Ramesh did the same, organizing a camp for Praggnanandhaa and Vaishali away from the city.

The routine was such: eight hours of chess, different sports and physical exercises for 3-4 hours and sleep for 10 hours. Ramesh adds with a laugh that they did not have too many early starts since both of them "like to sleep a lot".

"We have also done some meditation sessions. They've been eating healthy, sleeping well and doing a variety of sports activities like beach volleyball games, badminton, table tennis, swimming and some jogging over the last few months to have a healthy energy reserve to build up competitiveness and some aggression into their mindset."

The sessions are taken seriously - one of those beach volleyball sessions ended with Ramesh's right wrist in a brace.

The people behind the players

Anand is the only Indian to have regularly featured in the Candidates and it's only fitting that he has a role to play this time around as well albeit in a different avatar - as a mentor.

Three of India's five representatives at the Candidates - Praggnanandhaa, Vaishali and D. Gukesh - are backed by the WestBridge Anand Chess Academy (WACA). Along with mentorship sessions from Anand, the players also have access to some of the most decorated names in chess.

For example: Gukesh trains with Polish GM Grzegorz Gajewski, who is renowned for his opening theories. Similarly, Vaishali has GM Sandipan Chanda in her corner, and he specializes in mid-game prep. "Vaishali has been working a lot with GM Sandipan. He has taken the lead in forming a team for her and guiding her preparation," notes Ramesh.

The results are there to see: within the last five months, Vaishali became India's third female Grandmaster, won the FIDE Grand Swiss and qualified for the Candidates.

The players can also pick the brains of endgame expert GM Artur Yusupov and former World Cup winner GM Boris Gelfand. This all-star squad, along with Anand, conducts regular sessions to support the players in all the facets of the sport. What's important here is that WACA "didn't replace or displace any setup" that the players already had, says Anand.

Approaching the actual matches

On the board, the Candidates poses a unique challenge: you have to prepare for seven different opponents. That means you need to work out innumerable scenarios, which is no mean feat.

"We work to identify all the openings that are likely to come. We see where we stand against each of those openings and work on them. It is tough to predict what the opponents will do because they will also be doing the same. They're not going to play what we expect them to play and will be planning their surprises and so on.

"In case I'm going to play against one opponent or in the World Championship match, then it makes more sense to go for a personalized approach. But here, there are still seven other players and hence we go through the openings of each of the players to prepare," says Ramesh.

The pairings are done in such a manner that players from the same country finish their matches early in the tournament so that they don't meet at the business end of the competition. "It's a pity because I think these guys are professionals and none of them is going to help another because of nationality. But you know, there's some old tradition," says Anand.

He adds that it's unusual to see Indians squaring up against each other because "it's only Russians who usually meet quite early. And now we are joining that party. Primarily, we should see them as individuals. Let's not forget, they may have to go against each other very viciously. They have to compete against themselves very viciously as well."

But he adds that there is a sense of comfort in having your compatriots around. "It's this very intangible feeling of seeing familiar faces or knowing that my countrymen are here. There's a slightly warm buzz."

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

44 th World Chess Solving Championship Rhodes, 19-20.11.2021. Main Judge: Luc Palmans Assistant: Paz Einat Problems selected by: Luc Palmans. 16 teams and 65 solvers from 24 countries participated.

The World Chess Solving Championship (WCSC) is an annual competition in the solving of chess problems (also known as chess puzzles) organized by the World Federation for Chess Composition (WFCC), previously by FIDE via the Permanent Commission of the FIDE for Chess Compositions (PCCC).. The participants must solve a series of different types of chess problem in a set amount of time.

2023/06/13 - The 2022-2023 Winton Capital British Chess Solving Championship Written by Brian Stephenson. The Final of the Winton Capital British Chess Solving Championship took place on 20th May 2023 at Nottingham High School. All the problems set, and their solutions, in the Open and Minor events, and the full results can be viewed here

1/26/2023 - As the traditional introduction to a new solving season, the 19th International Solving Contest (ISC) will be held this Sunday, January 29. A set of chess problems will be simultaneously offered to more than 500 solvers around the world at 11 AM CET. The ISC hybrid solving competition is becoming increasingly popular since it ...

The director of the competition, Neal Turner, a long-time Secretary of the WFCC, has been devoted to solving competitions in Finland for decades. The Finish Chess Problem Society (Suomen Tehtäväniekat) was established in 1935. From the 1st World Chess Solving Championship (WCSC) 1977, Finnish solvers were dominating.

Welcome to the ChessBase India Winter Chess Solving Championship, an initiative to promote chess composition and creative-logical thinking through chess. This introductory article serves as the curtain-raiser to the event: Satanick Mukhuty give you the rules, the details of the prizes, and the first six of the twelve problems to solve. This is a serious challenge.

The Winton British Chess Solving Championship (WBCSC) The Winton British Chess Solving Championship is run annually. Solvers who successfully solve an initial mate in two are sent a second round featuring eight problems of various types. The highest scorers in the second round are invited to the Final, which is held at Eton College in February.

The puzzle is the first stage of the annual Winton British Solving Championship, organised by the British Chess Problem Society. The competition is open only to British residents, and entry is ...

Results & Statistics. Finally we had 44 tournaments in 20 countries and 585 solvers (+15 unofficial solvers in cat-3) - 94 solvers in cat-1, 166 solvers in cat-2 and 325 solvers in cat-3. Thank you to all local controller for their excellent work and good cooperation and congratulation to the winners. If you find any mistakes in the tables (e ...

The puzzle is the first stage of the annual Winton British Solving Championship, organised by the British Chess Problem Society. The competition is open only to British residents, and entry is free.

The puzzle is the first stage of the annual Winton British Solving Championship, organised by the British Chess Problem Society. The competition is open to British residents only and entry is free ...

A chess problem, also called a chess composition, is a puzzle set by the composer using chess pieces on a chess board, which presents the solver with a particular task. For instance, a position may be given with the instruction that White is to move first, and checkmate Black in two moves against any possible defence. A chess problem fundamentally differs from over-the-board play in that the ...

2023 British Chess Solving Championship. David Hodge takes gold at the annual Winton-sponsored problem-solving tournament. Congratulations to David Hodge who is the new Winton British Chess Solving Champion. The event, which Winton has proudly sponsored since 2003, sees competitors solve chess problems against the clock.

Master Chess Tactics with Puzzle Academy. Your personalized learning solution. Systematically learn key tactical motifs and master them through personalized workout sessions. Tracks your progress and adapts to your strengths and weaknesses. Progress through an adaptable skill tree with 8 courses and over 200,000 puzzles.

Australian Chess Problem Composition. Welcome to OzProblems.com, a site all about chess problems in Australia and around the world! Whether you are new to chess compositions or an experienced solver, we have something for you. Our aim is to promote the enjoyment of chess problems, which are at once interesting puzzles and the most artistic form ...

European Chess Solving Championship (ECSC) Current Rules. 1 st ECSC Legnica, Poland, June 18 and 19, 2005 Announcement | Results Problems | Solutions | Results Individuals | Results Teams; 2 nd ECSC Warsaw, Poland, 10.-12.11.2006 Problems | Solutions | Results Individuals | Results Teams

These chess problems consisted of three levels of difficulty intended for chess players with an ELO rating of 1600-2400 raised by Blokh , with 1 being the lowest and 10 the highest level of difficulty: low-level (1), medium-level (5), and high-level (10) chess problems. Participants had two and a half minutes to solve each problem.

This year the ISC suffered under the circumstances of the Corona-pandemic. In many countries it was not possible to organize a tournament. But not only the pandemic led to less tournaments and solvers but also very low temperatures in Siberia (-47°C in Nizhnevartovsk) and the consequences of a severe earthquake in Croatia three weeks ago. The ...

The FIDE Candidates tournament is a chess marathon: 21 days, 14 matches per player, eight of the world's best chess players and one grand prize. There's only one real objective in this cut-throat ...