An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Breech presentation.

Caron J. Gray ; Meaghan M. Shanahan .

Affiliations

Last Update: November 6, 2022 .

- Continuing Education Activity

Breech presentation refers to the fetus in the longitudinal lie with the buttocks or lower extremity entering the pelvis first. The three types of breech presentation include frank breech, complete breech, and incomplete breech. In a frank breech, the fetus has flexion of both hips, and the legs are straight with the feet near the fetal face, in a pike position. This activity reviews the cause and pathophysiology of breech presentation and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

- Describe the pathophysiology of breech presentation.

- Review the physical exam of a patient with a breech presentation.

- Summarize the treatment options for breech presentation.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by breech presentation.

- Introduction

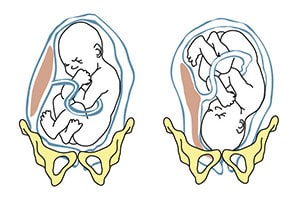

Breech presentation refers to the fetus in the longitudinal lie with the buttocks or lower extremity entering the pelvis first. The three types of breech presentation include frank breech, complete breech, and incomplete breech. In a frank breech, the fetus has flexion of both hips, and the legs are straight with the feet near the fetal face, in a pike position. The complete breech has the fetus sitting with flexion of both hips and both legs in a tuck position. Finally, the incomplete breech can have any combination of one or both hips extended, also known as footling (one leg extended) breech, or double footling breech (both legs extended). [1] [2] [3]

Clinical conditions associated with breech presentation include those that may increase or decrease fetal motility, or affect the vertical polarity of the uterine cavity. Prematurity, multiple gestations, aneuploidies, congenital anomalies, Mullerian anomalies, uterine leiomyoma, and placental polarity as in placenta previa are most commonly associated with a breech presentation. Also, a previous history of breech presentation at term increases the risk of repeat breech presentation at term in subsequent pregnancies. [4] [5] These are discussed in more detail in the pathophysiology section.

- Epidemiology

Breech presentation occurs in 3% to 4% of all term pregnancies. A higher percentage of breech presentations occurs with less advanced gestational age. At 32 weeks, 7% of fetuses are breech, and 28 weeks or less, 25% are breech.

Specifically, following one breech delivery, the recurrence rate for the second pregnancy was nearly 10%, and for a subsequent third pregnancy, it was 27%. Prior cesarean delivery has also been described by some to increase the incidence of breech presentation two-fold.

- Pathophysiology

As mentioned previously, the most common clinical conditions or disease processes that result in the breech presentation are those that affect fetal motility or the vertical polarity of the uterine cavity. [6] [7]

Conditions that change the vertical polarity or the uterine cavity, or affect the ease or ability of the fetus to turn into the vertex presentation in the third trimester include:

- Mullerian anomalies: Septate uterus, bicornuate uterus, and didelphys uterus

- Placentation: Placenta previa as the placenta is occupying the inferior portion of the uterine cavity. Therefore, the presenting part cannot engage

- Uterine leiomyoma: Mainly larger myomas located in the lower uterine segment, often intramural or submucosal, that prevent engagement of the presenting part.

- Prematurity

- Aneuploidies and fetal neuromuscular disorders commonly cause hypotonia of the fetus, inability to move effectively

- Congenital anomalies: Fetal sacrococcygeal teratoma, fetal thyroid goiter

- Polyhydramnios: Fetus is often in unstable lie, unable to engage

- Oligohydramnios: Fetus is unable to turn to vertex due to lack of fluid

- Laxity of the maternal abdominal wall: Uterus falls forward, the fetus is unable to engage in the pelvis.

The risk of cord prolapse varies depending on the type of breech. Incomplete or footling breech carries the highest risk of cord prolapse at 15% to 18%, while complete breech is lower at 4% to 6%, and frank breech is uncommon at 0.5%.

- History and Physical

During the physical exam, using the Leopold maneuvers, palpation of a hard, round, mobile structure at the fundus and the inability to palpate a presenting part in the lower abdomen superior to the pubic bone or the engaged breech in the same area, should raise suspicion of a breech presentation.

During a cervical exam, findings may include the lack of a palpable presenting part, palpation of a lower extremity, usually a foot, or for the engaged breech, palpation of the soft tissue of the fetal buttocks may be noted. If the patient has been laboring, caution is warranted as the soft tissue of the fetal buttocks may be interpreted as caput of the fetal vertex.

Any of these findings should raise suspicion and ultrasound should be performed.

Diagnosis of a breech presentation can be accomplished through abdominal exam using the Leopold maneuvers in combination with the cervical exam. Ultrasound should confirm the diagnosis.

On ultrasound, the fetal lie and presenting part should be visualized and documented. If breech presentation is diagnosed, specific information including the specific type of breech, the degree of flexion of the fetal head, estimated fetal weight, amniotic fluid volume, placental location, and fetal anatomy review (if not already done previously) should be documented.

- Treatment / Management

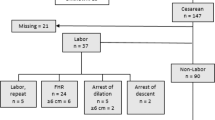

Expertise in the delivery of the vaginal breech baby is becoming less common due to fewer vaginal breech deliveries being offered throughout the United States and in most industrialized countries. The Term Breech Trial (TBT), a well-designed, multicenter, international, randomized controlled trial published in 2000 compared planned vaginal delivery to planned cesarean delivery for the term breech infant. The investigators reported that delivery by planned cesarean resulted in significantly lower perinatal mortality, neonatal mortality, and serious neonatal morbidity. Also, there was no significant difference in maternal morbidity or mortality between the two groups. Since that time, the rate of term breech infants delivered by planned cesarean has increased dramatically. Follow-up studies to the TBT have been published looking at maternal morbidity and outcomes of the children at two years. Although these reports did not show any significant difference in the risk of death and neurodevelopmental, these studies were felt to be underpowered. [8] [9] [10] [11]

Since the TBT, many authors since have argued that there are still some specific situations that vaginal breech delivery is a potential, safe alternative to planned cesarean. Many smaller retrospective studies have reported no difference in neonatal morbidity or mortality using these specific criteria.

The initial criteria used in these reports were similar: gestational age greater than 37 weeks, frank or complete breech presentation, no fetal anomalies on ultrasound examination, adequate maternal pelvis, and estimated fetal weight between 2500 g and 4000 g. In addition, the protocol presented by one report required documentation of fetal head flexion and adequate amniotic fluid volume, defined as a 3-cm vertical pocket. Oxytocin induction or augmentation was not offered, and strict criteria were established for normal labor progress. CT pelvimetry did determine an adequate maternal pelvis.

Despite debate on both sides, the current recommendation for the breech presentation at term includes offering external cephalic version (ECV) to those patients that meet criteria, and for those whom are not candidates or decline external cephalic version, a planned cesarean section for delivery sometime after 39 weeks.

Regarding the premature breech, gestational age will determine the mode of delivery. Before 26 weeks, there is a lack of quality clinical evidence to guide mode of delivery. One large retrospective cohort study recently concluded that from 28 to 31 6/7 weeks, there is a significant decrease in perinatal morbidity and mortality in a planned cesarean delivery versus intended vaginal delivery, while there is no difference in perinatal morbidity and mortality in gestational age 32 to 36 weeks. Of note, due to lack of recruitment, no prospective clinical trials are examining this issue.

- Differential Diagnosis

- Face and brow presentation

- Fetal anomalies

- Fetal death

- Grand multiparity

- Multiple pregnancies

- Oligohydramnios

- Pelvis Anatomy

- Preterm labor

- Primigravida

- Uterine anomalies

- Pearls and Other Issues

In light of the decrease in planned vaginal breech deliveries, thus the decrease in expertise in managing this clinical scenario, it is prudent that policies requiring simulation and instruction in the delivery technique for vaginal breech birth are established to care for the emergency breech vaginal delivery.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A breech delivery is usually managed by an obstetrician, labor and delivery nurse, anesthesiologist and a neonatologist. The ultimate decison rests on the obstetrician. To prevent complications, today cesarean sections are performed and experienced with vaginal deliveries of breech presentation is limited. For healthcare workers including the midwife who has no experience with a breech delivery, it is vital to communicate with an obstetrician, otherwise one risks litigation if complications arise during delivery. [12] [13] [14]

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Caron Gray declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Meaghan Shanahan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Gray CJ, Shanahan MM. Breech Presentation. [Updated 2022 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- [What effect does leg position in breech presentation have on mode of delivery and early neonatal morbidity?]. [Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 1997] [What effect does leg position in breech presentation have on mode of delivery and early neonatal morbidity?]. Krause M, Fischer T, Feige A. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 1997 Jul-Aug; 201(4):128-35.

- The effect of intra-uterine breech position on postnatal motor functions of the lower limbs. [Early Hum Dev. 1993] The effect of intra-uterine breech position on postnatal motor functions of the lower limbs. Sival DA, Prechtl HF, Sonder GH, Touwen BC. Early Hum Dev. 1993 Mar; 32(2-3):161-76.

- The influence of the fetal leg position on the outcome in vaginally intended deliveries out of breech presentation at term - A FRABAT prospective cohort study. [PLoS One. 2019] The influence of the fetal leg position on the outcome in vaginally intended deliveries out of breech presentation at term - A FRABAT prospective cohort study. Jennewein L, Allert R, Möllmann CJ, Paul B, Kielland-Kaisen U, Raimann FJ, Brüggmann D, Louwen F. PLoS One. 2019; 14(12):e0225546. Epub 2019 Dec 2.

- Review Breech vaginal delivery at or near term. [Semin Perinatol. 2003] Review Breech vaginal delivery at or near term. Tunde-Byass MO, Hannah ME. Semin Perinatol. 2003 Feb; 27(1):34-45.

- Review [Breech Presentation: CNGOF Guidelines for Clinical Practice - Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Complications]. [Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2...] Review [Breech Presentation: CNGOF Guidelines for Clinical Practice - Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Complications]. Mattuizzi A. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2020 Jan; 48(1):70-80. Epub 2019 Nov 1.

Recent Activity

- Breech Presentation - StatPearls Breech Presentation - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Pregnancy Classes

Breech Births

In the last weeks of pregnancy, a baby usually moves so his or her head is positioned to come out of the vagina first during birth. This is called a vertex presentation. A breech presentation occurs when the baby’s buttocks, feet, or both are positioned to come out first during birth. This happens in 3–4% of full-term births.

What are the different types of breech birth presentations?

- Complete breech: Here, the buttocks are pointing downward with the legs folded at the knees and feet near the buttocks.

- Frank breech: In this position, the baby’s buttocks are aimed at the birth canal with its legs sticking straight up in front of his or her body and the feet near the head.

- Footling breech: In this position, one or both of the baby’s feet point downward and will deliver before the rest of the body.

What causes a breech presentation?

The causes of breech presentations are not fully understood. However, the data show that breech birth is more common when:

- You have been pregnant before

- In pregnancies of multiples

- When there is a history of premature delivery

- When the uterus has too much or too little amniotic fluid

- When there is an abnormally shaped uterus or a uterus with abnormal growths, such as fibroids

- The placenta covers all or part of the opening of the uterus placenta previa

How is a breech presentation diagnosed?

A few weeks prior to the due date, the health care provider will place her hands on the mother’s lower abdomen to locate the baby’s head, back, and buttocks. If it appears that the baby might be in a breech position, they can use ultrasound or pelvic exam to confirm the position. Special x-rays can also be used to determine the baby’s position and the size of the pelvis to determine if a vaginal delivery of a breech baby can be safely attempted.

Can a breech presentation mean something is wrong?

Even though most breech babies are born healthy, there is a slightly elevated risk for certain problems. Birth defects are slightly more common in breech babies and the defect might be the reason that the baby failed to move into the right position prior to delivery.

Can a breech presentation be changed?

It is preferable to try to turn a breech baby between the 32nd and 37th weeks of pregnancy . The methods of turning a baby will vary and the success rate for each method can also vary. It is best to discuss the options with the health care provider to see which method she recommends.

Medical Techniques

External Cephalic Version (EVC) is a non-surgical technique to move the baby in the uterus. In this procedure, a medication is given to help relax the uterus. There might also be the use of an ultrasound to determine the position of the baby, the location of the placenta and the amount of amniotic fluid in the uterus.

Gentle pushing on the lower abdomen can turn the baby into the head-down position. Throughout the external version the baby’s heartbeat will be closely monitored so that if a problem develops, the health care provider will immediately stop the procedure. ECV usually is done near a delivery room so if a problem occurs, a cesarean delivery can be performed quickly. The external version has a high success rate and can be considered if you have had a previous cesarean delivery.

ECV will not be tried if:

- You are carrying more than one fetus

- There are concerns about the health of the fetus

- You have certain abnormalities of the reproductive system

- The placenta is in the wrong place

- The placenta has come away from the wall of the uterus ( placental abruption )

Complications of EVC include:

- Prelabor rupture of membranes

- Changes in the fetus’s heart rate

- Placental abruption

- Preterm labor

Vaginal delivery versus cesarean for breech birth?

Most health care providers do not believe in attempting a vaginal delivery for a breech position. However, some will delay making a final decision until the woman is in labor. The following conditions are considered necessary in order to attempt a vaginal birth:

- The baby is full-term and in the frank breech presentation

- The baby does not show signs of distress while its heart rate is closely monitored.

- The process of labor is smooth and steady with the cervix widening as the baby descends.

- The health care provider estimates that the baby is not too big or the mother’s pelvis too narrow for the baby to pass safely through the birth canal.

- Anesthesia is available and a cesarean delivery possible on short notice

What are the risks and complications of a vaginal delivery?

In a breech birth, the baby’s head is the last part of its body to emerge making it more difficult to ease it through the birth canal. Sometimes forceps are used to guide the baby’s head out of the birth canal. Another potential problem is cord prolapse . In this situation the umbilical cord is squeezed as the baby moves toward the birth canal, thus slowing the baby’s supply of oxygen and blood. In a vaginal breech delivery, electronic fetal monitoring will be used to monitor the baby’s heartbeat throughout the course of labor. Cesarean delivery may be an option if signs develop that the baby may be in distress.

When is a cesarean delivery used with a breech presentation?

Most health care providers recommend a cesarean delivery for all babies in a breech position, especially babies that are premature. Since premature babies are small and more fragile, and because the head of a premature baby is relatively larger in proportion to its body, the baby is unlikely to stretch the cervix as much as a full-term baby. This means that there might be less room for the head to emerge.

Want to Know More?

- Creating Your Birth Plan

- Labor & Birth Terms to Know

- Cesarean Birth After Care

Compiled using information from the following sources:

- ACOG: If Your Baby is Breech

- William’s Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 24.

- Danforth’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Ninth Ed. Scott, James R., et al, Ch. 21.

BLOG CATEGORIES

- Can I get pregnant if… ? 3

- Child Adoption 19

- Fertility 54

- Pregnancy Loss 11

- Breastfeeding 29

- Changes In Your Body 5

- Cord Blood 4

- Genetic Disorders & Birth Defects 17

- Health & Nutrition 2

- Is it Safe While Pregnant 54

- Labor and Birth 65

- Multiple Births 10

- Planning and Preparing 24

- Pregnancy Complications 68

- Pregnancy Concerns 62

- Pregnancy Health and Wellness 149

- Pregnancy Products & Tests 8

- Pregnancy Supplements & Medications 14

- The First Year 41

- Week by Week Newsletter 40

- Your Developing Baby 16

- Options for Unplanned Pregnancy 18

- Paternity Tests 2

- Pregnancy Symptoms 5

- Prenatal Testing 16

- The Bumpy Truth Blog 7

- Uncategorized 4

- Abstinence 3

- Birth Control Pills, Patches & Devices 21

- Women's Health 34

- Thank You for Your Donation

- Unplanned Pregnancy

- Getting Pregnant

- Healthy Pregnancy

- Privacy Policy

Share this post:

Similar post.

Episiotomy: Advantages & Complications

Retained Placenta

What is Dilation in Pregnancy?

Track your baby’s development, subscribe to our week-by-week pregnancy newsletter.

- The Bumpy Truth Blog

- Fertility Products Resource Guide

Pregnancy Tools

- Ovulation Calendar

- Baby Names Directory

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Quiz

Pregnancy Journeys

- Partner With Us

- Corporate Sponsors

This topic will focus on vaginal birth of breech singletons, with a brief discussion of breech delivery at cesarean. Choosing the best route of birth for the fetus in breech presentation and delivery of the breech first or second twin are reviewed separately.

● (See "Overview of breech presentation", section on 'Approach to management at or near term' .)

- Help & Feedback

- About epocrates

Breech presentation

Highlights & basics, diagnostic approach, risk factors, history & exam, differential diagnosis.

- Tx Approach

Emerging Tx

Complications.

PATIENT RESOURCES

Patient Instructions

Breech presentation refers to the baby presenting for delivery with the buttocks or feet first rather than head.

Associated with increased morbidity and mortality for the mother in terms of emergency cesarean section and placenta previa; and for the baby in terms of preterm birth, small fetal size, congenital anomalies, and perinatal mortality.

Incidence decreases as pregnancy progresses and by term occurs in 3% to 4% of singleton term pregnancies.

Treatment options include external cephalic version to increase the likelihood of vaginal birth or a planned cesarean section, the optimal gestation being 37 and 39 weeks, respectively.

Planned cesarean section is considered the safest form of delivery for infants with a persisting breech presentation at term.

Quick Reference

Key Factors

buttocks or feet as the presenting part

Fetal head under costal margin, fetal heartbeat above the maternal umbilicus.

Other Factors

subcostal tenderness

Pelvic or bladder pain.

Diagnostics Tests

1st Tests to Order

transabdominal/transvaginal ultrasound

Treatment options.

presumptive

<37 weeks' gestation

specialist evaluation

corticosteroid

magnesium sulfate

≥37 weeks' gestation not in labor

unsuccessful ECV with persistent breech

Classifications

Types of breech presentation

Baby's buttocks lead the way into the birth canal

Hips are flexed, knees are extended, and the feet are in close proximity to the head

65% to 70% of breech babies are in this position.

Baby presents with buttocks first

Both the hips and the knees are flexed; the baby may be sitting cross-legged.

One or both of the baby's feet lie below the breech so that the foot or knee is lowermost in the birth canal

This is rare at term but relatively common with premature fetuses.

Common Vignette

Other Presentations

Epidemiology

33% of births less than 28 weeks' gestation

14% of births at 29 to 32 weeks' gestation

9% of births at 33 to 36 weeks' gestation

6% of births at 37 to 40 weeks' gestation.

Pathophysiology

- Natasha Nassar, PhD

- Christine L. Roberts, MBBS, FAFPHM, DrPH

- Jonathan Morris, MBChB, FRANZCOG, PhD

- John W. Bachman, MD

- Rhona Hughes, MBChB

- Brian Peat, MD

- Lelia Duley, MBChB

- Justus Hofmeyr, MD

Clinical exam

Palpation of the abdomen to determine the position of the baby's head

Palpation of the abdomen to confirm the position of the fetal spine on one side and fetal extremities on the other

Palpation of the area above the symphysis pubis to locate the fetal presenting part

Palpation of the presenting part to confirm presentation, to determine how far the fetus has descended and whether the fetus is engaged.

Ultrasound examination

Premature fetus.

Prematurity is consistently associated with breech presentation. [ 6 ] [ 9 ] This may be due to the smaller size of preterm infants, who are more likely to change their in utero position.

Increasing duration of pregnancy may allow breech-presenting fetuses time to grow, turn spontaneously or by external cephalic version, and remain cephalic-presenting.

Larger fetuses may be forced into a cephalic presentation in late pregnancy due to space or alignment constraints within the uterus.

small for gestational age fetus

Low birth-weight is a risk factor for breech presentation. [ 9 ] [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] [ 14 ] Term breech births are associated with a smaller fetal size for gestational age, highlighting the association with low birth-weight rather than prematurity. [ 6 ]

nulliparity

Women having a first birth have increased rates of breech presentation, probably due to the increased likelihood of smaller fetal size. [ 6 ] [ 9 ]

Relaxation of the uterine wall in multiparous women may reduce the odds of breech birth and contribute to a higher spontaneous or external cephalic version rate. [ 10 ]

fetal congenital anomalies

Congenital anomalies in the fetus may result in a small fetal size or inappropriate fetal growth. [ 9 ] [ 12 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ]

Anencephaly, hydrocephaly, Down syndrome, and fetal neuromuscular dysfunction are associated with breech presentation, the latter due to its effect on the quality of fetal movements. [ 9 ] [ 14 ]

previous breech delivery

The risk of recurrent breech delivery is 8%, the risk increasing from 4% after one breech delivery to 28% after three. [ 16 ]

The effects of recurrence may be due to recurring specific causal factors, either genetic or environmental in origin.

uterine abnormalities

Women with uterine abnormalities have a high incidence of breech presentation. [ 14 ] [ 17 ] [ 18 ] [ 19 ]

female fetus

Fifty-four percent of breech-presenting fetuses are female. [ 14 ]

abnormal amniotic fluid volume

Both oligohydramnios and polyhydramnios are associated with breech presentation. [ 1 ] [ 12 ] [ 14 ]

Low amniotic fluid volume decreases the likelihood of a fetus turning to a cephalic position; an increased amniotic fluid volume may facilitate frequent change in position.

placental abnormalities

An association between placental implantation in the cornual-fundal region and breech presentation has been reported, although some studies have not found it a risk factor. [ 8 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ] [ 22 ] [ 10 ] [ 14 ]

The association with placenta previa is also inconsistent. [ 8 ] [ 9 ] [ 22 ] Placenta previa is associated with preterm birth and may be an indirect risk factor.

Pelvic or vaginal examination reveals the buttocks and/or feet, felt as a yielding, irregular mass, as the presenting part. [ 26 ] In cephalic presentation, a hard, round, regular fetal head can be palpated. [ 26 ]

The Leopold maneuver on examination suggests breech position by palpation of the fetal head under the costal margin. [ 26 ]

The baby's heartbeat should be auscultated using a Pinard stethoscope or a hand-held Doppler to indicate the position of the fetus. The fetal heartbeat lies above the maternal umbilicus in breech presentation. [ 1 ]

Tenderness under one or other costal margin as a result of pressure by the harder fetal head.

Pain due to fetal kicks in the maternal pelvis or bladder.

breech position

Visualizes the fetus and reveals its position.

Used to confirm a clinically suspected breech presentation. [ 28 ]

Should be performed by practitioners with appropriate skills in obstetric ultrasound.

Establishes the type of breech presentation by imaging the fetal femurs and their relationship to the distal bones.

Transverse lie

Differentiating Signs/Symptoms

Fetus lies horizontally across the uterus with the shoulder as the presenting part.

Similar predisposing factors such as placenta previa, abnormal amniotic fluid volume, and uterine anomalies, although more common in multiparity. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 29 ]

Differentiating Tests

Clinical examination and fetal auscultation may be indicative.

Ultrasound confirms presentation.

Treatment Approach

Breech presentation <37 weeks' gestation.

The UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommends that corticosteroids should be offered to women between 24 and 34+6 weeks' gestation, in whom imminent preterm birth is anticipated. Corticosteroids should only be considered after discussion of risks/benefits at 35 to 36+6 weeks. Given within 7 days of preterm birth, corticosteroids may reduce perinatal and neonatal death and respiratory distress syndrome. [ 32 ] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends a single course of corticosteroids for pregnant women between 24 and 33+6 weeks' gestation who are at risk of preterm delivery within 7 days, including those with ruptured membranes and multiple gestations. It may also be considered for pregnant women starting at 23 weeks' gestation who are at risk of preterm delivery within 7 days. A single course of betamethasone is recommended for pregnant women between 34 and 36+6 weeks' gestation at risk of preterm birth within 7 days, and who have not received a previous course of prenatal corticosteroids. Regularly scheduled repeat courses or serial courses (more than two) are not currently recommended. A single repeat course of prenatal corticosteroids should be considered in women who are less than 34 weeks' gestation, who are at risk of preterm delivery within 7 days, and whose prior course of prenatal corticosteroids was administered more than 14 days previously. Rescue course corticosteroids could be provided as early as 7 days from the prior dose, if indicated by the clinical scenario. [ 33 ]

Magnesium sulfate given before anticipated early preterm birth reduces the risk of cerebral palsy in surviving infants. Physicians electing to use magnesium sulfate for fetal neuroprotection should develop specific guidelines regarding inclusion criteria, treatment regimens, and concurrent tocolysis. [ 34 ]

Breech presentation from 37 weeks' gestation, before labor

ECV is the initial treatment for a breech presentation at term when the patient is not in labor. It involves turning a fetus presenting by the breech to a cephalic (head-down) presentation to increase the likelihood of vaginal birth. [ 35 ] [ 36 ] Where available, it should be offered to all women in late pregnancy, by an experienced clinician, in hospitals with facilities for emergency delivery, and no contraindications to the procedure. [ 35 ] There is no upper time limit on the appropriate gestation for ECV, with success reported at 42 weeks.

There is no general consensus on contraindications to ECV. Contraindications include multiple pregnancy (except after delivery of a first twin), ruptured membranes, current or recent (<1 week) vaginal bleeding, rhesus isoimmunization, other indications for cesarean section (e.g., placenta previa or uterine malformation), or abnormal electronic fetal monitoring. [ 35 ] One systematic review of relative contraindications for ECV highlighted that most contraindications do not have clear empirical evidence. Exceptions include placental abruption, severe preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome, or signs of fetal distress (abnormal cardiotocography and/or Doppler flow). [ 36 ]

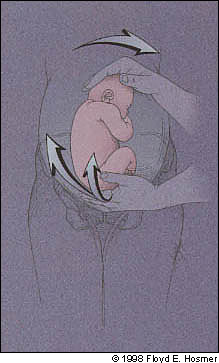

The procedure involves applying external pressure and firmly pushing or palpating the mother's abdomen to coerce the fetus to somersault (either forward or backward) into a cephalic position. [ 37 ]

The overall ECV success rate varies but, in a large series, 47% of women following an ECV attempt had a cephalic presentation at birth. [ 35 ] [ 38 ] Various factors influence the success rate. One systematic review found ECV success rates to be 68% overall, with the rate significantly higher for women from African countries (89%) compared with women from non-African countries (62%), and higher among multiparous (78%) than nulliparous women (48%). [ 39 ] Overall, the ECV success rates for nulliparous and multiparous non-African women were 43% and 73%, respectively, while for nulliparous and multiparous African women rates were 79% and 91%, respectively. Another study reported no difference in success rate or rate of cesarean section among women with previous cesarean section undergoing ECV compared with women with previous vaginal birth. However, numbers were small and further studies in this regard are required. [ 40 ]

Women's preference for vaginal delivery is a major contributing factor in their decision for ECV. However, studies suggest women with a breech presentation at term may not receive complete and/or evidence-based information about the benefits and risks of ECV. [ 41 ] [ 42 ] Although up to 60% of women reported ECV to be painful, the majority highlighted the benefits outweigh the risks (71%) and would recommend ECV to their friends or be willing to repeat for themselves (84%). [ 41 ] [ 42 ]

Cardiotocography and ultrasound should be performed before and after the procedure. Tocolysis should be used to facilitate the maneuver, and Rho(D) immune globulin should be administered to women who are Rhesus negative. [ 35 ] Tocolytic agents include adrenergic beta-2 receptor stimulants such as albuterol, terbutaline, or ritodrine (widely used with ECV in some countries, but not yet available in the US). One Cochrane review of tocolytic beta stimulants demonstrates that these are less likely to be associated with failed ECV, and are effective in increasing cephalic presentation and reducing cesarean section. [ 43 ] There is no current evidence to recommend one beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonist over another. Until these data are available, adherence to a local protocol for tocolysis is recommended. The Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning against using injectable terbutaline beyond 48 to 72 hours, or acute or prolonged treatment with oral terbutaline, in pregnant women for the prevention or prolonged treatment of preterm labor, due to potential serious maternal cardiac adverse effects and death. [ 44 ] Whether this warning applies to the subcutaneous administration of terbutaline in ECV is still unclear; however, studies currently support this use. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommends that injectable beta agonists should be used for up to 48 hours between the 22nd and 37th week of pregnancy only. They should be used under specialist supervision with continuous monitoring of the mother and unborn baby owing to the risk of adverse cardiovascular effects in both the mother and baby. The EMA no longer recommends oral or rectal formulations for obstetric indications. [ 45 ]

If ECV is successful, pregnancy care should continue as usual for any cephalic presentation. One systematic review assessing the mode of delivery after a successful ECV found that these women were at increased risk for cesarean section and instrumental vaginal delivery compared with women with spontaneous cephalic pregnancies. However, they still had a lower rate of cesarean section following ECV (i.e., 47%) compared with the cesarean section rate for those with a persisting breech (i.e., 85%). With a number needed to treat of three, ECV is still considered to be an effective means of preventing the need for cesarean section. [ 46 ]

Planned cesarean section should be offered as the safest mode of delivery for the baby, even though it carries a small increase in serious immediate maternal complications compared with vaginal birth. [ 24 ] [ 25 ] [ 31 ] In the US, most unsuccessful ECV with persistent breech will be delivered via cesarean section.

A vaginal mode of delivery may be considered by some clinicians as an option, particularly when maternal request is provided, senior and experienced staff are available, there is no absolute contraindication to vaginal birth (e.g., placenta previa, compromised fetal condition), and with optimal fetal growth (estimated weight above the tenth centile and up to 3800 g). Other factors that make planned vaginal birth higher risk include hyperextended neck on ultrasound and footling presentation. [ 24 ]

Breech presentation from 37 weeks' gestation, during labor

The first option should be a planned cesarean section.

There is a small increase in the risk of serious immediate maternal complications compared with vaginal birth (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.61), including pulmonary embolism, infection, bleeding, damage to the bladder and bowel, slower recovery from the delivery, longer hospitalization, and delayed bonding and breast-feeding. [ 23 ] [ 31 ] [ 47 ] [ 48 ] [ 49 ] [ 50 ] [ 51 ] [ 52 ] [ 53 ] [ 54 ] [ 55 ] [ 56 ] [ 57 ] [ 58 ] Consider using antimicrobial triclosan-coated sutures for wound closure to reduce the risk of surgical site infection. [ 59 ]

The long-term risks include potential compromise of future obstetric performance, increased risk of repeat cesarean section, infertility, uterine rupture, placenta accreta, placental abruption, and emergency hysterectomy. [ 60 ] [ 61 ] [ 62 ] [ 63 ]

Planned cesarean section is safer for babies, but is associated with increased neonatal respiratory distress. The risk is reduced when the section is performed at 39 weeks' gestation. [ 64 ] [ 65 ] [ 66 ] For women undergoing a planned cesarean section, RCOG recommends an informed discussion about the potential risks and benefits of a course of prenatal corticosteroids between 37 and 38+6 weeks' gestation. Although prenatal corticosteroids may reduce admission to the neonatal unit for respiratory morbidity, it is uncertain if there is any reduction in respiratory distress syndrome, transient tachypnea of the newborn, or neonatal unit admission overall. In addition, prenatal corticosteroids may result in harm to the neonate, including hypoglycemia and potential developmental delay. [ 32 ] ACOG does not recommend corticosteroids in women >37 weeks' gestation. [ 33 ]

Undiagnosed breech in labor generally results in cesarean section after the onset of labor, higher rates of emergency cesarean section associated with the least favorable maternal outcomes, a greater likelihood of cord prolapse, and other poor infant outcomes. [ 23 ] [ 67 ] [ 49 ] [ 68 ] [ 69 ] [ 70 ] [ 71 ]

This mode of delivery may be considered by some clinicians as an option for women who are in labor, particularly when delivery is imminent. Vaginal breech delivery may also be considered, where suitable, when delivery is not imminent, maternal request is provided, senior and experienced staff are available, there is no absolute contraindication to vaginal birth (e.g., placenta previa, compromised fetal condition), and with optimal fetal growth (estimated weight above the tenth centile and up to 3800 g). Other factors that make planned vaginal birth higher risk include hyperextended neck on ultrasound and footling presentation. [ 24 ]

Findings from one systematic review of 27 observational studies revealed that the absolute risks of perinatal mortality, fetal neurologic morbidity, birth trauma, 5-minute Apgar score <7, and neonatal asphyxia in the planned vaginal delivery group were low at 0.3%, 0.7%, 0.7%, 2.4%, and 3.3%, respectively. However, the relative risks of perinatal mortality and morbidity were 2- to 5-fold higher in the planned vaginal than in the planned cesarean delivery group. Authors recommend ongoing judicious decision-making for vaginal breech delivery for selected singleton, term breech babies. [ 72 ]

ECV may also be considered an option for women with breech presentation in early labor, when delivery is not imminent, provided that the membranes are intact.

A woman presenting with a breech presentation <37 weeks is an area of clinical controversy. Optimal mode of delivery for preterm breech has not been fully evaluated in clinical trials, and the relative risks for the preterm infant and mother remain unclear. In the absence of good evidence, if diagnosis of breech presentation prior to 37 weeks' gestation is made, prematurity and clinical circumstances should determine management and mode of delivery.

Primary Options

12 mg intramuscularly every 24 hours for 2 doses

6 mg intramuscularly every 12 hours for 4 doses

The UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommends that corticosteroids should be offered to women between 24 and 34+6 weeks' gestation, in whom imminent preterm birth is anticipated. Corticosteroids should only be considered after discussion of risks/benefits at 35 to 36+6 weeks. Given within 7 days of preterm birth, corticosteroids may reduce perinatal and neonatal death and respiratory distress syndrome. [ 32 ]

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends a single course of corticosteroids for pregnant women between 24 and 33+6 weeks' gestation who are at risk of preterm delivery within 7 days, including those with ruptured membranes and multiple gestations. It may also be considered for pregnant women starting at 23 weeks' gestation who are at risk of preterm delivery within 7 days. A single course of betamethasone is recommended for pregnant women between 34 and 36+6 weeks' gestation at risk of preterm birth within 7 days, and who have not received a previous course of prenatal corticosteroids. Regularly scheduled repeat courses or serial courses (more than two) are not currently recommended. A single repeat course of prenatal corticosteroids should be considered in women who are less than 34 weeks' gestation, who are at risk of preterm delivery within 7 days, and whose prior course of prenatal corticosteroids was administered more than 14 days previously. Rescue course corticosteroids could be provided as early as 7 days from the prior dose, if indicated by the clinical scenario. [ 33 ]

consult specialist for guidance on dose

external cephalic version (ECV)

There is no upper time limit on the appropriate gestation for ECV; it should be offered to all women in late pregnancy by an experienced clinician in hospitals with facilities for emergency delivery and no contraindications to the procedure. [ 35 ] [ 36 ]

ECV involves applying external pressure and firmly pushing or palpating the mother's abdomen to coerce the fetus to somersault (either forward or backward) into a cephalic position. [ 37 ]

There is no general consensus on contraindications to ECV. Contraindications include multiple pregnancy (except after delivery of a first twin), ruptured membranes, current or recent (<1 week) vaginal bleeding, rhesus isoimmunization, other indications for cesarean section (e.g., placenta previa or uterine malformation), or abnormal electronic fetal monitoring. [ 35 ] One systematic review of relative contraindications for ECV highlighted that most contraindications do not have clear empirical evidence. Exceptions include placental abruption, severe preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome, or signs of fetal distress (abnormal cardiotocography and/or Doppler flow). [ 36 ]

Cardiotocography and ultrasound should be performed before and after the procedure.

If ECV is successful, pregnancy care should continue as usual for any cephalic presentation. A systematic review assessing the mode of delivery after a successful ECV found that these women were at increased risk for cesarean section and instrumental vaginal delivery compared with women with spontaneous cephalic pregnancies. However, they still had a lower rate of cesarean section following ECV (i.e., 47%) compared with the cesarean section rate for those with a persisting breech (i.e., 85%). With a number needed to treat of 3, ECV is still considered to be an effective means of preventing the need for cesarean section. [ 46 ]

tocolytic agents

see local specialist protocol for dosing guidelines

Tocolytic agents include adrenergic beta-2 receptor stimulants such as albuterol, terbutaline, or ritodrine (widely used with external cephalic version [ECV] in some countries, but not yet available in the US). They are used to delay or inhibit labor and increase the success rate of ECV. There is no current evidence to recommend one beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonist over another. Until these data are available, adherence to a local protocol for tocolysis is recommended.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning against using injectable terbutaline beyond 48-72 hours, or acute or prolonged treatment with oral terbutaline, in pregnant women for the prevention or prolonged treatment of preterm labor, due to potential serious maternal cardiac adverse effects and death. [ 44 ] Whether this warning applies to the subcutaneous administration of terbutaline in ECV is still unclear; however, studies currently support this use. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommends that injectable beta agonists should be used for up to 48 hours between the 22nd and 37th week of pregnancy only. They should be used under specialist supervision with continuous monitoring of the mother and unborn baby owing to the risk of adverse cardiovascular effects in both the mother and baby. The EMA no longer recommends oral or rectal formulations for obstetric indications. [ 45 ]

A systematic review found there was no evidence to support the use of nifedipine for tocolysis. [ 73 ]

There is insufficient evidence to evaluate other interventions to help ECV, such as fetal acoustic stimulation in midline fetal spine positions, or epidural or spinal analgesia. [ 43 ]

Rho(D) immune globulin

300 micrograms intramuscularly as a single dose

Nonsensitized Rh-negative women should receive Rho(D) immune globulin. [ 35 ]

The indication for its administration is to prevent rhesus isoimmunization, which may affect subsequent pregnancy outcomes.

Rho(D) immune globulin needs to be given at the time of external cephalic version and should be given again postpartum to those women who give birth to an Rh-positive baby. [ 74 ]

It is best administered as soon as possible after the procedure, usually within 72 hours.

Dose depends on brand used. Dose given below pertains to most commonly used brands. Consult specialist for further guidance on dose.

elective cesarean section/vaginal breech delivery

Mode of delivery (cesarean section or vaginal breech delivery) should be based on the experience of the attending clinician, hospital policies, maternal request, and the presence or absence of complicating factors. In the US, most unsuccessful external cephalic version (ECV) with persistent breech will be delivered via cesarean section.

Cesarean section, at 39 weeks or greater, has been shown to significantly reduce perinatal mortality and neonatal morbidity compared with vaginal breech delivery (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.56). [ 31 ] Although safer for these babies, there is a small increase in serious immediate maternal complications compared with vaginal birth (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.61), as well as long-term risks for future pregnancies, including pulmonary embolism, bleeding, infection, damage to the bladder and bowel, slower recovery from the delivery, longer hospitalization, and delayed bonding and breast-feeding. [ 23 ] [ 31 ] [ 47 ] [ 48 ] [ 49 ] [ 50 ] [ 51 ] [ 52 ] [ 53 ] [ 54 ] [ 55 ] [ 56 ] [ 57 ] [ 58 ] Consider using antimicrobial triclosan-coated sutures for wound closure to reduce the risk of surgical site infection. [ 59 ]

Vaginal delivery may be considered by some clinicians as an option, particularly when maternal request is provided, when senior and experienced staff are available, when there is no absolute contraindication to vaginal birth (e.g., placenta previa, compromised fetal condition), and with optimal fetal growth (estimated weight above the tenth centile and up to 3800 g). Other factors that make planned vaginal birth higher risk include hyperextended neck on ultrasound and footling presentation. [ 24 ]

For women undergoing a planned cesarean section, the UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommends an informed discussion about the potential risks and benefits of a course of prenatal corticosteroids between 37 and 38+6 weeks' gestation. Although prenatal corticosteroids may reduce admission to the neonatal unit for respiratory morbidity, it is uncertain if there is any reduction in respiratory distress syndrome, transient tachypnea of the newborn, or neonatal unit admission overall. In addition, prenatal corticosteroids may result in harm to the neonate, including hypoglycemia and potential developmental delay. [ 32 ] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend corticosteroids in women >37 weeks' gestation. [ 33 ]

It is best administered as soon as possible after delivery, usually within 72 hours.

Administration of postpartum Rho (D) immune globulin should not be affected by previous routine prenatal prophylaxis or previous administration for a potentially sensitizing event. [ 74 ]

≥37 weeks' gestation in labor: no imminent delivery

planned cesarean section

For women with breech presentation in labor, planned cesarean section at 39 weeks or greater has been shown to significantly reduce perinatal mortality and neonatal morbidity compared with vaginal breech delivery (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.56). [ 31 ]

Although safer for these babies, there is a small increase in serious immediate maternal complications compared with vaginal birth (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.61), as well as long-term risks for future pregnancies, including pulmonary embolism, infection, bleeding, damage to the bladder and bowel, slower recovery from the delivery, longer hospitalization, and delayed bonding and breast-feeding. [ 23 ] [ 31 ] [ 47 ] [ 48 ] [ 49 ] [ 50 ] [ 51 ] [ 52 ] [ 53 ] [ 54 ] [ 55 ] [ 56 ] [ 57 ] [ 58 ] Consider using antimicrobial triclosan-coated sutures for wound closure to reduce the risk of surgical site infection. [ 59 ]

Continuous cardiotocography monitoring should continue until delivery. [ 24 ] [ 25 ]

vaginal breech delivery

Mode of delivery (cesarean section or vaginal breech delivery) should be based on the experience of the attending clinician, hospital policies, maternal request, and the presence or absence of complicating factors.

This mode of delivery may be considered by some clinicians as an option, particularly when maternal request is provided, when senior and experienced staff are available, when there is no absolute contraindication to vaginal birth (e.g., placenta previa, compromised fetal condition), and with optimal fetal growth (estimated weight above the tenth centile and up to 3800 g). Other factors that make planned vaginal birth higher risk include hyperextended neck on ultrasound and footling presentation. [ 24 ]

For women with persisting breech presentation, planned cesarean section has, however, been shown to significantly reduce perinatal mortality and neonatal morbidity compared with vaginal breech delivery (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.56). [ 31 ]

ECV may also be considered an option for women with breech presentation in early labor, provided that the membranes are intact.

There is no upper time limit on the appropriate gestation for ECV. [ 35 ]

Involves applying external pressure and firmly pushing or palpating the mother's abdomen to coerce the fetus to somersault (either forward or backward) into a cephalic position. [ 37 ]

Relative contraindications include placental abruption, severe preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome, and signs of fetal distress (abnormal cardiotocography and/or abnormal Doppler flow). [ 35 ] [ 36 ]

Rho(D) immune globulin needs to be given at the time of ECV and should be given again postpartum to those women who give birth to an Rh-positive baby. [ 74 ]

≥37 weeks' gestation in labor: imminent delivery

cesarean section

For women with persistent breech presentation, planned cesarean section has been shown to significantly reduce perinatal mortality and neonatal morbidity compared with vaginal breech delivery (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.56). [ 31 ] Although safer for these babies, there is a small increase in serious immediate maternal complications compared with vaginal birth (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.61), as well as long-term risks for future pregnancies, including pulmonary embolism, infection, bleeding, damage to the bladder and bowel, slower recovery from the delivery, longer hospitalization, and delayed bonding and breast-feeding. [ 23 ] [ 31 ] [ 47 ] [ 48 ] [ 49 ] [ 50 ] [ 51 ] [ 52 ] [ 53 ] [ 54 ] [ 55 ] [ 56 ] [ 57 ] [ 58 ] Consider using antimicrobial triclosan-coated sutures for wound closure to reduce the risk of surgical site infection. [ 59 ]

This mode of delivery may be considered by some clinicians as an option, particularly when delivery is imminent, maternal request is provided, when senior and experienced staff are available, when there is no absolute contraindication to vaginal birth (e.g., placenta previa, compromised fetal condition), and with optimal fetal growth (estimated weight above the tenth centile and up to 3800 g). Other factors that make planned vaginal birth higher risk include hyperextended neck on ultrasound and footling presentation. [ 24 ]

It is best administered as soon as possible after the delivery, usually within 72 hours.

External cephalic version before term

Moxibustion, postural management, follow-up overview, perinatal complications.

Compared with cephalic presentation, persistent breech presentation has increased frequency of cord prolapse, abruptio placentae, prelabor rupture of membranes, perinatal mortality, fetal distress (heart rate <100 bpm), preterm delivery, lower fetal weight. [ 10 ] [ 11 ] [ 67 ]

complications of cesarean section

There is a small increase in the risk of serious immediate maternal complications compared with vaginal birth (RR 1.29, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.61), including pulmonary embolism, infection, bleeding, damage to the bladder and bowel, slower recovery from the delivery, longer hospitalization, and delayed bonding and breast-feeding. [ 23 ] [ 31 ] [ 47 ] [ 48 ] [ 49 ] [ 50 ] [ 51 ] [ 52 ] [ 53 ] [ 54 ] [ 55 ] [ 56 ] [ 57 ] [ 58 ]

The long-term risks include potential compromise of future obstetric performance, increased risk of repeat cesarean section, infertility, uterine rupture, placenta accreta, placental abruption, and emergency hysterectomy. [ 60 ] [ 61 ] [ 62 ] [ 63 ] The evidence suggests that using sutures, rather than staples, for wound closure after cesarean section reduces the incidence of wound dehiscence. [ 59 ]

Emergency cesarean section, compared with planned cesarean section, has demonstrated a higher risk of severe obstetric morbidity, intra-operative complications, postoperative complications, infection, blood loss >1500 mL, fever, pain, tiredness, and breast-feeding problems. [ 23 ] [ 48 ] [ 50 ] [ 70 ] [ 81 ]

Key Articles

Impey LWM, Murphy DJ, Griffiths M, et al; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of breech presentation: green-top guideline no. 20b. BJOG. 2017 Jun;124(7):e151-77. [Full Text]

Hofmeyr GJ, Hannah M, Lawrie TA. Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jul 21;(7):CD000166. [Abstract] [Full Text]

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. External cephalic version and reducing the incidence of term breech presentation. March 2017 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

Cluver C, Gyte GM, Sinclair M, et al. Interventions for helping to turn term breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb 9;(2):CD000184. [Abstract] [Full Text]

de Hundt M, Velzel J, de Groot CJ, et al. Mode of delivery after successful external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;123(6):1327-34. [Abstract]

Referenced Articles

1. Cunningham F, Gant N, Leveno K, et al. Williams obstetrics. 21st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1997.

2. Kish K, Collea JV. Malpresentation and cord prolapse. In: DeCherney AH, Nathan L, eds. Current obstetric and gynecologic diagnosis and treatment. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2002.

3. Scheer K, Nubar J. Variation of fetal presentation with gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976 May 15;125(2):269-70. [Abstract]

4. Nassar N, Roberts CL, Cameron CA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical examination for detection of non-cephalic presentation in late pregnancy: cross sectional analytic study. BMJ. 2006 Sep 16;333(7568):578-80. [Abstract] [Full Text]

5. Roberts CL, Peat B, Algert CS, et al. Term breech birth in New South Wales, 1990-1997. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000 Feb;40(1):23-9. [Abstract]

6. Roberts CL, Algert CS, Peat B, et al. Small fetal size: a risk factor for breech birth at term. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999 Oct;67(1):1-8. [Abstract]

7. Brar HS, Platt LD, DeVore GR, et al. Fetal umbilical velocimetry for the surveillance of pregnancies complicated by placenta previa. J Reprod Med. 1988 Sep;33(9):741-4. [Abstract]

8. Kian L. The role of the placental site in the aetiology of breech presentation. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1963 Oct;70:795-7. [Abstract]

9. Rayl J, Gibson PJ, Hickok DE. A population-based case-control study of risk factors for breech presentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Jan;174(1 Pt 1):28-32. [Abstract]

10. Westgren M, Edvall H, Nordstrom L, et al. Spontaneous cephalic version of breech presentation in the last trimester. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985 Jan;92(1):19-22. [Abstract]

11. Brenner WE, Bruce RD, Hendricks CH. The characteristics and perils of breech presentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974 Mar 1;118(5):700-12. [Abstract]

12. Hall JE, Kohl S. Breech presentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1956 Nov;72(5):977-90. [Abstract]

13. Morgan HS, Kane SH. An analysis of 16,327 breech births. JAMA. 1964 Jan 25;187:262-4. [Abstract]

14. Luterkort M, Persson P, Weldner B. Maternal and fetal factors in breech presentation. Obstet Gynecol. 1984 Jul;64(1):55-9. [Abstract]

15. Braun FH, Jones KL, Smith DW. Breech presentation as an indicator of fetal abnormality. J Pediatr. 1975 Mar;86(3):419-21. [Abstract]

16. Albrechtsen S, Rasmussen S, Dalaker K, et al. Reproductive career after breech presentation: subsequent pregnancy rates, interpregnancy interval, and recurrence. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Sep;92(3):345-50. [Abstract]

17. Zlopasa G, Skrablin S, Kalafatić D, et al. Uterine anomalies and pregnancy outcome following resectoscope metroplasty. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007 Aug;98(2):129-33. [Abstract]

18. Acién P. Breech presentation in Spain, 1992: a collaborative study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995 Sep;62(1):19-24. [Abstract]

19. Michalas SP. Outcome of pregnancy in women with uterine malformation: evaluation of 62 cases. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1991 Jul;35(3):215-9. [Abstract]

20. Fianu S, Vaclavinkova V. The site of placental attachment as a factor in the aetiology of breech presentation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1978;57(4):371-2. [Abstract]

21. Haruyama Y. Placental implantation as the cause of breech presentation [in Japanese]. Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi. 1987 Jan;39(1):92-8. [Abstract]

22. Filipov E, Borisov I, Kolarov G. Placental location and its influence on the position of the fetus in the uterus [in Bulgarian]. Akush Ginekol (Sofiia). 2000;40(4):11-2. [Abstract]

23. Waterstone M, Bewley S, Wolfe C. Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: case-control study. BMJ. 2001 May 5;322(7294):1089-93. [Abstract] [Full Text]

24. Impey LWM, Murphy DJ, Griffiths M, et al; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of breech presentation: green-top guideline no. 20b. BJOG. 2017 Jun;124(7):e151-77. [Full Text]

25. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 745: mode of term singleton breech delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Aug;132(2):e60-3. [Abstract] [Full Text]

26. Beischer NA, Mackay EV, Colditz P, eds. Obstetrics and the newborn: an illustrated textbook. 3rd ed. London: W.B. Saunders; 1997.

27. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Antepartum haemorrhage: green-top guideline no. 63. November 2011 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

28. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 175: ultrasound in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Dec;128(6):e241-56. [Abstract]

29. Enkin M, Keirse MJNC, Neilson J, et al. Guide to effective care in pregnancy and childbirth. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.

30. Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Oct 17;(10):CD000083. [Abstract] [Full Text]

31. Hofmeyr GJ, Hannah M, Lawrie TA. Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jul 21;(7):CD000166. [Abstract] [Full Text]

32. Stock SJ, Thomson AJ, Papworth S, et al. Antenatal corticosteroids to reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality: Green-top Guideline No. 74. BJOG. 2022 Jul;129(8):e35-60. [Abstract] [Full Text]

33. American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee opinion no. 713: antenatal corticosteroid therapy for fetal maturation. August 2017 (reaffirmed 2020) [internet publication]. [Full Text]

34. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee opinion no. 455: magnesium sulfate before anticipated preterm birth for neuroprotection. March 2010 (reaffirmed 2020) [internet publication]. [Full Text]

35. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. External cephalic version and reducing the incidence of term breech presentation. March 2017 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

36. Rosman AN, Guijt A, Vlemmix F, et al. Contraindications for external cephalic version in breech position at term: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013 Feb;92(2):137-42. [Abstract]

37. Hofmeyr GJ. Effect of external cephalic version in late pregnancy on breech presentation and caesarean section rate: a controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983 May;90(5):392-9. [Abstract]

38. Beuckens A, Rijnders M, Verburgt-Doeleman GH, et al. An observational study of the success and complications of 2546 external cephalic versions in low-risk pregnant women performed by trained midwives. BJOG. 2016 Feb;123(3):415-23. [Abstract]

39. Nassar N, Roberts CL, Barratt A, et al. Systematic review of adverse outcomes of external cephalic version and persisting breech presentation at term. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006 Mar;20(2):163-71. [Abstract]

40. Sela HY, Fiegenberg T, Ben-Meir A, et al. Safety and efficacy of external cephalic version for women with a previous cesarean delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009 Feb;142(2):111-4. [Abstract]

41. Pichon M, Guittier MJ, Irion O, et al. External cephalic version in case of persisting breech presentation at term: motivations and women's experience of the intervention [in French]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2013 Jul-Aug;41(7-8):427-32. [Abstract]

42. Nassar N, Roberts CL, Raynes-Greenow CH, et al. Evaluation of a decision aid for women with breech presentation at term: a randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN14570598]. BJOG. 2007 Mar;114(3):325-33. [Abstract] [Full Text]

43. Cluver C, Gyte GM, Sinclair M, et al. Interventions for helping to turn term breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb 9;(2):CD000184. [Abstract] [Full Text]

44. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: new warnings against use of terbutaline to treat preterm labor. Feb 2011 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

45. European Medicines Agency. Restrictions on use of short-acting beta-agonists in obstetric indications - CMDh endorses PRAC recommendations. October 2013 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

46. de Hundt M, Velzel J, de Groot CJ, et al. Mode of delivery after successful external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;123(6):1327-34. [Abstract]

47. Lydon-Rochelle M, Holt VL, Martin DP, et al. Association between method of delivery and maternal rehospitalisation. JAMA. 2000 May 10;283(18):2411-6. [Abstract]

48. Yokoe DS, Christiansen CL, Johnson R, et al. Epidemiology of and surveillance for postpartum infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001 Sep-Oct;7(5):837-41. [Abstract]

49. van Ham MA, van Dongen PW, Mulder J. Maternal consequences of caesarean section. A retrospective study of intra-operative and postoperative maternal complications of caesarean section during a 10-year period. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997 Jul;74(1):1-6. [Abstract]

50. Murphy DJ, Liebling RE, Verity L, et al. Early maternal and neonatal morbidity associated with operative delivery in second stage of labour: a cohort study. Lancet. 2001 Oct 13;358(9289):1203-7. [Abstract]

51. Lydon-Rochelle MT, Holt VL, Martin DP. Delivery method and self-reported postpartum general health status among primiparous women. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001 Jul;15(3):232-40. [Abstract]

52. Wilson PD, Herbison RM, Herbison GP. Obstetric practice and the prevalence of urinary incontinence three months after delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996 Feb;103(2):154-61. [Abstract]

53. Persson J, Wolner-Hanssen P, Rydhstroem H. Obstetric risk factors for stress urinary incontinence: a population-based study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Sep;96(3):440-5. [Abstract]

54. MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH, et al. The prevalence of pelvic disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. BJOG. 2000 Dec;107(12):1460-70. [Abstract]

55. Thompson JF, Roberts CL, Currie M, et al. Prevalence and persistence of health problems after childbirth: associations with parity and method of birth. Birth. 2002 Jun;29(2):83-94. [Abstract]

56. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's mothers and babies 2015 - in brief. October 2017 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

57. Mutryn CS. Psychosocial impact of cesarean section on the family: a literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1993 Nov;37(10):1271-81. [Abstract]

58. DiMatteo MR, Morton SC, Lepper HS, et al. Cesarean childbirth and psychosocial outcomes: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 1996 Jul;15(4):303-14. [Abstract]

59. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Caesarean birth. Mar 2021 [internet publication]. [Full Text]

60. Greene R, Gardeit F, Turner MJ. Long-term implications of cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997 Jan;176(1 Pt 1):254-5. [Abstract]

61. Coughlan C, Kearney R, Turner MJ. What are the implications for the next delivery in primigravidae who have an elective caesarean section for breech presentation? BJOG. 2002 Jun;109(6):624-6. [Abstract]

62. Hemminki E, Merilainen J. Long-term effects of cesarean sections: ectopic pregnancies and placental problems. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 May;174(5):1569-74. [Abstract]

63. Gilliam M, Rosenberg D, Davis F. The likelihood of placenta previa with greater number of cesarean deliveries and higher parity. Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;99(6):976-80. [Abstract]

64. Morrison JJ, Rennie JM, Milton PJ. Neonatal respiratory morbidity and mode of delivery at term: influence of timing of elective caesarean section. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995 Feb;102(2):101-6. [Abstract]

65. Annibale DJ, Hulsey TC, Wagner CL, et al. Comparative neonatal morbidity of abdominal and vaginal deliveries after uncomplicated pregnancies. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995 Aug;149(8):862-7. [Abstract]

66. Hook B, Kiwi R, Amini SB, et al. Neonatal morbidity after elective repeat cesarean section and trial of labor. Pediatrics. 1997 Sep;100(3 Pt 1):348-53. [Abstract]

67. Nassar N, Roberts CL, Cameron CA, et al. Outcomes of external cephalic version and breech presentation at term: an audit of deliveries at a Sydney tertiary obstetric hospital, 1997-2004. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(10):1231-8. [Abstract]

68. Nwosu EC, Walkinshaw S, Chia P, et al. Undiagnosed breech. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993 Jun;100(6):531-5. [Abstract]

69. Flamm BL, Ruffini RM. Undetected breech presentation: impact on external version and cesarean rates. Am J Perinatol. 1998 May;15(5):287-9. [Abstract]

70. Cockburn J, Foong C, Cockburn P. Undiagnosed breech. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994 Jul;101(7):648-9. [Abstract]

71. Leung WC, Pun TC, Wong WM. Undiagnosed breech revisited. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999 Jul;106(7):638-41. [Abstract]

72. Berhan Y, Haileamlak A. The risks of planned vaginal breech delivery versus planned caesarean section for term breech birth: a meta-analysis including observational studies. BJOG. 2016 Jan;123(1):49-57. [Abstract] [Full Text]

73. Wilcox C, Nassar N, Roberts C. Effectiveness of nifedipine tocolysis to facilitate external cephalic version: a systematic review. BJOG. 2011 Mar;118(4):423-8. [Abstract]

74. Qureshi H, Massey E, Kirwan D, et al. BCSH guideline for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin for the prevention of haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn. Transfus Med. 2014 Feb;24(1):8-20. [Abstract] [Full Text]

75. Hutton EK, Hofmeyr GJ, Dowswell T. External cephalic version for breech presentation before term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jul 29;(7):CD000084. [Abstract] [Full Text]

76. Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 May 16;(5):CD003928. [Abstract] [Full Text]

77. Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Oct 17;(10):CD000051. [Abstract] [Full Text]

78. Hannah ME, Whyte H, Hannah WJ, et al. Maternal outcomes at 2 years after planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: the International Randomized Term Breech Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Sep;191(3):917-27. [Abstract]

79. Eide MG, Oyen N, Skjaerven R, et al. Breech delivery and Intelligence: a population-based study of 8,738 breech infants. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jan;105(1):4-11. [Abstract]

80. Whyte H, Hannah ME, Saigal S, et al. Outcomes of children at 2 years after planned cesarean birth versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: the International Randomized Term Breech Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Sep;191(3):864-71. [Abstract]

81. Brown S, Lumley J. Maternal health after childbirth: results of an Australian population based survey. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998 Feb;105(2):156-61. [Abstract]

Published by

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

2016 (reaffirmed 2022)

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (UK)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK)

Topic last updated: 2024-03-05

Natasha Nassar , PhD

Associate Professor

Menzies Centre for Health Policy

Sydney School of Public Health

University of Sydney

Christine L. Roberts , MBBS, FAFPHM, DrPH

Research Director

Clinical and Population Health Division

Perinatal Medicine Group

Kolling Institute of Medical Research

Jonathan Morris , MBChB, FRANZCOG, PhD

Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Head of Department

Peer Reviewers

John W. Bachman , MD

Consultant in Family Medicine

Department of Family Medicine

Mayo Clinic

Rhona Hughes , MBChB

Lead Obstetrician

Lothian Simpson Centre for Reproductive Health

The Royal Infirmary

Brian Peat , MD

Director of Obstetrics

Women's and Children's Hospital

North Adelaide

South Australia

Lelia Duley , MBChB

Professor of Obstetric Epidemiology

University of Leeds

Bradford Institute of Health Research

Temple Bank House

Bradford Royal Infirmary

Justus Hofmeyr , MD

Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

East London Private Hospital

East London

South Africa

ANDREW S. COCO, M.D., M.S., AND STEPHANIE D. SILVERMAN, M.D.

Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(3):731-738

See related patient information handout on external cephalic version , written by the authors of this article.

External cephalic version is a procedure that externally rotates the fetus from a breech presentation to a vertex presentation. External version has made a resurgence in the past 15 years because of a strong safety record and a success rate of about 65 percent. Before the resurgence of the use of external version, the only choices for breech delivery were cesarean section or a trial of labor. It is preferable to wait until term (37 weeks of gestation) before external version is attempted because of an increased success rate and avoidance of preterm delivery if complications arise. After the fetal head is gently disengaged, the fetus is manipulated by a forward roll or back flip. If unsuccessful, the version can be reattempted at a later time. The procedure should only be performed in a facility equipped for emergency cesarean section. The use of external cephalic version can produce considerable cost savings in the management of the breech fetus at term. It is a skill easily acquired by family physicians and should be a routine part of obstetric practice.

The incidence of breech presentation at term is about 4 percent. 1 Multiple factors may cause a fetus to present breech instead of vertex, including placenta previa, multiple gestation, uterine anomalies, fetal anomalies, poor uterine tone and prematurity. The majority of cases have no apparent cause. Physicians performing external cephalic version (also referred to as external version) externally rotate the fetus from a breech presentation to a vertex presentation. Over the past 15 years, external cephalic version has become a valuable, although underused, option in the management of the breech fetus at term.

Before the resurgence of the use of external cephalic version, management of breech presentation consisted of either routine cesarean delivery or a selected trial of labor. However, over the past two decades, theoretically for safety concerns regarding the fetus, the rate of cesarean delivery for breech presentation increased from 14 percent in 1970 to the current rate of up to 100 percent at some institutions. 2 Very few trials of labor are being attempted. Approximately 12 percent of cesarean deliveries in the United States are performed for breech presentation. Breech presentation ranks as the third most frequent indication for cesarean section, following previous cesarean section and labor dystocia. 3 Routine use of external version could reduce the rate of cesarean delivery by about two thirds. 4

This article reviews the rationale for the use of external version and its technical aspects, including the currently accepted protocol and manual maneuvers, factors predicting success and cost-effectiveness.

History of External Cephalic Version

External version has apparently been practiced since the time of Aristotle (384 to 322 B.C.), who stated that many of his fellow authors advised midwives who were confronted with a breech presentation to “change the figure and place the head so that it may present at birth.” However, external version eventually fell out of favor as a result of several concerns: its high rate of spontaneous reversion (turning back to breech presentation) if performed before 36 weeks of gestation, possible fetal complications, and the assumption that an external version converts only those fetuses to vertex that would have converted spontaneously anyway.

The rebirth of the use of external version occurred in the early 1980s in the United States, after a protocol developed in Berlin was replicated with favorable results in several U.S. studies. 5 , 6 Consumer demands for more noninterventional birth experiences also played a role in its resurgence. Currently, external version is performed in many institutions, and the procedure is taught in most obstetric residency programs and in some family practice residency programs.

The safety of vaginal breech delivery has been a longstanding controversy. In a recent retrospective study, 7 investigators found that the risk of fetal morbidity and mortality is increased when vaginal delivery is attempted and concluded that cesarean section should be recommended routinely. In another study, 8 however, investigators reached an opposite conclusion. They calculated a corrected perinatal mortality of zero based on a series of 316 women undergoing a trial of labor.