Debriefing Process Guidance

In the course of designing a research project, researchers may find it useful to include a debriefing of the study for participants at the close of the project. The debriefing process is a requirement for studies that employ deception (#1 below), however it could also be used as an educational tool (#2 below). What follows are: a) guidelines for preparing a Kuali Protocol submission that incorporates deception and/or requires a debriefing process, and b) specific issues that should be addressed in the debriefing form.

1. Use of Debriefing for Deception Studies

Researchers may find that the use of deception, or incomplete disclosure, is a necessary tool for their study. However, the use of such techniques raises special issues that the IRB will review closely. Deception occurs when participants are deliberately given false information about some aspect of the research. Incomplete disclosure occurs when participants are not given information about the real purpose or the nature of the research.

Preparing Your Kuali Protocol Submission for Deception Studies.

A. justifying the use of deception.

An investigator proposing to use deception or incomplete disclosure should justify its use in their IRB protocol submission. Studies utilizing deception should not be submitted for Exempt Review, rather, depending on the nature of the deception the study will be reviewed under either Expedited or Full Board Review processes. Please address the following when preparing your IRB protocol submission:

- In the Study Procedures Section, justify the use of deception and explain why deception is necessary to achieve the goals of the study. Researchers may also provide prior evidence and data that such research methods and use of deception on the proposed subject population does not negatively affect subjects’ attitudes about the research.

- In the Procedures Section, explain the process to debrief participants. Explain when participants will be debriefed, who will debrief them, and how they will be debriefed (online studies may require a different debriefing process than in-lab studies – for more information read the Debriefing Requirements below and/or see our website for guidance of online research ).

- In the Risk Section, explain if use of deception is likely to cause the participant psychological discomfort (i.e., stress, loss of self-esteem, embarrassment) while the deception is taking place. Explain how this risk will be minimized during the experiment and after the experiment is complete (i.e. full debriefing).

- When participants are not given complete information about the study in the informed consent document, it is no longer considered an “informed” consent. In this instance the “informed” consent should merely be labeled a consent document. The IRB must waive certain required elements of the informed consent process (i.e. an explanation of the purpose of the research, a description of the procedures involved, etc.) in such instances. See below for additional information.

- Provide a copy of the debriefing statement(s) that will be given to participants and if applicable, the script that will be used by the researchers to orally explain the study (see below for guidance regarding the debriefing).

B. Debriefing Requirements and Process

The debriefing is an essential part of the consent process and is mandatory when the research study involves deception. The debriefing provides participants with a full explanation of the hypothesis being tested, procedures to deceive participants and the reason(s) why it was necessary to deceive them. It should also include other relevant background information pertaining to the study.

After participants have been debriefed immediately following completion of the study the IRB expects that participants will be given a debriefing statement to take with them. For online studies the debriefing process should occur as soon as a participant has completed the research activity. As an added measure, it may be necessary to send an email out to all participants after the study is completed to ensure that all participants (those that completed and those that may have stopped mid-way) receive a debriefing form. The debriefing statement must be reviewed and approved by the IRB.

The process to debrief participants must be explained in your IRB submission. Your submission must indicate who will debrief participants. The IRB expects that this person is a member of the research team who has knowledge about the research and the deception.

The Debriefing Form should include the following:

- Study title

- Researcher’s name and contact information, if applicable, for follow-up questions.

- Thank participants for taking the time to participate in the study

- Explain what was being studied (i.e., purpose, hypothesis, aim). Use lay terms and avoid use of jargon.

- Explain how participants were deceived

- Explain why deception was necessary in order to carry out the research

- Explain how the results of the deception will be evaluated

- If the study involves use of audio or videotaping an individual participant, give the participant an opportunity to withdraw his/her consent for use of the tapes and, potentially, withdraw from the study all together, after the true purpose of the study is revealed. The IRB suggests that participants be given at least 48 hours to make this decision and provide contact information for whom participants should contact regarding their withdrawal from the study. This option must be given to participants even if they were video or audiotaped during a focus group or during an experiment involving other participants. If a participant decides to withdraw, the PI must use video editing tools to make an individual who withdraws unidentifiable. If tools are not available, the PI cannot use the video or audiotape.

- Provide participants an opportunity to withdraw their consent to participate or to withdraw their data from the study.

- If applicable explain anticipated or observed results so far

- Offer to provide them with the study results

- Provide references/website for further reading on the topic

- Provide a list of resources participants can seek if they become distressed after the study. For a referral list of counseling resources to cite, please see our guidance page.

The IRB has provided a deception research debriefing form template for researchers to use. Please note that the UMass Psychology Department may have their own guidelines and specifications regarding debriefing forms used by researchers in the department. For further information on psychology department specific guidelines please see their website .

2. Use of Debriefing as an Educational Tool

Finally, the IRB suggests that the debriefing also be used as an educational tool, even when the study does not involve the use of deception. Participants should be given a simple, clear and informative explanation of the rationale for the design of the study and the methods used. It should also ask for and answer participant’s questions. The IRB has provided a generic debriefing form template for researchers to use as an educational tool Source material for this policy guidance was provided by the University of Connecticut IRB. The UMass IRB gratefully acknowledges this support.

Last modified:

- Compliance, Human Subjects/IRB

- Research Compliance

Research Guidance

- Online Survey Platforms Guidance

- Online Survey/Survey Research Guidance

Research Form

- Counseling Resources Guidance

- Debriefing Form - Deception

- Debriefing Form - General

©2024 University of Massachusetts Amherst • Site Policies • Site Contact

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Supplements

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 3, Issue 5

- Systematic debriefing after qualitative encounters: an essential analysis step in applied qualitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8634-9283 Shannon A McMahon 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8569-5507 Peter J Winch 2

- 1 Institute of Global Health , Heidelberg University , Heidelberg , Germany

- 2 Department of International Health , Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health , Baltimore , Maryland , USA

- Correspondence to Dr Shannon A McMahon; mcmahon{at}uni-heidelberg.de

Conversations regarding qualitative research and qualitative data analysis in global public health programming often emphasize the product of data collection (audio recordings, transcripts, codebooks and codes), while paying relatively less attention to the process of data collection. In qualitative research, however, the data collector’s skills determine the quality of the data, so understanding data collectors’ strengths and weaknesses as data are being collected allows researchers to enhance both the ability of data collectors and the utility of the data. This paper defines and discusses a process for systematic debriefings. Debriefings entail thorough, goal-oriented discussion of data immediately after it is collected. Debriefings take different forms and fulfill slightly different purposes as data collection progresses. Drawing from examples in our health systems research in Tanzania and Sierra Leone, we elucidate how debriefings have allowed us to: enhance the skills of data collectors; gain immediate insights into the content of data; correct course amid unforeseen changes and challenges in the local context; strengthen the quality and trustworthiness of data in real time; and quickly share emerging data with stakeholders in programmatic, policy and academic spheres. We hope this article provides guidance and stimulates discussion on approaches to qualitative data collection and mechanisms to further outline and refine debriefings in qualitative research.

- health services research

- public health

- qualitative study

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000837

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Summary box

The quality of data in qualitative global health research is stronger when researchers engage local interviewers in a systematic debriefing process.

Understanding interviewers’ strengths and weaknesses in real time allows researchers to enhance interviewer skills and thus data quality.

Through systematic debriefing, researchers can identify and address gaps in the data; capture nuances and other non-verbal information; enhance intellectual partnership within teams; triangulate data; and build theory.

Drawing from our research experiences in Tanzania and Sierra Leone, this paper outlines the process and value of debriefings.

Introduction

A major goal of qualitative research, as applied in global public health, is to give voice to those whose lives are affected by health policies and programs, but whose ability to be heard by those in power and to effectively change health systems and structures is limited. The archetypal means through which such data are collected is the interview, a one-on-one encounter where a researcher and a respondent ‘are talking and asking questions of one another’ usually with the help of an interview guide. 1–3 During the 1–2 hours that a typical interview lasts, a researcher must juggle competing demands: maintaining the interest and openness of the respondent, listening for responses that merit further probing, capturing unspoken cues and gestures, all while simultaneously ensuring that the data collected are relevant to the health issue of interest. 1 4

In the academic ideal, qualitative research is undertaken by those who possess sociocultural understanding of the study context, and are formally trained in qualitative theory, methods and analysis. In global public health research this ideal is often not feasible. Instead, research teams commonly engage locally based qualitative data collection teams who possess essential knowledge in terms of context and language, but who lack formal qualitative training. These teams are routinely trained by an external research lead, an individual who possesses a graduate-level education in public health and qualitative research, but whose contextual or linguistic knowledge is insufficient.

In the ‘local team with outside technical support’ model of qualitative research—henceforth referred to as applied qualitative research or AQR—technical support takes different forms across five overarching phases in the research. See table 1 for a breakdown of tasks for the data collection team and research lead, respectively, during the preparation and execution of data collection, transcription and translation of files, data analysis and study write-up.

- View inline

Organization of qualitative research and qualitative data collection teams

This practice paper focuses on the data collection phase of the table with an emphasis on debriefings, the process where a research lead interviews data collectors soon after a data collection activity. We view debriefings as a necessary element in qualitative research, particularly as the field comes to embrace styles beyond the conventional academic ideal (one person enacting the research process from conception to publication). Furthermore, while we observe a general consensus regarding the rationale and process for undertaking many points in the five-step table ( table 1 ), we see that debriefings receive relatively little attention in the literature and in trainings on qualitative research for public health. When debriefings are mentioned in publications, including our own, 5 6 there is minimal insight into what the debriefing entailed, how it was conducted or how debriefings fundamentally informed the data collection or analysis process. Finally, given that in AQR, much of the data are collected by individuals who have limited training in qualitative research or are more familiar with quantitative survey administration, we urge researchers to more thoughtfully consider discussions on process (ensuring that the data are collected in an iterative i fashion, 7 that the data set is responding to the research question and that the skills of data collectors are strengthened in real time) rather than on outputs (transcription and coding). We now outline what debriefings are, how their purpose shifts in the process of data collection and how debriefings have amplified trustworthiness in our own research. 8 9

What are debriefings?

Debriefings are a discrete moment in the qualitative data collection process where a research manager sits with a data collector (or data collection team) to discuss the tenor, flow and resulting findings from a recently undertaken data collection activity. Ideally conducted after the close of a day’s data collection, debriefings are an essential supplement to qualitative methods such as focus groups, interviews or observations. ii , 10 During debriefings, the research lead takes copious notes. These notes then serve as one component of the full qualitative data set, and methods used to analyze transcripts and observational memos are also applied to debriefing notes.

Debriefings spark immediate reflection on emerging findings; they force data collectors to think through the data that have emerged and to better position findings relative to data collected by fellow data collectors either that same day or to date. Debriefings allow research teams to identify gaps in the data collected and to redirect course—whether refining a line of inquiry, reconceptualizing a research question, opting when or whether to seek out alternative perspectives (such as negative or disconfirming cases), or adding or eliminating a respondent group or research method. Debriefings are the best protection against an unfortunate scenario where, long after the close of data collection, transcripts reveal that the research team did not pursue essential lines of inquiry, or worse, that the data collected will not be able to respond to research aims. For examples of debriefing templates, see online supplementary appendices 1 and 2 .

How should debriefings be done?

Debriefings serve a different purpose as the process of data collection unfolds.

At the outset of data collection, debriefings are one-on-one (the lead researcher interviews the interviewer) and largely procedural in content. In our studies, these early debriefings have been used to learn from the interviewer what could be done to improve the process of data collection. We ask the interviewer questions such as: Is it feasible to find and interview respondents in a private setting (or is the community trailing after the interviewer-respondent pair to listen in on the interview)? Did recording devices work (let’s have a quick listen and upload the recording)? Are the consent forms understandable and did you have them signed or fingerprinted (let’s put them in this waterproof folder)? Are the instruments too short or too long? Do we have concerns about respondents growing tired or bored in an interview and if so, what do you think we should do about this informant fatigue? The earliest debriefings also allow the research lead to gauge the interviewers’ strengths and weaknesses as both interviewers and qualitative researchers. Did the interviewer appear interested, observant and engaged in the data collection activity? Did they probe on valuable lines of inquiry? Did they feel capable of shifting the interview back on track if it digressed in a manner that was not informing the research question? Did they capture non-verbal cues? What would they like from the research lead in terms of troubleshooting through a difficult process? Early debriefings are a means to ensure that the messages conveyed during trainings whether procedural (getting consent) or scientific (probing) are gelling among the data collection team, and to refine or reinforce these messages if they are not.

Interview tips,* a refresher

Adhere to ethical principles

Ask for consent.

Ensure privacy throughout the interview or focus group discussion.

Convey in your actions and your questions that you respect the respondent’s autonomy.

Remove any mystery about the recorder/recording device

Put the recorder within reach of the respondent.

Tell the respondent they can turn it off at will and show them how to do this.

Assure the respondent that only researchers will listen to the recording.

Use all senses to capture details

Recognize pauses long and short.

Capture what is spoken and unspoken (gestures, glances, fidgeting, fear, smiles, sincerity, pride).

Note the smells, sights, the ‘texture’ of the interview.

Keep a conversation comfortable

Start simple.

Ask uncomplicated, unintrusive questions.

Be prepared and open to responding to questions about who you are and why you are there.

Avoid double-barrelled questions.

Know when to pause.

Give time for responses.

Refer back to comments or phrases made by the respondent in the course of the interview.

Follow the golden rules of great interviews

Avoid the temptation to interrupt the respondent.

Use open-ended questions and probes.

Don’t attach your interpretation to a response.

Ask "remarkable questions in an unremarkable tone".*

Do not judge—not with your voice, body or face.

Avoid scientific jargon

Words and phrases like ‘plural health systems’, ‘structural violence’ and ‘stigma’ "sap the power and beauty of plain language".*

Be reflexive, be conscious of your role in this endeavor

Memo how you, as the human being you are, shaped this interview.

End every interview with this question: ‘Is there anything I should have asked you that I did not ask you?’

If the respondent offers some suggestions—ask those questions!

*Informed by Harrington’s 4 ‘Intimate Journalism: The Art and Craft of Reporting Everyday Life’.

As data collection progresses, the nature of the debriefing usually shifts. Procedural questions become less necessary as processes have become routinized. There is also less one-on-one engagement between the research lead and individual interviewers in favor of a debriefing session, which resembles a focus group (with the research lead serving as both a moderator and notetaker). During the debriefing session, each interviewer provides a 2–4 min summary of their interviews or focus groups, with a special interest in describing key points or new findings from their interview. Conversations regarding triangulation (comparing and contrasting findings across data collectors or data collection methods) and topic saturation (the point when similar ideas and insights are heard again and again) typically begin to emerge in this phase as interviewers are encouraged to jump in when they could contextualize, confirm or dispute a piece of information based on their own interview. For both the research lead—and the data collection teams—this is among the most enjoyable and enlightening periods of the research process. Group debriefings prompt new ways of looking at an issue, help the interviewers gauge whether a follow-up interview is necessary, force research teams to think through how to reframe old questions or create new questions for subsequent interviews, and serve as reminders to the team that an interview is a short window into a person’s life during which contextualization of experiences occurs. The debriefing often sparks vibrant conversations among data collection teams about social desirability bias, thoughts on power, autonomy and decision-making within households and communities, and the role of the interviewer and research teams generally in terms of advocacy, human rights and social responsibility. Along with conversations on triangulation, the research team typically begins to discuss reflexivity, questioning how their social standing, personal experiences and inherent biases affect the nature of the interviews.

In the final phase of the debriefing process, the research lead is almost wholly removed from the process. The team nominates one of the data collectors to serve as moderator and another data collector to serve as a notetaker. The language of the group debriefing often switches from English (or other official language in the country) in favor of the local language (or the preferred language of the data collection team and the language of the interviews). During this phase, the research lead begins to build theories, devise an outline of preliminary findings and draw up a list of key local phrasings (emic terms) that may be valuable when presenting the research to stakeholders. In our studies, at this phase of data collection, we begin to develop a slide deck that will be later presented to principal investigators and others on the conclusion of data collection.

The final debriefing occurs on the day after the conclusion of data collection. During this session, the research lead presents the slides of preliminary findings to data collectors. Slides are edited based on feedback, and data collectors are invited to practice and then present portions of the presentation to an audience of academic, ministerial or programmatic peers.

Debriefings in Tanzania

In Tanzania, debriefings informed a fundamental shift in how the research team conceptualized the research question, ‘How do women and their spouses/support networks make decisions regarding where to seek care throughout the maternal care continuum?’ 12 Conducted in 2011, our team initially sought to test a hypothesis that care seeking for childbirth was largely determined by factors such as cost, risk, distance and intrahousehold negotiation. Following debriefings after the earliest interviews, it became apparent that the main issues driving women and their communities away from facilities centered on issues of disrespectful maternity care by providers toward patients. Thinking that these earliest interviews represented an outlier, the data collection continued to rely on the initial data collection instrument, which did not emphasize patient–provider relationships and made no mention of disrespectful or abusive care. As data collection progressed, however, themes related to disrespect continued to emerge. The research lead presented the findings to the study’s principal investigators, who confirmed that this line of inquiry warranted pursuit. The research lead then began a literature review to identify studies that emphasized disrespectful care, and—together with the study team—modified the tools. Had the data collectors not been in regular contact with one another and the research lead, they may have disregarded or downplayed findings related to disrespect, they may have been unsure how to probe about disrespect and abuse, or they may have felt hesitant to undertake a line of inquiry that was not outlined in the tool (and may spark politically contentious debates). Along with allowing the research team to recognize and then triangulate findings related to abuse, debriefings also allowed for immediate comparisons of how male-female pairs describe their role throughout care seeking for childbirth. This immediate comparison (and the incongruences that emerged when comparing accounts across husband-wife pairs) not only generated animated discussions within the team, but also identified another new line of probing (related to births before arrival), and guided decisions regarding whether and when to conduct follow-up interviews. 13

Debriefings in Sierra Leone

In Sierra Leone, debriefings strengthened our study by enhancing the research team’s reflexivity, ability to build rapport and approach to sampling. Data were collected in 2010 with the aim of examining how families understood and manage childhood illnesses. 14 In the course of the earliest debriefings, it became apparent that both researchers and respondents were weary of the data collection endeavor. Data collectors said they were shaken following discussions about child illness and child death with respondents who represented the poorest of the poor. Debriefings presented an opportunity for the team to talk through their anxiety and devise coping strategies collectively. Data collectors also described challenges of building trust with respondents, given strained relations in the wake of the country’s civil war. Several respondents were frightened by the audio recorder, concerned that their voice may be shared with a much wider audience (or used to inflict harm on them or their families). Many community members were also bothered by the presence of outsiders (the data collection team) in their communities; expressing incredulity that outsiders would travel long distances to ask about child health. The data collection team used debriefings to reconsider how to best present the team and explain the purpose of the research to community leaders (in a manner that would ensure all involved that this was a peaceful endeavor, that there was no ill will or underhanded intention of the data collection team toward the community). In terms of qualitative methods specifically, debriefings served as an opportunity to reiterate messages conveyed in the data collector training. Many members of the study team had more experience with quantitative rather than qualitative data collection, so there was a tendency at the outset of data collection to use interview guides as surveys—asking questions in exactly the manner they were written with no probing. Debriefings allowed the research lead to reiterate the open nature of interviewing, and provided a forum for data collectors with more qualitative experience to demonstrate how probing is best done. Finally, debriefings allowed the team to identify respondent types whose insights could inform the research question, but who were not initially a focal group for the study (first wives, mammy queens (female leaders), spiritual healers and traditional birth attendants). 15 These individuals were not initially identified as key informants, but their essential role in deciding whether and when to take a child to a health facility emerged in the earliest interviews and compelled the team to change course in favor of including these individuals.

Systematic debriefings are a necessary complement to more conventional qualitative approaches. Debriefings make it possible to enhance the adaptable, thoughtful and empathetic-yet-questioning nature of qualitative research among data collection teams (thereby improving both the quality of data collected and the capacity of those collecting the data), to correct course in the event of unknowable changes, insights or challenges in a given context, and to quickly share emerging data with stakeholders in programmatic, policy and academic spheres. We have outlined herein a series of steps to conduct debriefings and demonstrated how we have used debriefings in studies across two contexts. We hope this article sparks interest and debate in the literature in terms of how debriefings could be used to improve the quality of qualitative data.

Supplemental material

Acknowledgments.

We are thankful to the qualitative data collection teams we have worked with and debriefed with through the years. In Tanzania: Zeswida Ahmedi, Santiel Mmbaga, Zaina Sheweji, Amrad Charles, Emmanuel Massawe, Maurus Mpunga, Rozalia Mtaturo. In Sierra Leone: Robert Sam-Kpakra, Agnes Farma, Abdul Karim Coteh, Emmanuel Abdulai, Alie Timbo, Mohamed Lamin Sowe, Aminata Alhaji Kamara, Daniella Kopio, Kadie Kandeh, Jestina Lavahun, Jeremiah Sam Kpakra, Lamin Bangura, Isatu Kargbo. We thank Dr. Kerry Scott for her review of this article and for contributing her own debriefing template as an appendix. We thank Prof. Walt Harrington for sharing his wisdom on the art and craft of interviewing. Finally, we acknowledge financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft within the funding programme Open Access Publishing, by the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts and by Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg.

- Harrington W

- Bakshi SS ,

- McMahon S ,

- George A , et al

- McMahon SA ,

- Kennedy CE ,

- Winch PJ , et al

- Campanelli PC ,

- Martin EA ,

- Lincoln YS ,

- George AS ,

- Chebet JJ , et al

- Rao SR , et al

- Yumkella F , et al

↵ i An iterative approach refers to the process of adapting and updating data collection tools (but possibly also methods and sampling) in light of information gleaned from data collected earlier.

↵ ii Beyond qualitative research, debriefings have also been described as a way to examine response error in quantitative surveys, 7 and as a way to interrogate differing assumptions of quantitative and qualitative researchers in a mixed methods study. 10

Handling editor Seye Abimbola

Contributors The two authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

Funding The National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health supported coauthor SAM (Award F31MH095653) throughout her PhD work. The Olympia-Morata-Programm supports her current position as an Assistant Professor at Heidelberg University.

Disclaimer The funders had no role in the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of any funder.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement No additional data are available.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

The Importance of Debriefing in Psychological Research

Debriefing in psychological research plays a crucial role in ensuring ethical practices, participant understanding, and data quality. But what exactly is debriefing, and why is it so important? In this article, we will explore the components of a debriefing session, how it is conducted, and the best practices for ensuring a successful debriefing experience. Whether it’s individual, group, or online debriefing, understanding the ins and outs of this process is essential for any researcher in the field of psychology.

- Debriefing is a crucial aspect of psychological research that involves providing participants with information and addressing any concerns or misunderstandings they may have about the study.

- It is important for ethical reasons, to ensure participant understanding, and to maintain data quality.

- A debriefing session should include explaining the study, clarifying any misunderstandings, disclosing any deception used, and allowing for participant feedback.

- 1 What is Debriefing in Psychological Research?

- 2.1 Ethical Considerations

- 2.2 Participant Understanding

- 2.3 Data Quality

- 3.1 Explanation of the Study

- 3.2 Clarification of Misunderstandings

- 3.3 Deception Disclosure

- 3.4 Participant Feedback

- 4.1 Individual Debriefing

- 4.2 Group Debriefing

- 4.3 Online Debriefing

- 5.1 Plan Ahead

- 5.2 Be Sensitive and Respectful

- 5.3 Use Plain Language

- 5.4 Provide Resources for Further Support

- 6.1 What is the purpose of debriefing in psychological research?

- 6.2 Why is debriefing important in psychological research?

- 6.3 When should debriefing take place in psychological research?

- 6.4 Who is responsible for conducting the debriefing in psychological research?

- 6.5 What information should be included in a debriefing session?

- 6.6 Is debriefing required in all psychological research studies?

What is Debriefing in Psychological Research?

Debriefing in psychological research refers to the process of providing participants with additional information after a study to clarify the purpose, methods, and outcomes of the research.

This post-study interaction plays a crucial role in ensuring that participants have a comprehensive understanding of their involvement. It allows them to gain insight into any aspects of the research that may have been unclear during the study itself. Debriefing not only serves to enhance the transparency of the study process but also helps in upholding ethical standards by preventing the potential harm caused by deception. By disclosing any deception used in the study, debriefing maintains the trust between researchers and participants, crucial for future research collaborations.

Why is Debriefing Important in Psychological Research?

Debriefing holds significant importance in psychological research as it serves to protect participants, uphold ethical standards, and enhance the credibility and validity of study findings.

By engaging in debriefing sessions, researchers can effectively address any potential misinformation that participants may have encountered during the study, thus minimizing the risk of lasting effects on their well-being. The debriefing process allows researchers to gain insights into participants’ memory of the study protocol and interventions, ensuring the accuracy of data collected. This transparent dialogue fosters trust between researchers and participants, ultimately contributing to the overall integrity of the research outcomes.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations play a paramount role in the debriefing process of psychological research, aligning with the guidelines set forth by organizations like the American Psychological Association (APA) to protect participants’ rights and well-being.

One of the fundamental ethical principles in debriefing involves seeking participants’ voluntary participation, ensuring that individuals engage in the research willingly and without any form of coercion. This principle underscores the importance of respecting participants’ autonomy and decision-making abilities.

Another crucial aspect is obtaining informed consent from participants, wherein they are fully briefed about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and their rights before agreeing to take part. This transparency fosters trust between researchers and participants and upholds ethical standards in research practices.

Participant Understanding

Ensuring participant understanding through debriefing is crucial in addressing any misconceptions, clarifying study procedures, and correcting false information that may have been presented during the research process.

Debriefing serves as a vital tool in the research process, as it allows researchers to not only enhance participants’ comprehension of the study but also helps in mitigating the risks associated with deception and false memories.

By providing participants with postwarnings and offering a transparent account of the study’s objectives and methods, debriefing fosters a sense of trust between researchers and participants.

Through debriefing sessions, researchers can identify any ethical concerns that may have arisen during the study and address them promptly, ensuring the integrity and credibility of the research.

Data Quality

Debriefing contributes to ensuring the quality and validity of data collected in psychological research by minimizing the impact of deception, enhancing participant honesty, and evaluating the effectiveness of study interventions.

Debriefing plays a crucial role in reducing biases that may skew research findings. By providing participants with an opportunity to reflect on their experiences and clarify any misunderstandings, debriefing helps in obtaining more accurate data.

Debriefing sessions offer researchers insights into the participants’ perspectives and thought processes, thereby improving the overall quality of information gathered. Through the application of SCOboria social-cognitive dissonance model, debriefing also aids in identifying inconsistencies in participant responses, leading to a deeper understanding of underlying motivations and behaviors.

What are the Components of a Debriefing Session?

A debriefing session typically comprises several key components, including explaining the study objectives, clarifying any misunderstandings, disclosing instances of deception, and obtaining participant feedback.

Explaining the study objectives during the debriefing session serves the crucial role of informing participants of the research goals, methods, and expected outcomes. This not only provides transparency but also ensures that participants are aware of how their involvement contributed to the study.

Clarifications offered in the debriefing session aim to address any confusions or misconceptions that participants may have encountered during the study. By providing clear explanations, researchers can enhance participants’ understanding and prevent the dissemination of inaccurate information.

Disclosing instances of deception is a critical component of ethical research practices. It involves informing participants about any misleading information or manipulation that might have occurred during the study, ensuring their right to informed consent and upholding the integrity of the research.

Obtaining participant feedback at the end of the debriefing session allows researchers to assess the overall experience, address any concerns raised, and gather valuable insights for future studies. Feedback collection is essential for improving research methodologies, participant experiences, and the ethical conduct of psychological research.

Explanation of the Study

Providing a clear and detailed explanation of the study during debriefing is essential to address any potential misinformation, ensure participant comprehension, and maintain research integrity.

Debriefing sessions offer researchers an invaluable opportunity to revisit the study with participants, rectify any misunderstandings or false information that may have arisen during the research process. Clarifying research procedures not only helps in enhancing the validity of the findings but also ensures that the participants have a comprehensive understanding of the study’s objectives and their role in it. This personalized interaction aids in mitigating any memory biases that can affect the recall of various aspects of the study, ultimately improving the overall effect of the research outcomes.

Clarification of Misunderstandings

Clarifying any misunderstandings that participants may have encountered during the research process is a critical aspect of debriefing, ensuring that accurate information is conveyed and understood effectively.

Addressing misunderstandings in debriefing plays a pivotal role in enhancing communication between researchers and participants. By fostering an open dialogue to clear up any confusion that may have arisen, postwarnings and feedback can be better understood and utilized, leading to increased effectiveness of the overall research process. Resolving conflicts that stem from misunderstandings can promote a more positive and productive research environment, allowing for smoother collaboration between all parties involved. By tackling these misconceptions head-on, trust between researchers and participants is strengthened, creating a foundation of transparency that enhances memory retention of the research experience.

Deception Disclosure

Disclosing instances of deception used in the study is a crucial ethical obligation during debriefing sessions, aiming to maintain participant trust, minimize potential harm, and uphold research integrity.

Ensuring transparency in debriefing not only fosters trust but also protects the participants from undue distress. Ethical guidelines dictate that researchers must reveal any deceptive practices employed, explain their purpose, and address any concerns raised by the participants.

Participant well-being is of paramount importance, and disclosure allows individuals to comprehend the study’s full scope and make informed decisions regarding their involvement.

Participant Feedback

Gathering participant feedback in debriefing sessions provides valuable insights into the participant experience, helps evaluate the study’s impact, and offers opportunities for further information exchange.

During debriefing sessions, the feedback collected acts as a mirror reflecting the effect of the research methods on the participants, shedding light on their perceptions and reactions. Utilizing this feedback enhances the quality of research practices by addressing any discrepancies or areas for improvement that might have gone unnoticed. Incorporating participant perspectives fosters a culture of transparency and authenticity, reducing the risk of misinformation or false information dissemination. This open communication channel not only benefits the current study but also contributes to enhancing future research endeavors through continuous feedback loops.

How is Debriefing Conducted in Psychological Research?

Debriefing in psychological research can be conducted through various methods, including individual sessions, group debriefings, and online debriefing platforms, each tailored to the study’s requirements and participant preferences.

When considering individual debriefing sessions, researchers can provide personalized attention to participants, allowing for in-depth discussions and addressing specific concerns. This method often enhances rapport between the researcher and the participant, fostering a deeper understanding of the study’s impact on the individual.

On the contrary, group debriefings offer the advantage of promoting peer interaction and shared insights among participants, enabling them to collectively reflect on their experiences and findings.

Individual Debriefing

Individual debriefing sessions offer personalized interactions between researchers and participants, allowing for tailored postwarnings, detailed explanations, and focused discussions on the study outcomes.

Through these one-on-one sessions, participants have the opportunity to delve deeply into their experiences and insights, fostering a sense of trust and confidentiality. This individualized approach not only ensures that each participant’s perspective is thoroughly explored, but also allows researchers to address any unique concerns or questions that may arise. By following the SCOboria social-cognitive dissonance model, debriefing sessions can provide a comprehensive framework for understanding participants’ responses and behaviors, leading to richer data interpretation and analysis.

Group Debriefing

Group debriefing sessions facilitate collective discussions among participants, encourage peer interactions, and promote a shared understanding of the study’s key findings and implications.

During these sessions, individuals have the opportunity to engage in in-depth conversations where different viewpoints and interpretations come to light, enhancing the overall depth of understanding within the group. The dynamic exchange of ideas and perspectives creates a lively setting that fosters critical thinking and analytical skills development. The social dynamics at play during these sessions help build a sense of camaraderie and support among participants, leading to a collaborative learning environment where everyone contributes to the exploration of information and ethics.

Online Debriefing

Online debriefing platforms offer convenient and accessible avenues for participants to engage with study information, reflect on their experiences, and provide feedback in a digital environment that may impact memory retention.

One major advantage of using online debriefing methods is the ease of access they provide. Participants can conveniently access and engage with debriefing materials from the comfort of their own homes or any location with internet connectivity. This enhances participant comfort by eliminating the need to travel to a physical location for debriefing sessions, making it more convenient for busy individuals. The digital format allows for flexibility in timing, enabling participants to review the information at a time that suits them best.

What are the Best Practices for Conducting a Debriefing Session?

Effective debriefing sessions in psychological research require meticulous planning, sensitivity towards participants’ experiences, clear communication using plain language, and provision of resources for further support.

Debriefing sessions should be carefully structured, considering the emotional impact on participants and offering postwarnings to safeguard against distress. The facilitator’s empathy plays a crucial role in creating a safe space for open dialogue and reflection. Ensuring transparency and honesty throughout the debriefing process is vital in combating the spread of false information or misinterpretations. Providing follow-up resources, such as contact details for counseling services, can aid participants in processing the experience and addressing any lingering concerns.

Advance planning is crucial for debriefing sessions in psychological research, ensuring that the process is structured, comprehensive, and tailored to address the study’s objectives effectively.

During debriefing sessions, it is essential to have a well-defined strategy in place to guide the process seamlessly. Structured approaches help in organizing the information gathered, analyzing it efficiently, and drawing meaningful insights. Goal alignment is another key aspect that ensures that the debriefing session remains focused on the objectives of the study, enabling researchers to extract valuable data and reflections from the participants. Efficient communication during debriefing enhances the quality of information exchange, leading to more profound understanding and insights for all involved parties.

Be Sensitive and Respectful

Maintaining sensitivity and respect towards participants during debriefing sessions is essential to foster trust, uphold ethical standards, and ensure a supportive environment for discussing research experiences.

Building rapport with participants through empathetic communication aids in establishing a foundation of trust that is fundamental to ethical debriefing practices. By acknowledging the valuable contributions of participants, researchers demonstrate respect for their time, perspectives, and willingness to engage in meaningful dialogue. This mutual respect paves the way for an open and honest exchange of information within a safe space where individuals feel heard and valued. Upholding these principles not only enhances the quality of research outcomes but also prioritizes the well-being and dignity of all involved.

Use Plain Language

Employing clear and straightforward language in debriefing sessions aids participant comprehension, minimizes confusion, and enhances memory retention of key study information and outcomes.

Using plain language in debriefing communications is crucial not only for ensuring that participants grasp the study details effectively but also for reducing the risk of creating false memories due to misinterpretations. By communicating in a clear and simple manner, researchers can significantly improve the accuracy and reliability of the information retained by participants. This approach promotes transparency, trust, and ethical conduct in research, fostering a more conducive environment for meaningful data collection and analysis.

Provide Resources for Further Support

Offering resources for further support post-debriefing is essential in ensuring participants have access to additional information, guidance, and assistance to address any lingering questions or concerns arising from the study.

These resources play a critical role in facilitating the understanding of the research process and outcomes, especially in the context of psychological research. By providing avenues for participants to delve deeper into the implications of the study, researchers contribute to enhancing the overall impact and effectiveness of their work.

Post-debriefing resources help mitigate the potential effects of cognitive dissonance that participants may experience, aligning with the SCOboria social-cognitive dissonance model. Participants can utilize these resources to gain clarity, seek reassurance, and even access professional support when needed, fostering a sense of ongoing support and connection beyond the study’s conclusion.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the purpose of debriefing in psychological research.

Debriefing in psychological research serves to inform participants about the true nature and purpose of the study, as well as to address any potential ethical concerns.

Why is debriefing important in psychological research?

Debriefing allows participants to fully understand the procedures and findings of the study, promotes transparency, and helps to build trust between researchers and participants.

When should debriefing take place in psychological research?

Debriefing should take place as soon as possible after the study is completed, and before participants leave the research setting. This ensures that the information is fresh in their minds and allows for immediate clarification of any questions or concerns.

Who is responsible for conducting the debriefing in psychological research?

The researcher or someone trained and authorized by the researcher is responsible for conducting the debriefing. This ensures that the information is accurately and appropriately conveyed to participants.

What information should be included in a debriefing session?

A debriefing session should include an explanation of the true purpose of the study, a summary of the results, and an opportunity for participants to ask questions or provide feedback. It should also include information on how the data will be used and how to contact the researcher with any further concerns.

Is debriefing required in all psychological research studies?

Yes, debriefing is considered an essential part of ethical research and is required in all psychological studies. Even if the study involves minimal risk, debriefing still allows for the opportunity to address any potential concerns or misunderstandings from participants.

Dr. Henry Foster is a neuropsychologist with a focus on cognitive disorders and brain rehabilitation. His clinical work involves assessing and treating individuals with brain injuries and neurodegenerative diseases. Through his writing, Dr. Foster shares insights into the brain’s ability to heal and adapt, offering hope and practical advice for patients and families navigating the challenges of cognitive impairments.

Similar Posts

The Psychological Phenomenon of Loss Aversion: Insights and Implications

The article was last updated by Alicia Rhodes on February 8, 2024. Have you ever found yourself making decisions based on avoiding losses rather than…

Understanding the Concept of Statistical Significance in Psychology

The article was last updated by Vanessa Patel on February 8, 2024. Statistical significance is a crucial concept in psychology research, determining whether the results…

Exploring the Salary Potential for Psychology Majors: A Comprehensive Guide

The article was last updated by Ethan Clarke on February 1, 2024. Are you considering a career in psychology but unsure about the salary potential?…

Signal Detection Theory in Psychology: Explanation and Applications

The article was last updated by Sofia Alvarez on February 8, 2024. Signal Detection Theory is a fundamental concept in psychology that aims to understand…

The Role of Psychology in Social Science

The article was last updated by Samantha Choi on February 8, 2024. Have you ever wondered about the intricate relationship between psychology and social science?…

Key Features that Distinguish Psychology as a Field

The article was last updated by Emily (Editor) on February 21, 2024. Psychology is a fascinating field that delves into the study of human behavior…

Debriefing in Psychology: Sample Studies & Protocol

Debriefing refers to the procedure for revealing the true purpose of a psychological study to a research participant at the conclusion of a research session.

In order to examine authentic behavior, it is sometimes necessary to tell participants that the study is about one subject, when in fact it is about something else. This is called deception.

If researchers explained the true purpose of a study, then some participants will act in a way that undermines the study’s validity. For example, participants may engage in impression management strategies to make themselves appear in a favorable light.

Thus, the need for deception.

Ethics of Debriefing

Elements of deception must be approved before researchers begin data collection.

This is accomplished through a university Institutional Review Board (IRB), which is responsible for overseeing all research involving human participants.

The researchers fill out extensive forms, thoroughly explain the rationale for deception and the debriefing protocol, and supply a copy of the Debriefing Form.

The American Psychological Association states that psychologists should explain:

“…the nature, results, and conclusions of the research … [and] take reasonable steps to correct any misconceptions that participants may have” (p. 1070).

If the IRB approves the study, data collection can commence. If the study is not approved, researchers may alter their procedures and resubmit.

The Debriefing Protocol and Form

Every debriefing includes a set procedure that must be approved by the IRB. There are many required components, plus a Debriefing Form, which may or may not have to be signed by each participant, depending on the university.

The standard components of the form include:

- Thanking the participant for their time and involvement.

- Recapping the tasks and stated purpose of the study.

- Clarification of the study’s use of deception and revealing its true purpose.

- Stating that the participant can withdraw their data, without penalty.

- A request asking the participant’s permission to use their data.

- Provide contact information for university counselling services.

- Provide contact information of the researcher.

- Explain that they may receive a full copy of the research paper when completed.

- Provide contact information for the university’s Institutional Review Board.

- Provide two references of similar research.

Click here for the debriefing template at Pepperdine University, or here for a sample debriefing statement.

About The Institutional Review Board (IRB)

The IRB is an independent entity established to protect the rights of human research participants. Any organization in the United States that receives federal funding must have an IRB that is registered with the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) and complies with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Protection of Human Subjects regulations, 45 CFR part 46 .

The IRB is comprised of research peers at the university where the research will be conducted.

Researchers submit their application for approval to the IRB before commencing data collection.

The IRB has the authority to:

- Approve, disapprove, or terminate a study

- Require researchers modify procedures

- Require additional information be provided to participants on the Informed Consent Form ( basic elements and sample )

Typically, the IRB will meet once a month to review applications and discuss relevant issues. Members will have already received copies of submitted applications prior to the meeting. If approved, official notification will be delivered to the principal investigator.

If there are any substantial changes in the research protocol, the IRB must be informed and an amended application may be required.

Infamous Studies Demonstrating the Need for Quality Debriefing

1. the milgram shock study.

In 1961, Dr. Stanley Milgram of Yale university conducted one of the most influential, and controversial, experiments in psychology.

Milgram’s studied deceived participants by telling them the study was about punishment and learning. The true purpose was to investigate the power of authority.

During the study, real participants were instructed to administer increasingly high levels of shock to another participant (actually an actor). As the actor began to object and expressed severe pain, the researcher insisted they continue administering shock.

Video recordings of the participants clearly showed they were under severe duress.

The study was heavily criticized for both the use of deception and psychological duress endured by participants.

According to Harris (1988), Milgram:

“…explained that he had arranged a ‘friendly reconciliation’ between each subject and the accomplice…convincingly explained the importance of research on obedience…used both an interview and follow-up questionnaire to verify subjects’ positive opinion of the research” (pp. 196-197).

Milgram’s study became a key impetus to the formalization of ethical standards in psychological research .

2. Bystander Intervention

In the 1960’s, there were no formalized procedures regarding the use of deception or debriefing. Researchers were entrusted to engage in ethical behavior in the name of professionalism .

The mindset regarding deception and debriefing is illustrated in the famous study by Darley and Latané (1968) on “ the bystander effect .”

The study examined how the number of people witnessing a person in distress would influence their attempt to intervene.

Of course, if researchers explained this purpose at the beginning of the study, the results would hardly be valid.

Here is the deception:

“It was explained to him that he was to take part in a discussion about personal problems associated with college life and that the discussion would be held over the intercom system, rather than face-to-face, in order to avoid embarrassment by preserving the anonymity of the subjects” (p. 378).

At the end of each session, debriefing occurred:

“As soon as the subject reported the emergency, or after 6 minutes had elapsed, the experimental assistant disclosed the true nature of the experiment, and dealt with any emotions aroused in the subject” (p. 379).

The debriefing procedure was quite minimal: no forms to respond to, no permissions requested, no contact information provided.

Debriefing Effects

Research on misinformation often requires deception. Debriefing usually involves a detailed explanation regarding the dangers of misinformation. Does that help? Do participants then become less susceptible to misinformation?

Greenspan and Loftus (2022) had participants watch a video that depicted a crime. Leading questions were used to suggest that the victim’s jacket was gray, even though it was red.

The leading questions had their usual effect. A majority of participants recalled the jacket as gray.

Then, two types of debriefings were administered.

In the control condition, participants were thanked and reminded about Session 2. In the misinformation condition, the role of misinformation in the study was revealed and participants were reminded about Session 2.

The results of Session 2 showed:

“…that a misinformation effect can persist after debriefing. Five days after debriefing, the majority of participants who endorsed the misinformation at Session 1 continued to do so postdebriefing” (p. 706).

So, even though debriefing informed participants about the leading questions in the study, the misinformation effect persisted.

Debriefing Examples

- At the end of the experimental session, the experimenter thanked the participants for their time, clarified the use of deception and rationale, and distributed the Debriefing Forms.

- After being told the study was about memory and commercials, at the end of the study, participants were told that the study was actually about the effects of physically attractive actors on consumer attitudes.

- Since the participant seemed to be in a slightly depressed mood after receiving negative feedback in the low-self-esteem condition, the experimenter highlighted the contact information for the university’s counselling center on the Debriefing Form.

- Participants were initially told the study was about IQ tests. After the study, participants were told the study was really about the effects of different aromas on cognitive performance, which explains the presence of an essential oils diffuser in the room.

- At the end of the data-collection session, one participant indicated they did not want their data to be used. So, the experimenter immediately deleted their survey responses from the computer.

- After participants completed a job simulation, the experimenter collecting the data explained that the real purpose of the study was to examine the types of functional statements made during group decision-making.

- One participant did not appreciate being “lied to” during the study. The experimenter did their best to explain the rationale for deception and then highlighted the IRB’s contact information on the Debriefing Form.

- The experimenter explained to participants that the study was about mate selection. So, they would be rating photos of faces in terms of physical attractiveness. However, the study was actually designed to correlate facial markers of testosterone and perceived leadership ability.

- During debriefing, the experimenter answered all questions the participant had about the study and asked for permission to use their data.

- After collecting observational data during home visits, the researchers explained to parents that the study wasn’t actually about how children play. The study was really about types of parental discipline and children’s socio-emotional development.

Debriefing occurs at the end of each participant’s involvement in a study. There are numerous key components of the debriefing session, including clarifying any elements of deception and allowing participants to have their data deleted.

The purpose of debriefing is to ensure that participants are treated fairly, with dignity, and ensure they experience no enduring ill effects. The APA (2002) states that if researchers are “aware that research procedures have harmed a participant, they take reasonable steps to minimize the harm” (p. 1070).

There was a time in psychological research when debriefing was not required. However, historical events and the famous Milgram study sparked discussion and eventually a formal protocol was established.

Today, all studies must be pre-approved by an IRB before data is collected.

American Psychological Association. (2002). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist, 57(12), 1060–1073. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.12.1060

Arslan, R. (2018). A Review on Ethical Issues and Rules in Psychological Assessment. Journal of Family, Counseling and Education, 3, 17-29. https://doi.org/10.32568/jfce.310629

Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4), 377-383.

Greenspan, R. L., & Loftus, E. F. (2022). What happens after debriefing? The effectiveness and benefits of postexperimental debriefing. Memory & Cognition, 50(4), 696-709.

Harris, B. (1988). Key words: A history of debriefing in social psychology. In J. Morawski (Ed.), The rise of experimentation in American psychology (pp. 188-212). New York: Oxford University Press.

Milgram, S. (1965). Some conditions of obedience and disobedience to authority. Human Relations, 18(1), 57–76.

The British Psychological Society. (2010). Code of Human Research Ethics. www.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/code_of_human_research_ethics.pdf

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Debriefing is a process for telling participants all the information related to the study that was initially withheld. Debriefing may be done in-person, but is more often a document provided to subjects at the completion of the study activities.

There are two conditions that require debriefing

- A study involves deception

Debriefing is a process for telling participants all the information related to the study that was initially withheld. Debriefing for participants who were deceived includes a description of the deception and an explanation about why it was necessary. The discussion should presented in lay language and should be sufficiently detailed that participants will understand how and why they were deceived. If the study included multiple deceptions, each should be addressed.

Debriefing may be done in-person, but is more often a document provided to subjects at the completion of the study activities.

If participants were filmed without their knowledge, they must be given the option to ask that the researchers do not use the film. Participants may want to see the video in order to decide if it may be used for research purposes.

Delayed debriefing is an option if participants are part of a group that may share information about their experience in the research.

If researchers will use a delayed debriefing, the consent form must state additional information will be available at the study and participants’ contact information should be collected. The contact information should not be linked to the study data.

Sample Debriefing for Deception

- The study uses the Psychology and Neuroscience Subject Pool

Participation as research subjects is intended to function as a teaching tool. Therefore, debriefing must be provided that explains the purpose of the research and how research methods and instruments were designed to answer the research question.

Sample Debriefing for Subject Pool Study

Debriefing: A Practical Guide

- First Online: 01 October 2023

Cite this chapter

- David Crookall ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8024-0754 3

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

204 Accesses

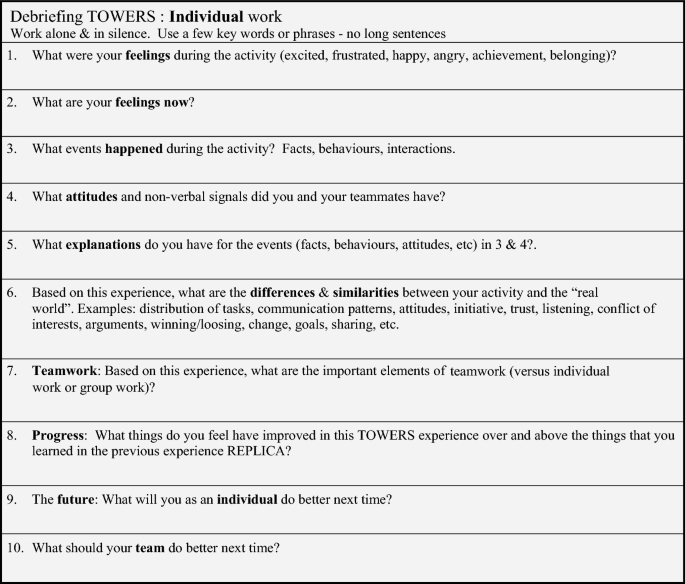

Debriefing is the most important part of a simulation. That is why this is a key chapter in this book. The chapter contains several sections, each one offering insights, guidance and stories for debriefers. The central sections of this chapter look at various aspects of debriefing, such as what it is and when, why and how we should conduct it. Each section looks at debriefing, not so much from a theoretical stance, but more from a practical, down-to-earth perspective. The appendix contains a number of ready-to-use examples of materials to use for debriefing and also suggestions of courses or curriculums that use larger simulation and thus that must employ and deploy debriefing in a judiciously managed fashion. Having developed and conducted debriefs and trained trainers in debriefing for many years, I have written this chapter from a personal angle, sometimes offering short vignettes or stories of my own experience.

Dedication This chapter is dedicated to a dear friend, the late Dr. Ajarn Songsri Soranastaporn. Ajarn Songsri was the initiator (with me) and Secretary General of ThaiSim, the Thailand Simulation and Gaming Association. For over 10 years, she and her colleagues organized the International ThaiSim Conferences (including an ISAGA conference), probably the most wonderful and memorable simulation/gaming meetings anywhere in the world. She helped with the journal S&G , was a major force in Thailand for educational simulation and applied linguistics and was dearly loved by all her colleagues and students. In true Buddhist tradition, she gave so much and asked for so little. We might feel closer to Ajarn Songsri and understand her passing better by reading Upasen and Thanasilp ( 2020 ).

Simulation without including adequate debriefing is ineffective and even unethical . (Willy Kriz, 2008 ) The debriefing is where the ‘magic’ happens . (Dick Duke, 2011 )

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Essentials of Debriefing in Simulation-Based Education

Debrief it all: a tool for inclusion of Safety-II

Debriefing Using a Structured and Supported Approach

Bibliography.

Not all the references below have been cited in the chapter. Some additional references have been inserted below to help you pursue this area further. It is also likely that some references that should have been mentioned are missing. For the missing ones please send me a link to an open access source, and failing that, to send me the missing document (pdf preferred).

Google Scholar

Aarkrog, V. (2019). ‘The mannequin is more lifelike’: The significance of fidelity for students’ learning in simulation-based training in the social- and healthcare programmes. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3384/njvet.2242-458X.19921

Abulebda, K., Auerbach, M., & Limaiem, F. (2021). Debriefing techniques utilized in medical simulation. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546660/

Airbus. (n.d.). Airbus Training Center Europe celebrates the certification of a new A350 Full Flight Simulator | Airbus Aircraft . Retrieved 4 December 2021, from https://aircraft.airbus.com/en/newsroom/news/2021-10-airbus-training-center-europe-celebrates-the-certification-of-a-new-a350-full

Alexander, R. (2018a). Developing dialogic teaching: Genesis, process, trial. Research Papers in Education, 33 (5), 561–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2018.1481140

Alexander, R. (2018b). Towards dialogic teaching: Rethinking classroom talk . Dialogos.

Alexander, R. J. (2020). A dialogic teaching companion . Routledge.

Alklind Taylor, A.-S., Backlund, P., Rambusch, J., Linderoth, J., Forskningscentrum für Informationsteknologi, & Interaction Lab. (2014). Facilitation matters: A framework for instructor-led serious gaming. University of Skovde.

Angelini, M. L. (2021). Learning through simulations: Ideas for educational practitioners. SpringerBriefs in Education. In SpringerBriefs in Education . Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65540-2

Angelini, M. L. (2022). Simulation in teacher education . Springer.

Armstrong, T. (2009). Multiple intelligences in the classroom (3rd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Baker, A. C., Jensen, P. J., & Kolb, D. A. (1997). In conversation: Transforming experience into learning. Simulation & Gaming, 28 (1), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878197281002

Article Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory . Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1995). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory . Prenctice Hall.

Bandura, A. (2012). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control . Freeman.

Baudelaire, C. (1857). Les Fleurs du mal . Poulet-Malassis et De Broise; Éditions Gallimard.

Becu, N. (2020). Les courants d’influence et la pratique de la simulation participative: Contours, design et contributions aux changements sociétaux et organisationnels dans les territoires . La Rochelle Université.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge . Penguin.

Blair, B., Müller, M., Palerme, C., Blair, R., Crookall, D., Knol-Kauffman, M., & Lamers, M. (2022). Coproducing sea ice predictions with stakeholders using simulation. Weather, Climate, and Society, 14 (2), 399–413. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-21-0048.1

Bloom, B. S., Krathwohl, D. R., & Masia, B. B. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals . David McKay.

Bodein, I., Forestier, M., Le Borgne, C., Lefebvre, J.-M., Pinçon, C., Garat, A., Standaert, A., & Décaudin, B. (2023). Formation des étudiants en pharmacie d’officine et en médecine générale à la communication interprofessionnelle: Évaluation d’un programme de simulation. Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises, 81 (2), 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharma.2022.06.008

Bommel, P. (2020). Participatory modelling and interactive simulation to support the management of the commons . University of Montpellier. http://agents.cirad.fr/pjjimg/[email protected]/HDR_dissertation_EN.pdf

Bredemeier, M. E., & Greenblat, C. S. (1981). The educational effectiveness of simulation games: A synthesis of findings. Simulation & Games, 12 (3), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/104687818101200304

Brett-Fleegler, M., Rudolph, J., Eppich, W., Monuteaux, M., Fleegler, E., Cheng, A., & Simon, R. (2012). Debriefing assessment for simulation in healthcare: Development and psychometric properties. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 7 (5), 288–294. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e3182620228

Bruner, J. S. (1977). The process of education . Harvard University Press. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10313833

Buljac-Samardzic, M., Doekhie, K. D., & van Wijngaarden, J. D. H. (2020). Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: A systematic review of the past decade. Human Resources for Health, 18 (1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-019-0411-3