- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Real Reason Uber Is Giving Up in China

- William C. Kirby

It’s regulation, not competition.

Last September some of the world’s foremost technology industry leaders met in Seattle with Xi Jinping, president of China. In a group photograph, 30 CEOs with a combined market capitalization of $2.5 trillion smiled for the camera alongside the Chinese leader. They included Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, and leaders of some of the most prominent “sharing economy” companies: Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky and Didi Chuxing CEO Cheng Wei, the head of China’s leading taxi and private car hailing app. Conspicuously absent from the photo was Uber’s CEO , Travis Kalanick.

- WK William C. Kirby is the Spangler Family Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and the T. M. Chang Professor of China Studies at Harvard University. His latest book, co-authored with Regina Abrami and F. Warren McFarlan, is Can China Lead? (HBR Press, 2014). He is the co-author, with Joycelyn Eby, Adam Mitchell, and Shuang Lu, of the case study, “ Uber in China: Driving in the Gray Zone ” (2016).

Partner Center

This is why Uber failed in China

When asked about Uber's attempt to dominate in the vast market that is China, the CEO of homegrown ride-sharing company Didi Chuxing, Jean Liu, said it was "cute."

Man was she right.

On Monday, Uber fled China. It surrendered a massive market and sold its $8 billion business to Liu's Didi less than a week after Chinese regulators legalized ride sharing in any capacity.

One would think that after three years of slugging it out for the hearts of Chinese consumers, regulatory loosening would be the time to ramp up efforts, regardless of the fact that Didi had 80% of the country's market share.

The opportunity, after all, was well understood by investors. As billionaire hedge fund manager Dan Loeb put it in his second-quarter letter to investors:

"While ride‐sharing is rapidly gaining traction in numerous markets around the world, we view China as a particularly attractive market for ride‐sharing expansion thanks to several differentiating factors. China has among the highest population density levels of any large country and is home to nine of the world's 30 largest cities. Ride‐sharing platforms tend to work best in densely populated cities because they provide a liquid supply of available drivers, consistent rider demand to attract drivers, and correspondingly short waiting times.

"China also has a relatively low level of car ownership, with only 130 vehicles per thousand people (vs 800 in the US and 500‐700 in Western Europe). Given chronic traffic in China’s cities and the lack of available real estate for parking, a mainstream culture of private car ownership in China has not yet developed and most urban residents still rely heavily on public transportation."

Of course, he explained this while he was telling his investors about a new investment in Didi, not Uber. And it only takes a basic understanding of what's going on in China right now to understand his choice.

Capitalism with Xi Jinping characteristics

From the moment he took to the international stage, Xi Jinping was a mystery. However, for the most part, we in the West thought he would be much like his predecessors — open to foreign business and ready to solidify China's central place in the global order of capitalism.

Xi suggested as much in a speech in Washington, DC, after taking power in 2013.

"China will never close its open door to the outside world. Opening up is a basic state policy of China. Its policies that attract foreign investment will not change, nor will its pledge to protect legitimate rights and interests of foreign investors in China, and to improve its services for foreign companies operating in China," Xi said.

"We respect the international business norms and practice of nondiscrimination, observe the … principle of national treatment commitment, treat all market players — including foreign-invested companies — fairly, and encourage transnational corporations to engage in all forms of cooperation with Chinese companies."

You see, we had reason to believe that China's openness would continue into the next administration.

Man were we wrong. Xi has turned out to be a new kind of Chinese leader — an autocrat and an extreme nationalist, in a way that extends past the Chinese military or even domestic politics. These features extend to Chinese business.

The US-China Business Council was warning companies that the Chinese government was favoring domestic companies as early as 2011 . Under Xi, this only got worse.

In an August 2015 survey , the American Chamber of Commerce in China found that only 25% of its members in the service sector were optimistic about the regulatory environment in China. The service sector, of course, includes banks, restaurants, and companies like Uber.

The survey found that respondents were worried about the Chinese government restricting key data-gathering efforts for foreign companies, a lack of information about the rules of engagement or regulatory procedures in the event of disputes, and an overly broad definition of national security that applied to activities American businesspeople never dreamed of.

"Numerous service industries in China face an uneven playing field due to government support for state-owned enterprises and designated oligopolies within their sectors. Such government preferences, and the benefits the state-owned enterprises receive, restrict both foreign and domestic companies' ability to operate in the market," it said.

Related stories

This might not just be a Xi thing, either. The Chinese economy is going through the difficult transition of moving from an economy based on industrial manufacturing and foreign investment to one based on the services sector and domestic consumption.

One cannot be open and protectionist at the same time, but now that industrial manufacturing is already in "hard landing" mode, the government has to do everything it can to boost the services sector. The economy is slowing, and the much-vaunted Chinese Dream — the dream of economic progress that has consistently trumped the nightmare of political repression — is at risk.

Tell me, who do you think you are?

Enter Uber, the Silicon Valley dynamo with a massive stockpile of private money and a mission of world domination. For three years it toiled in China, trying to gain market share in a fierce battle with Didi. Or rather, it looked fierce from here in the US. Again, apparently Didi thought the whole thing was "cute."

And that's likely because Didi understood the reality I just outlined above. It is very telling that Uber did not.

"We were a young American business entering a country where most US internet companies had failed to crack the code,” Uber CEO Travis Kalanick said on Monday.

Many American companies are finding this code confusing, simple though it may be. Meanwhile, Uber has made a habit of flouting rules and norms. It has run into multiple labor lawsuits here in America for misclassifying its drivers as independent contractors rather than employees. It was chased out of Hungary .

And then there's this very telling anecdote from former Fortress Investments President Michael Novogratz, who met with the former CFO of Uber, Brent Callinicos.

Callinicos told Novogratz that Uber drivers return between 20% and 25% of the fares they collect, but that in the future, Uber could easily raise that rate to between 25% and 30%. This would drastically improve Uber's profit margin. Novogratz responded quizzically.

"You've got happy employees, you've got happy customers, you've got happy shareholders. The holy triumvirate are all really excited about your company. Why are you going to risk that and push the employee's salary down 5%?"

Callinicos simply responded, "because we can."

In China, it seems, you can't.

When the Chinese government legalized ride sharing, it included provisions making it illegal to engage in a practice Uber has become famous for — selling rides below cost to push out competitors. It played this game with Didi, and Liu made fun of Uber for it.

"Have you seen in other places market leaders buy market share?" Liu said . "Normally it's always the smaller player with smaller scale, lower efficiency, and in most cases worse service that needs to buy market share to heavily subsidize."

Dodging bullets

All of this said, it may very well be that Uber dodged a bullet in China. The US internet companies that are getting left behind as Chinese competitors take share may not be jealous for long. The government has floated the idea of taking a 1% stake in giants like Tencent and Baidu to control what's on the web.

Of course, there's a darker way to look at that, and Wall Street's all over it. As the Chinese economy slows and its debt-to-GDP ratio (currently sitting at around 285%) grows, the government is going to need places to find cash to keep money flowing through already quasi-state-owned banks.

It already announced that it would relax regulation in order to allow debt-to-equity swaps between banks and indebted companies. But where does it stop?

At a certain point, the entire economy starts to congeal, and then you have a "Japanification" scenario. All of a sudden the corporate sector is the government and the government is the corporate sector, and any cash lying around has to do its part to keep things going.

Uber, you didn't want to be involved in that mess anyway.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Insider.

Watch: WATCH: Executives from Morgan Stanley, Citi, and Barclays explain how they encourage innovation within big, unwieldy banks

- Main content

7 lessons to learn from Uber’s failure in China: winning business model case study

When it comes to building a new software product or expanding to new markets, nothing is as important as nailing the business model . Uber’s failure to conquer the market in China and merging with its competitor DiDi Chuxing is living proof of this statement.

Uber and DiDi, two of the leading ride-hailing services in the world, entered the Chinese market in 2014 and competed fiercely for market share. Despite investing more than USD 1 billion a year, Uber was unable to overcome DiDi's aggressive investment and marketing strategies and consequently merged with DiDi in 2016. But were these two factors the only reason for Uber’s failure? Not exactly. A comparison of the business models of Uber and DiDi reveals valuable insights as to how to approach the process and what details should be given utmost attention.

Value propositions of Uber and DiDi

In a recent study published in the Journal of Open Innovation, we find that each company adopted different approaches to the market, with Uber focusing on global expansion and DiDi focusing on local markets. The below canvas models illustrate these and other differences between each company’s competitive processes and strategic approaches. Such canvas models, typically developed during product workshops , are crucial for planning the development of any software tool, with its service offering as well as marketing strategy.

Both Uber and DiDi operate in the same, two-sided market in which drivers are being connected with customers. Uber has positioned itself as a luxury brand with a variety of high-end vehicles and services, while DiDi has chosen to focus on low-cost services that substitute for taxis. Both have sought to expand their services, but chose two different methods for expansion. What are the reasons for DiDi’s success and Uber’s failure? Here are 7 lessons we can learn by examining this specific case in detail.

Lesson 1: Brand power doesn’t matter when expanding to new markets

Uber was the first successful platform that built and launched the ride-hailing service and has a strong global brand power. However, this did not translate to the Chinese market. Despite 77.2% of passengers being aware of the Uber brand, DiDi had higher user recognition and was more often recommended via word-of-mouth, as it offered services that were more relevant to its users.

Lesson 2: Coverage matters when you’re building a location-based, on-demand service

DiDi took advantage of its local position and ties to domestic partners, which allowed it to quickly establish a competitive stance in the Chinese ride-hailing market. Although Uber was able to maintain a steady market share in some segments, DiDi was able to achieve higher market penetration across more service categories. Uber focused on China's largest cities, operating in fewer than 40 cities until the second quarter of 2016, while DiDi was able to expand its coverage to more than 400 cities by placing emphasis on collaboration with taxi drivers and utilizing subsidies. With that, DiDi was able to reach 58.86 million monthly active users in 2016 and outsmart Uber.

Lesson 3: Service offering and strategic positioning can give a competitive advantage

DiDi and Uber competed in China's ride-hailing service market, with DiDi offering a (including e.g. lower-level services such as DiDi Express and Taxi) that covered almost every segment of the market from low- to high-end. DiDi also provided additional content related to urban mobility (such as travel information), helping improve and expand its business ecosystem. This, coupled with its low fares, attracted a larger number of users than Uber's focused strategy and helped DiDi on its path to success.

Lesson 4: Your strategy and services must be aligned with the value proposition

Uber failed to succeed in the Chinese ride-hailing market due to its inability to align expectations and predictions with its marketing strategies. As the competition for market share with DiDi and other existing platforms intensified, Uber failed to clarify what it wanted to do and how it could best succeed. As a result, Uber's services such as Uber Black did not reflect the characteristics of the high-end segment of the Chinese market well and failed to maximize the network effect. Additionally, Uber's strategic focus on premium services did not match its actual revenue sources—the premium services Uber XL and Uber Black accounted for only 8% of the company’s revenue. That explains the rather modest success of Uber China.

Lesson 5: In-depth study of user preferences is crucial

Both Uber and DiDi adopted a peer-to-peer business model, which works as a two-sided market connecting drivers and passengers. The platforms can control and manage drivers through service fees applied to access and use the platform, while attracting users by setting a reasonable platform usage fee and providing incentives. An on-demand service business that serves two unique user groups, you must understand which group would be more sensitive to pricing tiers and manage that group in order to maximize benefits.

Differences in pricing and incentive schemes of Uber and Didi resulted in significant performance gaps between them. Although Uber didn’t offer a service fee for its carpool service “People’s Uber”, the 5% added by DiDi was acceptable for Chinese users. In addition, DiDi’s adherence to quality standards enabled it to rapidly expand and build its own ecosystems in different regions, maximizing the benefits of network effects.

Lesson 6: Leave room for business expansion from all sides

DiDi and Uber China had different approaches to their service processes: DiDi incorporated the needs of both its users and drivers, allowing for more service options, payment methods, and better overall user experience compared to Uber. DiDi was also able to provide a more detailed procedure for drivers and had a close partnership with WeChat and Alipay. Uber, on the other hand, focused on simplicity and global standards rather than meeting the drivers’ needs in the Chinese market, where these standards didn’t work as well as in other markets. This difference in service processes is reflected in the value curves, with DiDi having an overall higher satisfaction rate among passengers.

Lesson 7: Partnerships do make a difference

DiDi and Uber both had partnerships with various organizations in order to gain access to key technologies and user bases, but their approaches to expanding relationships with partners differed. DiDi had a more diverse and rich partnership structure with companies across a number of industrial sectors, while Uber relied more heavily on its global brand awareness and traditional marketing tactics. This allowed DiDi to develop a wide range of service offerings, while Uber struggled to expand its regional base.

Creating a competitive business model for a service business

The main conclusion we can draw from the comparison of business models of Uber China and DiDi is that Uber failed to properly recognize the differences between the US and Chinese markets. What works in one market won’t necessarily work in another. DiDi seemed to have a better understanding of this rule and was able to align its strategy with this principle, which is clearly reflected in the company’s business model canvas.

Uber’s case highlights the importance of understanding and adapting to local market characteristics to increase the chances of success in order to succeed when competing on a global platform. DiDi managed to dominate 80% of the Chinese ride-hailing market and had significantly higher user awareness and brand loyalty than Uber. DiDi was ahead of Uber in terms of providing greater availability and flexibility for users, which demonstrates that mobility providers should offer more of these features to succeed.

Building a new software product? We’re here to help

The canvas model used in this study could be used to analyze other sharing economy platforms, such as Airbnb, which has been successful in the Chinese market due to its strategic implementation, including offering value propositions that are differentiated from local platforms, providing service offerings tailored to different target segments, and forming partnerships with local partners.

As a software development company supporting businesses in building innovative software products , we approach business model validation with immense care. Not only can we offer comprehensive support throughout the entire validation process and designing a product that will fully support your business goals, but we can also extend your team with seasoned domain experts. We have dedicated teams supporting our clients in building location-based services , media streaming applications, chat solutions, geospatial data visualization and more. If you’re looking for a specific domain expertise or developers with specific skills, contact me at [email protected] and I’d be happy to discuss what we can do for you.

People also ask

Want to read more.

10 German mobility startups and companies shaping the future of urban transportation

Electric Vehicle Routing - the ultimate guide to the best EV navigation providers

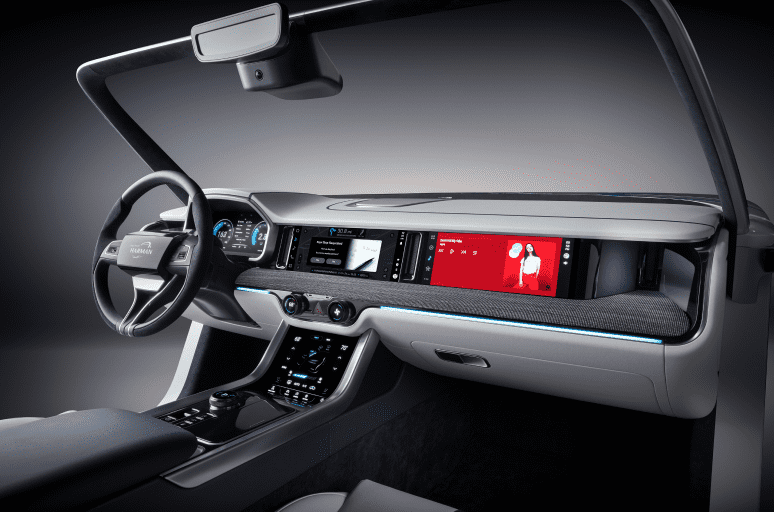

Automotive HMI design and development: how to build a digital cockpit

Home » Blog » The Real Reason Uber Is Giving Up in China

The Real Reason Uber Is Giving Up in China

Is heavy-handed state intervention killing entrepreneurship in China? William Kirby, Spangler Family Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, T. M. Chang Professor of China Studies at Harvard University, and Chairman of the Harvard China Fund explains.

This article first appeared in the Harvard Business Review on August 2, 2016.

Last September some of the world’s foremost technology industry leaders met in Seattle with Xi Jinping, president of China. In a group photograph, 30 CEOs with a combined market capitalization of $2.5 trillion smiled for the camera alongside the Chinese leader. They included Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, and leaders of some of the most prominent “sharing economy” companies: Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky and Didi Chuxing CEO Cheng Wei, the head of China’s leading taxi and private car hailing app. Conspicuously absent from the photo was Uber’s CEO , Travis Kalanick.

This did not bode well for Uber’s future in China. On Monday Uber said that it is selling its operation in China to a rival Chinese ride-sharing company whose CEO was in that foreshadowing photo. Cheng Wei will get a seat on Uber’s board as part of the deal. Kalanick gets the same on Didi Chuxing’s board, and Uber gets around a 20% share of the Chinese company, which will run Uber’s Chinese operation as a separate brand.

Much of the U.S. news coverage has centered on Uber capitulating to competition and getting schooled by its Chinese archfoe . It is true that Kalanick consistently called China the most important market for Uber. He joked to a Chinese publication that he was spending so much time in China that he should apply for Chinese citizenship . Uber truly wanted to succeed in its fastest-growing market, one where taxi drivers outnumber their U.S. counterparts tenfold. The company’s losses were mounting in a bid to win market share.

Still, I believe Uber is leaving China not because of interference from its rivals but because of interference from the state.

When Uber entered the Chinese market, it soon learned it had to change its core product . At first, customers had to validate credit card information before opening an account. This presented a major obstacle for many potential Chinese users . Uber China recognized this disadvantage in its business approach and, just in time for the formal launch in February 2014, added the option of payment through Alipay .

After that, Uber continued to use Google Maps to locate and match customers with drivers. But Google Maps coverage in China was extremely limited and notoriously inaccurate. So Uber China entered into a strategic partnership with Baidu in December 2014. Baidu, an economically powerful and politically connected company, was now in Uber’s inner circle of investors. Uber China also installed servers on Chinese soil to prevent its operations from getting disrupted while passing over China’s notorious firewall.

Yet even after making its core product more attractive to Chinese customers, Uber had to spend hugely to attract drivers and riders. New users were attracted to the platform by large discounts on their first trip, often equivalent to the full cost of the ride. Similarly, drivers were encouraged to join the service. In Chengdu, Uber drivers numbered 42,000, nearly the same as the number of Uber drivers in London, Paris, and San Francisco combined. But the company’s capital investment had an unintended consequence: It gave rise to a rampant economy of drivers faking trips for personal profit.

It was costly, but it still worked. Despite intense competition from two Chinese taxi-hailing services (that later merged to take on Uber more directly), Uber was succeeding because it could drive in a gray zone of Chinese markets .

After all, Uber’s aggressive push into China was made possible by the fact that the space was largely unregulated. The company founded local entity after local entity in China to compete in different urban markets. That’s a proven strategy; China is not one market for almost anything. My colleague Meg Rithmire has shown that different cities in China can have very different regulatory environments . Many successful private companies in China have realized they can succeed in areas where the government is not yet present or where it has not yet set regulations. Basically, you can succeed in any form of business that is not yet illegal. Ride sharing was one such business.

The losses Uber was taking to win market share were unsustainable. But the same goes for its erstwhile chief rival. Didi Chuxing had become the dominant Chinese player in the space. But neither company could afford the high level of subsidies (and resulting costs from driver corruption) needed to win new drivers and riders and new markets.

The losses Uber was taking to win market share were unsustainable.

In the end, it wasn’t competition that spelled Uber’s demise in China; it was impending national regulations. Uber was negotiating with Didi Chuxing as a new regulatory scheme was being written. The nationalization of industry regulation was bad news for a startup that depended on local variance and gray zones.

These national regulations are now a reality. To be sure, the headline reads well in the Xinhua news release on July 28, 2016: “ China Grants Legal Status to Ride-Hailing Services .” But legal status in China can come with handcuffs. The country’s first nationwide regulation of the industry was truly bad news for Uber and, if followed to the letter, bad news for the entire industry.

The country’s first nationwide regulation of the industry was truly bad news for Uber and, if followed to the letter, bad news for the entire industry.

Under the new regulations, the data collected by Uber would come under the purview of the government. There would be no more subsidies. Market prices would prevail, the regulations state, “except when municipal government officials believe it is necessary to implement government-guided pricing.” According to Xinhua, ride-hailing companies would be urged to merge with taxi companies. (Many of those also happen to be owned by the local governments.) Uber would have to get both provincial and national regulatory approval for its activities anywhere in China. Online and offline services would be regulated separately.

Moreover, foreign companies like Uber would be subject to even more regulation than their competitors. Even though Uber had been registered in the form of local companies, its national platform would now be handled differently. And despite this standardization of the industry, local governments would be allowed to issue “ride-hailing service driver’s licenses” and to determine who is eligible to be a driver and what kinds of cars can be driven.

This national regulation was an impending disaster for Uber. In retrospect, perhaps the company could have remained in charge and made money had it kept to its initial “niche” market for wealthy Chinese people and expats. But by going for the mass market to reach higher valuation and to fuel its larger platform strategy, Uber brought on extra challenges. Central government regulations were almost inevitable.

There is an English saying that a picture is worth a thousand words. You could certainly apply that to the fateful photograph of Xi Jinping and the top technology CEOs — the one where Kalanick is out of the picture.

There’s also a saying in China: “The nail that sticks up is the nail that gets hammered down.”

Here is the takeaway. Where the Chinese state steps in is where entrepreneurship goes to die. In selling its China business to Didi Chuxing, Uber is getting out of its China operations at the right time and at a reasonable price.

William C. Kirby is the Spangler Family Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and the T. M. Chang Professor of China Studies at Harvard University. His latest book, co-authored with Regina Abrami and F. Warren McFarlan, is Can China Lead? (HBR Press, 2014). He is the co-author, with Joycelyn Eby, Adam Mitchell, and Shuang Lu, of the case study, “ Uber in China: Driving in the Gray Zone ” (2016).

Uber’s battle for China

The car-hailing app has disrupted taxi and transport companies around the world. but in china – home to hundreds of millions of urban commuters – it is losing $1bn a year in an aggressive fight for market share..

In Uber’s new offices in Guangzhou, China, occasional screams of delight erupt from the workers at their desks as they spot the office cat, a shy thing that mostly hides under furniture and causes uproar whenever she appears. Her name is Qianwanliang, or “10 million rides”. It’s a rather grand name for such a timid creature but this is Uber, and ambition is inescapable – even for office pets. “It represents some of our trip goals,” admits Cleo Sham, a spiky-haired thirtysomething who has helped to turn Guangzhou, home to 12 million people in southern China, into Uber’s busiest city globally. When she joined a year and a half ago, the Guangzhou office was a room of just 180 sq ft.

“Three of us were crammed into a room, day and night,” Sham says with a touch of nostalgia. She handed out flyers, made cold calls, ran marketing booths. No one in Guangzhou had heard of Uber, and many people she approached would confuse Uber’s Chinese name, Youbu, with Youku, a Chinese video service. “There was a lot of scepticism, a lot of rejections,” she recalls.

Cleo Sham General Manager of Uber Guangzhou

Name recognition is no longer a problem. China is now Uber’s largest market, accounting for more than a third of its business in terms of weekly trips. It is Uber’s biggest bet, and also its toughest market: the company loses more money here than anywhere in the world. Last year, losses in China came to more than $1bn , and they are set to be at least as high this year, as Uber fights for market share against its powerful Chinese rival, Didi Chuxing.

The drive to conquer the Chinese market comes directly from Travis Kalanick , Uber’s 39-year-old chief executive, whose aggressive personal style has defined the company’s rise. Kalanick founded Uber in San Francisco six years ago with his friend Garrett Camp; the two originally envisaged a phone app for summoning limousines that would allow people to simply “push a button and get a ride”. Since then, the company has grown into a personal car service that has disrupted taxi and transportation companies around the world.

Uber now operates in 68 countries, but China was always special. “Travis was personally invested in the success of Uber in China to a much greater degree than any other country,” recalls Allen Penn, a 32-year-old American who is head of Asia operations at Uber. Last year, Kalanick spent nearly one in five days in China. In other countries, the company hires local chief executives, but here Kalanick maintains a hands-on role as chief executive of Uber China.

Travis Kalanick Uber chief executive

The company’s adventures in the country started just over three years ago, when Kalanick, Penn and a few top lieutenants took a scouting trip to try to figure out how Uber could avoid repeating the mistakes of other foreign tech companies. Most Silicon Valley tech giants, from Facebook and Google to Amazon, have met with failure in China, for reasons ranging from censorship to IP theft to government regulations that favour domestic champions. But Uber has always believed in its own exceptional status. “We like to go after the thing that seems impossible,” Kalanick tells me. “It was pretty far-flung for us to try at that time – but that was also what made it exciting.”

Uber decided on a China strategy that was unlike anything it had tried elsewhere. It would set up a separate Chinese entity, Uber China, which would court local investors as well as getting financial support from the global Uber business, which holds a large undisclosed stake in the subsidiary. The hope was that a Chinese company could avoid some of the restrictions faced by foreign businesses.

At the time of that scouting trip, Uber was a relatively small start-up. It had just over 100 employees, operated in 10 countries and had raised a cumulative $50m from investors. It was far from obvious then that the car-hailing app would become the global juggernaut that it is today – the most funded start-up of all time, with a private market valuation of $62.5bn. Its most recent cash injection, announced earlier this month, was a $3.5bn investment from Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund. It is also in talks to raise as much as $2bn in debt, which could bring its war chest to more than $13bn.

“We came to China and people just called me crazy,” Kalanick said in a speech in Beijing in January. “And maybe we still are.”

Uber was so focused on avoiding the pitfalls of western tech companies that its Chinese competitors – who simply offered traditional taxi services through apps – must have seemed like a sideshow during that first trip. In early 2013, China’s two largest taxi apps, Didi and Kuaidi, were just small companies with business models completely different from Uber’s.

But as Didi and Kuaidi grew, they went to war with each other, showering subsidies on taxi drivers and riders as they fought for market share. The subsidies were so generous that sophisticated scammers developed software to exploit them. Didi and Kuaidi were marking the playing field for what would later become the world’s most irrational ride-hailing market, and the rules of the game were largely set by the time Uber joined the fray.

In terms of its transport infrastructure, the Chinese market had many elements that made it ripe for disruption. Rapid urban migration has seen hundreds of millions of people pour into new cities over the past two decades, and transport options have not kept up. Taxi ranks have failed to keep pace with economic growth, making it hard to find a cab in certain cities. Gridlock and pollution are the result – problems that Uber proposes to help solve.

Uber’s formal launch in China came in February 2014, with the introduction of luxury car services in three Chinese cities: Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen. There were plenty of speed bumps, including the fact that Google Maps, which Uber uses to locate drivers and riders, is blocked in China, forcing the company to redesign its software. That autumn, Uber expanded its offering to include a cut-price service, People’s Uber, which allows anyone who clears a background check to offer rides in their personal vehicles. By the end of the year, Uber had captured about 1 per cent of the Chinese ride-sharing market.

Meanwhile, Didi and Kuaidi’s subsidy war eventually drove them into each other’s arms, and they announced a merger in February 2015.

Today, Didi Chuxing (known as “Didi” in China) is by far the largest ride-sharing group in the country, and the best capitalised. Last year it raised more than $2bn from investors including Tencent, Alibaba and China’s sovereign wealth fund, CIC. It has just closed a fresh funding round of $4.5bn from investors including Apple, in addition to a $2.8bn debt facility.

Didi has operations in more than 400 Chinese cities and is profitable in half of those. Uber initially focused on China’s largest cities and is now in more than 50, with a plan to reach 120 by September.

One immediate result of the merger in 2015 was that Didi and Kuaidi started spending less on taxi subsidies, and instead took aim at the private car-hailing market. Their subsidies for private car rides soared, costing the newly combined company $270m during the first five months of the year.

The use of subsidies turned Uber’s business model on its head. Typically, Uber takes a cut of about 25 per cent of the passenger’s fare and passes the rest of the fare on to the driver. Costs are kept low because Uber doesn’t employ the drivers, or own the cars. However, in China, Uber pays drivers a multiple of the passenger’s fare, meaning that the company loses money on most rides. Other Chinese ride-hailing companies employ a similar strategy.

Didi and Uber blame each other for the game of subsidy one-upmanship that has come to define the Chinese ride-hailing market. Usually, “Uber doesn’t really do this type of thing,” says Kalanick. “But we are the number two in China and we have to, in some ways, follow the lead of the number one.”

Meanwhile Didi paints its subsidies as purely defensive. Didi is “quite profitable” in cities where competitors’ subsidy practices are less aggressive, says Stephen Zhu, vice-president of Didi. “The reality is that subsidies are used to compensate for an inferior user and driver experience,” he says, without mentioning Uber by name.

The subsidies are pernicious, not only because they drain cash, but also because they mask true levels of demand and supply. “You can go out, spend a bunch of money in a city and gain some market share, but that’s not real,” says Penn, Uber’s Asia business head. “You’re just kind of buying all of it – [though] you’re really more renting than buying.”

Many drivers for Uber say they would not be driving if it weren’t for the bonuses, while passengers also say they would ride less if the services became more expensive. “I used to use Didi most of the time, but I switched to Uber because it was cheaper,” said Xu Desheng, a 32-year-old living in Beijing, who says he has become a daily Uber user because of the prices. While Uber’s services include luxury cars, cheaper rides are a bulwark of Uber’s business in China. Uber’s carpool service, with fares as low as Rmb2 (21 pence) accounts for more than half of rides in several key cities.

“Is Uber legal in America? Because it isn’t here,” says a 21-year-old driver in Beijing, surnamed Dong, the proud owner of a sedan that his parents helped him to buy.

It’s a question asked by almost every Uber driver when they carry a foreign passenger. Dong tells me that his brother was picked up by traffic cops while driving an Uber just a few days before, and was fined Rmb20,000 (£2,100) –roughly two months’ salary. As we approach my destination, a train station, he nervously tucks away the phone running the Uber app, then asks if he can drop me a few blocks away. Drivers are constantly sharing info about new traffic-cop checkpoints, and Beijing South Station was on the list that day.

Most Chinese drivers believe Uber is illegal (yet drive for it anyway), but the company is not technically banned in the country. In some ways, Uber’s rule-breaking ethos fits in with China’s rough-and- tumble economy, where entrepreneurialism is prized and bending the rules is normal. Kalanick says that, “China has been one of the most welcoming places we do business.” While that may be a slight exaggeration, it is true that the occasional police raids on Uber offices in China are minor frustrations compared to the outright bans Uber has faced elsewhere .

Liu Zhen Head of strategy and government relations, Uber China

“There are a lot of grey areas,” explains Liu Zhen, Uber China’s head of strategy and government relations, referring to the regulation of ride-hailing. “I wouldn’t say that it is not legal, it is in the process of being legalised.”

Liu has become the face of Uber in China when Kalanick is not around, and one of her prime tasks is to make sure that the “process of being legalised” goes as smoothly as possible. Beijing is working on a set of regulations that will completely redefine ride-sharing in China. An initial draft of the rules, published by China’s ministry of transport in October, proposed the potentially devastating move of banning ride-sharing in private cars.

Uber and Didi were both fairly quiet when the new rules came out. But within the government, there was pushback. “Innovation” and “the sharing economy” have become buzzwords at the highest echelons of the Communist party, and the new draft regulations were hardly in keeping with that spirit. The State Council, China’s cabinet, asked the ministry of transport to revise the regulations, sparking a debate that is still going on.

After China’s decades of economic reform, embracing the sharing economy is a small step in the broader transformation to a market economy, says Liu Yuanju, a Shanghai-based economist. “There’s a lot of will to support innovation,” he says. “There are parts of the government that definitely want to embrace this [the sharing economy] but they also face a lot of pressure.”

He explains that the ride-sharing rules are just a bit part in a much larger drama, as a behind-the-scenes struggle between conservative and innovative factions within the Chinese state plays out. China’s premier, Li Keqiang, has made innovation a key part of his agenda, and has personally met Kalanick, as well as Didi’s founder, Cheng Wei.

So far there have only been a few hints as to what the new rules might contain. In March, China’s transport minister delivered a blistering critique of the ride-hailing subsidies, calling them “unsustainable” and “unfair” to taxis. However, he also acknowledged that private car services were popular, and hinted that they could be formally legalised after some type of driver-registration process.

Zhou Hang, the founder of the ride-sharing start-up Yidao Yongche, says he expects ride-sharing in private cars to be permitted under the new regulations – but that the number of these cars will be “very limited”. He expects the cheapest type of ride services will be the most affected, which could spell bad news for Uber. However, few analysts expect that Uber’s foreign roots will mean it faces special barriers. “It’s very different from Facebook or Twitter,” says Liu, the economist, referring to the services banned in China because of censorship.

Zhang Yi, the CEO of iMedia, a Guangzhou-based consultancy, points to Apple, which draws a quarter of its sales from China. “Why did Apple succeed [in China]? It’s because they were purely about business,” he says, waving his iPhone in the air. Uber’s business doesn’t touch on sensitive topics such as national security, he says, adding that its devolved corporate structure helps. “Didi has foreign investors, and Uber China is independent, so in terms of the shareholders there is basically no difference.” Uber has already nodded to any data concerns Beijing might have by storing riders’ information on local servers in China.

W hile questions about ride-sharing rules hang in the air, Uber China is also grappling with a different threat: fraud. China has the most sophisticated ride-hailing scams in the world, in which drivers and hackers milk ride-hailing companies for bonuses without carrying actual passengers.

The scammers have even developed their own lexicon, to make it easier to communicate covertly in online forums. A fake ride is known as “getting an injection”, a reference to the red location pins in the Uber app. “Hey, give me a shot,” a driver will post – and then a scammer, who typically advertises themselves as a “professional nurse”, will respond.

The scammers create a fake passenger account that will appear to take a ride with a driver – who gets the bonus. About 3 per cent of Uber’s rides in China were fraudulent during the summer of 2015 – about 30,00 daily rides – and fraud continues to be a problem.

Uber managers spend hours each week checking driver logs for fraud patterns and deciding which drivers to deactivate. “Every Monday is pay day, and fraud day,” recalls a former Uber employee, explaining that fraud reviews happened just before drivers are paid. When he worked at Uber, in 2015, “The frauds that got caught were the really severe cases… only those who do hundreds [of fraudulent trips] per week.”

Tiger Fang General Manager of Uber Chengdu

Uber says it has improved at fighting fraud. “We have some of our smartest engineers working on this problem,” says Tiger Fang, who heads Uber’s operations in Chengdu, and has himself dived into some of the scammers’ online chat-rooms, posing undercover to ask about their methods. There’s a team of 50 engineers at Uber headquarters in San Francisco that focuses on fraud detection, as well as local manual review teams in each Chinese city. Uber recently introduced additional identity verification features – such as voice recognition for passengers and facial recognition for drivers – in an effort to cut down on fake accounts.

Fraud levels are falling not only because of these efforts, but also thanks to the fact that subsidies have been greatly reduced, lowering the financial incentives for fraudsters. Uber says it has cut subsidies in China by 80 per cent on a per-trip basis over the past year, while the volume of rides has risen by 16 times during that same period.

This trend is a key part of Uber’s argument for why it can eventually succeed in China without subsidies. Fang, the Chengdu manager, explains that the subsidies become less important as Uber’s network grows and drivers can carry more passengers per hour. “The more rides we do, the less money per trip we are losing [on subsidies] because we are increasing efficiency through the overall system,” he says.

But removing subsidies altogether will not be easy. Examples from other markets show that heavily subsidised businesses sometimes just evaporate once the subsidies disappear. The taxi-hailing business of Didi and Kuaidi, which was initially fuelled by subsidies, is now a tiny fraction of their merged business and generates no revenues. Smaller ride-hailing companies in other markets, such as EasyTaxi in Jakarta, found that their business dried up completely when subsidies ended.

Cutting subsidies is particularly hard for a company that, like Uber China, is not the market leader. Market share figures in China vary greatly depending on who is counting – Uber says it has more than 30 per cent of the ride-hailing market, while Didi says it has more than 80 per cent – but everyone agrees Uber is far smaller. Having the greatest market share confers a huge advantage in ride-sharing, because the quality of the product improves as more drivers and riders join the system: passengers don’t have to wait as long and drivers can make more money. This “network effect” is the reason ride-hailing companies are willing to spend everything to gain dominance in a market.

How much Uber will keep spending in China to fight for that market share is a key question. Unlike in other countries, Uber China is a separate entity with plans for an independent IPO, and it does its own fundraising in addition to getting cash from Uber Global. Last year Uber China raised $1.2bn after a prolonged fundraising effort, at a valuation of $7bn. However, it would not disclose how much of that was from investors and how much from Uber’s own coffers – nor what Uber’s stake in Uber China is. (The company says only that it is the “largest” shareholder in Uber China.) The fundraising did succeed in attracting some high-profile Chinese backers, including HNA Group and Guangzhou Auto.

Kalanick says Uber also uses its profits from other markets to support investment in China, but won’t say by how much. Since February, Uber has been profitable, excluding interest and tax, in North America, Australia and in its Europe-Middle East-Africa region.

But there are other demands on Uber’s cash, the largest of which is defending its market share against other incumbents. Even outside China, Didi has become a formidable enemy for Uber by forming an alliance with several competitors, including Lyft in the US, Ola in India and Grab in Southeast Asia. Didi has encouraged its Chinese backers such as Alibaba and Tencent to invest in those rivals. The four companies are also linking their apps, so that customers can tap into the others’ car networks when travelling.

Uber’s profits have not been totally immune to this pincer movement. It has cut prices and become unprofitable in some cities in the US in order to stave off advances from Lyft. “Though we do become profitable from time to time, we have to make conscious decisions, even in mature markets, to go unprofitable to protect market share,” says one Uber executive. He says the subsidy competition would “just end if this irrational funding would stop at some point”, referring to fundraising by global ride-sharing groups. When companies are losing money on every trip, “it really reminds me of 1999, or the tech bubble”, he adds.

Uber’s biggest problem in China has turned out to be not that it is a foreign company, but that it has finally met a counterpart every bit as disruptive and aggressive as itself. “For Uber, the biggest risk is from a competitive market, not from the government,” says iMedia’s Zhang.

Given Uber’s deep reserves of cash, it can afford to keep investing. And as a private company, it won’t come under pressure from shareholders demanding profits. Kalanick has said that Uber will go public “as late as humanly possible”, giving a range of one to 10 years – ample time to keep pouring money into loss-making operations. But is there a point at which it would draw a line in China? Kalanick says there’s not a specific number in terms of how much he is willing to invest. “The most important limit is the return on investment,” he muses. “What is your business worth? You certainly don’t want to spend more than it is worth.”

With no net revenues and no profits, Uber China’s worth is hard to assess. As number two in the market, it will always have a somewhat precarious position. Several top Uber China executives say that the company does not need majority market share in China in order to have a sustainable, profitable business. Kalanick, however, defines success in China as being number one – and he doesn’t give up easily. “We like those problems that are hard, those are the ones that excite us most,” he says. “Those are the ones that give us that little glimmer in the eye and get us up in the morning.”

Leslie Hook is an FT San Francisco correspondent

How Uber crashed in China

Professor of Practice, Associate Dean., Warwick Business School, University of Warwick

Disclosure statement

John Colley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Warwick provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Uber has announced its exit from the Chinese taxi market by merging with arch-rival Didi Chuxing in a US$35 billion deal. Uber is selling its operations to Didi, with Uber China investors receiving a 20% stake in Didi, according to reports .

It represents a major defeat for the San Francisco-based tech giant after a long and hard-fought battle to dominate China’s ride hailing market . Uber tried to succeed where other Western companies had failed in China but, like Google and Amazon before it, found that Chinese markets tend to be enormously competitive with very narrow margins. On top of this, Uber found itself the victim of the business model that is behind its own success in numerous other countries – the network effect.

Uber’s business model relies on being the first entrant to a market, then rapidly developing its size and scale so that the competitors that follow are disadvantaged to the point of a forced exit. Uber’s success in other countries has followed this formula. By being first to a market, Uber generates rapid scale through subsidies, offering both cheap rides to passengers and providing incentives to attract drivers.

As passenger numbers increase, this attracts more drivers who receive more fares. Greater numbers of drivers provides higher customer responsiveness, which is the key customer need, followed by lower cost fares. The model usually leads to a winner takes all situation, as later entrants have to attract passengers without the drivers to provide a competitive service level.

Second best

The network effect model paid dividends for Uber in the US and many European cities. But in China, Didi Chuxing got there first. The product of a merger between the country’s homegrown ride-hailing leaders, Didi Dache and Kuaidi Dache, Didi Chuxing is believed to hold 80% of the market through its own aggressive use of subsidies.

The side that is late to the party might as well give up. The costs of unseating the leader in terms of attracting passengers and drivers becomes enormous, as Uber has experienced in China. Its attempts to get in on the Chinese market through discounts and promotions have left the company with losses of roughly US$2 billion .

The drive to dominate the Chinese market came directly from Uber CEO Travis Kalanick. He was heavily involved in Uber’s launch into China – first visiting the country on a scouting trip in April 2013. And his aggressive investments elsewhere have generally paid off . With profits from its operations in 75 other countries subsidising China, Kalanick was no doubt hoping that its investment in China would eventually pay off. Ultimately, a face saving exit was needed, which Didi Chuxing has provided.

The promise and pitfalls of China

The Chinese market has been the graveyard for many Western businesses. Despite showing sensitivity to the unique nature of the China market (for example, by setting up a separate entity, Uber China, to partner with local investors), Uber joins this group.

Alongside the offer of hundreds of millions of consumers, markets in China are very competitive. Not only is technology and knowhow difficult to protect, competitors are often government owned and do not have to make a return. Didi Chuxing has significant investment from China’s internet giants Tencent and Alibaba, as well as the country’s sovereign wealth fund CIC, and Apple .

When businesses internationalise they usually need a partner who understands the culture, connections, distribution and the market itself. The objective is usually to buy out the local partner once a developed understanding has been achieved by the multinational. But in China, because the market is difficult, the reverse often occurs, with multinationals often selling out to local partners.

For example, brewing giant SABMiller’s Snow brand of beer, reputed to hold 20% of the Chinese beer market, was sold to China Resource Enterprise, its government owned partner, for a tiny US$1.5 billion earlier this year . Others have similarly exited such as Tesco and Groupon . Western businesses often bring their knowledge, experience, technology and capabilities – and leave them there. In Uber’s case, this is in return for a 20% shareholding in Didi Chuxing. If Yahoo’s experience with Alibaba is anything to go by, this could be the best way of profitably participating in this difficult market.

Overall, Uber’s exit demonstrates the difficulty for late entrants in web-based “network” markets, which have to wait for changes in technology or market trends before they can prosper. It also shows the difficulty of Chinese markets which can deliver enormous volumes but are highly competitive. Local competitors often hold the advantages. Here, Uber joins a long line of companies the world over, whose boards are pondering their losses in China’s markets and considering their options.

- Chinese economy

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Globalisation

Program Manager, Teaching & Learning Initiatives

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Why Uber is giving up on China

Uber is giving up its ambitions of becoming a dominant force in China's ride-hailing industry.

In agreeing to sell all its operations in China to Didi Chuxing , Uber has done something unusual: concede to a rival.

The value of the deal, confirmed by the company today hasn't been revealed, but whatever that agreement, both companies just saved themselves millions (if not billions) of dollars.

Uber's attempt to establish itself in China, where many other western companies have failed, saw it grow to around 150 million trips per month – but even with that sort of scale, it wasn't making any money. Battling a market incumbent, which Uber is used to doing, is an expensive business.

Uber founder and CEO Travis Kalanick said that the decision to leave China was about "listening to your head as well as following your heart". He added that both Uber and Didi were investing "billions of dollars" in China without turning a profit.

"Getting to profitability is the only way to build a sustainable business that can best serve Chinese riders, drivers and cities over the long term," he added.

The structure of the deal, according to Recode , are complex. Uber China becomes part of Didi and in exchange Uber gets 20 per cent of the value of the whole of Didi (now around $35 billion, £26.5bn) and Didi will invest in the wider Uber company.

On the surface of things, it's a win-win for the both companies. Ending the 'war' saves money and allows them to pool their huge customer bases. How well Uber's decision will be received outside of China remains to be seen.

Outside China Uber has other battles on its hands with companies such as Lyft and Ola, both of which Didi also holds investments in. The real winner here could well be Didi, which now has investments in every major player in key markets.

This article was originally published by WIRED UK

Matt Jancer

Boone Ashworth

David Nield

Scott Gilbertson

Amanda Hoover

Paresh Dave

Kathy Gilsinan

Will Knight

Lydia Morrish

Dell Cameron

Matt Burgess

Case Study of the Uber Failure in China: A Technoethical Analysis

Journal Title

Journal issn, volume title, description, collections.

- | Accessibility

- International Telecommunications Society (ITS)

- 22nd ITS Biennial Conference, Seoul 2018

Why did Uber China fail in China? – Lessons from Business Model Analysis

Items in EconStor are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

Why did Uber China fail in China? – Lessons from Business Model Analysis

- Author & abstract

- 3 References

- Most related

- Related works & more

Corrections

- Liu, Yunhan

- Kim, Dohoon

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher, references listed on ideas.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

Switch to the dark mode that's kinder on your eyes at night time.

Switch to the light mode that's kinder on your eyes at day time.

Why Uber Failed in China? – Case Study

In 2016, Uber fled China. It surrendered a massive market and sold its $8 billion business to Liu’s Didi less than a week after Chinese regulators legalized ride sharing in any capacity.

It’s happened countless times before: A thriving American company enters China with 1.4 billion dollar signs in its eyes.

It sees in the country almost the ideal market: A middle class well over twice as large as its own and without the generational brand loyalties of America. Because China was relatively late in its technological development, it almost entirely skipped transitional, “in-between” inventions like desktop computers and credit cards, making Chinese consumers generally less skeptical of new technologies like smartphones. Best of all, all this is available through one international expansion, one regulatory system, one language, and one culture.

Or so, companies think. What they find is often very different. Relaxed regulation turns out to mean the law is ambiguous and enforced selectively. Once a business model is proven, competition may spring out of nowhere, sometimes with no regard for intellectual property. And what looks like a single, unified market from the outside becomes thousands of unique ones up close. It’s happened, in one form or another, to Amazon , Google , Mattel , eBay , Home Depot , Groupon , and many others.

Uber, however, was sure it was different. It wasn’t ignorant of the titans that had failed before it, but, in the mind of its outspoken founder, Travis Kalanick, Uber had faced many “impossible challenges” from the very beginning — fighting hundreds of angry cities as the company rapidly expanded across the U.S. Its very business model was at best legally ambiguous, and yet, it succeeded anyway, giving Kalanick certain unchecked confidence which made China look like only another of its familiar hurdles.

And to its credit, Uber did not make the classic mistake: Directing the expansion from conference rooms in San Francisco. It tried very hard to build “Uber China”, not merely Uber in China. After boldly declaring it the company’s “number one priority”, Kalanick devoted himself to the expansion like nowhere else. He spent 70 days of 2015 in the country — nearly 1/5th of the entire year. He even joked that he should apply for Chinese citizenship.

Uber created a separate, Chinese company, partnered with local investors like the Chinese tech giant Baidu, and launched in 2013 in the country’s largest city, Shanghai. At first, things were rocky. For example, it launched with only US credit card support, making sure the vast majority of locals, who use WeChat and AliPay, we’re unable to book rides. Just as embarrassing, the app used Google Maps, which is notoriously bad in China.

By far Uber’s biggest problem, however, was, well, its entire business model. The company doesn’t own its cars or hire its employees, meaning its only value is connecting people who want to drive to nearby people to want to ride. But because drivers and riders are regional, entering a new city is like starting from scratch. | Uber failed in china |

Uber may have a monopoly in LA, but that won’t mean anything when it expands to Seattle. The good thing is that once it has a critical number of both drivers and riders in a particular city, they’re very likely to stick with Uber. It only takes 2.7 rides, according to the company, before someone becomes a permanent customer.

Uber’s strategy, therefore, was to grow with lightning speed. Every major city had its own general manager, who would tempt new drivers with bonuses and new customers with free rides. Becoming a driver was easy, no long background checks or complicated forms were required. This worked pretty well. When it was first. The problem was that, in China, it wasn’t.

Its Chinese competitor — Didi — was founded in 2012 and had everything Uber needed: immense scale, a China-first design, and the support of government. While Uber operated by disrupting the taxi monopoly in each new city it entered, Didi was much more old-fashioned — it merely connected riders to existing licensed taxi drivers. So instead of inciting chaos and even violence like Uber, Didi was on the good side of authorities — even helping manage over 1,300 traffic lights in partnership with city governments.

In 2015, Didi merged with its closest competitor, giving it near-monopoly control of the market. It became the only company in the world backed by all three of China’s tech giants: Baidu, Alibaba , and Tencen t. Apple and China’s sovereign wealth fund also invested around that time. Uber was behind from day 1. If a Chinese user already had Didi, the only reason they’d switch is if it was that much cheaper. | Uber failed in china |

To catch up, Uber had to dump insane amounts of money. And, that’s exactly what it did. Uber spent a jaw-dropping $40-50 million US dollars per week on free rides and bonuses in China. It lost, in total, $1 billion every year. With Didi, it played a massive game of chicken — spending this much money was unsustainable, but who would give up first?

This metaphorical arms race also created a kind-of cold war dynamic. Didi allegedly sent undercover engineers to be hired by Uber, where they would collect trade secrets and even conduct sabotage. On occasion, Uber would be blocked from WeChat. In China, this was the equivalent of Google hiding a competitor from its search results — making it effectively invisible to the vast majority of the country.

And besides burning through cash like it was fuel, this subsidy war also led to an unintended side-effect: fraud. In one Chinese city, Uber reported having as many drivers as London, Paris, and San Francisco combined. But how many of them were real?

When a “new” user was offered a free promotional Uber ride, the company still paid the driver as normal. This created a loophole. Two users, one acting as the “driver”, and the other as the “rider” could collide, taking a fake ride, and splitting the profit. Soon, scammers created entire circuit boards with rows of SIM card slots, each simulating a fake phone. They would take a fake ride, swap out SIM cards, and repeat. | Uber failed in china |

In one Chinese city, fraud accounted for an estimated half of all rides. Over 30,000 fake rides were taken every day in the summer of 2015, just in China. Uber fought back by creating a database of IMEI numbers, which are unique to a given phone, and thus allowed the company to identify a scammer even after they had reset their phone.

However, Apple hid this number from developers starting in 2012 for its users’ privacy, preventing Uber from detecting fraud. Uber was undeterred and hired a 3rd party hacking company to bypass iOS’ security rules, which, Apple discovered, warning them to stop. In its typical fashion, Uber continued anyway, adding a line of code to check if the app was running in Cupertino, California, where Apple is headquartered, and if so, not break its rules. | Uber failed in china |

Apple still found out and called a very angry meeting. Things were not going well for Uber. It faced massive fraud, trouble with Apple, and over $1 billion a year in losses. Then came the final nail in the coffin. For its first few years in China, Uber operated in a legal grey area. Like in the U.S., this subject it to varying levels of retribution based on the mood of each municipal government.

Related Topics:

- How Did Microsoft Beat Apple? | Market Analysis

- Rubber Apocalypse – The Major Concern of World Power

- Why is US Boat Sales Booming? – Market Analysis

- How Does Waste Recycling Make Money?

In the Southern city of Guangzhou, police raided the Uber office at midnight, accusing it of running an illegal business. In Hangzhou, another police raid was followed by a violent confrontation between Uber and taxi drivers. All this changed in July 2016, after a series of high-profile crimes committed by Didi drivers. China legalized the industry, which came with strict new regulations like there could be no subsidies and drivers required 3-years of experience.

From now on, Uber would need to request formal approval from the local and national government before expanding to each new city. At the beginning of that year, Uber operated in 37 Chinese cities to Didi’s 400 and had 229 million daily active users compared with 908. Just a few short years after it had sprinted into the country with supreme confidence, it had all finally become too much. | Uber failed in china |

Just days after the new regulations were passed, Uber China was sold to Didi. Uber took a 19% stake in Didi, and the leaders of both received positions on each other’s board of directors. Whether this was an embarrassing failure or a diligent strategic decision is still open for debate.

On one hand, Uber unequivocally did not achieve its original goal of conquering the Chinese market. It left with only a minuscule market share and incredible losses. It did not succeed where others had failed in China, and even though government protectionism may be somewhat to blame, Uber certainly made many unforced errors along the way.

On the other hand, Uber spent $2 billion on China and left with assets valued at seven billion dollars. Viewed purely from the balance sheet, China was, unlike most of the company’s markets, a source of pure profit. It could now invest that money in other, more win-able markets in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

Best Places in New York City | Travel Guide

How Singapore Solved Healthcare?

Copyright © 2024 by Current Digest. All Rights Reserved.

Why Did Uber China Fail? Lessons from Business Model Analysis

- College of Management

- School of Management

- Seoul Campus

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

The ride-hailing platform offers the business model of the on-demand business ecosystem in the era of the sharing economy. Platforms such as Uber, Lyft, and DiDi have become popular worldwide and established a strong position in urban transportation. This paper presents a case study analyzing the fierce competition between Uber and DiDi in the Chinese ride-hailing market. First, employing the canvas framework, we show the core characteristics of the business models of the two platforms. Our analysis and comparisons of the strategic positioning and implementation concerning the building blocks of canvas ascribe the success factors of DiDi and the causes of Uber’s failure. Although both Uber and DiDi provide similar service offerings for diverse market segments, Uber’s mismatches between its strategic focus on the premium segment and service operations proved to be a mistake. On the other hand, DiDi managed its business more efficiently by providing a wide range of service offerings while leveraging the two-sided market. As a result, DiDi has grown successfully as a one-stop transportation platform, which is well-suited to the Chinese market. This study provides meaningful insights into business model innovations in the sharing economy and implications for the evolution of future transportation platforms.

Bibliographical note

- DiDi Chuxing

- canvas model

- ride-hailing platform

- sharing economy

This output contributes to the following UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Access to Document

- 10.3390/joitmc8020090

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Business Models Computer Science 100%

- Service Offering Computer Science 100%

- Business Model Analysis Computer Science 100%

- Model Analysis Social Sciences 100%

- Business Model Social Sciences 100%

- Building-Blocks Computer Science 50%

- Chinese Market Computer Science 50%

- Strategic Positioning Computer Science 50%

T1 - Why Did Uber China Fail? Lessons from Business Model Analysis

AU - Liu, Yunhan

AU - Kim, Dohoon

N1 - Publisher Copyright: © 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

PY - 2022/6

Y1 - 2022/6

N2 - The ride-hailing platform offers the business model of the on-demand business ecosystem in the era of the sharing economy. Platforms such as Uber, Lyft, and DiDi have become popular worldwide and established a strong position in urban transportation. This paper presents a case study analyzing the fierce competition between Uber and DiDi in the Chinese ride-hailing market. First, employing the canvas framework, we show the core characteristics of the business models of the two platforms. Our analysis and comparisons of the strategic positioning and implementation concerning the building blocks of canvas ascribe the success factors of DiDi and the causes of Uber’s failure. Although both Uber and DiDi provide similar service offerings for diverse market segments, Uber’s mismatches between its strategic focus on the premium segment and service operations proved to be a mistake. On the other hand, DiDi managed its business more efficiently by providing a wide range of service offerings while leveraging the two-sided market. As a result, DiDi has grown successfully as a one-stop transportation platform, which is well-suited to the Chinese market. This study provides meaningful insights into business model innovations in the sharing economy and implications for the evolution of future transportation platforms.

AB - The ride-hailing platform offers the business model of the on-demand business ecosystem in the era of the sharing economy. Platforms such as Uber, Lyft, and DiDi have become popular worldwide and established a strong position in urban transportation. This paper presents a case study analyzing the fierce competition between Uber and DiDi in the Chinese ride-hailing market. First, employing the canvas framework, we show the core characteristics of the business models of the two platforms. Our analysis and comparisons of the strategic positioning and implementation concerning the building blocks of canvas ascribe the success factors of DiDi and the causes of Uber’s failure. Although both Uber and DiDi provide similar service offerings for diverse market segments, Uber’s mismatches between its strategic focus on the premium segment and service operations proved to be a mistake. On the other hand, DiDi managed its business more efficiently by providing a wide range of service offerings while leveraging the two-sided market. As a result, DiDi has grown successfully as a one-stop transportation platform, which is well-suited to the Chinese market. This study provides meaningful insights into business model innovations in the sharing economy and implications for the evolution of future transportation platforms.

KW - DiDi Chuxing

KW - Uber China

KW - canvas model

KW - ride-hailing platform

KW - sharing economy

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85130391493&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.3390/joitmc8020090

DO - 10.3390/joitmc8020090

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:85130391493

SN - 2199-8531

JO - Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity

JF - Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity

IMAGES

COMMENTS

He is the co-author, with Joycelyn Eby, Adam Mitchell, and Shuang Lu, of the case study, "Uber in China: Driving in the Gray Zone" (2016). Post. Post. Share. Annotate. Save. Get PDF.

Concluding Remarks. Our paper presents a case study that analyzes the fierce competition between global giants Uber and DiDi in the Chinese ride-hailing market and the failure of Uber in this market. We compared and analyzed the characteristics of the BMs of the two platforms based on the canvas framework.

This is why Uber failed in China. When asked about Uber's attempt to dominate in the vast market that is China, the CEO of homegrown ride-sharing company Didi Chuxing, Jean Liu, said it was "cute ...

Uber's failure to conquer the market in China and merging with its competitor DiDi Chuxing is living proof of this statement. Uber and DiDi, two of the leading ride-hailing services in the world, entered the Chinese market in 2014 and competed fiercely for market share. Despite investing more than USD 1 billion a year, Uber was unable to ...

The ride-hailing platform offers the business model of the on-demand business ecosystem in the era of the sharing economy. Platforms such as Uber, Lyft, and DiDi have become popular worldwide and established a strong position in urban transportation. This paper presents a case study analyzing the fierce competition between Uber and DiDi in the Chinese ride-hailing market. First, employing the ...

This did not bode well for Uber's future in China. On Monday Uber said that it is selling its operation in China to a rival Chinese ride-sharing company whose CEO was in that foreshadowing photo. Cheng Wei will get a seat on Uber's board as part of the deal. Kalanick gets the same on Didi Chuxing's board, and Uber gets around a 20% share ...

It is Uber's biggest bet, and also its toughest market: the company loses more money here than anywhere in the world. Last year, losses in China came to more than $1bn, and they are set to be at least as high this year, as Uber fights for market share against its powerful Chinese rival, Didi Chuxing.

Uber China launched in February 2014 and this shows that Uber more than was ayear ahead of local rivals in introducing the sharing economy, a completely new ecommerce mode l for the public in China. After Uber failed in China, a surge of studies focused on the marketing strategies, intensive

Uber tried to succeed where other Western companies had failed in China but, like Google and Amazon before it, found that Chinese markets tend to be enormously competitive with very narrow margins ...

Two months later the American ride-hailing giant threw in the towel, selling its Chinese operations to its Beijing-based rival, Didi. Uber lost some $2bn over two years in China. Its retreat paved ...

Uber's attempt to establish itself in China, where many other western companies have failed, saw it grow to around 150 million trips per month - but even with that sort of scale, it wasn't ...

weaken Uber's market share and finally managed to dominate 80% of China's ride-hailing. market in 2016. As a result, in a 2016 survey, when both platforms wer e competing, 77.2%. of ...

Why did Uber China fail in China? - Lessons from Business Model Analysis Yunhan Liu, Dohoon Kim School of Management, Kyung Hee University [email protected], [email protected] Abstract The ride-hailing platform presents an on-demand business model on the basis of business ecosystems in the era of the sharing economy.