Home — Essay Samples — History — History of the United States — Westward Expansion

Essays on Westward Expansion

🌄 westward expansion: journey to the wild west.

Hey, history buffs! Ever wondered about Westward Expansion? It's an epic tale of adventure and discovery in the American frontier. So, why write an essay about it? Well, it's not just a school thing; it's a chance to relive the thrilling journey of pioneers, cowboys, and trailblazers who shaped the West. Let's saddle up and explore the frontier! 🤠

📝 Westward Expansion Essay Topics: Riding into the Unknown

Choosing the right topic for your Westward Expansion essay is key. You want to dive into something that sparks your curiosity. Check out these ideas:

🚀 Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny was the driving force behind Westward Expansion. Here are some essay topics to consider:

- What is Manifest Destiny, and how did it shape the Westward Expansion?

- Debates surrounding Manifest Destiny: expansion or imperialism?

- Notable figures who championed Manifest Destiny and their impact.

- The consequences of Manifest Destiny on indigenous peoples and nations.

🌟 Pioneers and Explorers

The West was explored by brave pioneers and adventurers. Explore these essay topics:

- The Oregon Trail: the challenges and triumphs of westward migration.

- The famous Lewis and Clark expedition: mapping the unknown West.

- Frontiersmen and women who made their mark on the wilderness.

- The Gold Rushes: how gold fever shaped the West and its communities.

⚔️ Indigenous Peoples and Conflicts

The Westward Expansion had a significant impact on indigenous populations. These essay topics delve into this complex history:

- The displacement and challenges faced by Native American tribes.

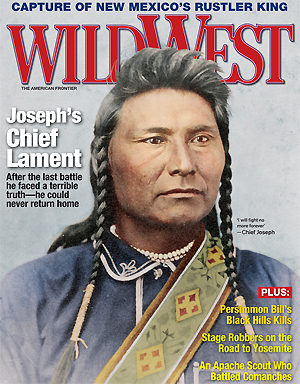

- Notable Native American leaders and their resistance efforts.

- Treaties and conflicts between settlers and indigenous peoples.

- Trail of Tears: the tragic journey of the Cherokee Nation.

🏙️ Impact on Society

Westward Expansion transformed American society. Explore these essay ideas:

- How Westward Expansion contributed to the growth of cities and urbanization.

- The role of women in shaping the West and advocating for their rights.

- The impact of the Homestead Act on land ownership and farming in the West.

- The legacy of the Wild West in American culture and media.

✍️ Westward Expansion Essay Example

📜 thesis statement examples.

1. "Westward Expansion, driven by the concept of Manifest Destiny, was a pivotal period in American history that transformed the nation's landscape, culture, and relationships with indigenous peoples. This essay explores the motivations, challenges, and consequences of this extraordinary journey."

2. "The pioneers and explorers who ventured into the untamed West epitomized the spirit of adventure and ambition. This essay delves into their remarkable stories, highlighting the challenges they faced, the discoveries they made, and the enduring impact they had on the American frontier."

3. "The Westward Expansion was a complex and often tragic chapter in American history, marked by the clash of cultures and the displacement of indigenous peoples. This essay examines the multifaceted aspects of this expansion, from the relentless drive for land to the enduring resilience of Native American communities."

4. "Westward Expansion not only reshaped the geography of the United States but also left an indelible mark on its social fabric. From the struggles of pioneers to the changing roles of women, this essay explores the multifaceted impact of this historic journey on American society and culture."

📝 Westward Expansion Essay Introduction Paragraph Examples

1. "In the early 19th century, a bold vision known as Manifest Destiny ignited the flames of westward expansion across the American continent. This essay is a time machine, taking us back to an era of pioneers, explorers, and frontiersmen who ventured into the unknown with dreams of prosperity, adventure, and discovery. Join us on this journey into the heart of the Wild West."

2. "The Wild West isn't just a Hollywood invention; it's a real chapter in American history, filled with untamed landscapes, daring pioneers, and epic adventures. In this essay, we'll embark on a quest to unravel the mysteries of Westward Expansion, from the rugged trails of the Oregon Trail to the confrontations with indigenous peoples who called the West home."

3. "The tale of Westward Expansion is a tapestry woven with ambition, hardship, and conflict. Beyond the romanticized images of cowboys and gold rushes lies a complex and transformative journey. This essay serves as our compass, guiding us through the diverse landscapes, cultures, and stories that define the American frontier."

🔚 Westward Expansion Essay Conclusion Paragraph Examples

1. "As we conclude this essay on Westward Expansion, we're reminded that the spirit of adventure and the pursuit of dreams have shaped our nation's history. The legacy of those who blazed trails and faced the unknown endures in the very fabric of the United States. Let us honor their courage and explore the lessons of the frontier as we continue our journey through time."

2. "In the annals of American history, the Westward Expansion stands as a testament to human ambition, resilience, and the enduring quest for freedom. The challenges faced and the sacrifices made by pioneers and indigenous peoples alike remind us of the complexities of our nation's past. Let this essay be a tribute to their stories and a reminder of the landscapes they shaped."

3. "Westward Expansion paints a vivid portrait of America's transformation, where untamed wilderness met the relentless ambition of pioneers. As we bid farewell to this essay, may we carry forward the lessons of the Wild West—lessons of perseverance, cultural exchange, and the enduring spirit of exploration. The West, with all its mysteries and challenges, remains an integral part of our nation's identity."

Manifest Destiny and Manifest Destiny

Major factors for westward expansion, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Impact of Western Expansion

How westward expansion affected the united states, american revolution's negative impact on native american history, the effects of westward expansion on immigrant life in the united states, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Westward Expansion and The American Dream

The positive and negative effects of the california gold rush on westward expansion, history of the oregon trail and its effect on america, the main struggles of the oregon trail, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Oregon Trail in American History

Civil war causes: westward expansion, compromise failure & south’s fear, the oregon trail and its pioneers, the powerful west: colonialism & separation of church and state, westward expansion: its impact on american history and society, summary of inskeeps jacksonland, monarchy in ancient greece.

Western Territories of the United States

The Westward expansion was a significant historical movement in the United States during the 19th century. It involved the gradual expansion of American settlers and their territories westward, primarily across the North American continent.

The historical context of the Westward expansion was shaped by several key factors. One significant factor was the idea of manifest destiny, a belief that it was the nation's destiny and duty to expand across the continent. This ideology fueled a sense of national pride and a desire for territorial expansion. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803, in which the United States acquired a vast amount of land from France, set the stage for the Westward expansion. This massive acquisition provided the opportunity for further exploration, settlement, and the extension of American influence. The Westward expansion was also influenced by economic factors. The discovery of valuable resources such as gold, silver, and fertile land in the West attracted settlers seeking new opportunities and wealth. The promise of economic prosperity and the allure of land ownership played a significant role in motivating people to venture westward. Additionally, political factors contributed to the Westward expansion. The desire to maintain a balance of power between free and slave states, as well as the notion of "American exceptionalism," spurred the expansion into new territories and the subsequent admission of new states to the Union.

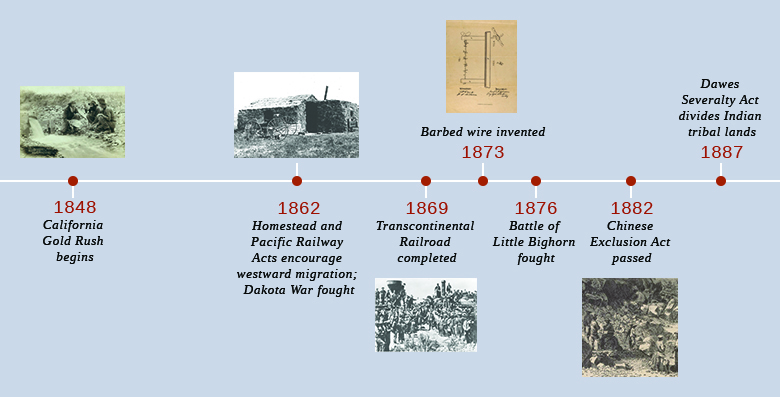

Louisiana Purchase (1803): The acquisition of a vast territory from France doubled the size of the United States, opening up opportunities for westward expansion and settlement. Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806): President Thomas Jefferson commissioned Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore and map the newly acquired western lands, paving the way for future migration and understanding of the region. Oregon Trail (1836-1869): The Oregon Trail became a vital route for pioneers seeking a new life in the Oregon Territory. Thousands traveled this arduous path, enduring hardships and dangers along the way. Texas Annexation (1845): Texas, previously an independent republic, was admitted as a state, fueling tensions with Mexico and eventually leading to the Mexican-American War. California Gold Rush (1848-1855): The discovery of gold in California attracted a massive influx of prospectors from around the world, dramatically accelerating westward migration and shaping the development of the region. Homestead Act (1862): The Homestead Act offered free land to settlers who were willing to develop and cultivate it, encouraging westward migration and the establishment of farming communities. Transcontinental Railroad (1869): The completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad connected the eastern and western coasts of the United States, facilitating trade, travel, and further settlement in the West.

Thomas Jefferson: As the third President of the United States, Jefferson played a pivotal role in the Westward expansion by spearheading the Louisiana Purchase, which greatly expanded American territory. John O'Sullivan: Coined the term "manifest destiny," O'Sullivan advocated for the belief that it was America's divine mission to expand westward and spread democracy and American values. Jedediah Smith: A fur trapper and explorer, Smith played a crucial role in expanding American knowledge of the West. He explored vast territories, including the Great Basin and the California coast. Brigham Young: After the murder of Joseph Smith, Young led the Mormons on a perilous journey westward and established settlements, including Salt Lake City, in present-day Utah. John Sutter: Sutter's Fort, established by John Sutter in present-day California, became an important stop for settlers heading west during the California Gold Rush. Sacagawea: A Shoshone woman, Sacagawea served as a guide and interpreter during the Lewis and Clark Expedition, contributing to the success of their exploration.

Territorial Expansion: The Westward expansion resulted in the acquisition of vast territories, including the Louisiana Purchase, Oregon Country, and the Mexican Cession. This expansion laid the foundation for the future growth and development of the United States. Economic Transformation: The movement westward brought about significant economic changes. The discovery of valuable resources, such as gold and silver, spurred mining industries and economic booms. The fertile lands of the West also facilitated agricultural expansion, leading to increased food production and economic prosperity. Transportation and Communication: The Westward expansion stimulated the development of transportation and communication networks. The construction of railroads, canals, and roads facilitated trade and travel, connecting distant regions and fostering national unity. Migration and Cultural Exchange: The movement of people westward led to the creation of diverse communities and the blending of cultures. Immigrants from various backgrounds settled in the West, contributing to a rich tapestry of traditions, languages, and customs. Native American Displacement and Conflict: The Westward expansion had devastating consequences for Native American tribes, leading to forced removals, loss of lands, and conflicts. This tragic aspect of the expansion highlights the clash of cultures and the impact of colonialism on indigenous peoples. Shaping of American Identity: The Westward expansion played a vital role in shaping the American identity. It embodied the ideals of manifest destiny, individualism, and rugged frontier spirit. The experiences of pioneers, settlers, and explorers became woven into the fabric of American mythology and the national narrative. Political and Social Issues: The Westward expansion fueled debates and conflicts over issues such as slavery, land rights, and statehood. These tensions ultimately contributed to the outbreak of the American Civil War, highlighting the profound political and social implications of the expansion.

Many Americans viewed the Westward expansion as a symbol of national progress and destiny. They embraced the idea of manifest destiny and believed it was the nation's divine mission to spread democracy, civilization, and American values across the continent. Expansionists saw the acquisition of new territories as an opportunity for economic growth, land ownership, and a chance to escape crowded eastern cities. However, not all Americans supported the Westward expansion. Some believed it violated the rights of Native Americans and led to unnecessary conflicts. Others expressed concerns about the expansion's impact on the balance of power between free and slave states, as it raised questions about the expansion of slavery into new territories. Native American tribes, on the other hand, had varying opinions about the Westward expansion. Some tribes initially formed alliances with American settlers, while others resisted encroachment on their lands. The expansion resulted in the displacement, mistreatment, and loss of Native American lives and cultures, leading to a deep sense of betrayal and grief among indigenous populations. Additionally, many settlers and pioneers who ventured westward were driven by personal motivations, such as seeking economic opportunities, landownership, and a fresh start. Their opinions varied depending on their experiences, the challenges they faced, and their interactions with Native Americans and other settlers.

Literature: "Blood Meridian" by Cormac McCarthy: This novel explores the brutal realities of the Westward expansion, focusing on the violent encounters between settlers, Native Americans, and outlaws along the Texas-Mexico border. "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee" by Dee Brown: This historical account documents the experiences and tragic fates of Native American tribes during the Westward expansion, shedding light on the devastating impact of colonization.

Films and Television: "Dances with Wolves" (1990): Directed by Kevin Costner, this Academy Award-winning film tells the story of a Union Army lieutenant who befriends a Native American tribe while stationed in the Dakota Territory during the Civil War era, highlighting the clash of cultures and the impact of westward movement on Native Americans. "Deadwood" (2004-2006): This critically acclaimed television series depicts the growth of the lawless mining camp of Deadwood, South Dakota, and explores themes of capitalism, greed, and the clash between civilization and the wilderness during the Westward expansion.

1. From 1840 to 1860, an estimated 400,000 settlers journeyed along the Oregon Trail in search of new opportunities and a better life in the West. 2. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 sparked a massive influx of people seeking riches. By 1855, approximately 300,000 gold-seekers, known as "forty-niners," had flocked to California. 3. The Westward expansion led to a significant decline in the buffalo population. In the early 1800s, an estimated 30 million buffalo roamed the Great Plains, but by the late 1880s, hunting and mass slaughter had reduced their numbers to less than 1,000. 4. The Westward expansion resulted in the displacement and forced relocation of Native American tribes. Treaties were often violated, and conflicts such as the Trail of Tears (1838-1839) and the Battle of Little Bighorn (1876) caused significant loss of life and cultural upheaval. 5. Land rushes were exciting events where settlers raced to claim available land. Notable examples include the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889, when over 50,000 people rushed to stake their claims on the newly opened territory. 6. Historian Frederick Jackson Turner declared the frontier "closed" in 1890, as much of the available land had been settled. This marked the end of an era and the beginning of a new phase in American history.

The topic of Westward expansion is highly significant and merits exploration in an essay due to its profound impact on American history and society. Understanding the motivations, events, and consequences of this transformative period provides valuable insights into the shaping of the United States as we know it today. Examining the Westward expansion allows us to delve into the complexities of American expansionism, manifest destiny, and the clash of cultures. It sheds light on the experiences of diverse groups, including Native Americans, settlers, and pioneers, as they navigated the challenges and opportunities presented by westward movement. The essay can explore themes such as land acquisition, territorial disputes, the displacement of indigenous peoples, the growth of cities and industries, and the impact on the environment. Moreover, the Westward expansion continues to resonate in contemporary America. Its legacies are still evident in land ownership, regional identities, cultural diversity, and ongoing debates around issues like resource management and the treatment of Native American communities. By examining this topic, we gain a deeper understanding of the nation's history, its complexities, and the enduring effects of westward expansion on the American identity.

1. Billington, R. A., & Ridge, M. (Eds.). (2001). Westward expansion: A history of the American frontier. University of New Mexico Press. 2. Brown, D. (2017). Bury my heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian history of the American West. Picador. 3. Hine, R. V., Faragher, J. M., & John Mack Faragher (2000). The American West: A new interpretive history. Yale University Press. 4. Hurtado, A. L. (2002). The book of the American West. University of Oklahoma Press. 5. Limerick, P. N. (2000). The legacy of conquest: The unbroken past of the American West. W.W. Norton & Company. 6. Milner II, C. R. (2016). The Oxford history of the American West. Oxford University Press. 7. Parrish, W. E. (Ed.). (2008). The Cambridge companion to the literature of the American West. Cambridge University Press. 8. Paxson, F. L. (1994). The last American frontier. Prentice Hall. 9. White, R. (2011). The middle ground: Indians, empires, and republics in the Great Lakes region, 1650-1815. Cambridge University Press. 10. Worster, D. (2003). Rivers of empire: Water, aridity, and the growth of the American West. Oxford University Press.

Relevant topics

- Civil Rights Movement

- Great Depression

- Manifest Destiny

- American Revolution

- Pearl Harbor

- Industrial Revolution

- Frederick Douglass

- Imperialism

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Bibliography

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Westward Expansion

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 30, 2019 | Original: December 15, 2009

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson purchased the territory of Louisiana from the French government for $15 million. The Louisiana Purchase stretched from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and from Canada to New Orleans, and it doubled the size of the United States. To Jefferson, westward expansion was the key to the nation’s health: He believed that a republic depended on an independent, virtuous citizenry for its survival, and that independence and virtue went hand in hand with land ownership, especially the ownership of small farms. (“Those who labor in the earth,” he wrote, “are the chosen people of God.”) In order to provide enough land to sustain this ideal population of virtuous yeomen, the United States would have to continue to expand. The westward expansion of the United States is one of the defining themes of 19th-century American history, but it is not just the story of Jefferson’s expanding “empire of liberty.” On the contrary, as one historian writes, in the six decades after the Louisiana Purchase, westward expansion “very nearly destroy[ed] the republic.”

Manifest Destiny

By 1840, nearly 7 million Americans–40 percent of the nation’s population–lived in the trans-Appalachian West. Following a trail blazed by Lewis and Clark , most of these people had left their homes in the East in search of economic opportunity. Like Thomas Jefferson , many of these pioneers associated westward migration, land ownership and farming with freedom. In Europe, large numbers of factory workers formed a dependent and seemingly permanent working class; by contrast, in the United States, the western frontier offered the possibility of independence and upward mobility for all. In 1843, one thousand pioneers took to the Oregon Trail as part of the “ Great Emigration .”

Did you know? In 1853, the Gadsden Purchase added about 30,000 square miles of Mexican territory to the United States and fixed the boundaries of the “lower 48” where they are today.

In 1845, a journalist named John O’Sullivan put a name to the idea that helped pull many pioneers toward the western frontier. Westward migration was an essential part of the republican project, he argued, and it was Americans’ “ manifest destiny ” to carry the “great experiment of liberty” to the edge of the continent: to “overspread and to possess the whole of the [land] which Providence has given us,” O’Sullivan wrote. The survival of American freedom depended on it.

Westward Expansion and Slavery

Meanwhile, the question of whether or not slavery would be allowed in the new western states shadowed every conversation about the frontier. In 1820, the Missouri Compromise had attempted to resolve this question: It had admitted Missouri to the union as a slave state and Maine as a free state, preserving the fragile balance in Congress. More important, it had stipulated that in the future, slavery would be prohibited north of the southern boundary of Missouri (the 36º30’ parallel) in the rest of the Louisiana Purchase .

However, the Missouri Compromise did not apply to new territories that were not part of the Louisiana Purchase, and so the issue of slavery continued to fester as the nation expanded. The Southern economy grew increasingly dependent on “King Cotton” and the system of forced labor that sustained it. Meanwhile, more and more Northerners came to believed that the expansion of slavery impinged upon their own liberty, both as citizens–the pro-slavery majority in Congress did not seem to represent their interests–and as yeoman farmers. They did not necessarily object to slavery itself, but they resented the way its expansion seemed to interfere with their own economic opportunity.

Westward Expansion and the Mexican War

Despite this sectional conflict, Americans kept on migrating West in the years after the Missouri Compromise was adopted. Thousands of people crossed the Rockies to the Oregon Territory, which belonged to Great Britain, and thousands more moved into the Mexican territories of California , New Mexico and Texas . In 1837, American settlers in Texas joined with their Tejano neighbors (Texans of Spanish origin) and won independence from Mexico. They petitioned to join the United States as a slave state.

This promised to upset the careful balance that the Missouri Compromise had achieved, and the annexation of Texas and other Mexican territories did not become a political priority until the enthusiastically expansionist cotton planter James K. Polk was elected to the presidency in 1844. Thanks to the maneuvering of Polk and his allies, Texas joined the union as a slave state in February 1846; in June, after negotiations with Great Britain, Oregon joined as a free state.

That same month, Polk declared war against Mexico , claiming (falsely) that the Mexican army had “invaded our territory and shed American blood on American soil.” The Mexican-American War proved to be relatively unpopular, in part because many Northerners objected to what they saw as a war to expand the “slaveocracy.” In 1846, Pennsylvania Congressman David Wilmot attached a proviso to a war-appropriations bill declaring that slavery should not be permitted in any part of the Mexican territory that the U.S. might acquire. Wilmot’s measure failed to pass, but it made explicit once again the sectional conflict that haunted the process of westward expansion.

Westward Expansion and the Compromise of 1850

In 1848, the Treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican War and added more than 1 million square miles, an area larger than the Louisiana Purchase, to the United States. The acquisition of this land re-opened the question that the Missouri Compromise had ostensibly settled: What would be the status of slavery in new American territories? After two years of increasingly volatile debate over the issue, Kentucky Senator Henry Clay proposed another compromise. It had four parts: first, California would enter the Union as a free state; second, the status of slavery in the rest of the Mexican territory would be decided by the people who lived there; third, the slave trade (but not slavery) would be abolished in Washington , D.C.; and fourth, a new Fugitive Slave Act would enable Southerners to reclaim runaway slaves who had escaped to Northern states where slavery was not allowed.

Bleeding Kansas

But the larger question remained unanswered. In 1854, Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed that two new states, Kansas and Nebraska , be established in the Louisiana Purchase west of Iowa and Missouri. According to the terms of the Missouri Compromise, both new states would prohibit slavery because both were north of the 36º30’ parallel. However, since no Southern legislator would approve a plan that would give more power to “free-soil” Northerners, Douglas came up with a middle ground that he called “popular sovereignty”: letting the settlers of the territories decide for themselves whether their states would be slave or free.

Northerners were outraged: Douglas, in their view, had caved to the demands of the “slaveocracy” at their expense. The battle for Kansas and Nebraska became a battle for the soul of the nation. Emigrants from Northern and Southern states tried to influence the vote. For example, thousands of Missourians flooded into Kansas in 1854 and 1855 to vote (fraudulently) in favor of slavery. “Free-soil” settlers established a rival government, and soon Kansas spiraled into civil war. Hundreds of people died in the fighting that ensued, known as “ Bleeding Kansas .”

A decade later, the civil war in Kansas over the expansion of slavery was followed by a national civil war over the same issue. As Thomas Jefferson had predicted, it was the question of slavery in the West–a place that seemed to be the emblem of American freedom–that proved to be “the knell of the union.”

Access hundreds of hours of historical video, commercial free, with HISTORY Vault . Start your free trial today.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

History of Westward Expansion Essay

Introduction, unfair idea of the manifest destiny, were there other options, works cited.

Westward expansion was one of the key periods in the history of the United States of America. It meant significant economic and agricultural growth for white people but it was not the only reason for the expansion; the United States was experiencing certain increase in population and it was getting harder for people to find a job with a decent salary. Thus, moving to the West became a dream for the most ambitious Americans and their desire to achieve it was stronger than any difficulties that frontiersmen were facing. Due to that ambitiousness, the westward expansion was hard to be called a slow process. What is more, not all Americans saw expansion as an advancement. “As Americans poured West, expansion became a source of national political controversy” (Oakes et al. 370).

Manifest destiny was a very popular belief in the 19 th century; according to that, it was an essential destiny of the people from the United States to settle both developed and undeveloped areas of North America. The idea could not be called fair or at least fact-based; according to the manifest destiny, the westward expansion was seen as a naturally determined process conforming both state and moral law. Manifest destiny involved the idea of special virtues and mission of the colonists and it definitely was a powerful weapon of the government.

With help of this idea, it was able to make people believe in a natural necessity of the United States to expand its boundaries. Supporters of the westward expansion believed it to be able to “strengthen it [the country], providing unlimited economic opportunities for future generations” (Haynes par. 4). Moreover, expansionists also used a religion as an instrument as the right to colonize other territories was believed to be given to Americans by God (Oakes et al. 362). When all is said and done, the manifest destiny does not seem to be reasonable as we know what it means to state a superiority of a particular nation over other ones.

Manifest destiny was proclaiming Americans to be God’s favored people who had to perform their mission by means of expansion. In spite of other opinions on the rights and mission of the United States, this idea was successfully incorporated into the vision of the common goal for all Americans. If the United States had not conducted its policy in accordance with the manifest destiny, it might have experienced a certain economic decline caused by a resource scarcity; a swell in population might have yielded to heavy mortality due to the increased fights for the limited resources and the spate of criminal activities caused by high unemployment.

The discussed historical period could be characterized by strong opposition of the colonialists, Mexicans and Native Americans. Thus, it would be interesting for many people to know if there was a way to prevent the conflict, or it was absolutely inevitable. As for the armed conflict between Mexico and the United States, it was caused by strong turf battle after the annexation of Texas that took place in 1845. The conflict was hard to prevent as both aggrieved parties believed to possess priority of territorial supremacy and they saw no solution of the conflict but war. As for the conflict between colonialists and Native Americans, it was likely to be inevitable as the policy of the US government was conducted in accordance with the manifest destiny that supposed invasion to be feasible for performing the mission of the United States.

To conclude, the idea of manifest destiny has played an important role in preparing the country for the westward expansion. As for the latter, it was the way to avoid possible economic decline of the United States and this is why the conflict was inevitable.

Haynes, Sam Walter. Manifest Destiny . PBS. 2006, Web.

Oakes, James, et al. Of the People : A History of the United States , Volume 1: To 1877 . Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, September 1). History of Westward Expansion. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-westward-expansion/

"History of Westward Expansion." IvyPanda , 1 Sept. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-westward-expansion/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'History of Westward Expansion'. 1 September.

IvyPanda . 2020. "History of Westward Expansion." September 1, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-westward-expansion/.

1. IvyPanda . "History of Westward Expansion." September 1, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-westward-expansion/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "History of Westward Expansion." September 1, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/history-of-westward-expansion/.

- Manifest Destiny and the Mexican War of 1846

- The California Gold Rush and the Lewis and Clark Expedition

- Westward Expansion: West as Territory and Metaphor, 1800-1820

- Native Americans in the US of the 19-20th Centuries

- Miꞌkmaq Culture and Its Changes Throughout History

- Taos Pueblo in Native American Culture and History

- Native Americans’ History, Farming, Agriculture

- Native Americans and Colonists' Conflict

National Geographic Education Blog

Bring the spirit of exploration to your classroom.

What is Westward Expansion?

During the 19th Century, more than 1.6 million square kilometers (a million square miles) of land west of the Mississippi River was acquired by the United States federal government. This led to a widespread migration west, referred to as Westward Expansion.

A variety of factors contributed to Westward Expansion, including population growth and economic opportunities on what was presented to be available land.

Manifest Destiny was the belief that it was settlers’ God-given duty and right to settle the North American continent. The notion of Manifest Destiny contributed to why European settlers felt they had a right to claim land, both inhabited and uninhabited, in western North America. They believed it was the white man’s destiny to prosper and spread Christianity by claiming and controlling land.

Manifest Destiny was used to validate the Indian Removal Acts , which occurred in the 1830s. Such legislation forced the removal of Native Americans and helped clear the way for non-native settlers to claim land in the west. When the settlers reached land populated or previously promised to Native Americans, they had no qualms claiming it for their own benefit.

It was not just spiritual prosperity that inspired settlers—outright moneymaking opportunities also motivated Westward Expansion.

Throughout most of the 19th century, there were two main ways to make money west of the Mississippi River: through gold and silver prospecting, and through developing land for agriculture, industry, or urban growth. These two activities often supported each other. In California, for instance, the actuality of “ striking it rich ” was quite short-lived, although immigrants continued to populate the new state and contribute to its agricultural and economic growth well after gold fields were discovered there in 1848.

The idea of “free land” was fairly short-lived as well. By 1890, the U.S. Census reported that there were so many permanent settlements west of the Mississippi that a western “frontier” no longer existed in the United States.

This declaration inspired a young historian, Frederick Jackson Turner, to write his famous “Frontier Thesis.” Turner claimed the “close of the frontier” was symbolic. He asserted that Westward Expansion was the most defining characteristic of American identity to date. With the close of the frontier, he thought, America was that much more “American”—liberated from European customs and attitudes surrounding social class, intellectual culture, and violence.

Many historians criticize the Frontier Thesis, and many reject the idea of an American “frontier” (which Turner described as “the meeting point between savagery and civilization”) entirely. These historians recognize that the “free land” that defined Westward Expansion came at a severe cost to Native American and Spanish-speaking populations, as well as more recent immigrants from Asia (who migrated east, across the Pacific). The Frontier Thesis ignores the development and evolution of these identities almost entirely.

To delve deeper into this complex period of American history, check out our curated resource collection page on Westward Expansion at the National Geographic Resource Library .

Share this:

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from national geographic education blog.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

11. A Nation on the Move: Westward Expansion, 1800–1860: Introduction

After 1800, the United States militantly expanded westward across North America, confident of its right and duty to gain control of the continent and spread the benefits of its “superior” culture. In John Gast’s American Progress (Figure 11.1), the White, blonde figure of Columbia—a historical personification of the United States—strides triumphantly westward with the Star of Empire on her head. She brings education, symbolized by the schoolbook, and modern technology, represented by the telegraph wire. White settlers follow her lead, driving the Native peoples away and bringing successive waves of technological progress in their wake. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the quest for control of the West led to the Louisiana Purchase, the annexation of Texas, and the Mexican-American War. Efforts to seize western territories from Native peoples and expand the republic by warring with Mexico succeeded beyond expectations. Few nations ever expanded so quickly. Yet, this expansion led to debates about the fate of slavery in the West, creating tensions between North and South that ultimately led to the collapse of American democracy and a brutal civil war.

American History to 1865 Copyright © 2022 by LOUIS: The Louisiana Library Network is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Westward Expansion

A significant push toward the west coast of North America began in the 1810s. It was intensified by the belief in manifest destiny, federally issued Indian removal acts, and economic promise. Pioneers traveled to Oregon and California using a network of trails leading west. In 1893 historian Frederick Jackson Turner declared the frontier closed, citing the 1890 census as evidence, and with that, the period of westward expansion ended.

Explore these resources to learn more about what happened between 1810 and 1893, as immigrants, American Indians, United States citizens, and freed slaves moved west.

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Westward Expansion

Westward expansion facts.

Western Territories Of The United States

Indian Removal Act Klondike Gold Rush The Lewis And Clark Expedition War Of 1812 Louisiana Purchase Monroe Doctrine Mexican American War Transcontinental Railroad Homestead Act Kansas-Nebraska Act California Gold Rush Pony Express Battle Of The Alamo The Sand Creek Massacre French And Indian War The Oregon Territory The Oregon Trail Manifest Destiny

Westward Expansion Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about Westward Expansion

» See all Westward Expansion Articles

Westward Expansion summary: The story of the United States has always been one of westward expansion, beginning along the East Coast and continuing, often by leaps and bounds, until it reached the Pacific—what Theodore Roosevelt described as “the great leap Westward.” The acquisition of Hawaii and Alaska, though not usually included in discussions of Americans expanding their nation westward, continued the practices established under the principle of Manifest Destiny.

Even before the American colonies won their independence from Britain in the Revolutionary War, settlers were migrating westward into what are now the states of Kentucky and Tennessee, as well as parts of the Ohio Valley and the Deep South. Westward expansion was greatly aided in the early 19th century by the Louisiana Purchase (1803), which was followed by the Corps of Discovery Expedition that is generally called the Lewis and Clark Expedition; the War of 1812, which secured existing U.S. boundaries and defeated native tribes of the Old Northwest, the region of the Ohio and Upper Mississippi valleys; and the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which forcibly moved virtually all Indians from the Southeast to the present states of Arkansas and Oklahoma, a journey known as the Trail of Tears.

In 1845, a journalist named John O’Sullivan coined the term “Manifest Destiny,” a belief that Americans and American institutions are morally superior and therefore Americans are morally obligated to spread those institutions in order to free people in the Western Hemisphere from European monarchies and to uplift “less civilized” societies, such as the Native American tribes and the people of Mexico. The Monroe Doctrine, adopted in 1823, was the closest America ever came to making Manifest Destiny official policy; it put European nations on notice that the U.S. would defend other nations of the Western Hemisphere from further colonization.

![Emanuel Leutze [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Westward the Course of Empire](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c7/Westward_the_Course_of_Empire.jpg)

The debate over whether the U.S. would continue slavery and expand the area in which it existed or abolish it altogether became increasingly contentious throughout the first half of the 19th century. When the Dred Scott case prevented Congress from passing laws prohibiting slavery and the Kansas-Nebraska act gave citizens of new states the right to decide for themselves whether their state would be free or slaveholding, a wave of settlers rushed to populate the Kansas-Nebraska Territory in order to make their position—pro- or anti-slavery—the dominant one when states were carved out of that territory.

The slavery debate intensified after the Republic of Texas was annexed and new lands acquired as a result of the Mexican War and an agreement with Britain that gave the U.S. sole possession of a portion of the Oregon Territory. The question was only settled by the American Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution prohibiting slavery.

When gold was discovered in California, acquired through the treaty that ended the war with Mexico in 1848, waves of treasure seekers poured into the area. The California Gold Rush was a major factor in expansion west of the Mississippi.

That westward expansion was greatly aided by the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, and passage of the Homestead Act in 1862. That act provided free 160-acre lots in the unsettled West to anyone who would file a claim, live on the land for five years and make improvements to it, including building a dwelling.

From the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 through the migration that resulted from the Transcontinental Railroad and the Homestead Act, Americans engaged in what Theodore Roosevelt termed “the Great Leap Westward.” In less than a century, westward expansion stretched the United States from a handful of states along the Eastern Seaboard all the way to the Pacific. The acquisition of Hawaii and Alaska in the mid-19th century assured westward expansion would continue into the 20th century.

The great losers in this westward wave were the Native American tribes. Displaced as new settlers moved in, they lost their traditional way of life and were relegated to reservations. However, westward expansion provided the United States with vast natural resources and ports along the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf coasts for expanding trade, key elements in creating the superpower America is today.

Timeline of Westward Expansion

Manifest destiny.

Manifest Destiny, a term coined by journalist John O’Sullivan in 1845, was a driving force in 19th century America’s western expansion—the era of U.S. territorial expansion is sometimes called the Age of Manifest Destiny. It was the notion that Americans and the institutions of the U.S. are morally superior and therefore Americans are morally obligated to spread those institutions in order to free people from the perceived tyranny of the European monarchies.

Those beliefs had their origins in the Puritan settlements of New England and the idea that the New World was a new beginning, a chance to correct problems in European government and society—a chance to get things right. Thomas Paine’s 1776 pamphlet, Common Sense, echoed these sentiments in arguing for immediate revolution for independence: “We have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest, purest constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again.”

Manifest Destiny found its greatest support among Democrats, particularly in the northeastern states, where Democratic newspapers preached a utopian dream of spreading American philosophies through nonviolent, noncoercive means. The Whig Party stood in opposition, in part because Whigs feared a growing America would bring with it a spread of slavery. In the case of the Oregon Territory of the Pacific Northwest, for example, Whigs hoped to see an independent republic friendly to the United States but not a part of it, much like the Republic of Texas but without slavery. Democrats wanted that region, which was shared with Great Britain, to become part and parcel of the United States.

Citizens of the Midwestern states were more inclined to active acquisition of territory, rather than relying on noncoercive persuasion. As the century wore on, the South came to view Manifest Destiny as an opportunity to secure more territory for the creation of additional slaveholding states in Central America and the Caribbean.

Although Manifest Destiny’s proponents envisioned the use of nonviolent means to achieve their goals, in practice America’s westward expansion was greatly hastened by a war with Mexico and the violent suppression of the native tribes of the West. It also nearly resulted in war with Great Britain over the Oregon Territory. Learn more about Manifest Destiny .

Louisiana Purchase

In 1803, during President Thomas Jefferson’s administration, the U.S. purchased the Louisiana Territory from France for 50 million francs and the cancellation of debts totaling about 18 million francs. This purchase more than doubled the area of the U.S., removed France entirely from North America, and secured access to New Orleans and transport along the Mississippi River.

Subscribe online and save nearly 40%!!!

France’s Louisiana Territory stretched from New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico northward through the plains into what is today part of Canada, and from the Mississippi River west to the Rocky Mountains—encompassing all or part of 15 states and two Canadian provinces. To secure New Orleans and the trade route to the western territories, Thomas Jefferson sent envoys to purchase New Orleans from France, authorizing them to pay up to $10 million. Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte offered them the entire territory for $15 million.

The constitutionality of the purchase was questioned by many members of the U.S. House of Representatives and even by Jefferson himself, but the security and economic benefits of acquiring the territory won out, and the treaty was ratified on October 20, 1803. Learn more about the Louisiana Purchase

The Corps of Discovery Expedition (Lewis and Clark Expedition)

In late 1802, Jefferson asked his private secretary and military advisor, U.S. Army captain Merriweather Lewis, to plan an expedition through the Louisiana Territory to survey its natural resources, look for “the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent,” and explore the Pacific Northwest in order to discover and claim it before Europeans could. Following the purchase of the Louisiana Territory, finalized in October 1803, Jefferson expanded the mission of the Corps: they would also establish friendly, diplomatic contact with as many of the Native American tribes as possible.

In June 1803, Lewis selected William Clark to be joint commander of the expedition, which would be a corps in the U.S. Army created solely for the expedition. Over the next year, they assembled the Corps of Discovery, a 32-man mixed group of soldiers, skilled civilians, and Lewis’ slave York. Along the way they were joined and aided by a French trader named Toussaint Charboneau and his Shoshone wife, Sacagawea , who gave birth to her first child—named Jean Baptise—on February 11, 1805, just before they departed with the Corps of Discovery on April 7.

After a two and half year journey—the first transcontinental expedition—the Corps of Discovery arrived back in St. Louis on September 23, 1806. They had achieved their objectives, except for the discovery of a Northwest passage via water to the Pacific, although the route that they took became part of the Oregon Trail. Their journey helped open the American west to further exploration and settlement, providing valuable geographical and diplomatic information, giving the U.S. a foothold in the region’s fur trade and making contact with more than 72 Native American tribes. Their scientific data alone provided great advances, including the discovery of 178 new plants and 122 previously unknown species and subspecies of animals. Learn more about the Lewis And Clark Expedition

The War of 1812

The War of 1812 is sometimes called the second war for independence in the U.S. since it was fought against British colonial Canada, which allied Tecumseh, the Shawnee leader of a confederation of native tribes. The Americans initially saw themselves both as defenders of their own country and as liberators of the Canadian settlers, but after the first handful of battles fought on the Canadian border in Michigan and near Niagara Falls, it became clear that the Canadians did not want to be “liberated.” Instead, the war unified the Canadians and is viewed with great patriotic pride to this day.

The war lasted for three years and was fought on three fronts: the lower Canadian Frontier along the Great Lakes, along the border with Upper Canada—now Quebec—and along the Atlantic Coast. Although both countries invaded each other, borders at the end of the war remained the same. There was no clear victor, although both the U.S. and Britain would claim victory. Learn more about the War Of 1812

The War of 1812 did have a clear loser, however: the native tribes. Tecumseh’s confederation was greatly weakened when he was killed on October 5, 1813, at the Battle of the Thames. The confederation completely dissolved at the end of the war when the British retreated back into Canada, breaking their promises to help the tribes defend their lands against U.S. settlement. Prior to the war, many settlers in Ohio, the Indiana Territory, and the Illinois Territory had been threatened by Indian raids; following the war, the tribes were either restricted to ever-shrinking tribal lands or pushed further west, opening new lands for the United States’ westward expansion.

Missouri Compromise and the Kansas-Nebraska Act

When the slaveholding territory of Missouri applied for statehood in 1819, it led to a confrontation between those who favored the expansion of slavery and those who opposed it. An agreement called the Missouri Compromise was passed by Congress two years later, under which states would be admitted in pairs, one slaveholding and one free. Then, in the 1857 Dred Scott case the Supreme Court ruled Congress had no right to prohibit slavery in the territories. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 repealed the law that prohibited slavery above the 36 degrees, 30 minutes longitude line in the old Louisiana Purchase. Territories would henceforth have the right of popular sovereignty, with the settlers of those territories, not Congress, determining if they would permit or prevent slavery within their borders. As a result, settlers on both sides of the issue poured into the Kansas and Nebraska territories, eager to establish their sides’ claim, swelling the population there faster than would have occurred otherwise. Learn more about the Kansas-Nebraska Act

Monroe Doctrine

December 2, 1823, the U.S. adopted the Monroe Doctrine, which stated that America would view any additional colonization in the Western Hemisphere by any European country as an act of aggression. It was the closest that Manifest Destiny would come to being written into official government policy. The doctrine was authored mainly by John Quincy Adams, who saw it as an official moral objection to and opposition of colonialism. Although the doctrine was largely ignored—the U.S. did not have a large army or navy at the time to enforce it—Great Britain supported it, mainly on the seas, as part of Pax Britannica. The Monroe Doctrine implied that the U.S. would expand westward into remaining uncolonized areas—indeed, it necessitated expansion to free or annex European colonies. Learn more about The Monroe Doctrine .

Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears

On May 28, 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law, which formally changed the course of U.S. policy toward the Native American tribes. It had immediate impact on the so-called Five Civilized Tribes—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee-Creek, and Seminole—who had been until then been permitted to act as autonomous nations on their lands the southern U.S. While removal to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) was supposed to be voluntary, the Indian Removal Act allowed the U.S. government to put enormous pressure on the chiefs to signs removal treaties and provided some legal standing to remove them by force.

The first treaty signed following the passage of the act was on September 27, 1830: the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek removed the Choctaws from land east of the Mississippi River in exchange for land in Oklahoma and money. The U.S. Army and the newly formed Bureau of Indian Affairs did not plan the removal well, resulting in delays, food shortages, and exposure to the elements, including a blizzard in Arkansas during the first phase of the tribe’s removal. A Choctaw chief who was interviewed in late 1831 shortly after the blizzard called the removal a “trail of tears and death” for his people—a phrase that was widely repeated in the press and seared into popular memory when it was applied to the brutal removal of the Cherokee from Georgia in 1838.

Georgia had been one of the strongest supporters the Indian Removal Act. Tensions between the Cherokee and settlers had risen to new heights with the discovery of gold near Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1829, leading to the Georgia Gold Rush—the first U.S. gold rush. The state put enormous pressure on the Cherokees to sign a treaty, and a minority of the tribe signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835. After much legal maneuvering, the treaty was narrowly passed in the House and Senate in 1836 without Chief John Ross’s agreement or that of the majority of Cherokees. From May 18 to June 2, 1838, the Cherokees were rounded up into forts as settlers began moving onto their lands. Some Cherokee were forced to live in the forts—little more than stockades—on Army rations for up to five months before starting their journey to Indian Territory. Of the approximately 16,000 Cherokees, more 4,000 died as a result of conditions in the forts, some from the journey—on foot, by wagon and steamboat—to Oklahoma, and some from the consequences of the relocation. About 1,000 Cherokees stayed behind, living on private lands or eking out an existence in the wilderness. Read more about the Indian Removal Act .

The Oregon Trail And Oregon Territory

Disputes over who owned the Oregon Territory nearly led to a third war between the United States and Britain. Ultimately, the question was settled peacefully in a manner that gave the United States clear possession of its first important Pacific port, the area of Puget Sound.

The Oregon Territory stretched from the northern border of California into Alaska, between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific. Britain, Spain, Russia and the U.S. all laid claim to parts or all of it. The U.S. claim was based on the fact that in 1792 Captain Robert Gray had sailed 10 miles up a river, which he named for his vessel, the Columbia. By international principle, his journey gave the United States a claim to all the area drained by the river and its tributaries.

President John Quincy Adams, who dreamed of an America that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific, used threats and diplomacy to end Spain’s claims to the northwest in Transcontinental Treaty, signed in February 1819. This treaty also defined the western borders of the Louisiana Purchase, which had been somewhat vague. The southern borderline would be the 42nd parallel, the top of present California, and would extend across the Rockies to the Pacific.

That left the northern boundary to be defined. The Anglo-American Convention of 1818 between the U.S. and Britain placed the border of British North America (Canada) along the 49th parallel, from the Great Lakes to the Rockies, and opened all of the Oregon Territory to citizens of either country. Under the treaty, the question of dividing that region could be revisited every 10 years. In 1824, Russia abandoned its claims south of the 54 degrees, 40 minutes parallel (54-40).

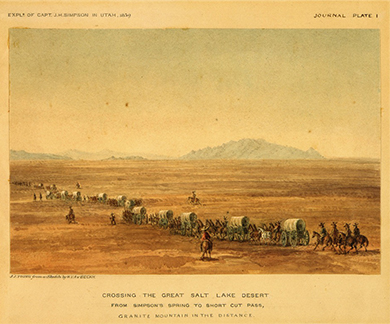

In the 1840s, Americans began their major push west of the Mississippi, into lands that were largely unsettled except by the indigenous tribes. Some went in search of land, some in search of gold and silver, and in the case of the Mormons, in search of religious freedom. Four trails provided their primary pathways: the Santa Fe Trail into the Southwest, the Overland Trail to California, the Mormon Trail to the Great Salt Lake (in the future state of Utah), and the Oregon Trail to the Northwest. Braving harsh weather, attacks by Indians or wild animals, and isolation, their numbers rose into the tens of thousands. Increasingly, Americans talked of the prospect of a transcontinental railroad.

The Oregon Territory took on renewed importance to America’s dream of Manifest Destiny. In the presidential election of 1844, Democrat James K. Polk narrowly won on a platform of national expansion. The youngest president up to that time, Polk tended toward confrontational diplomacy. Britain had long offered to split the Oregon Territory, along the line of the Columbia River. The U.S. preferred the 49th parallel as the boundary. The only area of contention was Puget Sound, which promised its owner a deep-water port for trade with China and Pacific Islands.

In March 1845, the British ambassador spurned Polk’s offer to divide Oregon along the 49th parallel, not even informing his government of the offer. Polk then demanded the whole territory, north to the 54-40 line. In April 1846, Congress authorized Polk to end the joint agreement of 1818. Americans took up the slogan “54-40 or fight,” and war loomed with Britain. The British, however, saw little value in another war with its former colonies in order to protect the interest of the Hudson Bay Company along the Pacific Coast. An agreement was reached that split the Oregon Territory along the 49th parallel (excepting the southern portion of Vancouver Island) in exchange for free navigation along the Columbia for the Hudson Bay Company. Despite the “54-40 or fight” rhetoric, the United States didn’t need war with Britain; a war with Mexico was breaking out.

Mexican-American War

In 1845, during the administration of President John Tyler, the U.S. annexed the Republic of Texas (present-day U.S. state of Texas and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico). Texas had won independence from Mexico in 1836, although Mexico refused to officially acknowledge the republic or its borders. Tyler’s successor, James K. Polk, who had campaigned on a platform that supported Manifest Destiny and expansion, secretly sent diplomat John Slidell to Mexico City to negotiate the purchase of provinces of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México—present-day California, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Texas, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Upon learning Slidell was there to purchase more territory instead of compensate Mexico for Texas, the Mexican government refused to receive him. Slidell wrote to Polk, “We can never get along well with them, until we have given them a good drubbing.” Polk began preparations to declare war based on Slidell’s treatment.

In January 1846, to defend the disputed Texas border and put pressure on Mexican officials to work with Slidell—and perhaps to provoke the Mexicans into a military response—Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor with a small U.S. Army contingent to the north bank of the Rio Grande. Texas and the U.S. government said the Rio Grande was the southern border Texas; Mexico said the border was about 200 miles farther north, along the Nueces.

On April 25, 1846, a patrol under Captain Seth Thornton encountered a force of 2,000 Mexican soldiers; 11 Americans were killed and the rest captured. One wounded man was released by the Mexicans and reported news of the skirmish. Polk received word of the conflict a few days before he addressed Congress. The Thornton Affair, which “shed American blood upon American soil,” provided a more solid footing for his declaration of war, though the veracity of the account is still questioned today.

Some opposed the war on grounds that war should not be used to expand the U.S. Some thought that Polk, a Southerner, wanted to expand slavery and strengthen the influence of slave owners in the federal government. Despite the opposition by Whigs—Polk was a Democrat—the U.S. declared war on Mexico May 13, 1846. Many Whigs continued to question the validity of Polk’s war, including a freshman Congressman from Illinois, the future president Abraham Lincoln.

American success on the battlefield was swift. By August, General Stephen W. Kearny had captured New Mexico—there had been no opposition when he arrived in Santa Fe. Securing California would take longer, although on June 14, 1846, settlers in Alta California began the Big Bear Flag Revolt against the Mexican garrison in Sonoma, without knowing of the declaration of war. Armed resistance by the Californios didn’t end until mid January 1847.

In Northeastern Mexico, Taylor had immediate success in the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. Cumulative U.S. victories threw the Mexican government into turmoil, and in mid-August, its former president Antonio López de Santa Anna saw an opportunity to come out of self-imposed exile in Cuba. He promised the U.S. that he would negotiate a peaceful end to the war and sell New Mexico and California, if given safe passage through the U.S. blockade. Once in Mexico City, however, he reneged on the agreement and seized the presidency. Taylor pushed south into Monterrey, Mexico, in September. After a hard-won victory, Taylor negotiated the surrender of the city and agreed to an eight-week armistice, during which the Mexican troops would be allowed to go free.

Polk, upset by these conciliatory terms and nervous about Taylor becoming a political rival, began to shift Taylor’s men to other commanders to participate in Major General Winfield Scott’s invasion of central Mexico. In January 1847, Santa Anna learned of the U.S. plans and moved to defeat Taylor, and then attack Scott on the coast. Instead, Taylor, with about 500 regulars and some 4,500 volunteers who had not yet seen combat, was able to defeat Santa Anna’s force of about 22,000 men at the Battle of Buena Vista on February 23, 1847. Santa Anna began the long march back to Mexico City.

Scott’s forces captured Veracruz by the end of March 1847 and began the campaign toward Mexico City, which they captured and occupied on September 13, 1847. Although the fighting was largely over, the war didn’t end until February 2, 1848, with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which Mexico renounced all rights to Texas, set the permanent border at the Rio Grande, and ceded land that is now California, Utah, and Nevada, as well as parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming, and Colorado for $15 million. In 1853, James Gadsden, the American minister to Mexico, arranged for the purchase of what is now part of southern Arizona and New Mexico for an additional $15 million. Read more about the Mexican American War .

California Gold Rush

On January 24, 1848, James W. Marshall discovered gold in the American River at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada range northeast of Sacramento. Although he and Sutter tried to keep it a secret, word got out—the first printed notice of the discovery was in the March 15, 1848, San Francisco newspaper The Californian. Not long after, gold was discovered in the Feather and Trinity Rivers, also located northeast of Sacramento.

The first people to rush the gold fields were those already living in California, but as word slowly got out overland and via the port city of San Francisco, people from Oregon, Mexico, Chile, Peru, and Pacific Islands arrived 1848 to find their fortunes. In 1849, there was such a huge influx of gold-seekers—approximately 90,000—that they would be referred to collectively as “forty-niners.” They came over the Rockies from other parts of the U.S. Foreign treasure hunters came by ship from Australia, New Zealand, China and other parts of Asia, and some from Europe, mainly France. It is estimated that by 1855 some 300,000 people had streamed into California hoping to strike it rich. Silver discoveries, including the Comstock Lode in 1859, further drove California’s population growth and development—over the course of the gold rush, California went from a military-occupied part of Mexico to being a U.S. possession to statehood as part of the Compromise of 1850. The port town of San Francisco went from a population of about 1,000 in 1848 to become the eighth largest city in the U.S. in 1890, with a population of almost 300,000. Read more about the California Gold Rush .

Klondike Gold Rush

The Klondike gold rush consisted of the arrival of thousands of prospectors to the Klondike region of Canada as well as Alaska in search of gold. Over 100,000 people set out on the year long journey to the Klondike, with less than one third ever finishing the arduous journey. Only a small percentage of the prospectors found gold, and the rush was soon over. Read more about the Klondike Gold Rush .

Transcontinental Railroad

The first concrete plan for a transcontinental railroad in the United States was presented to Congress by dry-goods merchant Asa Whitney in 1845. Whitney had ridden on newly opened railway lines in England and an 1842–1844 trip to China, which involved a transcontinental trip and the transport of the goods he had bought, further convinced him that the railroad was the future of transport. In 1862, Congress passed the first of five Pacific Railroad Acts that issued government bonds and land grants to the Union Pacific Railroad and the Central Pacific Railroad. The act, based on a bill proposed in 1856 that had been a victim of the political skirmishes over slavery, was considered a war measure that would strengthen the union between the eastern and western states.

The Central Pacific started work in Sacramento, California, in January 8, 1863, but progress was slow due to the resource and labor shortage caused by the Civil War. The Central Pacific faced a labor shortage in the west and relied heavily on Chinese immigrants, who represented over 80 percent of the Central Pacific’s laborers at the height of their employment. The California Gold Rush and the building of the Transcontinental Railroad brought the first great waves of emigration from Asia to America. Learn more about the Transcontinental Railroad

The Union Pacific also faced war shortages as well as incompetence, corruption, and lack of funds; it broke ground in Omaha, Nebraska, on December 12, 1863, but the first rail wasn’t laid until July 10, 1865. Since construction began in earnest after the end of the war, most of the workers on the Union Pacific were Army veterans and Irish immigrants who had come to the U.S. because of the Irish Potato Famine.

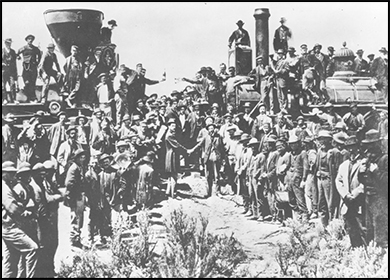

When the railroad was completed on May 10, 1869, with the ceremonial driving of the last spike at Promontory Summit, Utah, it had already facilitated further population of the western states in concert with the Homestead Act. The railroads led to the decline and eventual end to the use of emigrant trails, wagon trains, and stagecoach lines, and a further constriction of the native population and their territories. The supposed Great American Desert—the western Great Plains—was rapidly populated. Telegraph lines were also built along the railroad right of way as the track was laid, replacing the first single-line Transcontinental Telegraph with a multi-line telegraph.

Homestead Act

The Homestead Act of 1862 was intended to make lands opening up in the west available to a wide variety of settlers, not just those who could afford to buy land outright or buy land under the Preemption Act of 1841, which established a lowered land price for squatters who had occupied the land for a minimum of 14 months. In the 1850s, Southerners had opposed three similar efforts to open the west out of fear that western lands would be established as free, non-slaveholding areas. Most of those objecting to such legislation left Congress when the Southern states seceded, allowing the Homestead Act to be passed during the American Civil War. Learn more about the Homestead Act

The Homestead Act required settlers to complete three steps in order to obtain 160-acre lots of surveyed government land. First, an application for a land claim had to be filed, then the homesteader had to live on the land for the next five years and make improvements to it, including building a 12 by 14 shelter. Finally, after five years, the homesteader could file for patent (deed of title) by filing proof of residency and proof of improvements with the local land office, which would then send paperwork with a certificate of eligibility to the General Land Office in Washington, DC, for final approval. The land was free except for a small registration fee. Homesteaders could also apply for patent after a six-month residency and after making small improvements, but they would have to pay $1.25 per acre for the land.

The first homesteader was Daniel Freeman, a Union Army scout scheduled to leave Gage County, Nebraska Territory, on January 1, 1863. On New Years Eve, he met local Land Office officials and persuaded them to open early so he could file a land claim. By the end of the century, more than 80 million acres had been granted to over 480,000 successful homesteaders. In total, about 10 percent of the U.S. was settled because of the Homestead Act, which was in effect until 1976 all states except for Alaska, which repealed the Homestead Act in 1986.

Other Events of Westward Expansion

Pony Express : The Pony Express was a system of horse and riders set up in the mid-1800s to deliver mail and packages. It employed 80 deliverymen and between four and five hundred horses. Read more about Pony Express .

Battle Of The Alamo : The battle of the Alamo was fought from 2/23-6/6/1826 between the United States and Mexico for what is now San Antonio, Texas. It resulted in Mexico taking control. Read more about Battle Of The Alamo .

French Indian War : The French and Indian War was fought from 1756-1763 between the British and the French. It took place in North America and involved many Native American people. Read more about French Indian War .

The Sand Creek Massacre : The Sand Creek Massacre was the brutal attack of Cheyenne Indians consisting mostly of women and children by Union Soldiers that occurred, despite the flying of an American flag to show that they were peaceful and a white flag after the attack began, in Colorado in 1864. . Read more about The Sand Creek Massacre .

Oregon Territory : The Oregon Territory was the name given to the area that became the state of Oregon. It became an official state in February of 1859. Read more about Oregon Territory .

The Oregon Trail : The Oregon Trail is a reference to the path that stretches 2,000 miles across the United States. It was used by thousands of people to populate the western frontier. Read more about The Oregon Trail .

Black Hawk War : The Battle of Black Hawk refers to several conflicts between the United States government and a group of Native Americans called the British Band. They were led by a Sauk warrior named Black Hawk. Read more about Black Hawk War .

The Mountain Meadows Massacre : The Mountain Meadows Massacre refers to an event where militia men from Utah attaché a group of wagon travelers that had made camp for a rest. . Read more about The Mountain Meadows Massacre .

John Jacob Astor : John Jacob Astor was a wealthy merchant and fur trader whose enterprise was played an important role in the westward expansion of the United States. Read more about John Jacob Astor .

O.K. Corral : The O.K. Corral refers to a fight at this corall in Tombstone, Arizona. It’s one of the most famous gunfights in American history and has many films made about it. Read more about the gunfight at the O.K. Corral .

Davy Crockett : Davy Crockett was a famous Tennessee outdoorsman who also served many political offices in North America. He was part of the Texas Revolution and died at the Alamo. Read more about Davy Crockett .

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

17.1: The Westward Spirit

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 2185

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)