What is Theme? A Look at 20 Common Themes in Literature

Sean Glatch | May 7, 2024 | 18 Comments

When someone asks you “What is this book about?” , there are a few ways you can answer. There’s “ plot ,” which refers to the literal events in the book, and there’s “character,” which refers to the people in the book and the struggles they overcome. Finally, there are themes in literature that correspond with the work’s topic and message. But what is theme in literature?

The theme of a story or poem refers to the deeper meaning of that story or poem. All works of literature contend with certain complex ideas, and theme is how a story or poem approaches these ideas.

There are countless ways to approach the theme of a story or poem, so let’s take a look at some theme examples and a list of themes in literature. We’ll discuss the differences between theme and other devices, like theme vs moral and theme vs topic. Finally, we’ll examine why theme is so essential to any work of literature, including to your own writing.

But first, what is theme? Let’s explore what theme is—and what theme isn’t.

Common Themes in Literature: Contents

- Theme Definition

20 Common Themes in Literature

- Theme Examples

Themes in Literature: A Hierarchy of Ideas

Why themes in literature matter.

- Should I Decide the Themes of a Story in Advance?

Theme Definition: What is Theme?

Theme describes the central idea(s) that a piece of writing explores. Rather than stating this theme directly, the author will look at theme using the set of literary tools at their disposal. The theme of a story or poem will be explored through elements like characters , plot, settings , conflict, and even word choice and literary devices .

Theme definition: the central idea(s) that a piece of writing explores.

That said, theme is more than just an idea. It is also the work’s specific vantage point on that idea. In other words, a theme is an idea plus an opinion: it is the author’s specific views regarding the central ideas of the work.

All works of literature have these central ideas and opinions, even if those ideas and opinions aren’t immediate to the reader.

Justice, for example, is a literary theme that shows up in a lot of classical works. To Kill a Mockingbird contends with racial justice, especially at a time when the U.S. justice system was exceedingly stacked against African Americans. How can a nation call itself just when justice is used as a weapon?

By contrast, the play Hamlet is about the son of a recently-executed king. Hamlet seeks justice for his father and vows to kill Claudius—his father’s killer—but routinely encounters the paradox of revenge. Can justice really be found through more bloodshed?

What is theme? An idea + an opinion.

Clearly, these two works contend with justice in unrelated ways. All themes in literature are broad and open-ended, allowing writers to explore their own ideas about these complex topics.

Let’s look at some common themes in literature. The ideas presented within this list of themes in literature show up in novels, memoirs, poems, and stories throughout history.

Theme Examples in Literature

Let’s take a closer look at how writers approach and execute theme. Themes in literature are conveyed throughout the work, so while you might not have read the books in the following theme examples, we’ve provided plot synopses and other relevant details where necessary. We analyze the following:

- Power and Corruption in the novel Animal Farm

- Loneliness in the short story “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”

- Love in the poem “How Do I Love Thee”

Theme Examples: Power and Corruption in the Novel Animal Farm

At its simplest, the novel Animal Farm by George Orwell is an allegory that represents the rise and moral decline of Communism in Russia. Specifically, the novel uncovers how power corrupts the leaders of populist uprisings, turning philosophical ideals into authoritarian regimes.

Most of the characters in Animal Farm represent key figures during and after the Russian Revolution. On an ailing farm that’s run by the negligent farmer Mr. Jones (Tsar Nicholas II), the livestock are ready to seize control of the land. The livestock’s discontent is ripened by Old Major (Karl Marx/Lenin), who advocates for the overthrow of the ruling elite and the seizure of private land for public benefit.

After Old Major dies, the pigs Napoleon (Joseph Stalin) and Snowball (Leon Trotsky) stage a revolt. Mr. Jones is chased off the land, which parallels the Russian Revolution in 1917. The pigs then instill “Animalism”—a system of government that advocates for the rights of the common animal. At the core of this philosophy is the idea that “all animals are equal”—an ideal that, briefly, every animal upholds.

Initially, the Animalist Revolution brings peace and prosperity to the farm. Every animal is well-fed, learns how to read, and works for the betterment of the community. However, when Snowball starts implementing a plan to build a windmill, Napoleon drives Snowball off of the farm, effectively assuming leadership over the whole farm. (In real life, Stalin forced Trotsky into exile, and Trotsky spent the rest of his life critiquing the Stalin regime until he was assassinated in 1940.)

Napoleon’s leadership quickly devolves into demagoguery, demonstrating the corrupting influence of power and the ways that ideology can breed authoritarianism. Napoleon uses Snowball as a scapegoat for whenever the farm has a setback, while using Squealer (Vyacheslav Molotov) as his private informant and public orator.

Eventually, Napoleon changes the tenets of Animalism, starts walking on two legs, and acquires other traits and characteristics of humans. At the end of the novel, and after several more conflicts , purges, and rule changes, the livestock can no longer tell the difference between the pigs and humans.

Themes in Literature: Power and Corruption in Animal Farm

So, how does Animal Farm explore the theme of “Power and Corruption”? Let’s analyze a few key elements of the novel.

Plot: The novel’s major plot points each relate to power struggles among the livestock. First, the livestock wrest control of the farm from Mr. Jones; then, Napoleon ostracizes Snowball and turns him into a scapegoat. By seizing leadership of the farm for himself, Napoleon grants himself massive power over the land, abusing this power for his own benefit. His leadership brings about purges, rule changes, and the return of inequality among the livestock, while Napoleon himself starts to look more and more like a human—in other words, he resembles the demagoguery of Mr. Jones and the abuse that preceded the Animalist revolution.

Thus, each plot point revolves around power and how power is wielded by corrupt leadership. At its center, the novel warns the reader of unchecked power, and how corrupt leaders will create echo chambers and private militaries in order to preserve that power.

Characters: The novel’s characters reinforce this message of power by resembling real life events. Most of these characters represent real life figures from the Russian Revolution, including the ideologies behind that revolution. By creating an allegory around Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, and the other leading figures of Communist Russia’s rise and fall, the novel reminds us that unchecked power foments disaster in the real world.

Literary Devices: There are a few key literary devices that support the theme of Power and Corruption. First, the novel itself is a “satirical allegory.” “ Satire ” means that the novel is ridiculing the behaviors of certain people—namely Stalin, who instilled far-more-dangerous laws and abuses that created further inequality in Russia/the U.S.S.R. While Lenin and Trotsky had admirable goals for the Russian nation, Stalin is, quite literally, a pig.

Meanwhile, “allegory” means that the story bears symbolic resemblance to real life, often to teach a moral. The characters and events in this story resemble the Russian Revolution and its aftermath, with the purpose of warning the reader about unchecked power.

Finally, an important literary device in Animal Farm is symbolism . When Napoleon (Stalin) begins to resemble a human, the novel suggests that he has become as evil and negligent as Mr. Jones (Tsar Nicholas II). Since the Russian Revolution was a rejection of the Russian monarchy, equating Stalin to the monarchy reinforces the corrupting influence of power, and the need to elect moral individuals to posts of national leadership.

Theme Examples: Loneliness in “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”

Ernest Hemingway’s short story “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” is concerned with the theme of loneliness. You can read this short story here . Content warning for mentions of suicide.

There are very few plot points in Hemingway’s story, so most of the story’s theme is expressed through dialogue and description. In the story, an old man stays up late drinking at a cafe. The old man has no wife—only a niece that stays with him—and he attempted suicide the previous week. Two waiters observe him: a younger waiter wants the old man to leave so they can close the cafe, while an older waiter sympathizes with the old man. None of these characters have names.

The younger waiter kicks out the old man and closes the cafe. The older waiter walks to a different cafe and ruminates on the importance of “a clean, well-lighted place” like the cafe he works at.

Themes in Literature: Loneliness in “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”

Hemingway doesn’t tell us what to think about the old man’s loneliness, but he does provide two opposing viewpoints through the dialogue of the waiters.

The younger waiter has the hallmarks of a happy life: youth, confidence, and a wife to come home to. While he acknowledges that the old man is unhappy, he also admits “I don’t want to look at him,” complaining that the old man has “no regard for those who must work.” The younger waiter “did not wish to be unjust,” he simply wanted to return home.

The older waiter doesn’t have the privilege of turning away: like the old man, he has a house but not a home to return to, and he knows that someone may need the comfort of “a clean and pleasant cafe.”

The older waiter, like Hemingway, empathizes with the plight of the old man. When your place of rest isn’t a home, the world can feel like a prison, so having access to a space that counteracts this feeling is crucial. What kind of a place is that? The older waiter surmises that “the light of course” matters, but the place must be “clean and pleasant” too. Additionally, the place should not have music or be a bar: it must let you preserve the quiet dignity of yourself.

Lastly, the older waiter’s musings about God clue the reader into his shared loneliness with the old man. In a stream of consciousness, the older waiter recites traditional Christian prayers with “nada” in place of “God,” “Father,” “Heaven,” and other symbols of divinity. A bartender describes the waiter as “otro locos mas” (translation: another crazy), and the waiter concludes that his plight must be insomnia.

This belies the irony of loneliness: only the lonely recognize it. The older waiter lacks confidence, youth, and belief in a greater good. He recognizes these traits in the old man, as they both share a need for a clean, well-lighted place long after most people fall asleep. Yet, the younger waiter and the bartender don’t recognize these traits as loneliness, just the ramblings and shortcomings of crazy people.

Does loneliness beget craziness? Perhaps. But to call the waiter and old man crazy would dismiss their feelings and experiences, further deepening their loneliness.

Loneliness is only mentioned once in the story, when the young waiter says “He’s [the old man] lonely. I’m not lonely. I have a wife waiting in bed for me.” Nonetheless, loneliness consumes this short story and its older characters, revealing a plight that, ironically, only the lonely understand.

Theme Examples: Love in the Poem “How Do I Love Thee”

Let’s turn towards brighter themes in literature: namely, love in poetry . Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem “ How Do I Love Thee ” is all about the theme of love.

Themes in Literature: Love in “How Do I Love Thee”

Browning’s poem is a sonnet , which is a 14-line poem that often centers around love and relationships. Sonnets have different requirements depending on their form, but between lines 6-8, they all have a volta —a surprising line that twists and expands the poem’s meaning.

Let’s analyze three things related to the poem’s theme: its word choice, its use of simile and metaphor , and its volta.

Word Choice: Take a look at the words used to describe love. What do those words mean? What are their connotations? Here’s a brief list: “soul,” “ideal grace,” “quiet need,” “sun and candle-light,” “strive for right,” “passion,” “childhood’s faith,” “the breath, smiles, tears, of all my life,” “God,” “love thee better after death.”

These words and phrases all bear positive connotations, and many of them evoke images of warmth, safety, and the hearth. Even phrases that are morose, such as “lost saints” and “death,” are used as contrasts to further highlight the speaker’s wholehearted rejoicing of love. This word choice suggests an endless, benevolent, holistic, all-consuming love.

Simile and Metaphor: Similes and metaphors are comparison statements, and the poem routinely compares love to different objects and ideas. Here’s a list of those comparisons:

The speaker loves thee:

- To the depths of her soul.

- By sun and candle light—by day and night.

- As men strive to do the right thing (freely).

- As men turn from praise (purely).

- With the passion of both grief and faith.

- With the breath, smiles, and tears of her entire life.

- Now in life, and perhaps even more after death.

The speaker’s love seems to have infinite reach, flooding every aspect of her life. It consumes her soul, her everyday activities, her every emotion, her sense of justice and humility, and perhaps her afterlife, too. For the speaker, this love is not just an emotion, an activity, or an ideology: it’s her existence.

Volta: The volta of a sonnet occurs in the poem’s center. In this case, the volta is the lines “I love thee freely, as men strive for right. / I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.”

What surprising, unexpected comparisons! To the speaker, love is freedom and the search for a greater good; it is also as pure as humility. By comparing love to other concepts, the speaker reinforces the fact that love isn’t just an ideology, it’s an ideal that she strives for in every word, thought, and action.

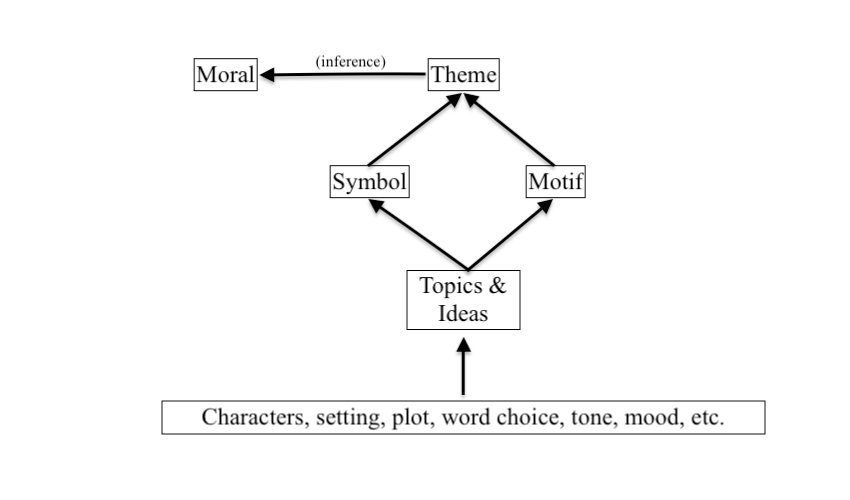

“Theme” is part of a broader hierarchy of ideas. While the theme of a story encompasses its central ideas, the writer also expresses these ideas through different devices.

You may have heard of some of these devices: motif, moral, topic, etc. What is motif vs theme? What is theme vs moral? These ideas interact with each other in different ways, which we’ve mapped out below.

Theme vs Topic

The “topic” of a piece of literature answers the question: What is this piece about? In other words, “topic” is what actually happens in the story or poem.

You’ll find a lot of overlap between topic and theme examples. Love, for instance, is both the topic and the theme of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem “How Do I Love Thee.”

The difference between theme vs topic is: topic describes the surface level content matter of the piece, whereas theme encompasses the work’s apparent argument about the topic.

Topic describes the surface level content matter of the piece, whereas theme encompasses the work’s apparent argument about the topic.

So, the topic of Browning’s poem is love, while the theme is the speaker’s belief that her love is endless, pure, and all-consuming.

Additionally, the topic of a piece of literature is definitive, whereas the theme of a story or poem is interpretive. Every reader can agree on the topic, but many readers will have different interpretations of the theme. If the theme weren’t open-ended, it would simply be a topic.

Theme vs Motif

A motif is an idea that occurs throughout a literary work. Think of the motif as a facet of the theme: it explains, expands, and contributes to themes in literature. Motif develops a central idea without being the central idea itself .

Motif develops a central idea without being the central idea itself.

In Animal Farm , for example, we encounter motif when Napoleon the pig starts walking like a human. This represents the corrupting force of power, because Napoleon has become as much of a despot as Mr. Jones, the previous owner of the farm. Napoleon’s anthropomorphization is not the only example of power and corruption, but it is a compelling motif about the dangers of unchecked power.

Theme vs Moral

The moral of a story refers to the story’s message or takeaway. What can we learn from thinking about a specific piece of literature?

The moral is interpreted from the theme of a story or poem. Like theme, there is no single correct interpretation of a story’s moral: the reader is left to decide how to interpret the story’s meaning and message.

For example, in Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place,” the theme is loneliness, but the moral isn’t quite so clear—that’s for the reader to decide. My interpretation is that we should be much more sympathetic towards the lonely, since loneliness is a quiet affliction that many lonely people cannot express.

Great literature does not tell us what to think, it gives us stories to think about.

However, my interpretation could be miles away from yours, and that’s wonderful! Great literature does not tell us what to think, it gives us stories to think about, and the more we discuss our thoughts and interpretations, the more we learn from each other.

The theme of a story affects everything else: the decisions that characters make, the mood that words and images build, the moral that readers interpret, etc. Recognizing how writers utilize various themes in literature will help you craft stronger, more nuanced works of prose and poetry .

“To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme.” —Herman Melville

Whether a writer consciously or unconsciously decides the themes of their work, theme in literature acts as an organizing principle for the work as a whole. For writers, theme is especially useful to think about in the process of revision: if some element of your poem or story doesn’t point towards a central idea, it’s a sign that the work is not yet finished.

Moreover, literary themes give the work stakes . They make the work stand for something. Remember that our theme definition is an idea plus an opinion. Without that opinion element, a work of literature simply won’t stand for anything, because it is presenting ideas in the abstract without giving you something to react to. The theme of a story or poem is never just “love” or “justice,” it’s the author’s particular spin and insight on those themes. This is what makes a work of literature compelling or evocative. Without theme, literature has no center of gravity, and all the words and characters and plot points are just floating in the ether.

Should I Decide the Theme of a Story or Poem in Advance?

You can, though of course it depends on the actual story you want to tell. Some writers certainly start with a theme. You might decide you want to write a story about themes like love, family, justice, gender roles, the environment, or the pursuit of revenge.

From there, you can build everything else: plot points, characters, conflicts, etc. Examining themes in literature can help you generate some strong story ideas !

Nonetheless, theme is not the only way to approach a creative writing project. Some writers start with plot, others with character, others with conflicts, and still others with just a vague notion of what the story might be about. You might not even realize the themes in your work until after you finish writing it.

You certainly want your work to have a message, but deciding what that message is in advance might actually hinder your writing process. Many writers use their poems and stories as opportunities to explore tough questions, or to arrive at a deeper insight on a topic. In other words, you can start your work with ideas, and even opinions on those ideas, but don’t try to shoehorn a story or poem into your literary themes. Let the work explore those themes. If you can surprise yourself or learn something new from the writing process, your readers will certainly be moved as well.

So, experiment with ideas and try different ways of writing. You don’t have think about the theme of a story right away—but definitely give it some thought when you start revising your work!

Develop Great Themes at Writers.com

As writers, it’s hard to know how our work will be viewed and interpreted. Writing in a community can help. Whether you join our Facebook group or enroll in one of our upcoming courses , we have the tools and resources to sharpen your writing.

Sean Glatch

18 comments.

Sean Glatch,Thank you very much for your discussion on themes. It was enlightening and brought clarity to an abstract and sometimes difficult concept to explain and illustrate. The sample stories and poem were appreciated too as they are familiar to me. High School Language Arts Teacher

Hi Stephanie, I’m so glad this was helpful! Happy teaching 🙂

Wow!!! This is the best resource on the subject of themes that I have ever encountered and read on the internet. I just bookmarked it and plan to use it as a resource for my teaching. Thank you very much for publishing this valuable resource.

Hi Marisol,

Thank you for the kind words! I’m glad to hear this article will be a useful resource. Happy teaching!

Warmest, Sean

builders beams bristol

What is Theme? A Look at 20 Common Themes in Literature | writers.com

Hello! This is a very informative resource. Thank you for sharing.

farrow and ball pigeon

This presentation is excellent and of great educational value. I will employ it already in my thesis research studies.

John Never before communicated with you!

Brilliant! Thank you.

[…] THE MOST COMMON THEMES IN LITERATURE […]

marvellous. thumbs up

Thank you. Very useful information.

found everything in themes. thanks. so much

In college I avoided writing classes and even quit a class that would focus on ‘Huck Finn’ for the entire semester. My idea of hell. However, I’ve been reading and learning from the writers.com articles, and I want to especially thank Sean Glatch who writes in a way that is useful to aspiring writers like myself.

You are very welcome, Anne! I’m glad that these resources have been useful on your writing journey.

Thank you very much for this clear and very easy to understand teaching resources.

Hello there. I have a particular question.

Can you describe the exact difference of theme, issue and subject?

I get confused about these.

I love how helpful this is i will tell my class about it!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Storyteller OS

Superdrive your creativity with some free templates and guides!

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

200 Common Themes in Literature

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is the theme of a story, common themes in literature, universal themes in literature, full list of themes in literature, theme examples in popular novels.

The theme of a novel is the main point of the story and what it’s really about. As a writer, it’s important to identify the theme of your story before you write it.

Themes are not unique to each novel because a theme addresses a common feeling or experience your readers can relate to. If you’re aware of what the common themes are, you’ll have a good idea of what your readers are expecting from your novel .

In this article, we’ll explain what a theme is, and we’ll explore common themes in literature.

The theme of a story is the underlying message or central idea the writer is trying to show through the actions of the main characters. A theme is usually something the reader can relate to, such as love, death, and power.

Your story can have more than one theme, as it might have core themes and minor themes that become more apparent later in the story. A romance novel can have the central theme of love, but the protagonist might have to overcome some self-esteem issues, which present the theme of identity.

Themes are great for adding conflict to your story because each theme presents different issues you could use to develop your characters. For example, a novel with the theme of survival will show the main character facing tough decisions about their own will to survive, potentially at the detriment of someone else they care about.

Sometimes a secondary character will represent the theme in the way they are characterized and the actions they take. Their role is to challenge the protagonist to learn what the story is trying to say about the theme. For example, in a novel about the fear of failure, the antagonist might be a rival in a competition who challenges the protagonist to overcome their fear so they can succeed against them.

It’s important to remember that a theme is not the same as a story’s moral message. A moral is a specific lesson you can teach your readers, whereas a story’s theme is an idea or concept your readers interpret in a way that relates to them.

Write like a bestselling author

Love writing? ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of your stories.

Common literary themes are concepts and central ideas that are relatable to most readers. Therefore, it’s a good idea to use a common theme if you want your novel to appeal to a wide range of readers.

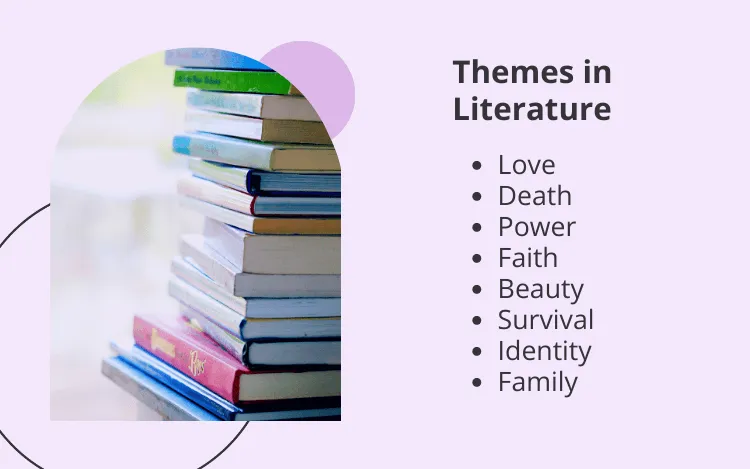

Here’s our list of common themes in literature:

Love : the theme of love appears in novels within many genres, as it can discuss the love of people, pets, objects, and life. Love is a complex concept, so there are still unique takes on this theme being published every day.

Death/Grief : the theme of death can focus on the concept of mortality or how death affects people and how everyone processes grief in their own way.

Power : there are many books in the speculative fiction genres that focus on the theme of power. For example, a fantasy story could center on a ruling family and their internal problems and external pressures, which makes it difficult for them to stay in power.

Faith : the common theme of faith appears in stories where the events test a character’s resolve or beliefs. The character could be religious or the story could be about a character’s faith in their own ability to succeed.

Beauty : the theme of beauty is good for highlighting places where beauty is mostly overlooked by society, such as inner beauty or hard work that goes unnoticed. Some novels also use the theme of beauty to show how much we take beauty for granted.

Survival : we can see the theme of survival in many genres, such as horror, thriller, and dystopian, where the book is about characters who have to survive life-threatening situations.

Identity : there are so many novels that focus on the common theme of identity because it’s something that matters to a lot of readers. Everyone wants to know who they are and where they fit in the world.

Family : the theme of family is popular because families are ripe with opportunities for conflict. The theme of family affects everyone, whether they have one or not, so it’s a relatable theme to use in your story.

Universal themes are simply concepts and ideas that almost all cultures and countries can understand and interpret. Therefore, a universal theme is great for books that are published in several languages.

If you want to write a story you can export to readers all over the world, aim to use a universal theme. The common themes mentioned previously are all universal literary themes, but there are several more you could choose for your story.

Here are some more universal literary themes:

Human nature

Self-awareness

Coming of age

Not all themes are universal or common, but that shouldn’t put you off from using them. If you believe there is something to be said about a particular theme, your book could be the one to say it.

Your book could become popular if the theme of your book addresses a current issue. For example, a theme of art is not as common as love, but in a time when AI developments are making people talk about how AI affects art, it’s a theme people will probably appreciate.

Here’s a full list of themes you can use in your writing:

Abuse of power

American dream

Celebration

Change versus tradition

Chaos and order

Circle of life

Climate change

Colonialism

Common sense

Communication

Companionship

Conservation

Convention and rebellion

Darkness and light

Disappointment

Disillusionment

Displacement

Empowerment

Everlasting love

Forbidden love

Forgiveness

Fulfillment

Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender rights

Good vs evil

Imagination

Immortality

Imperialism

Impossibility

Individuality

Inspiration

Manipulation

Materialism

Nationalism

Not giving up

Opportunity

Peer pressure

Perseverance

Personal development

Relationship

Self-discipline

Self-reliance

Self-preservation

Subjectivity

Surveillance

Totalitarianism

Unconditional love

Unrequited love

Unselfishness

Winning and losing

Working class struggles

If you’ve decided on a literary theme but you’re not sure how to present it in your novel, it’s a good idea to check out how other writers have incorporated it into their novels. We’ve found some examples of themes within popular novels that could help you get started.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Great Gatsby is famous for the theme of the American dream, but it also includes themes of gender, race, social class, and identity. We experience the themes of the novel through the eyes of the narrator, Nick Carraway, who gradually loses his optimism for the American dream as the narrative progresses.

Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

It’s well known that Shakespeare was a connoisseur of the theme of tragedy in his plays, and Romeo and Juliet certainly features tragedy. However, forbidden love and family are the main themes.

Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White

Charlotte’s Web is a classic children’s book that features the themes of death and mortality. From the beginning of the book, the main characters have to come to terms with their own mortality. Charlotte, the spider, does what she can to prevent the slaughter of Wilbur, the pig.

Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

George Orwell’s novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four , focuses on themes of totalitarianism, repression, censorship, and surveillance. The novel is famous for introducing the concept of Big Brother, which has become synonymous with the themes of surveillance and abuse of power.

A Game of Thrones by George R. R. Martin

The fantasy novel, A Game of Thrones , is popular for its complex storylines that present themes of family, power, love, and death. The novel has multiple points of view, which give an insight into how each main character experiences the multiple themes of the story.

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

The Hunger Games is a popular teen novel that focuses on themes of poverty, rebellion, survival, friendship, power, and social class. The novel highlights the horrifying consequences of rebellion, as the teenage competitors have to survive the Hunger Games pageant.

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

Wolf Hall features themes of power, family, faith, and a sense of duty. It’s a historical novel about the life of Oliver Cromwell and how he became the most powerful minister in King Henry VIII’s council.

As you can see, the literary theme of a novel is one of the most important parts, as it gives the reader an instant understanding of what the story is about. Your readers will connect with your novel if you have a theme that is relatable to them.

Some themes are more popular than others, but some gain popularity based on events that are happening in the world. It’s important to consider how relevant your literary theme is to your readers at the time you intend to publish your book.

We hope this list of common themes in literature will help you with your novel writing.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Writing Theme: The Simple Way to Weave a Thematic Message into Your Story

by J. D. Edwin | 0 comments

Want to Become a Published Author? In 100 Day Book, you’ll finish your book guaranteed. Learn more and sign up here.

Does the concept of “theme” confuse you? Do you have trouble writing a strong theme, or weaving a theme into your story? How do you write a theme in literature?

If theme confuses you, you’re not alone. Lots of writers struggle to identify a theme in their book—and many don't even know what thematic message the are communicating through their story until a second or later draft.

The good news is, there are writing tips you can use when weaving a thematic message (or two) into your story. I'd like to share three simple ways to do this.

Why Writing Theme Was Difficult for Me (And How I Overcame This)

I remember the days back in high school English class when I dreaded writing essays on the common themes of books and stories.

There was one particular book that always lingers on my mind, Cold Mountain. I did not understand this book in the least, and when asked about theme, I picked a random sentence that sounded nice and called it a thematic statement. It wasn't one. It was about rocks—not the human condition.

As I grew and developed my skills as a writer, the concept of inserting a theme into a story eluded me.

A theme, after all, is an important story element when writing a novel .

It’s often abstract and vague, and yet it’s supposed to fit every part of your story and tie it all together.

How can you fit this big, confounding idea into your story and keep it consistent throughout, especially when writing a book?

Believe it or not, there is a way!

It wasn’t until the last few years that I finally began to understand how exactly a theme should fit into a story, and that—as it turns out—writing theme isn’t that complicated at all.

When Writing Theme, First Ask Yourself: “What is a Theme?”

A central theme is the main idea or underlying meaning that an author explores in a novel. There can be multiple themes in a story, but each of them says something big about the story's lesson, and what readers can take away from the book.

Does this seem confusing, or ambiguous? Let’s make it simpler:

A theme is an idea that recurs in a story.

That makes a little more sense. But let’s break it down even further.

A theme is a message you keep reminding your reader because it's what the story is really about.

That means a theme is a message that says, “Hey, by the way, just so you remember, this is what I’m trying to tell you. I want you to read this story and remember this .”

You sprinkle this message throughout your story like seasoning on a dish, through description, through dialogue, and through choices made by your characters.

But when writing theme, how do you choose your story's theme(s)? And even after you choose them, how do you weave them into your story's scenes ?

How to Choose Your Story's Theme

Your theme doesn’t have to be complicated. It can be one sentence, a simple phrase, or just one word. In fact, the simpler and more straightforward the theme, the better.

Think of your theme as the one idea you want your readers to keep in the back of their minds during and after reading the story.

For an example, let’s pretend we are going to write a story about an old woman recounting the long life she’s lived.

The theme we want to convey is “passage of time.”

But what does this mean? What will this say about your character experiencing your story, and how can you make this clear to the reader without being overly obvious? What will my story say about the passage of time?

Weaving Theme in Your Story

When writing theme, and then weaving it into your story, begin by identifying words relevant to your theme.

In the example we’ve selected, many words tie to the concept of time, such as:

- Clocks/watches

- Ahead/behind

- Birth/death

Once you identify these words, weave them into your story. This is something that may feel difficult when you first draft your story, but can be done fairly easily in future drafts or during editing.

Let’s take a look at how we can weave this theme of passing time into our story. Imagine this scene:

Doris sat on the creaky bench at the bus stop. The shops down by Main Street had changed from what she remembered. Old McLaren’s barbershop had become a trendy boutique, and the high school where her children attended had been knocked down and rebuilt twice since they graduated. A bike lane had been added to accommodate the increase in cyclers. Biking seemed to have made a comeback. The city bus pulled up with a groan. The tired-looking driver popped the door and gestured to her. “Come on now, I got a schedule to keep.” Doris rose, wincing at her aching bones, and dragged herself onto the bus, where she chose a seat near the back window and watched the city she no longer recognized scroll by outside.

This passage conveys what the story wants to say about time, but something feels weak about it.

It’s loose, like a series of thoughts and descriptions that has a central idea but not quite. To change that, let’s review our theme-relevant words above and take another crack at it.

Here we go:

The ancient bench creaked under Doris as she put her weight on it. It needed a coat of paint badly, but the fast-paced city couldn’t be bothered to pause and refurbish every run-down bus stop. It certainly had time though, Doris thought, to take down and replace all her old haunts. Old McLaren’s barbershop had become a trendy boutique last fall, and the high school where her children attended had been knocked down and rebuilt twice since they graduated at the turn of the century. A bike lane had been added to accommodate the increase in cyclers. Biking was big in the ‘80s, and now the hipsters have brought it back. The city bus pulled up with an exhausted groan. Compared to the bus stop, the old machine looked even worse for wear. The driver with deep lines over his brows popped the door and gestured to her. “Tick-tock, lady. Got a schedule to keep.” Doris rose, wincing at her aching bones. Perhaps she ought to lose weight, she thought to herself, but it was more a flight of fancy than anything – the days when she could still hit the treadmill in between busy work days and long nights partying were far behind her. She dragged herself onto the bus, started to sit in the first available seat, then changed her mind and moved to a quieter spot near the back window, where she settled down heavily and watched the city she no longer recognized scroll by outside.

Does this passage feel more interesting? More emotive? Paints a clearer picture?

The reason is because the theme of time comes through, not only for Doris, but in the poorly maintained bus stop (ancient; contrast against the fast-paced city), the passing of seasons and time (fall, turn of the century), and word choices (tick-tock).

The bus is an old machine, the driver has lines over his brows, the old trend of biking comes full circle, and Doris is no longer the young buck she once was.

Then, instead of sitting in the most convenient seat, she chooses one in the back, a quiet spot that contrasts against her former busy, noisy life of working, gym, and parties.

Every part of this passage now emphasizes time, using words that call to mind clocks, seasons, fast and slow, old and young. Not only does it bring forth the theme and message more strongly, it also makes the story more vivid, tight, and emotional.

Writing theme—specifically the passage of time—in this example takes on new meaning because the context of the story's character, perspective, setting, and conflict all points back to the character's relationship with time itself.

The theme becomes more purposeful because the theme, the passage of time, has a purpose in how the character experiences her surroundings.

Writing With a Theme Makes a Difference

Fitting a theme to your story doesn’t have to be complicated.

By breaking it down to relevant words wrapped around a central idea, you can sprinkle it all throughout your book and reiterate your message to your readers in a subtle, consistent manner.

Writing with a theme can seem daunting, because it feels like everything you write has to fit this one central idea. But the truth is, deciding on a theme can actually help making the writing process easier.

There are a million ways to describe a particular tree your character encounters on their walk. Is it tall? Beautiful? Ugly? Majestic? Inconvenient? Knobbly? But with a theme in mind, you can quickly narrow down the appropriate words to use.

A theme of time, as mentioned above, might lead you to describe the tree as “ancient”, or “a young sapling,” or “bent like grandmother's back.” A different theme, such as young love, might lead you to describe it as “a meeting place of lovers,” or “swaying gently like a lady's hips.”

Instead of being a burden or extra consideration, a theme can work with you and serve as your guide.

And remember, you shouldn't overthink (or overdo) a theme. Plenty of writers don't even know their story's theme until after they've written their first draft.

Still, you need a theme to make a story resonate with your reader after they finish your book. And using the simple tip for writing theme (and weaving it into your scenes) discussed in this post will strengthen your revisions—and the messages making your story memorable and meaningful.

Have you come across themes in your past readings that really resonated with you? Share in the comments below.

First, pick a theme and list out five to ten words relevant to it. Really think about what it would take to integrate these words into a story. Take five minutes to choose your theme and list your words.

Now, take ten minutes to write a blurb that communicates the theme above using the words you listed to inject your message into the story.

When you're done, share your theme and your blurb in the Pro Practice Workshop here . And be sure to support your fellow writers by commenting on what they share, too!

Join 100 Day Book

Enrollment closes May 14 at midnight!

J. D. Edwin

J. D. Edwin is a daydreamer and writer of fiction both long and short, usually in soft sci-fi or urban fantasy. Sign up for her newsletter for free articles on the writer life and updates on her novel, find her on Facebook and Twitter ( @JDEdwinAuthor ), or read one of her many short stories on Short Fiction Break literary magazine .

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

Michael Bjork Writes

Story themes list: 100+ ideas to explore in your novel

Not sure what your story is about? Try this list of themes.

Themes are the universal ideas or topics your story explores.

And there are a lot of them. So many, in fact, the novel or story you’re working on probably already has a few, whether you realize it or not.

But that doesn’t mean your work is done.

Even though your story already has themes, you still need to identify and nurture them into something that resonates with your readers. Otherwise they’ll just sit there beneath the surface — stale, inert, unrealized.

That’s why I put together this story themes list, to help you:

- See and identify themes that might already be in your story, and

- Get a taste of just how many different kinds of themes are out there (because even this long list only scratches the surface).

How to use the list

Before you jump in, there’s something I want to point out.

The themes I included below are subjects and not messages . I explain the difference in my post that answered what is the theme of a story , but to quickly summarize, a subject is the broad topic you explore, while the message is what you’re trying to say about that subject. (Some call this the “thematic concept” and “thematic statement,” respectively.)

For example, “love” might be the subject of your story, but “love is difficult yet worthwhile” might be the message you want to share about the subject.

I didn’t provide messages, because I want you to feel empowered to use your own beliefs to fuel your handling of these themes.

That being said, your story doesn’t need a message if you don’t want it to. Stories can thrive on subjects alone. But as you look through this list and identify the themes that might be in your writing, you should also think about whether there’s anything you want to say about those topics.

All right, that’s all I have to say. Jump on in!

List of 100+ themes worth exploring

Experiences.

- Coming of Age

- Disillusionment

- Loss of Innocence

- Overcoming Adversity

- Self-discovery

Gender & Sexuality

- Gender Identity

- Masculinity

Human Perception

- Perception vs. Reality

- Subjectivity

Mental Health & Neurodiversity

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Natural Forces

- Passage of Time

Politics & Economics

- Conservation

- Nationalism

Religion & Philosophy

- Determinism

- Good vs. Evil

- Metaphysics

- Nature vs. Nurture

- Soul / Consciousness

Social Issues

- Abuse of Power

- Immigration

- Progress & Regress

- Rights of the Oppressed

- Transphobia

- Working Class Struggles

Society & Culture

- Familial Obligations

- Individualism

- Responsibility

Technology & Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Augmented Reality

- Genetic Engineering

- Human Integration with Technology

- Information Privacy

- Weapons of Mass Destruction

Virtues & Vices

- Forgiveness

Want help identifying themes?

If you’re struggling with the concept of theme or how to identify and highlight them in your story, feel free to reach out in the comments below! I’m happy to help.

Follow this blog

Type your email…

Share this:

2 thoughts on “ story themes list: 100+ ideas to explore in your novel ”.

This is a nice list to get inspired! There are so many stories to write about all of these ideas!

Thanks! The crazy thing is this list still only scratches the surface of all the different themes out there. It’s both daunting and liberating to know!

Like Liked by 1 person

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

How To Create A Theme For A Story

Knowing how to create a theme for a story can be a difficult task. Literary themes are a little vague at the best of times and guidance on making and developing them in a story or novel isn’t always clear.

But fear not for help is at hand. In this in-depth guide, we’re going to cover everything you need to know about theme in writing.

We’ll first take a look at the definition of a literary theme. We’ll discuss some examples of popular themes and go over ways of coming up with our own. We’ll also look at useful ways to evoke the theme from an existing story, which can save you a lot of headaches.

Let’s dive in.

What Is A Theme?

A theme takes a hard look at the meaning of things and examines deep-rooted ideas . A story with a theme is a story with a point. It’s only when the writer considers this element, according to master editor Sol Stein, “does he achieve not just an alternative reality, or loosely, an imitation of nature, but true, firm art—fiction as serious thought.”

People take different approaches to creating a theme for a story.

American novelist John Gardner (who had the interesting middle name ‘Champlin’) argued that theme is not imposed on a story, but rather evoked from within it. Initially, it’s intuitive, but finally becomes an intellectual consideration on the part of the writer.

While other writers agree with this approach, it’s not the only one to take when considering the theme. It can be engineered into your story, considered beforehand to give it focus, to help you make out your argument.

A contrasting approach to literary themes comes from one of my favorite creative writing teachers, Lajos Egri. The Hungarian playwright believed that a story couldn’t be written without a premise or theme.

Egri argued that the creative writing theme provides the framework, the structure, the direction. If the writer begins to stray off track, the theme keeps them focused.

But a theme should not consume your story. It’s just one component. Writer and blogger Chuck Wendig describes it as “a drop of poison: subtle, unseen.”

Don’t make it too subtle though, otherwise, it may bypass your readers. Let’s take a look at why a theme in a story is important.

Further Reading – How To Create A Premise

Is A Theme Important To A Story?

As eluded to above, the theme of a story is what it’s about, what it means . It should not be confused with the plot —the two are separate elements, yet linked.

For example, if we look at the classic romance story of Romeo and Juliet , the plot is about two individuals from rival families falling in love and dying as a result of a series of tragic events. But that’s not what the story is about . The themes, in simple terms, look at love, fate, and family, amongst others.

The theme provides the platform for the writer to leave their mark, to put forward their views on a particular topic or idea. It’s the job of the writer to “dig out the fundamental meaning of events by organising the imitation of reality [the story] around some primary question or theme suggested by the character’s concern.”

As we’ll see below, a theme doesn’t have to be based on morality. It can be a more general idea, a topic that reappears throughout a story.

Examples Of Themes

When you seek out examples of literary themes you’ll invariably find lists of single-word suggestions. It’s important to remember that while it’s helpful to summarise themes in this way, they should not be limited to just that one word.

Instead, think of it as an essay question you’d find in school or university. You’re asked to explore or criticise a concept, and in essence, you’re doing the same with your theme .

“Theme can be a broad topical arena, or it can be a specific stance on anything human beings experience in life.”

A theme is not a question, it’s the answer. The process of exploring the theme in your story is the journey your characters go on to come to realise this answer.

Here are a few literary theme examples:

- Alienation – the effects of it, how to fight it.

- Betrayal – how the pain feels, attitude changes to friends and loved ones.

- Coming of Age – the loss of childhood innocence, the shift from childhood to adulthood, or a significant step in personal growth.

- Courage – courage to face adversity, to deal with conflict, the development of it, or the loss of it.

- Discovery – discovering new places, revealing information, inner meaning, inner strength, treasures.

- Death – how to escape it, facing it, dealing with the effects of it.

- Fear – conquering it, coping with it, the crippling effects of it.

- Freedom – losing it, longing for it, striving to achieve it, fighting for it.

- Good Versus Evil – the struggle between the two opposing forces, the triumph of one over the other.

- Justice – the fight for it, injustices, seeking the truth.

- Loss – of life, innocence, possessions, freedoms.

- Love conquers all – love provides the motivation to overcome an obstacle.

- Religion – the effect religion has on individuals, how beliefs shape their lives, extremists such as cults, sin, the afterlife.

- Power – gaining it, handling it, losing it, fighting for it.

So, let’s take a look at how to create a theme for a story.

As we’ve seen above, there’s no right way to go about developing themes. Some writers begin with it and build the story around it while others look to uncover it as the story develops. Here are some essential tips for creating a theme:

- Start with your message – Your story’s theme is essentially the message you want to convey to your readers. Therefore, it’s important to have a clear idea of the central message you want to communicate before you begin writing. This will help you stay focused and ensure that your story has a clear purpose.

- Choose a universal theme – A universal theme is one that resonates with a wide range of readers, regardless of their background or experiences. Examples of universal themes include love, loss, betrayal, redemption, and coming-of-age. Choosing a universal theme will help ensure that your story is relatable and emotionally impactful.

- Use symbolism and imagery – Symbolism and imagery can be powerful tools for reinforcing your story’s theme. Think about objects or images that are associated with your theme and incorporate them into your story. For example, if your theme is about the passage of time, you might use a clock or an hourglass as a symbol.

- Show, don’t tell – Instead of simply stating your theme outright, try to weave it into the story through the actions and experiences of your characters. This will make your theme more engaging and help your readers connect with it on a deeper level.

- Explore multiple perspectives – Your story’s theme can be explored from multiple perspectives, and doing so can add depth and complexity to your narrative. Consider how different characters might experience and interpret your theme, and incorporate these perspectives into your story.

- Tie it all together – Your story’s theme should be present throughout the entire narrative, from beginning to end. Make sure that every element of your story, from the plot to the characters to the setting, ties back to your theme in some way. This will help create a cohesive and satisfying reading experience for your audience.

How To Evoke A Theme From An Existing Story

We’ve covered ways of creating a theme from the beginning, but we’ve not spent much time looking at how to reveal a theme that may already be there in our novel or story.

There are two simple questions you can ask yourself to help evoke the theme of your story. You can ask yourself these questions at any stage of the writing process—beginning, middle, or end, and it’s always helpful to keep them in mind to help you maintain focus.

- What is the point I’m looking to prove?

- What deep-rooted idea is being examined?

Keeping these two simple questions in mind when you’re writing scenes can really help to maintain that focus on what the story is actually about. So easily we can find ourselves distracted by worldbuilding or characterization that we simply lose sight of the point of the story. This writing tip can help.

The Secret Snapshot Approach

This writing technique is one of my favourites. It’s particularly useful for giving your story an emotional edge, an edge so sharp it cuts through to your theme and moves the reader. The theory is simple, the practice is a little trickier.

Master editor Sol Stein utilised this approach when teaching his writing students. He first asked them to think of a snapshot of a memory so private that if that snapshot was a tangible image they wouldn’t carry it in their wallet or purse in case anyone found it, family included.

“Some writers squirm through the process, shifting uncomfortably in their seats. That’s a good sign.”

You can also look to conjure the secret snapshots of other people, ones that you wouldn’t be allowed to see under any circumstance. The bravest writing someone can do is to explore the recesses in which the secret snapshots of their friends, enemies, and themselves are stored.

Writing Exercise: Create A Theme

As an exercise, write down what you see in your most secret snapshot. Be brutally honest. To help, I’ll give my own example. I have a vivid recollection of the day my mum and dad told me they were splitting up. I was about thirteen. I remember crying about not being able to go to football training anymore, which my dad took me to each day after school. Looking back, what I was really upset about was the fact that my life was never going to be the same again, that the image of the life I knew was being shattered before my eyes.

When you’ve come up with your example, ask yourself whether you’d carry your snapshot in your purse or wallet. If yes, think of another. You want to reach deep into your emotional memories and find the most personal. “The best fiction reveals the hidden things we usually don’t want to talk about.”

Once you’ve had some practice uncovering your own, it’s time to apply that process to your characters.

How To Reveal A Theme In Writing

I referred to Chuck Wendig above and how he says that a theme should be subtle. It’s widely agreed that a theme shouldn’t be shoved down the reader’s throat, but one that is apparent should their mind turn to consider it. Yet how do you achieve this subtlety?

Let’s take the theme of nakedness as an example. You could consider adding details to suggest nakedness, for instance, the chipping paint of a wall, characters who show a lot of skin, or the psychological nakedness of a character.

There are instances where it’s fine to be direct with your theme, such as showing instead of telling . For example, how Forrest Gump tells us that ‘life is like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re gonna’ get’, just like the film itself.

Another method you can utilise to reveal a literary theme is to feature ‘counters.’ These are things that contrast with your theme, so for example, with nakedness, you could have a character who always wears two jumpers regardless of the weather.

Learn More About Creative Writing

If you’d like to learn more how creative writing, check out some of these guides below:

- A guide by Oregon State University on themes in literature

If you’d like any more help and support with learning how to create a theme for a story, please contact me .

- Recent Posts

- Mastering Dialogue: The Very Best Tips - January 12, 2024

- The Proven Method Of Writing Short Story Cover Letters - November 10, 2023

- Tips, Advice And Guidance On Writing Villains And Antagonists - November 7, 2023

Related Posts

What Is NaNoWriMo? Get A Complete Understanding

11 Essential Ways To Stop Procrastinating

No thanks, close this box

Definition of Theme

As a literary device, theme refers to the central, deeper meaning of a written work. Writers typically will convey the theme of their work, and allow the reader to perceive and interpret it, rather than overtly or directly state the theme. As readers infer, reflect, and analyze a literary theme, they develop a greater understanding of the work itself and can apply this understanding beyond the literary work as a means of grasping a better sense of the world. Theme is often what creates a memorable and significant experience of a literary work for the reader.

Themes are often subject to the reader’s perception and interpretation. This means that readers may find primary and/or secondary themes in a work of literature that the author didn’t intend to convey. Therefore, theme allows for literature to remain meaningful, “living” works that can be revisited and analyzed in perpetuity by many readers at once or by a single reader across time.

For example, William Shakespeare ’s well-known tragedy , Romeo and Juliet , has been performed and read countless times and by countless people since its publication in 1597:

Come, gentle night ; come, loving, black-browed night; Give me my Romeo; and, when I shall die, Take him and cut him out in little stars, And he will make the face of heaven so fine That all the world will be in love with night

Even those who have not directly heard or read the lines of this play are familiar with its theme of the power of romantic love and its potentially devastating effects.

Common Examples of Literary Themes

Many works of literature share common themes and central ideas. As a literary device, theme allows the author to present and reveal all aspects of human nature and the human condition. This enhances the enjoyment and significance of a literary work for readers by encouraging thought, interpretation, and analysis. Discovery and analysis of theme is also one of the primary reasons that readers return to “classic” literary works that are centuries old. There is no end or expiration to the significance and impact theme can have on readers of literature.

Here are some common examples of literary themes:

- Human versus nature

- Good versus evil

- Coming of age

- Courage and perseverance

- Individual versus society

- Faith versus doubt

- Chaos versus order

- Gender roles

Famous Examples of Disney Movies and Their Themes

Of course, theme is an essential literary device in terms of written works. However, nearly all works of art feature theme as an underlying meaning to be understood and interpreted by the audience . Here are some famous examples of Disney movies and their related themes:

- Peter Pan : out-growing the world of childhood

- Mulan : girls/women can do battle as honorably as boys/men

- The Sword in the Stone : education and courage are stronger than brawn and force

- Cinderella : kindness and inner beauty are rewarded

- Pinocchio : dishonesty leads to trouble

- Aladdin : the best course of action is to be who you are

- The Rescuers : it doesn’t take great size to make a difference

- Snow White : jealousy can lead to cruelty

- The Fox and the Hound : the importance of friendship

- The Little Mermaid : love often requires choices and sacrifices

Difference Between Theme and Subject Matter

Sometimes it can be difficult to determine the difference between the theme and subject matter of a literary work. They are both closely related to each other; however, the subject matter is the topic that is overtly addressed and presented by the writer whereas the theme is the meaning or underlying message that is imparted through the writing.

The subject matter of a written work is what the text is about and is, typically, clearly indicated by the writer. The theme of a literary work reflects why it was written and what the author hopes to convey on a deeper level to the reader without direct statements. A reader may infer and a writer may imply a theme within a literary work. However, the subject matter of a literary work is not inferred by the reader or implied by the writer; it is overtly stated and understood.

For example, in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet , the subject matter is two young people from feuding families who fall deeply in love with each other. One theme of this play, and Romeo and Juliet certainly features several themes, is the power of romantic love and the futility of others to stop it. The subject matter is almost exclusively related to the foundational elements of the story , such as what happens and to which characters. The theme, in contrast , is the lingering meaning and thought left to the reader as a means of reaching a greater understanding of the play itself and the larger concept of love.

Examples of Theme in Literature

As a literary device, the purpose of theme is the main idea or underlying meaning that is explored by a writer in a work of literature. Writers can utilize a combination of elements in order to convey a story’s theme, including setting , plot , characters, dialogue , and more. For certain works of literature, such as fables , the theme is typically a “ moral ” or lesson for the reader. However, more complex works of literature tend to have a central theme that is open to interpretation and reflects a basic aspect of society or trait of humanity. Many longer works of literature, such as novels, convey several themes in order to explore the universality of human nature.

Here are some examples of theme in well-known works of literature:

Example 1: The Yellow Wall-Paper (Charlotte Perkins Gilman)

If a physician of high standing, and one’s own husband, assures friends and relatives that there is really nothing the matter with one but temporary nervous depression – a slight hysterical tendency – what is one to do? My brother is also a physician, and also of high standing, and he says the same thing. • So I take phosphates or phosphites whichever it is, and tonics, and journeys, and air, and exercise, and am absolutely forbidden to “work” until I am well again. Personally, I disagree with their ideas. Personally, I believe that congenial work, with excitement and change, would do me good.

In her short story , Charlotte Perkins Gilman holds forth a revolutionary theme for the time period. The protagonist of the story is kept in a room with sickly yellow wall-paper as a means of “curing” her emotional and mental difficulties. Her husband, brother, and others are committed to keeping her idle. She is even separated from her baby. Rather than allow the narrator any agency over her daily life, they disregard her words and requests for the fact that she is a woman and considered incompetent.

Gilman conveys a theme of rebellion and feminism to the reader as the narrator begins to embrace the “trapped” woman she has become. Therefore, this allows the reader to perceive the narrator as an empowered figure in many ways, as opposed to one that is oppressed or incompetent.

Example 2: Harlem (Langston Hughes)

What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun ? Or fester like a sore— And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over— like a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode?

Hughes’s well-known poem explores the universality of hope and dreams among humans and the devastating legacy of oppression in deferring such hope and dreams. Hughes structures the poem in the form of questions and responses addressing what happens to a dream deferred. This calls on the reader to consider their own dreams as well those of others, which underscores the theme that dreams, and the hope associated with them, is universal–regardless of race, faith, etc.

Tied to this theme is the deferment of dreams, reflecting the devastating consequences of racism and oppression on the hopes of those who are persecuted. Therefore, the underlying theme of the poem that Hughes conveys to the reader is that, though dreams and hopes are universal, the dreams and hopes of certain members of society are put off and postponed due to the oppression of their race.

Example 3: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (James Joyce)

I will tell you what I will do and what I will not do. I will not serve that in which I no longer believe, whether it calls itself my home, my fatherland, or my church: and I will try to express myself in some mode of life or art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can, using for my defense the only arms I allow myself to use — silence , exile , and cunning.

Joyce incorporates several themes in his novel . However, as this passage indicates, the central theme of this literary work is the tension between individual artistic expression the demands of society for conformity. The novel’s main character , Stephen Dedalus, faces conflicting loyalties on one side to his family, church, and country, and on the other side to his life as an artist and dedication to artistic expression.

Through the experiences and conflicts facing the novel’s protagonist, Joyce is able to convey his exploration of the theme of the artist’s role in society. This includes freedom of individual expression versus the constraints of societal conventions. As a result, this theme is imparted to the reader who is able to interpret and analyze aspects of the novel’s central meaning. By the end of Joyce’s novel, the theme culminates in Stephen Dedalus’s decision to isolate himself from family, church, and country, to pursue his art. Therefore, the reader’s inference of the novel’s theme impacts their perception and understanding of the story’s resolution as well as the broader concept of the artist’s role in society.

Related posts:

- Theme for English B

- 10 Different Themes in Taylor Swift Songs

- A Huge List of Common Themes

- Examples of Themes in Popular Songs

- Romeo and Juliet Themes

- Lord of the Flies Themes

- Jane Eyre Themes

Post navigation

Theme Definition

What is theme? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A theme is a universal idea, lesson, or message explored throughout a work of literature. One key characteristic of literary themes is their universality, which is to say that themes are ideas that not only apply to the specific characters and events of a book or play, but also express broader truths about human experience that readers can apply to their own lives. For instance, John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath (about a family of tenant farmers who are displaced from their land in Oklahoma) is a book whose themes might be said to include the inhumanity of capitalism, as well as the vitality and necessity of family and friendship.

Some additional key details about theme:

- All works of literature have themes. The same work can have multiple themes, and many different works explore the same or similar themes.

- Themes are sometimes divided into thematic concepts and thematic statements . A work's thematic concept is the broader topic it touches upon (love, forgiveness, pain, etc.) while its thematic statement is what the work says about that topic. For example, the thematic concept of a romance novel might be love, and, depending on what happens in the story, its thematic statement might be that "Love is blind," or that "You can't buy love . "

- Themes are almost never stated explicitly. Oftentimes you can identify a work's themes by looking for a repeating symbol , motif , or phrase that appears again and again throughout a story, since it often signals a recurring concept or idea.

Theme Pronunciation

Here's how to pronounce theme: theem

Identifying Themes

Every work of literature—whether it's an essay, a novel, a poem, or something else—has at least one theme. Therefore, when analyzing a given work, it's always possible to discuss what the work is "about" on two separate levels: the more concrete level of the plot (i.e., what literally happens in the work), as well as the more abstract level of the theme (i.e., the concepts that the work deals with). Understanding the themes of a work is vital to understanding the work's significance—which is why, for example, every LitCharts Literature Guide uses a specific set of themes to help analyze the text.

Although some writers set out to explore certain themes in their work before they've even begun writing, many writers begin to write without a preconceived idea of the themes they want to explore—they simply allow the themes to emerge naturally through the writing process. But even when writers do set out to investigate a particular theme, they usually don't identify that theme explicitly in the work itself. Instead, each reader must come to their own conclusions about what themes are at play in a given work, and each reader will likely come away with a unique thematic interpretation or understanding of the work.

Symbol, Motif, and Leitwortstil

Writers often use three literary devices in particular—known as symbol , motif , and leitwortstil —to emphasize or hint at a work's underlying themes. Spotting these elements at work in a text can help you know where to look for its main themes.

- Near the beginning of Romeo and Juliet , Benvolio promises to make Romeo feel better about Rosaline's rejection of him by introducing him to more beautiful women, saying "Compare [Rosaline's] face with some that I shall show….and I will make thee think thy swan a crow." Here, the swan is a symbol for how Rosaline appears to the adoring Romeo, while the crow is a symbol for how she will soon appear to him, after he has seen other, more beautiful women.

- Symbols might occur once or twice in a book or play to represent an emotion, and in that case aren't necessarily related to a theme. However, if you start to see clusters of similar symbols appearing in a story, this may mean that the symbols are part of an overarching motif, in which case they very likely are related to a theme.

- For example, Shakespeare uses the motif of "dark vs. light" in Romeo and Juliet to emphasize one of the play's main themes: the contradictory nature of love. To develop this theme, Shakespeare describes the experience of love by pairing contradictory, opposite symbols next to each other throughout the play: not only crows and swans, but also night and day, moon and sun. These paired symbols all fall into the overall pattern of "dark vs. light," and that overall pattern is called a motif.

- A famous example is Kurt Vonnegut's repetition of the phrase "So it goes" throughout his novel Slaughterhouse Five , a novel which centers around the events of World War II. Vonnegut's narrator repeats the phrase each time he recounts a tragic story from the war, an effective demonstration of how the horrors of war have become normalized for the narrator. The constant repetition of the phrase emphasizes the novel's primary themes: the death and destruction of war, and the futility of trying to prevent or escape such destruction, and both of those things coupled with the author's skepticism that any of the destruction is necessary and that war-time tragedies "can't be helped."

Symbol, motif and leitwortstil are simply techniques that authors use to emphasize themes, and should not be confused with the actual thematic content at which they hint. That said, spotting these tools and patterns can give you valuable clues as to what might be the underlying themes of a work.

Thematic Concepts vs. Thematic Statements

A work's thematic concept is the broader topic it touches upon—for instance:

- Forgiveness

while its thematic statement is the particular argument the writer makes about that topic through his or her work, such as:

- Human judgement is imperfect.

- Love cannot be bought.

- Getting revenge on someone else will not fix your problems.

- Learning to forgive is part of becoming an adult.

Should You Use Thematic Concepts or Thematic Statements?

Some people argue that when describing a theme in a work that simply writing a thematic concept is insufficient, and that instead the theme must be described in a full sentence as a thematic statement. Other people argue that a thematic statement, being a single sentence, usually creates an artificially simplistic description of a theme in a work and is therefore can actually be more misleading than helpful. There isn't really a right answer in this debate.

In our LitCharts literature study guides , we usually identify themes in headings as thematic concepts, and then explain the theme more fully in a few paragraphs. We find thematic statements limiting in fully exploring or explaining a the theme, and so we don't use them. Please note that this doesn't mean we only rely on thematic concepts—we spend paragraphs explaining a theme after we first identify a thematic concept. If you are asked to describe a theme in a text, you probably should usually try to at least develop a thematic statement about the text if you're not given the time or space to describe it more fully. For example, a statement that a book is about "the senselessness of violence" is a lot stronger and more compelling than just saying that the book is about "violence."

Identifying Thematic Statements

One way to try to to identify or describe the thematic statement within a particular work is to think through the following aspects of the text: