Case Studies: Successful Teams Built on Strong Communication

Effective communication is the cornerstone of any successful team. Whether it’s a sports team, a corporate department, or a non-profit organization, the ability to convey ideas, collaborate, and resolve conflicts is crucial for achieving shared goals. In this blog post, we will dive into real-world case studies to explore how strong communication played a pivotal role in the success of various teams with these team communication success stories.

Case Study 1: The Apollo 13 Mission

In 1970, the Apollo 13 mission to the moon faced a life-threatening crisis when an oxygen tank exploded . NASA’s ground control and the astronauts onboard had to collaborate flawlessly to bring the crew safely back to Earth. Communication was the key to their survival.

- Clear and Calm Communication : Astronauts Jim Lovell, Fred Haise, and Jack Swigert communicated calmly and precisely with mission control, relaying vital information about their situation.

- Problem Solving Through Dialogue: The teams on Earth and in space worked together to devise ingenious solutions to the spacecraft’s problems, all thanks to open and effective communication.

The result? Against all odds, Apollo 13 safely returned to Earth, showcasing the power of clear communication under pressure.

Case Study 2: Pixar Animation Studios

Pixar Animation Studios is renowned for producing some of the most beloved animated films of our time. Behind every successful Pixar movie is a team of creative minds who prioritize communication.

- Cross-Functional Collaboration: Teams at Pixar consist of artists, storytellers, and technical experts. Regular meetings and open dialogues ensure that everyone’s ideas are heard and integrated into the final product.

- Feedback Culture: Pixar fosters a culture of giving and receiving feedback constructively. This communication style leads to continuous improvement and groundbreaking animation.

Pixar’s commitment to communication has resulted in numerous Academy Awards and timeless classics like “Toy Story” and “Finding Nemo.”

Case Study 3: The Chicago Bulls of the 1990s

The Chicago Bulls dominated the NBA in the 1990s, largely due to the exceptional communication and teamwork led by Michael Jordan and coach Phil Jackson.

- Trust and Cohesion: Jordan and his teammates trusted each other implicitly. This trust was built through open communication, both on and off the court.

- Effective Leadership: Coach Phil Jackson emphasized a collaborative team-first approach, fostering unity and communication among players.

The result? Six NBA championships in eight years, solidifying the Bulls’ place in sports history.

Conclusion – Team Communication Success Stories

These case studies highlight the undeniable connection between strong communication and team success. Whether it’s navigating a space crisis, creating blockbuster animations, or dominating the basketball court, effective communication is the driving force behind achieving remarkable feats as a team.

To achieve similar success in your own endeavors, remember the lessons from these case studies: communicate clearly, collaborate openly, and trust your team members . By doing so, you’ll be well on your way to building a team that can overcome any challenge and achieve greatness.

Communication isn’t just a skill; it’s a superpower that can turn ordinary teams into extraordinary ones.

Thank you for reading, and stay tuned for more insights on effective communication and teamwork!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- 1-800-565-8735

- [email protected]

16 Team Building Case Studies and Training Case Studies

From corporate groups to remote employees and everything in between, the key to a strong business is creating a close-knit team. in this comprehensive case study, we look at how real-world organizations benefited from team building, training, and coaching programs tailored to their exact needs. .

Updated: December 21, 2021

We’re big believers in the benefits of team building , training and development , and coaching and consulting programs. That’s why our passion for helping teams achieve their goals is at the core of everything we do.

At Outback Team Building & Training, our brand promis e is to be recommended , flexible, and fast. Because we understand that when it comes to building a stronger and more close-knit team, there’s no one-size-fits-all formula. Each of our customers have a unique set of challenges, goals, and definitions of success.

And they look to us to support them in three key ways: making their lives easy by taking on the complexities of organizing a team building or training event; acting fast so that they can get their event planned and refocus on all the other tasks they have on their plates, and giving them the confidence that they’ll get an event their team will benefit from – and enjoy.

In this definitive team building case study , we’ll do a deep dive into real-world solutions we provided for our customers.

4 Unique Team Building Events & Training Programs Custom-Tailored for Customer Needs

1. a custom charity event for the bill & melinda gates foundation , 2. how principia built a stronger company culture even with its remote employees working hundreds of miles apart , 3. custom change management program for the royal canadian mint, 4. greenfield global uses express team building to boost morale and camaraderie during a challenging project, 5 virtual team building activities to help remote teams reconnect, 1. how myzone used virtual team building to boost employee morale during covid-19, 2. americorps equips 90 temporary staff members for success with midyear virtual group training sessions, 3. how microsoft’s azure team used virtual team building to lift spirits during the covid-19 pandemic, 4. helping the indiana cpa society host a virtual team building activity that even the most “zoom fatigued” guests would love, 5. stemcell brightens up the holiday season for its cross-departmental team with a virtually-hosted team building activity, 3 momentum-driving events for legacy customers, 1. how a satellite employee “garnered the reputation” as her team’s pro event planner, 2. why plentyoffish continues to choose ‘the amazing race’ for their company retreat, 3. how team building helped microsoft employees donate a truckload of food, 4 successful activities executed on extremely tight timelines, 1. finding a last-minute activity over a holiday, 2. from inquiry to custom call in under 30 minutes, 3. a perfect group activity organized in one business day, 4. delivering team building for charity in under one week.

We know that every team has different needs and goals which is why we are adept at being flexible and have mastered the craft of creating custom events for any specifications.

When the Seattle, Washington -based head office of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation – a world-renowned philanthropic organization – approached us in search of a unique charity event, we knew we needed to deliver something epic. Understanding that their team had effectively done it all when it comes to charity events, it was important for them to be able to get together as a team and give back in new ways .

Our team decided the best way to do this was to create a brand-new event for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation which had never been executed before. We created an entirely new charitable event – Bookworm Builders – for them and their team loved it! It allowed them to give back to their community, collaborate, get creative, and work together for a common goal. Bookworm Builders has since gone on to become a staple activity for tons of other Outback Team Building & Training customers!

To learn more about how it all came together, read the case study: A Custom Charity Event for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation .

Who said hosting an impactful training program means having your full team in the same place at the same time? Principia refused to let distance prevent them from having a great team, so they contacted us to help them find a solution. Their goals were to find better ways of working together and to create a closer-knit company culture among their 20 employees and contractors living in various parts of the country.

We worked with Principia to host an Emotional Intelligence skill development training event customized to work perfectly for their remote team. The result was a massive positive impact for the company. They found they experienced improved employee alignment with a focus on company culture, as well as more emotionally aware and positive day-to-day interactions. In fact, the team made a 100% unanimous decision to bring back Outback for additional training sessions.

To learn more about this unique situation, read the full case study: How Principia Built a Stronger Company Culture Even with its Remote Employees Working Hundreds of Miles Apart .

We know that employee training that is tailored to your organization can make the difference between an effective program and a waste of company time. That’s why our team jumped at the opportunity to facilitate a series of custom development sessions to help the Royal Canadian Mint discover the tools they needed to manage a large change within their organization.

We hosted three custom sessions to help the organization recognize the changes that needed to be made, gain the necessary skills to effectively manage the change, and define a strategy to implement the change:

- Session One: The first session was held in November and focused on preparing over 65 employees for change within the company.

- Session Two: In December, the Mint’s leadership team participated in a program that provided the skills and mindset required to lead employees through change.

- Session Three: The final session in February provided another group of 65 employees with guidance on how to implement the change.

To learn more, read the full case study: Custom Change Management Program for the Royal Canadian Mint .

When Greenfield Global gathered a team of its A-Players to undertake a massive, challenging project, they knew it was important to build rapports among colleagues, encourage collaboration, and have some fun together.

So, we helped them host an Express Clue Murder Mystery event where their team used their unique individual strengths and problem-solving approaches in order to collaboratively solve challenges.

To learn more, read the full case study: Greenfield Global Uses Express Team Building to Boost Morale and Camaraderie During a Challenging Project .

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, we were proud to be able to continue supporting our customers’ goals with virtual team building activities and group training sessions.

With remote work being mandated as self-quarantine requirements are enforced on a global scale, companies began seeking ways to keep their newly-remote teams engaged and ensure morale remained as high as possible.

And MyZone was no exception. When the company found themselves feeling the effects of low employee morale and engagement, they noticed a decrease in productivity and motivation.

To make matters even more difficult, MyZone’s team works remotely with employees all over the world. This physical distancing makes it challenging for them to build a strong rapport, reinforce team dynamics, and boost morale and engagement.

The company was actively searching for an activity to help bring their employees closer together during this challenging time but kept running into a consistent issue: the majority of the team building activities they could find were meant to be done in person.

They reached out to Outback Team Building and Training and we were able to help them achieve their goals with a Virtual Clue Murder Mystery team building activity.

To learn more, read the case study here: How MyZone Used Virtual Team Building to Boost Employee Morale During COVID-19.

AmeriCorps members are dedicated to relieving the suffering of those who have been impacted by natural disasters. And to do so, they rely on the support of a team of temporary staff members who work one-year terms with the organization. These staff focus on disseminating emergency preparedness information and even providing immediate assistance to victims of a disaster.

During its annual midyear training period, AmeriCorps gathers its entire team of temporary staff for a week of professional development seminars aimed at both helping them during their term with the company as well as equipping them with skills they can use when they leave AmeriCorps.

But when the COVID-19 pandemic got underway, AmeriCorps was forced to quickly re-evaluate the feasibility of its midyear training sessions.

That’s when they reached out to Outback. Rather than having to cancel their midyear training entirely, we were able to help them achieve their desired results with four virtual group training sessions: Clear Communication , Performance Management Fundamentals , Emotional Intelligence , and Practical Time Management .

Find all the details in the full case study: AmeriCorps Equips 90 Temporary Staff Members for Success with Midyear Virtual Training Sessions.

With the COVID-19 pandemic taking a significant toll on the morale of its employees, Microsoft’s Azure team knew they were overdue for an uplifting event.

It was critical for their team building event to help staff reconnect and reengage with one another. But since the team was working remotely, the activity needed to be hosted virtually and still be fun, engaging, and light-hearted.

When they reached out to Outback Team Building and Training, we discussed the team’s goals and quickly identified a Virtual Clue Murder Mystery as the perfect activity to help their team get together online and have some fun together.

For more information, check out the entire case study: How Microsoft’s Azure Team Used Virtual Team Building to Lift Spirits During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

The Indiana CPA Society is the go-to resource for the state’s certified public accountants. The organization supports CPAs with everything from continuing education to networking events and even advocacy or potential legislation issues that could affect them.

But as the time approached for one of INCPAS’ annual Thanksgiving event, the Indiana CPA Society’s Social Committee needed to plan a modified, pandemic-friendly event for a group of people who were burnt out my online meetings and experiencing Zoom fatigue.

So, we helped the team with a Self-Hosted Virtual Code Break team building activity that INCPAS staff loved so much, the organization decided to host a second event for its Young Pros and volunteers.

For INCPAS’ Social Committee, the pressure to put on an event that everyone will enjoy is something that’s always on their mind when planning out activities. And their event lived up to their hopes.

For more information, check out the entire case study: Helping the Indiana CPA Society Host a Virtual Team Building Activity That Even the Most “Zoom Fatigued” Guests Would Love .

When Stemcell was looking for a way to celebrate the holidays, lift its team members’ spirits, and help connect cross-departmental teams during the pandemic, they contacted us to help host the perfect team building activity.

They tasked us with finding an event that would help team members connect, get in the holiday spirit, and learn more about the business from one another during the midst of a stressful and challenging time.

So, we helped them host a festive, virtually-hosted Holiday Hijinks team building activity for employees from across the company.

For more information, check out the entire case study: Stemcell Brightens Up the Holiday Season for its Cross-Departmental Team with a Virtually-Hosted Team Building Activity .

We take pride in being recommended by more than 14,000 corporate groups because it means that we’ve earned their trust through delivering impactful results.

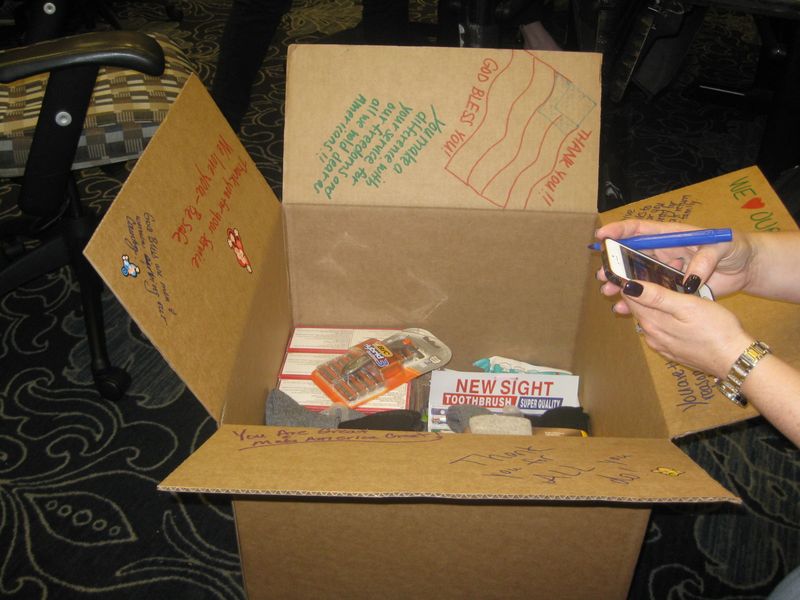

We’ve been in this business for a long time, and we know that not everybody who’s planning a corporate event is a professional event planner. But no matter if it’s their first time planning an event or their tenth, we love to help make our customers look good in front of their team. And when an employee at Satellite Healthcare was tasked with planning a team building event for 15 of her colleagues, she reached out to us – and we set out to do just that!

Our customer needed a collaborative activity that would help a diverse group of participants get to know each other, take her little to no time to plan, and would resonate with the entire group.

With that in mind, we helped her facilitate a Military Support Mission . The event was a huge success and her colleagues loved it. In fact, she has now garnered a reputation as the team member who knows how to put together an awesome team building event.

To learn more, read the case study here: How a Satellite Employee “Garnered the Reputation” as Her Team’s Pro Event Planner .

In 2013, international dating service POF (formerly known as PlentyOfFish) reached out to us in search of an exciting outdoor team building activity that they could easily put to work at their annual retreat in Whistler, B.C . An innovative and creative company, they were in search of an activity that could help their 60 staff get to know each other better. They also wanted the event to be hosted so that they could sit back and enjoy the fun.

The solution? We helped them host their first-ever Amazing Race team building event.

Our event was so successful that POF has now hosted The Amazing Race at their annual retreat for five consecutive years .

To learn more, check out our full case study: Why PlentyOfFish Continues to Choose ‘The Amazing Race’ for Their Company Retreat .

As one of our longest-standing and most frequent collaborators, we know that Microsoft is always in search of new and innovative ways to bring their teams closer together. With a well-known reputation for being avid advocates of corporate social responsibility, Microsoft challenged us with putting together a charitable team building activity that would help their team bond outside the office and would be equal parts fun, interactive, and philanthropic.

We analyzed which of our six charitable team building activities would be the best fit for their needs, and we landed on the perfect one: End-Hunger Games. In this event, the Microsoft team broke out into small groups, tackled challenges like relay races and target practice, and earned points in the form of non-perishable food items. Then, they used their cans and boxes of food to try and build the most impressive structure possible in a final, collaborative contest. As a result, they were able to donate a truckload of goods to the local food bank.

For more details, check out the comprehensive case study: How Team Building Helped Microsoft Employees Donate a Truckload of Food .

Time isn’t always a luxury that’s available to our customers when it comes to planning a great team activity which is why we make sure we are fast, agile, and can accommodate any timeline.

Nothing dampens your enjoyment of a holiday more than having to worry about work – even if it’s something fun like a team building event. But for one T-Mobile employee, this was shaping up to be the case. That’s because, on the day before the holiday weekend, she found out that she needed to organize a last-minute activity for the day after July Fourth.

So, she reached out to Outback Team Building & Training to see if there was anything we could do to help – in less than three business days. We were happy to be able to help offer her some peace of mind over her holiday weekend by recommending a quick and easy solution: a Code Break team building activity. It was ready to go in less than three days, the activity organized was stress-free during her Fourth of July weekend, and, most importantly, all employees had a great experience.

For more details, check out the full story here: Finding a Last-Minute Activity Over a Holiday .

At Outback Team Building & Training, we know our customers don’t always have time on their side when it comes to planning and executing an event. Sometimes, they need answers right away so they can get to work on creating an unforgettable experience for their colleagues.

This was exactly the case when Black & McDonald approached us about a learning and development session that would meet the needs of their unique group, and not take too much time to plan. At 10:20 a.m., the organization reached out with an online inquiry. By 10:50 a.m., they had been connected with one of our training facilitators for a more in-depth conversation regarding their objectives.

Three weeks later, a group of 14 Toronto, Ontario -based Black & McDonald employees took part in a half-day tailor-made training program that was built around the objectives of the group, including topics such as emotional intelligence and influence, communication styles, and the value of vulnerability in a leader.

To learn more about how this event was able to come together so quickly, check out the full story: From Inquiry to Custom Call in Under 30 Minutes .

When Conexus Credit Union contacted us on a Friday afternoon asking if we could facilitate a team building event for six employees the following Monday morning, we said, “Absolutely!”

The team at Conexus Credit Union were looking for an activity that would get the group’s mind going and promote collaboration between colleagues. And we knew just what to recommend: Code Break Express – an activity filled with brainteasers, puzzles, and riddles designed to test the group’s mental strength.

The Express version of Code Break was ideal for Conexus Credit Union’s shorter time frame because our Express activities have fewer challenges and can be completed in an hour or less. They’re self-hosted, so the company’s group organizer was able to easily and efficiently run the activity on their own.

To learn more about how we were able to come together and make this awesome event happen, take a look at our case study: A Perfect Group Activity Organized in One Business Day .

We’ve been lucky enough to work with Accenture – a company which has appeared on FORTUNE’s list of “World’s Most Admired Companies” for 14 years in a row – on a number of team building activities in the past.

The organization approached us with a request to facilitate a philanthropic team building activity for 15 employees. The hitch? They needed the event to be planned, organized, and executed within one week.

Staying true to our brand promise of being fast to act on behalf of our customers, our team got to work planning Accenture’s event. We immediately put to work the experience of our Employee Engagement Consultants, the flexibility of our solutions, and the organization of our event coordinators. And six days later, Accenture’s group was hard at work on a Charity Bike Buildathon , building bikes for kids in need.

To learn more about how we helped Accenture do some good in a short amount of time, read the full case study: Delivering Team Building for Charity in Under One Week .

Learn More About Team Building, Training and Development, and Coaching and Consulting Solutions

For more information about how Outback Team Building & Training can help you host unforgettable team activities to meet your specific goals and needs on virtually any time frame and budget, just reach out to our Employee Engagement Consultants.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

And stay updated, related articles.

The 5 Best Remote Teamwork Tactics to Implement in 2024

How to Create an Engaging And Productive Virtual Internship Program

How to Develop an Employee Volunteer Training Program

From corporate groups to remote employees and everything in between, the key to a strong business is creating a close-knit team. That’s why you need to do team-building sessions as much as you can.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 May 2021

Interpersonal relationships drive successful team science: an exemplary case-based study

- Hannah B. Love ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0011-1328 1 ,

- Jennifer E. Cross ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5582-4192 2 ,

- Bailey Fosdick ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3736-2219 2 ,

- Kevin R. Crooks 2 ,

- Susan VandeWoude 2 &

- Ellen R. Fisher 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 106 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

9156 Accesses

13 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Complex networks

- Science, technology and society

Scientists are increasingly charged with solving complex societal, health, and environmental problems. These systemic problems require teams of expert scientists to tackle research questions through collaboration, coordination, creation of shared terminology, and complex social and intellectual processes. Despite the essential need for such interdisciplinary interactions, little research has examined the impact of scientific team support measures like training, facilitation, team building, and expertise. The literature is clear that solving complex problems requires more than contributory expertise, expertise required to contribute to a field or discipline. It also requires interactional expertise, socialised knowledge that includes socialisation into the practices of an expert group. These forms of expertise are often tacit and therefore difficult to access, and studies about how they are intertwined are nearly non-existent. Most of the published work in this area utilises archival data analysis, not individual team behaviour and assessment. This study addresses the call of numerous studies to use mixed-methods and social network analysis to investigate scientific team formation and success. This longitudinal case-based study evaluates the following question: How are scientific productivity, advice, and mentoring networks intertwined on a successful interdisciplinary scientific team? This study used applied social network surveys, participant observation, focus groups, interviews, and historical social network data to assess this specific team and assessed processes and practices to train new scientists over a 15-year period. Four major implications arose from our analysis: (1) interactional expertise and contributory expertise are intertwined in the process of scientific discovery; (2) team size and interdisciplinary knowledge effectively and efficiently train early career scientists; (3) integration of teaching/training, research/discovery, and extension/engagement enhances outcomes; and, (4) interdisciplinary scientific progress benefits significantly when interpersonal relationships among scientists from diverse disciplines are formed. This case-based study increases understanding of the development and processes of an exemplary team and provides valuable insights about interactions that enhance scientific expertise to train interdisciplinary scientists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Towards understanding the characteristics of successful and unsuccessful collaborations: a case-based team science study

Hannah B. Love, Bailey K. Fosdick, … Ellen R. Fisher

Science facilitation: navigating the intersection of intellectual and interpersonal expertise in scientific collaboration

Amanda E. Cravens, Megan S. Jones, … Hannah B. Love

A framework for developing team science expertise using a reflective-reflexive design method (R2DM)

Gaetano R. Lotrecchiano, L. Michelle Bennett & Yianna Vovides

Introduction

Scientists are increasingly charged with solving complex and large-scale societal, health, and environmental challenges (Read et al., 2016 ; Stokols et al., 2008 ). These systemic problems require interdisciplinary teams to tackle research questions through collaboration, coordination, creation of shared terminology, and complex social and intellectual processes (Barge and Shockley-Zalabak, 2008 ; De Montjoye et al., 2014 ; Fiore, 2008 ). Thus, to successfully approach complex research questions, scientific teams must synthesise knowledge from different disciplines, create a shared terminology, and engage members of a diverse research community (Matthews et al., 2019 ; Read et al., 2016 ). Despite significant time, energy, and money spent on collaboration and interdisciplinary projects, little research has examined the impact of scientific team support measures like training, facilitation, team building, and team performance metrics (Falk-Krzesinski et al., 2011 ; Klein et al., 2009 ).

Studies examining the development of scientific teaming skills that result in successful outcomes are sparse (Fiore, 2008 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Wooten et al., 2014 ). The earliest studies of collaboration in science used bibliometric data to search for predictors of team success such as team diversity, size, geographical proximity, inter-university collaboration, and repeat collaborations (Borner et al., 2010 ; Cummings and Kiesler, 2008 ; Wuchty et al., 2007 ). Building from these studies, current research focuses on team processes. Literature suggests that to successfully frame a scientific problem, a team must also engage emotionally and interact effectively (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ) and that scientific collaboration involve consideration of the process, collaborator, human capital, and other factors that define an scientific collaboration (Bozeman et al., 2013 ; Hall et al., 2019 ; Lee and Bozeman, 2005 ). Similarly, Zhang et al. ( 2020 ) used social network analysis to examine how emotional intelligence is transmitted to team outcomes through team processes. Still more research is needed, and Hall et al. ( 2018 ) called for team science studies that use longitudinal designs and mixed-methods to examine project teams as they develop in order to move beyond bibliometric measures of success and to explore the complex, interacting features in real-world teams.

Fiore ( 2008 ) explained that much of what we know about the science of team science (SciTS), training scientists and team learning in productive team interactions, is anecdotal and not the result of systematic investigation (Fiore, 2008 ). Over a decade later there is still a paucity of research on how scientific teams develop the type of expertise they need to create new knowledge and further scientific discovery (Bammer et al., 2020 ). Bammer et al. ( 2020 ) has identified and defined two types of expertise: (1) contributory expertise, expertise required to make a contribution to a field or discipline (Collins and Evans, 2007 ); and (2) interactional expertise, socialised knowledge that includes socialisation into the practices of an expert group (Bammer et al., 2020 ). These forms of expertise are often tacit, codified by “learning-by-doing,” and augmented from project to project; therefore, they are difficult to measure and rarely documented in literature (Bammer et al., 2020 ).

Wooten et al. ( 2014 ) outlined three types of evaluations—developmental, process, and outcome—needed to understand how teams develop and to provide information about their future success (Wooten et al., 2014 ). A developmental evaluation focuses on the continuous process of team development, and a process evaluation focuses on team interactions, meetings, and engagement (Patton, 2011 ). Both development and process evaluations have the common goal of understanding the team’s future success or failures, also known as the team’s outcomes (e.g., grants, publications, and awards) (Patton, 2011 ). The majority of published work on outcome metrics is evaluated by archival data analysis, not individual team behaviour and assessment (Hall et al., 2018 ). Albeit informative, these studies are based upon limited outcome metrics such as publications and represent only a selective sampling of teams that have achieved success. To collect these three types of evaluation data, it is recommended to engage mixed-methods research such as a combination of social network analysis (SNA), participant observation, surveys, and interviews, although these approaches have not been widely employed (Bennett, 2011 ; Borner et al., 2010 ; Fiore, 2008 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Wooten et al., 2014 ).

A few key studies have provided insight into successful collaboration strategies. Duhigg ( 2016 ) found that successful teams provided psychological safety, had dependable team members, and relied upon clear roles and structures. In addition, successful teams had meaningful goals, and team members felt like they could make an impact through their work on the team (Duhigg, 2016 ). Similarly, Collins ( 2001 ) explained that in business teams, moving from “Good to Great” required more than selecting the right people; the team needed development and training to achieve their goals (Collins, 2001 ). Woolley et al. ( 2010 ) found that it is not collective intelligence that builds the most effective teams, but rather, how teams interact that predicts their success (Woolley et al., 2010 ). The three traits they identified as most associated with team success included even turn-taking, social sensitivity, and proportion female (when women’s representation nears parity with men) (Woolley et al., 2010 ). Finally, Bammer et al. ( 2020 ) recommended creating a knowledge bank to strengthen knowledge about contributary and interactional expertise in scientific literature to solve complex problems. Collectively, these studies argue that the key to collective intelligence is highly reliant on interpersonal relationships to drive team success.

This article reports on a longitudinal case-based study of an exemplary interdisciplinary scientific team that has been successful in typical scientific outputs, including competing for research awards, publishing academic articles, and training and developing scientists. This analysis examines how scientific productivity, advice, and mentoring networks intertwined to promote team success. The study highlights how the team’s processes to train scientists (e.g., developing mentoring and advice networks) have propelled their scientific productivity, fulfilled the University’s land grant mission (i.e., emphasises research/discovery; education/training; and outreach/engagement) and created contributory and interactional expertise on the team. Team dynamics were evaluated by social network surveys, participant observation, focus groups, interviews, and historical social network data over 15 years to develop theory and evaluate complex relationships contributing to team success (Dozier et al., 2014 ; Greenwood, 1993 ).

Case study selection

The [BLIND] Science of team science (SciTS) team consisted of scientists trained in four different disciplines and research administrators. The SciTS team monitored twenty-five interdisciplinary teams at [BLIND] for 5 years from initiation of team formation to identify team dynamics that related to team success. This case is thus presented as part of an ongoing study of the 25 teams, supported by efforts through the [BLINDED] to encourage and enhance collaborative, interdisciplinary research and scholarship. Team outcomes were recorded annually and included extramural awards, publications, presentations, students trained, and training outcomes. An exemplary case-based study is appropriate when the case is unusual, the issues are theoretically important, and there are practical implications (Yin, 2017 ). Further, cases can illustrate examples of expertise and provide guidance to future teams (Bammer et al., 2020 ). An “exemplary team designation” was given to this team by the SciTS evaluators. Metrics used to designate an exemplary team included: team outcomes; highly interdisciplinary research; longevity of the team; fulfilment of all aspects of the land grant mission (research/discovery; education/training; and outreach/engagement); integration of team members; and use of external reviewers.

Social network survey

The exemplary team included Principle Investigators (PIs), postdoctoral researchers (postdocs), graduate students, undergraduate students, and active collaborators external to the University. The entire team was surveyed annually 2015–2019 about the extent and type of collaboration with other team members. In 2015, the team was asked about prior collaborations, and in subsequent years they were asked about additional interactions since joining the team. Possible collaborative activities included research publications, scientific presentations, grant proposals, and serving on student committees. Team members were also asked the types of relationships they had with each team member, including learning, leadership, mentoring, advice, friendship, and having fun (Supplementary 2 ). Data were collected using a voluntary online survey tool (Organisational Network Analysis Surveys). All subjects were identified by name on the social network survey but are not identified in any network diagrams or analyses. SNA software programmes R Studio (R Studio Team, 2020 ) and UCINET (Borgatti et al., 2014 ) were used to analyse data and Visone (Brandes and Wagner, 2011 ) was used to create visualisations. The response rate for the survey was 94% in 2015, 83% in 2016, 95% in 2017, and 81% in 2018. All data collection methods were performed with the informed consent of the participants and followed Institutional Review Board protocol #19-8622H.

Data from the social network survey were combined to create three different network measures: scientific productivity, mentoring, and advice. The scientific productivity network was a combination of four survey measures: research/consulting, grants, publications, and serving on student committees. Scientific productivity represents a form of cognitive or contributory expertise: expertise required to contribute to a field or discipline (Bammer et al., 2020 ; Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ). The mentoring and advice networks were created from social network survey questions: “who is your mentor?” and “who do you go to for advice?”, respectively. Mentor and advice are tacit forms of interactional expertise: socialised knowledge that includes socialisation into the practices of an expert group (Collins and Evans, 2007 ). Other studies have also found a connection between social characteristics of interdisciplinary work and other factors like productivity, career paths, and a group’s ability to exchange information, interact, and explore together (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ).

Social network data were summarised using average degree, sometimes split into indegree and outdegree. Outdegree is a measure of how many team members a given individual reported getting advice, or mentorship, from. Similarly, the indegree of an individual is a measure of how many other team members reported receiving advice, or mentorship, from that person. Average degree is the average number of immediate connections (i.e., indegree plus outdegree) for a person in a network (Giuffre, 2013 ; R. Hanneman and Riddle, 2005 a, 2005 b). To further explore the mentoring and advice networks, we calculated the average degree/outdegree/indegree of postdocs, graduate students, and faculty separately to directly compare demographic groups.

The advice, mentoring, and scientific productivity networks were directly compared using the Pearson correlation between the corresponding network adjacency matrices. We predicted a positive correlation between the advice, mentoring, and scientific productivity matrices. Statistical significance ( p < 0.05) of correlations was assessed with the network permutation-based method Quadratic Assignment Procedure (QAP) (R. A. Hanneman and Riddle, 2005 a, 2005 b).

Historical social network data

A historical network survey was created to determine how the connections in the network formed, developed, and changed from project-to-project. The historical social network was constructed from three forms of data: interviews with the PIs, a historical narrative written by the PIs describing the team formation process, and team rosters that listed the 81 team members since the inception of the team.

Retrospective team survey

A retrospective team survey was administered at the end of the study to determine what skills team members developed and codified through participating on the team, how membership on the team supported members personally and professionally, and their favourite aspects of the team. The survey was sent to 22 members from the 2018 team roster using Qualtrics (Qualtrics Labs, 2005 ) with an 86% response rate.

Two semi-structured, one-hour interviews were conducted with two PIs in 2018 to learn about the history of the team. The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Participant observations

Participant observation was conducted from 2015–2019 at four annual three-day, off-campus retreats and 1–2 additional meetings each year. Students, PIs, external collaborators, and families were all invited to attend the retreats and meetings. Field notes about team interactions were recorded immediately after each interaction. The analytic field notes captured how team members interacted across disciplines, tackled scientific problems, and engaged with others at different career stages. Analysis occurred as field notes were written, during observations, and again during data analysis.

An exemplary team

The SciTS Team identified one team from the larger study and designated it as exemplary based on six (tacit and non-tacit) elements. First, the team had outstanding team outcomes. From 2004–2018, notable accomplishments include 33 extramural awards totalling over $5.6 million, including two large federal awards totalling over $4.5 million; 58 peer-reviewed publications with 39 different universities, 13 state agencies, and 11 other organisations; 141 presentations, 21 graduate students and 15 postdocs trained; and receipt of an [BLIND]institution-wide Interdisciplinary Scholarship Team Award. Participants received many individual honours, including one of the PIs being named to the National Academy of Sciences.

Second, this interdisciplinary team combined scientific expertise from many different backgrounds, including ecologists, wildlife biologists, evolutionary biologists, geneticists, veterinarians, and numerous collaborators. Principal Investigators were housed in five main universities: Colorado State University, University of Wyoming, University of Minnesota, University of California-Davis, and University of Tasmania. They also engaged collaborators from national and international universities, federal, state, and local governmental agencies, veterinary centres, and animal shelters. Collectively, team members represented 39 different universities, 11 federal agencies, 13 state agencies, and 11 other organisations listed on their peer-reviewed publications. The team has published globally with co-authors from every continent but Antarctica.

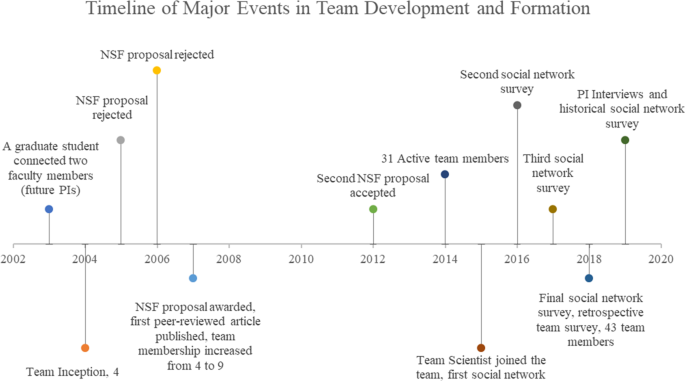

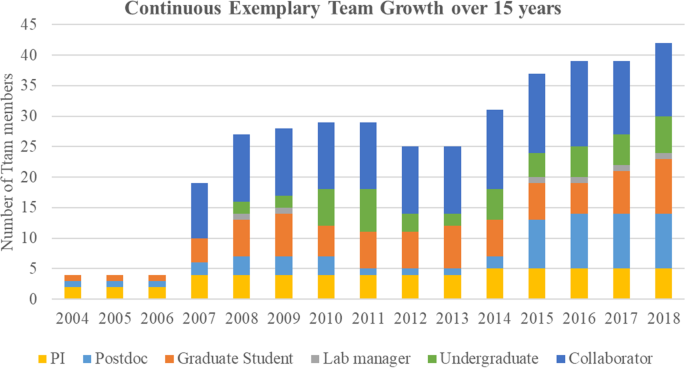

The third element identified was the team’s 15-year history and how they evolved project-to-project (Supplementary Video S1 ). In 2003, a graduate student proposed a collaborative research project between two faculty members who became two of the founding team PIs (Fig. 1 ). The team was formed in 2004 with four members—two faculty PIs, a postdoc, and a Ph.D. student (Fig. 1 ). Initial grant proposals submitted in 2005 and 2006 were not funded; however, in 2007, the team received a large federal research award from the US National Science Foundation (NSF). The team roster increased from four to nine, and a second large expansion occurred after receipt of another NSF award in 2012. By 2014, membership increased to 31 people, and at the end of analysis in 2018, the roster comprised 43 members. Over the course of observation, 81 different individuals, including students, faculty, and collaborators, had participated in research activities supported by the team.

Significant events occurring over 15 years during the development and formation of an exemplary team.

The fourth reason this team was deemed exemplary was because it intertwined the components in the Land Grand mission, including research/discovery, teaching/training, and extension/engagement (Fig. 2 ). The team included undergraduates conducting research and presenting at conferences, graduate students working in multiple labs, and postdocs mentoring all the researchers in the lab. An external advisor said at the end of a retreat, “It’s really cool that students are part of the conversations that are both good/bad/ugly etc. It is not just good. It is not just one-on-one conversations. They hear it all.” A Ph.D. student wrote in the Retrospective Survey about the skills he developed: “I have developed the ability to talk about my research to people outside my field. I have also worked on broadening my understanding of disease ecology as a whole. I have been given the opportunity [to] begin placing my work in the larger framework of ecosystem health.” Faculty also wrote about what they learned, “[I] Learned from leadership of team (especially [blinded], and other PIs) how to develop and conduct research team work well - am using what I am learning to develop new research teams…. how to develop and nurture and respect interpersonal relationships and diversity of opinions. This has been an amazing experience, to be part of a well-functioning team, and to examine why and how that is maintained”

The team grew from 4 members in 2004 to 42 members in 2018. Much of the growth occurred by the addition of students and external collaborators.

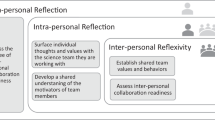

Fifth, the team was effective at onboarding and integrating new members. To do so, they used two key strategies (Fig. 3 ). First, 15 of the students held co-advised graduate research positions. This shared model of mentorship provided students with opportunities to work in multiple labs, collaborate with additional team members, and gain a broader academic experience. A Ph.D. student wrote in the Retrospective Survey about the skills she learned from being a member of the team: “Leadership skills, communicating science to those in other fields, scientific writing skills, technical laboratory skills, interpersonal communication skills, data sharing experience, and many others.” The shared model supported the team’s interdisciplinary mission by providing opportunities to train future scientists to communicate, network, and conduct research across disciplines. Second, as team members developed through participation on the team, they assumed more mature scientific roles. Fourteen members of the team changed positions within the team. Many of these transitions were from undergraduate student to Ph.D. student or Ph.D. student to postdoctoral researcher. In 2012, one postdoc became a PI on the grant.

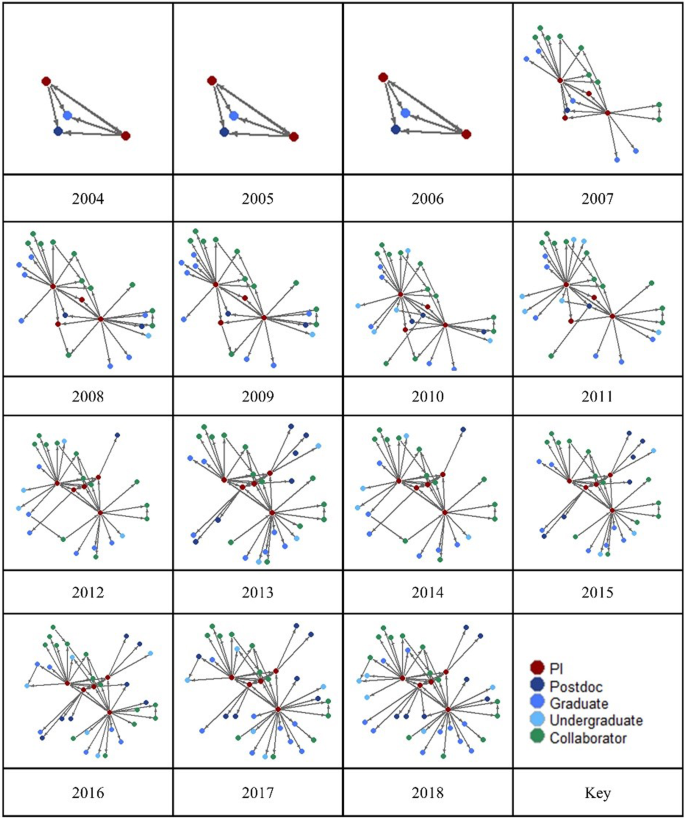

Social network diagrams of team growth and development from 2004–2018. This network reports onboarding and integration of all members, including their primary position when they joined the team. The nodes are sized by average degree (see text). Colours denote different roles on the team.

Finally, the 2018 team retreat included external reviewers. At the end of 2018 team retreat, they were asked if they had any feedback for the team. An external reviewer said: “You can check all of the boxes of a good team.”; “This is a dream team.”; “I am really impressed.”. Another external reviewer said:

The ambitiousness to execute the scope of the project, to have this many PIs, to be able to communicate; the opportunities for new insights; and the opportunities it presents for trainees are rare. There are a lot of people exposed in this. This is a unique experience for someone in training. And it extends to elementary school. I don’t think there are many projects that have this type of scope. I was impressed with just the idea that scientists are taking this across such a great scope and taking on such great questions.

Scientific productivity network

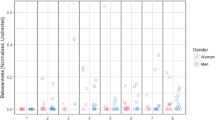

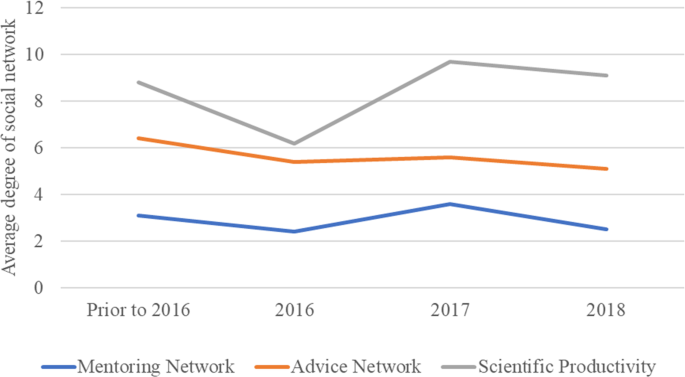

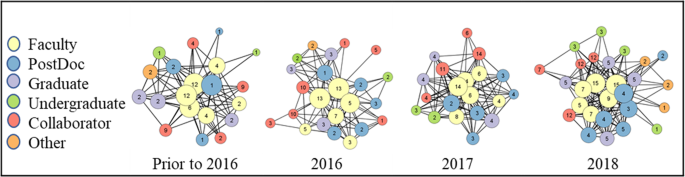

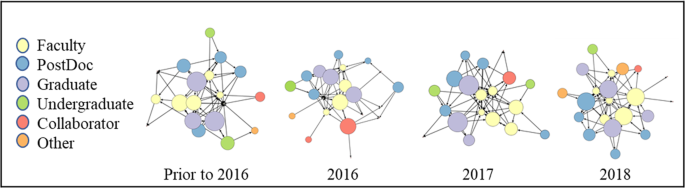

Prior to 2016, the average degree of the scientific productivity network was 8.8 (Fig. 4 ). In 2016, four faculty nodes were in the core of the network, and the periphery nodes included graduate students, postdocs, and external collaborators (Fig. 5 ). The average degree dropped slightly to 6.2 when the team integrated new members and re-formed around new roles and responsibilities on a new grant (Fig. 4 ). In 2017, the average degree peaked at 9.7 (Fig. 4 ) and faculty were still core, but graduate students and postdocs were more central than before (Fig. 5 ). During this time, productivity was at its highest as team members were working together to meet the objectives of a 5-year interdisciplinary NSF award. The network evolved further in 2018; two of the postdoc nodes overlapped with the faculty nodes in the core of the network (Fig. 5 ).

Average degree of social networks diagrams (mentoring, advice, scientific productivity) indicated strong social ties among team members.

Social network measures of productivity (research/consulting, grants, publications, and serving on student committees) were recorded over time. Each node represents a person on the team, and nodes are sized by average degree (see text). Colours denote different roles on the team. The node label indicates the number of years a person has been part of the team.

Mentoring is integral in the collaborative network

Team members reported between an average of 2.4–3.1 mentors (average outdegree) each year on the team (Fig. 6 ). More specifically, graduate students reported 6.0–7.7 mentors, whereas postdocs reported 2.4–3.5 mentors (Table 1 ). Faculty team members reported having an average of 2.2 to 4.3 mentors on the team (Table 1 ), with the highest average outdegree in 2018.

This diagram was created by using participant answers to the social network question, “who is your mentor?” Each circle or node represents a person on the team. The nodes are sized by outdegree to show who reported receiving mentorship. Node size indicates how many mentors an individual reported, and arrows indicate nodes that served as mentors. Colours denote different roles on the team.

The highest indegree for an individual was the lead PI, with an indegree ranging from 13 to 14 each year (i.e., each year, 13–14 team members reported this individual provided mentorship). In response to an interview question about this PIs favourite part of the team, this individual said, “…and of course, I really like the mentorship of the students…They are initially naive, and some people are initially underconfident, but eventually they become fluent in their subject area.” Many students wrote about the mentoring they received from the team. An undergraduate student wrote:

I have improved my communication skills after needing to collaborate with several mentors across different time zones. I’ve also improved willingness to ask questions when I don’t understand a concept. I’ve also learned what concepts I find basic in my field that others outside my discipline are less familiar with.

Faculty also wrote about the mentoring they received, such as, “I continually learn from members in the team and mentorship by the more experienced members has supported my own career progression.”

Advice is integral in the collaborative network

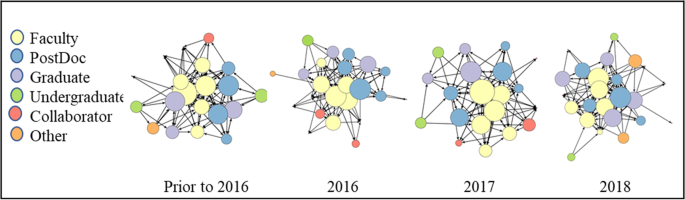

In the 2015–2017 advice network diagrams, the faculty were tightly clustered (Fig. 7 ). In 2018, the cluster separated as postdocs and graduate students joined the centre of the network. On average, team members reported 5.1 to 6.4 people they could go to for advice (Fig. 4 ).

This diagram was created by using participant answers to the social network question, “who do you go to for advice?” Each circle or node represents a person on the team. The nodes are sized by outdegree to show who reported receiving mentorship. Node size indicates how many mentors an individual reported, and arrows indicate nodes that served as mentors. Colours denote different roles on the team.

In a survey, faculty responded to the question, “How has the team supported you personally and professionally?” One faculty member wrote: “Just today I asked three members of the team for professional advice! And got a thoughtful and prompt response from all.” Another team member wrote: “Being a member of the…team has allowed me to develop skills in statistical analysis, scientific writing, and critical thinking. This team has opened my eyes to what is possible to achieve with science and has provided me with opportunities to network and expand my horizons both within the field of study and outside of it.” These quotes further suggest that the mentoring and advice from a large interdisciplinary team were important to train future scientists.

Interpersonal relationships as driver for scientific productivity

The mentoring and advice networks supported and built on the scientific productivity network and vice versa. The correlation between the collaboration, mentoring, and advice networks would not be possible if the networks were not intertwined. In the retrospective survey, a faculty member described how tacit interpersonal relationships were correlated with their scientific productivity:

Being a part of this grant has helped me both personally and professionally by teaching me new skills (disease ecology, team dynamics), developing friendships/mentors from the team, and strengthening my CV and dossier for promotion to early full professorship.

A Ph.D. student also described how the relationships on the large team propelled their research.

Membership on this team has provided me with a lot of mentorship that I would not otherwise receive were I not working on a large multi-disciplinary for my doctoral research. It has also allowed me to network more effectively.

Between 2015 and 2018, the mentor and advice networks were significantly correlated with the scientific productivity network, demonstrating that personal relationships are associated with scientific collaboration (Table 2 ).

To date, the literature examining successful interdisciplinary scientific team skills that result in successful outcomes is sparse (Fiore, 2008 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Wooten et al., 2014 ). The majority of published work in this area is evaluated by archival data analysis, not individual team behaviour and assessment (Hall et al., 2018 ). This study answers the call of numerous researchers to use mixed-methods and SNA to investigate scientific teams (Bennett, 2011 ; Borner et al., 2010 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Woolley et al., 2010 ; Wooten et al., 2015 ). Our case-based study also increases understanding of the development and processes of an exemplary team by providing valuable insights about how the interactions that enhance scientific productivity are synergistic with the interactions that train future scientists. There are four major implications of our findings: (1) interactional and contributory expertise are intertwined; (2) team size, tacit knowledge gained from previous project, and interdisciplinary knowledge were used to effectively and efficiently train scientists; (3) the team increased scientific productivity through interpersonal relationships; and (4) the team fulfilled the land grant mission of the University by integrating teaching/training, research/discovery, and extension/engagement into the team’s activities.

Interactive and contributory expertise are intertwined

Previous literature on scientific teams has found that great teams are not built on scientific expertise alone, but on the processes and interactions that build psychological safety, create a shared language, engage members emotionally, and promote effective interactions (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ; Hall et al., 2019 ; Senge, 1991 ; Woolley et al., 2010 ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). The team highlighted in this report created a shared language and vision through the mentoring and advice networks that helped fuel the team’s scientific productivity (Hall et al., 2012 ). To solve complex problems requires more than contributory expertise, it also requires interactional expertise (Bammer et al., 2020 ). These forms of expertise are often tacit and internalised through the process of becoming an expert in a field of study (Collins and Evans, 2007 ). Learning-by-doing is augmented from project-to-project, with expertise codified over time (Bammer et al., 2020 ). Further, cognitive, emotional, and interactions are key components of successful collaborations (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ; Bozeman et al., 2013 ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). Using social network analysis, our case-based analysis found that the mentoring and advice ties were intertwined with the scientific productivity network.

Training scientists to be experts

The Retrospective Survey asked what personal and professional skills respondents learned from being a member of a team. We hypothesised that many respondents would report tangible skills. Surprisingly, 82% of the open-ended responses were about tacit skills. Students frequently had co-advised graduate research positions, worked in multiple labs, and communicated regularly with practitioners. Moreover, the team translated research to different disciplines within the team, mentored others, and managed interpersonal conflicts. These interactions built expertise because training was not limited to research in a single lab or only in an academic setting. Simple, discrete, and codified knowledge is relatively easy to transfer; however, teams need stronger relationships to gain complex and tacit knowledge, (Attewell, 1992 ; Simonin, 1999 ). On this team, interactions and the ability to practice communication were especially influential for students, junior scientists, and new members. These individuals provided survey responses reporting they learned a wide variety of skills ranging from leadership, scientific and interpersonal communication, networking across disciplines, scientific writing, laboratory techniques, and data sharing standards. Further, respondents noted they had gained experience in developing, nurturing, and respecting interpersonal relationships and diversity of opinions. This was reinforced with participant observation data. In other interdisciplinary groups studied in conjunction with this exemplary team, students were not typically exposed to the inner workings of the team such as leadership meetings. On this team, students were exposed to all conversations, which became an important component of the mentoring and advice structure, serving to train future scientists in all aspects of team integration and leadership development. Belonging to this large interdisciplinary team was effectively training, building, and structuring the team.

Interpersonal relationships increase scientific productivity

Longevity of relationships is an important factor in creating social cohesion, reducing uncertainty, and increasing reliability and reciprocity (Baum et al., 2007 ; Gulati and Gargiulo, 1999 ; Phelps et al., 2012 ). Previous literature has, however, rarely documented the importance of time in building the structure of the network (Phelps et al., 2012 ) and few longitudinal studies of scientific teams exist. Further, it has long been hypothesised that greater interaction among people increases the quality and innovativeness of ideas generated, which may in turn increase productivity (Cimenler et al., 2016 ). Our case-based study found that the mentoring and advice ties existed in a symbiotic relationship with the scientific productivity network where the practices of the team were simultaneously training scientists. This aligns with social network literature that interactions can structure the social network and the network structure influences interactions (Henry, 2009 ; Phelps et al., 2012 ). Second, intentional mentoring programmes have demonstrated a positive relationship between interdisciplinary mentoring and increased research productivity outcomes such as grant funding and publications (Spence et al., 2018 ). Finally, this finding also aligns with literature on the generation of new knowledge (Phelps et al., 2012 ). Knowledge creation has traditionally been framed in terms of individual creativity, but recent studies have placed more emphasis on how the contribution of social dynamics are influential in explaining this process (Boix Mansilla et al., 2016 ; Csikszentmihalyi, 1998 ; Phelps et al., 2012 ; Sawyer, 2003 ; Zhang et al., 2009 ). Thus, while we might think that science drives the team, in this case-based study, the team’s interpersonal relationships were the driver of the team’s scientific productivity.

Fulfilling the land grant mission

As noted above, this exemplary team fulfilled all three goals of the land grant mission. First, the team was training scientists at all levels, from undergraduate students, to graduate students, postdocs, new faculty, and external collaborators, including community partners. In many instances, the training and mentoring was structured in a vertically integrated manner. For example, postdocs were training graduate and undergraduate students, typical of many teams. In addition to the “top-down” scenarios, however, the team also encouraged training that went from the bottom up as well. Effectively, this is a hallmark of successful teams in other sectors such as emergency responders and elite military teams – whomever has the knowledge to drive the issue at hand is the effective “leader” in that mission (Kotler and Wheal, 2008 ). Second, the team excelled in research and discovery, partnering with a diversity of external collaborators to do so. This created a network structure wherein the team clearly utilised the collaborators for mentoring and advice. Organisations with a core-periphery network structure like this team have been reported to be more creative because ties on the periphery, such as external collaborators, can span boundaries and access diverse information (Perry-Smith, 2006 ; Phelps et al., 2012 ). Finally, because the team’s collaborators included community partners and practitioners, they were also influencing policy and practice. This resulted in an overall greater impact for the team’s science and allowed them to tailor their research to best meet the needs of society (Barge and Shockley-Zalabak, 2008 ).

Future research

This study provides a unique contribution to team science literature because it longitudinally studied the development and processes of a successful interdisciplinary team (Wooten et al., 2014 ). Future research on the elements of effective interdisciplinary teaming is required in five key areas. First, identification of best practices that inhibit or support teams is necessary (Fiore, 2008 ; Hall et al., 2018 ; Wooten et al., 2014 ). Second, previous research has found that small teams are best at disrupting science with new ideas and opportunities (Wu et al., 2019 ); however, practices large teams use to create new knowledge have been poorly documented. Third, successful training concepts for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers need additional consideration (Knowlton et al., 2014 ; Ryan et al., 2012 ; Sarraj et al., 2017 ). Fourth, we hypothesise that graduate students act as bridges in teams to connect scientific disciplines and prevent clustering the network. Future research should investigate the role of graduate students in creating knowledge through interdisciplinary teams. Finally, additional research is needed to better recognise and reward scientists who undertake integration and implementation (Bammer et al., 2020 ).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available in the Mountain Scholar repository, https://doi.org/10.25675/10217/214187

Attewell P (1992) Technology diffusion and organizational learning: the case of business computing. Organ Sci 3(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.3.1.1

Article Google Scholar

Bammer G, O’Rourke M, O’Connell D, Neuhauser L, Midgley G, Klein JT, … Richardson GP (2020). Expertise in research integration and implementation for tackling complex problems: when is it needed, where can it be found and how can it be strengthened? Palgrave Commun, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0380-0

Barge JK, Shockley-Zalabak P (2008) Engaged scholarship and the creation of useful organizational knowledge. J Appl Commun Res 36(3):251–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880802172277

Baum JAC, McEvily B, Rowley T (2007) Better with age? Tie longevity and the performance implications of bridging and closure. SSRN (vol. 23). INFORMS. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1032282

Bennett ML (2011) Collaboration and team science: a field guide-team science toolkit. Retrieved February 19, 2019, from https://www.teamsciencetoolkit.cancer.gov/Public/TSResourceTool.aspx?tid=1&rid=267

Boix Mansilla V, Lamont M, Sato K (2016) Shared cognitive–emotional–interactional platforms: markers and conditions for successful interdisciplinary collaborations. Sci Technol Human Value 41(4):571–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915614103

Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Freeman LC (2014) UCINET. Encyclopedia of social network analysis and mining. Springer New York, New York, NY, 10.1007/978-1-4614-6170-8_316

Google Scholar

Borner K, Contractor N, Falk-Krzesinski HJ, Fiore SM, Hall KL, Keyton J, Uzzi B (2010). A multi-level systems perspective for the science. Sci Transl Med 2: 49

Bozeman B, Fay D, Slade CP (2013, February 28). Research collaboration in universities and academic entrepreneurship: the-state-of-the-art. J Technol Transf https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-012-9281-8

Brandes U, Wagner D (2011) Analysis and visualization of social networks. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 321–340. 10.1007/978-3-642-18638-7_15

Cimenler O, Reeves KA, Skvoretz J, Oztekin A (2016) A causal analytic model to evaluate the impact of researchers’ individual innovativeness on their collaborative outputs. J Model Manag 11(2):585–611

Collins H, Evans R (2007) Rethinking expertise. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Book Google Scholar

Collins JC (2001) Good to great. HarperBusiness, New York, NY

Csikszentmihalyi M (1998) Implications of a systems perspective for the study of creativity. In: Sternberg R (ed) Handbook of creativity (pp. 313–336. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511807916.018

Cummings JN, Kiesler S (2008) Who collaborates successfully? prior experience reduces collaboration barriers in distributed interdisciplinary research. Cscw: 2008 Acm conference on computer supported cooperative work, Conference Proceedings, pp. 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1145/1460563.1460633

De Montjoye YA, Stopczynski A, Shmueli E, Pentland A, Lehmann S (2014) The strength of the strongest ties in collaborative problem solving. Sci Rep 4. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05277

Dozier AM, Martina CA, O’Dell NL, Fogg TT, Lurie SJ, Rubinstein EP, Pearson TA (2014) Identifying emerging research collaborations and networks: method development. Eval Health Prof 37(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278713501693

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Duhigg Ch (2016) What google learned from its quest to build the perfect team-The New York Times. Retrieved December 2, 2017, from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html

Falk-Krzesinski HJ, Contractor N, Fiore SM, Hall KL, Kane C, Keyton J, Trochim W (2011) Mapping a research agenda for the science of team science. Res Eval 20(2):145–158. https://doi.org/10.3152/095820211X12941371876580

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fiore SM (2008) Interdisciplinarity as teamwork. Small Group Res 39(3):251–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496408317797

Giuffre K (2013) Communities and networks: using social network analysis to rethink urban and community studies, 1st edn. Polity Press, Cambridge MA, 10.1177/0042098015621842

Greenwood RE (1993) The case study approach. Bus Commun Q 56(4):46–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/108056999305600409

Gulati R, Gargiulo M (1999) Where do interorganizational networks come from? Am J Sociol 104(5):1439–1493. https://doi.org/10.1086/210179

Hall KL, Vogel AL, Croyle RT (2019) Strategies for team science success: handbook of evidence-based principles for cross-disciplinary science and practical lessons learned from health researchers. Springer Nature, Switzerland

Hall KL, Vogel AL, Huang GC, Serrano KJ, Rice EL, Tsakraklides SP, Fiore SM (2018) The science of team science: a review of the empirical evidence and research gaps on collaboration in science. Am Psychol 73(4):532–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000319

Hall KL, Vogel AL, Stipelman BA, Stokols D, Morgan G, Gehlert S (2012) A four-phase model of transdisciplinary team-based research: goals, team processes, and strategies. Transl Behav Med 2(4):415–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-012-0167-y

Hanneman RA, Riddle M (2005a) Introduction to social network methods: table of contents. Riverside, CA. Retrieved from http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/

Hanneman R, Riddle M (2005b) Introduction to social network methods. Retrieved from http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robert_Hanneman/publication/235737492_Introduction_to_social_network_methods/links/0deec52261e1577e6c000000.pdf

Henry AD (2009). Society for human ecology the challenge of learning for sustainability: a prolegomenon to. source: human ecology review (Vol. 16). Retrieved from https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy2.library.colostate.edu/stable/pdf/24707537.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Ae9ffb98fef69c055ab05ead486b9ca7e

Klein C, DiazGranados D, Salas E, Le H, Burke CS, Lyons R, Goodwin GF (2009) Does team building work? Small Group Res 40(2):181–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496408328821

Knowlton JL, Halvorsen KE, Handler RM, O’Rourke M (2014) Teaching interdisciplinary sustainability science teamwork skills to graduate students using in-person and web-based interactions. Sustainability (Switzerland) 6(12):9428–9440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6129428

Kotler S, Wheal J (2008) Stealing fire: how silicon valley, the navy seals, and maverick scientists are revolutionising the way we live and work. Visual Comput (vol. 24). Retrieved from https://qyybjydyd01.storage.googleapis.com/MDA2MjQyOTY1NQ==01.pdf

Lee S, Bozeman B (2005) The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Soc Stud Sci 35(5):673–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312705052359

Matthews NE, Cizauskas CA, Layton DS, Stamford L, Shapira P (2019) Collaborating constructively for sustainable biotechnology. Sci Rep 9(1):19033. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54331-7

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Patton MQ (2011) Developmental evaluation: applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. Guilford Press

Perry-Smith JE (2006) Social yet creative: the role of social relationships in facilitating individual creativity. Acad Manag J 49(1):85–101. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.20785503

Phelps C, Heidl R, Wadhwa A, Paris H (2012) Agenda knowledge, networks, and knowledge networks: a review and research. J Manag 38(4):1115–1166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311432640

Qualtrics Labs I (2005). Qualtrics Labs, Inc. Provo, Utah, USA

R Studio Team (2020) RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, http://www.rstudio.com/

Read EK, O’Rourke M, Hong GS, Hanson PC, Winslow LA, Crowley S, Weathers KC (2016) Building the team for team science. Ecosphere 7(3):e01291. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1291

Ryan MM, Yeung RS, Bass M, Kapil M, Slater S, Creedon K (2012) Developing research capacity among graduate students in an interdisciplinary environment. High Educ Res Dev 31(4):557–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2011.653956

Sarraj H, Hellmich M, Chao C, Aronson J, Cestone C, Wooten K, Allan, B (2017) Training future team scientists: reflections from translational course. In: Team science training for graduate students and postdocs. Clearwater, FL. Retrieved from www.scienceofteamscience.org

Sawyer RK (2003) Emergence in creativity and development. In: Sawyer RK, John-Steiner V, Moran S., Sternberg RJ, Nakamura J et al. (eds.) Creativity and development. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, pp. 12–60

Chapter Google Scholar

Senge PM (1991) The fifth discipline, the art and practice of the learning organization. Perform Instruct 30(5):37–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.4170300510

Simonin BL (1999) Ambiguity and the process of knowledge transfer in strategic alliances. Strateg Manag J 20(7):595–623. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199907)20:7<595::AID-SMJ47>3.0.CO;2-5

Spence JP, Buddenbaum JL, Bice PJ, Welch JL, Carroll AE (2018) Independent investigator incubator (I3): a comprehensive mentorship program to jumpstart productive research careers for junior faculty. BMC Med Educ 18(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1290-3

Stokols D, Misra S, Moser RP, Hall KL, Taylor BK (2008). The ecology of team science. Understanding contextual influences on transdisciplinary collaboration. Am J Prevent Med https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.003

Woolley AW, Chabris CF, Pentland A, Hashmi N, Malone TW (2010) Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science 330(6004):686–688. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1193147

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Wooten KC, Calhoun WJ, Bhavnani S, Rose RM, Ameredes B, Brasier AR (2015) Evolution of multidisciplinary translational teams (MTTs): insights for accelerating translational innovations. Clin Transl Sci 8(5):542–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12266

Wooten KC, Rose RM, Ostir GV, Calhoun WJ, Ameredes BT, Brasier AR (2014) Assessing and evaluating multidisciplinary translational teams: a mixed methods approach. Eval Health Profession 37(1):33–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278713504433

Wu L, Wang D, Evans JA (2019) Large teams develop and small teams disrupt science and technology. Nature 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0941-9

Wuchty S, Jones BF, Uzzi B (2007) The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science 316(5827):1036–1039. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1136099

Yin RK (2017) Case study research and applications: design and methods (6th edn.). Sage Publications

Zhang HH, Ding C, Schutte NS, Li R (2020) How team emotional intelligence connects to task performance: a network approach. Small Group Res 51(4):492–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496419889660

Article CAS Google Scholar

Zhang J, Scardamalia M, Reeve R, Messina R (2009) Designs for collective cognitive responsibility in knowledge-building communities. J Learn Sci 18(1):7–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508400802581676

Download references

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to Elizabeth Scodfidio for helping with data, images and more!. The research reported in this publication was supported by Colorado State University’s Office of the Vice President for Research Catalyst for Innovative Partnerships Programme. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of the Vice President for Research. Supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002535. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views. Funding and support were provided by grants from the National Science Foundation’s Ecology of Infectious Diseases Programme (NSF EF-0723676 and NSF EF-1413925).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Divergent Science LLC, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Hannah B. Love

Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Jennifer E. Cross, Bailey Fosdick, Kevin R. Crooks & Susan VandeWoude

University of New Mexico and Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Ellen R. Fisher

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HBL conceptualised the study, developed the methodology, curated the data, analysed the data, conducted the investigation, worked as the project manager, managed the software, validated the data, created visualisations, reviewed and edited the paper; BF conceptualised the study, developed the methodology, curated the data, analysed the data, managed the software, validated the data, supervised all aspects of the research, created visualisations, reviewed and edited the paper; JC conceptualised the study, developed the methodology, acquired funding, supervised data collection, and reviewed and edited the paper; KC and SV wrote the paper, secured funding, reviewed and edited the paper; and ERF conceptualised the study, developed the methodology, supervised all aspects of the research, acquired funding, created the visualisations, reviewed and edited the paper; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hannah B. Love .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

HBL, BF, JC, and ERF declare no competing interests. KC and SV are members of the exemplary team

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information, supplementary data, rights and permissions.