You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

The 10 Most Important Spanish Punctuation Marks to Know

Punctuation is more important than you might think— it can save lives .

But that does not mean all punctuation marks are used the same in both Spanish and English .

By the end of this post you will be able to write with confidence without ever having to worry whether your mistakes have put lives in danger.

Why Is Learning Spanish Punctuation Important?

Essential spanish punctuation marks, 1. punto (period), 2. coma (comma), 3. dos puntos (colon), 4. punto y coma (semicolon), 5. puntos suspensivos (ellipsis), 6. signo de interrogación (question mark), 7. signo de exclamación (exclamation point), 8. guion y raya (hyphen and em-dash), 9. paréntesis (parentheses), 10. comillas españolas (angle quotes) and comillas inglesas (quotation marks), where to practice using spanish punctuation, find and correct the mistakes in the following sentences:, and one more thing….

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

We all know that we finish sentences by using a period, we separate items in a list with commas and we close questions with question marks. You might think that is all you need to know, but if you really want to be fluent in Spanish, it is not!

Punctuation mastery is crucial for professional- or academic-grade writing skills . You will need it to write resumes or cover letters if you ever want to land a job in a Spanish-speaking environment .

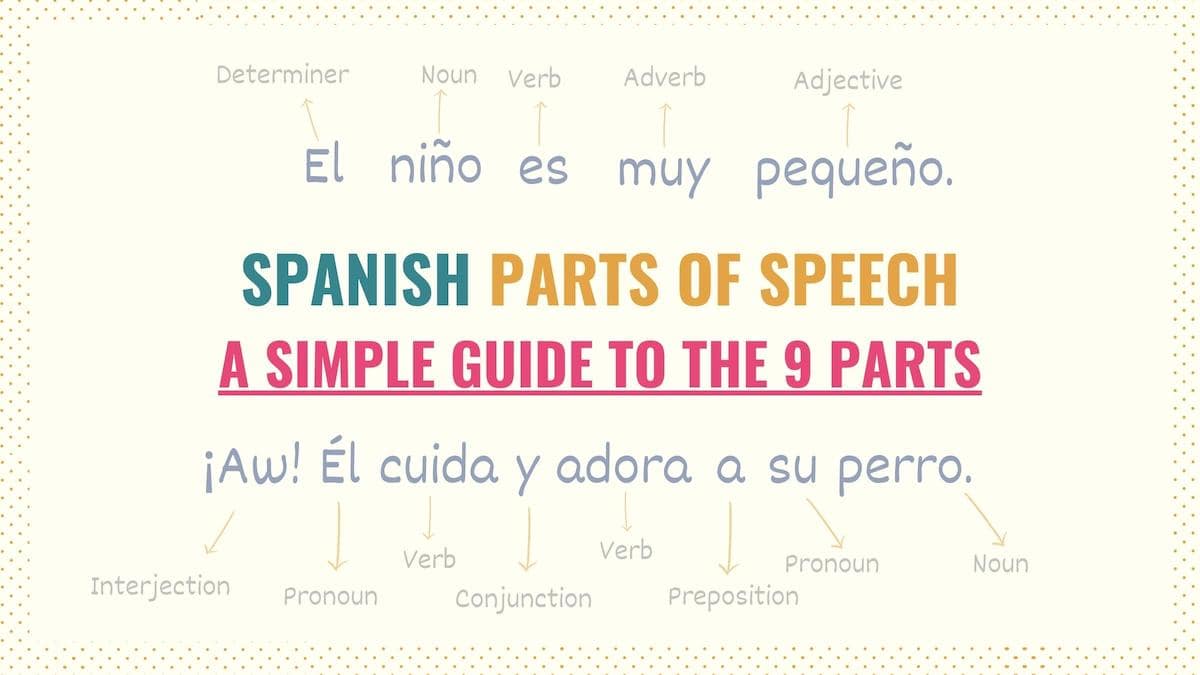

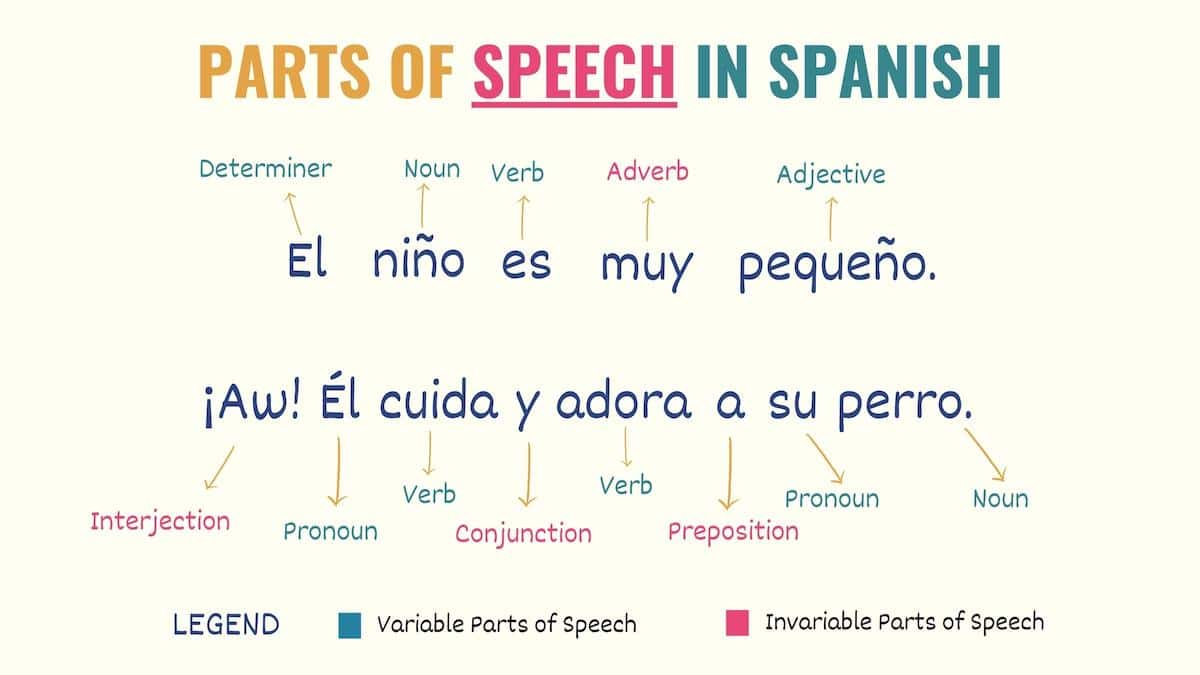

But understanding Spanish punctuation has a broader benefit, as well—it will make Spanish grammar easier by forcing you to think about sentence structure and parts of speech.

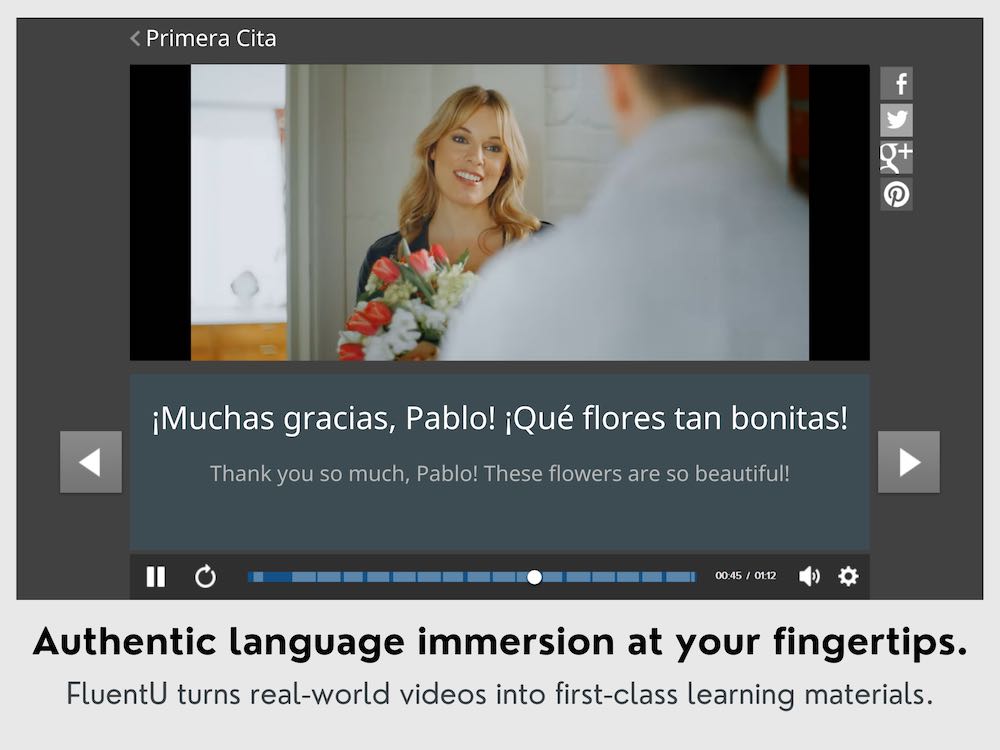

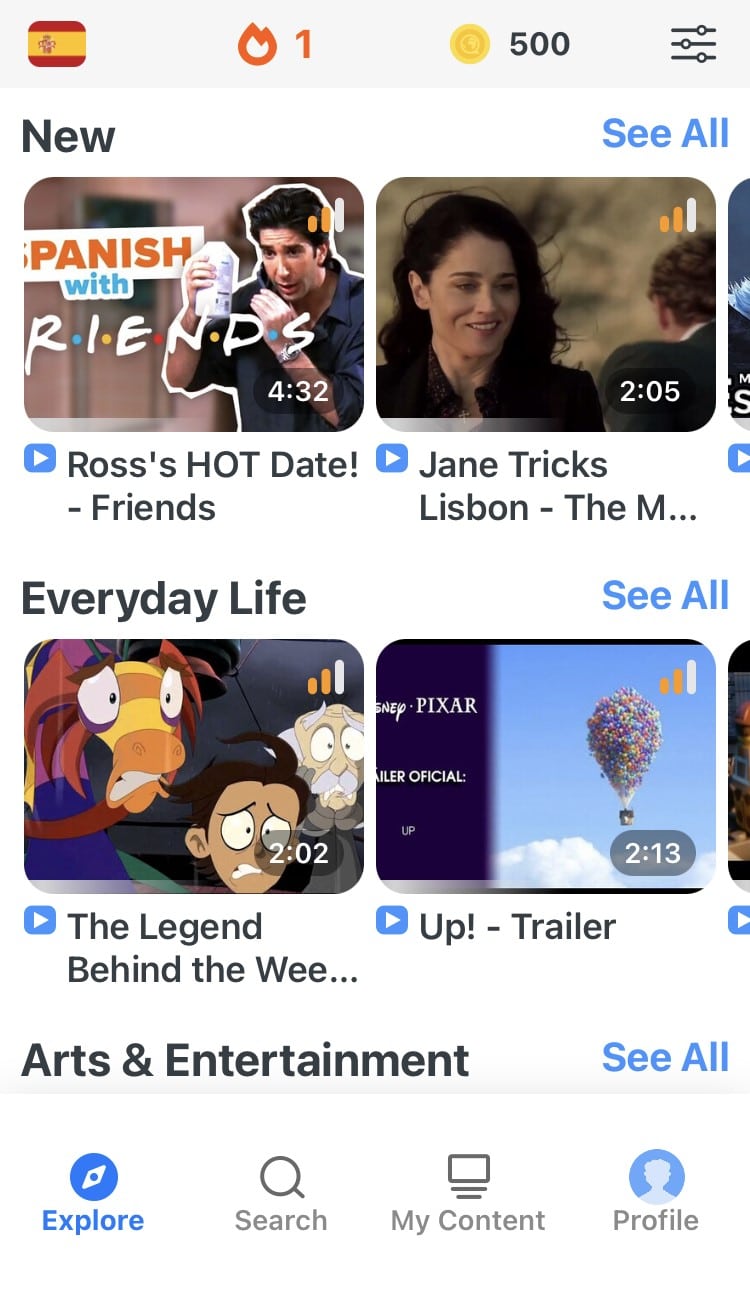

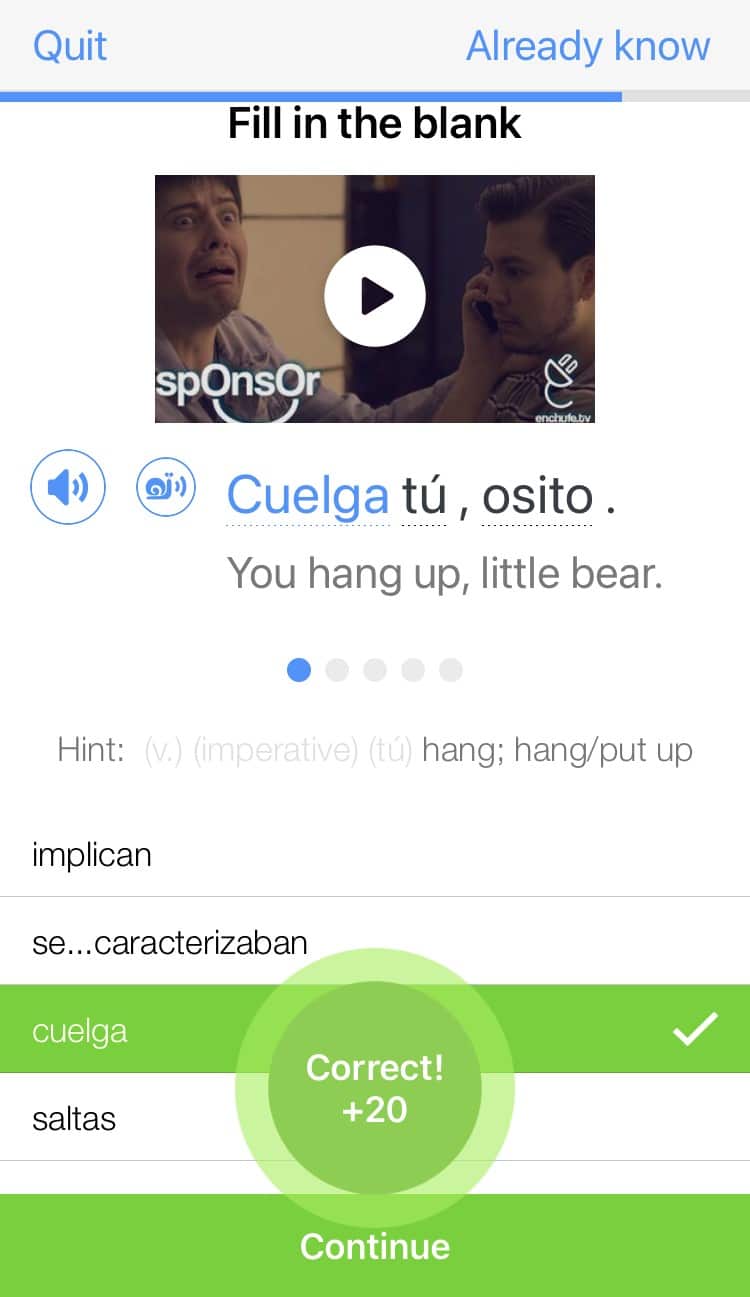

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Try FluentU for FREE!

The period is the punctuation mark we use in order to tell the reader he or she needs to make a long pause. Generally speaking, periods come at the end of the sentence (as long as it is not a question or an exclamation) and they tell us the main idea of the sentence has been conveyed and we can make a pause.

El niño juega en el parque. (The boy is playing in the park.)

Tengo sueño. (I am sleepy.)

Easy! You convey your message and close it with a period. Cool and simple. Everybody knows that, I am sure.

What maybe not everybody knows is that there are three important different kinds of periods in Spanish: the punto y seguido , the punto y aparte and the punto final .

If we translate their names literally, we get “period and continued,” “period and aside” and “final period,” respectively.

And what is the difference between them?

We use a punto y seguido when we keep on writing after that period without starting a new paragraph . All the periods inside a paragraph except for the last one are puntos y seguido .

For the sake of space, the following examples are not whole paragraphs but pairs of sentences together. The periods separating each pair of sentences is a punto y seguido :

Tengo sueño. Me voy a la cama. (I am sleepy. I am going to bed.)

He comprado un coche. El coche es rojo. (I have bought a car. The car is red.)

We use a punto y aparte when we want to start a new paragraph. Typically, with the punto y aparte we mark a change of topic or an idea not directly related to the previous one:

… cuando llegó.

Cerró la puerta y…

(…when she arrived.

She closed the door and…)

Finally, a punto final is any period that closes a single isolated sentence or closes the whole writing. I know it may seem a bit weird to have a specific name for something that only occurs once in a chapter, essay or composition, but since we have it, why not boast about it?

Take the closest book you have. Open it and have a look at the last sentence of the last paragraph of the last page. There will probably be a period. There you have your example of a punto final .

The uses of the comma in Spanish and English are very similar. We mainly use it to make shorter pauses in a sentence, separate items on a list or add explanatory phrases:

Mis colores favoritos son el rojo, el amarillo y el verde. (My favorite colors are red, yellow and green.)

Mi hermano, que es médico, vive en Barcelona. (My brother, who is a doctor, lives in Barcelona)

However, there are a couple of differences between the use of the comma in American English and Spanish . Have a look:

When writing quotation marks (more on those later in this post), add the comma after them in Spanish, but include the comma before them in American English:

“Tengo sueño”, dijo María. (“I am sleepy,” said María.)

“He comprado un coche rojo”, dije. (“I have bought a red car,” I said.)

When you have a long number, especially if it is a decimal one, use commas and periods in Spanish in the opposite way you would do it in English:

Spanish: 1.234.567,89

English: 1,234,567.89

Remember one last thing regarding commas, both in Spanish and English: you typically should not separate a subject from its predicate by a comma.

Incorrect: Ella, ha comprado un coche. (She, has bought a car.)

Correct: Ella ha comprado un coche. (She has bought a car.)

As it happened with the comma, the use of the colon in Spanish and English is pretty much the same.

Although it can be used for many different purposes, when it comes to writing, the colon is mainly used to indicate that what comes next is an explanation of what has just been said, an enumeration, a list or a quote.

For example:

Estaba cansado: había estado escribiendo toda la noche. (He was tired: he had been writing all night long.)

When read aloud, the pause for the colon is generally longer than the comma’s, but shorter than the period’s.

You typically need to write a lowercase letter after the colon. Even though we call the colon two points in Spanish, that does not mean it follows the same rules as the period!

There is one last thing you should bear in mind when using the colon in Spanish. Everybody writes letters or emails. There are literally thousands of ways of starting a letter, but let us say the easiest one is writing “Dear Mr. X,” and then continuing on another line.

If you have a look, you will notice you add a comma after “Mr. X” in English. Avoid doing this in Spanish! Instead, use a colon because… well, just because!

So remember to write it properly when you start writing an email to your boss!

I have always loved that the semicolon is called punto y coma in Spanish, because you actually have to write a period and a comma to produce a semicolon.

But besides that, I think the semicolon is not only the punctuation mark I have used the least in my life, but also the one that took me the longest amount of time to understand!

The semicolon is some weird hybrid between a comma and a period. It is like a comma and a period but it is neither the former nor the latter… it is here to complicate our lives… only if we let it win!

The truth is, the semicolon is very easy to use, and it is used in the same exact way in both English and Spanish .

So when should we use it?

There are two main uses of the semicolon, and while one is very precise and easy to understand, the other is abstract and absolutely open to interpretation. But we will start with the easier one:

- Use the semicolon when making a list in order to separate the different items, especially if the items are long sentences and include commas. Easy. Here the semicolon acts as a “bigger brother” who tries to help the comma so it knows when each item ends.

Me gusta hacer muchas cosas, sobre todo viajar por el mundo; descubrir nuevas culturas, si tengo tiempo, claro; y comer la comida local. (I like to do a lot of things, especially travel around the world; discover new cultures, if I have the time, of course; and eat the local food).

- Use the semicolon instead of the period in order to join independent clauses if they are closely related to each other. For example:

En verano voy a España; en invierno voy a las montañas. (In summer I go to Spain; in winter I go to the mountains.)

Tu hermano es médico; mi hermano es profesor. (Your brother is a doctor; my brother is a professor.)

If the sentences are short, do not overthink it. Just use a comma:

Te amo, te adoro. (I love you, I adore you).

The ellipsis is another punctuation mark that works practically the same way in Spanish as in English .

Lately, especially thanks to the use of texts, instant messaging and emails, a lot of people tend to overuse it by adding it to the end of almost every sentence. However, the uses of the ellipsis are very well defined and we should go back to using it properly.

Of the many uses of the ellipsis, the three main ones are:

- To mark an interruption or speech that trails off. This is the main use of the ellipsis.

Pensaba que me querías… (I thought you loved me…)

Algún día lo entenderás… (Someday you will get it…)

- To show fear or suspense. This time you use the ellipsis to make a pause, but then you continue with your speech or writing:

Y entonces… lo maté. (And then… I killed him.)

Oí una voz… pero no podía ver nada… estaba temblando… (I heard a voice… but I could not see anything… I was shaking…)

- To make a non-comprehensive list of items. When you add the ellipsis at the end of the list, the reader understands there are more examples aside from the ones you are naming:

Tenemos todos los colores: azul, amarillo, rojo, rosa, verde… (We have all the colors: blue, yellow, red, pink, green…)

Algunos ejemplos de esto pueden ser perros, gatos, pájaros, conejos, peces… (Some examples of this can be dogs, cats, birds, rabbits, fish…)

The question mark is one of the easiest-to-use punctuation marks because it is universally used to close questions.

The only thing you need to remember and bear in mind is that in Spanish you need to use an inverted question mark (also known as an opening question mark) at the beginning of every question !

Do Spanish people write it? Yes, we do!

Is it necessary? Yes, it is!

Will I get lower grades if I leave it out? Yes, of course!

Forget about lazy Spanish people who now have a tendency to ignore the opening question mark when chatting or writing emails. That is as big an error as writing “velieve” instead of “believe” or using a comma at the end of a sentence. Just learn to use it, because it is a must!

Here you have some examples:

¿Qué hora es? (What time is it?)

¿Cómo te llamas? (What is your name?)

¿Estás seguro? (Are you sure?)

We have exactly the same situation when it comes to the exclamation point. We use it for the same purpose both in Spanish and English, but we need to add exclamation points at the beginning of every exclamation.

Once again, do not try to find excuses and ignore the lazy people who try not to use it. You would not start a sentence with a lowercase letter, right? Exactly…

¡Qué bonito! (How beautiful!)

¡No lo hagas! (Do not do it!)

¡Me estoy volviendo loco! (I am going crazy!)

I have a confession to make: I used to get lost every time I had to use the hyphen and the em-dash because, for me, they have always been one and the same thing, except one is longer than the other…

Do not judge me, nobody is perfect!

However, I can share a little trick with you that has made my life easier and has helped me remember (most of the time) when I should use each of them.

To put it simply, remember the following: the raya separates and the guion unites.

Once you internalize that little mnemonic, you will easily remember that we use the raya to separate the different voices in a dialog in Spanish (i.e., each new line of dialog is separated from the rest and starts with an em-dash):

—Hola, María. (—Hello, María.)

—Hola, ¿qué tal estás? (—Hello, how are you?)

— Muy bien, gracias. (—Very well, thanks.)

The em-dash can also be used in Spanish to separate side notes or explanatory information somewhat like parentheses, although this usage is more common in English than Spanish .

We use the hyphen to unite . In other words, hyphens can show two words are related, show the rest of a word continues on the next line or show that two numbers form an interval.

físico-químico (physicochemical)

páginas 45-50 (pages 45-50)

There are other minor uses of the em-dash and hyphen, but if you master this little trick, you are good to go for sure!

Parentheses are another punctuation mark you use practically in the same way in Spanish as in English.

Parentheses can be used for many different purposes, but there is always one thing in common: you will always need an opening parenthesis and a closing one.

The main uses of the parentheses in Spanish are:

- To clarify aside from the main point. This use of the parentheses is quite subjective, because sometimes they can be replaced by commas and the sentence remains the same. Where should you draw the line?

There is not a universal answer to this question, but bear in mind the closer you are to the main point, the better it is to use commas:

María (mi vecina) es estudiante. María (my neighbor) is a student.

El coche de mi hermano (un BMW) es blanco. My brother’s car (a BMW) is white.

- To add meanings of abbreviations. It is not compulsory, but it is always good practice if you think the reader may have problems with the text:

OMS (Organización Mundial de la Salud). WHO (World Health Organization).

- To add dates and/or places. This is quite self-explanatory, so just have a look at the examples:

Vivo en Madrid (España) . I live in Madrid (Spain).

La Segunda Guerra Mundial (1939-1945) fue un conflicto militar global. WWII (1939-1945) was a global military conflict.

Even though there are different kinds of quotes, almost every language has a preference and will make use of one type more often than the others .

Spanish uses three types of quotes: guillemets or angle quotes (« »), quotation marks (” “) and simple quotation marks (‘ ‘), but our favorite are the guillemets.

In recent years, more and more Spanish-speaking people are using the so-called English quotation marks (” “), but Spanish newspapers and publishing houses in general tend to stick to tradition and keep on using angle quotes.

But what are angle quotes for?

We can use angle quotes for many different reasons, but the common denominator is always one: we are marking another level in the sentence. This “new level” can be a quotation, an ironic remark, a different sense of a common word, an expression, a thought or even a foreign word, but overall it is on a different level than the rest of the sentence, and we need to indicate that.

So, imagine you are writing a text in Spanish and want to quote what an author said in a book. How would you let the reader know the following words are on a different level and have not been written or said by you? Exactly! You use angle quotes:

…como dijo José M., «Eso es una pena». (…as José M. said, “That is a pity.”)

As I have just mentioned, you can also use angle quotes to mark irony, add expressions or use words with an uncommon meaning.

Compré este vestido en una «boutique». (I bought this dress in a “boutique.”)

Eres un chico muy «inteligente». (You are a very “intelligent” guy.)

Earlier I mentioned Spanish makes use of three different kinds of quotes. But why? Well, it would be a real mess to have quotes inside of quotes inside of quotes if you used the same angle marks all the time!

Chaos, I tell you!

The following example is written twice. In the first instance, I have used angle quotes only. The second one contains three different types of quotes. Which one is more clear and prettier for you?

Entonces dijo: «Me parece que decir «compar en una «boutique»» es algo muy tonto». (Then he said: “I think saying “buying in a “boutique”” is something very silly.”)

Entonces dijo: «Me parece que decir “comprar en una ’boutique'” es algo muy tonto». (Then he said: “I think saying ‘buying in a ’boutique” is something very silly.”)

Now that you have studied the theory, how about doing some exercises so you can check if you have understood everything?

In the first part of this section, you will have some sentences with punctuation errors. Your task will be to find the errors and correct them.

You will find the correct answers just below.

In the second part, I will give you some external links where you can practice more Spanish punctuation if you feel you still need some more.

Are you ready?

Pepe, corre por el parque.

Me gusta cocinar

Compré uno verde; uno amarillo y uno azul.

Nació en Sevilla, España.

No sabía lo que significaba “bailar el agua”.

Una ONG – Organización No Gubernamental – es imprescindible en la zona.

No puedo lo siento.

He comprado zumo. Manzanas, peras y leche.

Pepe corre por el parque.

Me gusta cocinar.

Compré uno verde, uno amarillo y uno azul.

Nació en Sevilla (España).

No sabía lo que significaba « bailar el agua » .

Una ONG (Organización No Gubernamental) es imprescindible en la zona.

No puedo, lo siento.

He comprado zumo, manzanas, peras y leche.

All these punctuation marks may be confusing at the beginning, but I promise after you do a couple of exercises, you will learn to see the differences.

I hope after reading this post you feel more comfortable when presented with writing assignments or any time you need to write a letter or email to your friend or your new boss! You will certainly see your Spanish writing improve.

I have thoroughly enjoyed showing you a little part of the marvelous world of punctuation, and I really hope you have enjoyed learning about it as well.

If you've made it this far that means you probably enjoy learning Spanish with engaging material and will then love FluentU .

Other sites use scripted content. FluentU uses a natural approach that helps you ease into the Spanish language and culture over time. You’ll learn Spanish as it’s actually spoken by real people.

FluentU has a wide variety of videos, as you can see here:

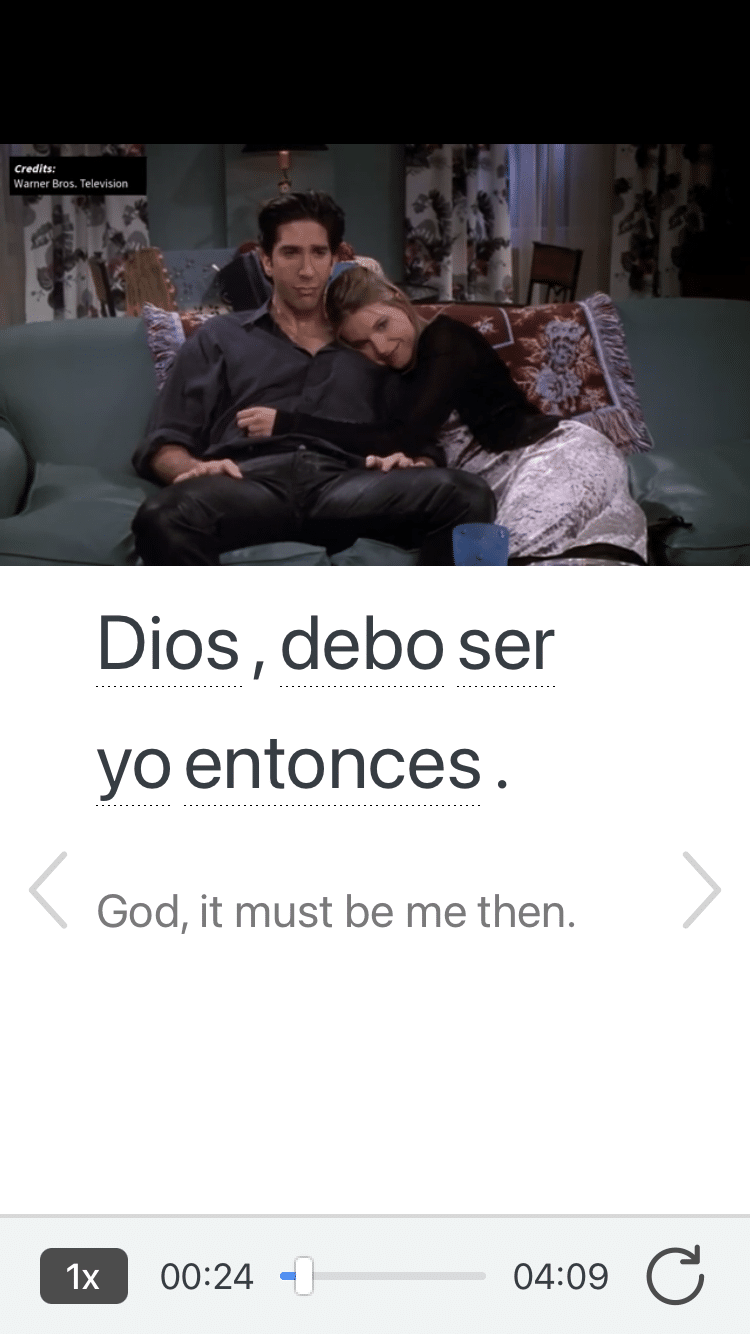

FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive transcripts. You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don’t know, you can add it to a vocab list.

Review a complete interactive transcript under the Dialogue tab, and find words and phrases listed under Vocab .

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU’s robust learning engine. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you’re learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. Every learner has a truly personalized experience, even if they’re learning with the same video.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

855-997-4652 Login Try a Free Class

How to Write Dialogues in Spanish for Maximum Clarity

Have you ever seen a Spanish dialogue and thought it looks a bit different from an English one?

If you haven’t seen one yet, let me show you!

On my bookshelf, I have two editions of One Hundred Years of Solitude (Cien años de soledad) by Gabriel García Márquez: one is in English and the other is a 2007 commemorative edition from the Royal Spanish Academy (Real Academia Española).

Here are two lines of a dialogue between José Aureliano Buendía and the gypsy:

Desconcertado, sabiendo que los niños esperaban una explicación inmediata, José Arcadio Buendía se atrevió a murmurar: —Es el diamante más grande del mundo. —No —corrigió el gitano—. Es hielo.

Disconcerted, knowing that the children were waiting for an immediate explanation, José Arcadio Buendía ventured a murmur: “It’s the largest diamond in the world.” “No,” the gypsy countered. “It’s ice.”

Notice the glaring differences in punctuation?

Keep reading to learn why Spanish dialogues look different and how to write them in Spanish!

Angular Quotation Marks, Double Quotation Marks, or Long Dashes?

As you can see in the dialogue above, Spanish uses long dashes called rayas (—) as dialogue punctuation. Conversely, English uses double quotation marks.

Some Spanish writers use double quotation marks or angular quotation marks (« and »), but the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE) says it should be rayas .

In this article, I follow the official RAE recommendations by using rayas . However, I also tell you what to watch for when using double or angular quotation marks.

- Spanish Alt Codes

- The Spanish Keyboard: How to Type Anything in Spanish

How to Punctuate Dialogues in Spanish

To write dialogue in Spanish, you need to do a bit more than change the quotation marks into long dashes.

Here are a few more factors to take into account!

1. Punctuation Goes Outside Quotation Marks

Whereas in American English, commas and periods go inside the quotation marks, in Spanish, they always go outside.

No matter whether you use quotation marks (double or angular) instead of long dashes, you must apply this rule.

“No me gusta su gato”, dijo Pedro. «No me gusta su gato», dijo Pedro.

“I don’t like his cat,” Peter said.

Fun fact! It’s also the rule in British English for punctuation to go outside single quotation marks.

2. Long Dashes Precede New Speakers

In Spanish dialogue, the long dash precedes the intervention of each of the speakers, without having to mention their names.

—¿Cuándo te escribirás a un curso de español? —No tengo ni idea. —Apúrate, tienen una promoción en la escuela de la esquina. —Gracias, voy a verlo esta tarde.

“When will you enroll in a Spanish course?” “I have no idea.” “Hurry up, they have a promotion at the school around the corner.” “Thanks, I’m going to check it this afternoon.”

Normally, in Spanish novels, what each character says appears on a new line, just like in English.

No space goes between the long dash and the character’s words and the closing of what the character says ends with punctuation, not with another long dash.

3. Long Dashes Introduce the Narrator’s Comments

Narrative texts also use long dashes to introduce or frame the narrator’s comments.

—Tengo hambre —dijo Pedro. —Tengo hambre —dijo Pedro—. Voy a prepararme algo.

“I’m hungry,” Peter said. “I’m hungry,” said Pedro. “I’m going to prepare something.”

You use the long dash to introduce the character’s words at the beginning of the line. Later, you use it only to introduce or frame what the narrator says, such as:

—dijo Pedro—

It’s not necessary to add the long dash again to introduce additional character dialogue.

Now, we need to consider two situations when alluding to the narrator’s comments. They may use “speaking verbs” to credit the speech to the character who said it or it may refer to something completely different (as you’ll see).

Punctuation With Speaking Verbs

When the narrator indicates that a character is speaking, they use so-called “speaking verbs,” such as: dijo (said) , respondió (answered) , and preguntó (asked) .

Some formatting standards to keep in mind include:

- Leaving a space between what the character says and the long dash that introduces the narrator’s comment.

- Not leaving a space between the long dash and the narrator’s comment

—Tengo hambre —dijo Pedro. “I’m hungry,” said Pedro.

- The narrator’s comment begins in lowercase:

—dijo Pedro.

- The punctuation mark corresponding to the character’s phrase is closed after the narrator’s clarification, whether it’s a comma, period or semicolon.

—Tengo hambre —dijo Pedro. —Tengo hambre —dijo Pedro—. Voy a prepararme algo. —Tengo hambre —dijo Pedro—, y tengo sed. —Tengo hambre —dijo Pedro—; y tengo sed.

- If the punctuation mark that you want to put after the narrator’s entry is a colon, write it after the closing long dash:

—Ayer salí a correr —y añadió: Ahí conocí a alguien. “I went out for a run yesterday,” and added, “I met someone there.”

- If the punctuation mark that corresponds to the character’s phrase is a question mark, exclamation mark, or ellipsis (…), they should always close before the narrator’s intervention

—¿Tienes hambre? —preguntó María. —¡No comas esto! —gritó Juan—. ¡Es veneno!

Notice how the narrator’s intervention starts in lowercase even though there is a punctuation mark before that would require an uppercase letter.

Make sure you don’t make the mistake of capitalizing the speaking verb:

—¿Tienes hambre? —Preguntó María. (incorrect)

- If the dialogue continues, it closes with a long dash after the narrator’s intervention.

—Tengo hambre —dijo Pedro—. Voy a prepararme algo.

Common Speaking Verbs in Spanish Dialogue

Here is a list of the most common speaking verbs in the third-person past tense:

You can use these verbs to vary your narrator’s comments in a Spanish dialogue, but remember that the narrator’s comments should be transparent. Using overly sophisticated speaking verbs may trip up the reader.

Punctuation Without Speaking Verbs

When you introduce the narrator’s comment that includes “non-speaking verbs,” there are a few more rules to remember:

- The character’s words must be closed with a period and the narrator’s phrase must begin with a capital letter.

—No te preocupes. —Cerró la puerta y salió corriendo. “Don’t worry.” He closed the door and ran out.

- If the character’s speech continues after the narrator’s comment, write the period that marks the end of the narrator’s comment after the closing long dash.

—No te preocupes. —Cerró la puerta y salió corriendo—. Volveré pronto. “Don’t worry.” He closed the door and ran out. “I’ll come back soon.”

Punctuation for Thoughts

What do you do when your character thinks rather than says the words aloud? Use angular quotation marks instead of long dashes.

«Tengo hambre», pensó Pedro. “I’m hungry,” Pedro thought.

—Puedes hacerlo —le dije y pensé «pero te costará mucho trabajo». “You can do it,” I told him and thought, “but it will cost you lots of work.”

Practice Your Spanish before Writing a Spanish Dialogue

Now you know how to write dialogue in Spanish between two friends or characters. Congratulate yourself on taking yet another step towards fluency in Spanish!

While traveling to a Spanish-speaking country is enough motivation for most Spanish learners, if writing is your thing, other possibilities await you.

Just imagine, one day you could become a bilingual writer!

Yes, there are some bilingual writers who write books in their second or even third language. Sometimes they are able to publish books in all the languages they know. Isn’t it amazing?

Our 1-on-1 classes at Homeschool Spanish Academy will help you improve your language skills faster than if you were studying alone. To see if it works for you, sign up for a free class with one of our amazing, Spanish-speaking teachers from Guatemala. Show them your Spanish dialogues and scripts to practice them with a professional!

Ready to learn more Spanish grammar? Check these out!

- 25 Common Subjunctive Phrases in Spanish Conversation

- What Is an Infinitive in Spanish?

- A Complete Guide to Imperfect Conjugation for Beginners

- How to Talk About the Temperature in Spanish: Fahrenheit, Celcius, and Descriptions

- A Complete Guide to Preterite Conjugation for Beginners

- Spanish Words with Multiple Meanings in Latin America

- How Many Words Are in the Spanish Language? Really?

- Avoiding Common Errors in Spanish Grammar

- Recent Posts

- 10 Homeschooling Styles You Need to Explore in 2023 - March 14, 2024

- Home Sweet Classroom: Creating Engaging Spanish Lessons at Home - October 13, 2023

- Expressing Appreciation in Spanish on World Teachers’ Day - October 5, 2023

Related Posts

Spanish for dummies [greetings, questions, small talk, and more], 3 types of spanish pronouns to perfect your fluency, how to say ‘you’ in formal and informal spanish, the ultimate guide to filler words in spanish for more natural conversations, leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Spanish Private Tutoring

- Spanish Group Classes

- Spanish Video Tutorials

- Spanish for Kids

- How it Works

- Spanish Guide

Spanish Punctuation Marks: The Complete Guide | Learn, Mastering

- 25 Feb, 2024

- 5 Mins Read

There are 18 punctuation marks in Spanish. Examples of the most commonly used Spanish punctuation marks are punto, coma, dos puntos, barra, signo de interregación, signo de exclamación.

Spanish Punctuation forms the basis of written language. They express the meaning of the sentence and provide effective communication. Punctuation in Spanish is the same as in other languages. Knowing Spanish punctuation marks is necessary to write Spanish accurately and fluently.

Table of Contents

Punto – Period(.)

Coma – comma(,), dos puntos – colon(:), punto y coma – semicolon(;), puntos suspensivos -ellipsis(…), signo de interrogación – question mark(), signs de exclamación – exclamation mark(), comillas – quotation marks(«»), barra – slash(/), how to make spanish punctuation marks on the keyboard, how to use punctuation marks in spanish.

The types of punctuation in Spanish are listed below.

The period, known as “punto” in Spanish, is the most fundamental punctuation mark. It serves the same purpose as in English, indicating the end of a sentence or an abbreviation. For example:

- El niño juega en el parque. (The boy is playing in the park.)

- Tengo sueño. (I am sleepy.)

The period is straightforward to use, and it signifies the completion of a thought or idea. It is worth noting that there are three types of periods in Spanish: “punto y seguido,” “punto y aparte,” and “punto final.” These variations indicate different contexts within a paragraph, indicating whether to continue within the same section or start a new paragraph.

The comma, known as “coma” in Spanish, is another essential punctuation mark that assists in creating clarity and conveying meaning. It is used to indicate pauses, separate items in a list, and set off clauses or phrases within a sentence.

In Spanish, the usage of the comma is similar to English, with a few notable differences. Unlike in English, Spanish does not use the Oxford comma (a comma before the conjunction “and” in a list). Additionally, when using quotation marks, the comma is placed after the closing quotation mark in Spanish, while it is placed before in English. For example:

- Mis colores favoritos son el rojo, el amarillo y el verde. (My favorite colors are red, yellow, and green.)

- “Te amo”, le dijo con una sonrisa en la cara. (“I love you,” he said with a smile on his face.)

The colon, known as “dos puntos” in Spanish, is used to introduce an explanation, list, enumeration, or quotation. It signals that what follows the colon provides further information or elaborates on the preceding statement. For example:

- Estaba cansado: había estado escribiendo toda la noche. (He was tired: he had been writing all night long.)

- Los signos de puntuación son los siguientes: el punto, la coma, el punto y coma, etc. (The punctuation marks are as follows: period, comma, semicolon, etc.)

The semicolon, known as “punto y coma” in Spanish, is a versatile punctuation mark that bridges the gap between a comma and a period. It indicates a longer pause than a comma but shorter than a period. The semicolon is primarily used to separate closely related independent clauses and to clarify complex lists or ideas. For example:

- En verano voy a España; en invierno voy a las montañas. (In summer I go to Spain; in winter I go to the mountains.)

- En la reunión se discutirán los avances en el programa de pagos automáticos; las nuevas ideas de producto; los ganadores del premio de puntualidad y las propuestas para la cena de Navidad. (At the meeting, we’ll discuss the advances in the automatic payments program; the new product ideas; the winners of the attendance and punctuality prize, and the proposals for the Christmas party.)

The ellipsis, known as “puntos suspensivos” in Spanish, serves the same purpose as in English. It indicates an omission, creates suspense or expectation, or suggests a trailing off of thought. The ellipsis can also be used to express hesitation or uncertainty. For example:

- Si tan solo… bueno, ya no importa. (If only… well, it doesn’t matter anymore.)

In Spanish, the question mark is called “signo de interrogación.” It is used in the same way as in English, with one key difference: Spanish requires an upside-down question mark at the beginning of a question in addition to the regular question mark at the end. For example:

- ¿Cómo te llamas? (What’s your name?)

- ¿De dónde eres? (Where are you from?)

Similar to the question mark, the exclamation point in Spanish is called “signo de exclamación.” It is used to convey strong emotions, exclamations, or direct commands. Like the question mark, Spanish requires an upside-down exclamation point at the beginning of an exclamation. For example:

- ¡Qué maravilloso! (How marvelous!)

- ¡Cuidado! (Be careful!)

Quotation marks, known as “comillas” in Spanish, are used to indicate direct speech, quotes, or titles of short works. Spanish utilizes different types of quotation marks for aesthetic purposes, such as angled quotation marks (“comillas españolas”) and straight quotation marks (“comillas inglesas”). For example:

- “Tengo sueño”, dijo María. (“I am sleepy,” said María.)

- Quiero leer «Romeo y Julieta». (I want to read “Romeo and Juliet.”)

The slash, known as “barra” in Spanish, is a special character used to indicate alternatives, dates, or fractions. It can be used to replace the conjunction “or” in lists or to express a range of possibilities. For example:

- El libro está escrito en inglés/español. (The book is written in English/Spanish.)

- La reunión será el 10/03/2022. (The meeting will be on 10/03/2022.)

Mastering Spanish punctuation marks is essential for effective communication and accurate expression in writing. By understanding the usage and nuances of each punctuation mark, you can elevate your Spanish language skills and convey your thoughts and ideas with clarity and precision.

Each of these marks serves a unique purpose, and understanding their usage will enhance your writing and enable you to communicate more effectively in Spanish.

To use Spanish punctuation marks on your keyboard, you must hold down the “ALT” or “CTRL” keys and click on the relevant punctuation mark.

Patricia Doval

Patricia Doval is a Spanish linguist at onlinelearnspanish.com. She holds a Ph.D. in Hispanic Linguistics from the University of Western Ontario, specializing in language contact. She's a bilingual Spanish-English. She has a master's in Spanish grammar and is responsible for our grammar-related articles.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Writing Dialogues in Spanish - Punctuation

Spanish grammar.

Dialogues in Spanish start with a long dash – (raya) not a short dash - (guión).

In this article, we will simply call the long dash, a dash.

–Estoy listo. (= "I am ready")

Notice how there is no space between the dash and the first letter.

Dialogues do not end in a dash (–) , only the normal punctuation sign (normally a full stop, question mark, or exclamation mark).

Punctuation with Attributives

A dash is also used to introduce an attributive. An attributive in a dialogue credits the speech to the person who said it. It refers to a verb or action associated with speaking and who said it.

–dijo él. (= he said) –respondió ella. (= she responded) –preguntó. (= he/she asked)

Again, the dash is joined to first letter of the first word. Also notice how that first word, normally a “speaking” verb starts with a lowercase letter.

More examples of “speaking” verbs in Spanish are:

aceptó (accepted), aconsejó (advised), admitió (admitted), afirmó (affirmed/asserted), amenazó (threatened), bromeó (joked), comentó (commented), concluyó (concluded), dijo (said), gritó (shouted), mintió (lied), preguntó (asked), prometió (promised), repitió (repeated), respondió (responded), rogó (begged), sugirió (suggested), susurró (whispered).

Now let’s look at both parts joined together: The speech and the attributive.

–Estoy lista –dijo ella.

There is no period (full stop) at the end of the first part since it is continued by an attributive. We can only put a question mark, an explanation mark or ellipsis (three dots) in the speech part when it is followed by an attributive. See how there is a space between what is being said and the dash that is joined to the attributive. Remember, the speaker’s attributive begins with a lowercase letter.

–¿Estás bien? –preguntó Diego. –Sí, estoy bien –le contestó Angélica con una sonrisa.

The speech of each person is written a separate line. The first speech has the question marks directly after the words. The second speech does NOT have the period (full stop) directly after what is said. Here it appears at the end of the attributive.

What happens if there is more dialogue after the attributive?

–Estoy lista –dijo ella–. Me voy a la fiesta.

First we add a dash to the end of the attributive. This is followed by the final punctuation mark of the first part of speech. In the example above, Estoy lista should end in a period (full stop) but instead, it goes after the dash at the end of the attributive. Since it is a new sentence, the second part begins with a capital letter.

If it helps, you can think of the dashes in –dijo ella– as parentheses.

But look at the following:

–Estoy lista –dijo ella–, y nadie me va a parar.

Here the dialogue is a longer sentence that is interrupted by the attributive. Since the punctuation mark is a comma, the second part continues with a lowercase letter.

However, if the first part ends in a question mark, exclamation mark or an ellipsis (three dots), then this goes at the end of the first part.

–¡Estás loco! –gritó Daniel–. Tienes que parar inmediatamente.

If the narrator’s comment has nothing to do with a speaking or thinking verb (including related actions like shouting, whispering etc.) then the narrator’s sentence begins with a capital letter.

–Me voy. –Cerró la puerta y salió.

Using the Colon in dialogue

Until now, we have only seen the attributive (speaking verb) after what is being said. However, sometimes you have what the narrator says before the speech. In this case we use a colon after the "speaking verb".

Mi madre dijo: –Vamos en diez minutos.

Le preguntó al doctor: –¿Estaré bien?

The dialogue goes on the next line.

Punctuation when thinking

When a person is directly THINKING instead of speaking, then the punctuation « » (comillas) are used instead of the dash. These are known as comillas angulares , comillas latinas , and also comillas españolas .

«¡Qué aburrido!», pensé. Pero no me atreví a decirlo. «Hay algo raro aquí», pensó el detective. –Puedes llegar a ser un buen jugador –le expliqué y pensé, «aunque nunca tan bueno como yo».

Notice the position of the period (full stop) and comma go after the final closing comilla.

Punctuation when quoting

Quotes, or repeating what someone else has said, are enclosed in comillas.

Fue Descartes quien dijo: «Pienso, luego existo» . Sus últimas palabras fueron: «No pasará nada» .

Next Activities

If you found this guide about Spanish Punctuation in Dialogues interesting or useful, let others know about it.

Spanish Reading Passages

Improve your Spanish with our reading passages. There are different topics for beginner to advanced level students. There is also a special section for Spanish teachers.

SEE OUR SPANISH READING TEXTS

Spanish Verb Lists

A list of common verbs in Spanish with their conjugation in different tenses and example sentences. There are also interactive games to practice each verb.

SEE OUR LIST OF SPANISH VERBS

Connect with us

Deep Spanish

Free spanish lessons and readings

Your cart is currently empty!

Lesson 2 – Spanish Speech Markers (Marcadores del Discurso)

What are “los marcadores del discurso”.

The Spanish speech markers (“Los marcadores del discurso”) are linguistic elements that help to structure and organize a text or speech. They serve as connectors or links between sentences, providing cohesion and coherence to the discourse. In Spanish, these markers can be words or phrases that indicate the relationship between the ideas expressed, making it easier for the reader or listener to follow the flow of the text.

Let’s start with the connectors

Connectors (los conectores)

These are the markers that link one part of the speech with a previous one. Their function is to maintain logical relationships or dependencies between the ideas conveyed by different statements.

They can be

- María y Juan fueron al cine.

- No me gusta la comida picante. Además , soy alérgico a los camarones.

- Me gusta leer libros de ciencia ficción. También disfruto de las películas de ese género.

- Estudia mucho para sus exámenes. Asimismo , participa en actividades extracurriculares.

- No me gusta el café ni el té.

Consecutivos

- No tenía dinero, entonces no pudo comprar el libro.

- Estaba lloviendo, por lo tanto , decidimos quedarnos en casa.

- No había luz en la casa, así que encendimos velas.

- No estudió para el examen, en consecuencia , reprobó.

- El tráfico estaba terrible, de modo que llegamos tarde al evento.

Contraargumentativos

- Me gusta el cine, pero no quiero ir hoy.

- Estaba cansado, sin embargo , siguió trabajando.

- Aunque tenía miedo, decidió enfrentar la situación.

- Sabía que era difícil, no obstante , se esforzó al máximo.

- A él le gusta el fútbol, en cambio , a ella le gusta el baloncesto.

Justificativos

- No fui a la fiesta porque estaba enfermo.

- No puedo ir al cine contigo ya que tengo mucho trabajo.

- No salimos a caminar puesto que estaba lloviendo.

- El vuelo se retrasó debido a mal tiempo.

- La carretera estaba cerrada a causa de un accidente.

Condicionales

- Si estudias, aprobarás el examen.

- Lleva un paraguas en caso de que llueva.

- No podrás entrar a menos que tengas una invitación.

- Puedes usar mi coche siempre que lo devuelvas antes de las 10 pm.

- Te ayudaré a condición de que me lo pidas.

Information structurers

- These speech markers serve to signal the beginning, continuity, or closure of an idea within a text or speech. They help to guide the reader or listener through the development of the argument or narrative.

They can be “de”

- Para empezar , quiero decir que estoy de acuerdo con la propuesta.

- En primer lugar , debemos analizar la situación actual.

- Antes que nada , agradezco la oportunidad de hablar ante ustedes.

- En segundo lugar , es importante considerar las posibles soluciones.

- La empresa ha tenido éxito en el pasado. Además , cuenta con un equipo altamente capacitado.

- El proyecto es costoso. Por otro lado , tiene el potencial de generar ingresos significativos.

- En resumen , la propuesta tiene ventajas y desventajas, pero vale la pena considerarla.

- Por último , quiero agradecer a todos por su atención y participación.

- En conclusión , creo que debemos seguir adelante con el proyecto.

Comentadores (Commentary)

- El proyecto es ambicioso, es decir , requerirá de mucho esfuerzo y dedicación.

- La situación es complicada; en otras palabras , no hay una solución fácil.

- A mi parecer , la mejor opción es seguir adelante con la propuesta.

- Desde mi punto de vista , debemos ser cautelosos al tomar una decisión.

- En efecto , los datos muestran que la estrategia ha sido exitosa.

Digresores (Digressions)

- A propósito , ¿has hablado con Juan sobre el tema?

- Por cierto , me encontré con María ayer y me comentó sobre los cambios en la empresa.

- A todo esto , ¿qué pasó con el informe que ibas a presentar?

- Volviendo al tema , creo que debemos centrarnos en las prioridades principales.

- En cuanto a la propuesta, creo que debemos analizarla detenidamente antes de tomar una decisión.

Reformulating speech markers

are used to rephrase, clarify or summarize information within a text or speech. They help to ensure that the intended message is conveyed accurately and effectively. We will explore four main categories of reformulating discourse markers: explicativos, rectificativos, de distanciamiento, and recapitulativos.

Explicativos (Explanatory)

- La situación es complicada; o sea , no hay una solución fácil.

- No estoy de acuerdo con la propuesta. Me explico , creo que hay otras opciones más viables.

- No me gusta el diseño. Aclaro , no es que esté mal hecho, sino que prefiero otro estilo.

- El proceso es lento y tedioso; en otras palabras , llevará tiempo completarlo.

Rectificativos (Rectifying)

- El proyecto es costoso, mejor dicho , es una inversión importante.

- La reunión es mañana, no hoy. Rectifico , me equivoqué en la fecha.

- En realidad , la situación no es tan grave como parece.

- De hecho , los datos demuestran que la estrategia ha sido exitosa.

- El problema no es la falta de recursos, más bien es la mala administración de los mismos.

De Distanciamiento (Distancing)

- La propuesta tiene ventajas. Sin embargo , también presenta desventajas importantes.

- Aunque entiendo tu punto de vista, no estoy de acuerdo con él.

- El equipo ha trabajado duro. No obstante , los resultados no son los esperados.

- La idea es interesante, pero creo que necesita más desarrollo.

- A pesar de los contratiempos, seguimos adelante con el proyecto.

Recapitulativos (Recapitulating)

- En síntesis , el proyecto presenta oportunidades de crecimiento y desarrollo.

- Para concluir , creo que debemos seguir adelante con el proyecto.

- En pocas palabras , la situación es complicada pero no imposible de resolver.

- En suma , los beneficios superan los riesgos y debemos continuar con la propuesta.

Argumentative operators

“Los operadores argumentativos,” are essential tools for constructing logical and persuasive arguments in both written and spoken Spanish. They help to establish relationships between ideas and guide the reader or listener through the argument. We will examine two main categories of argumentative operators: gradativos and no gradativos.

Gradativos (Gradual)

- En primer lugar , debemos analizar los datos disponibles.

- Además , es importante tener en cuenta las opiniones de los expertos.

- También debemos considerar las posibles consecuencias a largo plazo.

- Asimismo , es crucial evaluar los costos y beneficios.

- Por último , debemos tomar una decisión basada en la información recopilada.

No Gradativos (Non-gradual)

No gradativos are argumentative operators that do not indicate a gradual progression or hierarchy within an argument. Instead, they help to establish relationships between ideas, such as cause and effect, contrast, or concession. Some common no gradativos include:

Causales (Causal)

- No podemos continuar con el proyecto porque no tenemos suficientes recursos.

- Puesto que no hay consenso, debemos buscar otra solución.

- No es posible avanzar ya que no hemos recibido la aprobación necesaria.

Concesivos (Concessive)

- Aunque hay argumentos en contra, creo que debemos seguir adelante.

- La propuesta tiene sus desventajas, sin embargo , sus beneficios son mayores.

- No obstante las dificultades, el equipo logró cumplir con los objetivos.

Contrastivos (Contrastive)

- La idea es interesante, pero necesita más desarrollo.

- La opción A es más costosa, en cambio , la opción B es más económica.

- La empresa X ha tenido éxito, mientras que la empresa Y ha enfrentado dificultades.

Informal Discourse Markers

- ¿Vamos al cine? – Pues sí, me parece buena idea. (Shall we go to the movies? – Well, yes, that sounds like a good idea.)

- ¿Qué te parece la propuesta? – Pues … no sé, tengo que pensarlo. (What do you think about the proposal? – Well… I don’t know, I have to think about it.)

- No puedo ir a la fiesta, pues tengo que estudiar para un examen. (I can’t go to the party, as I have to study for an exam.)

- Ya entiendo lo que quieres decir. (Now I understand what you’re saying.)

- Ya veo que tienes razón. (I see that you’re right.)

- Ya terminé el trabajo. (I’ve already finished the work.)

- Hombre , ¡no me esperaba verte aquí! (Man, I didn’t expect to see you here!)

- Hombre , no estoy de acuerdo con esa idea. (Man, I don’t agree with that idea.)

- Hombre , tienes que ver esta película. (Man, you have to see this movie.)

- Mujer , ¡cuánto tiempo sin verte! (Girl, it’s been so long since I’ve seen you!)

- Mujer , creo que te estás equivocando. (Girl, I think you’re mistaken.)

- Mujer , este restaurante es increíble. (Girl, this restaurant is amazing.)

- Hija , ¿estás bien? Te ves cansada. (Sweetheart, are you okay? You look tired.)

- Hijo , ¡no sabía que venías a visitarme! (Son, I didn’t know you were coming to visit me!)

- Hija , no te preocupes tanto por lo que piensen los demás. (Sweetheart, don’t worry so much about what others think.)

Understanding Basic Spanish Punctuation

sgrunden/Pixabay

- Writing Skills

- History & Culture

- Pronunciation

- B.A., Seattle Pacific University

Spanish punctuation is so much like English's that some textbooks and reference books don't even discuss it. But there are a few significant differences.

Learn all the Spanish punctuation marks and their names. The marks whose uses are significantly different than those of English are explained below.

Punctuation Used in Spanish

- . : punto, punto final (period)

- , : coma (comma)

- : : dos puntos (colon)

- ; : punto y coma ( semicolon )

- — : raya (dash)

- - : guión (hyphen)

- « » : comillas (quotation marks)

- " : comillas (quotation marks)

- ' : comillas simples (single quotation marks)

- ¿ ? : principio y fin de interrogación (question marks)

- ¡ ! : principio y fin de exclamación o admiración (exclamation points)

- ( ) : paréntesis (parenthesis)

- [ ] : corchetes, parénteses cuadrados (brackets)

- { } : corchetes (braces, curly brackets)

- * : asterisco ( asterisk )

- ... : puntos suspensivos (ellipsis)

Question Marks

In Spanish, question marks are used at the beginning and the end of a question. If a sentence contains more than a question, the question marks frame the question when the question part comes at the end of the sentence.

- Si no te gusta la comida, ¿por qué la comes?

- If you don't like the food, why are you eating it?

Only the last four words form the question, and thus the inverted question mark, comes near the middle of the sentence.

- ¿Por qué la comes si no te gusta la comida?

- Why are you eating the food if you don't like it?

Since the question part of the sentence comes at the beginning, the entire sentence is surrounded by question marks.

- Katarina, ¿qué haces hoy?

- Katarina, what are you doing today?

Exclamation Point

Exclamation points are used in the same way as question marks are except to indicate exclamations instead of questions. Exclamation marks are also sometimes used for direct commands. If a sentence contains a question and an exclamation, it is okay to use one of the marks at the beginning of the sentence and the other at the end.

- Vi la película la noche pasada. ¡Qué susto!

- I saw the movie last night. What a fright!

- ¡Qué lástima, estás bien?

- What a pity, are you all right?

It is acceptable in Spanish to use up to three consecutive exclamation points to show emphasis.

- ¡¡¡No lo creo!!!

I don't believe it!

In regular text, the period is used essentially the same as in English, coming at the end of sentences and most abbreviations. However, in Spanish numerals, a comma is often used instead of a period and vice versa. In U.S. and Mexican Spanish, however, the same pattern as English is often followed.

- Ganó $16.416,87 el año pasado.

- She earned $16,416.87 last year.

This punctuation would be used in Spain and most of Latin America.

- Ganó $16,416.87 el año pasado.

- She earned $16,416.87 last year.

This punctuation would be used primarily in Mexico, the U.S., and Puerto Rico.

The comma usually is used the same as in English, being used to indicate a break in thought or to set off clauses or words. One difference is that in lists, there is no comma between the next-to-last item and the y , whereas in English some writers use a comma before the "and." This use in English is sometimes called the serial comma or the Oxford comma.

- Compré una camisa, dos zapatos y tres libros.

- I bought a shirt, two shoes, and three books.

- Vine, vi y vencí.

- I came, I saw, I conquered .

The dash is used most frequently in Spanish to indicate a change in speakers during a dialogue, thus replacing quotation marks. In English, it is customary to separate each speaker's remarks into a separate paragraph, but that typically isn't done in Spanish.

- — ¿Cómo estás? — Muy bien ¿y tú? — Muy bien también.

- "How are you?"

- "I'm fine. And you?"

- "I'm fine too."

Dashes can also be used to set off material from the rest of the text, much as they are in English.

- Si quieres una taza de café — es muy cara — puedes comprarla aquí.

- If you want a cup of coffee — it's very expensive — you can buy it here.

Angled Quotation Marks

The angled quotation marks and the English-style quotation marks are equivalent. The choice is primarily a matter of regional custom or the capabilities of the typesetting system. The angled quotation marks are more common in Spain than in Latin America, perhaps because they are used in some other Romance languages (such as French).

The main difference between the English and Spanish uses of quotation marks is that sentence punctuation in Spanish goes outside the quote marks, while in American English the punctuation is on the inside.

- Quiero leer "Romeo y Julieta".

I want to read "Romeo and Juliet."

- Quiero leer «Romeo y Julieta».

- 3 Key Differences Between English and Spanish Punctuation

- Using the Comma in Spanish

- How to Use Angular Quotation Marks in Spanish

- How Does Spanish Use Upside-Down Question and Exclamation Marks?

- Exclamations in Spanish

- How to Use a Semicolon in Spanish

- How To Make Spanish Accents and Symbols in Ubuntu Linux

- How to Type Spanish Accents and Punctuation on a Mac

- Asking Questions in Spanish

- How to Type Spanish Accents, Characters, and Punctuation in Windows

- When To Place the Verb Before the Subject in Spanish

- Using 'No' and Related Words in Spanish

- 10 Facts About Spanish Prepositions

- Reflexive Verbs and Pronouns in Spanish

- Writing Dates in Spanish

- Using the Spanish Conjunction ‘Y’

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

StoryLearning

Learn A Language Through Stories

The Complete Guide To Spanish Punctuation

Understanding Spanish punctuation is a key part of learning Spanish reading and writing. While most Spanish punctuation marks will be familiar to you, some of them are used slightly differently or have different meanings.

Knowing how to use Spanish punctuation marks correctly will make your written Spanish more accurate and improve your chances of success in a Spanish-language job or academic environment.

It will also help you improve your reading comprehension and interpret Spanish texts more accurately – from newspapers to novels.

In this post, you'll discover some of the most common Spanish punctuation marks and how to use them. You'll also look at their names in Spanish, so that you can identify them when you hear people talk about them in conversation.

By the way, if you want to learn Spanish fast and have fun, my top recommendation for language learners is my Uncovered courses, which teach you through StoryLearning®. Click here to find out about my beginner course, Spanish Uncovered and try out the method for free.

22 Punctuation Marks And Symbols In Spanish

To start, here's a handy list of Spanish punctuation marks. In the next section, you'll discover how to use them.

How To Use Punctuation Marks In Spanish

Punto (Period/Full Stop)

The period or full stop is one of the most common punctuation marks in any language. Just like in English, it’s used to mark the end of a sentence in written Spanish. However, Spanish has three different types of periods depending on where it’s used in the sentence:

- When the paragraph continues you use punto y seguido

- Punto y aparte is used for ending a paragraph

- You use punto final for ending an entire document

These periods all look the same, so you don’t really need to be on the lookout for them; it’s only really important if you’re discussing the text academically.

The punto can be used in other contexts too. As in English, it’s used in urls and email addresses: instead of “dot com,” .com is read as punto com .

The period is also used for abbreviations, such as:

- Sr. ( Señor)

- c.c. ( centímetros cúbicos )

- EE. UU. ( Estados Unidos)

You can also use a period when referring to the time. This is more common than using a colon, as we do English. For example, 1 o’clock is 1.00 instead of 1:00.

Finally, the period is used to write numerals . Unlike in English, though, the period and comma are reversed. Periods are used to separate thousands, while a comma is used to separate decimals. For example, a large sum might look like this:

Keep in mind that if you encounter numerals in the U.S. or Mexico , they’ll typically follow U.S. conventions, so they would be written like this:

We won’t spend any time here on the colon ( dos puntos ), semicolon ( punto y coma) , or ellipsis ( punto suspensivos) because they’re used just as they are in English.

Next, let's look at the coma (comma).

Coma (Comma)

The coma, or comma, is another punctuation mark that’s used a lot like it is in written English. We’ve already seen one use for it (as a decimal marker), but it’s also used in written text to separate different parts of a sentence.

For example:

One difference that you may notice is that Spanish doesn’t use the Oxford comma. Or a comma after the second-to-last item in a list. In English, the use of the Oxford comma varies from country to country. But in Spanish, it’s avoided entirely.

This means that if you’re listing three or more items, you don’t include a comma before the word “ y ” or “and,” even if you would ordinarily use it in English.

Next you'll discover one of the punctuation marks that differs most from English.

Signos De Interrogación Y Exclamación (Question Marks And Exclamation Points)

The use of question marks and exclamation points is one of the most visible differences between English and Spanish punctuation marks.

Those upside-down questions marks are hard to miss when reading written Spanish. But you can struggle to find them on a keyboard when trying to type in Spanish!

These punctuation marks serve the same purpose in Spanish – to ask a question or to show excitement – but you must use them before and after the phrase.

Omitting the inverted question mark at the beginning may happen in some contexts, such as a text message or social media post, but it looks unprofessional in formal writing.

It’s important to note that in some cases, only part of the sentence needs to be included within the question marks or exclamation points. For example, if the name of the person who’s being addressed comes at the beginning of the sentence, it isn’t included:

But everything that comes after the first question mark or exclamation point is included:

You’ll notice that the first word of the question or exclamation isn’t capitalised, unless it’s at the beginning of the sentence or happens to be a proper noun or name.

For an explanation (in Spanish) of how to use Spanish question and exclamation marks, hit play on the video below from the StoryLearning Spanish YouTube channel.

Multiple Spanish Punctuation Marks

You can also use question marks and exclamation points together, which isn’t common in formal English, as well as multiple exclamation points to increase the emphasis:

As you can see, either the question mark or exclamation point can be used first, or they can be combined in either order.

Comillas (Quotation Marks)

Comillas, or quotation marks, come in several different forms in Spanish. Firstly, there’s the angled quotation mark (« »), or comilla española, which you'll find in European Spanish and other Romance languages like French.

Secondly, there’s the English quotation mark (“ “), or comillas inglesas , and also the single quotation mark, comilla simple , which in English also serves as an apostrophe. But these quotation marks are more commonly used in Latin American Spanish.

You can use quotation marks just as you would in English: to identify a quotation or dialogue, or to write the title of a book or movie:

While comillas are mostly used the same way in both languages, you might notice a few differences in how other punctuation marks are applied.

For example, in Spanish, you’ll need to use a punto after the quotation mark, even if it already includes another mark, like a question mark or exclamation point, that would be sufficient in English.

Also, English allows for some marks, like the comma, to fall within the quotation marks even if it isn’t part of the title of a book or movie; Spanish does not.

Because of the above rules you’ll occasionally end up with more punctuation marks in a row than would be natural in English.

Other Spanish Punctuation Marks And Symbols

So far, you've seen most of the major Spanish punctuation marks that you need to know in order to read and write in Spanish . But there are a few other symbols you may encounter, such as accent marks and numerical symbols.

Accent marks in Spanish are called tildes , although in English, we use the term tilde to refer only to a single diacritical mark, the (~) that goes over the letter n .

In Spanish, this isn’t actually treated as an accent mark, because the n and ñ are distinct letters of the Spanish alphabet! Instead, the (~) is referred to as virgulilla .

You can learn more about how and when to use Spanish accent marks in the video below.

When it comes to numerical symbols, (%) is referred to as por ciento , while (+) and (-) are más and menos .

It’s a good idea to be familiar with the names of these symbols, because they may come up when speaking aloud in Spanish. For example, a phone number with an area code (+57) would be pronounced as más cinco siete .

Likewise, some common Internet symbols have different names in Spanish. The at sign (@) is called arroba , while the backslash is barra invertida (although may be referred to as “slash” even in spoken Spanish). Guion bajo refers to an underscore.

If you listen to Spanish podcasts , you may hear the host invite you to email them at an address like “ info guion bajo 2021 arroba podcast punto com”, which means:

[email protected]

How To Type Spanish Punctuation Marks On Your Keyboard

Learning Spanish punctuation marks is fairly easy. But typing in Spanish on your keyboard is a different story. Depending on your operating system, you can use keyboard shortcuts to access Spanish punctuation marks, such as the ¡ and ¿.

On a Mac, you can use the Option key for some of them. Opt + 1 gives you an inverted exclamation point, while Opt + Shift + ? gets you an inverted question mark.

However, other devices have different keyboard shortcuts, so we won’t go into them all here.

Spanish Punctuation: Wrapping It Up

Just remember that punctuation marks are an integral part of Spanish, and leaving them out isn’t an option.

Take the time to learn them and use them properly, and you’ll be able to express yourself more accurately in Spanish and read it aloud more fluently!

Language Courses

- Language Blog

- Testimonials

- Meet Our Team

- Media & Press

Download this article as a FREE PDF ?

What is your current level in Swedish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Swedish tips…

Where shall I send the tips and your PDF?

We will protect your data in accordance with our data policy.

What is your current level in Danish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Danish tips…

NOT INTERESTED?

What can we do better? If I could make something to help you right now, w hat would it be?

Which language are you learning?

What is your current level in [language] ?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips, PLUS your free StoryLearning Kit…

Where shall I send them?

Download this article as a FREE PDF?

Great! Where shall I send my best online teaching tips and your PDF?

Download this article as a FREE PDF ?

What is your current level in Arabic?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Arabic tips…

FREE StoryLearning Kit!

Join my email newsletter and get FREE access to your StoryLearning Kit — discover how to learn languages through the power of story!

Download a FREE Story in Japanese!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Japanese and start learning Japanese quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

What is your current level in Japanese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Japanese StoryLearning® Pack …

Where shall I send your download link?

Download Your FREE Natural Japanese Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Japanese Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Japanese grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Japanese Grammar Pack …

What is your current level in Portuguese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Portuguese Grammar Pack …

What is your current level in German?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural German Grammar Pack …

Train as an Online Language Teacher and Earn from Home

The next cohort of my Certificate of Online Language Teaching will open soon. Join the waiting list, and we’ll notify you as soon as enrolment is open!

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Portuguese tips…

What is your current level in Turkish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Turkish tips…

What is your current level in French?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the French Vocab Power Pack …

What is your current level in Italian?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Italian Vocab Power Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the German Vocab Power Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Japanese Vocab Power Pack …

Download Your FREE Japanese Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Japanese Vocab Power Pack and learn essential Japanese words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE German Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my German Vocab Power Pack and learn essential German words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE Italian Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Italian Vocab Power Pack and learn essential Italian words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE French Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my French Vocab Power Pack and learn essential French words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Portuguese StoryLearning® Pack …

What is your current level in Russian?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Russian Grammar Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Russian StoryLearning® Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Italian StoryLearning® Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Italian Grammar Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the French StoryLearning® Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural French Grammar Pack …

What is your current level in Spanish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Spanish Vocab Power Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Spanish Grammar Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Spanish StoryLearning® Pack …

Where shall I send them?

What is your current level in Korean?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Korean tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Russian tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Japanese tips…

What is your current level in Chinese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Chinese tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Spanish tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Italian tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] French tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] German tips…

Download Your FREE Natural Portuguese Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Portuguese Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Portuguese grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural Russian Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Russian Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Russian grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural German Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural German Grammar Pack and learn to internalise German grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural French Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural French Grammar Pack and learn to internalise French grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural Italian Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Italian Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Italian grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download a FREE Story in Portuguese!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Brazilian Portuguese and start learning Portuguese quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in Russian!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Russian and start learning Russian quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in German!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in German and start learning German quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the German StoryLearning® Pack …

Download a FREE Story in Italian!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Italian and start learning Italian quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in French!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in French and start learning French quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in Spanish!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Spanish and start learning Spanish quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

FREE Download:

The rules of language learning.

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Rules of Language Learning and discover 25 “rules” to learn a new language quickly and naturally through stories.

What can we do better ? If I could make something to help you right now, w hat would it be?

What is your current level in [language]?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips…

Download Your FREE Spanish Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Spanish Vocab Power Pack and learn essential Spanish words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE Natural Spanish Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Spanish Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Spanish grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Free Step-By-Step Guide:

How to generate a full-time income from home with your English… even with ZERO previous teaching experience.

What is your current level in Thai?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Thai tips…

What is your current level in Cantonese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Cantonese tips…

Steal My Method?

I’ve written some simple emails explaining the techniques I’ve used to learn 8 languages…

I want to be skipped!

I’m the lead capture, man!

Join 84,574 other language learners getting StoryLearning tips by email…

“After I started to use your ideas, I learn better, for longer, with more passion. Thanks for the life-change!” – Dallas Nesbit

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips…

Join 122,238 other language learners getting StoryLearning tips by email…

Find the perfect language course for you.

Looking for world-class training material to help you make a breakthrough in your language learning?

Click ‘start now’ and complete this short survey to find the perfect course for you!

Do you like the idea of learning through story?

Do you want…?

SPANISH

TEACHER

- Aug 24, 2020

Punctuation Marks in Spanish

English and Spanish punctuation marks are used more or less the same way. There are a few variations, perhaps one of the most significant differences is that Spanish has opening question and exclamation marks while English does not. Opening marks didn't always exist in Spanish. In most languages a single question mark is used at the end of the question phrase. This was the habitual use also in Spanish, until the 18th century, when the Real Academia Española declared it mandatory to start questions with the inverted question mark (¿), and end with the common question mark (?). The institution ordered the same for exclamation marks (¡) and (!). The adoption was slow, and you can find books from the 19th century for example, that don’t use such opening marks.

Eventually, however, it did become widely accepted. This is in part due to the nature of Spanish syntax and at times the difficulty in deducing when an interrogative phrase actually begins, as compared to other languages. Many linguists believe the question mark originated from the Latin word qvaestio , meaning question. This word was reportedly abbreviated in the Middle Ages by scholars as just qo . Over time, a capital “Q” was written over the “o”, and formed one letter. Then, it morphed into the modern question mark we know today.

It is worth mentioning that the influence of technology and the English language are changing the use of opening marks in informal contexts. It is not common to see them in online chats, or in text messages between friends. Only the closing marks are commonly used in such settings.

Do you know the names of the punctuation marks in Spanish? Several of these marks are part of expressions in the everyday vocabulary of natives, so it is useful for learners of Spanish to be familiar with them. Here we go:

Punctuation Marks: Signos de Puntuación:

full stop or period . punto

comma , coma

semicolon ; punto y coma

colon : dos puntos

quotation marks “ ” comillas