The Effects of Sexism on American Women: The Role of Norms vs. Discrimination

Based on bfi working paper no. 2018-56, “the effects of sexism on american women: the role of norms vs. discrimination,” by kerwin kofi charles, professor, uchicago’s harris school of public policy; jonathan guryan, professor, northwestern university; and jessica pan, associate professor, national university singapore.

- Sexism experienced during formative years stays with girls into adulthood

- These background norms can influence choices that women make and affect their life outcomes

- In addition, women face different levels of sexism and discrimination in the states where they live as adults

- Sexism varies across states and can have a significant impact on a woman’s wages and labor market participation, and can also influence her marriage and fertility rates

What type of life experiences will these women have in terms of the work they do and the wages they earn? Will they get married and, if so, how young? If they have children, when will they start to raise a family? How many children will they have? According to the authors of the new BFI working paper, “The Effects of Sexism on American Women: The Role of Norms vs. Discrimination,” the answers to those questions depend crucially on where women are born and where they choose to live their adult lives.

Kerwin Kofi Charles, professor at the Harris School of Public Policy, and his colleagues employ a novel approach that examines how prevailing sexist beliefs shape life outcomes for women. Essentially, they find that sexism affects women through two channels: one is their own preferences that are shaped by where they grow up, and the other is the sexism they experience in the place they choose to live as adults.

On average, not all states are average The average American woman’s socioeconomic outcomes have improved dramatically over the past 50 years. Her wages and probability of employment, relative to the average man’s, have risen steadily over that time. She is also marrying later and bearing children later, as well as having fewer total children. However, these are national averages and these phenomena do not hold in all states across America. Indeed, the gap between men and women that existed in a particular state 50 years ago is largely the same size today. In other words, if a state exhibited less gender discrimination 50 years ago, it retains that narrower gap today; a state that exhibited more discrimination in 1970 has a similarly wide gap today. Much research over the years has focused on broad national trends when measuring sexism and its effect on women’s lives. A primary contribution of this paper is that it documents cross-state differences in women’s outcomes and incorporates non-market factors, like cultural norms. The focus of the authors’ analysis are the four outcomes described above: wages, employment, marriage, and fertility. Of the many forms sexism might take, the authors focus on negative or stereotypical beliefs about whether women should enter the workplace or remain at home. Specifically, sexism prevails in a market when residents believe that:

• women’s capacities are inferior to men;

• families are hurt when women work;

• and men and women should adhere to strict roles in society.

These cultural norms are not only forces that occur to women from external sources, but they are forces that also exist within women, and are strongly affected by where a woman is raised. For example, a girl may grow up within a culture that prizes stay-at-home mothers over working moms, as well as early marriages and large families. These are what the authors describe as background norms, and they are able to estimate the influence of these background norms throughout adulthood by comparing women who were born in one place and moved to different places, and those who were born in different places and moved to the same place. Once a woman reaches adulthood and chooses a place to live, she is then influenced by discrimination in the labor market and by what the authors term residential sexism, or those current norms that they experience in their new hometown. On the question of who engages in sexist behavior, men and/ or women, the authors are clear: men are the purveyors of discrimination in the market (whether women are hired for or promoted to certain jobs), and women determine norms (or residential sexism) that influence such outcomes as marriage and fertility.

The authors conduct a number of rigorous tests based on a broad array of data to reach their conclusions about women’s wages, their labor force participation relative to men, and the ages at which women aged 20-40 married and had their first child. For example, their information on sexism comes from the General Social Survey (GSS), which is a nationally representative survey that asks respondents various questions, among others, about their attitudes or beliefs about women’s place in society.

Sexism affects women through two channels: one is their own preferences that are shaped by where they grow up, and the other is the sexism they experience in the place they choose to live as adults.

The authors reveal how prevailing sexist beliefs about women’s abilities and appropriate roles affect US women’s socioeconomic outcomes. Studying adults who live in one state but who were born in another, they show that sexism in a woman’s state of birth and in her current state of residence both lower her wages and likelihood of labor force participation, and lead her to marry and bear her first child sooner. The sexism a woman experiences where she was raised, or background sexism, affects a woman’s outcomes even after she is an adult living in another place through the influence of norms that she internalized during her formative years. Further, the sexism present where a woman lives (residential sexism) affects her non-labor market outcomes through the influence of prevailing sexist beliefs of other women where she lives. By contrast, residential sexism’s effects on her labor market outcomes seem to operate chiefly through the mechanism of market discrimination by sexist men. Finally, and importantly, the authors find sound evidence that prejudice-based discrimination, undergirded by prevailing sexist beliefs that vary across space, may be an important driver of women’s outcomes in the US.

CLOSING TAKEAWAY By studying adults who were born in one place but live in another, the authors reveal the effects of sexism on women’s outcomes in the market through discrimination (wages and jobs), as well as in non-market settings through cultural norms (marriage and fertility).

Sexism and Misogyny: Unpacking Patriarchy and Its Handmaids

Challenging the sexism and misogyny that hurts women's health and wellness..

Posted May 5, 2022 | Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

- Gender, sexism, and misogyny profoundly affect the quality of lives of women and people along a continuum of gender identities.

- Sexism is stereotyping, discrimination, prejudice, devaluation, and marginalization targeting women, more feminine gender identities.

- Misogyny is the control, punishment, and policing of people and systems which threaten male dominance.

- All genders must check their internalized sexism that makes them prone to judge, retaliate, or keep women and gender minorities silenced.

Although gender equity continues to gain broad interest and attention , particularly with MeToo, Times Up, and other social movements, attacks on women's health, safety, and autonomy are evident with the Supreme Court's efforts to overturn Roe V. Wade .

The patriarchy remains paramount. Patriarchal oppression is the tendency for people to undervalue women (and associated traits and activities) while affording men the highest status, power, and privilege. As such, males (particularly white males) are depicted as superior to other groups.

Women with intersecting identities are more likely to become submerged in the disproportionately greater demands than their male counterparts related to caregiving and household responsibilities , structural inequalities , violence , trauma , devaluation, underpayment, and invisibility.

These experiences of sexism, violence, unequal employment, harassment, devaluation, and overburden drive health inequities and mental health problems . Because internalized sexism is so prevalent, the weight of the heavier load placed upon women is often normalized, unspoken, and implicit. It can be taboo to even speak about sexism and other 'isms,' as bringing up legitimate forms of structural oppression threatens the patriarchal structures and those that benefit from them.

Gender, sexism, and misogyny profoundly affect the quality of lives of women and people along a continuum of diverse sexes, sexual orientations, and gender identities. The effects of sexism tend to be even more acute for women of color and gender minorities. Violence against women globally affects at least 30 percent of women, and when psychological abuse is included, this extends to almost 90 percent.

The cumulative trauma of sexism drives mental distress, such as anxiety and depression , which are experienced between 1.5- and 1.3-times the rates of male counterparts . Sex differences in distress disappear when accounting for the impact of sexism, which accounts for almost 40 percent of the psychological distress among some women .

Despite sexism accounting for and driving much of the distress women and gender minorities experience, misogyny is normalized, internalized, and tends to be relegated invisible. If patriarchy is the tool, then sexism and misogyny are its handmaids. Sexism is stereotyping, discrimination , prejudice, devaluation, and marginalization targeting women, more feminine gender identities, and sexual minorities based on sex.

Misogyny is the control, punishment , and policing of people and systems which threaten male dominance.

The pandemic exacerbated already existing gender disparities. Stressors have been particularly acute during thin times (times of lowered internal and external resources and supports) such as the pandemic, which has tested the functioning of all systems immediately and directly. The COVID-19 pandemic has proven to be acutely and chronically stressful , particularly for families, children, and women .

The rates of depression and anxiety increased twofold among women in comparison with men during the pandemic; the odds of experiencing depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress were 2–3 times higher for women who experienced health-related socioeconomic risks, such as food insecurity, inadequate housing, violence, transportation difficulties, etc. Indeed, the pandemic and other thin times tend to exacerbate already overburdened women, who are left to juggle multiple, often conflicting roles.

Struggles to challenge patriarchal power structures are not coincidental; they are a result of misogyny—misogynistic forms of social control cast women who speak up as villains. Women and gender minorities' understandable grievances are often dismissed as “complaints” in their own families and social circles when they acknowledge the systematic forces that keep them down.

When the endemic of implicit and normalized sexism is made explicit, it threatens patriarchal structures and associated privileges. Challenging gender inequities causes discomfort for 1.) those who benefit from privilege; 2.) for those who rely on their adherence to patriarchal social structures for their livelihood and relationships; and 3.) for vast the majority of people who have been socialized into internalizing sexism.

Women may be shunned for stating the truth about gender inequities, despite experiencing the consequences of the truth every day. Subtle or overt silencing of women who speak up is misogynistic. The message is that if women would only just stay silent and “get along,” all would be well. Sure, all would be well—for those already set up to be well by the structures.

When women step out of misogynistic gender norms, internalized sexism causes all sorts of alarms, warnings, and red alerts may go off—for both women and men. People may think they are responding to some personality trait–they just weren’t “likable,” or there is just something "about them."

However, these perceptions are often smokescreens for internalized sexism and misogyny that target women who step out of gendered stereotypes–those who are leaders, assertive , or advocate for human rights. When women state hard truths and discuss topics people find unsettling, they may be stigmatized, dismissed, or vilified as “angry women.”

Paulo Freire (2008) states that people can commonly fear change. When women are seen as breaking the rules or retaliated against, they may escape to the familiar gender congruent roles of agreeableness and acquiesce to powers to “be liked,” which may provide a false sense of security. These alert buttons have been socialized and installed for all genders and by the sexist systems that socialize people into the patriarchal societies—which the majority of people in the world find themselves in.

To make progress, all genders must take risks, speak up when experiencing or witnessing injustice, stop being complicit in misogynistic social controls and support, make space, and be allies and accomplices seeking gender equity.

All genders must check their internalized sexism that makes them particularly prone to judge, retaliate, or keep down women who try to advocate for human rights of safety, security, autonomy, and liberation. On social media , are you only “liking” when women and girls post things in line with traditional gender norms, or are you also supportive of when women are strong, assertive, confident, and advocate?

Do you appreciate girls for their intelligence and physicality, or dress them up as dolls in pretty dresses, placing them in boxes where they gain acceptance only when they conform to suffocating gender and overburdened gender roles? This subtle preference, social control, and misogyny continue to damage women and girls, limiting their horizons and what they can dream and contribute to the broader world.

Challenging patriarchal social systems is a difficult yet necessary skill for liberation and transcendence from sexism. Sexism hurts men, too, as very few men are aligned with the toxic masculinity they may be socialized into. Men can use their privilege to challenge sexism and misogyny with less risk of backlash.

Postponing liberation causes symptoms to come out sideways, in the greater mental, physical, and social health consequences that affect women and gender minorities. Making explicit the gendered challenges and realities of life while being honest about the consequences is necessary to have a quality life more closely aligned with one's authentic self.

Borrell, C., Artazcoz, L., Gil-González, D., Perez, K., Perez, G., Vives-Cases, C., & Rohlfs, I. (2011). Determinants of perceived sexism and their role on the association of sexism with mental health. Women & Health, 51(6), 583-603. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2011.608416

Freire, P. (2008) Pedagogy of the Oppressed (30th Anniversary Edition), New York, Continuum.

Klonoff, E. A., Landrine, H., & Campbell, R. (2000). Sexist discrimination may account for well-known gender differences in psychiatric symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24(1), 93-99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01025.x

Landry, L. J., & Mercurio, A. E. (2009). Discrimination and women’s mental health: The mediating role of control. Sex Roles, 61(3), 192-203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9624-6

Leonard, J. (2021). What are the psychological effects of gender inequality? https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/psychological-effects-of-gend…

World Health Organization. (2021b). Gender and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/gender-and-hea…

Lindau, S. T., Makelarski, J. A., Boyd, K., Doyle, K. E., Haider, S., Kumar, S., ... & Lengyel, E. (2021). Change in Health-Related Socioeconomic Risk Factors and Mental Health During the Early Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey of you Women. Journal of Women's Health. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8879

Manne, K. (2017). Down girl: The logic of misogyny. Oxford University Press.

Mays, V. M., & Cochran, S. D. (2001). Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American journal of public health, 91(11), 1869-1876. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1869

World Health Organization.(2021a). Violence against women. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Catherine McKinley, Ph.D., LMSW, is an associate professor at the Tulane University School of Social Work.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

What does gender equality look like today?

Date: Wednesday, 6 October 2021

Progress towards gender equality is looking bleak. But it doesn’t need to.

A new global analysis of progress on gender equality and women’s rights shows women and girls remain disproportionately affected by the socioeconomic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, struggling with disproportionately high job and livelihood losses, education disruptions and increased burdens of unpaid care work. Women’s health services, poorly funded even before the pandemic, faced major disruptions, undermining women’s sexual and reproductive health. And despite women’s central role in responding to COVID-19, including as front-line health workers, they are still largely bypassed for leadership positions they deserve.

UN Women’s latest report, together with UN DESA, Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The Gender Snapshot 2021 presents the latest data on gender equality across all 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The report highlights the progress made since 2015 but also the continued alarm over the COVID-19 pandemic, its immediate effect on women’s well-being and the threat it poses to future generations.

We’re breaking down some of the findings from the report, and calling for the action needed to accelerate progress.

The pandemic is making matters worse

One and a half years since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, the toll on the poorest and most vulnerable people remains devastating and disproportionate. The combined impact of conflict, extreme weather events and COVID-19 has deprived women and girls of even basic needs such as food security. Without urgent action to stem rising poverty, hunger and inequality, especially in countries affected by conflict and other acute forms of crisis, millions will continue to suffer.

A global goal by global goal reality check:

Goal 1. Poverty

In 2021, extreme poverty is on the rise and progress towards its elimination has reversed. An estimated 435 million women and girls globally are living in extreme poverty.

And yet we can change this .

Over 150 million women and girls could emerge from poverty by 2030 if governments implement a comprehensive strategy to improve access to education and family planning, achieve equal wages and extend social transfers.

Goal 2. Zero hunger

The global gender gap in food security has risen dramatically during the pandemic, with more women and girls going hungry. Women’s food insecurity levels were 10 per cent higher than men’s in 2020, compared with 6 per cent higher in 2019.

This trend can be reversed , including by supporting women small-scale producers, who typically earn far less than men, through increased funding, training and land rights reforms.

Goal 3. Good health and well-being

Disruptions in essential health services due to COVID-19 are taking a tragic toll on women and girls. In the first year of the pandemic, there were an estimated 1.4 million additional unintended pregnancies in lower and middle-income countries.

We need to do better .

Response to the pandemic must include prioritizing sexual and reproductive health services, ensuring they continue to operate safely now and after the pandemic is long over. In addition, more support is needed to ensure life-saving personal protection equipment, tests, oxygen and especially vaccines are available in rich and poor countries alike as well as to vulnerable population within countries.

Goal 4. Quality education

A year and a half into the pandemic, schools remain partially or fully closed in 42 per cent of the world’s countries and territories. School closures spell lost opportunities for girls and an increased risk of violence, exploitation and early marriage .

Governments can do more to protect girls education .

Measures focused specifically on supporting girls returning to school are urgently needed, including measures focused on girls from marginalized communities who are most at risk.

Goal 5. Gender equality

The pandemic has tested and even reversed progress in expanding women’s rights and opportunities. Reports of violence against women and girls, a “shadow” pandemic to COVID-19, are increasing in many parts of the world. COVID-19 is also intensifying women’s workload at home, forcing many to leave the labour force altogether.

Building forward differently and better will hinge on placing women and girls at the centre of all aspects of response and recovery, including through gender-responsive laws, policies and budgeting.

Goal 6. Clean water and sanitation

In 2018, nearly 2.3 billion people lived in water-stressed countries. Without safe drinking water, adequate sanitation and menstrual hygiene facilities, women and girls find it harder to lead safe, productive and healthy lives.

Change is possible .

Involve those most impacted in water management processes, including women. Women’s voices are often missing in water management processes.

Goal 7. Affordable and clean energy

Increased demand for clean energy and low-carbon solutions is driving an unprecedented transformation of the energy sector. But women are being left out. Women hold only 32 per cent of renewable energy jobs.

We can do better .

Expose girls early on to STEM education, provide training and support to women entering the energy field, close the pay gap and increase women’s leadership in the energy sector.

Goal 8. Decent work and economic growth

The number of employed women declined by 54 million in 2020 and 45 million women left the labour market altogether. Women have suffered steeper job losses than men, along with increased unpaid care burdens at home.

We must do more to support women in the workforce .

Guarantee decent work for all, introduce labour laws/reforms, removing legal barriers for married women entering the workforce, support access to affordable/quality childcare.

Goal 9. Industry, innovation and infrastructure

The COVID-19 crisis has spurred striking achievements in medical research and innovation. Women’s contribution has been profound. But still only a little over a third of graduates in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics field are female.

We can take action today.

Quotas mandating that a proportion of research grants are awarded to women-led teams or teams that include women is one concrete way to support women researchers.

Goal 10. Reduced inequalities

Limited progress for women is being eroded by the pandemic. Women facing multiple forms of discrimination, including women and girls with disabilities, migrant women, women discriminated against because of their race/ethnicity are especially affected.

Commit to end racism and discrimination in all its forms, invest in inclusive, universal, gender responsive social protection systems that support all women.

Goal 11. Sustainable cities and communities

Globally, more than 1 billion people live in informal settlements and slums. Women and girls, often overrepresented in these densely populated areas, suffer from lack of access to basic water and sanitation, health care and transportation.

The needs of urban poor women must be prioritized .

Increase the provision of durable and adequate housing and equitable access to land; included women in urban planning and development processes.

Goal 12. Sustainable consumption and production; Goal 13. Climate action; Goal 14. Life below water; and Goal 15. Life on land

Women activists, scientists and researchers are working hard to solve the climate crisis but often without the same platforms as men to share their knowledge and skills. Only 29 per cent of featured speakers at international ocean science conferences are women.

And yet we can change this .

Ensure women activists, scientists and researchers have equal voice, representation and access to forums where these issues are being discussed and debated.

Goal 16. Peace, justice and strong institutions

The lack of women in decision-making limits the reach and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergency recovery efforts. In conflict-affected countries, 18.9 per cent of parliamentary seats are held by women, much lower than the global average of 25.6 per cent.

This is unacceptable .

It's time for women to have an equal share of power and decision-making at all levels.

Goal 17. Global partnerships for the goals

There are just 9 years left to achieve the Global Goals by 2030, and gender equality cuts across all 17 of them. With COVID-19 slowing progress on women's rights, the time to act is now.

Looking ahead

As it stands today, only one indicator under the global goal for gender equality (SDG5) is ‘close to target’: proportion of seats held by women in local government. In other areas critical to women’s empowerment, equality in time spent on unpaid care and domestic work and decision making regarding sexual and reproductive health the world is far from target. Without a bold commitment to accelerate progress, the global community will fail to achieve gender equality. Building forward differently and better will require placing women and girls at the centre of all aspects of response and recovery, including through gender-responsive laws, policies and budgeting.

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Sustainable development agenda

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions

- Reports of sessions

- Key Documents

- Brief history

- CSW snapshot

- Preparations

- Official Documents

- Official Meetings

- Side Events

- Session Outcomes

- CSW65 (2021)

- CSW64 / Beijing+25 (2020)

- CSW63 (2019)

- CSW62 (2018)

- CSW61 (2017)

- Member States

- Eligibility

- Registration

- Opportunities for NGOs to address the Commission

- Communications procedure

- Grant making

- Accompaniment and growth

- Results and impact

- Knowledge and learning

- Social innovation

- UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

Sexism: Discrimination against women and girls

Every day in every country, women and girls are discriminated against because of their gender.

Gender-specific discrimination and breaches of human rights have fatal consequences for the health, education, income and safety of women and children. In spite of numerous treaties and laws intended to help ensure equal rights and protection for women and girls, the part of the world’s population seen by others to be female still frequently experiences discrimination, abasement and violence.

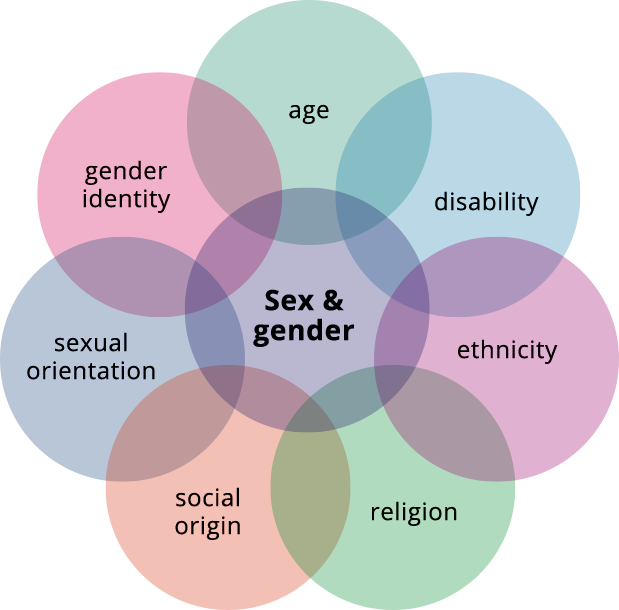

Sometimes discrimination is not immediately obvious. Examples are a lack of promotions for women, or an education for girls which leads them to believe they are no good at mathematics. In contrast, discrimination is sometimes very obvious and easily measurable: How high is the proportion of women in parliament? How many girls are completing secondary education? Further, women and girls are also frequently affected by several different forms of discrimination at the same time: due to their ethnicity, their sexual orientation, their age and/or their migration background, for example.

Definition: What is discrimination?

Discrimination is a breach of human rights. People are unjustly disadvantaged, abased and/or treated as inferior because they belong to a group that has particular characteristics or features. These characteristics could include, for example, gender, ethnicity or religion. Discrimination generally occurs because of particular value judgments, unreflected or even subconscious attitudes, and prejudices.

Definition: What is sexism?

Sexism is a synonym for gender-based discrimination. If a person’s biological sex or gender is the reason for someone else discriminating against them, then this is sexism. In general, sexism happens because of underlying attitudes that consider women to have less value than men, so this form of discrimination is usually directed against people who are seen as female or feminine. Of course, sexism can affect males as well. Closely connected to sexist discrimination are the notions of specific social activities and characteristics being more suitable for either males or females (‘gender roles’) and other stereotypes which are attributed to a person on the basis of sex or gender. Sexualised violence is one form of gender-based violence and is one way that sexist discrimination manifests. The term sexism was coined by the American women’s movement in the 1960s, combining the word ‘sex’, to refer to the biological sex, with the ending ‘-ism’ from another common form of discrimination: racism.

What are the causes of sexism?

Various studies show: The main causes for gender-specific discrimination are to be found in

- misogynist attitudes, values and role models,

- norms shaped by patriarchy , and

- cultural and religious practices.

There is a systematic nature to the disadvantages put in the way of women and girls in their access to food, healthcare, education and income. It is anchored within societal structures.

What is gender?

In English, the two terms gender and sex are sometimes used interchangeably, but sex often refers specifically to biological differences, while gender more often refers to cultural and social differences. Gender therefore refers to socially constructed norms, assignments and roles which can be different from one society to another. Where someone assumes a gender role which is visibly different from their biological sex, this can also trigger discrimination.

FAQ: What forms does this discrimination take?

Structural discrimination is a term used when the discrimination against individual groups is caused by the way that a society is organised. For example, a patriarchal society will have patriarchal gender structures that lead to discrimination against women. Structural discrimination frequently culminates in violence: for women and girls between 15 and 44, the risk of experiencing rape and violence within their family is higher than risk of becoming a victim of a traffic accident, war, cancer or malaria.

Direct discrimination is generally easy to recognise, especially in the form of laws and regulations. One example was in 2015 in Sierra Leone, where a law was introduced which prohibited pregnant girls from attending school.

Indirect discrimination is often more difficult to recognise. One example would be at a workplace where the company does not offer any chance of promotion to part-time employees: if part-time employees are overwhelmingly female, then this discriminates indirectly against women.

Intersectional or multiple discrimination is present when a person is affected by different forms of discrimination at the same time. One form can impact on another and they can even amplify each other. For example, refugee women frequently suffer both sexism and racism.

Discrimination is extremely closely related to both the abuse of power and the retention of power. This is often combined with humiliation, such as in the cases of bullying and mobbing. Another example is sexualised harassment, which is a consequence of structural discrimination in the context of patriarchal power relationships. Suggestive looks, undesired touches, or sexualised comments are used by one person in front of others to demonstrate their superiority and power over women or people who deviate from prevailing gender norms, to humiliate them, and to devalue them . Violence is also a means to preserve power.

The term patriarchy is derived from Greek and literally translated it means “rule of the fathers”.

Patriarchal power extends well beyond the immediate family. It includes a social order which gives men a privileged position of power in all spheres of life. From this position of power, men then determine the values and norms of the society and lay down the laws governing the behaviour of women and other marginalised groups, such as LGBTIQ*, people with disabilities, or people of colour.

From a feminist perspective, patriarchy refers to the totality of the exploitation and oppression of women. This oppression is systemic. At its core is the sexual control exercised by men over women.

Efforts to adopt gender-neutral or gender-inclusive language include, for example, the avoidance of a generic masculine ‘he’ when referring to humans in general. In some languages, nouns and terms for professions, for example, have an inherent gender indicated by a particular word-ending. So efforts need to be made not to exclude women and non-binary people. One example could be using the term police officer instead of the term policeman. This is important because language influences how we think and feel. For example, references to “manned spaceflight” might lead to the subconscious association of astronauts as being typically male, whereas the conscious use of “crewed spaceflight” would be inclusive because the word “crew” covers all possible genders.

Definition: Gender equality

The equal rights of the genders is a fundamental human right. Equal rights means that all humans have the same rights. The term is based on Articles 1 and 2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights , which state that all humans are “born free and equal in dignity and rights”, so should not be discriminated against due to their gender or other reasons. Often, equal rights is talked about in connection with equal opportunities. Equal rights does not mean that all humans are the same or should be the same.

What is the difference between equality and equal rights?

The principle of equal rights emphasises the same rights to be enjoyed by all people, regardless of their gender. In contrast, the principle of equality aims to overcome structural discrimination to such an extent that women and men not only receive the same rights and opportunities, but also achieve the same results from these. Examples here would include equal proportions of the genders among members of parliament or on the boards of leading companies. One way of achieving this could be setting quotas.

”In order to finally achieve gender justice, there can no longer be any tolerance for sexualised violence against women and girls! This violence suggests that the female body is something anyone can do anything with, but this is not true. False attitudes and messages such as this are passed on to girls and boys, creating stereotypical gender images that persist from generation to generation. Society’s power relations will not change unless there is a fundamental shift in these attitudes, messages and images.“ Monika Hauser, founder of the international women’s rights organisation medica mondiale

How equal rights would benefit everyone

Gender justice is more than merely a question of human rights: the equal participation of women in all aspects of life is also a prerequisite for a peaceful, just and sustainable world. Some figures:

- An increase of 30% would be seen in agricultural yields if all women had fair access to the means of production.

- Where women are involved in peace negotiations , the chance of these agreements being upheld increases by 20 per cent.

- Violence against women and girls is widespread around the world in all cultures, religions and societies. It is rooted in the power imbalance between the genders. Actual equal rights and the dismantling of these power imbalances would take away the basis for this violence.

- Studies have shown that the nourishment, health and education of children all improve when their mothers have more income available.

- According to McKinsey management consultancy, companies with higher proportions of female staff are more likely to be successful.

- Data from 90 countries indicates that countries with higher female parliamentary representation are more likely to set aside protected land areas. Another study in 130 countries showed that women are more willing to ratify international environmental treaties .

Equal rights – on the statute books or in practice?

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Article 1 states that all people are equal. Article Two of this proclamation by the United Nations (UN) goes into more detail: “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.” However, the rights that the UN General Assembly agreed in 1948 are still being violated decades later, are still not enshrined in national laws, are still not being upheld by political means, and are therefore still not a lived experience for many.

The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

In 1979, the General Assembly of the United Nations passed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Known as the Women’s Rights Convention, this Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women obliges the states ratifying it to take active steps to eliminate the discrimination against women in the areas of culture, society, education, politics and legislation.

Examples: Discrimination against women and girls around the world

Right to social welfare

Nutrition : Where food becomes scarce, it is the women and girls who suffer most from hunger. With regard to those suffering moderate or severe food insecurity, the difference between men and women increased further during the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2021, food insecurity affected 150 million more women than men in the world.

Poverty: During the Covid-19 pandemic, millions of women lost their jobs and livelihood . Sectors with higher proportions of women workers were most severely affected by the consequences of the pandemic.

Right to own property

It is women who frequently lose out on access to land: less than 20 per cent of landowners worldwide are women. However, it is the women who perform the major share of the work in the fields.

Right to education

First, the good news: Looked at globally, the rates of schooling for both primary and secondary levels are increasing for girls and boys. However, in the countries affected by insecurity, conflicts and violence, girls are 2.5 times more likely than boys to be prevented from going to school. At secondary level, this probability is 90% higher. Almost two thirds of all adult illiterates are women .

Right to life, liberty and security of person

Forced marriage: Estimates are that 12 million underage girls are forced into marriage each year.

Physical self-determination: Globally, pregnant people do not have easy access to safe and legal pregnancy termination . Abortions are often not even possible for women who were raped during wars and become pregnant as a consequence. This is not only because of the lack of medical possibilities, but mainly because pregnancy termination is forbidden by the provisions of international funders or restrictive laws and interpretations of faith. For example, since 2021 abortions have been either illegal or very difficult to access in Poland, Hungary and the USA. As a consequence 45 per cent of all pregnancy terminations around the world take place in unsafe conditions – sometimes with fatal consequences for the women: unsafe abortions are one of the most frequent causes of maternal mortality.

Violence: Almost one in three women will be subjected to violence during her lifetime. Globally, each year some 50,000 women are killed by their partner or a relative. Female genital cutting (also known as female genital mutilation, FGM) is a violation of human rights. In spite of international condemnation and national laws, more than 200 million women and girls have been subjected to FGM. In one out of every four cases, the girl dies from the consequences. Most of these were not older than 15 years when the violent cutting occurred.

Human trafficking: 72 per cent of all victims of human trafficking are women or girls. Most of these (77 per cent) are exploited sexually and/or forced into prostitution.

Wars and conflicts: In almost every conflict, warring parties use sexualised violence as an instrument of power to terrorise their enemies. Violence and sexualised attacks are also faced by women and girls as they flee their homes seeking refuge or after being displaced by advancing forces.

Humanitarian aid: In emergency situations, the stress and pressure on women and girls grow because they are the ones who usually look after children and sick relatives, find and cook food, and take care of the home. However, humanitarian aid projects are often designed with too little consideration for this. For example, in refugee camps there may be no access to or space for gynaecological and obstetric healthcare, or even gender-separate toilets and washing facilities. Registration for aid generally occurs in the name of the male head of household, which denies wives, mothers and daughters any independent access to assistance.

Climate change: In many rural areas of Africa and Asia, it is still usual for women to work near their home. This means they often receive life-saving information about disasters or severe weather later than men or not at all. This is one reason for the higher female fatalities in the wake of natural disasters. Additionally, in emergency accommodation there is an increased risk of sexual harassment.

Political representation

Worldwide, 26 per cent of members of parliament are female. In most of the countries where the proportion of women in parliament is above 30 per cent a quota ruling had been introduced in order to strengthen political participation of women. With success: In Rwanda the figure of 61 per cent (as of April 2022) is the highest proportion of women in parliament in the world. In Cuba it is more than 53 per cent and in Mexico 50 per cent. In 28 of 193 countries , women are head of state or government, including , Bangladesh, New Zealand and Tanzania.

”Although all humans have a right to self-determination this is regularly denied to women and girls.. Unfortunately, this is a global phenomenon which we see in, for example, Serbia, Liberia, Afghanistan or Germany. In Europe, there is currently a trend to further restrict women’s rights.“ Jessica Mosbahi, Advocacy and Human Rights Officer

Discrimination against women in Germany – some examples

Women face discrimination in Germany. Four examples:

Politics: 34.7 per cent of the Members of the Bundestag are women (after the election in 2021). Twelve federal states are governed by men, only four by women. At a local level, the differences are even more severe: In 2021, 80 per cent of German mayors were male.

Economy: Female staff earn on average 18 per cent less than their male colleagues. The income gap has reduced a little in recent years, but in comparison to the European average (13 per cent), the gender pay gap in Germany is still high. Furthermore, women face professional disadvantages due to pregnancy and maternal leave, and are less likely to be selected for promotion.

Legislation: §218 of the German Penal Code violates the right to self-determination. Women who want to terminate their pregnancy, and all of those involved in carrying out abortions, are being criminalised. This is the case despite access to legal and safe abortions being a human right.

At home: Statistically speaking, once every 2.5 days in Germany, a woman is killed by her partner or ex-partner. In 2021, 161,000 survived what is euphemistically called ‘domestic violence’ – two thirds of them were women.

From the practical experience of our partner organisations: Against sexism

Ensuring the right to healthcare

Violence against women is a worldwide problem, but in war and post-war countries the rates are particularly high. Compared with the great need, there is very little provision of assistance for those affected. The staff of healthcare clinics have generally not received appropriate training. Frequently, healthcare professionals exhibit prejudices and discriminatory behaviour when treating survivors, leading to stigmatisation and feelings of shame. Our partner organisations train doctors, midwives and nursing staff locally. They learn how to offer beneficial support to women affected by violence. In a second step, these specialist staff then learn how to pass on the training to their colleagues. In this way, the knowledge about trauma-sensitive support can be anchored in their community for the long term.

Appeal against a ban on pregnant girls attending school

In Sierra Leone, a law was passed in 2015 that prohibits pregnant girls from attending school. The law is unconstitutional. This affects a large number of girls since the pregnancy rate for under-18s is one in three. A group of activists took legal action against this – successfully. One of the plaintiffs was the organisation WAVES (Women Against Violence and Exploitation Society), which medica mondiale has been cooperating with since 2019.

More on sexism and discrimination

Sexism: Gender, Class and Power Essay

Introduction.

Sexism is one of the challenges that most societies in the contemporary world have struggled to address without any meaningful progress. It refers to discriminatory or abusive behavior towards members of the opposite sex. Although anybody is vulnerable to sexism, it is majorly documented as a problem faced by women and girls. According to psychologists, the challenge of sexism is necessitated by factors such as gender roles and stereotypes across various societies (Dawson, 2018).

Over the years, various human rights groups have made an effort to create awareness about sexism and the probable dangers the victims might be exposed to if effective management strategies are not put in place. Research has established that in societies where sexism is highly rooted, victims are often vulnerable to rape and sexual harassment (Brewington, 2013). Cases of sexism against women are very common in the workplace.

Women are very vulnerable to sexual harassment in the workplace as their male colleagues and bosses often ask for sexual favors in exchange for promotions and salary reviews (Tulshyan, 2016). Women also argue that they are often overlooked in leadership positions because men are considered to have a better chance of succeeding. Sexism is a deep-rooted societal vice that ought to be eliminated in order to promote the value of humanity.

Since the turn of the century, people are more vocal with regard to the danger of sexism. Social networking sites are one of the platforms that people have used to highlight the challenges faced by victims of sexism and offer solutions to the problem. In 2012, the infamous Everyday Sexism project was launched with an aim to expose the numerous acts of sexism across the United Kingdom. The project quickly got the attention of the world as people gave shocking reactions to the degree to which the vice was rampant, especially in the streets (Brewington, 2013).

According to research, social media, as well as print and electronic media, have contributed greatly to the advancement of sexism regardless of the fact that they are also being used to fight the vice. For example, the contemporary hip-hop music industry in the United States has been accused of promoting sexism through their music videos. The genre has led to women being viewed more from a sexual angle because of the way they appear in the music videos.

These videos are aired across major television channels and readily available for consumption by the global audience through YouTube. Fashion magazines have also contributed to the growing challenge of sexism, especially towards women, because the artistic presentation of the female body is angled in a sexual manner (Brewington, 2013).

Apart from the inappropriate portrayal of human bodies by media, sexism is highly prevalent in modern society in several other ways. In the workplace, women often complain of the general assumption that men are more qualified and knowledgeable compared to women (Tulshyan, 2016). It is frustrating for women when a colleague seeks advice or clarification from a male peer when they know that they are in a better position to do the same. Women also consider the inability of an employer to allocate a certain task to them simply because they are physically demanding as an act of sexism (Dawson, 2018).

Women go to the gym and participate in various sports just as men do. Thus, it is wrong to assume they cannot meet the physical demands of a task. Psychologists argue that sexism is a relative concept with regard to the way various societies explain and comprehend it. This is evidenced in the different actions or elements that are considered as being sexist. In some societies, the fact that women are made to change their surname when they get married is considered sexism. Women feel that it is not necessary for them to give up their last name because of a process that even men undergo, yet they get to retain theirs (Brewington, 2013).

Another common form of sexism is sexist language. Studies have established that men are less vulnerable compared to women when it comes to sexual objectification when being addressed. It is important for people to use gender-sensitive language, especially in situations where both men and women are involved. For example, it is wrong to use masculine generics such as “Chairman” when referring to a female leader. Instead, one should use a gender-sensitive term such as chairperson (Lipman, 2018).

It is also an act of sexism to refer to a group of people with both men and women as “Guys” because it creates an impression that women are a category below men as human beings. It is also a common occurrence to hear men referring to adult women as girls. This often infantilizes a woman because it makes one feel like the person addressing her is giving an indication that they are not mature.

The most unfortunate thing about sexist language is the casual manner in which it has been used over the years, to the extent that it has become part of the conventional glossary. This is one of the major challenges facing the fight against sexism. Objectification of women through sexist language is rooted in the stereotypes the society develops from the way girls are raised and theories about their beauty (Evans, 2016). Over the years, women have been used to market products through various forms of advertisements. This has influenced girls to believe that they are as valuable as they look. Therefore, any woman whose beauty fails to meet societal standards tends to feel less valuable.

Sexism has robbed women of their safety, comfort, and voice. Many women who have been a victim of street harassment from men argue that such experiences act as an affirmation that their bodies are owned by the society (Brewington, 2013). Due to laxity within the society, women are made to unwillingly take street harassment as intended compliments rather than abuse. Domestic violence is a form of sexism that has taken away the voice of women.

In many societies, many cases of domestic violence against men and women end up unreported because the victims know they will not get any help with ease. It’s a human rights violation that often demeans the victim because the violator perceives the victim as being weak (Evans, 2016). Unfortunately, domestic violence is legal in places such as the United Arab Emirates, where husbands are allowed to discipline their wives as long as they do not inflict visible injuries.

South Asia is common for practicing a form of sexism called Gendercide. It involves the killing of children of a specific gender. It is close to gender-selective-abortion, where women are forced to terminate their pregnancies depending on the sex of the unborn child. In these practices, girls are targeted more than boys. The same case applies to female genital mutilation, which human rights groups consider as the gravest form of sexism (Evans, 2016).

In contemporary society, technology is widely abused to advance sexist agendas. Women always complain of suffering rape anxiety because people use phone calls and social media posts to deliver threats. No one chooses to be a victim of sexism; thus, avoiding walking in the streets unaccompanied or with people of the same gender is not enough. Cyberbullying is a strategy widely used by sexist people to harass their targets. The internet has turned the world into a global village.

Thus cultural interaction has been greatly heightened (Brewington, 2013). This effect is manifested a lot in the fashion industry, where the dres’ codes for men and women have undergone a huge transformation. Psychologists argue that dres’ codes are sexist in nature. They often limit the power and confidence of women, depending on the societal perception of a certain trend. The style of women wearing pants started in the developed countries as a way of helping women address the threat of rape. Several decades later, it has become a global trend. Some women argue that their lies in wearing dresses, but they are often forced to wear pants for safety purposes (Evans, 2016).

The concept of sexism is very broad and cannot be explained exhaustively. However, it is common knowledge that there is an urgent need to address this global challenge in order to achieve the common good. Gender equality and sensitivity is a right of every human being, thus the need to ensure that we create a more inclusive society. In order to achieve this feat, a change in attitude with regard to the way different genders perceive each other is very important. Men need to understand that they are not biologically programmed to harass women or objectify them.

Brewington, C. (2013). The sacred place of exile: Pioneering women and the need for a new women’s missionary movement . New York, NY: Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Dawson, T. (2018). Gender, class and power: An analysis of pay inequalities in the workplace . New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Evans, M. (2016). The persistence of gender inequality . New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Lipman, J. (2018). That’s what she said: What men need to know and women need to tell them about working together . New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Tulshyan, R. (2016). The diversity advantage: Fixing gender inequality in the workplace . New York, NY: Create Space Independent Publishing Platform.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, May 7). Sexism: Gender, Class and Power. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/

"Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." IvyPanda , 7 May 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Sexism: Gender, Class and Power'. 7 May.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

1. IvyPanda . "Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

- Sexism Against Women in the Military

- Sexism as Perceived by the Young Men

- Sexism in the English Language

- Strategies to Combat Sexist Language

- Sexism and Male Nurses

- It’s His Right, It’s Her Duty: Benevolent Sexism and the Justification of Traditional Sexual Roles-Journal

- Sexism in the English Language Issue

- When Men Experience Sexism Article by Berlatsky

- Canadian Society: Sexism and the Persistent Woman Question

- Misogyny and Sexism in Policing

- The Restricted Status of Women in Pakistan

- Diversity Organizations and Gender Issues in the US

- Gender Discrimination in the United States

- Gender Inequality Index 2013 in the Gulf Countries

- Feminist Perspective: “The Gender Pay Gap Explained”

- Choose language

- Azərbaycanca

- Nedersassisch

Sexism is any expression (act, word, image, gesture) based on the idea that some persons, most often women, are inferior because of their sex.

Sexism is harmful . It produces feelings of worthlessness, self-censorship, changes in behaviour, and a deterioration in health. Sexism lies at the root of gender inequality. It affects women and girls disproportionately.

Sexism is present in all areas of life.

63% of women journalists have been confronted with verbal abuse

Women spend almost twice as much time as men on unpaid housework (OECD countries)

80% of women stated that they have been confronted with the phenomenon of “mansplaining” and “manterrupting” at work

Men represent 75% of news sources and subjects in Europe

In the UK, 66% of 16-18-year-old girls surveyed experienced or witnessed the use of sexist language at school

59% of women in Amsterdam reported some form of street harassment

In France, 50% of young women surveyed recently experienced injustice or humiliation because they are women

In Serbia, research indicates that 76% of women in business are not taken as seriously as men

Violence sometimes starts with a joke

Individual acts of sexism may seem benign, but they create a climate of intimidation, fear and insecurity. this leads to the acceptance of violence , mostly against women and girls..

This is why the Council of Europe has decided to act by adopting a Recommendation to prevent and combat sexism .

Sexism affects mostly women. It can also affect men and boys when they don’t conform to stereotyped gender roles.

The harmful impact of sexism can be worse for some women and men due to their ethnicity, age, disability, social origin, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or other factors.

Some groups of women, for example young women, politicians, journalists or public figures, are particular targets of sexism

of women elected to Parliament have been the target of sexist attacks on social networks

See it. Name it. Stop it.

Language and communication.

Examples of sexism in language and communications:

The generic use of the masculine gender by a speaker (“he/his/him” to refer to an unspecific person). The cover of a publication depicting men only . The naming of a woman by the masculine term for her profession. A communication campaign including gratuitous nudity . An advertisement with a man showing a woman how to use a washing machine.

Why should it be addressed?

Language and communication matter because they make people visible or invisible and recognise or demean their contribution to society. Our language shapes our thought , and the way we think influences our actions. Gender-blind or discriminatory language reinforces sexist attitudes and behaviour.

How to prevent it?

Use both the feminine and the masculine when addressing a mixed audience. Review public communication to make sure it uses gender-sensitive language and imagery. Produce manuals on gender-sensitive communication for different audiences. Promote research in this area.

Media, Internet and social media

Examples of sexism in the media:

A sexualised depiction of women in the media. An all-male TV show. Media reporting on violence against women which blames the victim . Journalists, most often women, receiving comments on social media based on their appearance instead of the issues they discuss. Internet applications sending some job adverts to men only because algorithms are built in a discriminatory way.

Children and others are bombarded with sexist media messages and influenced by them. Such messages limit their own choices in life. They give the impression that men are the keepers of knowledge and power and that women are objects and it’s ok to comment freely on their appearance. Online sexism pushes women out of online spaces . Online sexism can cause very real harm. Abusing or mocking someone online creates a permanent digital record that can be further disseminated and is difficult to erase.

Implement legislation on gender equality in media . Train media and communication professionals on gender equality. Ensure that women and men are represented in a balanced way and in diverse, non-stereotypical roles in the media . Promote advertisements that play with, and raise awareness of, gender stereotypes rather than reinforce them. Provide digital literacy training especially for young people and children. Legally define and criminalise (online) sexist hate speech . Put in place specialised services to provide advice on how to deal with online sexism .

Examples of sexism at the workplace:

The practice of unofficially excluding women who have children from career opportunities. In meetings, ignoring women , appropriating their contributions or silencing them. Favouring a man rather than a woman for a managerial position by presuming her lack of authority . Gratuitous comments about physical appearance or dress (which undermine women as professionals). Derogatory comments to men taking on caring roles. “ Mansplaining ”.

Workplace sexism undermines the efficiency of victims and their sense of belonging. Silencing through sexism means that ideas or talents are ignored or under-used. Belittling comments create an intimidating/oppressive atmosphere for those confronted with them and can degenerate in violence/harassment . Victims may develop higher anxiety levels , be more prone to outbursts and depression. More generally, sexism leads to lower salaries and fewer opportunities for those confronted with it.

Adopt and implement codes of conduct defining sexist behaviour and prevent it through training. Put in place complaint mechanisms , disciplinary measures and support services. Managers must state and show their commitment to act against sexism .

Public sector

Examples of sexism in the public sector:

Sexualised comments or comments about the appearance or family situation of politicians, most often women, including within parliaments. Comments about the sexual orientation or appearance of users by staff of public services. Sexist representations / posting of images of naked women in public workplaces (e.g. hospital staff rooms). Comments on women’s appearance in public spaces, including public transport.

The public sector has a duty to lead by example . Sexism in parliaments is very common but it limits the opportunities and freedom of women in parliaments, be they elected or staff. Sexism undermines equal access to public services . Sexism in public spaces limits women’s freedom of movement. Sexism can lead to violence and creates an oppressive environment preventing mostly women from fully participating in public life.

Training of staff. Put in place codes of conduct , complaint mechanisms, disciplinary measures and support services. Implement awareness raising campaigns , such as toolkits or posters in public space explaining what sexism is. Promote gender balance in decision-making . Promote research and the gathering of data on the issue.

Examples of sexism in the justice system:

A judge implying to a victim of sexual violence that she was ‘asking for it’ . A law professional commenting on the appearance of a woman who is a colleague. A police officer not taking an allegation of violence against women seriously or trivialising it.

Such behaviour can lead to victims dropping cases . They create distrust in the justice system. They can lead to misinformed judgments . They demean women and can push them out of legal professions .

Implement policies on women’s equal access to justice . Train legal and law enforcement professionals. Deconstruct judicial stereotyping through awareness-raising campaigns. Ensure professionals base their judgments on facts , on the behaviour of the perpetrator and the context of the case rather than the victim’s clothing, for example.

Examples of sexism in education:

Textbooks containing stereotypical images of women/men, boys/girls. The absence of women as writers, historical or cultural figures in textbooks . Career and education counselling discouraging non-stereotypical career or study choices . Teachers making comments about the appearance of pupils/students/fellow teachers. Sexualised comments to girls. Bullying of non-conforming pupils /students by fellow pupils /students or education professionals. The absence of awareness /procedures / reactions to address such sexist behaviour.

The content of education and behaviour of education professionals heavily influences perceptions and behaviour . A climate of sexism in learning establishments negatively affects the achievements of pupils/students. Sexism in education can limit future individual career and lifestyle choices .

Implement policies and legislation on gender equality in education . Review textbooks to ensure that they are free of sexism and that they depict women as well as men in non-stereotypical roles. Ensure the representation of women as scientists, artists, athletes, leaders, politicians in textbooks and programmes . Teach women’s history . Ensure the availability of complaint mechanisms. Teach gender equality issues as well as sexuality education (including consent and personal boundaries). Train education professionals on unconscious bias .

Culture and sport

Examples of sexism in culture and sport:

Sportswomen depicted in the media according to their family role and not their skills and strengths. Trivialising women’s sporting achievements . Demeaning men who play “feminine” sports. Women in sexy outfits as “decoration” in cultural or sporting events. Absence of women’s work in art exhibitions. Scarcity of meaningful roles for women in cinema and the virtual absence of roles for older actresses. Scarcity of funding for film production in which women have a leadership role. Under-resourcing of women’s art.

Both culture and sport are shapers of attitudes . If women and men are depicted in stereotyped ways, this will feed into gender stereotyping. When mostly men are visible in these areas, this influences the way women are seen as potential artists or athletes and narrows the range of role models for children and young people. Gender stereotypes limit the choice of women/men girls/boys to practice sports that are not considered “feminine” or “masculine” ; this leads to self-censorship . In both areas, sexism leads to lower salaries and fewer opportunities for those confronted with it.

Measures to encourage creative work by women and gender mainstreaming in cultural and sport policies (scholarships, exhibitions, training, provision of space/workshops). Ensure better and more media coverage of women’s sports and art. Encourage sponsors to support women’s arts and sports. Adopt codes of conduct to prevent sexist behaviour, including provision for disciplinary action in sports federations. Encourage leading sport and cultural figures to speak up against sexism and implement campaigns to denounce violence in sport and sexist hate speech.

Private sphere

Examples of sexism in the private sphere:

Women performing more unpaid (care and household) work than men, for example only women helping to wash dishes at a dinner party. Sexist jokes between friends. Systematically offering “feminine” or “masculine” toys to girls/boys. Boys being encouraged to run and take risks and girls to be docile and compliant. The use of expressions like “running like a girl” or “boys will be boys”.

Unpaid work weighs on women’s participation in the labour market, on their economic independence as well as on their participation in sport and leisure activities. Toys (e.g. a mini kitchen or a construction game) influence gender roles, but also future study or career choices. Sexist jokes can intimidate and silence people and they trivialise sexist behaviour.

Awareness-raising measures and research on the impact and the sharing of unpaid work between women and men. Measures for reconciling private and working life for all . Promotion of non-gendered toys . Encouraging boys as well as girls to participate in household tasks. Giving girls , too, the space and freedom to play, explore and be themselves.

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Sexism, Essay Example

Pages: 5

Words: 1322

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Sexism is a term used to indicate discrimination or the prejudiced faced by person based on the persons sex. Thoman, Dustin, Paul White, Niwako Yamawaki, and Hirofumi Koishi indicated that the attitude of the sexist has its origin for the stereotypes that existed traditionally in the gender roles of the people in the society (10). As a result, sexism can include the feeling that people of particular sex are superior or better than the other sex. For instance, a person seeking for a job may encounter discriminatory hiring practises because she is a woman. In such most societies, when a lady is hired for a certain job, they tend to receive unequal treatment or compensation when compared to the men working in the same capacity. The other extreme form of sexism may include sexual harassment, rape and similar type of sexual violence especially targeted towards the female gender.