An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Traditional Indigenous medicine in North America: A scoping review

Nicole redvers.

1 Department of Family & Community Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, North Dakota, United States of America

2 Arctic Indigenous Wellness Foundation, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada

Be’sha Blondin

Associated data.

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Despite the documented continued use of traditional healing methods, modalities and its associated practitioners by Indigenous groups across North America, it is presumed that widespread knowledge is elusive amongst most Western trained health professionals and systems. This despite that the approximately 7.5 million Indigenous peoples who currently reside in Canada and the United States (US) are most often served by Western systems of medicine. A state of the literature is currently needed in this area to provide an accessible resource tool for medical practitioners, scholars, and communities to better understand Indigenous traditional medicine in the context of current clinical care delivery and future policy making.

A systematic search of multiple databases was performed utilizing an established scoping review framework. A consequent title and abstract review of articles published on traditional Indigenous medicine in the North American context was completed.

Of the 4,277 published studies identified, 249 met the inclusion criteria divided into the following five categorical themes: General traditional medicine, integration of traditional and Western medicine systems, ceremonial practice for healing, usage of traditional medicine, and traditional healer perspectives.

Conclusions

This scoping review was an attempt to catalogue the wide array of published research in the peer-reviewed and online grey literature on traditional Indigenous medicine in North America in order to provide an accessible database for medical practitioners, scholars, and communities to better inform practice, policymaking, and research in Indigenous communities.

Introduction

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) was a pivotal document for the world’s Indigenous Peoples [ 1 ]. In addition to being quoted in numerous policy, research, and community initiatives since it was adopted, the declaration is now being used to evaluate the adequacy of national laws; for interpreting state obligations at the global level; and by some corporations, lending agencies, and investors in regards to resource and development opposition on Indigenous lands [ 2 ]. Article 24 of the declaration states that “Indigenous peoples have the right to their traditional medicines and to maintain their health practices, including the conservation of their vital medicinal plants, animals, and minerals” (UN document A/RES/61/295). The World Trade Organization has stated that “traditional medicine contributes significantly to the health status of many communities and is increasingly used within certain communities in developed countries. Appropriate recognition of traditional medicine is an important element of national health policy” [ 3 ].

The United Nation’s Economic and Social Council President in 2009, Sylvie Lucas, stated that “[t]he potential of traditional medicine should be fostered. … ‘We cannot ignore the potential of traditional medicine’ in the race to achieve the Millennium Development Goals and renew primary health care for those who lacked access to it … traditional medicine [is] a field in which the knowledge and know-how of developing countries was ‘enormous’—and that was a source of hope for improving the world’s health-care situation” [ 4 ].

In November 2008, member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) adopted the Beijing Declaration [ 5 ], where they recognized the role of traditional medicine in the improvement of public health and supported its integration into national health systems where appropriate [ 6 ]. The declaration also promotes improved education, research, and clinical inquiry into traditional medicine, as well as improved communication among health-care providers [ 6 ].

Research into some types of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practices has received large amounts of funding. For example, the US National Institute of Health has a division called the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), which in 2010 had a budget of US$128.8 million dollars [ 7 ]. Before the Beijing Declaration, sixty-two countries had national institutes for traditional medicine as of 2007, up from twelve in 1970 [ 4 ]. Despite this, there has been a complete lack of acknowledgement of the Indigenous traditional knowledge (TK) currently being used in many CAM professions. In some cases, there has been direct cultural appropriation of traditional medicine and practices by CAM or other biomedical groups in North America [ 8 ]. Although outdated, given the lack of scholarship in this area, a 1993 estimate put the total world sales of products derived from traditional medicines as high as US$43 billion [ 9 ]; however, only a tiny fraction of the profits were and are being returned to the Indigenous peoples and local communities from where these medicines were derived. In the early 1990s, it was estimated that “less than 0.001 per cent of profits from drugs developed from natural products and traditional knowledge accrue to the traditional people who provided technical leads for research” [ 10 ].

So, despite some progress on a global level in CAM research and practice, many Indigenous medicine systems around the world are still often given the back seat when it comes to both acknowledgement and practice within the conventional medical-care setting. The terms and attributes used for traditional medicine, such as ‘alternative’, translates into an epistemological discomfort regarding the identity of these medicines [ 11 ] that automatically sets a power differential from conventional care. In 2007, The Lancet published an article in which the authors stated, “[w]e now call on all health professionals to act in accordance with this important UN declaration of [I]ndigenous rights—in the ways in which we work as scientists with [I]ndigenous communities; in the ways in which we support [I]ndigenous peoples to protect and develop their traditional medicines and health practices; in our support and development of [I]ndigenous peoples’ rights to appropriate health services; and most importantly in listening, and in supporting [I]ndigenous peoples’ self-determination over their health, wellbeing, and development” [ 12 ].

In his 2008 dissertation, (Gus) Louis Paul Hill noted that there is a paucity of literature on Indigenous approaches to healing within Canada specifically, and little documentation and discussion of Indigenous healing methods in general [ 13 ]. With this, there is currently no formal Canadian (or US based) Indigenous health policy framework or national adopted policy on Indigenous traditional medicine [ 14 , 15 ], and no broad application and endorsement of Indigenous ways of achieving wellness markers that are self-determined in an already marginalized community (demonstrated by a lack of funding and accessibility to these services generally).

Despite this being an emerging scholarship area, with a clear lack of reflected national health policy, there is increasing evidence on the use of traditional Indigenous medicine in certain areas of need such as in substance abuse and addictions treatment [ 16 – 21 ]. When Canadian Indigenous communities were asked about the challenges currently facing their communities, 82.6% stated that the most common issue was alcohol and drug abuse [ 22 ] and that traditional medicine itself is a critically important part of Indigenous health [ 23 ], including in the support of addictions. Due to the often upstream, structural, and socio-political [ 24 ] factors driving substance abuse in addition to other health ailments in Indigenous communities, advancing co-production of treatment options such as utilizing traditional medicine that already fits into an Indigenous paradigm may ensure four key steps to wellness occur: decolonization, mobilization, transformation, and healing [ 25 ].

The present study

Despite the documented continued use of traditional healing methods, modalities, and their associated practitioners by Indigenous groups across North America, widespread knowledge of this domain is presumed elusive among most Western-trained health professionals and systems. This despite the fact that the approximately 7.5 million Indigenous peoples who currently reside in Canada and the United States (US) are most often served by Western systems of medicine. There is current exploration in the literature on how cultural competency and safety impacts health disparities across diverse populations; however, there is little attention to how traditional Indigenous medicine systems fit into this practice area. Therefore, an account of the state of the literature is currently needed in this area of traditional Indigenous medicine to provide an accessible resource tool for medical practitioners, scholars, and communities in the North American context to better understand Indigenous traditional medicine in the context of current clinical care delivery and future policy making. In addition, having baseline literature on this topic area available for use in cultural safety training, and diversity and inclusion training on or off reservations, is warranted and in need.

Considering the paucity of accessible information on traditional Indigenous medicine, in addition to the lack of cohesive understanding on what traditional healing is within the Western context, the purpose of this present study is–

- to catalogue the current state of the peer-reviewed and online grey literature on traditional medicine in the North American context by identifying the types and sources of evidence available, and

- to provide an evidence-informed resource guide for medical practitioners, scholars, and communities to better inform “practice, policymaking, and research [ 26 ]” in Indigenous communities.

The methodology for this scoping review was a mixed-methods approach (Western-Indigenous). The first four steps of the scoping review were conducted within a Western methodological approach as outlined by Pham et al. [ 27 ] and based on the framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [ 28 ] with subsequent recommendations made by Levac et al. [ 29 ] (i.e., (1) combining a broad research question with a clearly articulated scope of inquiry, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, and (4) charting the data). For the fifth step, as outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [ 28 ], (i.e., (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results), we utilized a dominant Indigenous methodology that places a focus on personal research preparations with purpose, self-location, decolonization and the lens of benefiting the community [ 30 – 32 ]. Although this research process did include the Western conceptions of collating, summarizing, and reporting the results as per outlined and described by Arksey and O’Malley [ 28 ], there was a very clear intent of identifying ourselves, the authors, as being rooted within Indigenous communities, and within an Indigenous worldview. This meant that we were not able to critique or provide commentary to contradictory evidence found in the scoping review process, as it is not culturally appropriate to provide this type of analysis within the topic area of traditional medicine through an Indigenous worldview. As Saini points out, utilizing self-determined Indigenous methodologies is “critical to ensure Aboriginal research designs are not marginalized due to perceptions that they are somehow less valid or sophisticated than their counterparts” [ 33 ] at the community or systems level.

The sixth methodologic step in our scoping review, as advanced by Levac et al. [ 29 ], incorporates a consultation exercise involving key stakeholders to inform and validate study findings [ 26 ] and was done in parallel to all steps of the work. This was another mixed-method bridging step, where one Indigenous Elder who is considered a content expert in their respective community was utilized to ensure placement of the research in the Indigenous context despite the use of Western metrics for the data-collection portion of the work (as opposed to an academic or other institutional stakeholder). It must be noted that Indigenous Elders’ engagement with research is often solely for the purpose of benefiting their community [ 30 – 32 ]. This therefore creates a unique stakeholder engagement process that roots the research not to a specific Western-defined method or process but to a set of traditional Indigenous protocols (unwritten community directives defined through an Indigenous worldview) that must be followed to ensure uptake and acceptance of the work by Indigenous communities themselves. In essence, the ‘validation of study findings’ (as outlined by Levac et al. in their sixth methodologic step [ 29 ]) is not culturally malleable and needed to be changed to a process of reviewing the rules and parameters (i.e., traditional protocols) around how traditional medicine should be talked about in the context of research. The authors are both immersed in work with Indigenous communities and peoples and understands the importance of Indigenous research processes to move away from the conformity of Western notions of the scientific deductive process of new knowledge development, and instead to work towards providing space for the translational voices within Indigenous communities and peoples [ 34 ]. The review methodology was defined a priori.

Eligibility criteria, procedures, and search terms

Only articles published in peer-reviewed academic journals or easily accessible online reputable organizational documents and dissertation works that were formally published (i.e., online grey literature) were included. No limits were put on the type of research conducted, whether qualitative, quantitative, commentary, or otherwise given the specific nature of the topic and the assumed limited studies available for review. Studies were included if they made reference to traditional medicine, or if they noted specific traditional medicine interventions or practitioners (i.e., sweat lodge, traditional healers, etc.). Ethnobotanical, plant physiology, and reviews of specific Indigenous plants were excluded from this scoping review as they were most often not based on the context of traditional medicine but the function and action of the plant itself. All studies up until June 29, 2020 were included in the review.

The authors did not specify a definition for ‘traditional medicine’ before selecting studies for this review, which was purposeful. There is currently a vast array of traditional medicine modalities, practices, and people across North America who may have varying definitions or interpretations of the terms and practice. This therefore required a broad inductive and immersive approach to allow the community of researchers in this area to provide their own definitions regionally, which therefore made an impact on the breadth of articles found. All the variants of the words for traditional medicine that were used to include articles were based on existing knowledge, a pre-screen of the available literature, and consultation with an Elder (see S1 Table and ‘title and abstract relevance screening’ section).

No restrictions were put on language for the initial search; however, only English language articles were considered for inclusion. This was also due to a complete lack of peer-reviewed articles written in an Indigenous language being noted in prior work, in addition to the prospective difficulties and budget needed to attain translation support. With a multitude of Indigenous languages in North America, there is an unfortunate lack of access to translators for projects such as these. Articles that were outside of the continental US and Canada were also excluded (i.e., Pacific Islanders, etc.), in addition to those from Mexico despite the proximity of traditional lands within and to the US. This was due to differences in traditional medicine practice and agents in those areas. Books and book reviews were not included due to the difficulty in verifying their content. North American Indigenous was defined to be First Nations, Inuit, Métis, American Indian, Alaskan Native or the respective Bands and Tribes within the region. As demographic terminology changes depending on the region of the continent, it was important to ensure complete capture of the eligible literature by utilizing both Canadian and US Indigenous terminologies. A two-stage screening process was used to assess the relevance of studies identified in the search as further outlined below.

The scoping review process and search terms were developed with the aid of a medical librarian (D.O) in discussion with the lead author (N.R.). The search was created in PubMed using a combination of key terms and index headings related to North American Indigenous peoples and traditional medicine (see S1 Table ). The search was completed between December 27, 2018 and June 29, 2020 by searching the following databases with no limits on the start date, language, subject, or type: PubMed, EMBASE, PsycInfo, Elsevier’s Scopus, PROSPERO, and Dartmouth College’s Biomedical Library database due to the breadth of databases available in this library. In addition, manual searches of the following websites were completed: Indigenous Studies Portal, University of Saskatchewan [ 35 ]; National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health [ 36 ]; the Aboriginal Healing Foundation’s archived website documents [ 37 ]; and the International Journal of Indigenous Health, which includes archives from the Journal of Aboriginal Health . Google Scholar was searched by inspecting the first two pages of results and then subsequently screening the next two pages if results were identified until no more relevant results had been found. The reference lists of randomly selected articles were manually searched with a “snowball” technique utilized to identify any further literature that may have been missed in the first search round until saturation of the search had been reached.

Title and abstract relevance screening

A title and abstract relevance form was developed by the author (N.R) in a session during the Elder consultation (B.B), mainly by the a priori identification of the search terms used and as listed in the S1 Table . As the goal was to capture as much available literature on the subject as possible, the title and abstract review were non-restrictive other than the stated eligibility criteria and search terms noted above. The reviewer was not masked to the article authors or journal names as this was not a results-based review. Some article titles did not have an abstract available for review and were therefore included in the subsequent full review to better characterize the content relevance to the topic area. If there was a question on the relevance of an article for inclusion, the Elder was brought into the discussion (B.B) as the final authority for the decision on whether to proceed with inclusion.

Data characterization, summary, and synthesis

After title and abstract screening, all the citations that were deemed relevant to the topic were kept in the scoping review database ( S2 Table ). All full text articles were obtained once identified as eligible; however, as the intent was not to provide critical review of the articles, they were not catalogued based on the completion of a full text article review. Instead, all articles were kept in the database from the title and abstract screening alone for the categorization process, ensuring that no judgement was placed on traditional medicine topics in keeping with an Indigenous methodological paradigm. Therefore a quality assessment procedure was not performed on the articles included in this scoping review as noted (e.g., Critical appraisal of qualitative research [ 38 ]) for a few reasons:

- The purpose of this review was to map the existing state of the literature on this topic and not to analyze the results of the included articles, and

- The vast array of formats and methodologies used in the Indigenous traditional medicine literature make the dominant Western metrics of validity simply not applicable to the current research purpose.

All citations found were compiled in a single Microsoft Excel 365 ProPlus spreadsheet. Coding of articles was done based on title and abstract review alone, with an Elder advisor to aid identification of categorical themes. Themes were based and developed by way of traditional knowledge (TK); however, it was noted in the synthesis process that there was often substantial overlap between themes. In these cases, a priority category was given for the ease of database creation which means that the categorical themes cannot be looked at as being black and white. Traditional Indigenous medicine is often very complex in its practice; however, an attempt was done to ease classification by assessing for the most discussed or most focused research topic(s) in each article.

Due to the substantial overlap of search terms used for traditional medicine in other disciplines (i.e., traditional medicine can be the term used from the Indigenous perspective or from the Western perspective), the initial search yielded thousands of articles.

Based on a review of the title and abstracts, 249 articles met the criteria for inclusion (see S2 Table for the full database of articles included). A full article review was conducted when the initial screen left questions about the relevance of the research for inclusion. Broad inclusion was purposeful, as by ensuring a wide capture of the literature was categorized, future research and program needs have a more complete database to pull information from. Articles ranged in date from the earliest year of publication, being in 1888, to the most recent publication, being in 2020 ( Fig 1 ). Sixty two percent of the articles were published prior to 2009 (n = 154) with the average year of publication being 2001.

There were five overlapping categorical themes that emerged in the review including: General traditional medicine, integration of traditional and Western medicine systems, ceremonial practice for healing, usage of traditional medicine, and traditional healer perspectives. Fig 2 summarizes the selection process and findings.

General traditional medicine

There were 126 articles identified for this category with the majority of the publications being from 2009 and earlier (75%, n = 95). Thirty-three of the articles were based in Canada, one was based in both Canada and the US, and the remaining ninety-two were based in the US alone. The publication dates for articles spanned a wide time period between 1888 and 2020 (average year of publication was 1997), with the majority being commentary or qualitative in nature.

In the review of this category, it became clearly evident that the terms or conceptualizations applied to traditional medicine or its variants (i.e., traditional healing, Native American healing, etc.) were very generalized. Specifically, the general research topics ranged from trying to answer the question of what is traditional medicine [ 13 , 39 – 41 ], to asking questions on the efficacy and acceptance of traditional medicine [ 42 – 44 ], to the applicability of traditional medicine with specific disease states [ 45 – 47 ], in addition to stories of healing by recipients of traditional medicine practice or approaches [ 48 , 49 ].

According to Alvord and Van Pelt, traditional medicine is described in the Navajo culture as a medicine that is performed by a hataalii , which is someone who sees a person not simply as a body, but as a whole being with body, mind, and spirit seen to be connected to other people, to families, to communities, and even to the planet and universe [ 50 ]. In helping to clarify the intent and purpose for utilizing a traditional Indigenous medicine approach, Hill describes it as “the journey toward self-awareness, self-knowledge, spiritual attunement and oneness with Creation” and “the lifelong process of understanding one’s gifts from the Creator and the embodiment of life’s teaching that [an] individual has received” [ 13 ]. The traditional medicine practitioner’s role in the healing process has been described as their being an instrument, a helper, the worker, the preparer, the doer in the healing process with the work using the “medicines” being slow, careful, respectful, and embodying a sense of humility [ 51 ].

Also of note in this section of articles, was the subtle distinction between the terms ‘traditional healing’ compared to the actual using of ‘traditional medicines’. The core of ‘traditional healing’ was said to be or attaining spiritual ‘connectedness’, in which there were many stated ways for developing this in order to have a strong physical body and mind [ 52 ]. In essence, this ‘connectedness’ could be with or without the actual use of what we would call a ‘medicine’ in Western terms achieved instead through being in harmony with the natural environment, through fasting, prayer, or meditation, or through the use of actual ‘traditional medicines’ that could include plant- and herb-based medicines [ 52 ].

Quantitative data analysis within the general traditional medicine category of articles was rarely performed. When quantitative analysis was performed, it was usually done in a mixed method format that utilized survey tools alongside qualitative approaches (e.g., interviews, focus groups) [ 53 – 55 ]. For example, a mixed methods study by Mainguy et al., found that the level of spiritual transformation achieved through interaction with traditional healers was associated with a subsequent improvement in medical illness in 134 of 155 people ( P < .0001), and that this association exhibited a dose-response relationship [ 55 ]. In another mixed-methods study by Marsh et al., a 13-week intervention with “Indigenous Healing and Seeking Safety” in 17 participants demonstrated improvement in trauma symptoms, as measured by the TSC-40, with a mean decrease of 23.9 (SD = 6.4, p = 0.001) points, representing a 55% improvement from baseline [ 53 ]. Furthermore, in this study all six TSC-40 subscales demonstrated a significant decrease (i.e., anxiety, depression, sexual abuse trauma index, sleep disturbance, dissociation, and sexual problems) [ 53 ].

It was clear from the review of articles in this category that a large number of the articles were written from an observational or commentary perspective by non-Indigenous scholars (e.g., anthropologic perspectives) [ 42 , 56 ]. Those written more than twenty years ago often had titles or content that would not be considered culturally appropriate in today’s scholarly work. For example, an article by Walter Vanast from 1992 was titled, “‘Ignorant of any Rational Method’: European Assessments of Indigenous Healing Practices in the North American Arctic” [ 57 ]. Considerations for the issue of quality and accuracy in this body of literature will be addressed in the discussion section of this paper.

Integration of traditional and Western medicine systems

A total of 61 articles in this category were reviewed, with publication dates ranging from the year 1974 to the year 2019 (average year of publication was 2006). Sixteen percent (n = 10) of these articles were from nursing journals, and 39% (n = 24) were articles from mental health and/or substance abuse journals. Of the total number of articles in this section, 61% (n = 37) were based in the US, with the remaining being from Canada (n = 24).

Articles in this category fell into overlapping subsets within the overarching theme of the integration of traditional Indigenous medicine systems with Western medicine systems. There were articles specifically calling for physicians and other healthcare providers to better collaborate with traditional healers [ 58 , 59 ], and also calls for health “systems” to better coordinate and work with Indigenous medicine systems and associated practitioners [ 60 – 62 ]. Some of the articles focused on cultural accommodations, and awareness and attitudes in medical settings towards traditional medicine and healers [ 63 – 65 ]. Lastly, a number of articles reviewed existing medical environments, practitioners, and facilities that had either piloted or fully integrated traditional and Western medical care under the same roof or practice [ 24 , 66 – 69 ].

The integration of traditional medicine into existing medical education environments was showcased through a residency training program as described by Kessler et al. [ 70 ]. In 2011, the University of New Mexico Public Health department and their General Preventive Medicine Residency Program in the United States started to integrate traditional healing into the resident training curriculum with full implementation completed by 2015. An innovative approach was used in the teaching delivery by utilizing a compendium of training methods, which included learning directly from traditional healers and direct participation in healing practices by residents [ 70 ]. The “incorporation of this residency curriculum resulted in a means to produce physicians well trained in approaching patient care and population health with knowledge of culturally based health practices in order to facilitate healthy patients and communities” [ 70 ].

Other articles in this section described the role of nurses in advocating for Indigenous healing programs and treatment. In research by Hunter et al., healing holistically can be said to match the time-honored values seen in the nursing profession: caring, sharing, and empowering clients [ 71 ]. Participant observations demonstrated that health centers could support progression along a cultural path by providing traditional healing with transcultural nurses acting as lobbyists for culturally sensitive health programs directed by Indigenous peoples [ 71 ]. This need for advocacy and awareness building on traditional ways of healing were emphasized throughout this category of articles.

According to Joseph Gone, “Lakota doctoring [traditional healing] remains highly relevant for wellness interventions and healthcare services even though it is not amenable in principle to scientific evaluation” [ 72 ]. In reference to Indigenous healing practices in general, Gone states that in Indigenous settings “we already know what works in our communities” and this claim seems “to reflect the vaunted authority of personal experience within Indigenous knowledge systems [ 72 ].

Some scholars noted the potential harms of not moving towards a respectful dialogue between the two systems of medicine (i.e., Western and Indigenous). A noted article by David Baines, an Indigenous physician from the Tlingit/Tsimshian tribe in Southeast Alaska, describes one of his patients who had metastatic lung cancer [ 73 ]. The patient had an oncologist but also went to a traditional healer to help deal with the pain she was having [ 73 ]. When the patient told the oncologist she was seeing a traditional healer, the oncologist got angry and wanted to know why she wanted to see a “witch doctor” [ 73 ]. The patient was offended and angry and refused to go back to the oncologist. She ended up dying a very painful death. Dr. Baines noted that it is important to remember we have the same goal—a healthy patient [ 73 ].

Ceremonial practice for healing

Thirty articles were identified for this category. Important sub-categories became apparent in the review, including sweat lodge ceremonies (n = 15), traditional tobacco ceremonies and use (n = 6), birth and birthplace as a ceremony (n = 2), puberty ceremonies (n = 4), and using ceremony as a model for healing from a relative’s death or from trauma (n = 3). There were only eight Canadian studies published in this category, with the majority being based in the US (n = 22).

Sweat lodge ceremonies (SLC) have been practiced by many Indigenous nations since ancient times. SLCs are used as a process of honoring transformation and healing that is central to many Indigenous traditionalisms [ 74 ]. Gossage et al. examined the role of SLCs in the treatment for alcohol use disorder in incarcerated people [ 75 ]. The Dine Center for Substance Abuse Treatment staff utilized SLCs as a specific modality for jail-based treatment and analyzed its effect on a number of parameters. Experiential data was collected from 123 inmates after SLCs with several cultural variables showing improvement [ 75 ]. Gossage et al. also reported results from a similar prior study that analysed data for 100 inmates who participated in SLCs [ 75 ]. The research found that incarceration recidivism rates for those SLC participants was only 7% compared with an estimated 30–40% for other inmates who did not participate in such ceremonies [ 75 ]. Another study by Marsh et al., gathered qualitative evidence about the impact of the SLC on participants in a trauma and substance-abuse program and reported an increase in spiritual and emotional well-being that participants said was directly attributable to the ceremony [ 76 ].

Much of the existing literature on ceremonial tobacco focuses on either the perception of usage or the usage in general by Indigenous peoples in the region examined. In research done by Struthers and Hodge, six Ojibwe traditional healers and spiritual leaders described the sacred use of tobacco [ 77 ]. Interviews with these traditional healers confirmed that “sacred tobacco continues to play a paramount role in the community and provides a foundation for the American Indian Anishinabe or Ojibwe culture. They reiterated that using tobacco in the sacred way is vital for the Anishinabe culture [as] tobacco holds everything together and completes the circle. If tobacco is not used in a sacred manner, the circle is broken and a disconnect occurs in relation to the culture” [ 77 ].

The exploration of ceremonies surrounding birth and the relationship that is created through birth practices were outlined in a few studies reviewed for this category [ 78 , 79 ]. Ceremony was referred to in this context as the practice of what can be considered “rituals of healing”, noting that pregnancy itself “is carrying sacred water” [ 78 ]. As Rachel Olson points out, “[b]ringing people “back” to practicing ceremonial ways is seen as a healing process from the trauma encountered by First Nations peoples in Canada, as well as a way to both maintain our connection to the land and water, and to keep that same land and water safe for future generations. The implication in this is that by restoring our connection to the land through ceremony, other structural issues will again come into balance” [ 78 ].

Usage of traditional medicine

Data collection was completed in reservation and urban Indigenous communities to determine the usage rates of traditional medicine by Indigenous peoples. There was a total of 14 articles published on this topic, which included over 650 participants combined who completed surveys or interviews. Five studies were completed in Canada, and the remaining were completed in the United States (n = 9). Seventy-nine percent of the studies were published prior to 2009 (n = 11). The average year of publication was 2002 with publication dates ranging from 1988 to 2017. Rates of usage of both traditional medicines and traditional healers varied per region. Relevant findings are summarized in Table 1 .

Overall, the perception of traditional medicine amongst Indigenous people were positive. Several studies noted that access was an issue for many respondents who had the stated desire to use traditional medicine or see a traditional healer but did not know where to go for this support or treatment.

Traditional healer perspectives

The viewpoints of traditional healers themselves are an important contribution to this research topic. There were 18 studies that elicited the perspectives from Elders and traditional healers ranging in dates of publication between 1993 and 2019 (average year of publication was 2011). Twelve studies were either fully or partially based in the US, with nine articles published in either nursing or mental health related journals.

Moorehead et al. describe discussions held with a group of traditional healers on the possibilities and challenges of collaboration between Indigenous and conventional biomedical therapeutic approaches [ 93 ]. The participants recommended the implementation of cultural programming, the observance of mutuality and respect, the importance of clear and honest communication, and the need for awareness of cultural differences as a unique challenge that must be collaboratively overcome for collaboration [ 93 ].

It is not culturally acceptable to alter the words or provide an interpretation of the words of traditional healers. The following are some notable excerpts from traditional healer interviews that occurred in the literature reviewed:

The doctors and nurses at a local hospital asked me to speak to them on natural medicines . So I did . You could tell the doctors have a hard time trying to understand traditional healing and the use of plants to heal…it is hard for them to understand . Some of them got up and left when I started to talk about how you have to develop a relationship with the plant world…They sometimes have a hard time if things are not done their way…I respect the medicine , I just wish Western medical persons would understand [ 94 ] … When we gather medicine…the plant has a spirit in it…and…the spirit of those plants stays in the medicine…Every individual is different…every remedy is different…because specific things work for specific people…We’re made up of four parts…physical , mental , emotional , and spiritual . Sometimes sickness can be caused by imbalance within a person . When we do Indian healing…it goes to the source of the problem…not to the symptoms [ 94 ]. It’s a very powerful gift that we’ve been given…I am not a healer…I am only an instrument in that whole process . I am the helper and the worker , the preparer , and the doer . The healing ultimately comes from the Creator…With the lighting of that smudge , holding that eagle feather while we pray…these sacred medicines , these sacred pipes , and everything that we carry in our bundles . That’s where the strength comes from…from those medicines , from Mother Earth , and from the Creator … You are a part of creation , you’re a part of everything…there is this interrelatedness of all things , of all creation , and everything has life…we’re a whole family . And we’re related to all living things and all beings and all people [ 95 ]. I’ve been saying it for years . We need more medicine people . We need more Native healers…male and female [ 96 ].

It was apparent throughout the articles reviewed for this category that many traditional healers were not opposed to Western medicine; however, many had voiced concerns that Western medicine seemed to not respect them (i.e., didn’t respect their way of thinking or disregarded their knowledge base). Overall, a deep understanding and appreciation for the long-standing colonial injury felt in many Indigenous communities demonstrated through the cumulative effects of trauma ‘snowballing’ across generations [ 94 ] has become a platform for much of the traditional healers’ work in their home communities. To work with these present and historical harms, there was a clear advocacy among many of the traditional healers interviewed for ensuring the availability of therapeutic talk within cultural settings in addition to ceremonial participation to help facilitate healing and the revival of traditional spiritual beliefs [ 97 ].

This scoping review identified 249 articles that were predominately qualitative in nature, pertaining to traditional Indigenous medicine in the North American context. Although there was broad coverage of the topic area, it became apparent that many of the published articles were written from an ‘outsider’ perspective (i.e., observational research by scholars outside of the Indigenous communities themselves). With this, there was a slight shift noted in the type of research that was completed on traditional medicine around the 2000s. Prior to this date, it became apparent by the writing style used by many authors (i.e., they, them, etc.) that the articles were very much written “about” Indigenous people and their traditional medicine practice(s). Although post-2000 there was still quite a large volume of articles written by non-Indigenous scholars, there was an increasing presence of articles authored or co-authored by Indigenous people themselves [ 13 , 60 , 68 , 72 , 76 ]. The significance in this regard is notable as the presentation of Indigenous medicine by outside researchers often misses key cultural nuances, sometimes uses inappropriate or even insulting terminology, has a tendency to make assumptions that are not always correct (implicit bias), and presents an application or integrationist perspective that comes from what is often perceived to be a dominant Western knowledge system. As this type of ‘outsider’ scholarship serves as the foundational academic and clinical knowledge base for many of the current assumptions around traditional medicine, it was important to catalogue where some of the noted bias comes from.

Although it can be culturally inappropriate to assume there are pan-Indigenous ways of looking at traditional medicine and its practice (due to often stark differences in the practice of traditional medicine regionally), similar sentiments were expressed throughout many of the published articles. One was the assumed dominance of conventional medicine over traditional medicine practice, presented sometimes unconsciously through Western providers’ or researchers’ accounts of the subject and the language used. One possible consideration in this respect is that Indigenous-based interventions were often defined by a Western methodological approach and governance structure, which could be said to constrain and change the descriptions or programs themselves into something they were not actually meant to be. One solution to this issue would be to utilize an Indigenous methodological approach, governance structure, and reporting approach for these interventions, and then adapt the Western system to this approach and structure instead [ 58 ]. This would better ensure the centering of an Indigenous worldview and knowledge system through a truly self-determined Indigenous model with a potentially higher degree of success.

There is often a misperception that Indigenous peoples are in need of Westernized science in order to ‘legitimize’ our knowledge and healing systems [ 98 ]. It was clear from the literature reviewed on traditional healer perspectives that there was great opportunity for Western medicine and providers to learn about other ways of looking at health and disease in a form of respectful cooperation with Elders and Indigenous communities. This is consistent with the work of Berbman in 1973 who tells a story about a psychiatrist who brought some Navajo medicine men into his practice to demonstrate some of the things that he does in his practice [ 99 ] (i.e., the psychiatrist’s intent was to teach the medicine men). The psychiatrist demonstrated putting a Navajo woman under hypnosis for the medicine men.

One of the medicine men stated, “I’m not surprised to see something like this happen because we do things like this, but I am surprised that a white man should know anything so worthwhile… they [then] asked that my subject … diagnose something [while under hypnosis]. I objected, saying that neither she nor I knew how to do this and that it was too serious a matter to play with. They insisted that we try, however, and finally we decided that a weather prediction was not too dangerous to attempt. …When my subject was in a deep trance, I instructed her to visualize the weather for the next six months. She predicted light rain within the week, followed by a dry spell of several months and finally by a good rainy season in late summer. I make no claim other than the truthful reporting of facts: She was precisely correct” [ 99 ].

It was also evident through the articles reviewed that many Indigenous peoples using traditional medicine do not disclose this use to their Western healthcare providers. This reflects on the importance of developing culturally safe health systems and healthcare providers with strong communication skills for diverse patient settings. The story told by David Baines about the oncologist calling the patient’s traditional healer a “witch doctor” was a clear example of a lack of respect for utilizing a shared decision-making methodology for best outcomes in a clinical setting [ 73 ]. Implicit as well as overt bias against medical pluralism in diverse settings needs to be acknowledged and addressed in often authoritarian institutional settings [ 100 , 101 ] for best patient outcomes.

Overall, there has been a recent push with somewhat more acceptance in certain conventional medical settings towards supporting traditional Indigenous medicine interventions as demonstrated in some of the literature in this scoping review; however, the question remains whether or not “these efforts tend to represent political achievements more so than bona fide epistemological reconciliation” [ 72 ]. With continuing and significant health disparities existing in Indigenous populations in North America [ 102 ], a broader concerted effort needs to be mobilized and operationalized to ensure that Indigenous self-determined ways of knowing in relation to health and delivery of care is prioritized. Initial outcomes are promising in regard to traditional medicine’s benefit for Indigenous peoples in self-determined healthcare environments and settings. This has been clearly demonstrated by some of the literature reviewed here, yet, without more formalized support from all levels of the healthcare system, it will be difficult to expand these benefits and health outcomes to all Indigenous peoples who desire this type of care. This review and database ( S2 Table ) will hopefully serve as a repository for a portion of the academic literature contributing to practice, policy making, and research on this topic. This effort is aligned with Article 24 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP):

Indigenous peoples have the right to their traditional medicines and to maintain their health practices, including the conservation of their vital medicinal plants, animals, and minerals [ 1 ].

Limitations

This scoping review was an attempt to catalogue the literature in the area of traditional Indigenous medicine in the North American context. The use of defined categories may give the impression of distinct traditional medicine themes unrelated to each other; however, due to the wholistic nature of traditional medicine, there will always be substantial overlap between concepts given the interconnected nature of all aspects of Indigenous healing practices. Categorical themes were used to help create some organization of the large body of literature aiding with delineating future research needs as well as for the ease of pulling for programmatic and policy needs.

It is possible, due to the substantial overlapping terminology with other fields, that some articles may have been missed in the search strategy. With this, an effective search strategy in this field would require the searcher to be familiar with how Indigenous medicine terminology is commonly used and applied in academia to be able to correctly select and screen articles from a very large databases of mixed disciplines. Traditional medicine terminology can be complex and can be referenced using other languages or simply geographic location. Due to this, any published articles that used unique ways of referencing traditional medicine or were described using an Indigenous language term could have caused additional articles to be missed; however, due to saturation being reached in the methods review, we feel the literature was well represented in our database. Regardless, this comprehensive database ( S2 Table ) of the available literature should not be considered exhaustive of all available material on this topic.

From an Indigenous worldview, culture and cultural practices can be looked at and examined as being a form of medicine. Even traditional language can be considered a form of cultural medicine [ 103 ]. This review excluded studies to this effect due to the variation in interpretations that are possible in this area; however, this exclusion was not intended to degrade or minimize the importance of culture as a healing strategy in any way. Due to the need to capture one defined area of this topic on traditional medicine and healing as a first step, further research can now build upon this work by evolving the scholarship area to be inclusive of all facets of Indigenous healing.

Traditionally within Indigenous communities, knowledge on traditional healing or the medicines themselves was and is passed down through a strong oral tradition that often involves deep ceremonial practice. As knowledge transmission in the North American context most often does not include a written record, historical and present-day information on community practice in this area is rightfully held within Indigenous communities themselves. This form of knowledge needs to be recognized, honored, and respected in the context of the traditional protocols that the respective community follows under the guidance of their Elders. This knowledge is the true knowledge that is most often not reflected in written academic scholarship. Some Indigenous communities have become more engaged with research as you will have seen throughout this review; however, some choose not to engage in this form of knowledge transmission for a variety of important reasons. This review, although detailed, is therefore only a small snapshot of the vast knowledge that exists within Indigenous communities in North America.

A critical review of the retained full text articles was not completed as the intent was to provide a representative and complete database on this topic. In addition, the vast array of formats and methodologies used in the Indigenous traditional medicine literature make the dominant Western metrics of validity simply not applicable to the current research purpose. Because it is not culturally acceptable to critique traditional Indigenous medicine, an Indigenous methodology was honored. Using an inclusive framework for this topic, several articles that were not written by Indigenous peoples or communities were included, which in some cases portrayed gross stereotypes from ‘outside’ observations of traditional medicine practice(s). The reader is therefore advised to exercise caution when utilizing information from ‘outside’ observational and older studies that may not be reflective of actual and current Indigenous community perspectives on the topic discussed. To this end, we highly recommend prioritizing the respectful engagement of Indigenous scholars and/or their scholarship, community members, and local knowledge holders to better ensure the concepts and resources presented here will be grounded and relevant within any local or cultural context.

This scoping review identified 249 articles pertaining to traditional Indigenous medicine in the North American context with the following categorical themes being identified: General Traditional Medicine, Integration of Traditional and Western Medicine Systems, Ceremonial Practice for Healing, Usage of Traditional Medicine, and Traditional Healer Perspectives.

Although effort has been made to better accommodate Indigenous ways of knowing and healing into healthcare settings and delivery models, self-determined options for traditional Indigenous healing are still lacking in Western institutions. This scoping review underscores the crucial need to further examine the dynamics of healthcare relations in a post-colonial context, with more open spaces for dialogue surrounding the use of Indigenous traditional healing often desired in racially diverse medical settings. The prerequisite to move closer to transformative practice in this area involves prioritizing further research and communication on this topic with a focus on applied self-determined interventions and programming.

Supporting information

S1 checklist, acknowledgments.

A very heartfelt thank you to all of the Indigenous Elders and communities who have shared their stories and perspectives throughout this body of literature. Special thanks to Margo Greenwood, PhD, at the National Collaborating Center for Indigenous Health (NCCIH) for her helpful guidance on this project in addition to Daisy Goodman, CNM, DNP, MPH, for her ongoing support and helpful recommendations with the writing process. Thank you also to Devon Olson of Library Sciences at the University of North Dakota for aid in the search term development process.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability

Traditional Indigenous medicine in North America: A scoping review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Family & Community Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, North Dakota, United States of America.

- 2 Arctic Indigenous Wellness Foundation, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada.

- PMID: 32790714

- PMCID: PMC7425891

- DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237531

Background: Despite the documented continued use of traditional healing methods, modalities and its associated practitioners by Indigenous groups across North America, it is presumed that widespread knowledge is elusive amongst most Western trained health professionals and systems. This despite that the approximately 7.5 million Indigenous peoples who currently reside in Canada and the United States (US) are most often served by Western systems of medicine. A state of the literature is currently needed in this area to provide an accessible resource tool for medical practitioners, scholars, and communities to better understand Indigenous traditional medicine in the context of current clinical care delivery and future policy making.

Methods: A systematic search of multiple databases was performed utilizing an established scoping review framework. A consequent title and abstract review of articles published on traditional Indigenous medicine in the North American context was completed.

Findings: Of the 4,277 published studies identified, 249 met the inclusion criteria divided into the following five categorical themes: General traditional medicine, integration of traditional and Western medicine systems, ceremonial practice for healing, usage of traditional medicine, and traditional healer perspectives.

Conclusions: This scoping review was an attempt to catalogue the wide array of published research in the peer-reviewed and online grey literature on traditional Indigenous medicine in North America in order to provide an accessible database for medical practitioners, scholars, and communities to better inform practice, policymaking, and research in Indigenous communities.

Publication types

- Delivery of Health Care / methods

- Delivery of Health Care / organization & administration*

- Medicine, Traditional / methods*

- Medicine, Traditional / statistics & numerical data*

- North America

Grants and funding

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 09 November 2023

Coproducing health research with Indigenous peoples

- Chris Cunningham ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7083-9088 1 &

- Monica Mercury 2

Nature Medicine volume 29 , pages 2722–2730 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2078 Accesses

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health care

- Translational research

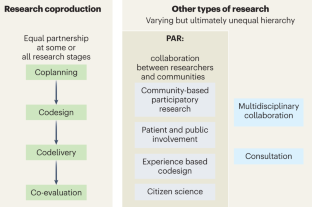

The coproduction of health research represents an important advance in the realm of participatory methodologies, which have evolved over the past five decades. This transition to a collaborative approach emphasizes shared control between academic researchers and their partners, fostering a more balanced influence on the research process. This shift not only enhances the quality of the research and the evidence generated, but also increases the likelihood of successful implementation. For Indigenous peoples, coproduced research represents a critical development, enabling a shift from being mere ‘subjects’ of research to being active controllers of the process—including addressing the extractive and oppressive practices of the past. In this Review, we explore how research coproduction with Indigenous peoples is evolving. An ‘Indigenous turn’ embraces the concept of shared control while also considering the principles of reciprocity, the incommensurability of Western and Indigenous knowledge systems, divergent ethical standards, strategic and political differences, and the broader impact of processes and outcomes. To illustrate these ideas, we present examples involving New Zealand’s Māori communities and offer recommendations for further progress.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Mapping the community: use of research evidence in policy and practice

Elizabeth N. Farley-Ripple, Kathryn Oliver & Annette Boaz

Participatory action research

Flora Cornish, Nancy Breton, … Darrin Hodgetts

Negotiating the ethical-political dimensions of research methods: a key competency in mixed methods, inter- and transdisciplinary, and co-production research

Simon West & Caroline Schill

Durose, C., Perry, B. & Richardson, L. Is co-production a ‘good’ concept? Three responses. Futures 142 , 102999 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

Laursen, S. et al. Collaboration across worldviews: managers and scientists on Hawai’i Island utilize knowledge coproduction to facilitate climate change adaptation. Environ. Manag. 62 , 619–630 (2018).

Farr, M. et al. Co-producing knowledge in health and social care research: reflections on the challenges and ways to enable more equal relationships. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8 , 105 (2021).

Cornish, F. et al. Participatory action research. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 3 , 34 (2023).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Masterson, D., Areskoug Josefsson, K., Robert, G., Nylander, E. & Kjellstrom, S. Mapping definitions of co-production and co-design in health and social care: a systematic scoping review providing lessons for the future. Health Expect. 25 , 902–913 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Halvorsrud, K. et al. Identifying evidence of effectiveness in the co-creation of research: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the international healthcare literature. J. Public Health 43 , 197–208 (2021).

Osborne, S. P., Radnor, Z. & Strokosch, K. Co-production and the co-creation of value in public services: a suitable case for treatment? Public Manag. Rev. 18 , 639–653 (2016).

Oliver, K., Kothari, A. & Mays, N. The dark side of coproduction: do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research? Health Res. Policy Syst. 17 , 33 (2019).

Ortiz-Prado, E. et al. Potential research ethics violations against an indigenous tribe in Ecuador: a mixed methods approach. BMC Med. Ethics 21 , 100 (2020).

McKenzie, D., Whiu, T. A., Matahaere-Atariki, D., Goldsmith, K. & Te Puni Kōkiri. Co-production in a Māori context. Soc. Policy J. N. Z. 33 , 32–46 (2008)

Latulippe, N. & Klenk, N. Making room and moving over: knowledge co-production, Indigenous knowledge sovereignty and the politics of global environmental change decision-making. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 42 , 7–14 (2020).

Yua, E., Raymond-Yakoubian, J., Daniel, R. A. & Behe, C. A framework for co-production of knowledge in the context of Arctic research. Ecol. Soc. 27 , 34 (2022).

Manuel-Navarrete, D., Buzinde, C. N. & Swanson, T. Fostering horizontal knowledge co-production with Indigenous people by leveraging researchers’ transdisciplinary intentions. Ecol. Soc. 26 , 22 (2021).

Haines, J., Du, J. T., Geursen, G., Gao, J., & Trevorrow, E. Understanding Elders’ knowledge creation to strengthen Indigenous ethical knowledge sharing. In Proc. RAILS - Research Applications, Information and Library Studies, 2016, School of Information Management, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, 6-8 December, 2016; http://InformationR.net/ir/22-4/rails/rails1607.html (2017).

Wilson, S. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods (Fernwood Publishing, 2008).

Google Scholar

Durie, M. Whaiora: Māori Health Development (Oxford Univ. Press, 1998).

Maher, P. A review of ‘traditional’ aboriginal health beliefs. Aust. J. Rural Health 7 , 229–236 (1999).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Martin, K. & Mirraboopa, B. Ways of knowing, being and doing: a theoretical framework and methods for indigenous and indigenist re‐search. J. Aust. Stud. 27 , 203–214 (2003).

Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A. & Kelly, K. Healing Models and Programmes in Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice (eds Dudgeon P, Milroy H and Walker R) Part 6, 417–532 (Commonwealth of Australia, 2014).

Chino, M. & Debruyn, L. Building true capacity: indigenous models for indigenous communities. Am. J. Public Health 96 , 596–599 (2006).

Napoli, M. Holistic health care for native women: an integrated model. Am. J. Public Health 92 , 1573–1575 (2002).

Pulotu-Endemann, F. K. Strategic Directions for the Mental Health Services for Pacific Islands People, 1–7 (Ministry of Health, 1995).

Richmond, C. A. M., Ross, N. A. & Bernier, J. in Moving Forward, Making a Difference (eds. White, J. P. et al.) 4 , 1–15 (Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International, 2007).

Hamalainen, S., Musial, F., Salamonsen, A., Graff, O. & Olsen, T. A. Sami yoik, Sami history, Sami health: a narrative review. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 77 , 1454784 (2018).

Smith, L. Thought space Wānanga—a Kaupapa Māori decolonizing approach to research translation. Genealogy 3 , 74 (2019).

Smith, L. T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (Zed Books, 2012).

Smith, G. H. The Development of Kaupapa Maori: Theory and Praxis . PhD thesis, Univ. Auckland (1997).

Smith, L. T. in Kaupapa Rangahau A Reader: A Collection of Readings from the Kaupapa Maori Research Workshop Series (eds. Pihama, L. & South, K.) 47–52 (Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2015).

Cunningham, C. A framework for addressing Maori knowledge in research, science and technology. Pac. Health Dialog. 7 , 62–69 (2000).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Greenaway, A. et al. Methodological sensitivities for co-producing knowledge through enduring trustful partnerships. Sustain. Sci. 17 , 433–447 (2021).

Waldegrave, C., Cunningham, C., Love, C. & Nguyen, G. Co-creating culturally nuanced measures of loneliness with Māori elders. Innov. Aging 4 , 610 (2020).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

King, P. T., Cormack, D., Edwards, R., Harris, R. & Paine, S. J. Co-design for indigenous and other children and young people from priority social groups: a systematic review. SSM Popul. Health 18 , 101077 (2022).

Rolleston, A. K., Korohina, E. & McDonald, M. Navigating the space between co-design and mahitahi: building bridges between knowledge systems on behalf of communities. Aust. J. Rural Health 30 , 830–835 (2022).

Ullrich, J. S., Demientieff, L. X. & Elliott, E. Storying and re-storying: co-creating indigenous well-being through relational knowledge exchange. Am. Rev. Can. Stud. 52 , 247–259 (2022).

Minoi, J.-L. et al. A participatory co‑creation model to drive community engagement in rural Indigenous schools: a case study in Sarawak. Electron. J. e-Learn. 17 , 157–167 (2019).

Zurba, M. et al. Learning from knowledge co-production research and practice in the twenty-first century: global lessons and what they mean for collaborative research in Nunatsiavut. Sustain. Sci. 17 , 449–467 (2021).

Koster, R., Baccar, K. & Lemelin, R. H. Moving from research ON, to research WITH and FOR Indigenous communities: a critical reflection on community-based participatory research. Can. Geogr. 56 , 195–210 (2012).

Peters, D. et al. Participation is not enough. In Proc. 30th Australian Conference on Computer–Human Interaction (eds Buchanan, G. & Stevenson, D.) 97–101 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2018).

Bryant, J. et al. Beyond deficit: ‘strengths-based approaches’ in Indigenous health research. Sociol. Health Illn. 43 , 1405–1421 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Goodyear-Smith, F. & Ashton, T. New Zealand health system: universalism struggles with persisting inequities. Lancet 394 , 432–442 (2019).

Maclean, K. et al. Decolonising knowledge co-production: examining the role of positionality and partnerships to support Indigenous-led bush product enterprises in northern Australia. Sustain. Sci. 17 , 333–350 (2021).

Johnson, J. T. & Murton, B. Re/placing native science: indigenous voices in contemporary constructions of nature. Geogr. Res. 45 , 121–129 (2007).

Morton Ninomiya, M. E. et al. Knowledge translation approaches and practices in Indigenous health research: a systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 301 , 114898 (2022).

Martel, R., Shepherd, M. & Goodyear-Smith, F. He awa whiria—a ‘braided river’: an Indigenous Māori approach to mixed methods research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 16 , 17–33 (2022).

Pitama, S. et al. Meihana model: a clinical assessment framework. N.Z. J. Psychol. 36 , 118–125 (2007).

Wright, A. L., Gabel, C., Ballantyne, M., Jack, S. M. & Wahoush, O. Using two-eyed seeing in research with Indigenous people: an integrative review. Int. J. Qual. Methods 18 , 160940691986969 (2019).

Bandola-Gill, J., Arthur, M. & Leng, R. I. What is co-production? Conceptualising and understanding co-production of knowledge and policy across different theoretical perspectives. Evid. Policy 19 , 275–298 (2023).

Pain, R. et al. Mapping Alternative Impact—Alternative Approaches to Impact from Co-produced Research . Project report (Durham Univ., 2015).

Carroll, S. R. et al. The CARE principles for Indigenous data governance. Data Sci. J. 19 , 1–12 (2020).

Baum, F., MacDougall, C. & Smith, D. Participatory action research. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 60 , 854–857 (2006).

Kemmis, S. & McTaggart, R. in The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (eds. Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y.) 559–604 (Sage, 2005).

Siffels, L. E., Sharon, T. & Hoffman, A. S. The participatory turn in health and medicine: the rise of the civic and the need to ‘give back’ in data-intensive medical research. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8 , 306 (2021).

Israel, B., Eng, E., Schultz, A. & Parker, E. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research (Jossey-Bass, 2005).

Williams, O., Robert, G., Martin, G. P., Hanna, E. & O’Hara, J. in Decentring Health and Care Networks (eds. Bevir, M. & Waring, J.) 213–237 (Springer, 2020).

Liabo, K., Boddy, K., Burchmore, H., Cockcroft, E. & Britten, N. Clarifying the roles of patients in research. Br. Med. J. 361 , k1463 (2018).

Tanay, M. A. L. et al. Co-designing a cancer care intervention: reflections of participants and a doctoral researcher on roles and contributions. Res. Involv. Engagem. 8 , 36 (2022).

Craig, E. et al. in Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health (ed. Liamputtong, P.) 1–15 (Springer, 2023).

Cohn, J. P. Citizen science: can volunteers do real research? BioScience 58 , 192–197 (2008).

Dickinson, J. L., Zuckerberg, B. & Bonter, D. N. Citizen science as an ecological research tool: challenges and benefits. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 41 , 149–172 (2010).

Morales, M. P. E. Participatory action research (PAR) cum action research (AR) in teacher professional development: a literature review. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2 , 156–165 (2016).

Méndez, V., Caswell, M., Gliessman, S. & Cohen, R. Integrating agroecology and participatory action research (PAR): lessons from Central America. Sustainability 9 , 705 (2017).

Rodriguez, L. F. & Brown, T. M. From voice to agency: guiding principles for participatory action research with youth. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2009 , 19–34 (2009).

Gatenby, B. & Humphries, M. Feminist participatory action research: methodological and ethical issues. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 23 , 89–105 (2000).

Fine, M. & Torre, M. E. Critical participatory action research: a feminist project for validity and solidarity. Psychol. Women Q. 43 , 433–444 (2019).

Reid, C., Tom, A. & Frisby, W. Finding the ‘action’ in feminist participatory action research. Action Res. 4 , 315–332 (2016).

Dadich, A., Moore, L. & Eapen, V. What does it mean to conduct participatory research with Indigenous peoples? A lexical review. BMC Public Health 19 , 1388 (2019).

Dudgeon, P., Bray, A., Darlaston-Jones, D. & Walker, R. Aboriginal Participatory Action Research: An Indigenous Research Methodology Strengthening Decolonisation and Social and Emotional Wellbeing—Discussion Document (Lowitja Institute, 2020).

Peltier, C. An application of two-eyed seeing: Indigenous research methods with participatory action research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 17 , 160940691881234 (2018).

Datta, R. et al. Participatory action research and researcher’s responsibilities: an experience with an Indigenous community. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 18 , 581–599 (2014).

Aika, L. & Greenwood, J. in Education, Participatory Action Research, and Social Change: International Perspectives (eds. Kapoor, D. & Jordan, S.) 59–72 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

Smylie, J. et al. Knowledge translation and indigenous knowledge. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 63 , 139–143 (2004).

Agrawai, A. Dismantling the divide between Indigenous and scientific knowledge. Dev. Change 23 , 413–439 (1995).

Durie, M. Understanding health and illness: research at the interface between science and Indigenous knowledge. Int. J. Epidemiol. 33 , 1138–1143 (2004).

Ermine, W. J. The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law J. 6 , 193–203 (2007).

Ellison, C. Indigenous Knowledge and Knowledge Synthesis Translation and Exchange (KSTE) (National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health, 2014).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding support from the Ageing Well National Science Challenge for the Tai Kaumātuatanga Older Māori Wellbeing and Participation: Present and Future Focus (1903R) project and team members C. Love and C. T. Waldegrave.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Research Centre for Hauora & Health (RCHH), Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand

Chris Cunningham

The Family Centre Social Policy Research Unit, Lower Hutt, New Zealand

Monica Mercury

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Positionality statement. Both authors identify as Māori, the Indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand. C.C. is a member of the Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Toa, Te Ātiawa and Te Ātihaunui-a-Pāparangi iwi (tribes) and also claims Anglo-European ancestry. A scientist by training, he holds a PhD in chemistry (1988) and has worked as a Māori health researcher since 1996 and as a professor since 2001. He is a director of a Treaty of Waitangi-led research center in a New Zealand university. M.M. identifies as Te Iwi Mōrehu, Ngāti Kahungunu ki Te Wairarapa and ki Te Wairoa through her Māori father and is of Chinese descent through her mother. She is a trained educator (MEd) and community-based health researcher working in the nongovernmental sector.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Chris Cunningham .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Medicine thanks Jeneile Luebke, Jacquie Kidd and Malcolm King for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Karen O’Leary, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Cunningham, C., Mercury, M. Coproducing health research with Indigenous peoples. Nat Med 29 , 2722–2730 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02588-x

Download citation

Received : 11 June 2023

Accepted : 13 September 2023

Published : 09 November 2023

Issue Date : November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02588-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Translational Research newsletter — top stories in biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma.

- Open access

- Published: 14 December 2015

Integrating traditional indigenous medicine and western biomedicine into health systems: a review of Nicaraguan health policies and miskitu health services

- Heather Carrie 1 , 2 ,

- Tim K. Mackey 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Sloane N. Laird 6

International Journal for Equity in Health volume 14 , Article number: 129 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

21 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

An Erratum to this article was published on 03 February 2016

Throughout the world, indigenous peoples have advocated for the right to retain their cultural beliefs and traditional medicine practices. In 2007, the more than 370 million people representing 5000 distinct groups throughout the world received global recognition with the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). UNDRIP Article 24 affirms the rights of indigenous peoples to their traditional medicines and health practices, and to all social and health services. Although not a legally binding agreement, UNDRIP encourages nation states to comply and implement measures to support and uphold its provisions. Within the context of indigenous health and human rights, Nicaragua serves as a unique case study for examining implementation of UNDRIP Article 24 provisions due to the changes in the Nicaraguan Constitution that strive for the overarching goal of affirming an equal right to health for all Nicaraguans and supporting the integration of traditional medicine and biomedicine at a national and regional level. To explore this subject further, we conducted a review of the policy impact of UNDRIP on health services accessible to the Miskitu indigenous peoples of the North Atlantic Autonomous Region (RAAN). We found that although measures to create therapeutic cooperation are woven into Nicaraguan health plans at the national and regional level, in practice, the delivery of integrated health services has been implemented with varying results. Our review suggests that the method of policy implementation and efforts to foster intercultural collaborative approaches involving respectful community engagement are important factors when attempting to assess the effectiveness of UNDRIP implementation into national health policy and promoting traditional medicine access. In response, more study and close monitoring of legislation that acts to implement or align with UNDRIP Article 24 is necessary to ensure adequate promotion and access to traditional medicines and health services for indigenous populations in Nicaragua and beyond.

Introduction