An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Social Media Addiction, Self-Compassion, and Psychological Well-Being: A Structural Equation Model

Eirini marina mitropoulou, marianna karagianni, christoforos thomadakis.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author:Eirini Marina Mitropoulou✉ [email protected]

Cite this article as: Mitropoulou EM, Karagianni M, Thomadakis C. Social media addiction, self-compassion, and psychological well-being: A structural equation model. Alpha Psychiatry. 2022; 23(6) :298-304.

Received 2022 May 26; Accepted 2022 Sep 26; Collection date 2022 Nov.

Research indicates that social media addiction is associated with several psychological consequences, for example, depression. Distressed individuals tend to devote more time to social media, which leads to impairment of daily life. Interestingly, individuals feeling more compassionate toward them tend to devote less time to social media and feel less psychologically distressed. This research aimed to examine the association between social media addiction and self-compassion and whether it can be further explained through the association of psychological distress.

A sample of 255 Greek adults received a personal invitation sent to various social media platforms. Invitations included a link, which redirected participants to the information sheet and the study questionnaires, namely the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale, the Self-Compassion Scale, and the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale. Participation was voluntary and no benefit/reward was granted.

As predicted, social media addiction was found to negatively correlate with self-compassion and positively with distress. We used structural equation modeling to examine associations between variables, with psychological distress acting as a mediator. Examination of estimated parameters in the model revealed statistically significant correlations, except for the positive dimensions of the Self-Compassion Scale, which were found to be insignificantly associated.

Conclusion:

Individuals with higher levels of self-compassion tend to report less social media additive behaviors and distress. The extensive use of social media is related to negative feelings and emotions. Self-compassion is a potential protective factor, while distress is a potential risk factor for social media addiction. Intervention programs dealing with social media addiction should consider the role of self-compassion.

Keywords: Social media addiction, self-compassion, depression, anxiety, stress, factor analysis

Main Points

Self-compassionate individuals exhibit social media additive behaviors to a lesser degree than non-self-compassionate individuals.

Only the negative facets of self-compassion (i.e., self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification) actually influence social media addiction, as opposed to the positive ones (i.e., mindfulness, self-kindness, and common humanity), which exhibited nonsignificant relations.

Psychological distress, namely depression, anxiety, and stress, is significantly associated with social media addiction.

Psychological distress is a significant risk factor (mediator) for exhibiting social media addiction.

Introduction

The use of the social media (SM) has increased considerably in the recent years; more than 1 billion individuals worldwide use one or more of these services on a regular basis. 1 Social media applications are virtual communities where users can create their personal profile and make it publicly available, interact with real-life friends, and meet new people, based on shared interests. Despite the benefits of SM to everyday life (e.g., social interaction, marketing enhancement, and information processing), problematic use of SM, referred as SM addiction, has also been documented. 2 According to Andreassen and Pallesen, 3 SM addiction is defined as a psychological dependence on SM use and portrays strong and uncontrollable intrinsic motivation, which leads individuals to devote significant amount of time and effort to SM. This disposition impairs important areas of their daily life, like social activities, academic and/or professional commitments, interpersonal relationships, and psychological health. Although SM addiction has not yet been endorsed as a clinical disorder, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), has included internet gaming disorder as an emerging issue for further research. 4 Social media addiction has been linked to behaviors akin to other similar addictive disorders, due to the excessive and additive use of SM apps. 2 To our knowledge, SM addiction remains an unexplored public health issue among Greek adults.

Social Media Addiction as a Significant Psychological Health Issue Worldwide

Social media addiction among adolescents and adults is reported with variations in several countries. Robust epidemiological studies, using nationally representative large-scale samples, reported variations in the prevalence rates of SM intense use in the general population. For example, prevalence rate around 4.5% has been reported among 5961 Hungarians. 5 In Germany, 4.1% of males and 3.6% of female adolescents have been demonstrating SM addiction. 6 De Cock et al 7 reported that 2.9% of the Belgium population is classified as SM addicted. To a similar extent, 11.9% of the 23 532 Norwegian population, aged 18-88 years old, were found to report SM addiction. 3 Moreover, studies that used non-probability sampling techniques have reported even higher prevalence rates of SM addiction among specific age groups. For example, the prevalence rates among 2198 Dutch adolescents aged 10-17 years old are approximately 7%. 8 These rates increase by 18% among young Facebook (n = 667) and YouTube (n = 1056) Malaysian users, under the age of 25 9 and by 29.5% among 1110 students aged 18-25 years old, attending a major university in Singapore. 10

Social media addiction has been found to be associated with a range of negative health outcomes among adolescents. In their systematic review, Seabrook et al 11 found a significant association between the quality of SM interaction and mental health. Particularly, individuals who exhibit excessive use of SM tend also to exhibit symptoms of depression, display problematic interaction patterns, feel more vulnerable to peer victimization, and express feelings of disengagement from daily life. All these behaviors are considered a potential risk factor for suicidal desire. Research has also associated SM addiction with disturbances in sleep behaviors, which lead to bedtime and rising time postponements, 12 increased feelings of social distancing, loneliness and anxiety, 13 deterioration of well-being, and social interaction overload, namely the individual’s engagement in social exchange beyond his/her communicative and cooperative capabilities. 14 Identifying factors associated with SM app interaction is highly warranted as guideline for the design of interventions to reduce SM addiction among adolescents and adults.

Self-compassion and Social Media Addiction

The concept of self-compassion has drawn interest, due to its strong link to psychological well-being. 6 Self-compassion pertains to the understanding, acknowledgment, and transformation of personal suffering through self-kindness, self-acceptance, and mindfulness. The concept of self-compassion is identified by 3 interactive components, all having 2 opposite facets. The first facet includes the dimensions of self-judgment and self-kindness, which refer to one’s ability to be caring and understanding toward the self rather than being harsh and self-critical under negative circumstances. Self-compassionate individuals embrace difficult situations, while self-judgmental individuals become easily upset with themselves. The second facet pertains to common humanity and isolation. Individuals exhibiting feelings of isolation tend to be more prone to social distancing and to personal failure inefficiency. The third facet includes the dimensions of mindfulness and over-identification, which pertain to the awareness and acceptance of one’s painful and stressful experiences in a balanced way. Individuals exhibiting mindfulness pay attention to the present moment and accept their thoughts, feelings, and senses. 15

Self-compassion is reported to enhance emotional well-being, 16 reduce feelings of shame-proneness, 17 increase motivation toward personal growth, mitigate health-related problematic behaviors, such as smoking, 15 and reduce feelings of depression and anxiety. 18 , 19 Self-compassion is also reported to have a regulative causal effect on negative feelings and behaviors; individuals, who embrace life and avoid maladaptive beliefs or negative cognitions are less prone to psychological distressful feelings and behaviors. 20

Self-compassion is also associated with SM app usage. 20 Individuals exhibiting higher levels of self-compassion spend less time on social networking, log in to various SM platforms less frequently, report fewer symptoms of intensity, and generally are more positively inclined to online networking interactions. Research has examined the moderating effect of self-compassion on SM addiction, mostly focusing on the effect it pertains to negative body image perceptions, 21 perfectionistic self-presentations, 22 or specific distressful symptoms, such as depression. 20 Social media app users, who exhibit higher levels of self-compassion, tend to report less symptoms of depression than those with lower levels of self-compassion, thus confirming the mediating effect of the latter on SM addiction and psychological distress.

Psychological Distress and Social Media Addiction

The literature reports that social networking has an effect on psychological distress of the users and can become additive. 2 , 23 Psychological distress is identified by 3 components, namely depression, anxiety, and stress. 24 Depression is associated with feelings of hopelessness, self-deprecation, anhedonia, and lack of interest. Anxiety pertains to the autonomic arousal, and the subjective experience of anxious affect and stress is the persistent feeling of tension and/or the excessive worrying in general life situations. Psychological distress is considered an important risk factor to SM addiction. Preliminary research has associated higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress with Facebook and Instagram excessive use 18 , 25 ; SM-addicted users exhibit withdrawal, poor planning abilities, tolerance to SM app use, preoccupation, impairment of control, and excessive online time.

Psychological distress is reported to have an indirect causal effect on negative feelings and behaviors 18 ; individuals, who feel abandoned, hopeless, and dissatisfied by their lives are more prone to excessive SM exposure.

Research Objective Overview

The present study extends previous research 18 , 20 by exploring the relation between SM addiction and self-compassion to a non-clinical sample of Greek adults. Moreover, we examine whether psychological distress (including all 3 facets, namely depression, anxiety, and stress) moderates the relationship between SM addiction and self-compassion. We therefore hypothesize the following:

Social media addiction will be negatively related to self-compassion.

Psychological distress will be positively related to SM addiction and negatively related to self-compassion.

Psychological distress will moderate the relationship between SM addiction and self-compassion, with stronger association being found by individuals that exhibit lower levels of self-compassion.

Additionally, our research further aims to gather information about the SM habits of Greek adults with regard to SM app usage, which may be considered as directives for healthy SM daily use and assist the design of effective intervention programs for SM addictive behaviors in the future.

Participants

Two hundred fifty-five (n = 255) participants were recruited via snowball sampling procedure. The research was conducted in Greece, and data collection took place between April and May of 2022. Individuals needed to fulfill the study’s inclusion criteria prior to participation. The inclusion criteria were the following: participants should be over 18 years old and should have an active profile account on at least 1 SM app (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, Viber, and Pinterest). Individuals who were under 18 years old and/or did not have an active SM account on any SM platform were excluded from participation. Research participants reported a mean age of 27 years (SD = 8.93), ranging between 18 and 60 years; 176 (69%) were females and approximately half of the participants were university students. Missing values were found only in certain demographics (namely age, education, and occupational status). These missing values do not exceed the 2% of the research sample and are not used in any stage of analysis conducted in this study.

Participants responded to a personal invitation posted on various SM platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram), asking them to participate in a study about the impact of SM use, self-compassion, and psychological well-being. Participants were recruited on a volunteer basis through several, different SM online posts, referring to the survey link, posted by the researchers. Participants were also enhanced to invite their friends (sharing similar characteristics) to take part in the research, by sharing the online survey link via their SM profile. The link directed all individuals to the information sheet, which contained research information, along with the first author’s contact details. Prior to participation, individuals provided informed consent for participation; after consent, participants were redirected to the research questionnaires. The survey took approximately 10 minutes for completion. Participation was voluntary, and no benefits or rewards were offered for participating. Participants were also asked to provide demographic information (gender, age, education, and occupation status) and habits of SM use and specifically in which SM they have an active account/profile. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Crete (protocol no. 117/2022).

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale

The Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) contains 6 self-report items reflecting core addiction elements (i.e., salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse). 3 Each item is answered with regard to SM experience within a time frame of 12 months and is answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very rarely) to 5 (very often). A score of ≥3 is an indication of SM tendency to addiction. Sample item is “How often during the last year have you used SM so much that it has a negative impact on your job/studies?" The original BSMAS is provided in English, and hence adaptation to Greek was required; adaptation was based on the committee translation process. 26 Three bilingual experts translated the original measure into Greek, with the translations subsequently reevaluated by 1 additional expert, who acted as a verifier. Internal consistency of scale was ω = 0.83. Confirmatory factor analysis showed excellent fit to the data [ χ 2 (9, n = 255) = 20.0, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.98, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.96, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.07, standardized root mean residual (SRMR) = 0.03]. The adapted measure is provided in Appendix 1.

The Self-Compassion Scale

The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) assesses a person’s feelings of compassion for oneself during times of distress and disappointment. 27 The SCS consists of 26 items and utilizes a 5-point Likert-type scale, with responses ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Sample items include “I’m tolerant of my own flaws and inadequacies" (i.e., self-kindness) and “When something upsets me, I try to keep my emotions in balance" (i.e., mindfulness). The items included in each subscale, along with reported internal consistency indices, are as follows: self-kindness (5 items; α = 0.70), self-judgment (5 items; α = 0.77), common humanity (4 items; α = 0.72), isolation (4 items; α = 0.71), mindfulness (4 items; α = 0.72), and over-identification (4 items; α = 0.76). The SCS has been adopted to Greek by Mantzios et al. 28 and its reported internal consistency reliability was α = 0.87.

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) contains 3 self-report scales designed to measure how frequently individuals experience symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress during the last week. 24 The DASS-21 consists of 21 items, with each subscale having 7 items; responses use a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time). Sample items include “I tended to over-reach to situations" (stress) and “I felt that life was meaningless" (depression). The DASS-21 has been adopted to Greek by Lyrakos et al. 29 and the scale’s overall internal consistency reliability was Cronbach’s α = 0.79.

Data analysis was conducted using Jamovi Statistical Computer Software version 2.2 (The Jamovi project; Sydney, Australia). Descriptive statistics and non-zero correlations among all variables were examined. Data normality was evaluated with the Shapiro–Wilk normality test; significance values > .05 indicate normally distributed data. 30 Confirmatory factor analysis was initially conducted to examine the adequacy of the measurement for all constructs under investigation. Structural equation modeling was then performed to examine the fit of the hypothesized structural model. 31 To examine the mediation effect of psychological distress on self-compassion and SΜ addiction, a bootstrap procedure was used to test the indirect effect 32 using a bias-corrected confidence interval of 2000 resamples. To evaluate the proposed model, the method of the diagonal weighted least squares estimator was used, which is considered to outperform other relevant estimators (e.g., maximum likelihood estimator) and is considered fairly accurate with small size samples, non-normality, and few model parameters. 33

To assess model adequacy, several goodness-of-fit indices have been assessed and reported in combination, such as the χ 2 fit index, the CFI, the TLI, the RMSEA, and the SRMR. 34 A nonsignificant P -value indicates good fit for the χ 2 fit index. 34 However, chi-square is sensitive to sample size (with smaller samples indicating statistically significant outputs); thus, the calculation of the chi-square index to the respective degrees of freedom ( χ 2 /df) is preferred, with a ratio of ≤2 indicating good fit. In addition, CFI and TLI range between 0 and 1, with values >0.90 indicating adequate fit. A value below 0.05 in RMSEA and SRMR indicates an excellent fit, with values ranging from 0.05 to 0.08 indicating a reasonable fit. 33 , 35

In terms of SM use, 12 (4.7%) participants reported that they spend ≥5 hours on SM apps online per day and 186 (73.1%) use more than 5 different SM platforms daily (see Table 1 ). The most frequently reported SM platforms are the Facebook/Messenger and the Instagram (98.0% and 88.2% respectively), followed by the Viber (78.0%), the YouTube (67.5%), and the Pinterest (36.9%). Frequencies and percentages of age, educational level, occupational status, and the number of SM platforms use are presented in Table 1 . Due to the snowball sampling procedure used for data collection, participants are unequally distributed in accordance to their age group and their educational level.

Frequency Table for Demographic and Social Media Habits

Focusing further on the SM addiction among Greek adults, the assessed mean level of the BSMAS in our sample was estimated and perceived as relatively low ( M = 10.2, SD = 4.21, range: 6-25). Although the Greek version of the BSMAS has not yet been examined for having critical cutoff scores on SM addiction, we employed the critical cutoff scores suggested by Andreassen et al 12 These cutoff scores were reached by a relatively low percentage of the Greek sample (polythetic scoring: 2%; monothetic scoring: 16.1%), which indicates low levels of SM addiction.

Table 2 presents the correlations between all variables included in the study. Results revealed a negative correlation between SM addiction and self-compassion. Findings also revealed a positive association between psychological distress and SM addiction and a negative relation between psychological distress and self-compassion, thus confirming our first and second research hypothesis.

Correlations Between Variables Included in the Study

n = 255; BSMAS, Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale; DASS-21, Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale; SCS, Self-Compassion Scale.

* P < .05, ** P < .01, *** P < .001.

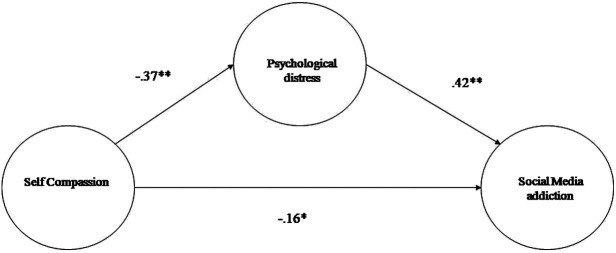

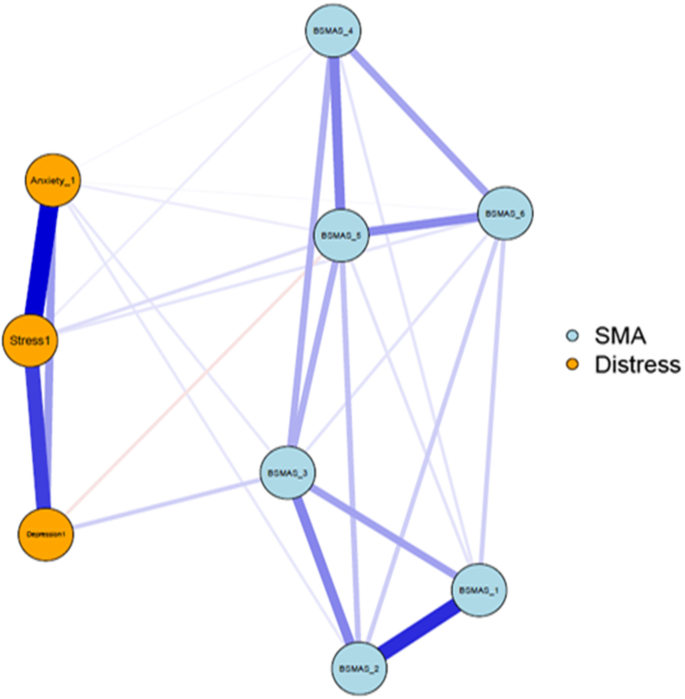

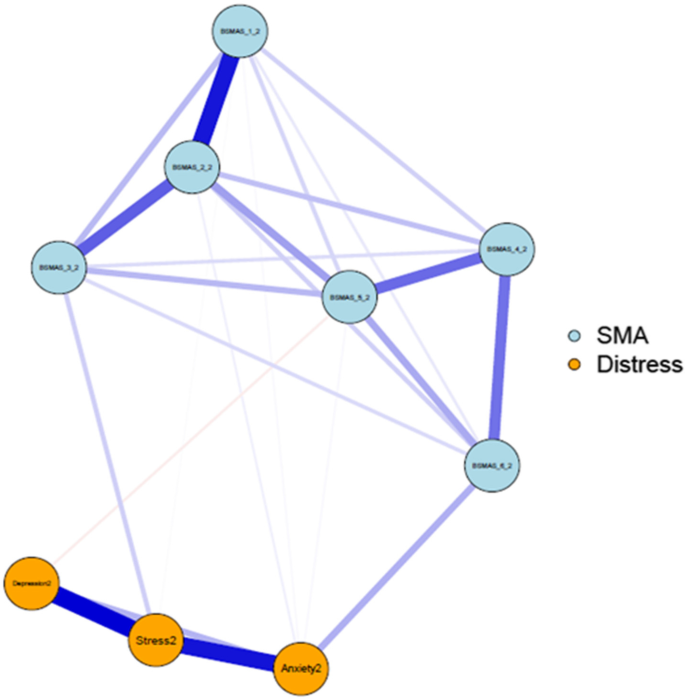

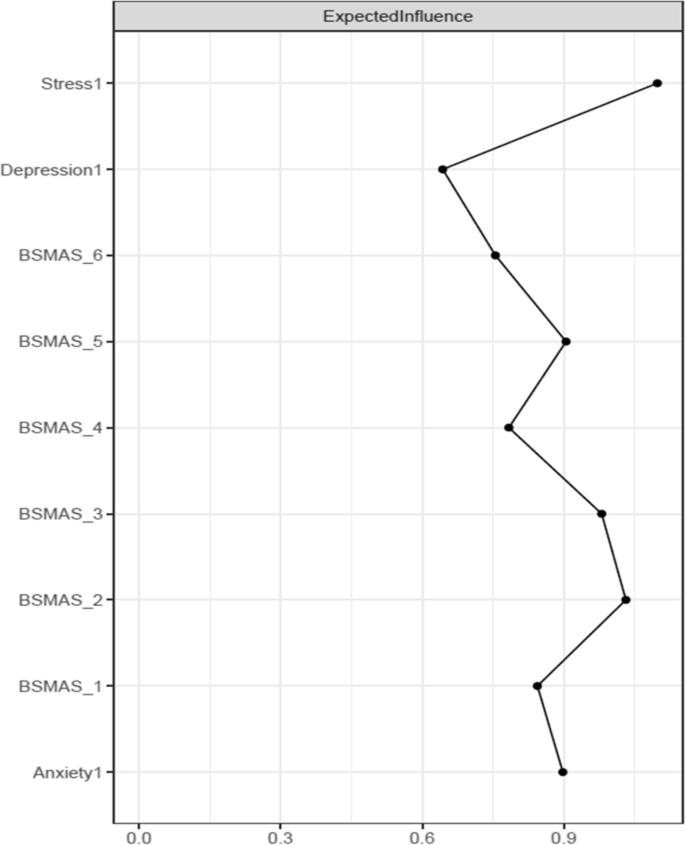

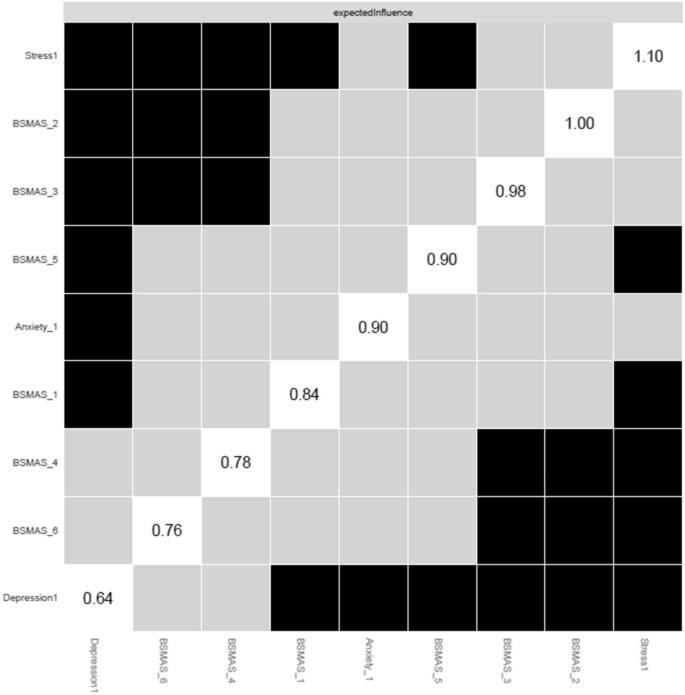

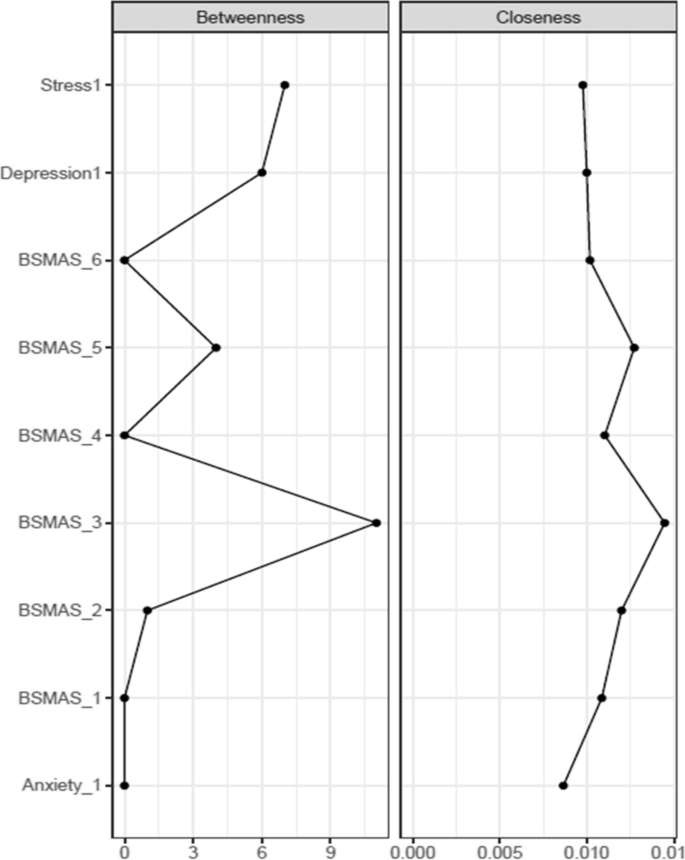

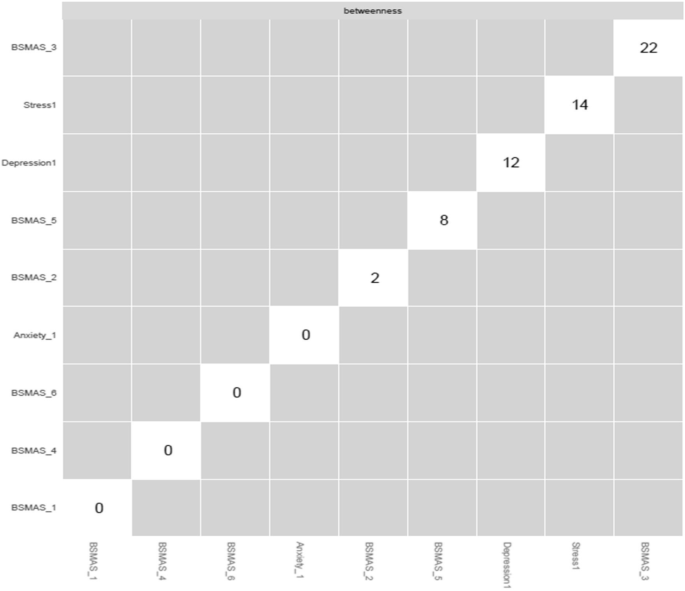

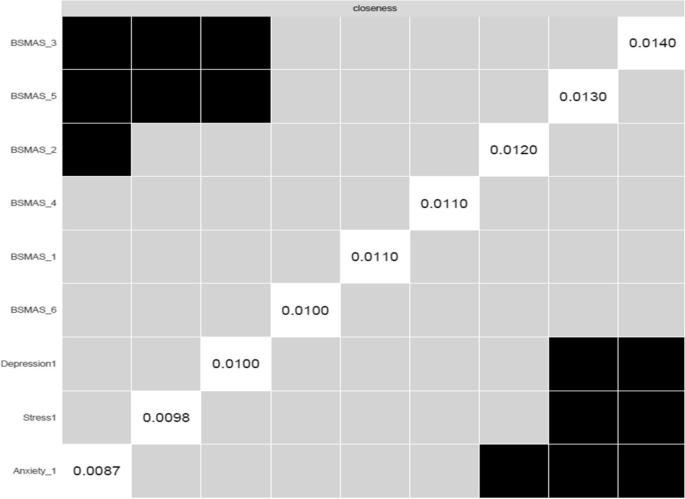

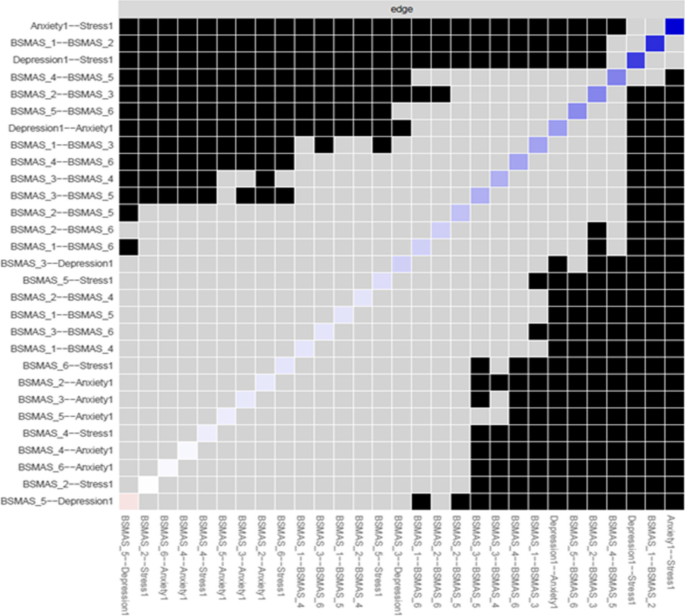

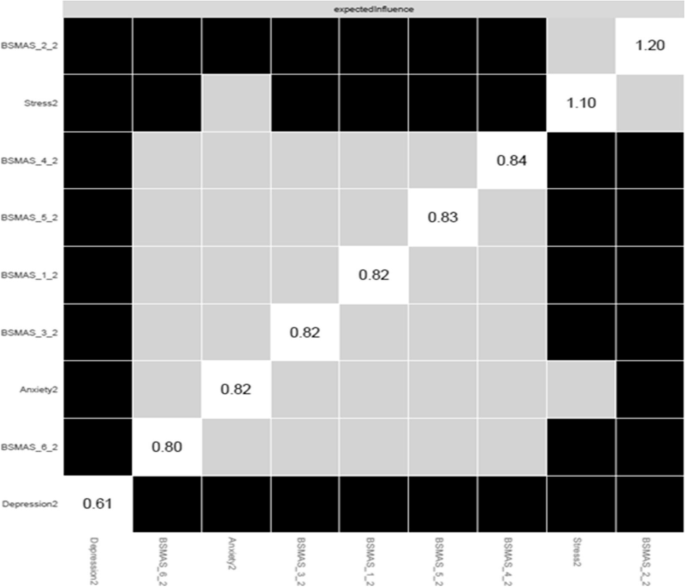

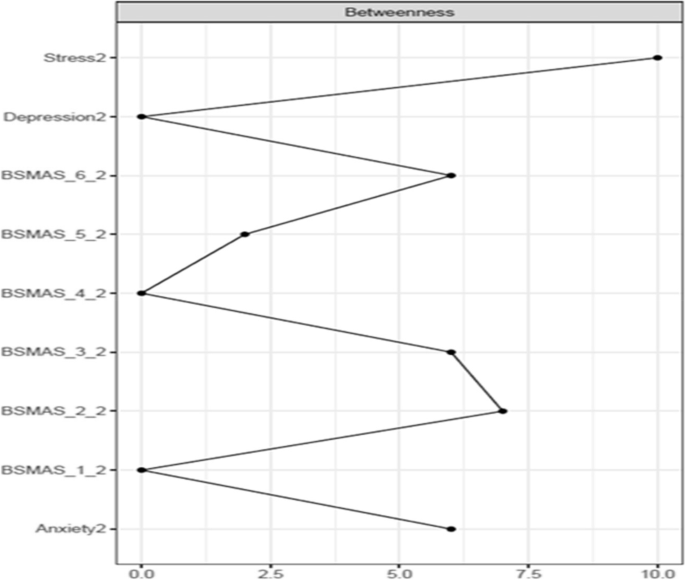

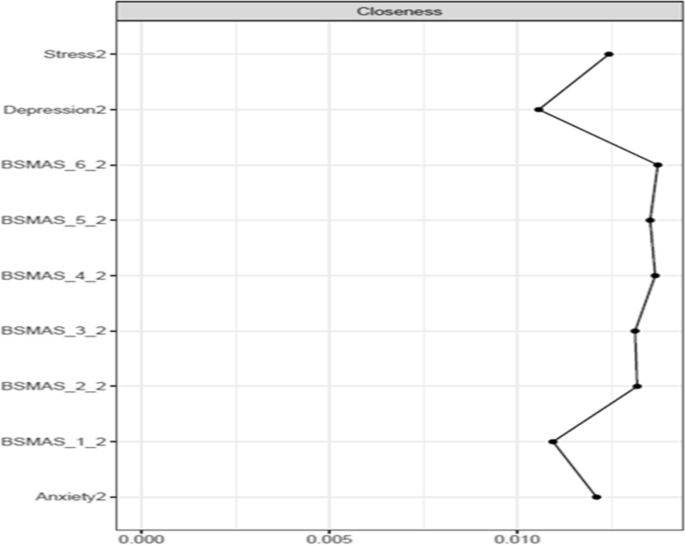

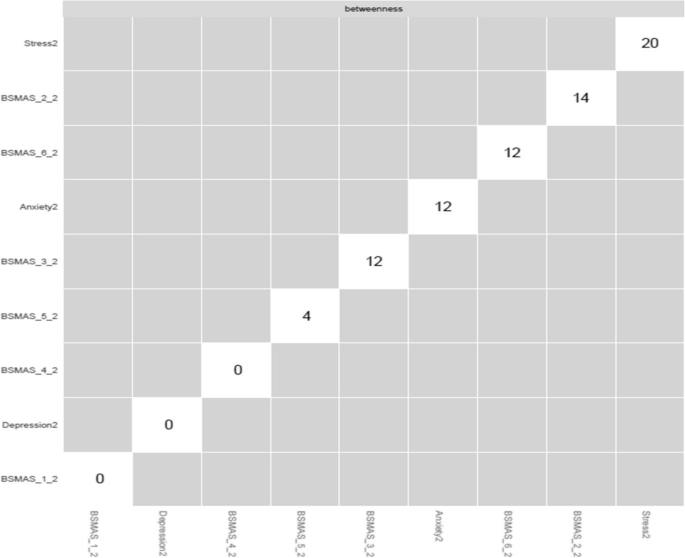

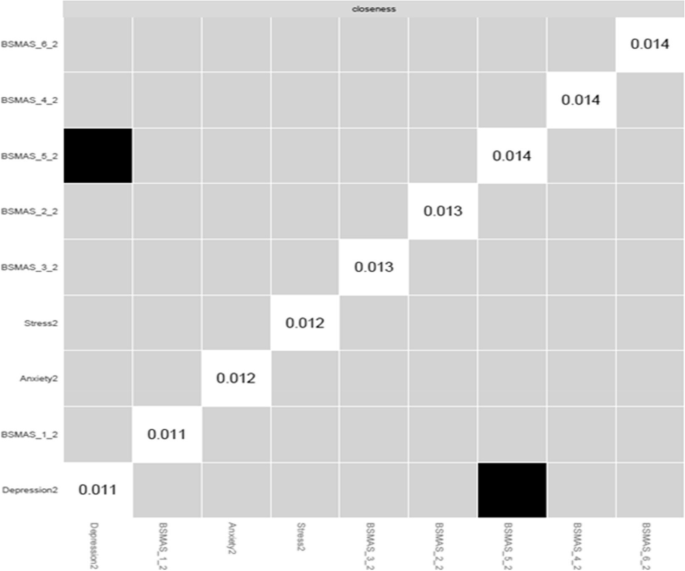

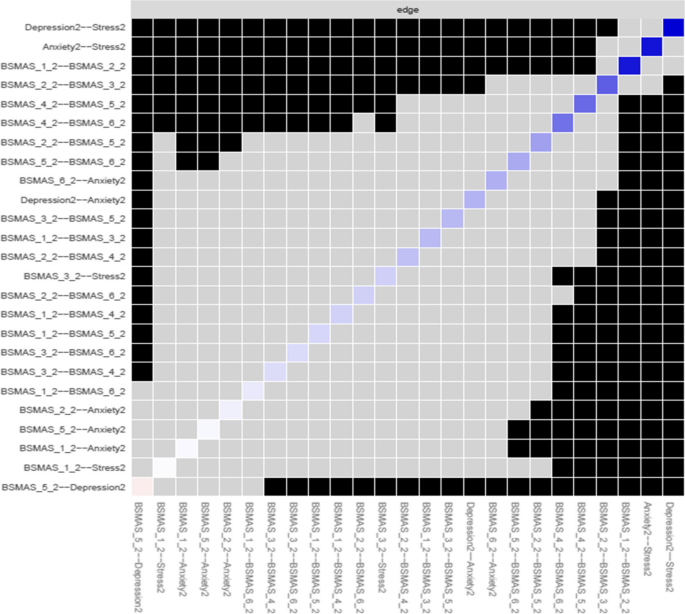

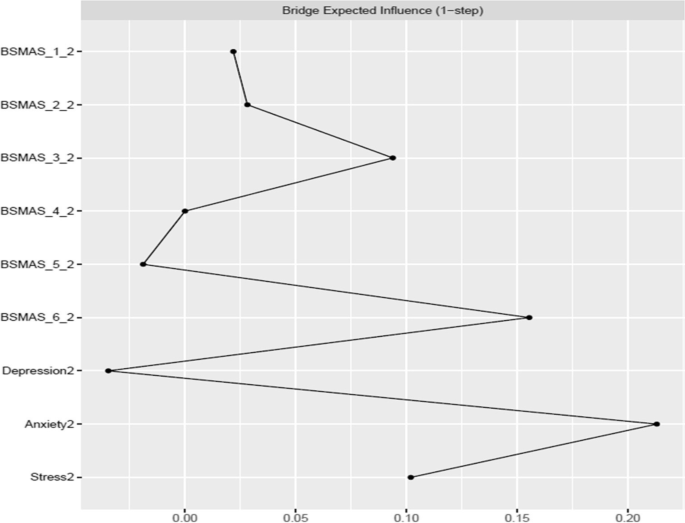

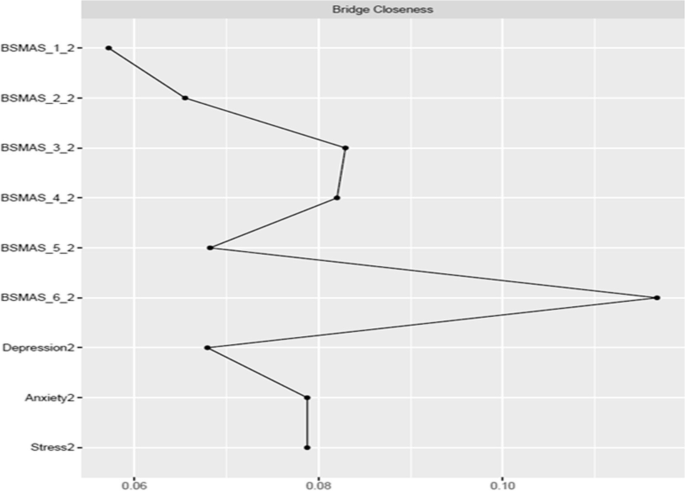

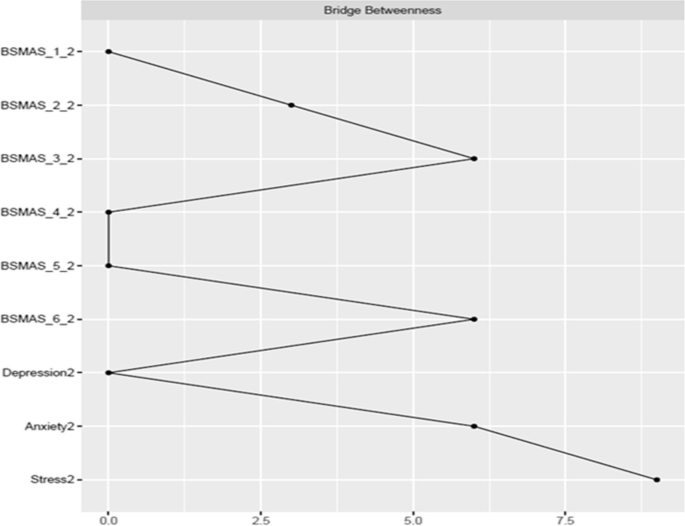

The full structural equation model was put to the test, to examine the mediation effect of psychological distress between self-compassion and SM addiction. The model revealed a good fit to our data [ χ 2 (87) = 177, P < .001, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.08, RMSEA = 0.06 (CI 0.05-0.08)], yet the standardized factor loadings for the SCS variables were found to be statistically nonsignificant. Inspection of the subscales’ correlations revealed insignificant criterion correlations only for the positive dimensions of the self-compassion variable. Specifically, the subscales of mindfulness, common humanity, and self-kindness exhibited very low or insignificant correlations to psychological distress and SM addiction ( Table 2 ). The standardized path coefficients of the structural model are presented in Figure 1 .

Structural equation model of self-compassion, psychological distress, and social media addiction. * P < .05, ** P < .001.

According to Neff, 27 the SCS examines 3 basic and interactive components, which pertains 2 opposite dimensions. Results revealed criterion correlations in the expected direction only for those dimensions/subscales that followed a negatively skewed response format (self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification). In addition, insignificant correlations were found for the positively skewed response subscales, namely the self-kindness, the common humanity, and the mindfulness subscale. Therefore, it was decided to test a modified structural equation model, including only the negatively keyed SCS facets. This modified measurement model yielded a significantly better fit to our data [ χ 2 (51) = 35.1, P < .001, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.00 (CI 0.00-0.03)] than the original SEM.

The tested mediational model predicted SM addiction. Table 3 presents the factor loadings of the modified structural equation model; standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.46 to 0.94 and were all statistically significant at P < .001. Self-compassion was found to have a significant direct effect on SM addiction and a significant indirect effect through psychological distress (see Figure 1 ). In sum, psychological distress is found to negatively correlate with self-compassion and positively relate to SM addiction and is perceived as a mediator among those concepts.

Unstandardized and Standardized Loadings for the Measurement Model (Including only the 3 Negative Subscales)

The present study investigated the link between SM addiction, self-compassion, and psychological distress, using data from Greek adults. As proposed, higher levels of self-compassion were associated with lower levels of SM app usage. These findings give prominence to the first hypothesis, since self-compassion strengthens individuals from expressing SM addiction and/or mental health problems. 18 , 36 Individuals who demonstrate higher levels of self-compassion tend to spend less time on SM apps and overall feel healthier.

Furthermore, our research findings indicated that psychological distress appeared to have an effect on SM addiction; individuals feeling highly distressed also tend to report higher levels of SM app addiction. This positive inclination to SM addiction was significant for all 3 negative psychological states, namely depression, anxiety, and stress. The findings from our study are similar to those reported from previous researches 2 , 18 ; prolonged exposure to SM platforms is associated with certain negative psychological consequences. Nonetheless, our findings expand our understanding on SM addiction, since results are not focused on a specific SM platform, or on a single SM user profile. Participants of this study were asked to report general tendencies toward all SM indiscriminately; therefore, inferences can be made from a general perspective.

Exploration of the mediation effect between the full spectrum of self-compassion, SM addiction, and psychological distress failed to explain how self-compassion enables a positive relation. Interestingly, examination of certain facets of self-compassion revealed that the concept’s negative counterparts, namely self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification, exhibit strong associations between SM addiction and psychological distress; in conjunction with previous findings, 18 only these negative facets are moderated by psychological distress.

With regard to our additional objective, current findings allow only statements about tendencies of Greek population toward SM addiction. Although the adopted BSMAS has not yet been examined for having critical cutoff scores on SM intensity, the critical cutoff scores suggested by Andreassen et al 12 were used. These cutoff scores were reached by a relatively low percentage of the Greek sample, indicating low levels of SM addiction. Intervention programs, promoting psychological well-being and coping with SM addiction, need to focus on the control, the acceptance, and the regulation of the self. 15 Our research findings shed light on the unexplored behavioral patterns regarding the use of SM and self-compassion, by emphasizing on the negative dimensions of self-compassion. The emphasis on the negative facets may be highly beneficial for establishing new intervention programs. For example, individuals who get easily upset with themselves during difficult life situations (or generally get easily stressed) tend to reveal symptoms of SM addiction more frequently. Conversely, individuals who understand how to fairly and honestly judge the time they spent on SM may be more aware of their potential problematic behavior and more stimulated to overcome such negative behaviors by themselves. Likewise, when individuals exhibit feelings of isolation to a greater extent, they feel more prone to get socially distanced and lessen the time they spend on SM, or effectively manage social interaction overload. 14 On the contrary, individuals who feel more acceptive of their thoughts and feelings are prone to excessive SM behavioral patterns and increase their possibility for expressing SM addiction.

The results from the present study should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. Firstly, only self-reported measures were used. Consequently social desirability is an issue that needs to be further addressed; results may have underestimated the prevalence of SM addiction among Greek adults. Secondly, the data used are not representative of the Greek population; males are underrepresented, and age, occupation status, and gender are presented unequally. It should also be noted that a large number of individuals use SM apps outside the range of the age or the occupational status included in our study. Thirdly, participants in this study have been recruited from self-selected processes, through snowball sampling procedures. Therefore, inferences on individuals’ SM additive behaviors may not be representative of the broader Greek population. Finally, research design did not account for information regarding problematic smartphone usage. 37 Smartphone and SM addiction are highly overlapping, since smartphones are predominantly used for social networking purposes. This lack of distinction between the smartphone and the SM addiction confounds our findings and affects the generalizability of our results.

Overall, the findings add to the existing literature by examining the relation and the mediation effect between self-compassion, SM addiction, and psychological distress. Results showed that psychological distress is a potential risk factor, while self-compassion is a potential protective factor for SM addiction. The mediating role of self-compassion is not easily endorsed, and more complex patterns of interventions toward the confinement of SM addiction need to be further established. Strengthening self-compassion and psychological well-being are potentially important components to be considered in social network addiction interventions targeting adults.

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethical committee approval was received from the Ethics Committee of the University of Crete (Approval No: 117/2022).

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from all participants who participated in this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept – E.M.; Design – E.M., M.K.; Supervision – E.M.; Funding – E.M., M.K., C.T.; Materials – E.M.; Data Collection and/or Processing – E.M.; Analysis and/or Interpretation – E.M., C.T.; Literature Review – E.M.; Writing Manuscript – E.M., C.T.; Critical Review – E.M., M.K.

Declaration of Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale Greek version

Παρακάτω ακολουθούν ορισμένες ερωτήσεις σχετικά με τη σχέση σας με τα μέσα κοινωνικής δικτύωσης και τι κάνετε με αυτά (όπως είναι για παράδειγμα το Facebook, το Instagram, κ.α.). Για κάθε ερώτηση επιλέξτε την απάντηση που σας περιγράφει καλύτερα.

- 1. Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Social networking sites and addiction: ten lessons learned. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):311 329. 10.3390/ijerph14030311) [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Kuss DJ, Pontes HM. Internet Addiction. Gottingen, Germany: Hogrefe Publishing Corporation; 2019. 10.1027/00501-000) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Andreassen CS, Pallesen S, Griffiths MD. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. Addict Behav. 2017;64:287 293. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006) [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: Author; 2000. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Bànyai F, Zsila Á, Kiràly O.et al. Problematic social media use: results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS One. 9,2017;12(1):e0169839. 10.1371/journal.pone.0169839) [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Müller KW, Dreier M, Beutel ME, Duven E, Giralt S, Wölfling K. A hidden type of internet addiction? Intense and addictive use of social networking sites in adolescents. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;55:172 177. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.007) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. De Cock RD, Vangeel J, Klein A, Minotte P, Rosas O, Meerkerk GJ. Compulsive use of social networking sites in Belgium: prevalence, profile and the role of attitude toward work and school. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17(3):166 171. 10.1089/cyber.2013.0029) [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Van den Eijnden RJJM, Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM. The social media disorder scale. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;61:478 487. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.038) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Moghavvemi S, Sulaiman AB, Jaafar NIB, Kasem N. Facebook and YouTube addiction: the usage pattern of Malaysian students. Paper presented at: International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (JCRIIS). Langkawi Island, Malaysia. Available at: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=8002516. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Tang CSK, Koh YYW. Online social networking addiction among college students in Singapore: comorbidity with behavioral addiction and affective disorder. Asian J Psychiatry. 2017;25:175 178. 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.10.027) [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Seabrook EM, Kern ML, Rickard NS. Social networking sites, depression and anxiety: a systematic review. JMIR Ment Health. 2016;3(4):e50. 10.2196/mental.5842) [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501 517. 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517) [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Cuadrado E, Rojas R, Tabernero C. Development and validation of the social network addiction scale (SNAddS-6S). Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2020;10(3):763 778. 10.3390/ejihpe10030056) [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Choi SB, Lim MS. Effects of social and technology overload on psychological well-being in young South Korean Adults: the mediatory role of social network service addiction. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;61:245 254. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.032) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Germer CK, Neff KD. Cultivating self-compassion in trauma survivors. In: Follete VM, Briere J, Rozelle D, Hopper JW, Rome DI.eds. Mindfulness-Oriented Interventions for Trauma: Integrating Contemplative Practices. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2015:43 58. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Bluth K, Blanton PW. Mindfulness and self-compassion: exploring pathways to adolescent emotional well-being. J Child Fam Stud. 2014;23(7):1298 1309. 10.1007/s10826-013-9830-2) [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Cândea DM, Szentágotai-Tâtar A. The impact of self-compassion on shame-proneness in social anxiety. Mindfulness. 2018;9(6):1816 1824. 10.1007/s12671-018-0924-1) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Keyte R, Mullis L, Egan H, Hussain M, Cook A, Mantzios M. Self-compassion and Instagram use is explained by the relation to anxiety, depression and stress. J Technol Behav Sci. 2021;6(2):436 441. 10.1007/s41347-020-00186-z) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Liu Q-Q, Yang X-J, Hu Y-T, Zhang C-Y. Peer victimization, self-compassion, gender and adolescent mobile phone addiction: unique and interactive effects. Child Youth Serv Rev . 2020;118. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105397) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Phillips WJ, Wisniewski AT. Self-compassion moderates the predictive effects of social media use profiles on depression and anxiety . Computers in Human Behavior Reports. 2021;4. 10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100128) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Wang Y, Wang X, Yang J, Zeng P, Lei L. Body talk on social networking sites, body surveillance, and body shame among young adults: the roles of self-compassion and gender. Sex Roles. 2020;82(11-12):731 742. 10.1007/s11199-019-01084-2) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Keutler M, McHugh L. Self-compassion buffers the effect of perfectionistic self-presentation on social median on wellbeing. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2022;23:53 58. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.11.006) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, Spada MM. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:274 281. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.007) [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335 343. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u) [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Brailovskaia J, Rohmann E, Bierhoff HW, Schillack H, Margraf J. The relationship between daily stress, social support and Facebook addiction disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2019;276:167 174. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.014) [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Harkness J, Schoua-Glusberg A. Questionnaires in translation. In: Harkness J.ed., Cross-Cultural Survey Equivalence. Mannheim: Zentrum für Umfragen , Methoden und Analysen; 1998:87 126. Available at: https://nbnresolving.org/urn :nbn:de:0168-ssoar-49733-1. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2(3):223 250. 10.1080/15298860309027) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Mantzios M, Wilson JC, Giannou K. Psychometric properties of the Greek versions of the Self-Compassion and Mindful Attention and Awareness Scales. Mindfulness. 2015;6(1):123 132. 10.1007/s12671-013-0237-3) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Lyrakos GN, Arvaniti C, Smyrnioti M, Kostopanagiotou G. Translation and validation study of the depression anxiety stress scale in the Greek general population and in a psychiatric patient’s sample. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(S2):1731 1731. 10.1016/S0924-9338(11)73435-6) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Razali NM, Wah YB. Power comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling tests. J Stat Model Anal. 2011;2:21 33. [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. MacCallum RC, Austin JT. Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:201 226. 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.201) [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(4):422 445. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422) [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. DiStefano C. Examining fit with structural equation models. In: Schweizer K, DiStefano C.eds. Principles and Methods of Test Construction: Standards and Recent Advances. Göttingen: , Germany: Hogrefe; 2016:166 196. [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1 55. 10.1080/10705519909540118) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Andreassen CS, Pallesen S. Social network site addiction: an overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(25):4053 4061. 10.2174/13816128113199990616) [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Marino C, Canale N, Melodia F, Spada MM, Vieno A. The overlap between problematic Smartphone use and problematic social media use: a systematic review. Curr Addict Rep. 2021;8(4):469 480. 10.1007/s40429-021-00398-0) [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (329.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

A review of theories and models applied in studies of social media addiction and implications for future research

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Information, The University of Texas at Austin, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 School of Information, The University of Texas at Austin, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 33268185

- DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106699

With the increasing use of social media, the addictive use of this new technology also grows. Previous studies found that addictive social media use is associated with negative consequences such as reduced productivity, unhealthy social relationships, and reduced life-satisfaction. However, a holistic theoretical understanding of how social media addiction develops is still lacking, which impedes practical research that aims at designing educational and other intervention programs to prevent social media addiction. In this study, we reviewed 25 distinct theories/models that guided the research design of 55 empirical studies of social media addiction to identify theoretical perspectives and constructs that have been examined to explain the development of social media addiction. Limitations of the existing theoretical frameworks were identified, and future research areas are proposed.

Keywords: Facebook addiction; Internet addiction; Literature review; Problematic use; Social media addiction; Theoretical framework.

Copyright © 2020 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Behavior, Addictive*

- Internet Addiction Disorder

- Interpersonal Relations

- Social Media*

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Research trends in social media addiction and problematic social media use: a bibliometric analysis.

- 1 Sasin School of Management, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

- 2 Business Administration Division, Mahidol University International College, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand

Despite their increasing ubiquity in people's lives and incredible advantages in instantly interacting with others, social media's impact on subjective well-being is a source of concern worldwide and calls for up-to-date investigations of the role social media plays in mental health. Much research has discovered how habitual social media use may lead to addiction and negatively affect adolescents' school performance, social behavior, and interpersonal relationships. The present study was conducted to review the extant literature in the domain of social media and analyze global research productivity during 2013–2022. Bibliometric analysis was conducted on 501 articles that were extracted from the Scopus database using the keywords social media addiction and problematic social media use. The data were then uploaded to VOSviewer software to analyze citations, co-citations, and keyword co-occurrences. Volume, growth trajectory, geographic distribution of the literature, influential authors, intellectual structure of the literature, and the most prolific publishing sources were analyzed. The bibliometric analysis presented in this paper shows that the US, the UK, and Turkey accounted for 47% of the publications in this field. Most of the studies used quantitative methods in analyzing data and therefore aimed at testing relationships between variables. In addition, the findings in this study show that most analysis were cross-sectional. Studies were performed on undergraduate students between the ages of 19–25 on the use of two social media platforms: Facebook and Instagram. Limitations as well as research directions for future studies are also discussed.

Introduction

Social media generally refers to third-party internet-based platforms that mainly focus on social interactions, community-based inputs, and content sharing among its community of users and only feature content created by their users and not that licensed from third parties ( 1 ). Social networking sites such as Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok are prominent examples of social media that allow people to stay connected in an online world regardless of geographical distance or other obstacles ( 2 , 3 ). Recent evidence suggests that social networking sites have become increasingly popular among adolescents following the strict policies implemented by many countries to counter the COVID-19 pandemic, including social distancing, “lockdowns,” and quarantine measures ( 4 ). In this new context, social media have become an essential part of everyday life, especially for children and adolescents ( 5 ). For them such media are a means of socialization that connect people together. Interestingly, social media are not only used for social communication and entertainment purposes but also for sharing opinions, learning new things, building business networks, and initiate collaborative projects ( 6 ).

Among the 7.91 billion people in the world as of 2022, 4.62 billion active social media users, and the average time individuals spent using the internet was 6 h 58 min per day with an average use of social media platforms of 2 h and 27 min ( 7 ). Despite their increasing ubiquity in people's lives and the incredible advantages they offer to instantly interact with people, an increasing number of studies have linked social media use to negative mental health consequences, such as suicidality, loneliness, and anxiety ( 8 ). Numerous sources have expressed widespread concern about the effects of social media on mental health. A 2011 report by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) identifies a phenomenon known as Facebook depression which may be triggered “when preteens and teens spend a great deal of time on social media sites, such as Facebook, and then begin to exhibit classic symptoms of depression” ( 9 ). Similarly, the UK's Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) claims that there is a clear evidence of the relationship between social media use and mental health issues based on a survey of nearly 1,500 people between the ages of 14–24 ( 10 ). According to some authors, the increase in usage frequency of social media significantly increases the risks of clinical disorders described (and diagnosed) as “Facebook depression,” “fear of missing out” (FOMO), and “social comparison orientation” (SCO) ( 11 ). Other risks include sexting ( 12 ), social media stalking ( 13 ), cyber-bullying ( 14 ), privacy breaches ( 15 ), and improper use of technology. Therefore, social media's impact on subjective well-being is a source of concern worldwide and calls for up-to-date investigations of the role social media plays with regard to mental health ( 8 ). Many studies have found that habitual social media use may lead to addiction and thus negatively affect adolescents' school performance, social behavior, and interpersonal relationships ( 16 – 18 ). As a result of addiction, the user becomes highly engaged with online activities motivated by an uncontrollable desire to browse through social media pages and “devoting so much time and effort to it that it impairs other important life areas” ( 19 ).

Given these considerations, the present study was conducted to review the extant literature in the domain of social media and analyze global research productivity during 2013–2022. The study presents a bibliometric overview of the leading trends with particular regard to “social media addiction” and “problematic social media use.” This is valuable as it allows for a comprehensive overview of the current state of this field of research, as well as identifies any patterns or trends that may be present. Additionally, it provides information on the geographical distribution and prolific authors in this area, which may help to inform future research endeavors.

In terms of bibliometric analysis of social media addiction research, few studies have attempted to review the existing literature in the domain extensively. Most previous bibliometric studies on social media addiction and problematic use have focused mainly on one type of screen time activity such as digital gaming or texting ( 20 ) and have been conducted with a focus on a single platform such as Facebook, Instagram, or Snapchat ( 21 , 22 ). The present study adopts a more comprehensive approach by including all social media platforms and all types of screen time activities in its analysis.

Additionally, this review aims to highlight the major themes around which the research has evolved to date and draws some guidance for future research directions. In order to meet these objectives, this work is oriented toward answering the following research questions:

(1) What is the current status of research focusing on social media addiction?

(2) What are the key thematic areas in social media addiction and problematic use research?

(3) What is the intellectual structure of social media addiction as represented in the academic literature?

(4) What are the key findings of social media addiction and problematic social media research?

(5) What possible future research gaps can be identified in the field of social media addiction?

These research questions will be answered using bibliometric analysis of the literature on social media addiction and problematic use. This will allow for an overview of the research that has been conducted in this area, including information on the most influential authors, journals, countries of publication, and subject areas of study. Part 2 of the study will provide an examination of the intellectual structure of the extant literature in social media addiction while Part 3 will discuss the research methodology of the paper. Part 4 will discuss the findings of the study followed by a discussion under Part 5 of the paper. Finally, in Part 7, gaps in current knowledge about this field of research will be identified.

Literature review

Social media addiction research context.

Previous studies on behavioral addictions have looked at a lot of different factors that affect social media addiction focusing on personality traits. Although there is some inconsistency in the literature, numerous studies have focused on three main personality traits that may be associated with social media addiction, namely anxiety, depression, and extraversion ( 23 , 24 ).

It has been found that extraversion scores are strongly associated with increased use of social media and addiction to it ( 25 , 26 ). People with social anxiety as well as people who have psychiatric disorders often find online interactions extremely appealing ( 27 ). The available literature also reveals that the use of social media is positively associated with being female, single, and having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), or anxiety ( 28 ).

In a study by Seidman ( 29 ), the Big Five personality traits were assessed using Saucier's ( 30 ) Mini-Markers Scale. Results indicated that neurotic individuals use social media as a safe place for expressing their personality and meet belongingness needs. People affected by neurosis tend to use online social media to stay in touch with other people and feel better about their social lives ( 31 ). Narcissism is another factor that has been examined extensively when it comes to social media, and it has been found that people who are narcissistic are more likely to become addicted to social media ( 32 ). In this case users want to be seen and get “likes” from lots of other users. Longstreet and Brooks ( 33 ) did a study on how life satisfaction depends on how much money people make. Life satisfaction was found to be negatively linked to social media addiction, according to the results. When social media addiction decreases, the level of life satisfaction rises. But results show that in lieu of true-life satisfaction people use social media as a substitute (for temporary pleasure vs. longer term happiness).

Researchers have discovered similar patterns in students who tend to rank high in shyness: they find it easier to express themselves online rather than in person ( 34 , 35 ). With the use of social media, shy individuals have the opportunity to foster better quality relationships since many of their anxiety-related concerns (e.g., social avoidance and fear of social devaluation) are significantly reduced ( 36 , 37 ).

Problematic use of social media

The amount of research on problematic use of social media has dramatically increased since the last decade. But using social media in an unhealthy manner may not be considered an addiction or a disorder as this behavior has not yet been formally categorized as such ( 38 ). Although research has shown that people who use social media in a negative way often report negative health-related conditions, most of the data that have led to such results and conclusions comprise self-reported data ( 39 ). The dimensions of excessive social media usage are not exactly known because there are not enough diagnostic criteria and not enough high-quality long-term studies available yet. This is what Zendle and Bowden-Jones ( 40 ) noted in their own research. And this is why terms like “problematic social media use” have been used to describe people who use social media in a negative way. Furthermore, if a lot of time is spent on social media, it can be hard to figure out just when it is being used in a harmful way. For instance, people easily compare their appearance to what they see on social media, and this might lead to low self-esteem if they feel they do not look as good as the people they are following. According to research in this domain, the extent to which an individual engages in photo-related activities (e.g., taking selfies, editing photos, checking other people's photos) on social media is associated with negative body image concerns. Through curated online images of peers, adolescents face challenges to their self-esteem and sense of self-worth and are increasingly isolated from face-to-face interaction.

To address this problem the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) has been used by some scholars ( 41 , 42 ). These scholars have used criteria from the DSM-V to describe one problematic social media use, internet gaming disorder, but such criteria could also be used to describe other types of social media disorders. Franchina et al. ( 43 ) and Scott and Woods ( 44 ), for example, focus their attention on individual-level factors (like fear of missing out) and family-level factors (like childhood abuse) that have been used to explain why people use social media in a harmful way. Friends-level factors have also been explored as a social well-being measurement to explain why people use social media in a malevolent way and demonstrated significant positive correlations with lower levels of friend support ( 45 ). Macro-level factors have also been suggested, such as the normalization of surveillance ( 46 ) and the ability to see what people are doing online ( 47 ). Gender and age seem to be highly associated to the ways people use social media negatively. Particularly among girls, social media use is consistently associated with mental health issues ( 41 , 48 , 49 ), an association more common among older girls than younger girls ( 46 , 48 ).

Most studies have looked at the connection between social media use and its effects (such as social media addiction) and a number of different psychosomatic disorders. In a recent study conducted by Vannucci and Ohannessian ( 50 ), the use of social media appears to have a variety of effects “on psychosocial adjustment during early adolescence, with high social media use being the most problematic.” It has been found that people who use social media in a harmful way are more likely to be depressed, anxious, have low self-esteem, be more socially isolated, have poorer sleep quality, and have more body image dissatisfaction. Furthermore, harmful social media use has been associated with unhealthy lifestyle patterns (for example, not getting enough exercise or having trouble managing daily obligations) as well as life threatening behaviors such as illicit drug use, excessive alcohol consumption and unsafe sexual practices ( 51 , 52 ).

A growing body of research investigating social media use has revealed that the extensive use of social media platforms is correlated with a reduced performance on cognitive tasks and in mental effort ( 53 ). Overall, it appears that individuals who have a problematic relationship with social media or those who use social media more frequently are more likely to develop negative health conditions.

Social media addiction and problematic use systematic reviews

Previous studies have revealed the detrimental impacts of social media addiction on users' health. A systematic review by Khan and Khan ( 20 ) has pointed out that social media addiction has a negative impact on users' mental health. For example, social media addiction can lead to stress levels rise, loneliness, and sadness ( 54 ). Anxiety is another common mental health problem associated with social media addiction. Studies have found that young adolescents who are addicted to social media are more likely to suffer from anxiety than people who are not addicted to social media ( 55 ). In addition, social media addiction can also lead to physical health problems, such as obesity and carpal tunnel syndrome a result of spending too much time on the computer ( 22 ).

Apart from the negative impacts of social media addiction on users' mental and physical health, social media addiction can also lead to other problems. For example, social media addiction can lead to financial problems. A study by Sharif and Yeoh ( 56 ) has found that people who are addicted to social media tend to spend more money than those who are not addicted to social media. In addition, social media addiction can also lead to a decline in academic performance. Students who are addicted to social media are more likely to have lower grades than those who are not addicted to social media ( 57 ).

Research methodology

Bibliometric analysis.

Merigo et al. ( 58 ) use bibliometric analysis to examine, organize, and analyze a large body of literature from a quantitative, objective perspective in order to assess patterns of research and emerging trends in a certain field. A bibliometric methodology is used to identify the current state of the academic literature, advance research. and find objective information ( 59 ). This technique allows the researchers to examine previous scientific work, comprehend advancements in prior knowledge, and identify future study opportunities.

To achieve this objective and identify the research trends in social media addiction and problematic social media use, this study employs two bibliometric methodologies: performance analysis and science mapping. Performance analysis uses a series of bibliometric indicators (e.g., number of annual publications, document type, source type, journal impact factor, languages, subject area, h-index, and countries) and aims at evaluating groups of scientific actors on a particular topic of research. VOSviewer software ( 60 ) was used to carry out the science mapping. The software is used to visualize a particular body of literature and map the bibliographic material using the co-occurrence analysis of author, index keywords, nations, and fields of publication ( 61 , 62 ).

Data collection

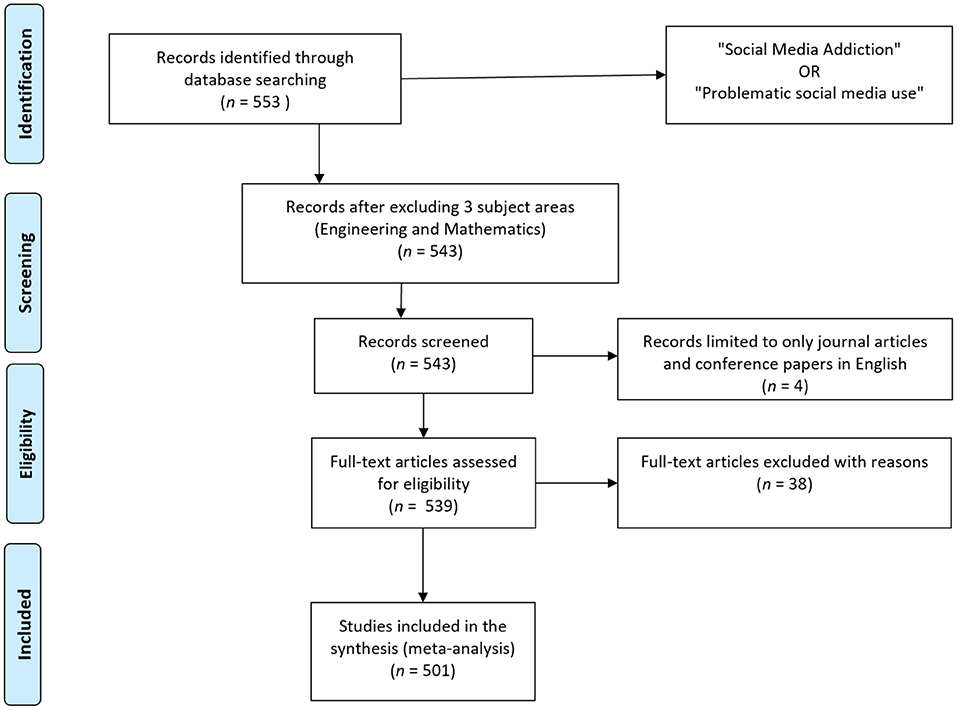

After picking keywords, designing the search strings, and building up a database, the authors conducted a bibliometric literature search. Scopus was utilized to gather exploration data since it is a widely used database that contains the most comprehensive view of the world's research output and provides one of the most effective search engines. If the research was to be performed using other database such as Web Of Science or Google Scholar the authors may have obtained larger number of articles however they may not have been all particularly relevant as Scopus is known to have the most widest and most relevant scholar search engine in marketing and social science. A keyword search for “social media addiction” OR “problematic social media use” yielded 553 papers, which were downloaded from Scopus. The information was gathered in March 2022, and because the Scopus database is updated on a regular basis, the results may change in the future. Next, the authors examined the titles and abstracts to see whether they were relevant to the topics treated. There were two common grounds for document exclusion. First, while several documents emphasized the negative effects of addiction in relation to the internet and digital media, they did not focus on social networking sites specifically. Similarly, addiction and problematic consumption habits were discussed in relation to social media in several studies, although only in broad terms. This left a total of 511 documents. Articles were then limited only to journal articles, conference papers, reviews, books, and only those published in English. This process excluded 10 additional documents. Then, the relevance of the remaining articles was finally checked by reading the titles, abstracts, and keywords. Documents were excluded if social networking sites were only mentioned as a background topic or very generally. This resulted in a final selection of 501 research papers, which were then subjected to bibliometric analysis (see Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flowchart showing the search procedures used in the review.

After identifying 501 Scopus files, bibliographic data related to these documents were imported into an Excel sheet where the authors' names, their affiliations, document titles, keywords, abstracts, and citation figures were analyzed. These were subsequently uploaded into VOSViewer software version 1.6.8 to begin the bibliometric review. Descriptive statistics were created to define the whole body of knowledge about social media addiction and problematic social media use. VOSViewer was used to analyze citation, co-citation, and keyword co-occurrences. According to Zupic and Cater ( 63 ), co-citation analysis measures the influence of documents, authors, and journals heavily cited and thus considered influential. Co-citation analysis has the objective of building similarities between authors, journals, and documents and is generally defined as the frequency with which two units are cited together within the reference list of a third article.

The implementation of social media addiction performance analysis was conducted according to the models recently introduced by Karjalainen et al. ( 64 ) and Pattnaik ( 65 ). Throughout the manuscript there are operational definitions of relevant terms and indicators following a standardized bibliometric approach. The cumulative academic impact (CAI) of the documents was measured by the number of times they have been cited in other scholarly works while the fine-grained academic impact (FIA) was computed according to the authors citation analysis and authors co-citation analysis within the reference lists of documents that have been specifically focused on social media addiction and problematic social media use.

Results of the study presented here include the findings on social media addiction and social media problematic use. The results are presented by the foci outlined in the study questions.

Volume, growth trajectory, and geographic distribution of the literature

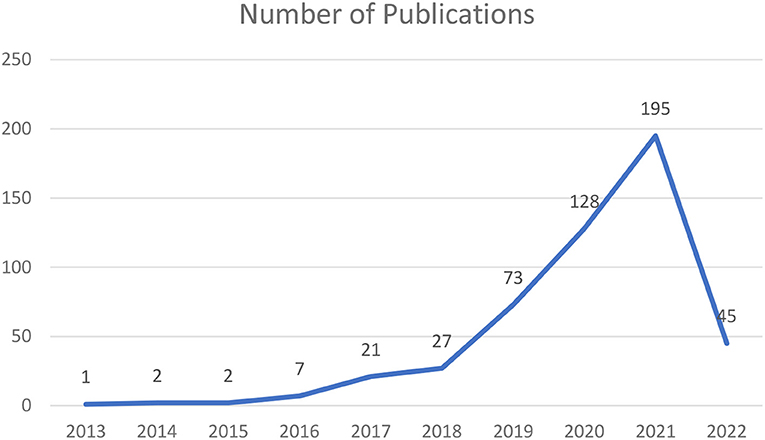

After performing the Scopus-based investigation of the current literature regarding social media addiction and problematic use of social media, the authors obtained a knowledge base consisting of 501 documents comprising 455 journal articles, 27 conference papers, 15 articles reviews, 3 books and 1 conference review. The included literature was very recent. As shown in Figure 2 , publication rates started very slowly in 2013 but really took off in 2018, after which publications dramatically increased each year until a peak was reached in 2021 with 195 publications. Analyzing the literature published during the past decade reveals an exponential increase in scholarly production on social addiction and its problematic use. This might be due to the increasingly widespread introduction of social media sites in everyday life and the ubiquitous diffusion of mobile devices that have fundamentally impacted human behavior. The dip in the number of publications in 2022 is explained by the fact that by the time the review was carried out the year was not finished yet and therefore there are many articles still in press.

Figure 2 . Annual volume of social media addiction or social media problematic use ( n = 501).

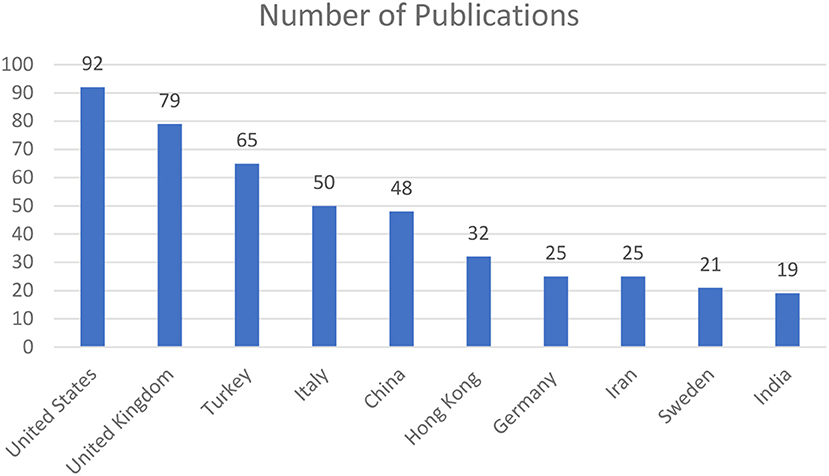

The geographical distribution trends of scholarly publications on social media addiction or problematic use of social media are highlighted in Figure 3 . The articles were assigned to a certain country according to the nationality of the university with whom the first author was affiliated with. The figure shows that the most productive countries are the USA (92), the U.K. (79), and Turkey ( 63 ), which combined produced 236 articles, equal to 47% of the entire scholarly production examined in this bibliometric analysis. Turkey has slowly evolved in various ways with the growth of the internet and social media. Anglo-American scholarly publications on problematic social media consumer behavior represent the largest research output. Yet it is interesting to observe that social networking sites studies are attracting many researchers in Asian countries, particularly China. For many Chinese people, social networking sites are a valuable opportunity to involve people in political activism in addition to simply making purchases ( 66 ).

Figure 3 . Global dispersion of social networking sites in relation to social media addiction or social media problematic use.

Analysis of influential authors

This section analyses the high-impact authors in the Scopus-indexed knowledge base on social networking sites in relation to social media addiction or problematic use of social media. It provides valuable insights for establishing patterns of knowledge generation and dissemination of literature about social networking sites relating to addiction and problematic use.

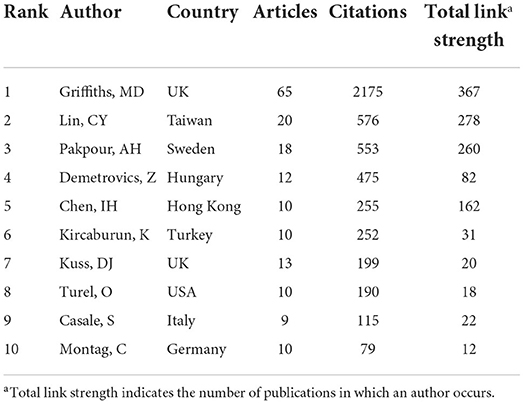

Table 1 acknowledges the top 10 most highly cited authors with the highest total citations in the database.

Table 1 . Highly cited authors on social media addiction and problematic use ( n = 501).

Table 1 shows that MD Griffiths (sixty-five articles), CY Lin (twenty articles), and AH Pakpour (eighteen articles) are the most productive scholars according to the number of Scopus documents examined in the area of social media addiction and its problematic use . If the criteria are changed and authors ranked according to the overall number of citations received in order to determine high-impact authors, the same three authors turn out to be the most highly cited authors. It should be noted that these highly cited authors tend to enlist several disciplines in examining social media addiction and problematic use. Griffiths, for example, focuses on behavioral addiction stemming from not only digital media usage but also from gambling and video games. Lin, on the other hand, focuses on the negative effects that the internet and digital media can have on users' mental health, and Pakpour approaches the issue from a behavioral medicine perspective.

Intellectual structure of the literature

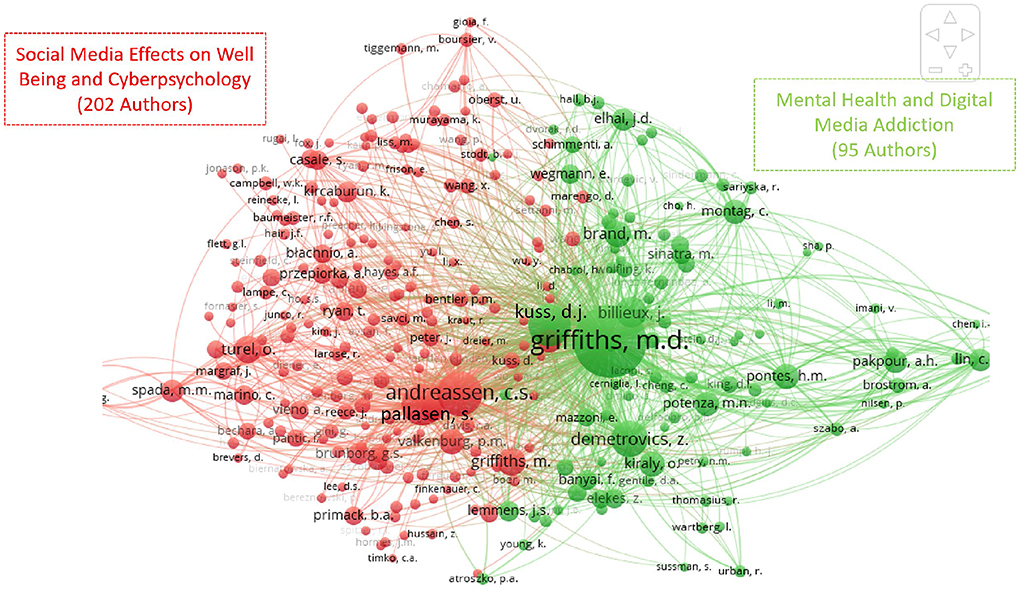

In this part of the paper, the authors illustrate the “intellectual structure” of the social media addiction and the problematic use of social media's literature. An author co-citation analysis (ACA) was performed which is displayed as a figure that depicts the relations between highly co-cited authors. The study of co-citation assumes that strongly co-cited authors carry some form of intellectual similarity ( 67 ). Figure 4 shows the author co-citation map. Nodes represent units of analysis (in this case scholars) and network ties represent similarity connections. Nodes are sized according to the number of co-citations received—the bigger the node, the more co-citations it has. Adjacent nodes are considered intellectually similar.

Figure 4 . Two clusters, representing the intellectual structure of the social media and its problematic use literature.

Scholars belonging to the green cluster (Mental Health and Digital Media Addiction) have extensively published on medical analysis tools and how these can be used to heal users suffering from addiction to digital media, which can range from gambling, to internet, to videogame addictions. Scholars in this school of thought focus on the negative effects on users' mental health, such as depression, anxiety, and personality disturbances. Such studies focus also on the role of screen use in the development of mental health problems and the increasing use of medical treatments to address addiction to digital media. They argue that addiction to digital media should be considered a mental health disorder and treatment options should be made available to users.

In contrast, scholars within the red cluster (Social Media Effects on Well Being and Cyberpsychology) have focused their attention on the effects of social media toward users' well-being and how social media change users' behavior, focusing particular attention on the human-machine interaction and how methods and models can help protect users' well-being. Two hundred and two authors belong to this group, the top co-cited being Andreassen (667 co-citations), Pallasen (555 co-citations), and Valkenburg (215 co-citations). These authors have extensively studied the development of addiction to social media, problem gambling, and internet addiction. They have also focused on the measurement of addiction to social media, cyberbullying, and the dark side of social media.

Most influential source title in the field of social media addiction and its problematic use

To find the preferred periodicals in the field of social media addiction and its problematic use, the authors have selected 501 articles published in 263 journals. Table 2 gives a ranked list of the top 10 journals that constitute the core publishing sources in the field of social media addiction research. In doing so, the authors analyzed the journal's impact factor, Scopus Cite Score, h-index, quartile ranking, and number of publications per year.

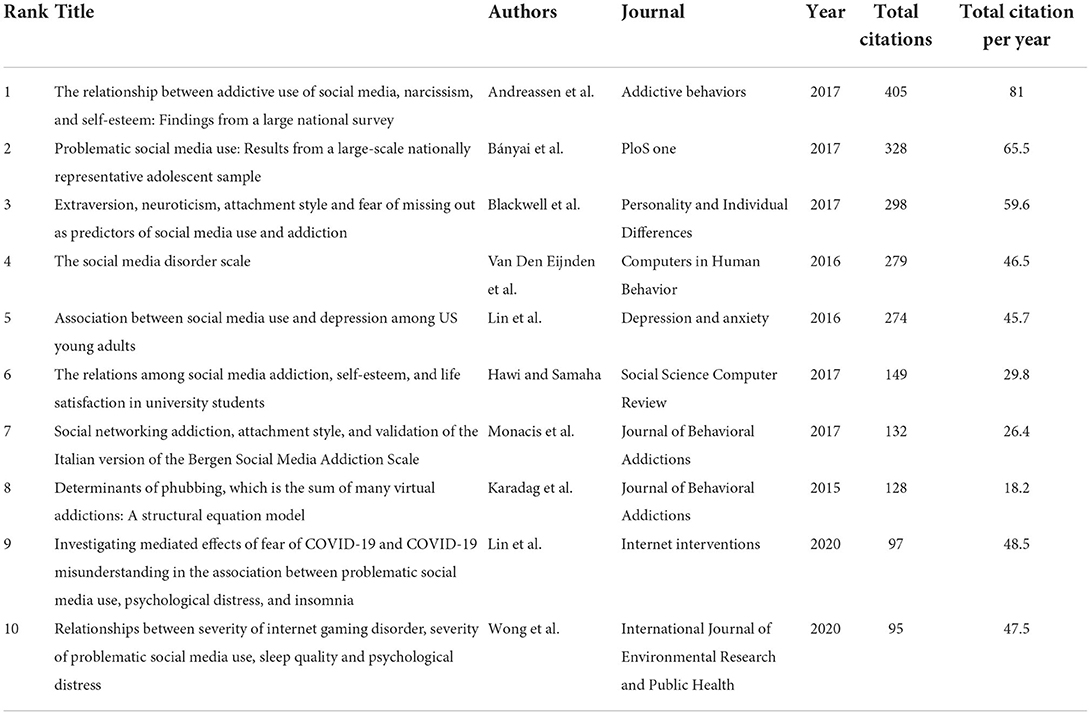

Table 2 . Top 10 most cited and more frequently mentioned documents in the field of social media addiction.

The journal Addictive Behaviors topped the list, with 700 citations and 22 publications (4.3%), followed by Computers in Human Behaviors , with 577 citations and 13 publications (2.5%), Journal of Behavioral Addictions , with 562 citations and 17 publications (3.3%), and International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction , with 502 citations and 26 publications (5.1%). Five of the 10 most productive journals in the field of social media addiction research are published by Elsevier (all Q1 rankings) while Springer and Frontiers Media published one journal each.

Documents citation analysis identified the most influential and most frequently mentioned documents in a certain scientific field. Andreassen has received the most citations among the 10 most significant papers on social media addiction, with 405 ( Table 2 ). The main objective of this type of studies was to identify the associations and the roles of different variables as predictors of social media addiction (e.g., ( 19 , 68 , 69 )). According to general addiction models, the excessive and problematic use of digital technologies is described as “being overly concerned about social media, driven by an uncontrollable motivation to log on to or use social media, and devoting so much time and effort to social media that it impairs other important life areas” ( 27 , 70 ). Furthermore, the purpose of several highly cited studies ( 31 , 71 ) was to analyse the connections between young adults' sleep quality and psychological discomfort, depression, self-esteem, and life satisfaction and the severity of internet and problematic social media use, since the health of younger generations and teenagers is of great interest this may help explain the popularity of such papers. Despite being the most recent publication Lin et al.'s work garnered more citations annually. The desire to quantify social media addiction in individuals can also help explain the popularity of studies which try to develop measurement scales ( 42 , 72 ). Some of the highest-ranked publications are devoted to either the presentation of case studies or testing relationships among psychological constructs ( 73 ).

Keyword co-occurrence analysis

The research question, “What are the key thematic areas in social media addiction literature?” was answered using keyword co-occurrence analysis. Keyword co-occurrence analysis is conducted to identify research themes and discover keywords. It mainly examines the relationships between co-occurrence keywords in a wide variety of literature ( 74 ). In this approach, the idea is to explore the frequency of specific keywords being mentioned together.

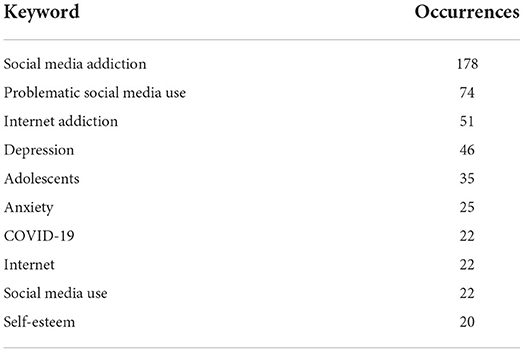

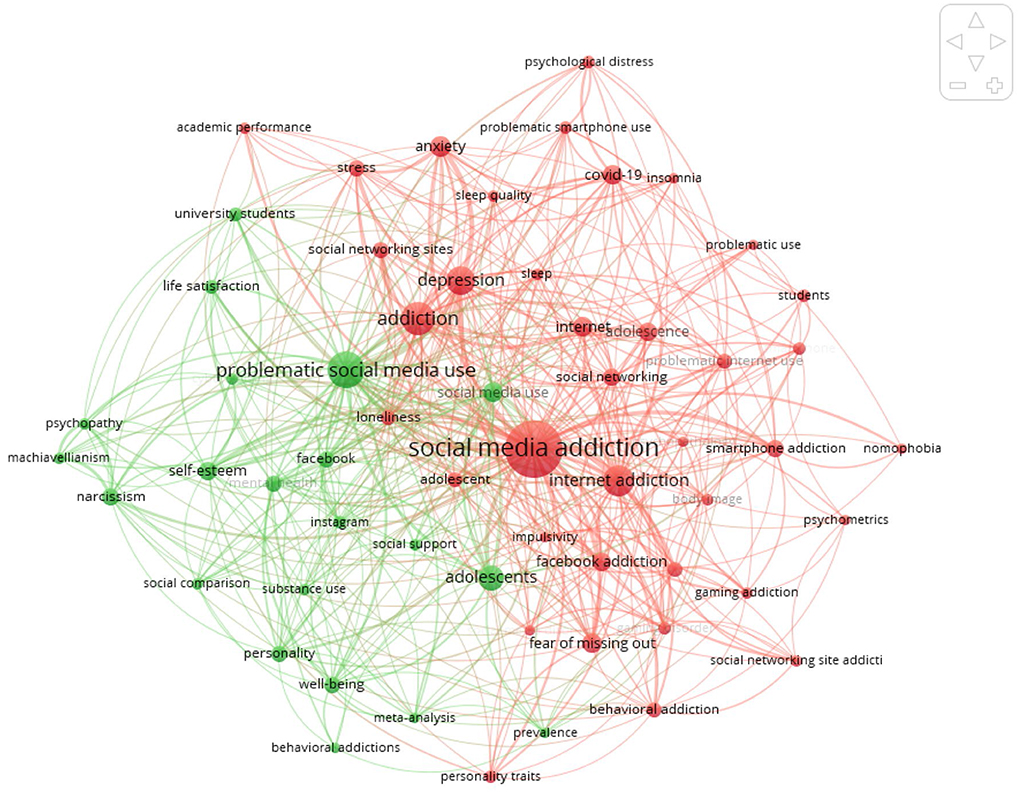

Utilizing VOSviewer, the authors conducted a keyword co-occurrence analysis to characterize and review the developing trends in the field of social media addiction. The top 10 most frequent keywords are presented in Table 3 . The results indicate that “social media addiction” is the most frequent keyword (178 occurrences), followed by “problematic social media use” (74 occurrences), “internet addiction” (51 occurrences), and “depression” (46 occurrences). As shown in the co-occurrence network ( Figure 5 ), the keywords can be grouped into two major clusters. “Problematic social media use” can be identified as the core theme of the green cluster. In the red cluster, keywords mainly identify a specific aspect of problematic social media use: social media addiction.

Table 3 . Frequency of occurrence of top 10 keywords.

Figure 5 . Keywords co-occurrence map. Threshold: 5 co-occurrences.

The results of the keyword co-occurrence analysis for journal articles provide valuable perspectives and tools for understanding concepts discussed in past studies of social media usage ( 75 ). More precisely, it can be noted that there has been a large body of research on social media addiction together with other types of technological addictions, such as compulsive web surfing, internet gaming disorder, video game addiction and compulsive online shopping ( 76 – 78 ). This field of research has mainly been directed toward teenagers, middle school students, and college students and university students in order to understand the relationship between social media addiction and mental health issues such as depression, disruptions in self-perceptions, impairment of social and emotional activity, anxiety, neuroticism, and stress ( 79 – 81 ).

The findings presented in this paper show that there has been an exponential increase in scholarly publications—from two publications in 2013 to 195 publications in 2021. There were 45 publications in 2022 at the time this study was conducted. It was interesting to observe that the US, the UK, and Turkey accounted for 47% of the publications in this field even though none of these countries are in the top 15 countries in terms of active social media penetration ( 82 ) although the US has the third highest number of social media users ( 83 ). Even though China and India have the highest number of social media users ( 83 ), first and second respectively, they rank fifth and tenth in terms of publications on social media addiction or problematic use of social media. In fact, the US has almost double the number of publications in this field compared to China and almost five times compared to India. Even though East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia make up the top three regions in terms of worldwide social media users ( 84 ), except for China and India there have been only a limited number of publications on social media addiction or problematic use. An explanation for that could be that there is still a lack of awareness on the negative consequences of the use of social media and the impact it has on the mental well-being of users. More research in these regions should perhaps be conducted in order to understand the problematic use and addiction of social media so preventive measures can be undertaken.

From the bibliometric analysis, it was found that most of the studies examined used quantitative methods in analyzing data and therefore aimed at testing relationships between variables. In addition, many studies were empirical, aimed at testing relationships based on direct or indirect observations of social media use. Very few studies used theories and for the most part if they did they used the technology acceptance model and social comparison theories. The findings presented in this paper show that none of the studies attempted to create or test new theories in this field, perhaps due to the lack of maturity of the literature. Moreover, neither have very many qualitative studies been conducted in this field. More qualitative research in this field should perhaps be conducted as it could explore the motivations and rationales from which certain users' behavior may arise.

The authors found that almost all the publications on social media addiction or problematic use relied on samples of undergraduate students between the ages of 19–25. The average daily time spent by users worldwide on social media applications was highest for users between the ages of 40–44, at 59.85 min per day, followed by those between the ages of 35–39, at 59.28 min per day, and those between the ages of 45–49, at 59.23 per day ( 85 ). Therefore, more studies should be conducted exploring different age groups, as users between the ages of 19–25 do not represent the entire population of social media users. Conducting studies on different age groups may yield interesting and valuable insights to the field of social media addiction. For example, it would be interesting to measure the impacts of social media use among older users aged 50 years or older who spend almost the same amount of time on social media as other groups of users (56.43 min per day) ( 85 ).