Find anything you save across the site in your account

Something About Kathy

By Louis Menand

Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Never Let Me Go” (Knopf; $24) is a novel about a young woman named Kathy H., and her friendships with two schoolmates, Ruth and Tommy. The triangle is a standard one: Kathy is attracted to Tommy; Tommy gets involved with Ruth, who is also Kathy’s best friend; Ruth knows that Tommy is really in love with Kathy; Kathy gets Tommy in the end, although they both realize that it is too late, and that they have missed their best years. Their lives are short; they know that they are doomed. So the small betrayal leaves an enormous wound. As is customary with Ishiguro, the narrator, Kathy, is ingenuous but keenly desirous of telling us how it was, the prose feels self-consciously stilted and banal, and the psychology is not deep. The central premise in this book is basically the same as that in the book that made Ishiguro famous, “The Remains of the Day” (1989): even when happiness is standing right in front of you, it’s very hard to grasp. Probably you already suspected that.

It is always a puzzle to know where Ishiguro’s true subject lies. The emotional situation in his novels is spelled out in meticulous, sometimes comically tedious detail, and the focus is entirely on the narrator’s struggles to achieve clarity and contentment in an uncoöperative world. Ishiguro is expert at getting readers choked up over these struggles—even over the ludicrous self-deceptions of the butler in “The Remains of the Day,” the hopeless Stevens. But he is also expert at arranging his figurines against shadowy and suggestive backdrops: post-fascist Japan, in “A Pale View of Hills” (1982) and “An Artist of the Floating World” (1986); an unidentified Central European town undergoing an indeterminate cultural crisis, in “The Unconsoled” (1995); Shanghai at the time of the Sino-Japanese War, in “When We Were Orphans” (2000). It seems important to an understanding of “The Remains of the Day” that the man for whom Stevens once worked, Lord Darlington, was a Fascist sympathizer. But it is not particularly important to Stevens, who has no political wisdom, and who is, in any case, preoccupied with enforcing his own regimen of emotional repression.

The shadowy backdrop in “Never Let Me Go” is genetic engineering and associated technologies. Kathy tells her story in (the novel says) “England, late 1990s,” so the book seems to belong to the same genre as Philip Roth’s “The Plot Against America,” counterfactual historical fiction. Conditions in this brave-new-world Britain, and exactly how Kathy and her friends fit into them, are all spooky authorial surprises, and (as is the case with most things) when you’re reading the novel it is best to begin without too many prior assumptions. Kathy is a “carer”; her patients give “donations,” occasionally as many as four. Inch by inch, the curtain is lifted, and we see what these terms mean and why the world is this way. The strangeness, like the strangeness in Ishiguro’s most imaginative novel, “The Unconsoled,” is ingeniously evoked—by means of literal-minded accounts of things that don’t quite add up—and teasing out the hidden story is the main pleasure of the book. In “The Unconsoled,” the story is never fully sorted out; at the end, we remain in the hall of mirrors. Unfortunately, “Never Let Me Go” includes a carefully staged revelation scene, in which everything is, somewhat portentously, explained. It’s a little Hollywood, and the elucidation is purchased at too high a price. The scene pushes the novel over into science fiction, and this is not, at heart, where it seems to want to be.

But where the novel does want to be is even less obvious than usual. Ishiguro is praised for his precision and his psychological acuity, and is compared to writers like Henry James and Jane Austen. In fact, he says that he dislikes James and Austen. He also says that he has never been able to get beyond the first volume of Proust; it’s too dull. On the other hand, although his novels are self-consciously “set,” they are not historical novels, and the facts don’t seem to interest him very much. Ishiguro was born in Japan, but his parents moved to England with him when he was five. He cannot speak Japanese very well; he has not expressed any particular admiration for Japan or its culture; and he set his first two novels in Japan without revisiting the country. He appears to have done some research for “When We Were Orphans”; but in “Never Let Me Go,” even after the secrets have been revealed, there are still a lot of holes in the story. This is not because things are meant to be opaque; it’s because, apparently, genetic science isn’t what the book is about.

Ishiguro does not write like a realist. He writes like someone impersonating a realist, and this is one reason for the peculiar fascination of his books. He is actually a fabulist and an ironist, and the writers he most resembles, under the genteel mask, are Kafka and Beckett. This is why the prose is always slightly overspecific. It’s realism from an instruction manual: literal, thorough, determined to leave nothing out. But it has a vaguely irreal effect.

Beckett’s subject, too, was happiness, and, though Ishiguro’s characters seem so earnestly respectable, they have the same mad, compulsive, quasi-mechanical qualities that Beckett’s do. There is something animatronic about them. They are simulators of humanness, figures engineered to pass as “real.” What it means to be really human is always a problem for them. Can you just copy other people? Would that take care of it? “I have of course already devoted much time to developing my bantering skills,” Stevens explains at the end of “The Remains of the Day,” “but it is possible I have never previously approached the task with the commitment I might have done.” Genetic engineering—the idea of human beings as products programmed to pick up “personhood skills”—is a perfect vehicle for a writer like Ishiguro.

For reasons that belong to the story’s secret, the characters in “Never Let Me Go” all feel obliged to create works of art. Tommy is slower to develop creatively than his schoolmates, and when he starts to make drawings they are pictures of animals. He finally shows them to Kathy:

I was taken aback at how densely detailed each one was. In fact, it took a moment to see they were animals at all. The first impression was like one you’d get if you took the back off a radio set: tiny canals, weaving tendons, miniature screws and wheels were all drawn with obsessive precision, and only when you held the page away could you see it was some kind of armadillo, say, or a bird. . . . For all their busy, metallic features, there was something sweet, even vulnerable about each of them.

The passage almost certainly derives from Henri Bergson’s famous definition of comedy: the mechanical encrusted on the living. The creatures Tommy draws are imagined versions of himself. They are funny and pathetic at the same time, because people behaving like wind-up toys, even when they can’t help it, even when it makes them fall down manholes, make us laugh. This is why Beckett is a comic writer, and it’s why Ishiguro’s novels, though filled with incidents of poignancy and disappointment and cruelty, are also, weirdly, funny. His sad characters can’t help themselves. ♦

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By David Remnick

By Rebecca Mead

By Amanda Petrusich

By Jason Adam Katzenstein

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Never Let me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro - review

‘this book is full of such compassion for humanity’

This is a sad, complex, haunting novel which raises huge questions about family, memory, exploitation and ‘othering’. At its heart, however, is the simple story of a girl growing up to become a woman, and her relationship with her best friend and eventual lover. Like The Buried Giant, the clarity and poignancy of the way these relationships are portrayed is arrestingly powerful, and lingers unsettlingly in your mind. I was driving along not long after finishing this book when a song lyric invoked the novel, and I felt a sudden, unexpected, almost physical stab of pathos for Cath, Tommy, and Ruth.

The story is split into three parts: one describes the characters growing up in a country boarding house called Hailsham; one recalls the time they spent at the Cottages; the last third is about their splitting up and final coming back together, as adults. I was reminded of the way the goddess of magic, Hecate, is sometimes pictured as having three aspects: a youthful maiden in the morning, a matron at midday, a withered, ancient crone in the evening. This echoes the loss of innocence Cath undergoes in the story, although she is also sympathetic precisely because her destiny in this nightmarish, dystopian world precludes the possibility of becoming a mother or growing old naturally. Kazuo Ishiguro also draws on ideas of rebirth which challenge this simplistic structure.

Another subtle and interesting feature is that the ‘Cottages’, though the shortest section of the book, and in one sense merely a transition or buffer stage, do represent something separate from both just Hailsham and being a ‘Carer’, just as true adolescence is not just a souped-up childhood or undeveloped maturity…

Many aspects of the story will be convincing for anyone: the casual, unthinking cruelty of children in the playground; the fleeting way alliances are made and abruptly severed between young people; how sex changes dramatically as a topic several times in our lives. One of Ishiguro’s strengths as a writer is his ability to write clearly and unpretentiously about these.

The novel is frightening and disturbing at many levels – Kazuo Ishiguro continuously drip-feeds the reader small details which are cause for disquiet (although events or characters with particularly sinister significance are often introduced innocuously). This technique works like introducing sinister music in a film a little before the moment of horror. For this reason, like the characters themselves, the reader always has a creeping realisation of what is really going on, sometimes long before the story really catches up – Cathy’s long, meandering memories, which brilliantly and subtly convey both her stream of consciousness and the random association of ideas (you get the sense constantly that she is trying to impose meaning, a pattern, a narrative, onto fragments of recollection) both contextualise things for the reader and serve as titbits to delay reveals or to throw the reader of the scent. They also strangely seem to mirror the processing of writing a novel itself, in a similar way to how some of Simon Armitage’s poems reflect the process of writing poetry. Perhaps the most sinister aspect of the novel is the way it reflects ourselves back at us. In this world, the cost of a world free from cancer and diseases is, in human terms, catastrophic, but, as one character asks, how can we go back to a world where these diseases cause so much suffering and indignity? In the same way, our trade off for the luxury of development and the necessity of ending poverty seems to be locking us into a cycle of dependency on fossil fuels. Let alone the thought of where our cheap clothes, technology – and the raw materials which build them – come from. I’ve never quite encountered such a well-written fictional account of cognitive bias – the way we modify our beliefs or our behaviour to avert the guilt or discomfort at holding two self-contradictory beliefs in our mind at once – at society’s level. This alone makes this a precious book indeed. The spike in anti-migrant and anti-Muslim hate crime in a post-Brexit Britain, not to mention the rise of Donald Trump in the US or the far right in Europe, has been a salutary reminder of the need to always avoid ‘othering’ human beings; this book is full of such compassion for humanity it must surely be a worthy antidote. The idea of letting the technological or medical genie out of the bottle without considering the full moral, social and environmental implications is as relevant and haunting today as it has ever been.

- Buy this book at the Guardian Bookshop

- Children's books

- Children and teenagers

- Dystopian fiction (children and teens)

- Kazuo Ishiguro

- children's user reviews

Most viewed

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

NEVER LET ME GO

by Kazuo Ishiguro ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 11, 2005

A masterpiece of craftsmanship that offers an unparalleled emotional experience. Send a copy to the Swedish Academy.

An ambitious scientific experiment wreaks horrendous toll in the Booker-winning British author’s disturbingly eloquent sixth novel (after When We Were Orphans , 2000).

Ishiguro’s narrator, identified only as Kath(y) H., speaks to us as a 31-year-old social worker of sorts, who’s completing her tenure as a “carer,” prior to becoming herself one of the “donors” whom she visits at various “recovery centers.” The setting is “England, late 1990s”—more than two decades after Kath was raised at a rural private school (Hailsham) whose students, all children of unspecified parentage, were sheltered, encouraged to develop their intellectual and especially artistic capabilities, and groomed to become donors. Visions of Brave New World and 1984 arise as Kath recalls in gradually and increasingly harrowing detail her friendships with fellow students Ruth and Tommy (the latter a sweet, though distractible boy prone to irrational temper tantrums), their “graduation” from Hailsham and years of comparative independence at a remote halfway house (the Cottages), the painful outcome of Ruth’s breakup with Tommy (whom Kath also loves), and the discovery the adult Kath and Tommy make when (while seeking a “deferral” from carer or donor status) they seek out Hailsham’s chastened “guardians” and receive confirmation of the limits long since placed on them. With perfect pacing and infinite subtlety, Ishiguro reveals exactly as much as we need to know about how efforts to regulate the future through genetic engineering create, control, then emotionlessly destroy very real, very human lives—without ever showing us the faces of the culpable, who have “tried to convince themselves. . . . That you were less than human, so it didn’t matter.” That this stunningly brilliant fiction echoes Caryl Churchill’s superb play A Number and Margaret Atwood’s celebrated dystopian novels in no way diminishes its originality and power.

Pub Date: April 11, 2005

ISBN: 1-4000-4339-5

Page Count: 304

Publisher: Knopf

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 1, 2005

LITERARY FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by Kazuo Ishiguro

BOOK REVIEW

by Kazuo Ishiguro ; illustrated by Bianca Bagnarelli

by Kazuo Ishiguro

More About This Book

BOOK TO SCREEN

HOUSE OF LEAVES

by Mark Z. Danielewski ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 6, 2000

The story's very ambiguity steadily feeds its mysteriousness and power, and Danielewski's mastery of postmodernist and...

An amazingly intricate and ambitious first novel - ten years in the making - that puts an engrossing new spin on the traditional haunted-house tale.

Texts within texts, preceded by intriguing introductory material and followed by 150 pages of appendices and related "documents" and photographs, tell the story of a mysterious old house in a Virginia suburb inhabited by esteemed photographer-filmmaker Will Navidson, his companion Karen Green (an ex-fashion model), and their young children Daisy and Chad. The record of their experiences therein is preserved in Will's film The Davidson Record - which is the subject of an unpublished manuscript left behind by a (possibly insane) old man, Frank Zampano - which falls into the possession of Johnny Truant, a drifter who has survived an abusive childhood and the perverse possessiveness of his mad mother (who is institutionalized). As Johnny reads Zampano's manuscript, he adds his own (autobiographical) annotations to the scholarly ones that already adorn and clutter the text (a trick perhaps influenced by David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest ) - and begins experiencing panic attacks and episodes of disorientation that echo with ominous precision the content of Davidson's film (their house's interior proves, "impossibly," to be larger than its exterior; previously unnoticed doors and corridors extend inward inexplicably, and swallow up or traumatize all who dare to "explore" their recesses). Danielewski skillfully manipulates the reader's expectations and fears, employing ingeniously skewed typography, and throwing out hints that the house's apparent malevolence may be related to the history of the Jamestown colony, or to Davidson's Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of a dying Vietnamese child stalked by a waiting vulture. Or, as "some critics [have suggested,] the house's mutations reflect the psychology of anyone who enters it."

Pub Date: March 6, 2000

ISBN: 0-375-70376-4

Page Count: 704

Publisher: Pantheon

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 2000

More by Mark Z. Danielewski

by Mark Z. Danielewski

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2018

New York Times Bestseller

Pulitzer Prize Finalist

THERE THERE

by Tommy Orange ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 5, 2018

In this vivid and moving book, Orange articulates the challenges and complexities not only of Native Americans, but also of...

Orange’s debut novel offers a kaleidoscopic look at Native American life in Oakland, California, through the experiences and perspectives of 12 characters.

An aspiring documentary filmmaker, a young man who has taught himself traditional dance by watching YouTube, another lost in the bulk of his enormous body—these are just a few of the point-of-view characters in this astonishingly wide-ranging book, which culminates with an event called the Big Oakland Powwow. Orange, who grew up in the East Bay and is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, knows the territory, but this is no work of social anthropology; rather, it is a deep dive into the fractured diaspora of a community that remains, in many ways, invisible to many outside of it. “We made powwows because we needed a place to be together,” he writes. “Something intertribal, something old, something to make us money, something we could work toward, for our jewelry, our songs, our dances, our drum.” The plot of the book is almost impossible to encapsulate, but that’s part of its power. At the same time, the narrative moves forward with propulsive force. The stakes are high: For Jacquie Red Feather, on her way to meet her three grandsons for the first time, there is nothing as conditional as sobriety: “She was sober again,” Orange tells us, “and ten days is the same as a year when you want to drink all the time.” For Daniel Gonzales, creating plastic guns on a 3-D printer, the only lifeline is his dead brother, Manny, to whom he writes at a ghostly Gmail account. In its portrayal of so-called “Urban Indians,” the novel recalls David Treuer’s The Hiawatha , but the range, the vision, is all its own. What Orange is saying is that, like all people, Native Americans don’t share a single identity; theirs is a multifaceted landscape, made more so by the sins, the weight, of history. That some of these sins belong to the characters alone should go without saying, a point Orange makes explicit in the novel’s stunning, brutal denouement. “People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them,” James Baldwin wrote in a line Orange borrows as an epigraph to one of the book’s sections; this is the inescapable fate of every individual here.

Pub Date: June 5, 2018

ISBN: 978-0-525-52037-5

Review Posted Online: March 19, 2018

Kirkus Reviews Issue: April 1, 2018

More by Tommy Orange

by Tommy Orange

PERSPECTIVES

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Authors & Events

Recommendations

- New & Noteworthy

- Bestsellers

- Popular Series

- The Must-Read Books of 2023

- Popular Books in Spanish

- Coming Soon

- Literary Fiction

- Mystery & Thriller

- Science Fiction

- Spanish Language Fiction

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Spanish Language Nonfiction

- Dark Star Trilogy

- Ramses the Damned

- Penguin Classics

- Award Winners

- The Parenting Book Guide

- Books to Read Before Bed

- Books for Middle Graders

- Trending Series

- Magic Tree House

- The Last Kids on Earth

- Planet Omar

- Beloved Characters

- The World of Eric Carle

- Llama Llama

- Junie B. Jones

- Peter Rabbit

- Board Books

- Picture Books

- Guided Reading Levels

- Middle Grade

- Activity Books

- Trending This Week

- Top Must-Read Romances

- Page-Turning Series To Start Now

- Books to Cope With Anxiety

- Short Reads

- Anti-Racist Resources

- Staff Picks

- Memoir & Fiction

- Features & Interviews

- Emma Brodie Interview

- James Ellroy Interview

- Nicola Yoon Interview

- Qian Julie Wang Interview

- Deepak Chopra Essay

- How Can I Get Published?

- For Book Clubs

- Reese's Book Club

- Oprah’s Book Club

- happy place " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: Happy Place

- the last white man " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: The Last White Man

- Authors & Events >

- Our Authors

- Michelle Obama

- Zadie Smith

- Emily Henry

- Amor Towles

- Colson Whitehead

- In Their Own Words

- Qian Julie Wang

- Patrick Radden Keefe

- Phoebe Robinson

- Emma Brodie

- Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Laura Hankin

- Recommendations >

- 21 Books To Help You Learn Something New

- The Books That Inspired "Saltburn"

- Insightful Therapy Books To Read This Year

- Historical Fiction With Female Protagonists

- Best Thrillers of All Time

- Manga and Graphic Novels

- happy place " data-category="recommendations" data-location="header">Start Reading Happy Place

- How to Make Reading a Habit with James Clear

- Why Reading Is Good for Your Health

- 10 Facts About Taylor Swift

- New Releases

- Memoirs Read by the Author

- Our Most Soothing Narrators

- Press Play for Inspiration

- Audiobooks You Just Can't Pause

- Listen With the Whole Family

Look Inside | Reading Guide

Reading Guide

Never Let Me Go

By kazuo ishiguro, by kazuo ishiguro read by rosalyn landor, part of vintage international, category: science fiction | literary fiction, category: literary fiction | science fiction | audiobooks.

Mar 14, 2006 | ISBN 9781400078776 | 5-3/16 x 8 --> | ISBN 9781400078776 --> Buy

Apr 05, 2005 | ISBN 9781400044832 | 5-5/8 x 8-3/8 --> | ISBN 9781400044832 --> Buy

Apr 12, 2005 | 581 Minutes | ISBN 9780739317990 --> Buy

Buy from Other Retailers:

Mar 14, 2006 | ISBN 9781400078776

Apr 05, 2005 | ISBN 9781400044832

Apr 12, 2005 | ISBN 9780739317990

581 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

- audiobooks.com

About Never Let Me Go

NOBEL PRIZE WINNER • From the acclaimed, bestselling author of The Remains of the Day comes “a Gothic tour de force” ( The New York Times ) with an extraordinary twist—a moving, suspenseful, beautifully atmospheric modern classic. As children, Kathy, Ruth, and Tommy were students at Hailsham, an exclusive boarding school secluded in the English countryside. It was a place of mercurial cliques and mysterious rules where teachers were constantly reminding their charges of how special they were. Now, years later, Kathy is a young woman. Ruth and Tommy have reentered her life. And for the first time she is beginning to look back at their shared past and understand just what it is that makes them special—and how that gift will shape the rest of their time together.

Listen to a sample from Never Let Me Go

Also in vintage international.

Also by Kazuo Ishiguro

About Kazuo Ishiguro

KAZUO ISHIGURO was born in Nagasaki, Japan, in 1954 and moved to Britain at the age of five. His eight previous works of fiction have earned him many honors around the world, including the Nobel Prize in Literature and the… More about Kazuo Ishiguro

Product Details

You may also like.

A Visit from the Goon Squad

Station Eleven (Television Tie-in)

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

The Secret History

The Friend (National Book Award Winner)

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (Pulitzer Prize Winner)

Oryx and Crake

ONE OF THE ATLANTIC’ S 15 BOOKS YOU WON’T REGRET RE-READING “A page turner and a heartbreaker, a tour de force of knotted tension and buried anguish.” — Time “A Gothic tour de force…. A tight, deftly controlled story…. Just as accomplished [as The Remains of the Day ] and, in a very different way, just as melancholy and alarming.” — The New York Times “Elegaic, deceptively lovely…. As always, Ishiguro pulls you under.” — Newsweek “Superbly unsettling, impeccably controlled…. The book’s irresistible power comes from Ishiguro’s matchless ability to expose its dark heart in careful increments.” — Entertainment Weekly

ALA Alex Award WINNER 2006

Margaret A. Edwards Award (Alex Awards) WINNER 2006

Nobel Prize in Literature WINNER 2017

National Book Critics Circle Awards NOMINEE 2005

Booker Prize FINALIST 2005

Review: Never Let Me Go By Kazuo Ishiguro

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

Never Let Me Go

Embed our reviews widget for this book

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

April 10, 2024

- An interview with Nancy Fraser after Cologne University canceled her visiting professorship

- On who is afforded a non-politicized death

- Rafael Frumkin considers literatures of autism and the right to authorship

Kazuo Ishiguro’s ‘Never Let Me Go’ Is a Masterpiece of Racial Metaphor

Books & Culture

His characters may not be asian, but the book is an incisive commentary on nonwhite experience.

In our new dystopian reality, we rarely get to celebrate good news. Waking up to the New York Times alert about Kazuo Ishiguro’s Nobel Prize win was one of the few truly joyous occasions of 2017. Not only because I’ve been a fan of the Japanese-British author since college, but also his recognition on such a global platform reaffirmed a worldview that needs to be remembered now more than ever.

But I was mystified when, amid the jubilant responses to the Nobel Prize committee’s decision to award Ishiguro, some began openly fretting over the author’s commitment to addressing matters of identity. Interestingly, these critiques tended to originate from within the Asian American community. Citing interviews where the author copped to being “self-conscious about this issue of people taking me literally” in reference to his Japan-centered novel, An Artist of the Floating World (1986), readers asked: Why did he stop writing novels with Japanese protagonists? Did he pander too much to the white gaze? Is that why he won — because he made himself palatable to white readers? Writers of color often have to negotiate their identities in ways that white writers do not when publishing in America, where the industry is nearly 80% white , and even more so in the U.K .

Ishiguro’s characters explore aspects of nonwhite identity that are actually more incisive and authentic than if they were simply reflections of Japanese culture.

The push for inclusivity may actually help explain why some readers feel let down by Ishiguro’s choices as a writer. In order to find a work that conforms more closely to what’s expected of Asian diasporic literature, we must reach farther back into the author’s oeuvre — to his debut A Pale View of The Hills (1982), which features an immigrant narrative about a middle-aged Japanese woman living in England. Ironically, such pigeonholing would seem to undermine the endeavor of contemporary writers of color to subvert rigid definitions of what they can and can’t write about. As someone who identifies as such, I reeled at the insinuations that the Japanese-born author was somehow less representative of his ethnicity because he has written about white characters, or characters whose race is never explicitly mentioned. In fact, I would argue just the opposite — that Ishiguro’s characters explore aspects of nonwhite identity that are actually more incisive and authentic than if they were simply reflections of Japanese culture.

Ishiguro’s novels frequently grapple with the role of the individual within the confines of society. Over the years I’ve found myself returning to his 2005 novel Never Let Me Go when contemplating the social conditions that continue to persist in our post-9/11, post-colonial, post-racial, post-everything world. The experience of diving into an Ishiguro novel becomes a process of excavation, of uncovering memories that the narrator has meticulously buried over a lifetime. But don’t expect any big reveal; instead, we must be satisfied with fragments of truth. The author’s gift lies in his ability to use those fragments to construct a portrait, which, in the end, resembles something more of a mirror. That truth implicates us as much as it does the characters in their fictional realm.

Never Let Me Go ’s setting, stated simply as “England, late 1990s,” offers an alternative present where cancer and other previously incurable diseases all have a cure — but at some very high costs. Framed as the memoir of Kathy H., now 31, the narrative opens with recollections of her childhood growing up at an idyllic boarding school Hailsham in the English countryside. The narrative paints Hailsham and its remote, pastoral setting as one of a handful of “privileged estates.” Insulated from the outside, the school cultivates a unique culture, where the students’ guardians place a heavy emphasis on the need for creativity over the learning of rote subjects. In this way, we can think of Hailsham as representative of the high culture frequently associated with novels about exclusive educational institutions.

For those fortunate enough to gain admittance into these predominantly white spaces, they must often convince themselves that the bargain is worth it — that to follow the path of assimilation is better than to suggest rebellion. This rings especially true for people of color, who historically have been the ones excluded. The promise of belonging to an elite group proves so intoxicating that the students fail to discern to whom exactly they pledge their loyalty, and at what price. Only later do we the reader understand the types of roles Kathy and her peers are being groomed for.

It is this turn in the novel that begins to undo our perception of the students’ special standing. As the story unravels, we see that the walls of Hailsham do not act so much as fortification against intruders as they do a means of incarceration. The guardians employ psychological tactics in order to quell the curiosity of the students and discourage them from physically escaping. So in spite of the institution’s initial acclaim, Hailsham seems more and more a fraud where the imposition of order upon the student body supersedes the intellectual cultivation of the individual student.

In this brave new world, the technology of human cloning is implemented on a full scale for the harvesting of vital organs. The novel considers the ramifications of treating life as resource. More importantly, it forces us to reevaluate the comparison between the life of the human and nonhuman. But even this classification remains in constant flux. Identity, it seems, is never stable — a belief that’s rooted in the core of Never Let Me Go ’s coming-of-age story.

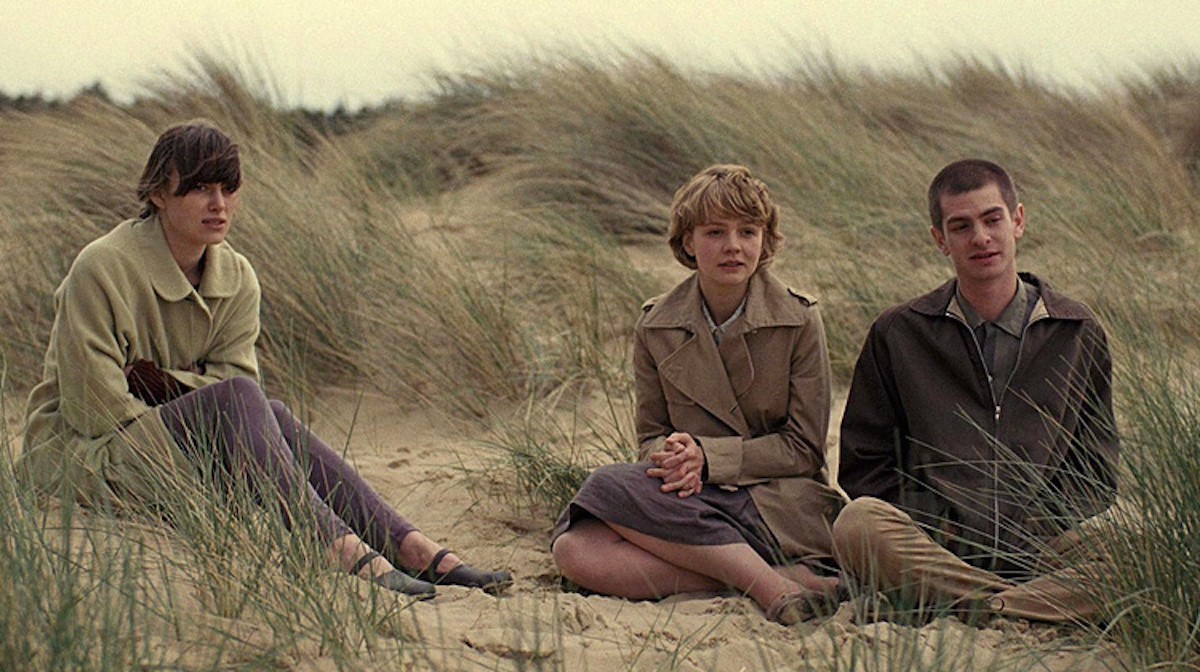

Because we are never told what race Kathy and her classmates are in Never Let Me Go , I have a hunch that most readers assumed by default they were white. Certainly, this is what the 2010 film adaptation envisioned with its casting of comparably pale and willowy actors, all of whom could be described as very typically “English” in appearance. But it’s entirely possible to read these characters as non-white. Reduced to their mere expendable parts, Kathy and her fellow students represent those marginalized figures of our collective unconscious. Their embodiment of the unspeakable may even be biologically encoded onto their selves. Kathy’s friend Ruth theorizes: “We’re modeled from trash . Junkies, prostitutes, winos, tramps. Convicts, maybe, just so long as they aren’t psychos. That’s what we come from.” Because ethnic minorities are more likely to live in poverty compared to white people in the UK , the source population for these clones would have almost certainly included people of color. And given the very real history of how Western medicine has exploited black bodies specifically , there’s a strong case to be made for Ishiguro’s characters being non-white both figuratively and literally.

From science fiction to reality, the business of organ trafficking has materialized quite literally in non-white countries like China, India, Egypt, and Pakistan. Transplant tourism is a real thing, and its combined ethical dubiousness and questionable legality raise concerns about the commodification of human bodies. Pope Francis called organ trafficking one of the “new forms of slavery,” alongside forced labor and prostitution. For other modern-day metaphors for enslavement, look no further than commercial surrogacy or the indentured servitude sanctioned by our immigration laws. Never Let Me Go transforms the approach to racial subjugation in the name of scientific progress, which has created an entire sub-race of clones to service the needs of the greater whole of society. Just as notions of racial hierarchy have been used to promulgate colonial systems throughout history, the perceived nonhuman status of the clones seemingly justifies their sacrifice. The novel reframes the history of imperialism as a conflict between those considered human and those who are not.

The novel reframes the history of imperialism as a conflict between those considered human and those who are not.

The question of humanness troubles the clones, as well as sympathetic individuals like the guardians. On Hailsham’s mission, one of the guardians Miss Emily proclaims, “Most importantly, we demonstrated to the world that if students were reared in humane, cultivated environments, it was possible for them to grow to be as sensitive and intelligent as any ordinary human being.” The liberal-minded guardians invested in the students’ cultural education not only with the aim of improving their quality of living, but also to establish that their lives were worth saving. Working against the rationalization of science, the guardians looked to the students’ creativity as the truer measure of their being human. “We took away your art because we thought it would reveal your souls,” Miss Emily informs Kathy, then amending, “Or to put it more finely, we did it to prove you had souls at all .” The insinuation that she could be without a soul does not so much upset Kathy as it confuses her. She remembers a similar incident in her childhood when it occurs to her that an adult might be afraid of who she is:

So you’re waiting, even if you don’t quite know it, waiting for the moment when you realize that you really are different to them; that there are people out there, like Madame, who don’t hate you or wish you any harm but who nevertheless shudder at the very thought of you — of how you were brought into this world and why — and who dread the idea of your hand brushing against theirs. The first time you glimpse yourself through the eyes of a person like that, it’s a cold moment. It’s like walking past a mirror you’ve walked past every day of your life, and suddenly it shows you something else, something troubling and strange.

These moments of questioning threaten Kathy’s sense of self. Yet for readers familiar with life in the margins, they merely confirm her humanity.

As highlighted by the value placed on the clones’ artwork, the validity of one’s humanity hinges primarily upon the expression of emotion and the ability of others to read those emotions. This problem of readability extends to the author himself. When Josephine Livingston asks in The New Republic “What’s So ‘Inscrutable’ About Kazuo Ishiguro?” she’s being rhetorical, knowing full well that “inscrutability” is a longstanding Orientalist trope used to dehumanize Asian figures. She quotes Ishiguro’s own words:

Books, articles and television programmes focus on whatever is most extreme and bizarre in Japanese life; the Japanese people may be viewed as amusing or alarming, expert or devious, but they must above all be seen to be non-human. While they remain non-human, their values and ways will remain safely irrelevant. No wonder the British are so fond of the ‘inscrutability’ of Japanese faces.

Ishiguro’s insight into how his own ethnic exterior may be perceived suggests that he is in fact portraying the clones’ struggle through a racial lens. The correlation between the failure of the British to see Japanese people as human and the failure of critics to interpret Ishiguro’s work appears inextricable. In the essay “The ‘Inscrutable’ Voices of Asian-Anglophone Fiction,” The New Yorker contributor Jane Hu goes one step further to establish how Ishiguro’s affinity for “first-person narrators who keep their distance — actively denying readers direct interior access” provides an aesthetic quality indicative of inherent “Asian-ness.” By leaning into the “inscrutable Oriental” stereotype, Asian-Anglophone novelists, such as Chang-rae Lee, Ed Park, and Weike Wang, consciously play with the prejudices of Western readers.

To say that Ishiguro’s writing eschews identity politics would be a failed reading of those works.

To say that Ishiguro’s writing eschews identity politics — an implication that his most popular novels, Never Let Me Go among them, are somehow safer and therefore less racially transgressive — would be a failed reading of those works. Perhaps his stories resist categorization precisely because they so urgently demand to be read universally. “[F]or me the essential thing is that [stories] communicate feelings,” the author said in his recent Nobel Lecture . He made the appeal that “we must become more diverse,” with the understanding that to “widen our common literary world to include many more voices from beyond our comfort zones of the elite first world cultures” means broadening whose stories help define what it means to be human. Boiled down to their essence, his characters beg simply to be seen, to be understood. Reading Ishiguro, I feel both.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.

ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER ADVERTISEMENT

9 Political Books To Read After ‘Fire and Fury‘

If Michael Wolff’s Trump administration exposé has whetted your appetite, here’s what to pick up next

Jan 9 - Tobias Carroll Read

More like this.

I Rewrite My American Story in “Everything Everywhere All at Once”

Part 3 of Brian Lin’s essay on the portrayal of complex Asian American racial dynamics in the record-breaking box office hit

Aug 11 - Brian Lin

DON’T MISS OUT

Sign up for our newsletter to get submission announcements and stay on top of our best work.

- Literature & Fiction

- Contemporary

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Never Let Me Go Audio CD – Unabridged, April 12, 2005

- Print length 9 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Random House Audio

- Publication date April 12, 2005

- Dimensions 5.08 x 1.1 x 5.91 inches

- ISBN-10 0739317989

- ISBN-13 978-0739317983

- See all details

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

Product details.

- Publisher : Random House Audio; Unabridged edition (April 12, 2005)

- Language : English

- Audio CD : 9 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0739317989

- ISBN-13 : 978-0739317983

- Item Weight : 8.8 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.08 x 1.1 x 5.91 inches

- #1,152 in Books on CD

- #4,699 in Contemporary Literature & Fiction

- #23,976 in Literary Fiction (Books)

About the author

Kazuo ishiguro.

KAZUO ISHIGURO was born in Nagasaki, Japan, in 1954 and moved to Britain at the age of five. His eight previous works of fiction have earned him many honors around the world, including the Nobel Prize in Literature and the Booker Prize. His work has been translated into over fifty languages, and The Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go, both made into acclaimed films, have each sold more than 2 million copies. He was given a knighthood in 2018 for Services to Literature. He also holds the decorations of Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from France and the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star from Japan.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Ishiguro's 'Never Let Me Go'

Maureen Corrigan

Book critic Maureen Corrigan reviews Never Let Me Go , the new novel by Kazu Ishiguro, the author of the bestseller The Remains of the Day .

Email Address

Most Popular

- The Thirty-Nine Steps: Book Review

- Spy Novel Plots - Four Great Spy Story Ideas

- How to Become a Spy

- Writing a Killer Logline

- She by H Rider Haggard: Book Review

- Rogue Male - Book Review

- Writing Spy Fiction with an Unputdownable Plot

- Our Man in Havana: Book Review

- Intelligence Agency Mottoes

- Logline Examples

Never Let Me Go: Book Review

Never Let Me Go, written by Kazuo Ishiguro and published in 1992, is one of the greatest alternative history novels ever written. It’s the only alternative history novel ever shortlisted for the Booker Prize and it won many other literary awards.

Never Let Me Go: Title

The title is an allusion to a music album entitled Never Let Me Go by a fictional singer, Judy Bridgewater. The novel’s protagonist loves the album, and her listening to it is a motif that recurs throughout the novel. Using a defining motif in the title is a classic title archetype.

(For more on titles, see How to Choose a Title For Your Novel )

Never Let Me Go: Logline

Three friends, brought up understanding that they will donate their organs and die at a young age, try to find some meaning in their brief lives.

(For more on loglines see The Killogator Logline Formula )

Never Let Me Go: Plot Summary

Warning: My plot summaries contain spoilers. Major spoilers are blacked out like this [blackout]secret[/blackout]. To view them, just select/highlight them.

It’s the late 1990s, in England. Kathy, a carer who looks after ‘donors’ who, it seems, do not survive their donations, reminisces about her time at Hailsham, a boarding school.

Kathy’s two best friends at Hailsham are Ruth and Tommy. Kathy recounts several events from their schooldays, which seem idyllic – learning and playing like any boarding-school children. However, throughout their time at Hailsham, the children know they’re not normal and will eventually become ‘donors’.

A headmistress, known as ‘Miss Emily’, runs the school. The teachers, known as guardians, teach a normal curriculum but with an emphasis on art and keeping healthy. The students exhibit their art, and a woman known as ‘Madame’ takes away the best pieces.

One guardian becomes upset at the students’ vague understanding of their fate. She says the school has brought them up aware of ‘donations’, but without really comprehending the implications. She attempts to explain, but the children still don’t really understand. The guardian leaves the school shortly afterwards.

The Cottages

When they’re sixteen, Kathy, Ruth and Tommy go to a half-way-house called ‘The Cottages’.

Ruth and Tommy started a romantic relationship during their last year at the school and continue it at the Cottages, but Kathy never forms a long-term relationship with anyone.

Two of the older students tell Ruth that they saw a woman who could be her ‘original’ working in an office (thus confirming that the ‘donors’ are clones). They all decide to investigate. During the trip, the two older students say that they’ve heard a rumour that couples from Hailsham can have their donations deferred if they can prove they’re genuinely in a romantic relationship. Kathy, Ruth and Tommy have never heard this rumour.

Tommy and Kathy go off together and find a copy of Kathy’s favourite music tape, which she last had at Hailsham. Tommy also tells Kathy that he suspects rumours about deferments are true and that he believes that Madame uses the art collection to decide if people can have deferments.

Back at the Cottages, Ruth becomes jealous of Tommy and Kathy’s close friendship and starts antagonising Kathy. Hurt by Ruth’s behaviour, Kathy applies to become a carer and moves away from the Cottages.

Kathy becomes a carer and doesn’t see either Ruth or Tommy for many years. During the intervening period, Hailsham closes.

When she hears that Ruth’s donations have started, and that her health is deteriorating fast, Kathy becomes her carer. Some donors manage up to four donations, but Ruth is not strong enough for that, and both Ruth and Kathy suspect Ruth’s second donation will lead to her death.

Ruth wants to meet up with Tommy, who’s in a different donor centre. Kathy arranges a car trip. At first, Kathy and Tommy gang up on Ruth, remembering the thoughtless things she’s done to them both. Ruth, though, is regretful and tells Kathy and Tommy they should get together for whatever time they have left. Also, she has discovered where Madame lives. It’s too late for her, but she urges Kathy and Tommy to ask Madame for one of the rumoured deferrals…

Soon after, [blackout]Ruth makes her second donation and dies. Kathy becomes Tommy’s carer and they become romantically involved. Following Ruth’s wishes, they track Madame down and ask for a deferral.[/blackout]

They discover [blackout]that Madame lives with Miss Emily. The two women tell Kathy and Tommy that there is no such thing as a deferral – the rumour was just wishful thinking by the donors.[/blackout]

In reality, [blackout]Hailsham was part of a failed attempt to show that the donors were being abused. Madame exhibited the gallery of artwork around the country, trying to convince the public that donors were as human as everyone else.[/blackout]

Madame and Miss Emily [blackout] both say they’re sorry, but there’s nothing they can do. Kathy seems to accept this, but Tommy is horrified.[/blackout]

Tommy [blackout]asks Kathy not to be his carer for his final donation as he doesn’t want her to see him die. They part, with Kathy knowing her own donations and death are imminent.[/blackout]

(For more on summarising stories, see How to Write a Novel Synopsis )

Never Let Me Go: Analysis

Warning: inevitably my analysis contains spoilers.

The Alternate History of Never Let Me Go

Never let Me Go is not an alternative history novel in the way most of the novels I review are. There’s no specifically stated point of departure, but it would seem that in the 1950s scientists perfected human cloning and the public waved away ethical concerns. In the 1970s, the small group that ran Hailsham tried to raise the ethical issues but were unsuccessful. Apart from that, the world doesn’t seem to have changed.

This lack of consequences makes the world of Never Let Me Go more of a fantasy world than an alternate history (see What is Alternative History? )

Never let Me Go is not a fast-paced or plot-driven novel. However, Ishiguro uses hinting of problems to come and mild cliffhangers to keep the story interesting and page-turning – it’s not a slow read.

More Questions than Answers

There is no proper explanation for many points.

- Although ‘Madame’ explains this at the end to an extent. Hailsham was part of a failed campaign to show that the donors were fully human and so deserved human rights. Many other donors were raised in inhumane conditions.

- Presumably, the guardians thought they were helping the human rights campaign or making the donors’ lives less awful.

- Ishiguro hand-waves this. Supposedly, society decided the medical benefits were more important than the human rights abuses.

- That the church, in particular, would go along with this seems inconceivable.

- See discussion below.

- Does the fact that the donors will die mean their lives are pointless?

The lack of explanation makes you think about the issues, and that’s the point. The thing is, Never Let Me Go isn’t really about rational stuff. It’s not about making perfect sense in the real world. In the end, it’s a gigantic extended metaphor.

The children’s lives are a metaphor for all human life. We all know we’re going to die, but still we go through our lives either not thinking about it, telling ourselves stories about how we can avoid it, or in flat out denial.

When mortality forces us to recognise death, such as when a loved one dies, we react with horror, but swiftly move on, cloaking the unpleasantness with euphemism (“passed away”, for example).

Understated

Kathy narrates the entire novel in the past tense. She’s an unreliable narrator because of her own lack of awareness of the horror of the story. When she talks about the clones’ sad lives in a matter of fact, accepting way, it provokes an emotional response in the reader.

Throughout the story, Kathy and the others seem to just accept their fate. Apart from attempting to seek a ‘deferral’, they don’t try to escape, rebel or protest. They don’t even consider suicide. Ruth is the only one who has any thoughts of doing anything other than becoming a carer and then a donor. She dreams of working in an office like a normal person, although even she realises it’s just a fantasy.

The ‘out of universe’ reason no one tries to run away is that the novel is, as explained above, a metaphor for human life. There’s no ‘running away’ from the fact that we’re all going to die one day. Ask yourself why you accept your fate and you understand why the characters do the same. Where is there to run to?

However, there’s no canonical ‘in universe’ explanation for why the donors accept their fate so passively. However, it’s hinted that they’re tracked and monitored, e.g. they use tags to sign in at the cottages. And of course there may be nowhere to run to, as the same system is likely to be in place anywhere else they could go to.

Another possibility is that society regards the donors as pariahs outside normal society. It may be impossible for donors to get a normal job or housing, legally or due to prejudice. It’s suggested in several scenes in the book that people are scared of and repulsed by the donors. That leaves them with very few options.

Ishiguro himself has said that the donors simply don’t have any concept of ‘running away’ even being a possibility. He’s also said that the entire question of ‘Why don’t they run away?’ only comes up with western audiences.

In the end, the ‘in universe’ explanations are not fully explored, as the author’s purpose is metaphorical.

Reality: Human Cloning Clones have existed throughout history as twins are genetically identical, naturally occurring clones. However, the first artificially cloned animals were born in the 1990s, raising the possibility of artificial human cloning in the future. The ethical issues around the sanctity of life and human rights quickly led to bans on reproductive human cloning worldwide. As reproductive human cloning is illegal, and the use of clones as a supply of organs for transplantation is utterly unethical and against any conception of human rights, ‘harvesting’ of clones is unlikely ever to take place. However, scientists are researching therapeutic cloning of human cells, and lab-grown organs are a possibility for future medicine.

The movie The Island, starring Scarlett Johansson and Ewan McGregor, has the same basic premise as Never Let Me Go , but takes it in a very different, action-orientated-thriller, direction.

In Never let Me Go the protagonists are aware of their fate and, largely, accept it, while in The Island the clones are in what amounts to a prison and the prison authorities tell them that the world outside is a wasteland . Discovering the truth about what’s really happening, the protagonists attempt to escape. The Hollywood approach of The Island is in stark contrast to the contemplative nature of Never Let Me Go.

Never Let Me Go: My Verdict

Probably the best written alternative history novel ever. Hauntingly beautiful.

Never Let Me Go: The Movie

An adaptation of Never Let Me Go , staring Keira Knightley , Carey Mulligan and Andrew Garfield, was released in 2010. It’s a good adaptation, sticking closely to the plot of the novel. It’s worth watching, but to me it’s nowhere near as good as the book.

Want to Read It?

The Never Let Me Go novel is available on UK Amazon here and US Amazon here .

The Never Let Me Go movie is available on UK Amazon here and US Amazon here .

Agree? Disagree?

If you’d like to discuss anything in my Never Let Me Go review, please email me. Otherwise, please feel free to share it using the buttons below.

Related posts:

Advertisement

Supported by

Book Review

Savages innocents sages what do we really know about early humans.

In “The Invention of Prehistory,” the historian Stefanos Geroulanos argues that many of our theories about our remote ancestors tell us more about us than them.

By Jennifer Szalai

Is This Maternity Hospital Haunted, or Is It All a Pregnant Metaphor?

In Clare Beams’s eerie new novel, “The Garden,” nefarious things are afoot.

By Claire Oshetsky

What Happened When Captain Cook Went Crazy

In “The Wide Wide Sea,” Hampton Sides offers a fuller picture of the British explorer’s final voyage to the Pacific islands.

By Doug Bock Clark

Climate Change Is Making Us Paranoid, Anxious and Angry

From dolphins with Alzheimer’s to cranky traffic judges, writes Clayton Page Aldern, the whole planet is going berserk.

By Nathaniel Rich

17 New Books Coming in April

New novels from Emily Henry, Jo Piazza and Rachel Khong; a history of five ballerinas at the Dance Theater of Harlem; Salman Rushdie’s memoir and more.

Let Us Help You Find Your Next Book

Reading picks from Book Review editors, guaranteed to suit any mood.

By The New York Times Books Staff

17 Works of Nonfiction Coming This Spring

Memoirs from Brittney Griner and Salman Rushdie, a look at pioneering Black ballerinas, a new historical account from Erik Larson — and plenty more.

By Cody Delistraty

27 Works of Fiction Coming This Spring

Stories by Amor Towles, a sequel to Colm Toibin’s “Brooklyn,” a new thriller by Tana French and more.

By Kate Dwyer

Best-Seller Lists: April 14, 2024

All the lists: print, e-books, fiction, nonfiction, children’s books and more.

Books of The Times

Delmore Schwartz’s Poems Are Like Salt Flicked on the World

A new omnibus compiles the poet’s books and unpublished work, including his two-part autobiographical masterpiece, “Genesis.”

By Dwight Garner

She Lied, Cheated and Stole. Then She Wrote a Book About It.

In her buzzy memoir, “Sociopath,” Patric Gagne shows herself more committed to revel in her naughtiness than to demystify the condition.

By Alexandra Jacobs

A Gender Theorist Who Just Wants Everyone to Get Along

Judith Butler’s new book, “Who’s Afraid of Gender?,” tries to turn down the heat on an inflamed argument.

A Warhol Superstar, but Never a Star

Cynthia Carr’s compassionate biography chronicles the brief, poignant life of the transgender actress Candy Darling, whose “very existence was radical.”

The Retired Justice Who Doesn’t Understand the Supreme Court

Stephen Breyer means well. Why is his new book, “Reading the Constitution,” so exasperating?

Simon & Schuster Turns 100 With a New Owner and a Sense of Optimism

The milestone comes after a particularly turbulent period, when the publisher was put up for sale and bought by a private equity firm. Since then, investments have boosted morale and helped it grow.

By Alexandra Alter and Elizabeth A. Harris

Comics Artist Dies After Sexual Misconduct Accusations

Ed Piskor, 41, was known for his detailed “Hip Hop Family Tree” and “X-Men: Grand Design.” A Pittsburgh gallery didn’t open an exhibition of his work after the initial allegation.

By Marc Tracy and George Gene Gustines

Heartbreak and Family Love on the International Booker Prize Shortlist

Books by Jenny Erpenbeck and Hwang Sok-yong are among six nominees for the prestigious award for translated fiction.

By Alex Marshall

A Historian Makes Peace With Her Own History

It took Doris Kearns Goodwin a while to adjust to leaving the Concord, Mass., farmhouse she shared with her husband. But Boston has its compensations.

By Joanne Kaufman

A Father and a Daughter, Caught Up in Political Protests

In Jen Silverman’s new novel, “There’s Going to Be Trouble,” two generations of activists wrestle with the errors of the past as they strive to create a more survivable future.

By Angela Lashbrook

Two Women, United by Climate Change and the Man They Both Married

In her far-reaching latest novel, “The Limits,” Nell Freudenberger forges connections between the global and the familial.

By Charles Finch

The Culture Warriors Are Coming for You Smart People

In Lionel Shriver’s new novel, judging intelligence and competence is a form of bigotry.

By Laura Miller

When Tom Ripley Stares Into the Mirror, He Sees Us

In the new series and in five previous movies, the character serves as a blank slate to examine the mores and concerns of the time.

By Alissa Wilkinson

Leigh Bardugo’s Latest Travels to Renaissance Spain

In “The Familiar,” the blockbuster fantasist conjures a world of mystical intrigue and romance.

By Danielle Trussoni

Do You Know These Novels Driven by Climate Change?

Try this short quiz on recent fiction that follows characters dealing with a turbulent world.

By J. D. Biersdorfer

Never Let Me Go review

Blade runner goes to boarding school….

Why you can trust GamesRadar+ Our experts review games, movies and tech over countless hours, so you can choose the best for you. Find out more about our reviews policy.

It’s an adap of a novel by one of Britain’s best authors (Kazuo Ishiguro), stars some of our hottest young talent and deals with themes of no less importance than the human soul. In other words, Never Let Me Go is a present laid expectantly on Bafta’s doorstep. Let’s hope they kept the receipt. You might expect a sci-fi centred on medical ethics to take place in some future dystopia. But Mark Romanek’s (One Hour Photo) film is set in the drizzle of mid-’90s England, dividing its time between overcast seaside, muddy countryside and a peculiar boarding school called Hailsham. There, pupils Kathy (Carey Mulligan) and Ruth (Keira Knightley) become rivals when Ruth poaches the affections of Tommy (Andrew Garfield). As the three grow into adulthood, they learn that a truly in-love couple might defer the grim fate of Hailsham pupils, and competition for Tommy’s heart intensifies. In another Ishiguro adaptation, The Remains Of The Day, Anthony Hopkins revealed the pathos of a man unable to take action to find happiness in his life. Despite boasting three times the inert characters of that film, Never Let Me Go never achieves equivalent impact. The pupils’ failure to question their fate plays more like lethargy than tragically repressed emotion. Scripter Alex Garland does deserve credit for his restraint; a lesser adap would have ignored the novel’s nuance and put Knightley and Mulligan in silver Lycra. Then again, a better one would’ve found a way to transfer the book’s intense feeling to the screen. Instead, Never Let Me Go is moving only in the sense that it’s depressing and, y’know, so are motorway service stations.

The Paranormal Activity studio is reviving the Blair Witch Project with a "new vision" for the horror classic

The vice on the PS4 and Xbox One gets a little tighter as Diablo 4 boss agrees "there's always a time and a place" to drop last-gen

X-Men '97: All the Easter eggs, cameos, and references

Most Popular

By Kate Stables 4 April 2024

By Duncan Robertson 4 April 2024

By Lauren Milici 3 April 2024

By Fraser Porter 2 April 2024

By Alex Berry 2 April 2024

By Jane Crowther 28 March 2024

By Phil Hayton 28 March 2024

By Rachel Watts 27 March 2024

By Molly Edwards 27 March 2024

By Tabitha Baker 26 March 2024

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

general information | review summaries | our review | links | about the author

- Return to top of the page -

A- : well-written, if not entirely convincing

See our review for fuller assessment.

Review Consensus : No consensus, though many are impressed (and even more: confused) by how he goes about it From the Reviews : "Mr Ishiguro (...) writes such taut, emotionless sentences this time that they feel almost contrived; the language adds much to the book's sense of unreality, but also makes it hard to care much about the characters. (...) The most frustrating aspect of the novel, however, is the paradox of Hailsham's students being so expensively educated and taught to think for themselves, yet so fully accepting of their fate. (...) Thought-provoking stuff, certainly, but ultimately the style outweighs the substance." - The Economist "This extraordinary and, in the end, rather frighteningly clever novel isn't about cloning, or being a clone, at all. It's about why we don't explode, why we don't just wake up one day and go sobbing and crying down the street, kicking everything to pieces out of the raw, infuriating, completely personal sense of our lives never having been what they could have been." - M.John Harrison, The Guardian "Ishiguro is primarily a poet. Accuracy of social observation, dialogue and even characterisation is not his aim. In this deceptively sad novel, he simply uses a science-fiction framework to throw light on ordinary human life, the human soul, human sexuality, love, creativity and childhood innocence. He does so with devastating effect" - Andrew Barrow, The Independent "The problem for the reviewer, appropriately enough, is that by revealing more of what the book is about he risks going too far and unravelling its meticulously woven fabric of hints and guesses. So I'll leave it there. Suffice it to say that this very weird book is as intricate, subtly unsettling and moving as any Ishiguro has written." - Geoff Dyer, Independent on Sunday "(T)he texture of the writing becomes altogether less interesting, and this may be a reason why the novel seems to be, though only by the standards Ishiguro has set himself, a failure." - Frank Kermode, London Review of Books "Ishiguro�s world can grab no one by the throat, because it is not real. It would have been more effective, for instance, if we learned that all these characters interacting on the page were cows." - Max Watman, The New Criterion "His attention remains fixed on intimate things - on the small social groupings within a school, on the nuances of personal relationships. The larger world remains a distant, blurred backdrop, and is brought into focus only at the end. What holds our attention before then is the way Ishiguro uses the subject of cloning to focus on questions of human existence." - Siddhartha Deb, New Statesman "Like the author's last novel ( When We Were Orphans ), Never Let Me Go is marred by a slapdash, explanatory ending that recalls the stilted, tie-up-all-the loose-ends conclusion of Hitchcock's Psycho . The remainder of the book, however, is a Gothic tour de force that showcases the same gifts that made Mr. Ishiguro's 1989 novel, The Remains of the Day , such a cogent performance." - Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times "The theme of cloning lets him push to the limit ideas he's nurtured in earlier fiction about memory and the human self; the school's hothouse seclusion makes it an ideal lab for his fascination withcliques, loyalty amd friendship." - Sarah Kerr, The New York Times Book Review "The strangeness, like the strangeness in Ishiguro�s most imaginative novel, The Unconsoled , is ingeniously evoked -- by means of literal-minded accounts of things that don�t quite add up -- and teasing out the hidden story is the main pleasure of the book. (...) Unfortunately, Never Let Me Go includes a carefully staged revelation scene, in which everything is, somewhat portentously, explained. It�s a little Hollywood, and the elucidation is purchased at too high a price. The scene pushes the novel over into science fiction, and this is not, at heart, where it seems to want to be." - Louis Menand, The New Yorker "(A) powerful and sad narrative. Ishiguro�s -- and Kathy�s -- brave new world is one whose lingering implications we will do well to take to heart." - Stephen Bernstein, Review of Contemporary Fiction "For the meantime, reading Never Let Me Go is like attending the bedside of an organ transplant patient forever on the verge of rejecting. We yearn for the science fiction and romantic aspects of Ishiguro's story to match and thrive. We want desperately for it to work, but somehow, in spite of all that, it never quite takes." - David Kipen, San Francisco Chronicle "The result, alas, is a novel quite without vulgarity, but one where the situation is totally implausible on every level. It is an awful thing to say, but I believed so little in any of the people, their situation, or the way they spoke that I didn�t really care what happened to them. They could have been turned into tins of Pedigree Chum without raising much concern. In the past, Ishiguro has been an exceedingly interesting novelist, but he looks increasingly like one at the mercy of his limited linguistic inventiveness." - Philip Hensher, The Spectator "A clear frontrunner to be the year's most extraordinary novel (.....) Graceful and grim, the novel never hardens into anything as clear-cut as allegory but it resonates with disquieting suggestiveness." - Peter Kemp, Sunday Times " Never Let Me Go is an intriguing, chilling and ultimately desolate fable. (...) Never Let Me Go will probably disappoint readers for whom the solution of a mystery is all-in-all, or those who want the gratification of full-on horror. But in its evocation of a pervasive menace and despair almost but not quite lost in translation - made up of the shadows of things not said, glimpsed out of the corner of one's eye - the novel is masterly." - Caroline Moore, The Telegraph " Never Let Me Go is a very strange novel. (...) Inevitably, reading Never Let Me Go is not exactly an enjoyable experience. There is no aesthetic thrill to be had from the sentences -- except that of a writer getting the desired dreary effect exactly right. But the novel repays the effort in spades, building to a surprisingly moving climax and echoing around the brain for days afterwards." - Theo Tait, The Telegraph " Never Let Me Go could easily be mistaken for a political novel or a futuristic thriller, but at its dark heart it's an existential fable about people trying to wring some happiness out of life before the lights go out. " - Lev Grossman, Time "This spare approach to description is also one of the most striking qualities of Ishiguro�s prose, and his tendency to cut back -- to foreshorten his characters� horizons -- has become more marked than ever. Here, the austere minimalism of description becomes meaningful. (...) Meaningful though it is, the lack of description in Never Let Me Go is oppressive, and it is questionable whether Ishiguro intends the novel to come across quite so severely as it does." - Tobias Hill, The Times " Never Let Me Go takes the subject of mortality to a vivid extreme. (...) The beauty in this novel must be carefully distinguished from its power to distress. Ultimately, there is a connection: the depth and quality of the relationships between Kath, Tommy and Ruth certainly accentuate the cruelty of their deaths. From under the shadow of their fate, Ishiguro draws warmly compelling vignettes of love and friendship that cumulatively establish an urgent and engrossing narrative pace." - Ruth Scurr, Times Literary Supplement "The death sentence that is Hailsham can for much of the book only be read between the lines, and as in Ishiguro's five previous novels, horror lies in the mundane. (...) A 1984 for the bioengineering age, the novel is a warning and a glimpse into the future whose genius will be recognized as reality catches up." - James Browning, The Village Voice "(Q)uite wonderful (...) the best Ishiguro has written since the sublime The Remains of the Day . It is almost literally a novel about humanity: what constitutes it, what it means, how it can be honored or denied." - Jonathan Yardley, The Washington Post Please note that these ratings solely represent the complete review 's biased interpretation and subjective opinion of the actual reviews and do not claim to accurately reflect or represent the views of the reviewers. Similarly the illustrative quotes chosen here are merely those the complete review subjectively believes represent the tenor and judgment of the review as a whole. We acknowledge (and remind and warn you) that they may, in fact, be entirely unrepresentative of the actual reviews by any other measure.

The complete review 's Review :

I suppose it was because even at that age -- we were nine or ten -- we knew just enough to make us wary of that whole territory. It's hard now to remember just how much we knew by then. We certainly knew -- though not in any deep sense -- that we were different from our guardians, and also from the normal people outside; we perhaps even knew that a long way down the line there were donations waiting for us. But we didn't really know what that meant. If we were keen to avoid certain topics, it was probably more because it embarrassed us.

None of you will go to America, none of you will be film stars. And none of you will be working in supermarkets as I heard some of you planning the other day. Your lives are set out for you. You'll become adults, then before you're old, before you're even middle-aged, you'll start to donate your vital organs. That's what each of youw as created to do.

About the Author :

Kazuo Ishiguro was born in Japan in 1954 and moved to Great Britain when he was five. He won the Booker Prize for his novel The Remains of the Day , has received an OBE, and was named Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. In 2017, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

© 2005-2021 the complete review Main | the New | the Best | the Rest | Review Index | Links

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

April 17, 2005. NEVER LET ME GO By Kazuo Ishiguro. 288 pp. Alfred A. Knopf. $24. There is no way around revealing the premise of Kazuo Ishiguro's new novel. It is brutal, especially for a writer ...

Never Let Me Go. Directed by Mark Romanek. Drama, Romance, Sci-Fi. R. 1h 43m. By Manohla Dargis. Sept. 14, 2010. The limits of beauty or, more rightly, the uses of visual beauty are revealed in ...

March 20, 2005. Kazuo Ishiguro's "Never Let Me Go" (Knopf; $24) is a novel about a young woman named Kathy H., and her friendships with two schoolmates, Ruth and Tommy. The triangle is a ...

This echoes the loss of innocence Cath undergoes in the story, although she is also sympathetic precisely because her destiny in this nightmarish, dystopian world precludes the possibility of ...

His latest novel is The Buried Giant, a New York Times bestseller. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature 2017. His novels An Artist of the Floating World (1986), When We Were Orphans (2000), and Never Let Me Go (2005) were all shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. In 2008, The Times ranked Ishiguro 32nd on their list of "The 50 Greatest ...

In this vivid and moving book, Orange articulates the challenges and complexities not only of Native Americans, but also of America itself. Share your opinion of this book. An ambitious scientific experiment wreaks horrendous toll in the Booker-winning British author's disturbingly eloquent sixth novel (after When We Were Orphans, 2000).

Unfortunately, Never Let Me Go includes a carefully staged revelation scene, in which everything is, somewhat portentously, explained. It's a little Hollywood, and the elucidation is purchased at too high a price. The scene pushes the novel over into science fiction, and this is not, at heart, where it seems to want to be.

About Never Let Me Go. NOBEL PRIZE WINNER • From the acclaimed, bestselling author of The Remains of the Day comes "a Gothic tour de force" (The New York Times) with an extraordinary twist—a moving, suspenseful, beautifully atmospheric modern classic. As children, Kathy, Ruth, and Tommy were students at Hailsham, an exclusive boarding school secluded in the English countryside.