ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, how to help middle school students develop research skills.

As the research skills you teach middle school students can last them all their lives, it’s essential to help them develop good habits early in their school careers.

Research skills are useful in nearly every subject, whether it’s English, math, social studies or science, and they will continue to pay off for students every day of their schooling. Understanding the most important research skills that middle school students need will help reach these kids and make a long-term difference.

The research process

It is important for every student to understand that research is actually a process rather than something that happens naturally. The best researchers develop a process that allows them to fully comprehend the ideas they are researching and also turn the data into information that is usable for whatever the end purpose may be. Here is an example of a research process that you may consider using when teaching research skills in your middle school classroom:

- Form a question : Research should be targeted; develop a question you want to answer before progressing any further.

- Decide on resources : Not every resource is good for every question/problem. Identify the resources that will work best for you.

- Gather raw data : First, gather information in its rawest form; do not attempt to make sense of it at this point.

- Sort the data : After you have the information in front of you, decide what is important to you and how you will use it. Not all data will be reliable or worthwhile.

- Process information : Turn the data into usable information. This processing step may take longer than the rest combined. This is where you really see your data shape into something exciting.

- Create a final piece : This is where you would write a research paper, create a project or build a graph or other visual piece with your information. This may or may not be a formal document.

- Evaluate : Look back on the process. Where did you experience success and failure? Did you find an answer to your question?

This process can be adjusted to suit the needs of your particular classroom or the project you are working on. Just remember that the goal is not only to find the data for this particular project, but to teach your students research skills that will help them in the long run.

Research is a very important part of the learning process as well as being useful in real-life once the student graduates. Middle school is a great time to develop these skills as many high school teachers expect that students already have this knowledge.

Students who are well-prepared as researchers will be able to handle nearly any assignment that comes their way. Finding new ways to teach research skills to middle school students need will be a challenge, but the results are well worth it as you see your students succeed in your classroom and set the stage for further success throughout their schooling experience.

You may also like to read

- Web Research Skills: Teaching Your Students the Fundamentals

- Building Math Skills in High School Students

- How to Help High School Students with Career Research

- Five Free Websites for Students to Build Research Skills

- Homework in Middle School: Building a Foundation for Study Skills

- 5 Novels for Middle School Students that Celebrate Diversity

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Engaging Activities , Middle School (Grades: 6-8)

- Math Teaching Resources | Classroom Activitie...

- Online & Campus Doctorate (EdD) in Organizati...

- Master's in Reading and Literacy Education

Teaching Research Skills to K-12 Students in The Classroom

Research is at the core of knowledge. Nobody is born with an innate understanding of quantum physics. But through research , the knowledge can be obtained over time. That’s why teaching research skills to your students is crucial, especially during their early years.

But teaching research skills to students isn’t an easy task. Like a sport, it must be practiced in order to acquire the technique. Using these strategies, you can help your students develop safe and practical research skills to master the craft.

What Is Research?

By definition, it’s a systematic process that involves searching, collecting, and evaluating information to answer a question. Though the term is often associated with a formal method, research is also used informally in everyday life!

Whether you’re using it to write a thesis paper or to make a decision, all research follows a similar pattern.

- Choose a topic : Think about general topics of interest. Do some preliminary research to make sure there’s enough information available for you to work with and to explore subtopics within your subject.

- Develop a research question : Give your research a purpose; what are you hoping to solve or find?

- Collect data : Find sources related to your topic that will help answer your research questions.

- Evaluate your data : Dissect the sources you found. Determine if they’re credible and which are most relevant.

- Make your conclusion : Use your research to answer your question!

Why Do We Need It?

Research helps us solve problems. Trying to answer a theoretical question? Research. Looking to buy a new car? Research. Curious about trending fashion items? Research!

Sometimes it’s a conscious decision, like when writing an academic paper for school. Other times, we use research without even realizing it. If you’re trying to find a new place to eat in the area, your quick Google search of “food places near me” is research!

Whether you realize it or not, we use research multiple times a day, making it one of the most valuable lifelong skills to have. And it’s why — as educators —we should be teaching children research skills in their most primal years.

Teaching Research Skills to Elementary Students

In elementary school, children are just beginning their academic journeys. They are learning the essentials: reading, writing, and comprehension. But even before they have fully grasped these concepts, you can start framing their minds to practice research.

According to curriculum writer and former elementary school teacher, Amy Lemons , attention to detail is an essential component of research. Doing puzzles, matching games, and other memory exercises can help equip students with this quality before they can read or write.

Improving their attention to detail helps prepare them for the meticulous nature of research. Then, as their reading abilities develop, teachers can implement reading comprehension activities in their lesson plans to introduce other elements of research.

One of the best strategies for teaching research skills to elementary students is practicing reading comprehension . It forces them to interact with the text; if they come across a question they can’t answer, they’ll need to go back into the text to find the information they need.

Some activities could include completing compare/contrast charts, identifying facts or questioning the text, doing background research, and setting reading goals. Here are some ways you can use each activity:

- How it translates : Step 3, collect data; Step 4, evaluate your data

- Questioning the text : If students are unsure which are facts/not facts, encourage them to go back into the text to find their answers.

- How it translates : Step 3, collect data; Step 4, evaluate your data; Step 5, make your conclusion

- How it translates : Step 1, choose your topic

- How it translates : Step 2, develop a research question; Step 5, make your conclusion

Resources for Elementary Research

If you have access to laptops or tablets in the classroom, there are some free tools available through Pennsylvania’s POWER Kids to help with reading comprehension. Scholastic’s BookFlix and TrueFlix are 2 helpful resources that prompt readers with questions before, after, and while they read.

- BookFlix : A resource for students who are still new to reading. Students will follow along as a book is read aloud. As they listen or read, they will be prodded to answer questions and play interactive games to test and strengthen their understanding.

- TrueFlix : A resource for students who are proficient in reading. In TrueFlix, students explore nonfiction topics. It’s less interactive than BookFlix because it doesn’t prompt the reader with games or questions as they read. (There are still options to watch a video or listen to the text if needed!)

Teaching Research Skills to Middle School Students

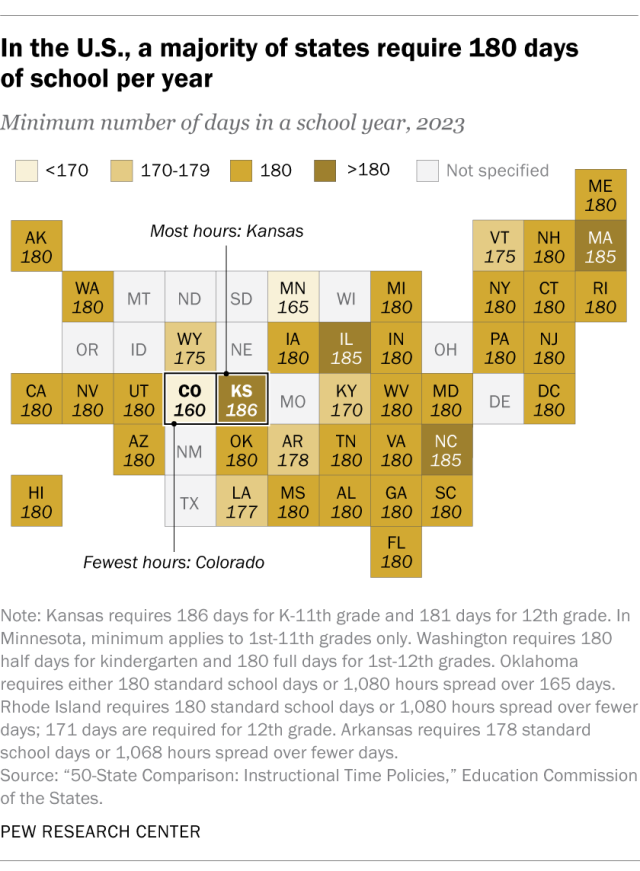

By middle school, the concept of research should be familiar to students. The focus during this stage should be on credibility . As students begin to conduct research on their own, it’s important that they know how to determine if a source is trustworthy.

Before the internet, encyclopedias were the main tool that people used for research. Now, the internet is our first (and sometimes only) way of looking information up.

Unlike encyclopedias which can be trusted, students must be wary of pulling information offline. The internet is flooded with unreliable and deceptive information. If they aren’t careful, they could end up using a source that has inaccurate information!

How To Know If A Source Is Credible

In general, credible sources are going to come from online encyclopedias, academic journals, industry journals, and/or an academic database. If you come across an article that isn’t from one of those options, there are details that you can look for to determine if it can be trusted.

- The author: Is the author an expert in their field? Do they write for a respected publication? If the answer is no, it may be good to explore other sources.

- Citations: Does the article list its sources? Are the sources from other credible sites like encyclopedias, databases, or journals? No list of sources (or credible links) within the text is usually a red flag.

- Date: When was the article published? Is the information fresh or out-of-date? It depends on your topic, but a good rule of thumb is to look for sources that were published no later than 7-10 years ago. (The earlier the better!)

- Bias: Is the author objective? If a source is biased, it loses credibility.

An easy way to remember what to look for is to utilize the CRAAP test . It stands for C urrency (date), R elevance (bias), A uthority (author), A ccuracy (citations), and P urpose (bias). They’re noted differently, but each word in this acronym is one of the details noted above.

If your students can remember the CRAAP test, they will be able to determine if they’ve found a good source.

Resources for Middle School Research

To help middle school researchers find reliable sources, the database Gale is a good starting point. It has many components, each accessible on POWER Library’s site. Gale Litfinder , Gale E-books , or Gale Middle School are just a few of the many resources within Gale for middle school students.

Teaching Research Skills To High Schoolers

The goal is that research becomes intuitive as students enter high school. With so much exposure and practice over the years, the hope is that they will feel comfortable using it in a formal, academic setting.

In that case, the emphasis should be on expanding methodology and citing correctly; other facets of a thesis paper that students will have to use in college. Common examples are annotated bibliographies, literature reviews, and works cited/reference pages.

- Annotated bibliography : This is a sheet that lists the sources that were used to conduct research. To qualify as annotated , each source must be accompanied by a short summary or evaluation.

- Literature review : A literature review takes the sources from the annotated bibliography and synthesizes the information in writing.

- Works cited/reference pages : The page at the end of a research paper that lists the sources that were directly cited or referenced within the paper.

Resources for High School Research

Many of the Gale resources listed for middle school research can also be used for high school research. The main difference is that there is a resource specific to older students: Gale High School .

If you’re looking for some more resources to aid in the research process, POWER Library’s e-resources page allows you to browse by grade level and subject. Take a look at our previous blog post to see which additional databases we recommend.

Visit POWER Library’s list of e-resources to start your research!

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Teaching Expertise

- Classroom Ideas

- Teacher’s Life

- Deals & Shopping

- Privacy Policy

Research Activities For Middle School: Discussions, Tips, Exploration, And Learning Resources

February 6, 2024 // by Josilyn Markel

Learning to research effectively is an important skill that middle-school-aged students can learn and carry with them for their whole academic careers. The students in question will use these skills for everything from reading news articles to writing a systematic review of their sources. With increased demands on students these days, it’s never too early to introduce these sophisticated research skills.

We’ve collected thirty of the best academic lessons for middle school students to learn about sophisticated research skills that they’ll use for the rest of their lives.

1. Guiding Questions for Research

When you first give a research project to middle school students, it’s important to make sure that they really understand the research prompts. You can use this guiding questions tool with students to help them draw on existing knowledge to properly contextualize the prompt and assignment before they even pick up a pen.

Learn More: Mrs. Spangler in the Middle

2. Teaching Research Essential Skills Bundle

This bundle touches on all the writing skills, planning strategies, and so-called soft skills that students will need to get started on their first research project. These resources are especially geared towards middle school-aged students to help them with cognitive control tasks plus engaging and active lessons.

Learn More: Pinterest

3. How to Develop a Research Question

Before a middle school student can start their research time on task, they have to form a solid research question. This resource features activities for students that will help them identify a problem and then formulate a question that will guide their research project going first.

Learn More: YouTube

4. Note-Taking Skills Infographic

For a strong introduction and/or systematic review of the importance of note-taking, look no further than this infographic. It covers several excellent strategies for taking the most important info from a source, and it also gives tips for using these strategies to strengthen writing skills.

Learn More: Word Counter

5. Guide to Citing Online Sources

One of the more sophisticated research skills is learning to cite sources. These days, the internet is the most popular place to find research sources, so learning the citation styles for making detailed citations for internet sources is an excellent strategy. This is a skill that will stick with middle school students throughout their entire academic careers!

Learn More: Educator’s Technology

6. Guided Student-Led Research Projects

This is a great way to boost communication between students while also encouraging choice and autonomy throughout the research process. This really opens up possibilities for students and boosts student activity and engagement throughout the whole project. The group setup also decreases the demands on students as individuals.

Learn More: The Thinker Builder

7. Teaching Students to Fact-Check

Fact-checking is an important meta-analytic review skill that every student needs. This resource introduces probing questions that students can ask in order to ensure that the information they’re looking at is actually true. This can help them identify fake news, find more credible sources, and improve their overall sophisticated research skills.

Learn More: Just Add Students

8. Fact-Checking Like a Pro

This resource features great teaching strategies (such as visualization) to help alleviate the demands on students when it comes to fact-checking their research sources. It’s perfect for middle school-aged students who want to follow the steps to make sure that they’re using credible sources in all of their research projects, for middle school and beyond!

9. Website Evaluation Activity

With this activity, you can use any website as a backdrop. This is a great way to help start the explanation of sources that will ultimately lead to helping students locate and identify credible sources (rather than fake news). With these probing questions, students will be able to evaluate websites effectively.

10. How to Take Notes in Class

This visually pleasing resource tells students everything they need to know about taking notes in a classroom setting. It goes over how to glean the most important information from the classroom teacher, and how to organize the info in real-time, and it gives tips for cognitive control tasks and other sophisticated research skills that will help students throughout the research and writing process.

Learn More: Visualistan

11. Teaching Research Papers: Lesson Calendar

If you have no idea how you’re going to cover all the so-called soft skills, mini-lessons, and activities for students during your research unit, then don’t fret! This calendar breaks down exactly what you should be teaching, and when. It introduces planning strategies, credible sources, and all the other research topics with a logical and manageable flow.

Learn More: Discover Hub Pages

12. Google Docs Features for Teaching Research

With this resource, you can explore all of the handy research-focused features that are already built into Google Docs! You can use it to build activities for students or to make your existing activities for students more tech-integrated. You can use this tool with students from the outset to get them interested and familiar with the Google Doc setup.

13. Using Effective Keywords to Search the Internet

The internet is a huge place, and this vast amount of knowledge puts huge demands on students’ skills and cognition. That’s why they need to learn how to search online effectively, with the right keywords. This resource teaches middle school-aged students how to make the most of all the search features online.

Learn More: Teachers Pay Teachers

14. How to Avoid Plagiarism: “Did I Plagiarize?”

This student activity looks at the biggest faux pas in middle school research projects: plagiarism. These days, the possibilities for students to plagiarize are endless, so it’s important for them to learn about quotation marks, paraphrasing, and citations. This resource includes information on all of those and in a handy flow chart to keep them right!

Learn More: Twitter

15. 7 Tips for Recognizing Bias

This is a resource to help middle school-aged students recognize the differences between untrustworthy and credible sources. It gives a nice explanation of sources that are trustworthy and also offers a source of activities that students can use to test and practice identifying credible sources.

Learn More: We Are Teachers

16. UNESCO’s Laws for Media Literacy

This is one of those great online resources that truly focuses on the students in question, and it serves a larger, global goal. It offers probing questions that can help middle school-aged children determine whether or not they’re looking at credible online resources. It also helps to strengthen the so-called soft skills that are necessary for completing research.

Learn More: SLJ Blogs

17. Guide for Evaluating a News Article

Here are active lessons that students can use to learn more about evaluating a news article, whether it’s on a paper or online resource. It’s also a great tool to help solidify the concept of fake news and help students build an excellent strategy for identifying and utilizing credible online sources.

Learn More: Valencia College

18. Middle School Research Projects Middle School Students Will Love

Here is a list of 30 great research projects for middle schoolers, along with cool examples of each one. It also goes through planning strategies and other so-called soft skills that your middle school-aged students will need in order to complete such projects.

Learn More: Madly Learning

19. Teaching Analysis with Body Biographies

This is a student activity and teaching strategy all rolled into one! It looks at the importance of research and biographies, which brings a human element to the research process. It also helps communication between students and helps them practice those so-called soft skills that come in handy while researching.

Learn More: Study All Knight

20. Top Tips for Teaching Research in Middle School

When it comes to teaching middle school research, there are wrong answers and there are correct answers. You can learn all the correct answers and teaching strategies with this resource, which debunks several myths about teaching the writing process at the middle school level.

Learn More: Teaching ELA with Joy

21. Teaching Students to Research Online: Lesson Plan

This is a ready-made lesson plan that is ready to present. You don’t have to do tons of preparation, and you’ll be able to explain the basic and foundational topics related to research. Plus, it includes a couple of activities to keep students engaged throughout this introductory lesson.

Learn More: Kathleen Morris

22. Project-Based Learning: Acceptance and Tolerance

This is a series of research projects that look at specific problems regarding acceptance and tolerance. It offers prompts for middle school-aged students that will get them to ask big questions about themselves and others in the world around them.

Learn More: Sandy Cangelosi

23. 50 Tiny Lessons for Teaching Research Skills in Middle School

These fifty mini-lessons and activities for students will have middle school-aged students learning and applying research skills in small chunks. The mini-lessons approach allows students to get bite-sized information and focus on mastering and applying each step of the research process in turn. This way, with mini-lessons, students don’t get overwhelmed with the whole research process at once. In this way, mini-lessons are a great way to teach the whole research process!

24. Benefits of Research Projects for Middle School Students

Whenever you feel like it’s just not worth it to go to the trouble to teach your middle school-aged students about research, let this list motivate you! It’s a great reminder of all the great things that come with learning to do good research at an early age.

Learn More: Thrive in Grade Five

25. Top 5 Study and Research Skills for Middle Schoolers

This is a great resource for a quick and easy overview of the top skills that middle schoolers will need before they dive into research. It outlines the most effective tools to help your students study and research well, throughout their academic careers.

Learn More: Meagan Gets Real

26. Research with Informational Text: World Travelers

This travel-themed research project will have kids exploring the whole world with their questions and queries. It is a fun way to bring new destinations into the research-oriented classroom.

Learn More: The Superhero Teacher

27. Project-Based Learning: Plan a Road Trip

If you want your middle school-aged students to get into the researching mood, have them plan a road trip! They’ll have to examine the prompt from several angles and collect data from several sources before they can put together a plan for an epic road trip.

Learn More: Appletastic Learning

28. Methods for Motivating Writing Skills

When your students just are feeling up to the task of research-based writing, it’s time to break out these motivational methods. With these tips and tricks, you’ll be able to get your kids in the mood to research, question, and write!

29. How to Set Up a Student Research Station

This article tells you everything you need to know about a student center focused on sophisticated research skills. These student center activities are engaging and fun, and they touch on important topics in the research process, such as planning strategies, fact-checking skills, citation styles, and some so-called soft skills.

Learn More: Upper Elementary Snapshots

30. Learn to Skim and Scan to Make Research Easier

These activities for students are geared towards encouraging reading skills that will ultimately lead to better and easier research. The skills in question? Skimming and scanning. This will help students read more efficiently and effectively as they research from a variety of sources.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Teaching ELA with Joy

Middle School ELA Resources

6 Ideas for Teaching Research Skills

By Joy Sexton Leave a Comment

When thinking about ideas for teaching research skills, teachers can easily become overwhelmed. That’s mainly because our standards list so many requirements for students to master! If your school requires a major research paper, you might need to start off with some smaller practice pieces. Do your students know how to paraphrase? Can they judge if a website is credible? Do they know how to compose an open-ended question? How about citing sources? Check out these activities that will help your students gain essential practice with research skills.

Ideas for Teaching Research Skills

1. Say It Your Way – One great place to start is getting students in the habit of paraphrasing. Choose an interesting topic and a short article to demonstrate. An online encyclopedia comes in handy here. We worked with information on a particular dinosaur. Project the article and with class participation, highlight 5 pieces of key information. This is the information students will be “taking notes” on. Then query the students how each piece of information could be stated in bulleted notes (without copying full sentences!). Model the bulleted note-taking as students complete their own copy. When the bulleted notes are complete, engage the class in composing new sentences that are paraphrased. Again, model writing this paragraph as students follow suit. Now the process of note-taking and paraphrasing should seem “doable” in their own research.

2. Surprising Facts – A fun way for students to dive into research is to give them a topic and simply task them with finding facts that are surprising . This activity works great with partners. Topics could tie in with a current class novel or story (such as “elephant” from The Giver) or even an author. Surprising facts about Gary Paulsen, Kwame Alexander, or Edgar Alan Poe make an interesting class discussion! Students enjoy sharing their findings. I devised a free handout where students can record the topic, their surprising facts, and the website(s) they used. Grab it in Google Docs and copy to your drive by clicking the link: https://bit.ly/3Nah9UB

3. Give Credit Where It’s Due – Most students understand that sources need to be cited. However, many remain unclear on the process. A demonstration using a citation generator will help. I like www.bibme.org , but if you google “citation generator” you’ll find a slew of them. I open a few tabs in advance with animal websites. To demonstrate, grab the URLs and insert into the generator. Cut and paste the citations to a blank document. Then you can show students how to indent and alphabetize. For practice, give students a list of several websites. You could also include a magazine article and a book. With a partner, have them construct the works cited using a generator, indenting and alphabetizing correctly.

4. Support an Opinion – Students love to voice their opinions , but need practice supporting them with facts . Lucky for us, there are loads of argument topics available free online. You can offer several topic choices, and students choose one and respond with their opinion. Next, have them locate 2-3 important facts or statistics that specifically support their opinion. Make sure to emphasize that the information will need to be paraphrased. And since sources were used, a Works Cited should also be added.

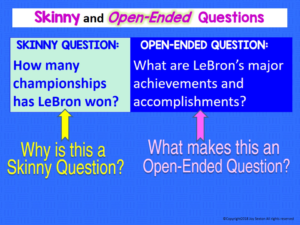

5. Good Question! – One purpose of research is to answer a question, so students need practice in formulating good questions . An open-ended question, one that requires more than just one answer, is the goal. Start by demonstrating the difference between an open-ended question and a “thin” or “skinny” question (not open-ended). One way is to project an image of a violin on your whiteboard. Then type or write out these questions: 1. How many strings does a violin have? 2. How is a violin made? Ask students which is the open-ended question and why. Then project another image. Ask for volunteers to formulate a thin question, and then an open-ended question. Once they understand this concept, let all students practice composing both thin and open-ended questions. This activity works well in groups. Each student contributes a topic.

6. Format is Key – A sure-fire way to get students excited about a research project is offering engaging formats for presentation. PowerPoint is well known by most students, but take time to demonstrate some other great options. Canva allows students to create awesome Infographics! Or how about a tri-fold brochure in Publisher? Students can make up a quick template with custom headings. Set a timer for 10-15 minutes and let students experiment with the possibilities. My students have enjoyed a Q & A format, using a template I created with PowerPoint. Even students who prefer typing their report in paragraphs can easily design a poster. Along with the paragraphs, just add images, captions, topic, and headings.

I hope I have broadened your ideas for teaching research skills. I think you’ll agree that students need time and mini-lessons to get comfortable with the procedures we require. A quick graphic organizer coupled with a short activity can help solidify the skills they’ll need.

Here’s another post I wrote that will give you more helpful ideas for teaching research skills: 10 Ideas to Make Teaching Research Easier

Join the Newsletter

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

K-12 Internet Resource Center

A totally free index of Internet resources for the K-12 Community.

50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills

This post outlines 50 ideas for activities that could be done in just a few minutes (or stretched out to a longer lesson if you have the time!). You’ll find a PDF summary below too! This post shares ideas for mini-lessons that could be carried out in the classroom throughout the year to help build students’ skills in the five areas of: clarify, search, delve, evaluate , and cite . It also includes ideas for learning about staying organised throughout the research process.

Today’s students have more information at their fingertips than ever before and this means the role of the teacher as a guide is more important than ever. Posted on February 26, 2019 by Kathleen Morris

Attributes: 4-5 6-8 Lesson Plan

Resource Link: https://www.kathleenamorris.com/2019/02/26/research-lessons/

- Research Skills

How to Teach Online Research Skills to Students in 5 Steps (Free Posters)

Please note, this post was updated in 2020 and I no longer update this website.

How often does this scenario play out in your classroom?

You want your students to go online and do some research for some sort of project, essay, story or presentation. Time ticks away, students are busy searching and clicking, but are they finding the useful and accurate information they need for their project?

We’re very fortunate that many classrooms are now well equipped with devices and the internet, so accessing the wealth of information online should be easier than ever, however, there are many obstacles.

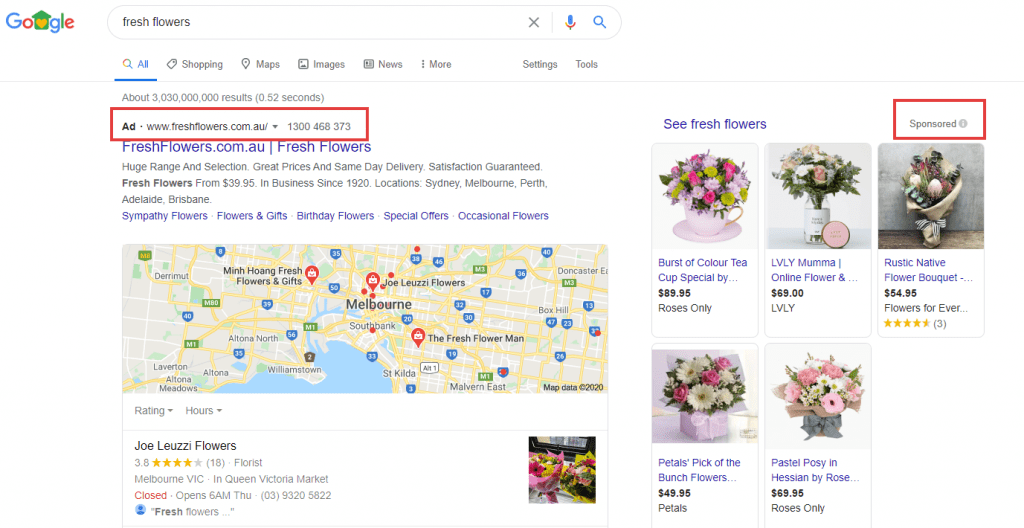

Students (and teachers) need to navigate:

- What search terms to put into Google or other search engines

- What search results to click on and read through (while avoiding inappropriate or irrelevant sites or advertisements)

- How to determine what information is credible, relevant and student friendly

- How to process, synthesize, evaluate , and present the information

- How to compare a range of sources to evaluate their reliability and relevancy

- How to cite sources correctly

Phew! No wonder things often don’t turn out as expected when you tell your students to just “google” their topic. On top of these difficulties some students face other obstacles including: low literacy skills, limited internet access, language barriers, learning difficulties and disabilities.

All of the skills involved in online research can be said to come under the term of information literacy, which tends to fall under a broader umbrella term of digital literacy.

Being literate in this way is an essential life skill.

This post offers tips and suggestions on how to approach this big topic. You’ll learn a 5 step method to break down the research process into manageable chunks in the classroom. Scroll down to find a handy poster for your classroom too.

How to Teach Information Literacy and Online Research Skills

The topic of researching and filtering information can be broken down in so many ways but I believe the best approach involves:

- Starting young and building on skills

- Embedding explicit teaching and mini-lessons regularly (check out my 50 mini-lesson ideas here !)

- Providing lots of opportunity for practice and feedback

- Teachers seeking to improve their own skills — these free courses from Google might help

- Working with your librarian if you have one

💡 While teaching research skills is something that should be worked on throughout the year, I also like the idea of starting the year off strongly with a “Research Day” which is something 7th grade teacher Dan Gallagher wrote about . Dan and his colleagues had their students spend a day rotating around different activities to learn more about researching online. Something to think about!

Google or a Kid-friendly Search Engine?

If you teach young students you might be wondering what the best starting place is.

I’ve only ever used Google with students but I know many teachers like to start with search engines designed for children. If you’ve tried these search engines, I’d love you to add your thoughts in a comment.

💡 If you’re not using a kid-friendly search engine, definitely make sure SafeSearch is activated on Google or Bing. It’s not foolproof but it helps.

Two search engines designed for children that look particularly useful include:

These sites are powered by Google SafeSearch with some extra filtering/moderating.

KidzSearch contains additional features like videos and image sections to browse. While not necessarily a bad thing, I prefer the simple interface of Kiddle for beginners.

Read more about child-friendly search engines

This article from Naked Security provides a helpful overview of using child-friendly search engines like Kiddle.

To summarise their findings, search-engines like Kiddle can be useful but are not perfect.

For younger children who need to be online but are far too young to be left to their own devices, and for parents and educators that want little ones to easily avoid age-inappropriate content, these search engines are quite a handy tool. For older children, however, the results in these search engines may be too restrictive to be useful, and will likely only frustrate children to use other means.

Remember, these sorts of tools are not a replacement for education and supervision.

Maybe start with no search engine?

Another possible starting point for researching with young students is avoiding a search engine altogether.

Students could head straight to a site they’ve used before (or choose from a small number of teacher suggested sites). There’s a lot to be learned just from finding, filtering, and using information found on various websites.

Five Steps to Teaching Students How to Research Online and Filter Information

This five-step model might be a useful starting point for your students to consider every time they embark on some research.

Let’s break down each step. You can find a summary poster at the end.

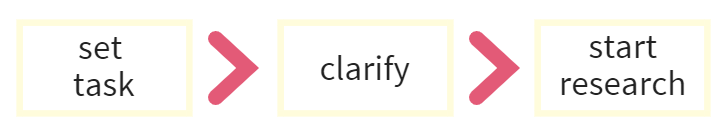

Students first need to take a moment to consider what information they’re actually looking for in their searches.

It can be a worthwhile exercise to add this extra step in between giving a student a task (or choice of tasks) and sending them off to research.

You could have a class discussion or small group conferences on brainstorming keywords , considering synonyms or alternative phrases , generating questions etc. Mindmapping might help too.

2016 research by Morrison showed that 80% of students rarely or never made a list of possible search words. This may be a fairly easy habit to start with.

Time spent defining the task can lead to a more effective and streamlined research process.

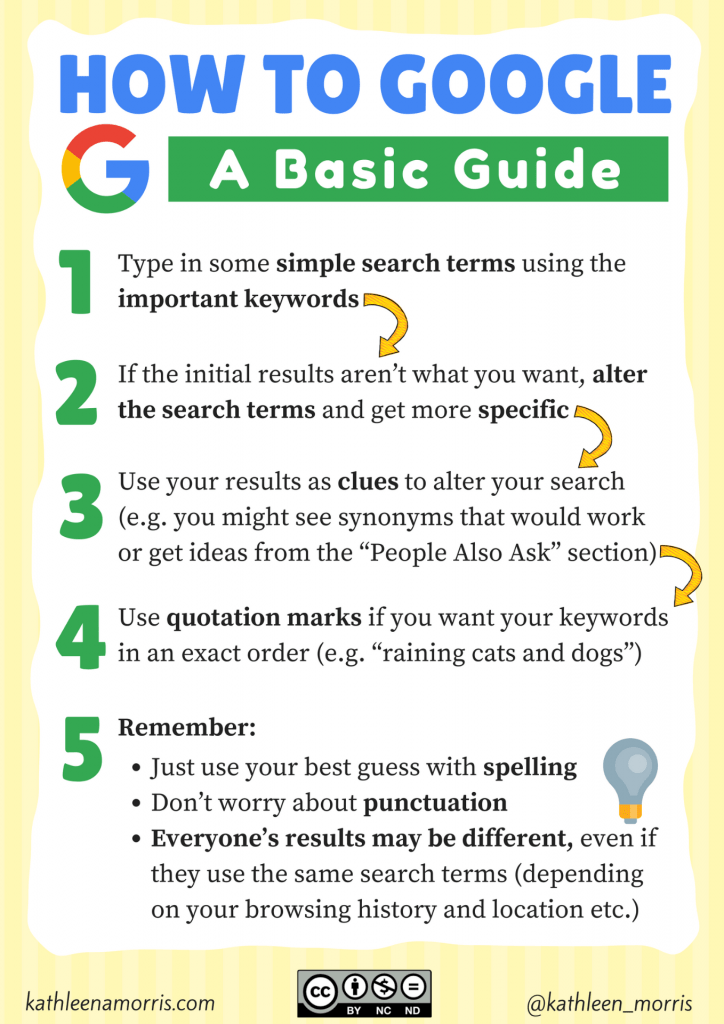

It sounds simple but students need to know that the quality of the search terms they put in the Google search box will determine the quality of their results.

There are a LOT of tips and tricks for Googling but I think it’s best to have students first master the basics of doing a proper Google search.

I recommend consolidating these basics:

- Type in some simple search terms using only the important keywords

- If the initial results aren’t what you want, alter the search terms and get more specific (get clues from the initial search results e.g. you might see synonyms that would work or get ideas from the “People Also Ask” section)

- Use quotation marks if you want your keywords in an exact order, e.g. “raining cats and dogs”

- use your best guess with spelling (Google will often understand)

- don’t worry about punctuation

- understand that everyone’s results will be different , even if they use the same search terms (depending on browser history, location etc.)

📌 Get a free PDF of this poster here.

Links to learn more about Google searches

There’s lots you can learn about Google searches.

I highly recommend you take a look at 20 Instant Google Searches your Students Need to Know by Eric Curts to learn about “instant searches”.

Med Kharbach has also shared a simple visual with 12 search tips which would be really handy once students master the basics too.

The Google Search Education website is an amazing resource with lessons for beginner/intermediate/advanced plus slideshows and videos. It’s also home to the A Google A Day classroom challenges. The questions help older students learn about choosing keywords, deconstructing questions, and altering keywords.

Useful videos about Google searches

How search works.

This easy to understand video from Code.org to explains more about how search works.

How Does Google Know Everything About Me?

You might like to share this video with older students that explains how Google knows what you’re typing or thinking. Despite this algorithm, Google can’t necessarily know what you’re looking for if you’re not clear with your search terms.

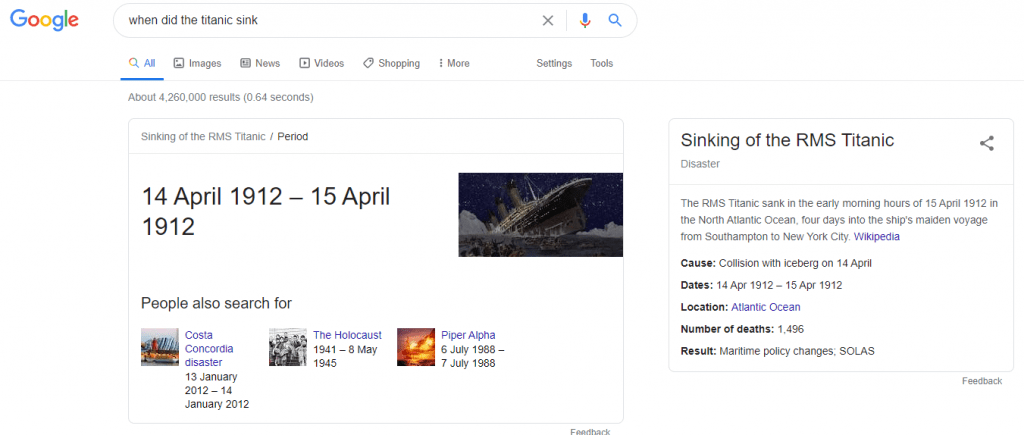

What about when the answer comes up in Google instantly?

If you’ve been using Google for a while, you know they are tweaking the search formula so that more and more, an answer will show up within the Google search result itself. You won’t even need to click through to any websites.

For example, here I’ve asked when the Titanic sunk. I don’t need to go to any websites to find out. The answer is right there in front of me.

While instant searches and featured snippets are great and mean you can “get an answer” without leaving Google, students often don’t have the background knowledge to know if a result is incorrect or not. So double checking is always a good idea.

As students get older, they’ll be able to know when they can trust an answer and when double checking is needed.

Type in a subject like cats and you’ll be presented with information about the animals, sports teams, the musical along with a lot of advertising. There are a lot of topics where some background knowledge helps. And that can only be developed with time and age.

Entering quality search terms is one thing but knowing what to click on is another.

You might like to encourage students to look beyond the first few results. Let students know that Google’s PageRank algorithm is complex (as per the video above), and many websites use Search Engine Optimisation to improve the visibility of their pages in search results. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’re the most useful or relevant sites for you.

As pointed out in this article by Scientific American ,

Skilled searchers know that the ranking of results from a search engine is not a statement about objective truth, but about the best matching of the search query, term frequency, and the connectedness of web pages. Whether or not those results answer the searchers’ questions is still up for them to determine.

Point out the anatomy of a Google search result and ensure students know what all the components mean. This could be as part of a whole class discussion, or students could create their own annotations.

An important habit to get into is looking at the green URL and specifically the domain . Use some intuition to decide whether it seems reliable. Does the URL look like a well-known site? Is it a forum or opinion site? Is it an educational or government institution? Domains that include .gov or .edu might be more reliable sources.

When looking through possible results, you may want to teach students to open sites in new tabs, leaving their search results in a tab for easy access later (e.g. right-click on the title and click “Open link in new tab” or press Control/Command and click the link).

Searchers are often not skilled at identifying advertising within search results. A famous 2016 Stanford University study revealed that 82% of middle-schoolers couldn’t distinguish between an ad labelled “sponsored content” and a real news story.

Time spent identifying advertising within search results could help students become much more savvy searchers. Looking for the words “ad” and “sponsored” is a great place to start.

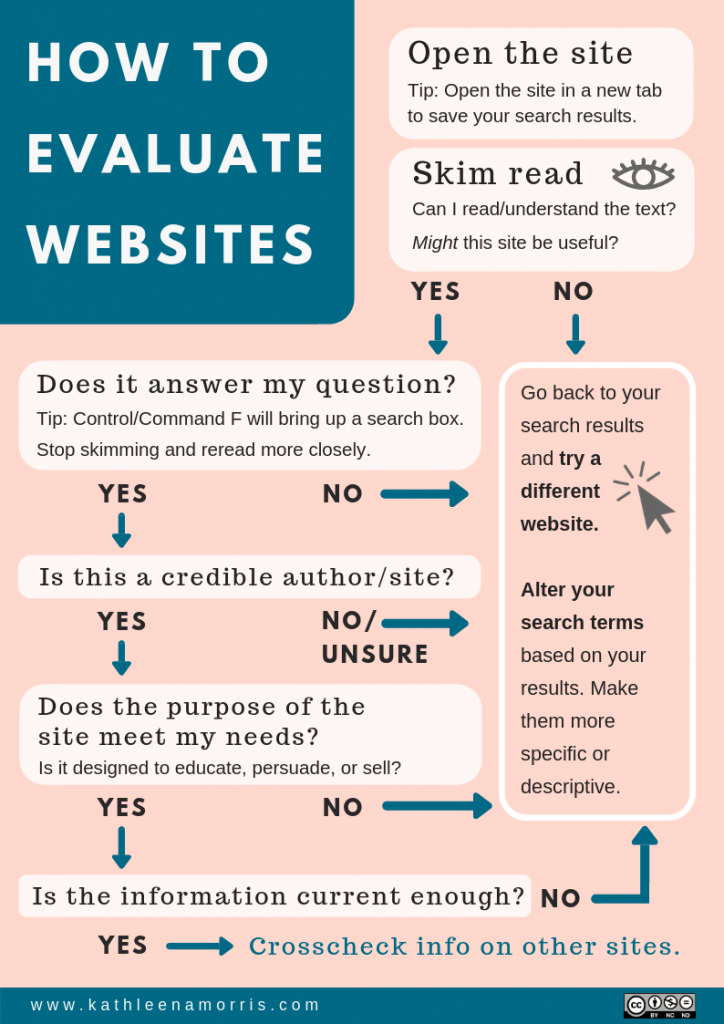

4) Evaluate

Once you click on a link and land on a site, how do you know if it offers the information you need?

Students need to know how to search for the specific information they’re after on a website. Teach students how to look for the search box on a webpage or use Control F (Command F on Mac) to bring up a search box that can scan the page.

Ensure students understand that you cannot believe everything you read . This might involve checking multiple sources. You might set up class guidelines that ask students to cross check their information on two or three different sites before assuming it’s accurate.

I’ve written a post all about teaching students how to evaluate websites . It includes this flowchart which you’re welcome to download and use in your classroom.

So your students navigated the obstacles of searching and finding information on quality websites. They’ve found what they need! Hooray.

Many students will instinctively want to copy and paste the information they find for their own work.

We need to inform students about plagiarism and copyright infringement while giving them the skills they need to avoid this.

- Students need to know that plagiarism is taking someone’s work and presenting it as your own. You could have a class discussion about the ethics and legalities of this.

- Students also need to be assured that they can use information from other sources and they should. They just need to say who wrote it, where it was from and so on.

All students can benefit from learning about plagiarism, copyright, how to write information in their own words, and how to acknowledge the source. However, the formality of this process will depend on your students’ age and your curriculum guidelines.

Give students lots of practice writing information in their own words. Younger students can benefit from simply putting stories or recounts in their own words. Older students could investigate the difference between paraphrasing and summarising .

There are some free online tools that summarise information for you. These aren’t perfect and aren’t a replacement from learning the skill but they could be handy for students to try out and evaluate. For example, students could try writing their own summary and then comparing it to a computer summary. I like the tool SMMRY as you can enter text or a URL of an article. Eric Curts shares a list of 7 summary tools in this blog post .

Students also need a lot of practice using quotation marks and citing sources .

The internet can offer a confusing web of information at times. Students need to be shown how to look for the primary source of information. For example, if they find information on Wikipedia, they need to cite from the bibliography at the bottom of the Wikipedia article, not Wikipedia itself.

There are many ways you can teach citation:

- I like Kathy Schrock’s PDF document which demonstrates how you can progressively teach citation from grades 1 to 6 (and beyond). It gives some clear examples that you could adapt for your own classroom use.

Staying organised!

You might also like to set up a system for students to organise their information while they’re searching. There are many apps and online tools to curate, annotate, and bookmark information, however, you could just set up a simple system like a Google Doc or Spreadsheet.

The format and function is simple and clear. This means students don’t have to put much thought into using and designing their collections. Instead, they can focus on the important curation process.

Bring These Ideas to Life With Mini-Lessons!

We know how important it is for students to have solid research skills. But how can you fit teaching research skills into a jam-packed curriculum? The answer may be … mini-lessons !

Whether you teach primary or secondary students, I’ve compiled 50 ideas for mini-lessons.

Try one a day or one a week and by the end of the school year, you might just be amazed at how independent your students are becoming with researching.

Become an Internet Search Master with This Google Slides Presentation

In early 2019, I was contacted by Noah King who is a teacher in Northern California.

Noah was teaching his students about my 5 step process outlined in this post and put together a Google Slides Presentation with elaboration and examples.

You’re welcome to use and adapt the Google Slides Presentation yourself. Find out exactly how to do this in this post.

The Presentation was designed for students around 10-11 years old but I think it could easily be adapted for different age groups.

Recap: How To Do Online Research

Despite many students being confident users of technology, they need to be taught how to find information online that’s relevant, factual, student-friendly, and safe.

Keep these six steps in mind whenever you need to do some online research:

- Clarify : What information are you looking for? Consider keywords, questions, synonyms, alternative phrases etc.

- Search : What are the best words you can type into the search engine to get the highest quality results?

- Delve : What search results should you click on and explore further?

- Evaluate : Once you click on a link and land on a site, how do you know if it offers the information you need?

- Cite : How can you write information in your own words (paraphrase or summarise), use direct quotes, and cite sources?

- Staying organised : How can you keep the valuable information you find online organised as you go through the research process?

Don’t forget to ask for help!

Lastly, remember to get help when you need it. If you’re lucky enough to have a teacher-librarian at your school, use them! They’re a wonderful resource.

If not, consult with other staff members, librarians at your local library, or members of your professional learning network. There are lots of people out there who are willing and able to help with research. You just need to ask!

Being able to research effectively is an essential skill for everyone . It’s only becoming more important as our world becomes increasingly information-saturated. Therefore, it’s definitely worth investing some classroom time in this topic.

Developing research skills doesn’t necessarily require a large chunk of time either. Integration is key and remember to fit in your mini-lessons . Model your own searches explicitly and talk out loud as you look things up.

When you’re modelling your research, go to some weak or fake websites and ask students to justify whether they think the site would be useful and reliable. Eric Curts has an excellent article where he shares four fake sites to help teach students about website evaluation. This would be a great place to start!

Introduce students to librarians ; they are a wonderful resource and often underutilised. It pays for students to know how they can collaborate with librarians for personalised help.

Finally, consider investing a little time in brushing up on research skills yourself . Everyone thinks they can “google” but many don’t realise they could do it even better (myself included!).

You Might Also Enjoy

Teaching Digital Citizenship: 10 Internet Safety Tips for Students

Free Images, Copyright, And Creative Commons: A Guide For Teachers And Students

8 Ways Teachers And Schools Can Communicate With Parents

How To Evaluate Websites: A Guide For Teachers And Students

14 Replies to “How to Teach Online Research Skills to Students in 5 Steps (Free Posters)”

Kathleen, I like your point about opening up sites in new tabs. You might be interested in Mike Caulfield’s ‘four moves’ .

What a fabulous resource, Aaron. Thanks so much for sharing. This is definitely one that others should check out too. Even if teachers don’t use it with students (or are teaching young students), it could be a great source of learning for educators too.

This is great information and I found the safe search sites you provided a benefit for my children. I searched for other safe search sites and you may want to know about them. http://www.kids-search.com and http://www.safesearch.tips .

Hi Alice, great finds! Thanks so much for sharing. I like the simple interface. It’s probably a good thing there are ads at the top of the listing too. It’s an important skill for students to learn how to distinguish these. 🙂

Great website! Really useful info 🙂

I really appreciate this blog post! Teaching digital literacy can be a struggle. This topic is great for teachers, like me, who need guidance in effectively scaffolding for scholars who to use the internet to gain information.

So glad to hear it was helpful, Shasta! Good luck teaching digital literacy!

Why teachers stopped investing in themselves! Thanks a lot for the article, but this is the question I’m asking myself after all teachers referring to google as if it has everything you need ! Why it has to come from you and not the whole education system! Why it’s an option? As you said smaller children don’t need search engine in the first place! I totally agree, and I’m soo disappointed how schooling system is careless toward digital harms , the very least it’s waste of the time of my child and the most being exposed to all rubbish on the websites. I’m really disappointed that most teachers are not thinking taking care of their reputation when it comes to digital learning. Ok using you tube at school as material it’s ok , but why can’t you pay little extra to avoid adverts while teaching your children! Saving paper created mountains of electronic-toxic waste all over the world! What a degradation of education.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, Shohida. I disagree that all schooling systems are careless towards ‘digital harms’, however, I do feel like more digital citizenship education is always important!

Hi Kathleen, I love your How to Evaluate Websites Flow Chart! I was wondering if I could have permission to have it translated into Spanish. I would like to add it to a Digital Research Toolkit that I have created for students.

Thank you! Kristen

Hi Kristen, You’re welcome to translate it! Please just leave the original attribution to my site on there. 🙂 Thanks so much for asking. I really hope it’s useful to your students! Kathleen

[…] matter how old your child is, there are many ways for them to do research into their question. For very young children, you’ll need to do the online research work. Take your time with […]

[…] digs deep into how teachers can guide students through responsible research practices on her blog (2019). She suggests a 5 step model for elementary students on how to do online […]

Writing lesson plans on the fly outside of my usual knowledge base (COVID taken down so many teachers!) and this info is precisely what I needed! Thanks!!!

Comments are closed.

Guidelines for Teaching Middle and High School Students to Read and Write Well: Six Features of Effective Instruction

On this page:, finding 1: students learn skills and knowledge in multiple lesson types, finding 2: teachers integrate test preparation into instruction, finding 3: teachers make connections across instruction, curriculum, and life, finding 4: students learn strategies for doing the work, finding 5: students are expected to be generative thinkers, finding 6: classrooms foster cognitive collaboration.

Most classroom teachers work hard planning lessons, choosing materials, teaching classes, working with individual students, and assessing student progress. Yet some schools and teachers seem to be more successful than others. What makes the difference? Researchers at the National Research Center on English Learning & Achievement (CELA) are answering this question through a set of studies that examine student achievement in reading, writing, and other important literacy skills in classrooms across the country. These studies include examinations of student work and test scores, classroom observations, and interviews of students, teachers, and administrators in a variety of sites that represent the nation’s diversity.

One of the studies has been examining English programs in two sets of middle and high schools with similar student populations. In one set of schools, students “beat the odds” and outperform their peers on high stakes, standardized tests of English skills and read and write at high levels of proficiency. In the other set of schools, students perform more typically. Most of the schools in the study serve students from high poverty, big city neighborhoods. By comparing these two sets of classrooms, we have been able to identify and validate six features of instruction that make a difference in student performance.

It is important to understand that the six features identified in this research are interrelated and supportive of one another. The higher performing schools exhibit all six characteristics. As you read the classroom examples, you will see that elements of all features can be found in each. Although addressing one feature may bring about improved student performance, it is the integration of all the features that will effect the most improvement.

What does that mean?

Teachers in the more effective programs use a variety of different teaching approaches based on student need. For example, if students need to learn a particular skill, item, or rule, the teacher might choose a separated activity to highlight it. Students would study the information as an independent lesson, exercise or drill without considering its larger meaning or use (e.g., they might be asked to copy definitions of literary terms into their notebooks and to memorize them).

To give students practice, teachers prepare or find simulated activities that ask students to apply concepts and rules within a targeted unit of reading, writing, or oral language. Students are expected to read or write short units of text with the primary purpose of practicing the skill or concept. Often students are asked to find examples of that skill in use in their literature and writing books, as well as in out-of-school activities. (For example, a teacher might ask students to identify examples of literary devices within a particular selection, or to write their own examples of these devices.)

To help students bring together their skills and knowledge within the context of a purposeful activity, teachers use integrated activities. These require students to use their skills or knowledge to complete a task or project that has meaning for them. (For example, in discussing a work or works of literature, students might be asked to consider how a writer’s use of literary devices affects a reader’s response to the piece.)

Teachers of the higher performing students use all three of these approaches. They don’t use them in any linear sequence or in equal amount, but they use them as they are needed to help students become aware of and learn to use particular skills and knowledge. It is the combination of all three approaches, based on what the students need, that appears to make the difference. Separated and simulated activities provide ways for teachers to “mark” a skill or item of information for future use. Integrated activities provide ways for students to put their understandings to use in the context of larger and more meaningful activities.

In more typically performing schools, teachers often rely on one strategy, missing opportunities to strengthen instruction and to integrate it across lessons and throughout the year.

Some activities that work

- Offering separated and simulated activities to individuals, groups, or the entire class as needed

- Providing overt, targeted instruction and review as models for peer and self-evaluation

- Teaching skills, mechanics, or vocabulary that can be used during integrated activities such as literature discussions

- Using all three kinds of instruction to scaffold ways to think and discuss (e.g., summarizing, justifying answers, and making connections)

What doesn’t work

- Reliance upon any one approach to the exclusion of the other two

- Focus on separated and/or simulated activities with no integration with the larger goals of the curriculum

Classroom example

At Reuben Dario Middle School in Florida, Gail Slatko uses all three approaches to empower her students to be better readers, writers, and editors. For example, she often teaches vocabulary skills within the context of literature and writing, but she also asks students to complete practice workbook exercises designed to increase their vocabularies. And they create “living dictionaries” by collecting new words as they come across them in books, magazines, and newspapers.

To provide practice with analogies, Gail goes beyond merely providing examples: she requires that students discuss their responses and explain the rationales for their answers. Later, students design vocabulary mobiles that she displays in the classroom. Gail uses the same approach when she targets literary concepts, conventions, and language. Students integrate literary and vocabulary learning when they create children’s books. These books incorporate vocabulary, alliteration, and story telling through words and pictures.

During one recent school year, five books were entered in the county fair competition, and one of them was awarded first prize. Gail’s lessons are models for her students to use in their own reading and writing as well as when they are editing and responding to the writing of their classmates.

In higher performing schools, the knowledge and skills for performing well on high stakes tests are made overt to both teachers and students. Teachers, principals and district-level coordinators often create working groups of professionals who collaboratively study the demands of the high stakes tests their students will take. They even take the tests themselves to identify the skills and knowledge required to do well. They discuss how these demands relate to district and state standards and expectations as well as to their curriculum, and then they discuss ways to integrate these skills into the curriculum. This reflection helps teachers understand the demands of the test, consider how these demands relate to their current practice, and plan ways to integrate the necessary skills and knowledge into the curriculum, across grades and school years. This process helps them move the focus of test preparation from practice on the surface features of the test itself to the knowledge that underlies successful learning and achievement in literacy and English.

In addition, students learn to become reflective about their own reading and writing performance. Teachers provide students with ways to read, understand, and write in order to gain the abilities that are necessary for being highly literate for life, not merely for passing a test. Both students and teachers internalize the criteria for good performance, and students understand the purposes for and the requirements of the tests.

In more typically performing schools, teachers rely on more traditional approaches to test preparation. If preparation is done at all, it is inserted as a separate activity rather than integrated into the ongoing curriculum. The focus tends to be on how to take the test rather than on the underlying knowledge and skills necessary for success. Teachers give students old editions of the test, make their own practice tests using activities that mirror the test-at-hand, and sometimes use commercial materials with similar formats and questions. Preparation is often done one or two weeks (or more) before the exam, or the preparation is sporadic and unconnected across long periods of time. Students often do not understand the purpose of the test, nor what they can do to improve their performance.

Using district and state standards and goals, teachers and administrators work together to:

- analyze the demands of a test

- identify connections to the standards and goals

- design and align curriculum to meet the demands of the test

- develop instructional strategies that enable students to build necessary skills

- ensure that skills are learned across the year and across grades

- make overt connections between and among instructional strategies, tests, and current learning

- develop and implement model lessons that integrate test preparation into the curriculum

- Short-term test preparation

- Test preparation that focuses on how to take the test

- Separate rather than integrate test preparation experiences

When the Florida Writes! test was instituted, the Dade County English Language Arts central office staff and some teachers met to study and understand the exam and the kinds of demands it would make on students. They saw where the skills and knowledge required by the test related to state and district standards and their existing curriculum, and they identified areas that needed to be systematically addressed. Together, they developed curriculum guides that would create year-long experiences in different types of writing, including the kinds of organization, elaboration, and polishing required for each. This coordination began some years before our study of the programs in Dade County, and the instructional changes that had led to greater coherence were very evident in the classrooms we studied.

Today classes across the county are replete with rich and demanding writing experiences. For example, Karis MacDonnell at Reuben Dario Middle School has her students think about writing prompts throughout the year. She wants them to understand how prompts are developed and how to best respond to them. In one lesson she has students study a prompt and identify its parts. The students identify the topic, the question, and the task (e.g., explanation, description).

Next she asks them to develop their own prompts for an essay about a book they have read. Before setting the students to work, Karis provides models she has created. As students complete their prompts in class, they bring them to her, and she reviews them to be sure that they contain the required parts and that they will help students to focus their ideas. Students then write essays based on these prompts. Thus she helps students gain not only skills necessary for the Florida Writes! test, but also skills that will support all of their writing.

In the higher performing schools, teachers work consciously to weave a web of connections within lessons, across lessons, and to students’ lives in and out of school. They make connections throughout each day, week, and year. And they point out these connections so that students can see how the skills and knowledge they are gaining can be used productively in a range of situations. In these schools, teachers also work together to redevelop and redesign curriculum. They share ideas and reflect upon their work.

In the more typical schools, even when lessons are integrated within a unit, students experience little interweaving across lessons; few overt connections are made among the content, knowledge, and skills being taught. Class lessons are often treated as separate wholes — with a particular focus introduced, practiced, discussed, and then put aside. Some teachers encourage students to make connections, but when classroom discussions are carefully controlled, the teacher predetermines the associations the students will make. Rather than encouraging students to find their own connections — or showing them how to do so — teachers guide them to guess the connections the teacher has already made. In addition, teachers tend to work as individuals rather than as cooperative colleagues; an overall plan linking the various parts of the curriculum is often absent.

In the higher performing schools and districts, decisions concerning professional development are also based upon their relationship to the whole program and their connections to student needs and curricular goals established by teachers and administrators. Teachers often have a voice in planning and implementing professional development activities, and, because these activities relate to the program and teachers can see how they relate, new ideas and concepts presented through them are often integrated into curriculum and instruction.

In more typical schools and districts, when professional development materials and workshops are selected, teachers are rarely consulted, and there may be no attempt to integrate the activities into ongoing aspects of the existing program. Often, when educators gain information and ideas from such experiences, they do not use them fully; they select some parts and ignore other, necessary elements, thus diminishing their effectiveness.

- Making overt connections between and across the curriculum, students’ lives, literature, and literacy

- Planning lessons that connect with each other, with test demands, and with students’ growing knowledge and skills

- Developing goals and strategies that meet students’ needs and are intrinsically connected to the larger curriculum

- Weaving even unexpected intrusions into integrated experiences for students

- Selecting professional development activities that are related to the school’s standards and curriculum framework

- Isolated lessons

- Lessons that leave connections implicit

- Lack of follow-through on curricular goals by teachers and/or administrators

- Selection of materials not connected to curricular goals

- Professional development activities unrelated to goals or curriculum

- Separated and isolated rather than integrated use of materials

When Shawn DeNight at Miami Edison High School learned about an unanticipated grade-wide field trip to a senior citizen center, he turned it into an advantage rather than an interruption to instruction. He used the trip to connect to and further one of his instructional goals. He had intended to have his students write a character analysis based on class literature readings.

Instead, he used the trip as a basis for a research project in which each student met and interviewed a senior citizen and then used this information to develop a persuasive essay. He titled the visit “An Intergenerational Forum: Senior Citizens and Teens Discuss What It Means to Be a Liberal or Conservative.” In preparation for the interview, students developed questions that would get at the person’s thoughts and beliefs (e.g., Do you think men and women should have the same privileges?).

Each student interviewed one person, collected responses to the questions, and then planned and wrote the essay, drawing on the interview for evidence that a person was liberal, conservative, or moderate. This activity then became practice for future character analysis while reading Romeo and Juliet .

It is important for students to learn not only subject matter content, but also how to think about, approach, and do their work in each subject. In higher performing schools, teachers divide new or difficult tasks into segments and provide their students with guides for accomplishing them. However, the help they offer is not merely procedural: They guide students through the process and overtly teach the steps necessary to do well. They provide strategies not only for how to do the task but also how to think about it. These strategies are discussed and modeled, and teachers develop reminder sheets for student to use. In this way, students learn the process for completing an assignment successfully.

Most of the teachers in the higher performing schools share and discuss rubrics for evaluating performance with their students. They also incorporate rubrics into their ongoing instruction as a way to help students develop an understanding of the components that contribute to a higher score. Discussion of the rubric expectations enables students to develop more complete, more elaborate, and more highly organized responses to an assignment. Sometimes students design a rubric with their teacher so that they clearly understand what is expected of them.

In higher performing schools, students learn and internalize ways to work through a task, and to understand and meet its demands. Through these experiences, they not only become familiar with strategies they can use to approach other tasks, including high stakes tests, but they also develop ways to think and work within a specific field. Teachers scaffold students’ thinking by developing complex activities and by asking questions that make the students look more deeply and more critically at the content of lessons.

In more typical schools, instruction focuses on content or skills rather than on the process of learning. Students do not develop the procedural and/or metacognitive strategies necessary to complete tasks independently. Teachers concentrate on covering the required information, focusing on the answer rather than on how to get to the answer. Students are not helped to internalize the methods and strategies for accomplishing tasks.

- Providing rubrics that students review, use, and even develop

- Designing models and guides that lead students to understand how to approach each task

- Supplying prompts that support thinking

- Focus on skills and content

- Instructions that lack procedural strategies to support and extend thinking

Kate McFadden-Midby at Foshay Learning Center in California provides her students with strategies for completing any task that she thinks is going to be new or challenging for them. For example, early in the year she provides strategies for group participation. She assigns specific roles that help students include important concepts and encourage participation of all members. The roles rotate, and students become comfortable filling all of them.

Many subsequent assignments require the application of these collaborative strategies. For example, when her students are learning character analyses, Kate asks them to begin by developing critical thinking questions. She tells them that the questions must be ones that anyone could discuss, even someone who has not read the book (e.g., one student asked, “Why are some people so cruel when it comes to revenge?”).

Before students meet with their groups, she provides these directions:

- share your critical thinking question with your group;

- tell your group partners why you chose that particular question and what situation in the book made you think about it.

Next, she asks the students to choose two characters from the book (or books) they have read, in order to compare the characters’ viewpoints on that question. The students engage in deep and substantive discussion about their classmates’ questions, and in so doing gain clarity on the goals and process of the task. As students work to develop their questions, they are applying their group strategies as well as developing ways to analyze characters.

These group discussions are followed by a pre-writing activity in preparation for writing a description of the characters they choose. Kate instructs them on how to develop a T-Chart. One character’s name is placed at the top of one column of the T, and the other character’s name at the top of the other. She asks them to list characteristics: what their characters were like, experiences they had, opinions, etc. By using this chart, Kate provides the students with a way to identify characteristics and then ways to compare them across characters.

Students again meet with their groups and present their characters. Kate scaffolds the students’ thinking by asking questions about the characters: What kind of person was the mother? What are some adjectives that might describe her? How do you think those things could influence how she feels?

Over time, they will use the T-Chart as an organizational strategy in several writing assignments, and Kate will introduce them to a variety of other supportive strategies. Although her assignments are complex, her students can be successful because Kate provides helpful strategies along the way. They gain insight not merely into specific content (e.g., the characters of the lessons above), but also into how to do the assigned work and how they can apply these tools in other learning situations.

All of the teachers in the higher performing schools take a generative approach to student learning. They go beyond students’ acquisition of skills or knowledge to engage students in creative and critical uses of their knowledge and skills. Teachers provide a variety of activities from which students will generate deeper understandings.

For example, when studying literature, after the more obvious themes in a text are discussed, teachers and students together explore the text from many points of view, both from within the literary work and from life. Students may be asked to research the time period, to consider how issues in the piece relate to current issues, or to compare the treatment of issues in this literary work with the treatment of the same issues in other pieces they have read. Teachers are attuned to questions raised by the students and use the students’ concerns as opportunities to further elaborate and generate meaning. Once students arrive at a level of expertise, teachers continue to provide an array of activities that provoke them to use what they have learned to think and learn more.

In contrast, in the more typical schools, the learning activity and the thinking about it seem to stop when the desired response is given or when the assigned task is completed. When students appear confused or uncertain, teachers will often give them the “right” answer and move on to the next activity rather than capitalize on the opportunity to provoke further study and probing of the issue. The learning consists more of a superficial recall of names, definitions, and facts than a deeper and more highly conceptualized learning.

- Exploring texts from many points of view (e.g., social, historical, ethical, political, personal)

- Extending literary understanding beyond initial interpretations

- Researching and discussing issues generated by literary texts and by student concerns

- Extending research questions beyond their original focus

- Developing ideas in writing that go beyond the superficial

- Writing from different points of view

- Designing follow-up lessons that cause students to move beyond their initial thinking

- Stopping once students have demonstrated understanding