- Program Design

- Peer Mentors

- Excelling in Graduate School

- Oral Communication

- Written communication

- About Climb

Creating a 10-15 Minute Scientific Presentation

In the course of your career as a scientist, you will be asked to give brief presentations -- to colleagues, lab groups, and in other venues. We have put together a series of short videos to help you organize and deliver a crisp 10-15 minute scientific presentation.

First is a two part set of videos that walks you through organizing a presentation.

Part 1 - Creating an Introduction for a 10-15 Minute Scientfic Presentation

Part 2 - Creating the Body of a 10-15 Minute Presentation: Design/Methods; Data Results, Conclusions

Two additional videos should prove useful:

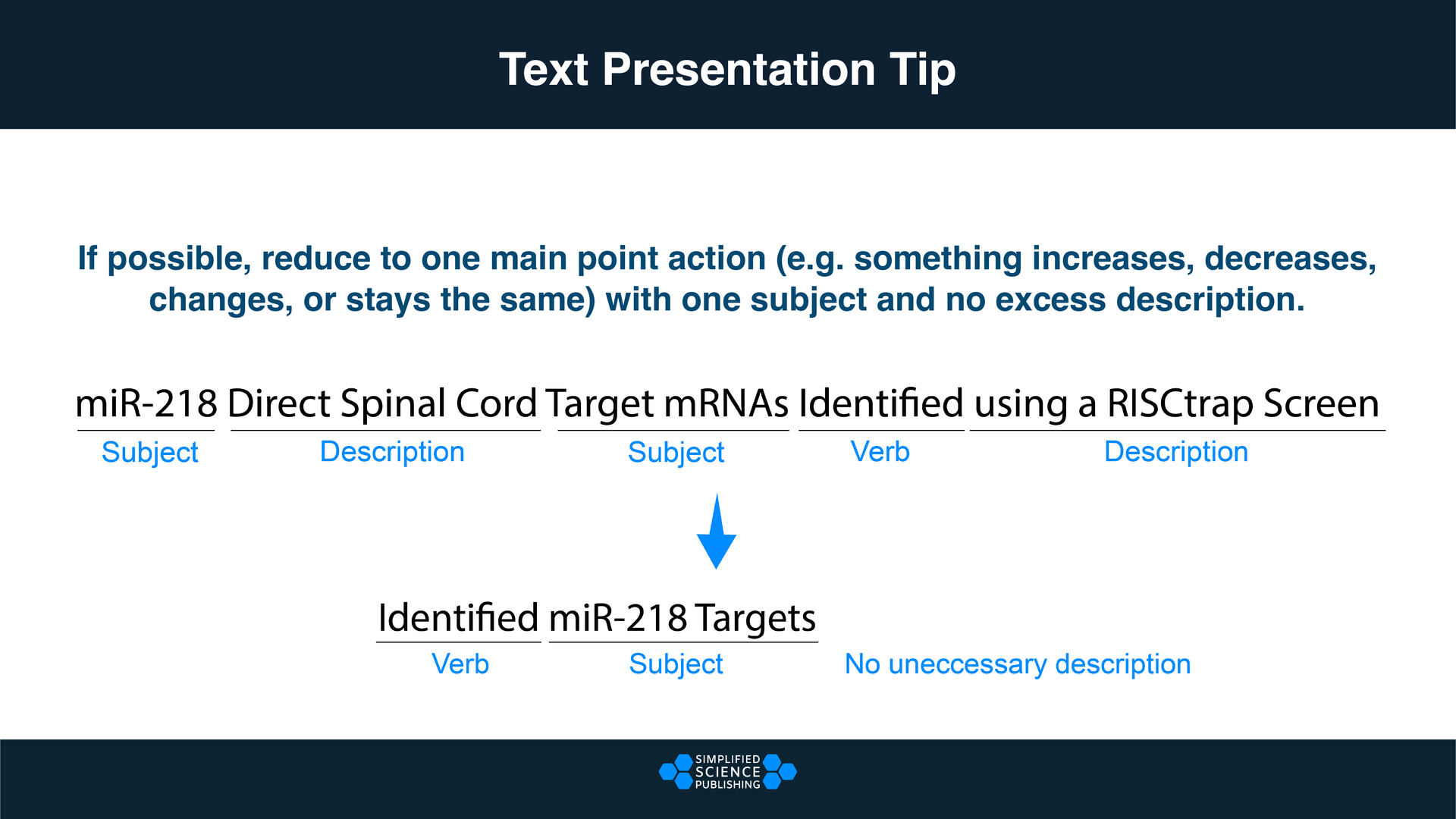

Designing PowerPoint Slides for a Scientific Presentation walks you through the key principles in designing powerful, easy to read slides.

Delivering a Presentation provides tips and approaches to help you put your best foot forward when you stand up in front of a group.

Other resources include:

Quick Links

Northwestern bioscience programs.

- Biomedical Engineering (BME)

- Chemical and Biological Engineering (ChBE)

- Driskill Graduate Program in the Life Sciences (DGP)

- Interdepartmental Biological Sciences (IBiS)

- Northwestern University Interdepartmental Neuroscience (NUIN)

- Campus Emergency Information

- Contact Northwestern University

- Report an Accessibility Issue

- University Policies

- Northwestern Home

- Northwestern Calendar: PlanIt Purple

- Northwestern Search

Chicago: 420 East Superior Street, Rubloff 6-644, Chicago, IL 60611 312-503-8286

Get in touch

555-555-5555

Limited time offer: 20% off all templates ➞

Scientific Presentation Guide: How to Create an Engaging Research Talk

Creating an effective scientific presentation requires developing clear talking points and slide designs that highlight your most important research results..

Scientific presentations are detailed talks that showcase a research project or analysis results. This comprehensive guide reviews everything you need to know to give an engaging presentation for scientific conferences, lab meetings, and PhD thesis talks. From creating your presentation outline to designing effective slides, the tips in this article will give you the tools you need to impress your scientific peers and superiors.

Step 1. Create a Presentation Outline

The first step to giving a good scientific talk is to create a presentation outline that engages the audience at the start of the talk, highlights only 3-5 main points of your research, and then ends with a clear take-home message. Creating an outline ensures that the overall talk storyline is clear and will save you time when you start to design your slides.

Engage Your Audience

The first part of your presentation outline should contain slide ideas that will gain your audience's attention. Below are a few recommendations for slides that engage your audience at the start of the talk:

- Create a slide that makes connects your data or presentation information to a shared purpose, such as relevance to solving a medical problem or fundamental question in your field of research

- Create slides that ask and invite questions

- Use humor or entertainment

Identify Clear Main Points

After writing down your engagement ideas, the next step is to list the main points that will become the outline slide for your presentation. A great way to accomplish this is to set a timer for five minutes and write down all of the main points and results or your research that you want to discuss in the talk. When the time is up, review the points and select no more than three to five main points that create your talk outline. Limiting the amount of information you share goes a long way in maintaining audience engagement and understanding.

Create a Take-Home Message

And finally, you should brainstorm a single take-home message that makes the most important main point stand out. This is the one idea that you want people to remember or to take action on after your talk. This can be your core research discovery or the next steps that will move the project forward.

Step 2. Choose a Professional Slide Theme

After you have a good presentation outline, the next step is to choose your slide colors and create a theme. Good slide themes use between two to four main colors that are accessible to people with color vision deficiencies. Read this article to learn more about choosing the best scientific color palettes .

You can also choose templates that already have an accessible color scheme. However, be aware that many PowerPoint templates that are available online are too cheesy for a scientific audience. Below options to download professional scientific slide templates that are designed specifically for academic conferences, research talks, and graduate thesis defenses.

Step 3. Design Your Slides

Designing good slides is essential to maintaining audience interest during your scientific talk. Follow these four best practices for designing your slides:

- Keep it simple: limit the amount of information you show on each slide

- Use images and illustrations that clearly show the main points with very little text.

- Read this article to see research slide example designs for inspiration

- When you are using text, try to reduce the scientific jargon that is unnecessary. Text on research talk slides needs to be much more simple than the text used in scientific publications (see example below).

- Use appear/disappear animations to break up the details into smaller digestible bites

- Sign up for the free presentation design course to learn PowerPoint animation tricks

Scientific Presentation Design Summary

All of the examples and tips described in this article will help you create impressive scientific presentations. Below is the summary of how to give an engaging talk that will earn respect from your scientific community.

Step 1. Draft Presentation Outline. Create a presentation outline that clearly highlights the main point of your research. Make sure to start your talk outline with ideas to engage your audience and end your talk with a clear take-home message.

Step 2. Choose Slide Theme. Use a slide template or theme that looks professional, best represents your data, and matches your audience's expectations. Do not use slides that are too plain or too cheesy.

Step 3. Design Engaging Slides. Effective presentation slide designs use clear data visualizations and limits the amount of information that is added to each slide.

And a final tip is to practice your presentation so that you can refine your talking points. This way you will also know how long it will take you to cover the most essential information on your slides. Thank you for choosing Simplified Science Publishing as your science communication resource and good luck with your presentations!

Interested in free design templates and training?

Explore scientific illustration templates and courses by creating a Simplified Science Publishing Log In. Whether you are new to data visualization design or have some experience, these resources will improve your ability to use both basic and advanced design tools.

Interested in reading more articles on scientific design? Learn more below:

Data Storytelling Techniques: How to Tell a Great Data Story in 4 Steps

Best Science PowerPoint Templates and Slide Design Examples

Free Research Poster Templates and Tutorials

Content is protected by Copyright license. Website visitors are welcome to share images and articles, however they must include the Simplified Science Publishing URL source link when shared. Thank you!

Online Courses

Stay up-to-date for new simplified science courses, subscribe to our newsletter.

Thank you for signing up!

You have been added to the emailing list and will only recieve updates when there are new courses or templates added to the website.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience and we do not sell data. By using this website, you are giving your consent for us to set cookies: View Privacy Policy

Simplified Science Publishing, LLC

This website uses cookies to improve your user experience. By continuing to use the site, you are accepting our use of cookies. Read the ACS privacy policy.

- ACS Publications

10 Keys to an Engaging Scientific Presentation

- May 31, 2018

What makes an engaging scientific presentation? Georgia Tech Professor Will Ratcliff uses a method based on the style of nature documentary presenter David Attenborough. Ratcliff’s approach looks to capture an audience’s natural curiosity by using engaging visuals and simple storytelling techniques. Here are his 10 keys to an engaging scientific presentation: 1) Be an Entertainer First: […]

What makes an engaging scientific presentation? Georgia Tech Professor Will Ratcliff uses a method based on the style of nature documentary presenter David Attenborough. Ratcliff’s approach looks to capture an audience’s natural curiosity by using engaging visuals and simple storytelling techniques.

Here are his 10 keys to an engaging scientific presentation:

1) Be an Entertainer First : Before your science can wow your audience, they have to understand it. Before they can understand it, you must engage them with what you’re saying. Look at your presentation from your audience’s perspective and think about how they’ll relate to your material. Focus on presenting your science in a way that engages and entertains as it explains.

2) Be a Storyteller, Not a Lecturer : Don’t assume that your audience knows your field. Tell the story of your science: identify the big picture backdrop, your specific research questions, how you answer those questions, and how it affects the way we now think about the big picture.

3) Prioritize Clarity : If the audience doesn’t understand every word you use, they’ll stop paying attention, and you may never win them back. Your goal is to never lose their attention in the first place, so make an effort to be clear and have a simple narrative arc to your talk.

4) Mind Your Transitions: The easiest place to lose your audience’s focus is when you move from one slide to another. Practice the transitions in your talk to make sure the link between the ideas of one slide and the next remains clear.

5) Keep Complete Sentences Out of Your Slides: Keep the text in your slides to a minimum. Instead, use compelling visual to hold your audience’s attention while you speak.

6) Animations Are Your Friend: You can use animations to reveal new details on your slide as they become relevant to what you are saying. That way you get to control what your audience is seeing, minimizing distraction and putting laser pointers out of a job. Note: never use silly and unnecessary animations, like spinning or scrolling text, this will just annoy your audience.

7) Get Excited: If you’re not excited and energetic about your work, your audience won’t be either.

8) Look at the Audience: Don’t stare at the floor, the ceiling, or your slides while you’re presenting. Look directly at your audience, or if you’re nervous, toward the back of the lecture hall. This will help you connect with your audience.

9) Be Wary of Jokes: Scientific talks are serious by nature and you have more to lose than to gain. If a joke is poorly timed or if you misjudge an audience, you risk alienating them. Play it safe and find other ways to be entertaining unless you know your audience well.

10) Leave the Laser Pointer at Home: Laser pointers are distracting. If you feel you need one to guide your audience through a slide, that’s a sign your slide is too cluttered.

Want More Tips on Giving an Engaging Scientific Presentation? Check Out: 3 Elements of a Great Scientific Talk

Want the latest stories delivered to your inbox each month.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

5 tips for giving a good scientific presentation

What is a scientific presentation?

What is the objective of a scientific presentation, why is giving scientific presentations necessary, how to give a scientific presentation, tip 1: prepare during the days leading up to your talk, tip 2: deal with presentation nerves by practicing simple exercises, tip 3: deliver your talk with intention, tip 4: be adaptable and willing to adjust your presentation, tip 5: conclude your talk and manage questions confidently, concluding thoughts, other sources to help you give a good scientific presentation, frequently asked questions about giving scientific presentations, related articles.

You have made the slides for your scientific presentation. Now, you need to prepare to deliver your talk. But, giving an oral scientific presentation can be nerve-wracking. How do you ensure that you deliver your talk well, and leave a good impression on the audience?

Mastering the skill of giving a good scientific presentation will stand you in good stead for the rest of your career, as it may lead to new collaborations or even new employment opportunities.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to give a good oral scientific presentation, including

- Why giving scientific presentations is important for your career;

- How to prepare before giving a scientific presentation;

- How to keep the audience engaged and deliver your talk with confidence.

The following tips are a product of our research into the literature on giving scientific presentations as well as our own experiences as scientists in giving and attending talks. We advise on how to make a scientific presentation in another post.

A scientific presentation is a talk or poster where you describe the findings of your research to others. An oral presentation usually involves presenting slides to an audience. You may give an oral scientific presentation at a conference, give an invited seminar at another institution, or give a talk as part of an interview. A PhD thesis defense is one type of scientific presentation.

➡️ Read about how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The objective of a scientific presentation is to communicate the science such that the audience:

- Learns something new;

- Leaves with a clear understanding of the key message of your research;

- Has confidence in you and your work;

- Remembers you afterward for the right reasons.

As a scientist, one of your responsibilities is disseminating your scientific knowledge by giving presentations. Communicating your research to others is an altruistic act, as it is an opportunity to teach others about your research findings, and the knowledge you have gained while researching your topic.

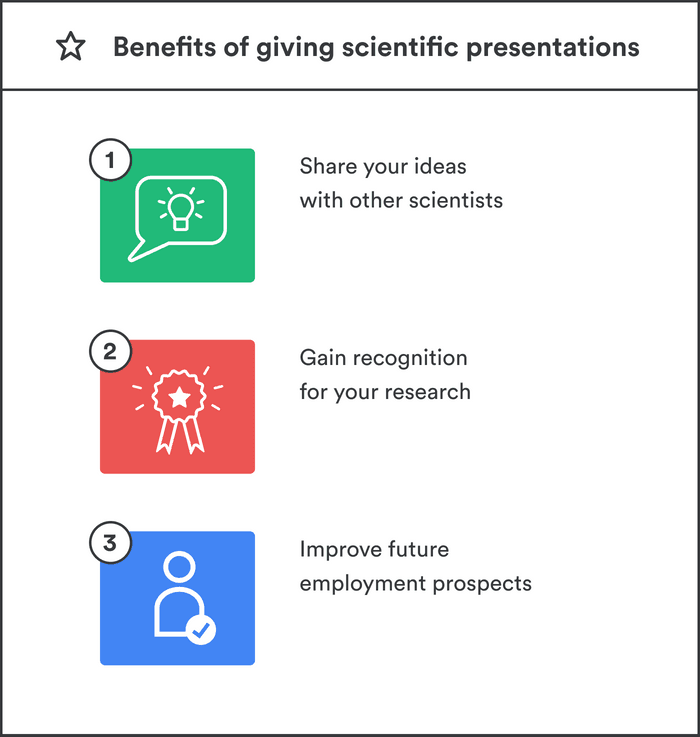

Giving scientific presentations confers many career benefits , such as:

- Having the opportunity to share your ideas and to have insightful conversations with other scientists. For example, a thoughtful question may create a new direction for your research.

- Gaining recognition for your work and generating excitement for your research program can help you to forge new collaborations and to obtain more citations of your papers. It's your chance to impress some of the biggest names in your field, build your reputation as a scientist, and get more people interested in your work.

- Improving your future employment prospects by getting presentation experience in high-stakes settings and by having talks listed on your academic CV.

➡️ Learn how to write an academic CV

You might have just 10 minutes for your talk. But those 10 minutes are your golden ticket. To make them shine, you'll need to put in some homework. You need to think about the story you want to tell , create engaging slides , and practice how you're going to deliver it.

Why all this effort? Because the rewards are potentially huge. Imagine speaking to the top names in your field, boosting your visibility, and getting more eyes on your work. It's more than just a talk; it's your chance to showcase who you are and what you do.

Here we share 5 tips for giving effective scientific presentations.

- Prepare adequately for your talk on the days leading up to it

- Deal with presentation nerves

- Deliver your talk with intention

- Be adaptable

- Conclude your talk with confidence

You should prepare for your talk with the seriousness it deserves and recognize the potential it holds for your career advancement. Here are our suggestions:

- Rehearse your talk multiple times to ensure smooth flow. Know the order of your slides and key transitions without memorizing every word. Practice your speech as though you are discussing with friendly and attentive listeners.

- Record your speech and listen back to yourself giving your talk while doing household chores or while going for a walk. This will help you remember the important points of your talk and feel more comfortable with the flow of it on the day.

- Anticipate potential questions that may arise during your talk, write down your responses to those questions, and practice them aloud.

- Back up your presentation in cloud storage and on a USB key. Bring your laptop with you on the day of your talk, if needed.

- Know the time and location of your talk. Familiarize yourself with the room, if you can. Introduce yourself to the moderator before the session begins.

- Giving a talk is a performance, so preparing yourself physically and mentally is essential. Prioritize good sleep and hydration, and eat healthy, nourishing food on the day of your talk. Plan your attire to be both professional and comfortable.

It’s natural to feel nervous before your talk, but you want to harness that energy to present your work with confidence. Here are some ways to manage your stress levels:

- Remember that your audience want to listen to you and learn from you. Believe that your audience will be kind, friendly, and interested, rather than bored and skeptical.

- Breathing slow and deep before your talk calms the mind and nervous system. Psychologist Amy Cuddy recommends practicing open, confident postures while sitting and standing to help you get into a positive frame of mind.

- Fight off impostor syndrome with positive affirmations. You’ve got this! Remember that you know more about your research than anyone else in the room and you are giving your talk to teach others about it.

Giving your talk with confidence is crucial for your credibility as a scientist. Focusing on your delivery helps ensure that your audience remembers and believes what you say. Here are some techniques to try:

- Before beginning, remember your professional goals and the benefits of giving your presentation. Start with a smile and exhale deeply.

- Memorize a simple opening. After the moderator introduces you, pause and take a breath. Welcome the audience, thank them for coming, and introduce yourself. You don’t need to read the title of your talk. But briefly, say something like, “today I’m going to talk to you about why [topic] is important and [what I hope you will learn from this talk]” in 1-2 sentences. Preparing your opening will settle your nerves and prevent you from starting your talk on a tangential topic, ensuring you stay on time.

- Project confidence outwardly, even if you feel nervous. Stand up tall with your shoulders back and make eye contact with individuals in the audience. Move your focus around the room, so everyone in the audience feels included.

- Maintain open body language and face the audience as much as possible, not your slides.

- Project your voice as much as you can so that people at the back of the room can hear you. Enunciate your words, avoid mumbling, and don’t trail off awkwardly.

- Varying your vocal delivery and intonation will make your talk more interesting and help the audience pay attention, particularly when you want to emphasize key points or transitions.

- Pausing for dramatic effect at crucial moments can help you relax and remember your message, as well as being an effective engagement device.

- A laser pointer can be off-putting for the audience if you are prone to having a shaky hand when nervous. Use a laser pointer only to emphasize information on the slide while providing an explanation. If you design your slides thoughtfully , you won’t need to use a laser pointer.

Not all parts of your talk may go according to plan. Here are some ways to adapt to hitches during your talk:

- Handle talk disruptions gracefully. If you make a mistake, or a technical issue occurs during your talk, remember that it’s okay to skip something and move on without apologizing.

- If you forget to mention something but the audience hasn’t noticed, don’t point it out! They don’t need to know.

- As you give your talk, be time-conscious, and watch the moderator for signals that the time is about to expire. If you realize you won’t have time to discuss all your slides, skip the less important ones. Adjust your presentation on the fly to finish on time, prioritizing content as needed.

- If you run out of time completely, just stop. You don’t have to give a conclusion, but you do need to stop on time! Practicing your talk should prevent this situation.

The ending of your talk is important for emphasizing your key message and ensuring the audience leave with a positive impression of you and your work. Here are some pointers.

- Conclude your talk with a memorized closing statement that summarizes the key take-home message of your research. After making your closing statement, end your talk with a simple “Thank you”. Then pause and wait for the applause. You don’t need to ask if the audience has questions because the moderator will call for questions on your behalf.

- When you receive a question, pause, then repeat the question. This ensures the whole audience understands the question and gives you time to calmly consider your answer.

- In a talk on attaining confidence in your scientific presentations, Michael Alley suggests that if you don’t know the answer to the question, then emphasize what you do know. Say something like, “Although I can’t fully answer your question, I can say [this about the topic].”

- Approach the Q&A with interest rather than anxiety by reframing it as an opportunity to further share your knowledge. Being curious, instead of feeling fearful, can help you shine during what might be the most stressful part of your presentation.

Communicating your research effectively is a key skill for early career scientists to learn. Taking ample time to prepare and practice your presentation is an investment in your scientific development.

But here's the good part: all that effort pays off. Think of your talk as not just a presentation, but as a way to show off what you and your research are all about. Giving a compelling scientific presentation will raise your professional profile as a scientist, lead to more citations of your work, and may even help you obtain a future academic job.

But most importantly of all, giving talks contributes to science, and sharing your knowledge is an act of generosity to the scientific community.

➡️ Questions to ask yourself before you make your talk

➡️ How to give a great scientific talk

1) Have a positive mindset. To help with nerves, breathe deeply and keep in mind that you are an authority on your topic. 2) Be prepared. Have a short list of points for each slide and know the key transition points of your talk. Practice your talk to ensure it flows smoothly. 3) Be well-rested before your talk and eat a light meal on the day of your presentation. A talk is a performance. 4) Project your voice and vary your vocal intonation and pitch to retain the interest of the audience. Take pauses at key moments, for emphasis. 5) Anticipate questions that audience members could ask, and prepare answers for them.

The goal of a scientific presentation is that the audience remembers the key outcomes of your research and that they leave with a good impression of you and your science.

Take a moment to exhale deeply and collect your thoughts after the moderator has introduced you. Don’t read your talk's title. Instead, introduce yourself, thank the audience for attending, and provide a warm welcome. Then say something along the lines of, "Today I'm going to talk to you about why [topic] is important and [what I hope you will learn from this presentation].” A rehearsed opening will ensure that you start your talk on a confident note.

Prepare a memorable closing statement that emphasizes the key message of your talk. Then end with a simple “Thank you”.

Preparation is key. Practice many times to familiarize yourself with the content of your presentation. Before giving your talk, breathe slowly and deeply, and remind yourself that you are the expert on your topic. When giving your talk, stand up tall and use open body language. Remember to project your voice, and make eye contact with members of the audience.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER GUIDE

- 01 December 2021

How to tell a compelling story in scientific presentations

- Bruce Kirchoff 0

Bruce Kirchoff is a botanist and storyteller at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in North Carolina, USA. His new book is Presenting Science Concisely .

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Structuring your presentations with care can help you to clearly communicate to your audience. Credit: Getty

Scientific presentations are too often boring and ineffective. Their focus on techniques and data do not make it easy for the audience to understand the main point of the research.

If you want to reach beyond the narrow group of scientists who work in your specific area, you need to tell your audience members why they should be interested. Three things can help you to be engaging and convey the importance of your research to a wide audience. I had been teaching scientific communication for several years when I was approached to write a book about improving scientific presentations 1 . These are my three most important tips.

State your main finding in your title

The best titles get straight to the point. They tell the audience what you found, and they let them know what your talk will be about. Throughout this article, I will use titles from Nature papers published in the past two years as examples that will stand in for presentation titles. This is because Nature articles have a similar goal of attempting to make discipline-specific research available to a broader audience of scientists. Take, for example: ‘Supply chain diversity buffers cities against food shocks’ 2 .

A great title tells the reader exactly what’s new and precisely conveys the main result, as this one demonstrates. A more conventional title would have been ‘Effect of supply chain diversity on food shocks’, which omits the direction of the effect — so mainly scientists who are interested in your research area will be attracted to the talk. Others will wonder whether the talk will be a waste of time: maybe there was no effect at all.

Collection: Careers toolkit

Another example of a good title is: ‘Organic management promotes natural pest control through altered plant resistance to insects’ 3 .

This title ensures that the audience members know that the talk will be about the beneficial effects of organic crop management before they hear it. They also know that organic management increases plant resistance to insects. This title is much better than one such as: ‘Effects of organic pest management on plant insect resistance’. This title tells the audience the general area of the talk but does not give them the main result.

Finally, look at: ‘A highly magnetized and rapidly rotating white dwarf as small as the Moon’ 4 .

Good titles can just as easily be written for descriptive work as for experimental results. All you need to do is tell your audience what you found. Be as specific as possible. Compare this title with a more conventional one for the same work: ‘Use of the Zwicky Transient Facility to search for short period objects below the main white dwarf cooling sequence’. This title might be of interest to astronomers interested in using this facility, but is unlikely to attract anyone beyond them.

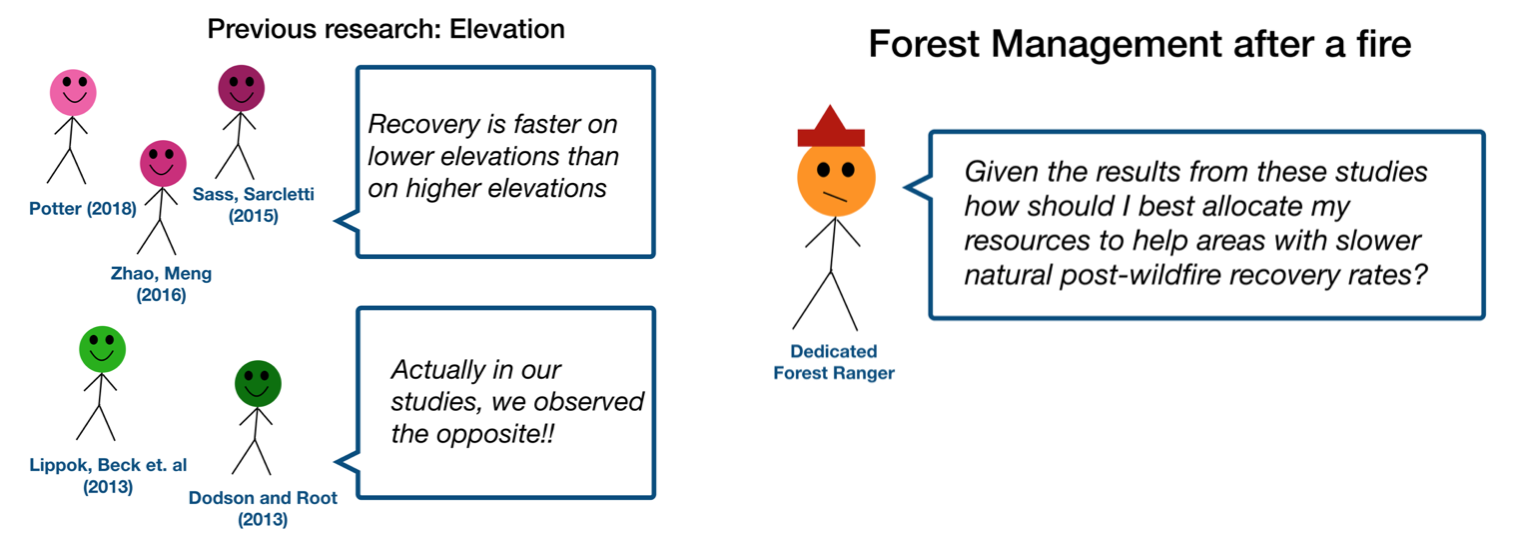

‘But’ is good — use it for dramatic effect

The contradiction implied by the word ‘but’ is one of the most powerful tools a scientist can use 5 . Contradictions introduce problems and provide dramatic effect, tension and a reason to keep listening.

Without such contradictions, the talk will consist of a bunch of results strung together in a seemingly endless and mind-numbing list. We can think of this list as a series of ‘and’ statements: “We did this and this and ran this experiment and found this result and . . . and . . . and.”

Contrast this with a structure that begins with a few important facts, tethered by ands, and then introduces the problem to be solved. Finally, ‘therefore’ can introduce results or subsequent actions. That structure would look like this: ‘X is the current state of knowledge, and we know Y. But Z problem remains. Therefore, we carried out ABC research.’ The introduction of even one contradiction wakes up people in the audience and helps them to focus on the results.

Collection: Conferences

A paper published earlier this year on SARS-CoV-2 and host protein synthesis provides an excellent example of the narrative form using ‘and’, ‘but’ and ‘therefore’ 6 . In the example below, I have shortened the abstract and simplified the transitions, but maintained the authors’ original structure 6 . Although they did not use ‘but’ or ‘therefore’ in their abstract, the existence of these terms is clearly implied. I have made them explicit in the following rendition.

“Coronaviruses have developed a variety of mechanisms to repress host messenger RNA translation and to allow the translation of viral mRNA and block the cellular immune response. But a comprehensive picture of the effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on cellular gene expression is lacking. Therefore, we combine RNA sequencing, ribosome profiling and metabolic labelling of newly synthesized RNA to comprehensively define the mechanisms that are used by SARS-CoV-2 to shut off cellular protein synthesis.”

In this example, background information is given in the first sentence, linked by a series of conjunctions. Then the problem is introduced — this is the contradiction that comes with ‘but’. The solution to this problem is given in the next sentence (and introduced by using ‘therefore’). This structure makes the text interesting. It will do the same for your presentations.

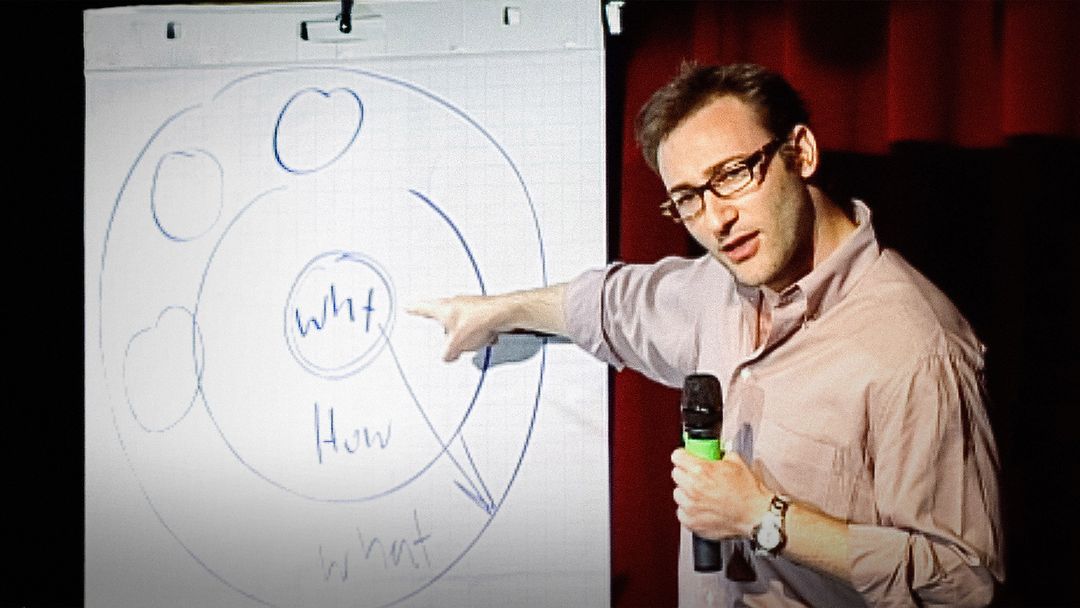

Use repeated problems and solutions to create a story

Use the power of contradiction to maintain audience engagement throughout your talk. You can string together a series of problems and solutions (buts and therefores) to create a story that leads to your main result. The result highlighted in your title will help you to focus your talk so that the solutions you present lead to this overarching result.

Here is the general pattern:

1. Present the first part of your results.

2. Introduce a problem that remains.

3. Provide a solution to this problem by presenting more results.

4. Introduce the next problem.

5. Present the results that address this problem.

6. Continue this ‘problem and solution’ process through your presentation.

7. End by restating your main finding and summarize how it arises from your intermediate results.

The SARS-CoV-2 abstract 6 uses this pattern of repeated problems (buts) and solutions (therefores). I have modified the wording to clarify these sections.

1. Result 1: SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to a global reduction in translation, but we found that viral transcripts are not preferentially translated.

2. Problem 1: How then does viral mRNA comes to dominate the mRNA pool?

3. Solution 1: Accelerated degradation of cytosolic cellular mRNAs facilitates viral takeover of the mRNA pool in infected cells.

4. Problem 2: How is the translation of induced transcripts affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection?

5. Solution 2: The translation of induced transcripts (including innate immune genes) is impaired.

6. Problem 3: How is translation impaired? What is the mechanism?

7. Solution 3: Impairment is probably mediated by inhibiting the export of nuclear mRNA from the nucleus, which prevents newly transcribed cellular mRNA from accessing ribosomes.

8. Final summary: Our results demonstrate a multipronged strategy used by SARS-CoV-2 to take over the translation machinery and suppress host defences.

Using these three basic tips, you can create engaging presentations that will hold the attention of your audience and help them to remember you. For young scientists, especially, that is the most important thing the audience can take away from your talk.

Nature 600 , S88-S89 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-03603-2

This article is part of Nature Events Guide , an editorially independent supplement. Advertisers have no influence over the content.

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Kirchoff, B. Presenting Science Concisely (CABI, 2021).

Google Scholar

Gomez, M., Mejia, A., Ruddell, B. L. & Rushforth, R. R. Nature 595 , 250–254 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Blundell, R. et al. Nature Plants 6 , 483–491 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Caiazzo, I. et al. Nature 595 , 39–42 (2021).

Olson, R. The Narrative Gym (Prairie Starfish Press, 2020).

Finkel, Y. et al. Nature 594 , 240–245 (2021).

Download references

Competing Interests

B.K. receives royalties for his book, which this article is based on.

Related Articles

Partner content: Scientific Conferences to fuel new ideas and the next generation of scientists

Partner content: Wellcome Connecting Science: A global provider of genomics learning and training

- Conferences and meetings

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Career Feature 15 MAY 24

How I fled bombed Aleppo to continue my career in science

Career Feature 08 MAY 24

Illuminating ‘the ugly side of science’: fresh incentives for reporting negative results

Hunger on campus: why US PhD students are fighting over food

Career Feature 03 MAY 24

China promises more money for science in 2024

News 08 MAR 24

One-third of Indian STEM conferences have no women

News 15 NOV 23

How remote conferencing broadened my horizons and opened career paths

Career Column 04 AUG 23

Research Associate - Metabolism

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoc Fellowships

Train with world-renowned cancer researchers at NIH? Consider joining the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) at the National Cancer Institute

Bethesda, Maryland

NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Faculty Recruitment, Westlake University School of Medicine

Faculty positions are open at four distinct ranks: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Full Professor, and Chair Professor.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

PhD/master's Candidate

PhD/master's Candidate Graduate School of Frontier Science Initiative, Kanazawa University is seeking candidates for PhD and master's students i...

Kanazawa University

Senior Research Assistant in Human Immunology (wet lab)

Senior Research Scientist in Human Immunology, high-dimensional (40+) cytometry, ICS and automated robotic platforms.

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston University Atomic Lab

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Enterprise Custom Courses

- Build Your Own Courses

- Help Center

- Clinical Trial Recruitment

- Pharmaceutical Marketing

- Health Department Resources

- Patient Education

- Research Presentation

- Remote Monitoring

- Health Literacy & SciComm

- Student Education & Higher Ed

- Individual Learning

- Member Directory

- Community Chats on Slack

- SciComm Program

- The Story-Driven Method

- The Instructional Method

How to Create an Engaging Science Presentation: A Quick Guide

We’ve all been there – rushing to put slides together for an upcoming talk, filling them with bullet points and text that we want to remember to cover. We aren’t sure exactly what the audience will want to know or how much detail to include, so we default to putting ALL the details in that might be needed. But such efforts often result in presentations that are too long, too confusing, and difficult for both ourselves and our audiences to navigate.

Today I gave a workshop to public health graduate students about how to create more engaging science presentations and talks. I’ve summarized the main takeaways below. I hope this quick guide will be useful to you as you prepare for your next science talk or presentation!

The best science talks start with a process of simplifying – peeling back the layers of information and detail to get at the one core idea that you want to communicate. Over the course of your talk, you may present 2-3 key messages that relate to, demonstrate, provide examples of or underpin this idea. (Three is a nice round number of messages or takeaways that your audience will be able to remember!) But stick to one big idea. Trying to communicate too much in a presentation or talk will overwhelm your audience, and they may walk away without a good memory of any of the ideas you presented.

Once you’ve settled on your one big idea, you can develop a theme that will pervade every aspect of your talk. This theme might be a defining element of your big idea and something that can tie all of your data or talking points together. Your theme should inform the examples, anecdotes and analogies that you use to make the science concepts you present more accessible. It should also inform your slides’ very design – the colors, visuals, layout and content flow.

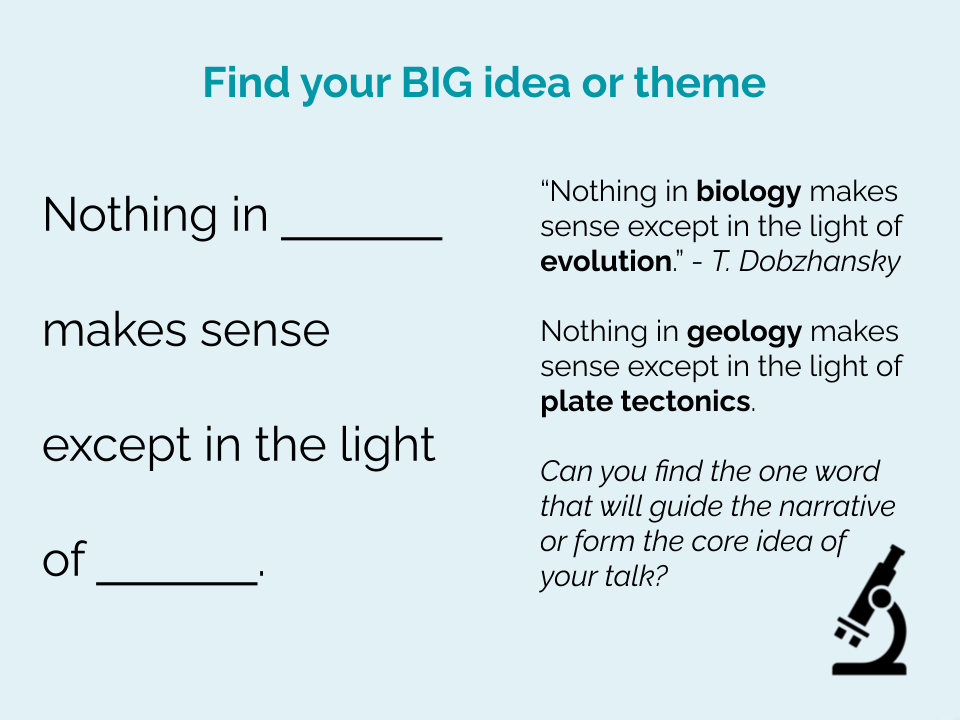

If you have trouble identifying your big idea and your theme, you can try using what scientist and science author Randy Olson calls the “Dobzhansky Template.” Fill in the blanks of this statement: “ Nothing in [your talk topic, research topic or big idea] makes sense, except in the light of [your theme!] .”

Here’s an example for you: “Nothing in the creation of engaging science talks makes sense except in the light of people’s need for personal connection .” With this statement, I’m identifying a key aspect, a unifying theme, for my talk (or blog post) on how to create engaging science talks. We all crave personal connection. Yes, even to the speakers of science talks we listen to! What does this mean in terms of what we want or expect from these speakers? It means we want storytelling . We want to hear their stories, know their background, hear about their struggles and triumphs! We want to be able to step into their shoes and see what they saw. We want to interact with them.

Tell a Story

Narratives engage more than facts. By telling a story , using suspense and characters to pull people through your presentation, you will capture and keep their attention for longer. People also remember information presented in a story format better than they do information presented as disparate facts or bullet points.

“Story is a pull strategy. If your story is good enough, people—of their own free will—come to the conclusion they can trust you and the message you bring.” – Annette Simmons

Storytelling is a powerful science communication tool. In storytelling, both the storyteller and the listener or reader contribute to the story’s meaning through their interpretations, feelings and emotions. Liz Neeley, former executive director of The Story Collider, once said: “Science communicators frequently fail to understand that a feeling is almost never conquered with a fact.”

Stories are exciting. They elicit emotions. They help foster a personal connection between the storyteller and the listener, and a connection between the listener and the topic, characters or ideas presented in the story.

But what IS a story? As humans, we excel at recognizing a story when we hear one, but defining a story’s key characteristics is more difficult than you might think. If you ask anyone to explain what makes for a good story, they likely will have a hard time explaining it.

In her fantastic book Wired for Story , Lisa Cron starts by explaining what a story is NOT.

It is not plot – that is just what happens in the story.

It is not characters , although characters are critical components of storytelling, even if they are not human or even alive. Cells and molecules could be the characters of your next science talk!

It is not suspense or conflict , although these elements get us closer to what defines a good story. But just because your talk builds suspense does not necessarily make it an engaging story. What if we don’t identify with your characters?

The truth is that the key defining element of story is internal change . Think of how every Aesop’s fable communicates a moral or lesson that the main character learned from some journey. As Lisa Cron writes, “A story is how what happens affects someone who is trying to achieve what turns out to be a difficult goal, and how he or she changes as a result.” The key here is the part about “how he or she changes.” A great story calls characters to a great adventure, but the adventure doesn’t leave them just as they were before. The adventure – like a scientific discovery that took years of experimentation (and failure) in the lab – leads to an internal change, in perspective or knowledge or behavior, as a result of conflicts overcome.

This is the secret of storytelling. A story asks characters to change and grow, and so the scientists in our stories must change and grow, discover new things about themselves and overcome challenges that force them to adopt new perspectives. So if you are giving a science talk about your own research, this might look like telling stories about your own struggles, growths and changes in perspective as you made your journey to discovery!

How can you bring a story of internal change to your next science presentation or talk?

What is one of the most common mistakes people make when creating slides to accompany a science talk? They use WAY too much text, and they use visuals as an afterthought. Worse yet, they use visuals that are copyrighted without attribution. They use stock imagery that reinforces stereotypes. They use visuals pasted from a Google search that don’t help the viewer understand or interpret what is said or written on the slides.

Visuals can be a powerful tool to advance audience learning or engagement during your science talks. You can use visuals to provide concrete examples of concepts you are talking about. You can use imagery that sparks thought or emotion. You can use visuals that reinforce your BIG idea or the theme of your talk, in a way that will make your talk more memorable for them. Yes, you might need to use a scientific figure, graph, chart or data visualization here and there if you are giving a more technical scientific talk, and that’s ok as long as you also talk the audience through this visual. Don’t assume they can listen to you talk about something different while also taking the time to interpret the message in this graphic or visualization – they can’t.

The same goes for text. You are demanding way too much brainpower of your audience to expect them to listen to you while also reading your slides. And if you are saying the same things as are written on your slides, they will grow bored. Simple visual aids used the right way, however, can delight your audience and help them better understand what you are saying.

Consider working with a professional artist or designer to create visuals for the slides of your next science talk! They excel at creating visuals that capture people’s attention, curiosity and emotions. And if you do this, your visuals will perfectly match what you are trying to communicate in words, boosting learning and understanding.

Foster Interaction

A good science talk or presentation gives the audience opportunities to interact with you! This could be through questions, activities, discussions or thought experiments. Let the audience explore your data or interpretations with you. They will be more engaged and likely trust you more as a result, because they felt heard .

Personalize!

Most great science speakers make themselves vulnerable in a way – they tell personal stories of struggles, growth and discovery. Personal stories are engaging. They also help the audience care about what the speaker has to say.

It can be scary to talk about yourself, especially for a scientist who has been trained to focus solely on the data. But the humans listening to your talk or presentation crave human connection. They will also grab hold of anything that helps them better relate to you. Give them that in the form of personal stories of obstacles overcome, of personal lessons learned, of work-life balance, of your fears and passions. Better yet, tell personal stories that reinforce your theme and show the power of your big idea!

Do you have other strategies for how you make your science talks and presentations more engaging? Let me know in the comments below!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

About the author: paige jarreau.

Related Posts

Una actividad práctica para ayudarte a comunicar la ciencia de forma culturalmente relevante

The Power of SciComm in Combatting Mental Health Stigma

Make your scicomm more culturally relevant: a practice activity.

Communicating About Postpartum Depression

Science Communication and Genetic Counselling

Creating Analogies: Elevate Your Science with a Lifeology Course

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Home Blog Education How to Prepare Your Scientific Presentation

How to Prepare Your Scientific Presentation

Since the dawn of time, humans were eager to find explanations for the world around them. At first, our scientific method was very simplistic and somewhat naive. We observed and reflected. But with the progressive evolution of research methods and thinking paradigms, we arrived into the modern era of enlightenment and science. So what represents the modern scientific method and how can you accurately share and present your research findings to others? These are the two fundamental questions we attempt to answer in this post.

What is the Scientific Method?

To better understand the concept, let’s start with this scientific method definition from the International Encyclopedia of Human Geography :

The scientific method is a way of conducting research, based on theory construction, the generation of testable hypotheses, their empirical testing, and the revision of theory if the hypothesis is rejected.

Essentially, a scientific method is a cumulative term, used to describe the process any scientist uses to objectively interpret the world (and specific phenomenon) around them.

The scientific method is the opposite of beliefs and cognitive biases — mostly irrational, often unconscious, interpretations of different occurrences that we lean on as a mental shortcut.

The scientific method in research, on the contrary, forces the thinker to holistically assess and test our approaches to interpreting data. So that they could gain consistent and non-arbitrary results.

The common scientific method examples are:

- Systematic observation

- Experimentation

- Inductive and deductive reasoning

- Formation and testing of hypotheses and theories

All of the above are used by both scientists and businesses to make better sense of the data and/or phenomenon at hand.

The Evolution of the Scientific Method

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , ancient thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle are believed to be the forefathers of the scientific method. They were among the first to try to justify and refine their thought process using the scientific method experiments and deductive reasoning.

Both developed specific systems for knowledge acquisition and processing. For example, the Platonic way of knowledge emphasized reasoning as the main method for learning but downplayed the importance of observation. The Aristotelian corpus of knowledge, on the contrary, said that we must carefully observe the natural world to discover its fundamental principles.

In medieval times, thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas, Roger Bacon, and Andreas Vesalius among many others worked on further clarifying how we can obtain proven knowledge through observation and induction.

The 16th–18th centuries are believed to have given the greatest advances in terms of scientific method application. We, humans, learned to better interpret the world around us from mechanical, biological, economic, political, and medical perspectives. Thinkers such as Galileo Galilei, Francis Bacon, and their followers also increasingly switched to a tradition of explaining everything through mathematics, geometry, and numbers.

Up till today, mathematical and mechanical explanations remain the core parts of the scientific method.

Why is the Scientific Method Important Today?

Because our ancestors didn’t have as much data as we do. We now live in the era of paramount data accessibility and connectivity, where over 2.5 quintillions of data are produced each day. This has tremendously accelerated knowledge creation.

But, at the same time, such overwhelming exposure to data made us more prone to external influences, biases, and false beliefs. These can jeopardize the objectivity of any research you are conducting.

Scientific findings need to remain objective, verifiable, accurate, and consistent. Diligent usage of scientific methods in modern business and science helps ensure proper data interpretation, results replication, and undisputable validity.

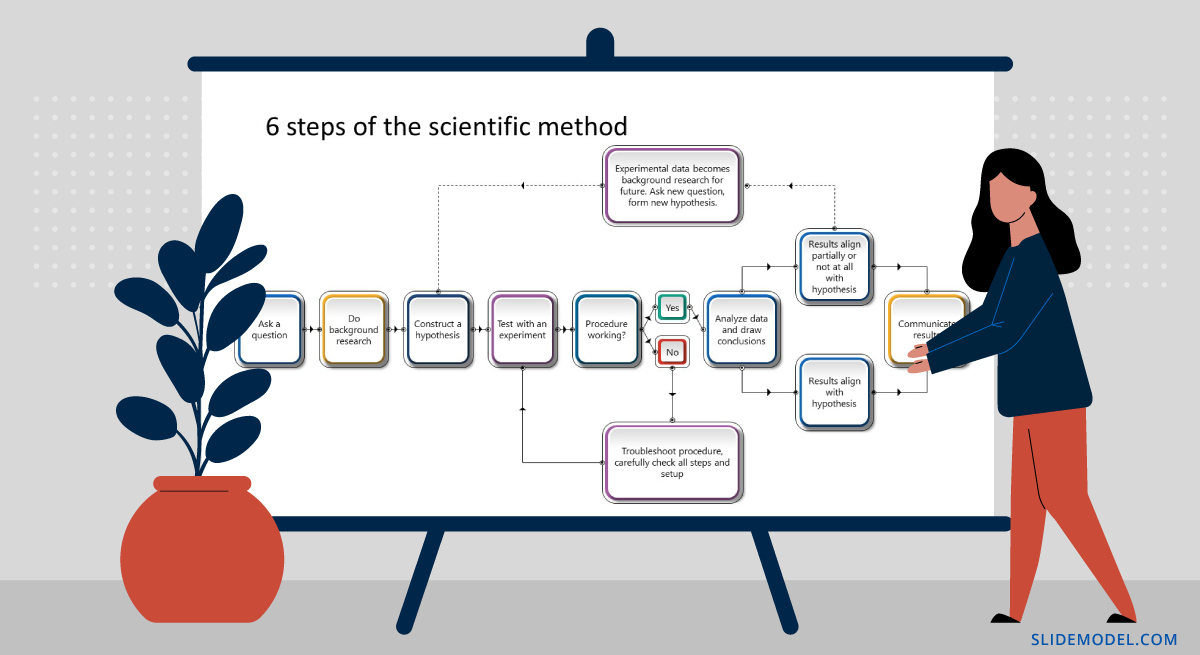

6 Steps of the Scientific Method

Over the course of history, the scientific method underwent many interactions. Yet, it still carries some of the integral steps our ancestors used to analyze the world such as observation and inductive reasoning. However, the modern scientific method steps differ a bit.

1. Make an Observation

An observation serves as a baseline for your research. There are two important characteristics for a good research observation:

- It must be objective, not subjective.

- It must be verifiable, meaning others can say it’s true or false with this.

For example, This apple is red (objective/verifiable observation). This apple is delicious (subjective, harder-to-verify observation).

2. Develop a Hypothesis

Observations tell us about the present or past. But the goal of science is to glean in the future. A scientific hypothesis is based on prior knowledge and produced through reasoning as an attempt to descriptive a future event.

Here are characteristics of a good scientific hypothesis:

- General and tentative idea

- Agrees with all available observations

- Testable and potentially falsifiable

Remember: If we state our hypothesis to indicate there is no effect, our hypothesis is a cause-and-effect relationship . A hypothesis, which asserts no effect, is called a null hypothesis.

3. Make a Prediction

A hypothesis is a mental “launchpad” for predicting the existence of other phenomena or quantitative results of new observations.

Going back to an earlier example here’s how to turn it into a hypothesis and a potential prediction for proving it. For example: If this apple is red, other apples of this type should be red too.

Your goal is then to decide which variables can help you prove or disprove your hypothesis and prepare to test these.

4. Perform an Experiment

Collect all the information around variables that will help you prove or disprove your prediction. According to the scientific method, a hypothesis has to be discarded or modified if its predictions are clearly and repeatedly incompatible with experimental results.

Yes, you may come up with an elegant theory. However, if your hypothetical predictions cannot be backed by experimental results, you cannot use them as a valid explanation of the phenomenon.

5. Analyze the Results of the Experiment

To come up with proof for your hypothesis, use different statistical analysis methods to interpret the meaning behind your data.

Remember to stay objective and emotionally unattached to your results. If 95 apples turned red, but 5 were yellow, does it disprove your hypothesis? Not entirely. It may mean that you didn’t account for all variables and must adapt the parameters of your experiment.

Here are some common data analysis techniques, used as a part of a scientific method:

- Statistical analysis

- Cause and effect analysis (see cause and effect analysis slides )

- Regression analysis

- Factor analysis

- Cluster analysis

- Time series analysis

- Diagnostic analysis

- Root cause analysis (see root cause analysis slides )

6. Draw a Conclusion

Every experiment has two possible outcomes:

- The results correspond to the prediction

- The results disprove the prediction

If that’s the latter, as a scientist you must discard the prediction then and most likely also rework the hypothesis based on it.

How to Give a Scientific Presentation to Showcase Your Methods

Whether you are doing a poster session, conference talk, or follow-up presentation on a recently published journal article, most of your peers need to know how you’ve arrived at the presented conclusions.

In other words, they will probe your scientific method for gaps to ensure that your results are fair and possible to replicate. So that they could incorporate your theories in their research too. Thus your scientific presentation must be sharp, on-point, and focus clearly on your research approaches.

Below we propose a quick framework for creating a compelling scientific presentation in PowerPoint (+ some helpful templates!).

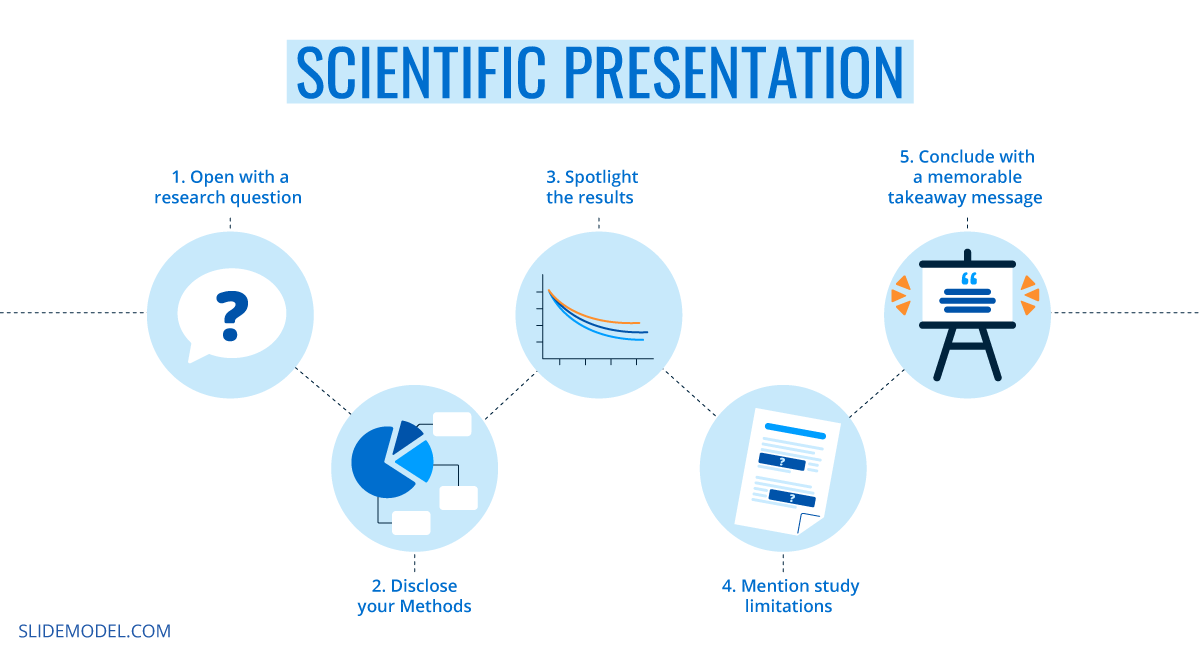

1. Open with a Research Question

Here’s how to start a scientific presentation with ease: share your research question. On the first slide, briefly recap how your thought process went. Briefly state what was the underlying aim of your research: Share your main hypothesis, mention if you could prove or disprove them.

It might be tempting to pack a lot of ideas into your first slide but don’t. Keep the opening of your presentation short to pique the audience’s initial interest and set the stage for the follow-up narrative.

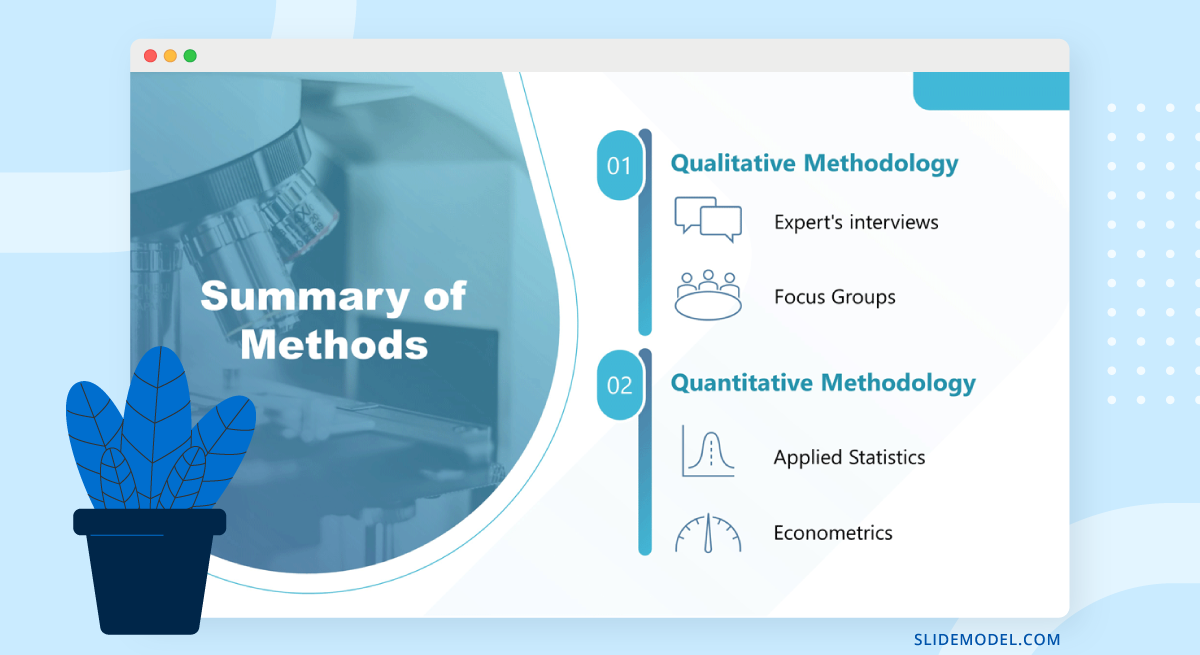

2. Disclose Your Methods

Whether you are doing a science poster presentation or conference talk, many audience members would be curious to understand how you arrived at your results. Deliver this information at the beginning of your presentation to avoid any ambiguities.

Here’s how to organize your science methods on a presentation:

- Do not use bullet points or full sentences. Use diagrams and structured images to list the methods

- Use visuals and iconography to use metaphors where possible.

- Organize your methods by groups e.g. quantifiable and non-quantifiable

Finally, when you work on visuals for your presentation — charts, graphs, illustrations, etc. — think from the perspective of a subject novice. Does the image really convey the key information around the subject? Does it help break down complex ideas?

3. Spotlight the Results

Obviously, the research results will be your biggest bragging right. However, don’t over-pack your presentation with a long-winded discussion of your findings and how revolutionary these may be for the community.

Rather than writing a wall of text, do this instead:

- Use graphs with large axis values/numbers to showcase the findings in great detail

- Prioritize formats that are known to everybody (e.g. odds ratios, Kaplan Meier curves, etc.)

- Do not include more than 5 lines of plain text per slide

Overall, when you feel that the results slide gets too cramped, it’s best to move the data to a new one.

Also, as you work on organizing data on your scientific presentation PowerPoint template , think if there are obvious limitations and gaps. If yes, make sure you acknowledge them during your speech.

4. Mention Study Limitations

The scientific method mandates objectivity. That’s why every researcher must clearly state what was excluded from their study. Remember: no piece of scientific research is truly universal and has certain boundaries. However, when you fail to personally state those, others might struggle to draw the line themselves and replicate your results. Then, if they fail to do so, they’d question the viability of your research.

5. Conclude with a Memorable Takeaway Message

Every experienced speaker will tell you that the audience best retains the information they hear first and last. Most people will attend more than one scientific presentation during the day.

So if you want the audience to better remember your talk, brainstorm a take-home message for the last slide of your presentation. Think of your last slide texts as an elevator pitch — a short, concluding message, summarizing your research.

To Conclude

Today we have no shortage of research and scientific methods for testing and proving our hypothesis. However, unlike our ancestors, most scientists experience deeper scrutiny when it comes to presenting and explaining their findings to others. That’s why it’s important to ensure that your scientific presentation clearly relays the aim, vector, and thought process behind your research.

Like this article? Please share

Education, Presentation Ideas, Presentation Skills, Presentation Tips Filed under Education

Related Articles

Filed under Google Slides Tutorials • May 3rd, 2024

How to Work with Google Slides Version History

Go back to previous changes or check who edited your presentation. Learn how to work with Google Slides Version History here.

Filed under Design , Presentation Ideas • May 1st, 2024

The Power of Mind Map Note Taking for Presenters

Add a new tool to your repertoire of presentation skills by mastering the art of mind map note taking. An ideal process to facilitate content retention.

Filed under Google Slides Tutorials • April 29th, 2024

Best Google Slides Add-Ons

Optimize your Google Slides experience by installing the best Google Slides add-ons available in the market. Full list with photos.

Leave a Reply

Your browser is not supported

Sorry but it looks as if your browser is out of date. To get the best experience using our site we recommend that you upgrade or switch browsers.

Find a solution

- Skip to main content

- Skip to navigation

- hot-topics Extras

- Newsletters

- Reading room

Tell us what you think. Take part in our reader survey

Celebrating twenty years

- Back to parent navigation item

- Collections

- Water and the environment

- Chemical bonding

- Antimicrobial resistance

- Energy storage and batteries

- AI and automation

- Sustainability

- Research culture

- Nobel prize

- Food science and cookery

- Plastics and polymers

- Periodic table

- Coronavirus

- More from navigation items

Source: © Shutterstock

How to give a scientific presentation

By Manisha Lalloo 2017-09-20T13:27:00+01:00

Five tips to keep an audience engaged without using cat pictures

Whether lecturing, presenting results at a conference or applying for a research proposal, giving presentations are a way of life for any chemist. But what are the best ways to get your point across while keeping your audience interested?

Think about your audience and remember that they want you to succeed

Jacquie Robson, is an associate professor of teaching at Durham University, UK, while Paul Bader is creative director at Screenhouse, an organisation which regularly trains scientists on how to develop better presentation skills. Here are their top tips.

Think about your audience

Whether presenting to colleagues or the general public, remember not everyone in your audience will be specialists. A common mistake scientists make is to assume others know as much as them when – more often than not – they are the expert in the room.

Even if your audience is well versed in the topic – for example, if you are presenting to a funding committee – do not start off with complex details. ‘If one person on the panel is outside the field, then you’ve lost them at the beginning,’ says Bader. Remember to give the big picture: it’s a good way in and a great way to make an impact.

Tell a story

‘Stories are easy to listen to and easy to tell,’ says Bader, who believes one of the most common mistakes is to cram too much information into just one talk. Structuring your talk in this way will help you to be selective.

Robson and Bader advise against learning a script by rote or reading a sheet of prose aloud. Written text is often more formal than convoluted than speech and sounds unnatural. Instead, have a set of key points on cue cards or use your slides as aide-mémoires. With a strong narrative, one point will lead to the next, making your talk more logical to follow and simpler to remember.

Robson also suggests telling your audience what you are going to speak about at the beginning of your talk and finishing off with a summary. That way your audience hears your main points three times – at the beginning, middle and end.

Visual aids are key

While PowerPoint is almost a given in today’s scientific presentations, try not to rely on it too much. ‘Slides should be clear, uncluttered and readable,’ says Robson. ‘Use diagrams rather than text.’

Slides should be used to highlight key points, not replicate your talk in written form. And remember never to turn your back on the audience – otherwise will be giving your presentation to the screen instead.

Don’t forget body language

‘Think about how you present yourself,’ says Robson. Have an open stance, smile, maintain eye contact, speak to the back of the room and at a good volume. ‘If you act confidently, they won’t know you’re feeling nervous.’

One of Robson’s pet peeves is a speaker who distracts the audience, for example by chewing gum or overusing laser pointers. Try to identify any habits you have while speaking that might take your audience’s attention away from your talk.

If you are feeling anxious, Robson advises against holding pieces of paper, which might shake in your hands. Bader suggests taking a moment to breathe. And both say the best technique is to ignore your nerves. The audience doesn’t want you to fail, and often won’t notice slip-ups. If you do make a big mistake, just correct yourself and carry on.

Practice, practice, practice

Perhaps the most important tip is to go through your presentation out loud before delivering it on the day.

‘People spend a lot of time writing their presentation or working on their slides but often the first time in public is the first time [they] do it,’ says Bader. By practising in advance and timing your run-throughs, you can discover if your talk is too long or too complicated.

There are many ways to practice, and it’s important to find the technique that works for you: you could video yourself on a phone and play it back, speak to yourself in front of a mirror or get somebody to listen to a rehearsal. According to Bader, the best way is to deliver your talk to a colleague or friend as you can see which parts they are engaged with (or not). ‘[But] any of the above is better than doing nothing,’ he adds.

And what about the dreaded questions at the end? ‘You can’t prepare for questions, so don’t fret,’ says Robson. ‘It’s not a spot exam, it’s a discussion. Make it into a conversation and don’t be afraid of saying “I don’t know the answer”.’

- Careers advice

- conferences

Related articles

A summer placement doesn’t have to be brilliant to be worthwhile

2024-05-10T13:30:00Z

By Emma Pewsey

How to find and make the most of a summer placement

2024-05-09T13:23:00Z

By Victoria Atkinson

Summer students act as an important catalyst for research

2024-05-09T09:02:00Z

The untapped power of emotional intelligence for PhDs

2024-04-26T12:00:00Z

By Matteo Tardelli

Empowering voices: Advancing social mobility in the chemical sciences

By Chemistry World

How to teach university-level chemistry well

2024-04-18T08:30:00Z

By Dinsa Sachan

1 Reader's comment

Only registered users can comment on this article., more from careers.

Troubleshooting your career

2024-04-10T13:30:00Z

How to troubleshoot experiments

2024-04-10T08:43:00Z

A sustainable career in sustainability

2024-03-28T14:28:00Z

By Julia Robinson

Making science communication persuasive and engaging

2024-03-21T09:30:00Z

By Philipp Gramlich

Losing a job can make you question who you are

2024-03-07T14:30:00Z

The community of colleagues supporting each other through redundancy

2024-03-07T09:31:00Z

- Contributors

- Terms of use

- Accessibility

- Permissions

- This website collects cookies to deliver a better user experience. See how this site uses cookies .

- This website collects cookies to deliver a better user experience. Do not sell my personal data .

- Este site coleta cookies para oferecer uma melhor experiência ao usuário. Veja como este site usa cookies .

Site powered by Webvision Cloud

- Become A Member

- Gift Membership

- Kids Membership

- Other Ways to Give

- Explore Worlds

- Defend Earth

How We Work

- Education & Public Outreach

- Space Policy & Advocacy

- Science & Technology

- Global Collaboration

Our Results

Learn how our members and community are changing the worlds.

Our citizen-funded spacecraft successfully demonstrated solar sailing for CubeSats.

Space Topics

- Planets & Other Worlds

- Space Missions

- Space Policy

- Planetary Radio

- Space Images

The Planetary Report

The eclipse issue.

Science and splendor under the shadow.

Get Involved

Membership programs for explorers of all ages.

Get updates and weekly tools to learn, share, and advocate for space exploration.

Volunteer as a space advocate.

Support Our Mission

- Renew Membership

- Society Projects

The Planetary Fund

Accelerate progress in our three core enterprises — Explore Worlds, Find Life, and Defend Earth. You can support the entire fund, or designate a core enterprise of your choice.

- Strategic Framework

- News & Press

The Planetary Society

Know the cosmos and our place within it.

Our Mission

Empowering the world's citizens to advance space science and exploration.

- Explore Space

- Take Action

- Member Community

- Account Center

- “Exploration is in our nature.” - Carl Sagan

Emily Lakdawalla • Feb 06, 2018

Speak your science: How to give a better conference talk

Bad presentation often gets in the way of good science. It's a shame, because science is awesome. So if you're a scientist who's interested in improving how you present your science, read on.

This post is a revised and updated version of one I wrote in 2013. Here's a recording of me giving this talk at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona on February 5, 2018 .

I can summarize my advice in three words:

Respect your audience.

Each one of the people in your audience is another person, like you. Their time is as valuable as yours. Work to deliver them a presentation that is designed for them, to inform and interest them in your work, and to leave them pleased that they spent that 5, 10, or 50 minutes of their valuable time listening to you.

Here are some questions to guide you in preparing a good talk.

To whom are you speaking?

Think carefully about your audience. Who are they, and what can you assume about what they already know about your topic? Is it an audience of your peers within your subspecialty? Is it space scientists more generally? Is it scientists and engineers? Is it a funding body? If it's the public, do they come to the room knowing a lot about space? Or is it a general audience?

The wider an audience you are addressing, the more context you will need to provide to them. If you do not provide the people in your audience with the information that they require in order to understand you, it is the same as telling them that you do not care if they understand you or not.

For a scientific conference, I suggest targeting your talks at an audience that is familiar with the scientific process but whose subspecialty is entirely different from yours. Are you an astronomer? Pitch your talk to a geologist. An experimenter? Pitch your talk to a theoretician.

Really good speakers are ones who manage to communicate something to everybody in the room, no matter who they are or how much they already know. To the relatively uninformed, you should at least answer: What is the question behind your work, and why is it important? What did you learn, and why does it matter? At the same time, to the well-informed, you should convey how your work has added to, broadened, or contradicted what has come before it.

Identifying your audience allows you to identify what words are jargon and what are not. Words are wonderful things, and our subspecialties have a lot of vocabulary that is dense with information. But if a word is not familiar to your audience, it will confuse rather than clarify. Sometimes, a jargon word is unavoidable; it may be the focus of your presentation. In that case, take care to define it more than once through the course of your presentation, and reinforce your teaching of the jargon word with context.

Acronyms and initialisms are a special class of jargon. It's easy to fall into a bad habit of using acronyms. They are often the most important nouns in your presentation. But unlike in a paper where you can define it, and people can look back if they forget what it means, there is no way to "look back" in a talk. I have attended many talks in which a TLA* is defined in the first moment, and if you miss it you are lost for the rest of the talk. Really, it often takes no more time to speak the words than to speak the letters.

(*TLA = Three Letter Acronym)

What do you want your audience to learn?