What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement: 4 Steps + Examples

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of a thesis statement, writing a good thesis statement: 4 steps, common pitfalls to avoid, where to get your essay edited for free.

When you set out to write an essay, there has to be some kind of point to it, right? Otherwise, your essay would just be a big jumble of word salad that makes absolutely no sense. An essay needs a central point that ties into everything else. That main point is called a thesis statement, and it’s the core of any essay or research paper.

You may hear about Master degree candidates writing a thesis, and that is an entire paper–not to be confused with the thesis statement, which is typically one sentence that contains your paper’s focus.

Read on to learn more about thesis statements and how to write them. We’ve also included some solid examples for you to reference.

Typically the last sentence of your introductory paragraph, the thesis statement serves as the roadmap for your essay. When your reader gets to the thesis statement, they should have a clear outline of your main point, as well as the information you’ll be presenting in order to either prove or support your point.

The thesis statement should not be confused for a topic sentence , which is the first sentence of every paragraph in your essay. If you need help writing topic sentences, numerous resources are available. Topic sentences should go along with your thesis statement, though.

Since the thesis statement is the most important sentence of your entire essay or paper, it’s imperative that you get this part right. Otherwise, your paper will not have a good flow and will seem disjointed. That’s why it’s vital not to rush through developing one. It’s a methodical process with steps that you need to follow in order to create the best thesis statement possible.

Step 1: Decide what kind of paper you’re writing

When you’re assigned an essay, there are several different types you may get. Argumentative essays are designed to get the reader to agree with you on a topic. Informative or expository essays present information to the reader. Analytical essays offer up a point and then expand on it by analyzing relevant information. Thesis statements can look and sound different based on the type of paper you’re writing. For example:

- Argumentative: The United States needs a viable third political party to decrease bipartisanship, increase options, and help reduce corruption in government.

- Informative: The Libertarian party has thrown off elections before by gaining enough support in states to get on the ballot and by taking away crucial votes from candidates.

- Analytical: An analysis of past presidential elections shows that while third party votes may have been the minority, they did affect the outcome of the elections in 2020, 2016, and beyond.

Step 2: Figure out what point you want to make

Once you know what type of paper you’re writing, you then need to figure out the point you want to make with your thesis statement, and subsequently, your paper. In other words, you need to decide to answer a question about something, such as:

- What impact did reality TV have on American society?

- How has the musical Hamilton affected perception of American history?

- Why do I want to major in [chosen major here]?

If you have an argumentative essay, then you will be writing about an opinion. To make it easier, you may want to choose an opinion that you feel passionate about so that you’re writing about something that interests you. For example, if you have an interest in preserving the environment, you may want to choose a topic that relates to that.

If you’re writing your college essay and they ask why you want to attend that school, you may want to have a main point and back it up with information, something along the lines of:

“Attending Harvard University would benefit me both academically and professionally, as it would give me a strong knowledge base upon which to build my career, develop my network, and hopefully give me an advantage in my chosen field.”

Step 3: Determine what information you’ll use to back up your point

Once you have the point you want to make, you need to figure out how you plan to back it up throughout the rest of your essay. Without this information, it will be hard to either prove or argue the main point of your thesis statement. If you decide to write about the Hamilton example, you may decide to address any falsehoods that the writer put into the musical, such as:

“The musical Hamilton, while accurate in many ways, leaves out key parts of American history, presents a nationalist view of founding fathers, and downplays the racism of the times.”

Once you’ve written your initial working thesis statement, you’ll then need to get information to back that up. For example, the musical completely leaves out Benjamin Franklin, portrays the founding fathers in a nationalist way that is too complimentary, and shows Hamilton as a staunch abolitionist despite the fact that his family likely did own slaves.

Step 4: Revise and refine your thesis statement before you start writing

Read through your thesis statement several times before you begin to compose your full essay. You need to make sure the statement is ironclad, since it is the foundation of the entire paper. Edit it or have a peer review it for you to make sure everything makes sense and that you feel like you can truly write a paper on the topic. Once you’ve done that, you can then begin writing your paper.

When writing a thesis statement, there are some common pitfalls you should avoid so that your paper can be as solid as possible. Make sure you always edit the thesis statement before you do anything else. You also want to ensure that the thesis statement is clear and concise. Don’t make your reader hunt for your point. Finally, put your thesis statement at the end of the first paragraph and have your introduction flow toward that statement. Your reader will expect to find your statement in its traditional spot.

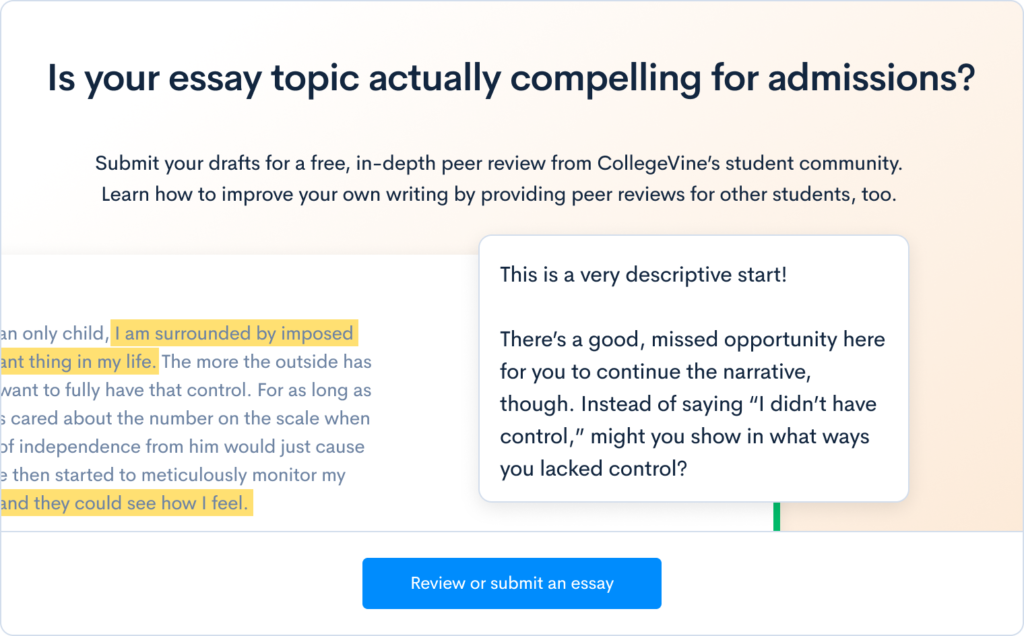

If you’re having trouble getting started, or need some guidance on your essay, there are tools available that can help you. CollegeVine offers a free peer essay review tool where one of your peers can read through your essay and provide you with valuable feedback. Getting essay feedback from a peer can help you wow your instructor or college admissions officer with an impactful essay that effectively illustrates your point.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Step #1: Thesis Statements

Your thesis is the engine of your essay. It is the central point around which you gather, analyze, and present the relevant support and philosophical reasoning which constitutes the body of your essay. It is the center, the focal point. The thesis answers the question, “What is this essay all about?”

A strong thesis does not just state your topic but your perspective or feeling on the topic as well. And it does so in a single, focused sentence. Two tops. It clearly tells the reader what the essay is all about and engages them in your big idea(s) and perspective. Thesis statements often reveal the primary pattern of development of the essay as well, but not always.

Thesis statements are usually found at the end of the introduction. Seasoned authors may play with this structure, but it is often better to learn the form before deviating from it.

- Consult this link for the OWL thesis statements discussion.

- Here is another link to assist with argumentative thesis statements.

- Consult these Thesis Writing Exercises for more help in crafting a strong, relevant thesis statement.

BEST: A thesis is strongest when the writer uses both the specific topic, and their educated opinion on it, for writing a detailed and clear main point.

- Watch this video on writing a “Killer” Thesis Statement

- Watch this video on writing an effective Academic Thesis Statement.

The Writing Process Copyright © 2020 by Andrew Gurevich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Informed Arguments: A Guide to Writing and Research - Revised Second Edition

(10 reviews)

Terri Pantuso, Texas A&M University

Sarah LeMire, Texas A&M University

Kathy Anders, Texas A&M University

Copyright Year: 2019

Last Update: 2022

Publisher: Texas A&M University

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Yongkang Wei, Professor, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 12/21/22

This would be a useful source for teaching first-year writing courses, as it covers all the subjects that are supposed to be dealt with, esp. if the focus of teaching is placed on argumentation. I have been actively looking for a textbook that... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

This would be a useful source for teaching first-year writing courses, as it covers all the subjects that are supposed to be dealt with, esp. if the focus of teaching is placed on argumentation. I have been actively looking for a textbook that puts emphasis on a rhetorical approach to writing. And this one would come in handy for its rather comprehensive coverage of the approach. It features a chapter on "rhetorical situation" that includes a section called "rhetorical analysis," a topic not commonly, or extensively, discussed in similar types of textbooks.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

I'm not aware of anything that is not accurate, error-free or unbiased.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

While I cannot speak for other instructors, the content of this Open Education Resource textbook would be a good match for what I will teach using a non-OER (i.e., paid) textbook. For example, my syllabus covers the topic of rhetorical analysis, which is conveniently found in the third chapter of the book. My syllabus also covers the three models of argumentation: Classical, Rogerian, and Toulmin, which are all discussed and presented in full length by the authors/editors. Nowadays, going rhetorical is the trend, so I anticipate this OER book will enjoy a long period of relevancy and currency as course material for those teaching first-year writing courses. Plus, its online formation can make a quick update.

Clarity rating: 5

The text is written in a way suitable to the level of first-year college students. Jargons or technical terms are minimal. If they do occur, they are well explained within context, as seen, for example, in those terms of logical fallacies. At the end, there is a list of glossaries, which is of additional help if a student encounters an unfamiliar term.

Consistency rating: 5

The authors/editors stress the rhetorical approach to writing. The whole textbook is built around that approach, which also ensures a framework of consistency for content delivery.

Modularity rating: 5

The modularity of the book is excellent. The whole book is divided into eight chapters, each of which is further divided into sections and subsections. The smaller reading sections can keep students away from "boredom," but more importantly they also make it easy and convenient for instructors to pick and reorganize subunits of a course that will best fit their own needs or situations.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The topics of the book are presented in a sequence as expected. However, Chapter 8, the last chapter, may not be up to its title, Ethics, as most of the sections are more related to the previous chapter on researched writing. For example, citation formatting and APA or MLA format can well be incorporated into Chapter 7.

Interface rating: 5

I have not encountered interface issues when reading through the book.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

This is a non-issue. All contributors to the book are excellent writers.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

I have not come across any issues in the textbook that can be described as culturally insensitive or offensive.

I wish a list of readings, or their links, were incorporated into each chapter to save instructors' time and energy looking for relevant reading materials. Additional readings are part of a writing course. They provide material for fruitful classroom discussions. Used as examples, they also help illustrate subjects to ensure a better understanding on the part of students.

Reviewed by Tara Montague, Part-time instructor, Portland Community College on 6/28/22

I’d give this a 4.5 if I could. This text covers nearly everything that I’d want to cover in a FYW course on thesis-driven argument. I would love to see a revised introduction with a more robust intro aimed at the student – one that formally... read more

I’d give this a 4.5 if I could. This text covers nearly everything that I’d want to cover in a FYW course on thesis-driven argument. I would love to see a revised introduction with a more robust intro aimed at the student – one that formally introduces thesis-driven argument (and previews the text's approach/structure). I think that would help the rest of the pieces fall into place more clearly for me. The glossary is great, and the way glossary items are handled when they show up in the text (active link with a pop-up box) is extremely useful and appreciated.

I did not notice any inaccuracies, biases, or errors.

Current examples were used (a 2010 textbook, Kamala Harris’s VP Acceptance speech), and I believe they were used in a way that will remain relevant to readers.

The writing is clear and accessible. It does go into more depth about rhetoric and argument (Toulmin, Rogerian) than I think many FYW classes would go, but is still accessible. I do feel like a clearer spelling out of the relationship/usage of the terms persuasion and argument would help. This is kind of approached in chapter 3.7, but it’s a bit lacking for me.

Consistency rating: 4

Some of the chapters and sections seem a bit broad and generic given the text’s stated focus on thesis-driven argument. And some examples of thesis statements seem too simplistic for argument – or don’t really match the genre of thesis-driven argument.

The text is easily and readily divisible. My interest is in adopting specific chapter/sections; this can be done without any difficulty whatsoever. It would also be easy to reorganize to improve upon the organizational issues that I believe the text has.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 3

The overall structure of the text is not super intuitive. It starts with the writing process (section 2: analyzing assignment, prewriting), and then circles back to it in section 5. As I refer back to the text to write this review, I see this even more strongly – I have trouble finding the chapters I’m looking for as they’re not under the sections of the text I’d expect them to be; I keep getting lost.

Given the text’s title, I would expect introduction/discussion of main concepts – especially thesis-driven argumentation – before launching into the writing process or even rhetoric. Additionally, some chapters/sections/pages are two paragraphs long, and some are more than ten screens’ worth, and the variation (and what is chunked into a separate chapter/section vs. what is just a heading within a chapter/section) isn’t guided by a clear organizational principle. If I were looking to adopt an entire text (as opposed to selecting sections of it), this would cause me problems. (It should be noted that the authors make it clear that this text is written for a specific course at TAMU.)

The heading “Writing a persuasive essay” comes within a chapter/section about using visual elements (3.11). I believe this is a mistake.

The text is offered in various formats and is downloadable. Extremely user-friendly and easy to navigate. In the eBook, the text contains an active glossary: when you click on an underlined term (i.e. secondary sources), its glossary entry/definition/explanation pops up.

The text has been carefully edited and is very clean. I didn’t see any grammatical errors. The only thing I noticed is a confusing lack of “strike-through” in a subtitle of Chapter 4.6: “Thesis Is Not Doesn’t Have to Be a Bad Thing (Or Why Write Antithesis Essays in the First Place”).

I don’t believe the text is culturally insensitive or offensive. I believe it used a couple of examples that were inclusive of a variety of backgrounds.

There are definitely elements of this text that I will use in my FYW (Writing 122) course. I appreciate how succinctly and clearly the text distinguishes between (intended) audience and reader. I also like the logical fallacies section. I typically don’t go into these in my FYW course, but this text does a good job of selecting fallacies that many students tend to use in their own arguments; it provides a solid short list for students to evaluate their own reasoning. I really like the chapter on counterargument / antithetical writing by Steven D. Krause that they included.

Reviewed by Carrie Dickison, Associate Teaching Professor, Wichita State University on 6/3/21

The text covers the writing process, rhetoric and argumentation, and research-based writing sufficiently in-depth to work as a primary textbook for a composition course focusing on these topics. As with most OERs, instructors will likely need to... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

The text covers the writing process, rhetoric and argumentation, and research-based writing sufficiently in-depth to work as a primary textbook for a composition course focusing on these topics. As with most OERs, instructors will likely need to supplement the text with examples. Unfortunately, there is no table of contents or index, so instructors using the text will need to spend extra time scrolling to identify content.

Content is in-line with other mainstream composition textbooks.

The content is up-to-date, and most examples will seem relevant to students. For example, it references the keto diet and Trump’s inaugural address. The section on MLA is updated for MLA 8, which is better than many open-access composition texts.

The register is appropriate for first-year students, and the text does a nice job of explaining discipline-specific terminology.

The text is consistent in its approach to writing, argumentation, and research.

Modularity rating: 4

Each section is divided into sub-sections with sub-headings, making it fairly easy to assign different parts of a section. However, sub-sections are not numbered, making them somewhat cumbersome to put on a syllabus.

In general, the text is organized logically. Most sections have a clear focus (e.g. the writing process, an introduction to rhetoric, structuring an argument). However, there are a few sections that I found confusing. For example, there are two different discussions of types of sources (in two different sections), and the discussion of evaluating sources comes before the discussion of research strategies. However, it wouldn’t be too difficult to assign these sections in a different order.

Interface rating: 4

The text is only available as a PDF, which cuts down on image distortion and broken links. However, it also makes it harder to navigate the text, especially since there is no table of contents.

I didn’t notice any grammatical errors in the text.

The text is not culturally insensitive or offensive.

This is a good choice for a course that focuses on rhetoric, argumentation, and research-based writing. It’s also less institution specific than other OERs with similar content, making it easier to adapt for another institution.

Reviewed by Stefanie Shipe, Associate Professor, Northern Virginia Community College on 5/10/21

The textbook offers a thorough discussion of the writing process and the research process. The section on paragraph development is especially comprehensive. The section on the Writing Process could be more robust, particularly the discussion of... read more

The textbook offers a thorough discussion of the writing process and the research process. The section on paragraph development is especially comprehensive. The section on the Writing Process could be more robust, particularly the discussion of medium. With more and more emphasis on multimodality in freshman-level composition classes, this textbook would benefit from an expanded section on visual argument and/or non-traditional argument. The section on Rogerian Argument is very brief.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

The content is accurate, although the section on Rogerian Argument doesn't give a complete picture of the strategy.

All the content is relevant, and examples can be easily updated as needed.

The language is accessible, and new terms are explained for readers.

Terminology and framework remain consistent.

The text is broken down into logical sections. It might be helpful to make the section numbers more easily accessible for readers. Some sections also have very large blocks of text that may be somewhat difficult to follow.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Topics are presented logically.

The PDF is mostly written text, which may be challenging for certain readers. The addition of more tables, graphs, colors, or images might help to break up the text to make it more accessible and easy to read. Section headings could also be more clear and easier to locate.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

I noticed a few minor issues with widows/orphans, I also noticed one minor error: in section 4.18, "pro-choice" contains the hyphen, but "prolife" does not.

I don't see any major issues with inclusivity, although one or two sections might benefit from some language to alert a reader to sensitive content (such as the abortion issue).

Reviewed by Lee Ann Regan, Adjunct Professor, Northern Virginia Community College on 5/5/21

This textbook covers all the topics I cover in my Composition II class, though I would like more on analyzing visual arguments (ads, photos, political cartoons). read more

This textbook covers all the topics I cover in my Composition II class, though I would like more on analyzing visual arguments (ads, photos, political cartoons).

Accurate, though to be picky in the block quote example (6.15) there is a period after the parenthetical citation contrary to MLA style.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

Although mention of specific TV shows and Trump's inaugural speech may date quickly, these are tiny elements in the material. Most of the content will remain relevant for a long time.

The text's prose is accessible without being condescending.

In Section 3, Rhetorical Modes of Writing discusses narration, description, and exposition which I found out of place in a book on writing arguments. However, these are types of essays often assigned in freshman composition classes.

The text is divided into clear sections on each topic aspect which could easily be assigned.

There is a clear progression from assignment through the writing process.

The screenshot of database functions is distorted. Scrolling back and forth in a PDF can be awkward.

I noticed no grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

Nothing stood out as offensive.

This textbook covers the topic of writing academic argument well. While I missed sample essays to analyze they can date a book quickly and instructors can easily add them to supplement the text. I found the sections on research and maintaining voice, areas where students sometimes struggle, particularly strong.

Reviewed by Linda McHenry, Instructor of First-Year Composition & Coordinator of Composition-Sequence Assessment, Fort Hays State University on 3/26/21

This comprehensive textbook, appropriate for an English Composition II course, both describes and explains six steps in the writing process for a first-year composition student. An example of a student’s prewriting is included. Rhetorical... read more

This comprehensive textbook, appropriate for an English Composition II course, both describes and explains six steps in the writing process for a first-year composition student. An example of a student’s prewriting is included. Rhetorical situation is explained well for first-year students. “Rhetorical Modes of Writing” provides explanation for many writing assignments students typically encounter in the composition sequence, including narration, description, classification, process, definition, comparison and contrast, cause and effect, and persuasion. Also, there are explanations and examples of a visual analysis essay. Toulmin Argument is written clearly for first-year students in a writing course, and Rogerian Argument is discussed and explained, as well. Inclusion of both arguments gives composition faculty options for how to best approach specific argumentative assignments in their courses.

Content is error-free and mostly unbiased. Initially, I found the logical fallacies sections cursory but appreciate the depth of argument in the last half of the textbook.

Most of the textbook reads as relevant and will remain relevant for some time. Most examples, such as TVs, e-books, reality TV shows, and hybrid cars, will remain relatable to first-year students. There is an outdated reference to TV Guide, which I’m confident traditional first-year students will need explained.

One of the most-impressive strengths of this textbook is the way the writers introduce, define, explain, and use terms throughout the text. Argument can be a complicated concept for students, and the sections focusing on types of argument and ways to construct effective arguments meaningfully and deliberately demystify the ways writers tailor their messages for target audiences. Later in the textbook, library database searching is explained well, especially with the Boolean examples.

Writing is discussed and explained before researching, which makes complete sense. The text also features helpful research worksheets to aid with search terms.

The textbook is available in multiple formats, including .pdf and Google Doc, allowing for integration with various learning-management systems. The textbook’s clear headings and page numbers allow faculty to point to specific sections or assignments from their syllabus. Or faculty can copy and paste particular parts into their specific learning-management system with section titles and authors clearly listed.

The textbook is logically organized, beginning with writing process. The research process is well written and provides solid examples of student research plans. The argument sections are well organized and build on one another.

Interface rating: 3

Text and visual aides are mostly clear. The screen grab of library research results is blurry and difficult to view. I had no problems moving between the sections. Visual aides are labeled but are missing descriptive text that would help readers with visual deficits understand drawings, graphics, and charts.

I found no grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 2

In a section that asks students to “Imagine Hostile Audiences” (p. 78), the textbook engages positions on abortion. In a first-year composition textbook, naming issues that some students will have lived through lacks sensitivity to what some of our students have had to endure—for both those who have carried an unwanted pregnancy to full term and those who have terminated a pregnancy. Certainly, other issues can illustrate hostile audiences without evoking the pain and stress that surround abortion.

Overall, this is an effective textbook for English Composition II.

Reviewed by Andrew Howard, Assistant Professor/Program Coordinator of English, The University of the District of Columbia on 2/26/21

This book covers everything that a first-year writing professor would expect to see, and it covers everything a first-year writing student will need to encounter for academic writing. The layout is logical and the tone is approachable enough that... read more

This book covers everything that a first-year writing professor would expect to see, and it covers everything a first-year writing student will need to encounter for academic writing. The layout is logical and the tone is approachable enough that students will not only be guided through the writing process, but will be given a guide and reference they can use throughout the rest of their academic careers. The information and its presentation concerning research is top-notch! Very informative and practical.

I found nothing inaccurate! The fundamental topics this book approaches are clearly and concisely illuminated, but they are, at heart, near-universal truths. Pantuso et al. present the basic tenets of the writing process in rock-solid terms and cite when necessary, giving a real sense of relevance, accuracy, and currency.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

It appears that the main ideas presented in Informed Arguments will be in place for some time, so the relevance is not much of an issue here. As for being up-to-date, I'd hope that the authors do a once-over every few years with an eye toward their characterization of students, particularly when you see examples of student voice. The other area I'd suggest giving attention is the acknowledgment of multi-modal assignments; I'd expect more beyond the usual rhetorical mode structure found in so many textbooks.

The text is absolutely clear in how it presents ideas. Pantuso et al. never get bogged down purple or overly-academic prose. They never speak down to their audience or hold the subject of writing is such high esteem as to present themselves as elites guarding inaccessible information. There's a real sense that this textbook was written by humans who are concerned with getting across the important nuances of writing--something that we often miss in textbooks.

The no-nonsense approach that the authors take ensures that their text is indeed consistent throughout.

Modularity rating: 3

My biggest issues here are addressed in the interface portion, but I'd like to see clearer breaks, not only between sections, but in the writing examples. Occasionally you'll get a title at the end of one page, then the writing example begins on the next. Could use a bit more cleanup or widow/orphan consideration.

No issues here--the text is presented in the most logical

I may be biased against pdf textbooks, but I find them impossible to navigate with any sense of surety. This text could likely be reorganized of necessary, and seems to be presented somewhat modularly (though there is certainly a logical order to the text overall). If the material were presented as a central hub with explorable modules, I believe the layout would be easier to navigate. I'd also like more visual cues that I am moving from one topic to the next. Aside from the occasional obvious page break and slightly larger text for headings, I don't get much of a sense that I've moved from one section to another. The visuals that are provided are very helpful and logical; however, there are not enough. I'd like to see a few visuals related to the examples in the text. Take 4.8, for example: there's a student essay on the X-Files. While there is surely an issue of copyright concerning an image of Mulder and Scully, throw a clip art alien or something in there!

I noticed no grammatical issues!

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

I didn't see much to suggest that this book went either way on the scale of cultural sensitivity.

Reviewed by Oline Eaton, Lecturer, Howard University on 1/27/21

This is an especially comprehensive text on writing arguments intended for an audience of first year students. The authors very effectively assess the knowledge base of that readership and, accordingly, open the book with a chapter that offers... read more

This is an especially comprehensive text on writing arguments intended for an audience of first year students. The authors very effectively assess the knowledge base of that readership and, accordingly, open the book with a chapter that offers students a practical, step-by-step guide to the college essay writing process (from understanding the assignment on through incorporating feedback into a final, polished version of an essay). The authors also adeptly introduce the vocabulary students will need in the writing classroom and use it to introduce and unpack complex concepts in a way that avoids jargon and is, therefore, likely to be more easily understood by students. The text gives students a very solid foundation for understanding the essay assignments they are likely to encounter, not only in the writing class that uses this book but in their other college classes.

I saw nothing in the text that gave me concerns regarding its accuracy.

The book has a really nice, readable tone that is likely to appeal to students and was clearly produced by writers who are actively teaching students today. Their examples are ones students will likely relate to. One such instance is in the section on audience, where two different descriptions of the same event (one formal and intended for public consumption; the other reading more like a text to a friend and opening with "OMG!") are used to make the point that students are accustomed to taking audience into account often in their daily lives, even if unconsciously. The text very deliberately builds from the discussion in the opening chapter on how to read an assignment to the final chapter's highly detailed discussion of how to conduct robust academic research online. The research section, in particular, is something I'm now contemplating incorporating into my classes on Zoom this semester, in lieu of or in conjunction with a librarian visit. If you're teaching argument and/or researched argument, this book very elegantly and straight-forwardly covers all the bases. The book was written explicitly for use at Texas A&M, by professors at Texas A&M. This isn't all that intrusive, and I think it would absolutely be usable in classes outside of that university. It's just something to be aware of and explains why there are Texas A&M examples throughout.

This is a very clearly written text, that would be very accessible to first year college students of all ages. The authors do an excellent job of defining their terms and fully unpacking concepts that might be new to students.

The text builds a cohesive, internally consistent argument about how students may best go about argumentative writing. By the time students reach the final section on research and ethics, they should have everything they need to produce robust, ethical arguments within the writing process developed through the earlier sections.

Because it opens with the focus on simply how to read an assignment and goes all the way through the research progress, the book is structured in such a way that it could easily be incorporated into a one- or two-semester writing/research course.

I can think of no better way to organize this text. It very logically proceeds from one phase of the process of writing arguments to the next. Reading it, it very nicely aligns with how I already structure my own classes and one can easily see how it could be used to scaffold a one- or even a two-semester first year writing course.

The text was very user-friendly, with helpful charts and graphics. One thing to note is that there is a screenshot of the University Library page search box, which may not perfectly match all university libraries. A small detail, but something to be aware of if you're trying to bring this into your classroom outside of Texas A&M.

This is a very well edited and proofread text, which is obviously extra important in a writing class.

The text is not culturally insensitive or offensive. However, I'm not sure that it's particularly inclusive either. I'm unfamiliar with the student demographics of Texas A&M, so perhaps it is a great fit for them. However, the text might have benefited from a few examples that demonstrate the variety of student experiences. In classrooms with populations of students of color, parents, or disabled students, it might be desirable to augment the reading by bringing in some more inclusive examples for classroom discussion.

I highly recommend this text for first year writing classrooms.

Reviewed by Grant Bain, Instructor, Colorado State University on 12/28/20

The textbook is amazingly comprehensive, especially given its brevity. I was surprised to see, for example, how thoroughly the authors were able to cover major concepts in argument theory. The authors introduce not only classical argument, but... read more

The textbook is amazingly comprehensive, especially given its brevity. I was surprised to see, for example, how thoroughly the authors were able to cover major concepts in argument theory. The authors introduce not only classical argument, but also the Toulmin model and Rogerian argument, which is a great way to introduce students to the complexities of this concept. The only major shortcoming that I see is its focus on essays. While the essay is an important and useful genre for exploring ideas and generating knowledge, students need to be given opportunity to practice other forms (reports or proposals, for example) in order to more fully understand how to adapt their writing across varying contexts and purposes. The authors focus very heavily on the rhetorical situation, which they should, but that focus its somewhat belied by their concurrent focus on the form of the essay, which limits the purpose, audience, and texts with which a student might interact.

This text is remarkably well-aligned with current practices in writing scholarship and pedagogy. It's chapters offer concise yet thorough discussions of major concepts like the rhetorical situation, rhetorical appeals, and even ethics in writing. While "accuracy" is a tricky concept to apply to something as qualitative as writing, the text is in agreement with prevailing scholarly trends and practices.

The text is very relevant to its intended audience of freshman composition students. I particularly like the focus on process and rhetorical situation. The textbook begins by prompting students to understand a writing assignment, which is something that I cannot foresee ever becoming outdated. Having students begin by assessing the needs of their specific situation is so important and yet still so undervalued in a lot of writing curricula.

The text's rhetoric and examples are clear and very accessible. In fact, I think this textbook may be the most accessible to freshman college students that I've seen. The author's shy away from all but the most necessary jargon, and what specialized terms they do use (rhetorical situation, etc) are very fully contextualized and explained.

The books is very consistent across all chapters. Its rhetoric is well-organized around the central concept of the rhetorical situation. Even though the text doesn't fully address that term until Section 3, it opens by encouraging students to understand each specific writing assignment, thereby prompting them from the very beginning to understand fully the situation in which they are writing.

For the most part I feel like this text could be used in a variety of ways and its chapters assigned in varying sequences.

Given the recursive nature of writing, this text is organized in a very logical and utilitarian way. Each chapter develops its subject very well and provides enough context along the way for a freshman audience to be able to understand that subject. The overall chapter organization is also very practical, and develops the point of the book quite well, even if teachers decide to assign chapters in a different order than that in which they are arranged in the book.

This is one of the biggest flaws for me. A PDF is one of the least user-friendly interfaces; even a physical book makes it easier to mark important passages and easily move back and forth between them. I realize that OER funding availability makes interface a challenge, but this is a notable flaw of this text. It's hardly a reason not to adopt it, however.

I detected no grammatical errors whatsoever.

I would agree with this for the most part. I do question the use of President Trump's inaugural speech to exemplify the rhetorical situation, however. Maybe the divisiveness of Trump's administration will fade over time, but right now it seems like a poor choice, in that many students will have a hard time thinking in any way objectively about it. Given that no specific examples from the address are used, I'm not sure why the authors chose to specify Trump's inaugural address over the situation of an inaugural address more generally. For now and for the next few years, however, it seems like a poor choice.

Pantuso et al. have produced a clear, concise, and very useful textbook. It would be a great supplement or even primary rhetoric for a freshman composition course. If the authors were to revise the textbook to include a wider variety of genres--thereby exposing students to a wider variety of rhetorical situations--this would be an outstanding OER text.

Reviewed by Paul Lee, Associate Professor, University of Texas at Arlington on 11/11/20

I think it covers a lot of the basics, which is good, and I understand that it is intended to be a short, more concise introduction to academic writing. However, I would like to see a little more depth in areas like ethos, pathos, logos and the... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

I think it covers a lot of the basics, which is good, and I understand that it is intended to be a short, more concise introduction to academic writing. However, I would like to see a little more depth in areas like ethos, pathos, logos and the rhetorical situation. These form the basis of modern argument, so it seems important to dig a bit deeper and to provide some relevant examples and situations to further explain these appeals.

The authors did an excellent job of accuracy and avoiding bias. Some of the points they make may give the wrong impression to students, however, like their description of the thesis statement being in the introduction in most cases. This is true, but it can be practically anywhere in the paper and I think it is relevant to let the students know that so their papers aren’t quite so mechanical and formulaic.

They did an excellent job of this, as well. This information doesn’t tend to change very quickly, but they still presented it in a way that should stand up to time very well, so I would say that this text will be useful for quite a while. A lot of texts tend to use examples that are quickly out-of-date (like political issues or current events); these can be more relevant and relatable to the students so they can help them to understand more easily, but they can quickly become irrelevant and have the opposite effect. Unless I overlooked it, I didn’t see any issues like that with this text.

Clarity rating: 4

It definitely is very clear. Again, some further elaboration on certain topics/concepts might make it even more clear (e.g., examples, more detailed explanations, and so on).

I didn’t see any issues with the consistency. Overall this book does a great job of holding together and explaining how each individual topic relates to the overall discussion of writing and the writing process. It speaks to the clarity of the text, as well, that each section of the book allows the text overall to support its own thesis about writing.

The book felt more linear than modular; in other words, it feels like the book should be read at the beginning as each section builds on the previous one. There were some exceptions like the visual arguments section; even these need some previous material to be fully understood and utilized, however.

The organization is excellent. This is the upside to the linear style I mentioned in the earlier section. If you tend to organize your class in this fashion, then this is a great book to do that; it will allow you to provide information that consistently builds upon the information before it.

Interface rating: 1

I am NOT a fan of long texts that are in PDF format. This made it very difficult to navigate around in the text, particularly with a smaller device like an iPhone. I read it both on an iPad and an iPhone and when I was on the iPhone I found myself getting very weary of constant speed-scrolling to find an area later in the book (say, page 160 for example). I think a different format (like ePub) would be a huge improvement.

The book’s grammar looked excellent. I didn’t notice any particular issues, and being a rhetoric & composition instructor I’m very observant of things like that.

Being about a fairly innocuous topic in the first place (unless controversial examples are used) this book didn’t have any issues that stood out to me. I mentioned earlier that it tends to stay fairly up-to-date in its examples, and this is another upside of that — it’s not using anything that is overly controversial.

Overall it’s a very well-written text that could be used if you want a more concise and to-the-point discussion of the major aspects of writing and the writing process. I think it could use a little more detail, development, as well as examples, however. And I’m not a fan of having to scroll endlessly through a PDF document, so a different format seems to be in order.

Table of Contents

- I. Introduction

- II. Getting Started

- III. Rhetorical Situation

- IV. Types of Argumentation

- V. Process and Organization

- VI. Joining the Academic Conversation

- VII. Researched Writing

- VIII: Ethics

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Welcome to composition and rhetoric! While most of you are taking this course because it is required, we hope that all of you will leave with more confidence in your reading, writing, researching, and speaking abilities as these are all elements of freshman composition. Many times, these elements are presented in excellent textbooks written by top scholars. While the collaborators of this particular textbook respect and value those textbooks available from publishers, we have been concerned about students who do not have the resources to purchase textbooks. Therefore, we decided to put together this Open Educational Resource (OER) explicitly for use in freshman composition courses at Texas A&M University. It is important to note that the focus for this text is on thesis-driven argumentation as that is the focus of the first year writing course at Texas A&M University at the time of development. However, other first year writing courses at different colleges and universities include a variety of types of writing such as personal essays, informative articles, and/or creative writing pieces. The collaborators for this project acknowledge each program is unique; therefore, the adaptability of an OER textbook for first year writing allows for academic freedom across campuses.

About the Contributors

Dr. Terri Pantuso is the Coordinator of the English 104 Program and an Instructional Assistant Professor in the English Department at Texas A&M University.

Prof. Sarah LeMire is the Coordinator of First Year Programs and an Associate Professor in the Texas A&M University Libraries.

Dr. Kathy Anders is the Graduate Studies Librarian and an Associate Professor in the Texas A&M University Libraries.

Contribute to this Page

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Thesis Statements

Basics of thesis statements.

The thesis statement is the brief articulation of your paper's central argument and purpose. You might hear it referred to as simply a "thesis." Every scholarly paper should have a thesis statement, and strong thesis statements are concise, specific, and arguable. Concise means the thesis is short: perhaps one or two sentences for a shorter paper. Specific means the thesis deals with a narrow and focused topic, appropriate to the paper's length. Arguable means that a scholar in your field could disagree (or perhaps already has!).

Strong thesis statements address specific intellectual questions, have clear positions, and use a structure that reflects the overall structure of the paper. Read on to learn more about constructing a strong thesis statement.

Being Specific

This thesis statement has no specific argument:

Needs Improvement: In this essay, I will examine two scholarly articles to find similarities and differences.

This statement is concise, but it is neither specific nor arguable—a reader might wonder, "Which scholarly articles? What is the topic of this paper? What field is the author writing in?" Additionally, the purpose of the paper—to "examine…to find similarities and differences" is not of a scholarly level. Identifying similarities and differences is a good first step, but strong academic argument goes further, analyzing what those similarities and differences might mean or imply.

Better: In this essay, I will argue that Bowler's (2003) autocratic management style, when coupled with Smith's (2007) theory of social cognition, can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover.

The new revision here is still concise, as well as specific and arguable. We can see that it is specific because the writer is mentioning (a) concrete ideas and (b) exact authors. We can also gather the field (business) and the topic (management and employee turnover). The statement is arguable because the student goes beyond merely comparing; he or she draws conclusions from that comparison ("can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover").

Making a Unique Argument

This thesis draft repeats the language of the writing prompt without making a unique argument:

Needs Improvement: The purpose of this essay is to monitor, assess, and evaluate an educational program for its strengths and weaknesses. Then, I will provide suggestions for improvement.

You can see here that the student has simply stated the paper's assignment, without articulating specifically how he or she will address it. The student can correct this error simply by phrasing the thesis statement as a specific answer to the assignment prompt.

Better: Through a series of student interviews, I found that Kennedy High School's antibullying program was ineffective. In order to address issues of conflict between students, I argue that Kennedy High School should embrace policies outlined by the California Department of Education (2010).

Words like "ineffective" and "argue" show here that the student has clearly thought through the assignment and analyzed the material; he or she is putting forth a specific and debatable position. The concrete information ("student interviews," "antibullying") further prepares the reader for the body of the paper and demonstrates how the student has addressed the assignment prompt without just restating that language.

Creating a Debate

This thesis statement includes only obvious fact or plot summary instead of argument:

Needs Improvement: Leadership is an important quality in nurse educators.

A good strategy to determine if your thesis statement is too broad (and therefore, not arguable) is to ask yourself, "Would a scholar in my field disagree with this point?" Here, we can see easily that no scholar is likely to argue that leadership is an unimportant quality in nurse educators. The student needs to come up with a more arguable claim, and probably a narrower one; remember that a short paper needs a more focused topic than a dissertation.

Better: Roderick's (2009) theory of participatory leadership is particularly appropriate to nurse educators working within the emergency medicine field, where students benefit most from collegial and kinesthetic learning.

Here, the student has identified a particular type of leadership ("participatory leadership"), narrowing the topic, and has made an arguable claim (this type of leadership is "appropriate" to a specific type of nurse educator). Conceivably, a scholar in the nursing field might disagree with this approach. The student's paper can now proceed, providing specific pieces of evidence to support the arguable central claim.

Choosing the Right Words

This thesis statement uses large or scholarly-sounding words that have no real substance:

Needs Improvement: Scholars should work to seize metacognitive outcomes by harnessing discipline-based networks to empower collaborative infrastructures.

There are many words in this sentence that may be buzzwords in the student's field or key terms taken from other texts, but together they do not communicate a clear, specific meaning. Sometimes students think scholarly writing means constructing complex sentences using special language, but actually it's usually a stronger choice to write clear, simple sentences. When in doubt, remember that your ideas should be complex, not your sentence structure.

Better: Ecologists should work to educate the U.S. public on conservation methods by making use of local and national green organizations to create a widespread communication plan.

Notice in the revision that the field is now clear (ecology), and the language has been made much more field-specific ("conservation methods," "green organizations"), so the reader is able to see concretely the ideas the student is communicating.

Leaving Room for Discussion

This thesis statement is not capable of development or advancement in the paper:

Needs Improvement: There are always alternatives to illegal drug use.

This sample thesis statement makes a claim, but it is not a claim that will sustain extended discussion. This claim is the type of claim that might be appropriate for the conclusion of a paper, but in the beginning of the paper, the student is left with nowhere to go. What further points can be made? If there are "always alternatives" to the problem the student is identifying, then why bother developing a paper around that claim? Ideally, a thesis statement should be complex enough to explore over the length of the entire paper.

Better: The most effective treatment plan for methamphetamine addiction may be a combination of pharmacological and cognitive therapy, as argued by Baker (2008), Smith (2009), and Xavier (2011).

In the revised thesis, you can see the student make a specific, debatable claim that has the potential to generate several pages' worth of discussion. When drafting a thesis statement, think about the questions your thesis statement will generate: What follow-up inquiries might a reader have? In the first example, there are almost no additional questions implied, but the revised example allows for a good deal more exploration.

Thesis Mad Libs

If you are having trouble getting started, try using the models below to generate a rough model of a thesis statement! These models are intended for drafting purposes only and should not appear in your final work.

- In this essay, I argue ____, using ______ to assert _____.

- While scholars have often argued ______, I argue______, because_______.

- Through an analysis of ______, I argue ______, which is important because_______.

Words to Avoid and to Embrace

When drafting your thesis statement, avoid words like explore, investigate, learn, compile, summarize , and explain to describe the main purpose of your paper. These words imply a paper that summarizes or "reports," rather than synthesizing and analyzing.

Instead of the terms above, try words like argue, critique, question , and interrogate . These more analytical words may help you begin strongly, by articulating a specific, critical, scholarly position.

Read Kayla's blog post for tips on taking a stand in a well-crafted thesis statement.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Introductions

- Next Page: Conclusions

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

DEAN’S BOOK w/ Prof. CONNIE GRIFFIN

Honors291g-cdg’s blog.

How to Write a Thesis-driven Research Paper

What is a thesis-driven research paper? The formal thesis-driven research paper entails significant research and the use of sources located outside the course materials. Unlike a personal essay, which doesn’t require outside research because it details your feelings and opinions on a topic, a thesis-driven research paper requires you to search out the solution to a problem that you have proposed in the paper’s thesis statement and to present what you have learned through research in a well-written, coherent paper. Following are some rules of thumb to make this possible: • Choose a suitable design and hold on to it: Planning must be a deliberate prelude to writing. o Generate ideas to sketch a plan: Before beginning a first draft, spend some time generating ideas. Think about your subject while relaxing. Write down inspirations. Talk to others about what you plan to write. Collect information and experiment with ways of focusing and organizing it to best reach your readers. o Assess the situation: The key elements of the writing situation include your subject, the sources of information available to you, your purpose, your audience, and constraints such as length, document design, and deadlines. • Make the paragraph the unit of composition: o How to Write a Good Paragraph: • Topic Sentence: Generally, begin each paragraph either with a sentence that suggests the topic or with a sentence that helps the transition. An opening sentence should indicate by its subject the direction the paragraph is to take. As readers move into a paragraph, they need to know where they are – in relation to the whole paper – and what to expect in the sentences to come. • Develop the Main Point: Topic sentences are generalizations in need of support, so once you’ve written a topic sentence, ask yourself, “How do I know this is true?” Your answer will suggest how to develop the paragraph. • Use the active voice: The active voice is usually more direct and vigorous than the passive. For example: Why was the road crossed by the chicken? Compare to: Why did the chicken cross the road? Active voice is direct, bold, clear, and concise. Passive voice occurs when you make the object of an action into the subject of a sentence. For example: The lab assistant weighed the soil samples. Compare to: The soil samples were weighed by the lab assistant, OR, worse yet, The soil samples were weighed. o Occasionally, you should prefer passive voice over active: • Those writing in science and technology often prefer passive voice. This is because they are more interested in what happened, or what was observed, than in who did the observation. • Political writing sometimes prefers passive voice. In any case when the action is more important than the actor, passive voice is fine. • Lawyers sometimes prefer passive voice when, for example, defending a criminal defendant: The car was stolen, RATHER THAN Mr. Smith is charged with stealing the car or, worse yet, Mr. Smith stole the car. Lawyers avoid putting their clients’ names in the same sentence as the crime. • Put statements in positive form: Make definite assertions. Avoid tame, colorless, hesitating, noncommittal language. o He was not very often on time. o COMPARE TO: He usually arrived late. • Use definite, specific, concrete language: o Prefer the specific to the general, the definite to the vague, the concrete to the abstract. • The mayor spoke about the challenges of the future problems concerning the environment and world peace. • The mayor spoke about the challenges of the future problems of famine, pollution, dwindling resources, and arms control. • Omit needless words: Good writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentence. This doesn’t mean that all sentences must be short or avoid all detail. Rather, every word should have a purpose. For example, the word “that.” Add the word that if there is any danger of misreading without it. Otherwise, omit it: The value of a principle is the number of things [that] it will explain. • Use plain English: Avoid legalese or other complex and difficult to understand wording when ordinary English words will work just as well. Use English; not Latin or Greek. Use short (not long) sentences. Keep it simple. Explain – don’t confuse. Long, complicated sentences do not make you appear smarter. Sometimes, in fact, they do just the opposite, demonstrating that you don’t know the topic well enough to paraphrase in simple, concise, understandable language. • Simplify: o Write sentences that are easy to understand and clear. o Don’t write a sentence that needs another sentence to explain it. o Unless a date or location is critical, leave it out. o Use very few, if any, footnotes – they distract. o Don’t overdo it: Sparingly use ALL CAPITALS, italics, bold, and underlining. Use either italics or underlines, but never use both. Don’t use several font types. 12 point Times New Roman font is easiest to read. o Watch the length of your paragraphs: A paragraph should seldom exceed 2/3 of a page. Shorter paragraphs are better. A long paragraph is like a speaker that drones on and on and on and on. . .

Creating a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is the main point you want your readers to accept. It expresses an arguable point and supplies good reasons why readers should accept it. After learning about making an arguable point and supplying good reasons, go to planning the thesis-driven essay .

The Arguable Point

Making a thesis arguable requires a statement that promotes degrees of adherence . In other words, a good thesis takes a stand on an issue in which a range of responses are possible, and no matter what your point is, it will likely produce a range of responses, from strong agreement to strong disagreement. For instance, if you were to argue that the government should fund solar energy development, you have a contention that some will agree with whole-heartedly. Others will disagree just as vigorously. Still others--indeed most--will not have a strong response and might even consider themselves “neutral,” or leaning one way or the other. How well you persuade readers to accept your point depends on the good reasons you have for your position.

Good Reasons

In a nutshell, why should readers accept your point? These reasons are often the “main points” that support your thesis and provide structure to each section of your paper, whether those sections are single paragraphs or groups of paragraphs. Some of the reasons you have for a contention occur to you spontaneously. For instance, you may think that the government should fund solar energy development because solar energy promises to be clean (less pollution) and renewable (the sun should last another five billion years, right?). That’s a good start, but it’s not enough.

While we may spontaneously generate reasons for our central contention, thinking of “the other side” can often help you create an even better thesis. We call this habit of thinking otherwise “dialogical thinking,” because you imagine yourself in dialogue with others. Going back to our example, the contention that the government should fund this enterprise is likely to make some disagree, or at least ask why the government should fund it: shouldn’t companies risk their own money to make this happen? Isn’t that what free-enterprise is all about? Answering those questions can provide more good reasons and lead to a fuller thesis statement:

Because solar technology might be too costly and risky for private industry to develop , the government should fund solar energy development to secure a clean, renewable energy source for our future.

Taken together, the good reasons surrounding this contention can supply the building blocks for the paper: 1) Solar is clean; 2) Solar is renewable; 3) Solar needs vast support to become a reality. You may note that some of your reasons may be easier to prove than others. Most readers will likely agree solar energy is clean and renewable, if proper evidence is presented. The stickier issues may be the ways our society achieves these desirable ends.

Challenging, Grounded, Focused: Recognizing a Good Thesis When You Write One

So a good thesis statement requires an arguable point and good reasons . But how do you know if your thesis will work for the assignment? If it’s challenging , grounded , and properly narrow , it will have promise.

Challenging

We make assertions all the time, but many would not do for a paper in college. These kinds of assertions are either established facts or opinions held on entirely personal grounds. Neither form creates a significant challenge for you nor serves the reader hungry for meaning. Another way that writers avoid challenge is to ask a question instead of asserting a position on a meaningful issue.

A paper often runs into trouble when its thesis is too vague. The terms it uses are too vacuous to set up a specific, disciplined argument.

An overly broad thesis statement might take a hundred pages to support decently, while an overly narrow one can be supported in a paragraph or two.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience by clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Academic Writing Style

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Academic writing refers to a style of expression that researchers use to define the intellectual boundaries of their disciplines and specific areas of expertise. Characteristics of academic writing include a formal tone, use of the third-person rather than first-person perspective (usually), a clear focus on the research problem under investigation, and precise word choice. Like specialist languages adopted in other professions, such as, law or medicine, academic writing is designed to convey agreed meaning about complex ideas or concepts within a community of scholarly experts and practitioners.

Academic Writing. Writing Center. Colorado Technical College; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . New York: Routledge, 2008; Ezza, El-Sadig Y. and Touria Drid. T eaching Academic Writing as a Discipline-Specific Skill in Higher Education . Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2020.

Importance of Good Academic Writing

The accepted form of academic writing in the social sciences can vary considerable depending on the methodological framework and the intended audience. However, most college-level research papers require careful attention to the following stylistic elements:

I. The Big Picture Unlike creative or journalistic writing, the overall structure of academic writing is formal and logical. It must be cohesive and possess a logically organized flow of ideas; this means that the various parts are connected to form a unified whole. There should be narrative links between sentences and paragraphs so that the reader is able to follow your argument. The introduction should include a description of how the rest of the paper is organized and all sources are properly cited throughout the paper.

II. Tone The overall tone refers to the attitude conveyed in a piece of writing. Throughout your paper, it is important that you present the arguments of others fairly and with an appropriate narrative tone. When presenting a position or argument that you disagree with, describe this argument accurately and without loaded or biased language. In academic writing, the author is expected to investigate the research problem from an authoritative point of view. You should, therefore, state the strengths of your arguments confidently, using language that is neutral, not confrontational or dismissive.

III. Diction Diction refers to the choice of words you use. Awareness of the words you use is important because words that have almost the same denotation [dictionary definition] can have very different connotations [implied meanings]. This is particularly true in academic writing because words and terminology can evolve a nuanced meaning that describes a particular idea, concept, or phenomenon derived from the epistemological culture of that discipline [e.g., the concept of rational choice in political science]. Therefore, use concrete words [not general] that convey a specific meaning. If this cannot be done without confusing the reader, then you need to explain what you mean within the context of how that word or phrase is used within a discipline.

IV. Language The investigation of research problems in the social sciences is often complex and multi- dimensional . Therefore, it is important that you use unambiguous language. Well-structured paragraphs and clear topic sentences enable a reader to follow your line of thinking without difficulty. Your language should be concise, formal, and express precisely what you want it to mean. Do not use vague expressions that are not specific or precise enough for the reader to derive exact meaning ["they," "we," "people," "the organization," etc.], abbreviations like 'i.e.' ["in other words"], 'e.g.' ["for example"], or 'a.k.a.' ["also known as"], and the use of unspecific determinate words ["super," "very," "incredible," "huge," etc.].

V. Punctuation Scholars rely on precise words and language to establish the narrative tone of their work and, therefore, punctuation marks are used very deliberately. For example, exclamation points are rarely used to express a heightened tone because it can come across as unsophisticated or over-excited. Dashes should be limited to the insertion of an explanatory comment in a sentence, while hyphens should be limited to connecting prefixes to words [e.g., multi-disciplinary] or when forming compound phrases [e.g., commander-in-chief]. Finally, understand that semi-colons represent a pause that is longer than a comma, but shorter than a period in a sentence. In general, there are four grammatical uses of semi-colons: when a second clause expands or explains the first clause; to describe a sequence of actions or different aspects of the same topic; placed before clauses which begin with "nevertheless", "therefore", "even so," and "for instance”; and, to mark off a series of phrases or clauses which contain commas. If you are not confident about when to use semi-colons [and most of the time, they are not required for proper punctuation], rewrite using shorter sentences or revise the paragraph.

VI. Academic Conventions Among the most important rules and principles of academic engagement of a writing is citing sources in the body of your paper and providing a list of references as either footnotes or endnotes. The academic convention of citing sources facilitates processes of intellectual discovery, critical thinking, and applying a deliberate method of navigating through the scholarly landscape by tracking how cited works are propagated by scholars over time . Aside from citing sources, other academic conventions to follow include the appropriate use of headings and subheadings, properly spelling out acronyms when first used in the text, avoiding slang or colloquial language, avoiding emotive language or unsupported declarative statements, avoiding contractions [e.g., isn't], and using first person and second person pronouns only when necessary.

VII. Evidence-Based Reasoning Assignments often ask you to express your own point of view about the research problem. However, what is valued in academic writing is that statements are based on evidence-based reasoning. This refers to possessing a clear understanding of the pertinent body of knowledge and academic debates that exist within, and often external to, your discipline concerning the topic. You need to support your arguments with evidence from scholarly [i.e., academic or peer-reviewed] sources. It should be an objective stance presented as a logical argument; the quality of the evidence you cite will determine the strength of your argument. The objective is to convince the reader of the validity of your thoughts through a well-documented, coherent, and logically structured piece of writing. This is particularly important when proposing solutions to problems or delineating recommended courses of action.

VIII. Thesis-Driven Academic writing is “thesis-driven,” meaning that the starting point is a particular perspective, idea, or position applied to the chosen topic of investigation, such as, establishing, proving, or disproving solutions to the questions applied to investigating the research problem. Note that a problem statement without the research questions does not qualify as academic writing because simply identifying the research problem does not establish for the reader how you will contribute to solving the problem, what aspects you believe are most critical, or suggest a method for gathering information or data to better understand the problem.

IX. Complexity and Higher-Order Thinking Academic writing addresses complex issues that require higher-order thinking skills applied to understanding the research problem [e.g., critical, reflective, logical, and creative thinking as opposed to, for example, descriptive or prescriptive thinking]. Higher-order thinking skills include cognitive processes that are used to comprehend, solve problems, and express concepts or that describe abstract ideas that cannot be easily acted out, pointed to, or shown with images. Think of your writing this way: One of the most important attributes of a good teacher is the ability to explain complexity in a way that is understandable and relatable to the topic being presented during class. This is also one of the main functions of academic writing--examining and explaining the significance of complex ideas as clearly as possible. As a writer, you must adopt the role of a good teacher by summarizing complex information into a well-organized synthesis of ideas, concepts, and recommendations that contribute to a better understanding of the research problem.

Academic Writing. Writing Center. Colorado Technical College; Hartley, James. Academic Writing and Publishing: A Practical Guide . New York: Routledge, 2008; Murray, Rowena and Sarah Moore. The Handbook of Academic Writing: A Fresh Approach . New York: Open University Press, 2006; Johnson, Roy. Improve Your Writing Skills . Manchester, UK: Clifton Press, 1995; Nygaard, Lynn P. Writing for Scholars: A Practical Guide to Making Sense and Being Heard . Second edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2015; Silvia, Paul J. How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2007; Style, Diction, Tone, and Voice. Writing Center, Wheaton College; Sword, Helen. Stylish Academic Writing . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Strategies for...

Understanding Academic Writing and Its Jargon

The very definition of research jargon is language specific to a particular community of practitioner-researchers . Therefore, in modern university life, jargon represents the specific language and meaning assigned to words and phrases specific to a discipline or area of study. For example, the idea of being rational may hold the same general meaning in both political science and psychology, but its application to understanding and explaining phenomena within the research domain of a each discipline may have subtle differences based upon how scholars in that discipline apply the concept to the theories and practice of their work.