- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Pride Month

A guide to gender identity terms.

Laurel Wamsley

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara, a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity." Kaz Fantone for NPR hide caption

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara, a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity."

Issues of equality and acceptance of transgender and nonbinary people — along with challenges to their rights — have become a major topic in the headlines. These issues can involve words and ideas and identities that are new to some.

That's why we've put together a glossary of terms relating to gender identity. Our goal is to help people communicate accurately and respectfully with one another.

Proper use of gender identity terms, including pronouns, is a crucial way to signal courtesy and acceptance. Alex Schmider , associate director of transgender representation at GLAAD, compares using someone's correct pronouns to pronouncing their name correctly – "a way of respecting them and referring to them in a way that's consistent and true to who they are."

Glossary of gender identity terms

This guide was created with help from GLAAD . We also referenced resources from the National Center for Transgender Equality , the Trans Journalists Association , NLGJA: The Association of LGBTQ Journalists , Human Rights Campaign , InterAct and the American Psychological Association . This guide is not exhaustive, and is Western and U.S.-centric. Other cultures may use different labels and have other conceptions of gender.

One thing to note: Language changes. Some of the terms now in common usage are different from those used in the past to describe similar ideas, identities and experiences. Some people may continue to use terms that are less commonly used now to describe themselves, and some people may use different terms entirely. What's important is recognizing and respecting people as individuals.

Jump to a term: Sex, gender , gender identity , gender expression , cisgender , transgender , nonbinary , agender , gender-expansive , gender transition , gender dysphoria , sexual orientation , intersex

Jump to Pronouns : questions and answers

Sex refers to a person's biological status and is typically assigned at birth, usually on the basis of external anatomy. Sex is typically categorized as male, female or intersex.

Gender is often defined as a social construct of norms, behaviors and roles that varies between societies and over time. Gender is often categorized as male, female or nonbinary.

Gender identity is one's own internal sense of self and their gender, whether that is man, woman, neither or both. Unlike gender expression, gender identity is not outwardly visible to others.

For most people, gender identity aligns with the sex assigned at birth, the American Psychological Association notes. For transgender people, gender identity differs in varying degrees from the sex assigned at birth.

Gender expression is how a person presents gender outwardly, through behavior, clothing, voice or other perceived characteristics. Society identifies these cues as masculine or feminine, although what is considered masculine or feminine changes over time and varies by culture.

Cisgender, or simply cis , is an adjective that describes a person whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Transgender, or simply trans, is an adjective used to describe someone whose gender identity differs from the sex assigned at birth. A transgender man, for example, is someone who was listed as female at birth but whose gender identity is male.

Cisgender and transgender have their origins in Latin-derived prefixes of "cis" and "trans" — cis, meaning "on this side of" and trans, meaning "across from" or "on the other side of." Both adjectives are used to describe experiences of someone's gender identity.

Nonbinary is a term that can be used by people who do not describe themselves or their genders as fitting into the categories of man or woman. A range of terms are used to refer to these experiences; nonbinary and genderqueer are among the terms that are sometimes used.

Agender is an adjective that can describe a person who does not identify as any gender.

Gender-expansive is an adjective that can describe someone with a more flexible gender identity than might be associated with a typical gender binary.

Gender transition is a process a person may take to bring themselves and/or their bodies into alignment with their gender identity. It's not just one step. Transitioning can include any, none or all of the following: telling one's friends, family and co-workers; changing one's name and pronouns; updating legal documents; medical interventions such as hormone therapy; or surgical intervention, often called gender confirmation surgery.

Gender dysphoria refers to psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one's sex assigned at birth and one's gender identity. Not all trans people experience dysphoria, and those who do may experience it at varying levels of intensity.

Gender dysphoria is a diagnosis listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Some argue that such a diagnosis inappropriately pathologizes gender incongruence, while others contend that a diagnosis makes it easier for transgender people to access necessary medical treatment.

Sexual orientation refers to the enduring physical, romantic and/or emotional attraction to members of the same and/or other genders, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and straight orientations.

People don't need to have had specific sexual experiences to know their own sexual orientation. They need not have had any sexual experience at all. They need not be in a relationship, dating or partnered with anyone for their sexual orientation to be validated. For example, if a bisexual woman is partnered with a man, that does not mean she is not still bisexual.

Sexual orientation is separate from gender identity. As GLAAD notes , "Transgender people may be straight, lesbian, gay, bisexual or queer. For example, a person who transitions from male to female and is attracted solely to men would typically identify as a straight woman. A person who transitions from female to male and is attracted solely to men would typically identify as a gay man."

Intersex is an umbrella term used to describe people with differences in reproductive anatomy, chromosomes or hormones that don't fit typical definitions of male and female.

Intersex can refer to a number of natural variations, some of them laid out by InterAct . Being intersex is not the same as being nonbinary or transgender, which are terms typically related to gender identity.

The Picture Show

Nonbinary photographer documents gender dysphoria through a queer lens, pronouns: questions and answers.

What is the role of pronouns in acknowledging someone's gender identity?

Everyone has pronouns that are used when referring to them – and getting those pronouns right is not exclusively a transgender issue.

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara , a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity."

"So, for example, using the correct pronouns for trans and nonbinary youth is a way to let them know that you see them, you affirm them, you accept them and to let them know that they're loved during a time when they're really being targeted by so many discriminatory anti-trans state laws and policies," O'Hara says.

"It's really just about letting someone know that you accept their identity. And it's as simple as that."

Getting the words right is about respect and accuracy, says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality. Kaz Fantone for NPR hide caption

Getting the words right is about respect and accuracy, says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality.

What's the right way to find out a person's pronouns?

Start by giving your own – for example, "My pronouns are she/her."

"If I was introducing myself to someone, I would say, 'I'm Rodrigo. I use him pronouns. What about you?' " says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen , deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality.

O'Hara says, "It may feel awkward at first, but eventually it just becomes another one of those get-to-know-you questions."

Should people be asking everyone their pronouns? Or does it depend on the setting?

Knowing each other's pronouns helps you be sure you have accurate information about another person.

How a person appears in terms of gender expression "doesn't indicate anything about what their gender identity is," GLAAD's Schmider says. By sharing pronouns, "you're going to get to know someone a little better."

And while it can be awkward at first, it can quickly become routine.

Heng-Lehtinen notes that the practice of stating one's pronouns at the bottom of an email or during introductions at a meeting can also relieve some headaches for people whose first names are less common or gender ambiguous.

"Sometimes Americans look at a name and are like, 'I have no idea if I'm supposed to say he or she for this name' — not because the person's trans, but just because the name is of a culture that you don't recognize and you genuinely do not know. So having the pronouns listed saves everyone the headache," Heng-Lehtinen says. "It can be really, really quick once you make a habit of it. And I think it saves a lot of embarrassment for everybody."

Might some people be uncomfortable sharing their pronouns in a public setting?

Schmider says for cisgender people, sharing their pronouns is generally pretty easy – so long as they recognize that they have pronouns and know what they are. For others, it could be more difficult to share their pronouns in places where they don't know people.

But there are still benefits in sharing pronouns, he says. "It's an indication that they understand that gender expression does not equal gender identity, that you're not judging people just based on the way they look and making assumptions about their gender beyond what you actually know about them."

How is "they" used as a singular pronoun?

"They" is already commonly used as a singular pronoun when we are talking about someone, and we don't know who they are, O'Hara notes. Using they/them pronouns for someone you do know simply represents "just a little bit of a switch."

"You're just asking someone to not act as if they don't know you, but to remove gendered language from their vocabulary when they're talking about you," O'Hara says.

"I identify as nonbinary myself and I appear feminine. People often assume that my pronouns are she/her. So they will use those. And I'll just gently correct them and say, hey, you know what, my pronouns are they/them just FYI, for future reference or something like that," they say.

O'Hara says their family and friends still struggle with getting the pronouns right — and sometimes O'Hara struggles to remember others' pronouns, too.

"In my community, in the queer community, with a lot of trans and nonbinary people, we all frequently remind each other or remind ourselves. It's a sort of constant mindfulness where you are always catching up a little bit," they say.

"You might know someone for 10 years, and then they let you know their pronouns have changed. It's going to take you a little while to adjust, and that's fine. It's OK to make those mistakes and correct yourself, and it's OK to gently correct someone else."

What if I make a mistake and misgender someone, or use the wrong words?

Simply apologize and move on.

"I think it's perfectly natural to not know the right words to use at first. We're only human. It takes any of us some time to get to know a new concept," Heng-Lehtinen says. "The important thing is to just be interested in continuing to learn. So if you mess up some language, you just say, 'Oh, I'm so sorry,' correct yourself and move forward. No need to make it any more complicated than that. Doing that really simple gesture of apologizing quickly and moving on shows the other person that you care. And that makes a really big difference."

Why are pronouns typically given in the format "she/her" or "they/them" rather than just "she" or "they"?

The different iterations reflect that pronouns change based on how they're used in a sentence. And the "he/him" format is actually shorter than the previously common "he/him/his" format.

"People used to say all three and then it got down to two," Heng-Lehtinen laughs. He says staff at his organization was recently wondering if the custom will eventually shorten to just one pronoun. "There's no real rule about it. It's absolutely just been habit," he says.

Amid Wave Of Anti-Trans Bills, Trans Reporters Say 'Telling Our Own Stories' Is Vital

But he notes a benefit of using he/him and she/her: He and she rhyme. "If somebody just says he or she, I could very easily mishear that and then still get it wrong."

What does it mean if a person uses the pronouns "he/they" or "she/they"?

"That means that the person uses both pronouns, and you can alternate between those when referring to them. So either pronoun would be fine — and ideally mix it up, use both. It just means that they use both pronouns that they're listing," Heng-Lehtinen says.

Schmider says it depends on the person: "For some people, they don't mind those pronouns being interchanged for them. And for some people, they are using one specific pronoun in one context and another set of pronouns in another, dependent on maybe safety or comfortability."

The best approach, Schmider says, is to listen to how people refer to themselves.

Why might someone's name be different than what's listed on their ID?

Heng-Lehtinen notes that there's a perception when a person comes out as transgender, they change their name and that's that. But the reality is a lot more complicated and expensive when it comes to updating your name on government documents.

"It is not the same process as changing your last name when you get married. There is bizarrely a separate set of rules for when you are changing your name in marriage versus changing your name for any other reason. And it's more difficult in the latter," he says.

"When you're transgender, you might not be able to update all of your government IDs, even though you want to," he says. "I've been out for over a decade. I still have not been able to update all of my documents because the policies are so onerous. I've been able to update my driver's license, Social Security card and passport, but I cannot update my birth certificate."

"Just because a transgender person doesn't have their authentic name on their ID doesn't mean it's not the name that they really use every day," he advises. "So just be mindful to refer to people by the name they really use regardless of their driver's license."

NPR's Danielle Nett contributed to this report.

- gender identity

- transgender

What are gender pronouns and why is it important to use the right ones?

Senior Lecturer in Psychology. Clinical Psychologist, Victoria University

Disclosure statement

Glen Hosking (he/him) does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Victoria University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Gender pronouns are the terms people choose to refer to themselves that reflect their gender identity. These might be he/him, she/her or gender-neutral pronouns such as they/them.

Knowing and using a person’s correct pronouns fosters inclusion, makes people feel respected and valued, and affirms their gender identity.

The difference between sex and gender

While people may use the terms sex and gender interchangeably, they mean different things.

Sex refers to the physical differences between people who are female, male, or intersex. A person typically has their sex assigned at birth based on physiological characteristics , including their genitalia and chromosome composition.

This is distinct from gender, which is a social construct and reflects the social and cultural role of sex within a given community. People often develop their gender identity and gender expression in response to their environment.

While gender has been defined as binary in Western culture, gender is on a broad spectrum; a person may identify at any point within this spectrum or outside of it entirely. Gender is not neatly divided along the binary lines of “man” and “woman”.

Read more: The difference between sex and gender, and why both matter in health research

People may identify with genders that are different from sex assigned at birth, some people do not identify with any gender, while others identify with multiple genders. These identities may include transgender, nonbinary, or gender-neutral.

Only the person themself can determine what their gender identity is, and this can change over time.

Gender neutral pronouns

People who identify outside of a gender binary most often use non-gendered or nonbinary pronouns that are not gender specific. These include they/them/their used in the singular, ze (pronounced “zee”) in place of she/he, and hir (pronounced “here”) in place of his/him/her.

Everyone has the right to use the gender pronouns that match their personal identity. These pronouns may or may not match their gender expression, such as how the person dresses, looks, behaves or what their name is.

Why the right pronouns matter

It’s important people, workplaces and organisations support people’s use of self-identified first names, in place of legal names given at birth, and self-identified pronouns, in place of assumed pronouns based on sex assigned at birth or other’s perceptions of physical appearance.

Being misgendered and/or misnamed may leave the person feeling disrespected, invalidated and dismissed. This can be distressing and threaten the person’s mental health.

Transgender and non binary people are twice as likely to have suicidal thoughts than the general population, and are up to four times as likely to engage in risky substance use.

Read more: Almost half of trans young people try to end their lives. How can we reduce this alarming statistic?

Conversely, using correct pronouns and names reduces depression and suicide risks .

Studies have found that when compared with peers who could not use their chosen name and pronoun, young people who could experienced 71% fewer symptoms of severe depression, a 34% decrease in reported thoughts of suicide and a 65% decrease in suicide attempts.

7 tips for getting pronouns right

The following tips might help you better understand gender pronouns and how you can affirm someone’s gender identity:

1. Don’t assume another person’s gender or gender pronouns

You can’t always know what someone’s gender pronouns are by looking at them, by their name, or by how they dress or behave.

2. Ask a person’s gender pronoun

Asking about and correctly using someone’s gender pronouns is an easy way to show your respect for their identity. Ask a person respectfully and privately what pronoun they use. A simple “Can I ask what pronoun you use?” will usually suffice.

3. Share your own gender pronoun

Normalise the sharing of gender pronouns by actively sharing your own. You can include them after your name in your signature, on your social media accounts or when you introduce yourself in meetings. Normalising the sharing of gender pronouns can be particularly helpful to people who use pronouns outside of the binary.

4. Apologise if you call someone by the wrong pronoun

Mistakes happen and it can be difficult to adjust to using someone’s correct pronouns. If you accidentally misgender someone, apologise and continue the conversation using the correct pronoun.

5. Avoid binary-gendered language

Avoid addressing groups as “ladies and gentleman” or “boys and girls” and address groups of people as “everyone”, “colleagues”, “friends” or “students”. Employers should use gender-neutral language in formal and informal communications.

6. Help others

Help others use a person’s correct pronouns. If a colleague, employer or friend uses an incorrect pronoun, correct them.

7. Practise!

If you’ve not used gender-neutral pronouns such as “they” and “ze” before, give yourself time to practise and get used to them.

Read more: LGBT+ history month: forgotten figures who challenged gender expression and identity centuries ago

- Mental health

- Transgender

- Gender diversity

- Transgender health

Program Manager, Teaching & Learning Initiatives

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

- Social Justice

- Environment

- Health & Happiness

- Get YES! Emails

- Teacher Resources

- Give A Gift Subscription

- Teaching Sustainability

- Teaching Social Justice

- Teaching Respect & Empathy

Student Writing Lessons

- Visual Learning Lessons

- Tough Topics Discussion Guides

- About the YES! for Teachers Program

- Student Writing Contest

Follow YES! For Teachers

- Teaching Respect & Empathy

“Gender Pronouns” Student Writing Lesson

Is there anyone in your life—you included—who is not comfortable being referred to as “he” or “she”? Write a letter to Cole, founder of the Brown Boi Project, on how you feel about this expansion of gender pronoun language. How do you deal with this cultural change?

Students will read and respond to the YES! Magazine article, “‘They’ and the Emotional Weight of Words.”

In this article, Cole, founder of the Brown Boi Project, welcomes the expanding list of gender pronouns. Pronouns can help us all learn to see and respect each other’s identity. Instead of cultivating fear, shame, and embarrassment around not knowing the right thing to say, Cole encourages us to create new approaches to language so we feel freer and more open with each other.

Download lesson as a PDF.

YES! Magazine Article and Writing Prompt

Read the YES! Magazine article by Cole, “‘They’ and the Emotional Weight of Words.”

Writing Prompt:

Society is shifting from a binary “he-she” world to a more fluid spectrum of gender identities. As the story’s author Cole points out, pronouns can be the basis from which all of us learn to see and respect each other’s identity. Some people feel awkward or uncomfortable with this transition, asking questions like, “What’s with this ‘they’ thing?” Others find it freeing.

Students, please respond to the writing prompt below with an up-to-700-word letter to the author: Is there anyone in your life—you included—who is not comfortable being referred to as “he” or “she”? Write a letter to Cole on how you feel about this expansion of gender pronoun language. How do you deal with this cultural change?

Writing Guidelines

The writing guidelines below are intended to be just that—a guide. Please adapt to fit your curriculum.

- Provide an original essay title

- Reference the article

- Limit the essay to no more than 700 words

- Pay attention to grammar and organization

- Be original. provide personal examples and insights

- Demonstrate clarity of content and ideas

- This writing exercise meets several Common Core State Standards for grades 6-12, including W. 9-10.3 and W. 9-10.14 for Writing, and RI. 9-10 and RI. 9-10.2 for Reading: Informational Text.*

*This standard applies to other grade levels. “9-10” is used as an examples.

Evaluation Rubric

Sample Essays

The essays below were selected as winners for the Spring 2017 Student Writing Competition. Please use them as sample essays or mentor text. The ideas, structure, and writing style of these essays may provide inspiration for your own students’ writing—and an excellent platform for analysis and discussion.

“A New Design for Language,” by Alex Gerber, grade 8. Read Alex’s essay about the social and grammatical limits of gender-neutral pronouns—and how to get beyond them.

“The Jintas of Conservative Korean Culture,” by Joanne Yang, grade 8. Read Joanne’s essay about how words should never be allowed to limit who we are.

“Language is a Many-Gendered Thing,” by Ella Martinez, grade 9. Read Ella’s essay about the challenges of using gender-neutral pronouns in a Puerto Rican American family.

“The Right to Be a Little Bit Rude,” by Madeleine Wise, grade 9. Read Madeleine’s essay about overcoming the discomfort of correcting people who use the wrong gender pronouns.

“The Thoughts and Struggle of a Two Spirit,” by Toby Greybear, grade 9. Read Toby’s essay, about embracing a new gender identity—and rediscovering a tradition.

“Existing Openly is Half the Battle,” by Avery Hunt, university. Read Avery’s essay about being the token nonbinary person at college while still learning about their own gender.

We Want to Hear From You!

How do you see this lesson fitting in your curriculum? Already tried it? Tell us—and other teachers—how the lesson worked for you and your students

Please leave your comments below, including what grade you teach.

Related Resources

“Three Things That Matter Most” Student Writing Lesson

“What We Fear” Student Writing Lesson

“Letting Go of Worry” Student Writing Lesson

Get stories of solutions to share with your classroom.

Teachers save 50% on YES! Magazine.

Inspiration in Your Inbox

Get the free daily newsletter from YES! Magazine: Stories of people creating a better world to inspire you and your students.

Using Gender-Neutral Pronouns in Academic Writing

As the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) explains, “Language plays a central role in the way human beings behave and think” (“ Guidelines for Gender–Fair Use of Language” ). With this in mind, it is important to consider how we are precisely and inclusively using individual words. For a thorough set of guidelines and examples of how to use gender–fair language (including creating gender balance and promoting gender equity in pronouns, titles, labels, and names), see this detailed advice from NCTE.

On this page, we focus on one dimension of inclusion and fair–language use: using gender–neutral pronouns when writing about an individual intentionally presented without gendered characteristics, someone with a mix of gendered characteristics, or a person/community who identifies outside the he/she binary. In these academic writing circumstances, using gender–neutral pronouns in your writing is the most appropriate option.

Three Common Gender-Neutral Pronouns

(Table adapted from the one presented in the Gender Neutral Pronoun Blog .)

Choosing Which Gender–Neutral Pronouns to Use

When writing about a person who uses gender–neutral pronouns, there are several ways to figure out which pronouns to use. If you’re writing about a person you can contact, you can ask this individual about pronouns and utilize the pronouns this person uses. For example, if a person uses “ze/hir/hirs,” it is inappropriate to replace those pronouns with “they/them/theirs.” You can also trace the pronouns other writers and researchers have used when writing about your research subject. If you are writing about a person for whom there isn’t consensus around one set of pronouns, we advise using the most current pronouns you find.

Clarifying Your Choices

Some audiences may be unfamiliar with gender–neutral pronouns. One of the ways to communicate with such a readership about your pronoun usage is to add an explanatory footnote after the first application of a gender–neutral pronoun in your paper. This can help readers understand your decisions as a writer. Here are some examples of how to do that.

1 In this paper, I use the self–reported gender pronouns my participants provided, including the gender–neutral pronouns “ze/hir” and “they/them.” For more information, see the UW–Madison LGBT Campus Center guide to pronouns (https://students.wisc.edu/lgbt/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2016/07/LGBTCC-Gender-pronoun-guide.pdf). 1 The narrator of Winterson’s Written on the Body is never given a gendered pronoun or any specific gendered characteristics. To preserve the gender–neutral presentation of the narrator, I am choosing to use “they/them” pronouns in reference to the narrator in my paper.

Works Cited

NCTE. “Guidelines for Gender–Fair Use of Language.” National Council of Teachers of English, revised by Nancy Prosenjak, et al., National Council of Teachers of English, revised ed., 2002, http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/genderfairuseoflang. Accessed 10 Aug. 2017.

“The Need for a Gender–Neutral Pronoun.” Gender Neutral Pronoun Blog. 24 Jan. 2010, https://genderneutralpronoun.wordpress.com/. Accessed 10 Aug. 2017.

Grammar and Punctuation

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Using Dashes

Using Commas

Using Semicolons

Using Coordinating Conjunctions

Using Conjunctive Adverbs

Subject-Verb Agreement

Using Gender–Neutral Pronouns in Academic Writing

How to Proofread

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

Clear, Concise Sentences

Gender-Inclusive Language

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you make decisions about using gendered language in your writing.

What is gendered language, and why should you be aware of it?

You have probably encountered documents that use masculine nouns and pronouns to refer to subject(s) whose gender is unclear or variable, or to groups that contain people who are not actually men. For example, the U.S. Declaration of Independence states that “all men are created equal.” Generations of Americans have been taught that in this context, the word “men” should be read as including both men and women. Other common instances of gendered language include words that assume connections between jobs or roles and gender (like “policeman”) and language conventions that differ depending on the gender of the person being discussed (like using titles that indicate a person’s marital status).

English has changed since the Declaration of Independence was written. Most readers no longer understand the word “man” to be synonymous with “person,” so clear communication requires writers to be more precise. And using gender-neutral language has become standard practice in both journalistic and academic writing, as you’ll see if you consult the style manuals for different academic disciplines (APA, MLA, and Chicago, for example).

Tackling gendered references in your writing can be challenging, especially since there isn’t (and may never be) a universally agreed upon set of concrete guidelines on which to base your decisions. But there are a number of different strategies you can “mix and match” as necessary.

Gendered nouns

“Man” and words ending in “-man” are the most commonly used gendered nouns in English. These words are easy to spot and replace with more neutral language, even in contexts where many readers strongly expect the gendered noun. For example, Star Trek writers developing material for contemporary viewers were able to create a more inclusive version of the famous phrase “where no man has gone before” while still preserving its pleasing rhythm: Star Trek explorers now venture “where no one has gone before.”

Here’s a list of gendered nouns and some alternatives listed below. Check a thesaurus for alternatives to gendered nouns not included in this list.

Sometimes writers modify nouns that refer to jobs or positions to indicate the sex of the person holding that position. This happens most often when the sex of the person goes against conventional expectations. For example, some people may assume, perhaps unconsciously, that doctors are men and that nurses are women. Sentences like “The female doctor walked into the room” or “The male nurse walked into the room” reinforce such assumptions. Unless the sex of the subject is important to the meaning of the sentence, it should be omitted. (Here’s an example where the health care professional’s sex might be relevant: “Some women feel more comfortable seeing female gynecologists.”)

Titles and names

Another example of gendered language is the way the titles “Mr.,” “Miss,” and “Mrs.” are used. “Mr.” can refer to any man, regardless of whether he is single or married, but “Miss” and “Mrs.” define women by whether they are married, which until quite recently meant defining them by their relationships with men. A simple alternative when addressing or referring to a woman is “Ms.” (which doesn’t indicate marital status).

Another note about titles: some college students are in the habit of addressing most women older than them, particularly teachers, as “Mrs.,” regardless of whether the woman in question is married. It’s worth knowing that many female faculty and staff (including married women) prefer to be addressed as “Ms.” or, if the term applies, “Professor” or “Dr.” It should also be noted that “Mx.” is the generally acknowledged gender-neutral honorific if “Professor” or “Dr.” does not apply.

Writers sometimes refer to women using only their first names in contexts where they would typically refer to men by their full names, last names, or titles. But using only a person’s first name is more informal and can suggest a lack of respect. For example, in academic writing, we don’t refer to William Shakespeare as “William” or “Will”; we call him “Shakespeare” or “William Shakespeare.” So we should refer to Jane Austen as “Austen” or “Jane Austen,” not just “Jane.”

Similarly, in situations where you would refer to a man by his full title, you should do the same for a woman. For example, if you wouldn’t speak of American President Reagan “Ronald” or “Ronnie,” avoid referring to British Prime Minister Thatcher as “Margaret” or “Maggie.”

A pronoun is a word that substitutes for a noun. The English language provides pronoun options for references to masculine nouns (for example, “he” can substitute for “Juan”), feminine nouns (“she” can replace “Keisha”), and neutral/non-human nouns (“it” can stand in for “a tree”). But English offers no widely-accepted pronoun choice for gender-neutral, third-person singular nouns that refer to people (“the writer,” “a student,” or “someone”). As we discussed at the beginning of this handout, the practice of using masculine pronouns (“he,” “his,” “him”) as the “default” is outdated and will confuse or offend many readers.

So what can you do when you’re faced with one of those gender-neutral or gender-ambiguous language situations? You have a couple of options.

1. Try making the nouns and pronouns plural

If it works for your particular sentence, using plural forms is often an excellent option. Here’s an example of a sentence that can easily be rephrased:

A student who loses too much sleep may have trouble focusing during [his/her] exams.

If we make “student” plural and adjust the rest of the sentence accordingly, there’s no need for gendered language (and no confusion or loss of meaning):

Students who lose too much sleep may have trouble focusing during their exams.

2. Use “they” as a singular pronoun

Most of the time, the word “they” refers to a plural antecedent. For example,

Because experienced hikers know that weather conditions can change rapidly, they often dress in layers.

But using “they” with a singular antecedent is not a new phenomenon, and while it’s less common in formal writing, it has become quite common in speech. In a conversation, many people would not even notice how “they” is being used here:

Look for the rental car company’s representative at the airport exit; they will be holding a sign with your name on it.

Some people are strongly opposed to the use of “they” with singular antecedents and are likely to react badly to writing that uses this approach. Others argue that “they” should be adopted as English’s standard third-person, gender-neutral pronoun in all writing and speaking contexts. “They” is the most respectful way to be mindful of those of all genders.

What if you’re not sure of someone’s gender?

You may sometimes find yourself needing to refer to a person whose gender you’re uncertain of. Perhaps you are writing a paper about the creator of an ancient text or piece of art whose identity (and therefore gender) is unknown–for example, we are not certain who wrote the 6th-century epic poem “Beowulf.” Perhaps you’re participating in an online discussion forum where the participants are known only by usernames like “PurpleOctopus25” or “I Love Big Yellow Fish.” You could be writing about someone you don’t personally know whose name is not clearly associated with a particular gender—someone named Sam Smith might be Samuel, Samantha, Samson, or something else—or the person’s name might be in a language you’re unfamiliar with (for example, if English is the only language you speak and read, you might have difficulty guessing the gender associated with a Chinese name). Or maybe you’re discussing a person whose name or pronouns have changed or whose gender identity is fluid. Perhaps your subject does not fit neatly into the categories of “man” and “woman” or rejects those categories entirely.

In these situations, in addition to using “they,” you could also try:

- Refer to the person using a descriptive word or phrase: the writer of Beowulf is frequently referred to as “The Beowulf poet” or (in contexts where “Beowulf” is the only poem being discussed) “the poet.”

- If the person is known to you only by a username, repeat the username or follow the standard practices of the forum–PurpleOctopus25 might become Purple or P.O. in subsequent references. (Advice columnists often use a similar strategy; if “I Love Big Yellow Fish” wrote to ask for advice, the columnist’s response might begin with “Dear Fish Lover.”)

- If the person’s name is known, keep using the name rather than substituting a pronoun. Rephrase as necessary to reduce the number of times you must repeat it: “Blogger Sam Smith’s cats have apparently destroyed Smith’s furniture, stolen Smith’s sandwiches, and terrorized Smith, Smith’s dogs, and Smith’s housemate” could become “Blogger Sam Smith’s cats have apparently destroyed couches, stolen sandwiches, and terrorized their human and canine housemates.”

- Do a little research: if you are writing about a public figure of any kind, chances are that others have also written about that person; you may be able to follow their lead. If you see multiple practices, imitate the ones that seem most respectful.

If you’re writing about someone you are in contact with, you can ask how that person would like to be referred to.

What about the content of the paper?

Much discussion about gendered language focuses on choosing the right words, but the kinds of information writers include or omit can also convey values and assumptions about gender. For example, think about the ways Barack and Michelle Obama have been presented in the media. Have you seen many discussions of Barack’s weight, hairstyle, and clothing? Many readers and viewers have pointed out that the appearance of female public figures (not just politicians, but actors, writers, activists, athletes, etc.) is discussed more often, more critically, and in far more detail than the appearance of men in similar roles. This pattern suggests that women’s appearance matters more than men’s does and is interesting and worthy of attention, regardless of the context.

Similarly, have you ever noticed patterns in the way that men’s and women’s relationships with their families are discussed (in person, online, or elsewhere)? When someone describes what a male parent does for his children as “babysitting” or discusses family leave policies without mentioning how they apply to men, you may wonder whether the speaker or writer is assuming that men are not interested in caring for their children.

These kinds of values and assumptions about gender can weaken arguments. In many of your college writing assignments, you’ll be asked to analyze something (an issue, text, event, etc.) and make an evidence-based argument about it. Your readers will critique your arguments in part by assessing the values and assumptions your claims rely on. They may look for evidence of bias, overgeneralization, incomplete knowledge, and so forth. Critically examining the role that gender has played in your decisions about the content of your paper can help you make stronger, more effective arguments that will be persuasive to a wide variety of readers, no matter what your topic is or what position you take.

Checklist for gender-related revisions

As you review your writing, ask yourself the following questions:

- Have you used “man” or “men” or words containing them to refer to people who may not be men?

- Have you used “he,” “him,” “his,” or “himself” to refer to people who may not be men?

- If you have mentioned someone’s sex or gender, was it necessary to do so?

- Do you use any occupational (or other) stereotypes?

- Do you provide the same kinds of information and descriptions when writing about people of different genders?

Perhaps the best test for gender-inclusive language is to imagine a diverse group of people reading your paper. Would each reader feel respected? Envisioning your audience is a critical skill in every writing context, and revising with a focus on gendered language is a perfect opportunity to practice.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

American Psychological Association. 2010. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association . 6th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

University of Chicago Press. 2017. The Chicago Manual of Style , 17th ed. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

Why Are Gender Pronouns So Controversial?

Please try again

Pronouns are small but controversial words, especially regarding gender identity. Myles explores the history of gender pronouns and asks: why do they matter?

This video was co-produced with Peer Health Exchange , a non-profit whose mission is to empower young people with the knowledge, skills, and resources to make healthy decisions. They recently launched selfsea , a peer-to-peer platform with free resources, support, and stories from young people who’ve been there. selfsea is for young people aged 13-18 designed as a safe space to discuss and share knowledge on identity, mental health, and sexual health.

TEACHERS: Guide your students to practice civil discourse about current topics and get practice writing CER (claim, evidence, reasoning) responses. Explore lesson supports.

What are pronouns in the English language?

They are these little words we use to replace the words for people’s names, places, or things. Which are NOUNS. Gender pronouns are the terms people choose to refer to themselves that reflect their gender identity. The most commonly used these days are he/him, she/her, or gender-neutral pronouns such as they/them.

How do pronouns relate to gender identity?

When it comes to pronouns to identify a person, we get into identity and that’s where things get complex – and, often political. The big thing personal pronouns often signal is someone’s gender identity. According to scientists, gender isn’t a rigid he/she binary rooted in the sex a person was assigned at birth. Biology and culture BOTH influence our identity, which can be fluid. That means it’s not carved in stone and can change – and it can also be a spectrum. And gender’s not something anyone can ascribe to you– it’s each person’s internal sense of how they personally identify.

What is transgender?

Some people don’t always identify with the sex they were assigned at birth, or the gender pronouns others use to describe them. Often these folks identify themselves as transgender. They may have been assigned female or male but may not identify with that label.

What is the opposition to gender-neutral pronouns all about?

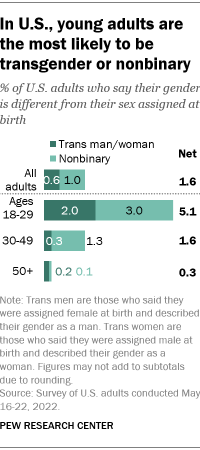

There is a LOT of resistance to using gender-neutral pronouns. In fact, according to Pew Research, almost half of all Americans say they feel “somewhat or very uncomfortable” using they/them pronouns. And the level of discomfort has a lot to do with age, and where you fall on the political spectrum. A common excuse you may see out there is that using “they/them” to describe individual people is “poor grammar.” This isn’t technically correct – people use they/them to describe singular people all the time. As in, “Who parked their car here? They did a terrible job.”

What is the history of gender-neutral pronouns?

There is a long history of people inventing gender-neutral pronouns. One linguist found more than 250 proposed gender-neutral pronouns going back the last few centuries. Examples include “hiser” (1850), “thon” (1858). “ze” (1888) and “hir” (1930) and “ve” (1970). And in 1850, the British Parliament passed a law that the pronoun “He” must be used to describe people of ALL genders. Most of these older language norms have fallen into disuse – but it’s important to note that language is always evolving to reflect new social norms.

Why is it important to respect which pronouns people want to use? Two words: safety and respect. Pronouns signal to the world our gender identity, and part of respecting each other’s humanity is honoring how we all identify.

“ A Guide To Identity Terms ” (NPR, 2021)

“ Beyond He and She: 1 in 4 LGBTQ youths use nonbinary pronouns, survey finds ” (NBC News, 2020)

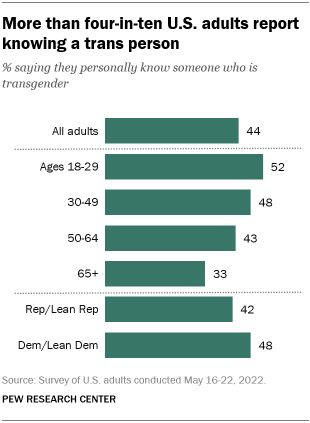

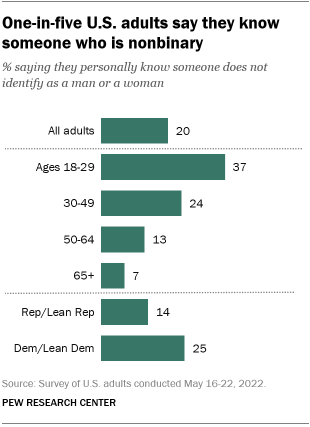

“ About one-in-five U.S. adults know someone who goes by a gender-neutral pronoun ” (Pew Research Center, 2019)

“ The long, long history – and bright future – of the genderless ‘they ’” (Boston Globe, 2018)

“ Pronouns have always been political ” (Medium, 2016)

“ Taking Cues from Texas and Florida, More States Propose Bills Targeting Queer and Trans Youth ” (KQED, 2022)

“ Pronouns and Possibilities: Transgender Language Activism and Reform ” (Language and Social Justice in Practice, 2018)

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.

Take 10% OFF— Expires in h m s Use code save10u during checkout.

Chat with us

- Live Chat Talk to a specialist

- Self-service options

- Search FAQs Fast answers, no waiting

- Ultius 101 New client? Click here

- Messenger

International support numbers

For reference only, subject to Terms and Fair Use policies.

- How it Works

Learn more about us

- Future writers

- Explore further

Ultius Blog

How gender pronouns impact essay writing.

Select network

As the classic Bob Dylan song goes, “The Times They are a Changin’…” Such lyrics could not be truer in today’s world. Politics are polarized and heated debates surround human rights issues such as LGBTQ rights—including the changing use of gender pronouns.

Regardless of one’s personal perspective towards these changing social contexts, transforming gender pronouns signify a language evolution that influences academic essay writing.

If you are a student, it is important to stay current on gender pronoun standards for essay writing to ensure your papers are up to par and graded fairly.

In this post, we will cover everything you need to know about changing gender pronoun standards. We will also talk about how an essay writing service can help provide clarity, including:

- Why and how gender pronouns are changing.

- New societal and academic standards.

- Why gender pronouns matter.

- What this all means for academic essay writing.

- How an essay writing service can help, and where to find a trustworthy essay writing service.

Why gender pronouns are changing

Today, LGBTQ rights are a social and political topic that have gained considerable focus. Despite a societal reinforcement of traditional gender roles, more and more individuals are expressing personal identities outside of traditional gender and sexual identity roles. This includes those identifying themselves as transgender, non-binary, or gender-fluid.

Human rights issues such as women’s rights, gender equality and LGBTQ rights are challenging traditional gender norms and concepts of gender roles. This evolving social climate changes the language used to more accurately describe expressed genders.

Below are some common new terms that you may find it helpful to be aware of.

How gender pronouns are changing

If you engaged in this social conversation, it is helpful to clearly understand new gender-identity related terms. Here are some common terms and phrases you may encounter related to changing expressions of gender and sexual identity.

Common gender and sexual identity terms you may see in academic writing

- The terms lesbian and gay refer to individuals whose sexual preference corresponds to the same gender or sex.

- Bisexual relates to individuals who identify as being interested in both genders or sexes.

- The terms transgender and transsexual refer to individuals who choose to identify as a gender or sex other than the biological sex or gender they were born as.

- Queer generally refers to an individual who does not identify with traditional gender and sexual roles. While once considered a derogatory term, queer is now considered a politically correct term to use when identifying non-normative gender and sexually-oriented individuals.

- Though not included in the acronym, pansexual (being attracted to all sexes and genders regardless of their identity—also known as gender blind ) and asexual (having no sexual feelings or attractions) also fall into the scope of terms describing non-normative, or queer, sexual identities.

- Non-binary: a person or context that is not identified by traditional dualistic male/female gender roles.

- Gender fluid: A person who may identify with both genders, and/or chooses to express themselves as either gender or both genders.

- Gender neutral: A person or context that neither identifies nor gives preference to one gender over another.

- Cisgender: A term used to describe the biologically-identified gender a person is born as.

- Gender non-normative: An individual that falls outside the scope of traditional male / female gender roles.

New gender pronouns

- They: They is often used to describe individuals who do not identify traditionally as he or she , who are gender fluid. They can also be used to refer to gender-neutral individuals.

- Ze: Ze is a new pronoun ( zir being the possessive form) that is used to identify an individual for which the gender is unknown. Ze is often used to refer to individuals who choose to not reveal a specific gender identity.

- Xe: Xe is the plural form of ze and is used to identify groups of gender-unidentified individuals.

New societal standards

The introduction of these new gender pronouns is influencing national and government-level debates about conventional language standards.

They, them, theirs, ze, zirs, hirs and xe , for instance, are being introduced as alternatives to conventional he and she pronouns for use in corporate, public and educational institutions.

For example, some organizations are encouraging staff to use the term partner instead of wife or husband in an effort to strengthen workplace inclusivity. Also, the US Department of Health and Human Services Pride Network recently officially announced They Day . They Day takes place during the first Wednesday of each month and promotes gender diversity awareness.

A hot debate

Changing gender norms have not gone without considerable attention and controversy. For instance, some social rights activists feel it unfair that male gender pronouns are traditionally used to identify groups of gender-diverse people. For example, the US Declaration of Independence states, “all men are created equal.” In this phrase, of course, men refers to people, both male and female. Such language conventions area being called into question.

Many proponents of inclusivity and the use of new gender pronouns feel it is important to recognize and treat non-gender-binary individuals with respect and equality. Individuals who are gender non-normative may find it hurtful to be identified with binary pronouns like he or she that do not accurately reflect their chosen gender preference.

From another perspective, those choosing a more traditional standpoint towards gender expression may find it challenging to understand how non-traditional gender roles fit within the context of society. Some may also be unsure of exactly how to appropriately refer to gender non-normative individuals.

Below, we will help clarify these issues by exploring why gender roles matter, and how and when to use certain gender pronouns.

Why do gender pronouns matter?

Gender pronouns are intimately linked with individuals’ sense of identity. The words, names and pronouns a person self-identifies with are extremely personal. If someone feels they are not being referred to in a way that fits with their personal preference, it can cause one to feel hurt, misunderstood or marginalized.

Yet gender pronouns and categories play an important role in society. Accurate use of gender pronouns is a critical part of culture, society and language. Using correct gender pronouns to understand an individual’s gender can clarify everything from personal identity and legal information, to dating situations, to family health information.

In academia, correct gender-identification is a critical aspect of research involving human subjects. The more researchers understand about subjects, the more accurately results can be described in a non-biased, nondiscriminatory way .

What this means for academic essay writing

So, what does all this gender pronoun talk mean for you as a student? And how does it impact essay writing? Changing gender pronouns impact essay writing in a couple different ways.

First, academic standards are changing to encourage the use of more inclusive language. This means it is important to avoid gender bias when writing academically.

Second, it is important to know when and how to use which gender pronouns. Essay writing services such as Ultius can provide examples of appropriate uses of gender pronouns in academic writing.

New academic standards

The use of correct gender pronouns is part of student wellness, and wellness and academic performance go hand-in-hand. Due to student diversity in academic settings, many universities have embraced inclusivity standards that promote non-biased gender language.

New Guidelines for Gender Fair Use Language, recently published by the NCTE (National Council of Teachers of English), provide a set of standards for using inclusive, non-biased language in academic writing. The New Guidelines document includes rules for using titles, labels, names and pronouns in a way that promotes gender equality.

When to use gender neutral pronouns

There are several pronouns that can be used in situations in which a person’s gender is unidentified or non-binary. The following chart explains the appropriate and grammatically-correct use of three gender neutral pronouns:

If you are unsure of how to identify a person whose gender is nondescript or who uses gender neutral pronouns, consider politely asking the individual what gender pronoun is preferred. In situations in which a person prefers ze , hir or hirs , it is inappropriate to use they , them or theirs . Likewise, when referring to a transgender individual who is a cisgender female but transitioned to a male gender expression, referring to that individual as she is not appropriate. Referring to that individual as he is appropriate. Did you know misgendering is one of the top contemporary issues facing transgender people in America?

If you are unable to ask for clarification, using gender-neutral term such as they is always more correct than making a gender binary assumption and using an exclusively male or female pronoun. Working with an essay writing service while researching and writing can also help clarify how to best use these pronouns.

Here are some additional tips for using gender pronouns in essay writing:

- If in doubt , err on the side of neutrality.

- Use alternate gender pronouns such as those listed above when referring to gender-neutral, gender fluid, non-identified, or non-binary individuals.

- Remember that readers may be unfamiliar with gender-neutral terms . Consider using footnotes to explain new gender identity terms or gender neutral pronouns such as ze used in your paper.

- Explain why you chose to use the gender pronouns you did . For instance, if you use they to describe a gender-diverse audience, use a footnote to explain who the term they applies to. Likewise, if you use a male gender pronoun to describe a gender diverse group, explain the cultural context from which the binary gender pronoun was chosen. For instance, perhaps you used the word mankind because of its traditional use or meaning. Explain this to the reader to avoid unintentional bias.

- Use multiple gender pronouns as indicated by writing “s/he” rather than just “she” or just “he.” This, while still gender binary, leaves the possibilities of gender identity open and keeps your writing inclusive.

- Use these thought-joggers in the table below if you are stumped trying to replace a gender-specific term with a gender-neutral term. Choose an alternate pronoun from the list below:

Finally, while they can serve as a gender-neutral term, some professors may dislike its use in singular situations. For example, using the term they to refer to an individual may be considered grammatically incorrect by some professors. If in doubt, first check with your professor. If you are reprimanded for using they , point for professor to examples and show them knowing the difference is a real word skill .

If you are still feeling unclear, an essay writing service can be a helpful resource to turn to. High quality essay writing services such as Ultius provide assistance from top writers who are skilled in using diverse gender pronouns in a grammatically correct way.

Context and audience matter

In addition to knowing your pronoun options like those listed above, it is also important to consider how context influences essay writing. The class you write your paper for and the audience who will be reading your paper help determine how to use gender pronouns appropriately. Remember, your professor is not your only audience. Although your professor will be grading your paper, you professor will likely grade your paper based on how well you write it to your intended audience. Your intended audience refers to those who the paper applies to.

For example, if you are writing a social justice paper for a women’s studies class, your intended audience will probably be socially liberal individuals who welcome and prefer the use of gender-inclusive language. If you are writing a paper for a Christian university that values traditional, Biblically-referenced gender roles, it is likely best to use binary male/female gender terms.

Before writing, consider the topic and context of your paper. And again, if you are finding it tricky to decipher what type of language to use, consider reaching out to an essay writing service and buy an essay for guidance.

What to do if in doubt

Even when making the best effort to be gender-inclusive and non-biased, changing terminologies can still cause confusion during the writing process.

If you are feeling stuck knowing how to use gender pronouns correctly, try these tips:

- Use a formal name or noun instead of a pronoun . In other words, name the person rather than substituting the name with a pronoun.

- Do some research . If you are writing about a common topic, group of people or individual, check out how other empirical sources have identified the topic, group or person with respect. If you are stuck with the research process, try working with a professional essay writing service.

- Do not be afraid to ask for help . Guidance is a natural and helpful part of the learning process. Essay writing services can provide assistance clarifying the use of gender pronouns. An essay writing service can also help with grammatical editing.

- Use the checklist below as a quick reference.

Gender PC checklist

After you finish writing an essay, use this checklist as a guide to determine whether or not you used gender pronouns as correctly as possible:

- Check your topic and context . Who is your audience? How do they define and view gender roles? How will this impact your use of gender pronouns?

- Search your document for gender binary terms like he , she , him , her , his and hers . Are these terms used in situations that relate to male/female gender roles?

- Did you accurately refer to individuals ’ genders or sexual identities in your paper?

- Were any gender-related opinions you included required by the instructions ? If not, how could you revise your writing to eliminate gender bias?

These checklist items can be somewhat subjective, which is why it can be incredibly helpful to have a second set of eyes review your draft. Essay writing services like Ultius not only provide example essays of how to use gender pronouns correctly, but also offer help editing .

How an essay writing service can help

As language evolves with changing standards, essay writing services can help in a number of ways by:

- Providing guidance about what gender pronouns are most appropriate to use in different contexts, classes, and situations.

- Proofreading essays to ensure new gender pronouns are used in a grammatically correct way.

- Providing example papers that use gender pronouns in a non-discriminatory and unbiased way in alignment with most academic standards.

- Clarifying the tone and voice most politically correct to use, depending on the class, topic and intended audience.

If you are needing for help in any of these areas, you will want to be sure you opt for an essay writing service that is highly rated and trustworthy. Here are a few key considerations.

What to look for in a trustworthy essay writing service

Essay writing services are trustworthy when they meet the right criteria. When choosing an essay writing service, make sure the essay writing service you choose meets these three criteria:

- Hires quality professional writers with a diverse skill set . Top tier essay writing services such as Ultius only hire 6% of the writers who apply. Call the service you are considering and ask how the hiring process takes place.

- Has positive reviews . Avoid essay writing services with picture perfect, 5-star reviews across the board, which may be fabricated. Instead, go for an essay writing service with almost-perfect reviews.

- Free revisions and 24/7 support . You will definitely want the ability to contact essay writing service support 24/7 if you are a college student with a heavy class load.

If you have questions about academic writing standards and what kind of language to use in an essay, an essay writing service can help.

https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/gender-pronouns-impact-essay-writing.html

- Chicago Style

Ultius, Inc. "How Gender Pronouns Impact Essay Writing." Ultius | Custom Writing and Editing Services. Ultius Blog, 09 Aug. 2019. https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/gender-pronouns-impact-essay-writing.html

Copied to clipboard

Click here for more help with MLA citations.

Ultius, Inc. (2019, August 09). How Gender Pronouns Impact Essay Writing. Retrieved from Ultius | Custom Writing and Editing Services, https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/gender-pronouns-impact-essay-writing.html

Click here for more help with APA citations.

Ultius, Inc. "How Gender Pronouns Impact Essay Writing." Ultius | Custom Writing and Editing Services. August 09, 2019 https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/gender-pronouns-impact-essay-writing.html.

Click here for more help with CMS citations.

Click here for more help with Turabian citations.

Ultius is the trusted provider of content solutions and matches customers with highly qualified writers for sample writing, academic editing, and business writing.

Tested Daily

Click to Verify

About The Author

This post was written by Ultius.

- Writer Options

- Custom Writing

- Business Documents

- Support Desk

- +1-800-405-2972

- Submit bug report

- A+ BBB Rating!

Ultius is the trusted provider of content solutions for consumers around the world. Connect with great American writers and get 24/7 support.

© 2024 Ultius, Inc.

- Refund & Cancellation Policy

Free Money For College!

Yeah. You read that right —We're giving away free scholarship money! Our next drawing will be held soon.

Our next winner will receive over $500 in funds. Funds can be used for tuition, books, housing, and/or other school expenses. Apply today for your chance to win!

* We will never share your email with third party advertisers or send you spam.

** By providing my email address, I am consenting to reasonable communications from Ultius regarding the promotion.

Past winner

- Name Samantha M.

- From Pepperdine University '22

- Studies Psychology

- Won $2,000.00

- Award SEED Scholarship

- Awarded Sep. 5, 2018

Thanks for filling that out.

Check your inbox for an email about the scholarship and how to apply.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Gendered Pronouns in Academic Writing

3-minute read

- 6th July 2016

Pronouns – words that can take the place of a noun in a sentence – can be quite controversial in academic writing. Nevertheless, we often need pronouns in our work, particularly when referring to other people.

There is, of course, the issue of using the first person in essays, which we’ve addressed elsewhere . But today we’re focusing on gendered pronouns .

So, what is a gendered pronoun? Should we use them in essays ? And why are they problematic?

Gendered Pronouns

Gendered pronouns refer to a specific gender. In English, this includes the third person pronouns ‘he’ and ‘his’ (male), and ‘she’ and ‘her’ (female).

This is an issue because, until quite recently, academic discourse was very male. Traditionally, therefore, ‘he’ has been used whenever referring to a non-specific individual:

When someone starts a business, he has to make several decisions.

Reasonably enough, the 51% of the population to whom ‘he’ doesn’t apply eventually got bored of this masculine approach. A non-sexist alternative is therefore required.

Gender Neutral Pronouns

It is, of course, fine to use ‘he’ and ‘she’ when referring to particular individuals of a known gender, such as a specific author:

Woolf’s prose style reflects her thematic interests.

But knowing which pronoun to use when referring to a non-specific person is tricky, since there’s no singular, third person gender neutral pronoun in English.

One option is to use the impersonal first person pronoun ‘one’:

When one starts a business, one has to make several decisions.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

This sounds quite old fashioned, though, while using the second person ‘you’ in the same way can seem a little informal. As such, neither is ideal for modern academic writing.

Another possibility is using ‘he or she’ whenever a gendered pronoun would be required:

When someone starts a business, he or she has to make several decisions.

But this can make your writing seem cluttered or awkward, so isn’t always suitable.

Others have invented dedicated gender neutral third person pronouns, such as ‘ze’ or ‘zie’ . However, these are not yet in common use.

The Singular ‘They’

An increasingly popular alternative is to use the third person plural pronouns ‘they’, ‘their’ and ‘them’ to refer to individuals. Technically, this is a non-standard usage, since ‘they’ usually applies to a group:

When wolves hunt, they work in packs.

But it is now often used to refer to an individual when you don’t want to specify a gender:

When someone starts a business, they have to make several decisions.

This neatly avoids forcing the writer to use a gendered pronoun while also being clear and concise.

Nevertheless, since this involves non-standard grammar (the singular ‘someone’ being paired up with the plural verb ‘have’), some consider this use of ‘they’ incorrect. As such, you should always check your style guide for advice on using gendered pronouns if you are unsure.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Get help from a language expert. Try our proofreading services for free.

How to insert a text box in a google doc.

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

What Are the Preferred Gender-Neutral Pronouns in Academic Writing?

Choosing the right pronoun for instances where a person’s gender is unknown or does not conform to the social norms is a topic that has been much discussed and debated. English grammar books explain that English only has the gendered pronouns he and she to refer to an individual in the third person. (The gender-neutral word it is only used for animals or objects; it would be impolite to call a person it .)

This poses a problem in several scenarios. For example, consider that you wish to quote an anonymous survey respondent in your research article. If the respondent’s gender is not reported, should you call the person he or she ? Would the pronoun they suffice in this context, even though they is usually described as the third person plural? Other times, you may wish to write abstractly about someone or anyone . You might also want to refer to each individual in a large group that consists of both men and women. Should you talk about he , she , or they ?

Older texts are likely to use “ he” in such instances. For example, it is common to see sentences like “Every lawyer should bring his briefcase.” Contemporary style guides and editors tend to recommend he or she , although they is quite common, especially in informal contexts and spoken conversation. This article explains the background of the issue as well as current perspectives.

Traditional View and Existing Guidelines

Past generations were taught to default to the masculine pronoun he , called the “generic” or “neutral” he . The idea was that the generic he could represent either a male or female person. This resulted in sentences such as “Every lawyer should bring his briefcase,” as mentioned above. As a result of feminist objections, however, since the 1960s and 1970s, writers have increasingly used the phrase he or she . This phrase explicitly acknowledges the possibility of either a male or female person as the referent.

He or she is the phrase currently recommended by APA and The Chicago Manual of Style when avoidance strategies are insufficient. This is explained in further detail below.

Contemporary Perspectives: Singular they vs. he or she

Linguists point out that the pronoun they is, in fact, a third person singular form widely used in colloquial English when a person’s gender is unknown or simply unspecified, tracing the usage back several centuries (Grey, 2015). In casual conversation, you would sound perfectly natural saying “Somebody forgot their coat.”

The American Dialect Society drew attention to this fact by recognizing the gender-neutral, singular they as the “ word of the year ” for 2015 and has also noted its acceptance by the Washington Post style guide.

As APA blog writer Chelsea Lee points out , researchers in gender studies may object to the binary way of thinking that underlies the phrase he or she . Indeed, some transgender or gender non-conforming individuals may specifically ask to be referred to as they . If they is to be used in this way, it is a good idea to give a brief explanation (e.g., “Casey prefers the pronoun ‘they’”) so that readers do not feel confused.

However, in academic settings overall, using they as a singular form remains a matter of debate. Prestigious journals and publishers prefer traditional grammar and are likely to follow the advice of specific style guides. Therefore, despite the arguments in favor of allowing singular they , editors will probably revise sentences to avoid it or recommend the phrase he or she .

APA recommends avoiding the problem by changing sentences to the plural or eliminating the pronoun altogether. For example, sentence (1) can be revised to (2):

Each participant returned his portfolio.

The participants returned their portfolios. (plural)

Each participant returned a portfolio. (elimination)

These strategies are also suggested by the OWL Purdue and The Chicago Manual of Style. If avoidance strategies do not yield a good sentence, however, APA and The Chicago Manual of Style recommend writing he or she , his or her , etc., as in (4):

Each participant returned his or her portfolio.

Sometimes the two gendered pronouns are combined in writing as “s/he” or “(s)he.” However, having a large number of these spellings in the paper can be distracting. This is particularly true if the author then goes on to write “his/her” and “him/herself.” Having many slashes can give the paper a messy look. Both APA and The Chicago Manual of Style specifically caution writers to avoid such spellings, and APA recommends avoiding other strategies like choosing a pronoun arbitrarily or alternating between them sentence by sentence.

Recommendations

Among academics, the trend is still to use he or she to refer to “somebody,” “anyone,” an anonymous survey respondent, or a person whose gender is unknown. This is very likely the recommendation that will be handed down by the reviewer. Using he or she has the best chance of giving your research article the appropriate tone of conventional grammar while acknowledging both genders. In addition, you can use a robust writing assistant tool like Trinka . It is an AI-powered writing assistant that makes style and tone enhancements as per the APA style guide and helps you choose gender-neutral pronouns by correcting biased and insensitive language to avoid criticism and make your point effectively.

However, it is important to be aware of the issues mentioned above. Too many instances of he or she will make a paragraph wordy and difficult to follow. Therefore, in at least some instances, it is good to choose avoidance through the use of some of APA’s strategies.

Further, some researchers may intentionally use singular they as a reflection of their stance on gendered language or their desire to further the long-standing colloquial usage. The acceptance of singular they appears to be increasing.

Sarah Grey (2015, August 7). Subject-Verb Agreement and the Singular They . Retrieved from https://indiancopyeditors.wixsite.com/copyeditor/single-post/2016-1-22-subjectverb-agreement-and-the-singular-they

Thank you so much for this article. Ladislava from the Czech Republic