- Privacy Policy

Home » Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and Methods

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and Methods

Table of Contents

Evaluating Research

Definition:

Evaluating Research refers to the process of assessing the quality, credibility, and relevance of a research study or project. This involves examining the methods, data, and results of the research in order to determine its validity, reliability, and usefulness. Evaluating research can be done by both experts and non-experts in the field, and involves critical thinking, analysis, and interpretation of the research findings.

Research Evaluating Process

The process of evaluating research typically involves the following steps:

Identify the Research Question

The first step in evaluating research is to identify the research question or problem that the study is addressing. This will help you to determine whether the study is relevant to your needs.

Assess the Study Design

The study design refers to the methodology used to conduct the research. You should assess whether the study design is appropriate for the research question and whether it is likely to produce reliable and valid results.

Evaluate the Sample

The sample refers to the group of participants or subjects who are included in the study. You should evaluate whether the sample size is adequate and whether the participants are representative of the population under study.

Review the Data Collection Methods

You should review the data collection methods used in the study to ensure that they are valid and reliable. This includes assessing the measures used to collect data and the procedures used to collect data.

Examine the Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis refers to the methods used to analyze the data. You should examine whether the statistical analysis is appropriate for the research question and whether it is likely to produce valid and reliable results.

Assess the Conclusions

You should evaluate whether the data support the conclusions drawn from the study and whether they are relevant to the research question.

Consider the Limitations

Finally, you should consider the limitations of the study, including any potential biases or confounding factors that may have influenced the results.

Evaluating Research Methods

Evaluating Research Methods are as follows:

- Peer review: Peer review is a process where experts in the field review a study before it is published. This helps ensure that the study is accurate, valid, and relevant to the field.

- Critical appraisal : Critical appraisal involves systematically evaluating a study based on specific criteria. This helps assess the quality of the study and the reliability of the findings.

- Replication : Replication involves repeating a study to test the validity and reliability of the findings. This can help identify any errors or biases in the original study.

- Meta-analysis : Meta-analysis is a statistical method that combines the results of multiple studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic. This can help identify patterns or inconsistencies across studies.

- Consultation with experts : Consulting with experts in the field can provide valuable insights into the quality and relevance of a study. Experts can also help identify potential limitations or biases in the study.

- Review of funding sources: Examining the funding sources of a study can help identify any potential conflicts of interest or biases that may have influenced the study design or interpretation of results.

Example of Evaluating Research

Example of Evaluating Research sample for students:

Title of the Study: The Effects of Social Media Use on Mental Health among College Students

Sample Size: 500 college students

Sampling Technique : Convenience sampling

- Sample Size: The sample size of 500 college students is a moderate sample size, which could be considered representative of the college student population. However, it would be more representative if the sample size was larger, or if a random sampling technique was used.

- Sampling Technique : Convenience sampling is a non-probability sampling technique, which means that the sample may not be representative of the population. This technique may introduce bias into the study since the participants are self-selected and may not be representative of the entire college student population. Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to other populations.

- Participant Characteristics: The study does not provide any information about the demographic characteristics of the participants, such as age, gender, race, or socioeconomic status. This information is important because social media use and mental health may vary among different demographic groups.

- Data Collection Method: The study used a self-administered survey to collect data. Self-administered surveys may be subject to response bias and may not accurately reflect participants’ actual behaviors and experiences.

- Data Analysis: The study used descriptive statistics and regression analysis to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics provide a summary of the data, while regression analysis is used to examine the relationship between two or more variables. However, the study did not provide information about the statistical significance of the results or the effect sizes.

Overall, while the study provides some insights into the relationship between social media use and mental health among college students, the use of a convenience sampling technique and the lack of information about participant characteristics limit the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the use of self-administered surveys may introduce bias into the study, and the lack of information about the statistical significance of the results limits the interpretation of the findings.

Note*: Above mentioned example is just a sample for students. Do not copy and paste directly into your assignment. Kindly do your own research for academic purposes.

Applications of Evaluating Research

Here are some of the applications of evaluating research:

- Identifying reliable sources : By evaluating research, researchers, students, and other professionals can identify the most reliable sources of information to use in their work. They can determine the quality of research studies, including the methodology, sample size, data analysis, and conclusions.

- Validating findings: Evaluating research can help to validate findings from previous studies. By examining the methodology and results of a study, researchers can determine if the findings are reliable and if they can be used to inform future research.

- Identifying knowledge gaps: Evaluating research can also help to identify gaps in current knowledge. By examining the existing literature on a topic, researchers can determine areas where more research is needed, and they can design studies to address these gaps.

- Improving research quality : Evaluating research can help to improve the quality of future research. By examining the strengths and weaknesses of previous studies, researchers can design better studies and avoid common pitfalls.

- Informing policy and decision-making : Evaluating research is crucial in informing policy and decision-making in many fields. By examining the evidence base for a particular issue, policymakers can make informed decisions that are supported by the best available evidence.

- Enhancing education : Evaluating research is essential in enhancing education. Educators can use research findings to improve teaching methods, curriculum development, and student outcomes.

Purpose of Evaluating Research

Here are some of the key purposes of evaluating research:

- Determine the reliability and validity of research findings : By evaluating research, researchers can determine the quality of the study design, data collection, and analysis. They can determine whether the findings are reliable, valid, and generalizable to other populations.

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of research studies: Evaluating research helps to identify the strengths and weaknesses of research studies, including potential biases, confounding factors, and limitations. This information can help researchers to design better studies in the future.

- Inform evidence-based decision-making: Evaluating research is crucial in informing evidence-based decision-making in many fields, including healthcare, education, and public policy. Policymakers, educators, and clinicians rely on research evidence to make informed decisions.

- Identify research gaps : By evaluating research, researchers can identify gaps in the existing literature and design studies to address these gaps. This process can help to advance knowledge and improve the quality of research in a particular field.

- Ensure research ethics and integrity : Evaluating research helps to ensure that research studies are conducted ethically and with integrity. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines to protect the welfare and rights of study participants and to maintain the trust of the public.

Characteristics Evaluating Research

Characteristics Evaluating Research are as follows:

- Research question/hypothesis: A good research question or hypothesis should be clear, concise, and well-defined. It should address a significant problem or issue in the field and be grounded in relevant theory or prior research.

- Study design: The research design should be appropriate for answering the research question and be clearly described in the study. The study design should also minimize bias and confounding variables.

- Sampling : The sample should be representative of the population of interest and the sampling method should be appropriate for the research question and study design.

- Data collection : The data collection methods should be reliable and valid, and the data should be accurately recorded and analyzed.

- Results : The results should be presented clearly and accurately, and the statistical analysis should be appropriate for the research question and study design.

- Interpretation of results : The interpretation of the results should be based on the data and not influenced by personal biases or preconceptions.

- Generalizability: The study findings should be generalizable to the population of interest and relevant to other settings or contexts.

- Contribution to the field : The study should make a significant contribution to the field and advance our understanding of the research question or issue.

Advantages of Evaluating Research

Evaluating research has several advantages, including:

- Ensuring accuracy and validity : By evaluating research, we can ensure that the research is accurate, valid, and reliable. This ensures that the findings are trustworthy and can be used to inform decision-making.

- Identifying gaps in knowledge : Evaluating research can help identify gaps in knowledge and areas where further research is needed. This can guide future research and help build a stronger evidence base.

- Promoting critical thinking: Evaluating research requires critical thinking skills, which can be applied in other areas of life. By evaluating research, individuals can develop their critical thinking skills and become more discerning consumers of information.

- Improving the quality of research : Evaluating research can help improve the quality of research by identifying areas where improvements can be made. This can lead to more rigorous research methods and better-quality research.

- Informing decision-making: By evaluating research, we can make informed decisions based on the evidence. This is particularly important in fields such as medicine and public health, where decisions can have significant consequences.

- Advancing the field : Evaluating research can help advance the field by identifying new research questions and areas of inquiry. This can lead to the development of new theories and the refinement of existing ones.

Limitations of Evaluating Research

Limitations of Evaluating Research are as follows:

- Time-consuming: Evaluating research can be time-consuming, particularly if the study is complex or requires specialized knowledge. This can be a barrier for individuals who are not experts in the field or who have limited time.

- Subjectivity : Evaluating research can be subjective, as different individuals may have different interpretations of the same study. This can lead to inconsistencies in the evaluation process and make it difficult to compare studies.

- Limited generalizability: The findings of a study may not be generalizable to other populations or contexts. This limits the usefulness of the study and may make it difficult to apply the findings to other settings.

- Publication bias: Research that does not find significant results may be less likely to be published, which can create a bias in the published literature. This can limit the amount of information available for evaluation.

- Lack of transparency: Some studies may not provide enough detail about their methods or results, making it difficult to evaluate their quality or validity.

- Funding bias : Research funded by particular organizations or industries may be biased towards the interests of the funder. This can influence the study design, methods, and interpretation of results.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

- Evaluation Research Design: Examples, Methods & Types

As you engage in tasks, you will need to take intermittent breaks to determine how much progress has been made and if any changes need to be effected along the way. This is very similar to what organizations do when they carry out evaluation research.

The evaluation research methodology has become one of the most important approaches for organizations as they strive to create products, services, and processes that speak to the needs of target users. In this article, we will show you how your organization can conduct successful evaluation research using Formplus .

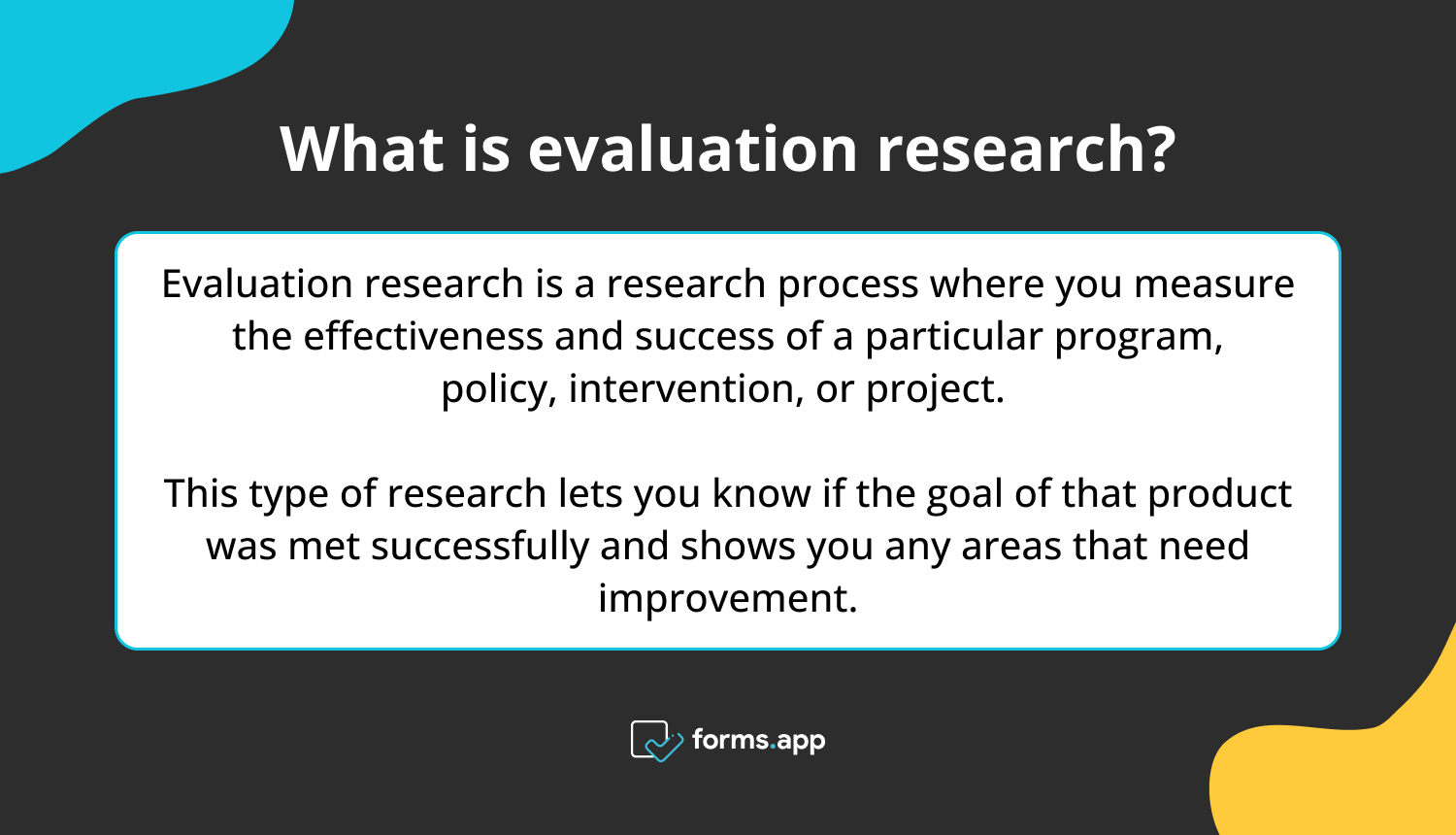

What is Evaluation Research?

Also known as program evaluation, evaluation research is a common research design that entails carrying out a structured assessment of the value of resources committed to a project or specific goal. It often adopts social research methods to gather and analyze useful information about organizational processes and products.

As a type of applied research , evaluation research typically associated with real-life scenarios within organizational contexts. This means that the researcher will need to leverage common workplace skills including interpersonal skills and team play to arrive at objective research findings that will be useful to stakeholders.

Characteristics of Evaluation Research

- Research Environment: Evaluation research is conducted in the real world; that is, within the context of an organization.

- Research Focus: Evaluation research is primarily concerned with measuring the outcomes of a process rather than the process itself.

- Research Outcome: Evaluation research is employed for strategic decision making in organizations.

- Research Goal: The goal of program evaluation is to determine whether a process has yielded the desired result(s).

- This type of research protects the interests of stakeholders in the organization.

- It often represents a middle-ground between pure and applied research.

- Evaluation research is both detailed and continuous. It pays attention to performative processes rather than descriptions.

- Research Process: This research design utilizes qualitative and quantitative research methods to gather relevant data about a product or action-based strategy. These methods include observation, tests, and surveys.

Types of Evaluation Research

The Encyclopedia of Evaluation (Mathison, 2004) treats forty-two different evaluation approaches and models ranging from “appreciative inquiry” to “connoisseurship” to “transformative evaluation”. Common types of evaluation research include the following:

- Formative Evaluation

Formative evaluation or baseline survey is a type of evaluation research that involves assessing the needs of the users or target market before embarking on a project. Formative evaluation is the starting point of evaluation research because it sets the tone of the organization’s project and provides useful insights for other types of evaluation.

- Mid-term Evaluation

Mid-term evaluation entails assessing how far a project has come and determining if it is in line with the set goals and objectives. Mid-term reviews allow the organization to determine if a change or modification of the implementation strategy is necessary, and it also serves for tracking the project.

- Summative Evaluation

This type of evaluation is also known as end-term evaluation of project-completion evaluation and it is conducted immediately after the completion of a project. Here, the researcher examines the value and outputs of the program within the context of the projected results.

Summative evaluation allows the organization to measure the degree of success of a project. Such results can be shared with stakeholders, target markets, and prospective investors.

- Outcome Evaluation

Outcome evaluation is primarily target-audience oriented because it measures the effects of the project, program, or product on the users. This type of evaluation views the outcomes of the project through the lens of the target audience and it often measures changes such as knowledge-improvement, skill acquisition, and increased job efficiency.

- Appreciative Enquiry

Appreciative inquiry is a type of evaluation research that pays attention to result-producing approaches. It is predicated on the belief that an organization will grow in whatever direction its stakeholders pay primary attention to such that if all the attention is focused on problems, identifying them would be easy.

In carrying out appreciative inquiry, the research identifies the factors directly responsible for the positive results realized in the course of a project, analyses the reasons for these results, and intensifies the utilization of these factors.

Evaluation Research Methodology

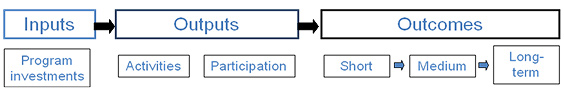

There are four major evaluation research methods, namely; output measurement, input measurement, impact assessment and service quality

- Output/Performance Measurement

Output measurement is a method employed in evaluative research that shows the results of an activity undertaking by an organization. In other words, performance measurement pays attention to the results achieved by the resources invested in a specific activity or organizational process.

More than investing resources in a project, organizations must be able to track the extent to which these resources have yielded results, and this is where performance measurement comes in. Output measurement allows organizations to pay attention to the effectiveness and impact of a process rather than just the process itself.

Other key indicators of performance measurement include user-satisfaction, organizational capacity, market penetration, and facility utilization. In carrying out performance measurement, organizations must identify the parameters that are relevant to the process in question, their industry, and the target markets.

5 Performance Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- What is the cost-effectiveness of this project?

- What is the overall reach of this project?

- How would you rate the market penetration of this project?

- How accessible is the project?

- Is this project time-efficient?

- Input Measurement

In evaluation research, input measurement entails assessing the number of resources committed to a project or goal in any organization. This is one of the most common indicators in evaluation research because it allows organizations to track their investments.

The most common indicator of inputs measurement is the budget which allows organizations to evaluate and limit expenditure for a project. It is also important to measure non-monetary investments like human capital; that is the number of persons needed for successful project execution and production capital.

5 Input Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- What is the budget for this project?

- What is the timeline of this process?

- How many employees have been assigned to this project?

- Do we need to purchase new machinery for this project?

- How many third-parties are collaborators in this project?

- Impact/Outcomes Assessment

In impact assessment, the evaluation researcher focuses on how the product or project affects target markets, both directly and indirectly. Outcomes assessment is somewhat challenging because many times, it is difficult to measure the real-time value and benefits of a project for the users.

In assessing the impact of a process, the evaluation researcher must pay attention to the improvement recorded by the users as a result of the process or project in question. Hence, it makes sense to focus on cognitive and affective changes, expectation-satisfaction, and similar accomplishments of the users.

5 Impact Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- How has this project affected you?

- Has this process affected you positively or negatively?

- What role did this project play in improving your earning power?

- On a scale of 1-10, how excited are you about this project?

- How has this project improved your mental health?

- Service Quality

Service quality is the evaluation research method that accounts for any differences between the expectations of the target markets and their impression of the undertaken project. Hence, it pays attention to the overall service quality assessment carried out by the users.

It is not uncommon for organizations to build the expectations of target markets as they embark on specific projects. Service quality evaluation allows these organizations to track the extent to which the actual product or service delivery fulfils the expectations.

5 Service Quality Evaluation Questions

- On a scale of 1-10, how satisfied are you with the product?

- How helpful was our customer service representative?

- How satisfied are you with the quality of service?

- How long did it take to resolve the issue at hand?

- How likely are you to recommend us to your network?

Uses of Evaluation Research

- Evaluation research is used by organizations to measure the effectiveness of activities and identify areas needing improvement. Findings from evaluation research are key to project and product advancements and are very influential in helping organizations realize their goals efficiently.

- The findings arrived at from evaluation research serve as evidence of the impact of the project embarked on by an organization. This information can be presented to stakeholders, customers, and can also help your organization secure investments for future projects.

- Evaluation research helps organizations to justify their use of limited resources and choose the best alternatives.

- It is also useful in pragmatic goal setting and realization.

- Evaluation research provides detailed insights into projects embarked on by an organization. Essentially, it allows all stakeholders to understand multiple dimensions of a process, and to determine strengths and weaknesses.

- Evaluation research also plays a major role in helping organizations to improve their overall practice and service delivery. This research design allows organizations to weigh existing processes through feedback provided by stakeholders, and this informs better decision making.

- Evaluation research is also instrumental to sustainable capacity building. It helps you to analyze demand patterns and determine whether your organization requires more funds, upskilling or improved operations.

Data Collection Techniques Used in Evaluation Research

In gathering useful data for evaluation research, the researcher often combines quantitative and qualitative research methods . Qualitative research methods allow the researcher to gather information relating to intangible values such as market satisfaction and perception.

On the other hand, quantitative methods are used by the evaluation researcher to assess numerical patterns, that is, quantifiable data. These methods help you measure impact and results; although they may not serve for understanding the context of the process.

Quantitative Methods for Evaluation Research

A survey is a quantitative method that allows you to gather information about a project from a specific group of people. Surveys are largely context-based and limited to target groups who are asked a set of structured questions in line with the predetermined context.

Surveys usually consist of close-ended questions that allow the evaluative researcher to gain insight into several variables including market coverage and customer preferences. Surveys can be carried out physically using paper forms or online through data-gathering platforms like Formplus .

- Questionnaires

A questionnaire is a common quantitative research instrument deployed in evaluation research. Typically, it is an aggregation of different types of questions or prompts which help the researcher to obtain valuable information from respondents.

A poll is a common method of opinion-sampling that allows you to weigh the perception of the public about issues that affect them. The best way to achieve accuracy in polling is by conducting them online using platforms like Formplus.

Polls are often structured as Likert questions and the options provided always account for neutrality or indecision. Conducting a poll allows the evaluation researcher to understand the extent to which the product or service satisfies the needs of the users.

Qualitative Methods for Evaluation Research

- One-on-One Interview

An interview is a structured conversation involving two participants; usually the researcher and the user or a member of the target market. One-on-One interviews can be conducted physically, via the telephone and through video conferencing apps like Zoom and Google Meet.

- Focus Groups

A focus group is a research method that involves interacting with a limited number of persons within your target market, who can provide insights on market perceptions and new products.

- Qualitative Observation

Qualitative observation is a research method that allows the evaluation researcher to gather useful information from the target audience through a variety of subjective approaches. This method is more extensive than quantitative observation because it deals with a smaller sample size, and it also utilizes inductive analysis.

- Case Studies

A case study is a research method that helps the researcher to gain a better understanding of a subject or process. Case studies involve in-depth research into a given subject, to understand its functionalities and successes.

How to Formplus Online Form Builder for Evaluation Survey

- Sign into Formplus

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create your evaluation survey by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on “Create Form ” to begin.

- Edit Form Title

Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Evaluation Research Survey”.

Click on the edit button to edit the form.

Add Fields: Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form in the Formplus builder inputs column. There are several field input options for surveys in the Formplus builder.

Edit fields

Click on “Save”

Preview form.

- Form Customization

With the form customization options in the form builder, you can easily change the outlook of your form and make it more unique and personalized. Formplus allows you to change your form theme, add background images, and even change the font according to your needs.

- Multiple Sharing Options

Formplus offers multiple form sharing options which enables you to easily share your evaluation survey with survey respondents. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your organization’s social media pages.

You can send out your survey form as email invitations to your research subjects too. If you wish, you can share your form’s QR code or embed it on your organization’s website for easy access.

Conclusion

Conducting evaluation research allows organizations to determine the effectiveness of their activities at different phases. This type of research can be carried out using qualitative and quantitative data collection methods including focus groups, observation, telephone and one-on-one interviews, and surveys.

Online surveys created and administered via data collection platforms like Formplus make it easier for you to gather and process information during evaluation research. With Formplus multiple form sharing options, it is even easier for you to gather useful data from target markets.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- characteristics of evaluation research

- evaluation research methods

- types of evaluation research

- what is evaluation research

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Assessment vs Evaluation: 11 Key Differences

This article will discuss what constitutes evaluations and assessments along with the key differences between these two research methods.

What is Pure or Basic Research? + [Examples & Method]

Simple guide on pure or basic research, its methods, characteristics, advantages, and examples in science, medicine, education and psychology

Recall Bias: Definition, Types, Examples & Mitigation

This article will discuss the impact of recall bias in studies and the best ways to avoid them during research.

Formal Assessment: Definition, Types Examples & Benefits

In this article, we will discuss different types and examples of formal evaluation, and show you how to use Formplus for online assessments.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Evaluation Research: Definition, Methods and Examples

Content Index

- What is evaluation research

- Why do evaluation research

Quantitative methods

Qualitative methods.

- Process evaluation research question examples

- Outcome evaluation research question examples

What is evaluation research?

Evaluation research, also known as program evaluation, refers to research purpose instead of a specific method. Evaluation research is the systematic assessment of the worth or merit of time, money, effort and resources spent in order to achieve a goal.

Evaluation research is closely related to but slightly different from more conventional social research . It uses many of the same methods used in traditional social research, but because it takes place within an organizational context, it requires team skills, interpersonal skills, management skills, political smartness, and other research skills that social research does not need much. Evaluation research also requires one to keep in mind the interests of the stakeholders.

Evaluation research is a type of applied research, and so it is intended to have some real-world effect. Many methods like surveys and experiments can be used to do evaluation research. The process of evaluation research consisting of data analysis and reporting is a rigorous, systematic process that involves collecting data about organizations, processes, projects, services, and/or resources. Evaluation research enhances knowledge and decision-making, and leads to practical applications.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Why do evaluation research?

The common goal of most evaluations is to extract meaningful information from the audience and provide valuable insights to evaluators such as sponsors, donors, client-groups, administrators, staff, and other relevant constituencies. Most often, feedback is perceived value as useful if it helps in decision-making. However, evaluation research does not always create an impact that can be applied anywhere else, sometimes they fail to influence short-term decisions. It is also equally true that initially, it might seem to not have any influence, but can have a delayed impact when the situation is more favorable. In spite of this, there is a general agreement that the major goal of evaluation research should be to improve decision-making through the systematic utilization of measurable feedback.

Below are some of the benefits of evaluation research

- Gain insights about a project or program and its operations

Evaluation Research lets you understand what works and what doesn’t, where we were, where we are and where we are headed towards. You can find out the areas of improvement and identify strengths. So, it will help you to figure out what do you need to focus more on and if there are any threats to your business. You can also find out if there are currently hidden sectors in the market that are yet untapped.

- Improve practice

It is essential to gauge your past performance and understand what went wrong in order to deliver better services to your customers. Unless it is a two-way communication, there is no way to improve on what you have to offer. Evaluation research gives an opportunity to your employees and customers to express how they feel and if there’s anything they would like to change. It also lets you modify or adopt a practice such that it increases the chances of success.

- Assess the effects

After evaluating the efforts, you can see how well you are meeting objectives and targets. Evaluations let you measure if the intended benefits are really reaching the targeted audience and if yes, then how effectively.

- Build capacity

Evaluations help you to analyze the demand pattern and predict if you will need more funds, upgrade skills and improve the efficiency of operations. It lets you find the gaps in the production to delivery chain and possible ways to fill them.

Methods of evaluation research

All market research methods involve collecting and analyzing the data, making decisions about the validity of the information and deriving relevant inferences from it. Evaluation research comprises of planning, conducting and analyzing the results which include the use of data collection techniques and applying statistical methods.

Some of the evaluation methods which are quite popular are input measurement, output or performance measurement, impact or outcomes assessment, quality assessment, process evaluation, benchmarking, standards, cost analysis, organizational effectiveness, program evaluation methods, and LIS-centered methods. There are also a few types of evaluations that do not always result in a meaningful assessment such as descriptive studies, formative evaluations, and implementation analysis. Evaluation research is more about information-processing and feedback functions of evaluation.

These methods can be broadly classified as quantitative and qualitative methods.

The outcome of the quantitative research methods is an answer to the questions below and is used to measure anything tangible.

- Who was involved?

- What were the outcomes?

- What was the price?

The best way to collect quantitative data is through surveys , questionnaires , and polls . You can also create pre-tests and post-tests, review existing documents and databases or gather clinical data.

Surveys are used to gather opinions, feedback or ideas of your employees or customers and consist of various question types . They can be conducted by a person face-to-face or by telephone, by mail, or online. Online surveys do not require the intervention of any human and are far more efficient and practical. You can see the survey results on dashboard of research tools and dig deeper using filter criteria based on various factors such as age, gender, location, etc. You can also keep survey logic such as branching, quotas, chain survey, looping, etc in the survey questions and reduce the time to both create and respond to the donor survey . You can also generate a number of reports that involve statistical formulae and present data that can be readily absorbed in the meetings. To learn more about how research tool works and whether it is suitable for you, sign up for a free account now.

Create a free account!

Quantitative data measure the depth and breadth of an initiative, for instance, the number of people who participated in the non-profit event, the number of people who enrolled for a new course at the university. Quantitative data collected before and after a program can show its results and impact.

The accuracy of quantitative data to be used for evaluation research depends on how well the sample represents the population, the ease of analysis, and their consistency. Quantitative methods can fail if the questions are not framed correctly and not distributed to the right audience. Also, quantitative data do not provide an understanding of the context and may not be apt for complex issues.

Learn more: Quantitative Market Research: The Complete Guide

Qualitative research methods are used where quantitative methods cannot solve the research problem , i.e. they are used to measure intangible values. They answer questions such as

- What is the value added?

- How satisfied are you with our service?

- How likely are you to recommend us to your friends?

- What will improve your experience?

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

Qualitative data is collected through observation, interviews, case studies, and focus groups. The steps for creating a qualitative study involve examining, comparing and contrasting, and understanding patterns. Analysts conclude after identification of themes, clustering similar data, and finally reducing to points that make sense.

Observations may help explain behaviors as well as the social context that is generally not discovered by quantitative methods. Observations of behavior and body language can be done by watching a participant, recording audio or video. Structured interviews can be conducted with people alone or in a group under controlled conditions, or they may be asked open-ended qualitative research questions . Qualitative research methods are also used to understand a person’s perceptions and motivations.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

The strength of this method is that group discussion can provide ideas and stimulate memories with topics cascading as discussion occurs. The accuracy of qualitative data depends on how well contextual data explains complex issues and complements quantitative data. It helps get the answer of “why” and “how”, after getting an answer to “what”. The limitations of qualitative data for evaluation research are that they are subjective, time-consuming, costly and difficult to analyze and interpret.

Learn more: Qualitative Market Research: The Complete Guide

Survey software can be used for both the evaluation research methods. You can use above sample questions for evaluation research and send a survey in minutes using research software. Using a tool for research simplifies the process right from creating a survey, importing contacts, distributing the survey and generating reports that aid in research.

Examples of evaluation research

Evaluation research questions lay the foundation of a successful evaluation. They define the topics that will be evaluated. Keeping evaluation questions ready not only saves time and money, but also makes it easier to decide what data to collect, how to analyze it, and how to report it.

Evaluation research questions must be developed and agreed on in the planning stage, however, ready-made research templates can also be used.

Process evaluation research question examples:

- How often do you use our product in a day?

- Were approvals taken from all stakeholders?

- Can you report the issue from the system?

- Can you submit the feedback from the system?

- Was each task done as per the standard operating procedure?

- What were the barriers to the implementation of each task?

- Were any improvement areas discovered?

Outcome evaluation research question examples:

- How satisfied are you with our product?

- Did the program produce intended outcomes?

- What were the unintended outcomes?

- Has the program increased the knowledge of participants?

- Were the participants of the program employable before the course started?

- Do participants of the program have the skills to find a job after the course ended?

- Is the knowledge of participants better compared to those who did not participate in the program?

MORE LIKE THIS

Data Information vs Insight: Essential differences

May 14, 2024

Pricing Analytics Software: Optimize Your Pricing Strategy

May 13, 2024

Relationship Marketing: What It Is, Examples & Top 7 Benefits

May 8, 2024

The Best Email Survey Tool to Boost Your Feedback Game

May 7, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- Library Trends

Evaluation Research: An Overview

- Ronald R. Powell

- Johns Hopkins University Press

- Volume 55, Number 1, Summer 2006

- pp. 102-120

- 10.1353/lib.2006.0050

- View Citation

Additional Information

Evaluation research can be defined as a type of study that uses standard social research methods for evaluative purposes, as a specific research methodology, and as an assessment process that employs special techniques unique to the evaluation of social programs. After the reasons for conducting evaluation research are discussed, the general principles and types are reviewed. Several evaluation methods are then presented, including input measurement, output/performance measurement, impact/outcomes assessment, service quality assessment, process evaluation, benchmarking, standards, quantitative methods, qualitative methods, cost analysis, organizational effectiveness, program evaluation methods, and LIS-centered methods. Other aspects of evaluation research considered are the steps of planning and conducting an evaluation study and the measurement process, including the gathering of statistics and the use of data collection techniques. The process of data analysis and the evaluation report are also given attention. It is concluded that evaluation research should be a rigorous, systematic process that involves collecting data about organizations, processes, programs, services, and/or resources. Evaluation research should enhance knowledge and decision making and lead to practical applications.

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

Learn how to develop a ToC-based evaluation

- Evaluation Goals and Planning

- Identify ToC-Based Questions

- Choose an Evaluation Design

- Select Measures

Choose an Appropriate Evaluation Design

Once you’ve identified your questions, you can select an appropriate evaluation design. Evaluation design refers to the overall approach to gathering information or data to answer specific research questions.

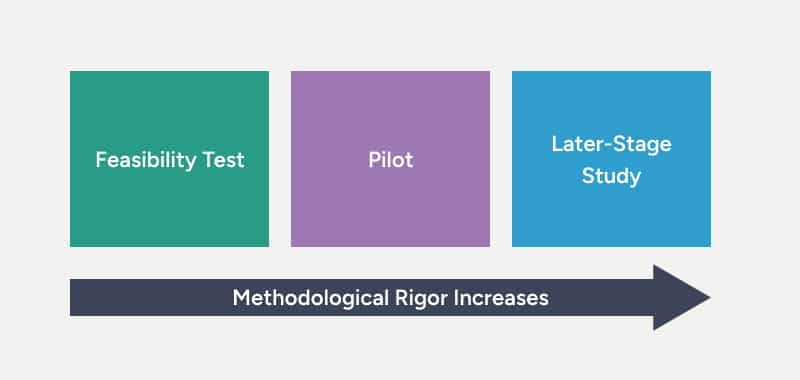

There is a spectrum of research design options—ranging from small-scale feasibility studies (sometimes called road tests) to larger-scale studies that use advanced scientific methodology. Each design option is suited to answer particular research questions.

The appropriate design for a specific project depends on what the project team hopes to learn from a particular implementation and evaluation cycle. Generally, as projects and programs move from small feasibility tests to later stage studies, methodological rigor increases.

In other words, you’ll use more advanced tools and processes that allow you to be more confident in your results. Sample sizes get larger, the number of measurement tools increases, and assessments are often standardized and norm-referenced (designed to compare an individual’s score to a particular population).

In the IDEAS Framework, evaluation is an ongoing, iterative process. The idea is to investigate your ToC one domain at a time, beginning with program strategies and gradually expanding your focus until you’re ready to test the whole theory. Returning to the domino metaphor, we want to see if each domino in the chain is falling the way we expect it to.

Feasibility Study

Begin by asking:

“Are the program strategies feasible and acceptable?”

If you’re designing a program from scratch and implementing it for the first time, you’ll almost always need to begin by establishing feasibility and acceptability. However, suppose you’ve been implementing a program for some time, even without a formal evaluation. In that case, you may have already established feasibility and acceptability simply by demonstrating that the program is possible to implement and that participants feel it’s a good fit. If that’s the case, you might be able to skip over this step, so to speak, and turn your attention to the impact on targets, which we’ll go over in more detail below. On the other hand, for a long-standing program being adapted for a new context or population, you may need to revisit its feasibility and acceptability.

The appropriate evaluation design for answering questions about feasibility and acceptability is typically a feasibility study with a relatively small sample and a simple data collection process.

In this phase, you would collect data on program strategies, including:

- Fidelity data (is the program being implemented as intended?)

- Feedback from participants and program staff (through surveys, focus groups, and interviews)

- Information about recruitment and retention

- Participant demographics (to learn about who you’re serving and whether you’re serving who you intended to serve)

Through fast-cycle iteration, you can use what you learn from a feasibility study to improve the program strategies.

Pilot Study

Once you have evidence to suggest that your strategies are feasible and acceptable, you can take the next step and turn your attention to the impact on targets by asking:

“Is there evidence to suggest that the targets are changing in the anticipated direction?”

The appropriate evaluation design to begin to investigate the impact on targets is usually a pilot study. With a somewhat larger sample and more complex design, pilot studies often gather information from participants before and after they participate in the program. In this phase, you would collect data on program strategies and targets. Note that in each phase, the focus of your evaluation expands to include more domains of your ToC. In a pilot study, in addition to data on targets (your primary focus), you’ll want to gather information on strategies to continue looking at feasibility and acceptability.

In this phase, you would collect data on:

- Program strategies

Later Stage Study

Once you’ve established feasibility and acceptability and have evidence to suggest your targets are changing in the expected direction, you’re ready to ask:

“Is there evidence to support our full theory of change?”

In other words, you’ll simultaneously ask:

- Do our strategies continue to be feasible and acceptable?

- Are the targets changing in the anticipated direction?

- Are the outcomes changing in the anticipated direction?

- Do the moderators help explain variability in impact?

The appropriate evaluation design for investigating your entire theory of change is a later-stage study, with a larger sample and more sophisticated study design, often including some kind of control or comparison group. In this phase, you would collect data on all domains of your ToC: strategies, targets, outcomes, and moderators

Common Questions

There may be cases where it does make sense to skip the earlier steps and move right to a later-stage study. But in most cases, investigating your ToC one domain at a time has several benefits. First, later-stage studies are typically costly in terms of time and money. By starting with a relatively small and low-cost feasibility study and working toward more rigorous evaluation, you can ensure that time and money will be well spent on a program that’s more likely to be effective. If you were to skip ahead to a later-stage study, you might be disappointed to find that your outcomes aren’t changing because of problems with feasibility and acceptability, or because your targets aren’t changing (or aren’t changing enough).

Many programs do gather data on outcomes without looking at strategies and targets. One challenge with that approach is that if you don’t see evidence of impact on program outcomes, you won’t be able to know why that’s the case. Was there a problem with feasibility, and the people implementing the program weren’t able to deliver the program as it was intended? Was there an issue with acceptability, and participants tended to skip sessions or drop out of the program early? Maybe the implementation went smoothly, but the strategies just weren’t effective at changing your targets, and that’s where the causal chain broke down. Unless you gather data on strategies and targets, it’s hard to know what went wrong and what you can do to improve the program’s effectiveness.

Evaluation Research

- First Online: 13 April 2022

Cite this chapter

- Yanmei Li 3 &

- Sumei Zhang 4

854 Accesses

This chapter focuses on evaluation research, which is frequently used in planning and public policy. Evaluation research is often divided into two phases. The first phase is called ex-ante evaluation research and the second phase is the ex-post evaluation research. Ex-ante evaluation research is often referred to feasibility studies prior to implementing a planning project or activity, which often investigates the regulatory, financial, market, and political feasibility of implementing the proposed projects and activities. Data sources and tools of feasibility study are identified in this chapter. The second phase of evaluation research is the ex-post research, which evaluates the outcomes after implementing a planning project or activity. Before-after comparisons, experimental or quasi-experimental methods, goal achievement matrixes, and other measurements are often used in ex-post policy and planning evaluation research. The chapter also explains the differences among cost-benefit analysis, cost-effectiveness analysis, and cost-revenue

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Biamah, E. K., Kiio, J., & Kogo, B. (2013). Chapter 18 – Environmental impact assessment in Kenya. Developments in Earth Surface Processes, 16 , 237–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-59559-1.00018-9

Article Google Scholar

Cao, X., & Wang, D. (2016). Environmental correlates of residential satisfaction: An exploration of mismatched neighborhood characteristics in the Twin Cities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 150 , 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.02.007

Cities Alliance. (2020). Tool 17: Goal Achievement Matrix (GAM) . Accessed on Nov. 20 from: http://city-development.org/tool-17-goal-achievement-matrix-gam/#1472738150329-85a5d0f0-9b68

Dharmadasa, I., Gunaratne, L., Weerasinghe, A. R., & Deheragoda, K. (2015). Solar villages for sustainable development and reduction of poverty . Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA). http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9783

ELAW (Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide). (2020). Chapter 2 – Overview of the EIA process. In Guidebook for evaluating mining project EIAs . Accessed on Nov. 20 from: https://www.elaw.org/files/mining-eia-guidebook/Chapter2.pdf

Freeman, M., & Beale, P. (1992). Measuring project success. Project Management Journal, 23 (1), 8–17.

Google Scholar

Huo, X., Yu, A. T. W., Darko, A., & Wu, Z. (2019). Critical factors in site planning and design of green buildings: A case of China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 222 (10), 685–694.

IISD (International Institute for Sustainable Development). (2020). EIA: 7 steps . Accessed on Nov. 20 from: https://www.iisd.org/learning/eia/eia-7-steps/

Kalisky, S. & Mani, A. (2019). How GIS and machine learning work together . ESRI User Conference, 2019. https://www.esri.com/content/dam/esrisites/en-us/about/events/media/UC-2019/technical-workshops/tw-6165-494.pdf

Kaplan, R. (1985). Nature at the doorstep: Residential satisfaction and the nearby environment. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 2 (2), 115–127.

Patton, C. V., Sawicki, D. S., & Clark, J. J. (2013). Basic methods of policy analysis and planning (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Rentsch, A. (2019). Machine learning for urban planning: Estimating parking capacity. Harvard Data Science Capstone Project, Fall 2019. Towards data science, December 15, 2019. https://towardsdatascience.com/machine-learning-for-urban-planning-estimating-parking-capacity-15aabd490cf8

Ross, S. A., Westerfield, R. W., & Jordan, B. D. (2013). Fundamentals of corporate finance (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

University of Wisconsin-Madison (UWM). (2020). Downtown and Business District market analysis. UWM extension market analysis toolbox. Retrieved on October 22, 2020 from: https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/downtown-market-analysis/

Wholefoodsmarket.com. (2020). Real estate . Retrieved on October 21, 2020 from: https://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/company-info/real-estate

York, P., & Bamberger, M. (2020). Measuring results and impact in the age of big data: The nexus of evaluation, analytics, and digital technology . The Rockefeller Foundation.

Web Resources

Urban Land Institute.: https://uli.org/

Congress for New Urbanism.: https://www.cnu.org/

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.: https://www.hud.gov/

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL, USA

University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA

Sumei Zhang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Electronic Supplementary Material

(docx 23 kb), rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Li, Y., Zhang, S. (2022). Evaluation Research. In: Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93574-0_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93574-0_11

Published : 13 April 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-93573-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-93574-0

eBook Packages : Mathematics and Statistics Mathematics and Statistics (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Research Project Evaluation—Learnings from the PATHWAYS Project Experience

Aleksander galas.

1 Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Jagiellonian University Medical College, 31-034 Krakow, Poland; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (A.P.)

Aleksandra Pilat

Matilde leonardi.

2 Fondazione IRCCS, Neurological Institute Carlo Besta, 20-133 Milano, Italy; [email protected]

Beata Tobiasz-Adamczyk

Background: Every research project faces challenges regarding how to achieve its goals in a timely and effective manner. The purpose of this paper is to present a project evaluation methodology gathered during the implementation of the Participation to Healthy Workplaces and Inclusive Strategies in the Work Sector (the EU PATHWAYS Project). The PATHWAYS project involved multiple countries and multi-cultural aspects of re/integrating chronically ill patients into labor markets in different countries. This paper describes key project’s evaluation issues including: (1) purposes, (2) advisability, (3) tools, (4) implementation, and (5) possible benefits and presents the advantages of a continuous monitoring. Methods: Project evaluation tool to assess structure and resources, process, management and communication, achievements, and outcomes. The project used a mixed evaluation approach and included Strengths (S), Weaknesses (W), Opportunities (O), and Threats (SWOT) analysis. Results: A methodology for longitudinal EU projects’ evaluation is described. The evaluation process allowed to highlight strengths and weaknesses and highlighted good coordination and communication between project partners as well as some key issues such as: the need for a shared glossary covering areas investigated by the project, problematic issues related to the involvement of stakeholders from outside the project, and issues with timing. Numerical SWOT analysis showed improvement in project performance over time. The proportion of participating project partners in the evaluation varied from 100% to 83.3%. Conclusions: There is a need for the implementation of a structured evaluation process in multidisciplinary projects involving different stakeholders in diverse socio-environmental and political conditions. Based on the PATHWAYS experience, a clear monitoring methodology is suggested as essential in every multidisciplinary research projects.

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, a strong discussion on the role of the evaluation process in research has developed, especially in interdisciplinary or multidimensional research [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Despite existing concepts and definitions, the importance of the role of evaluation is often underestimated. These dismissive attitudes towards the evaluation process, along with a lack of real knowledge in this area, demonstrate why we need research evaluation and how research evaluation can improve the quality of research. Having firm definitions of ‘evaluation’ can link the purpose of research, general questions associated with methodological issues, expected results, and the implementation of results to specific strategies or practices.

Attention paid to projects’ evaluation shows two concurrent lines of thought in this area. The first is strongly associated with total quality management practices and operational performance; the second focuses on the evaluation processes needed for public health research and interventions [ 6 , 7 ].

The design and implementation of process’ evaluations in fields different from public health have been described as multidimensional. According to Baranowski and Stables, process evaluation consists of eleven components: recruitment (potential participants for corresponding parts of the program); maintenance (keeping participants involved in the program and data collection); context (an aspect of environment of intervention); resources (the materials necessary to attain project goals); implementation (the extent to which the program is implemented as designed); reach (the extent to which contacts are received by the targeted group); barriers (problems encountered in reaching participants); exposure (the extent to which participants view or read material); initial use (the extent to which a participant conducts activities specified in the materials); continued use (the extent to which a participant continues to do any of the activities); contamination (the extent to which participants receive interventions from outside the program and the extent to which the control group receives the treatment) [ 8 ].

There are two main factors shaping the evaluation process. These are: (1) what is evaluated (whether the evaluation process revolves around project itself or the outcomes which are external to the project), and (2) who is an evaluator (whether an evaluator is internal or external to the project team and program). Although there are several existing gaps in current knowledge about the evaluation process of external outcomes, the use of a formal evaluation process of a research project itself is very rare.

To define a clear evaluation and monitoring methodology we performed different steps. The purpose of this article is to present experiences from the project evaluation process implemented in the Participation to Healthy Workplaces and Inclusive Strategies in the Work Sector (the EU PATHWAYS project. The manuscript describes key project evaluation issues as: (1) purposes, (2) advisability, (3) tools, (4) implementation, and (5) possible benefits. The PATHWAYS project can be understood as a specific case study—presented through a multidimensional approach—and based on the experience associated with general evaluation, we can develop patterns of good practices which can be used in other projects.

1.1. Theoretical Framework

The first step has been the clear definition of what is an evaluation strategy or methodology . The term evaluation is defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as the process of judging something’s quality, importance, or value, or a report that includes this information [ 9 ] or in a similar way by the Oxford Dictionary as the making of a judgment about the amount, number, or value of something [ 10 ]; assessment and in the activity, it is frequently understood as associated with the end rather than with the process. Stufflebeam, in its monograph, defines evaluation as a study designed and conducted to assist some audience to assess an object’s merit and worth. Considering this definition, there are four categories of evaluation approaches: (1) pseudo-evaluation; (2) questions and/or methods-oriented evaluation; (3) improvement/accountability evaluation; (4) social agenda/advocacy evaluation [ 11 ].

In brief, considering Stufflebeam’s classification, pseudo-evaluations promote invalid or incomplete findings. This happens when findings are selectively released or falsified. There are two pseudo-evaluation types proposed by Stufflebeam: (1) public relations-inspired studies (studies which do not seek truth but gather information to solicit positive impressions of program), and (2) politically controlled studies (studies which seek the truth but inappropriately control the release of findings to right-to-know audiences).

The questions and/or methods-oriented approach uses rather narrow questions, which are oriented on operational objectives of the project. Questions oriented uses specific questions, which are of interest by accountability requirements or an expert’s opinions of what is important, while method oriented evaluations favor the technical qualities of program/process. The general concept of these two is that it is better to ask a few pointed questions well to get information on program merit and worth [ 11 ]. In this group, one may find the following evaluation types: (a) objectives-based studies: typically focus on whether the program objectives have been achieved through an internal perspective (by project executors); (b) accountability, particularly payment by results studies: stress the importance of obtaining an external, impartial perspective; (c) objective testing program: uses standardized, multiple-choice, norm-referenced tests; (d) outcome evaluation as value-added assessment: a recurrent evaluation linked with hierarchical gain score analysis; (e) performance testing: incorporates the assessment of performance (by written or spoken answers, or psychomotor presentations) and skills; (f) experimental studies: program evaluators perform a controlled experiment and contrast the outcomes observed; (g) management information system: provide information needed for managers to conduct their programs; (h) benefit-cost analysis approach: mainly sets of quantitative procedures to assess the full cost of a program and its returns; (i) clarification hearing: an evaluation of a trial in which role-playing evaluators competitively implement both a damning prosecution of a program—arguing that it failed, and a defense of the program—and arguing that it succeeded. Next, a judge hears arguments within the framework of a jury trial and controls the proceedings according to advance agreements on rules of evidence and trial procedures; (j) case study evaluation: focused, in-depth description, analysis, and synthesis of a particular program; (k) criticism and connoisseurship: certain experts in a given area do in-depth analysis and evaluation that could not be done in other way; (l) program theory-based evaluation: based on the theory beginning with another validated theory of how programs of a certain type within similar settings operate to produce outcomes (e.g., Health Believe Model, Predisposing, Reinforcing and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation and Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development - thus so called PRECEDE-PROCEED model proposed by L. W. Green or Stage of Change Theory by Prochaska); (m) mixed method studies: include different qualitative and quantitative methods.

The third group of methods considered in evaluation theory are improvement/accountability-oriented evaluation approaches. Among these, there are the following: (a) decision/accountability oriented studies: emphasizes that evaluation should be used proactively to help improve a program and retroactively to assess its merit and worth; (b) consumer-oriented studies: wherein the evaluator is a surrogate consumer who draws direct conclusions about the evaluated program; (c) accreditation/certification approach: an accreditation study to verify whether certification requirements have been/are fulfilled.

Finally, a social agenda/advocacy evaluation approach focuses on the assessment of difference, which is/was intended to be the effect of the program evaluation. The evaluation process in this type of approach works in a loop, starting with an independent evaluator who provides counsel and advice towards understanding, judging and improving programs as evaluations to serve the client’s needs. In this group, there are: (a) client-centered studies (or responsive evaluation): evaluators work with, and for, the support of diverse client groups; (b) constructivist evaluation: evaluators are authorized and expected to maneuver the evaluation to emancipate and empower involved and affected disenfranchised people; (c) deliberative democratic evaluation: evaluators work within an explicit democratic framework and uphold democratic principles in reaching defensible conclusions; (d) utilization-focused evaluation: explicitly geared to ensure that program evaluations make an impact.

1.2. Implementation of the Evaluation Process in the EU PATHWAYS Project

The idea to involve the evaluation process as an integrated goal of the PATHWAYS project was determined by several factors relating to the main goal of the project, defined as a special intervention to existing attitudes to occupational mobility and work activity reintegration of people of working age, suffering from specific chronic conditions into the labor market in 12 European Countries. Participating countries had different cultural and social backgrounds and different pervasive attitudes towards people suffering from chronic conditions.

The components of evaluation processes previously discussed proved helpful when planning the PATHWAYS evaluation, especially in relation to different aspects of environmental contexts. The PATHWAYS project focused on chronic conditions including: mental health issues, neurological diseases, metabolic disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and persons with cancer. Within this group, the project found a hierarchy of patients and social and medical statuses defined by the nature of their health conditions.

According to the project’s monitoring and evaluation plan, the evaluation process followed specific challenges defined by the project’s broad and specific goals and monitored the progress of implementing key components by assessing the effectiveness of consecutive steps and identifying conditions supporting the contextual effectiveness. Another significant aim of the evaluation component on the PATHWAYS project was to recognize the value and effectiveness of using a purposely developed methodology—consisting of a wide set of quantitative and qualitative methods. The triangulation of methods was very useful and provided the opportunity to develop a multidimensional approach to the project [ 12 ].

From the theoretical framework, special attention was paid to the explanation of medical, cultural, social and institutional barriers influencing the chance of employment of chronically ill persons in relation to the characteristics of the participating countries.

Levels of satisfaction with project participation, as well as with expected or achieved results and coping with challenges on local–community levels and macro-social levels, were another source of evaluation.

In the PATHWAYS project, the evaluation was implemented for an unusual purpose. This quasi-experimental design was developed to assess different aspects of the multidimensional project that used a variety of methods (systematic review of literature, content analysis of existing documents, acts, data and reports, surveys on different country-levels, deep interviews) in the different phases of the 3 years. The evaluation monitored each stage of the project and focused on process implementation, with the goal of improving every step of the project. The evaluation process allowed to perform critical assessments and deep analysis of benefits and shortages of the specific phase of the project.

The purpose of the evaluation was to monitor the main steps of the Project, including the expectations associated with a multidimensional, methodological approach used by PATHWAYS partners, as well as improving communication between partners, from different professional and methodological backgrounds involved in the project in all its phases, so as to avoid errors in understanding the specific steps as well as the main goals.

2. Materials and Methods

The paper describes methodology and results gathered during the implementation of Work Package 3, Evaluation of the Participation to Healthy Workplaces and Inclusive Strategies in the Work Sector (the PATHWAYS) project. The work package was intended to keep internal control over the run of the project to achieve timely fulfillment of tasks, milestones, and purpose by all project partners.

2.1. Participants

The project consortium involved 12 partners from 10 different European countries. There were academics (representing cross-disciplinary research including socio-environmental determinants of health, clinicians), institutions actively working for the integration of people with chronic and mental health problems and disability, educational bodies (working in the area of disability and focusing on inclusive education), national health institutes (for rehabilitation of patients with functional and workplace impairments), an institution for inter-professional rehabilitation at a country level (coordinating medical, social, educational, pre-vocational and vocational rehabilitation), a company providing patient-centered services (in neurorehabilitation). All the partners represented vast knowledge and high-level expertise in the area of interest and all agreed with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health-ICF and of the biopsychosocial model of health and functioning. The consortium was created based on the following criteria:

- vision, mission, and activities in the area of project purposes,

- high level of experience in the area (supported by publications) and in doing research (being involved in international projects, collaboration with the coordinator and/or other partners in the past),

- being able to get broad geographical, cultural and socio-political representation from EU countries,

- represent different stakeholder type in the area.

2.2. Project Evaluation Tool

The tool development process involved the following steps:

- (1) Review definitions of ‘evaluation’ and adopt one which consorts best with the reality of public health research area;

- (2) Review evaluation approaches and decide on the content which should be applicable in the public health research;

- (3) Create items to be used in the evaluation tool;

- (4) Decide on implementation timing.

According to the PATHWAYS project protocol, an evaluation tool for the internal project evaluation was required to collect information about: (1) structure and resources; (2) process, management and communication; (3) achievements and/or outcomes and (4) SWOT analysis. A mixed methods approach was chosen. The specific evaluation process purpose and approach are presented in Table 1 .

Evaluation purposes and approaches adopted for the purpose in the PATHWAYS project.

* Open ended questions are not counted here.