- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- March Madness

- AP Top 25 Poll

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Zelenskyy’s unlikely journey, from comedy to wartime leader

FILE - Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy speaks during a media conference at an Eastern Partnership Summit in Brussels, Dec. 15, 2021. (Johanna Geron/ Pool Photo via AP, File)

FILE - Russian President Vladimir Putin, right, and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy arrive for a working session at the Elysee Palace, Dec. 9, 2019, in Paris. (Ian Langsdon/Pool via AP, File)

FILE - Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy surrounded by servicemen as he visits the war-hit Donetsk region, eastern Ukraine, on Oct. 14, 2021. (Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP, File)

In this photo provided by the Ukrainian Presidential Press Office, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy speaks to the nation via his phone in the center of Kyiv, Ukraine, Saturday, Feb. 26, 2022. Russian troops stormed toward Ukraine’s capital Saturday, and street fighting broke out as city officials urged residents to take shelter. The country’s president refused an American offer to evacuate, insisting that he would stay. “The fight is here,” he said. (Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP)

Ukrainian comedian and presidential candidate Volodymyr Zelenskyy performs during a show in Brovary, near Kiev, Ukraine on March 29, 2019. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti, File)

FILE - Ukrainian comedian and presidential candidate Volodymyr Zelenskyy, left, is surrounded by journalists after voting at a polling station, during the presidential elections in Kiev, Ukraine, March. 31, 2019. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti, File)

FILE - Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy takes a selfie at the first congress of his party called Servant of the People in the city Botanical Garden, Kiev, Ukraine, June 9, 2019. (AP Photo/Zoya Shu, File)

FILE - Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy attends a talk with journalists in Kyiv, Ukraine on Oct. 10, 2019. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky, File)

FILE - Ukrainian comedian and presidential candidate Volodymyr Zelenskiy, center, and his wife Olena Zelenska celebrate a victory with their supporters at his headquarters after the second round of presidential elections in Kiev, Ukraine, April 21, 2019. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits, File)

FILE - In this undated file photo provided by the Ukrainian Presidential Press Office, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy looks at a front-line position from a shelter as he visits eastern Ukraine, where the country’s military has been locked in a conflict with Russia-backed separatists. (Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP, File)

- Copy Link copied

WARSAW, Poland (AP) — When Volodymyr Zelenskyy was growing up in southeastern Ukraine, his Jewish family spoke Russian and his father once forbade the younger Zelenskyy from going abroad to study in Israel. Instead, Zelenskyy studied law at home. Upon graduation, he found a new home in movie acting and comedy — rocketing in the 2010s to become one of Ukraine’s top entertainers with the TV series “Servant of the People.”

In it, he portrayed a lovable high school teacher fed up with corrupt politicians who accidentally becomes president.

Fast forward just a few years, and Zelenskyy is the president of Ukraine for real. At times in the runup to the Russian invasion, the comedian-turned-statesman had seemed inconsistent, berating the West for fearmongering one day, and for not doing enough the next. But his bravery and refusal to leave as rockets have rained down on the capital have also made him an unlikely hero to many around the world.

With courage, good humor and grace under fire that has rallied his people and impressed his Western counterparts, the compact, dark-haired, 44-year-old former actor has stayed even though he says he has a target on his back from the Russian invaders.

After an offer from the United States to transport him to safety, Zelenskyy shot back on Saturday: “I need ammunition, not a ride,” he said in Ukrainian, according to a senior American intelligence official with direct knowledge of the conversation.

Russian forces on Saturday were encircling Kyiv in the third day of the war. The chief objective, say military observers, is to reach the capital to depose Zelenskyy and his government and install someone more compliant to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The boldness of Zelenskyy’s stand for Ukraine’s sovereignty might not have been expected from a man whose biggest political liability for many years was the feeling that he was too apt to seek compromise with Moscow. He ran for office in part on a platform that he could negotiate peace with Russia, which had seized Crimea from Ukraine and propped up two pro-Russian separatist regions in 2014, leading to a frozen conflict that had killed an estimated 15,000.

Although Zelenskyy managed a prisoner exchange, the efforts for reconciliation faltered as Putin’s insistence that Ukraine back away from the West became ever more intense, painting the Kyiv government as a nest of extremism run by Washington.

Zelenskyy has used his own history to demonstrate that his is a country of possibility, not the hate-filled polity of Putin’s imagination.

In spite of Ukraine’s dark history of antisemitism, reaching back centuries to Cossack pogroms and the collaboration of some anti-Soviet nationalists with Nazi genocide during World War II, Ukraine after Zelenskyy’s election in 2019 became the only country outside of Israel with both a president and prime minister who were Jewish. (Zelenskyy’s grandfather fought in the Soviet Army against the Nazis, while other family died in the Holocaust.)

Like his TV character, Zelenskyy came to office in a landslide democratic election, defeating a billionaire businessman. He promised to break the power of corrupt oligarchs who haphazardly controlled Ukraine since the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

That this fresh-faced upstart, campaigning primarily on social media, could come out of nowhere to claim the country’s top office likely was disturbing to Putin, who has slowly tamed and corralled his own political opposition in Russia.

Putin’s leading political rival, Alexei Navalny, also a comedic, anti-corruption crusader, was poisoned by Russian secret services in 2020 with a nerve agent applied to his underwear. He was fighting for his life when he was allowed under international diplomatic pressure to leave for Germany for medical treatment, and when doctors there saved him, he chose to go back to Russia despite certain risk.

Navalny, now in a Russian prison, has denounced Putin’s military operation in Ukraine.

Both Zelenskyy and Navalny seem to share a perspective that they must face the consequences of their beliefs, no matter what.

“It’s a frightening experience when you come to visit the president of a neighboring country, your colleague, to support him in a difficult situation, (and) you hear from him that you may never meet him again because he is staying there and will defend his country to the last,” Polish President Andrzej Duda said Friday.

He spent time with Zelenskyy on Wednesday just before the fighting started, one of many political leaders who have met with the Ukrainian president over the past month, including U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris.

Zelenskyy first came to the attention of many Americans during the administration of President Donald Trump, who in a phone call with Zelenskyy in 2019 leaned on him to dig up dirt on then presidential candidate Biden and his son Hunter that could aid Trump’s re-election campaign. That “perfect” phone call, as Trump later called it, resulted in Trump’s impeachment by the House of Representatives on charges of using his office, and the threat of withholding $400 million in authorized military support for Ukraine, for personal political gain.

Zelenskyy refused to criticize Trump’s call, saying he did not want to get involved in another country’s politics.

Putin’s attack, which the Russian president has termed a “special military operation,” began early Thursday. Putin denied for months that he had any intent to invade, and accused Biden of stirring up war hysteria when Biden revealed the numbers of Russian troops and weapons that had been deployed along Ukraine’s borders with Russia and Belarus — surrounding Ukraine on three sides.

Putin justified the attack by saying it was to defend two breakaway districts in eastern Ukraine from “genocide.”

With Russian media presenting such a picture of his country, Zelenskyy recorded a message to Russians to refute the notion that Ukraine is the aggressor and that he is any kind of warmonger: “They told you I ordered an offensive on the Donbas, to shoot, to bomb, that there’s no question about it. But there are questions, and very simple ones. To shoot whom, to bomb what? Donetsk?”

Recounting his many visits and friends in the region — “I’ve seen the faces, the eyes” — he said, “It’s our land, it’s our history. What are we going to fight over, and with whom?”

Unshaven and in olive green khaki shirts, he has taped other messages to his compatriots on the internet in the last few days to bolster morale and to emphasize that he is going nowhere, but will stay to defend Ukraine. “We are here. Honor to Ukraine,” he declares.

In the runup to the Russian invasion, Zelenskyy was critical of President Joe Biden’s open and detailed warnings about Putin’s intentions, saying they were premature and could cause panic. Then after the war began, he has criticized Washington for not doing more to protect Ukraine, including defending it militarily or accelerating its bid to join NATO.

Zelenskyy and his wife, Olena, an architect, have a 17-year-old daughter and 9-year-old son. He said this week that they remained in Ukraine, not joining the exodus of mainly women and children refugees seeking safety abroad.

“The war has transformed the former comedian from a provincial politician with delusions of grandeur into a bona fide statesman,” wrote Melinda Haring of the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center for Foreign Affairs on Friday.

Though he can be faulted for not carrying out political reforms quickly enough and for dragging his feet on hardening Ukraine’s long border with Russia over the last year, Haring said, Zelenskyy “has shown a stiff upper lip. He has demonstrated enormous physical courage, refusing to sit in a bunker but instead traveling openly with soldiers, and an unwavering patriotism that few expected from a Russian speaker from eastern Ukraine.”

“To his great credit, he has been unmovable.”

Associated Press writer Monika Scislowska contributed to this report from Warsaw.

Where Zelensky Comes From

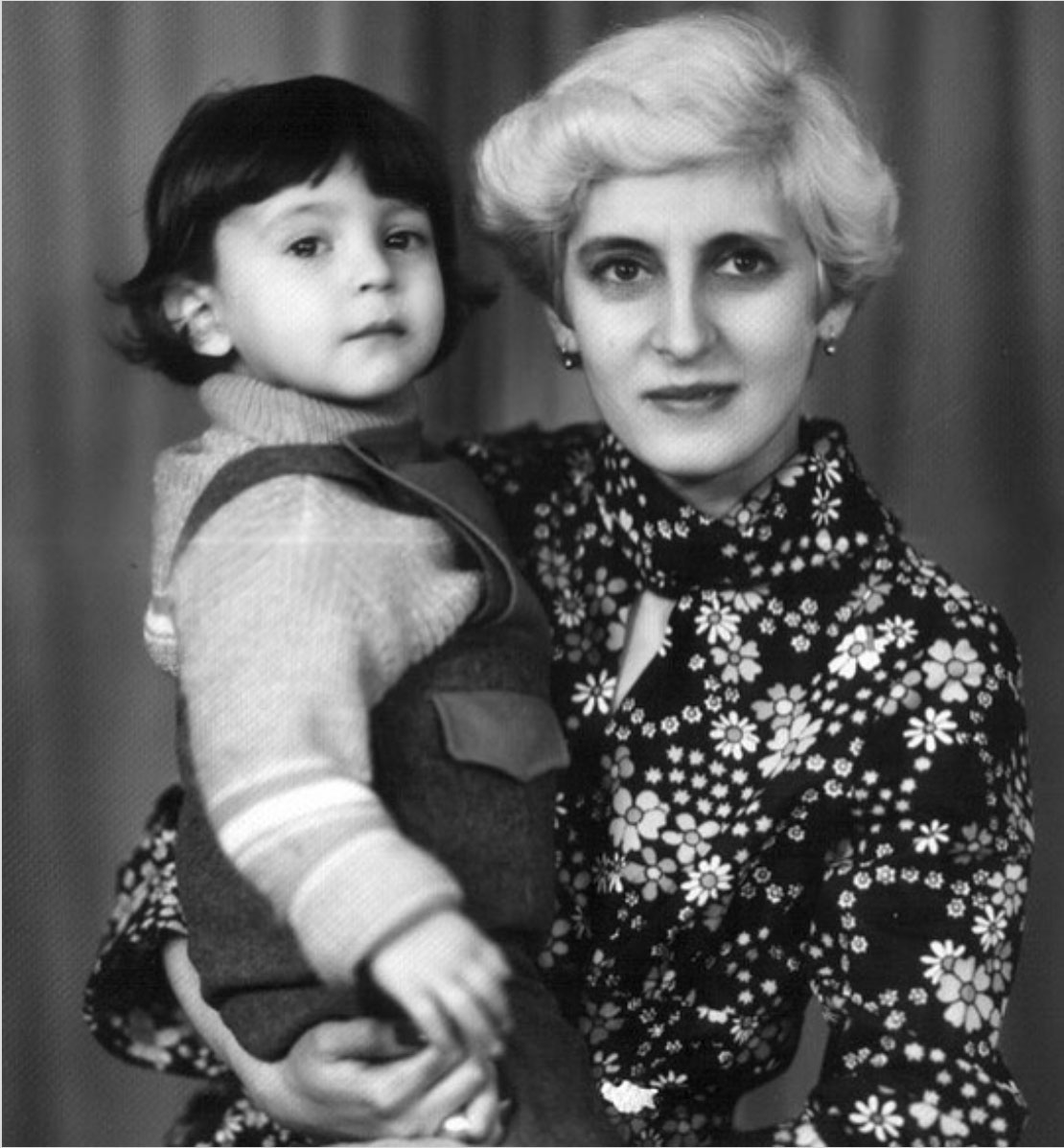

V olodymyr Zelensky was already a celebrity when his first child was born in 2004. Back then, he and his wife Olena Zelenska often lived apart. He spent his days touring and promoting his comedy troupe in Kyiv, while she often stayed with her parents in their hometown of Kryvyi Rih, the city that Zelensky would later credit with forging his character. “My big soul, my big heart,” he once called it. “Everything I have I got from there.”

The name of the town translates as “Crooked Horn,” and in conversation Zelensky and his wife tend to refer to it in Russian as Krivoy—“the crooked place,” where both of them were born in the winter of 1978, about two weeks apart.

Few if any places in Ukraine had a worse reputation in those years for violence and urban decay. The main employer in the city was the metallurgical plant, whose gargantuan blast furnaces churned out more hot steel than any other facility in the Soviet Union. During World War II, the plant was leveled by the Luftwaffe as the Nazis began their occupation of Ukraine. It was rebuilt in the 1950s and ’60s, and many thousands of veterans went to work there. So did convicts released from Soviet labor camps .

Read More: How Volodymyr Zelensky Defended Ukraine and United the World

Most of them settled into blocks of industrial housing, hives of reinforced concrete that offered almost nothing in the way of leisure, culture, or self-development. There were not nearly enough theaters, gyms, or sports facilities to occupy the local kids. By the late 1980s, when the population peaked at over 750,000, the city devolved into what Zelensky would later describe as a “banditsky gorod” —a city of bandits.

More From TIME

Olena remembers it more fondly than that. “It wasn’t full of bandits in my eyes,” she told me. “Maybe boys and girls run in different circles when they’re growing up. But yes, it’s true. There was a period in the ’90s when there was a lot of crime, especially among young people. There were gangs.”

The boys who joined these gangs, mostly teenagers, were known as beguny —literally, “runners”—because groups of them would run through the streets, beating and stabbing their rivals, flipping over cars, and smashing windows. Some of the gangs were known for using homemade explosives and improvised firearms, which they learned to fashion out of metal pipes stuffed with gunpowder and fishhooks. “Some of them got killed,” Olena said. According to local news reports, the death toll reached into the dozens by the mid-1990s.

Many more runners were maimed, beaten with clubs, or blinded with shrapnel from their homemade bombs. “Every neighborhood was in on it,” the First Lady said. “When kids of a certain age wandered into the wrong neighborhood, they could run up against a question: What part of town you from? And then the problems could start.” It was nearly impossible, she said, for teenage boys to avoid joining one of the gangs. “You could even be walking home in your own part of town, and they’d come up and ask what gang you’re with, what are you doing here. Just being on your own was scary. It wasn’t done.”

The gangs had their heyday in the late 1980s, when there were dozens of them around the city, with thousands of runners in all. Many of those who survived into the 1990s graduated into organized crime, which flourished in Kryvyi Rih during the sudden transition from communism to capitalism. Parts of the city turned into wastelands of racketeers and alcoholics. But Zelensky, thanks in large part to his family, avoided the pull of the streets.

His paternal grandfather, Semyon Zelensky, served as a senior officer in the city’s police force, investigating organized crime or, as his grandson later put it, “catching bad guys.” Stories of his service in the Second World War made a profound impression on the young Zelensky, as did the traumas of the Holocaust. Both sides of his family are Jewish, and they lost many of their own during the war.

Read More: Historians on What Putin Gets Wrong About ‘Denazification’ in Ukraine

His mother’s side of the family survived in large part because they were evacuated to Central Asia as the German occupation began in 1941. The following year, when he was still a teenager, Semyon Zelensky went to fight in the Red Army and wound up in command of a mortar platoon. All three of his brothers fought in the war, and none of them survived. Neither did their parents, Zelensky’s great-grandparents, who were killed during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine , along with over a million other Ukrainian Jews, in what became known as the “Holocaust by Bullets.”

Around their kitchen table, Zelensky’s relatives often brought up these tragedies and the crimes of the German occupiers. But little was ever said about the torments that Joseph Stalin inflicted on Ukraine. As a child, Zelensky remembers his grandmothers talking in vague terms about the years when Soviet soldiers came to confiscate the food grown in Ukraine, its vast harvests of grain and wheat all carted away at gunpoint. It was part of Stalin’s attempt in the early 1930s to remake Soviet society, and it led to a catastrophic famine known as the Holodomor —“murder by hunger”—that killed at least 3 million people in Ukraine.

In Soviet schools, the topic was taboo, including the schools where both of Zelensky’s grandmothers worked as teachers; one taught the Ukrainian language, the other taught Russian. When it came to the famine, Zelensky said, “They talked about it very carefully, that there was this period when the state took away everything, all the food.”

If they harbored any ill will toward Soviet authorities, Zelensky’s family knew better than to voice it in public. But his father Oleksandr, a stocky man of stubborn principles, refused throughout his life to join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. “He was categorically against it,” Zelensky told me, “even though that definitely hurt his career.” As a professor of cybernetics, Oleksandr Zelensky worked most of his life in the fields of mining and geology. Zelensky’s mother Rymma, an engineer by training, was closer to their only son and gentler toward him, doting on the boy much more often than she punished him.

In 1982, when Zelensky was 4 years old, his father accepted a prestigious job at a mining development in northern Mongolia, and the family moved to the town of Erdenet, which had been founded only eight years earlier to exploit one of the world’s largest deposits of copper. (The name of the town in Mongolian means “with treasure.”) The job was well paid by Soviet standards, but it forced the family to endure the pollution around the mines and the hardships of life in a frontier town. The food was bland and unfamiliar. Fermented horse milk was a local staple, and the family’s diet was heavy on mutton, with the occasional summer watermelon for which Zelensky and his mother had to stand in line for hours.

Read More: How Ukraine is Pioneering New Ways to Prosecute War Crimes

Rymma, who was slender and frail, with a long nose and beautiful features, found her health deteriorating in the harsh climate, and she soon decided to move back to Ukraine. Zelensky was a first-grader in a Mongolian school, just beginning to pick up the local language, when they traveled home in 1987. His father stayed behind, and for the next 15 years—virtually all of Zelensky’s childhood—he split his time between Erdenet, where he continued to develop his automated system for managing the mines, and Kryvyi Rih, where he taught computer science at a local university. Zelensky’s parents were often separated in those years by five time zones and around 6,000 kilometers. Even at that distance, his father continued to be a dominant presence in Zelensky’s life.

“My parents gave me no free time,” he later said. “They were always signing me up for something.” His father enrolled Zelensky in one of his math courses at the university and began to prime the boy for a career in computer science. His mother sent him to piano lessons, ballroom-dance classes, and gymnastics. To make sure he could hold his own against the local toughs, Zelensky’s parents also got him into a class for Greco-Roman wrestling.

None of these activities were really his choice, but he went along with them out of a sense of duty to his parents. “They were always quick with the discipline,” he said. The approach his father took to education was particularly severe. Zelensky called it “maximalist.” But it was typical of Jewish families in the Soviet Union, who often felt that overachievement was the only way to get a fair shake in a system rigged against them. “You have to be better than everyone else,” Zelensky said in summarizing his parents’ approach to education. “Then there might be a space for you left among the best.”

Zelensky was the product of an era of change. He was too young to experience the Soviet Union as the stagnant, repressive gerontocracy his parents had known. By the time he returned to Ukraine with his mother, the stage was set for the empire’s collapse. Moscow was broke. Its grand experiment in socialism had failed. Mikhail Gorbachev , the reluctant reformer with the soft southern accent, had already begun his doomed attempts to reform the system without breaking it apart.

Even for someone Zelensky’s age, these changes were hard to miss. He could see them in the empty grocery shelves, the endless lines for basic goods, like sausage and toilet paper. And he saw them, clear as day, on television. Under Gorbachev, the censors on Soviet TV became a lot more permissive, reflecting the wider push to relax the state’s control over the media. One of the most popular TV shows of the era was known as KVN, which stands for “The Club of the Funny and Inventive.”

It was a comedy show, but not the kind that most people in the U.S. and Europe would associate with that term. This was not the stand-up of Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy. There was no minimalism here, no lonely cynic at the microphone, breaking taboos. KVN was more like a sports league for young comedians. It involved competing troupes of performers, often made up of college students, doing sketch acts and improv in front of a panel of judges, who decided at the end of the show which team was the funniest.

By the mid-1990s, the average university and many high schools in the Russian-speaking world had at least one KVN team. Many big cities had a dozen or more, all facing off in local competitions and vying for a place in the championship league. The material was mostly wooden, with a lot of knee slappers and humdingers. The teams were also expected to sing and dance. Still, in its own hokey way, KVN could be fun to watch. For Zelensky and his friends, it was an obsession.

Read More: Inside Zelensky’s World

Most of them went to School No. 95, about a block from the central bazaar in their hometown, and not far from the university where Zelensky’s father worked as a professor. Between classes and after school, they rehearsed sketches and comedy routines, riffing off the ones they saw in the professional league on TV. “We loved it all, the KVN, the humor, and we just did it for the soul, for the fun of it,” said Vadym Pereverzev, who met Zelensky in their seventh-grade English class.

The top KVN competitions in Moscow also offered a ticket to stardom that seemed a lot more accessible to them than Hollywood, and a lot more fun than the careers available to kids in a dead-end town like theirs. “It was a rough, working-class place, and you just wanted to escape,” Pereverzev told me. “I think that was one of our main motivations.”

Their amateur shows in the school auditorium soon got the attention of a local comedy troupe that performed at a theater for college students. One of them, Oleksandr Pikalov, a handsome kid with an infectious, dimply smile, came down to School No. 95 to scout the talent. He happened upon a rehearsal in which Zelensky played a fried egg, with something stuffed under his shirt to represent the yolk. The act impressed Pikalov, and they soon began performing together.

Two years older and already in college, Pikalov introduced Zelensky to a few of the movers and shakers from the local comedy scene, including the Shefir brothers, Boris and Serhiy, who were both around 30 years old at the time. They saw Zelensky’s potential, and they became his lifelong friends, mentors, producers, and, eventually, political advisers.

Around their neighborhood in the 1990s, Zelensky’s crew stood out from the start. Instead of the track pants and leather jackets that local hoodlums wore to school, their look was a kind of ’50s retro: plaid blazers and polka-dot ties, slacks with suspenders, pressed white shirts, long hair slicked back with too much gel. Zelensky wore a ring in his ear. At a time when Nirvana was on the radio, he and his friends sang Beatles songs and listened to old-timey rock ’n’ roll.

To them this felt like a form of rebellion, mostly because it was their own. Nobody acted like that in their city, and it didn’t always go over well. Once, in his late teens, Zelensky wanted to try busking in an underpass with his guitar. He had seen people do it in the movies. It looked romantic. But Pikalov warned him that he wouldn’t make it past the second song before somebody came over to kick his ass.

“Sure enough, half an hour goes by,” Pikalov told me. “Somebody comes over and busts the guitar.” But Zelensky was laughing. He had won the bet. “He said he made it through the third song.”

Soon his performances caught the attention of his future wife, Olena. The two of them had crossed paths in the hallways of School No. 95 in Kryvyi Rih. But their homeroom classes were rivals—“like the Montagues and the Capulets,” she once told the Guardian. It was only after graduation, when Zelensky was on his way to becoming a local celebrity, that they took a liking to each other.

Olena was also involved in the KVN scene. To make the connection, Pikalov, their mutual friend, borrowed a videocassette from her, a copy of Basic Instinct, and Zelensky used it as an excuse to visit her at home and return the tape. “Then we became more than friends,” she later told me. “We were also creative colleagues.” Their performances began winning competitions around Kryvyi Rih and in other parts of Ukraine. “We were together all the time,” Olena said. “And everything sort of developed in parallel.”

Their big break came at the end of 1997, when they performed at an international KVN contest in Moscow. More than 200 teams took part from around the former Soviet Union, and Zelensky’s team, then called Transit, tied for first place with a rival team from Armenia. It was a remarkable debut for Zelensky, but he felt robbed. A video survives of him in that period, a teenage heartthrob with a raspy voice, wiping his palms against his knees as he explains his anger to the camera: the show-runner had cheated, he said, by refusing to let the judges break the tie.

Though he catalogued such gripes with an endearing smile, Zelensky was clearly unwilling to share the crown with anyone. He needed to win. Years later, when he recalled these competitions from his childhood, Zelensky admitted that, for him, “Losing is worse than death.”

Read More: TIME’s Interview with Volodymyr Zelensky

Even if the championship in Moscow did not end in an outright victory for Zelensky, it put him within reach of stardom. One of his team members, Olena Kravets, said they could hardly imagine getting that kind of opportunity. To young comedians from a place like Kryvyi Rih, she said, the major league of KVN “was not just the foot of Mount Parnassus”—the home of the muses in Greek mythology—“this was Parnassus itself.”

Its summit stood in the northern part of Moscow, in the studios and greenrooms around the Ostankino television tower, home to the biggest broadcasters in the Russian-speaking world. The major league of KVN had its main production headquarters there, and Zelensky soon made it inside. The year after their breakout performance in Moscow, they competed for the first time under the name Kvartal 95—or District 95, a nod to the neighborhood where they grew up.

Along with the Shefir brothers, who served as the team’s lead writers and producers, Zelensky soon rented an apartment in the north of Moscow and devoted himself to -becoming the champion. For all KVN teams, that required winning the favor of the league’s perennial master of ceremonies, Alexander Maslyakov. A dapper old man with a Cheshire smile, Maslyakov owned the rights to the KVN brand and hosted all the biggest competitions. His nickname among the performers was the Baron, and he and his wife, the Baroness, ran the league like a family business.

“ KVN was their empire,” Pereverzev told me. “It was their show.” At first, the Baron took a liking to Zelensky and his crew, granting them admission to the biggest stage in Moscow and the touches of fame that it brought. But there were hundreds of other teams vying for his attention, and the competition among them was vicious. “Everyone there lived with this constant emotional tension,” Olena Zelenska told me. “You were always told to know your place. The whole time we were performing in Moscow, they always told us: ‘Remember where you came from. Learn to hold a microphone. This is Central Television. You should feel lucky.’ And that’s how all the teams lived, though not so much the lucky ones from Moscow. They were loved.”

In the major league of KVN, Zelensky came face-to-face with a brand of Russian chauvinism that would, in far uglier form, manifest itself about two decades later in the Russian invasion of Ukraine. As Zelenska put it when we talked about the KVN league, “Those who were not from Moscow were always treated like slaves.”

The informal hierarchy, she said, corresponded to Moscow’s vision of itself as an imperial capital. “Teams from Ukraine were of course even farther down the ladder than all the Russian cities. They could, for instance, put up with Ryazan”—a city in western Russia—“but a place like Kryvyi Rih was something else. They’d never even seen it on a map. So we always needed to prove ourselves.”

The unwritten rules within the league reflected the role KVN played in the Russian-speaking world. Amid the ruins of the Soviet Union, it stood out as a rare institution of culture that still bound Moscow to its former vassal states. It gave kids a reason to stay within Russia’s cultural matrix rather than gravitating westward, toward Hollywood. The league had outposts in every corner of the former empire, from Moldova to Tajikistan, and all of them performed in the Russian language.

Even teams from the Baltic states, the first countries to break away from Moscow’s rule in 1990 and 1991, took part in the KVN league; its biggest annual gathering was held in Latvia, on the shores of the Baltic Sea. Viewed in a generous light, these contests could be seen as a vehicle for Russian soft power in much the same way that American movies defined what good guys and bad guys are supposed to look like for viewers around the world. To be less generous, the league could be construed as a Kremlin-backed program of cultural colonialism.

In either case, the center of gravity for KVN was always Moscow, and nostalgia for the Soviet Union was a touchstone for every team that hoped to win. Zelensky’s team was no exception, especially since their best shot at victory in the early 2000s coincided with a change of power in the Kremlin. With the election of Vladimir Putin in 2000, the Russian state embraced the symbols and icons of its imperial past, and it encouraged its people to stop being ashamed of the Soviet Union. One of Putin’s first acts in office was to change the melody of the Russian national anthem back to the Soviet one.

When it came to KVN, Putin was always an ardent supporter. He often attended KVN championships, and he liked to take the stage and offer pep talks to the performers. In return, they made him the occasional subject of jokes, though none were ever very pointed. One of the first, when he was still the Prime Minister in 1999, made fun of his soaring poll numbers after the Russian bombing campaign of Chechnya began that summer: “His popularity has already outpaced that of Mickey Mouse,” said the performer, “and is approaching that of Beavis and Butt-Head.”

Seated in the hall next to his bodyguard, Putin snickered and slumped in his chair. Less than a year later, he made clear that sharper jokes in his direction would not be tolerated. In February 2000, during Putin’s first presidential campaign, a satirical TV show called Kukly, or Puppets, depicted him as a gnome whose evil spell makes people believe he is a beautiful princess. Several of Putin’s campaign surrogates called for the Russian authors of the sketch to be imprisoned. The show soon got canceled, and the network that aired it was taken over by a state-run firm.

Read More: Column: How Putin Cannibalizes Russian Economy to Survive Personally

Zelensky, living and working in Moscow at the time, watched the turn toward authoritarianism in Russia with the same concern as all his peers in show business, and, like everyone else, he adapted. To stay on top, his team understood it would not be wise to make fun of Russia’s new leader. During one sketch in 2001, Zelensky’s character appealed to Putin as the decider “not only of my fate, but that of all Ukraine.” A year later, in a performance that brimmed with nostalgia for the Soviet Union, a member of Zelensky’s team said Putin “turned out to be a decent guy.”

But such direct references to the Russian President were rare in Zelensky’s early comedy. More often he joked about the fraught relationship between Ukraine and Russia , as in his most famous sketch from 2001, performed during the Ukrainian KVN championships. Titled “Man Born to Dance,” it cast Zelensky in the role of a Russian who can’t stop dancing as he tells a Ukrainian about his life. The script is bland and the humor juvenile. Zelensky grabs his crotch like Michael Jackson and borrows the mime-in-a-box routine from Bip the Clown.

At the end of the scene, the Russian and the Ukrainian take turns humping each other from behind. “Ukraine is always screwing Russia,” says Zelensky. “And Russia always screws Ukraine.” The punch line did not come close to the kind of satire Putin’s Russia needed and deserved. But as a piece of physical comedy, the sketch is memorable, even brilliant. Zelensky’s movements, much more than his words, seem to infect the audience with a kind of wide-mouthed glee as he shimmies and high-kicks his way through the lines in a pair of skintight leather pants.

The most magnetic thing about the sketch is him, the grin on his face, the obvious pleasure he gets from every second on the stage. The judges loved it, and that night, before a TV audience of millions, Zelensky’s team became the undisputed champions of the league in their native Ukraine. But, on the biggest stages in Moscow, victory would continue to elude them, and their troupe did not last long in the major leagues of KVN.

After competing and losing in the international championships three years in a row, they gathered up their props and left Moscow in 2003. Members of Zelensky's team agree their departure was far from amicable, though they all seem to remember it a little differently. One of them told me the breaking point with KVN was an antisemitic slur. During a rehearsal, a Russian producer stood on the stage and said loudly, in reference to Zelensky, “Where’s that little yid?”

In Zelensky’s version of the story, the management in Moscow offered him a job as a producer and writer on Russian television. It would require him to disband his troupe and send them back to Ukraine without him. Zelensky refused, and they all went home together. Halfway through their 20s, they were now successful showmen and celebrities across Ukraine. But it was still difficult for Zelensky’s parents to accept comedy as his career.

“Without a doubt,” his father said years later, “we advised him to do something different, and we thought the interest in KVN was temporary, that he would change, that he would choose a profession. After all, he’s a lawyer. He finished our institute.” Indeed, Zelensky had completed his studies and earned a law degree while performing in KVN. But he had no intention of practicing law. He found it boring.

When he got back home to Ukraine, Zelensky and his friends staged a series of weddings in their hometown of Kryvyi Rih, three Saturdays in a row. Olena Kiyashko married Volodymyr Zelensky on Sept. 6, 2003, and Pikalov and Pereverzev married their respective girlfriends. By the end of the year, when Olena was pregnant with their daughter, Zelensky moved to Kyiv to build up his new production company, Studio Kvartal 95.

Even at this early stage in his career, Zelensky’s confidence went beyond the typical swagger of a young man smitten with success. He betrayed no doubts in his team’s ability to make it big, and if he felt any fear he hid it from everyone, including his wife. For an expectant father in his mid-20s, the job offered to him in Moscow must have been more tempting than he let on. Apart from the money, it would have placed him among the glitterati, the producers and showrunners in the biggest market in the Russian-speaking world.

Read More: Inside Zelensky’s Plan to Beat Putin’s Propaganda in Russian-Occupied Ukrain e

Instead he took a risk and struck out in a much smaller pond, relying on the team of friends who looked to him for leadership and made him feel at home wherever he went. Upon arriving in Kyiv, Zelensky scored a meeting with one of the country’s biggest media executives, Alexander Rodnyansky, the head of the network that produced and broadcast the KVN league in Ukraine. The executive knew Zelensky from that circuit as a “bright young Jewish kid,” he told me. But he didn’t expect the kid to stride into his office with a risky business proposition.

Accompanied by the Shefir brothers, who were a decade older and more experienced in the industry, Zelensky did the talking. He wanted to appear with his troupe on the biggest stage in Kyiv for a nationally televised performance, and he needed Rodnyansky to give him the airtime and bankroll part of the production, marketing, and other costs. “The chutzpah on this guy, that’s what I remember,” the executive told me. “He had this bulletproof belief in himself, with these burning eyes.”

Many years later, Rodnyansky would come to see the danger hidden in that quality. It would lead Zelensky to the false belief that in the role of President , he could outmaneuver Putin and negotiate his way out of a full-scale war. “I think that confidence of his betrayed him in the end,” he said. But at the time, Zelensky’s charm won out in the negotiations with Rodnyansky, who agreed to take a risk on the performance.

It proved to be such a success that, shortly after, the team at Kvartal 95 reached a deal to make a series of variety shows that would air in Russia and Ukraine. Their tone departed from the more wholesome, aw-shucks style of KVN. The jokes took on a harder edge, and they became much more overtly political. Pereverzev, who was a writer on the shows, told me their aim was to make a version of Saturday Night Live with elements of Monty Python.

It was an untested concept on Ukrainian TV. There was no way to tell whether the audience was ready. “That was Green’s style,” he said, using Zelensky’s nickname. (The word for “green” in Ukrainian and Russian is the same: zeleny. ) “That was his main quality as a leader. He’d just say, ‘Let’s do it.’ Then we’d all get scared, and he would just tell us to trust him. All our lives it was like that. And at some point we just started to trust him, because when he said it would work out, it did.”

Excerpted from THE SHOWMAN: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr Zelensky by Simon Shuster, to be published January 23 by William Morrow. Copyright © 2024 by Simon Shuster. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers.

Correction, Jan. 5: The original version of this story misstated when Zelensky's first child was born. It was 2004, not 2003.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

How war changed Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy

Dave Davies

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy sings the national anthem during a visit to the city of Izium, in the Kharkiv, Sept. 14, 2022. Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP hide caption

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy sings the national anthem during a visit to the city of Izium, in the Kharkiv, Sept. 14, 2022.

Nearly two years into Russia's war in Ukraine , Time correspondent Simon Shuster says Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy is "almost unrecognizable" from the happy-go-lucky, optimistic comedian Shuster first met in 2019.

"There's just a toughness and a certain darkness about him now that really didn't exist before," Shuster says of the former sitcom star. "He's still extremely committed to this war, to winning this war. ... And he's very single minded, almost obsessive, in pursuing that goal."

Shuster, who has a Russian father and a Ukrainian mother, has been reporting on the region for 17 years and spent months embedded with Zelenskyy's team in Kyiv as the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfolded in February 2022. His new book is The Showman: Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and Made a Leader of Volodymyr Zelensky.

Reporter describes an astounding amount of military hardware going in to help Ukraine

Although the U.S. had warned that a Russian invasion was imminent, Shuster writes that Zelenskyy did not believe that the capital would be attacked. In fact, Shuster says, Ukrainian first lady Olena Zelenska was "totally shocked" by the invasion, and hadn't even packed a suitcase.

From the very beginning, Shuster says Zelenskyy drew on his background as an entertainer to help communicate the Ukrainian plight to a broader audience — even as he worried that the world's attention would eventually fade.

Ukraine invasion — explained

"Often his military tactical decisions were guided by a desire to have these demonstrative victories, something that could really grab the world's attention, whether it's bombing the bridge that connects Russia to Crimea, or various battles ... that maybe were not strategically the most important, but they were dramatic," Shuster says.

Shuster says, looking ahead, that Zelenskyy and his team are open to negotiating for peace with Russia, but they are also developing ways to sustain the war — even if Western support declines.

Volodymyr Zelenskyy went from comedian to icon of democracy. This is how he did it

"President Zelenskyy and his team have a clear vision of where this goes next," Shuster says. "They ... are actively developing ways to sustain the fight, not to be pushed into a capitulation or a negotiation that they don't want to participate in, and to continue fighting on their own resources, their own weapons."

Interview highlights

On Zelenskyy's reaction to the destruction and atrocities in Bucha

Zelenskyy takes center stage in Davos as he tries to rally support for Ukraine

On a personal level, it was absolutely devastating to him. I think, to an extent, that surprised me; he really takes the suffering of civilians close to the heart. He doesn't see them as some kind of abstract mass, sacrificing for the nation. He really feels the pain of individual victims of this war. So that day when he went to Bucha and he saw the atrocities committed there, hundreds of civilians massacred, some tortured, it was just the worst kinds of scenes you could imagine at war time, he was deeply affected by that emotionally.

In Bucha, death, devastation and a graveyard of mines

Ravaged by Russian troops, Bucha rises from the ashes

He later described it as the worst day of that tragic year. He said it taught him that the devil is not far away, not some figment of our imagination but he's right here on this earth. He said he saw the work of the devil there in Bucha. The next phase, when he sort of took in that pain, he moved on to the next stage of the war. He still had a war to fight. And he invited the media to visit Bucha ... and he began inviting his international partners and allies, Europeans, Americans from all over the world. Every time they made a visit to President Zelenskyy in Kyiv, he encouraged them to visit Bucha, to see it for themselves. ... They saw the atrocities for themselves, and it would encourage them to maintain a much higher level of support when they went back home to their capitals after having seen up close the mass graves and the real evidence of Russian war crimes.

On surprising concessions Zelenskyy was willing to make in negotiations with Russia

They continued the negotiations even after the atrocities were revealed in Bucha — even after many of Zelenskyy's own advisers told him, 'We can't go on with these negotiations. We can't talk to these monsters after what they've done to us.' Zelenskyy would continue insisting that no, even though this is a genocidal war, we need to continue trying to find peace at the negotiating table. So they did offer a series of concessions, very serious ones. One of them, the main one was this idea of permanent neutrality. So Ukraine would agree to give up its ambition of joining the NATO alliance. This was one of the main excuses that Vladimir Putin used to justify this horrific invasion, that he wanted to stop NATO from admitting Ukraine. Not that NATO had any plans to admit Ukraine anytime soon, but this was kind of one of the paranoid risks that Putin pointed to. So Zelenskyy said, alright, if that's what you're afraid of, we will make a formal commitment to remain neutral. He even agreed that any military exercises that involve foreign troops on the territory of Ukraine would not happen without Russian approval, if Russia saw those exercises as a risk. So he was willing to really go far in granting concessions early in the invasion. And those negotiations gradually broke apart. One of the reasons was Bucha and the atrocities uncovered. But I think also what we saw was that in April, there were a series of victories that Ukraine achieved on the battlefield that convinced Zelenskyy that, hey, maybe we should see how far we can push this militarily while we have the momentum. Maybe we don't need to negotiate right now. Maybe we fight first, push the Russians back, and then potentially negotiate from a position of strength.

On the July 2019 phone call between Zelenzkyy and President Trump, which later became the basis of Trump's first impeachment

If you read closely the White House transcript that was later released of that phone call, at the end Trump promises to arrange a visit for Zelenskyy to the White House. And it's hard to overstate the importance of that kind of visit for any Ukrainian leader. The United States is by far the most important ally, not only because of relying on U.S. weapons, but also for political support, diplomatic support, financial aid loans. Any incoming Ukrainian president, any Ukrainian president, period, needs to constantly demonstrate the strength of his or her relationship with the United States.

READ: House Intel Committee Releases Whistleblower Complaint On Trump-Ukraine Call

So for Zelenskyy coming in, that was priority number one in the international arena to visit the White House, to sit there with the U.S. president, whoever it may be, and to demonstrate to the people back in Ukraine that, look, under my leadership, this relationship will continue to grow stronger, certainly won't grow weaker. So that was what was going through Zelenskyy's mind for the most part at the time. And when, at the end of that phone call, Trump said, "OK, sure. Come on down to Washington and we'll arrange this visit," they saw that as quite an accomplishment. So when they put down the phone as one of the participants, on the Ukrainian side told me, there was some jubilation in the room on the Ukrainian side, and they actually went to a neighboring room and they had some ice cream to celebrate.

On what lesson Zelenskyy drew from Trump's first impeachment

I talked to a number of the people whose messages wound up projected onto the big screens in the hearing rooms during the impeachment inquiry in Congress. Imagine what that feels like. You're a state official in Ukraine. You're having confidential, classified conversations with your counterparts in the United States. You're assuming that those conversations, text messages, emails are going to remain private. And then you turn on CNN and you see your messages projected onto the screen for the world to see. That was very humiliating. It was very demeaning. In many cases, the U.S. authorities did not consult with the Ukrainians before publishing those communications. So that was quite annoying. One close adviser to Zelenskyy called it a cold shower. That was one of the milder phrases used to describe that experience.

In the middle of the impeachment hearings, I sat down with President Zelenskyy in his office, for one of our interviews that is described in the book, and it was maybe one of the lowest points that I'd seen him. He was at the time preparing also simultaneously for his first sit down negotiations with Vladimir Putin. The goals of those negotiations were to end the separatist conflict in the East and prevent the kind of invasion that we later saw play out across Ukraine. So he had a lot to juggle while he was focused on trying to negotiate with Putin and settle their relations and bring peace, all the American media, and all the international media wanted to talk about was Rudy Giuliani, Hunter Biden and all this stuff. So it was a massive distraction. One quote that stands out from that interview was he said, "I don't trust anyone at all." And essentially the lesson to him was: Alliances are flimsy. Everyone just has their national interests, their personal interests. And he felt a deep disillusionment in his belief that he could rely on certain allies, Europeans, Americans. He said everybody just has their interests, and I don't trust anyone at all.

Sam Briger and Seth Kelley produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.

Correction Jan. 24, 2024

A previous version of this story misspelled the capital of Ukraine as Kiev. It it Kyiv.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Who Is Volodymyr Zelensky, the Ukraine President in the Trump Impeachment Crisis?

Volodymyr zelensky: the ukrainian president linked to trump impeachment inquiry, president trump is facing calls for impeachment related to a phone call with ukraine’s president. who’s the man on the other end of the phone.

President Trump is facing calls for impeachment related to a phone call with Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. A reconstructed transcript of the call appears to show the president asking Zelensky to investigate a political rival, Joe Biden, and his son Hunter. Zelensky denied this. “I think, and you read it, that nobody pushed, pushed me, yes.” “In other words, no pressure.” Here’s a closer look at Ukraine’s leader. He’s a first-time politician who won a landslide victory in May with more than 73 percent of the vote. He beat Petro Poroshenko, who he argued did little to combat rampant corruption. Before entering politics, Zelensky was a comedian and the star of a popular TV series. In a case of life imitating art, Zelensky played a teacher who unexpectedly became president after a speech on anti-corruption went viral. His major priority is ending the war with Russia. Zelensky uses social media to push his image as an everyman, posting selfies, showing off his vacation in the Black Sea, enjoying Ukraine’s sunflower fields and working out. Zelensky is now in a tough spot. He’s caught between wanting to build good relations with the U.S. and getting stuck in the middle of an American political scandal. “I’m sorry, but I don’t want to be involved to, democratic, open — elections. Elections of U.S.A.”

By Andrew E. Kramer

- Published Sept. 25, 2019 Updated Sept. 22, 2021

KIEV, Ukraine — As a television actor in Ukraine , Volodymyr Zelensky played an idealistic schoolteacher whose tirade against corruption is filmed by his students, winds up online and suddenly goes viral, propelling him to the presidency.

The show was a comedy. But the message of fighting back-room wheeling and dealing proved so popular that Mr. Zelensky started a political party named after the program, “Servant of the People,” and ended up becoming Ukraine’s president for real — with a life-mimics-art campaign that built his image as an anti-corruption crusader.

Now, Mr. Zelensky , a 41-year-old political novice who took office in May, is at the center of an impeachment debate in the United States over whether President Trump tried to pressure him into betraying the principles that catapulted him into office.

Mr. Trump and his personal lawyer, Rudolph W. Giuliani, have said publicly that former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. should be investigated in connection with his son’s role in a Ukrainian energy company.

Mr. Trump acknowledged raising the corruption allegations in a phone call with Mr. Zelensky on July 25, intensifying claims by Democrats in Congress that Mr. Trump inappropriately pressed a foreign government to undermine one of his main challengers in the 2020 American presidential race.

The uproar grew after senior administration officials said that Mr. Trump personally ordered the suspension of $391 million in aid to Ukraine in the days before the call. One of the big questions is whether Mr. Trump used vital funds for Ukraine — a country battling pro-Russian separatists — as a cudgel to dig up dirt on his political rival in the United States.

Mr. Trump has described his call with Ukraine’s president as “totally appropriate” and said there was “no quid pro quo” linking American aid to a Ukrainian investigation into Mr. Biden.

But while the issue has put Mr. Zelensky in an uncomfortable bind, he has not announced any new investigations into Mr. Biden or his son.

In fact, during his call with Mr. Trump in July, Mr. Zelensky told Mr. Trump that the new Ukrainian government had a policy of not intervening in the nation’s criminal justice system, according to a presidential aide, Andriy Yermak.

Mr. Yermak, who discussed the call during an interview in August — before it became a focus of congressional investigations in the United States — said he had already conveyed the same message to Mr. Giuliani, who had been openly pressing Ukrainian officials to investigate Mr. Biden.

“I know that Mr. Zelensky, in a conversation with Mr. Trump, said the same: that the principle of the new government in Ukraine is openness and respect for law and lack of interference of the government in the judicial system,” Mr. Yermak said of the phone call between the two presidents.

The controversy has thrust Mr. Zelensky — who is scheduled to meet with Mr. Trump on Wednesday on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly — directly onto center stage in a standoff between Mr. Trump and Democratic members of Congress who want to impeach him.

In past interactions between Ukrainian and American officials, the Americans have typically been the ones lecturing their Ukrainian counterparts about rooting out political influence over the courts, a problem in most post-Soviet countries. The practice even has a name — “telephone justice” — referring to the surreptitious phone calls placed by politicians to prosecutors and judges.

But in this case, the roles were reversed — and the new administration in Ukraine did not bend to the American pressure, said a senior Western diplomat in Kiev familiar with the exchanges between Mr. Trump, Mr. Giuliani and the Ukrainian government.

Still, the encounters with Mr. Trump and Mr. Giuliani have left Mr. Zelensky and his aides a bit shocked, the diplomat said.

Mr. Giuliani’s pressure for an investigation of Mr. Biden began before Mr. Zelensky’s inauguration in May, placing the new government in a tough position, said Serhiy M. Marchenko, a deputy chief of staff under Ukraine’s former president.

“If we help the Trump administration in some process that damages Biden, in the long run we harm relations with the Democrats,” Mr. Marchenko said. “If we help the Democrats, we anger Trump.”

Mr. Giuliani has pressed the Ukrainians to investigate Mr. Biden’s younger son, Hunter, who sat on the board of a Ukrainian energy company, Burisma, as well as the actions of the former vice president.

Mr. Trump’s allies contend that Mr. Biden was trying to protect the company from prosecution when he called for Ukraine’s top prosecutor — who had investigated the company — to be fired in 2016.

People familiar with Mr. Trump’s phone call with Mr. Zelensky in July said the American president repeatedly urged him to speak with Mr. Giuliani as well.

Mr. Zelensky initially rebuffed Mr. Giuliani’s appeals for a meeting to press for an investigation of Mr. Biden.

After that, the senior Ukrainian aide, Mr. Yermak, said he called Mr. Giuliani to convey the government’s response, which was essentially the same as the campaign promise not to interfere in the criminal justice system.

Then, after the phone call on July 25 between Mr. Zelensky and Mr. Trump, Mr. Yermak said he met with Mr. Giuliani in Madrid. In the interview in August, Mr. Yermak said he told Mr. Giuliani that the new government in Kiev would “guarantee everybody inside the country and foreign citizens and companies open and honest justice.”

Mr. Yermak said he explained that, under the new administration, the justice system would be fair and open to investigating any possible crimes, but that the government would not intervene.

Mr. Giuliani, however, said he came away from his interactions with Mr. Yermak over the summer “pretty confident they’re going to investigate” Mr. Biden.

Now that the exchanges have become such a focal point in the congressional debate over Mr. Trump’s conduct, Mr. Zelensky and members of his administration have largely sealed their lips. Mr. Yermak and other officials have declined additional interviews, apparently wary of being caught up in the caustic American political battle.

Corruption is likely to come up again at the meeting with Mr. Trump on Wednesday. As if to underscore the theme — a bread-and-butter issue for people in his country — Mr. Zelensky posted a video online before leaving for the United Nations that asked Ukrainians to call a hotline if an official solicited a bribe.

“Ukraine is a very young democracy, like a child,” said Daria M. Kaleniuk, director of the Anticorruption Action Center. “The United States is an adult. But sometimes children behave as adults, and adults as children.”

Maria Varenikova contributed reporting.

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Leaders & Notable People

Buy new: $14.53

Other sellers on amazon.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Zelensky: A Biography of Ukraine's War Leader Hardcover – August 4, 2022

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 256 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Canbury Press

- Publication date August 4, 2022

- Dimensions 5.5 x 1 x 8.5 inches

- ISBN-10 1912454777

- ISBN-13 978-1912454778

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Canbury Press (August 4, 2022)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 256 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1912454777

- ISBN-13 : 978-1912454778

- Item Weight : 10.6 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.5 x 1 x 8.5 inches

- #6,983 in WWII Biographies

- #8,111 in Presidents & Heads of State Biographies

- #426,971 in History (Books)

About the author

Steven derix.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Volodymyr Oleksandrovych Zelenskyy (born 25 January 1978) is a Ukrainian politician and former actor who has been serving as the sixth president of Ukraine since 2019.. Born to a Ukrainian Jewish family, Zelenskyy grew up as a native Russian speaker in Kryvyi Rih, a major city of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast in central Ukraine. Prior to his acting career, he obtained a degree in law from the Kyiv ...

Volodymyr Zelensky (born January 25, 1978, Kryvyy Rih, Ukraine, U.S.S.R. [now in Ukraine]) Ukrainian actor and comedian who was elected president of Ukraine in 2019. Although he was a political novice, Zelensky's anti-corruption platform won him widespread support, and his significant online following translated into a solid electoral base.

Volodymyr Zelenskyy was elected President of Ukraine on April 21, 2019. On 20 May, 2019 sworn in as the 6 th President of Ukraine. January 25, 1978 - Born in Kryvyi Rih, Ukraine. 2000 - Graduated from Kyiv National Economic University, with a law degree. 1997-2003 - Actor, performer, script writer, producer of the stand-up comedy contest team ...

Before he became Ukraine's president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy was a comedian and is seen here performing during the 95th Quarter comedy show, in Brovary, Ukraine. "Zelenskyy has a controversial ...

Zelensky himself has credited Benny Hill, the crude British comedian, as an influence. ... Some even worried that he might be too accommodating to Vladimir Putin, Anton Troianovski, The Times's ...

Volodymyr Zelensky approached a lectern under bright lights, preparing to deliver a message to the Ukrainian people. "Today I will start with long-awaited words, which I wish to announce with ...

Mr Zelensky has turned his presidency into a quest: he has broken into a closed political system and stuck up for ordinary people. They have cheered him on. His attack on the oligarchs is popular ...

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky photographed in Kyiv on April 19 Alexander Chekmenev for TIME. By Simon Shuster/Kyiv. April 28, 2022 6:00 AM EDT. T he nights are the hardest, when he lies ...

December 31, 2018 - Announces his candidacy in the 2019 presidential election. April 21, 2019 - Zelensky is elected president, defeating incumbent Petro Poroshenko with 73.22% of the vote. May 20 ...

Text. President Volodymyr Zelensky has become the face of Ukraine's resistance against Russian President Vladimir Putin 's invading forces, with impassioned speeches such as an address to the ...

In the West headlines ask whether Vladimir Putin, Russia's president, has started to win. ... Mr Zelensky gives little away about what Ukraine can achieve in 2024, saying that leaks before last ...

How Volodymyr Zelensky rallied Ukrainians, and the world, against Putin. Mr. Zelensky's decision to remain in the capital, Kyiv, while it's under Russian attack has moved many. President ...

By John Daniszewski. Published 11:39 AM PDT, February 26, 2022. WARSAW, Poland (AP) — When Volodymyr Zelenskyy was growing up in southeastern Ukraine, his Jewish family spoke Russian and his father once forbade the younger Zelenskyy from going abroad to study in Israel. Instead, Zelenskyy studied law at home.

First, President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine addressed the 44 million citizens of Ukraine. Then he turned to the 144 million Russians living next door and beseeched them to prevent an attack ...

While Russian President Vladimir Putin has appeared increasingly erratic - accusing Ukraine of "genocide" in the breakaway Donetsk and Luhansk republics, and talking of the need to "de-Nazify" the ...

Zelensky's mother Rymma, an engineer by training, was closer to their only son and gentler toward him, doting on the boy much more often than she punished him. ... With the election of Vladimir ...

Nearly two years into Russia's war in Ukraine, Time correspondent Simon Shuster says Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy is "almost unrecognizable" from the happy-go-lucky, optimistic comedian ...

Volodymyr Oleksandrovych Zelenskyy (Ukrainian: Володимир Олександрович Зеленський; born 25 January 1978) is a Ukrainian politician, screenwriter, actor, comedian and director.He is the President of Ukraine since 2019.. Zelenskyy played the role of President of Ukraine in the hugely popular 2015 television series Servant of the People.

In a case of life imitating art, Zelensky played a teacher who unexpectedly became president after a speech on anti-corruption went viral. His major priority is ending the war with Russia.

He earned a degree in law, and he founded a TV production entertainment company. He acted in the popular TV series Servant of the People, where his character fought corruption and became the president of Ukraine. Zelensky sometimes courted controversy with his comedy. Russia threatened to ban his work after it was revealed that his production ...

Zelensky is the first major biography of Ukraine's leader written for a Western audience. Told with flair and authority, it is the gripping story of one of the most admired and inspirational leaders in the world. Millions who have admired Volodymyr Zelensky's defiance during Russia's invasion of Ukraine will learn much from this up-to-date biography of the Ukrainian President.

Also during his address at the forum, Zelensky pointed to Russia's renewed usage of aerial bombs as one of Russian President Vladimir Putin's major "bets" to turn the tide of the war.